On C.S. Lewis, Freud and the Reality of Monsters

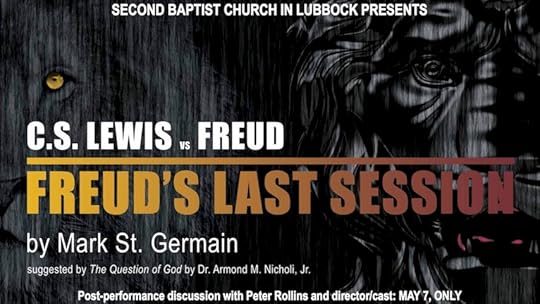

Back in 2011 I saw the off-broadway show Freud’s Last Session. A play based on a fictional conversation between an elderly Sigmund Freud, fast approaching death, and a young C.S. Lewis shortly after his conversion.

Both figures have a certain importance for me. C.S. Lewis was a Belfast boy who grew up 5 minutes walk from my home. I attended his family church as a youth, and spent a lot of time close to Little Lea – his childhood home – as a friend lived next door. I have a respect for Lewis’ writing style, his storytelling, sharp mind and skills as public intellectual. Freud, on the other hand, has been an important intellectual influence on my life and work. I studied him closely as an undergrad, and psychoanalytic theory plays an important role in my theological project.

On the surface Freud’s Last Session is a story about two worldviews clashing. Lewis, an apologist for “mere Christianity” and Freud defending a materialist worldview. Knowing the book that the play was based on, I was pretty skeptical about the whole idea. The original book was written firmly from the C.S. Lewis corner. Something that was hinted at in the very idea of putting these two figures side by side in the first place – as if they were intellectual equals.

This tainted my initial viewing of Mark St.Germain’s play. Indeed I came away from it feeling that Freud was mostly there to act as a foil for Lewis’ apologetic arguments: that there is a Natural Law, that otherworldly desire has a real object, that Christianity is the fulfillment of myth in reality and that Jesus is Lord rather than a liar or lunatic. Indeed, at one point Freud is seen as falling into Lewis’ very crude “Liar, Lunatic or Lord” logic when Lewis manages to maneuver Freud into first accepting and then rejecting the first two positions so as to imply that Jesus was probably who the New Testament claims him to be.

But a few months ago, while sitting in The Lamppost Cafe in Belfast – a C.S. Lewis inspired coffee shop – I received an invitation to see the play again in Lubbock, TX and take part in a panel discussion. I’d been reading everything Lewis had written on theology for an event I was planning later in the year, and felt that a critical engagement with the play would be fun. A few emails later and I was confirmed.

So last night I broke up my trip from Ireland to LA with a stop in Lubbock to watch the play for a second time. While I was expecting to have a similar experience as before, I actually came away with a very different assessment of the play.

The play itself was beautifully directed by Charles Pepiton and powerfully performed by Marti Runnels (Freud) and Cory Norman (Lewis). Runnels’ Freud was anything but a one-dimensional character being outsmarted by the young Lewis. Instead Freud came across as smart, witty and utterly brilliant. The young Lewis was also masterfully played, portrayed as an initially arrogant and uptight young man there to fell a giant: to castigate the great Freud and defend Christianity.

Yet both men are plagued by underlying struggles that constantly interrupt their discussions and reveal their humanity. Freud is dying of cancer and suffers great pain because of his ill-fitting prosthetic jaw. Whereas Lewis is struggling with post traumatic stress after his time in World War I. Both men also reveal that they had a poor relationship with their respective fathers.

But more than all this, their meeting is taking place at the threshold of World War II. As a result, their discussion is often interrupted by updates from the radio about Hitler and the invasion of Poland.

This backdrop of personal and political turmoil hints at the truly subversive and significant nature of this play that I must confess to having mostly missed on my first viewing. While it might look as if the apologist Lewis is leading the discussion, the actual structure of the play is fundamentally Freudian in nature. The play itself is constructed as a type of living embodiment of conscious/unconscious interactions.

What happens at the level of consciousness – the abstract arguments – is constantly undermined by the presence of the unsaid: repressed fears and desires.

These unconscious elements can’t be held at bay by either man and thus constantly interrupt what is taking place on the surface. Each time the play threatens to become some type of abstract philosophical diatribe, something disrupts the proceedings: air raid sirens blast out, BBC announcements tell us of impending doom, a phone call reveals undisclosed desires, a fit of cancer induced coughing erupts etc.

The philosophical discussions cannot silence these eruptions of the Real. Indeed, the eruptions keep reminding us that the repressed must always return. That what we refuse to speak will find a way to speak itself.

As Lewis and Freud are confronted by their demons and decentered by their fears and desires, the cold, rational arguments fall away and they are left feeling empathy for each others struggles. No-one wins any arguments, and it wouldn’t make any difference if they did. For no rational system is able to silence the repressed, or magically get rid of the struggles that each man, and the world itself, faces.

At the close of the play, Freud tells a joke about a dying insurance man who invites the village priest to visit his death bed. The insurance man is an avid atheist, so his family are surprised by the request. But the message is passed along and priest dutifully comes to the mans bedside. The two men debate throughout the night. The next day the priest leaves. The insurance man has died an atheist, but the priest is fully insured.

In the play, Freud is the dying insurance man and Lewis the Priest. Yet neither walk away convincing the other. As Lewis says, in response to the joke, “I wish there were such a thing… insurance.”

But there is none for either of these men. No way of protecting themselves against their personal traumas or the traumas of war. Instead they are left with their demons, and no way of silencing them. Lewis leaves Freud’s office to walk back to his train, leaving the two men in the same position as they were at the beginning of the play – alone and haunted.

On second viewing I was confronted, not with a crude pseudo-philosophical diatribe about God, but with a subtle and moving existential play about life and the limitations of philosophy when confronted with the shadows of our personal and political reality.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers