Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 131

April 6, 2012

Russia: A Novel Bibliography

I've been having such a good time reading over the comments people have submitted as part of my 6th anniversary giveaway. I wasn't intending to do a formal survey, but the responses have been giving me insights into what you enjoy most about the site and what you'd like to see more of. Thank you! Many people have mentioned the posts that focus on historical fiction trends, and here's a new one of these.

It used to be that Russian settings for historicals were few and far between, with some notable exceptions like Robert Alexander's Romanov thrillers, Edward Rutherfurd's comprehensive Russka, WWII-era suspense, and the occasional literary novel such as Daphne Kalotay's Russian Winter and Adrienne Sharp's The True Memoirs of Little K. One of my all-time favorite novels is Catherine Gavin's The Snow Mountain, an imagined story of Grand Duchess Olga, but it's long out of print.

In recent months, though, historicals set in Russia have been appearing in force. The story of the last Romanovs and their tragic end continues to be a favorite, but authors are also branching out to less familiar subjects and settings - all to readers' benefit.

Below are a dozen Russian-set historicals which were or will be published in North America between June 2011 and September 2012 - a wide variety of eras, personalities, and reading levels. For books not yet published, the covers are subject to change.

This first novel in the Katerina Trilogy for young adults blends historical fiction with romance and dark fantasy. A debutante attending finishing school in 1888 St. Petersburg has a secret talent for raising the dead, a power that she must develop and perfect if she's to help save the tsar and imperial family. Delacorte, January 2012.

Dean's The Madonnas of Leningrad was a book club favorite, and here she returns to Russia with an elegant take on the life of Xenia, a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church. Living during the reigns of Empresses Elizabeth and Catherine II, she was a strong-willed, devout woman whose purpose in life grew out of personal tragedy. Harper, August 2012.

In this sequel to The Siege, a young couple tries to forge a new life for themselves in Stalinist Leningrad in the early fifties. They get caught in a dangerous web of repression and grief when the husband, a doctor, is asked to treat the very ill son of a high-ranking official. Grove, September 2011.

This 3rd in the Inspector Pekkala historical suspense series (after Eye of the Red Tsar and Shadow Pass) takes place in 1939, when Russia approaches war with Germany. Pekkala, the tsar's former investigator, now works undercover for Stalin. His latest mission: return to Siberia, and the gulag where he was once prisoner, to find Nicholas II's lost-lost gold. Bantam, February 2012.

Harrison is best at taking snippets from history and transforming them into imaginative literary fiction. Enchantments takes place in familiar territory for Russophiles: 1917 St. Petersburg, just following the murder of mad monk Rasputin. A friendship springs up between Rasputin's daughter Maria, called Masha, and the young, doomed tsarevich. Random House, March 2012.

Americans will need to look north to Canada for Linda Holeman's (The Linnet Bird, etc) newest historical epic. In 1860s Russia, after kidnappers kill her husband and steal away her son, a distraught noblewoman fights to discover the boy's fate and bring him back. See if you can resist this beautiful cover. Random House Canada, July 2012.

Between Love and Honor is a new publication from AmazonCrossing, the retail giant's imprint for translated fiction, but French novelist Alexandra Lapierre isn't new to the US literary scene. Her novel Artemisia (2000), an international bestseller, looked at the life story of Italian renaissance painter Artemisia Gentileschi. Between Love and Honor, based on historical people, tells the story of a Muslim hostage who becomes a foster brother to Czar Nicholas's sons in 19th-century St. Petersburg. When he falls in love with a Russian noblewoman, he must choose between her and his Chechen heritage. AmazonCrossing, April 2012.

Sarah Miller's acclaimed novel of the four Russian grand duchesses who met their tragic fate in Ekaterinburg in 1918 comes with endorsements from well-known Romanov biographers. The story of Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia is retold in their own imagined voices, spanning the last four years of their lives. Atheneum, June 2011.

Mossanen's latest is a fantastical spin on the final days of the Romanovs as seen through the eyes of a member of their inner circle, a former orphan with second sight who becomes a close companion to the young tsarevich, Alexei. Aged 104 in 1991, Darya Borodina looks back on her long life and wonders what became of him, and if somehow he managed to survive. Sourcebooks, April 2012.

The tense paranoia of Stalinist Russia becomes its own character in Ryan's second historical thriller to star Captain Alexei Korolev, a cop with the Moscow Militia in the mid-1930s. A well-connected young woman has supposedly committed suicide, and her former lover, a bigwig security official, wants answers. I've read the first volume, The Holy Thief, which evoked the claustrophobia of the period extremely well. The UK title of this one is The Bloody Meadow. Minotaur, January 2012.

Moving away from both detective stories and the aristocracy, Susan Sherman's The Little Russian opens in 1903 in the Jewish village of Mosny in the Ukraine, or Little Russia. Berta Alshonsky sets aside her fond childhood memories of glittering Moscow to become a heroine for her people during the country's harsh pogroms. Counterpoint, February 2012.

Stachniak's newest historical novel follows Catherine the Great, Empress and Autocrat of all the Russias, during her unlikely rise to power. As an obscure German princess sent to marry the Russian imperial heir, she was never destined to rule herself. Her story is filtered through the eyes of Varvara, a lady in waiting who becomes Catherine's spy and views her transformation firsthand. I reviewed this for Booklist last year and loved it. A forthcoming sequel will continue telling Catherine's story, but from her point of view. Bantam, February 2012.

It used to be that Russian settings for historicals were few and far between, with some notable exceptions like Robert Alexander's Romanov thrillers, Edward Rutherfurd's comprehensive Russka, WWII-era suspense, and the occasional literary novel such as Daphne Kalotay's Russian Winter and Adrienne Sharp's The True Memoirs of Little K. One of my all-time favorite novels is Catherine Gavin's The Snow Mountain, an imagined story of Grand Duchess Olga, but it's long out of print.

In recent months, though, historicals set in Russia have been appearing in force. The story of the last Romanovs and their tragic end continues to be a favorite, but authors are also branching out to less familiar subjects and settings - all to readers' benefit.

Below are a dozen Russian-set historicals which were or will be published in North America between June 2011 and September 2012 - a wide variety of eras, personalities, and reading levels. For books not yet published, the covers are subject to change.

This first novel in the Katerina Trilogy for young adults blends historical fiction with romance and dark fantasy. A debutante attending finishing school in 1888 St. Petersburg has a secret talent for raising the dead, a power that she must develop and perfect if she's to help save the tsar and imperial family. Delacorte, January 2012.

Dean's The Madonnas of Leningrad was a book club favorite, and here she returns to Russia with an elegant take on the life of Xenia, a saint in the Russian Orthodox Church. Living during the reigns of Empresses Elizabeth and Catherine II, she was a strong-willed, devout woman whose purpose in life grew out of personal tragedy. Harper, August 2012.

In this sequel to The Siege, a young couple tries to forge a new life for themselves in Stalinist Leningrad in the early fifties. They get caught in a dangerous web of repression and grief when the husband, a doctor, is asked to treat the very ill son of a high-ranking official. Grove, September 2011.

This 3rd in the Inspector Pekkala historical suspense series (after Eye of the Red Tsar and Shadow Pass) takes place in 1939, when Russia approaches war with Germany. Pekkala, the tsar's former investigator, now works undercover for Stalin. His latest mission: return to Siberia, and the gulag where he was once prisoner, to find Nicholas II's lost-lost gold. Bantam, February 2012.

Harrison is best at taking snippets from history and transforming them into imaginative literary fiction. Enchantments takes place in familiar territory for Russophiles: 1917 St. Petersburg, just following the murder of mad monk Rasputin. A friendship springs up between Rasputin's daughter Maria, called Masha, and the young, doomed tsarevich. Random House, March 2012.

Americans will need to look north to Canada for Linda Holeman's (The Linnet Bird, etc) newest historical epic. In 1860s Russia, after kidnappers kill her husband and steal away her son, a distraught noblewoman fights to discover the boy's fate and bring him back. See if you can resist this beautiful cover. Random House Canada, July 2012.

Between Love and Honor is a new publication from AmazonCrossing, the retail giant's imprint for translated fiction, but French novelist Alexandra Lapierre isn't new to the US literary scene. Her novel Artemisia (2000), an international bestseller, looked at the life story of Italian renaissance painter Artemisia Gentileschi. Between Love and Honor, based on historical people, tells the story of a Muslim hostage who becomes a foster brother to Czar Nicholas's sons in 19th-century St. Petersburg. When he falls in love with a Russian noblewoman, he must choose between her and his Chechen heritage. AmazonCrossing, April 2012.

Sarah Miller's acclaimed novel of the four Russian grand duchesses who met their tragic fate in Ekaterinburg in 1918 comes with endorsements from well-known Romanov biographers. The story of Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia is retold in their own imagined voices, spanning the last four years of their lives. Atheneum, June 2011.

Mossanen's latest is a fantastical spin on the final days of the Romanovs as seen through the eyes of a member of their inner circle, a former orphan with second sight who becomes a close companion to the young tsarevich, Alexei. Aged 104 in 1991, Darya Borodina looks back on her long life and wonders what became of him, and if somehow he managed to survive. Sourcebooks, April 2012.

The tense paranoia of Stalinist Russia becomes its own character in Ryan's second historical thriller to star Captain Alexei Korolev, a cop with the Moscow Militia in the mid-1930s. A well-connected young woman has supposedly committed suicide, and her former lover, a bigwig security official, wants answers. I've read the first volume, The Holy Thief, which evoked the claustrophobia of the period extremely well. The UK title of this one is The Bloody Meadow. Minotaur, January 2012.

Moving away from both detective stories and the aristocracy, Susan Sherman's The Little Russian opens in 1903 in the Jewish village of Mosny in the Ukraine, or Little Russia. Berta Alshonsky sets aside her fond childhood memories of glittering Moscow to become a heroine for her people during the country's harsh pogroms. Counterpoint, February 2012.

Stachniak's newest historical novel follows Catherine the Great, Empress and Autocrat of all the Russias, during her unlikely rise to power. As an obscure German princess sent to marry the Russian imperial heir, she was never destined to rule herself. Her story is filtered through the eyes of Varvara, a lady in waiting who becomes Catherine's spy and views her transformation firsthand. I reviewed this for Booklist last year and loved it. A forthcoming sequel will continue telling Catherine's story, but from her point of view. Bantam, February 2012.

Published on April 06, 2012 18:30

April 1, 2012

Review and giveaway opportunity: Natasha Solomons, The House at Tyneford

By chance, this giveaway opportunity was offered to me by the publisher, Plume, just after I'd finished reading my own copy of Natasha Solomons' The House at Tyneford, so I thought I'd take it on and give you the chance to win one for yourself. Two copies are up for grabs. This contest is open to US and Canadian residents.

By chance, this giveaway opportunity was offered to me by the publisher, Plume, just after I'd finished reading my own copy of Natasha Solomons' The House at Tyneford, so I thought I'd take it on and give you the chance to win one for yourself. Two copies are up for grabs. This contest is open to US and Canadian residents.I'd posted about The House at Tyneford in one of my "women in WWII" roundups and bought a copy based on friends' and reviewers' recommendations. It didn't disappoint. It offers a perspective on the World War II years I hadn't seen before; the narrator is Elise Landau, a young woman from an upper-class Austrian Jewish family of artists. She is an outsider in several respects.

In 1938, to keep her safe from whatever may come, her parents send her to England, where she becomes a parlor maid at Tyneford House on the Dorset coast. Elise knows little English, and the charming, awkwardly worded "refugee advertisement" she'd placed in the London Times had persuaded Mr. Rivers of Tyneford to hire her.

Given her lack of training and her distinctive background, her presence upsets the natural order of things, just as one of her fellow servants predicts. When she becomes good friends with Kit, Mr. Rivers' Cambridge-educated son, no one seems to know how to treat her. Meanwhile, she writes letters to her married sister in California and waits, desperately, to hear from her parents that their overseas visa has been secured.

The House at Tyneford does an excellent job depicting a world in transition from the viewpoint of a woman who sits uncertainly between two social strata. The book's British title (The Novel in the Viola) reflects one of the items Elise carries with her to England: her father's last novel, hidden within a viola, which she hopes to have published one day.

The novel has a gentle, melancholy atmosphere, for war changes everything, and few of anyone's plans turn out as expected. Despite blurbs that compare it to Kate Morton's novels, I didn't really see it, except in the many details of English country life and its saga aspect. There is no real Gothic mystery, just a nostalgic tone of longing that the opening line conveys very well. Tyneford is based on Tyneham, an English "ghost village" that was requisitioned by Britain's Ministry of Defence in 1943; its residents were never allowed to return.

The House at Tyneford was published by Plume in December in trade paperback at $15.. If you'd like a chance to win a copy (US and Canadian residents), please fill out the form below. Deadline Sunday, April 15th.

Published on April 01, 2012 18:07

March 28, 2012

Bestselling historical novels of 2011

Publishers Weekly's annual announcement of bestsellers from the previous year is out. Once again (see my previous posts from 2010, 2009, 2008 and 2007) I'm focusing on just the historical novels that made it.

Here's the full PW list from 2011, which starts off by saying "For both fiction and nonfiction hardcover titles, name-brand recognition is the key to bestseller success." Which means that if a powerhouse bestselling author like Stephen King decided to write historical fiction, his novel would be on the list. (And it is.)

Books with hardcover domestic print sales over 100K were included in PW's list; publishers were asked to take returns into account, but some may not have, especially with end-of-year releases. A separate ebook bestseller list is available (for PW subscribers only).

Among the top 15, we find these:

#2 - Stephen King, 11/22/63 (919,500+ copies)

#11 - Jean Auel, The Land of Painted Caves (447,600+ copies)

What I wrote in 2010: "The rest of the top 15 is dominated by Stieg Larsson, a predictable crop of thrillers (Grisham, Patricia Cornwell, James Patterson and his coauthors), plus Nicholas Sparks, a couple of mysteries, and Franzen's Freedom." Subtract Freedom and add George R.R. Martin, and you'll have a nice description of 2011.

Other historical novels with over 100K copies sold are below, in descending order of sales. I'm using a broad definition of "historical novel," to include historical mysteries, literary fiction set in the past, fantasy set in a real historical era, etc.

Paula McLain, The Paris Wife (at position 27, or 301K copies)

Erin Morgenstern, The Night Circus

P.D. James, Death Comes to Pemberley (Not bad for a December release - I wonder how many people got this as a Christmas gift?)

Lisa See, Dreams of Joy

Clive Cussler and Justin Scott, The Race

Charles Frazier, Nightwoods

Diana Gabaldon, The Scottish Prisoner

Alice Hoffman, The Dovekeepers

Jeffrey Archer, Only Time Will Tell

Philippa Gregory, The Lady of the Rivers

Geraldine Brooks, Caleb's Crossing

My library's online PW login has stopped working for some reason, so I haven't seen the mass market or e-book lists and will have to wait until the issue reaches my desk. As before, it seems the best way to be a bestseller is to have been a bestseller, which gets circular quickly, but there are two debut novelists in there.

Amazingly, I've read some of these - the Gabaldon, Hoffman, Gregory, and Brooks.

Here's the full PW list from 2011, which starts off by saying "For both fiction and nonfiction hardcover titles, name-brand recognition is the key to bestseller success." Which means that if a powerhouse bestselling author like Stephen King decided to write historical fiction, his novel would be on the list. (And it is.)

Books with hardcover domestic print sales over 100K were included in PW's list; publishers were asked to take returns into account, but some may not have, especially with end-of-year releases. A separate ebook bestseller list is available (for PW subscribers only).

Among the top 15, we find these:

#2 - Stephen King, 11/22/63 (919,500+ copies)

#11 - Jean Auel, The Land of Painted Caves (447,600+ copies)

What I wrote in 2010: "The rest of the top 15 is dominated by Stieg Larsson, a predictable crop of thrillers (Grisham, Patricia Cornwell, James Patterson and his coauthors), plus Nicholas Sparks, a couple of mysteries, and Franzen's Freedom." Subtract Freedom and add George R.R. Martin, and you'll have a nice description of 2011.

Other historical novels with over 100K copies sold are below, in descending order of sales. I'm using a broad definition of "historical novel," to include historical mysteries, literary fiction set in the past, fantasy set in a real historical era, etc.

Paula McLain, The Paris Wife (at position 27, or 301K copies)

Erin Morgenstern, The Night Circus

P.D. James, Death Comes to Pemberley (Not bad for a December release - I wonder how many people got this as a Christmas gift?)

Lisa See, Dreams of Joy

Clive Cussler and Justin Scott, The Race

Charles Frazier, Nightwoods

Diana Gabaldon, The Scottish Prisoner

Alice Hoffman, The Dovekeepers

Jeffrey Archer, Only Time Will Tell

Philippa Gregory, The Lady of the Rivers

Geraldine Brooks, Caleb's Crossing

My library's online PW login has stopped working for some reason, so I haven't seen the mass market or e-book lists and will have to wait until the issue reaches my desk. As before, it seems the best way to be a bestseller is to have been a bestseller, which gets circular quickly, but there are two debut novelists in there.

Amazingly, I've read some of these - the Gabaldon, Hoffman, Gregory, and Brooks.

Published on March 28, 2012 14:17

March 25, 2012

My 6th blogiversary celebration and giveaway

Today Reading the Past turns six years old. To celebrate, I'm giving away six historical novels which I hope you'll find intriguing.

International entrants are welcome, plus the books originate from four different countries. There will be six winners in all, and you'll have the opportunity to pick which books you'd like a chance at. I've featured most of these on the blog before.

(1) Belinda Alexandra's Tuscan Rose (HarperCollins Australia, 2010), epic fiction set in Tuscany in the years leading up to World War II, is about a courageous young woman who lives through numerous hardships as she struggles to discover her mysterious origins.

(2) Barbara Erskine's Time's Legacy (HarperCollins UK, 2011), a time-slip novel with mystical themes, moves back and forth between modern Glastonbury, England, and its pagan origins 2000 years earlier. [read my review]

(3) Barbara & Stephanie Keating, To My Daughter in France (Vintage UK, 2003). In this multi-period spy novel and family saga, the will left by Irish academic Richard Kirwan reveals that he had a secret French daughter, Solange de Valnay, the result of a wartime liaison. I read this last year; it's an intense novel that's full (sometimes overfull) of drama, but I enjoyed it.

(4) Roberta Rich, The Midwife of Venice (Gallery, 2012). Suspense and adventure featuring a spunky Jewish midwife in 16th-century Venice who saves a Christian mother and her newborn baby at the risk of her own life. [read my review]

(5) Richard B. Wright, Mr. Shakespeare's Bastard (HarperCollins Canada, 2010). The story of Aerlene Ward, an elderly Oxfordshire housekeeper in the 17th century, who makes a late-in-life confession about her father's true identity.

(6) Margaret Wurtele, The Golden Hour (Berkley, 2012). Giovanna Bellini falls in love with a Jewish freedom fighter during the German occupation of her Tuscan village. [read my review and the author's guest post]

All are brand new and unread, either duplicates I received in the mail or books I bought two copies of by mistake (this happens more than I'd like to admit).

Please fill out this form to enter the giveaway. Deadline Sunday, April 8th. Good luck, and thanks for continuing to visit this site!

International entrants are welcome, plus the books originate from four different countries. There will be six winners in all, and you'll have the opportunity to pick which books you'd like a chance at. I've featured most of these on the blog before.

(1) Belinda Alexandra's Tuscan Rose (HarperCollins Australia, 2010), epic fiction set in Tuscany in the years leading up to World War II, is about a courageous young woman who lives through numerous hardships as she struggles to discover her mysterious origins.

(2) Barbara Erskine's Time's Legacy (HarperCollins UK, 2011), a time-slip novel with mystical themes, moves back and forth between modern Glastonbury, England, and its pagan origins 2000 years earlier. [read my review]

(3) Barbara & Stephanie Keating, To My Daughter in France (Vintage UK, 2003). In this multi-period spy novel and family saga, the will left by Irish academic Richard Kirwan reveals that he had a secret French daughter, Solange de Valnay, the result of a wartime liaison. I read this last year; it's an intense novel that's full (sometimes overfull) of drama, but I enjoyed it.

(4) Roberta Rich, The Midwife of Venice (Gallery, 2012). Suspense and adventure featuring a spunky Jewish midwife in 16th-century Venice who saves a Christian mother and her newborn baby at the risk of her own life. [read my review]

(5) Richard B. Wright, Mr. Shakespeare's Bastard (HarperCollins Canada, 2010). The story of Aerlene Ward, an elderly Oxfordshire housekeeper in the 17th century, who makes a late-in-life confession about her father's true identity.

(6) Margaret Wurtele, The Golden Hour (Berkley, 2012). Giovanna Bellini falls in love with a Jewish freedom fighter during the German occupation of her Tuscan village. [read my review and the author's guest post]

All are brand new and unread, either duplicates I received in the mail or books I bought two copies of by mistake (this happens more than I'd like to admit).

Please fill out this form to enter the giveaway. Deadline Sunday, April 8th. Good luck, and thanks for continuing to visit this site!

Published on March 25, 2012 08:00

March 22, 2012

A look at Madame Tussaud, by Michelle Moran

"You need to read Michelle Moran's new book," urged a reviewer friend after finishing Madame Tussaud. "Her ancient Egypt novels were good, but here she takes her writing to a whole new level." I can't help but agree. An epic about a smart woman and her troubled times, it depicts the transformation of Marie Grosholtz into the renowned wax artist whose creative skills were put to the test during the French Revolution.

"You need to read Michelle Moran's new book," urged a reviewer friend after finishing Madame Tussaud. "Her ancient Egypt novels were good, but here she takes her writing to a whole new level." I can't help but agree. An epic about a smart woman and her troubled times, it depicts the transformation of Marie Grosholtz into the renowned wax artist whose creative skills were put to the test during the French Revolution. In its depiction of celebrity culture, the tale feels strikingly modern. Her family's exhibition at the Salon de Cire is where Parisians come to see the day's superstars – their wax doubles, that is. From an authentic re-creation of Thomas Jefferson's elegant study to Marie Antoinette at her boudoir, they give the public what they want to see. As the novel hints, their creations are not just mannequins but symbols for the real thing, a fact that carries both responsibility and danger. Marie gets what she wants, too: a museum visit from the king and queen. Despite their growing unpopularity, Marie is a businesswoman at heart and knows their presence will draw crowds.

Very soon, she finds herself giving sculpting lessons to the king's devout sister, Madame Élisabeth, at Versailles, while her three brothers serve in the Swiss Guard. At the same time, in the evenings at their home, the kindly man she calls her uncle, her mentor Philippe Curtius, hosts a salon attended by the revolution's future architects: Robespierre, Desmoulins, and the Duc d'Orléans.

While Marie and her family prosper, thousands are starving in the streets and blame the royals for their misfortune. What starts as a people's rebellion devolves into bloody anarchy, a process conveyed in rich, devastating detail. The king and queen, while sympathetically portrayed, are self-absorbed and make foolish choices, and during this painful time in French history, even the smallest connection to the aristocracy leads one to the guillotine. Marie, whose family has the Revolution's trust, has the grisly honor of creating death masks for its most famous victims. She is the ultimate survivor: by keeping one foot in each camp, she saves her business and her head.

This magnificently crafted work makes you forget you're reading fiction; the story is so real and immediate that you'll feel like you're watching each vivid scene as it happens. Highly recommended.

~

Madame Tussaud was published by Broadway in December at $15.00/$17.00 in Canada (trade pb, 456pp, including glossary, author's note, and reader's guide). Quercus is the UK publisher, at £7.99. I read the added material in full, so I think this qualifies for the Chunkster Challenge even though that doesn't seem fair. I barely noticed the page count as I was reading.

Published on March 22, 2012 19:43

March 20, 2012

A visual preview of the summer season, part 1

A new season and a new preview, with some great-sounding books on offer. Many of these are by authors whose past works I've been enthused about.

If you haven't read or heard of Annamaria Alfieri's superb City of Silver, it may be time to change that. Set in the Peruvian city of Potosí in 1650, it swirls together the counterfeit silver trade, a young woman's supposed suicide, and racial tensions between Spaniards and natives. Invisible Country, the author's second South American mystery, moves two centuries ahead to 1868, when Irish courtesan Eliza Lynch was busy beguiling Paraguay's president, Francisco López. One of López's allies gets offed in this offering. Minotaur, July.

Amirrezvani's The Blood of Flowers was a major literary hit in 2007 for its portrayal of a female rug designer's quest for personal freedom and artistic expression in 17th-century Persia. Equal of the Sun is set in the royal court of Iran in 1576, and is based on a surprising friendship between the Shah's daughter and a eunuch after her father's unexpected death. Scribner, June.

Anton continues on her path of reanimating the lives of lesser-known women from early Jewish history. Subtitled "a novel of love, the Talmud, and sorcery," this first volume in a series tells the story of Hisdadukh, the youngest child of a wise and famous rabbi in 3rd-century Babylonia, a world of political and religious turmoil. Expect lots of interest from reading groups. Plume, August.

A few authors posted this pic on Facebook yesterday, and I just had to stop and gaze at it - it's full of jaw-dropping awesomeness. Bohjalian is making a return to historical fiction (his Skeletons at the Feast, from 2008, followed a group's lengthy, traumatic flight from Nazi Germany). Following the Armenian genocide of 1915, a young Mount Holyoke grad travels to Syria to care for ill refugees. An alternating tale in the present day reveals her granddaughter's story and uncovers a long-lost family secret. Doubleday, July.

The Woman at the Light is a debut novel set on an island off Key West in 1839. After her husband's disappearance at sea, Emily Lowry takes his place tending the lighthouse while caring for her three children. Then a runaway slave comes into her life. This was one of my LibraryThing Early Reviewers picks, and I chose it not just because of the setting but also because of the many four- and five-star Amazon reviews - which were based on the original self-published edition. St. Martin's Griffin, July.

When the author told me her next book would be a time-slip novel, I knew I had to add it to my wishlist. Since then, Courtenay won the 2012 Romantic Novelists' Association's historical novel prize for Highland Storms, set in 18th-century Scotland. The Silent Touch of Shadows contains many of the elements that appeal to me in fiction: a genealogical mystery, a multi-time structure, and a modern woman's visions of a couple from England's medieval past. Choc Lit (UK), July.

The woman on the cover should be easy to recognize even without half her head. Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, is the shadow queen in Dean's biographical novel about the infamous American divorcee who seduced Edward VIII away from his throne. It begins with her poverty-stricken girlhood in Baltimore, and based on the blurbs, portrays her as a survivor. The UK title is Wallis: The Shadow Queen. Broadway, August; HarperCollins UK, May.

Downer is an author I haven't read before; she specializes in Japanese historical settings in both her fiction and nonfiction. Across a Bridge of Dreams is billed as a romantic wartime epic set in the 1870s, just following the country's civil war, and is based on the historical story of the last samurai. Bantam UK, June.

With their glittering imagery of Gilded Age decadence and social differences, many of today's historical novels are described as Whartonesque... so it's logical that we now see a work of biographical fiction about Edith Wharton herself. Jennie Fields' novel aims to provide insight into the personality of one of New York's most famous novelists in its depiction of her affair with a younger journalist, and the effects it had on her friendship with her literary secretary, Anna Bahlmann. Pamela Dorman/Viking, August.

Look to Marina Fiorato for women's fiction with an Italian historical flair. I enjoyed The Daughter of Siena when I reviewed it last May, and the cover art gods are smiling on her books once more. The Venetian Contract begins as the plague arrives in Venice in 1576, a revenge gift from the Ottoman Turks following their defeat at the Battle of Lepanto. The stories of a brilliant architect, a plague doctor, and a female harem doctor intertwine. John Murray (UK), June; pb in August.

There have been few historical novels written about Isabella of Castile, though her daughters Juana (the so-called mad queen) and Katherine (Henry VIII's first wife) have gotten more attention. Gortner's biographical novel begins with Isabella's youth and follows her path as a wife, political leader, defender of the faith, and supporter of Columbus's exploratory vision. Look for an author interview here later this summer. Ballantine, June.

We've talked about the popularity of WWII novels featuring women; Gregson's latest carries this trend forward to a relatively unexplored setting. When Welsh singer Saba Tarcan travels to Cairo as part of a tour to entertain the troops, she's recruited for the British Secret Service - complicating her relationship with her fighter pilot beau. Touchstone, June.

If you haven't read or heard of Annamaria Alfieri's superb City of Silver, it may be time to change that. Set in the Peruvian city of Potosí in 1650, it swirls together the counterfeit silver trade, a young woman's supposed suicide, and racial tensions between Spaniards and natives. Invisible Country, the author's second South American mystery, moves two centuries ahead to 1868, when Irish courtesan Eliza Lynch was busy beguiling Paraguay's president, Francisco López. One of López's allies gets offed in this offering. Minotaur, July.

Amirrezvani's The Blood of Flowers was a major literary hit in 2007 for its portrayal of a female rug designer's quest for personal freedom and artistic expression in 17th-century Persia. Equal of the Sun is set in the royal court of Iran in 1576, and is based on a surprising friendship between the Shah's daughter and a eunuch after her father's unexpected death. Scribner, June.

Anton continues on her path of reanimating the lives of lesser-known women from early Jewish history. Subtitled "a novel of love, the Talmud, and sorcery," this first volume in a series tells the story of Hisdadukh, the youngest child of a wise and famous rabbi in 3rd-century Babylonia, a world of political and religious turmoil. Expect lots of interest from reading groups. Plume, August.

A few authors posted this pic on Facebook yesterday, and I just had to stop and gaze at it - it's full of jaw-dropping awesomeness. Bohjalian is making a return to historical fiction (his Skeletons at the Feast, from 2008, followed a group's lengthy, traumatic flight from Nazi Germany). Following the Armenian genocide of 1915, a young Mount Holyoke grad travels to Syria to care for ill refugees. An alternating tale in the present day reveals her granddaughter's story and uncovers a long-lost family secret. Doubleday, July.

The Woman at the Light is a debut novel set on an island off Key West in 1839. After her husband's disappearance at sea, Emily Lowry takes his place tending the lighthouse while caring for her three children. Then a runaway slave comes into her life. This was one of my LibraryThing Early Reviewers picks, and I chose it not just because of the setting but also because of the many four- and five-star Amazon reviews - which were based on the original self-published edition. St. Martin's Griffin, July.

When the author told me her next book would be a time-slip novel, I knew I had to add it to my wishlist. Since then, Courtenay won the 2012 Romantic Novelists' Association's historical novel prize for Highland Storms, set in 18th-century Scotland. The Silent Touch of Shadows contains many of the elements that appeal to me in fiction: a genealogical mystery, a multi-time structure, and a modern woman's visions of a couple from England's medieval past. Choc Lit (UK), July.

The woman on the cover should be easy to recognize even without half her head. Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, is the shadow queen in Dean's biographical novel about the infamous American divorcee who seduced Edward VIII away from his throne. It begins with her poverty-stricken girlhood in Baltimore, and based on the blurbs, portrays her as a survivor. The UK title is Wallis: The Shadow Queen. Broadway, August; HarperCollins UK, May.

Downer is an author I haven't read before; she specializes in Japanese historical settings in both her fiction and nonfiction. Across a Bridge of Dreams is billed as a romantic wartime epic set in the 1870s, just following the country's civil war, and is based on the historical story of the last samurai. Bantam UK, June.

With their glittering imagery of Gilded Age decadence and social differences, many of today's historical novels are described as Whartonesque... so it's logical that we now see a work of biographical fiction about Edith Wharton herself. Jennie Fields' novel aims to provide insight into the personality of one of New York's most famous novelists in its depiction of her affair with a younger journalist, and the effects it had on her friendship with her literary secretary, Anna Bahlmann. Pamela Dorman/Viking, August.

Look to Marina Fiorato for women's fiction with an Italian historical flair. I enjoyed The Daughter of Siena when I reviewed it last May, and the cover art gods are smiling on her books once more. The Venetian Contract begins as the plague arrives in Venice in 1576, a revenge gift from the Ottoman Turks following their defeat at the Battle of Lepanto. The stories of a brilliant architect, a plague doctor, and a female harem doctor intertwine. John Murray (UK), June; pb in August.

There have been few historical novels written about Isabella of Castile, though her daughters Juana (the so-called mad queen) and Katherine (Henry VIII's first wife) have gotten more attention. Gortner's biographical novel begins with Isabella's youth and follows her path as a wife, political leader, defender of the faith, and supporter of Columbus's exploratory vision. Look for an author interview here later this summer. Ballantine, June.

We've talked about the popularity of WWII novels featuring women; Gregson's latest carries this trend forward to a relatively unexplored setting. When Welsh singer Saba Tarcan travels to Cairo as part of a tour to entertain the troops, she's recruited for the British Secret Service - complicating her relationship with her fighter pilot beau. Touchstone, June.

Published on March 20, 2012 06:30

March 17, 2012

"A darker, redder name"

The name of Morgan Le Fay... it comes with some baggage.

The name of Morgan Le Fay... it comes with some baggage.As Arthurian buffs will know, Morgan is the daughter of Ygraine by her first marriage to Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall. Depending on which version you follow, she is either sent away to a nunnery or married off to a northern lord after Uther Pendragon kills her father. Or both of these, consecutively. Later, she becomes a sorceress who plots against Queen Guinevere and whose dark powers stir up trouble at her half-brother's court at Camelot.

Alex Epstein's The Circle Cast, a novel of her lost teenage years, forces us to re-imagine her character and role in the mythos by calling her something else.

His heroine, Anna of Din Tagell, is a girl of eleven when her life is shattered. Although it uses the legend as a springboard, this story is firmly situated in early medieval Britain, with Saxons preparing to attack, Uter Pendragon rallying the British as war leader, and Gorlois acting in the role of Roman provincial governor despite the Romans' departure from the island a century earlier.

Uter and Gorlois are allies at first. But when Gorlois gets wind of Uter's advances toward Ygraine, he breaks his oath to Uter and leaves... which causes Uter to come after him. Though still a child, Anna can sense enough magic to detect the glamor that the Enchanter casts on Uter and his men, the one that leads to Uter's seduction of Ygraine, the murder of Gorlois, and, nine months later, the birth of Arthur. (The Enchanter isn't called by name; names, as we learn, are important.) Anna is also puzzled at Ygraine's choice not to complete the magic circle that would have invoked the war goddess Morigenos in the defense of Din Tagell.

To keep her safe from Uter, Ygraine sends Anna away to Ireland, where her cousin Queen Ciarnat rules, and gives her a new name for her protection: Morgan, sea-born, "a darker, redder name than the name the wind had taken." Over the next number of years (either four or ten... the story contradicts itself in places), Anna/Morgan is forced to reinvent herself in other ways. Her plan for revenge against Uter takes root in this foreign land and sustains her during her travails. She becomes the slave of a pagan wise-woman, a scribe and teacher in a Christian settlement, and, finally, the wife of an Irish chieftain, Conall.

Wherever Morgan ends up, her scenes are rendered with a lyrical simplicity. The prose can read like that of a young adult novel, although some of the themes are geared more towards adults.

The story loses some focus the longer Morgan stays in Ireland, and Morgan, it seems, feels this too. She doesn't want to lose her ties to the land and its power, and she needs to see her mission through. Despite her strong affections for Conall, her role as his wife is getting in her way. What follows next is a vigorous yet heartbreaking tale about the value and price of vengeance.

The Circle Cast should add to the intrigue surrounding this complex Arthurian figure. Morgan's decisions may or may not be the reader's, but she stays true to herself regardless of the sacrifice.

The timing of this post is accidental, but as long as we're here: for those who don't especially care about the Arthurian connection, The Circle Cast also offers a sweeping picture of 5th-century Ireland, a place of woods and green meadows, warring clans, ancient pagan rites, and a young, new Christianity that inspires fierce devotion in its followers. There's plenty of ale and good storytelling to go 'round, too. Sláinte.

The Circle Cast was published by Tradewind Books in 2011 at $12.95 (trade paperback, 300pp), same price in the US and Canada.

Published on March 17, 2012 11:00

March 15, 2012

Guest essay from Chelsea Quinn Yarbro: Coming Up to the Terror

Almost exactly a year ago, I interviewed Chelsea Quinn Yarbro about the 24th entry in her St.-Germain cycle, An Embarrassment of Riches, set in 13th-century Bohemia. I'm happy to welcome her back to the blog today to discuss the historical backdrop to her most recent novel.

Almost exactly a year ago, I interviewed Chelsea Quinn Yarbro about the 24th entry in her St.-Germain cycle, An Embarrassment of Riches, set in 13th-century Bohemia. I'm happy to welcome her back to the blog today to discuss the historical backdrop to her most recent novel. With Commedia della Morte (Tor, March 2012), she presents a new angle on a well-known historical event: the French Revolution. I hope you'll enjoy her essay about late 18th-century French theatre, especially its life outside Paris, and how traveling performers were affected by the era's traumatic political events.

Also of note: Tor is currently holding a giveaway on Goodreads for 25 copies of Commedia della Morte, to mark its status as the 25th book in her series. US readers can enter the contest here.

~

Coming Up to the Terrorby Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Approaching the history in historical fiction can often become a kind of intellectual juggling act, finding ways to keep the story and history in dynamic balance, and never more so than when dealing with such major events as the French Revolution. It is not just a matter of sorting out the layers of incidents that brought it about in the first place; it requires a careful examination of all the factions, persons, and various groups that contributed to the Revolution, its high ideals and its turn toward the excesses of the Terror.

As a novelist, I find myself drawn to what I call the tweensie periods, those transitional phases of social changes that alter the character of the society that has gone before, which made 1792 irresistible for my twenty-third Saint-Germain novel (there are also two collections of short fiction), Commedia della Morte, when the forces of reform became increasingly extreme in their positions. The book began, as such works often begin, with what I call chasing the wild footnote: I was reading an extensive work on the French Revolution, looking for a time of modulation, when purpose and common goals diverge and politics become more intense. Within that crucial period, I try to find an event or series of events on which to hang my story; during that search, I came upon a footnote on the proliferation of street theatre throughout France during the Revolution. That was an angle that appealed to me, and I started hunting down as many sources on those street theatres as I could. What really hooked me was an article written some forty years ago on some of the touring companies in France at the time, some of which did not originate in France. Even better, I thought. Outsiders are always useful characters in dealing with social upheaval in fiction.

Like the rest of French society, in 1792 the nature of theatre was undergoing a redefinition: noble patrons had vanished (if they knew what was good for them) leaving their troupes to find other means of survival; the troupes changed their repertoire from classic French theatre to broad farce and broader satire. Public trials and executions were on the increase but did not provide the kind of entertainment many people craved, and so the actors who had performed for the aristocrats now took their talents to the common people, their new material and audiences pushing the troupes to extend the limits of their themes and styles well beyond what they had done for their high-born patrons. While Commedia del'Arte was largely on the way out by the mid-seventeen hundreds, the tradition was not entirely gone. The habits of touring players returned, performing plays and scenes adapted to the times and circumstances of the people who were their primary audiences. Some of these troupes proved to be highly successful, gaining enthusiastic followers. Among such feted troupes, occasional dramatic missteps or blunders gained far more attention than those made by lesser companies, and what was an artistic fumble for minor groups became a political disaster for major ones; those unlucky enough to have such a mishap could find themselves in tumbrels along with other unfortunates, meeting the same end that many of their patrons had met.

Being traveling players, the troupe, calling itself and its dramatic material Commedia della Morte, unlike many novels constructed around the French Revolution, the action takes place outside of Paris, in Avignon and Lyon for the most part, emphasizing the increasing executions and the growing political rancor among those forming the new bureaucracy. The shenanigans of local politicians jockeying for power plays a part in the successes of the troupe, often for reasons that have nothing to do with their scenarios or their popularity, but serve to provide leverage to local authorities in their maneuvering for personal advantage. Although most of these characters are fictional composites of authorities during that pivotal year, their various views, ambitions, and degree of ulterior motivation reflects the nature of the time.

By telling the story around this particular troupe, one that had had high-ranking patronage until the Revolution, and had fled France to the university city of Padova in Italy after the Revolution began, the return of the performers to France at the behest of Ragoczy Saint-Germain, the long-lived hero of the series, not only puts the story in motion, it provides a perspective on the Revolution seen through the troupe's eyes; having survived the initial purges of aristocratic privilege, the members of the company know they are in dangerous territory, not just for the nature of their performances, but due to the shifting political sands which they must accommodate. As their fame increases, the troupe's position becomes increasingly perilous, revealing how the turn to extremism was expressed in places outside of Paris.

