Voynich Reconsidered: what is a "word"

The Voynich manuscript contains, in addition to its profuse illustrations, over 150,000 glyphs arranged in strings which have the appearance of text. That is to say, the glyph strings are generally delimited to left and right by line breaks, or by intervening illustrations, or by spaces. In most of my research, I have been inclined to regard strings of glyphs, thus delimited, as “words” – or the equivalent of words in natural languages.

My assumptions (and they are no more than that) have been that word breaks occur in the following places:

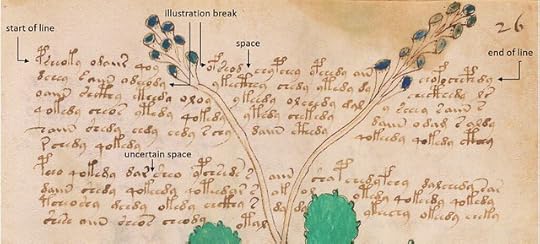

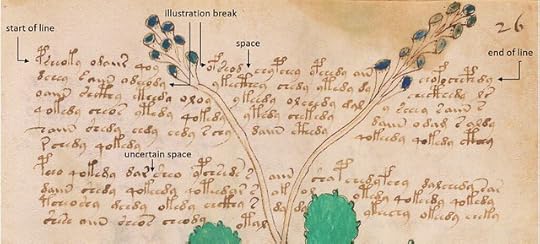

An extract from page f026r of the Voynich manuscript, identifying various types of presumed "word" break. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; additional graphics and legend by author.

On the basis of these assumptions, a considerable part of my research has been devoted to testing the lengths, frequencies, distributions and placement of Voynich “words” in comparison with the words in natural languages.

However, these assumptions are open to question. Captain Prescott Currier said as much in Mary D’Imperio’s path-breaking seminar on the Voynich manuscript in 1976:

Hapax legomena

A word, by definition, has meaning. If we are searching for words in the Voynich manuscript, we are searching for meaning.

Here I am indebted to Alexander Boxer’s paper “Fingerprinting Gibberish” in the Voynich 2022 Conference, sponsored by the University of Malta. Boxer used the phenomenon known as hapax legomena to distinguish meaningful text from nonsense or gibberish. The Greek expression hapax legomenon (plural: legomena), for which so far I have not found a colloquial English equivalent, simply means a word which occurs only once in a given body of text.

As an example of a meaningful text: my copy of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth contains 18,609 words including stage directions, making it somewhat comparable in length with the Voynich manuscript. Its vocabulary (the set of distinct words) contains 3,273 words. Of these, 1,321 (or 40 percent) occur at least twice. The five most common words, for example, are: "the" (732 occurrences), "and" (564), "to" (383), "I" (371), "of" (343). There are 1,932 words which occur only once (that is, hapax legomena); they include, for example: "clamorous", "unshrinking", "witchcraft". They are equivalent to 60 percent of the vocabulary of Macbeth.

As an example of a text which is universally acknowledged to be meaningless, Boxer cited the purported "angelic speech" as transcribed in "John Dee's Actions With Spirits (1581-1583)", also known as Sloane Manuscript 3188. This text contains passages such as "Asmar gehotha galseph achandas vnascor satquama". Nearly all the "words" occur exactly once. In several passages that I examined, the incidence of hapax legomena was 100 percent.

Boxer argued that the higher the proportion of hapax legomena, the more likely it was that the text, as written, was gibberish; and conversely, the lower the proportion of hapax legomena, the more likely it was that the text was meaningful. From his comparison of the Voynich manuscript with Sloane 3188, and with selected meaningful texts from classical and medieval literature, he concluded that the text of the Voynich manuscript was more likely to be meaningful than to be meaningless.

Them's the breaks

With this tool in hand, we may now turn to various ways of defining the words in the Voynich manuscript. If we start by defining the word breaks, then any string of glyphs delimited by consecutive word breaks, thus defined, is a “word”.

Here I would like to acknowledge my correspondence with Brian Corliss Tawney on the Facebook group “Decoding the Voynich Manuscript” at https://www.facebook.com/groups/62802....

Brian Tawney has developed a programming code which tests whether a given object in a text is or is not a word break. Applying this code to the Voynich text in Currier Language A, he concluded that in these pages, the space was indeed a word break, and that no other object functioned as a word break. With regard to the text in Currier Language B, his test did not confirm the space as a word break; but nor did any other object appear to function as a word break.

My test has a similar objective, but I have used the proportion of hapax legomena as a test for word breaks.

There is a straightforward procedure for doing this test. We copy a machine-readable transliteration of the Voynich text (I prefer Glen Claston’s v101) into Microsoft Word; convert all line breaks, illustration breaks and label breaks into spaces; convert all “uncertain spaces” (for which v101 makes a distinction) into spaces; and import the resulting text into any online word counter. I use the Browserling counter at https://www.browserling.com/tools/wor... no doubt there are others.

I applied this procedure to the text in Language B. This yielded the following results:

Glyphs as word breaks

What if certain glyphs are word breaks: either (a) instead of, or (b) in addition to, the conventional breaks?

We can test that hypothesis. The procedure for (a) would be to:

If any glyph functions as a word break, it must be a common glyph: simply because word breaks are very common in natural languages. In either case, therefore, I think that the prime candidate glyphs would be, in the v101 transliteration, {o}, {9}, {c} and {a}, which are the four most frequent glyphs in Language B and in the manuscript as a whole.

Below is a summary of a series of statistical tests which I conducted on the text in Language B.

The incidence of hapax legomena in the text in Language B, under various definitions of word breaks. The columns "average length of word" and "hapax legomena" are color-coded, with green denoting a greater probability of compatibility with meaningful documents in European languages.

The results for test (a), in which we drop the conventional breaks, include the following:

The latter result raises the possibility that some glyphs have no semantic meaning: for example, they could be some form of punctuation.

In other articles on this platform, I have presented some tests on what I call the “truncation effect”: the hypothesis that certain glyphs, in the initial or final positions, add no semantic meaning to the manuscript.

Separable words

Finally, I am indebted to Massimilano Zattera for his paper “A New Transliteration Alphabet Brings New Evidence of Word Structure and Multiple "Languages" in the Voynich Manuscript”, also presented at the Voynich 2022 Conference. As Zattera pointed out in his paper, the manuscript contains separable "words" (10.4% of the text, and 37.1% of the vocabulary, by his count). By this he means "words" which can be divided into two parts, each of which is a Voynich "word".

For example, the v101 "word" {2coehcc89} (which occurs only once) consists of two parts: {2coe} (50 occurrences) and {hcc89} (18 occurrences). In such cases we might conjecture that there is a word break, but it is not a space and it is not a glyph; it is invisible (as in "Grundwort" or any other compound word in German).

To my mind, the phenomenon of separable words provides further support for the hypothesis that Voynich “words” (or at least, most of them) are really words. With a complete list of separable words (which probably Zattera could provide), we could further refine our estimate of the incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript.

My assumptions (and they are no more than that) have been that word breaks occur in the following places:

• the left-hand and right-hand end of an approximately horizontal line, or of any line that has a clear beginning and endWe can call these points "the conventional breaks". That is, we can adopt the convention that if it looks like a word, then it is a word.

• any point at which a string of glyphs abuts an illustration

• the left-hand and right-hand end of any free-floating “label”

• any clearly defined space between strings of glyphs

• any "uncertain space" between strings of glyphs, if it appears larger than the typical spacing of consecutive glyphs.

An extract from page f026r of the Voynich manuscript, identifying various types of presumed "word" break. Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library; additional graphics and legend by author.

On the basis of these assumptions, a considerable part of my research has been devoted to testing the lengths, frequencies, distributions and placement of Voynich “words” in comparison with the words in natural languages.

