Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 127

August 20, 2012

Book review: The Map of Lost Memories, by Kim Fay

Kim Fay’s extraordinary first novel has everything great historical adventure fiction should—a strikingly original setting, exhilarating plot twists, and a near-impossible quest. It stands out even more with its one-of-a-kind characters and sensitivity to colonialism’s harsh effects on the local populace, although its gutsy protagonist doesn’t initially share this concern.

Kim Fay’s extraordinary first novel has everything great historical adventure fiction should—a strikingly original setting, exhilarating plot twists, and a near-impossible quest. It stands out even more with its one-of-a-kind characters and sensitivity to colonialism’s harsh effects on the local populace, although its gutsy protagonist doesn’t initially share this concern.In 1925, Irene Blum arrives in Shanghai with a map and a mission: to venture deep into Cambodia to find ten copper scrolls containing the as-yet-unknown history of the vanished Khmer civilization. Upset after losing a museum curatorship to a male colleague, Irene needs the scrolls to fulfill her ambitions in the art world.

On her mentor’s advice, she recruits the help of Simone Merlin, whose linguistic and temple-robbing knowledge is counterbalanced by her drug addiction and abusive, Communist-supporting husband. Others join them, and their quest becomes an odyssey of personal discovery that tests Irene’s physical and psychological endurance.

Every word of this evocative literary expedition feels deliberately chosen, each phrase full of meaning. From the murky Shanghai underworld, in which information is traded like currency, to the isolated Cambodian jungle, whose overheated air is thick with mistrust, Fay brilliantly imagines a singular heroine who forges her own path through an unfamiliar country.

The Map of Lost Memories is published tomorrow by Ballantine at $26.00 (hb, 336pp). In the UK, the publisher is Hodder & Stoughton (£13.99, hb, 336pp). This is one of three starred reviews I wrote up for Booklist recently, and it appeared in their August issue.

Coming on Wednesday: An interview with Kim Fay.

Published on August 20, 2012 05:00

August 16, 2012

An interview with Elizabeth Caulfield Felt, author of Syncopation: A Memoir of Adèle Hugo

Musically gifted and passionate, yet born into an era that grants women few opportunities, Victor Hugo's daughter Adèle chooses to pursue life on her own terms... and meets a world that isn't ready for her.

Musically gifted and passionate, yet born into an era that grants women few opportunities, Victor Hugo's daughter Adèle chooses to pursue life on her own terms... and meets a world that isn't ready for her.Elizabeth Caulfield Felt's Syncopation is a fictional autobiography written in a nontraditional style. Adèle Hugo tells her story in the third person, mingling true events with imagined reminiscences and occasional wishful thinking. In a less creative writer's hands, the deliberate blurring of history and fiction might be confusing or off-putting, but here it's the perfect vehicle for imagining a character like Adèle, a woman who delights in sparking outrage. The snippets in which she breaks away from her account to speak with her sister, Didine, explain her reasons for wanting to reinterpret parts of her life.

As Adèle grows to adulthood in mid-19th-century Paris and Guernsey, she has several love affairs, ones that would shock her family if they knew. She refuses to marry any of her suitors, though, because it would mean giving up her freedom.

Readers who have seen François Truffaut's well-known 1975 film The Story of Adèle H. (L'Histoire d'Adèle H.) may think of Adèle Hugo as a beautiful, intense woman whose mind became unhinged due to unrequited love. I won't give away more of the plot of Syncopation, other than that her depiction here is somewhat different but just as psychologically complex. In the following interview, I asked Elizabeth Caulfield Felt about her writing inspiration, research, and characterizations. Please read on!

You write in the acknowledgments that your starting point was Victor Hugo's poem "Demain dès l'Aube," which he wrote for his elder daughter, Léopoldine ("Didine" in the novel). What drew you away from their story and on to Adèle's?

Quite simply, Adèle's story is much more interesting. But without the poem, I never would have discovered Adèle.

I first read "Demain dès l'Aube" as a teenager. I hadn't known the history behind the poem, and so the end came as a complete surprise to me. Admittedly, this may have been because I struggled a little with the French and didn't pick up on clues for how the poem would end. "Demain dès l'Aube" led me to other works by Victor Hugo, and I fell in love with him—he wrote so beautifully; his work was so romantic. My senior year in college, I took a French class that required a research paper, and I chose Victor Hugo as my subject. Unfortunately, when I dug deeper into his life, I discovered his infidelities and his generally poor view of the abilities and intellect of women. I was left with a bad taste in my mouth for Victor Hugo. As for "Demain dès l'Aube," I still loved it but wished it had been written by someone else.

About twenty years later, I was asked if I had memorized any poems as a student, and, to my surprise, "Demain dès l'Aube" fell from my lips. I still wished it had been written by someone else, and I began pondering this question. What if someone else had written it? Who would that person be? I knew a little about Adèle, having researched Victor and having seen François Truffaut's film about her. Once I started looking into the story of her life, I was blown away. Why aren't there hundreds of historical novels about her, like there are about Anne Boleyn? I was afraid someone would publish her story before I got a chance—but, as far as I know, Syncopation is the first historical novel about Adèle Hugo.

What sources did you find the most useful or persuasive in helping you flesh out Adèle's character?

Leslie Smith Dow's wonderful biography of Adèle called Adèle Hugo: La Misérable, gave me the details of Adèle's life and an idea for her personality. After reading Dow, I discovered that Adèle's personal journals were published in 1968, edited/translated by Frances Vernor Guille. Adèle kept a journal for most of her life, and she wrote it in code—talk about fodder for a novelist! Once I began reading her diary, her character became real to me. I found every detail of her life fascinating and took piles of notes and attempted to drop all this enchanting minutiae into my novel. Finally, I realized that these details were messing up the story. Adèle's character had come to me. I knew what happened to her, so it was time to put the journals to the side and let the fictional Adèle talk.

The novel shows a wonderful sensitivity to the importance of music in Adèle's life; her talent for the piano is beautifully described. What is your own musical training? How does music influence your writing, or what you choose to write about?

I played the flute poorly for several years as a child, so I can read music, but I am not musical. I cannot sing in tune or clap to a beat. My husband grew up in a musical family, and we decided that the same would be true for our children. When our first child turned three, we registered him for Suzuki violin lessons, changing my life and forming his. The Suzuki method for learning music is a way of life—the child practices every day, the parent helps, and specific musical pieces are listened to constantly. For the past thirteen years, I've been swimming in music.

My inability to be musical has given me a fascination with music and musicians, and so it is a topic I enjoy exploring. My other published novel is The Stolen Goldin Violin, a children's mystery (co-written with my family) about four Suzuki musicians.

The sections at the end of many chapters in which Adèle converses with her sister were fabulous. They transformed the book from a traditional historical novel into something much more complex; they had me thinking about the nature of fiction and memoir and the choices that writers make. How did you come up with this technique?

Adèle Hugo (1830-1915)

Adèle Hugo (1830-1915)credit: Philippe LandruTo be honest, I can't remember making the decision to create those Adèle and Didine conversations. I do know that when I first started writing Syncopation, I was thinking about how two people can experience the same event and remember it differently. One of the first scenes I wrote described a childhood event from three points of view: how Adèle remembered it, how Didine remembered it, and how her brother Toto remembered it. Their three memories were similar but different; each person understood what happened from their own egocentric point of view, noticing what was important to them as a child and ignoring the details that they didn't care about. The facts were the same, but the interpretations were vastly different. That scene didn't make the final version of Syncopation, but it helped to lay a thematic foundation for me.

I always knew that in my novel, Adèle's version of her life story was not going to be the one history gave her, but at the same time I wanted to remain true to the facts of her life, realizing that different interpretations are possible. When I began writing, and the character Adèle moved into my head, I found her very argumentative. She had a strong personality, and I found that she didn't care so much about the truth. I struggled with how much imagination I could use in a historical novel, and I wanted the reader to understand this struggle. I believe that the conversations between Didine and Adèle illustrate this. They help create a balance between fiction and fact, truth and memory.

Additionally, the conversations work as a sort of barometer of Adèle's sanity. In a way, the conversations became the backbone of the entire novel, something I hadn't planned in the beginning.

Adèle writes about the frustrating difference between her father's public persona and what he's truly like to live with. Did your own opinion about Victor Hugo change in the course of your research?

As I explained above, my early research gave me a strong negative opinion of him long before I wrote this book. Adèle and her father had a complicated relationship (as all family relationships are), and as Syncopation is Adèle's story, it gives readers a one-sided look at a difficult relationship. Strangely, as I wrote this story I found that I felt a little sorry for Victor and how negatively Adèle portrayed him. Still, I felt more sorry for Adèle. Victor Hugo was a great man in many ways, but he was not perfect, and his treatment of women, and Adèle in particular, shows this.

Cornerstone is a unique type of publishing house, and from what I've seen, the student staff have some really creative ideas. What were some of the most exciting or memorable parts of the publication process?

Elizabeth Caulfield FeltFor readers who don't know, Cornerstone Press is both a small press and a university course (English 349) offered at the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point. At the beginning of the semester, students read through the submitted manuscripts and vote on the one they will publish. The editing, design, marketing, sales strategy, etc, all happen in about four months.

Elizabeth Caulfield FeltFor readers who don't know, Cornerstone Press is both a small press and a university course (English 349) offered at the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point. At the beginning of the semester, students read through the submitted manuscripts and vote on the one they will publish. The editing, design, marketing, sales strategy, etc, all happen in about four months. Cornerstone was fabulous to work with. Because I was the only author, all of their energy was spent on me and my book. Not many authors get that kind of attention from a publisher. I'll admit I was skeptical about how much help students would be as editors. I teach part-time at the university, and I've seen the quality (or lack thereof) of student writing. I couldn't have been more wrong. The content editors caught some very embarrassing mistakes, and the line-editing was amazing. I feel like every awkward sentence I'd submitted was turned into poetry by the editing team. And the cover art! The design team's work is gorgeous. I couldn't be more pleased with the final result.

~

Thank you, Elizabeth!

Syncopation: A Memoir of Adèle Hugo was published by Cornerstone Press in April in trade paperback ($13.00, 235pp, including author's note). To purchase, see the

Published on August 16, 2012 16:43

August 13, 2012

Book review: Cascade, by Maryanne O'Hara

Have I mentioned the number of standout debut historicals appearing this August? Maryanne O'Hara's Cascade can be added to this growing list. Set primarily in small-town New England during the 1930s, it tells a gripping story about art; the impermanence of earthly things; and the importance, nonetheless, of creating a meaningful, memorable life.

Have I mentioned the number of standout debut historicals appearing this August? Maryanne O'Hara's Cascade can be added to this growing list. Set primarily in small-town New England during the 1930s, it tells a gripping story about art; the impermanence of earthly things; and the importance, nonetheless, of creating a meaningful, memorable life.There is a sense of carpe diem from the outset: the author establishes her characters and premise within the first few pages. By late 1934, the heyday of Cascade, Massachusetts, has passed. Formerly a classy summer resort town whose Shakespeare theater attracted Hollywood's brightest stars, it has fallen victim to the Depression. The crowds have vanished, having moved on to Lenox in the Berkshires, and rumors spread that Cascade may be flooded to create a water source for distant Boston.

Desdemona Hart Spaulding, an up-and-coming artist who had studied in Paris, was forced to return to Cascade when her family's fortunes vanished. She has married dull but reliable Asa, a man desperate to have children, to provide her and her ailing father with a roof over their heads. Dez passes her time in a state of numbing sameness: cooking Asa's meals, dreaming about reopening her father's playhouse, and reminiscing about the past while secretly tracking her fertile days to avoid getting pregnant. Like her art-school friend Abby advises her, "No babies means you can leave."

Her father dies months into her marriage, leaving Dez feeling desolate and stuck... until Jacob Solomon, a traveling salesman, starts stopping by to chat. Jacob is a fellow artist and kindred spirit for whom Dez feels an instant attraction, but Asa doesn't like him hanging around his wife.

The cast has been assembled; the scene is set. From this initial arrangement, one might expect a classic love triangle to play out amidst village drama. There is some of that, but it doesn't take into account the complexity of these characters – Dez in particular. She is hardly faultless (Jacob is Jewish, and despite their growing closeness, she doesn’t show much interest in his religion) but her desire to escape and join the New York art scene is palpable, especially knowing the roadblocks she faces.

Happily, Cascade doesn’t follow a predictable route. The plot moves with the authenticity of real life. Big cities have a habit of muscling in on the affairs of smaller places – this is universal – and when a Massachusetts Water Authority representative arrives to scope out Cascade for a possible reservoir site, tensions rise, and its residents start feeling the reverberations of anti-Semitism spreading throughout Europe and America. Dez’s talent gets noticed in a big way, too, leaving her with a difficult moral choice. (Not a spoiler; the jacket blurb reveals more than this.)

The 1930s ambiance is re-created perfectly, with its drugstore soda fountain, nosy phone operators, pin-curl hairstyles, and the stifling environment for women who resist the wifely ideal. Dez knows she couldn’t obtain a divorce without Asa’s permission.

O’Hara’s prose has a beautiful melancholy air:

Their once-fashionable resort town with its pleasant waters was looking more and more like the ghost valley that was invading dreams and even the pages of her sketchpad. She had done half a dozen studies: the drowning person’s blurred upward view from the bottom of a flooded place. The bleary, uncertain light. The smooth stones, long grasses, and someone struggling through thick river mud, Ophelia-like, trying to find a place to breathe.

Dez’s nostalgia for a bygone era vies with her strong desire for independence. When she finds a way of combining both with her paintings, the story truly begins to soar.

Cascade is framed around a historical incident, which lends it even more poignancy. When the Quabbin Reservoir was created in the 1930s, several central Massachusetts towns were disincorporated and flooded. For those people who can’t ever go home again, art and memory take on a critical significance – one of many themes explored in this excellent first novel.

Cascade is published by Viking in hardback on August 20th ($25.95 or $27.50 in Canada, 353pp). If the novel sounds like it might intrigue you, take a look at the trailer for Cascade. It’s among the best I've seen, combining images from the plot with an on-site author interview.

Published on August 13, 2012 07:00

August 11, 2012

Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction for 2012: Shortlist announced

The Langum Charitable Trust has announced a shortlist for the 2012 Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction.

The Langum Charitable Trust has announced a shortlist for the 2012 Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction. For the first half of 2012, the shortlisted titles are:

The Cove by Ron Rash, about a doomed love affair between a lonely young woman and a mysterious stranger in the North Carolina Appalachians during the World War I years; and

A Good Man by Guy Vanderhaeghe, about a man living in the borderlands between the American and Canadian West in the late 19th century as tensions between the U.S. government and Indians reach the boiling point.

The final shortlist, to be announced later this year, will cover novels published in July through December.

For more on the prize see the Langum Charitable Trust. To submit a novel for consideration, view the directions available at the site.

The prize is awarded annually to the "best book in American historical fiction that is both excellent fiction and excellent history." Past years' winners include Julie Otsuka's The Buddha in the Attic, Ann Weisgarber's The Personal History of Rachel DuPree, Edward Rutherfurd's New York, and Kathleen Kent's The Heretic's Daughter.

