Voynich Reconsidered: Turkish as precursor

According to Ethel Lilian Voynich, her husband Wilfred Voynich discovered or purchased his eponymous manuscript in Frascati, Italy. In recent posts on this platform, I advanced the idea that wherever the manuscript was produced, it was more likely to have had a shorter journey to Frascati than a longer one. This is simply an example of the well-documented distance-decay hypothesis, whereby human interactions are more probable over short distances than over long ones.

Accordingly, I thought that if the Voynich manuscript had had precursor documents in natural languages, the most probable languages were those written and spoken within a specifiable geographical radius of Italy. Among such languages, those of the Romance group seemed the most promising; followed by those of the Germanic and Slavic groups. If we chose to cast our net wider within Europe, we could include languages of the Hellenic and Uralic groups.

The purpose of this article is to cast the net farther afield, to the periphery of medieval Europe, and to assess the possibility that the precursor language, or one of the precursor languages, of the Voynich manuscript was Turkish.

Radio-carbon analysis, performed on four samples of the vellum, yielded dates between 1400 and 1461, with standard errors of between 35 and 38 years. We might reasonably make the assumption (and it is no more than that) that the manuscript was written sometime in the fifteenth century. If so, and if its precursor documents were in Turkish, those documents would have been written in Ottoman Turkish.

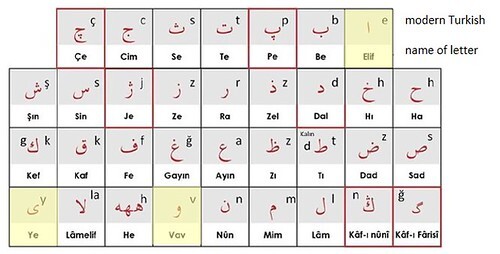

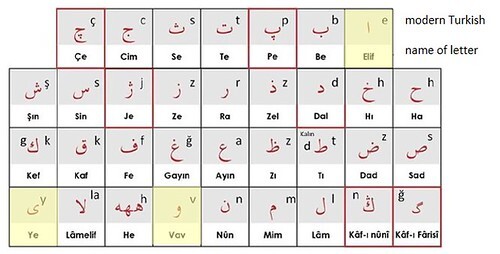

The letters in Ottoman Turkish, like those in Persian, were written in a variant of the Arabic script. This script was an abjad, in which the long vowels were written but the short vowels were not (except sometimes as diacritics above or below the letters).

The Ottoman Turkish alphabet. Image by courtesy of Bedrettin Yazan. Highlighted letters are long vowels, which can sometimes also serve as consonants.

In order to assess whether documents in Ottoman Turkish could have been a precursor of the Voynich text, I followed a variant of a strategy which I have outlined in other articles on this platform. The elements of the strategy were as follows:

Corpora of reference

My friend Mustafa Kamel Sen kindly provided a link to an archive of documents in Ottoman Turkish, held by Ataturk University, at https://archive.org/details/dulturk?&.... Among these were a number of documents by authors who lived in the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries.

These documents had been scanned by OCR software and required some cleaning to remove Latin letters and punctuation marks, as well as Arabic numerals, which had been misidentified by the software. A less tractable problem was that some of the original manuscripts had been written in a cramped or compact style, and the software often did not recognise the word breaks. For example, the OCR “word” فرآنوسنت is recognisable as two words by the final ن, and should have been فرآن وسنت. A consequence is that the average length of words, and the incidence of hapax legomena, are overstated.