However, these assumptions are open to question. Captain Prescott Currier said as much in Mary D’Imperio’s path-breaking seminar on the Voynich manuscript in 1976:

Question: “How do you account for the full-word repeats?”If the “words” in the Voynich manuscript are not words in the intuitive sense of those in a natural language, then research on the properties of the "words" will lead nowhere. It seems to me worthwhile, therefore, to pose the question: in the Voynich manuscript, what is a “word”?

Currier: “That's just the point - they're not words!”

Hapax legomena

A word, by definition, has meaning. If we are searching for words in the Voynich manuscript, we are searching for meaning.

Here I am indebted to Alexander Boxer’s paper “Fingerprinting Gibberish” in the Voynich 2022 Conference, sponsored by the University of Malta. Boxer used the phenomenon known as hapax legomena to distinguish meaningful text from nonsense or gibberish. The Greek expression hapax legomenon (plural: legomena), for which so far I have not found a colloquial English equivalent, simply means a word which occurs only once in a given body of text.

As an example of a meaningful text: my copy of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth contains 18,609 words including stage directions, making it somewhat comparable in length with the Voynich manuscript. Its vocabulary (the set of distinct words) contains 3,273 words. Of these, 1,321 (or 40 percent) occur at least twice. The five most common words, for example, are: "the" (732 occurrences), "and" (564), "to" (383), "I" (371), "of" (343). There are 1,932 words which occur only once (that is, hapax legomena); they include, for example: "clamorous", "unshrinking", "witchcraft". They are equivalent to 60 percent of the vocabulary of Macbeth.

As an example of a text which is universally acknowledged to be meaningless, Boxer cited the purported "angelic speech" as transcribed in "John Dee's Actions With Spirits (1581-1583)", also known as Sloane Manuscript 3188. This text contains passages such as "Asmar gehotha galseph achandas vnascor satquama". Nearly all the "words" occur exactly once. In several passages that I examined, the incidence of hapax legomena was 100 percent.

Boxer argued that the higher the proportion of hapax legomena, the more likely it was that the text, as written, was gibberish; and conversely, the lower the proportion of hapax legomena, the more likely it was that the text was meaningful. From his comparison of the Voynich manuscript with Sloane 3188, and with selected meaningful texts from classical and medieval literature, he concluded that the text of the Voynich manuscript was more likely to be meaningful than to be meaningless.

Them's the breaks

With this tool in hand, we may now turn to various ways of defining the words in the Voynich manuscript. If we start by defining the word breaks, then any string of glyphs delimited by consecutive word breaks, thus defined, is a “word”.

Here I would like to acknowledge my correspondence with Brian Corliss Tawney on the Facebook group “Decoding the Voynich Manuscript” at https://www.facebook.com/groups/62802....

Brian Tawney has developed a programming code which tests whether a given object in a text is or is not a word break. Applying this code to the Voynich text in Currier Language A, he concluded that in these pages, the space was indeed a word break, and that no other object functioned as a word break. With regard to the text in Currier Language B, his test did not confirm the space as a word break; but nor did any other object appear to function as a word break.

My test has a similar objective, but I have used the proportion of hapax legomena as a test for word breaks.

There is a straightforward procedure for doing this test. We copy a machine-readable transliteration of the Voynich text (I prefer Glen Claston’s v101) into Microsoft Word; convert all line breaks, illustration breaks and label breaks into spaces; convert all “uncertain spaces” (for which v101 makes a distinction) into spaces; and import the resulting text into any online word counter. I use the Browserling counter at https://www.browserling.com/tools/wor... no doubt there are others.

I applied this procedure to the text in Language B. This yielded the following results:

• This text contains 25,122 “words”.If the Voynich “words”, as conventionally defined, are really words, then to my mind the incidence of hapax legomena is not far off from that in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. This encourages us to think that the text of the Voynich manuscript, or most of it, is meaningful.

• The text has a vocabulary of 5,762 distinct "words".

• The five most frequent "words" are {oe} with 555 occurrences, {am} with 543, {1c89} with 367, {ay} with 357, {oy} with 301, and {8am} with 280.

• Of the vocabulary “words”, 1,803 (31 percent) occur at least twice and 3,959 (69 percent) occur only once. Thus the incidence of hapax legomena is 69 percent.

Glyphs as word breaks

What if certain glyphs are word breaks: either (a) instead of, or (b) in addition to, the conventional breaks?

We can test that hypothesis. The procedure for (a) would be to:

1. replace the conventional breaks with an arbitrary character which v101 does not use, for example the hyphen (-)The procedure for (b) would be the same, but skipping step 1.

2. replace a selected glyph with a space

3. run the word counter

4. see whether the incidence of hapax legomena goes up or down.

If any glyph functions as a word break, it must be a common glyph: simply because word breaks are very common in natural languages. In either case, therefore, I think that the prime candidate glyphs would be, in the v101 transliteration, {o}, {9}, {c} and {a}, which are the four most frequent glyphs in Language B and in the manuscript as a whole.

Below is a summary of a series of statistical tests which I conducted on the text in Language B.

The incidence of hapax legomena in the text in Language B, under various definitions of word breaks. The columns "average length of word" and "hapax legomena" are color-coded, with green denoting a greater probability of compatibility with meaningful documents in European languages.

The results for test (a), in which we drop the conventional breaks, include the following:

• If we replace all the conventional breaks with any one of the v101 glyphs {o}, {9}, {c} or {4o}, we greatly increase the incidence of hapax legomena.The results for test (b), in which we retain the conventional breaks, include the following:

• It is evident that if we try successively less frequent glyphs as candidates for word breaks, the percentage of hapax legomena will further increase.

• So, an assumption that the word breaks are glyphs moves the manuscript in the direction of gibberish.

• If we treat any of the glyphs o, 9, c, a, 1, 8, h or 4o as an additional word break, we slightly decrease the incidence of hapax legomena.We could reasonably conclude, firstly that the conventional breaks are word breaks (that is, the Voynich "words" are really words); secondly, that glyphs, on their own, do not function as word breaks; thirdly that certain glyphs might sometimes function as additional word breaks.

• If we treat two or three of the glyphs o, 9, c or 4o as additional word breaks, we can significantly decrease the incidence of hapax legomena, but we make the words much shorter, perhaps implausibly so.

The latter result raises the possibility that some glyphs have no semantic meaning: for example, they could be some form of punctuation.

In other articles on this platform, I have presented some tests on what I call the “truncation effect”: the hypothesis that certain glyphs, in the initial or final positions, add no semantic meaning to the manuscript.

Separable words

Finally, I am indebted to Massimilano Zattera for his paper “A New Transliteration Alphabet Brings New Evidence of Word Structure and Multiple "Languages" in the Voynich Manuscript”, also presented at the Voynich 2022 Conference. As Zattera pointed out in his paper, the manuscript contains separable "words" (10.4% of the text, and 37.1% of the vocabulary, by his count). By this he means "words" which can be divided into two parts, each of which is a Voynich "word".

For example, the v101 "word" {2coehcc89} (which occurs only once) consists of two parts: {2coe} (50 occurrences) and {hcc89} (18 occurrences). In such cases we might conjecture that there is a word break, but it is not a space and it is not a glyph; it is invisible (as in "Grundwort" or any other compound word in German).

To my mind, the phenomenon of separable words provides further support for the hypothesis that Voynich “words” (or at least, most of them) are really words. With a complete list of separable words (which probably Zattera could provide), we could further refine our estimate of the incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript.

Published on April 27, 2024 09:06

•

Tags:

alexander-boxer, brian-corliss-tawney, john-dee, macbeth, mary-d-imperio, prescott-currier, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers