Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 122

February 20, 2013

Morgan Llywelyn's After Rome, her newest novel of the passionate Celts

Through her carefully imagined novels, Morgan Llywelyn has traversed nearly three millennia of Celtic history, with The Horse Goddess's ancient pagan mysticism at one end of the spectrum and 1999, the last volume in her five-book Irish Century series, at the other.

Through her carefully imagined novels, Morgan Llywelyn has traversed nearly three millennia of Celtic history, with The Horse Goddess's ancient pagan mysticism at one end of the spectrum and 1999, the last volume in her five-book Irish Century series, at the other.The title of her newest, After Rome, makes it easy to place on a timeline. The Romans have fled early 5th-century Britain to defend their home city from barbarian attacks. The educated Britons they had trained as civil servants are left to pick up the pieces.

Governmental foundations have collapsed, and order has broken down. Roads have deteriorated, physicians are nonexistent, and nobody knows how to work many of the engineering marvels so prevalent in Roman daily life. Britain has become a chaotic, desolate place full of abandoned ruins and lingering memories, not all of which are pleasant.

This is a history-driven novel, meaning that Llywelyn has developed characters to fill specific roles and dramatize two opposing paths taken by the native Romano-British in re-civilizing their homeland. Mature and responsible Cadogan, living in self-imposed isolation in the woods, becomes the reluctant leader of a group of survivors after Saxons sack and burn his home city of Viroconium.

His cousin Dinas, restless and ambitious, seizes an opportunity for leadership by gathering together a cadre of would-be warriors to conquer the land — wanting to make himself their king in the process. Antagonism runs blood-deep between their branches of the family after a love affair turned deadly.

The secondary characters in After Rome are a quirky and oddball bunch: the scrawny and feisty Quartilla, who claims to be a centurion's daughter and who Cadogan finds alternately annoying and helpful; his estranged father, old Vintrex, Viroconium's chief magistrate; and the motley members of Dinas's growing band, which include one injured, saintly man who isn't mentally all there and another with an uncommon rapport with animals.

As the men and their followers struggle to regroup and establish bases of power, the Saxons are equally eager to drive them apart and crush them. One particularly vivid scene sees Cadogan and his fellow refugees sitting nervously in the darkness of Viroconium's public bathhouse while marauding tribes slaughter everyone outside. In the parallel story involving his wanderer of a cousin, the remote peaks of Eryri, in what will one day be Wales, appear in stark, haunting detail:

By the close of day the land was engulfed in purple shadows. One last flare of gold and crimson from the west, then darkness. Dinas drew rein. "Night in these mountains can be as black as the inside of a cow," he warned his companions ... He led the way beneath an overhanging shelf of rock, then onto a narrow ridge that climbed toward the sky. A million stars blazed over them.

This is sharp and evocative writing, but on other occasions, Llywelyn drifts away from her story for a pages-long history lesson. While these are informative, it feels startling to wake up from an involving tale to find oneself inside an encyclopedia.

After Rome doesn't have the same consistently engaged style as her earlier works. However, readers drawn to the post-Roman, pre-Arthurian period will want to pick it up for its energetic yet thoughtful recreation of this transitional stage in Britain's history, and of a proud people who formed the bedrock of a new nation.

After Rome was published on February 19th by Forge in hardcover ($24.99 or C$28.99, 332pp).

Published on February 20, 2013 06:00

February 18, 2013

Guest post by David Gillham: Watch, Listen, Eat

How can historical novelists make their chosen eras feel tangible and vibrant? David Gillham, author of the acclaimed debut novel City of Women, is stopping by the blog with an essay about how he re-created the atmosphere of 1943 Berlin—the city of his heroine, Sigrid Schröder—by spicing his narrative with descriptions of period films, music, and food.

~

One way I tried to build the atmosphere of Sigrid’s Berlin was by introducing wartime movies, music, and food into the narrative. Of course, when Sigrid attends the cinema, it not really to watch a movie. She’s looking for a small space of privacy, which is why she favors war movies. These didn’t do very well at the box office in Berlin; the audiences for them were usually sparse. The average Berliner was less interested in seeing propaganda films such as Soldiers of Tomorrow than Heinz Rühmann in escapist fare such as The Gas Man, or Gustaf Gründgens in a lavish eighteenth-century costume drama. For more recent movies that capture either the essence of Berlin or the stunning contradictions of the war years, I’d recommend Cabaret and Europa, Europa.

One way I tried to build the atmosphere of Sigrid’s Berlin was by introducing wartime movies, music, and food into the narrative. Of course, when Sigrid attends the cinema, it not really to watch a movie. She’s looking for a small space of privacy, which is why she favors war movies. These didn’t do very well at the box office in Berlin; the audiences for them were usually sparse. The average Berliner was less interested in seeing propaganda films such as Soldiers of Tomorrow than Heinz Rühmann in escapist fare such as The Gas Man, or Gustaf Gründgens in a lavish eighteenth-century costume drama. For more recent movies that capture either the essence of Berlin or the stunning contradictions of the war years, I’d recommend Cabaret and Europa, Europa.

You can still find a lot of popular music from the time period. In the book, Sigrid’s mother-in-law is listening to Lale Andersen singing on the radio. Andersen’s number-one wartime success was the ubiquitous “Lili Marleen”—a song that created such a stir that even British forces fighting in North Africa adopted it as one of their favorite tunes.

Naturally, classical music was still at the top of German radio playlists during the war: Beethoven, Mozart, Bach—though the music of all Jewish composers was banned from the airwaves. If you’re interested in the antic, often slightly loopy music of pre-Nazi Berlin, which Sigrid would have listened to while growing up, there are still recordings available of entertainers such as Margo Lion, the famously hilarious cabaret singer, or the popular ensemble known as the Comedian Harmonists. Marlene Dietrich was “falling in love again” in the golden twenties and early thirties, and later recorded a number of her songs from the era in English. The internationally acclaimed chanteuse Ute Lemper has released renditions of cabaret songs that were all the rage in Berlin between the wars, in both English and the original German (“Ich Bin ein Vamp!” for example). Max Raabe and the Palast Orchester are phenomenal at re-creating the music of that time (from “Fräulein, Pardon” to “Mein Gorilla.”)

Naturally, classical music was still at the top of German radio playlists during the war: Beethoven, Mozart, Bach—though the music of all Jewish composers was banned from the airwaves. If you’re interested in the antic, often slightly loopy music of pre-Nazi Berlin, which Sigrid would have listened to while growing up, there are still recordings available of entertainers such as Margo Lion, the famously hilarious cabaret singer, or the popular ensemble known as the Comedian Harmonists. Marlene Dietrich was “falling in love again” in the golden twenties and early thirties, and later recorded a number of her songs from the era in English. The internationally acclaimed chanteuse Ute Lemper has released renditions of cabaret songs that were all the rage in Berlin between the wars, in both English and the original German (“Ich Bin ein Vamp!” for example). Max Raabe and the Palast Orchester are phenomenal at re-creating the music of that time (from “Fräulein, Pardon” to “Mein Gorilla.”)

For those interested in what the average Berliner Hausfrau was serving at the table during the war, I recommend Gisela McBride’s Memoirs of a 1000-Year-Old Woman. Her autobiography stretches from the late twenties to the war’s end, and is chock-full of details illuminating everyday life, including recipes. (I cannot vouch for the healthfulness of any of these dishes, or the taste, but if you need recipes for cabbage dumplings, cabbage fish rolls, cabbage pie, or cabbage strudel, you’ll find them there.)

~

City of Women by David Gillham is published by Fig Tree in the UK (pb, £12.99, 400pp) and Amy Einhorn/Putnam in the US (hb, $25.95).

~

One way I tried to build the atmosphere of Sigrid’s Berlin was by introducing wartime movies, music, and food into the narrative. Of course, when Sigrid attends the cinema, it not really to watch a movie. She’s looking for a small space of privacy, which is why she favors war movies. These didn’t do very well at the box office in Berlin; the audiences for them were usually sparse. The average Berliner was less interested in seeing propaganda films such as Soldiers of Tomorrow than Heinz Rühmann in escapist fare such as The Gas Man, or Gustaf Gründgens in a lavish eighteenth-century costume drama. For more recent movies that capture either the essence of Berlin or the stunning contradictions of the war years, I’d recommend Cabaret and Europa, Europa.

One way I tried to build the atmosphere of Sigrid’s Berlin was by introducing wartime movies, music, and food into the narrative. Of course, when Sigrid attends the cinema, it not really to watch a movie. She’s looking for a small space of privacy, which is why she favors war movies. These didn’t do very well at the box office in Berlin; the audiences for them were usually sparse. The average Berliner was less interested in seeing propaganda films such as Soldiers of Tomorrow than Heinz Rühmann in escapist fare such as The Gas Man, or Gustaf Gründgens in a lavish eighteenth-century costume drama. For more recent movies that capture either the essence of Berlin or the stunning contradictions of the war years, I’d recommend Cabaret and Europa, Europa.You can still find a lot of popular music from the time period. In the book, Sigrid’s mother-in-law is listening to Lale Andersen singing on the radio. Andersen’s number-one wartime success was the ubiquitous “Lili Marleen”—a song that created such a stir that even British forces fighting in North Africa adopted it as one of their favorite tunes.

Naturally, classical music was still at the top of German radio playlists during the war: Beethoven, Mozart, Bach—though the music of all Jewish composers was banned from the airwaves. If you’re interested in the antic, often slightly loopy music of pre-Nazi Berlin, which Sigrid would have listened to while growing up, there are still recordings available of entertainers such as Margo Lion, the famously hilarious cabaret singer, or the popular ensemble known as the Comedian Harmonists. Marlene Dietrich was “falling in love again” in the golden twenties and early thirties, and later recorded a number of her songs from the era in English. The internationally acclaimed chanteuse Ute Lemper has released renditions of cabaret songs that were all the rage in Berlin between the wars, in both English and the original German (“Ich Bin ein Vamp!” for example). Max Raabe and the Palast Orchester are phenomenal at re-creating the music of that time (from “Fräulein, Pardon” to “Mein Gorilla.”)

Naturally, classical music was still at the top of German radio playlists during the war: Beethoven, Mozart, Bach—though the music of all Jewish composers was banned from the airwaves. If you’re interested in the antic, often slightly loopy music of pre-Nazi Berlin, which Sigrid would have listened to while growing up, there are still recordings available of entertainers such as Margo Lion, the famously hilarious cabaret singer, or the popular ensemble known as the Comedian Harmonists. Marlene Dietrich was “falling in love again” in the golden twenties and early thirties, and later recorded a number of her songs from the era in English. The internationally acclaimed chanteuse Ute Lemper has released renditions of cabaret songs that were all the rage in Berlin between the wars, in both English and the original German (“Ich Bin ein Vamp!” for example). Max Raabe and the Palast Orchester are phenomenal at re-creating the music of that time (from “Fräulein, Pardon” to “Mein Gorilla.”) For those interested in what the average Berliner Hausfrau was serving at the table during the war, I recommend Gisela McBride’s Memoirs of a 1000-Year-Old Woman. Her autobiography stretches from the late twenties to the war’s end, and is chock-full of details illuminating everyday life, including recipes. (I cannot vouch for the healthfulness of any of these dishes, or the taste, but if you need recipes for cabbage dumplings, cabbage fish rolls, cabbage pie, or cabbage strudel, you’ll find them there.)

~

City of Women by David Gillham is published by Fig Tree in the UK (pb, £12.99, 400pp) and Amy Einhorn/Putnam in the US (hb, $25.95).

Published on February 18, 2013 18:53

February 16, 2013

Rosemary McLoughlin's Tyringham Park, a dramatic Irish saga

I first came across Rosemary McLoughlin's debut novel in the publisher's catalog, which included a blurb from Irish women's magazine Woman's Way. "The Last September meets Downton Abbey," it was called.

I first came across Rosemary McLoughlin's debut novel in the publisher's catalog, which included a blurb from Irish women's magazine Woman's Way. "The Last September meets Downton Abbey," it was called. Tyringham Park takes a few pages from the Downton playbook in that it mostly takes place on an enormous country estate during and after WWI, though the setting is Ireland's County Cork rather than rural England. However, while wartime troubles and the painful Anglo-Irish relations of the era play a small role, they take a back seat to the tragedies that blight the aristocratic Blackshaw family over the span of 26 years.

McLoughlin certainly knows how to spin a dramatic story. Her classic Gothic soap opera is filled with depictions of pastimes among the rich and privileged, petty jealousies, cross-class lust, shocking twists, unexpected triumphs, and nasty characters you'll love to hate.

The early sections are the hardest to read, with disturbing images of the physical and verbal abuse inflicted upon the young Blackshaw sisters. Their mother Edwina ignores them, their absent father prefers spending time at London's War Office, and their cruel nanny Nurse Dixon takes her pent-up frustrations out on her charges.

Eight-year-old Charlotte turns mute for a time after her toddler sister Victoria, "the pretty one," disappears one day in 1917. Rumors fly that Victoria was abducted by Tyringham Park's former seamstress, Teresa Kelly, who loved her but who had left to marry a farmer in New South Wales. The kidnapping of a child is a scenario no family should ever endure, but such was her toxic home environment that I hoped Teresa had succeeded. Teresa proves untraceable, so Victoria's fate remains unknown.

Charlotte bears the brunt of her mother's displeasure because she's plain and overweight. She grows up troubled and unhappy until kindly servants and family friends take an interest in her and encourage her brilliant talents in horsemanship and painting. Still, her parents' neglect and the twisted pain of her childhood hangs heavily over her during her adolescence, and her loneliness and lack of self-confidence leads her to make dumb decisions about her future. I turned the pages avidly, unaware of where the plot might be leading and watching for signs that Charlotte would find the strength to escape.

Later scenes move the storyline along to Dublin, Paris, and the Australian countryside, while flashbacks provide perspective on Edwina's heartless attitude and Nurse Dixon's violent vindictiveness. Tyringham Park is very good at depicting the patterns of misery that repeat over generations, and with their tendencies toward arranged marriages, this affects the wealthy the most. There are many characters here that deserve readers' pity, and comparatively few to admire, but McLoughlin is a fluid storyteller, and I found it addictive escapism all the same.

Tyringham Park was published by Penguin UK in February 2013 at £7.99 (514pp, paperback). Thanks to the publisher for sending me a copy at my request.

Published on February 16, 2013 11:08

February 11, 2013

Book review: The Passing Bells, by Phillip Rock

Readers should be forgiven if they delve into Phillip Rock’s former bestseller and initially find themselves picturing Downton Abbey’s famous cast. The book has a similar premise — a noble English family and their servants have their lives upended by World War I — and more resemblances abound. The Countess of Stanmore is American, and her overseas relative disturbs the careful social hierarchy at their Sussex estate. Below stairs, a new housemaid learns her place. Their personalities come alive via elegant parties and cross-class love affairs.

Readers should be forgiven if they delve into Phillip Rock’s former bestseller and initially find themselves picturing Downton Abbey’s famous cast. The book has a similar premise — a noble English family and their servants have their lives upended by World War I — and more resemblances abound. The Countess of Stanmore is American, and her overseas relative disturbs the careful social hierarchy at their Sussex estate. Below stairs, a new housemaid learns her place. Their personalities come alive via elegant parties and cross-class love affairs. But the Grevilles aren’t the Crawleys, and as its new cover reminds us, The Passing Bells was here first. While equally as engrossing and full of nuanced characterizations, it offers an even meatier story, traveling places the show never ventured and addressing period issues through realistic, heartfelt drama.

The plot follows the younger generation almost exclusively. Charles, the Greville heir, timidly pursues rich businessman’s daughter Lydia Foxe, knowing his father disapproves, while Lydia and family friend Fenton Wood-Lacy deny their attraction. When war breaks out, all see their lives transformed. Chicago cousin Martin Rilke becomes the novel’s Everyman — his candid written observations on English aristocrats bring their differences home sharply — as his journalistic talents lead him to the front lines. The devastation at Gallipoli and the Somme has that much more impact when characters we care about are involved. Even Alexandra Greville, the pampered social-butterfly daughter, has a shocking coming-of-age.

From busy London newsrooms to a Yorkshire factory to the trenches, Rock is especially good at scene-setting and dialogue, and while his themes are unmissable, the characters’ engagement with their changing world is strong and moving. For some, war is futile, while for others, it gives their lives purpose. This fabulous reissue is tailor-made for post-Edwardian aficionados, who will be thrilled to know that two more volumes follow.

Originally published in 1978, The Passing Bells was reissued by William Morrow in trade paperback in December 2012 at $15.99. I enjoyed it so much that I requested the subsequent two titles for review, too. This writeup first appeared in the Historical Novels Review in February as an "online exclusive."

Published on February 11, 2013 18:38

February 9, 2013

Book review: Maria and the Admiral, by Rachel Billington

“We all have a story at our core that we may disown or admit. It is often about love.”

“We all have a story at our core that we may disown or admit. It is often about love.” In 1822, Maria Graham is a travel writer, illustrator, and English ship captain’s widow. Although the latter status gains her entry into society, she takes greater pride in her intellect. After her husband dies while they’re rounding Cape Horn, she settles in at his intended destination of Valparaiso, Chile, exhilarated at the thought of beginning anew. She’s confident her future will involve Admiral Lord Cochrane, the Napoleonic war hero who helped win Chile its independence.

Cochrane has a wife back home, but Maria sees herself as his ideal companion, and her lofty tone is entertainingly witty. “When society tutted that I had ‘set my cap’ at Lord Cochrane,” she writes, “I cocked a snook at them – I never wore anything but a turban.” The novel presents her recollections about their affair and her interactions with native Chileans (she prefers the company of foreigners to other expats), as well as her observations on South America’s volatile politics and gorgeous scenery. The changing colors of the majestic Andes are beautifully described.

Indeed, one could imagine this novel was the real woman’s authentic memoir – it adopts a period-appropriate formality – if not for the fact that this fictional Maria, supposedly writing from beyond the grave, sometimes breaks in to address modern audiences directly. Free from the constraints of 19th-century morality, she expands upon her published journals, which are silent on the true nature of her relationship with Cochrane.

Readers who can adjust to this conceit should enjoy her travelogue, which later sees her accompanying Cochrane to Brazil, a country she finds vulgar because its economy depends on slavery. Maria Graham never let society’s rules sway her opinions or desires, and with insightful skill, Billington has brought her adventurous heroine back into the limelight.

Maria and the Admiral was published in 2012 by Orion (UK) at £18.99 (hb, 350pp), and the paperback will be out in May 2013. I bought a copy in a shop on London's Charing Cross Rd while I was overseas for the HNS Conference last October. This review also appears in February's Historical Novels Review.

Published on February 09, 2013 08:00

February 7, 2013

Book review: The Typewriter Girl, by Alison Atlee

Alison Atlee's The Typewriter Girl offers a multiplicity of attractions. In addition to the activities and engineering marvels of the Victorian seaside resort where it takes place, it has a strong, compelling voice and interesting characters with dilemmas anchored in their time.

Alison Atlee's The Typewriter Girl offers a multiplicity of attractions. In addition to the activities and engineering marvels of the Victorian seaside resort where it takes place, it has a strong, compelling voice and interesting characters with dilemmas anchored in their time. Betsey Dobson stands out from the get-go, and not just because she's "alarmingly tall." Having been fired from her job as a typist at a London insurance firm after she's caught writing herself a fake reference, she boards a train to the coast where a new start awaits her, or so she hopes.

A Welshman named John Jones has decided to employ her as the manager of the new excursions scheme for the Idensea Pier & Seaside Pleasure Building Company; he sees something in her that nobody else has. She needs this opportunity, since with no means of support or even sufficient travel fare, it's the only thing she has left.

Betsey may be inexperienced, but she's smart, bold, and good with numbers. Her self-assurance sometimes fades, though, when she discovers all the obstacles she's up against. Already dubious about opening his upscale venue to day-trippers on corporate outings, resort owner Sir Alton Dunning is baffled by females in the workplace, especially this particular "manageress" (a term Betsey hates). At one point, she must give a presentation defending the value of the excursions program before members of the all-male board — who don't know what to make of a "woman without a tray." Her frustration is palpable.

This debut novel is literary fiction of a unique sort, one in which social issues and tough female characters combine with elegant turns of phrase and angsty romance. Betsey and John form an alliance that develops into mutual lust, or maybe even love, but she sees no future for them. John wants to "marry up," and rich and snobby hotel guest Miss Lillian Gilbey is his best chance to do so. For her part, Betsey is too proud to settle for a dalliance, despite her sexual history. She's had other lovers and once lived with another man, and shocks John by revealing that fact.

The text is rich in period details, much like an exquisitely designed turn-of-the-century scrapbook. At times it feels a bit overstuffed, and the pacing can be correspondingly slow in places, but Atlee's characters have many layers, and it's worth the time getting to know them. Turn the pages too quickly, and you might miss something important. The dialogue feels consistently fresh and real. Betsey has a mouth on her, letting drop the occasional curse, and it's impossible not to cheer on a character whose personality doesn't fit with stiff Victorian propriety. John doesn't come from an exalted background either, which becomes another link drawing them together.

The romantic tension between them has an intense emotional pull, and his belief in her allows her to "dream wildly, without boundaries." Isn't that a terrific way of putting things? In this uncompromising era, a penniless woman like Betsey shouldn't expect anything good to come her way, but she charts her own future regardless. The ending, while satisfying, leaves a question or two unanswered, just a slight false note in this enjoyable novel of a determined woman who refuses to sell herself short.

~

The Typewriter Girl was published by Gallery/Simon & Schuster in February ($15.00/C$17.00, trade paperback, 367pp).

Published on February 07, 2013 10:00

February 5, 2013

For the TBR Pile Challenge: Esmeralda Santiago, Conquistadora

Entry in the 2013 TBR Pile Challenge: #2 out of 12

Entry in the 2013 TBR Pile Challenge: #2 out of 12Years on TBR: 1.5

Edition owned: Knopf, 2011 (ARC, 410pp).

Since the TBR Challenge includes 12 titles, my plan is to read and review one each month during 2013. I chose Conquistadora as my second selection because while I love the Downton readalikes, I really do, I needed to escape turn-of-the-century England and read something different. An epic literary historical set in mid-19th century Puerto Rico suited my purposes nicely. My copy is a signed ARC, which I received at BEA in 2011. I spotted the paperback on a Barnes & Noble display table last weekend, so it's still pretty current.

The female lead of Conquistadora is Ana Larragoity Cubillas, a strong-willed girl who grows into an even more determined woman. Her life is chronicled simultaneously with that of the land, Puerto Rico, she claims for her own. To provide a more rounded treatment of its history and culture, and perhaps to give readers a periodic break from Ana's selfish mindset, Santiago allows equal time for the perspectives of others — relatives, associates, African slaves — whose lives intersect with hers.

As a young girl in Spain, Ana dreams of following in the footsteps of an ancestor, Don Hernán, who voyaged to the 15th-century Caribbean with Ponce de León. He left behind journals about his adventures that hold her enthralled. When she meets twin brothers Ramón and Inocente Argoso, heirs to a sugar plantation, they become the means to an end. She weds Ramón and is surprised to learn they expect her to act as Inocente's wife, too. (Quite a lot of bed-hopping occurs in this book.)

Her ambition drives the Argoso family (the brothers; their parents; and their cousin, Elena, Ana's first lover) across the ocean. Not long after they arrive, 18-year-old Ana and the men separate from the others. They travel along an overgrown, bug-infested trail to settle in at a rustic, under-performing, remote estate they name Hacienda los Gemelos ("of the Twins"). The rest of the family remains in sunny San Juan, where they set up new lives and worry about Ana's bad influence on the men.

Ana devotes herself to the plantation with an all-consuming intensity; it legally belongs to her father-in-law, who grants them five years to make a success of the place. By all accounts, they should fail, since they have too few people for their large acreage, but he doesn't count on Ana and her insistence on squeezing every last drop of work out of the slaves. Although she treats "her people" well, by the era's standards, the estate depends heavily on slave labor, and for that reason Ana will fight to her last breath to keep the cruel institution alive.

One of the points the novel brings home most forcefully is the fact that by 1844, nearly all of Spain's colonies had gained independence and abolished slavery... all but Cuba and Puerto Rico. The personal stories about the ethnic heritage of many slaves, such as the Mbuti housemaid called Flora, add considerable interest and diversity to the storyline. From time to time the plot slips into information dumps, though, relaying facts and figures on the Caribbean slave trade more ponderously than a fictional work should.

Conquistadora has been described as a Puerto Rican Gone with the Wind, which I found was somewhat valid. Ana has all the obstinacy and intelligence of Scarlett, and she holds onto the land just as tightly, but she doesn't have the same charm. Although I never really found myself gripped by the story, I read it with interest, up to a point. That point came about 100 pages from the end, when Ana's personality began to grate, and she and her household members' fates became progressively more predictable.

So, a mixed report on this one. Definitely worth reading if you know little about Puerto Rican history or appreciate heroines who defy stereotypes and cultural expectations. However, the isolated plantation setting, as full of life as it is, works to the novel's detriment, as doesn't give Ana enough space to grow or change. The finale leaves room for a potential sequel, and if that's the case, I hope it gives Ana a greater opportunity to shine.

Published on February 05, 2013 18:00

February 3, 2013

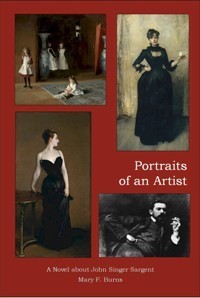

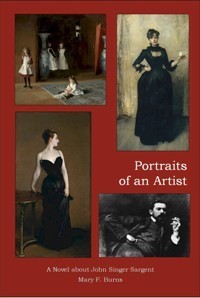

Guest post by Mary F. Burns: The Painting That Started Me Writing

Mary F. Burns, author of the newly released Portraits of an Artist: A Novel about John Singer Sargent, is my guest at Reading the Past today. Readers often wonder where writers get their ideas, and on this note, Mary has contributed a lively essay describing how one of Sargent's paintings inspired her book and drew her toward writing fiction in the first place. Welcome, Mary!

~

The Painting That Started Me Writing...Mary F. Burns

It was November, 1999. I was about to turn fifty (in six months) and I could feel my literary clock ticking— if I didn’t start writing seriously now, it wasn’t going to happen. When my husband took a business trip to Washington, D.C. that month, I went with him, and strolled over to the National Gallery while he was in meetings. Fate and Chance and Serendipity all smiled down upon me that day—the largest-ever exhibit of John Singer Sargent paintings happened to be there that week. I went three times. I bought the exhibition catalog. I had never seen his work before, and I was stunned.

The painting that intrigued me the most was the enormous (7 x 7 foot) "Portraits d’Enfants," also known as the "Daughters of Edward Darley Boit." Seen in person, up close, the painting is haunting and mysterious, with heavily laid-on swashes of pure white paint that leap out of the utter darkness of shadows in the background.

The oldest daughter, Florence—I was to learn all their names in time—is more in shadow than light, her face not even visible. What kind of portrait was that? In fact, it isn’t even clear that the two girls standing in the back (next to Florence is Jane) are "daughters"—they’re dressed more like servants, with the younger two girls—Mary Louisa standing with her arms "at ease" and baby Julia on the floor—looking like stiff, dressed-up dolls. I kept thinking, there’s a story here, there’s some dark, uncanny, psychological tale hidden—and exposed—by all this paint. Who was this artist, and why did he paint a portrait like this?

I wanted to write a novel that told this story, whatever it was. But I realized that, quite frankly, I didn’t know how to write fiction. Oh, I wrote what I called "corporate fiction" in my daily work life (PR and communications) but it was time to do the real thing. I had just left my corporate job that year, and had time on my hands. I wrote a short story and submitted it to the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference—and was accepted! The story took third place! It was a fabulous four days of talking about nothing but writing—what joy! Four years later I was invited to the Squaw Valley Community of Writers program, a draft of a novel under my arm as I attended their excellent sessions. Six years after that my first historical novel was published: J—The Woman Who Wrote the Bible. And finally, finally, I turned back to my idea about John Singer Sargent and his mysterious portrait of the Daughters.

Upon doing a little online research, I found to my dismay that there was already a work of fiction about this painting! How often has that happened! (About four times, for me, with various topics.) Happily, it was a very short YA story that included ghosts and paranormal activities, so I didn’t think that would be a problem. But in researching the Boit family, I found a very interesting quote by Sister Wendy Beckett of PBS Art fame, referring to Sargent’s portrait of the girls:

"There’s something sad about the picture, and when I discovered that these four pretty, wealthy girls never married, not one of them, one begins to feel that Sargent had intuited something of that… Sargent was superb in showing what a person looked like. And we tend to forget that, even at 26, as he was then, he was able to suggest what a person was like, and what their future might be."

That, I felt, was the core of what my novel was going to show. With that idea of Sargent’s intuitive painting in my mind, I read numerous biographies of him and his friends and contemporaries, and the people whose portraits he painted. I studied his paintings, thinking and imagining who these people were, and how they had been portrayed in the painting, what was hidden and what was revealed. Then I finally had to put all the books and papers and websites aside and start writing.

That, I felt, was the core of what my novel was going to show. With that idea of Sargent’s intuitive painting in my mind, I read numerous biographies of him and his friends and contemporaries, and the people whose portraits he painted. I studied his paintings, thinking and imagining who these people were, and how they had been portrayed in the painting, what was hidden and what was revealed. Then I finally had to put all the books and papers and websites aside and start writing.

It took two years and many drafts of the book. I changed the point of view from first person to third person to multiple persons; I added and dropped characters; I lost my way a few times and found it again. And in the end, I discovered that I had unearthed a plausible story, a believable mystery that ‘fit’ with the haunted look of those four girls, and the man who painted their portrait—in addition to imaginatively chronicling other critical events in Sargent’s life, like the scandal of the "Madame X" portrait that compelled him to leave Paris for London.

It was a very different story from what I had imagined early on it might be—all writers know how those characters take hold after a bit and start telling their own tale, despite what the author thinks she wants to do! But it was one that I think—believe—hope—feels true to life, and that if Sargent were alive now and were to read it, he might nod his head in agreement that there’s something to it, after all.

~

Mary Burns lives in San Francisco with her husband Stu. She is a member of and reviewer for the Historical Novel Society, and she is on the planning board for the North American HNS Conference to be held in St. Petersburg, Florida in mid-June.

Mary Burns lives in San Francisco with her husband Stu. She is a member of and reviewer for the Historical Novel Society, and she is on the planning board for the North American HNS Conference to be held in St. Petersburg, Florida in mid-June.

Mary's novel Portraits of an Artist was published on February 1, 2013 by Sand Hill Review Press. Please visit her blog about all things Sargent as well as her book trailer.

~

The Painting That Started Me Writing...Mary F. Burns

It was November, 1999. I was about to turn fifty (in six months) and I could feel my literary clock ticking— if I didn’t start writing seriously now, it wasn’t going to happen. When my husband took a business trip to Washington, D.C. that month, I went with him, and strolled over to the National Gallery while he was in meetings. Fate and Chance and Serendipity all smiled down upon me that day—the largest-ever exhibit of John Singer Sargent paintings happened to be there that week. I went three times. I bought the exhibition catalog. I had never seen his work before, and I was stunned.

The painting that intrigued me the most was the enormous (7 x 7 foot) "Portraits d’Enfants," also known as the "Daughters of Edward Darley Boit." Seen in person, up close, the painting is haunting and mysterious, with heavily laid-on swashes of pure white paint that leap out of the utter darkness of shadows in the background.

The oldest daughter, Florence—I was to learn all their names in time—is more in shadow than light, her face not even visible. What kind of portrait was that? In fact, it isn’t even clear that the two girls standing in the back (next to Florence is Jane) are "daughters"—they’re dressed more like servants, with the younger two girls—Mary Louisa standing with her arms "at ease" and baby Julia on the floor—looking like stiff, dressed-up dolls. I kept thinking, there’s a story here, there’s some dark, uncanny, psychological tale hidden—and exposed—by all this paint. Who was this artist, and why did he paint a portrait like this?

I wanted to write a novel that told this story, whatever it was. But I realized that, quite frankly, I didn’t know how to write fiction. Oh, I wrote what I called "corporate fiction" in my daily work life (PR and communications) but it was time to do the real thing. I had just left my corporate job that year, and had time on my hands. I wrote a short story and submitted it to the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference—and was accepted! The story took third place! It was a fabulous four days of talking about nothing but writing—what joy! Four years later I was invited to the Squaw Valley Community of Writers program, a draft of a novel under my arm as I attended their excellent sessions. Six years after that my first historical novel was published: J—The Woman Who Wrote the Bible. And finally, finally, I turned back to my idea about John Singer Sargent and his mysterious portrait of the Daughters.

Upon doing a little online research, I found to my dismay that there was already a work of fiction about this painting! How often has that happened! (About four times, for me, with various topics.) Happily, it was a very short YA story that included ghosts and paranormal activities, so I didn’t think that would be a problem. But in researching the Boit family, I found a very interesting quote by Sister Wendy Beckett of PBS Art fame, referring to Sargent’s portrait of the girls:

"There’s something sad about the picture, and when I discovered that these four pretty, wealthy girls never married, not one of them, one begins to feel that Sargent had intuited something of that… Sargent was superb in showing what a person looked like. And we tend to forget that, even at 26, as he was then, he was able to suggest what a person was like, and what their future might be."

That, I felt, was the core of what my novel was going to show. With that idea of Sargent’s intuitive painting in my mind, I read numerous biographies of him and his friends and contemporaries, and the people whose portraits he painted. I studied his paintings, thinking and imagining who these people were, and how they had been portrayed in the painting, what was hidden and what was revealed. Then I finally had to put all the books and papers and websites aside and start writing.

That, I felt, was the core of what my novel was going to show. With that idea of Sargent’s intuitive painting in my mind, I read numerous biographies of him and his friends and contemporaries, and the people whose portraits he painted. I studied his paintings, thinking and imagining who these people were, and how they had been portrayed in the painting, what was hidden and what was revealed. Then I finally had to put all the books and papers and websites aside and start writing.It took two years and many drafts of the book. I changed the point of view from first person to third person to multiple persons; I added and dropped characters; I lost my way a few times and found it again. And in the end, I discovered that I had unearthed a plausible story, a believable mystery that ‘fit’ with the haunted look of those four girls, and the man who painted their portrait—in addition to imaginatively chronicling other critical events in Sargent’s life, like the scandal of the "Madame X" portrait that compelled him to leave Paris for London.

It was a very different story from what I had imagined early on it might be—all writers know how those characters take hold after a bit and start telling their own tale, despite what the author thinks she wants to do! But it was one that I think—believe—hope—feels true to life, and that if Sargent were alive now and were to read it, he might nod his head in agreement that there’s something to it, after all.

~

Mary Burns lives in San Francisco with her husband Stu. She is a member of and reviewer for the Historical Novel Society, and she is on the planning board for the North American HNS Conference to be held in St. Petersburg, Florida in mid-June.

Mary Burns lives in San Francisco with her husband Stu. She is a member of and reviewer for the Historical Novel Society, and she is on the planning board for the North American HNS Conference to be held in St. Petersburg, Florida in mid-June.Mary's novel Portraits of an Artist was published on February 1, 2013 by Sand Hill Review Press. Please visit her blog about all things Sargent as well as her book trailer.

Published on February 03, 2013 05:00

February 1, 2013

Book review: The Midwife's Tale, by Sam Thomas

Historian Sam Thomas’s debut novel introduces an appealing pair of female sleuths operating within a creatively original setting: York, England, during the country’s civil war. It’s 1644, and Parliamentary rebels are besieging the city, but within its walls, life carries on as usual.

Historian Sam Thomas’s debut novel introduces an appealing pair of female sleuths operating within a creatively original setting: York, England, during the country’s civil war. It’s 1644, and Parliamentary rebels are besieging the city, but within its walls, life carries on as usual.Lady Bridget Hodgson, one of York’s official midwives, must continue with her duties while finding a murderer. One of her close friends, Esther Cooper, has been convicted of poisoning her husband and will be burned at the stake unless Bridget pulls out all the stops to clear her.

The atmosphere feels tense in this swiftly-paced mystery, since it might not even matter if she succeeds. Although other suspects abound – Stephen Cooper had many enemies – he held Puritan sympathies, and the Lord Mayor knows it wouldn’t look good to let a Parliamentary supporter’s wife go free.

This makes for a great setting for a mystery. Bridget knows that in these troubled times, there’s no guarantee justice will be served. She has help, though, from a servant who turns up on her doorstep. Martha Hawkins comes with a lot of baggage, but her street-smarts and ingenuity come in handy, and the women form a solid partnership.

Although she’s only 30, Bridget is a formidable presence. A twice-widowed gentlewoman, she has the authority that comes with her position and a self-confidence derived from her rank. She reveals a vulnerable side, too, since she suffers the pain of having lost two children herself.

Bridget’s methods can be shockingly aggressive, but it’s all part of her job. A midwife’s tasks don’t begin or end in the birthing chamber, and this eye-opening look at their role is one of the book’s most intriguing aspects. Bridget must force unmarried pregnant women to name their children’s fathers since the city doesn’t want to pay for their bastards. She advocates for women, too, participating in both christenings and funerals at the sad (and sadly frequent) times when the babies fail to thrive. It’s also captivating to observe the network formed within the city – each woman has “gossips” who share her secrets and support her at times of need – and the havoc created when one of the links is broken.

As Bridget and Martha sort through a growing number of suspects and motives for the killing, both political and personal, the layout of bustling York comes into sharp focus, from the shadows of the Minster to its creepy alleyways to the wards where its rich leaders reside. The River Ouse flows steadily along throughout, full of the stink of the city’s waste.

There are some inconsistencies with forms of address (she is alternately called Lady Bridget and Lady Hodgson), but regardless, she’s a heroine well worth following here and on future adventures. The Midwife’s Tale is an accomplished and entertaining debut from a talented writer. Enhancing the fictional story is the fact that Bridget is based on a real person. For readers interested in learning more, the author’s website takes a detailed and spoiler-free look at the historical woman’s life and background.

The Midwife's Tale was published by Minotaur in January (hb, $24.99/C$28.99, 310pp). This is the final day for the author's blog tour with Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours.

Published on February 01, 2013 05:00

January 30, 2013

Hilary Mantel's Bring Up the Bodies wins again... and again

Within the past few days, Hilary Mantel's Man Booker-winning Bring Up the Bodies, which continues the story of Henry VIII's right-hand man Thomas Cromwell in 16th-century England, has made it to the top of two additional prize committees' lists.

Within the past few days, Hilary Mantel's Man Booker-winning Bring Up the Bodies, which continues the story of Henry VIII's right-hand man Thomas Cromwell in 16th-century England, has made it to the top of two additional prize committees' lists.Yesterday it was announced as the winner of the Costa Book of the Year, making it the first book to garner both the Booker and the Costa. The prize comes with a purse of £30,000 and, per an article in the Bookseller, the judges' decision was unanimous.

And, at the American Library Association's Midwinter conference in Seattle last weekend, Bring Up the Bodies was named to the 2013 Reading List in the historical fiction category. Per the ALA website: "The Reading List seeks to highlight outstanding genre fiction that merit special attention by general adult readers and the librarians who work with them." Awards are given in eight categories.

The Reading List committee helpfully provides readalike titles for each of the winners (see link above). Shortlisted titles in historical fiction were:

Sarah Thornhill by Kate Grenville (winner of the 2012 Australia General Fiction Book of the Year)

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller (winner of the 2012 Orange Prize)

Sutton by J.R.Moehringer

The Cove by Ron Rash (winner of the 2012 Langum Prize)

For fans of Bring Up the Bodies and its predecessor Wolf Hall, there's also the upcoming miniseries to look forward to.

Published on January 30, 2013 08:33