Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 126

October 4, 2012

A British interlude, in pictures

Hope you'll pardon my absence over the past two weeks. I've been doing a little traveling.

The ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, in the center of Glastonbury

The ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, in the center of Glastonbury

The Roman Baths, Bath, on a rainy September morning

The Roman Baths, Bath, on a rainy September morning

Wells Cathedral, Wells, on a rainy afternoon

Wells Cathedral, Wells, on a rainy afternoon

Stonehenge, on the day of the autumnal equinox

Stonehenge, on the day of the autumnal equinox

(timing not planned in advance)

The stone circle at Avebury

The stone circle at Avebury

A familiar sight in downtown London  The HNS London conference! We had a great time.

The HNS London conference! We had a great time.

Detailed reports, and video footage, available at the HNS site. The Tower of London. Mark and I had dinner with Andrea from the

The Tower of London. Mark and I had dinner with Andrea from the

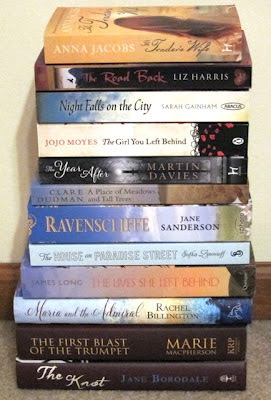

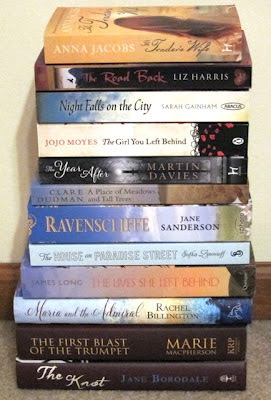

Queen's Quill Review on Monday night, then saw Margaret George speak there. And, of course, London book shopping!

And, of course, London book shopping!

I'm still pretty jet-lagged, and caught a cold after we got back, so I haven't been able to do much for the past two days other than stare at the screen. Regular blog features will resume shortly.

The ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, in the center of Glastonbury

The ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, in the center of Glastonbury The Roman Baths, Bath, on a rainy September morning

The Roman Baths, Bath, on a rainy September morning

Wells Cathedral, Wells, on a rainy afternoon

Wells Cathedral, Wells, on a rainy afternoon

Stonehenge, on the day of the autumnal equinox

Stonehenge, on the day of the autumnal equinox (timing not planned in advance)

The stone circle at Avebury

The stone circle at Avebury

A familiar sight in downtown London

The HNS London conference! We had a great time.

The HNS London conference! We had a great time.Detailed reports, and video footage, available at the HNS site.

The Tower of London. Mark and I had dinner with Andrea from the

The Tower of London. Mark and I had dinner with Andrea from the Queen's Quill Review on Monday night, then saw Margaret George speak there.

And, of course, London book shopping!

And, of course, London book shopping! I'm still pretty jet-lagged, and caught a cold after we got back, so I haven't been able to do much for the past two days other than stare at the screen. Regular blog features will resume shortly.

Published on October 04, 2012 19:00

September 19, 2012

An interview with Kim Rendfeld, author of The Cross and the Dragon

Today I'm welcoming Kim Rendfeld to the blog for an interview about her debut novel The Cross and the Dragon (Fireship Press, July), a tale of revenge, sacrifice, and enduring love set in the Kingdom of the Franks during the beginning of Charlemagne's reign. I first met Kim through our involvement with the Historical Novel Society and couldn't pass up the opportunity to speak with her about her characters, writing style, and original and compelling setting, among other things.

Today I'm welcoming Kim Rendfeld to the blog for an interview about her debut novel The Cross and the Dragon (Fireship Press, July), a tale of revenge, sacrifice, and enduring love set in the Kingdom of the Franks during the beginning of Charlemagne's reign. I first met Kim through our involvement with the Historical Novel Society and couldn't pass up the opportunity to speak with her about her characters, writing style, and original and compelling setting, among other things.The Cross and the Dragon opens with the viewpoint of Alda, a 14-year-old noblewoman from 8th-century Francia (present-day Germany). Alda's brother has betrothed her to Count Ganelon of Dormagen, who she knows will treat her cruelly. Although she eventually succeeds in winning the man she loves, Prince Hruodland, their marriage incites the anger of Ganelon, who vows revenge. Worried about her husband's safety when King Charles calls him away to fight for a Christian stronghold in Hispania, Alda gives him her dragon amulet. The remainder of their story doesn't take a predictable route.

Kim was inspired by an old German tale involving Hruodland, who is best known as the hero from the epic poem "The Song of Roland." I enjoyed seeing how she wove material from this ancient story into a historically accurate backdrop, one full of beautiful descriptions of the Rhine Valley, while fleshing out the characters and their motivations. The plot moves from Alda's family home at Drachenhaus to King Charles' court to the battlefields of Hispania and, in the second half of the book, to Francia's religious houses. The novel also includes a great scene in which Hruodland listens, in puzzlement and dismay, to a song recounting his purported actions at the Battle of Roncevaux (see more at Kim's guest blog for Unusual Historicals). This had me musing about the process through which history is transformed into legend.

What appeals to you about the era and realm of Charlemagne, so much so that you decided to use it as a setting for your historical fiction?

A romantic legend about Roland (Hruodland in The Cross and the Dragon) drew me to this period. When I started writing, I knew very little about the Middle Ages, let alone the Carolingian era (eighth and ninth centuries). As I learned about the history, I became fascinated by the personalities and the culture. Among aristocrats, the personal and the political were intertwined. The king’s marriage made a direct impact on his country’s politics and international relations.

This was also an age that believed in divine intervention, in which Christians held litanies in the hopes of victory. Yet vestiges of paganism remained. It was common for medieval people to wear amulets for magical protection, as Alda does.

All these elements are great fodder for a writer.

Given the limited number of sources, how did you go about researching the daily lives of women in the Carolingian era?

This period lends itself to a paucity of information in general. Few people could read, and even fewer could write. It also predates the printing press, which means information was not mass produced.

Fortunately, scholars have found some sources and shared what they know. Among the resources are Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne by Pierre Riché (translated by Jo Ann McNamara) and articles by Janet Nelson, including “Women in Charlemagne’s Court: A Case of Monstrous Regiment.” Sometimes when I had a hole to fill, I would use Daily Life in Medieval Times (three books in one) by Frances and Joseph Gies, keeping in mind that this was a different country and century. I’ve posted more resources for historical research on my website, www.kimrendfeld.com.

I could not have written The Cross and the Dragon without the work of scholars and will repeat the historical novelist’s disclaimer: any mistakes are mine and mine alone.

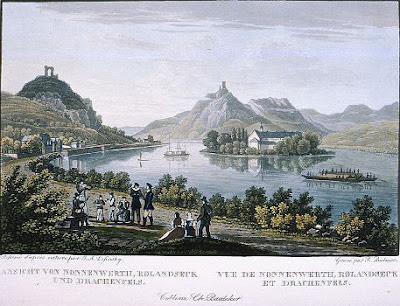

You've written about being inspired by a romantic legend surrounding the ruins at Rolandsbogen in Germany, one that reinterprets characters from “The Song of Roland.” What inspired you to work in mentions of the myth of Siegfried and the dragon as well?

Part of it is geography. Drachenfels, the legendary mountain (technically a high hill) where Siegfried killed the dragon, is across the Rhine from my heroine’s home. Worms, where Siegfried was murdered, is a seven- to ten-day journey upriver. In an age when storytelling was a form of entertainment, Alda would have heard the tales repeatedly, made all the more real because Drachenfels is so close.

The Siegfried myth also opens a window on the society in which The Cross and the Dragon takes place. Every culture has legends that reflect and shape its identity. A young man slaying a powerful monster reveals how the Franks saw the ideal warrior.

This circa 1830 illustration shows Nonnenwerth Island. In the distance are

This circa 1830 illustration shows Nonnenwerth Island. In the distance are Rolandsbogen and Drachenfels.

(Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons)

I especially enjoyed the many scenes that were set in the Benedictine abbey at Nonnenwerth and the Abbey of St. Stephen, since they emphasized the importance of religion, as well as people's internal conflicts between godliness and worldliness. How did you set out to re-create the mindset of this very different time?

The desire to explain our world is part of human nature. In the 21st century, science plays a large part in our understanding when we ask why. In the Middle Ages, religion and magic filled that role. Once you realize that medieval people had their own logic, the mindset falls into place.

Writings from medieval people also reveal to how they saw the divine and provide some tools to getting into the mindset. Written in the sixth century, The Rule of Saint Benedict outlines how the saint wants monasteries to be run. Eighth- and ninth-century Frankish annals and letters cite Scripture and use such phrases as “through the grace of God” when recounting a victory and “hateful to God” to describe an enemy.

In reading The Cross and the Dragon, I got the impression you gave considerable thought to character names. Was there ever any question in your mind about using Frankish names for your main characters, rather than the more familiar ones taken from the poem?

Using the Frankish variant of the names is another way to transport readers to another time and place, although I occasionally questioned the decision when I got rejections. I wanted names appropriate to the characters’ ethnicity yet accessible to modern readers.

I changed several characters’ names after receiving a rejection for my second manuscript. Among other things, the editor said she wanted the historical characters to play a greater role. I went back to the manuscript for The Cross and the Dragon because it had more historical characters and well-known fictional ones, and I planned to submit it to the editor through my then agent. That was when I borrowed heavily from “The Song of Roland.”

Still, it was important that the characters’ names reflect their origins. So I stuck with Hruodland rather than Roland. Oliver, Roland’s best friend in the poem, sounded too French for a guy from a locality in today’s Germany, which is why he’s Alfihar in the novel.

Alda changes over the course of the novel from a romantically inclined teenager to a still willful but less impulsive young woman, one who matures after being touched by loss. Did you find any stage in her life easier or more challenging to write about?

In the earlier stages of Alda’s life, I had to grapple with how mature a medieval teenager would be. Adolescence was not the special time it is today. Alda is considered a marriageable woman at the same age I was in middle school. I came to the conclusion that teenagers can and will rise to the challenges presented to them. It was a little easier to write about Alda when she was touched by loss because we all grieve, regardless of our era.

The greater challenge with Alda is that she is a medieval woman, and I must yield to her medieval sensibilities. For example, she believes caring for servants is an obligation, but she will slap them when they get out of line and resort to even harsher punishment if they threaten her honor and her marriage. Yet Alda will go to great lengths to protect the people she loves—something anyone can relate to.

The language you use is remarkably clear and easy to follow. Is this style something that comes naturally to you, as a copy editor and former journalist?

Author Kim Rendfeld

Author Kim RendfeldIt’s something I learned through journalism, and it has become natural to me. Time and space constraints taught me to get to the point. Maturing as a writer made me care more about the readers understanding the story than showing off my cleverness.

I also had to unlearn some habits. News writing is an objective report that allows both sides to tell their stories and lets the readers make their own conclusions. By nature, it’s distant. Fiction is intimate. You want the readers to feel your characters’ joys and sorrows. You want to manipulate sympathy and emotion.

Did your placing in the quarterfinals for the Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award in 2011 assist in attracting a publisher?

It might have. Placing in the quarterfinals and getting a positive review of the unedited manuscript from Publishers Weekly gave me a boost when I really needed it. The editor I mentioned earlier had rejected The Cross and the Dragon with no explanation, and I had ended my relationship with my agent, who had given up on me. I was not sure of what to do next, but I knew I needed to do something different than the approaches that had failed so far. With nothing to lose, I entered ABNA.

The Publishers Weekly review gave me an endorsement I could use to promote the book as long as I did not make major changes to the novel and specified it was for the manuscript and not the final version. Agents didn’t seem to notice, but the Fireship Press editor who read my manuscript did.

My experience with ABNA gave me something else as important as the endorsement: the confidence to keep trying.

~

I'd like to thank Kim for taking the time to answer my questions. The Cross and the Dragon was published by Fireship Press (a specialist publisher for nautical and historical fiction and nonfiction) in in July at $23.95 in trade pb or $7.50 as an ebook. Visit Kim online at kimrendfeld.com or at her blog, http://kimrendfeld.wordpress.com/.

Published on September 19, 2012 05:00

September 15, 2012

A Canadian historical fiction showcase, part 3

Based on my site stats, some of my most popular posts are those which focus on Canadian historical fiction. Apparently there are many people out there seeking these books! It's been a year since I posted on this last, so here's the 3rd entry in an ongoing series that showcases recent and forthcoming historical novels from Canadian authors and published by Canadian presses. The settings include not just Canada, but the Civil War-torn United States, ancient Greece, and mid-19th century Paris. Part 1 and Part 2 can be found in the archive.

In this novel, based on the true story of a 1915 maritime disaster which inspired a song, a woman whose husband and brother-in-law were lost at sea looks for answers. From a small press based in Newfoundland. Flanker Press, August.

In this literary novel spanning the second half of the 20th century, a wife and mother from small-town Manitoba searches for personal meaning and her own path in life as traditional women's roles give way to modern feminism. HarperCollins Canada, September.

A friendship between a Union army surgeon and a mysterious soldier, formed during the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War, ties them together after the second man goes missing, possibly a victim of business rivalries in British Columbia's salmon industry some twenty years later. Brindle & Glass, September.

The three Van Goethem sisters are the focus of Buchanan's sophomore novel (after The Day the Falls Stood Still), set in the glittering world of ballet in 1870s and 1880s Paris. Marie van Goethem is best known as the model for Degas' statue Little Dancer. HarperCollins, Canada, January 2013, pictured first; also Riverhead US, January.

In this coming of age story, the bygone days of 1950s small-town New Jersey prove to be anything but nostalgic and secure. A family tragedy involving a teenage girl is observed from the outside - at least at first - by two other young women. Penguin Canada, July.

Here we have another angle on women's lives in the Canadian colony of New France. A young Jewish woman named Esther, newly arrived in Quebec harbor in 1738, aims to distract officials from her background by telling wondrous stories. Cormorant, July.

The story of two women, one the daughter of white homesteaders and the other from the Blackfoot Blood tribe, who share the love of the southern Alberta prairie in the mid-19th century. Second Story, October.

The sequel to Lyon's Writers' Trust-winning The Golden Mean focuses on Aristotle's daughter, Pythias, too intelligent for her own good in a world full of superstition, and her yearning to create her own life after her famous father's death. Random House Canada, September.

An elderly, ill Halifax woman confronts her past, revisiting her troubled history and haunting secrets from decades before; episodes take her back to 1930s Newfoundland and to elsewhere in the maritime provinces during the war years. Viking Canada, September.

An atmospheric, character-centered story of Quaker pioneer life set in the late 18th century, based on the author's genealogy, beginning when a Pennsylvania father trades a horse for a slave. McClelland and Stewart, September.

In this novel, based on the true story of a 1915 maritime disaster which inspired a song, a woman whose husband and brother-in-law were lost at sea looks for answers. From a small press based in Newfoundland. Flanker Press, August.

In this literary novel spanning the second half of the 20th century, a wife and mother from small-town Manitoba searches for personal meaning and her own path in life as traditional women's roles give way to modern feminism. HarperCollins Canada, September.

A friendship between a Union army surgeon and a mysterious soldier, formed during the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War, ties them together after the second man goes missing, possibly a victim of business rivalries in British Columbia's salmon industry some twenty years later. Brindle & Glass, September.

The three Van Goethem sisters are the focus of Buchanan's sophomore novel (after The Day the Falls Stood Still), set in the glittering world of ballet in 1870s and 1880s Paris. Marie van Goethem is best known as the model for Degas' statue Little Dancer. HarperCollins, Canada, January 2013, pictured first; also Riverhead US, January.

In this coming of age story, the bygone days of 1950s small-town New Jersey prove to be anything but nostalgic and secure. A family tragedy involving a teenage girl is observed from the outside - at least at first - by two other young women. Penguin Canada, July.

