Peter Rollins's Blog, page 8

March 27, 2016

The Devil is Real: Some thoughts on Debt, Grace and the Forgiveness of Sin

It’s Easter Sunday. A day when many reflect on the Resurrection and its relation to the seemingly obscure notion of “forgiveness of sin”.

I’ve explored this theme in various ways over the years, indeed my latest book offers a reading of what “forgiveness of sin” means without any of the mystification and obscurantism that comes from religious renderings of Christianity. So here, I’d like to expand briefly on my previous work by saying a few things about the Devil and how this diabolical character fits into the picture.

To approach the subject, we need to reflect briefly on anxiety.

Traditionally, anxiety has been viewed as the fear of nothing. Not a lack of fear, but rather a fear of nothingness itself. While we might be afraid of pain, for example, we will be anxious about death (death as a privileged symbol of lack). In a phobia we take some general anxiety and compress it into a fear. Just as a sub-atomic particle in superposition crunches into a position when measured, so our generalized anxiety is compacted into a concrete fear of moths, butterflies or mice.

Those who write on anxiety often note the various ways it manifests in our lives. Tillich, for instance, writes of three prime manifestations:

Guilt, meaninglessness and death.

This deep lack goes by different names. In psychoanalysis, it is expressed in the Death Drive; in existentialism, it raises its head under the name Alienation; in post-structuralism, it is connected with Différance; in theology, we call it sin.

However, the Christian tradition complicates the picture of anxiety as simply connected to lack. An idea hidden to most, but visible to Lacan.

One of his phenomenal insights is the idea that anxiety does have an object; albeit a rather strange one.

I won’t go into technical details in this post, but rather will attempt to express his idea in an analogy that might help us approach the idea of Resurrection.

Imagine we’ve bought a house that lost its value. The bank has taken it back and we’re left with a huge debt.

Debt is the economic name for lack. A debt is literally a nothingness: a lack that binds us to the bank, building society, mob or government. Something is missing – money (itself the material representation of debt, but that’s a thought for another time) that is demanded to fulfil the debt.

Technically, the debt is not what causes the anxiety. It is merely the condition for the anxiety. If we have moved to another country, we might be able to put the debt behind us. It is still there, but we don’t get any letters or phone calls, and no one calls round to our door demanding payment.

The anxiety is produced by the other who keeps reminding of us of our debt. The one who sends the letters, texts, and people to our door.

Sartre famously wrote of how our being involves nothingness. How we are all inhabited by a certain debt.

The point that Lacan makes is that this debt is only a cause of suffering when an other (the superego) keeps posting us letters reminding us of it.

As children, we inhabit a world where authorities of different stripes keep telling us what we should and should not be doing. These external authorities are gradually internalized and continue to haunt us by telling us that we aren’t good enough, that we aren’t rich enough, good looking enough, having enough fun. In short, that there is a lack within us that we need to fill.

The problem Freud pointed out is that the more we try to fulfil the demands of this authority, the more anxious we actually become. The beast cannot be satisfied by our achievements, for the beast feeds on our ever-increasing anxiety over not reaching our goals.

For Lacan (at least my reading of Lacan), anxiety is thus connected to this other who is always sending us letters that tell us how much we owe.

In theological terms, this other can be called the Devil. It is the other within us that constantly uses our anxiety/alienation/sin against us. Driving us deeper into despair by telling us we aren’t good enough.

In economic terms, bankruptcy is the name that is given to the loss of our debt. It is the rendering nothing of the nothing that enslaves us.

Of course, in the US, bankruptcy is not the full forgiveness of debt, and there are other strings attached. But it as close an analogy we have to the idea of forgiving a debt in our economic system. When one forgives a debt, one doesn’t pay it, but rather negates it. An ideal enshrined in the never realized year of Jubilee.

When one is bankrupt, the letters, phone calls and house visits stop. And with them, the anxiety that they produce dissipates. It is the loss of loss.

In a Religionless reading of Christianity, the Devil can therefore be described as the internal enslaving other that inhabits us, causing us very real suffering by reminding us of our lack.

The devil thus exists in the same way as society or the unconscious. Of course, if we take everyone out of the world, we will not find an object called “society”. However, society is an operative force that makes real demands on us. This is what is meant by structural racism. Individuals might not be racist, but they operate in a system that is. A system that dictates what schools they should send their kids to, where they should buy a house, drink, or socialize. In the same way, the unconscious is not something one finds in the brain, the unconscious names a structure that emerges from beings of desire and language. It does however have a spectral existence, as seen in Freudian slips, and is the object of study in psychoanalysis. Its existence is thus similar to the existence of imaginary numbers in mathematics.

Too many of us wrestle with the devil daily, and the challenge lies in defeating him through experiencing the interconnected realities of grace and forgiveness. Two structures that drain the devilish other of its operative power. This will be the theme of my next Building on Fire two-day event in LA. Although I haven’t finalised the dates yet. I’ll also be delving into in in my online Omega Course in June.

March 25, 2016

Christian Nihilism: Good Friday and the Primordial Chaos

In ikon we liked to play with different subtitles for the event. One of my favorites was “Ikon: Where everyday is Good Friday.”

While this was mainly a playful title reflecting the reputation ikon had for rather dark and disturbing themes, it also captured a deeper truth about what we had created.

The theological theory and technology that we were forging took seriously the idea that Easter symbolized the difficult move into a radically different type of existence. A move that brought us into a place that could be called, following, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “Religionless Christianity.”

From the perspective of Pyrotheology, Good Friday symbolizes a type of subtraction from the world of meaning. It exposes the contingent reality of all our religious and political regimes – even the universe itself – and plunges us into a type of deep nihilism.

Crucifixion originally represented the individual’s subtraction from the religious system because a crucified person was considered cursed of God. It also represented the individual’s subtraction from the political system because the crucified person was no longer considered a subject. To be crucified was to be stripped naked, both literally and figuratively, and left to rot outside the walls of the city. It meant that one was ripped away from the world of meaning and plunged into a dark oceanic horror of dizzying primordial chaos.

I’ll post something about Resurrection on Sunday, but let us not think that Sunday is a Monopoly card that gets us out of some cell. If anything, Good Friday is the “Get out of Jail free” card. It is that which helps us escape the prison-house of meaning. The Resurrection, from a pyrotheological perspective, is not some religious return of meaning (grounding us in a universal peace), but rather a religionless courage that equips us to bear the weight of the Cross. Finding meaning without the support of ultimate meaning. In other words, Resurrection does not point to the abolishing of Nihilism, but rather of a life that robs it of its sting.

In theological terms, Easter exposes how the Absolute is not the guarantee of meaning, but rather that which binds the body of activists together in works of love without guarantee.

One of the few explicitly theological texts I’ve come across that explores this disturbing idea is Christ and the End of Meaning by Paul Hessert. In my four-week online exploration of Religionless Christianity in June – The Omega Course – I’ll be delving into the searing insights of this work (among others).

Or, if you want to go as deep as you can into Religionless Christianity, you can always pick up one of the last two tickets for my Wake Festival in N. Ireland this April.

March 23, 2016

What Religion Should we Convert to? Leaving Christianity in the name of Christianity

Conversion is a central idea in Christianity, so what does it actually mean? This is a question that I’d love to write a book on some day, but in the mean time I’ll make occasional reflections here and in my other work.

Conversion is a central idea in Christianity, so what does it actually mean? This is a question that I’d love to write a book on some day, but in the mean time I’ll make occasional reflections here and in my other work.

Because the paradigmatic conversion story in the bible is that of Saul on the road to Damascus, we need to spend a little time dissecting it.

At the time of Saul, a small sect of Jews known as “Christians” were operating on the fringes of the religious structure. This sect was being persecuted by the religious authorities of the day who treated them as a problem that had to be eradicated.

In short, they were the scapegoat of the religious elite.

One important feature of scapegoating is the way in which the persecuted group is actually used to protect the persecutors from looking at their own issues. The internal problems of the dominant society are projected onto a group who are then blamed.

However, the scapegoat is not only the one who suffers at the hands of the powerful. They are also the holders of a secret knowledge. For they know what the wider society refuses to acknowledge. They know the unpleasant, repressed, violent truth of the system. Why? Because they experience that violent truth in their bodies.

For instance, young black women and men in America experience the racism that is denied by so many within the culture. They are judged, condemned and mistreated as if they are the problem, when the violence done to the black community really testifies to a violence within the system that attacks them.

As the site of truth, the scapegoat has the potential of being the place of genuine societal transformation. If we are able to listen to the outsider, who is downtrodden by our political, religious and cultural realities, we will be called to account, we will discover the disavowed violence within us and we will be lead to repentance.

In theological terms, the scapegoat is then the site of salvation, the very location of God.

When we read of Saul’s conversation we witness this realization. Something laid bare in the divine voice that says, “why do you persecute me?”

This leads Saul to repent and identify with the scapegoated community. An act that not only helps him, but also starts his quest for a community of equality (a collective of neither Jew nor gentile).

From here we can postulate the following idea concerning conversion. It is concerned with listening to the outsider who is downtrodden. Hearing their critique, drawing alongside them and allowing them to bring us to repentance.

Paul renounced his position of power and identified with the powerless.

In order to grasp the subversive meaning of conversion we should turn to the 2002 movie Amen directed by Costa-Gavras.

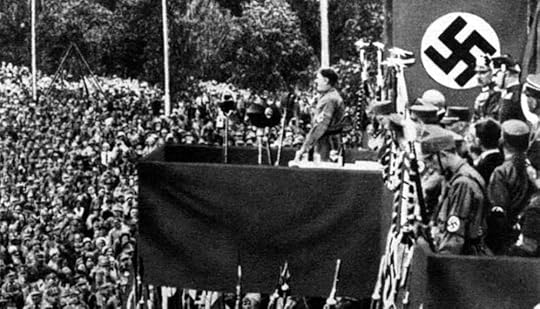

This movie explores the failure of the Catholic and Protestant church when confronted with the terror of the death camps during the Second World War. We are presented with two religious figures, a protestant youth pastor (Ulrich Tukur) and a catholic priest (Mathieu Kassovitz), who each attempt to inform their respective religious leaders of the genocide. In response, the churches struggle to retain their ignorance of the situation, wishing to retain their innocence by closing their eyes to the horror.

The response of the Priest is of particular interest: at one point he wonders aloud to the Cardinal (Michel Duchaussoy) whether it would be possible for every Christian in Germany to convert to Judaism in order to stop the horror, for the Nazis couldn’t possibly condemn such a huge number of powerful and socially integrated people at that stage in the war – the idea is of course utterly rejected. Then, in complete frustration, and with a crushing sense of obligation toward the persecuted, the Priest takes his own advice. In tears, he turns from that which he loves more than life itself – his own faith tradition – and radically identifies with his Jewish neighbors. By taking on the Jewish identity he suffers with the persecuted, voluntarily taking his place on the trains that run to Auschwitz.

In the same way that Saul radically identified with the persecuted group of his day, the Christians, so this Priest radically identified with the persecuted people of his day, the Jews.

The most powerful way for this Priest to affirm his Christianity was to lay it down – symbolised by the incongruous image in which he remains in his Cassock while wearing the Star of David. Here, in his very act of giving up Christianity, he reenacted the subversive act of conversion that lies at the heart of the Christian tradition.

The idea of arbitrarily converting to a different religion might seem absurd. But, if we reflect on the act of love for a moment, it might not seem so strange. A whole constellation of arbitrary conditions lie behind meeting the people we love, but, when we fall in love, it feels like a necessity has overcome us. We do not really think that we were destined to be together, but we feel that we are.

If we really love something, we embrace it fully and identify with it, all the while able to acknowledge that no deeper necessity underlies the commitment. The Priest’s own Christianity was an embrace of something utterly contingent (related to his upbringing, eduction, history etc.). Yet he embraced it as an ultimate concern, giving himself to it as if it was the truth. Just as a parent might embrace the contingent elements of their child’s face in such a way that they can claim it to be the most beautiful face in the world, so an individual might freely commit to the contingent religion they grew up with as the truth. This Priest was willing to reenact this logic of ultimate commitment without foundation because his heart wept over the injustice being done to his Jewish neighbor.

So the unnerving question we are left with is this – if we want to echo the spirit of Saul on the road to Damascus, what religion should we convert to?

March 19, 2016

The Omega Course, Online and in LA

After the success of Atheism for Lent, I’m busy working on an online version of The Omega Course that will be taking place in June. I’ve just launched the tickets and they’re selling fast. Here’s the description,

In 1977, Charles Marnham created a teaching series called The Alpha Course that was designed to introduce some basic elements of the Christian faith to people in his church. From its humble beginnings in Brompton, the course has now reached over 27 million people across 169 countries.

The course itself seeks to focus on aspects of the Christian faith that all denominations hold in common. Although there has been some controversy concerning this claim – particularly regarding its Charismatic leanings – The Alpha Course successfully offers participants a grounding in the standard religious understanding of Christianity.

While the message of The Alpha Course faithfully reflects the broad position of the Contemporary Church, there is a dissident expression of Christianity that runs against this orthodox position. It is an expression found in what have been called “Religionless” incarnations of faith. Incarnations that shake the very foundations upon which the religious edifice of Contemporary Christianity is built.

These “religionless” expressions of Christianity are hard to find as they exist largely under the radar of the institution. Yet they can be found thriving among socially engaged para-institutional parishes, enacted in grass-roots clusters of disobedient priests, promoted in the writings of insurrectionary thinkers and kept alive in the work of militant activists who, from the perspective of the Contemporary Church, look like enemies of the faith.

The Omega Course is designed to introduce people in the church to some religionless readings of Christianity. Readings that carve out an escape route from the type of faith expressed in The Alpha Course.

This course is designed to shock, enlighten and inspire in equal measure. Revealing a subversive spirit of Christianity that overturns distinctions between sacred and secular, transcends the conflict between theism and atheism, and moves, quite literally, towards a church beyond belief.

At its core, The Omega Course aims at unearthing the incendiary, counter-cultural scandal of the gospel by clearing away the rumble of religion.

How the Course works

If you sign up for this four week course you’ll receive a bundle of reflections and access to weekly talks that you can engage with live or download later in video or audio only format. You can sign up for the course before, during or after it begins to gain access to the whole thing.

You can do the course as an individual, but I’d recommend you try and find a small group of people to do it with. This would mean meeting with those people once a week to discuss the material.

For tickets, click here

March 18, 2016

The Omega Course: Adventures in Religionless Christianity

After the success of Atheism for Lent, I’m busy working on an online version of The Omega Course that will be taking place in June. I’ve just launched the tickets and they’re selling fast. Here’s the description,

In 1977, Charles Marnham created The Alpha Course to introduce some basic aspects of the Christian faith to people in his church. From its humble beginnings in Brompton, it has now reached over 27 million people across 169 countries.

The course itself seeks to focus on aspects of Christianity that all denominations hold in common. Although there has been some controversy concerning this claim – particularly regarding its Charismatic leanings – it successfully offers participants a grounding in the standard religious understanding of Christianity.

While the message of The Alpha Course reflects the broad position of the Contemporary Church, there is a dissident expression of Christianity that runs against this orthodox position. An expression found in what has been called “Religionless” incarnations of faith. Incarnations that shake the very foundations upon which the religious edifice of Contemporary Christianity is built.

These “religionless” expressions are hard to find as they exist largely under the radar of the institution. Yet they can be found thriving among socially engaged para-institutional parishes, enacted in grass-roots clusters of disobedient priests, promoted in the writings of insurrectionary thinkers and kept alive in the work of militant activists who, from the perspective of the Contemporary Church, look like enemies of the faith.

The Omega Course is a four week program intended to introduce people to some of these religionless readings of Christianity. Readings that reveal an escape tunnel in the prison of religion.

It’s designed to shock, enlighten and inspire in equal measure. Revealing a subversive spirit of Christianity that overturns distinctions between sacred and secular, transcends the conflict between theism and atheism, and moves, quite literally, towards a church beyond belief.

At its core, The Omega Course aims at unearthing the incendiary, counter-cultural scandal of the gospel by clearing away the rumble of religion.

If you sign up for this four week course you’ll receive a bundle of reflections and access to weekly talks that you can engage with live, or download later in video or audio only format.

To sign up, click here

The Omega Course: Religionless Readings of Christianity

After the success of Atheism for Lent, I’ve started working on an online version of The Omega Course. I’m hoping to get it ready by May. Here is the description I’ve come up with,

In 1977, Charles Marnham created a teaching series called The Alpha Course that was designed to introduce some basic elements of the Christian faith to people in his church. From its humble beginnings in Brompton, the course has now reached over 27 million people across 169 countries.

The course itself seeks to focus on aspects of the Christian faith that all denominations hold in common. Although there has been some controversy concerning this claim – particularly regarding its Charismatic leanings – The Alpha Course successfully offers participants a grounding in the standard religious understanding of Christianity.

While the message of The Alpha Course faithfully reflects the broad position of the Contemporary Church, there is a dissident expression of Christianity that runs against this orthodox position. It is an expression found in what have been called “Religionless” incarnations of faith. Incarnations that shake the very foundations upon which the religious edifice of Contemporary Christianity is built.

These “religionless” expressions of Christianity are hard to find as they exist largely under the radar of the institution. Yet they can be found thriving among socially engaged para-institutional parishes, enacted in grass-roots clusters of disobedient priests, promoted in the writings of insurrectionary thinkers and kept alive in the work of militant activists who, from the perspective of the Contemporary Church, look like enemies of the faith.

The Omega Course is designed to introduce people in the church to some religionless readings of Christianity. Readings that carve out an escape route from the type of faith expressed in The Alpha Course.

This course is designed to shock, enlighten and inspire in equal measure. Revealing a subversive spirit of Christianity that overturns distinctions between sacred and secular, transcends the conflict between theism and atheism, and moves, quite literally, towards a church beyond belief.

At its core, The Omega Course aims at unearthing the incendiary, counter-cultural scandal of the gospel by clearing away the rumble of religion.

If you sign up for this four week course you’ll receive a bundle of reflections and access to weekly talks that you can engage with live, or download later in video or audio only format.

March 16, 2016

Radical Subtraction: The Political Potential of Contemplation

There’s an old joke about a man who visits a lawyer in New York. Upon entering the lawyers office he sits down and says, “How much does your advice cost?” The lawyer responds, “$500 for three questions.” Surprised the man exclaims “Seriously?” “Yes,” says the lawyer, “Now what’s your third question?”

Here the man assumes that he is on the outside of a financial arrangement with the lawyer when he is in fact already enmeshed in it. His very act of considering whether or not to employ the lawyer is happening from the place of already employing the lawyer.

This logic reflects a common way we critically interact with the world. We can think that our critical stance is interrogating a system, when it is really part of what enables the system to continue.

Take the example of Keeping up with the Kardashians. Broadly speaking we might split the audience for the show into two types. Firstly, there are those who watch the show un-ironically. Those who look up to the individuals in the show, seek to emulate what they see, and aspire to a similar lifestyle. Then there are people who watch ironically. Those who laugh at the people in the show and either condemn or ridicule the naïve other who watches without some intellectual detachment.

For those who watch ironically there needs to be an imagined non-ironic other. Either those in the show, or someone watching the show. The non-ironic other is what gives the ironic viewer their pleasure in watching. In reality no such naïve other need exist. Indeed, it is very possible that the naïve other is mostly a fiction that is propagated in order to keep the main audience (the ironic, or morally superior viewer) watching. Those in the show may well be acting as naïve idiots in order to maximize the pleasure of the enlightened viewers. Indeed it is easy to imagine a reality show in which everyone is watching it non-ironically, all smugly imagining that there is some non-ironic other enjoying the show without a knowing distance.

The show itself is not maintained only by naïve viewers, but rather by viewers of any kind. Each individual in the audience is like a battery full of libidinal energy. A battery plugged into the television set, giving libidinal energy to what they watch. This means that any armchair critique is actually enmeshed in the very system that keeps the condemned show running. The show will only disappear if and when enough people unplug themselves and stop feeding it with their libidinal energy.

This example can help us understand some of the political potential of contemplative practices. In the past contemplative practices have been a means by which groups of people have subtracted their libidinal energy from the dominant ideological system. They neither affirm it nor critique it, but create spaces within the world that are not of it. Spaces that don’t play by the rules of the world they inhabit. These spaces are what Hakim Bay called Temporary Autonomous Zones, zones that appear in a location, but that are freed from the ideological constraints of the system that controls that location.

Many of the worst elements of our world continue to exist, not because we believe in them, but because we continue to feed them even when we don’t believe in them.

This phenomenon is powerfully presented in the story of an Irish man called Seamus who, every Sunday, would buy four pints of Guinness. The bar man never thought to ask why until the day Seamus comes in and orders three.

“I don’t mean to pry” says the barman, “but every week for a few years you buy four pints of Guinness, but tonight you’ve only bought three.”

“Well,” explained Seamus,” My father and two brothers all live in different places around the world, and so every week I buy four pints. One for me, and one for them. But last week my father passed away. So now I drink for my brothers and myself.”

“I’m very sorry to hear that,” replied the barman.

A few months later Seamus sits at the bar and orders two drinks.

“I don’t mean to pry,” says the barman, “but has something happened to one of your brothers?”

“Oh no,” replies Seamus, “Doctors orders, I’ve had to stop drinking.”

In this story, Seamus is materially engaged in the very system he thinks he is outside. In a similar way, we might condemn environmental destruction while drinking coffee out of a polystyrene cup, or while making an unnecessary journey to buy an unnecessary product.

In On Belief Žižek has noted how contemplative practices have themselves been incorporated into the running of ideological systems. Today they can act as a type of recharging station. For instance, people might do Zen retreats or yoga practice as a way to relax from the frenetic world of consumerism, only to re-enter that world refreshed. Here contemplative practices act as a type of holiday rather than as a radical materially transformative practice. While this is largely the case today, there are types of materialist contemplative practices that can help free us from giving the system any of our libidinal energy. Some powerful examples of people who have been able to unplug from the system are Marguerite Porete, who didn’t give the church authorities of her day any credence, Mother Teresa, who gave no thought to the caste structure in Calcutta, and Rosa Parks, who ignored the racist structure that tried to dictate the ways she had to inhabit her world. All these figures, in their rejection of the systems they inhabited, engaged in truly subversive acts of political resistance.

March 14, 2016

On the Irish Condition: Psychosis, Lack and Original Sin

Lacan famously used the example of a robbery to describe our emergence into the world. He told his students that our birth as subjects happens at a moment that is analogous to a highway robber putting a gun to our head and saying, “your money or your life.”

In this situation we either refuse to give over our money, thus losing our life, or give over our money, surviving impoverished.

In this forced choice both options are negative.

Here Lacan can be read as offering a type of psychoanalytic reading of Original Sin. For many religious thinkers there has always been a dilemma regarding the idea of sin. In a nutshell, sin is a lack that erupts in the human being (and everything else), yet this lack is the enactment of freedom.

Lacan’s understanding of the birth of the subject offers an interesting, non-theological, way of resolving this. As I have explored earlier, the existentialists show us that being a self involves experiencing ourselves as separate from others. The infant becomes a self insomuch as she experiences a primordial separation, often signified by the mother’s breast.

This separation is experienced as a loss; a loss of something that can never be regained. In psychoanalytic terms, this is the origin of the incest taboo. It is the law that demands we cannot have libidinal union with our mother. Something has to block the way to this union, which is what the Oedipus Complex refers to.

Painful as this separation is, the joke goes that something even worse happens if it doesn’t occur… you become Irish. Hence the argument that Jesus was really of Irish descent – he lived with his mum till he was thirty, and she thought he was God.

There are all manner of problems with the supposed Irish condition. If the separation from the primary care giver doesn’t happen then psychosis results. Psychosis being the condition in which the ego is experienced as fragmented, fluid and under regular threat of dissipation. The person who suffers from psychotic symptoms might have out of body experiences, powerful inner voices, multiple personalities, or an inability to discern where they start and the world stops.

So then, in infancy we either lose something of great value, or lose ourselves.

This loss of the other in separation is however a pure gain. The loss is what gives us to ourselves as conscious beings. While we feel that we lost something, it is the loss that creates the “we” that feels impoverished.

To approach the ancient notion of Original Sin from a Lacanian perspective thus enables us to appreciate the lack as a negative, while simultaneously affirming it.

Our Propaganda Machine: On Broken Kettles and Leaky Buckets

Freud once wrote the enigmatic phrase, “Where id was, there ego shall be.“ One way of interpreting this is by saying – where an explosion of our unconscious emotions occur, there the ego will rush in to provide justifications. In other words, the ego will retroactively justify the outburst. Here the ego takes on the role of propaganda in our being. The department receives word of the explosion and gets to work finding ways of excusing, and even validating, the act.

What Freud describes in these words is something we all encounter all the time. Yet it often goes unnoticed by us, especially when we engage in it ourselves.

While the behaviour cannot be directly identified, it is glimpsed indirectly when someone engages in the “broken kettle” fallacy. This fallacy describes the way an individual employs multiple, contradictory arguments to justify their position. For example,

Person 1 – I hate all these immigrants coming into our country. They’re lazy, devious and take our welfare without contributing to society

Person 2 – But the latest statistics show that immigrants benefit the economy. They work hard at every level of society

Person 1 – Exactly! They come here and steal our jobs

Here the first person has a deeply embedded xenophobia that seeks justification by any means. If one argument is knocked down, she simply constructs another.

A second common fallacy that indirectly reveals the same phenomenon goes by the name “leaky buckets.” This is a common strategy employed by conspiracy theorists and creationists that involves putting forward a whole array of weak arguments in the hope that together they will gain the aura of legitimacy. While it’s obvious that any one of the arguments in isolation doesn’t hold any water, gathering them together creates the illusion that they do.

The most obvious way we see professor ego protect baby id is played out is in the life of children. Most parents are all too familiar with the situation that plays out when they ask their child to do something the child would rather avoid. In asking whether their child has put out the bins we can imagine the child getting irritated and saying, “I was just about to do it!”

What’s interesting in these situations is the way that the child will often succeed in pulling the wool over their own eyes. While they are unlikely to fool the parents, they are able to suspend their own disbelief.

And intelligence doesn’t offer any protection against engaging in this type of act. While a child might justify their hatred of a classmate by saying, “they smell.” A philosopher will justify their unconsciously motivated attack by saying, “they engage in a totalising metanarrative that obliterates alterity.”

Tad DeLay, author of God is Unconscious, has recently written about this phenomenon on his blog in the context of the violence taking place at Trump rallies. After quoting Freud he comments,

While many by November will equivocate and find clever ways to trick themselves into thinking there could be a morally coherent reason to support an implicitly fascist and overtly white supremacist candidate, he is only popular because he is their truth, their id. One could only cheer for this out of a lack of information or a poverty of morals, and the ignorance excuse is quickly fading.

March 10, 2016

It was then that I carried you: A Parable About Death

If you’ve been following my Facebook, Twitter or Instagram you’ll likely know that I’ve collaborated with the amazing designer Clark Orr to make a memento mori. A memento mori is a small object designed to help the owner reflect upon their mortality. It’s part of the ancient tradition of ars moriendi – the art of dying – and is designed to help free the individual from the oppression that comes from the frenetic denial of death.

Traditionally a memento mori defines death as that which marks the end of our life, and has been connected with a philosophy that advocates a type of detachment from the world. However philosophers as powerful as Heidegger, psychoanalysts as great as Lacan and theologians as brilliant as Tillich remind us of the ancient insight that death is not something that simply marks the end of life… but is an essential element of it.

What they mean is that a sense of lack, or non-being, is part of what it means to be – that we are human (non)beings. More than this, they guide us into the insight that the lack which clings to us, if it is faced, is a gift. A gift that helps us muster up the courage to truly affirm existence and shout out an amen to life. In short, the way to rob death of its sting, is to stop fleeing from its influence in our lives, and face it. When we do this, we will discover that death can provide a healing, supportive role in our lives.

With this in mind I wanted to create a memento mori that people could carry with them, an object that would not only remind them that death walks with us, but that this death is a possible friend to embrace rather than a somber specter to flee from.

So we created the Happy Reaper jacket pin.

Over the last couple of days I’ve been toying with the idea of having a parable on the card that carries the pin. Then, this morning, I woke up from a deep sleep with an idea that I’d like to share with you. It might be a little much, I’m not sure. But it’s meant to be both playful and provocative. What do you think?

Deep in his slumber, one night a man had a very real, yet surreal dream. He dreamt that he was walking along the beach with Death. As he looked up at the sky, he saw all the scenes of his life flash by along with two sets of footprints: one set for himself, and another for Death.

After all the scenes had flashed before him, he looked back at those footprints and noticed something quite disturbing: At the most difficult times in his life, he saw only one set of footprints.

This deeply troubled the man, so he turned and said to Death: “You said that if I followed you, then you would always walk with me through thick and thin. In looking back, I see that during the most painful times there is only one set of footprints. Why did you leave me when I needed you the most?”

“I love you and would never leave.”

“It was during those times when you suffered the most that I carried you.”

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers