Voynich Reconsidered: mappings of {8am}

In Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Publishing, 2024) and in various articles on this platform, I presented the results of some of my experiments in mapping from “words” in the Voynich manuscript to letter strings in natural languages.

In all of these experiments, my working assumptions (and they are no more than that) included the following:

In addition I suspected, on the basis of the work of Mary D'Imperio and Massimiliano Zattera, that the glyphs that we could see on the page were not in their original order. That is, the Voynich producer had specified a process, after the mapping from letters to glyphs, of re-ordering glyphs within “words”.

The assumption of a one-to-one mapping between letters and glyphs permits a corollary: that the Voynich text preserved the frequencies of letters in the precursor documents. That is, the glyph frequencies in the Voynich manuscript should approximately match the typical letter frequencies in the precursor languages.

Permutations

In these experiments, there were at least three permutations to consider.

Firstly, there were multiple languages to test as precursors. A priori, there was no definitive way to include or exclude a language. But the carbon-dating of samples of the vellum to the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and the presumption that Wilfrid Voynich rediscovered the manuscript in Italy, suggested a focus on medieval European languages. As priorities, I was inclined to favor the languages spoken and written in medieval Italy or in neighboring countries.

Secondly, I had developed multiple transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, all based on Glen Claston's v101, each with one or more variations from v101. There were several metrics whereby I could rank these transliterations: for example the statistical correlation between letter and glyph frequencies, and the average absolute difference between letter and glyph frequencies.

The third variable was: which samples of the text should be tested? There were many possibilities, for example the following:

Focus on {8am}

It seemed to me that a more efficient strategy would be to focus on a single very common “word” in the Voynich manuscript. It would be feasible to map such a “word” from multiple transliterations to multiple precursor languages. Each mapping would yield a string of letters; that string could be checked against a suitable corpus of the precursor language; it might yield a real word; and if so, it might be a common word, or a rare word.

For this strategy, one Voynich “word” came to the forefront: the “word” expressed in v101 as {8am}. It is the most common word in the Voynich manuscript; in the v101 transliteration, it occurs 739 times.

The Voynich “word” {8am}, rendered in the Voynich v101 font. Image credit: Rebecca G Bettencourt / KreativeKorp.

Here it was necessary to recognise that the v101 glyph {m} might not be a single glyph. In the EVA transliteration, {m} is rendered as a three-glyph string {iin}; so {8am} becomes the five-glyph string {daiin}. Likewise, in several of my transliterations, I rendered {8am} as the four glyphs {8aîn} or as the five glyphs {8aiiń}. I viewed these renderings as improbable, because to my knowledge, there are no natural languages in which the most common word has four or five letters. But these interpretations could be tested.

Re-ordering the glyphs

I wished to address the possibility to which I referred above (indeed, I thought that it approached a probability) that within the Voynich “words”, the scribes had re-ordered the glyphs. If so, I could conjecture that the producer had defined some rule or rules for re-ordering. These rules needed to be relatively simple, so that the producer could set the project in motion and the scribes could proceed with minimal supervision. Some illustrations may clarify this concept.

Mary D'Imperio, in her classified research for the National Security Agency around 1978, used a computer program called PTAH to categorise the glyphs according to their typical position within the “word”. She defined at least five positions; her research results, as eventually published, suggest that ultimately she recognised seven. She called these positions, for example, “beginners”, “post-beginners”, “middles” and “enders”. If we visualise the Voynich workplace, we can imagine the producer giving instructions to the scribes along the following lines:

This means a search for anagrams; and that is a slippery slope. Anagrams lead us into a world of subjectivity. A four-letter word has twenty-four anagrams; if we are willing to accept any of them, we have twenty-four degrees of freedom.

Fortunately, that freedom is constrained. In natural languages, words have rules regarding sequences of letters. In most languages, words have to include vowels; and they seldom have more than two consecutive consonants. As Boris Sukhotin observed, and made the core of his eponymous algorithm, in a phonetic language a vowel, more often than not, is preceded and followed by a consonant.

For example: in Italian as written before the year 1400, the most common four-letter word was “come” (in English, “as” or “how”). This word has twenty-four anagrams, but among them, the only real word is “come”. If (for the sake of argument) the precursor language were Italian, and if we mapped a Voynich “word” to any anagram of “come”, the precursor word could only be “come”.

The first mappings

In the implementation of this strategy, I started with four potential precursor languages, as follows:

I was able quickly to exclude Finnish, in which {8am} and its variants in most cases mapped only to strings of consonants. The mappings to German yielded many strings of letters which included the vowel “u”, but none of these strings, nor any of their anagrams, was a real word. The mappings to Italian, on the basis of the letter frequencies in La Divina Commedia, yielded only the words “don” (1,241 occurrences in the OVI corpus) and “mond” (106 occurrences in OVI), plus a few rare words.

The most encouraging result came from the mappings to Italian using the letter frequencies in OVI. These frequencies are only slightly different from those in La Divina Commedia, but are based on a much larger corpus of text.

In eighteen of the thirty-seven transliterations, the “word” {8am} mapped to the letter string “noc” or “onc”; and in four transliterations, to the letter string “roc”. None of these strings is a word in Italian, at least not in OVI. But “roc” can be re-ordered as “cor”, a real word which occurs 4,436 times in OVI, and is the old form of “cuore” (in English, “heart”). Better still, “noc” and “ocn” can be re-ordered in only one way as a real Italian word. That word is “con”, which occurs 135,186 times in OVI and translates to English as “with”.

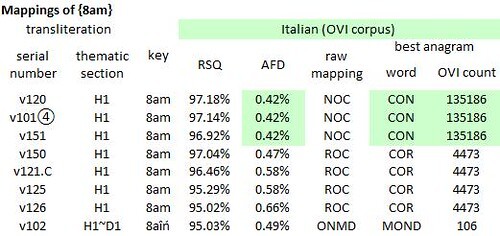

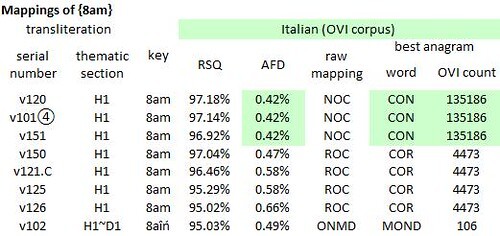

A series of mappings of [8am} from various transliterations of the Voynich manuscript to medieval Italian, as represented by the OVI corpus. Author's analysis. H1 = “herbal” section, parts A and B. D1 = Scribe 1 (per Dr Lisa Fagin Davis). RSQ = correlation coefficient between glyph and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference between glyph and letter frequencies.

Next steps

None of this means that Italian is necessarily or even probably a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript. To my mind, however, it suggests that a systematic process exists whereby, with a minimum of subjectivity, we can rank and prioritise transliterations and precursor languages. If one transliteration and one language emerge from the pack, yielding more real words than others, we can focus on that transliteration and that language.

At present I am working on mappings of {8am} to Albanian, Bohemian, English, French, Galician-Portuguese and Latin, each language represented by an appropriate medieval corpus or document. These tests may, or may not, generate more common words than the Italian "con".

The next step would be to map some other ubiquitous “words” in the Voynich manuscript, such as {oe} and {am}; and to see whether we can make some more real words in the target language. If several common Voynich “words” can be mapped to real words in some language, we might venture onwards, to mappings of whole lines. Those mappings would have to make sense.

In all of these experiments, my working assumptions (and they are no more than that) included the following:

* that the Voynich text, or some substantial part of it, possessed meaning;All of this, I imagined as the vision of a producer: a wealthy person who had conceived and paid for the project, and had given these instructions to the scribes.

* that the Voynich scribes had worked from precursor documents in natural languages;

* that they had mapped words in the precursor documents to “words” in the Voynich manuscript; that is to say, they had preserved the word breaks;

* and that they had mapped letters to glyphs on a one-to-one basis.

In addition I suspected, on the basis of the work of Mary D'Imperio and Massimiliano Zattera, that the glyphs that we could see on the page were not in their original order. That is, the Voynich producer had specified a process, after the mapping from letters to glyphs, of re-ordering glyphs within “words”.