Here we have another angle on women's lives in the Canadian colony of New France. A young Jewish woman named Esther, newly arrived in Quebec harbor in 1738, aims to distract officials from her background by telling wondrous stories. Cormorant, July.

The story of two women, one the daughter of white homesteaders and the other from the Blackfoot Blood tribe, who share the love of the southern Alberta prairie in the mid-19th century. Second Story, October.

The sequel to Lyon's Writers' Trust-winning The Golden Mean focuses on Aristotle's daughter, Pythias, too intelligent for her own good in a world full of superstition, and her yearning to create her own life after her famous father's death. Random House Canada, September.

An elderly, ill Halifax woman confronts her past, revisiting her troubled history and haunting secrets from decades before; episodes take her back to 1930s Newfoundland and to elsewhere in the maritime provinces during the war years. Viking Canada, September.

An atmospheric, character-centered story of Quaker pioneer life set in the late 18th century, based on the author's genealogy, beginning when a Pennsylvania father trades a horse for a slave. McClelland and Stewart, September.

Published on September 15, 2012 10:42

September 10, 2012

Contest winner, and musings on review policies

I'm late in announcing the winner of my extra ARC for Suzanne Desrochers' Bride of New France. Congratulations to Tiffany, who also recommended Elizabeth George Speare's Calico Captive in her comment. I'll be in touch over email to get your address, and thanks for the book suggestion, too. Hope you'll enjoy the read!

Because I'm overwhelmed with ARCs, I've temporarily stopped accepting review copy and interview requests. I haven't begun to make a serious dent in the books I picked up at the ALA conference, and there are some books I've actually bought that I'd like to get to in the near future. (I reserve the right to solicit books from publishers myself, however.)

This isn't the first time I've closed submissions, and it's not an event I usually announce—my review policy always has up-to-date submissions info—but I'd be curious to get feedback from my fellow bloggers about a related issue. This blog's policy is very easy to find, and my contact details on the sidebar make clear reference to it, but it's become a source of increasing frustration that only a small percentage of the people who contact me about reviewing their book appear to have read it. If you have, and if you've taken the time to query about or mail me a book in one of my areas of interest, thank you! But this has become an all-too-rare event, alas.

For other book bloggers: Is this your experience, too?

For example: I frequently get queries about reviewing e-books. I own a Kindle, but I take a lot of notes as I read, along with page numbers, and I find that reviewing from print works better for me. Writing me a nastygram about this aspect of my review policy isn't going to impress me or show me the error of my ways. Likewise, sending me a 10mb pdf, along with a query advising me how much I'll enjoy reading so-and-so military novel, will result in an immediate referral to the trash bin. I receive several ginormous ebook files every week.

I continue to be baffled by the large number of queries addressing me as Susan, considering my first name is, um, right there in my email address, but that's another story.

My estimate is that 90% of the queries I've gotten are for novels that my policy excludes. In contrast, when I get a pitch letter that indicates the sender has read the policy, I pay close attention. (For the summer publicity intern who sent me an unsolicited ARC in July, citing my interest in early North American settings... I wish you'd stuck around another month to see that I reviewed the book you sent me. Your letter worked, and I hope another publisher hires you full time!) My time is limited, so I can't promise to get to absolutely everything I receive, but I'm grateful to those who take the time to read the directions. That's really all it takes.

Because I'm overwhelmed with ARCs, I've temporarily stopped accepting review copy and interview requests. I haven't begun to make a serious dent in the books I picked up at the ALA conference, and there are some books I've actually bought that I'd like to get to in the near future. (I reserve the right to solicit books from publishers myself, however.)

This isn't the first time I've closed submissions, and it's not an event I usually announce—my review policy always has up-to-date submissions info—but I'd be curious to get feedback from my fellow bloggers about a related issue. This blog's policy is very easy to find, and my contact details on the sidebar make clear reference to it, but it's become a source of increasing frustration that only a small percentage of the people who contact me about reviewing their book appear to have read it. If you have, and if you've taken the time to query about or mail me a book in one of my areas of interest, thank you! But this has become an all-too-rare event, alas.

For other book bloggers: Is this your experience, too?

For example: I frequently get queries about reviewing e-books. I own a Kindle, but I take a lot of notes as I read, along with page numbers, and I find that reviewing from print works better for me. Writing me a nastygram about this aspect of my review policy isn't going to impress me or show me the error of my ways. Likewise, sending me a 10mb pdf, along with a query advising me how much I'll enjoy reading so-and-so military novel, will result in an immediate referral to the trash bin. I receive several ginormous ebook files every week.

I continue to be baffled by the large number of queries addressing me as Susan, considering my first name is, um, right there in my email address, but that's another story.

My estimate is that 90% of the queries I've gotten are for novels that my policy excludes. In contrast, when I get a pitch letter that indicates the sender has read the policy, I pay close attention. (For the summer publicity intern who sent me an unsolicited ARC in July, citing my interest in early North American settings... I wish you'd stuck around another month to see that I reviewed the book you sent me. Your letter worked, and I hope another publisher hires you full time!) My time is limited, so I can't promise to get to absolutely everything I receive, but I'm grateful to those who take the time to read the directions. That's really all it takes.

Published on September 10, 2012 16:35

September 6, 2012

Book review: Beautiful Lies, by Clare Clark

An enthralling novel about an elaborate fiction, Clare Clark's Beautiful Lies dazzles with its presentations of late Victorian London’s political and social occupations and a remarkable woman with something to hide.

An enthralling novel about an elaborate fiction, Clare Clark's Beautiful Lies dazzles with its presentations of late Victorian London’s political and social occupations and a remarkable woman with something to hide.Society in 1887 knows Maribel Campbell Lowe as the sophisticated, Chilean wife of Edward, the radical MP from Argyllshire. But when her mother contacts her out of the blue, and Edward’s fervent support of the working man attracts a sensationalist newspaper editor’s attention, she worries they will be ruined.

A wonderful creation, Maribel gradually earns readers’ empathy. She realizes exposure of her Yorkshire roots would be devastating socially and to Edward’s already shaky career, yet she can’t help reaching back to touch her past.

Though strongly paced and laced with suspense, the novel focuses on how Maribel’s deception shapes her character and interactions. Her unusual marriage (Edward knows some of her background) and warm relationship with her family-oriented best friend are well portrayed.

Their milieu springs to life with its stylish cultural ambience and socialist protests, and the city’s latest obsessions—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and the burgeoning art of photography—have similar shades of artifice. An unpredictable, historically authentic take on how we all carry secrets.

Beautiful Lies will be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on September 18th (hb, $26.00, 512pp). It appeared in June from Harvill Secker in the UK (hb, £12.99), with identical cover art. This review originally appeared in the August issue of Booklist; I wrote it up as a starred review.

Having read Clark's Savage Lands for this site two years ago – a novel about the Louisiana colony of New France, rather than the Canadian one from Suzanne Desrochers' novel – I approached this one with some trepidation. (For me, Savage Lands started out quite dry.) I needn't have worried. It's one of my favorite books so far this year.

Published on September 06, 2012 18:02

September 4, 2012

My progress with the Chunkster Challenge

(Thanks to Vicki Nesting, who called my attention to this all-too-appropriate graphic)

Earlier this year I decided to take up the Chunkster Challenge, setting my goal at Plump Primer level, which means six chunksters of 450pp or higher. Well... (gulp) it's only September, but it appears I've met my goal. In fact, I've met it twice and then some.

Just to recap, here's my list of chunky reading thus far, in order:

(1) Elliot Perlman, The Street Sweeper

(2) Rosie Thomas, The Kashmir Shawl

(3) Curtis Bill Pepper, Leonardo: A Biographical Novel - see Booklist review at end of linked page

(4) Rebecca Gablé, The Settlers of Catan

(5) Robert Lyndon, Hawk Quest

(6) Michelle Moran, Madame Tussaud

(7) Beatriz Williams, Overseas

(8) Kate Forsyth, Bitter Greens

(9) Clare Clark, Beautiful Lies - excellent book, I'll post the review shortly

(10) Adriana Trigiani, The Shoemaker's Wife

(11) Ken Follett, Winter of the World - for review out around the publication date. At over 900pp, this should count double.

(12) Barbara Erskine, Lady of Hay - reread, for discussion with the author at HNS Conference London

(13) Elizabeth Chadwick, The Greatest Knight - ditto!

Whew! No wonder my wrists are tired. I also want to acknowledge having read Amanda Coplin's The Orchardist, Enid Shomer's The Twelve Rooms of the Nile, and Selden Edwards' The Lost Prince, which are sitting back and teasing me with their almost-but-not-quite 448pp length. Could they not have printed two more pages in these books so I could make it sixteen? Is that too greedy of me??

I haven't totaled up the page count. The year isn't yet over, and there may be more.

Published on September 04, 2012 18:05

August 31, 2012

Book review: Bride of New France, by Suzanne Desrochers

Suzanne Desrochers' Bride of New France takes an unvarnished look at the lives of the filles du roi ("king's daughters"), young women sent from France to populate its colony in Canada in the 1660s and 1670s. While not easy to like, heroine Laure Beauséjour embodies the determination and self-interest required of those who found themselves forced to endure a harsh, unforgiving land. She learns from childhood on that if she doesn't put herself first, nobody else will.

Suzanne Desrochers' Bride of New France takes an unvarnished look at the lives of the filles du roi ("king's daughters"), young women sent from France to populate its colony in Canada in the 1660s and 1670s. While not easy to like, heroine Laure Beauséjour embodies the determination and self-interest required of those who found themselves forced to endure a harsh, unforgiving land. She learns from childhood on that if she doesn't put herself first, nobody else will.As a girl, Laure is torn from her street-performer father's arms by Louis XIV's officials, an episode which gains her immediate sympathy points. The next scene, set some years later, shows her distrust of another person's obvious suffering and steals those points right back from her. Desrochers illuminates both sides of Laure’s character throughout the book, making readers wary but fascinated observers of her fate.

Growing up in the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, a notorious home for destitute, criminal, insane, and loose women, Laure is fortunate to find herself in the Sainte-Claire dormitory, where she and other "bijoux" (jewels) are trained in lace-making. After she makes the mistake of complaining to the king about their poor conditions and bad food, her dreams of becoming a seamstress to the nobility are dashed. She is told she’ll be one of 100 orphans and widows sent to New France in Canada to marry a colonist, become his helpmate, and bear French children for the realm. What she feels about this is unimportant.

Laure’s tale is spliced into three segments, organized in essence as follows: Paris and the traumatic ocean voyage to Québec; her journey to the primitive town of Ville-Marie, “the last settlement before forest completely takes over”; and her marriage to an ill-mannered coureur de bois who leaves her behind in their cabin during a rough winter with only a pig for company. While the novel isn’t quite 300 pages long, Laure's constantly changing experiences give it almost the feel of an epic.

Unlike at the Salpêtrière, Laure isn’t a prisoner in her new home, but as midwife/innkeeper Madame Rouillard tells her, “The price we pay for freedom is that we have to live here.” This beautifully described country, ruled by the fur trade and the seasons, abounds with wildlife, and members of the Algonquin and Iroquois tribes both support and threaten the colonists. Laure had already attracted unwanted attention by her unorthodox behavior aboard ship, which didn't endear her to the other women. (Given what happens to those closest to her, the distance they keep from one another is probably to their benefit.) Her friendship and more with an Iroquois man who helps her survive makes her even more of an outcast. She is strong-minded, though, even in her impracticality. She insists on embroidering elegant Parisian-style dresses even after being told how useless they are in New France.

Although it may not be the best choice for those who need to emotionally connect with their protagonists, Bride of New France reveals an important chapter in the history of North America, especially from the female viewpoint, and is full of absorbing social history. It’s easy to see why it became a Canadian bestseller. The ramshackle town of Ville-Marie would later become known as Montréal, and the stories of its earliest pioneers are worth knowing. The conclusion demands a sequel, and fortunately, per Publishers Marketplace, one is in the works.

Bride of New France was published by Norton in the US in August at $24.95 (hardcover, 293pp, including author's note). Penguin Canada reprinted it in trade paperback at $16.00 Canadian in January.

A contest in honor of my 700th post! I had already bought the Canadian edition when an ARC arrived unsolicited from Norton, so I have an extra copy up for grabs. If you'd like this practically new ARC to be yours, leave a comment on this post for a chance to win it. Open internationally; deadline Friday, September 7th.

Published on August 31, 2012 17:00

August 28, 2012

Guest post from Jenny Barden: Drake's First Great Enterprise - the Tragedy behind the Triumph

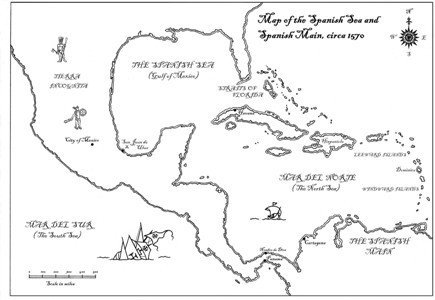

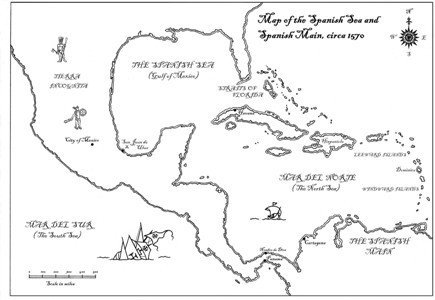

I'm happy to welcome Jenny Barden to the blog. Her debut novel Mistress of the Sea, published on Thursday by Ebury/Random House UK, is described as "an epic, romantic swash-buckling adventure set at the time of Francis Drake." It begins in Plymouth, England, in the year 1570, as Ellyn Cooksley stows away aboard Drake's expedition ship the Swan, disguised as a cabin boy, and begins an adventurous and life-changing journey to the New World.

Jenny is also the coordinator of the 2012 Historical Novel Society conference, to be held in London in a month's time, and I'm pleased she was able to take time from her schedule to compose such a detailed and informative post! The photographs included below are Jenny's, taken on her travels, and the map of the region is her composition as well.

~

Drake's First Great Enterprise - the Tragedy behind the Triumph

by Jenny Barden

It's easy to think of a daring escapade such as Drake's attack on the Spanish 'Silver Train' in 1573 as a rip-roaring adventure and overlook the suffering which lay behind it and the cost in lives lost. But Drake's success came at a heavy price, indeed it was born of tragedy, and tragedy dogged the enterprise right up until the moment he left Panama for Plymouth with his fabulous haul in booty.

It's easy to think of a daring escapade such as Drake's attack on the Spanish 'Silver Train' in 1573 as a rip-roaring adventure and overlook the suffering which lay behind it and the cost in lives lost. But Drake's success came at a heavy price, indeed it was born of tragedy, and tragedy dogged the enterprise right up until the moment he left Panama for Plymouth with his fabulous haul in booty.

What motivated Drake in his first venture against the Spanish, and for the rest of his life right up until the defeat of the Spanish Armada and beyond, was a desire for vengeance for what he saw as the treachery which led to the rout of John Hawkins' fleet at San Juan de Ulúa in 1568. Hundreds of English mariners were killed in this fiasco when the Spanish reneged on their truce and launched a surprise attack on Hawkins' ships while they were at anchor undergoing repairs following a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. Also lost were the hostages held by the Spanish as surety for the truce, and the Master of the Queen's flagship, Robert Barrett, a brilliant seaman and Drake's cousin, who was seized after a parley. Most of the English ships were destroyed or overrun, including the flagship along with those left on her, amongst them was Hawkins' nephew, Paul, who was only a boy.

Map of the Spanish Sea and Spanish Main, 1570. Click to see larger version

Map of the Spanish Sea and Spanish Main, 1570. Click to see larger version

All these captives were destined for long imprisonment, some for forced labour, and others for cruel death after examination by the Inquisition. Robert Barrett was eventually burnt at the stake. Many more men died later of starvation or at the hands of Indians when they were put ashore from the overcrowded Minion, the largest of only two ships to escape, and even then, when the Minion eventually limped back home, most of the men left aboard were desperately sick, those who had not died of thirst or hunger on the way. The other ship to escape was the tiny Judith and that was captained by a young seaman called Francis Drake. It was his first command of any significance.

Drake later wrote of the scars this episode left:

Fort San Lorenzo at Portobelo, built after Drake's

Fort San Lorenzo at Portobelo, built after Drake's

raid on Nombre de Dios and his attack on the

Silver Train 'As there is a general vengeance which secretly pursueth the doers of wrong and suffereth them not to prosper, albeit no man of purpose empeach them, so is there a particular indignation, engrafted in the bosom of all that are wronged, which ceaseth not seeking by all means possible to redress or remedy the wrong received.'

This is how Drake described the desire for vengeance which drove him in his enterprise to seize the Silver Train. He later presented this account to Queen Elizabeth I on New Year's Day, 1593.* He never forgot the men who were lost at San Juan de Ulúa, and as reports of the fate of the captives filtered back to England, his bitterness only intensified.**

Drake was a driven man when he embarked on his plan to strike at the Spanish bullion supply from the New World as it was conveyed overland across the isthmus of Panama. He had undertaken two reconnaissance voyages and he had determined that the weak link in Spain's source of wealth from Peru was the point at which the treasure could not be protected by an armada, when it was on land at the poorly defended Caribbean port of Nombre de Dios, or in transit by mule train from the City of Panama through the rainforest clad mountains. But pinpointing the treasure while it was being moved about proved to be a mission fraught with difficulty.

The Las Cruces Trail - an extension of

The Las Cruces Trail - an extension of

the Camino Real, the Royal RoadDrake's first raid on Nombre de Dios in July 1572 left him seriously injured with a ball in his leg and without any spoils. His men took the town but could not break into the treasure house before a tropical storm, and heavy bleeding from Drake's wound, put an end to the attempt. Most probably there was no bullion in the city at that time because the treasure was only shipped overland from Panama after the armada from Seville had arrived in Cartagena, and only in the dry season (December to April) when the Royal Road was passable.*** But Drake did not know this - not then.

Months of frustration followed. Drake attacked shipping and settlements along the north coast of Panama all the way from the Chagres river to Cartagena but captured nothing of any great value. In one of the skirmishes his younger brother, John, was killed, shot in the stomach and no doubt dying in agony. Drake had achieved little apart from stirring up a hornets' nest. The Spanish were hot on his heels when he holed up at a secret island base in the 'Cativas', in what is now the San Blas archipelago.

A coral island in the San Blas Archipelago, known as 'the Cativas' in Drake's time

A coral island in the San Blas Archipelago, known as 'the Cativas' in Drake's time

Here, Drake's men had built a stronghold on a coral island which they named Fort Diego after the Cimaroon (a runaway African slave) who had joined Drake as his ally (and was to serve him for much of his life). Months later, this place was renamed Slaughter Island because over a third of Drake's men lost their lives there - struck down by a mysterious disease they could not name or understand. Almost certainly that disease was the 'black vomit' or yellow fever. Amongst the victims was another of Drake's younger brothers, Joseph, who died in Drake's arms.

At this point Drake must have been close to despair, but he rallied his men (reduced from seventy-three to just over thirty) and, with the help of the Cimaroons, set out across county to attack the Silver Train near the City of Panama along the Royal Road. This also ended in failure when a Spanish outrider spotted one of Drake's men (reportedly drunk) and sounded the alarm causing the bulk of the convoy to double back. When Drake led his weary men back across the isthmus this was probably his lowest point. For all the ordeals he and his men had been through, for the loss of so many, including the death of his two brothers, he had nothing to show but cargoes of little worth and a catalogue of near misses and failures. His career thus far had been close to disastrous.

A view of the Panama shore near Nombre de Dios

A view of the Panama shore near Nombre de Dios

To their fellow crewmen who had been left behind, those returning empty handed with Drake seemed 'as men strangely changed,' they recounted later*, '...and indeed our long fasting and sore travail might somewhat forepine and waste us; but the grief we drew inwardly, for that we returned without that gold and treasure we hoped for did no doubt show her print and footseps in our faces.' These were broken men; but Drake never gave up. The fortuitous arrival of French Huguenot privateers led by Guillaume Le Testu, a distinguished cartographer and explorer, provided Drake with the manpower he needed to have one final attempt on the Silver Train and seizing a fortune, this time near Nombre de Dios.

The masts of the Golden Hinde

The masts of the Golden Hinde

(reconstruction)In the critical foray only fifteen Englishmen took part, along with twenty Frenchmen and around forty Cimaroons - but what a triumph those men achieved! On 1st April 1573, Drake and his followers managed to capture a Silver Train of around 190 mules carrying almost 30 tons in silver and around half a ton of gold. Their difficulty then was carrying such a weight in treasure away, but eventually they managed to get back to their ships with most of the gold.****

Yet tragedy struck again at the very moment of Drake's victory. Captain Le Testu was felled by a blast of hailshot into his stomach, and his injuries were so severe he could not hope to make an escape. After burying most of the treasure, Drake had little choice but to leave Le Testu behind. The Spanish later found the French captain and exhibited his decapitated head in the market place in Nombre de Dios. They also tortured one of the mariners that Drake had left with Le Testu into revealing where the bulk of the treasure was buried. Drake must have mourned Le Testu's end; he was a man of singular talents who had become Drake's firm friend.

When Drake finally returned with a fortune to a hero's welcome in Plymouth, he left many brave men behind.

In my book, Mistress of the Sea, I have tried not to forget them.

~

Jenny Barden's Mistress of the Sea will be published tomorrow, 30 August 2012, by Ebury Press, Random House. It will be released first in hardback and trade paperback in the UK with the traditional paperback to follow.

Jenny Barden's Mistress of the Sea will be published tomorrow, 30 August 2012, by Ebury Press, Random House. It will be released first in hardback and trade paperback in the UK with the traditional paperback to follow.

The book is available through Amazon UK and other online bookshops, as well as bookstores throughout the UK. Find it on Goodreads as well.

More about Jenny can be found on her website: http://www.jennybarden.com.

~

Notes:

* compiled from the reports of the crew by Drake's preacher, Philip Nichols, later published as Sir Francis Drake Revived in 1626

** remarkably, some of these captives escaped or won their freedom and eventually returned to England with amazing stories of endurance and fortitude. Job Hortop, gunner, was marooned, marched to the City of Mexico, tried, imprisoned, sent to Seville to answer the Inquisition, condemned to serve as a galley slave for 12 years, survived to be sold into servitude, escaped, and finally returned to England after 23 years

*** there's a piece about the Royal Road, el Camino Real, here: http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.co.uk/2012/08/el-camino-real-path-worn-through-time.html

**** for more about Drake's escape with the booty there's an article here: http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.co.uk/2012/07/carrying-away-booty-drakes-attack-on.html

Jenny is also the coordinator of the 2012 Historical Novel Society conference, to be held in London in a month's time, and I'm pleased she was able to take time from her schedule to compose such a detailed and informative post! The photographs included below are Jenny's, taken on her travels, and the map of the region is her composition as well.

~

Drake's First Great Enterprise - the Tragedy behind the Triumph

by Jenny Barden

It's easy to think of a daring escapade such as Drake's attack on the Spanish 'Silver Train' in 1573 as a rip-roaring adventure and overlook the suffering which lay behind it and the cost in lives lost. But Drake's success came at a heavy price, indeed it was born of tragedy, and tragedy dogged the enterprise right up until the moment he left Panama for Plymouth with his fabulous haul in booty.

It's easy to think of a daring escapade such as Drake's attack on the Spanish 'Silver Train' in 1573 as a rip-roaring adventure and overlook the suffering which lay behind it and the cost in lives lost. But Drake's success came at a heavy price, indeed it was born of tragedy, and tragedy dogged the enterprise right up until the moment he left Panama for Plymouth with his fabulous haul in booty.What motivated Drake in his first venture against the Spanish, and for the rest of his life right up until the defeat of the Spanish Armada and beyond, was a desire for vengeance for what he saw as the treachery which led to the rout of John Hawkins' fleet at San Juan de Ulúa in 1568. Hundreds of English mariners were killed in this fiasco when the Spanish reneged on their truce and launched a surprise attack on Hawkins' ships while they were at anchor undergoing repairs following a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. Also lost were the hostages held by the Spanish as surety for the truce, and the Master of the Queen's flagship, Robert Barrett, a brilliant seaman and Drake's cousin, who was seized after a parley. Most of the English ships were destroyed or overrun, including the flagship along with those left on her, amongst them was Hawkins' nephew, Paul, who was only a boy.

Map of the Spanish Sea and Spanish Main, 1570. Click to see larger version

Map of the Spanish Sea and Spanish Main, 1570. Click to see larger versionAll these captives were destined for long imprisonment, some for forced labour, and others for cruel death after examination by the Inquisition. Robert Barrett was eventually burnt at the stake. Many more men died later of starvation or at the hands of Indians when they were put ashore from the overcrowded Minion, the largest of only two ships to escape, and even then, when the Minion eventually limped back home, most of the men left aboard were desperately sick, those who had not died of thirst or hunger on the way. The other ship to escape was the tiny Judith and that was captained by a young seaman called Francis Drake. It was his first command of any significance.

Drake later wrote of the scars this episode left:

Fort San Lorenzo at Portobelo, built after Drake's

Fort San Lorenzo at Portobelo, built after Drake's raid on Nombre de Dios and his attack on the

Silver Train 'As there is a general vengeance which secretly pursueth the doers of wrong and suffereth them not to prosper, albeit no man of purpose empeach them, so is there a particular indignation, engrafted in the bosom of all that are wronged, which ceaseth not seeking by all means possible to redress or remedy the wrong received.'

This is how Drake described the desire for vengeance which drove him in his enterprise to seize the Silver Train. He later presented this account to Queen Elizabeth I on New Year's Day, 1593.* He never forgot the men who were lost at San Juan de Ulúa, and as reports of the fate of the captives filtered back to England, his bitterness only intensified.**

Drake was a driven man when he embarked on his plan to strike at the Spanish bullion supply from the New World as it was conveyed overland across the isthmus of Panama. He had undertaken two reconnaissance voyages and he had determined that the weak link in Spain's source of wealth from Peru was the point at which the treasure could not be protected by an armada, when it was on land at the poorly defended Caribbean port of Nombre de Dios, or in transit by mule train from the City of Panama through the rainforest clad mountains. But pinpointing the treasure while it was being moved about proved to be a mission fraught with difficulty.

The Las Cruces Trail - an extension of

The Las Cruces Trail - an extension of the Camino Real, the Royal RoadDrake's first raid on Nombre de Dios in July 1572 left him seriously injured with a ball in his leg and without any spoils. His men took the town but could not break into the treasure house before a tropical storm, and heavy bleeding from Drake's wound, put an end to the attempt. Most probably there was no bullion in the city at that time because the treasure was only shipped overland from Panama after the armada from Seville had arrived in Cartagena, and only in the dry season (December to April) when the Royal Road was passable.*** But Drake did not know this - not then.

Months of frustration followed. Drake attacked shipping and settlements along the north coast of Panama all the way from the Chagres river to Cartagena but captured nothing of any great value. In one of the skirmishes his younger brother, John, was killed, shot in the stomach and no doubt dying in agony. Drake had achieved little apart from stirring up a hornets' nest. The Spanish were hot on his heels when he holed up at a secret island base in the 'Cativas', in what is now the San Blas archipelago.

A coral island in the San Blas Archipelago, known as 'the Cativas' in Drake's time

A coral island in the San Blas Archipelago, known as 'the Cativas' in Drake's time Here, Drake's men had built a stronghold on a coral island which they named Fort Diego after the Cimaroon (a runaway African slave) who had joined Drake as his ally (and was to serve him for much of his life). Months later, this place was renamed Slaughter Island because over a third of Drake's men lost their lives there - struck down by a mysterious disease they could not name or understand. Almost certainly that disease was the 'black vomit' or yellow fever. Amongst the victims was another of Drake's younger brothers, Joseph, who died in Drake's arms.

At this point Drake must have been close to despair, but he rallied his men (reduced from seventy-three to just over thirty) and, with the help of the Cimaroons, set out across county to attack the Silver Train near the City of Panama along the Royal Road. This also ended in failure when a Spanish outrider spotted one of Drake's men (reportedly drunk) and sounded the alarm causing the bulk of the convoy to double back. When Drake led his weary men back across the isthmus this was probably his lowest point. For all the ordeals he and his men had been through, for the loss of so many, including the death of his two brothers, he had nothing to show but cargoes of little worth and a catalogue of near misses and failures. His career thus far had been close to disastrous.

A view of the Panama shore near Nombre de Dios

A view of the Panama shore near Nombre de DiosTo their fellow crewmen who had been left behind, those returning empty handed with Drake seemed 'as men strangely changed,' they recounted later*, '...and indeed our long fasting and sore travail might somewhat forepine and waste us; but the grief we drew inwardly, for that we returned without that gold and treasure we hoped for did no doubt show her print and footseps in our faces.' These were broken men; but Drake never gave up. The fortuitous arrival of French Huguenot privateers led by Guillaume Le Testu, a distinguished cartographer and explorer, provided Drake with the manpower he needed to have one final attempt on the Silver Train and seizing a fortune, this time near Nombre de Dios.

The masts of the Golden Hinde

The masts of the Golden Hinde (reconstruction)In the critical foray only fifteen Englishmen took part, along with twenty Frenchmen and around forty Cimaroons - but what a triumph those men achieved! On 1st April 1573, Drake and his followers managed to capture a Silver Train of around 190 mules carrying almost 30 tons in silver and around half a ton of gold. Their difficulty then was carrying such a weight in treasure away, but eventually they managed to get back to their ships with most of the gold.****

Yet tragedy struck again at the very moment of Drake's victory. Captain Le Testu was felled by a blast of hailshot into his stomach, and his injuries were so severe he could not hope to make an escape. After burying most of the treasure, Drake had little choice but to leave Le Testu behind. The Spanish later found the French captain and exhibited his decapitated head in the market place in Nombre de Dios. They also tortured one of the mariners that Drake had left with Le Testu into revealing where the bulk of the treasure was buried. Drake must have mourned Le Testu's end; he was a man of singular talents who had become Drake's firm friend.

When Drake finally returned with a fortune to a hero's welcome in Plymouth, he left many brave men behind.

In my book, Mistress of the Sea, I have tried not to forget them.

~

Jenny Barden's Mistress of the Sea will be published tomorrow, 30 August 2012, by Ebury Press, Random House. It will be released first in hardback and trade paperback in the UK with the traditional paperback to follow.

Jenny Barden's Mistress of the Sea will be published tomorrow, 30 August 2012, by Ebury Press, Random House. It will be released first in hardback and trade paperback in the UK with the traditional paperback to follow.The book is available through Amazon UK and other online bookshops, as well as bookstores throughout the UK. Find it on Goodreads as well.

More about Jenny can be found on her website: http://www.jennybarden.com.

~

Notes:

* compiled from the reports of the crew by Drake's preacher, Philip Nichols, later published as Sir Francis Drake Revived in 1626

** remarkably, some of these captives escaped or won their freedom and eventually returned to England with amazing stories of endurance and fortitude. Job Hortop, gunner, was marooned, marched to the City of Mexico, tried, imprisoned, sent to Seville to answer the Inquisition, condemned to serve as a galley slave for 12 years, survived to be sold into servitude, escaped, and finally returned to England after 23 years

*** there's a piece about the Royal Road, el Camino Real, here: http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.co.uk/2012/08/el-camino-real-path-worn-through-time.html

**** for more about Drake's escape with the booty there's an article here: http://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.co.uk/2012/07/carrying-away-booty-drakes-attack-on.html

Published on August 28, 2012 22:00

August 25, 2012

From Southeast Asia to South America...

I seek out novels set in distant, unfamiliar places. If I read about a new work of historical fiction that takes place in a locale few others have written about, I'm greatly encouraged to pick it up.

I seek out novels set in distant, unfamiliar places. If I read about a new work of historical fiction that takes place in a locale few others have written about, I'm greatly encouraged to pick it up.After spending the last week visiting Shanghai, Vietnam, and Cambodia with The Map of Lost Memories, I decided to turn to Annamaria Alfieri's Invisible Country, a historical mystery set in the landlocked South American country of Paraguay in 1868.

If you know nothing about the War of the Triple Alliance, in which the combined forces of Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil nearly destroyed Paraguay in the mid-19th century, you won't be alone. I hadn't either. No worries for potential readers, though, because Alfieri fills in the historical background with confidence and authority. This devastating military conflict seeps through every page of her novel and affects the choices made by her characters, from impoverished villagers to their well-meaning priest to the cruel, half-mad dictator Francisco Solano López himself.

With only seven of its men left living, the village of Santa Caterina is at risk of dying out. Concerned about its future, Padre Gregorio gives his congregation some shocking advice in his Sunday sermon. To repopulate the country, he grants the women permission to get pregnant outside of marriage. The thoughts of several excited females turn immediately to Ricardo Yotté, who is handsome, wealthy, and a close ally of López. Alas, unfortunately for their hopes, the padre finds Yotté's body in the belfry shortly thereafter.

López's beautiful mistress Eliza Lynch, an Irish-born adventuress and former Parisian courtesan, had requested that Yotté hide Paraguay's national treasury, and his death may relate to that. The gold and jewels have mysteriously gone missing. The villagers know that López's local Comandante will want a scapegoat for Yotté's murder. Nearly everyone hated Yotté, and it's up to them to find the killer before one of them gets the blame. Liaisons and secrets abound, and some are more dangerous than others.

The perspective moves among the varied cast, including the village midwife, her maimed husband, their attractive daughter, a devout parishioner, and even the woman known as La Lynch. While privileged and comfortably distant from her people's suffering, she is depicted not as a malicious political mastermind but as an intelligent woman aiming to keep her country and children safe not only from Paraguay's enemies but from her increasingly paranoid consort. (Charismatic Eliza could easily command a historical novel on her own, and has... to mixed reviews.)

This isn't a traditional amateur detective novel, since no one person takes the lead in the investigations. The atmosphere feels realistically tense, but I didn't find the murder mystery subplot all that suspenseful. Rather, the impetus driving the story lies in whether Santa Caterina's likeable and peaceable people will be able to save themselves and prevent even more tragedy. Their determination to rise above their losses invites readers' sympathy and admiration from the very start.

Annamaria Alfieri's Invisible Country was published by Minotaur in July at $25.99 (hardcover, 302pp + historical note).

Published on August 25, 2012 15:00

August 22, 2012

An interview with Kim Fay, author of The Map of Lost Memories

A few months after I'd read and reviewed Kim Fay's The Map of Lost Memories for Booklist, we connected through Goodreads. Since I enjoyed the novel so much (here's my review if you missed it), I was especially pleased that she was willing to do an interview for my site.

A few months after I'd read and reviewed Kim Fay's The Map of Lost Memories for Booklist, we connected through Goodreads. Since I enjoyed the novel so much (here's my review if you missed it), I was especially pleased that she was willing to do an interview for my site. In addition to providing more details on her inspiration for the novel and her travels throughout Southeast Asia, Kim sent along some great images I'm including below: a vintage photo from her grandfather's travels in Shanghai and postcards of temple ruins from her personal collection.

And some more good news... she's working on a new novel set in the region, and she also has plans for a sequel to The Map of Lost Memories. A former independent bookseller, Kim lives in Los Angeles and makes frequent trips to the region she writes about. Her website is http://www.kimfay.net.

I hope you'll enjoy the interview!

How did you choose the timeframe for The Map of Lost Memories? Why 1925?

I’d love to take credit for choosing that time period, but I really feel that it chose me! When I was a young girl, my grandpa would tell my sister and me about his life as a sailor on the South China Sea in the early 1930s. My grandpa and I were extremely close, and as I grew up, his stories anchored that time and faraway places such as Shanghai in my imagination.

Then, when I was twenty-nine, I read Silk Roads about Andre and Clara Malraux, a young French couple who looted a Cambodian temple in the mid-1920s. Their story provided the first spark for the plot of The Map of Lost Memories. While I researched their experiences further, I realized that 1925 (rather than my grandpa’s early 1930s) perfectly suited the novel. Colonialism was at its heyday in Asia; China’s fledgling Communist party was experiencing a pivotal moment with the death of Sun Yat-sen; just to travel in a foreign land was an adventure in and of itself; and the ethics of art acquisition and ownership were murky, at best.

The novel takes place in a kind of golden era (at least for a certain group of people), before the Great Depression, the atrocities of WWII, and the Communist takeover of China. Given all of these elements, I can’t see another time period in which the book could have taken place.

Old Shanghai, photo taken by the author's grandfather

Old Shanghai, photo taken by the author's grandfather One of the things that struck me while reading is that it's not your typical exotic treasure hunt, with the depth it provides into the Khmer civilization, both ancient and 20th century. What drew you into learning more about Cambodia's history?

When I began writing The Map of Lost Memories, exploring Cambodia’s complex Khmer civilization was secondary to telling the story of Irene Blum searching for a set of scrolls believed to contain the lost history of the Khmer. But I knew that I couldn’t just read a book and throw out a few facts and be done with it. And as often happens when I’m researching, one divine nugget of information leads to another, which leads to another, and so on. The more I read, the more fascinated I became.

While the lost scrolls in my novel are fictional, the premise they support is not—in 1925 very little was known about the rise and demise of the ancient Khmer civilization. Even now there are conflicting theories and missing pieces of information. But back then, the fate of the Khmer was a genuine mystery. This was intriguing in and of itself. Then I visited the Angkor Wat temples for the first time. I was blown away, and I knew I wanted to share as much as I could about the Khmer civilization with readers.

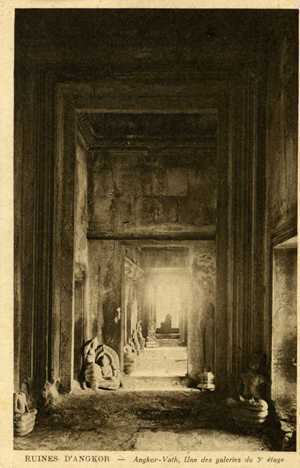

A deserted hallway in Cambodia's Angkor Wat temple in the 1920s.

A deserted hallway in Cambodia's Angkor Wat temple in the 1920s. As for my interest in the 20th-century Khmer, this grew out of the four years I spent living in Vietnam. It shocked me, a certain expatriate sense of entitlement that existed in the region even in the 1990s, and I found myself wondering about the effect this attitude must have had in the 1920s when the colonialists held all the power and the locals held none—a local population, in Cambodia’s case, that was once one of the world’s greatest civilizations. I wish I could give a more succinct answer to this question. I can only finish by saying that the more my characters’ stories became enmeshed in their journey to discover the lost history of Cambodia, the more Cambodia rose up as its own character asking that I tell its story too.

Simone Merlin is a mass of contradictions; her knowledge of the Khmer is impressive and valuable, but between her fragility, drug addiction, and sympathy for the Communists, among other things, she brings trouble with her everywhere. I wasn't sure if I admired her or felt sorry for her, or even liked her much at times, but she intrigued me, and that's the most important thing. Where did her character originate?

It’s interesting how strongly readers react to Simone. No one—and I do mean no one—likes her, and she has even stood in the way of some people liking the novel. She was inspired by Clara Malraux, even though after reading Clara’s memoirs I had the impression that she was a woman along for the ride, standing by her man. I wanted Simone to be more than that, but a spark is all it takes for a character to ignite and take on a life of her own. Simone definitely had a life of her own. No matter how I tried to corral her and write her as a character who was, to put it nicely, somewhat reasonable, she constantly defied me by taking drugs, lying, and manipulating, often just because it suited her at the time. There were so many moments in the book when I wanted to shake her and tell her to get her act together. But if she had done that, then she wouldn’t have been Simone Merlin.

