Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 116

July 19, 2013

Bits and pieces

A short news round-up for Friday afternoon.

Over at the Historical Novel Society website, I have a new interview with Jessica Brockmole, author of Letters from Skye, in which she talks about traveling to Scotland and sensing its history all around her, using the OED to create authentic voices for her characters, why the fine art of letter writing is the latest rage, and more.

The Langum Charitable Trust has announced the shortlisted titles from the first half of 2013 for the Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction. They are:

- Kent Wascom, The Blood of Heaven (Grove Press) - my review here

- Gary Schanbacher, Crossing Purgatory (Pegasus Books) - the author's guest post here, with a chance for US readers to win a signed copy through 7/22/13

- Christine Wade, Seven Locks (Atria/Simon & Schuster) - my review here

- Philipp Meyer, The Son (Ecco/HarperCollins) - which hasn't appeared on this blog before, but I do have an ARC I'm hoping to get to!

I've begun adding titles to the HNS's list of forthcoming books for 2014. This is going to be a long-term work in progress, but quite a few titles through next April are listed now.

And lastly, for anyone curious about the person writing this blog, my local paper, the Journal-Gazette and Times-Courier, has an interview with me about my site and interests in historical fiction. The piece was written by Beth Heldebrandt, editorial writer at EIU's Booth Library, with photo by library photographer Bev Cruse.

Over at the Historical Novel Society website, I have a new interview with Jessica Brockmole, author of Letters from Skye, in which she talks about traveling to Scotland and sensing its history all around her, using the OED to create authentic voices for her characters, why the fine art of letter writing is the latest rage, and more.

The Langum Charitable Trust has announced the shortlisted titles from the first half of 2013 for the Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction. They are:

- Kent Wascom, The Blood of Heaven (Grove Press) - my review here

- Gary Schanbacher, Crossing Purgatory (Pegasus Books) - the author's guest post here, with a chance for US readers to win a signed copy through 7/22/13

- Christine Wade, Seven Locks (Atria/Simon & Schuster) - my review here

- Philipp Meyer, The Son (Ecco/HarperCollins) - which hasn't appeared on this blog before, but I do have an ARC I'm hoping to get to!

I've begun adding titles to the HNS's list of forthcoming books for 2014. This is going to be a long-term work in progress, but quite a few titles through next April are listed now.

And lastly, for anyone curious about the person writing this blog, my local paper, the Journal-Gazette and Times-Courier, has an interview with me about my site and interests in historical fiction. The piece was written by Beth Heldebrandt, editorial writer at EIU's Booth Library, with photo by library photographer Bev Cruse.

Published on July 19, 2013 13:00

July 16, 2013

Book review: A Treacherous Paradise, by Henning Mankell

In 1904, Hanna Lundmark, a young widow from poverty-stricken northern Sweden, arrives in Lourenço Marques, a coastal town in Portuguese East Africa. Following a series of unexpected events, she becomes the owner of a prosperous brothel of black prostitutes.

In 1904, Hanna Lundmark, a young widow from poverty-stricken northern Sweden, arrives in Lourenço Marques, a coastal town in Portuguese East Africa. Following a series of unexpected events, she becomes the owner of a prosperous brothel of black prostitutes.Her new environment proves difficult to navigate, particularly its blatant racism. Nobody knows what to make of a rich white businesswoman, either.

Black-white relations, evoked with subtle skill and mordant humor, are marked by mutual incomprehension and fear, and Hanna’s attempts at friendliness and generosity toward her employees are met with unnatural silences. When she obeys her conscience and makes a gutsy decision against bigotry, the plot takes turns at once surprising and not.

Mankell, Scandinavian crime fiction’s brightest star, structures his latest around a true story from turn-of-the-century Mozambique. Considerable suspense derives from the tense atmosphere and the fact that neither Hanna nor the reader knows quite what will happen next. The tragic effects of colonialism in this divided land emerge slowly via a succession of shocking reveals.

This powerful work boasts a courageous, well-drawn heroine and makes its points without stridency or didacticism. Since it’s written by Mankell, an author of such high stature, it should get the large audience it deserves.

A Treacherous Paradise was published by Knopf in July ($26.95, 384pp). This starred review appeared in Booklist's June 1st issue.

A few additional comments:

(1) This is a book I'd wanted to read, so I was seriously excited when it showed up in the mail.

(2) I've never read Mankell's Kurt Wallander mysteries so can't make the comparison. The other trade reviews I've seen are positive, but there are some other grumpy reviewers out there who seem upset that this one's not like the Wallander books. Maybe it's just me, but I don't think authors should have to write the same type of book all the time.

(3) Look closely at the cover design. Then look again. Does the woman have her eyes closed, or is she gazing off to her right? It's very cleverly done.

Published on July 16, 2013 16:00

July 15, 2013

Historical novel or novel set in history? A guest post by Gary Schanbacher, author of Crossing Purgatory

Gary Schanbacher is stopping by the blog today with a thought-provoking essay that touches on the nature and definition of historical fiction. His novel Crossing Purgatory, literary fiction set on the Great Plains in the post-Civil War era, was published in June by Pegasus Books (hb, $25.95). There's a giveaway opportunity at the end, too, for American readers. Welcome, Gary!

~

Historical Novel, or Novel Set in History?

Historical Novel, or Novel Set in History?

Gary Schanbacher

When I first began making reading appearances for my novel, Crossing Purgatory, I was initially surprised by questions about the process and challenge of writing historical fiction. In retrospect, the questions were perfectly reasonable since my novel chronicles the journey of a young man who takes to the Santa Fe Trail in the spring of 1858. But, until actually asked the questions, I’d thought of the book as a novel that “happened” to be set in history rather than a historical novel.

Some of you must be thinking: Huh? I’m sure in part the distinction I made was self-deception, pure and simple. I don’t think I’d ever intentionally set out to write historical fiction. I am not a historian by training, and the prospect of researching seemed daunting to the point of writer paralysis. Somewhere in my subconscious I must have found it less intimidating to think in terms of writing about characters in conflict during a particular point in time rather than a “period piece.” My novel had only to be historically “plausible,” rather than factual. Of course, once I became immersed in story, setting, and era, by necessity the research followed. Would my protagonist carry a musket or a rifle? Flintlock or percussion cap? What kind of hat would he wear? How many miles would he travel in a day? And on, and on. But the initial self-deception allowed me to begin writing my novel, and it got me past the point of no return.

On some level, however, the distinction between a historical novel and a novel set in history may be real, and I think it has to do with narrative emphasis. When I finish a book I usually ask myself a few questions. Was I entertained, educated, or both? What about the book might remain with me over time? Do the characters or the events create the lasting impact? Are the characters and events historically factual or fictional, or a mix of both?

For me, the more linked a book is to historically factual characters and events, the more firmly I categorize it as historical fiction. A book dealing with purely fictional characters and imaginary events set during a particular era, I tend to classify as a novel set in history. The difference? Although Crossing Purgatory is intended to evoke a specific time and place, the plot and all major characters are products of my imagination. It would be a very different book if set in 1958 rather than 1858, but probably not different at all if set in 1859 or 1860. Likewise, would it really matter if Lonesome Dove were set in 1877 or 1875 rather than 1876? What matters is that it does a wonderful job of evoking an era and of developing the relationship between two unforgettable men of the old West. In contrast, it would have mattered, very much so, if Stephen Harrigan decided to set the central event of The Gates of the Alamo in 1846 rather than 1836.

All fiction reading is on some level entertainment. Sometimes I feel like a roller coaster ride (think spy thriller), and sometimes I feel like sinking into the Sunday Times crossword puzzle (think Moby Dick). Similarly, at times I enjoy reading fictional recreation of actual events lived by actual characters (what I call historical fiction), and at other times I enjoy letting fictional characters roam freely, endure imaginary challenges and interactions that evoke a sense of time and place unconstrained by historical event (novel set in history).

~

Gary Schanbacher’s short story collection, Migration Patterns, received a PEN/Hemingway Honorable Mention for distinguished first works of fiction and won the Colorado Book Award, The High Plains First Book Award, and the Eric Hoffer General Fiction Award. Publishers Weekly calls his new novel, Crossing Purgatory, “a visceral and triumphant saga of the Old West,” and in a starred review Booklist refers to Schanbacher as “a gifted writer whose prose is always elegant, whether describing the land, a winter storm, or the inner life of his characters.” Visit his website at http://garyschanbacher.com.

Gary Schanbacher’s short story collection, Migration Patterns, received a PEN/Hemingway Honorable Mention for distinguished first works of fiction and won the Colorado Book Award, The High Plains First Book Award, and the Eric Hoffer General Fiction Award. Publishers Weekly calls his new novel, Crossing Purgatory, “a visceral and triumphant saga of the Old West,” and in a starred review Booklist refers to Schanbacher as “a gifted writer whose prose is always elegant, whether describing the land, a winter storm, or the inner life of his characters.” Visit his website at http://garyschanbacher.com.

For your chance to win a signed copy of Crossing Purgatory, thanks to the generosity of the author, please fill out the form below. US readers only; deadline Monday, July 22nd.

Loading...

~

Historical Novel, or Novel Set in History?

Historical Novel, or Novel Set in History?Gary Schanbacher

When I first began making reading appearances for my novel, Crossing Purgatory, I was initially surprised by questions about the process and challenge of writing historical fiction. In retrospect, the questions were perfectly reasonable since my novel chronicles the journey of a young man who takes to the Santa Fe Trail in the spring of 1858. But, until actually asked the questions, I’d thought of the book as a novel that “happened” to be set in history rather than a historical novel.

Some of you must be thinking: Huh? I’m sure in part the distinction I made was self-deception, pure and simple. I don’t think I’d ever intentionally set out to write historical fiction. I am not a historian by training, and the prospect of researching seemed daunting to the point of writer paralysis. Somewhere in my subconscious I must have found it less intimidating to think in terms of writing about characters in conflict during a particular point in time rather than a “period piece.” My novel had only to be historically “plausible,” rather than factual. Of course, once I became immersed in story, setting, and era, by necessity the research followed. Would my protagonist carry a musket or a rifle? Flintlock or percussion cap? What kind of hat would he wear? How many miles would he travel in a day? And on, and on. But the initial self-deception allowed me to begin writing my novel, and it got me past the point of no return.

On some level, however, the distinction between a historical novel and a novel set in history may be real, and I think it has to do with narrative emphasis. When I finish a book I usually ask myself a few questions. Was I entertained, educated, or both? What about the book might remain with me over time? Do the characters or the events create the lasting impact? Are the characters and events historically factual or fictional, or a mix of both?

For me, the more linked a book is to historically factual characters and events, the more firmly I categorize it as historical fiction. A book dealing with purely fictional characters and imaginary events set during a particular era, I tend to classify as a novel set in history. The difference? Although Crossing Purgatory is intended to evoke a specific time and place, the plot and all major characters are products of my imagination. It would be a very different book if set in 1958 rather than 1858, but probably not different at all if set in 1859 or 1860. Likewise, would it really matter if Lonesome Dove were set in 1877 or 1875 rather than 1876? What matters is that it does a wonderful job of evoking an era and of developing the relationship between two unforgettable men of the old West. In contrast, it would have mattered, very much so, if Stephen Harrigan decided to set the central event of The Gates of the Alamo in 1846 rather than 1836.

All fiction reading is on some level entertainment. Sometimes I feel like a roller coaster ride (think spy thriller), and sometimes I feel like sinking into the Sunday Times crossword puzzle (think Moby Dick). Similarly, at times I enjoy reading fictional recreation of actual events lived by actual characters (what I call historical fiction), and at other times I enjoy letting fictional characters roam freely, endure imaginary challenges and interactions that evoke a sense of time and place unconstrained by historical event (novel set in history).

~

Gary Schanbacher’s short story collection, Migration Patterns, received a PEN/Hemingway Honorable Mention for distinguished first works of fiction and won the Colorado Book Award, The High Plains First Book Award, and the Eric Hoffer General Fiction Award. Publishers Weekly calls his new novel, Crossing Purgatory, “a visceral and triumphant saga of the Old West,” and in a starred review Booklist refers to Schanbacher as “a gifted writer whose prose is always elegant, whether describing the land, a winter storm, or the inner life of his characters.” Visit his website at http://garyschanbacher.com.

Gary Schanbacher’s short story collection, Migration Patterns, received a PEN/Hemingway Honorable Mention for distinguished first works of fiction and won the Colorado Book Award, The High Plains First Book Award, and the Eric Hoffer General Fiction Award. Publishers Weekly calls his new novel, Crossing Purgatory, “a visceral and triumphant saga of the Old West,” and in a starred review Booklist refers to Schanbacher as “a gifted writer whose prose is always elegant, whether describing the land, a winter storm, or the inner life of his characters.” Visit his website at http://garyschanbacher.com.For your chance to win a signed copy of Crossing Purgatory, thanks to the generosity of the author, please fill out the form below. US readers only; deadline Monday, July 22nd.

Loading...

Published on July 15, 2013 04:00

July 12, 2013

An interview with Gillian Bagwell, author of Venus in Winter - plus giveaway

Today I have the pleasure of hosting historical novelist Gillian Bagwell for a Q&A. Venus in Winter, her third novel, spans over three decades in the life of Bess of Hardwick, who rose to become one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in Elizabethan England via her successive marriages to four men of progressively higher status. In Gillian's lively interpretation, Bess is an immensely likeable young woman who gradually becomes accustomed to the customs and dangerous political realities of life at the court of Henry VIII and his successors.

Today I have the pleasure of hosting historical novelist Gillian Bagwell for a Q&A. Venus in Winter, her third novel, spans over three decades in the life of Bess of Hardwick, who rose to become one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in Elizabethan England via her successive marriages to four men of progressively higher status. In Gillian's lively interpretation, Bess is an immensely likeable young woman who gradually becomes accustomed to the customs and dangerous political realities of life at the court of Henry VIII and his successors. Please read to the end, as we have a giveaway opportunity. Two copies are up for grabs; the publisher will send out a copy to a US reader, while I'll send a 2nd copy out to a randomly selected international reader.

~

Do you remember where you first came across Bess of Hardwick’s story? What made her such an irresistible subject?

I don't remember when I first heard of Bess of Hardwick. I had come across references to her here and there in my reading about 16th-century England, and she sounded interesting but I didn't know much about her.

My second novel, The September Queen, was the first fictional account of the story of Jane Lane, who helped the young Charles II escape after the Battle of Worcester, and when I began thinking about what to write next, I hoped to find another subject who hadn't been written about over and over. Queens and mistresses tend to be the historical women that people know about, but finding Jane's story made me sure there must be more fascinating women out there.

Bess of Hardwick, ca. 1550sI recalled Bess's name, and a very little research made me excited about telling her story. She knew just about everyone of any importance in England in the second half of the 16th century and was involved in or an observer of many historic events.

Bess of Hardwick, ca. 1550sI recalled Bess's name, and a very little research made me excited about telling her story. She knew just about everyone of any importance in England in the second half of the 16th century and was involved in or an observer of many historic events. Venus in Winter follows Bess over three marriages, stopping right before her fourth, and spans about 40 years. Were there segments of her life that weren’t as well documented, and which were more challenging to research or write about?

As was the case with my first two heroines, Nell Gwynn and Jane Lane, not much specific is known about Bess's early years. David Durant's biography begins with Bess's second marriage, when she was nineteen. Maud Stepney Rawlins's Bess of Hardwick and Her Circle dispenses with her first two marriages and the first thirty years of her life in ten pages, and another twelve pages takes Bess to the age of thirty-seven and the death of her third husband. Even Bess's most recent biography, Mary Lovell's Bess of Hardwick: Empire Builder, takes only two hundred out of almost five hundred pages to bring Bess to the age of forty in 1567, when my book ends.

I used what facts were known about Bess's early life: the names and approximate ages of her parents and siblings; the fact that she spent her childhood at what was then Hardwick Manor; her father's death when she was a baby and the subsequent taking over of the property by the Court of Wards; her stepfather's imprisonment for debt; her becoming a lady in waiting to Lady Zouche around the age of twelve; her marriage to young Robert Barlow, who was also in the Zouche household; and her joining the household of Frances Grey after her she was widowed at the age of sixteen.

Based on those bits of information, I had to conjecture quite a lot about what she might have experienced. Coincidentally, Henry VIII signed the contract to marry Anne of Cleves on October 4, 1539, which was likely Bess's twelfth birthday, according to Mary Lovell. Bess probably entered Lady Zouche's service around that time, and as both Lady Zouche and her husband had served Anne Boleyn and were known at court, and Sir George became a gentleman pensioner to Henry VIII in about 1540, it didn't seem unreasonable to send Bess to London with them so she could observe Henry VIII's marriages to Anne of Cleves and Catherine Howard.

Possibly Anne Gainsford,

Possibly Anne Gainsford,Lady Zouche

(Hans Holbein the Younger)Bess's friend Elisabeth Brooke, who later married William Parr and became the Marchioness of Northampton, was first noted at court as a maid of honor to Catherine Howard. I don't know when they met, but to avoid inventing a fictional character who then disappears, I put Elisabeth Brooke into Lady Zouche's household, creating a plausible bridge for Bess's acquaintance with Catherine Howard, who arrived at court as a maid of honor to Anne of Cleves and was probably only a couple of years older than Bess.

Much more is known about Bess after the time of her second marriage, to Sir William Cavendish, who was about twenty years older than she was and already quite prominent when he married her.

The dialogue in Venus in Winter is clear and understandable to the modern ear, yet the word choices and syntax also give a good sense of the period. Does your experience in the theatre influence how you craft your characters’ speech?

Yes, I've found that my years in theatre as an actress and director are very helpful in writing historical dialogue. I've read so much material from the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries that the language sounds natural to me. And while I don't necessarily read dialogue aloud while writing, I do kind of hear it my head and have an instinctive sense of whether I could say the lines and make them believeble. This helps me avoid language that's too contemporary or faux-period, I hope!

I think that judicious use of period words and expressions and syntax can give a good flavor of the period without being distracting. When I was writing The Darling Strumpet, I had a great time using period slang, and contrasting Nell's speech with that of more upper class people. I would have liked to do another draft of Venus just to incorporate a little more flavor of the period in the dialogue, but I ran out of time.

I think that judicious use of period words and expressions and syntax can give a good flavor of the period without being distracting. When I was writing The Darling Strumpet, I had a great time using period slang, and contrasting Nell's speech with that of more upper class people. I would have liked to do another draft of Venus just to incorporate a little more flavor of the period in the dialogue, but I ran out of time. Bess divides her time between life at court and her homes in the countryside (I particularly liked the descriptions of the natural beauty around Chatsworth in Derbyshire). Did any locales stand out as more memorable or enjoyable to write about – or to visit in person?

Unfortunately, I wasn't able to make a trip to England for this book. I've spent a lot of time in London and some time traveling around other parts of the country, and had to rely on those experiences and long-distance research. Fortunately, there's so much information, including historical images and maps and Google Maps and Google Earth, that it's possible to learn a lot without leaving home.

Of course, very little of 16th-century London remains except the layout of the streets. One of Bess's houses was in Newgate Street, which I actually know quite well, as I regularly walked from the Bank underground station along Cheapside and Newgate Street to near Smithfield when my mother was in St. Bartholomew's Hospital. (The hospital existed in Bess's time, but of course in a much different form than now.) Fellow historical fiction author J.D. Davies was kind enough to take loads of pictures when he visited Hardwick Hall and send them to me, and that helped with writing the prologue and epilogue.

Chatsworth House, Derbyshire

Chatsworth House, DerbyshireBess and her family spend a fair bit of time occupied by money problems, from her childhood woes with her stepfather in debtor’s prison to disputes over her dower rights from her first marriage, and more. You don’t often see issues related to finance and legal proceedings in Tudor-era fiction, even though it’s important for understanding day-to-day life at the time. Everything was very clearly explained, but how complex were these issues to research and untangle?

I'm so glad you found the events clear, because they were kind of a bear to understand and put in the story without lots of explanation! Mary Lovell's biography of Bess explains these issues pretty well, especially the situation with the Court of Wards and its control of estates inherited by minor children. I did have to do some digging to figure out where Bess's early suit would have been held and who would have presided over it, and then make some conjecture about what the specifics of her experience would have been like. Bess was so astute about money and so businesslike, that I thought it was important to get into some specifics that showed her developing those abilities.

She went to court several times in her life, which was very unusual for a woman. I think her second husband, Sir William Cavendish, who was a very able administrator and very well connected, probably taught her a lot. Someone must have helped her with that first suit about her dower rights when she was only sixteen or seventeen, and in the novel, I have Sir William be that person, as it's in keeping with what I know about him and a good opportunity for them to get to know each other.

Frances Grey, Lady Dorset, is one of the more intriguing secondary characters. She proves herself a good and generous friend to Bess, but she doesn’t show the same kindness to her oldest daughter, Jane. How did you develop Frances’ character and her relationship with Jane?

Frances Grey (nee Brandon)I relied on biographies of Bess and Jane as well as other books about the period and the important players of the time in writing Frances's character. Bess's second marriage took place at Bradgate Park, the Grey family home, and Frances gave Bess jewelry and probably introduced her to her second husband, so it's clear that she must have had some regard and affection for Bess.

Frances Grey (nee Brandon)I relied on biographies of Bess and Jane as well as other books about the period and the important players of the time in writing Frances's character. Bess's second marriage took place at Bradgate Park, the Grey family home, and Frances gave Bess jewelry and probably introduced her to her second husband, so it's clear that she must have had some regard and affection for Bess. There seems to be a fair amount of evidence that Jane Grey's parents were extremely ambitious for Jane, even at the expense of her own desires and happiness, and their ambition ultimately cost her life.

Jane told her schoolmaster Roger Ascham that she couldn't seem to please her parents no matter what she did, and that they "cruelly threatened" her, "sometimes with pinches, nips, and bobs [smacks]" so that she thought herself "in hell" until she could go to her tutor John Aylmer. Some of her biographers seem to doubt that she was really badly treated or that Frances was as bad as she sounds, but those words are pretty convincing to me, and I had her speak them to Bess, who is grateful for Frances's kindness to her but heartbroken that Jane, who she loves, is so little valued and so unhappy.

The heroines of your three historicals have all been strong women who associate closely with royalty (in different ways) although they aren’t royal themselves. Why do you enjoy writing from this viewpoint?

Part of the reason is that I have sought out characters that haven't been written about so much that everyone knows about them and it's hard to make their stories fresh. At the same time, women at or near the top of society are the ones whose lives are best documented. Undoubtedly there were many middle class and working class women who led interesting lives, but didn't leave much of a record.

Women who were associated with royalty were also in a position to participate in or observe compelling and important historical events, and I think readers might relate more to their perspective as relative outsiders than they do to the thoughts of a queen. And of course female lead characters seem to work better than men, or at least that's what my agent says, so that eliminates the kings and princes themselves, and leaves the women around them.

Charles II and Jane Lane, riding to Bristol (Isaac Fuller)

Charles II and Jane Lane, riding to Bristol (Isaac Fuller)You’ve moved a little further back in time with this book, from the 17th century to the 16th,, and from the Stuarts to the Tudors. Was this a fairly easy shift for you to make?

Yes and no. I learned about Jane Lane in the course of researching The Darling Strumpet, and had Charles II tell Nell Gwynn a little about his escape after the Battle of Worcester, but there was no way to do that story justice. When my agent was getting ready to submit Darling Strumpet, she asked me to come up with some ideas for a second book, and that was one of them.

I thought that since I knew a lot about 17th-century England already and that even some of the same characters would appear in both books, it would be easy to write The September Queen. I was wrong! There's a big difference between knowing a fair amount of the general history, and saying, okay, it's July 30, 1651--what specifically is happening on this day? How does it affect my character and what is she doing?

Also, writing The September Queen involved learning a lot about the English Civil Wars, all the efforts to restore Charles II to the throne before the actual Restoration, and long stretches of time in the courts of Paris and The Hague, with lots of people I knew nothing about. Similarly, I know a fair amount about the 16th century generally, partly as a result of my long interest in Shakespeare and many years performing at Renaissance Faires, but Bess of Hardwick lived through periods of incredible turmoil, and to tell her story I had to learn a lot of very specific information about the reigns of each of the Tudor monarchs, the people around them, and the ins and outs of very complicated events involving politics, changes in religion, and numerous changes of regime.

Can you reveal anything about what you might be working on next?

I don't have a contract yet for what I hope to write next, but I can say it's somewhat of a departure from my first three books, though it involves historical events and real people. And someday I'd like to write a novel about Bess's second forty years!

~

Gillian Bagwell's novel about Bess of Hardwick, Venus in Winter, was released on July 2 by Berkley ($16.00, pb, 448pp).

Gillian Bagwell's novel about Bess of Hardwick, Venus in Winter, was released on July 2 by Berkley ($16.00, pb, 448pp).To find links to Gillian's other posts related to the book, please follow her on Twitter @gillianbagwell, on Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/gillianbagwell, or visit her website, www.gillianbagwell.com.

To enter the giveaway for a copy of Venus in Winter, please fill out the following form. Two copies are up for grabs: one for the US and one international. Deadline Friday, July 19th. Best of luck!

>Loading...

Published on July 12, 2013 05:00

July 9, 2013

Judging books by their setting: The case of the literary Western

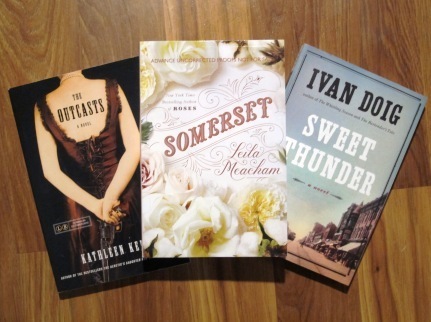

Here are three ARCs I picked up in the ALA exhibit hall last weekend. First up is Kathleen Kent's The Outcasts (Little, Brown, Oct), a women's adventure story set in Texas after the Civil War. Next is Leila Meacham's Somerset (Grand Central, Nov), a 600-page multigenerational epic spanning 150 years of southern and western history and the long-awaited prequel to the author's bestselling Roses. Finally we have Ivan Doig's Sweet Thunder (Riverhead, Aug), about a newspaperman's battle for justice for local miners in 1920s Montana.

All three authors have a large and eager following, based on their previous successes. These three novels have been highly anticipated (and not just by me!). And all three are set in the late 19th to early 20th-century West.

Some readers naturally gravitate towards Western fiction, while others may need quite a bit more persuading to try it – or an added hook. Such as a famous name or event, for example, or the promise of a new installment in a well-loved series. The American West isn't perceived to be glamorous, especially compared to fiction set in royal courts or grand English manor houses, and Western novels are often dismissed as overfamiliar or formulaic. As a book review editor, I admit I often have difficulty finding readers willing to consider them.

I dislike stereotypes in any type of fiction, Westerns included; that said, the exploration and settlement of the West are an integral part of American history that I enjoy reading and learning more about. These novels can offer exciting stories of adventure, independence, and discovery. In addition, I tend to read for plot, language, and character as much as setting, and I've seen how a talented storyteller can draw me into a novel and make me care about what happens regardless of where it takes place. Note the cover design of The Outcasts, too; it's a clever way to catch the attention of readers who like other novels about strong women in history.

While I was contemplating this topic as the subject of a blog post, the July issue of NoveList's RA News arrived in my inbox. It has a few additional articles that focus on Westerns: both the stereotypes that surround them and the promises they offer. Reading lists are included, too.

Are you looking forward to reading any of the three novels shown above? Do you have any other thoughts about Western settings you'd like to share?

Published on July 09, 2013 17:04

July 5, 2013

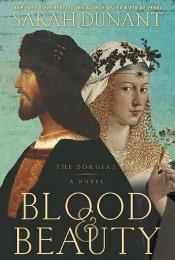

Review of Blood & Beauty: The Borgias, by Sarah Dunant

Sarah Dunant has written three acclaimed novels of Renaissance Italy in which she consciously narrowed her focus to the long-concealed stories of ordinary women on the margins rather than following what she termed the “historical celebrity version of life.” Now, in a noteworthy switch, we’re presented with Blood & Beauty, which centers on perhaps the most grasping and notorious celebrities of the era. The Borgia name instantly evokes images of glorious wealth and even more glorious power, corruption, poison, and incest.

Sarah Dunant has written three acclaimed novels of Renaissance Italy in which she consciously narrowed her focus to the long-concealed stories of ordinary women on the margins rather than following what she termed the “historical celebrity version of life.” Now, in a noteworthy switch, we’re presented with Blood & Beauty, which centers on perhaps the most grasping and notorious celebrities of the era. The Borgia name instantly evokes images of glorious wealth and even more glorious power, corruption, poison, and incest. So we might approach this current book believing it to be a significant departure. In addition to climbing on a new bandwagon by fictionalizing famous real-life leaders, her canvas has broadened. It encompasses the names many readers know well, first and foremost the ruthlessly ambitious Spanish-born Rodrigo Borgia (Pope Alexander VI), patriarch not only to his beloved illegitimate children but to Catholic believers worldwide.

But looking beyond them, it also presents an overarching portrait of the European political scene, including the changing alliances and deadly jockeying for supremacy among Rome, Naples, Milan, France, and Spain. This is the grand sweep of history, moving from the epic to the personal and back.

As Alexander uses his progeny as pawns to further his dynastic goals, they clash with the rulers of other Italian city-states and with one another. Their interactions are what push the plot forward. They are Juan, the eldest, his father’s loyal and self-important favorite; Cesare, charismatic, astute, callously ambitious, and overprotective of the beautiful sister he adores too much; Jofré, less complex and more childlike than his older siblings; and young Lucrezia, an ardently devout romantic who, over the ten-year span of the novel, becomes torn between her family’s orders and her own desires.

An unlikely cardinal, with his very worldly appetites, Cesare follows most closely in his father’s shoes. He has a lot of on-page time, with not much change to his personality. His presence gets somewhat wearing after a while, but the conclusion proves he has some surprises up his sleeve. There are no caricatures here, and he and his siblings’ personas reflect contemporary research much more than their infamous legends.

The novel uses a true omniscient viewpoint, a technique difficult to master – and for the most part it succeeds. Dunant’s perspective swoops from person to person and place to place, allowing insight into major as well as minor characters, from papal messenger Pedro Calderón to Ludovico Sforza, the Borgias’ Milanese foe, to the physician treating Cesare for the “French disease.” Every sentence has her sharp intelligence behind it and showcases her trademark dedication to detail.

The novel uses a true omniscient viewpoint, a technique difficult to master – and for the most part it succeeds. Dunant’s perspective swoops from person to person and place to place, allowing insight into major as well as minor characters, from papal messenger Pedro Calderón to Ludovico Sforza, the Borgias’ Milanese foe, to the physician treating Cesare for the “French disease.” Every sentence has her sharp intelligence behind it and showcases her trademark dedication to detail. There are times, though, when she draws far back from the main plotlines to speak to readers about the historical context. While these informative segments are narrated with flair and drama, they can be dense, and they also break up the reading experience. At these times, the story feels less a character-driven work than a history-driven one.

Emerging gradually from amidst the multiple story strands is a shining thread of feminine empowerment. This isn’t meant in the modern sense, but in the more subtle, quietly crafty, behind-the-scenes ways open to women of the era. Alexander and Cesare may hold the heaviest reins of power in Blood & Beauty, but its women are its moral center. Lucrezia’s transformation from unguarded innocent to shrewd game-player is the novel’s most compelling aspect. She, her practical and straight-talking mother Vannozza dei Catanei, and tough warrior-woman Caterina Sforza are brilliant characters whose survival instincts we can’t help but admire. Although each suffers significant losses, that doesn’t make their triumphs any less sweet.

As always, Dunant is perfectly at home in her setting. The atmosphere is decadent and dangerous in equal measure, with descriptions emphasizing the tightly knotted themes of art, politics, and faith. “Most men need to be overwhelmed in order to appreciate the divine. That is Rome’s job,” observes Alexander, in one of many classic lines, while gazing at the awe-inspiring splendor of the Sistine Chapel.

From different angles, all of the novels in her earlier trilogy (The Birth of Venus, In the Company of the Courtesan, and Sacred Hearts) spoke of the influential power of the family during the Italian Renaissance. This latest work is no different; the Borgias simply bring this motif unavoidably front and center. Complex, perceptive, and erudite, and with magnificent, strong women: this is what we’ve come to expect from Dunant. Those who reveled in all the details of this colorful historical era, too, will find even more of it to enjoy here. On the whole, maybe Blood & Beauty isn’t such a huge departure for her after all.

~

Blood & Beauty: The Borgias will be published on July 16th by Random House in the US ($27.00, hb, 528pp). It was published in the UK by Virago (£16.99, hb) on July 2nd. Thanks to the publisher and Goodreads for an ARC of this book; this was a First Reads win.

Published on July 05, 2013 10:29

June 26, 2013

Back from the Historical Novel Society conference

Just noticed this is my 800th post!

I returned late Tuesday night from the 5th North American HNS conference in St. Petersburg, Florida. The weather was sunny and beautiful (if very muggy) every day, the Vinoy Renaissance hotel was absolutely gorgeous, my room was large and quiet, the hotel staff were attentive and helpful, and the panels I attended were all professionally run and informative. My sparkly sandals even cooperated; I made it through without bandaids. This was my first time there as a regular attendee rather than an organizer (many people came up to me so say how relaxed I looked!) so I had time to catch up with old friends and meet up with many others I'd only communicated with online. These conferences really are all about the people, after all -- making connections with fellow HF nerds that endure long after we're all back home.

Because I find it hard to keep up with online stuff while the conference is on, I didn't tweet or FB very much and also didn't take many photos (the one above is a scene of the ocean inlet across the street from the Vinoy). For a great compilation of photos that also tells a story of conference happenings, let me refer you over to the Storify site put together by Audra of Unabridged Chick.

I leave tomorrow for ALA in Chicago and am working the late shift tonight, so things are kind of crazy around here, but I thought I'd post some info on the panels I attended and some other highlights of the conference:

Anne Perry's inspirational Friday night guest of honor speech emphasized the role of story in historical fiction and the need to make these works emotionally resonant. And she spoke for over half an hour without any notes! Wow. A wonderful way to start off the event.Early on Saturday morning, I attended the first agent/editor panel session, which turned out to be a Q&A for aspiring writers. This may seem an unusual choice for someone like me who doesn't write fiction, but I like hearing what things are like on the other side of the table.Advice from agent Stephanie Cabot: Each book in a series should stand alone, and in the case of a trilogy, don't end book 1 with a cliffhanger. Agent Helen Heller mentioned "the Tudors have been overfished" although this depends on the quality of the work in question; she also advised authors writing query letters not to start with a provocative question about the plot, but simply to say what the book is about and about themselves. Agent Diana Fox said that trends can make a novel easier to sell, but the writing is what matters most. From agent Greg Johnson: a series can benefit both authors and readers and save authors time in creating backstory. Small press editor Jean Huets focuses on American settings and is looking for new voices in this area. This was the only panel where I took notes, so this is rather long!Susan Spann ably moderated a panel of historical mystery writers with settings as diverse as 19th and 20th-c South America (Annamaria Alfieri), Victorian England (Anne Perry), 1st-c Jerusalem (Frederick Ramsay), and Judith Rock (17th-c France). Susan's debut, Claws of the Cat, comes out next month and features a ninja detective and a Jesuit solving mysteries in 16th-c Japan. I loved the variety showcased here.Christopher (C.W.) Gortner's lunch speech, focusing on community and how HNS had helped him along his publishing journey, set the perfect tone for the conference."To Trump or Trumpet the History Police" - Will historical purists come out to get you if you fudge the facts? The conclusion was: sometimes they will! The authors (Stephanie Cowell, Christy English, Margaret George, Anne Easter Smith, with CW Gortner moderating) had a lively discussion/debate about historical accuracy vs. the importance of creating a good story. Each has condensed a timeline to some degree or eliminated unneeded characters for the sake of the story they wanted to tell."Virtual Salon: The Historical Fiction Blog" - a great intro to the many purposes for a blog in the historical fiction world, whether they're written by authors or reviewers/readers. There was a lot of positive buzz surrounding this panel. Speakers were Deborah Swift, Amy Bruno, Heather Rieseck, and Heather Webb, moderated by Julianne Douglas.The "Off the Beaten Path" workshop with bloggers & authors Julie Rose, Heather Domin, Audra Friend, and Andrea Connell was a treat for readers (like me) who seek out less common settings and types of characters in their historical novels. Check out their page of info with publishing & reviewing trends as well as their lengthy reading list.Gillian Bagwell did a smashing job in her role as Joan, Lady Rivers emceeing the costume pageant, and Teralyn Pilgrim, as a pregnant vestal virgin, was an obvious choice for winning "most authentic historical costume." I hope her on-stage interview with Lady Rivers was taped! I was very tired by that point and didn't stay for most of the late-night sex scene readings, but was entertained by Margaret George's reading from her Autobiography of Henry VIII.On Sunday morning I went to just two sessions, one author presentation and another with "cold reads" of unpublished manuscripts. In the former, Susanna Kearsley gave advice on how to flesh out historical characters' backstories and discover new connections between them using genealogical research. As a sidenote, I last saw Susanna at the last ever BookExpo Canada in 2008, when I was probably the only American in attendance. After she signed a copy of The Winter Sea for me, I asked her if her new books would be published in the US at some point. At the time, US publishers felt the stories were "too quiet" and weren't interested. Now her novels, out from Sourcebooks, are bestsellers, which is great. Goes to show that sometimes the industry has no clue.I wish I'd gotten to more sessions; choosing was very difficult! What I valued even more were the many conversations I'd had with other attendees in the lobby, at the receptions, and over meals. Shout-outs to the late Thursday night dinner crowd at Fresco's on the waterfront; my library school buddy Vicki (we graduated almost 20 years ago); all the HNR reviewers and HNS members I chatted with; the blogger lunch group on Sunday with Audra, Heather, and Meg; and the fabulous members and organizers of the new Great Lakes HNS Chapter. The gathering ended on a high note with a group excursion (Alison, Jessica, Marie, Meg, and myself) to a robot-themed sushi place on Sunday night and drinks out on the veranda. Later we watched as a bus of VIP types (later revealed to be a certain Toronto baseball team) climb out of their bus and walk into the hotel. I have no photos; even if I'd wanted them, the hotel had signs up about that...

And so another HNS conference has wrapped up. Congrats to Vanitha Sankaran and the rest of the board of directors for a job well done. I'm already looking forward to London in September 2014.

Published on June 26, 2013 13:00

June 16, 2013

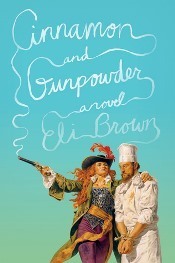

Book review: Cinnamon and Gunpowder by Eli Brown

The premise of Eli Brown's second novel grabbed my attention; it promised an entertaining mashup of pirate action and haute cuisine, with an assortment of quirky characters thrown in for good measure. A foodie adventure at sea. Certainly not anything I'd read before. Experienced chefs know that the mingling of contrasting flavors can result in the most delicious dishes, and such is the case with the aptly-titled Cinnamon and Gunpowder.

The premise of Eli Brown's second novel grabbed my attention; it promised an entertaining mashup of pirate action and haute cuisine, with an assortment of quirky characters thrown in for good measure. A foodie adventure at sea. Certainly not anything I'd read before. Experienced chefs know that the mingling of contrasting flavors can result in the most delicious dishes, and such is the case with the aptly-titled Cinnamon and Gunpowder.(And once you read it, you'll understand why recipe metaphors are hard to resist.)

Owen Wedgwood's culinary skills are famed throughout England. A "cook for gentlemen and ladies of highest station," he works for Lord Ramsey, chairman of the Pendleton Trading Company, a shipping firm pursuing the tea trade in distant India and China.

One fateful afternoon in 1819, after preparing a mouthwatering feast for Ramsey and his colleagues, he sees his employer murdered before his eyes. The perpetrator is Mad Hannah Mabbot, the flame-haired pirate queen whose fearsome deeds have made her a notorious name on the high seas.

Captain Mabbot kidnaps our narrator, installs him in grimy quarters aboard the Flying Rose, and presents her demands. He must prepare a gourmet meal for her every Sunday, never repeating the same dish twice – or else. The ship's pantry hold is pretty meager, so while Mabbot and her loyal crew head out in pursuit of the thieving Brass Fox while being chased by the dangerous privateer Laroche, "Wedge" is forced to improvise his creations, all the while trying to devise his escape.

Needless to say, Wedge is miserable, and he notes all his thoughts in a logbook he conceals in his cabin. "I'll say here that I do hate ships," he writes. "When conversations occasionally turn nautical, I have found that there are always herbs that need drying or cheeses to press."

Fortunately, he proves up to the task. The dishes he prepares are drool-worthy: potato-breaded whitefish in shrimp sauce over saffron rice and rum-poached figs stuffed with blue cheese, for example. (Well, for the most part; I regretted the fate of the homing pigeons.) The gastronomic delicacies, combined with Wedge's dryly humorous, eloquently written journal entries, make the novel well worth diving into.

The highlight, though, is Captain Mabbot herself. She's a spectacular character. Her methods are ruthless and brutal, yes, but as Wedge discovers, to his great surprise, she's an intelligent conversationalist with deeply felt reasons behind her actions.

The secondary characters are a colorful lot, from the burly first lieutenant Mr. Apples, an avid knitter, to Joshua, the mute cabin boy who becomes Wedge's very capable assistant. The swashbuckling plot is swiftly paced and firmly situated in its backdrop of British imperialism, with readers seeing each spoke of the "tea-opium-slave wheel" as it turns.

The initial concept delivers, but the best part is that the reading experience offers much more than that. Comedic, thoughtful, and touchingly romantic all at once, Cinnamon and Gunpowder is a pirate adventure like no other. Even the most stubborn landlubbers will want to climb on board.

Cinnamon and Gunpowder was published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in June at $26.00/$30.00 in Canada (hardcover, 318pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me a copy at my request.

Published on June 16, 2013 05:00

June 8, 2013

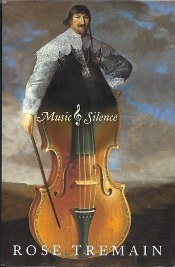

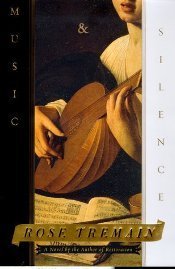

For the TBR Pile Challenge: Rose Tremain, Music & Silence

UK edition (1999)Entry in the 2013 TBR Pile Challenge: #3 out of 12

UK edition (1999)Entry in the 2013 TBR Pile Challenge: #3 out of 12Years on TBR: 13 or so

Edition owned: London: Chatto & Windus, 1999 (hb, 454pp)

Back in February, I declared my intention to review one book from the TBR Pile Challenge each month during 2013. Obviously, this hasn't happened, but I'm doing my best to catch up!

As implied by the title, Music and Silence is a novel of contrasts. Tremain uses delicate, almost ethereal language to evoke her themes of intense passion, obsession, and longing. Heated affairs play out during the cold, desolate winters of northern Europe, and the gentle heroine vies against the malign forces at court and in her own family.

So many readers have told me that this is one of their favorite novels, so I turned the first page prepared to be impressed, but with slight trepidation (would I agree?). I quickly learned that Music and Silence demands a quiet frame of mind. It's not tolerant of distractions, and if you try to read it while other things are going on in the background, you'll need to tune them out first. It took me a few chapters to realize this.

The royal court of 1620s-30s Denmark isn't one that figures in other historical novels I've heard of, and Tremain has so thoroughly claimed this setting and its major players for her own that no other author is likely to try.

US edition (2000)It opens in 1629, as English lutenist Peter Claire arrives at the Danish court to take up a post in Christian IV's royal orchestra. After coming to terms with the king's odd demand that the musicians play in a frigid cellar, so that the sound will waft up mysteriously to the audience on the upper level, he contends with Christian's other expectations (he reminds the king of a long-dead childhood friend). He also forms an attachment to Emilia Tilsen, one of the ladies of Kirsten Munk, the king's morganatic second wife.

US edition (2000)It opens in 1629, as English lutenist Peter Claire arrives at the Danish court to take up a post in Christian IV's royal orchestra. After coming to terms with the king's odd demand that the musicians play in a frigid cellar, so that the sound will waft up mysteriously to the audience on the upper level, he contends with Christian's other expectations (he reminds the king of a long-dead childhood friend). He also forms an attachment to Emilia Tilsen, one of the ladies of Kirsten Munk, the king's morganatic second wife.The progression of Peter and Emilia's tender romance forms the novel's centerpiece, but it also encompasses many other stories about love: Emilia's close bond with her young brother Marcus, Christian's pursuit of the adulterous Kirsten, and dowager queen Sofie's love for her money. There's also a subplot about Peter's plain sister Charlotte, back in England, and the fiancé nobody expected her to have; I found this story especially moving.

None of these, however, is as compelling to read about as Kirsten's love for herself.

Kirsten Munk by Jacob van DoordtKirsten writes journal entries in sections labeled "Kirsten: From Her Private Papers," and Tremain's depiction of this character is a command performance. Kirsten is lustful, deceitful, and completely self-absorbed. She thinks endlessly about her bedroom acrobatics with her lover, a German count named Otto Ludwig; she hates children; and she cares not at all for her husband.

Kirsten Munk by Jacob van DoordtKirsten writes journal entries in sections labeled "Kirsten: From Her Private Papers," and Tremain's depiction of this character is a command performance. Kirsten is lustful, deceitful, and completely self-absorbed. She thinks endlessly about her bedroom acrobatics with her lover, a German count named Otto Ludwig; she hates children; and she cares not at all for her husband.For her birthday, Christian gives her a gold statue in his image, and even her disgust is mixed with lasciviousness.

I didn't ask for yet another likeness of my ageing husband. I asked for gold. Now I will have to pretend to love and worship the Statue and put it in a prominent place et cetera for fear of causing offence, when I would prefer to take it to the Royal Mint and melt it into an ingot which I would enjoy caressing with my hands and feet, and even take into my bed sometimes to feel solid gold against my cheek or laid between my thighs.

Kirsten's one saving grace would be her affection for Emilia, were it not for the fact that Emilia is the only person who tolerates her, and so Kirsten connives to keep her and Peter apart. Kirsten pours all her thoughts onto the page in a completely uninhibited way. She believes she deserves the reader's undivided attention, and she gets it.

Tormented by thoughts of Kirsten with her German lover, Christian reflects on his "quiet and orderly" married life with his queen and first bride, Anna Catherine of Brandenburg, who died in 1612. Here, as elsewhere, the writing truly glows:

Christian IV by Peeter IsaacszIn the darkness of the palace at Hadersleben, the skin of the young Queen's face had a luminous white sheen to it. No more light fell onto it than onto the other than onto the other faces, yet it stood out very plainly and Christian found himself wondering whether, in the very pitch of night, with the curtains of the bed drawn round them, he would turn and see this shining moonstone next to him on the pillow.

Christian IV by Peeter IsaacszIn the darkness of the palace at Hadersleben, the skin of the young Queen's face had a luminous white sheen to it. No more light fell onto it than onto the other than onto the other faces, yet it stood out very plainly and Christian found himself wondering whether, in the very pitch of night, with the curtains of the bed drawn round them, he would turn and see this shining moonstone next to him on the pillow. The abiding tone in Music and Silence one of melancholy, which reminded me in places of Tremain's Merivel. Christian uses music to calm his spirit during his endless search for perfection – which he rarely finds. In addition to his marital problems, Denmark is suffering economically, with failed mining ventures and a near-empty treasury. The darkness, though, is embedded with many bright spots: music, love, and hope for the future.

If asked to choose between the two Tremain novels I'd read, I'd have to say I prefer Merivel, for the entertaining company of the man himself, but I thoroughly enjoyed Music and Silence, too, both for its language and style and for the depictions of its excellent cast of characters.

Published on June 08, 2013 06:00

June 6, 2013

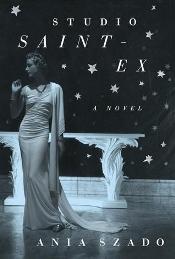

The Writer's Uncanny Valley: A guest post by Ania Szado, author of Studio Saint-Ex

Ania Szado, author of Studio Saint-Ex (reviewed here on Tuesday), has written an original guest post about the interface between fact and fiction which takes a completely new approach to the subject. We have a giveaway opportunity at the end, too, for US and Canadian readers.

~

In robotics, there's a hypothesis called "uncanny valley." It says that although we're comfortable with robots that don't look at all like real people, we get creeped out when an android's features and movements are close to (but not exact replicas of) those of a human being. While researching and writing Studio Saint-Ex, I found myself thinking about a parallel in the creation of historical fiction: presenting brazen deviations from the truth can be easier to stomach than slight variations on reality.

In robotics, there's a hypothesis called "uncanny valley." It says that although we're comfortable with robots that don't look at all like real people, we get creeped out when an android's features and movements are close to (but not exact replicas of) those of a human being. While researching and writing Studio Saint-Ex, I found myself thinking about a parallel in the creation of historical fiction: presenting brazen deviations from the truth can be easier to stomach than slight variations on reality. In Studio Saint-Ex, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry writes The Little Prince in 1940s New York while involved with two determined, creative women—only one of whom existed in real life. Did I cringe as I created a fictional lover for Saint-Exupéry? Actually, no. It was a bold departure, but I felt comfortable. Like the robot that looks robotic, there was no pretence that the character Mignonne was a re-creation of someone real.

What got under my skin were the small discrepancies that research unearthed, elements that troubled me because (like those slightly unrefined androids) they seemed vaguely off, not quite aligned with what I had believed to be true. I'd been certain, for example, that WWII garments were uninspired and uptight... but here was real-life designer Valentina (in a book by Kohle Yohannan) astounding my eye with some of the most luxurious, sensual, and inspired fashions I'd ever seen, and in the very place and time period of Studio Saint-Ex. Could I give the same aesthetic to designer Mig? It was justifiable. Provable. But how to make it believable?

Ania Szado (credit: Joyce Ravid)If I were a roboticist, I'd perfect my android further. The hypothesis says we start feeling receptive and empathetic again once the robot has been meticulously refined and crafted to appear entirely like a human being.

Ania Szado (credit: Joyce Ravid)If I were a roboticist, I'd perfect my android further. The hypothesis says we start feeling receptive and empathetic again once the robot has been meticulously refined and crafted to appear entirely like a human being. I gritted my teeth and set out to make Mig feel indisputably real, to push through the valley of discomfort into the welcome realm of suspended disbelief.

Here's my three-stage version of the writer's uncanny valley: (a) feeling good that we've started, unconcerned that our characters are still more wooden than human; (b) growing nauseous—the more we research and refine our characters, the more we see where our efforts are failing in a million tiny, excruciating ways; (c) crawling out of that dark hole into the glorious sense that we know them—those fully realized, deeply felt people who populate our pages—as well as we know ourselves.

~

Interested in your own copy of Studio Saint-Ex? Please fill out the form below; deadline Friday, June 14th. The winner will be selected via a random drawing with the help of random.org. This giveaway is open to US and Canadian readers. Good luck!

>Loading...

Published on June 06, 2013 06:00