Published on August 11, 2012 05:00

August 8, 2012

Book review: The House of Serenades, by Lina Simoni

Based on the title and elegant cover, you may expect to find a quiet and unassuming tale of literary fiction, perhaps with an Italian lilt, within the pages of Lina Simoni's newest novel. If so, you'd have the setting right, but the message is far from gentle. Many scenes of high drama and class struggles unfold before the palazzina on Corso Solferino becomes known as the House of Serenades.

Based on the title and elegant cover, you may expect to find a quiet and unassuming tale of literary fiction, perhaps with an Italian lilt, within the pages of Lina Simoni's newest novel. If so, you'd have the setting right, but the message is far from gentle. Many scenes of high drama and class struggles unfold before the palazzina on Corso Solferino becomes known as the House of Serenades.In 1910 in the hills of the bustling port city of Genoa, a disturbing scandal has just hit one of its wealthiest, most prominent families. When lawyer Giuseppe Berilli begins receiving anonymous poison-pen letters, not even a painful back injury stops him from tracking down the sender. But strangely, in this place where everybody knows everyone else's dirty business, nobody seems to be talking.

Giuseppe's suspicions fall on several men from his past who he thinks would see him ruined, given the chance. He shares his thoughts with the police, which leads to the revelation of many unpleasant secrets which he, his family, and his associates had hoped were carefully concealed.

It takes gumption to give these people starring roles – Giuseppe and his elderly sister are both disagreeable snobs – but all of the characters, even the seemingly minor ones, have important tales to contribute as well. Despite her faults, it's hard not to root for Giuseppe's long-suffering wife, Matilda, who had been trapped into marriage because of a presumed indiscretion. The story's emotional center is the star-crossed romance between baker's son Ivano Bo, a talented mandolin player, and Caterina, the Berillis' golden-haired daughter, whose life had been cut tragically short.

The House of Serenades will suit readers who enjoy novels filled with passionate feelings and theatrical twists. To its credit, it has a consistently entertaining plot, and the sad plight of women in that day and age is an ever-present theme. Some historical novels take a nostalgic glance back at the past, but you won't find this here. Instead, it's a colorful, oftentimes heartbreaking look at social conflict, the misfortunes it can engender, and the strength and love required to overcome it.

The House of Serenades appeared from Moonleaf Publishing, a California-based small press, in June (trade pb, 314pp, $14.99).

Published on August 08, 2012 17:02

August 5, 2012

On Barbara Wood's The Divining, set in the 1st-century Roman Empire and beyond

Barbara Wood's newest historical, about a woman’s spiritual journey through the 1st-century Roman world, is a mixed effort. The segmented approach impedes the story’s flow, but she succeeds in illuminating a time in which Christianity hasn’t yet taken root and populates it with dynamic characters.

The Divining stands alone yet also works as the sequel to Soul Flame (1987), which followed a Roman healer named Selene. In 54 CE, Ulrika, Selene’s 19-year-old daughter, begins seeing mysterious visions that draw her away from Rome. She joins a caravan to Germania, her father’s homeland, in hopes of saving his people from a Roman ambush and learning more about her heritage. She falls in love with the caravan’s leader, Galician trader Sebastianus Gallus, although their romance must wait until their separate missions are over. As Ulrika travels on to Antioch and Babylon on her quest to control her gift, Sebastianus obtains orders from the despotic new emperor, Nero, to open diplomatic ties with distant China, a trip marked by deception.

The Divining stands alone yet also works as the sequel to Soul Flame (1987), which followed a Roman healer named Selene. In 54 CE, Ulrika, Selene’s 19-year-old daughter, begins seeing mysterious visions that draw her away from Rome. She joins a caravan to Germania, her father’s homeland, in hopes of saving his people from a Roman ambush and learning more about her heritage. She falls in love with the caravan’s leader, Galician trader Sebastianus Gallus, although their romance must wait until their separate missions are over. As Ulrika travels on to Antioch and Babylon on her quest to control her gift, Sebastianus obtains orders from the despotic new emperor, Nero, to open diplomatic ties with distant China, a trip marked by deception.

Oddly for a novel about a journey, little time is spent on the road; one would expect travel to be more complicated and arduous than it is here. Despite the narrative’s jumpiness, though, it provides a nice panoramic view of the era. “Deities, Ulrika realized, were as diverse and various as the people who worshipped them,” Wood writes, which captures the book’s greatest strength. The cultures Ulrika encounters are fascinating, and her openness to spiritual discovery means the reader approaches their beliefs – some ancient and others newly born – in a similar way at first. Everyone Ulrika meets has a tale worth hearing, and her story creatively intertwines with that of the earliest Christian saints.

For those who share the author’s wide-ranging interest in women’s lives through history, Turner has also reissued sixteen titles from her backlist, all with gorgeous covers (see on Amazon).

The Divining appeared from Turner Publishing in May at $26.95, or $29.95 in Canada (hb, 373pp). This review appeared first in August's Historical Novels Review. In looking through my review index, I discovered I'd reviewed her Woman of a Thousand Secrets, set in 14th-century Mesoamerica, almost exactly four years ago.

The Divining stands alone yet also works as the sequel to Soul Flame (1987), which followed a Roman healer named Selene. In 54 CE, Ulrika, Selene’s 19-year-old daughter, begins seeing mysterious visions that draw her away from Rome. She joins a caravan to Germania, her father’s homeland, in hopes of saving his people from a Roman ambush and learning more about her heritage. She falls in love with the caravan’s leader, Galician trader Sebastianus Gallus, although their romance must wait until their separate missions are over. As Ulrika travels on to Antioch and Babylon on her quest to control her gift, Sebastianus obtains orders from the despotic new emperor, Nero, to open diplomatic ties with distant China, a trip marked by deception.

The Divining stands alone yet also works as the sequel to Soul Flame (1987), which followed a Roman healer named Selene. In 54 CE, Ulrika, Selene’s 19-year-old daughter, begins seeing mysterious visions that draw her away from Rome. She joins a caravan to Germania, her father’s homeland, in hopes of saving his people from a Roman ambush and learning more about her heritage. She falls in love with the caravan’s leader, Galician trader Sebastianus Gallus, although their romance must wait until their separate missions are over. As Ulrika travels on to Antioch and Babylon on her quest to control her gift, Sebastianus obtains orders from the despotic new emperor, Nero, to open diplomatic ties with distant China, a trip marked by deception.Oddly for a novel about a journey, little time is spent on the road; one would expect travel to be more complicated and arduous than it is here. Despite the narrative’s jumpiness, though, it provides a nice panoramic view of the era. “Deities, Ulrika realized, were as diverse and various as the people who worshipped them,” Wood writes, which captures the book’s greatest strength. The cultures Ulrika encounters are fascinating, and her openness to spiritual discovery means the reader approaches their beliefs – some ancient and others newly born – in a similar way at first. Everyone Ulrika meets has a tale worth hearing, and her story creatively intertwines with that of the earliest Christian saints.

For those who share the author’s wide-ranging interest in women’s lives through history, Turner has also reissued sixteen titles from her backlist, all with gorgeous covers (see on Amazon).

The Divining appeared from Turner Publishing in May at $26.95, or $29.95 in Canada (hb, 373pp). This review appeared first in August's Historical Novels Review. In looking through my review index, I discovered I'd reviewed her Woman of a Thousand Secrets, set in 14th-century Mesoamerica, almost exactly four years ago.

Published on August 05, 2012 17:35

August 4, 2012

Bits and pieces

I've been delinquent in announcing a winner of the giveaway for Kathy Hepinstall's Blue Asylum, which ran through July 31st. Out of 48 entries, the number generator at Random.org selected #34 - Carol Kubala. Congratulations, Carol! I'll drop you a note to get your address. Hope you enjoy the book, and thanks to everyone who entered.

The reviews from August's Historical Novels Review have been posted - all 316 of them, plus a number of indie reviews which appear online only. Please take a look! I've been an editor with the HNR for the past dozen years, and August marks a personal anniversary; this is the 50th issue I've worked on. In addition, the year 2012 is the 15th anniversary for the Historical Novel Society, an event which will be celebrated in the next magazine issue and on the website.

Will anyone else be coming to the London HNS conference in September? It's selling out quickly, with 30-odd places remaining out of 300 total. I look forward to seeing old friends and meeting new ones there!

In addition, the Historical Novel Society's 5th North American conference, to be held in St. Petersburg, Florida, next June, has posted a call for proposals. If you're interested in speaking at the event, the deadline is August 15th.

For those of you who track forthcoming titles, if you're not already a fervent reader of Library Journal's Prepub Alert, you should be. Barbara Hoffert's July 9th post looks at seven historical fiction debuts with buzz which are coming out in January 2013.

Also of note is the Weekly Wishlist feature at Tanzanite's Castle Full of Books, which previews (among other things) Bernard Cornwell's newest Thomas of Hookton medieval adventure, 1356, and Edward Rutherfurd's millennia-spanning historical epic, Paris: The Novel. I'll be listing my own picks for upcoming seasons in due course.

The reviews from August's Historical Novels Review have been posted - all 316 of them, plus a number of indie reviews which appear online only. Please take a look! I've been an editor with the HNR for the past dozen years, and August marks a personal anniversary; this is the 50th issue I've worked on. In addition, the year 2012 is the 15th anniversary for the Historical Novel Society, an event which will be celebrated in the next magazine issue and on the website.

Will anyone else be coming to the London HNS conference in September? It's selling out quickly, with 30-odd places remaining out of 300 total. I look forward to seeing old friends and meeting new ones there!

In addition, the Historical Novel Society's 5th North American conference, to be held in St. Petersburg, Florida, next June, has posted a call for proposals. If you're interested in speaking at the event, the deadline is August 15th.

For those of you who track forthcoming titles, if you're not already a fervent reader of Library Journal's Prepub Alert, you should be. Barbara Hoffert's July 9th post looks at seven historical fiction debuts with buzz which are coming out in January 2013.

Also of note is the Weekly Wishlist feature at Tanzanite's Castle Full of Books, which previews (among other things) Bernard Cornwell's newest Thomas of Hookton medieval adventure, 1356, and Edward Rutherfurd's millennia-spanning historical epic, Paris: The Novel. I'll be listing my own picks for upcoming seasons in due course.

Published on August 04, 2012 08:25

August 2, 2012

A short review of Jennie Fields' The Age of Desire

August is here at last! Over the last few months, I've been busy reviewing eight historical novels scheduled to come out in August. While I don't often repost previously published material, I want to highlight some of these books here as their publication dates roll by—including Jennie Fields' new novel The Age of Desire, literary biographical fiction about Edith Wharton's mid-life love affair, and how it affected her relationship with her closest friend.

August is here at last! Over the last few months, I've been busy reviewing eight historical novels scheduled to come out in August. While I don't often repost previously published material, I want to highlight some of these books here as their publication dates roll by—including Jennie Fields' new novel The Age of Desire, literary biographical fiction about Edith Wharton's mid-life love affair, and how it affected her relationship with her closest friend.The reviews I write for Booklist are exercises in concise writing. I have a limit of 175-200 words!

Edith Wharton lived in the glittering world of the moneyed elite she wrote about, although she never experienced her characters’ lustful motivations herself until she met American journalist Morton Fullerton. Fields bases her perceptive novel on Wharton’s own diaries and letters. By 1907, Edith is tired of husband Teddy’s gaucheness and depressive episodes and succumbs to the charms of Fullerton, whom she encounters at a French dinner party. It’s hard not to pity her—he is obviously a cad—but she displays a touching vulnerability, opening herself to passion for the first time at 45, and her anguish at Fullerton’s inconstancy is deeply felt. Readers also observe them from the viewpoint of Anna Bahlmann, the literary secretary and longtime friend Edith sometimes carelessly takes for granted. Gentle Anna doesn’t approve of the affair, which drives her and Edith apart for a time. While the novel concentrates more on the emotional than the intellectual sphere, it sheds welcome light on the little-known private life of a famous woman and her closest relationships in early-twentieth-century Europe and America.

For two more (slightly longer) takes on the novel, see the Historical Novels Review and Unabridged Chick.

The Age of Desire is published in August 2012 by Pamela Dorman/Viking in hardcover (352pp, $27.95). In the UK, the publisher is Ebury Press. My review first published in Booklist's July 2012 issue; reprinted with permission.

Published on August 02, 2012 16:59

July 31, 2012

Guest post from Kathy Leonard Czepiel: When History Comes to Life

Did you know that at the end of the 19th century, New York's Hudson Valley was known as the violet capital of the world? I grew up not far from the region, but this is a bit of history I'd never come across before. Kathy Leonard Czepiel, author of A Violet Season (Simon & Schuster, July 2012, $15.00), has contributed a thought-provoking essay about her research, and about the moments when we realize how history has touched us personally. Welcome, Kathy! For additional stops on her blog tour, visit http://a-violet-season.blogspot.com.

When History Comes to Life I grew up in the 1970s on a spur of the old Albany Post Road that had been cut off from the highway when it was straightened. There, off the beaten path, is a hamlet that dates to the eighteenth century and is still a little bit older and quieter than the world around it. At one end of what was known as Old Post Road, I grew up in the Victorian parsonage of the church where my father was the minister. At the other end, among the many neighbors we knew, lived Mr. and Mrs. Brenzel, an older couple who were members of our church. In my child’s memory, they are both smiling, friendly people. They must have enjoyed children, though they had none of their own.

I grew up in the 1970s on a spur of the old Albany Post Road that had been cut off from the highway when it was straightened. There, off the beaten path, is a hamlet that dates to the eighteenth century and is still a little bit older and quieter than the world around it. At one end of what was known as Old Post Road, I grew up in the Victorian parsonage of the church where my father was the minister. At the other end, among the many neighbors we knew, lived Mr. and Mrs. Brenzel, an older couple who were members of our church. In my child’s memory, they are both smiling, friendly people. They must have enjoyed children, though they had none of their own.

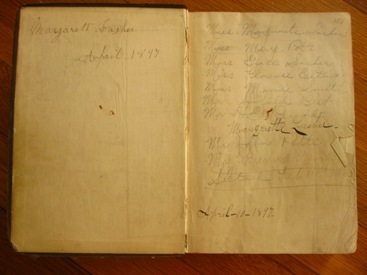

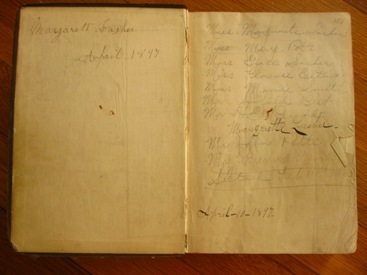

I mention the Brenzels because Mrs. Brenzel played an important but entirely unintended role in the research of my novel, A Violet Season. The novel is set in 1898 on a violet farm in my native Hudson Valley and tells the story of a fictional family, the Fletchers, and their struggles to save their share of the family farm. In the course of my research, I wanted to know what hymns might have been sung in the church at that time, so my father loaned me an 1897 hymnal. Its brown cover was embossed with a chancel design and the pages retained a decorative red edging, but the cover of its spine was missing. Most of the hymns were surprisingly unfamiliar, and difficult to read because the music was separated from the lyrics. Inside the front cover was a penciled list of names, which my father speculated might have been the names of the members of the choir. Among them was the name “Miss Grace Lasher.”

Grace Lasher was born in 1884 and grew up at the Eureka Hotel on the Village Green, a small, triangular piece of land at one end of Old Post Road. A 1901 photograph shows her standing on the hotel steps with her sister Margaret beside her, a hand resting on Grace’s shoulder. Their parents, dressed in black, sit in chairs at the foot of the steps, and standing to their right are their sister Fannie, her husband and their little daughter in a smocked dress with ribbons in her hair. At the age of 21, Grace fell in love with and married 54-year-old neighbor Will Knickerbocker and moved across the street to his family homestead, which he had recently repurchased. By all accounts, they were happily married until his death in 1922. He was 70, and she was 38. Three years later, in 1925, she married Raymond Brenzel, who was fifteen years her junior, and became Mrs. Brenzel. I knew her through most of her eighties; she died when I was eight years old.

The moment when I realized who “Grace Lasher” in that century-old hymnal was, I also realized for the first time what I was doing. I wasn’t writing “historical fiction.” I was writing about people just like the people I had known, people whose lives had begun in the nineteenth century, but intersected with my own. My characters, though creations of my own imagination, were no longer from a distant, imagined time. They were part of my time.

It is like this for readers as well. We sometimes imagine we are reading fiction from a distance, peeking through a keyhole at a world beyond us. In truth, we are all living in the same world, part of one continuous time that overlaps with our own. Holding that hymnal in my hands reminds me of that fact. It reminds me that I am not just playing a make-believe game. I am telling the story of not only a place, but of a time that in many ways belongs to me.

~

Kathy Leonard Czepiel

Kathy Leonard Czepiel

(credit: Chris Volpe)Kathy Leonard Czepiel is the author of A Violet Season, a historical novel set on a Hudson Valley violet farm on the eve of the twentieth century. She is the recipient of a 2012 creative writing fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and her short fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals including Cimarron Review, Indiana Review, CALYX, Confrontation, and The Pinch. Czepiel teaches in the First-Year Writing Program at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut, where she lives with her husband and their two daughters.

Learn more about her at www.kathyleonardczepiel.com, like her on Facebook, or follow her on Twitter at @KLCzepiel.

When History Comes to Life

I grew up in the 1970s on a spur of the old Albany Post Road that had been cut off from the highway when it was straightened. There, off the beaten path, is a hamlet that dates to the eighteenth century and is still a little bit older and quieter than the world around it. At one end of what was known as Old Post Road, I grew up in the Victorian parsonage of the church where my father was the minister. At the other end, among the many neighbors we knew, lived Mr. and Mrs. Brenzel, an older couple who were members of our church. In my child’s memory, they are both smiling, friendly people. They must have enjoyed children, though they had none of their own.

I grew up in the 1970s on a spur of the old Albany Post Road that had been cut off from the highway when it was straightened. There, off the beaten path, is a hamlet that dates to the eighteenth century and is still a little bit older and quieter than the world around it. At one end of what was known as Old Post Road, I grew up in the Victorian parsonage of the church where my father was the minister. At the other end, among the many neighbors we knew, lived Mr. and Mrs. Brenzel, an older couple who were members of our church. In my child’s memory, they are both smiling, friendly people. They must have enjoyed children, though they had none of their own.I mention the Brenzels because Mrs. Brenzel played an important but entirely unintended role in the research of my novel, A Violet Season. The novel is set in 1898 on a violet farm in my native Hudson Valley and tells the story of a fictional family, the Fletchers, and their struggles to save their share of the family farm. In the course of my research, I wanted to know what hymns might have been sung in the church at that time, so my father loaned me an 1897 hymnal. Its brown cover was embossed with a chancel design and the pages retained a decorative red edging, but the cover of its spine was missing. Most of the hymns were surprisingly unfamiliar, and difficult to read because the music was separated from the lyrics. Inside the front cover was a penciled list of names, which my father speculated might have been the names of the members of the choir. Among them was the name “Miss Grace Lasher.”

Grace Lasher was born in 1884 and grew up at the Eureka Hotel on the Village Green, a small, triangular piece of land at one end of Old Post Road. A 1901 photograph shows her standing on the hotel steps with her sister Margaret beside her, a hand resting on Grace’s shoulder. Their parents, dressed in black, sit in chairs at the foot of the steps, and standing to their right are their sister Fannie, her husband and their little daughter in a smocked dress with ribbons in her hair. At the age of 21, Grace fell in love with and married 54-year-old neighbor Will Knickerbocker and moved across the street to his family homestead, which he had recently repurchased. By all accounts, they were happily married until his death in 1922. He was 70, and she was 38. Three years later, in 1925, she married Raymond Brenzel, who was fifteen years her junior, and became Mrs. Brenzel. I knew her through most of her eighties; she died when I was eight years old.

The moment when I realized who “Grace Lasher” in that century-old hymnal was, I also realized for the first time what I was doing. I wasn’t writing “historical fiction.” I was writing about people just like the people I had known, people whose lives had begun in the nineteenth century, but intersected with my own. My characters, though creations of my own imagination, were no longer from a distant, imagined time. They were part of my time.

It is like this for readers as well. We sometimes imagine we are reading fiction from a distance, peeking through a keyhole at a world beyond us. In truth, we are all living in the same world, part of one continuous time that overlaps with our own. Holding that hymnal in my hands reminds me of that fact. It reminds me that I am not just playing a make-believe game. I am telling the story of not only a place, but of a time that in many ways belongs to me.

~

Kathy Leonard Czepiel

Kathy Leonard Czepiel(credit: Chris Volpe)Kathy Leonard Czepiel is the author of A Violet Season, a historical novel set on a Hudson Valley violet farm on the eve of the twentieth century. She is the recipient of a 2012 creative writing fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and her short fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals including Cimarron Review, Indiana Review, CALYX, Confrontation, and The Pinch. Czepiel teaches in the First-Year Writing Program at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut, where she lives with her husband and their two daughters.

Learn more about her at www.kathyleonardczepiel.com, like her on Facebook, or follow her on Twitter at @KLCzepiel.

Published on July 31, 2012 05:00

July 27, 2012

On Carlos Ruiz Zafón's The Prisoner of Heaven, and my approach to reading series

Sometimes I like reading novels in series out of order. Curiously, this ties in with my interest in historical fiction. Not only do I enjoy following characters and their adventures in their proper chronological progression, but I also like starting with the newest volume and learning later about the characters' past histories – which sit waiting for me to discover them via earlier books. When I do this, I know there will be references I won't pick up on, but if the author has done a good job, they'll intrigue rather than perplex me.

Sometimes I like reading novels in series out of order. Curiously, this ties in with my interest in historical fiction. Not only do I enjoy following characters and their adventures in their proper chronological progression, but I also like starting with the newest volume and learning later about the characters' past histories – which sit waiting for me to discover them via earlier books. When I do this, I know there will be references I won't pick up on, but if the author has done a good job, they'll intrigue rather than perplex me.Despite the fact that many friends name The Shadow of the Wind as an all-time-favorite, I hadn't read anything by Carlos Ruiz Zafón until now. A note at the beginning of The Prisoner of Heaven describes it as an "independent, self-contained tale" and that "each individual instalment in the Cemetery of Forgotten Books series can be read in any order." In other words, starting with volume three is fair game, so that's what I did.

The novel opens in a place where any bibliophile would feel comfortable. It's Christmastime in Barcelona of 1957, where Daniel Sempere lives with his beautiful wife Bea, his new baby son, and his father. Times are tough, and the Sempere & Sons bookshop needs to bring in more business. When an elderly stranger with a heavy limp drops in to buy an expensive illustrated copy of The Count of Monte Cristo, however, Daniel finds his troubles have only begun. The visitor has a message for Daniel's good friend Fermín Romero de Torres which he leaves inscribed in the book – and which has dark implications for Fermín, he of the normally jovial outlook and deliciously phrased ripostes. I love how Ruiz Zafón can present Fermín’s appearance in just a few words; who can resist knowing more about a funny guy whose “body seemed mostly composed of cartilage and attitude”?

Fermín’s backstory is exactly what the novel proceeds to reveal. This story-within-a-story is set toward the end of Spain’s Civil War, circa 1939, deep within Montjuïc Castle: a fortress overlooking Barcelona where political prisoners languish, die, and rot, forgotten by most, and with no realistic hope of escape. With a setting out of a sinister nightmare, and a crafty, compelling plotline with a strong nod to Dumas, the pages essentially turn themselves. As they all speak amongst themselves in their dank, filthy cells, the personalities of Fermín and his fellow “tenants”– which include a novelist named David Martín – spring forth with grim, sarcastic humor. It’s a testament to the author’s storytelling prowess that I found my attention transfixed by these characters while simultaneously wanting to get the hell out of there.

That’s all I’ll say about what happens. Does the novel stand on its own? Well, yes and no. While The Prisoner of Heaven does tell a self-contained story, it begins amid a larger tale and doesn’t end at the end, either. (There will be a fourth novel; I’m not giving anything away by saying that.) As a short book with a swift-moving 278 pages, it feels very much like an interlude rather than the full experience. The “Cemetery of Forgotten Books” hinted at within the initial note is mentioned, although this mysterious place didn’t have anywhere near the impact on this newcomer I felt it would have, if I had read the The Shadow of the Wind and The Angel’s Game first.

If the point to my reading it was to whet my appetite for the earlier books, though, it did the trick. I'll be getting to them sooner now rather than later. I also can’t help but think how much fun this novel must have been to write, and to translate. (Lucia Graves' skillful translation is anything but stiff.) It’s a novel for those who love words, inventive turns of phrase, and literature as a whole.

The Prisoner of Heaven was published by Harper on July 13th at $25.99 in hardcover; in the UK, the publisher is Weidenfeld & Nicolson (£16.99).

Published on July 27, 2012 06:00