Daniel Arnold’s New Pleasure? Missing the Shot.

In the past three years, the photographer Daniel Arnold has lost a father, a grandfather, an uncle, a younger brother, and a cat. Arnold—who first garnered fame in the 2010s for New York street photographs that converge on moments of offbeat serendipity—entered Aperture’s offices in Chelsea wearing a threadbare hoodie, a film camera slung over one shoulder. It’s unsurprising, given his commitment to doing this interview only a few days after his uncle’s funeral, that our conversation touched on the metaphysical: questions on art, God, the Vatican.

Arnold isn’t shy to admit failure or shame. He wears as a badge of honor his lack of technical prowess when he first started photography. This was more than ten years ago, when he abruptly dropped his career as a writer to begin a quixotic quest of self-realization. In this way, the camera that has brought him recognition on the street can be seen as a talisman: the bijou in which he gathers evidence of the primordial, those fleeting instances in public life that speak to not only love or heartbreak, but also his own dogged searching.

On the eve of the publication of You Are What You Do (Loose Joints, 2025), I talked with Arnold about Sichuan peppercorns, authenticity, and his second monograph.

Freddy Martinez: You start your editorial photoshoots with playful icebreakers. I’d like to do the same. I read that you called Lee Friedlander a Sichuan peppercorn.

Daniel Arnold: Did I? That sounds like me. I back that. I don’t remember it, but I believe it, and I think it’s right.

Martinez: How does Friedlander’s work remind you of a Sichuan peppercorn?

Arnold: I do a lot of archive review, a lot of editing. It’s my nighttime activity. I’m such a junkie for pictures. And there are times when your mind gets deadened to what’s in front of you, especially when it’s your own output. There are times when I’ve been stumped and really over it, and I’ll flip through that big yellow MoMA retrospective of Friedlander’s, or it’s any Friedlander sequence, and I’ll experience that flavor-tripping phenomenon: When I go back to my work, it looks completely different to me. I can apply his brilliant formality to my own sloppy world and make new sense of it.

Martinez: Does that comparison ever feel troubling to you?

Arnold: You mean, does it make me feel insecure?

Martinez: Yes.

Arnold: If you’re going to struggle with insecurity, you’re probably in the wrong business. Insecurity is formative. It’s helpful, early on, but if I saw myself in competition with the rest of the photographers, I’d be cooked. I wouldn’t be able to go outside. There’s a tendency, especially in academia, to put everything in a lineage and see how moments in history speak to each other, how different voices compare. That’s for somebody else to do. For me, I deal with the world. I deal with my own little habit and keep it at that.

Martinez: You announced yourself in the early 2010s on Instagram. Looking back more than ten years ago, now at age forty-five, how would you describe your place in life right now?

Arnold: There was more ambitious ego at play in that first public push between 2012 and 2014. But I was very lucky to put a lot of that first desirous, ambitious energy into the writing chapter of my career. By the time photography presented itself to me, I had already moved past that New York thing of seeking glamour. I started photography in touch with the necessity to make a mess and fail. I didn’t even know how to use a camera properly then. I just knew I loved pictures. So I pointed the simplest camera that I could and crossed my fingers and made a lot of mistakes. But anyway, forty-five. Looking back, it has been an insanely consequential ten years. I think I’m now much more rooted in—not to be a downer—but in grief and alienation. There’s still heavy curiosity and clinging respect for naivety. I try to find that and cultivate it wherever I can. But now and then are different worlds. I definitely don’t work with the same energy that I used to, which is not to say that I’m tired. It’s just that my priorities have changed. My appetites have changed.

Martinez: You mentioned grief and naivety. It brings to mind vulnerability as an artist. What do you think about the idea of nakedness? This idea that a person may have no pretense. How do you think people reach that? How do you think people can—

Arnold: Aspire to nudity?

Martinez: [laughs] Yes.

Arnold: I think I operate from shame, and shame is obviously the number one enemy of nudity. But I aspire to it. What you call nakedness I find it in those glimpses, in flashes of insight. I find it through relentless practice.

Martinez: Is shame tied to the grief that you mentioned?

Arnold: Oh, for sure. Good eye. My father died last summer. And my clearest memory of his funeral is flopping on a joke I attempted to make in his eulogy. The joke was, “I’m really smart.” I have a weird, dry sense of humor that takes for granted that people are actually paying attention and thinking about everything I say, and everybody there just took it straight, like I was using my dad’s funeral as an opportunity to promote myself. Laugh, it’s fine. That’s the right response. But the possibility that somebody could think that I was celebrating myself so horrifies me—that this is the lone souvenir I take away from losing the great male lead of my life. All I can really remember is when I looked smug and embarrassed myself.

Martinez: I think it’s insightful to know that a photographer is not just their camera, not just their eye: There’s also heart. You said that the guiding light of finding photographs that “double as a proof of magic” no longer compels you. What is guiding you right now?

Arnold: That statement comes across more definitive than I meant it. Do you know Wings of Desire? That film’s depiction of magic—the angel with a notepad noticing when the wind blows up someone’s jacket or when someone is crying alone in a parking lot—that breeze that blows through your life is still a guiding light. I mean, if not guiding, at least one of the great pleasures.

What I was referring to when I said that was this feedback-driven appetite for knockout, punch-line pictures—ones with bold and direct communication. Those work great on Instagram, or at least, they did for me early on. I spent a lot of time, whether I meant to or not, oiling my gears for making those pictures. It just got to a point where even landing thirty-six of them felt kind of boring and contrived. It was like I was imitating myself.

Martinez: Driven by an algorithm in a feedback loop—did you feel like you were being used by a machine in a way?

Arnold: Not exactly. But I was definitely being corrupted by social media. I can’t say my departure was as calculated as it now feels. I mean, it was COVID and the George Floyd protests were raging, and I couldn’t stand to use any aspect of that moment to draw attention to myself or to advertise my cute little insights. It felt disgusting. I stepped away from Instagram and almost immediately had no idea how to get back. I had a week, maybe a day, of disoriented panic about that, but it was really liberating. Leaving definitely stirs up more insecurity than staying, because when you’re checking in with an audience you have this confidence about whether you’re getting it right or wrong. Now, it’s hard to tell if it’s good anymore, but I don’t think it matters. I’m not swinging for the fences. I’m trying to do that Wings of Desire ritual every day and just be open to noticing the breeze on my cheek.

Martinez: The writer Denis Johnson would describe it as seeing mystery wink at us. Photographers are pointing at something and saying, “Look this way. I want you to see this.”

Arnold: I think that’s the structure of the game. Any game you play by yourself, exhaustively, every day of your life, you get to have an impish relationship with it. Now, I take great pleasure in missing a great picture. Like if I had taken one big step to the right and lifted the camera a little higher, you would see that there was this great thing happening, but I shoot from the wrong spot, so it’s loaded with dramatic irony that only I feel. It’s like a puzzle box. There’s some pleasure in that, dumb pleasure probably. But how do I keep the game entertaining for myself? I mean, there’s still that very basic caveman thing, “Oh, look at that. That’s funny. That makes me sad.”

For better or for worse, I’ve tried to make myself a world where I can work without the disruptive noise of my brain, one in which I can be a servant of my instincts, and then I can bring intention and analysis back to work at night in the edit. I’ve talked for a long time about a Jekyll and Hyde relationship with the editor within me, and I stand by it. The guy who’s deciding what the pictures are is different than the guy who’s taking them.

Martinez: Would you say the editor is the driving force of your work ethic?

Arnold: I don’t think you can really separate the two. The edit work that I do at night is bringing reason to a mostly unconscious part of my brain. But I also learn about the daytime guy’s shortcomings, and I’m able to carry those lessons into the next day, like little Post-It reminders for my automatic brain, “Hey, maybe you need to get a little bit closer today, or maybe you should pay a little bit more attention to framing. Maybe don’t be so loose about shooting from your belly and having everything be way too far to the left.” It’s kind of self-contradictory now that I’m hearing myself say it out loud, but on one hand, the rigor enables this mindless kind of work, and on the other hand, it also infuses that mindlessness with a gut discipline.

Martinez: You’ve spoken about storytelling. Looking through your work, I imagined what folklore could look like in New York City.

Arnold: Music to my ears.

Martinez: There’s an idea that folklore is a slow, traditional type of narrative that forms over centuries. I think it’s also tied to moments when somebody shows us that the past is still present now. I was wondering what you think about folklore as it relates to your photography?

Arnold: The title You Are What You Do comes from one of the pictures. It’s written in yellow chalk on a red wall where some girls are playing hide-and-seek. It’s also a phrase from Carl Jung. I bought myself a particular edition of Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces because, although Loose Joints has their hands on the reins of production, I wanted to make a bootleg T-shirt with the Thousand Faces cover, so that I could give it away on the side when they’re not looking. What do you do when you empower your unconsciousness to create a document of your emotional experience? It’s archetype, it’s all archetype, and when it comes to storytelling, I think that becomes observable and distinct in any street picture, no matter who’s making it. You see a cop, a kiss. There are all these things that are shortcuts, or signifiers, that if you just point your camera in that direction—even if you have no idea what else is going on—you dramatically increase the odds that a story is there.

I haven’t had this conversation before. Nobody has put it to me that way, but I aspire to folklore and that outsider, practical documentation. Sometimes I feel like a sculptor, like time is a procession of constantly changing surfaces that I peel off and stick on a cave wall to make my own extra peculiar, inverted world. There’s primordial energy. That’s why I try to work without ego or ambition. Aspiring to success just leads to homogeneity and imitation, and there’s something interesting there, for sure, but I don’t know. Maybe the most moving, thought-provoking art experience I ever had was going to the Vatican.

I don’t have any religious affiliation there, but it’s a masterpiece. The whole thing. Not just the Sistine Chapel, because the Sistine Chapel, you know who did it. For the rest of the place, so many nameless people who put their heart into work that they didn’t start and didn’t finish. It took generations of devotion. And the driving force of it all was—fingers crossed—the existence of “God,” you know, this screaming into the void: “Just in case you’re there, this is how much I love you.” Of that sentiment, I can’t imagine anything more worthy of my energy.

Martinez: That’s beautiful. I’m thinking of family now. Because like those artists who generation after generation say, “In case you can hear me, I love you,” our ancestors might say the same to their descendants—each generation, moving forward, doing its own small part, so that the next one can feel some connection to the past or love. Your father passed away, and you were close.

Arnold: Yes, and I just got home from a very close uncle’s funeral this past weekend, and my little brother before that and my grandpa and my beautiful cat. It’s been all in the past three years. I mean, whatever, this is not an era for, I don’t know, comparing tragedy. There’s so much. I just mean to say that I have some intimacy with death these days.

Martinez: Is that in any way a motivating factor for the book, or was it incidental?

Arnold: It’s there. You Are What You Do is an interesting marker of the moment. Because in my own rambling, messy way, I tried to articulate where I was with Loose Joints. I made them an edit of probably three thousand photos to show the scope of what’s there from my current point of view: Here’s my trajectory from those very crude photographs when I couldn’t use a camera to now trying to work without my brain noticing.

I told them that I had no interest in greatest hits, or “The wide world of Daniel Arnold.” I gave them a loose indication that I’m doing things differently lately, that different things are important to me. I mean, ideally, what I wanted to do was a Rosalind Fox Solomon–type book, where twenty years of puzzle pieces are decontextualized and rearranged to say something new, and I still like that idea, but that’s for me to do alone. And I think that Sarah Chaplin Espenon, who did the editing for the most part, saw that there was this more romantic, more wounded thing happening in my work that offered an alternative to what people usually think of me, and she stubbornly stuck to that as her thesis. She wanted another side.

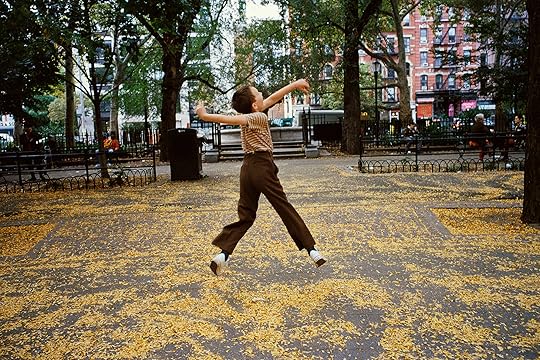

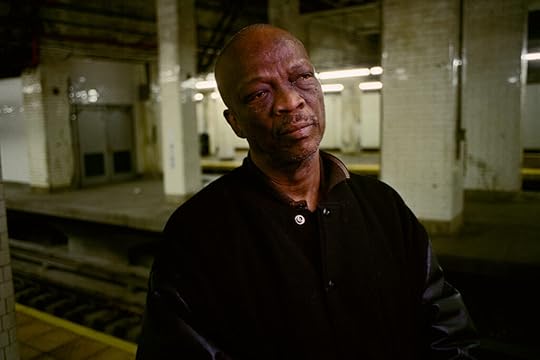

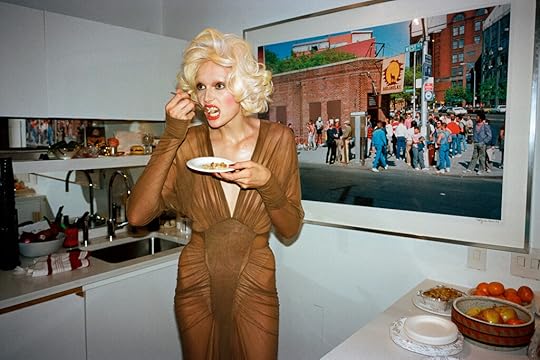

All photographs Daniel Arnold, Untitled, from You Are What You Do (Loose Joints, 2025)

All photographs Daniel Arnold, Untitled, from You Are What You Do (Loose Joints, 2025)© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

Martinez: Do you have any feelings or intuitions for what lies ahead?

Arnold: I don’t, but I preordered Jeff Mermelstein’s What If Jeff Were a Butterfly? I have a new appreciation for that title after talking through this with you for a couple hours. I don’t really know Jeff at all, but I so admire his curiosity. What a free and special brain to have the insight, so many years deep in obsessive work, to say, What if I don’t even know what I am yet? I would hate to predict tomorrow because anything I guess will hem me in. I don’t want a goal. I think that life is scary and stressful, and we’re in hard times. I would love to stay loose and stay open and, more than anything, keep surprising myself. But what will come next? I have no idea.

Martinez: That’s okay.

Arnold: Yeah, it’s better that way.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers