Voynich Reconsidered: them’s the breaks

Dante’s La Divina Commedia, in the Gutenberg edition, has 97,332 words. There are 8,083 words that occur just once in the entire narrative. Linguists refer to such words by the Greek term hapax legomenon, "said once" (plural: hapax legomena).

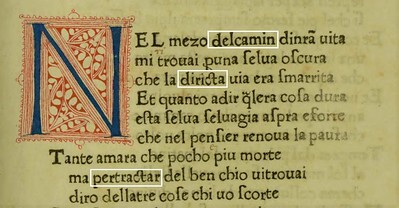

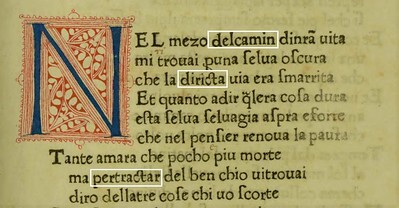

These words are not necessarily long, complex or obscure. In La Divina Commedia, some are quite short: examples are “acra”, “isso” and “rara”. In the first printed edition, dated 1472, on the first page, examples include “delcamin”, “diricta” and “pertractar”.

The incidence of hapax legomena in La Divina Commedia is 8.3 percent of the total word count.

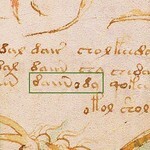

Three instances of hapax legomena in La Divina Commedia, Canto I, lines 1-9. Author’s analysis

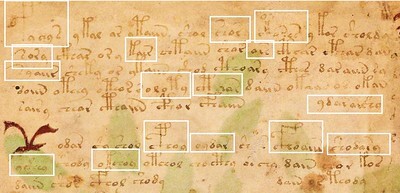

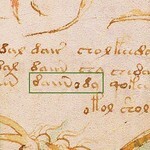

In the v101 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript, there are 40,704 “words”. Here I am using the term “word” to refer to a glyph string delimited by spaces, “uncertain spaces” or line breaks. There are 6,714 “words” which occur exactly once. In the first eight lines, there are at least sixteen cases of hapax legomena. The incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript is 16.5 percent of the total "word" count: almost double that in La Divina Commedia.

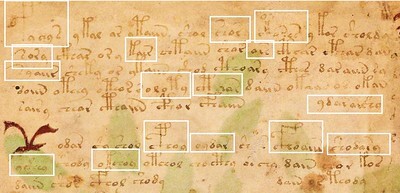

Sixteen examples of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript, page f1r, lines 1-8. Author’s analysis.

An anomalous vocabulary

As Prescott Currier said in 1976, at Mary D’Imperio’s Voynich seminar (although in a different context):

As Alexander Boxer observed in his presentation at the Voynich 2022 conference, the incidence of hapax legomena is linked to the length of the document. Other things being equal, a longer document will give more opportunities for a word to be re-used, and therefore will generally have a lower incidence of hapax legomena. Therefore, to assess whether the Voynich manuscript is anomalous, we need to look at documents of a similar length.

Below is a summary of the incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript, and in extracts of about 40,000 words from a selection of medieval European documents.

Incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript and in selected medieval European documents. Author's analysis.

We can see that the Voynich manuscript is an outlier, with a notably greater prevalence of hapax legomena than any of the comparator documents.

Separable "words"

One example may illustrate what a hapax legomenon looks like in the Voynich manuscript. The v101 “word” {8amo89} occurs just once: on line 8 of page f089r2. In English, if we see an uncommon word like "herein", we instinctively recognise the two components, "here" and "in". Likewise, if the researcher has a passing familiarity with the Voynich vocabulary, he or she will observe that the “word” {8amo89} has two parts: {8am} and {o89}. Both are common “words” in the Voynich manuscript: in the v101 transliteration, {8am} occurs 739 times and {o89} forty-five times.

We have to wonder if a construction like {8amo89} is not one “word” but two: in which the scribe chose to omit, or was instructed to omit, the space which would have marked a “word” break.

Here we return to Massimiliano Zattera’s presentation at the Voynich 2022 conference, and his concept of “separable words”: that is, “words” which can be divided into two (or maybe more) parts, each of which is a Voynich “word”. Zattera took a computational approach to the text, and worked with an abridged version of the EVA transliteration, in which he counted 31,317 “words”. He identified 3,249 occurrences of “words” which were separable. Each of these “words” could be split into two parts, each of at least two glyphs, and each of which was a real Voynich “word”.

Zattera required a "word" to have at least two glyphs. But among the v101 glyphs, there are at least forty-seven that sometimes occur with preceding and following spaces: that is, as “words”. If we allow one of the parts of a “word” to be a single glyph, the number of “separable words” will be substantially greater than Zattera’s estimate. If we also allow more than two parts of the “word”, the number of “separable words” will further increase.

The “slot alphabet” revisited

If our objective is mapping the glyphs to text in natural languages, and if the glyphs are in their original order, it will not much matter whether the “word” breaks are identifiable or not. For example, if miraculously we could map a line of Voynich text to the sequence “nelm ezode lcam indinr auita”, it would not take us long to see the medieval Italian phrase “nel mezo delcamin dinra uita”.

But Zattera’s principal finding was that in nearly all of the Voynich “words”, the glyphs followed a specific sequence, which he called the “slot alphabet”. In natural languages, to the best of my knowledge, a comparable marching order of letters within words is unknown. Therefore, as I have observed elsewhere on this platform, we have a powerful argument that within each Voynich “word”, the scribes re-ordered the glyphs.

To take an illustration from the English language: the first two words of the Gettysburg Address are “four score”. If in each word, we sort the letters alphabetically, the result is “foru ceors”: from which we can easily extract the original words. But if Abraham Lincoln had written “fourscore”, and an imaginary scribe had sorted the letters alphabetically, the result would be “cefoorrsu”. It would not be self-evident to reconstruct Lincoln’s “four score”: although with patience and a head for anagrams, we might do so.

If the glyphs have been re-ordered, we have to know where the “word” breaks are.

The breaks

In a previous article on this platform, I set out my ideas on a procedure for trial mappings of Voynich glyphs to text in natural languages. The first step was to identify the best fits between alternative transliterations and candidate languages; and to select suitable chunks of Voynich text for mapping. We now turn to the second step: establishing the “word” breaks.

Here, our ally is Zattera’s “slot alphabet”. There are twelve slots, numbered from 0 to 11. The rule is that within a Voynich “word”, a glyph can only be followed by a glyph in the same or a higher slot.

Among the lines of Voynich text that I selected for the trial mappings, one line contained the v101 “word” {soeham}. This “word” occurs only three times in the manuscript: it is not quite a hapax legomenon, but close. We therefore suspect it to be a “separable word”. We can check each glyph, and see what slots it can occupy; identify a sequence that conforms to the “slot” alphabet; and break the “word” at any point where it can be separated and maintain conformity. The result is as follows:

In this instance, the whole “word” conforms to the “slot alphabet”; there are five breakdowns that also conform. We can break after the {s), leaving {oeham} which occurs 28 times. We can break after {so}, leaving {eham} which is a more common “word”. If we break into {soe} and {ham}, these are even more common “words”. The breaks into {soeh} and {am}, and into {soeha} and {m}, do not work, since {soeh} and {soeha} are not “words”. We are encouraged to believe that the “word” {soeham} is actually two “words”: most probably {soe} and {ham}.

“Word” separation

Having constructed an algorithm for breaking down “separable words”, we may now return to the second step. We might capitalise it as the Second Step, since our task is akin to climbing Mount Everest.

To cut to the chase: below is an analysis of one of the eleven lines of text that I selected for the trial mappings, with “word” breaks inserted at the points where I saw the highest probability of generating the basic Voynich “words”: what we might call the building blocks of the manuscript.

These words are not necessarily long, complex or obscure. In La Divina Commedia, some are quite short: examples are “acra”, “isso” and “rara”. In the first printed edition, dated 1472, on the first page, examples include “delcamin”, “diricta” and “pertractar”.

The incidence of hapax legomena in La Divina Commedia is 8.3 percent of the total word count.

Three instances of hapax legomena in La Divina Commedia, Canto I, lines 1-9. Author’s analysis

In the v101 transliteration of the Voynich manuscript, there are 40,704 “words”. Here I am using the term “word” to refer to a glyph string delimited by spaces, “uncertain spaces” or line breaks. There are 6,714 “words” which occur exactly once. In the first eight lines, there are at least sixteen cases of hapax legomena. The incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript is 16.5 percent of the total "word" count: almost double that in La Divina Commedia.

Sixteen examples of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript, page f1r, lines 1-8. Author’s analysis.

An anomalous vocabulary

As Prescott Currier said in 1976, at Mary D’Imperio’s Voynich seminar (although in a different context):

“That’s just the point … they’re not words!”Considerations such as these encourage us to conjecture that the Voynich manuscript possesses an anomalous vocabulary. We might wonder, for example, if this vocabulary uses rare or obscure "words" to a much greater extent than other comparable documents of a similar time and place.

As Alexander Boxer observed in his presentation at the Voynich 2022 conference, the incidence of hapax legomena is linked to the length of the document. Other things being equal, a longer document will give more opportunities for a word to be re-used, and therefore will generally have a lower incidence of hapax legomena. Therefore, to assess whether the Voynich manuscript is anomalous, we need to look at documents of a similar length.

Below is a summary of the incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript, and in extracts of about 40,000 words from a selection of medieval European documents.

Incidence of hapax legomena in the Voynich manuscript and in selected medieval European documents. Author's analysis.

We can see that the Voynich manuscript is an outlier, with a notably greater prevalence of hapax legomena than any of the comparator documents.

Separable "words"

One example may illustrate what a hapax legomenon looks like in the Voynich manuscript. The v101 “word” {8amo89} occurs just once: on line 8 of page f089r2. In English, if we see an uncommon word like "herein", we instinctively recognise the two components, "here" and "in". Likewise, if the researcher has a passing familiarity with the Voynich vocabulary, he or she will observe that the “word” {8amo89} has two parts: {8am} and {o89}. Both are common “words” in the Voynich manuscript: in the v101 transliteration, {8am} occurs 739 times and {o89} forty-five times.

We have to wonder if a construction like {8amo89} is not one “word” but two: in which the scribe chose to omit, or was instructed to omit, the space which would have marked a “word” break.

Here we return to Massimiliano Zattera’s presentation at the Voynich 2022 conference, and his concept of “separable words”: that is, “words” which can be divided into two (or maybe more) parts, each of which is a Voynich “word”. Zattera took a computational approach to the text, and worked with an abridged version of the EVA transliteration, in which he counted 31,317 “words”. He identified 3,249 occurrences of “words” which were separable. Each of these “words” could be split into two parts, each of at least two glyphs, and each of which was a real Voynich “word”.

Zattera required a "word" to have at least two glyphs. But among the v101 glyphs, there are at least forty-seven that sometimes occur with preceding and following spaces: that is, as “words”. If we allow one of the parts of a “word” to be a single glyph, the number of “separable words” will be substantially greater than Zattera’s estimate. If we also allow more than two parts of the “word”, the number of “separable words” will further increase.

The “slot alphabet” revisited

If our objective is mapping the glyphs to text in natural languages, and if the glyphs are in their original order, it will not much matter whether the “word” breaks are identifiable or not. For example, if miraculously we could map a line of Voynich text to the sequence “nelm ezode lcam indinr auita”, it would not take us long to see the medieval Italian phrase “nel mezo delcamin dinra uita”.

But Zattera’s principal finding was that in nearly all of the Voynich “words”, the glyphs followed a specific sequence, which he called the “slot alphabet”. In natural languages, to the best of my knowledge, a comparable marching order of letters within words is unknown. Therefore, as I have observed elsewhere on this platform, we have a powerful argument that within each Voynich “word”, the scribes re-ordered the glyphs.

To take an illustration from the English language: the first two words of the Gettysburg Address are “four score”. If in each word, we sort the letters alphabetically, the result is “foru ceors”: from which we can easily extract the original words. But if Abraham Lincoln had written “fourscore”, and an imaginary scribe had sorted the letters alphabetically, the result would be “cefoorrsu”. It would not be self-evident to reconstruct Lincoln’s “four score”: although with patience and a head for anagrams, we might do so.

If the glyphs have been re-ordered, we have to know where the “word” breaks are.

The breaks

In a previous article on this platform, I set out my ideas on a procedure for trial mappings of Voynich glyphs to text in natural languages. The first step was to identify the best fits between alternative transliterations and candidate languages; and to select suitable chunks of Voynich text for mapping. We now turn to the second step: establishing the “word” breaks.

Here, our ally is Zattera’s “slot alphabet”. There are twelve slots, numbered from 0 to 11. The rule is that within a Voynich “word”, a glyph can only be followed by a glyph in the same or a higher slot.

Among the lines of Voynich text that I selected for the trial mappings, one line contained the v101 “word” {soeham}. This “word” occurs only three times in the manuscript: it is not quite a hapax legomenon, but close. We therefore suspect it to be a “separable word”. We can check each glyph, and see what slots it can occupy; identify a sequence that conforms to the “slot” alphabet; and break the “word” at any point where it can be separated and maintain conformity. The result is as follows:

In this instance, the whole “word” conforms to the “slot alphabet”; there are five breakdowns that also conform. We can break after the {s), leaving {oeham} which occurs 28 times. We can break after {so}, leaving {eham} which is a more common “word”. If we break into {soe} and {ham}, these are even more common “words”. The breaks into {soeh} and {am}, and into {soeha} and {m}, do not work, since {soeh} and {soeha} are not “words”. We are encouraged to believe that the “word” {soeham} is actually two “words”: most probably {soe} and {ham}.

“Word” separation

Having constructed an algorithm for breaking down “separable words”, we may now return to the second step. We might capitalise it as the Second Step, since our task is akin to climbing Mount Everest.

To cut to the chase: below is an analysis of one of the eleven lines of text that I selected for the trial mappings, with “word” breaks inserted at the points where I saw the highest probability of generating the basic Voynich “words”: what we might call the building blocks of the manuscript.

Published on March 04, 2024 10:31

•

Tags:

alexander-boxer, commedia, currier, d-imperio, dante, gettysburg, voynich, zattera

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers