Peter Rollins's Blog, page 7

May 13, 2016

Building on Fire, Grand Rapids, MI

Join me for an all-day event designed to reveal the personal and political potential of what Religionless Christianity. The sessions are crafted to help enrich your experience of life and equip you to better impact your world. If that doesn’t happen, you’ll still met some cool people and hopefully have a good time.

During the event we’ll explore a subversive understanding of faith to discover a radical Christianity that blurs the distinctions between theist and atheist, offers personal and political liberation, and helps us experience new depth in our lives.

If you book a place you’ll also get free access to an evening of Pints and Parables worth $20, where I’ll be sharing some of my favourite stories over drinks. Then, if you’re still around, you can always pop along to Mars Hill the next day where I’ll be giving a sermon at 10am.

Everyone who comes will get one of my limited edition JTC style “Rapture” tracts.

May 12, 2016

Wake 2017, Belfast, UK

This will be the fifth year of my boutique Belfast festival. Taking place in a variety of venues dotted throughout the cultural heart of the city, this festival brings together 50 people from all over the world, offering up a rich blend of ideas, music, film, art, alcohol and conversation. Set in Peter’s hometown this is an amazing opportunity to learn about one of the most controversial theological projects in one of Europe’s most famous and vibrant cities.

Everything officially kicks off on Tuesday 25th, but there will be pre-event drinks on the 24th and a there’s a big free street festival the following weekend.

Price excludes food and accommodation (but we’ll recommend a variety of options for both – from the very affordable, to the very luxurious).

Here’s a video from one of the previous events,

Click here to see pictures from last year

May 11, 2016

When Silence Encircles Silence: Super-injunctions and Religion

In English law an injunction functions as a prohibition that prevents journalists from talking about a certain issue. A super-injunction is a prohibition that prevents journalists from talking about the fact that there is a prohibition. Not only can something not be talked about, but you cannot talk about the fact that there is something you can’t talk about.

Within various ideological systems we see forms of super-injunction take place. We can imagine, for instance, a religious community that doesn’t admit to its questions, doubts and disbelief. If someone brings up underlying doubts they can themselves ostracised by the wider community. However the prohibition against raising doubts is itself hidden behind a second-level prohibition that stops anyone naming this crime against orthodoxy. If someone where to stand up and warn people that they were not allowed to question the doctrine of the church, express doubts, or think freely, that individual would likely find themselves just as ostracised as the one who openly raised questions. The first breaks an injunction while the second breaks a super-injunction.

For the prohibition to remain effective it must operate in secret.

Not a secret that hidden from everyone, rather a secret that almost everyone knows but have conspired to keep hidden.

A perfect expression of this can be seen in a political act that Slavoj Žižek and some others engaged in as students in Yugoslavia. At the time the Communist Party always won the elections because they were fixed. At first the students considered exposing the truth that everything was rigged. But they realized that almost everyone already knew this. It was a secret knowledge that people knew but never talked about. So instead they pretended to engage in an act of pure naivety and treat the elections as if they were free.

With this in mind they used their student journal to publish a special edition on the eve of the elections. In the journal they wrote about how everything was to play for in the political arena, how no one could possibly predict the results, and claiming that it looked as if the Communist Party might actually win. This act made a mockery of the political process by overly identifying with it. By believing the official story they undermined for the simple reason that the satire would make people laugh and encourage them to actually name the secret knowledge that remained unspoken.

When the students were brought before the Central Committee, they acted completely ignorant and asked, “what did we do wrong?” After all, the Central Committee held that this was a free election, and the students were agreeing with that. The problem for the officer interrogating them was that he was unable to actually spell out what they had done wrong. Not only was democracy prohibited, but no-one was able to actually speak about how democracy was prohibited – including those in the Central Committee.

Often a political act involves naming the hidden prohibitions that would embarrass and undermine the ideological system in question. For example, in some religious communities there is both a silence around issues concerning sex and sexuality and a silence encircling this silence. Not only can you not speak about sex and sexuality outside what is considered normal, you can’t even talk about how you can’t talk about it. The first step thus involves finding creative ways to expose the super-injunction for all to see.

Secret Philosophical Society, LA, CA

I’ll be joining Barry Taylor for the first ever Secret Philosophical Society event. The Secret Philosophical Society presents an evening of educational entertainment hosted by Barry Taylor and devoted to superstition and mystery, Friday the 13th of May.

The fear of the number 13 has a scientific name – triskadekaphobia. According to the Stress Management and Phobia Institute, somewhere between 17 and 20 million people are so affected by a fear of Friday 13th, that they break normal routines, avoid flying, and even getting out of bed. Why are so many people afraid of a number? What’s the deal with black cats, and how can our fears set us free?

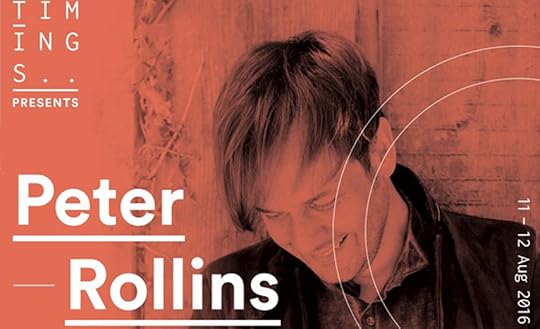

Timings 2 Day Conference, Lincoln, UK

I’m very excited to be working alongside Rob Bell and Roger Bretherton in this two day conference in Lincoln. This intimate event is one of only a couple of UK dates in Rob Bell’s calendar, so tickets are selling fast. To book click the link.

May 8, 2016

On C.S. Lewis, Freud and the Reality of Monsters

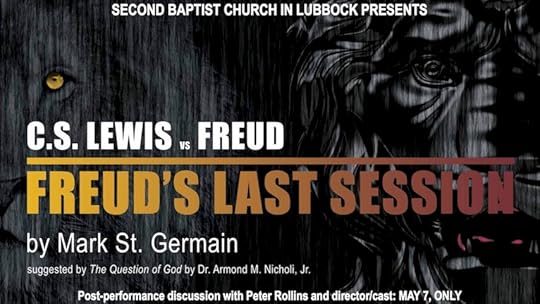

Back in 2011 I saw the off-broadway show Freud’s Last Session. A play based on a fictional conversation between an elderly Sigmund Freud, fast approaching death, and a young C.S. Lewis shortly after his conversion.

Both figures have a certain importance for me. C.S. Lewis was a Belfast boy who grew up 5 minutes walk from my home. I attended his family church as a youth, and spent a lot of time close to Little Lea – his childhood home – as a friend lived next door. I have a respect for Lewis’ writing style, his storytelling, sharp mind and skills as public intellectual. Freud, on the other hand, has been an important intellectual influence on my life and work. I studied him closely as an undergrad, and psychoanalytic theory plays an important role in my theological project.

On the surface Freud’s Last Session is a story about two worldviews clashing. Lewis, an apologist for “mere Christianity” and Freud defending a materialist worldview. Knowing the book that the play was based on, I was pretty skeptical about the whole idea. The original book was written firmly from the C.S. Lewis corner. Something that was hinted at in the very idea of putting these two figures side by side in the first place – as if they were intellectual equals.

This tainted my initial viewing of Mark St.Germain’s play. Indeed I came away from it feeling that Freud was mostly there to act as a foil for Lewis’ apologetic arguments: that there is a Natural Law, that otherworldly desire has a real object, that Christianity is the fulfillment of myth in reality and that Jesus is Lord rather than a liar or lunatic. Indeed, at one point Freud is seen as falling into Lewis’ very crude “Liar, Lunatic or Lord” logic when Lewis manages to maneuver Freud into first accepting and then rejecting the first two positions so as to imply that Jesus was probably who the New Testament claims him to be.

But a few months ago, while sitting in The Lamppost Cafe in Belfast – a C.S. Lewis inspired coffee shop – I received an invitation to see the play again in Lubbock, TX and take part in a panel discussion. I’d been reading everything Lewis had written on theology for an event I was planning later in the year, and felt that a critical engagement with the play would be fun. A few emails later and I was confirmed.

So last night I broke up my trip from Ireland to LA with a stop in Lubbock to watch the play for a second time. While I was expecting to have a similar experience as before, I actually came away with a very different assessment of the play.

The play itself was beautifully directed by Charles Pepiton and powerfully performed by Marti Runnels (Freud) and Cory Norman (Lewis). Runnels’ Freud was anything but a one-dimensional character being outsmarted by the young Lewis. Instead Freud came across as smart, witty and utterly brilliant. The young Lewis was also masterfully played, portrayed as an initially arrogant and uptight young man there to fell a giant: to castigate the great Freud and defend Christianity.

Yet both men are plagued by underlying struggles that constantly interrupt their discussions and reveal their humanity. Freud is dying of cancer and suffers great pain because of his ill-fitting prosthetic jaw. Whereas Lewis is struggling with post traumatic stress after his time in World War I. Both men also reveal that they had a poor relationship with their respective fathers.

But more than all this, their meeting is taking place at the threshold of World War II. As a result, their discussion is often interrupted by updates from the radio about Hitler and the invasion of Poland.

This backdrop of personal and political turmoil hints at the truly subversive and significant nature of this play that I must confess to having mostly missed on my first viewing. While it might look as if the apologist Lewis is leading the discussion, the actual structure of the play is fundamentally Freudian in nature. The play itself is constructed as a type of living embodiment of conscious/unconscious interactions.

What happens at the level of consciousness – the abstract arguments – is constantly undermined by the presence of the unsaid: repressed fears and desires.

These unconscious elements can’t be held at bay by either man and thus constantly interrupt what is taking place on the surface. Each time the play threatens to become some type of abstract philosophical diatribe, something disrupts the proceedings: air raid sirens blast out, BBC announcements tell us of impending doom, a phone call reveals undisclosed desires, a fit of cancer induced coughing erupts etc.

The philosophical discussions cannot silence these eruptions of the Real. Indeed, the eruptions keep reminding us that the repressed must always return. That what we refuse to speak will find a way to speak itself.

As Lewis and Freud are confronted by their demons and decentered by their fears and desires, the cold, rational arguments fall away and they are left feeling empathy for each others struggles. No-one wins any arguments, and it wouldn’t make any difference if they did. For no rational system is able to silence the repressed, or magically get rid of the struggles that each man, and the world itself, faces.

At the close of the play, Freud tells a joke about a dying insurance man who invites the village priest to visit his death bed. The insurance man is an avid atheist, so his family are surprised by the request. But the message is passed along and priest dutifully comes to the mans bedside. The two men debate throughout the night. The next day the priest leaves. The insurance man has died an atheist, but the priest is fully insured.

In the play, Freud is the dying insurance man and Lewis the Priest. Yet neither walk away convincing the other. As Lewis says, in response to the joke, “I wish there were such a thing… insurance.”

But there is none for either of these men. No way of protecting themselves against their personal traumas or the traumas of war. Instead they are left with their demons, and no way of silencing them. Lewis leaves Freud’s office to walk back to his train, leaving the two men in the same position as they were at the beginning of the play – alone and haunted.

On second viewing I was confronted, not with a crude pseudo-philosophical diatribe about God, but with a subtle and moving existential play about life and the limitations of philosophy when confronted with the shadows of our personal and political reality.

April 14, 2016

You can be Like God: Some Thoughts on the Oedipal Dilemma of Adam and Eve

This post suffers from the duel sins of saying too much and too little. Too much in that it requires a certain grounding in psychoanalytic thinking, and too little because it offers nothing but a brief sketch of the way I approach the biblical tradition. For a more in depth version, I recommend The Divine Magician.

While the Oedipus Complex was central to Freud’s development of psychoanalysis, and remains central to many who work within that field, it isn’t an easy concept to grasp. The original story of Oedipus tells of a son who unknowingly fulfills a prophecy when he murders his father and marries his mother. Acts that bring disaster.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, the marriage of mother and son can be seen to represent our desire to possess some primordial object that would fill the lack that arises as a result of our development as a subject. The father represents that which gets in the way of this fantasied union. While the murder of the father represents our deep desire to be rid of the obstacle in order to have that which we feel will make us complete.

In more theological language, the mother represents a sacred object that will bring wholeness and the father represents the Law that prohibits it. The Law is experienced as that which separates us from what we desire, while actually increasing our desire for what is prohibited. Thus the prohibition (Law), as Paul understood, is directly connected with the Lack (Sin).

From this perspective, the story of Adam and Eve is a type of Jewish Oedipal story. Adam and Eve are separated from an object that will make them ‘like God’. In other words, an object that will make them whole, for God is not marked by lack. This sacred object is prohibited by the No of the father, the prohibition. Adam and Eve refuse to identify with the prohibition (the Law) and disaster results.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, the resolution of the Oedipal dilemma results from first identifying with the Law – renouncing ones pursuit of the lost object – and then later realizing that the Law hides nothing. That there is no lost object on the other side of the law that can take away the lack.

These two moves (identifying with the law and realizing that the law hides nothing) have a theological counterpart. The first lies in the role of the covenants. A covenant is a type of contract that all parties are obliged to obey. A contract is not designed to bring you closer to the other, but to help separate you from them. More precisely, from their desire. One enters into a contract to be protected from the ever changing desire of the other, and visa versa. A divorced couple, for instance, contractually agree to certain visiting times, alimony etc. in order to avoid any problems that arise from people changing their mind. If the contract isn’t adhered to, all manner of problems arise. The biblical covenants can thus be understood to create distance from people are their sacred object.

In the aftermath of the Oedipal disaster reflected in the story of Adam and Eve, we have the epoch of covenants, which reflects the first stage of identifying with the law.

The second move is the discovery that, behind the Law, there is no sacred object to make us whole. That the promise of being “like God” is a lie. This means that the law is an arbitrary imposition that must be transcended by a new order (love). This second move happens in both Jewish thinking (something that we can see in Žižek’s reading of Job, for example), and in the founding event of Christianity.

Within the latter this is seen explicitly in the Crucifixion when the prohibition is removed and we see that nothing lies behind it. This is symbolized in the tearing of the temple curtain, which reveals that the Holy of Holies is just an empty room. What we thought lay between ourselves and the sacred object actually hid the reality that there is no sacred object.

After this, a type of life is opened up in which we might move beyond the Law and its transgression. A type of life in which the sacred is no longer felt to be some lost object (the lie of being “like God”), but rather as a type of density found in real objects. Theologically this is expressed in the meaning of Resurrection and the epoch of the Holy Ghost.

So then, in the same way as the Oedipus Complex is a fundamental concept in Freudian Psychoanalysis, so the Eden Complex is a fundamental concept in Pyrotheology.

April 10, 2016

Thrive Conference, Granite Bay, CA

I’ll be giving a couple of sessions at this conference under the title, “How to be Saved: Recieving Good News from the Margins”

Within the Church we often hear the idea that we can be good news to those who are oppressed, marginalized and silenced by society. But what if those on the fringes actually have good news for us? What if they help to expose the reality of a sickness deep in the heart of the structures we promote and protect? In these sessions Peter will ask whether those on the fringes of society might actually be our prophets. Truth tellers herelding a good news for us by bringing to light hidden evils we are loath to face. In short, we will explore whether our engagement with those on the margins might, if we cultivate ears to hear, lead to our salvation.

March 28, 2016

Wake: The Line-up

This year I finally christened my Belfast based underground festival of 40. The name I gave it was Wake.

A wake is a gathering that takes place between a death and a funeral. It traditionally takes place in the home of the one who has passed and helps those gathered to come to terms with the loss. A wake is a social event that allows a community to confront what has happened. Yet despite the seemingly depressing nature of a wake, they are a place of joy and connection, and well as remembrance and mourning.

Wake is a festival that marks the death of various cultural, political and religious gods that have impacted our lives. It is a festival that employs talks, music, mentalism, movies and art to help us come to terms with these deaths and say our farewells to the lifeless bodies that impacted us.

This year we’ve an amazing line up of musicians, thinkers, artists and activists to help us take this journey. Our speakers include the academics Katharine Sarah Moody and Barry Taylor, the authors Jay Bakker and Kester Brewin, and some local talent like BBC radio and television presenter William Crawley. In addition to this we’ll be joined by the hardcore grassroots hip hop artist Jun Tzu and the dark, sultry voice of Molly Sterling, who represented Ireland in the 2015 Eurovision song contest. We’ll also be doing a tour of C.S. Lewis’ homeland and exploring his work on grief. Add to that some mind bending mentalism from one of Ireland’s best young magicians – Joel MaWhinney – and more than a few pub crawls and you’ve got all the ingredients for an amazing four day wake.

There are only two tickets let. So, if you’d like to come, grab them now!

Jun Tzu

Molly Sterling

The Foolishness of the Non-Fool: Fundamentalism, New Atheism and the Enlightened Idiot

Part of our development into subjects involves our inscription into language. Whatever country we are born in, we must learn how to navigate a symbolic structure (English, French, Chinese etc.).

This inscription into language is not without its difficulties, and it never goes without a hitch. But very gradually language becomes transparent to us and we emerge as speaking subjects.

In becoming citizens of the symbolic order we require what Lacan called “the-name-of-the-father.” This phrase names an external authority that helps the infant make a basic connection between sounds (signifier) and meaning (signified). The-name-of-the-father basically enables the child to move from a suffocating literalistic world into a universe overwritten by symbols.

In short, the young child, in order to become a creature of language, has to be fooled into embracing perspectives and interpretations. In the words of Anaïs Nin, we no longer encounter the world as it is, but as “we are.”

Lacan was a master at forging neologisms and creating clever double entendres. Like the poet Mallarme, Lacan was constantly playing with the plasticity of language in ingenious ways that defy translation. One of these can be found in the phrase “the-name-of-the-father” which in French sounds identical to the phrase, “the non-duped err.”

When Lacan informed his students that the non-duped err, he was letting them know that if the-name-of-the-father fails then we do not properly enter into the symbolic realm, and that this causes us to make a fundamental mistake.

So what might this mean? To begin with watch this short sketch my Mitchell and Webb that takes place at a wedding,

What we witness here is the Best Man being utterly unable to enter into the fiction of the wedding. He takes what the groom says in a literal way and thus makes a very basic error. Of course he rightly considers himself to be the only truly enlightened one in the room, surrounded by fools who have been duped into thinking that they are witnessing the marriage of the gods. He feels the superiority of seeing the truth while the others fall for a ridiculous fiction. Yet it is precisely in his correctness that he errs. For, as Lacan would show, the truth is in the fiction.

The name that is given to the condition that erupts from a catastrophic failure of the-name-of-the-father is psychosis. The Psychotic is one who is not fully integrated into the symbolic realm. To have a psychotic structure is neither good nor bad in itself. It simply reflects certain struggles that the individual will have in their life that differ somewhat from the perverse subject or the neurotic one.

The psychotic will have a rather difficult relation to the symbolic system they inhabit. They will tend to see things literally, be confused by the invisible constellation of social cues that define behaviour, and get frustrated when people say one thing when they mean another. Parties will often be confusing to someone who is psychotic because what is said is rarely what is meant. They can’t easily read the social cues that come so naturally to everyone else and the ambiguity of flirting is almost impossible to interpret.

The psychotic is “non-duped.”

They see through the games people play, and for this very reason they err. Think of the pupil who doesn’t see her teacher as a symbolic authority. She only see a normal person where everyone else in the class sees a father or mother figure. She doesn’t treat the teacher with the same respect and thus finds herself getting into trouble, being suspended, or even kicked out of school. The school system is just a human construct to her, and thus she finds it hard to give it any symbolic authority. While she has a clearer insight than the others in her class, it causes her all kinds of problems. As she grows she finds the same problems repeated when she encounters the police or a judge. She doesn’t pay fines, finds it difficult to keep on top of bills, and isn’t scared of banks who chase her for an unpaid debt. The system is human, all too human. But for this very reason the psychotic can find herself homeless, in prison, or alone. The other path for the psychotic is to learn how to adapt and pretend. This actually enables her to do very well in society. The clever psychotic can play the system, and do things that a neurotic cannot. For instance, a neurotic business owner might so fear the bank that he tries to pay back an impossible loan, while a psychotic will have no problem filing for bankruptcy and starting again. The symbolic “failure” of being bankrupt means nothing to her.

In New Atheism we witness something similar going on with regards to peoples religion. The New Atheist prides himself on not being duped by silly religious fantasies. But for this very reason he misunderstands what is happening in religion. He is like a person who hears a grandparent say, “my grandchild is the most beautiful kid in the world,” and laughingly responds, “of course she isn’t, that is an utterly ridiculous thing to say.” The individual is right, and for this very reason they make a fundamental error. The grandparent has let herself be duped, but this means that she is successfully inscribed into the symbolic world and is able to navigate it.

The Enlightened New Atheist sits back and laughs at those unenlightened naïve believers who say things like, “my religion is the most beautiful religion in the world.” Yet he does not realise that it is precisely in them not being a fool that they become utterly foolish.

Of course fundamentalism is also a type of structural psychosis in which the individual claims to inhabit a non-symbolic space. They are like the grandparent who literally means her grandchild is the most beautiful kid in the world.

The response is not for the besotted grandparent to say, “my child is average looking,” – the equivalent of a non-committal agnosticism – but to fully affirm the claim that her grandchild is the most beautiful child in the world without needing some ground for the claim.

To those inscribed into the symbolic universe the youtube debates between fundamentalists and new atheists look like the equivalent of one person claiming her grandchild is literally the most beautiful kid in the world, and another who argues that she most definitely isn’t.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers