Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 118

May 10, 2013

Historical fiction picks at BEA 2013

Here we are with our annual look at the historical novels being promoted at BEA in a few weeks. There are a lot of them for 2013 – this isn't always the case – and I'm writing this post with deep envy because I won't be there myself (sob!). I'll be attending HNS and ALA, though, and figured two conferences in the same month was my limit. I hope the publishers will be saving some of these galleys for the library crowd in late June...

Here we are with our annual look at the historical novels being promoted at BEA in a few weeks. There are a lot of them for 2013 – this isn't always the case – and I'm writing this post with deep envy because I won't be there myself (sob!). I'll be attending HNS and ALA, though, and figured two conferences in the same month was my limit. I hope the publishers will be saving some of these galleys for the library crowd in late June... This post will be updated when new listings are posted at the BEA site and if/when Library Journal's galley guide is released, so watch this space. For now, I'm basing my listings on the BEA Show Planner, which is its usual cumbersome self, and the "galleys to grab" articles and ads in the 4/29 Publishers Weekly. I've added blurbs, booth numbers, stuff like that. For authors with historical novels at BEA who I neglected to include, please leave a note in the comments or drop me an email. As always, I recommend cross-checking these dates/times with the BEA site or your program book before hitting the show to avoid possible disappointment.

For those of you who will be at BEA, have a great time!

~Galleys to Grab~

Algonquin (booth 839)

Lee Smith, Guests on Earth - literary fiction about a young woman in a '30s North Carolina mental institution, where she meets Zelda Fitzgerald. Oct.

Bellevue Literary Press (booth 1105B)

Melissa Pritchard, Palmerino - literary fiction about Vernon Lee (nee Violet Paget), supernatural fiction writer, set a century ago and today. Jan '14.

Counterpoint (booth 1335)

Counterpoint (booth 1335)Lily Brett, Lola Bensky - an Australian rock journalist hits the London music scene in 1967. Sept.

Farrar Straus & Giroux (booth 1557)

Nicola Griffith, Hild - literary biographical novel of St. Hilda of Whitby in 7th-century England, from a multi-award winning writer. Nov.

Harlequin (booth 1238-39)

Loretta Nyhan and Suzanne Hayes, I'll Be Seeing You - epistolary WWII novel. May.

Shona Patel, Teatime for the Firefly - love story set amid India's tea plantations in the '40s. Sept.

HarperCollins (booth 2038-39)

Amy Tan, The Valley of Amazement - three generations of women, from 19th-century San Francisco to turn-of-the-century Shanghai and after. Tan will be speaking at the Library Journal Day of Dialog. Nov.

Simon Van Booy, The Illusion of Separateness - one man's act of mercy during WWII changes many lives. June.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (booth 1657)

Oliver Poetzsch, The Ludwig Conspiracy - modern mystery surrounding Ludwig, the late 19th-century "mad king" of Bavaria. Sept.

Little, Brown (booth 1829)

Little, Brown (booth 1829)Hannah Kent, Burial Rites - literary fiction surrounding a woman accused of murder in 1829 Iceland; debut novel based on a true story. Sept.

Kathleen Kent, The Outcasts - a woman on the run in the 19th-century West, from the author of The Heretic's Daughter and The Traitor's Wife/The Wolves of Andover. Oct.

C.J. Sansom, Dominion - alternate history set in the 1950s in which the Nazis rule Britain. Mulholland, Jan '14.

Milkweed (booth 1333A)

Larry Watson, Let Him Go - literary fiction set in 1952 North Dakota; a retired sheriff and his wife go after their missing grandson. Sept.

Overlook (booth 1509)

Andrew Rosenheim, The Little Tokyo Informant -WWII thriller set just before Pearl Harbor. Sept.

Penguin (booth 1520-21)

Sarah Jio, Morning Glory - dual-period mystery set in a Seattle houseboat community in 1959 and today. Plume, Dec.

Random House (booth 2739)Jo Baker, Longbourn - a reimagining of Pride & Prejudice from the servants' viewpoint. Knopf, Oct.Rhidian Brook, The Aftermath - literary fiction about British-German relations set in a defeated Hamburg, Germany, after WWII. Knopf, Sept.Jamie Ford, Songs of Willow Frost - mother-son story in 1920s & Depression-era Seattle. Ballantine, Sept.

Diana Gabaldon, pre-pub booklet with first seven chapters of Written in My Own Heart's Blood. Giveaway June 1st.Nancy Horan, Under the Wide and Starry Sky - Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife, from the author of the bestselling Loving Frank. Ballantine, Jan '14.Colum McCann, Transatlantic - three transatlantic crossings, spanning two centuries, linked by three women. Random House, June.

Diana Gabaldon, pre-pub booklet with first seven chapters of Written in My Own Heart's Blood. Giveaway June 1st.Nancy Horan, Under the Wide and Starry Sky - Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife, from the author of the bestselling Loving Frank. Ballantine, Jan '14.Colum McCann, Transatlantic - three transatlantic crossings, spanning two centuries, linked by three women. Random House, June. Simon & Schuster (booth 2638-39)

Simon & Schuster (booth 2638-39)Lynn Cullen, Mrs. Poe - on Frances Osgood's affair with the famed writer. Gallery, Sept.

Thomas Keneally, Daughters of Mars - Australian nurses in WWI Europe. Atria, Sept.

Kate Manning, My Notorious Life - a controversial midwife in 19th-century NYC. Scribner, Sept.

Indu Sundaresan, The Mountain of Light - epic novel about diamond hunters in Victorian India. Atria, Oct.

Sourcebooks (booth 829)

Charles Belfoure, The Paris Architect - an architect reluctantly helps hide Jews from the Nazis in occupied Paris. Oct.

W.W. Norton (booth 1920-21)

P.S. Duffy, The Cartographer of No Man's Land - literary fiction about a family divided by WWI, set in Nova Scotia and France. Liveright, Nov.

~Author Signings~

Note: Table signings are in the traditional autographing area in the back of the exhibit hall. Booth signings are at the publishers' booths in the main exhibit area.

Thursday, May 30th

Thursday, May 30th11am-noon (table 1)

Kathleen Kent, The Outcasts - see above under Little, Brown.

Noon-12:30pm (table 15)

Simon Van Booy, The Illusion of Separateness - see above under HarperCollins.

1-1:30pm (table 2)

Annapurna Potluri, The Grammarian - a French linguist travels to 1911 India and runs into a cultural divide. See my review. Feb '13 (already out).

1-2pm (table 14)

Sarah Jio, The Last Camellia - dual-period mystery (WWII and modern day) surrounding a rare flower found on an English country estate. Plume, May.

3-4pm (table 7)

Shona Patel, Teatime for the Firefly - see above under Harlequin.

Friday, May 31st

10-10:30am (table 15)

10-10:30am (table 15)Philipp Meyer, The Son -"An epic, multigenerational saga of power, blood, and land" beginning in 19th-century Texas. Ecco, June.

10:30am (booth 839, Algonquin)

Lee Smith, Guests on Earth - see above.

11am-noon

Elizabeth Wein, Rose Under Fire - the companion novel to Code Name Verity. Not just for YAs. Disney-Hyperion, Sept. (table 4)

Maile Meloy, The Apprentices, sequel to The Apothecary, which was YA fiction set in Cold War London. Putnam, June. (table 21)

11:30am (booth 1321, Grove/Atlantic)

Kent Wascom, The Blood of Heaven - literary epic of the southern frontier in the early 19th century. June.

1-2pm (table 3)

Larry Watson, Let Him Go - see above under Milkweed.

2-3pm

Jack Gantos, From Norvelt to Nowhere - sequel to his Newbery-winning Dead End in Norvelt. YA. FSG, Sept. (table 23)

Kirby Larson, Duke - WWII story about a boy and his dog. Ages 8 and up. Scholastic, Aug. (table 16)

Kirby Larson, Duke - WWII story about a boy and his dog. Ages 8 and up. Scholastic, Aug. (table 16)2:30-3pm (table 9)

M.J. Rose, Seduction - multi-period suspense involving Victor Hugo's lost journal. MIRA, May.

3pm-4pm (table 16)

Eliot Pattison, Bone Rattler - historical mystery set aboard a prison ship bound for the American colonies. Counterpoint (this has been out for a while; I wonder if this is the correct title).

Saturday, June 1st

10am (booth 1509, Algonquin)

Peter Quinn, Dry Bones - literary WWII thriller about an ill-fated OSS mission into the heart of the Eastern front.

Published on May 10, 2013 15:30

May 9, 2013

An interview with Anne Easter Smith, author of Royal Mistress

Historical novelist Anne Easter Smith is passionate about her chosen era: the 15th-century Wars of the Roses. Whether you're reading one of her novels or speaking with her for an interview, as here, it's easy to get caught up in her enthusiasm. Her newest biographical novel Royal Mistress introduces readers to Elizabeth "Jane" Shore, a beautiful and spirited silk merchant's daughter who becomes Edward IV's last and favorite mistress.

Historical novelist Anne Easter Smith is passionate about her chosen era: the 15th-century Wars of the Roses. Whether you're reading one of her novels or speaking with her for an interview, as here, it's easy to get caught up in her enthusiasm. Her newest biographical novel Royal Mistress introduces readers to Elizabeth "Jane" Shore, a beautiful and spirited silk merchant's daughter who becomes Edward IV's last and favorite mistress.In true epic fashion, Anne interweaves the viewpoints not only of Jane but of many others in the royal circle to give readers a wide-ranging look at these characters and the tumultuous times they lived through. Jane is a determined survivor whose good-hearted nature captures the heart of several high-ranking men and also makes her a fun and sympathetic heroine to follow on her adventures. With Royal Mistress just published, I took the opportunity to ask Anne some questions about her characters, the history, and the writing process.

This is your 5th historical novel set during the Wars of the Roses, and you're obviously very comfortable with the period and its major players. As you were writing Royal Mistress, did you find your characters – even ones you've written about before – were still able to surprise you?

They always do, thank goodness, or I would be bored writing about them! In Royal Mistress it was Richard of Gloucester – ”my Richard” I call him – who surprised me. I had to see him through Jane’s eyes, and he was not very kind to Jane – for his own rational reasons, although others saw it differently. William Hastings also surprised me, because though I knew he was always loyal to Edward, I had always found him rather pompous and certainly lecherous. He ended up being the most genuine in his love for Jane.

On account of his impotence, Jane attempts to secure an annulment from her husband William Shore through the church. While a valid option, this must have been an unusual step for a woman of her era to take. How unusual was it? Are there other examples you can point to?

Jane Shore, late 18th-century portraitYou are right. It was very unusual, and because there is no record that Jane and William were submitted to “the test,” we believe Edward may have smoothed the way for Jane. However, the record shows that Jane did appeal to the church for an annulment and it was granted three months later. Even though it might seem women had no rights back then, their marriage vows did entitle them to an expectation of marital intimacy and the chance of motherhood. The test for impotence I mentioned is detailed in the 12th-century lawbook written by Thomas of Chobham that was still consulted, and requires that a certain number of wise matrons surround a couple’s bed and watch while the wife tries to arouse her husband. If the effort proves futile, then the wife is given the go-ahead to petition the church for the annulment.

Jane Shore, late 18th-century portraitYou are right. It was very unusual, and because there is no record that Jane and William were submitted to “the test,” we believe Edward may have smoothed the way for Jane. However, the record shows that Jane did appeal to the church for an annulment and it was granted three months later. Even though it might seem women had no rights back then, their marriage vows did entitle them to an expectation of marital intimacy and the chance of motherhood. The test for impotence I mentioned is detailed in the 12th-century lawbook written by Thomas of Chobham that was still consulted, and requires that a certain number of wise matrons surround a couple’s bed and watch while the wife tries to arouse her husband. If the effort proves futile, then the wife is given the go-ahead to petition the church for the annulment. Jane takes pride in her status as a freewoman of the City of London. What privileges or rights would this have entitled her to?

I’m borrowing information that I found during a visit to the wonderful Museum of London. If you haven’t discovered it yet, you should!

“Freemen, or women, in London were were a privileged class; it is estimated that only about 1 in 4 of London men was a freeman. You became a freeman either by being born to parents who were one, by completing a trade apprenticeship, through paying a sum of money or, if you were a woman, by marrying a freeman. The rights of freemen and women included setting up a shop or running a business within the City.”

I also found that one of the privileges was they could choose where they were imprisoned.

Jane is good-hearted, loving, sensual, witty, and beautiful, and she doesn't make unreasonable demands on King Edward. She's known throughout London for using her position to help the less fortunate, and she does her best to stay away from politics – and the queen! Would you consider her an ideal royal mistress, or is there such a thing?

I would say she was an ideal mistress. She was not “kept” at the palace and so the queen did not have to face her rival every day, as was common with other kings’ mistresses. We are told she was not demanding, and unlike Alice Perrers, who was Edward III’s long-time mistress, she did not get given land or estates. I was confused by a review in the Historical Novels Review that called her “infamous,” which is a word that connotes “despicable, wicked, dishonorable” to me. Jane was none of those. Every single description that has come down to us of her is that she was kindhearted, pleasant, never harmed anyone and showed great humility during her penance. I thought I had conveyed those characteristics in the book, but perhaps I’m wrong!

"The Penance of Jane Shore" by William Blake (c1780)The period expressions scattered throughout the novel added a lot of color, like the exclamation "By Christ's nails!" or even the word "wagtail" as an uncomplimentary way of describing Jane. What are some of your favorites?

"The Penance of Jane Shore" by William Blake (c1780)The period expressions scattered throughout the novel added a lot of color, like the exclamation "By Christ's nails!" or even the word "wagtail" as an uncomplimentary way of describing Jane. What are some of your favorites? I like using old-fashioned words as well as turning sentences around so they sound more period. I enjoy being transported back into another world myself when I read historicals, and I think dialogue can help effect this. The old use of “aye” and “nay,” which we don’t use today (unless you’re in Scotland!); and words like “heed,” “addle,” “spawn” and “monstrous” come to mind as some we don’t use in our everyday language anymore. A couple of my favorites, which I confess to borrowing from Shakespeare are “bum-bailey” for a jerk, “clack-dish” and clatterer” for a chatterbox or gossip, and your above-mentioned “wagtail.” (I know Shakespeare is 16th century, but as there was very little written down in vernacular English before the famous Elizabethan playwrights, I feel many of those words were already used long before they wrote their plays down.)

Sophie Vandersand is Jane's good friend, and they help each other out on several occasions. How did you go about inventing Sophie's character and background?

Funny you should ask! To support the Newburyport Historical Society, I agreed to donate an auction item to name a character after the high bidder in my next book. My only condition was that the name had to fit in with 15th century London life. In other words, someone named Tiffany Wolinski or Cindy Wu would not do! The woman who won the item asked that instead of using her that I name a character after her six-year-old granddaughter Sophia Van Der Sande. In the 14th and 15th centuries, London had a sizeable community of Flemish weavers, who arrived with their craft to take advantage of the English wool trade. So I researched where many of those weavers would have lived and worked and gave her a more anglicized name, which after a century of living in London, would have been plausible. Et voila, Sophia or Sophie Vandersand was born.

Royal Mistress loops in many viewpoints in addition to Jane's, from her lovers and husbands to Richard III and even George of Clarence, drinking himself into oblivion just before his ignominious death in a wine barrel. Are there any whose scenes you enjoyed writing the most, or which were more difficult to conceptualize than others?

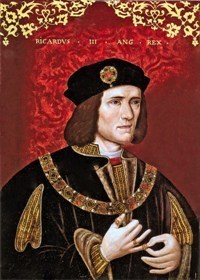

Richard IIIGolly, you ask in-depth questions! Yes, the scene in the Tower the day that Richard of Gloucester called Hastings to task for “treachery” was the hardest. I had to see it from Hastings’s point of view, who considered himself innocent, and from Richard’s who was convinced he was guilty. Both were being true to themselves in my opinion, but the outcome was heartbreaking for me to write even though I understood Richard’s motivation. (Enough of spoilers; don’t forget you have already read the book, Sarah!)

Richard IIIGolly, you ask in-depth questions! Yes, the scene in the Tower the day that Richard of Gloucester called Hastings to task for “treachery” was the hardest. I had to see it from Hastings’s point of view, who considered himself innocent, and from Richard’s who was convinced he was guilty. Both were being true to themselves in my opinion, but the outcome was heartbreaking for me to write even though I understood Richard’s motivation. (Enough of spoilers; don’t forget you have already read the book, Sarah!) Thanks, Anne – that should give readers a hint about a scene to anticipate! Things have been quite busy for you writing-wise, with five novels published since 2006. I'm curious to learn how your writing process has changed since publication of A Rose for the Crown.

I realize I had no idea what I was doing when I wrote Rose! I have since learned about structure, themes, motifs, etc. etc. and how to sequence big scenes and where the climax should be! Sounds simple, right, but I had never had a formal writing class in my life (other than learning grammar at British boarding school), so I’ve come a long way, baby! Funnily enough, however, I get more letters saying that Rose is still their favorite of my books.

Thanks for hosting me today, Sarah.

Thanks again, Anne, for taking the time to answer my questions!

~

Royal Mistress was published by Touchstone/Simon & Schuster in May at $16.00, or $18.99 in Canada (trade pb, 489pp, including glossary, author's note, and discussion questions). Visit Anne Easter Smith's website at www.anneeastersmith.com , which includes an entertaining blog entry in which the author interviews her main character.

Published on May 09, 2013 05:00

May 7, 2013

Bits and pieces

Just a short round-up of news bits from various sources...

Just a short round-up of news bits from various sources...The 7th edition of Genreflecting: A Guide to Popular Reading Interests was published by ABC-CLIO in late April. It can be considered a standard reference work for readers' advisory work in general and for discovering the appeal of fiction and nonfiction genres and individual books within them. I was pleased to be asked to write the historical fiction chapter (this was my project for the past two summers). My Historical Fiction II book was published in 2009, and this new chapter supplements it by discussing new titles and trends in historicals. Many other genres are likewise covered, of course, from crime, thrillers, and westerns to mainstream fiction, fantasy, horror, and nonfiction as well as other popular interests like urban fiction and graphic novels. Cynthia Orr and Diana Tixier Herald are the editors. Find more at the publisher's website.

A new batch of historical fiction reviews went online at the Historical Novel Society website on May 1st, both mainstream/small press and indie titles. There are over 300 in all. Have fun browsing!

Also in the Historical Novels Review's May issue, and available for all to view: Bethany Latham's fabulous cover story on trends and preferences in historical fiction cover art, which has quotes from both publishers and readers on this perennially fascinating subject, and "The Ghosts of Wartime Past," my interview with Simone St. James about An Inquiry Into Love and Death, her newest 1920s-era Gothic novel.

Finally, while you're over at the HNS website, don't forget to check out the spring issue of The Historian, the journal of the Historical Association (UK), which is entirely about historical fiction. It's online in full, complete with articles by Lindsey Davis on "true history," coverage of Downton Abbey, cover designs for children's historicals, and HNS founder/publisher Richard Lee's perspective on the British market for historical fiction.

Several months back, blog reader Tracy Whittington dropped me a note about her new book, Claiming Your History, which is a guide to the many ways people can incorporate their love for history into their daily lives. (This site is mentioned in it; I agree that reading historical fiction is a good way to do so!) I downloaded a copy and thought it was a wonderfully creative source for ideas on how you can form deeper connections with your past, from creating genealogies and oral histories to preserving heirlooms and learning more about your ancestors' language and religion. Tracy includes stories about her own family in it – she has tried out many of the suggestions she provides – and relevant web links. For those interested, it's available on Kindle ($3.99), and you can read the table of contents via Amazon.

I'm just finishing up a marathon reviewing session (three books in three weeks!) and am slowly returning to the real world. Next up on the blog, this Thursday, will be an interview with Anne Easter Smith about her new Wars of the Roses epic, Royal Mistress, which was released today.

Published on May 07, 2013 10:34

May 6, 2013

An interview with Sandra Byrd, author of Roses Have Thorns

When I first heard about the subject of Roses Have Thorns, I knew I had to read it. Elin von Snakenborg was a Swedish noblewoman who became a maid of honor to Elizabeth I and one of her closest confidantes. She married William Parr, brother to Henry VIII's last queen, and became known as Helena, Marchioness of Northampton. (And there's much more; the novel doesn't end there.) However, despite her prominent status at the Elizabethan court, Elin's story is little known and hasn't been told in fiction before.

When I first heard about the subject of Roses Have Thorns, I knew I had to read it. Elin von Snakenborg was a Swedish noblewoman who became a maid of honor to Elizabeth I and one of her closest confidantes. She married William Parr, brother to Henry VIII's last queen, and became known as Helena, Marchioness of Northampton. (And there's much more; the novel doesn't end there.) However, despite her prominent status at the Elizabethan court, Elin's story is little known and hasn't been told in fiction before.Sandra Byrd's engrossing novel about Elin's life injects this familiar Tudor setting with freshness and vitality. I thoroughly enjoyed it, and it even rekindled my longtime interest in fiction about royalty. Not only does Roses Have Thorns offer a perspective on Queen Elizabeth that readers rarely see, but Elin's story is fascinating in itself. I especially appreciated how the author brought to life the era's religious divisions, beliefs, and observances, which are critically important to the understanding of the historical period and characters.

I hope you'll enjoy the following interview, which shows her enthusiasm for the Elizabethan era as well as her delightful writing style. Please join me in welcoming Sandra Byrd!

The opening scenes set in Stockholm, just before Elin leaves on her journey, made the unfamiliar setting come alive. What was your favorite part about researching Elin’s Swedish background? Were there any fascinating things you learned about it that didn’t make it into the novel?

Today, we think of the Swedes as mild mannered and socially progressive – but in the era Elin lived in, they were more Viking than Ikea. Gustav Vasa, who was in power for nearly 40 years in the 16th century, took his country back from the Danes. He also "unmanned" a wedding guest who had sneaked into his daughter's bedroom, and then brutally beat her with his own fists. That daughter, Princess Cecelia, took Elin to England. King Erik, who had hoped to marry Elizabeth, was ultimately poisoned (apocryphally, in his pea soup) likely by his brothers. Both Gustav Vasa and Henry VIII referred to themselves as the Moses of their people, and I think they were alike in temperament and strength.

Elin's trip to England was much longer and was more arduous than I portrayed in the book. It took 10 months and included overland portions in freezing weather in order to evade the Danes. The women had a bit of Viking in them, too, or they could never had survived that harrowing trip.

One little bit of trivia that is touching, the planet group Karin is named after Karin Mansdottar, the mistress of (and later wife to) King Erik of this era.

I’ve read other historical novels on Elizabeth I that demonstrate her charm, intelligence, and power, and Roses Have Thorns shows these qualities very well, but I haven’t read many others that simultaneously emphasize her status as a woman alone, without any true peers. Did you find your opinions of her changing during the writing process?

I started thinking about this after a divorced friend told me that what she missed most from marriage was regular human touch. No one, literally or figuratively, could touch Elizabeth. It would have been a great breach of protocol and as she had no husband, children, parents or siblings who naturally would have been allowed to touch her, I began to sense what might have felt like a real loss to her.

She was not allowed to speak of her mother, something many women would naturally do, and to bring up her sister or brother would be to raise issues that were best left at rest. No one, really, had her back unless they were in it for something. She had no true friends; I wondered if that was one reason she dithered when dealing with Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary was one person who could have been her peer, under different circumstances. All of this helped me sense the tremendous loneliness that must have come with her position. It made personal sacrifice on behalf of her kingdom more poignant.

Author Sandra ByrdElin/Helena became very close to the Queen, married a well-known nobleman, and even served as chief mourner at Elizabeth’s funeral, yet her name isn’t very well known. Why do you think this is?

Author Sandra ByrdElin/Helena became very close to the Queen, married a well-known nobleman, and even served as chief mourner at Elizabeth’s funeral, yet her name isn’t very well known. Why do you think this is?I can't properly express how thrilled I was to have uncovered Elin during my research on Kateryn Parr. I think the focus has been on Lettice Knollys for so long because it was a long-standing love triangle with Dudley, because she and Elizabeth were cousins and looked alike, and because it was complicated from all angles and for a long time. The human drama inherent in that makes for good book material. Perhaps Lettice overshadowed all others. I don't really know, otherwise, but a fresh name was a rewarding discovery for me and when her husband's history tied in so neatly with the end of Mary, Queen of Scots, I knew I'd found my girl.

Why do you especially enjoy writing about ladies in waiting at the Tudor court?

I've always said I want to know the woman behind the gown and the crown. One effective way to do that is through the eyes of a friend. A rival is naturally predisposed against the queen, a servant is too lowly to be everywhere the queen would be or be privy to secrets. A friend loves us just as we are, but doesn't ignore our difficulties or character flaws, either. I have always loved the Tudors. I've credited Jean Plaidy for being my gateway drug to all things British historical. She did such a marvelous job with her books, it's held my interest for a lifetime.

The era’s religious turmoil is a major theme in Roses Have Thorns, and quotations from Scripture are inserted at natural points in the storyline. This made the setting feel that much more vibrant and authentic to me. How do you strike a balance between exploring Christian themes and making the novel appealing to mainstream readers?

Religion is important to a great many people the world over, and it is absolutely a part of the legitimate context for many eras and settings. I'm not Jewish, but I loved The Chosen. Its themes and challenges resonate with me as a person.

Religious turmoil was thickly woven into the fabric of the Tudor era – Henry VIII breaking with the church at Rome, a sharp turn toward Protestantism under Edward VI, a sharp turn toward Catholicism under Mary I, and then Elizabeth's via media. It influenced how people acted and the business of the kingdom for centuries. Faith of some kind of still important to many people.

Elizabeth prayed in many languages. She quoted scripture. I quoted her, quoting it. I feel that is different than my having an agenda, it's an understanding of her and of the women of the time, at least the ones I choose to explore. Because I spend hundreds of hours researching and writing on a topic, I choose the ones that interest me, which is often how historical women and Christian faith and power and relationships intersect. Hopefully, if I tell a good story, it will engage a wide group of people, Christian or not.

You mention in the Q&A at the end of the novel that you love reading Tudor fiction. It’s a popular era with readers, and I appreciated the fresh, lively perspective you brought to it. What other qualities do you look for when choosing Tudor-era novels to read? Also, given your experience as a writing coach, do you have any suggestions for writers looking to make their historical novels stand out?

I do look for historical accuracy, because if you've read widely enough in an era you know when something is wrong and it pulls you out of the story. At the same time, I challenge anyone to write 90,000 words on anything without making a mistake of some kind. Can't be done! Not only that, some of the things we think we "know" may themselves have come from questionable sources.

I want to love the heroine and the hero, but I want them to have to grow, too. I want both the facts and players that I know were there to be present (I read Tudor to read about Tudors, of course!) but I like to see something fresh and new, or a point of view I hadn't considered, but legitimately might.

I'm developing a session called Historical Novelist as Curator: What to Put In, What to Leave Out. I think that's one of the biggest tricks for historical novels. Enough of the right details to bring your readers there, but not so many that it sands the book's gears. I try to remember that an historical novel is a novel, noun, historical being the modifier. Although whatever historical details I include need to be right, the story has to come first.

Did you get a chance to visit any more sights relating to Helena’s life while visiting England last autumn for the Historical Novel Society conference?

I did visit Hampshire, and so was able to see Hurst Castle, which was great fun. I was so, so close to visiting Longford, but my English friends told me that it's privately owned and that I wouldn't be able to see it from any vantage point. It was thrilling to know I was very close though, and in the same area that Helena would have ridden. Each time I visit England, it's a kind of pilgrimage for me.

Thank you for having me, Sarah!

Thanks, Sandra, for taking the time to answer my questions! Best wishes for continued success with your novels.

~

Roses Have Thorns was published by Simon & Schuster's Howard Books in April at $14.99 (trade pb, 336pp). Sandra's previous Tudor-set novels are To Die For: A Novel of Anne Boleyn, and The Secret Keeper: A Novel of Kateryn Parr. Visit her website at http://www.sandrabyrd.com. This interview is a stop on the author's tour with Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours.

Published on May 06, 2013 05:00

May 2, 2013

Book review: Circles of Time, by Phillip Rock

This second volume in Rock’s engrossing trilogy (after

The Passing Bells

) about the titled Grevilles of Abingdon Pryory in Surrey sees them, their relatives, and friends attempting to restart their lives after WWI. It’s 1921, and Martin Rilke, the Countess of Stanmore’s nephew from Chicago, has just been named European bureau chief for an American news agency. He also faces a libel charge for his no-holds-barred book about brutality and incompetence on the front lines. His beautiful, widowed cousin Alexandra has returned to the family fold, amid her father’s strong disapproval over her marriage, and embarks on a romance with someone who would have been considered unsuitable ten years ago.

This second volume in Rock’s engrossing trilogy (after

The Passing Bells

) about the titled Grevilles of Abingdon Pryory in Surrey sees them, their relatives, and friends attempting to restart their lives after WWI. It’s 1921, and Martin Rilke, the Countess of Stanmore’s nephew from Chicago, has just been named European bureau chief for an American news agency. He also faces a libel charge for his no-holds-barred book about brutality and incompetence on the front lines. His beautiful, widowed cousin Alexandra has returned to the family fold, amid her father’s strong disapproval over her marriage, and embarks on a romance with someone who would have been considered unsuitable ten years ago. Times have changed – the previous order has crumbled – and even Lord Stanmore finally opens his eyes to the possibilities of the era. His perspective offers a bridge between the old and the new. But even during the joyous optimism of the Roaring ′20s, with its jazz bands, aeroplanes, and unrepressed sexuality, a cloud of melancholy lingers. These characters are the ones who survived, and the novel brings home the impossibility of their leaving the past behind. This truth echoes powerfully in the thread involving Charles, the eldest son, whose slow emergence from shell-shock is greeted with relief by his loved ones. The somber portrait of post-Versailles Germany toward the novel’s end shows more trouble yet to come.

Circles of Time is a true epic that flows effortlessly. Several poignant love stories are interwoven superbly with scenes of family drama, political strife in England and the Middle East, and depictions of the shifting mores that defined this energetic decade. It also reads as a potent anti-war novel, even with no battle scenes. Although it was first published over 30 years ago, and confidently evokes its setting, the prose exudes a crisp freshness that makes it seem like it was written yesterday. Not to be missed.

First published in 1981, The Passing Bells was reissued by William Morrow in January ($14.99, trade paperback, 425pp). This review also appears in May's Historical Novels Review .

Published on May 02, 2013 16:12

May 1, 2013

Guest post by Simon Acland: What was it really like on the First Crusade?

Simon Acland is stopping by today with an essay about primary source accounts of the First Crusade, the perspectives taken by each, and what we can learn from them. Simon's first novel, The Waste Land, intertwines the adventures of Hugh de Verdon, a former monk turned knight journeying to the Holy Land on the First Crusade, with a humorous modern-day account of the squabbling Oxford professors who discover Hugh's manuscript and seek to turn it into a bestselling novel. Welcome, Simon!

~

What was it really like on the First Crusade?by Simon Acland, author of The Waste Land

One of the challenges of writing about the First Crusade is imagining the details of everyday life at the end of the eleventh century. The period is really the tail end of the Dark Ages, and other than the Bayeux Tapestry there is almost no contemporary visual record of how people dressed or how soldiers fought, how far an army might travel in a day and what they might eat when they stopped. All of this has to be imagined. It is not really for the best part of another century that the picture becomes clearer, and by then customs have changed dramatically, not least because of the civilising impact on Europe of the contact made by the Crusaders with the far more advanced cultures of Byzantium and the Moslem world.

But because the First Crusade was such an extraordinary episode in history, there are many contemporary chronicles that relate the events that happened. These are mostly written by monks or priests who travelled with the leaders of the Crusade, and were charged by them with recording what happened. Of course these chroniclers were also charged with showing their individual lords and masters in a favourable light.

But because the First Crusade was such an extraordinary episode in history, there are many contemporary chronicles that relate the events that happened. These are mostly written by monks or priests who travelled with the leaders of the Crusade, and were charged by them with recording what happened. Of course these chroniclers were also charged with showing their individual lords and masters in a favourable light.

So there is the Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolymytanorum (“The Deeds of the Franks and other Jerusalemers”), written around 1101 by a companion of Bohemond of Taranto. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the Gesta Francorum tends to show Bohemond in rather a good light. The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres was probably started around the same time, but not completed until 1127/28, and because Fulcher travelled with Robert of Normandy, Stephen of Blois, Robert of Flanders, and later Baldwin of Boulogne, his perspective tends to be that of the Northern French. Raymond d’Aguilers’ Chronicle favours Raymond, Count of Toulouse, whose chaplain the author was (although his tone changes a bit after his apparent dismissal from this role towards the end of the Crusade!). And the Gesta Tancredi (“The Deeds of Tancred”) by Ranulph de Caen comes close to being a hagiography of Bohemond’s fiery nephew Tancred. Light is shed on the scene from different directions by Anna Comnena in The Alexiad, her history of her father, Byzantine Emperor Alexius I, because she encountered the Crusaders when they passed through Constantinople, and by Moslem historians such as Ibn al-Athir.

One thing that these accounts have in common is that they are not seeking to tell their readers what they already know. So there is little to be gleaned about the humdrum of everyday life from these documents. They relate extraordinary and unusual events, and for these they have provided much of the raw material for my novel The Waste Land. Some of the extreme events that appear in my book may seem exaggerated to modern readers, but they are there in the contemporary chronicles – newborn babies being abandoned on the way across the Anatolian desert in 1097 after the Battle of Dorylaeum, the cannibalism at the siege of Marrat-al-Numan in 1098, accounts of walking over the bodies of the dead after the siege of Antioch, the streets of Jerusalem running knee deep in blood in 1099. The First Crusade was unbelievably harsh. Some historians have estimated that 150,000 souls set out from various parts of Europe in 1096, and that three years later there were just 15,000 left to besiege Jerusalem. It is true that a few went home, like the disgraced Stephen of Blois, in his case only to be sent back to Outremer by his domineering wife Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror to redeem himself and die in 1102 at the second Battle of Ramleh. But based on these numbers, approaching nine out of ten of those who set off died along the way, in battle, of famine, or of plague.

This level of attrition is of course unthinkable in a modern army. But then Pope Urban II had made the Crusaders an offer that they could not refuse at the Council of Clermont, when he guaranteed them a place in heaven whether they made it to Jerusalem or died trying, and gave them carte blanche to behave however they wished on the way. Deus le volt!

~

Simon Acland worked as a venture capitalist for over 20 years and wrote several books on investing and leadership. The Waste Land is his first novel; it was published by Beaufort Books in March 2013 ($16.95 in pb or $9.99 on Kindle, 384pp). For more information, visit his website at http://www.simonacland.com/wasteland.htm

Simon Acland worked as a venture capitalist for over 20 years and wrote several books on investing and leadership. The Waste Land is his first novel; it was published by Beaufort Books in March 2013 ($16.95 in pb or $9.99 on Kindle, 384pp). For more information, visit his website at http://www.simonacland.com/wasteland.htm

~

What was it really like on the First Crusade?by Simon Acland, author of The Waste Land

One of the challenges of writing about the First Crusade is imagining the details of everyday life at the end of the eleventh century. The period is really the tail end of the Dark Ages, and other than the Bayeux Tapestry there is almost no contemporary visual record of how people dressed or how soldiers fought, how far an army might travel in a day and what they might eat when they stopped. All of this has to be imagined. It is not really for the best part of another century that the picture becomes clearer, and by then customs have changed dramatically, not least because of the civilising impact on Europe of the contact made by the Crusaders with the far more advanced cultures of Byzantium and the Moslem world.

But because the First Crusade was such an extraordinary episode in history, there are many contemporary chronicles that relate the events that happened. These are mostly written by monks or priests who travelled with the leaders of the Crusade, and were charged by them with recording what happened. Of course these chroniclers were also charged with showing their individual lords and masters in a favourable light.

But because the First Crusade was such an extraordinary episode in history, there are many contemporary chronicles that relate the events that happened. These are mostly written by monks or priests who travelled with the leaders of the Crusade, and were charged by them with recording what happened. Of course these chroniclers were also charged with showing their individual lords and masters in a favourable light. So there is the Gesta Francorum et aliorum Hierosolymytanorum (“The Deeds of the Franks and other Jerusalemers”), written around 1101 by a companion of Bohemond of Taranto. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the Gesta Francorum tends to show Bohemond in rather a good light. The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres was probably started around the same time, but not completed until 1127/28, and because Fulcher travelled with Robert of Normandy, Stephen of Blois, Robert of Flanders, and later Baldwin of Boulogne, his perspective tends to be that of the Northern French. Raymond d’Aguilers’ Chronicle favours Raymond, Count of Toulouse, whose chaplain the author was (although his tone changes a bit after his apparent dismissal from this role towards the end of the Crusade!). And the Gesta Tancredi (“The Deeds of Tancred”) by Ranulph de Caen comes close to being a hagiography of Bohemond’s fiery nephew Tancred. Light is shed on the scene from different directions by Anna Comnena in The Alexiad, her history of her father, Byzantine Emperor Alexius I, because she encountered the Crusaders when they passed through Constantinople, and by Moslem historians such as Ibn al-Athir.

One thing that these accounts have in common is that they are not seeking to tell their readers what they already know. So there is little to be gleaned about the humdrum of everyday life from these documents. They relate extraordinary and unusual events, and for these they have provided much of the raw material for my novel The Waste Land. Some of the extreme events that appear in my book may seem exaggerated to modern readers, but they are there in the contemporary chronicles – newborn babies being abandoned on the way across the Anatolian desert in 1097 after the Battle of Dorylaeum, the cannibalism at the siege of Marrat-al-Numan in 1098, accounts of walking over the bodies of the dead after the siege of Antioch, the streets of Jerusalem running knee deep in blood in 1099. The First Crusade was unbelievably harsh. Some historians have estimated that 150,000 souls set out from various parts of Europe in 1096, and that three years later there were just 15,000 left to besiege Jerusalem. It is true that a few went home, like the disgraced Stephen of Blois, in his case only to be sent back to Outremer by his domineering wife Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror to redeem himself and die in 1102 at the second Battle of Ramleh. But based on these numbers, approaching nine out of ten of those who set off died along the way, in battle, of famine, or of plague.

This level of attrition is of course unthinkable in a modern army. But then Pope Urban II had made the Crusaders an offer that they could not refuse at the Council of Clermont, when he guaranteed them a place in heaven whether they made it to Jerusalem or died trying, and gave them carte blanche to behave however they wished on the way. Deus le volt!

~

Simon Acland worked as a venture capitalist for over 20 years and wrote several books on investing and leadership. The Waste Land is his first novel; it was published by Beaufort Books in March 2013 ($16.95 in pb or $9.99 on Kindle, 384pp). For more information, visit his website at http://www.simonacland.com/wasteland.htm

Simon Acland worked as a venture capitalist for over 20 years and wrote several books on investing and leadership. The Waste Land is his first novel; it was published by Beaufort Books in March 2013 ($16.95 in pb or $9.99 on Kindle, 384pp). For more information, visit his website at http://www.simonacland.com/wasteland.htm

Published on May 01, 2013 04:00

April 29, 2013

Book review and commentary: Naomi Alderman's The Liars' Gospel

Storytelling is the lying art; a tale can’t be separated from its teller’s motives. This premise underlies Alderman’s daring new novel, which—rather than repeating the laudatory accounts of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—follows four individuals who interacted with Jesus (here called Yehoshuah) just before the Crucifixion.

Storytelling is the lying art; a tale can’t be separated from its teller’s motives. This premise underlies Alderman’s daring new novel, which—rather than repeating the laudatory accounts of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—follows four individuals who interacted with Jesus (here called Yehoshuah) just before the Crucifixion.His mother, Miryam, mourns him and his abandonment of his birth family; Iehuda can’t accept his charismatic friend’s intolerance for dissent and growing sense of entitlement and feels obligated to betray him. For Caiaphas, high priest of Jerusalem’s temple, subduing one rabble-rousing preacher is of lesser importance than appeasing Pontius Pilate and questioning his wife’s fidelity, while Bar-Avo (Barabbas) incites violence against his people’s oppressors.

Fabrications about Yehoshuah are spoken by many, whether to entertain, mislead, or provide comfort to others. Alderman presents an unabashedly Jewish perspective, and she re-creates first-century Judea, a land subjugated by tyrannical Rome, in intense, brutal detail. Religion and politics deeply intertwine in this profound work, which expresses blunt truths about leadership while exploring the healthy nature of debate about one’s faith.

The Liars' Gospel was published in March by Little, Brown (hb, $25.99, 320pp). Viking published it in the UK, and it's now out in paperback there (£8.99). I covered this one for Booklist's Feb 15th issue. Since then, I've been reading others' opinions about this novel, and since it reinterprets the life of Jesus, the reaction is about what I expected. Some Christian readers find it "borderline blasphemous" (as one Amazon reviewer did), while for others, it will stimulate and enlighten as it presents a new perspective on a story well known to most of us. Perhaps more than anything else, it exposes recorded history as the malleable, contentious, and biased thing that it is. I found it thought-provoking and very much worth reading.

Published on April 29, 2013 05:00

April 25, 2013

On Tanis Rideout's Above All Things, climbing mountains, and reader expectations

What a spectacular and heartrending novel.

What a spectacular and heartrending novel.Tanis Rideout's Above All Things proves how a talented writer can transform a reader's attitude toward a subject. George Mallory's expedition to Mt. Everest in 1924 hadn't ever been something I'd thought much about, or if I did, it rather frightened me. I don't like heights, and although I love vacationing in the mountains and gazing at the gorgeous views, my preferred sight of them is from the bottom.

Which is to say – I felt I would be the natural audience for precisely half of this book. Above All Things interweaves the experiences of Mallory, on his third and final attempt to scale Everest, and that of his wife, Ruth, as she passes an ordinary day at her home in Cambridge, England, caring for their three children and barely holding things together in his absence. Part domestic narrative from a woman's viewpoint, part energetic adventure. What would life have been like for Ruth, being married to a man who loved her passionately but whose uncontrollable ambition kept driving him away and into danger? That's what interested me the most.

To my surprise, I found myself absorbed by both accounts. I began reading with a knot in my stomach, dreading the novel's inevitable tragic ending, but it slowly unraveled as I became caught by the poignant love story and the particulars of the treacherous climb. Even more, I've been googling for information on Everest and Mallory ever since I finished.

In 1924, ten years after the British were called to fight a war "for King and Country," George is asked to join one last Everest expedition, the invitation citing the same call to honor. He had made two previous (failed) attempts to the summit and had promised Ruth that he was through with the mountain, but he can't resist its pull, and the chance for personal, professional, and national glory if he succeeds.

Ruth's story uses first-person present tense, while George's is third-person past. Both unfold with the same level of intimacy. Each of them looks back on key moments from their life together, so their accounts frequently overlap and blend.

Her life without him back home is a struggle, attempting to hide her intense fear while keeping up a normal family life and presenting a positive outlook to the reporters who badger her for information on George. Through her viewpoint, her quiet strength emerges, as well as her resentment at being left behind – and her continued love for him, regardless of the outcome.

George's part of the tale is completely fascinating. What an immense production it was for his team and the dozens of porters who dragged supplies for miles up the Himalayas. Then there was the multi-stage process for the climb to the peak, the brutally cold wind, the blistering sun, and the thin air which makes it hard to breathe and hinders mental clarity. I felt like I was making the trek alongside them, step by perilous step.

Also, this was the 1920s, when the use of canned oxygen was controversial – while taking cigarette breaks en route was unquestioned! With no path already mapped out, the climbers must rely on George to guide them. "The ice shows you, if you know how to read it," he tells Sandy Irvine, one of his fellow explorers: "It's like a slow river."

Sandy's is the third viewpoint included, and it makes the novel all the richer – and all the more tragic. Andrew "Sandy" Irvine is a 21-year-old Oxford student with minimal mountaineering experience, but he has youth and physical strength on his side. He has an appealing boyish confidence and looks to George to lead them up and down Everest safely. Sandy has left behind disappointed family members who don't understand his need to take the risk, as well as a messy love affair. It takes time for him to grasp the true human cost of their endeavor, and his realization is a painful, pivotal moment.

Sandy's is the third viewpoint included, and it makes the novel all the richer – and all the more tragic. Andrew "Sandy" Irvine is a 21-year-old Oxford student with minimal mountaineering experience, but he has youth and physical strength on his side. He has an appealing boyish confidence and looks to George to lead them up and down Everest safely. Sandy has left behind disappointed family members who don't understand his need to take the risk, as well as a messy love affair. It takes time for him to grasp the true human cost of their endeavor, and his realization is a painful, pivotal moment. The author takes some liberties with dates and characters. Although she comes clean about them in her note at the end, I found myself needing to unlearn some things after I was done. Still, this didn't lessen the impact the book had on me. Not just a gripping novel of high adventure, Above All Things also looks deep within to examine the forces that motivate us and drive us on, as well as the high price we can pay for the things we desire most. I certainly recommend it to historical fiction readers, Everest buffs or not.

Above All Things was published by Viking Penguin (UK) in March at £12.99 (trade pb, 385pp, cover art at top). It also appears in hardcover from Putnam/Amy Einhorn ($26.95) and from McClelland & Stewart in Canada (C$22.00). Thanks to Penguin UK for providing the review copy. For more background details, see also Tanis Rideout's earlier guest post about the artifacts she used in her research.

Published on April 25, 2013 17:00

April 23, 2013

Book review: Equal of the Sun, by Anita Amirrezvani

Amirrezvani’s lush and tautly suspenseful followup to The Blood of Flowers (2007) is set in a treacherous sixteenth-century court. Her splendid heroine is ambitious, proud, and refuses to marry. A canny strategist dedicated to her country’s preservation, she is too confident of her abilities to let an incompetent man rule.

Amirrezvani’s lush and tautly suspenseful followup to The Blood of Flowers (2007) is set in a treacherous sixteenth-century court. Her splendid heroine is ambitious, proud, and refuses to marry. A canny strategist dedicated to her country’s preservation, she is too confident of her abilities to let an incompetent man rule.Unlike the faraway queen of a “less important Christian kingdom,” however, Princess Pari Khan Khanoom, favorite daughter of Iran’s late shah, can never claim the throne and must conceal herself behind a velvet curtain while advising the nobility.

When the half-brother whose reign she initially supports turns into a paranoid tyrant, Pari takes matters into her own hands. Javaher, a eunuch who knows harem affairs and male politics equally well, becomes her loyal advisor while seeking his father’s killer.

The cast is large, the surroundings elaborate and colorful as this unlikely pair forms a strong alliance amid the intense and often shocking drama. Historical novels can serve to highlight the accomplishments of overlooked historical women, and Pari is a most deserving subject.

This review was written for Booklist last July. The paperback is out now from Scribner, with a new cover as above ($17, 464pp). With the 175-word limit for reviews, not everything could be spelled out in full, so here are some additional points I thought I'd make for potential readers:

(1) We could use more fiction with settings like this.

(2) The cutthroat politics of Equal of the Sun make the courtroom intrigue of The Other Boleyn Girl feel like a summer playground.

(3) This is the sort of historical novel that drops you right into a foreign culture without anything familiar to cling to. It takes active work to make the mental adjustments, but once there, it's an immersive experience. Think Cecelia Holland, Pauline Gedge, Michael Ennis, or Maurice Druon for comparisons.

(4) See (1).

Published on April 23, 2013 16:00

April 22, 2013

Writing a WWII Novel: A guest post by Ruth Francisco

Ruth Francisco, author of the WWII-era novel Camp Sunshine, is my guest at Reading the Past today. She has written her post in the form of a Q&A, discussing her research into the period, why the Florida Panhandle caught her attention as a setting, how she creates her characters, and why she chose to publish on Amazon Kindle after years of writing for large New York publishers. Welcome, Ruth!

Writing a WWII novel Ruth Francisco

Ruth Francisco worked in the film industry for 15 years before selling her first novel Confessions of a Deathmaiden to Warner Books in 2003, followed by Good Morning, Darkness, which was selected by Publishers Weekly as one of the ten best mysteries of 2004, and The Secret Memoirs of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Ruth Francisco worked in the film industry for 15 years before selling her first novel Confessions of a Deathmaiden to Warner Books in 2003, followed by Good Morning, Darkness, which was selected by Publishers Weekly as one of the ten best mysteries of 2004, and The Secret Memoirs of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

She now has nine novels, including the bestseller Amsterdam 2012, published as ebooks. She currently lives in Florida.

Tell us about your novel.

Camp Sunshine is based on the true story of Camp Gordon Johnston, a WWII amphibious training camp on Florida's desolate Gulf coast.

Here, twenty thousand young recruits test themselves to the limit in love and combat; politicos and tycoons offer aid with one eye to profit; women patrol the coast on horseback, looking for German subs; a postmaster's daughter, the only child on base, inspires thousands with her radio broadcasts; and a determined woman bravely holds together her family and the emotional soul of the camp.

But when Commanding Officer, Major Occam Goodwin, discovers a murdered black family deep in the forest, he must dance delicately around military politics, and a race war that threatens the entire war effort. Amid tragedy and betrayal, victory and terror, the fate of the soldiers and their country hangs perilously in the balance, as each endeavors to find his destiny.

What's the most important thing in writing an historical novel as opposed to other fiction?

In a word, research. I did an incredible amount of research for this novel. The vastness of my ignorance when it came to WWII military history was epic, so I had to do epic amounts of reading. I interviewed WWII vets. I visited WWII museums, especially photo archives. I watched WWII Army training films. Camp Gordon Johnston had a newspaper written by the troops, called The Amphibian, and I spent a month reading every issue on microfiche.

Black troops, Camp Gordon JohnstonResearch can surprise you and can lead you in new directions. In my research, I learned of the Double V campaign, which was an African-American civil rights movement intent on integrating the armed services during WWII. I'd never heard of it, and found it fascinating. Suddenly, I found myself with a subplot, which added depth to the novel. It made the story important.

Black troops, Camp Gordon JohnstonResearch can surprise you and can lead you in new directions. In my research, I learned of the Double V campaign, which was an African-American civil rights movement intent on integrating the armed services during WWII. I'd never heard of it, and found it fascinating. Suddenly, I found myself with a subplot, which added depth to the novel. It made the story important.

When writing historical fiction, how free can you be with historical fact? It is fiction, after all.

Certain things you can't mess with. Big events. You can't have the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1940. If your characters talk about the song “White Christmas” in 1942, you better be sure that it was written by then. Your readers are smarter than you are. They know more history. They make sport of catching oxymorons.

With lesser known events you can use “artistic license,” especially for little-known historic characters. For instance, I read that two twelve-year-old girls ran a radio station out of Panama City for WWII pilots in training. So I had my postmaster's daughter do the same thing, although the “real” postmaster's daughter was not a DJ. I changed the names of some of the officers who ran the camp because I wanted to involve them in a crime. You can make an historic character a murderer, but you have to be careful. It has to make sense.

In other words, with minor characters, motivations, thoughts, and feelings—let your imagination run wild. Historic events, details—stick to the facts.

Do you have any “tricks” for historical novel writing?

I study photos. I study the clothes and hairstyles. I try to imagine what the people are thinking in the picture, what came before the picture was taken, what came after. When I wrote The Secret Memoirs of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, I wrote almost exclusively from pictures. For instance, the famous picture of Jackie leaving the White House for the inaugural ball—I started with the event, then had her remember all the events that led up to that moment. One picture was an entire chapter.

In this book, I was particularly captured by the photos of WWII training maneuvers, and tried to imagine how an eighteen-year-old boy would react to having bombs explode all around him, waist-high in a swamp, stepping on creepy-crawly creatures. How frightened he must've been. There's a picture of civilian women sewing uniforms for the soldiers, and I get such a sense of dedication and sacrifice—so alien to our culture.

I also read a lot of fiction from the era, which is loads of fun, attentive to jargon, word usage, and attitudes. I listened to a lot of WWII era radio, G.I. Jill, Command Performance, all those great WWII shows. I also studied the pop culture of the era, the songs and dances.

You cannot assume people in another era would behave as you might to a situation.

I recall seeing the 1982 film The Return of Martin Guerre, set in 16th-century France, how tense and wild the people seemed, and it struck me profoundly—if you lived in an environment where you were constantly challenged, constantly on guard for a knife, constantly suspicious, constantly hungry, of course it would make you different. Writers often get caught with their characters having the same values and feelings of contemporary people. But people are different. The lines they will not cross. Their values. Their expectations. You have to use all the resources available to put yourself there. Imagine with all five senses, how things smelled and tasted.

Why did you add a mystery element to an historical novel?

The reason I tend to stick to the mystery/thriller genre, even when I'm writing an historical novel, is that I think it really helps to focus storytelling. A mystery demands a certain pacing. It demands parceling out of clues and information. It forces you to reveal character through action. I feel it really helps me as a writer to have a structured genre.

Where did you get the idea for your WWII story?

When I first drove to the Florida Panhandle from Los Angeles five years ago, I was smitten by the unspoiled beauty of the place. Thousands of Monarch butterflies flitted around my car as I drove down to Alligator Point. The first morning I woke to mullet jumping in the canal and screeching great blue herons. I looked out the window and saw snowy egrets and bald eagles. White squirrels jumping between branches of the pine trees. I had to write about this area.

One day I met a fisherman throwing a cast net into the water and asked him to show me how. We got to talking. When he heard I was a writer, he told me a local story about several dozen soldiers who lost their lives during a WWII training exercise while at Camp Gordon Johnston, how the tragedy was covered up.

Camp Gordon Johnston

Camp Gordon Johnston

So a few weeks later, I visited the WWII museum in Carrabelle, Florida and started doing research and interviewing people. I got completely sucked into the research, spending hours in the museum reading old newspapers. Everything fascinated me—especially the newspaper advertisements—from girdles to hair tonic. I started interviewing locals. Everyone had something to add.

I got overloaded with info, and had to step back for a few years. It wasn't until I interviewed Vivian Hess, who had been a little girl on the Camp Gordon Johnston Army base, that I felt I had a hook. Her stories were enchanting, and I felt I had to tell the story.

How do you keep a book character-driven when you have historical events that have to be covered?

You almost have to approach your characters as if you were an actor, imaging how you would feel, how you would react to historical events.

Despite all the WWII coverage, Camp Sunshine is definitely character-driven—told from the voices of an officer, a soldier, a little girl, and the wife of the postmaster. However, there were some factual events—like the drowning of dozens of soldiers in a training incident—that I had to include in the plot. And there were other historical elements I wanted to include, like the Black Regiments, and the Higgins crafts. It was hard, but extremely enjoyable to figure a way to integrate them into the story.

How do your characters “come” to you? How closely are they based on real characters or people you know?

The character Vivian Thatcher is based on my interviews with Vivian Hess, the real postmaster's daughter. Yet, as I wrote about her, the character separated herself from the real person, becoming increasingly impish and inventive. I wanted Major Goodwin to be a man of absolute integrity, but as I wrote him, he took on depth, becoming a man of great sorrow and great compassion. Vivian's mother was somewhat based on my own mother, but soon she became this incredibly strong woman who'd made great sacrifices, yet still yearned to be adventurous and free.

In my experience, you have a vision for your characters, but then, as the story unfolds, they become their own person. Some take on characteristics of friends and family. The imagination works from what it knows. It is a little odd. Like giving birth to children—you don't really know how they'll turn out. Inevitably, they turn out more interesting than you could possibly imagine.

What do you hope your readers come away with after reading your book?

I hope readers will feel as if they’ve time-traveled back to 1943. They'll hear the big band music and blues, and sense the incredible vitality of the whole country pulling together for the war effort. It inspires me how selfless people were. When I started the research, I didn't know that the Civil Rights Movement had its beginnings in WWII with soldiers agitating for an integrated military. I didn't know about jook joints. I didn't know about how the industrial war complex manipulated the war effort, how it all affected race relations in the South. So I hope readers will be as fascinated as I was with the history, as well as being entertained with the antics of the characters.

You have been traditionally published by two big publishers. Why did you decide to publish directly to Kindle?

I got started publishing on Kindle several years ago. My publisher turned down my fourth book, Amsterdam 2012, which was highly controversial. The fatwa against Salman Rushdie and his publishers was still fresh in their minds. So I published to Kindle and sold 1000 books the first weekend. I suddenly realized how quickly the whole publishing industry was changing.

At one time, agents discouraged writers from publishing on Kindle, thinking it would prevent the book from getting sold to a traditional publisher. But that is no longer true (Fifty Shades of Grey case in point). Traditional publishers now routinely offer contracts to people who have published ebooks. I no longer have patience to wait for my agent to sell a book. That can take six months. Then a year to get published once you sign a contract.

But if you published an ebook, you are selling books in a day. You are getting responses from readers. You can make changes based on those responses, if you want to. You have an open dialogue with your readers. They become part of the writing process, part of the storytelling process, in an almost traditional way—as if they were sitting around a campfire, reacting to your story. I love this. And if the book gets picked up by a DTB publisher, I will have a better book.

Anything else you'd like to add?

Maybe a few words for new writers.

Maybe a few words for new writers.

Don’t wait for an agent. Don’t wait for a publisher. I am a huge advocate for Kindle publishing both for new writers and established writers. You can immediately make some money from your writing, which makes you feel like a writer. You get immediate feedback from readers, which is exciting, improves your work, and makes you realize that, yes, you are writing for an audience. You can make changes on your published material. Traditional publishing is on its way out: it is no longer economically sustainable for publishers; it is too slow to respond to the marketplace; and people are more mobile than ever—they don’t want to lug around a library of books every time they move.

Simply put, Kindle writing is the future of writing: exciting, dynamic, and very likely more profitable for writers. It makes literature suddenly relevant to readers in a new way.

~

Camp Sunshine is available on Amazon Kindle at $3.99. Visit the author on Twitter at @kayakruthie and on Facebook.

Writing a WWII novel Ruth Francisco

Ruth Francisco worked in the film industry for 15 years before selling her first novel Confessions of a Deathmaiden to Warner Books in 2003, followed by Good Morning, Darkness, which was selected by Publishers Weekly as one of the ten best mysteries of 2004, and The Secret Memoirs of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Ruth Francisco worked in the film industry for 15 years before selling her first novel Confessions of a Deathmaiden to Warner Books in 2003, followed by Good Morning, Darkness, which was selected by Publishers Weekly as one of the ten best mysteries of 2004, and The Secret Memoirs of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.She now has nine novels, including the bestseller Amsterdam 2012, published as ebooks. She currently lives in Florida.

Tell us about your novel.

Camp Sunshine is based on the true story of Camp Gordon Johnston, a WWII amphibious training camp on Florida's desolate Gulf coast.

Here, twenty thousand young recruits test themselves to the limit in love and combat; politicos and tycoons offer aid with one eye to profit; women patrol the coast on horseback, looking for German subs; a postmaster's daughter, the only child on base, inspires thousands with her radio broadcasts; and a determined woman bravely holds together her family and the emotional soul of the camp.

But when Commanding Officer, Major Occam Goodwin, discovers a murdered black family deep in the forest, he must dance delicately around military politics, and a race war that threatens the entire war effort. Amid tragedy and betrayal, victory and terror, the fate of the soldiers and their country hangs perilously in the balance, as each endeavors to find his destiny.

What's the most important thing in writing an historical novel as opposed to other fiction?

In a word, research. I did an incredible amount of research for this novel. The vastness of my ignorance when it came to WWII military history was epic, so I had to do epic amounts of reading. I interviewed WWII vets. I visited WWII museums, especially photo archives. I watched WWII Army training films. Camp Gordon Johnston had a newspaper written by the troops, called The Amphibian, and I spent a month reading every issue on microfiche.

Black troops, Camp Gordon JohnstonResearch can surprise you and can lead you in new directions. In my research, I learned of the Double V campaign, which was an African-American civil rights movement intent on integrating the armed services during WWII. I'd never heard of it, and found it fascinating. Suddenly, I found myself with a subplot, which added depth to the novel. It made the story important.

Black troops, Camp Gordon JohnstonResearch can surprise you and can lead you in new directions. In my research, I learned of the Double V campaign, which was an African-American civil rights movement intent on integrating the armed services during WWII. I'd never heard of it, and found it fascinating. Suddenly, I found myself with a subplot, which added depth to the novel. It made the story important. When writing historical fiction, how free can you be with historical fact? It is fiction, after all.

Certain things you can't mess with. Big events. You can't have the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1940. If your characters talk about the song “White Christmas” in 1942, you better be sure that it was written by then. Your readers are smarter than you are. They know more history. They make sport of catching oxymorons.

With lesser known events you can use “artistic license,” especially for little-known historic characters. For instance, I read that two twelve-year-old girls ran a radio station out of Panama City for WWII pilots in training. So I had my postmaster's daughter do the same thing, although the “real” postmaster's daughter was not a DJ. I changed the names of some of the officers who ran the camp because I wanted to involve them in a crime. You can make an historic character a murderer, but you have to be careful. It has to make sense.

In other words, with minor characters, motivations, thoughts, and feelings—let your imagination run wild. Historic events, details—stick to the facts.

Do you have any “tricks” for historical novel writing?

I study photos. I study the clothes and hairstyles. I try to imagine what the people are thinking in the picture, what came before the picture was taken, what came after. When I wrote The Secret Memoirs of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, I wrote almost exclusively from pictures. For instance, the famous picture of Jackie leaving the White House for the inaugural ball—I started with the event, then had her remember all the events that led up to that moment. One picture was an entire chapter.

In this book, I was particularly captured by the photos of WWII training maneuvers, and tried to imagine how an eighteen-year-old boy would react to having bombs explode all around him, waist-high in a swamp, stepping on creepy-crawly creatures. How frightened he must've been. There's a picture of civilian women sewing uniforms for the soldiers, and I get such a sense of dedication and sacrifice—so alien to our culture.

I also read a lot of fiction from the era, which is loads of fun, attentive to jargon, word usage, and attitudes. I listened to a lot of WWII era radio, G.I. Jill, Command Performance, all those great WWII shows. I also studied the pop culture of the era, the songs and dances.

You cannot assume people in another era would behave as you might to a situation.

I recall seeing the 1982 film The Return of Martin Guerre, set in 16th-century France, how tense and wild the people seemed, and it struck me profoundly—if you lived in an environment where you were constantly challenged, constantly on guard for a knife, constantly suspicious, constantly hungry, of course it would make you different. Writers often get caught with their characters having the same values and feelings of contemporary people. But people are different. The lines they will not cross. Their values. Their expectations. You have to use all the resources available to put yourself there. Imagine with all five senses, how things smelled and tasted.

Why did you add a mystery element to an historical novel?

The reason I tend to stick to the mystery/thriller genre, even when I'm writing an historical novel, is that I think it really helps to focus storytelling. A mystery demands a certain pacing. It demands parceling out of clues and information. It forces you to reveal character through action. I feel it really helps me as a writer to have a structured genre.

Where did you get the idea for your WWII story?

When I first drove to the Florida Panhandle from Los Angeles five years ago, I was smitten by the unspoiled beauty of the place. Thousands of Monarch butterflies flitted around my car as I drove down to Alligator Point. The first morning I woke to mullet jumping in the canal and screeching great blue herons. I looked out the window and saw snowy egrets and bald eagles. White squirrels jumping between branches of the pine trees. I had to write about this area.

One day I met a fisherman throwing a cast net into the water and asked him to show me how. We got to talking. When he heard I was a writer, he told me a local story about several dozen soldiers who lost their lives during a WWII training exercise while at Camp Gordon Johnston, how the tragedy was covered up.

Camp Gordon Johnston