How do you go about researching things like illegal art trafficking and temple-robbing, especially from the viewpoint of would-be robbers?

My research on this aspect of the novel began before I realized I was researching. After reading Silk Roads, I tracked down Clara Malraux’s memoirs and Andre Malraux’s The Royal Way, a fictitious account of an expedition to find a lost temple in Cambodia. Because Clara and Andre had actually looted a temple, they both offered authentic perspectives. What was most interesting to me was how justified they both felt in taking a seven-piece bas relief (weighing approximately a thousand pounds) from the temple of Banteay Srei.

From the Malraux’s accounts I felt that I had a basic foundation for my characters’ attitudes, and I began in-depth research, reading everything I could online from museum archives and old art and archaeology magazines, and checking out books from the library. There are some terrific volumes on the subject, including Pillaging Cambodia: The Illicit Traffic in Khmer Art; Museum of the Missing: A History of Art Theft; Loot! The Heritage of Plunder; and Plundered Past.

An abandoned Khmer temple in the Cambodian jungle in the 1920s.

An abandoned Khmer temple in the Cambodian jungle in the 1920s.This was one of those research paths that sucked me in and sidetracked me for a long time, because I felt that I needed to understand more than just illegal art trafficking; I needed to understand the art world in general, especially in the post-WWI 1920s. So the aforementioned research led me to books such as Merchants of Art: 1880-1960 Eighty Years of Professional Collecting, which led me to subcategories such as Russian Art & American Money and The Lost Fortune of the Tsars. One particular treasure of a book that I discovered in all of this was An Illuminated Life, the story of Belle da Costa Greene, who was J.P. Morgan’s librarian and a formidable art expert at a time when art was simply not a woman’s world. With all of this swirling around in my head, I wrote pages and pages on art and plunder that never made it into the novel, but I feel all of the research and tucked-away-in-a-drawer writing was invaluable because it gave me a foundation on which I could build my characters’ motives

One of the memorable pieces of advice that Irene's mentor Henry Simms tells her is that "The one thing to remember about an adventure is that if it turns out the way you expect it to, it has not been an adventure at all." This could, of course, be a tagline for the novel itself, with its unexpected twists. During your travels through Asia, what unplanned adventures did you run into?

Although I started traveling to Southeast Asia (trips to Thailand, Singapore, Bali, and Borneo) when I was twenty-two, my first unplanned adventure was moving there when I was twenty-nine. It had never once crossed my mind to move to Vietnam. But in 1995, after I graduated from a course on teaching English as a foreign language, I was offered a job there.

Without thinking about it, I took it, and then came the next surprise—the moment I stepped off the plane, I fell madly in love with the country. I still can’t explain that instantaneous flare of passion I felt, but it has not wavered in the past seventeen years.

The third notable “unplanned adventure” was writing The Map of Lost Memories. I already had a novel in the works when I moved to Vietnam—a satire inspired by my recent reading of British fiction—but after living in Vietnam for a few months, I knew in my heart that this was the part of the world I wanted to write about. I dumped the novel-in-progress and started writing The Map of Lost Memories, discovering not only the first story I felt meant to tell, but also, finally, finding my own voice. When I first got on that plane to Vietnam, I could not have imagined that Southeast Asia would give me my vocation and provide me with the opportunity to have my dreams of being a published novelist come true.

Did working as an independent bookseller give you insight into the writing or publication process for your own novel?

Author Kim FayDuring the five years that I worked at the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, I read every book I could get my hands on, and it was here that I discovered how many different ways a story could be told. Because I had access not only to books, but to the collective wealth of knowledge that is one of the greatest values of an indie bookstore, I was introduced to books that taught me how to achieve specific results in my own writing. Of particular influence were Graham Greene, Michael Ondaatje, and Penelope Lively, all of whom are incredible craftspeople.

Author Kim FayDuring the five years that I worked at the Elliott Bay Book Company in Seattle, I read every book I could get my hands on, and it was here that I discovered how many different ways a story could be told. Because I had access not only to books, but to the collective wealth of knowledge that is one of the greatest values of an indie bookstore, I was introduced to books that taught me how to achieve specific results in my own writing. Of particular influence were Graham Greene, Michael Ondaatje, and Penelope Lively, all of whom are incredible craftspeople.As for learning about the publishing side of the process, I worked at Elliott Bay before the rise of chain bookstores and the birth of Amazon, so the publishing world was very different from how it is today. It was smaller and more personal. Of course publishing houses were businesses, but the overall attitude was less corporate. Because of that, (and because of my work as an editor for the small independent publisher ThingsAsian Press), I was expecting a fairly impersonal experience when my agent sold my novel to Random House in 2011. But I got lucky with an editor whose roots in the publishing world are as deep as mine are in the bookselling world. My editor/writer relationship was wonderfully old school, right down to my editor’s notes—not typed into “track changes” in email documents, but written in pencil on manuscript pages that would arrive at my house by way of good old-fashioned U.S. mail.

I'm eager to learn more about your novel-in-progress, which you wrote is about "an American culinary anthropologist born in Vietnam in 1937." How did you get interested in exploring Vietnamese culture through its cuisine? Can you reveal any more about how this novel will connect up with The Map of Lost Memories?

I lived in Vietnam for four years without having a deep interest in the cuisine, other than loving to eat it. I was absorbed by other aspects of my life then, and it wasn’t until I moved back to the U.S. that I began to realize how much the food meant to my relationship with the country and its people. The more I thought about it while going about my life in Los Angeles—which included a growing interest in food and cooking in general—the more I spent time reading about Vietnamese food. As with my research for my novel, one thing led to another, and I emailed my publisher at ThingsAsian Press and told him I wanted to take a five-week culinary tour of the country and write a book about it. I didn’t know what would result, and had no idea that I would become so consumed by the subject of how food affects and reflects the culture and history of Vietnam. After the trip, I spent three more years writing and doing additional in-depth research before finally publishing Communion: A Culinary Journey Through Vietnam.

Because of my interest in Vietnamese food, I’ve been asked why food does not play a role in The Map of Lost Memories. The first reason is that the main character, Irene, is obsessed with one thing: finding the lost history of the Khmer. I felt that anything I wrote about food—because once I start I can’t stop—would derail scenes and take away from the momentum of the plot. The second reason is that I knew I could incorporate my love of food into my next book, an untitled novel about an American woman who is born in Vietnam in 1937; raised in the country, she becomes a culinary anthropologist, and along with studying Vietnam’s imperial cuisine, she also feeds homesick soldiers. This, though, is the backdrop for the suspense storyline, based on the murder of the American woman’s best Vietnamese friend. As in The Map of Lost Memories, this new novel will twine all of the characters’ together, and there will be plenty of secrets unveiled along the way.

Because of my interest in Vietnamese food, I’ve been asked why food does not play a role in The Map of Lost Memories. The first reason is that the main character, Irene, is obsessed with one thing: finding the lost history of the Khmer. I felt that anything I wrote about food—because once I start I can’t stop—would derail scenes and take away from the momentum of the plot. The second reason is that I knew I could incorporate my love of food into my next book, an untitled novel about an American woman who is born in Vietnam in 1937; raised in the country, she becomes a culinary anthropologist, and along with studying Vietnam’s imperial cuisine, she also feeds homesick soldiers. This, though, is the backdrop for the suspense storyline, based on the murder of the American woman’s best Vietnamese friend. As in The Map of Lost Memories, this new novel will twine all of the characters’ together, and there will be plenty of secrets unveiled along the way.As for its relationship to The Map of Lost Memories, there will be only passing mentions of characters. But I want those small threads to be there, because I hope that with these two books and the next (a true sequel to The Map of Lost Memories), I will be able to give readers a comprehensive picture of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos (formerly Indochina) in the pre-1975 twentieth century.

~

The Map of Lost Memories was published on August 21st by Ballantine at $26.00 (hb, 336pp). In the UK, the publisher is Hodder & Stoughton (£13.99, hb, 336pp).

Published on August 22, 2012 04:00