Voynich Reconsidered: the author’s name?

On the voynich.ninja forum, I read a proposal that somewhere on the first page of the Voynich manuscript, we might detect the name of the author.

There is no doubt that on page f1r (that is, folio 1 recto), there are three short strings of glyphs which, unlike most of the text, are approximately right-justified. They are as follows:

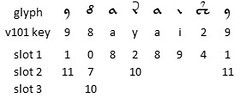

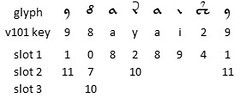

Three right-justified strings of glyphs on page f1r of the Voynich manuscript; and their representations in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. Author's analysis. Image credits: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

We should observe that f1r is not necessarily the original first page. There is evidence that the manuscript has been re-bound, and that the pages are not in their original order. In the upper right corner of page f1r, we see the Arabic numeral 1 (which gives the page its modern numbering); but we are not obliged to assume that it was there when the manuscript was written.

However, if f1r is indeed the original first page, it seems to me a reasonable hypothesis that the three right-justified strings of glyphs have some special significance. We might conjecture that they represent names: for example, of patrons, producers, authors, or scribes. We have no way of knowing how many people were involved in the conception of the manuscript. But Dr Lisa Fagin Davis has identified five scribes: of whom Scribes 1, 2 and 3 contributed 188 of the 227 pages.

{98ayai29}

With that preamble: I propose here to examine the first string of glyphs, on line 6, represented in the v101 transliteration by {98ayai29}. Referring to the manuscript as it appears on the website of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, I could also read this string as {98ayai39} or {98ayai59}, although the glyphs {3} and {5} are much less common than {2}. I could also accept the possibility that the glyph {2} is a {1} with an accent of unknown significance, and if so, I could read the string as {98ayai1’9}.

This glyph string has some unusual properties.

Firstly, the string is unique. It occurs nowhere else in the manuscript: neither as a “word”, nor as a string within a “word”. It is, in linguists’ terminology, a hapax legomenon. That might permit us to suspect that it represents a proper name.

Secondly, the string does not confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words”, which Mary D’Imperio called the “five states”, and which Massimilano Zattera, in his presentation to the Voynich 2022 conference, called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera demonstrated that over 98 percent of the “words” in the Voynich manuscript conform to rules of this nature, or can be disaggregated into chunks which so conform. But this string does not. Below are the glyphs which make up the string, and the permitted slots which, according to Zattera, they may occupy.

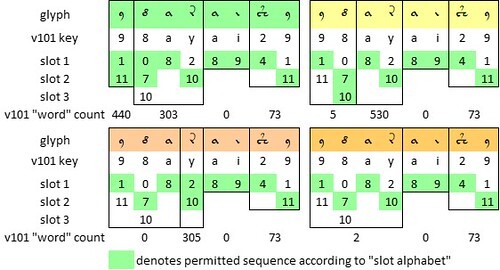

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 6: glyphs and permitted Zattera "slots”. Author’s analysis.

We can see that, even allowing for the flexibility of the glyphs {8}, {9} and {y}, we cannot allocate glyphs to slots in such a way that each glyph is followed by a glyph in the same or a higher slot.

We therefore have to conjecture that the string is not a “word”, but may consist of several “words”, with the word breaks omitted or suppressed. This conjecture is easy to test. We can parse the string {98ayai29} in various ways. For each parsing, we can see whether it produces “words” that exist elsewhere in the Voynich manuscript, and that conform to the slot sequence.

Below is a summary of the tests that I have conducted so far.

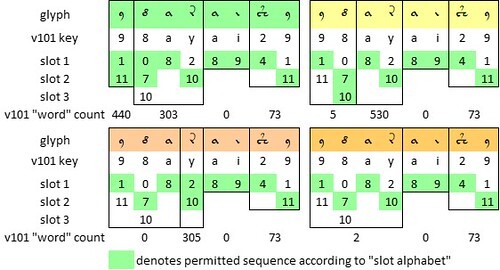

Four ways of parsing the v101 glyph string {98ayai29}; the permitted slots in Zattera's "slot alphabet"; and the “word” counts of each parsed segment in the v101 transliteration. Author’s analysis.

From these results, it seems to me that, if the Voynich scribes intended the string {98ayai29} to conform to the slot sequence, we might infer the following:

Thus, to my mind, if the string is part of the Voynich vocabulary, the most plausible parsing is {9 8ay ai 29}. However, that would still leave {ai} as a non-existent “word”; and we cannot break it further, since {i} never occurs as a single-glyph “word”.

A proper name?

Alternatively, we might conjecture that the string {98ayai29} is not part of the Voynich vocabulary: that is to say, it is not a normal word in the (presumed) precursor language or languages of the manuscript. For the Voynich scribes, it might have been a proper name, or even a foreign word.

In previous articles on this platform, I have advanced the hypothesis that the producer of the Voynich manuscript provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages; a set of mappings from letters to glyphs; and also a set of rules, applied after mapping, for re-ordering the glyphs within “words”. To my mind, these are plausible mechanisms to explain the sequencing of glyphs within “words”, which to my knowledge, does not occur in any natural language.

We might now imagine the scribes faced with an unusual word (that is, either a proper name, or a word from a language other than the primary precursor languages). In such a case, perhaps they would not, or could not, apply their normal rules. For example, they might apply the mapping from letters to glyphs, but omit the re-ordering of glyphs.

In any case, we have nothing to lose by attempting a mapping from the string {98ayai29} to some potential source languages.

In any such mapping, I prefer to avoid or at least to minimise the element of subjectivity, and to examine a range of possible languages, as well as a range of possible transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. For each language and for each transliteration, frequency analysis can be a guide as to how we map a glyph to a letter.

I started with medieval Italian, if only because in previous work, this language had shown promise as a possible precursor of the Voynich text. For example, as I reported in a previous article, several of my variant transliterations yielded mappings of the glyph string {8am} to the Italian words CON (“with”) or alternatively DIO (“God”). Against Italian, it might be argued that if the main text were in Italian, then the right-justified strings on page f1r could be in another language. Anyway, I thought it worth a try.

Below are selected mappings that came closest to yielding pronounceable words:

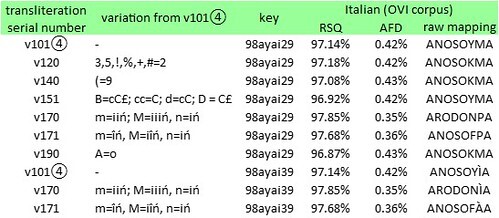

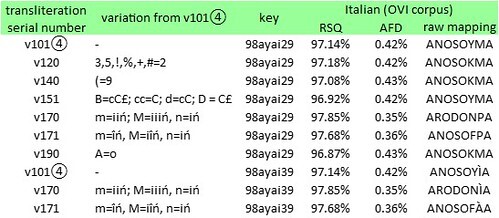

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {98ayai29} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

I have to admit that none of these text strings is, to my knowledge, a word or a proper name in medieval Italian. But it seems to me that there are possibilities to be explored, along the following lines:

I invite any readers who may be interested to explore this approach. If any reader should favor a specific language as the precursor of the glyph string {98ayai29}, and if I have a sufficiently large corpus of text in that language, I will be happy to supply a proposed mapping from glyphs to letters.

There is no doubt that on page f1r (that is, folio 1 recto), there are three short strings of glyphs which, unlike most of the text, are approximately right-justified. They are as follows:

Three right-justified strings of glyphs on page f1r of the Voynich manuscript; and their representations in Glen Claston’s v101 transliteration. Author's analysis. Image credits: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

We should observe that f1r is not necessarily the original first page. There is evidence that the manuscript has been re-bound, and that the pages are not in their original order. In the upper right corner of page f1r, we see the Arabic numeral 1 (which gives the page its modern numbering); but we are not obliged to assume that it was there when the manuscript was written.

However, if f1r is indeed the original first page, it seems to me a reasonable hypothesis that the three right-justified strings of glyphs have some special significance. We might conjecture that they represent names: for example, of patrons, producers, authors, or scribes. We have no way of knowing how many people were involved in the conception of the manuscript. But Dr Lisa Fagin Davis has identified five scribes: of whom Scribes 1, 2 and 3 contributed 188 of the 227 pages.

{98ayai29}

With that preamble: I propose here to examine the first string of glyphs, on line 6, represented in the v101 transliteration by {98ayai29}. Referring to the manuscript as it appears on the website of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, I could also read this string as {98ayai39} or {98ayai59}, although the glyphs {3} and {5} are much less common than {2}. I could also accept the possibility that the glyph {2} is a {1} with an accent of unknown significance, and if so, I could read the string as {98ayai1’9}.

This glyph string has some unusual properties.

Firstly, the string is unique. It occurs nowhere else in the manuscript: neither as a “word”, nor as a string within a “word”. It is, in linguists’ terminology, a hapax legomenon. That might permit us to suspect that it represents a proper name.

Secondly, the string does not confirm to the rules of sequencing glyphs within “words”, which Mary D’Imperio called the “five states”, and which Massimilano Zattera, in his presentation to the Voynich 2022 conference, called the “slot alphabet”. Zattera demonstrated that over 98 percent of the “words” in the Voynich manuscript conform to rules of this nature, or can be disaggregated into chunks which so conform. But this string does not. Below are the glyphs which make up the string, and the permitted slots which, according to Zattera, they may occupy.

Voynich manuscript, page f1r, line 6: glyphs and permitted Zattera "slots”. Author’s analysis.

We can see that, even allowing for the flexibility of the glyphs {8}, {9} and {y}, we cannot allocate glyphs to slots in such a way that each glyph is followed by a glyph in the same or a higher slot.

We therefore have to conjecture that the string is not a “word”, but may consist of several “words”, with the word breaks omitted or suppressed. This conjecture is easy to test. We can parse the string {98ayai29} in various ways. For each parsing, we can see whether it produces “words” that exist elsewhere in the Voynich manuscript, and that conform to the slot sequence.

Below is a summary of the tests that I have conducted so far.

Four ways of parsing the v101 glyph string {98ayai29}; the permitted slots in Zattera's "slot alphabet"; and the “word” counts of each parsed segment in the v101 transliteration. Author’s analysis.

From these results, it seems to me that, if the Voynich scribes intended the string {98ayai29} to conform to the slot sequence, we might infer the following:

• the final {29} must be a separate “word”;Here we may note that the “word” {8ay} is part of a family of common Voynich “words” which includes the ubiquitous [8am} as well as {8an}, {8aM} and {8ae}.

• as for the rest of the string, the parsing which yields the most real “words” has {9} as a single-glyph “word”, and {8ay} as another “word”.

Thus, to my mind, if the string is part of the Voynich vocabulary, the most plausible parsing is {9 8ay ai 29}. However, that would still leave {ai} as a non-existent “word”; and we cannot break it further, since {i} never occurs as a single-glyph “word”.

A proper name?

Alternatively, we might conjecture that the string {98ayai29} is not part of the Voynich vocabulary: that is to say, it is not a normal word in the (presumed) precursor language or languages of the manuscript. For the Voynich scribes, it might have been a proper name, or even a foreign word.

In previous articles on this platform, I have advanced the hypothesis that the producer of the Voynich manuscript provided the scribes with source documents in natural languages; a set of mappings from letters to glyphs; and also a set of rules, applied after mapping, for re-ordering the glyphs within “words”. To my mind, these are plausible mechanisms to explain the sequencing of glyphs within “words”, which to my knowledge, does not occur in any natural language.

We might now imagine the scribes faced with an unusual word (that is, either a proper name, or a word from a language other than the primary precursor languages). In such a case, perhaps they would not, or could not, apply their normal rules. For example, they might apply the mapping from letters to glyphs, but omit the re-ordering of glyphs.

In any case, we have nothing to lose by attempting a mapping from the string {98ayai29} to some potential source languages.

In any such mapping, I prefer to avoid or at least to minimise the element of subjectivity, and to examine a range of possible languages, as well as a range of possible transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. For each language and for each transliteration, frequency analysis can be a guide as to how we map a glyph to a letter.

I started with medieval Italian, if only because in previous work, this language had shown promise as a possible precursor of the Voynich text. For example, as I reported in a previous article, several of my variant transliterations yielded mappings of the glyph string {8am} to the Italian words CON (“with”) or alternatively DIO (“God”). Against Italian, it might be argued that if the main text were in Italian, then the right-justified strings on page f1r could be in another language. Anyway, I thought it worth a try.

Below are selected mappings that came closest to yielding pronounceable words:

Selected transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, and corresponding mappings of the glyph string {98ayai29} to text strings in medieval Italian. RSQ = correlation between glyph frequencies and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference in frequencies between glyphs and equally-ranked letters. Author’s analysis.

I have to admit that none of these text strings is, to my knowledge, a word or a proper name in medieval Italian. But it seems to me that there are possibilities to be explored, along the following lines:

• other variants of the transliteration of the Voynich manuscript (which will have slightly different glyph frequencies, therefore slightly different rankings of the glyphs, therefore slightly different mappings between glyphs and the Italian letters)Next steps

• parsing the glyph string as implied by the “slot alphabet”; for example, in the v151 transliteration, the parsed sequence (9 8ay ai 29} maps to A NOS OY MA; and we could consider re-ordering NOS as SON, and so on;

• and of course, there are other languages to be tried: as I have suggested in other articles, I am inclined to give priority to languages used in or near medieval Italy, for example, Latin, French or Albanian.

I invite any readers who may be interested to explore this approach. If any reader should favor a specific language as the precursor of the glyph string {98ayai29}, and if I have a sufficiently large corpus of text in that language, I will be happy to supply a proposed mapping from glyphs to letters.

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 67 followers