The assumption of a one-to-one mapping between letters and glyphs permits a corollary: that the Voynich text preserved the frequencies of letters in the precursor documents. That is, the glyph frequencies in the Voynich manuscript should approximately match the typical letter frequencies in the precursor languages.

Permutations

In these experiments, there were at least three permutations to consider.

Firstly, there were multiple languages to test as precursors. A priori, there was no definitive way to include or exclude a language. But the carbon-dating of samples of the vellum to the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and the presumption that Wilfrid Voynich rediscovered the manuscript in Italy, suggested a focus on medieval European languages. As priorities, I was inclined to favor the languages spoken and written in medieval Italy or in neighboring countries.

Secondly, I had developed multiple transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, all based on Glen Claston's v101, each with one or more variations from v101. There were several metrics whereby I could rank these transliterations: for example the statistical correlation between letter and glyph frequencies, and the average absolute difference between letter and glyph frequencies.

The third variable was: which samples of the text should be tested? There were many possibilities, for example the following:

* a line from page f1r, the first page of the manuscript, which Prescott Currier assigned to his “Language A”My tests incorporated multiple combinations of languages, transliterations and text samples. In the early experiments, the text samples were generally whole horizontal lines. Each mapping yielded text strings in the selected precursor language. Usually, the text strings did not make sense; in many cases, the text strings did not contain any recognisable words in the target precursor language.

* a line from page f26r, the first page in Currier's “Language B”

* a random line from each of the thematic “sections” of the manuscript: for example “herbal”, “pharmaceutical”, “zodiac”

* a random line from a random page of the manuscript

* and so on …

Focus on {8am}

It seemed to me that a more efficient strategy would be to focus on a single very common “word” in the Voynich manuscript. It would be feasible to map such a “word” from multiple transliterations to multiple precursor languages. Each mapping would yield a string of letters; that string could be checked against a suitable corpus of the precursor language; it might yield a real word; and if so, it might be a common word, or a rare word.

For this strategy, one Voynich “word” came to the forefront: the “word” expressed in v101 as {8am}. It is the most common word in the Voynich manuscript; in the v101 transliteration, it occurs 739 times.

The Voynich “word” {8am}, rendered in the Voynich v101 font. Image credit: Rebecca G Bettencourt / KreativeKorp.

Here it was necessary to recognise that the v101 glyph {m} might not be a single glyph. In the EVA transliteration, {m} is rendered as a three-glyph string {iin}; so {8am} becomes the five-glyph string {daiin}. Likewise, in several of my transliterations, I rendered {8am} as the four glyphs {8aîn} or as the five glyphs {8aiiń}. I viewed these renderings as improbable, because to my knowledge, there are no natural languages in which the most common word has four or five letters. But these interpretations could be tested.

Re-ordering the glyphs

I wished to address the possibility to which I referred above (indeed, I thought that it approached a probability) that within the Voynich “words”, the scribes had re-ordered the glyphs. If so, I could conjecture that the producer had defined some rule or rules for re-ordering. These rules needed to be relatively simple, so that the producer could set the project in motion and the scribes could proceed with minimal supervision. Some illustrations may clarify this concept.

Mary D'Imperio, in her classified research for the National Security Agency around 1978, used a computer program called PTAH to categorise the glyphs according to their typical position within the “word”. She defined at least five positions; her research results, as eventually published, suggest that ultimately she recognised seven. She called these positions, for example, “beginners”, “post-beginners”, “middles” and “enders”. If we visualise the Voynich workplace, we can imagine the producer giving instructions to the scribes along the following lines:

* You have mapped a word in (say) Italian into a “word” in glyphs. But these glyphs must be written in a specific order.Massimiliano Zattera, in his presentation at the Voynich 2022 conference, took this concept further. Where D'Imperio had identified seven positions, he saw twelve. He numbered them from zero to eleven; he called them “the slot alphabet”. Zattera's version of the Voynich producer would have given instructions somewhat like the following:

* If your “word” contains a “beginner” glyph, you must write that glyph first.

* If it contains a “middle” and a “beginner” glyph, you must write the “beginner” before the “middle”.

* If it contains a “ender” and an “middle” glyph, you must write the “middle” before the “ender”.

* and so on …

* If your “word” contains a “slot 0” glyph, you must write that glyph first.If D'Imperio and Zattera identified a real Voynich process, it follows that the glyphs are not necessarily in their original order. When we attempt to reverse-engineer a Voynich “word” to its precursor word, in the first instance we create a letter string which is not necessarily in the right order. Therefore, we may have have to re-order the letters.

* If it contains a “slot 4” and a “slot 3” glyph, you must write the “slot 3” before the “slot 4”.

* If it contains a “slot 11” and a “slot 7” glyph, you must write the “slot 7” before the “slot 11”.

* and so on …

This means a search for anagrams; and that is a slippery slope. Anagrams lead us into a world of subjectivity. A four-letter word has twenty-four anagrams; if we are willing to accept any of them, we have twenty-four degrees of freedom.

Fortunately, that freedom is constrained. In natural languages, words have rules regarding sequences of letters. In most languages, words have to include vowels; and they seldom have more than two consecutive consonants. As Boris Sukhotin observed, and made the core of his eponymous algorithm, in a phonetic language a vowel, more often than not, is preceded and followed by a consonant.

For example: in Italian as written before the year 1400, the most common four-letter word was “come” (in English, “as” or “how”). This word has twenty-four anagrams, but among them, the only real word is “come”. If (for the sake of argument) the precursor language were Italian, and if we mapped a Voynich “word” to any anagram of “come”, the precursor word could only be “come”.

The first mappings

In the implementation of this strategy, I started with four potential precursor languages, as follows:

* Finnish as written around 1548 (as represented by Uusi Testamentti (The New Testament)and with thirty-seven alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript, which I numbered from v101④ to v202.

* Early New High German as written around 1401 (as represented by von Tepl's Der Ackerman aus Böhmen)

* Italian as written around 1308-21 (as represented by Dante's La Divina Commedia)

* Italian as written prior to 1400 (as represented by the OVI corpus, or Opera del Vocabolario Italiano),

I was able quickly to exclude Finnish, in which {8am} and its variants in most cases mapped only to strings of consonants. The mappings to German yielded many strings of letters which included the vowel “u”, but none of these strings, nor any of their anagrams, was a real word. The mappings to Italian, on the basis of the letter frequencies in La Divina Commedia, yielded only the words “don” (1,241 occurrences in the OVI corpus) and “mond” (106 occurrences in OVI), plus a few rare words.

The most encouraging result came from the mappings to Italian using the letter frequencies in OVI. These frequencies are only slightly different from those in La Divina Commedia, but are based on a much larger corpus of text.

In eighteen of the thirty-seven transliterations, the “word” {8am} mapped to the letter string “noc” or “onc”; and in four transliterations, to the letter string “roc”. None of these strings is a word in Italian, at least not in OVI. But “roc” can be re-ordered as “cor”, a real word which occurs 4,436 times in OVI, and is the old form of “cuore” (in English, “heart”). Better still, “noc” and “ocn” can be re-ordered in only one way as a real Italian word. That word is “con”, which occurs 135,186 times in OVI and translates to English as “with”.

A series of mappings of [8am} from various transliterations of the Voynich manuscript to medieval Italian, as represented by the OVI corpus. Author's analysis. H1 = “herbal” section, parts A and B. D1 = Scribe 1 (per Dr Lisa Fagin Davis). RSQ = correlation coefficient between glyph and letter frequencies. AFD = average absolute difference between glyph and letter frequencies.

Next steps

None of this means that Italian is necessarily or even probably a precursor language of the Voynich manuscript. To my mind, however, it suggests that a systematic process exists whereby, with a minimum of subjectivity, we can rank and prioritise transliterations and precursor languages. If one transliteration and one language emerge from the pack, yielding more real words than others, we can focus on that transliteration and that language.

At present I am working on mappings of {8am} to Albanian, Bohemian, English, French, Galician-Portuguese and Latin, each language represented by an appropriate medieval corpus or document. These tests may, or may not, generate more common words than the Italian "con".

The next step would be to map some other ubiquitous “words” in the Voynich manuscript, such as {oe} and {am}; and to see whether we can make some more real words in the target language. If several common Voynich “words” can be mapped to real words in some language, we might venture onwards, to mappings of whole lines. Those mappings would have to make sense.

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 67 followers