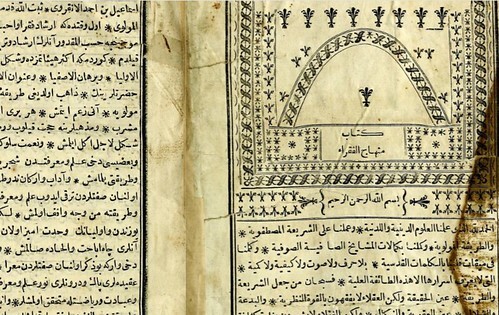

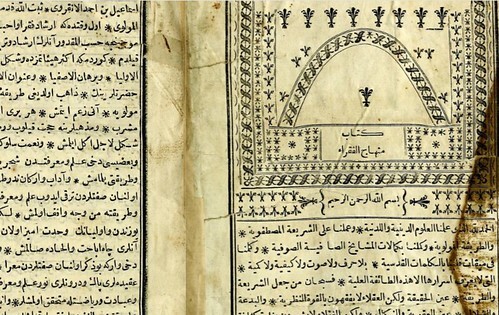

From these archives I selected, as a corpus of reference, Kitab-I Minhac ul-Fukara by Ismail Ankaravi. Although the title is an Arabic phrase, meaning approximately The Book of the Path of the Poor, the text is in Ottoman Turkish. Ankaravi wrote the book around 1624. The digitised edition, after my cleaning, has 71,232 words with 376,150 characters: equivalent to an average word length of 5.28 characters (as noted above, probably an over-estimate).

The first page of Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara. Image by courtesy of Duke University Libraries.

Transliterations and correlations

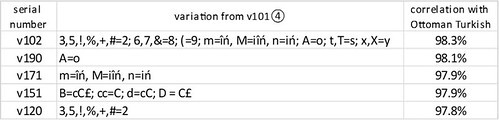

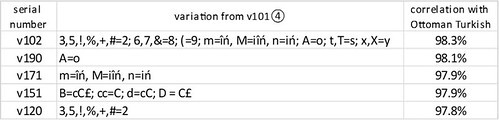

I calculated the Ottoman letter frequencies on the basis of the full text of Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara; and compared these with the glyph frequencies in twenty alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. In terms of correlations with the letter frequencies, the most promising transliterations were the following:

Correspondences

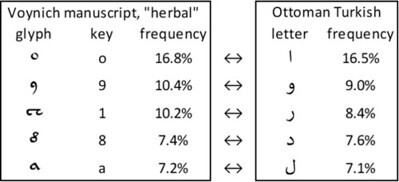

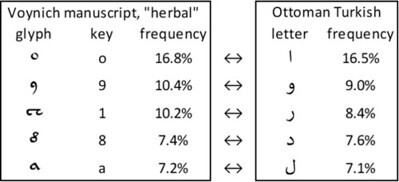

As a trial, I took the v102 transliteration as the best fit with Ottoman Turkish (this does not exclude alternative trials with other transliterations). As in my experiments with other languages, in order to have a reasonable assurance of mapping from a single language, I calculated the glyph frequencies on the basis of the “herbal” section of the Voynich manuscript.

The mappings of the five most frequent glyphs and letters, for example, were as follows:

The five most frequent glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v102 transliteration, “herbal” section; and the five most frequent letters in Kitab-I Minhac ul-Fukara. Author’s analysis.

Trial mappings

The next step was to select a suitable sample of Voynich text for the trial mappings.

One possible approach was to take a randomly selected line from the Voynich manuscript. However, I felt that this process was uncertain, since we do not know whether the whole of the manuscript contains meaning; it could be that some small or large part of the text is meaningless filler or junk. I thought it preferable, therefore, to take the most frequent “words”, map them to text strings in Ottoman Turkish, and see, by reference to the corpus, whether the resulting strings were real words.

In order to assess the abjad effect (of which, more below), I selected the most frequent Voynich “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs.

The results, in summary, are below.

The five most frequent “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v102 transliteration, “herbal” section; and trial mappings to text strings in Ottoman Turkish on the basis of frequency rankings. Author’s analysis.

We can see that the top five “words” of one glyph, the top five “words” of two glyphs, and the top two “words” of three glyphs, map to text strings which are real words in Kitab-I Minhac ul-Fukara. But thereafter the mapping breaks down. None of the less frequent “words” of three glyphs, and none of the “words” of four glyphs, maps to words in Ottoman Turkish.

In these results, I detect the abjad effect. Ottoman Turkish, like Arabic, Hebrew and Persian, is an abjad language, with no written short vowels. As I have demonstrated in my forthcoming book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer, 2024), in such a language, almost any random string of up to three letters is quite likely to be a real word.

With regard to the apparent words that I found: not being a speaker of Turkish, I do not know the English equivalents. I established only that these strings existed as words in Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara. Google Translate is no help, since it only works on modern Turkish. Readers of Turkish who also know the Ottoman script would be able to confirm whether these words are real.

In this light, I was not motivated to pursue a possible further step: namely, to attempt a mapping of a whole line of Voynich text to Ottoman Turkish. If “words” of four glyphs do not map to words, there is not much chance that lines of text will produce meaningful phrases.

In summary, I do not have an expectation that, through a systematic and objective process, it is possible to extract meaningful content in the Ottoman Turkish language from the Voynich manuscript.

Where next?

It would be possible to refine this process by selecting other corpora of reference than Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara; by testing other transliterations than v102, with comparable correlations; and by selecting other samples of Voynich text for mapping. I do not have much confidence that these variations would yield meaningful narrative text in Ottoman Turkish.

An alternative would be to recall Massimiliano Zattera’s discovery of the “slot alphabet”, with its quasi-rigid marching order of the glyphs within the Voynich “words”. We would then consider its near-inescapable corollary, that in nearly every Voynich “word”, the scribes mapped letters in some natural language to glyphs, and then re-ordered the glyphs from their original sequence. If so, the mapped text strings in Ottoman Turkish are not the last step; we would have to look for anagrams, which the Voynich scribes would have mapped to the identical Voynich “words”.

Here again, only speakers or readers of Ottoman Turkish could take this analysis to the next level.

Accordingly, I thought that if the Voynich manuscript had had precursor documents in natural languages, the most probable languages were those written and spoken within a specifiable geographical radius of Italy. Among such languages, those of the Romance group seemed the most promising; followed by those of the Germanic and Slavic groups. If we chose to cast our net wider within Europe, we could include languages of the Hellenic and Uralic groups.

The purpose of this article is to cast the net farther afield, to the periphery of medieval Europe, and to assess the possibility that the precursor language, or one of the precursor languages, of the Voynich manuscript was Turkish.

Radio-carbon analysis, performed on four samples of the vellum, yielded dates between 1400 and 1461, with standard errors of between 35 and 38 years. We might reasonably make the assumption (and it is no more than that) that the manuscript was written sometime in the fifteenth century. If so, and if its precursor documents were in Turkish, those documents would have been written in Ottoman Turkish.

The letters in Ottoman Turkish, like those in Persian, were written in a variant of the Arabic script. This script was an abjad, in which the long vowels were written but the short vowels were not (except sometimes as diacritics above or below the letters).

The Ottoman Turkish alphabet. Image by courtesy of Bedrettin Yazan. Highlighted letters are long vowels, which can sometimes also serve as consonants.

In order to assess whether documents in Ottoman Turkish could have been a precursor of the Voynich text, I followed a variant of a strategy which I have outlined in other articles on this platform. The elements of the strategy were as follows:

• to identify a suitable corpus of reference, in the form of a digitised text in Ottoman Turkish, of at least 40,000 words and ideally much more, preferably written in the fifteenth century;A further (but optional) step, in the event that real Ottoman words could be identified, would be to examine whether a line of Voynich text could be thus mapped to a sequence of words in Ottoman Turkish, and if so, whether the result would make any sense.

• to calculate the frequency distribution of the letters in the reference corpus;

• to calculate the correlations between the letter frequencies in the Ottoman Turkish and the glyph frequencies in a range of alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript; to select the best-fitting transliteration; and thereby to develop a provisional mapping between Ottoman letters and Voynich glyphs;

• to identify the most frequent “words” in the selected Voynich transliteration, and to map them, letter by letter, to text strings in Ottoman Turkish;

• to search for those text strings in the Ottoman corpus of reference, with a view to identifying whole words.

Corpora of reference

My friend Mustafa Kamel Sen kindly provided a link to an archive of documents in Ottoman Turkish, held by Ataturk University, at https://archive.org/details/dulturk?&.... Among these were a number of documents by authors who lived in the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries.

These documents had been scanned by OCR software and required some cleaning to remove Latin letters and punctuation marks, as well as Arabic numerals, which had been misidentified by the software. A less tractable problem was that some of the original manuscripts had been written in a cramped or compact style, and the software often did not recognise the word breaks. For example, the OCR “word” فرآنوسنت is recognisable as two words by the final ن, and should have been فرآن وسنت. A consequence is that the average length of words, and the incidence of hapax legomena, are overstated.

From these archives I selected, as a corpus of reference, Kitab-I Minhac ul-Fukara by Ismail Ankaravi. Although the title is an Arabic phrase, meaning approximately The Book of the Path of the Poor, the text is in Ottoman Turkish. Ankaravi wrote the book around 1624. The digitised edition, after my cleaning, has 71,232 words with 376,150 characters: equivalent to an average word length of 5.28 characters (as noted above, probably an over-estimate).

The first page of Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara. Image by courtesy of Duke University Libraries.

Transliterations and correlations

I calculated the Ottoman letter frequencies on the basis of the full text of Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara; and compared these with the glyph frequencies in twenty alternative transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. In terms of correlations with the letter frequencies, the most promising transliterations were the following:

Correspondences

As a trial, I took the v102 transliteration as the best fit with Ottoman Turkish (this does not exclude alternative trials with other transliterations). As in my experiments with other languages, in order to have a reasonable assurance of mapping from a single language, I calculated the glyph frequencies on the basis of the “herbal” section of the Voynich manuscript.

The mappings of the five most frequent glyphs and letters, for example, were as follows:

The five most frequent glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v102 transliteration, “herbal” section; and the five most frequent letters in Kitab-I Minhac ul-Fukara. Author’s analysis.

Trial mappings

The next step was to select a suitable sample of Voynich text for the trial mappings.

One possible approach was to take a randomly selected line from the Voynich manuscript. However, I felt that this process was uncertain, since we do not know whether the whole of the manuscript contains meaning; it could be that some small or large part of the text is meaningless filler or junk. I thought it preferable, therefore, to take the most frequent “words”, map them to text strings in Ottoman Turkish, and see, by reference to the corpus, whether the resulting strings were real words.

In order to assess the abjad effect (of which, more below), I selected the most frequent Voynich “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs.

The results, in summary, are below.

The five most frequent “words” of one, two, three and four glyphs in the Voynich manuscript, v102 transliteration, “herbal” section; and trial mappings to text strings in Ottoman Turkish on the basis of frequency rankings. Author’s analysis.

We can see that the top five “words” of one glyph, the top five “words” of two glyphs, and the top two “words” of three glyphs, map to text strings which are real words in Kitab-I Minhac ul-Fukara. But thereafter the mapping breaks down. None of the less frequent “words” of three glyphs, and none of the “words” of four glyphs, maps to words in Ottoman Turkish.

In these results, I detect the abjad effect. Ottoman Turkish, like Arabic, Hebrew and Persian, is an abjad language, with no written short vowels. As I have demonstrated in my forthcoming book Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer, 2024), in such a language, almost any random string of up to three letters is quite likely to be a real word.

With regard to the apparent words that I found: not being a speaker of Turkish, I do not know the English equivalents. I established only that these strings existed as words in Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara. Google Translate is no help, since it only works on modern Turkish. Readers of Turkish who also know the Ottoman script would be able to confirm whether these words are real.

In this light, I was not motivated to pursue a possible further step: namely, to attempt a mapping of a whole line of Voynich text to Ottoman Turkish. If “words” of four glyphs do not map to words, there is not much chance that lines of text will produce meaningful phrases.

In summary, I do not have an expectation that, through a systematic and objective process, it is possible to extract meaningful content in the Ottoman Turkish language from the Voynich manuscript.

Where next?

It would be possible to refine this process by selecting other corpora of reference than Kitab-i Minhac ul-Fukara; by testing other transliterations than v102, with comparable correlations; and by selecting other samples of Voynich text for mapping. I do not have much confidence that these variations would yield meaningful narrative text in Ottoman Turkish.

An alternative would be to recall Massimiliano Zattera’s discovery of the “slot alphabet”, with its quasi-rigid marching order of the glyphs within the Voynich “words”. We would then consider its near-inescapable corollary, that in nearly every Voynich “word”, the scribes mapped letters in some natural language to glyphs, and then re-ordered the glyphs from their original sequence. If so, the mapped text strings in Ottoman Turkish are not the last step; we would have to look for anagrams, which the Voynich scribes would have mapped to the identical Voynich “words”.

Here again, only speakers or readers of Ottoman Turkish could take this analysis to the next level.

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Reader

(new)

Feb 09, 2025 03:04PM

My mother language is Turkish and as you know in Turkey, we learn Latin alphabet, but in my childhood, I’ll take some religious courses so I can read those Arabic letters so I can read ottoman Turkish as I say that those words have no meaning in Turkish…

My mother language is Turkish and as you know in Turkey, we learn Latin alphabet, but in my childhood, I’ll take some religious courses so I can read those Arabic letters so I can read ottoman Turkish as I say that those words have no meaning in Turkish…

reply

|

flag

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers