Peter Rollins's Blog, page 12

January 28, 2016

God: A Being, Non-Being, Hyper-Being, Ground of Being, or Event?

I’ve been spending a lot of time pulling together the relevant material for Atheism for Lent. A de-centering practice I’ve been leading on and off for almost twenty years now. I’m constantly trying to improve on the event and regularly change the material on offer. Now that I’ve completed work for the 2016 on-line version I thought I’d share the basic direction with you.

Week 1 - Problematizing God talk (God as a Being)

To begin with we’ll be spending a week delving into to some thinkers who have problematized our traditional common sense idea of God-talk. What we might also call religious approaches to the question of God. The types of argument people will encounter in the first week reflect what we are likely most familiar with because of the popularity of debates between theists and atheists. This week will help set up the future weeks, where we’ll delve into thinkers (both philosophical and theological) who move beyond these distinctions.

Week 2 - Advent of Modern Atheism 1 (God as Projection)

In the second week we go on to explore two thinkers who influenced the direction of religious critique in the 20th century. By looking at Feuerbach and Marx we witness an important change in the tone and tenor of religious critique. We find here, not only the seeds of a vast and deep critique of religion, but also the possibility of a faith that could be described as religionless.

Week 3 - Advent of Modern Atheism 2 (God as Projection)

When we move into the third week we’ll continue to with two more of the famous “Masters of Suspicion” by looking at Freud and Nietzsche, both of whom offered interpretations of Christianity that was sensitive to the realm of unconscious drives and desires. These thinkers had a profound sensitivity to the hidden realities that can cultivate, motivate and sustain religious belief. Their work marks an important milestone in religious critique because of the way that their approaches pay close attention to the reasons operating beneath, behind and within our conscious commitments.

Week 4 - Towards Theological Atheism (God as Hyper-Being)

By the forth week we move away from more strictly philosophical forms of atheism toward more theological forms. Like philosophical atheism, theological atheism has a rich and complex tradition spanning millenia. While those theologians who fit into this type of thinking begin their genealogy with the biblical text itself, we’ll concentrate on a few figures who were important in the development of its contemporary expression. While New Atheism attempts to distance itself from religion, seeing religion as inextricable linked to the idea of God as a being, here we explore a theological approach that sees this critique as a step on the way to a very different notion of God. God as more-than-being or hyper-being. A perspective that opens up the door to a more theological type of atheism or a/theism.

Week 5 - Theological Atheism (God as Ground of Being)

After this we will delve into the classic 20th century expression of Radical Theology. In the 1960’s Radical Theology achieved a certain fame and popular interest in the West. In many ways this was a point in which the movement matured and gained its distinctive voice, primarily through the work of Thomas Altizer, who is widely taken to be the main figure in the movement. This week’s reflections will help us explore an idea that moves beyond the notion of God as hyper-being, to the conception of God as ground of being. This more existential approach can be seen as a type of bridge between more classical notions of God as a being (the Supreme Being), toward approaches that don’t use the term “being” at all.

Week 6 - Contemporary Theological Atheism (God as Event)

Recently a form of atheist theology could be said to be hitting a second golden age due to the number of academics, activists and popular writers innovating within the tradition. In this final week we’ll introduce some of these figures and touch on some ways of approaching the subject of God that don’t operate around the term “being” at all. In this type of theology, atheism is no longer an enemy of faith, a sparring partner with it, or a friend of it, but rather a necessary part of faith’s very DNA.

While the practice is designed to be personally challenging and transformative, it also aims to be intellectually rewarding. Indeed, by the end of the forty days everyone will understand what is meant when “God” is referred to as a being, a non-being, a hyper-being, the ground of being or as harboring an event or manifesting the Real. If you’d like to sign up, click here.

January 20, 2016

A Challenge for Churches to do Atheism for Lent

What passes for atheism in mainstream culture often comes across as a type of one-dimensional scientistic discourse as problematic as the superficial form of theism it critiques. Not that this is anything new. Karl Marx once remarked that much of what went on under the name of ‘theism’ and ‘atheism’ in his day sounded like little more than people earnestly fighting about whether or not the tooth fairy existed. A debate that may be appropriate for five years olds, but hardly for adults.

However, in contrast to these stagnant, rather childish, debates, there has always been a refreshing stream of atheism that is intellectually rich, existentially deep, artistically daring and politically revolutionary. It is also an atheism that many within religious traditions, and outside them, have seen as intimately related to the life of faith. More religiously orthodox philosophers like Merold Westphal (Suspicion and Faith) and Bruce Benson (Graven Ideologies) have seen the best atheism as a type of purifying fire that lays waste to the infantile and superstitious elements of faith. While other, less orthodox thinkers, have argued that there is an atheism that dives deep into the true depths of faith.

Mystics like Simone Weil, theologians such as Paul Tillich, and philosophers as great as Martin Heidegger, have all argued that there is an atheism that is closer to the truth of faith than theism. A claim that is also argued by eminent figures such as Ernst Bloch, Jacques Derrida, John Caputo and Slavoj Žižek.

It is this very idea that I aim to explore in my Atheism for Lent course. Yet this isn’t some dry academic event. While there will be six lectures from me (that you can listen to live, or download at a later date), the main bulk of the course involves taking time out of your day over the lenten period to reflect on a searing critique of religion. For the first three weeks we will concentrate on philosophical atheism, while for the next three weeks we’ll look specifically at atheism in a theological context.

We already have over 100 individuals signed up, but I’m keen to get some more churches to take the course. I understand that this might seem like a rather dangerous move to make, but actually I think it could be a fun, positive and engaging congregational event. Here’s how I think it could be done,

- Each week one of the excerpts from that weeks Atheism for Lent is read out.

- The speaker then gives a talk that explores what we might glean from that reading. For example, it might be one where Freud writes about how belief can be something we hold because we are afraid of dying. The talk could help people reflect on whether there might be a little truth in that in their own lives, and what a faith might look like which wasn’t based on fear. The readings in the later three weeks will more explicitly relate to this.

- One night a week anyone who wants to do the whole course can meet together and watch the lecture I give, then discuss it.

- Anyone in the congregation who wants to have all the readings, and access to my talks can do so.

This would take place over six weeks, and might really interest and intrigue your congregation. It will also help to move the atheism/theism debate into a much healthier position. In addition to this it might be really good publicity for your community. For example, local newspapers might find this lenten practice rather interesting and want to cover it.

If you’d like to sign up as an individual, or as a community, click here

Building on Fire: Pyrotheology in Practice

One of my early concerns with what goes under the name of Radical Theology was the way that it was a primarily a university discourse. An individual studied various thinkers, gained qualifications designed to prove their knowledge of the subject and ultimately went on to do research, develop the ideas and teach others.

While Radical Theology has a rich theoretical tradition, I’ve always approached it as an existential practice. More specifically, it is a constellation of deconstructive practices that helps an individual or community make peace with doubt, complexity and ambiguity, opens up a sensitivity to the excluded, and increases ones sense of personal responsibility (among other things).

One of the reasons that psychoanalysis interests me is that the training does not take place within the frame of a university discourse. Instead it happens in associations that combine personal analysis, exploration of case studies and group supervision. Ultimately putting all of this into conversation with various analytic theories.

This approach is partly a reflection of the goals of analysis. Psychoanalytic practice isn’t concerned with educating the person on the couch. Neither is the analyst someone who uses a body of knowledge to diagnose the subject. This means that it is quite different from the medical profession. If, for example, someone has a broken bone, a medical doctor will diagnose the condition and give the appropriate care.

In contrast to this universal approach, the psychoanalyst doesn’t have any expert knowledge of a person’s unconscious. It is singular to the individual. A patient will likely put the analyst in the position of someone with expert knowledge (the subject-supposed-to-know), but this assumption (while useful) hides the fact that the analyst is there to help the analysand to decipher and find release from their own suffering. This requires a different set of skills. Among them are the need for the analyst to have themselves undergone analysis so that they might be sensitive to the various defenses and tricks humans can play on themselves to avoid the truth off their condition. This combined with immersion in case studies, regular supervision, and a strong theoretical frame (a metapsychology) allow the analyst to better guide the analysis. Perhaps assisting the patient in becoming freer to hold fulfilling relationships and engage in live-giving work.

For me Pyrotheology is the attempt to take Radical Theology out of a university discourse and explore it as a type of practice. This means that it is more than simply an idea, but also a technology designed to help destroy what I have called the Sacred-object (see The Divine Magician) so as to open up a sense of depth and density in life (the sacred as a depth dimension in objects).

One day I hope there will be associations that offer training in both the theory and technology of Radical Theology, but in the mean time, if you’re interested in this approach, I’m running two things that might appeal to you. The first is a practice called “Atheism for Lent” that you can participate in on-line. The second is a two-day seminar in LA called “Building on Fire” taking place this March.

January 18, 2016

Even the Winners Lose: Some Thoughts on Revolution and Joy

In philosophy there’s a famous idea that goes by the name ‘Master/Slave Dialectic.’ To begin to understand what the terms “Master” and “Slave” mean here, think about a dominant political/cultural/religious matrix. In basic terms the Master class can be said to encompass those on the inside of this matrix and the Slave class represents those who are excluded from it. But while they are excluded from it, they are also a part of it. They are this basically invisible element that represents the unpleasant truth of the system that they are excluded from. They are in the world, but not of it.

Take the example of contemporary America. We might say that the Master class encompasses those of us who particulate in the dominant political, cultural and religious values. This might be expressed in the desire to be successful, to achieve the American Dream etc. In this situation the Slave class represents both those invisible people who are used to sustain this system (Chinese workers making iPhones, Indian children making our clothes etc.), and those who are directly excluded from participation in that system (the homeless, prisoners, those living in trailer parks etc.). In the movie Snowpiercer those who live in the back of the train are simultaneously excluded from the system and needed to keep it running (children being used to keep the engine running).

To understand the Master Class we might say that they are the ones who have symbolic value and who seek symbolic rewards. By “symbolic value” I mean that they have value as citizens under the law who have rights and responsibilities in relation to that law. The term “symbolic rewards” refers to those things we pursue that are valued because of what they represent. For example, the difference between a cheap car and a very expensive car is often minimal (slightly quieter engine, warms up a little faster, has a better sound system etc.). The majority of the extra money is more related to the symbolic value that the car has rather than the material benefits it offers.

In other times and in other places the difference between these two groups has been more pronounced. But in Western society the “Master Class” has expanded to include those who would previously have been in the “Slave Class.” What this means is that more and more people have some kind of minimal symbolic value within the dominant political/cultural/religious matrix and seek the same kind of pleasures that are valued by this matrix. While the reality is that the very poor generally don’t get equal treatment under the law, and will likely never possess the items that society values, they are still inculcated in those systems and oppressed by them.

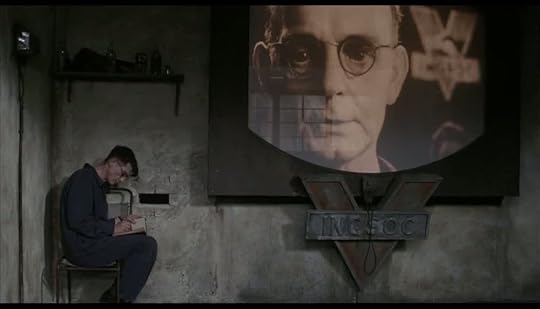

This situation is powerfully expressed in George Orwell’s classic novel 1984. From what I recall there are the party officials, who are at the top of the system, and the workers who are located at the bottom. Yet both the party officials and the workers are ultimately caught up in the same oppressive system. While the party officials have more power and possessions than the workers, they are ultimately bound together in the same death-dealing system that feeds off perpetual war, endless scarcity and continual fear.

In this system the obvious losers are those at the bottom. Yet even the winners lose in Orwell’s dystopia. They too are caught up in an ultimately unsatisfying and oppressive system that they simultaneously sustain. The winners lose while the losers lose doubly.

This is somewhat analogous to our contemporary situation. Consider how those who “win” in our society often suffer from profound boredom and ennui, while those who most directly lose, not only experience the pain of not receiving the rewards of society, but also by having to work difficult jobs while struggling to meet basic needs.

But in 1984 the party officials and the workers only make up part of the story. There is also another class. A class of no class. A group of people in the system, yet who are not of it: the Prols.

This group have carved out a space not monitored, controlled and manipulated by the system. They are needed by it (maintaining a needed black market etc.) but are not integrated into it.

For Marx, this class of no class is the Proletariat and they are the site of a potential revolution. Their position is one that ensures they directly experience the system in its most horrible parts and, as such, are best able to see its unpleasant truth. More than this, they are the most motivated to change things. Unlike those within the Master Class (the Bourgeoisie) who will tend to simply improve the present system rather than overturn it, the Proletariat imagine new worlds and have good reason to try and bring them into being.

One of the interesting features of the prols in 1984 initially sounds to run in the face of what you’d expect. As the most oppressed group that are invisible politically speaking and given no symbolic value, one might expect them to be the unhappiest people of all. Yet they seem to be the only group who are capable of any pleasure.

Lacan can help us understand this in that he saw this class of no class is not only the site of potential revolution, but also the site of a potential pleasure not readily accessible to most of us. The reason for this is because those who are excluded from the system are put in a place where they must attempt to find ways of life outside the symbolic pleasures and rewards of the system (rewards that are ultimately empty). They must find pleasure in creating alternative communities embedded in more immediate pleasures. This is why communities excluded from our consumerist systems often seem to have a wealth of enjoyment that seems strangely absent from those of us caught in the rat race.

The Proletariat is a site of potential pleasure not only because they can find more substantial forms of enjoyment (remember Mother Teresa’s comment that the West was so much poorer than the slums of Calcutta), but also because they can disrupt the present system and draw us back to a more enjoyable form of life.

In this way, the class of no class are the oil of history. They are the ones who hold the promise of real change and deep joy.

One of the ways to understand this is via an understanding of the symptom. A symptom is that phenomenon which is in our body, but not of it. It is that thing we either don’t see, or try to ignore (our outbursts of anger, nervous twitch etc.). Yet the symptom, if we listen to it, speaks a truth. It tells us that something isn’t right in our world. The symptom is thus a protest against something that is bad in our lives (a job we hate, an unfulfilling relationship, a repressed guilt).

The symptom causes us suffering yet, if we listen to it, the symptom can become the site where real transformation and new joy can blossom. If we let it speak it can become the force that causes us to change our lives.

The point then is not to ignore the symptom, but to listen to it. To let it change us.

By doing this the symptom is transformed. Lacan notes this change by cleverly calling it the transformation of a symptom into a sinthome. In French sinthome sounds like “Saint Homme.” Lacan is thus playing on how sinthome sounds just like “Holy Man.” In this way, Lacan is saying that the site of our suffering can become a type of prophet calling us to repentance and transformation. And, just like a prophet, if we open our ears we will find new life, while closing our ears will ultimately lead to destruction.

On the personal, political and cultural level then we must find ways of turning the unholy symptom into a holy prophet.

In terms of pyrotheology the role of the “Church” is not to believe a particular thing, but to be a micro-society of resistance that turns symptoms into sinthomes. This means that it has revolution and joy hard-baked into its very DNA.

This means that it seeks to identify with what is not, so as to disturb, disrupt and dissolve what currently is. In the words of St. Paul, “the lowly things of this world and the despised things–and the things that are not“ will ultimately “nullify the things that are.”

January 16, 2016

Building on Fire, Los Angeles, CA

Come join me in sunny LA for two days bursting with mind-bending talks and subversive dis/courses aimed at sending you off-course and onto a radically new one. I’ll be outlining a vision of faith that celebrates doubt, complexity and ambiguity, resists secular and saintly promises of wholeness, transcends the theist/atheist divide, and warmly embraces the grit and grime of the world. We’ll delve deep into the refreshing waters of Religionless Christianity; discovering together a dynamic vision of Future Church that has liberation and transformation hard-baked into its DNA.

And, as if that wasn’t enough, there’ll be a special guest or two thrown into the mix.

I’d recommend you arrive the day before everything kicks off so that you can drop into Sunday Service, a gathering run by Barry Taylor that practices some of the ideas we’ll be exploring. Afterwards we can all grab a coffee at my favorite coffee shop: the appropriately named Deus ex Machina.

This is an intimiate event with only 30 spaces. Food and accommodation isn’t provided, but there will be lots of free coffee and a few stale donuts. On top of that I’ll recommend some cheap housing options for you.

I’ll be confirming the venue in the next couple of weeks, but the best airport will be LAX and the venue will be easy to get to.

January 14, 2016

December 28, 2015

Some Highlights from 2015

This year has been a good one for me. I’ve made some amazing new friends, moved to a place that I love, and collaborated with some hugely talented people. In addition to this, 2015 signaled some significant developments with regards to the academic reception of my work. Not only did a significant new book get released dealing extensively with my work from a philosophical and theological perspective, but a sociological text from 2014 that delved into my work received the Distinguished Book Award from the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. Perhaps the most important thing that’s happened in this regard however is that a group of incredibly talented young academics and activists have been engaging seriously and critically with my work. If this continues I’m confident that it will develop, deepen and be taken in innovate new directions.

For much of the year I found myself so caught up in other things that I did very little writing. But that has started to change and I’m currently working on a new book, a film script with the working title of “Making Love,” and a long piece for an academic journal that is releasing a volume dedicated to my work.

Of course, this is a highly edited reflection on the last 12 months of my life. A little propaganda piece that doesn’t touch on the inevitable fact that there have been some difficult elements along the way. But it has felt like a time of new beginnings and forward momentum.

I’m cautious enough to avoid predicting what 2016 holds, but I hope to release a couple of books (a more popular work and my fairytales), start shooting the movie and get some collaborative events off the ground. And, of course, there’s my Wake festival, a highlight of previous years. This year is especially significant for me as so many of my close friends are going to be there.

Here are a few of my favorite interviews from the past 12 months,

You Make it Weird podcast with Pete Holmes

The Liturgist podcast with Micheal Gungor and Science Mike

This is Radiocast podcast with Jay Bakker

Freestyle Christianity with Josef Gustafsson

A little video from last years Wake Festival,

A very short overview of my 2015 book The Divine Magician

December 10, 2015

The Tyrants, the Dealers and the Revolutionaries

Last night I watched the 2014 movie Brick Mansions directed by Camille Delamarre. Set in 2018, the movie depicts a dystopian Detroit in which a poverty stricken, crime ridden neighborhood has been walled off from the rest of the city.

*Minor spoilers ahead*

Conditions in Brick Mansions are dire, and the area is controlled by a ruthless drug dealer called Tremaine. An undercover police officer is given the job of entering the neighborhood, recruit a particular convict with knowledge of the area, and disarm a bomb that Tremaine has stolen.

At one point the drug dealer, when challenged about what he’s selling to people, throws his hands up and says, “I didn’t cause this reality. I just help them ease the pain.”

In this way, the drug dealer points out that he is actually the better part of a horrific system. He’s helping people momentarily get some relief from their dire conditions.

There are people who make life difficult for others, and then there are people who are willing to offer a drug to numb the pain. One feeds off the other.

For Karl Marx religion primarily operates in this latter register. Often with good intent, religious leaders offer people a way of bearing their unpleasant reality. Marx understood why people would want to do that, but he was keen to mobilize people in such a way that they would be able to change their unpleasant reality.

One of the interesting things about Brick Mansions is the way that the drug dealer eventually decides to change from offering a painkiller to helping his community fight for a less painful life. Instead of helping the system by dulling people, he committed himself to working for a real change in peoples material reality.

This change is broadly analogous to what I think can happen in actually existing churches. While many churches offer people a type of drug by giving a therapeutic reading of their tradition, it doesn’t take much to slightly change the interpretation so as to draw out the real-world transformative potential of the tradition. Turning the drug dealer (who is a part of the system) into revolutionary (who is a thorn in the side of the system).

Instead of offering a type of hope that causes people to sit back and dream of a different world, the church can speak and sing of a hope that invites us to stand up and work for that different world. This is a hope that causes us to act, much in the same way as the hope that ones child will get a good eduction requires enacting that hope in work, risk, and sacrifice. It is not a hope that causes us to sit back and do nothing, that that inspires us to act.

The popular religious notion of hope presents it as something safe and secure—it is a hope in something that will come to pass and thus doesn’t require our active involvement. It is a hope that encourages passivity, a hope that allows us to accept our current conditions in the belief that something better is galloping over the horizon.

But real hope is risky. It’s a type of hope without hope, a hope against hope. It’s a hope that makes demands on us, that motivates us to put our weight behind it. It is a hope that tells us we can make the world a better place, that we can transform society and enact justice.

In life we can be the ones who contribute to the ills of society, the ones who offer painkillers, the ones who take the painkillers, or the ones who work for real change.

December 4, 2015

Love Under the Shadow of Death: The Making of a Movie

A few years ago I wrote a Play called ‘The Gallows’ inspired by an obscure thought experiment in which Immanuel Kant imagined a young man deeply obsessed with a woman. The woman was completely inaccessible, however an opportunity eventually arises where he can spend one night with her.

But there’s a catch.

If he sleeps with her he’ll be hung the next day on a gallows.

For Kant, the solution to this dilemma is simple. The man should calm down, resist the temptation and get on with his life.

Almost 200 years later the psychoanalyst Lacan made a reference to this thought experiment in one of his seminars and noted that the dilemma is actually more complicated than it first appears. For Lacan, the gallows is not simply a deterrent. It can also act as a fuel that fans the flames of the man’s desire. The very threat of death making the temptation all the more difficult to resist.

The Play itself revolved around the story of a man and woman reuniting after ending a passionate affair some years before. They meet late one night in a luxury hotel in Belfast and rediscover the sexual chemistry that had once drawn them inexorably together.

There is however a problem. The husband knows all about the reunion and has made it clear that, should the man sleep with his wife, he’ll never leave the hotel alive.

The story delves into what happens that night and explores the themes of sex, obsession, death and desire. More than this, it reflects the central themes of my wider theological project.

While working on the script it became clear that it was better suited to the big screen, so earlier this year I began working with an amazing screenwriter to adapt it into a movie. One that fits into that well-known genre of theological erotic thrillers.

Things are moving forward, so I’m keen to start giving you occasional updates as we finalize the script, secure actors, and nail down locations. I’m also confident that there will be an opportunity to get involved as we approach filming.

What Do I Love When I Love My God

I was recently asked whether my pyrotheological project is one that ultimately rejects peoples subjective experience of spiritual reality. In order to approach an answer I want to briefly reflect on one of the things that a psychoanalyst looks out for when attempting to diagnose whether or not someone is suffering from a psychotic break.

It’s popular to think that one of the ways to work this out is to discover if the individual is having visions of some kind. It is well known that psychotic individuals often have incredibly lucid encounters with ghosts, gods or aliens. The problem however is twofold. Firstly, such visions are not at all constrained to psychotic individuals. Various people have these types of experiences who are more obviously neurotic. Secondly, it is not the analysts job to make such judgements about the existence of supernatural or extraterrestrial activity.

In A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis, Bruce Fink notes that the analyst must be sensitive to the way that the vision is held by the individual rather than simply the fact of the vision. For example, two people might have the same experience of clearly hearing a voice of their dead mother. While one holds on to this as indubitable proof that their mother returned from the grave to give a message, the other says something like, “It could have been a message from my mother, or perhaps it was my mind playing tricks, or a type of wish-fulfillment.”

What the analyst looks for is the level of certainty in the interpretation by the individual. The psychotic is likely to attempt to write books, make documentaries or even found communities on their visions. Believing without a shadow of a doubt in their legitimacy. They are, initially at least, unable to critically assess their interpretation. Those who raise questions about it are viewed with suspicion. They might be seen as hard-nosed skeptics, or as someone with a vested interest in denying the truth, but they are generally felt to be a threat.

In contrast, the neurotic is one who holds their vision tentatively. They may believe that they were visited by their mother, but they are also open to other explanations. Here, the one who raises questions is generally welcomed because they are reflecting the neurotics own internal process. In light of someone pointing out that the vision might just have been a hallucination resulting from extreme desire, the neurotic might reply, “yeah, that could be the case. I guess I do really wish she would speak to me sometimes.”

In a similar way, we can see how two different religious groups could feel grasped by a similar vision, yet while one has an unyielding, totalizing interpretation of it, the other is open to questions, doubts and re-interpretations. In the former, anyone who begins to question the given interpretation will be viewed with suspicion and held at a distance. While in the later, the one who asks questions will not be seen as a threat, and may even be treated as a gift and blessing to the community.

The point of pyrotheology is not to question the metaphysical reality of someones vision, but rather to attempt to introduce a critical distance to the vision (in psychotic structures) or encourage questioning in more neurotic structures. By encouraging re-interpretations and doubts the community is able to affirm what they feel caught up in while avoiding the temptation to nail it down into some absolute form. This is something that Derrida articulates beautifully via deconstruction. An approach that takes seriously ones embedded tradition, while always remaining sensitive to the not yet realized potential of the tradition and faithful to the task of forever reforming and rethinking it. Something that John Caputo draws out in his beautiful book On Religion where he writes about St. Augustine’s question, ‘What do I love when I love my God.’

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers