Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 121

March 15, 2013

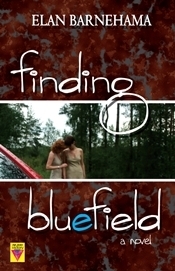

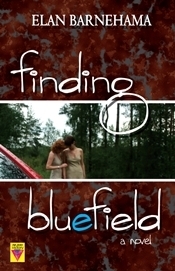

Guest post from Elan Barnehama, author of Finding Bluefield: Embracing Change

With Elan Barnehama's guest post for today, we move much closer to recent times: the colorful and turbulent 1960s, as experienced by a lesbian couple. If you believe history only encompasses events from the distant and untouchable past, or focuses mainly on well-known names, read this essay and think again. Many of the sentiments he expresses below resonated with me, and I hope you'll enjoy reading his post also.

~

Embracing ChangeElan Barnehama

My debut novel, Finding Bluefield, chronicles the lives of two women who, by seeking love and family, found themselves navigating unknown territory during a time when relationships like theirs were mostly hidden and often dangerous. It is a multi-generational family saga spanning the years 1960-1983 and set against a background of segregation, Martin Luther King’s March on Washington, the JFK election, Woodstock, the South, the Moon Landing, and the Sanctuary Movement.

The 1960s were loud, idealistic, and divisive with a lot of good music and free love. Outrageous was the norm for a counter-culture that approached activism as theater and turned personal statements into political manifestos. As the nation shook off the sleepy '50s, it found JFK in the White House inspiring hope and symbolizing a generational shift in power. But then there were all those assassinations, the Vietnam War, our cities on fire, and a turbulent civil rights movement. It didn’t take long for the US to find itself in one serious identity crisis. And that was where I wanted my characters to begin.

The 1960s were loud, idealistic, and divisive with a lot of good music and free love. Outrageous was the norm for a counter-culture that approached activism as theater and turned personal statements into political manifestos. As the nation shook off the sleepy '50s, it found JFK in the White House inspiring hope and symbolizing a generational shift in power. But then there were all those assassinations, the Vietnam War, our cities on fire, and a turbulent civil rights movement. It didn’t take long for the US to find itself in one serious identity crisis. And that was where I wanted my characters to begin.

I’m interested in what happens below the surface, away from the spotlight, inside the crowds. Great events are as much about the leaders as they are about the participants. Individual stories contribute to the moment and add up to a movement. We all collaborate to create history. It’s a team sport.

Finding Bluefield is located within arm’s length of some of great moments. As the nation searched to find its footing, Nicky and Barbara were finding theirs. Kennedy’s victory, which included winning Nicky’s home state of Virginia, inspired her to act. She already had courage. The election victory gave her hope. She thought it gave her cover.

Later, Nicky attended the Martin Luther King March on Washington—where Dr. King shared his dreams with the world—because she wanted to see history. The DC Mall and huge crowd provided a venue and an opportunity for Nicky to anonymously sleep with a man in order to have a child in this pre-sperm donor, pre-in vitro fertilization world. But the scene’s main purpose was to highlight that Nicky’s rights as a lesbian were not on the agenda. The march was not for her. It did not have her back.

After Paul was born, Nicky and Barbara planned to raise him in the Bluefield home that bore Nicky’s family name for two hundred years. But, once word spread that Nicky was a lesbian, it turned out that two hundred years was not nearly long enough for Nicky to maintain her local status, her insider membership. Sure, change was going to come, but Nicky’s dream for her child turned out to be premature.

While working on the first draft of Finding Bluefield, I remembered reading a number of articles citing cases where courts used existing laws to justify removing children from gay and lesbian parents. In some cases in the 1950s and '60s, courts gave custody of children to fathers in divorces where the mother was "rumored" or confirmed to be a lesbian, in stark contrast to the almost universal approach, at the time, of granting custody to mothers.

Change, it turns out, is slow and messy. It often stumbles. And there are always casualties. Sometimes the casualties are caused by friendly fire. Many people grew frustrated with the pace of change in the '60s and became disillusioned. Others simply burnt out. I wanted to create characters that avoided the “loud and proud” megaphone, in-your-face lifestyle that was so much a part of the time but were in it for the long term.

author Elan BarnehamaNicky and Barbara never apologized for who they were, and they never pretended to be straight. They didn’t go to elaborate lengths to cover up who they were. Their focus was to create a life together and have a family. They kept their lives to themselves and shared it only with the people they cared about. They were trying to get from one moment to the next safely, with grace, integrity, and love. By doing that, they became the role models they lacked. When their lives became other people’s business—like Carol Ann, Nicky’s sister—they were at risk.

author Elan BarnehamaNicky and Barbara never apologized for who they were, and they never pretended to be straight. They didn’t go to elaborate lengths to cover up who they were. Their focus was to create a life together and have a family. They kept their lives to themselves and shared it only with the people they cared about. They were trying to get from one moment to the next safely, with grace, integrity, and love. By doing that, they became the role models they lacked. When their lives became other people’s business—like Carol Ann, Nicky’s sister—they were at risk.

Blending stories into the study and contemplation of the past has the potential to turn history into the active experience that it is. And since fiction must be believable, what the characters did, how they acted, what they thought, the decisions they made, all had to have been possible. The reader has to think it could have happened that way.

Everyone enters the world in the middle of great events—not all of them good. We can choose to embrace our lives or whine loudly about our circumstances. Or we can muster the courage to imagine a different life, a life that has yet to exist.

~

Elan Barnehama grew up in NYC, where he developed a taste for pizza and learned to recognize a joke. He's been a high school baseball coach, a radio news announcer, and a cook. He earned an MFA from UMass Amherst, and his commentaries and essays have appeared on public radio, the web, and in newspapers. He spends his days teaching college and the rest of his time writing, because between getting up in the morning and going to bed at night, it's what he wants to do. Elan lives in Northampton, MA.

Elan Barnehama's Finding Bluefield was published by Bold Strokes Books, a press focusing on LGBTQ literature, in September 2012 ($16.95, trade pb, 224pp). Find out more at the author's website, elanbarnehama.com.

~

Embracing ChangeElan Barnehama

My debut novel, Finding Bluefield, chronicles the lives of two women who, by seeking love and family, found themselves navigating unknown territory during a time when relationships like theirs were mostly hidden and often dangerous. It is a multi-generational family saga spanning the years 1960-1983 and set against a background of segregation, Martin Luther King’s March on Washington, the JFK election, Woodstock, the South, the Moon Landing, and the Sanctuary Movement.

The 1960s were loud, idealistic, and divisive with a lot of good music and free love. Outrageous was the norm for a counter-culture that approached activism as theater and turned personal statements into political manifestos. As the nation shook off the sleepy '50s, it found JFK in the White House inspiring hope and symbolizing a generational shift in power. But then there were all those assassinations, the Vietnam War, our cities on fire, and a turbulent civil rights movement. It didn’t take long for the US to find itself in one serious identity crisis. And that was where I wanted my characters to begin.

The 1960s were loud, idealistic, and divisive with a lot of good music and free love. Outrageous was the norm for a counter-culture that approached activism as theater and turned personal statements into political manifestos. As the nation shook off the sleepy '50s, it found JFK in the White House inspiring hope and symbolizing a generational shift in power. But then there were all those assassinations, the Vietnam War, our cities on fire, and a turbulent civil rights movement. It didn’t take long for the US to find itself in one serious identity crisis. And that was where I wanted my characters to begin. I’m interested in what happens below the surface, away from the spotlight, inside the crowds. Great events are as much about the leaders as they are about the participants. Individual stories contribute to the moment and add up to a movement. We all collaborate to create history. It’s a team sport.

Finding Bluefield is located within arm’s length of some of great moments. As the nation searched to find its footing, Nicky and Barbara were finding theirs. Kennedy’s victory, which included winning Nicky’s home state of Virginia, inspired her to act. She already had courage. The election victory gave her hope. She thought it gave her cover.

Later, Nicky attended the Martin Luther King March on Washington—where Dr. King shared his dreams with the world—because she wanted to see history. The DC Mall and huge crowd provided a venue and an opportunity for Nicky to anonymously sleep with a man in order to have a child in this pre-sperm donor, pre-in vitro fertilization world. But the scene’s main purpose was to highlight that Nicky’s rights as a lesbian were not on the agenda. The march was not for her. It did not have her back.

After Paul was born, Nicky and Barbara planned to raise him in the Bluefield home that bore Nicky’s family name for two hundred years. But, once word spread that Nicky was a lesbian, it turned out that two hundred years was not nearly long enough for Nicky to maintain her local status, her insider membership. Sure, change was going to come, but Nicky’s dream for her child turned out to be premature.

While working on the first draft of Finding Bluefield, I remembered reading a number of articles citing cases where courts used existing laws to justify removing children from gay and lesbian parents. In some cases in the 1950s and '60s, courts gave custody of children to fathers in divorces where the mother was "rumored" or confirmed to be a lesbian, in stark contrast to the almost universal approach, at the time, of granting custody to mothers.

Change, it turns out, is slow and messy. It often stumbles. And there are always casualties. Sometimes the casualties are caused by friendly fire. Many people grew frustrated with the pace of change in the '60s and became disillusioned. Others simply burnt out. I wanted to create characters that avoided the “loud and proud” megaphone, in-your-face lifestyle that was so much a part of the time but were in it for the long term.

author Elan BarnehamaNicky and Barbara never apologized for who they were, and they never pretended to be straight. They didn’t go to elaborate lengths to cover up who they were. Their focus was to create a life together and have a family. They kept their lives to themselves and shared it only with the people they cared about. They were trying to get from one moment to the next safely, with grace, integrity, and love. By doing that, they became the role models they lacked. When their lives became other people’s business—like Carol Ann, Nicky’s sister—they were at risk.

author Elan BarnehamaNicky and Barbara never apologized for who they were, and they never pretended to be straight. They didn’t go to elaborate lengths to cover up who they were. Their focus was to create a life together and have a family. They kept their lives to themselves and shared it only with the people they cared about. They were trying to get from one moment to the next safely, with grace, integrity, and love. By doing that, they became the role models they lacked. When their lives became other people’s business—like Carol Ann, Nicky’s sister—they were at risk. Blending stories into the study and contemplation of the past has the potential to turn history into the active experience that it is. And since fiction must be believable, what the characters did, how they acted, what they thought, the decisions they made, all had to have been possible. The reader has to think it could have happened that way.

Everyone enters the world in the middle of great events—not all of them good. We can choose to embrace our lives or whine loudly about our circumstances. Or we can muster the courage to imagine a different life, a life that has yet to exist.

~

Elan Barnehama grew up in NYC, where he developed a taste for pizza and learned to recognize a joke. He's been a high school baseball coach, a radio news announcer, and a cook. He earned an MFA from UMass Amherst, and his commentaries and essays have appeared on public radio, the web, and in newspapers. He spends his days teaching college and the rest of his time writing, because between getting up in the morning and going to bed at night, it's what he wants to do. Elan lives in Northampton, MA.

Elan Barnehama's Finding Bluefield was published by Bold Strokes Books, a press focusing on LGBTQ literature, in September 2012 ($16.95, trade pb, 224pp). Find out more at the author's website, elanbarnehama.com.

Published on March 15, 2013 05:00

March 12, 2013

Ursule Molinaro's The New Moon with the Old Moon in Her Arms, a feminist novella of ancient Greece

At an initial glance, Ursule Molinaro's feminist novella appears to be a curious amalgam of ancient Greek tragedy and scholarly discourse. The story is told with unorthodox punctuation and a self-aware modern voice, and it uses few historical fiction tropes. Readers won't find lengthy descriptions of fashion, hairstyles, or evocative foreign landscapes in this slim volume.

At an initial glance, Ursule Molinaro's feminist novella appears to be a curious amalgam of ancient Greek tragedy and scholarly discourse. The story is told with unorthodox punctuation and a self-aware modern voice, and it uses few historical fiction tropes. Readers won't find lengthy descriptions of fashion, hairstyles, or evocative foreign landscapes in this slim volume. The New Moon With the Old Moon in Her Arms isn't a traditional historical novel and shouldn't be judged by those standards. (The wonderful title, taken from the Scots ballad "Sir Patrick Spens," is just one example of the anachronistic borrowings Molinaro freely uses to make her points.)

But even within a plot nearly whittled down to its thematic essence, the author presents an absorbing and character-centered story that proceeds in an easy-to-follow, chronological fashion. The style is nowhere near as complicated as it looks.

The narrator, an unnamed poetess in Athens of 293 BC, is living through the last month before her execution. As a form of protest against the patriarchal culture, the moon goddess Circe had persuaded her to put herself forward as a Thargelia volunteer: half of a couple who will be stoned to death on the next Expulsion Day, taking the city's sins with her when she dies. Thargelia was a religious festival of ancient Greece, held in late spring; the author's research is sound in this and other instances.

Unlike past sacrificial victims, who were deformed or crippled—as was historically the case—the poetess is whole, shapely, and attractive. On the downside, she's a 30-year-old unmarried virgin whose writing has gone unnoticed, and who lived with her parents until recently. Those of an academic bent will empathize. It seems jobs in the humanities have always been hard to come by.

Living alone in secluded municipal quarters with an attendant to serve her every need, she doubts the wisdom of her choice with every new day that passes, but Circe is always there in the back of her mind with promises of laurel leaves, which will dull the pain at the end, as well as convincing arguments.

"If we succeed I might be read: the moon goddess tries to bribe me back into submission.

I'm not sure a posthumous audience is worth dying for: I say out loud into the quiet room."

If that's not enough for her to muddle through, an adolescent girl presents her with a moral dilemma, and a possible (if temporary) reprieve from her fate. The poetess also tumbles into a lusty affair with a man who makes her feel desirable. For the first time in her life, she has something to live for.

The narrator's decisions generate a fair bit of suspense (Will she take the escape route(s) offered? And if she does, will she be caught?). Interspersed with her musings, she (or Molinaro) adds informative historical digressions on linked topics: the months of the Greek calendar, the legend of Circe, the medicinal properties of stones, and interpretations of Homer's poetry—including ten excellent reasons Odysseus is overrated as a heroic figure. Those alone are worth the price of admission.

In the most prominent strand of knowledge braided into the story, Molinaro (or the narrator) provides many examples of how feminine power was deliberately subverted by men through the ages. She offers many points for discussion, and for this reason, one could easily imagine The New Moon as assigned reading in a women's history class.

This sharply intelligent, witty book shouldn't be restricted to this audience, though. It demonstrates that experimental fiction can be approachable and smoothly readable, even for historical fiction fans who wouldn't normally consider it. Anyone interested in ancient Greek history should give it a try.

~

The New Moon With the Old Moon in Her Arms (subtitled "A true story assembled through scholarly hearsay") was published by the independent literary press McPherson & Co. in 1993 in trade paperback (119pp, $10.00).

Published on March 12, 2013 12:00

March 8, 2013

Guest post by Jodi Daynard, author of The Midwife's Revolt

My guest today, Jodi Daynard, has contributed an enlightening essay covering her research discoveries about early America, as exemplified through period letters and recipes and relevant photographs. Her novel The Midwife's Revolt, a semi-finalist in Amazon's Breakthrough Novel Awards, was published this past January. Her protagonist Lizzie Boylston is a midwife, widowed at Bunker Hill, who develops a close friendship with Abigail Adams and becomes a spy for the patriot cause. Publishers Weekly has called the novel “A charming, unexpected, and decidedly different take on the Revolutionary War.”

My guest today, Jodi Daynard, has contributed an enlightening essay covering her research discoveries about early America, as exemplified through period letters and recipes and relevant photographs. Her novel The Midwife's Revolt, a semi-finalist in Amazon's Breakthrough Novel Awards, was published this past January. Her protagonist Lizzie Boylston is a midwife, widowed at Bunker Hill, who develops a close friendship with Abigail Adams and becomes a spy for the patriot cause. Publishers Weekly has called the novel “A charming, unexpected, and decidedly different take on the Revolutionary War.” Jodi will be speaking at the 2013 Historical Novel Society conference on the "American Experience" panel on Sunday morning, June 23rd. To read more about her work, go to www.jodidaynard.com.

~

Things you never learned in School about our Founding Fathers and Mothers.

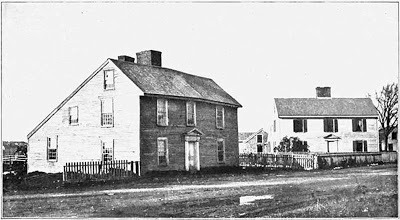

Tiny Houses, Big Dreams: After reading the letters of Abigail and John Adams, I was expecting to find that they lived in a fine house, one befitting a distinguished lawyer and his family. I was struck dumb when I saw the cramped, rustic abode in which this illustrious pair lived so much of their lives.

The dichotomy between the physical meanness and the intellectual exaltedness of the Adamses moved me. It drove home the wildly idealistic nature of their dream of independence from Britain. And yet, two hundred and thirty-one years after the enormous edifice of British rule has toppled, these humble farmhouses remain.

Money Matters: The State of Continental currency.

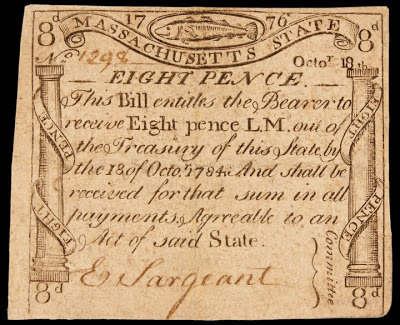

Writing The Midwife’s Revolt, I understood that money was scarce, and that my midwife would have to barter her services for food and other goods. But I didn’t really understand why. The story of Continental paper money is amusing, in a tragi-comic way: the Continental Congress needed money to pay for the war, so they produced it in great quantities. Unfortunately, the money was not backed by anything—not gold, not silver, certainly not taxes. No, it was backed by hope and prayer: hope that God was on our side, prayer that He would let us win the war. Only then might our states squeeze enough taxes out of its citizens to pay back the debt.

What’s more, these bills were easy to forge, and their growing worthlessness was hurried along by British and Tory counterfeiters like Mr. Stephen Holland, who makes an appearance in my novel.

Here is an example of one of these worthless bills, beautifully designed by Paul Revere: notice that it’s dated 1779. It is made out for eight pence and gives the bearer the right to redeem it eight years later. With any luck, the bearer would be dead by then.

Abigail Adams: “Farmeress” or First Lady?

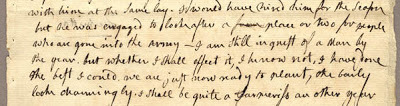

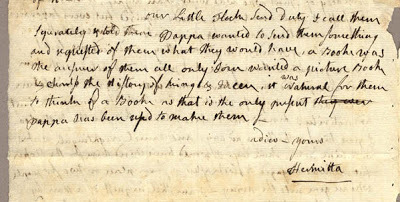

Reading the letters of Abigail’s letters, I was able to infer some interesting things about her. For this discussion, I will refer to her letter of May 14, 1776, to John Adams, who was then in Philadelphia.

May 14, 1776

I set down to write you a Letter wholy Domestick without one word of politicks or any thing of the Kind, and tho you may have matters ofinfinately more importance before you, yet let it come as a relaxation to you. Know then that we have had a very cold backward Spring, till about ten days past when every thing looks finely. We have had fine Spring rains which makes the Husbandary promise fair -- but the great difficulty has been to procure Labourers. There is such a demand of Men from the publick and such a price given that the farmer who Hires must be greatly out of pocket. A man will not talk with you who is worth hireing under 24 pounds per year. Col. Quincy and Thayer give that price, and some give more. Isaac insisted upon my giving him 20 pounds or he would leave me. …I am still in quest of a Man by the year, but whether I shall effect it, I know not. I have done the best I could. We are just now ready to plant, the barly looks charmingly, I shall be quite a Farmeriss an other year.

Our Little Flock send duty. I called them seperately and told them Pappa wanted to send them something and requested of them what they would have. A Book was the answer of them all only Tom wanted a picture Book and Charlss the History of king and Queen. It was natural for them to think of a Book as that is the only present they ever Pappa has been used to make them.

Adieu -- Yours,

Hermitta

First observation: poor Abigail couldn’t spell. But then, nobody could back then. The men, given at least some formal education, fared slightly better, but there were no standards with regard to punctuation and capitalization. Thus, Everything, especially Nouns, always seemed slightly larger than Life!

Abigail took pride in her farming. In boasting to John that she will be “quite a little farmeress,” she wishes not only to relieve his anxiety about her but to assure him that she’s on board with a popular value at that time: homespun self-sufficiency. What money she has is nearly worthless; her farm hand’s an incompetent drunk. But, by golly, she is going to get the job done—singlehandedly, if necessary.

It is jarring to tour Abigail’s later house, Peacefield, which the couple bought in 1787 and which Abigail immediately enlarged and renovated, ordering furniture from France to fill it. The later house matched their increased wealth and status, but the Gilbert Stuart portrait of Abigail, begun in 1800, will always strike me as disingenuous. Gone, it seems, is the proud “farmeress.” But I suppose that’s American upward mobility for you.

It is jarring to tour Abigail’s later house, Peacefield, which the couple bought in 1787 and which Abigail immediately enlarged and renovated, ordering furniture from France to fill it. The later house matched their increased wealth and status, but the Gilbert Stuart portrait of Abigail, begun in 1800, will always strike me as disingenuous. Gone, it seems, is the proud “farmeress.” But I suppose that’s American upward mobility for you. Finally, Abigail had a wonderful way of needling John Adams. Unlike even some of the world’s greatest statesmen, she was fearless of him. Her letter concludes with a transparent reproach: that he is forever buying books for the children, when presumably they would like something less intellectual now and then.

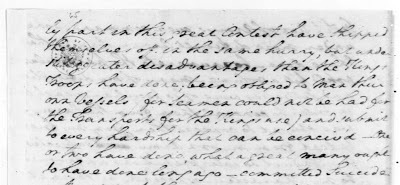

George Washington, Terrorist

In an earlier letter, dated March 31 of that year, Abigail famously teases John:

In an earlier letter, dated March 31 of that year, Abigail famously teases John:The discovery that amazed me, however, was not Abigail’s letter of March 31st but another, penned on the same day. This second letter was written by His Excellency George Washington to his brother John, and presents an eerie correspondence with Abigail’s own. Writing from Boston, Washington writes,I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could.

March 31, 1776 …all those who took upon themselves the Style, and title of Government Men in Boston, in short, all those who have acted an unfriendly part in this great Contest have Shipped themselves off in the same hurry, but under still greater disadvantages than the King's Troops have done; being obliged to Man their own Vessels (for Seamen could not be had for the Transports for the Kings use) and submit to every hardship that can be conceiv'd. One or two have done, what a great many ought to have done long ago, committed Suicide.While I knew Washington to have little sympathy for traitors, and hung people without a shred of remorse, I was shocked to discover just how venomous he could be. His was a steely radicalism that shared more with the likes of Robespierre or even Bin Laden than, say the compassionate and inwardly conflicted Abraham Lincoln. I was soon to find reverberations of Washington’s radicalism rippling out from the epicenter: in confiscation acts that took Tories’ homes and goods, in the banishments and death threats. As the war progressed, these acts took on the dangerous cast of ideological fundamentalism.

The Oyster that Ate Manhattan

On a lighter note, the abundance of New England’s wildlife at the time is astonishing. Clearly, we fought not only for independence but for the primacy of our species in this relatively new land: bears occasionally roamed the farms of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Oysters were so large that a couple could feed on a single one for dinner.

Lobsters the size of human beings were reported. Indeed, lobster was so abundant in New England waters that savvy servants wrote it into their contracts that they were not to be fed lobster more than twice a week. In January of 1779, in Braintree, the crow population grew so large that the air looked like something out of Hitchcock’s “The Birds.” Braintree’s selectmen offered its citizens 6 shillings for an old crow and 2 for a young one. By May, that offer had risen to 30 shillings for an old crow. This fact appears in a few scenes of my novel.

I conclude my wildlife section with a recipe from Revolutionary War Period Cookery, by Robert W. Pelton. It was John Adams’s favorite oyster recipe, and calls for a quart of shucked oysters. Skip it if you are not rolling in cash!

Chicken and Oysters – An Adams Family Favorite

½ cup butter

½ cup flour

1 tsp salt

1 cup spinach, chopped

¼ tsp pepper

4 cups cooked chicken, diced

4 cups cream

1 quart oysters, drained

1 cup celery, chopped fine

Put butter in cast iron skillet and melt. Add salt, pepper and cream. Blend well. Slowly stir in flour so as not to lump. Then add spinach and cooked chicken pieces. Mix everything thoroughly. Lastly add the oysters. Let mixture simmer until oysters are nice and plump. Sprinkle over nicely with fine chopped celery and serve immediately.

Strange Bedfellows

Finally, a fact that moved me most of all to discover was the physical intimacy of the time. Individuals did not feel entitled to have a great wall of space around them, as we do now. Coaches, church pews, markets, and beds were shoulder-to-shoulder crowded. Men and women had few issues with touching, kissing, and sleeping with someone of the same sex. Tolerance for odors was certainly much higher than ours—people generally bathed once a month, washed their clothing once a year. Beds were expensive and families often slept in one bed, as did travelers. Life stank.

And on this note, I’ll close with a famous story about the time John Adams and Ben Franklin were forced to share a bed while traveling from Philadelphia to Staten Island. Here is an excerpt from John Adams’s journal entry:

Sept. 6, 1776

The Taverns were so full We could with difficulty obtain Entertainment. At Brunswick, but one bed could be procured for Dr. Franklin and me, in a Chamber little larger than the bed, without a Chimney and with only one small Window….

… The Doctor then began an harrangue, upon Air and cold and Respiration and Perspiration, with which I was so much amused that I soon fell asleep…

I have often conversed with him since on the same subject: and I believe with him that Colds are often taken in foul Air, in close Rooms: but they are often taken from cold Air, abroad too. I have often asked him, whether a Person heated with Exercise, going suddenly into cold Air, or standing still in a current of it, might not have his Pores suddenly contracted, his Perspiration stopped, and that matter thrown into the Circulations or cast upon the Lungs which he acknowledged was the Cause of Colds. To this he never could give me a satisfactory Answer. And I have heard that in the Opinion of his own able Physician Dr. Jones he fell a Sacrifice at last, not to the Stone but to his own Theory; having caught the violent Cold, which finally choaked him, by sitting for some hours at a Window, with the cool Air blowing upon him.

For me, this letter reveals so much: not just about John Adams’s thorny character but about the profound closeness that could be achieved at the time. It wasn’t a good closeness; it wasn’t a bad closeness. It was an “I love you/hate you/accept you/you’re in my face” kind of closeness that is unmistakably real, unmistakably human, and that I feel, in this age of Tweetchats with cyber-strangers, more than a little nostalgic for.

The physical intimacy of these two outsize personalities is the stuff of high comedy to us now. Adams professes boredom with Franklin’s harangue, but that doesn’t mean he let the matter drop. No, he continued to argue with Franklin—for years—about the cause of the common cold. And when he reveals that Dr. Franklin finally succumbed to a bad one from “sitting hours at a window, with the cool Air blowing upon him,” his glee is obvious. John Adams always had to have the last word. And he always did—unless he happened to be speaking to his wife, Abigail.

~

Jodi Daynard is the author of The Midwife's Revolt, a novel, and The Place Within: Portraits of the American Landscape by 20 Contemporary Writers. Her stories and essays have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Paris Review, The Harvard Review, Harvard Magazine, The Boston Globe, Agni, The New England Review, and elsewhere. She taught writing in the Expository Writing Program at Harvard University, at M.I.T., and in the MFA program at Emerson College. The Midwife's Revolt was published by Opossum Press in January 2013 ($18.95 trade pb / $4.95 ebook, 440pp).

Published on March 08, 2013 06:00

March 5, 2013

An examination of Claire Holden Rothman's The Heart Specialist

Although I'm using the next month to devote attention to small press historical novels, March is best known as Women's History Month. As such, I thought The Heart Specialist would be a good selection for both events.

Although I'm using the next month to devote attention to small press historical novels, March is best known as Women's History Month. As such, I thought The Heart Specialist would be a good selection for both events.Claire Holden Rothman's quasi-biographical novel about one of the first female physicians in Canada provides an eye-opening perspective on the obstacles that modern medicine's founding mothers had to overcome.

Rothman bases her lead character on Maude Abbott, who graduated from a Montreal medical school in 1894 and became a world-renowned expert on congenital heart disease. I decided not to link to any online articles about her because then the career path of Agnes White, Dr. Abbott's fictional counterpart, would hold no surprises. However, because she's writing about an invented character, the author has greater freedom in developing Agnes's personal life, which she has creatively imagined.

Agnes is an unfashionable woman who takes interest in an unfashionable field of medicine, since few cures were possible for her unfortunate patients at that time. We first meet her in 1882 as a curious child who would rather be performing dissections than playing dress-up.

Her mother is dead, and her father Honoré Bourret, formerly a physician at McGill University, had abandoned the family in the wake of scandal after his sister's murder. Agnes believes him innocent and looks for him in every older man she sees. She and her fragile younger sister, Laure, are brought up in the Québecois village of St. Andrews East by their indomitable grandmother, who changed their last name to her own name of White.

One bright spot in Agnes's childhood is her governess, Miss Skerry, herself a woman of science and learning. There were limited choices open to educated women at the time: they could become governesses, schoolteachers, or, preferably, wives and mothers There are no true role models for "unnatural" girls like Agnes, who must blaze her own trail and face the consequences.

Writing with empathy and conviction, Rothman takes us through Agnes's pioneering journey: the long hours of study, the intellectual triumphs, and the contemptuous doctors who are her only hope for a professional education but who refuse to let her advance. Even as a middle-aged physician during the WWI years, Agnes must take the back stairway, the one reserved for "waiters and women," when meeting a colleague for dinner at McGill's University Club. The unfairness of it all comes through powerfully.

For that reason, some of the author's choices are frustrating in a different way. For the early part of her career, Agnes has a strong narrative voice, but she's given little dialogue with which to share it. When her male colleagues and superiors speak, she mostly nods, smiles, or stutters. Her emergence as an outspoken feminist wouldn't have helped her career; all the same, her excessive verbal passivity doesn't suit her ambitions or academic prowess, and I felt myself wanting to pull words out of her.

Likewise, while it gives her an appealing vulnerability, Agnes's social awkwardness is overemphasized, and her scientific detachment from her emotions edges close to stereotype. The novel's title has an ironic double meaning that plays out predictably: she has experience aplenty with cardiology but fails to recognize love when it's under her nose.

Several intertwining forces shadow Agnes throughout the novel: her desire to please her long-absent father by following in his footsteps; the guiding influence of her mentor, one of her father's former students; and a defective three-chambered heart, stored and preserved in a glass jar. At novel's end, the mysteries associated with all three are resolved in a realistic manner.

Agnes's tireless efforts are finally vindicated, and seeing her accomplishments publicly acknowledged, in the end, makes for a satisfying story. Reading this book left me with immense respect for the brave women who were the first to break out of their strictures, as well as the struggles they endured in order to be taken seriously.

In the US, The Heart Specialist was published by Soho Press out of New York in 2011 ($25.00, hb, 325pp). Cormorant Books, which specializes in new literary fiction, published it in Canada in 2009 ($21.00, pb). This was a personal purchase.

Published on March 05, 2013 11:30

March 3, 2013

Guest post by Justin Swanton, author of Centurion's Daughter

Today I'm pleased to welcome Justin Swanton, a South Africa-based novelist and illustrator, who has contributed a detail-rich essay about the twilight of Roman Gaul and the corresponding rise of the Franks under Clovis in the late 5th century. In his novel Centurion's Daughter, Aemilia, a young woman of seventeen, gets caught up in the war between the last unconquered Roman provinces and the Frankish alliance. How do you research a period that's historically important but in which the primary sources are maddeningly few? Below, Justin explains his process and the conclusions he drew from what he learned.

Today I'm pleased to welcome Justin Swanton, a South Africa-based novelist and illustrator, who has contributed a detail-rich essay about the twilight of Roman Gaul and the corresponding rise of the Franks under Clovis in the late 5th century. In his novel Centurion's Daughter, Aemilia, a young woman of seventeen, gets caught up in the war between the last unconquered Roman provinces and the Frankish alliance. How do you research a period that's historically important but in which the primary sources are maddeningly few? Below, Justin explains his process and the conclusions he drew from what he learned.~

Centurion’s Daughter is set in an era that has hardly been touched by fiction: Gaul at the end of the fifth century, when the last provinces of the Western Roman Empire were attacked by a Frankish confederation under Clovis. It is a fascinating period and an important one, as everything that happened here would determine the nature of the Middle Ages that followed.

Besides the history, you would think the personages and events would bring novelists out in droves. On one side you have Afranius Syagrius, 57, Roman aristocrat and general, epitomizing everything the old order had stood for. On the other side there is Clovis, 20, young and dynamic, who would acquire a Catholic wife he deeply respected and, later on, her religion, making him so much the future of western Europe. Clovis was a man to take incredible risks when necessary. At the Battle of Vouille he confronted a vastly superior Visigothic cavalry. What other general would have gathered his personal guards, charged straight at the Visigothic king Alaric, killed him personally in hand-to-hand combat, then galloped back to his lines with the entire enemy cavalry in hot pursuit? Riveting stuff.

So why is the period almost untouched? The problem as I found out is the research. Just things like discovering that Syagrius’s first name was Afranius was quite an achievement. Putting together a coherent picture of the time took me years and involved a careful reading of the primary sources, as well as abandoning several popular misconceptions. Let me give a few details of what I uncovered.

1. The Roman army survived the official fall of Rome. Procopius, personal secretary to the Byzantine General Belisarius, describes as something remarkable the fact that formations of the Western Imperial army had endured right up to his time, the middle of the sixth century, with their standards, uniforms and traditions intact. These were the units – former legions – that Syagrius had led with confidence against Clovis. After Syagrius fell, they were maintained by rich Roman aristocrats as bucellarii, or private troops.

Credit: Letavia2. The Roman nobility also survived the official fall of Rome. A popular conception of the fall of the Empire consists of hordes of barbarians marauding over the countryside, pillaging and burning, ending the Roman way of life forever. The truth was very different. In places like Britain, parts of Spain and north Africa, society did descend into anarchy, but this came more from internal dissolution than barbarian influence. The greater part of the former Roman territories, however, kept their societal structures intact, which meant the wealthy landed class – rich senators – remained in possession of their estates, even under barbarian rule. It is a complicated period. The new barbarian masters worked with the entrenched Roman ruling class, they did not displace it.

Credit: Letavia2. The Roman nobility also survived the official fall of Rome. A popular conception of the fall of the Empire consists of hordes of barbarians marauding over the countryside, pillaging and burning, ending the Roman way of life forever. The truth was very different. In places like Britain, parts of Spain and north Africa, society did descend into anarchy, but this came more from internal dissolution than barbarian influence. The greater part of the former Roman territories, however, kept their societal structures intact, which meant the wealthy landed class – rich senators – remained in possession of their estates, even under barbarian rule. It is a complicated period. The new barbarian masters worked with the entrenched Roman ruling class, they did not displace it. 3. It took Clovis ten years to conquer the last Roman provinces. This is my own conclusion, after comparing primary sources like Gregory of Tours, Procopius, the Life of St Genovefa, the Liber Historiae Francorum, and other works. To sum up the history, Clovis was a foederatus, or subordinate ally of Syagrius, who initially gave him the title to Belgica II, one of the four provinces he controlled. Time passed and Syagrius decided to reassert his authority over the province, setting up his capital in Soissons. In 486 Clovis gathered an alliance of Salian Franks and fought Syagrius near Soissons, defeating him. The Roman governor was deposed by his realm and forced to flee to the Visigoths, who later handed him over to Clovis for execution. The three Roman provinces not under Clovis’s control made their stand and stopped the Frankish king dead in his tracks for ten years. It was during this time that Paris was besieged and, under the leadership of St Genevieve, successfully held out against the Franks.

In 493 Clovis married St. Clotilde, a Burgundian princess whose father and mother had been murdered by her uncle. She was a Catholic and immediately set out to convert her pagan husband, partly because it was the only way to end the war between the Franks and Gallo-Romans, who would never accept a pagan ruler. Clovis loved her and allowed her to baptize their children, but only became Catholic himself when his army was on the brink of rout in a battle against the Alamans in 496. He promised the God of Clotilde he would convert if he won. The Franks rallied and went on to victory, and Clovis kept his word and was baptized on Christmas Eve that year or the year following. With Clovis a Catholic a peace could finally be brokered and the last provinces of Roman came under Frankish rule, with the exception of Brittany which remained semi-independent.

Credit: LetaviaMy own novel covers the time just before, during and after the battle near Soissons between Syagrius and Clovis. Personally I like sticking to the old Greek drama rule of having everything happen in one place during a limited period of time. Centurion’s Daughter takes place in or near Soissons over the space of a year.

Credit: LetaviaMy own novel covers the time just before, during and after the battle near Soissons between Syagrius and Clovis. Personally I like sticking to the old Greek drama rule of having everything happen in one place during a limited period of time. Centurion’s Daughter takes place in or near Soissons over the space of a year. A lot of time went into researching Gallo-Roman daily life at the end of the fifth century. Again, it wasn’t easy. I couldn’t find a book that covered clothing, eating habits, furniture and housing arrangements of Gallo-Romans at the very end of the Empire, all under one cover. It was very much a case of uncovering a bit here and a bit there. Gallo-Romans, for example, had wickerwork high-backed chairs and usually ate at tables, not lying on couches like the Romans of Italy. Money was really problematic. I didn’t have too much difficulty finding out what coins were in use, but deducing to what extent the monetary system had collapsed and been replaced by barter was much less straightforward. Coin and barter both exist in my novel. In the end I had to use educated guesswork for a number of the details.

Now that the research is substantially done I intend to use it for a number of future novels of which one is already in the pipeline, taking place near the end of the ten-year war described above. It is an exciting era, and I don’t regret the effort I put into it. I hope you enjoy the result.

~

Justin Swanton is a graphic designer and manager in a small printing firm in South Africa. Centurion’s Daughter is his first novel. He has a website and a blog. Besides writing, his interests are computer and hand drawn illustration and wargaming.

Centurion's Daughter was published by Arx in 2011 (list price $17.95, heavily discounted on Amazon; trade pb; 336pp). The Kindle edition sells for $5.97.

Published on March 03, 2013 22:00

March 1, 2013

Anne-Marie Drosso's In Their Father's Country, thoughtful reflections on 20th-century Cairo

Anne-Marie Drosso's In Their Father's Country presents a sensitive and bracingly honest view of modern Egyptian history, as seen through the eyes of a woman whose life spans nearly the entire 20th century.

Anne-Marie Drosso's In Their Father's Country presents a sensitive and bracingly honest view of modern Egyptian history, as seen through the eyes of a woman whose life spans nearly the entire 20th century.This setting may seem exotic to Western readers, but Claire Sahli and her older sister Gabrielle are modern women growing up in the cosmopolitan city of Cairo, which makes the mental transition relatively smooth.

The novel opens in 1924, when Claire is fourteen and Gabrielle fifteen. Their beloved father Selim, an experienced lawyer who is a proud crusader for the working classes, is succumbing to kidney disease. His death leaves his wife and daughters vulnerable and forces them to turn to his brother Yussef for their livelihoods.

Claire and Gabrielle's mother is Italian, and Claire can't help but wonder why her father's obituary omits the name of his wife. Was it because of her desire for privacy, or something more? As the novel progresses, secrets from her parents' history are slowly exposed, leaving Claire to decide how to react to what she learns.

The novel's title is apt. Egypt was Selim's homeland, but over time, his Greek Catholic family finds themselves increasingly pushed to the margins of Cairo society. They are privileged, but not rich, and the nationalist movement is gaining ground. Although the Sahlis favor Egypt's independence from Britain, the country's mid-20th century focus on Arab solidarity, under Nasser's rule, threatens to leave them behind altogether.

She remembered the twenties as a time when just about everyone around her was touched by nationalist fervor. Now, in her circles, many of her friends and acquaintances were saying that that the new generation of nationalists was becoming rudderless and uncontrollable. Was the current political agitation perceived in those circles as posing a fundamental threat to their existence?

Through Claire and her relatives' experiences, readers get an informative glimpse at Egypt's volatile politics and varied social values, which mix the surprisingly liberated with the very traditional. Married when she's barely out of school to a man who's considerably older, Claire later takes lovers; meanwhile, her cousin's husband stirs up conflict with his desire for a second wife.

Claire's story is spliced into segments, each of which brings an important period of her life to the forefront: the death of a past lover in 1941, the birth of her son in 1947, her unwilling job transfer to the city of Minya in 1968, a decision forced upon her by her supervisor because of political pressure. Claire moves there because she wants to keep her retirement pension, but with her high salary and lack of fluent Arabic, she is strongly resented by her coworkers.

The changing relationships between Claire and members of her large, extended family, which includes close friends and servants, figure prominently. The tensions between warm, gregarious Claire and Gabrielle, who is described as "neither tender nor nurturing," only grow as the sisters age. Because the plot jumps from one time period to another, readers are left to fill in some gaps themselves. In particular, I wish Drosso had allowed us to glimpse Claire's formative years—she skips straight from 1924 to 1941—so we could see how her personality formed.

Many chapters revolve around a relative's death, which creates a nostalgic, thoughtful feel. Adding to this sense are the different forms of literary expression included in the text, such as personal letters, journal entries, and a short memoir written by one of Claire's daughters.

In Their Father's Country is an absorbing, reflective portrait of a resilient woman, her country, and how they weathered the external forces affecting them both. It was published by Telegram Books, an independent publisher of international literary fiction, in 2009 (£7.99, US $13.95, Can $15.50, trade pb, 227pp including glossary). This was a personal purchase.

Published on March 01, 2013 14:00

Welcome to Small Press Month at Reading the Past

Individualistic. Specialized. Risk-taking. Independent. These are some words that come to mind when speaking about small presses.

Last year around this time, I started seeing bookseller reports and bloggers' posts about Small Press Month, which was traditionally held during March. I decided then that I wanted to participate the next time March rolled around. Unfortunately, the national celebration of this event seems to have fallen by the wayside for 2013 – perhaps funding was lost? – but I decided to forge ahead with my plans regardless!

Starting today, and over the next 30 days, Reading the Past will be looking exclusively at historical novels from small presses. Definitions for this term can vary, but I'll be using it to include those publishers outside of the Big Six that are independently run and not part of large conglomerates. Many of them specialize in certain types of works (literary fiction, regional settings, particular genres, and so forth). There's even a growing number of small presses that publish only historical novels, something I find very exciting.

Because they may have more modest sales expectations than the industry big boys, they can afford to take chances on topics and styles that lie outside the mainstream or which may not have huge audiences. However, while small presses may not feel as much pressure to follow trends, they can find themselves creating or shaping them. Some examples of small press titles that became breakout hits for their authors: Charles Frazier's Cold Mountain (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill), Sara Gruen's Water for Elephants (ditto), Michel Faber's The Crimson Petal and the White (Canongate), Peter Behrens' The Law of Dreams (House of Anansi), and John Shors' Beneath a Marble Sky (McPherson & Co).

Historical novels have thrived in the world of small and independent presses, and I've always enjoyed seeing the diversity they offer readers. In fact, they're a necessary part of the industry, especially now, a time when many excellent mid-list authors are being dropped by their Big Name publishers for not meeting high sales goals – or for other more nebulous or arbitrary reasons.

I have a great selection of guest posts, reviews, and previews of small press titles lined up over the course of the next month, and I hope you'll enjoy reading along and seeing what's in store.

Last year around this time, I started seeing bookseller reports and bloggers' posts about Small Press Month, which was traditionally held during March. I decided then that I wanted to participate the next time March rolled around. Unfortunately, the national celebration of this event seems to have fallen by the wayside for 2013 – perhaps funding was lost? – but I decided to forge ahead with my plans regardless!

Starting today, and over the next 30 days, Reading the Past will be looking exclusively at historical novels from small presses. Definitions for this term can vary, but I'll be using it to include those publishers outside of the Big Six that are independently run and not part of large conglomerates. Many of them specialize in certain types of works (literary fiction, regional settings, particular genres, and so forth). There's even a growing number of small presses that publish only historical novels, something I find very exciting.

Because they may have more modest sales expectations than the industry big boys, they can afford to take chances on topics and styles that lie outside the mainstream or which may not have huge audiences. However, while small presses may not feel as much pressure to follow trends, they can find themselves creating or shaping them. Some examples of small press titles that became breakout hits for their authors: Charles Frazier's Cold Mountain (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill), Sara Gruen's Water for Elephants (ditto), Michel Faber's The Crimson Petal and the White (Canongate), Peter Behrens' The Law of Dreams (House of Anansi), and John Shors' Beneath a Marble Sky (McPherson & Co).

Historical novels have thrived in the world of small and independent presses, and I've always enjoyed seeing the diversity they offer readers. In fact, they're a necessary part of the industry, especially now, a time when many excellent mid-list authors are being dropped by their Big Name publishers for not meeting high sales goals – or for other more nebulous or arbitrary reasons.

I have a great selection of guest posts, reviews, and previews of small press titles lined up over the course of the next month, and I hope you'll enjoy reading along and seeing what's in store.

Published on March 01, 2013 04:00

February 27, 2013

Guest post by Tanis Rideout, author of Above All Things

Tanis Rideout is stopping by Reading the Past today with a wonderful original essay about her research process – specifically on the artifacts that informed her work and helped her reach back and touch the past.

Her debut novel, Above All Things, intertwines the viewpoints of English mountaineer George Mallory, as he makes his third and final attempt to scale Mt. Everest in 1924, and that of his wife, Ruth, who was left behind in Cambridge with their children. Above All Things will be published on March 7th by Viking Penguin (UK), and it has already been receiving many accolades in Canada and the US. I'll be posting a review later this spring, and this post has definitely whetted my appetite for more.

~

Viking Penguin ed. (March 2013)Part of what first drew me to the story of George Mallory’s 1924 attempt on Everest was the mystery and mythology. How could I not be fascinated by all of it? George was one of the last of the classic English explorers – athlete, scholar, a writer with ties to the Bloomsbury group; a romantic figure whose friends called him Galahad and whose admirers compared him to a Greek statue. He’s the root of the enigmatic quote that we use as a culture to explain away our strange drives to do things – Because it’s there – and he tragically, mysteriously disappeared.

Viking Penguin ed. (March 2013)Part of what first drew me to the story of George Mallory’s 1924 attempt on Everest was the mystery and mythology. How could I not be fascinated by all of it? George was one of the last of the classic English explorers – athlete, scholar, a writer with ties to the Bloomsbury group; a romantic figure whose friends called him Galahad and whose admirers compared him to a Greek statue. He’s the root of the enigmatic quote that we use as a culture to explain away our strange drives to do things – Because it’s there – and he tragically, mysteriously disappeared.

But myth and mystery are simply beginnings. I began to read everything I could get my hands on about Everest and George Mallory – scouring the local library, used bookstores, and online speciality booksellers. One of the many wonderful things about writing in the internet age are the vast online resources of materials – images, films, essays – that are at a writer’s fingertips. Still, nothing is quite a meaningful or useful as the real thing.

A draft or so into the novel I received a grant from the Canadian government. This one not only provided me with time to write but also had money attached for travel and research. I packed my bags and headed for England, where I spent time at the Samuel Pepys Library at Magdalene College in Cambridge, The Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society (the RGS).

One of the things I love about well-executed historical fiction is the way in which the era seems to soak the pages – as though they have been immersed in it. A certain age can breathe on the page in a well written work. The job of the writer is to conjure that time and place a reader in it without, ideally, either of them being bogged down by details and ephemera. This was what I was faced with at these extraordinary collections – more detail than I had ever thought was possible. How was I to choose?

Putnam US/Amy Einhorn ed.

Putnam US/Amy Einhorn ed.

(Feb. 2013)The RGS in particular, with their boxes and boxes of files, holding every scrap of paper that was associated with the expedition, was a treasure trove. While each file was labelled according to dates with some indication what would be in it, often there was a great deal more than what I was expecting. There were photographs I’d never seen before, and long elegant strips of Tibetan calligraphy on onion skin paper with a tiny notation in the corner indicating it was a receipt for ponies. There was a fragile notebook from Camp IV indicating the weather, who had been at camp and how they were feeling. As I carefully peeked under the barely open cover, not wanting to crack and break the old spine, I imagined George jotting down stomach ailments and headaches, snow skirmishes and sunny days.

There were a number of items that I found that stuck with me, and either found their way directly in to the book or became jumping off points for an event or scene. The first was a massive ledger – a manifest of everything that had been packed in to crates and sent across the great Himalayan plateau – everything that was needed for the expedition to survive so far from home for long, isolated months. One item in particular caught my attention. There was a listing for six Hudson Bay Blankets (not to be used by coolies). I’m sure part of me stopped at the line because of its Canadian content – Hudson Bay Blankets are a familiar item to most Canadians – their iconic stripes and warmth decorate many northern cottages – but there was so much captured in that one line. It wasn’t just the kind of materials they took with them, but also the hierarchy with which they could be used. It allowed me to imagine what other items might be used with such conditions.

Another was the telegram. I’d seen photos of the telegram before, seen the text in books, but here it was – the actual telegram that was delivered to the RGS announcing the deaths of George and Sandy. There was the hard type with a superscript in pencil translating it. I could begin to imagine the distance it travelled, the clerk or assistant receiving it at the office, the translation of the code. All of the details added colour and texture to my imagined world.

McClelland & Stewart ed.,

McClelland & Stewart ed.,

Canada (June 2012)The last was a letter. I’d probably already read hundreds of letters when I came across this one, maybe even thousands, but this one stopped me before I even picked it up. Letters were different in the early part of the twentieth century, that’s the first thing you need to know. They were often written on pamphlet style pages, a larger sheet of paper that had been folded in two, so that you had a small four page booklet to write on. Usually a person’s address would be already printed at the top. If the person writing was in mourning the edges of the pages would be printed black. That was what I had noticed first – and I knew immediately whose letter I would be reading. It was a letter from Ruth to a friend of both her and George – and it was painful and generous and sad and brave. As a writer though, it wasn’t just the content of the letter that grabbed me – it was the paper, the ink, the black edge.

It’s these physical objects and all the meaning and coding of a time and place that help both the reader and writer conjure the era and its inhabitants. These are the details to build a fictional world on.

~

Tanis Rideout's work has appeared in numerous publications and been shortlisted for several prizes, including the Bronwen Wallace Memorial Award for Emerging Writers and the CBC Literary Award. In 2006, she was named the Poet Laureate for Lake Ontario by the environmental advocacy group Lake Ontario Waterkeeper and joined Gord Downie of Canadian rock band, The Tragically Hip on a tour to promote environmental justice on the lake. Born in Belgium, Tanis grew up in Bermuda and in Kingston, Ontario, and now lives in Toronto. She recently received her MFA from the University of Guelph-Humber. Her first novel, Above All Things, will be published by Viking Penguin (UK) on 7th March.

Her debut novel, Above All Things, intertwines the viewpoints of English mountaineer George Mallory, as he makes his third and final attempt to scale Mt. Everest in 1924, and that of his wife, Ruth, who was left behind in Cambridge with their children. Above All Things will be published on March 7th by Viking Penguin (UK), and it has already been receiving many accolades in Canada and the US. I'll be posting a review later this spring, and this post has definitely whetted my appetite for more.

~

Viking Penguin ed. (March 2013)Part of what first drew me to the story of George Mallory’s 1924 attempt on Everest was the mystery and mythology. How could I not be fascinated by all of it? George was one of the last of the classic English explorers – athlete, scholar, a writer with ties to the Bloomsbury group; a romantic figure whose friends called him Galahad and whose admirers compared him to a Greek statue. He’s the root of the enigmatic quote that we use as a culture to explain away our strange drives to do things – Because it’s there – and he tragically, mysteriously disappeared.

Viking Penguin ed. (March 2013)Part of what first drew me to the story of George Mallory’s 1924 attempt on Everest was the mystery and mythology. How could I not be fascinated by all of it? George was one of the last of the classic English explorers – athlete, scholar, a writer with ties to the Bloomsbury group; a romantic figure whose friends called him Galahad and whose admirers compared him to a Greek statue. He’s the root of the enigmatic quote that we use as a culture to explain away our strange drives to do things – Because it’s there – and he tragically, mysteriously disappeared.But myth and mystery are simply beginnings. I began to read everything I could get my hands on about Everest and George Mallory – scouring the local library, used bookstores, and online speciality booksellers. One of the many wonderful things about writing in the internet age are the vast online resources of materials – images, films, essays – that are at a writer’s fingertips. Still, nothing is quite a meaningful or useful as the real thing.

A draft or so into the novel I received a grant from the Canadian government. This one not only provided me with time to write but also had money attached for travel and research. I packed my bags and headed for England, where I spent time at the Samuel Pepys Library at Magdalene College in Cambridge, The Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society (the RGS).

One of the things I love about well-executed historical fiction is the way in which the era seems to soak the pages – as though they have been immersed in it. A certain age can breathe on the page in a well written work. The job of the writer is to conjure that time and place a reader in it without, ideally, either of them being bogged down by details and ephemera. This was what I was faced with at these extraordinary collections – more detail than I had ever thought was possible. How was I to choose?

Putnam US/Amy Einhorn ed.

Putnam US/Amy Einhorn ed. (Feb. 2013)The RGS in particular, with their boxes and boxes of files, holding every scrap of paper that was associated with the expedition, was a treasure trove. While each file was labelled according to dates with some indication what would be in it, often there was a great deal more than what I was expecting. There were photographs I’d never seen before, and long elegant strips of Tibetan calligraphy on onion skin paper with a tiny notation in the corner indicating it was a receipt for ponies. There was a fragile notebook from Camp IV indicating the weather, who had been at camp and how they were feeling. As I carefully peeked under the barely open cover, not wanting to crack and break the old spine, I imagined George jotting down stomach ailments and headaches, snow skirmishes and sunny days.

There were a number of items that I found that stuck with me, and either found their way directly in to the book or became jumping off points for an event or scene. The first was a massive ledger – a manifest of everything that had been packed in to crates and sent across the great Himalayan plateau – everything that was needed for the expedition to survive so far from home for long, isolated months. One item in particular caught my attention. There was a listing for six Hudson Bay Blankets (not to be used by coolies). I’m sure part of me stopped at the line because of its Canadian content – Hudson Bay Blankets are a familiar item to most Canadians – their iconic stripes and warmth decorate many northern cottages – but there was so much captured in that one line. It wasn’t just the kind of materials they took with them, but also the hierarchy with which they could be used. It allowed me to imagine what other items might be used with such conditions.

Another was the telegram. I’d seen photos of the telegram before, seen the text in books, but here it was – the actual telegram that was delivered to the RGS announcing the deaths of George and Sandy. There was the hard type with a superscript in pencil translating it. I could begin to imagine the distance it travelled, the clerk or assistant receiving it at the office, the translation of the code. All of the details added colour and texture to my imagined world.

McClelland & Stewart ed.,

McClelland & Stewart ed.,Canada (June 2012)The last was a letter. I’d probably already read hundreds of letters when I came across this one, maybe even thousands, but this one stopped me before I even picked it up. Letters were different in the early part of the twentieth century, that’s the first thing you need to know. They were often written on pamphlet style pages, a larger sheet of paper that had been folded in two, so that you had a small four page booklet to write on. Usually a person’s address would be already printed at the top. If the person writing was in mourning the edges of the pages would be printed black. That was what I had noticed first – and I knew immediately whose letter I would be reading. It was a letter from Ruth to a friend of both her and George – and it was painful and generous and sad and brave. As a writer though, it wasn’t just the content of the letter that grabbed me – it was the paper, the ink, the black edge.

It’s these physical objects and all the meaning and coding of a time and place that help both the reader and writer conjure the era and its inhabitants. These are the details to build a fictional world on.

~

Tanis Rideout's work has appeared in numerous publications and been shortlisted for several prizes, including the Bronwen Wallace Memorial Award for Emerging Writers and the CBC Literary Award. In 2006, she was named the Poet Laureate for Lake Ontario by the environmental advocacy group Lake Ontario Waterkeeper and joined Gord Downie of Canadian rock band, The Tragically Hip on a tour to promote environmental justice on the lake. Born in Belgium, Tanis grew up in Bermuda and in Kingston, Ontario, and now lives in Toronto. She recently received her MFA from the University of Guelph-Humber. Her first novel, Above All Things, will be published by Viking Penguin (UK) on 7th March.

Published on February 27, 2013 08:00

February 25, 2013

Time's Echo by Pamela Hartshorne, a time-slip set in Tudor-era and modern York

Hartshorne’s engaging time-slip opens with one chilling scene after another. Hawise, a young Elizabethan woman, is drowned as a witch on All Hallows’ Eve, the bells of York Minster ringing in the background. As the River Ouse drags her skirts down, she dies in fear, knowing she’s leaving her daughter Bess in the hands of an evil man.

Hartshorne’s engaging time-slip opens with one chilling scene after another. Hawise, a young Elizabethan woman, is drowned as a witch on All Hallows’ Eve, the bells of York Minster ringing in the background. As the River Ouse drags her skirts down, she dies in fear, knowing she’s leaving her daughter Bess in the hands of an evil man.In the present, Grace Trewe awakens in her late godmother Lucy’s house in York, having dreamt of Hawise’s last moments. Or perhaps she’s having flashbacks to past trauma, as a survivor of the ´04 tsunami. After traveling from Asia to claim her surprising inheritance, she hopes to move on quickly but finds herself caught by Hawise’s life. Grace’s neighbor, single father Drew Dyer, is a local historian who offers his help. He’s not quite handsome, but she finds his solidity and strength attractive.

There’s no mistaking this novel’s genre. In the first 40 pages, Grace experiences déjà vu, sees an apparition, and has multiple visions of a long-ago time. Rotting apples mysteriously appear, along with their putrid scent (a unique and eerie touch). The supernatural elements feel overdone initially, and some words in the text repeat too often, but the two women’s stories are equally gripping and deftly blended together. In 1577, Hawise is a mercer’s servant whose future turns unexpectedly bright, but her unconventional habits and an unwanted suitor’s obsession lead to her downfall. As Grace and Drew grow closer, Hawise’s presence becomes more intrusive. Is Grace possessed or suffering from PTSD? Will she die from drowning, just like Hawise and Lucy?

A novel of jealousy, passion, revenge, witchcraft, and coming to grips with the past, Time’s Echo is haunting and dramatic, with a sterling sense of place. Tudor York comes marvelously alive with its bustling marketplace, cobblestone streets, and plenty of interesting details on running a household. Enjoyable escapist reading.

Time's Echo was a personal purchase of mine in late 2012, and I wrote up my thoughts on it for February's Historical Novels Review. It was published last September by Pan in paperback (£7.99, 467pp). It's one of six titles on the 2013 shortlist for the Romantic Novelists' Association's Historical Romantic Novel. The winner will be announced tomorrow, February 26th, in London.

Published on February 25, 2013 18:02

February 22, 2013

Barbara Lazar's The Pillow Book of the Flower Samurai, about a woman's quest in Heian-era Japan

There’s nothing like fiction set in 12th-century Buddhist Japan to shake up one’s notions about feminine strength and bravery.

There’s nothing like fiction set in 12th-century Buddhist Japan to shake up one’s notions about feminine strength and bravery.Kozaishō, the narrator for Lazar’s well-researched epic, is an uncommon heroine who has little freedom and few choices but whose powerlessness increases her resolve. Born the fifth daughter to rural peasants, she is just a child when her impoverished father trades her away for more land. Even then, she knows her responsibility to honor her family. The novel’s strongest attribute is its adherence to period values; it immerses readers in a foreign culture in which respect, dignity, and obedience are paramount. These aren’t always easy concepts for Western readers to grasp, but as Kozaishō pointedly states, “Submission is not surrender.”

Although she is quite young for a good part of the book, this is definitely an adult story, one with intensely rendered scenes of elegance and cruelty. It also defies expectations in another way. Kozaishō’s early rivalry with an older girl looks to move into Memoirs of a Geisha territory, but this doesn’t last very long. Tashiko becomes her best friend and more as they train as dancers at a remote shōen (estate) and later become Women-for-Play – prostitutes – under a brutal mistress’s supervision.

Thanks to favorable omens, Kozaishō gets tutored in the samurai arts, and she also becomes a talented storyteller whose pillow-talk to powerful clients reaps influential benefits. Her poems and stories, included in the text, lend it an authentic feel. Kozaishō’s voice has a compelling intimacy, but as her universe widens, and she learns more about the Taira and Minamoto clan wars, it sometimes gets lost amid the larger political picture.

Thanks to favorable omens, Kozaishō gets tutored in the samurai arts, and she also becomes a talented storyteller whose pillow-talk to powerful clients reaps influential benefits. Her poems and stories, included in the text, lend it an authentic feel. Kozaishō’s voice has a compelling intimacy, but as her universe widens, and she learns more about the Taira and Minamoto clan wars, it sometimes gets lost amid the larger political picture. With her debut novel, Lazar creates a striking portrait of an unfamiliar time, and of a valiant woman determined to avenge a terrible wrong and overcome the odds stacked against her.

The Pillow Book of the Flower Samurai was published by Headline in January at £7.99 (pb, 560pp, cover at right). The hardcover is also available (£16.99, cover at top left). American readers can preorder it via the US distributor, Trafalgar Square, who will make it available this June in hardcover ($24.95, heavily discounted at Amazon). I bought a copy at Waterstones in London just before the Historical Novel Society conference last October. This review appears in the Feb 2013 issue of the Historical Novels Review .

Published on February 22, 2013 12:36