From the first I have called these books historical horror novels, meaning that the history is horrifying, and that has never been more true than in Commedia della Morte.

About Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Chelsea Quinn Yarbro is the first woman to be named a Living Legend by the International Horror Guild and is one of only two women ever to be named as Grand Master of the World Horror Convention (2003). In 1995, Yarbro was the only novelist guest of the Romanian government for the First World Dracula Congress, sponsored by the Transylvanian Society of Dracula, the Romanian Bureau of Tourism and the Romanian Ministry of Culture.

Yarbro is best known as the creator of the heroic vampire, the Count Saint-Germain. With her creation of Saint-Germain in Hotel Transylvania (St. Martin's Press, 1978), she delved into history and vampiric literature and subverted the standard myth to invent the first vampire who was more honorable, humane, and heroic than most of the humans around him. The 25th volume of the Saint-Germain Cycle, Commedia della Morte , was published by Tor in March 2012. The first three books, Hotel Transylvania , The Palace and Blood Games , are all available as e-books from E-Reads.com.

A professional writer since 1968, Yarbro has worked in a wide variety of genres, from science fiction to westerns, from young adult adventure to historical horror.

For more information on Yarbro's many books and interests, check out her website at www.chelseaquinnyarbro.net.

Published on March 15, 2012 11:12

March 14, 2012

Reader survey for historical fiction

Mary Tod, a historical fiction writer who has guest blogged here in the past, has put together a survey on historical fiction reading preferences. Please take a moment to help her out by clicking on the survey link below, following her introduction. There's very little data on the readership for historical fiction out there, and the more responses she gets, the more useful the results! -- Sarah

~

Mary Tod writes historical fiction and, along with her agent, is working hard to secure a publisher. She blogs at www.awriterofhistory.com and at www.onewritersvoice.com. While researching for a blog post, Mary conceived the idea of conducting a survey to discover more about those who read historical fiction and those who do not - demographics, story preferences, favourite time periods, reasons for reading or not reading this genre, sources of recommendations and so on.

Please take a few minutes to complete the survey. To add to the robustness of data collected, please pass the survey URL along to friends of all reading interests.

Here's the link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/LNM7DKQ

Many thanks! ~Mary Tod

~

Mary Tod writes historical fiction and, along with her agent, is working hard to secure a publisher. She blogs at www.awriterofhistory.com and at www.onewritersvoice.com. While researching for a blog post, Mary conceived the idea of conducting a survey to discover more about those who read historical fiction and those who do not - demographics, story preferences, favourite time periods, reasons for reading or not reading this genre, sources of recommendations and so on.

Please take a few minutes to complete the survey. To add to the robustness of data collected, please pass the survey URL along to friends of all reading interests.

Here's the link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/LNM7DKQ

Many thanks! ~Mary Tod

Published on March 14, 2012 11:32

March 11, 2012

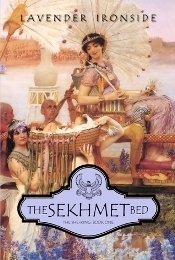

A visit to ancient Egypt with Lavender Ironside's The Sekhmet Bed

Off the top of your head, how many historical novels set in 18th-Dynasty Egypt can you name?

Off the top of your head, how many historical novels set in 18th-Dynasty Egypt can you name?There isn't much fiction taking place in this illustrious period of Egyptian history, despite its well-known historical figures (Nefertiti, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun) and major religious controversies, not to mention the many archaeological discoveries from the era. The industry seems to believe that aside from Cleopatra's time, ancient Egypt is a hard sell: the customs are too strange, the polytheistic religion too unrelatable, the names too unromantic.

I don't know about everyone else, but when I pick up a new historical novel, I don't want to read about people just like me.

For readers who crave fiction in this most promising of settings, Lavender Ironside's The Sekhmet Bed will be a treat. Opening in 1506 BCE, upon the death of Amunhotep I, it depicts a colorful, exotic land filled with feminine power and competition and the interference of demanding gods. Ahmose, the future mother of Queen Hatshepsut, Egypt's most successful female pharaoh, is the heroine – which may be a first. Little is known about Queen Ahmose's life or family relationships, which gives Ironside ample room for her interpretation.

A highlight is the fluid, accessible writing style. The descriptions are striking and culture-appropriate – the mosaic floors, the shining Nile waters, a man's jackal-like laugh – yet don't get in the way of the swift-moving plot. Ahmose, a young woman of fourteen, grabbed my attention from the start. She is just beginning to discover herself as a person when she's thrust into an unimaginably difficult position. Ahmose, rather than her beautiful 16-year-old sister Mutnofret, is chosen by her mother and grandmother, Egypt's high priestess, to become Great Royal Wife to Thutmose, the soldier hand-picked to be the new pharaoh.

When Thutmose takes Mutnofret as his second wife, their sisterly rivalry is taken to extremes, a premise that has gotten to be familiar. There are obvious comparisons to The Other Boleyn Girl and, some six generations after this novel takes place, Nefertiti and Mutnodjmet in Michelle Moran's first book. The difference here is that while Ahmose and Mutnofret are both strong-willed women who want the same things, they wield different types of power.

Intelligent, sensitive Ahmose is a dream-reader, and the gods speak through her; she has the strength the land needs. Nofret is hot-tempered, sexy, and fertile, a dangerous combination for a sister-queen. She knows how to attract a man, and she plays into her younger sister's insecurities and fears, including the dangers of childbirth. Each treats the other cruelly, and their mistakes have serious consequences. Their ongoing rivalry to outshine the other sometimes leaves their husband in the dust. Nofret may be the designated evil sister, but she never expected to play second fiddle; she had my sympathy at times, too.

Ahmose eventually gives birth to a daughter, Hatshepsut, whom she knows will be an only child. From her visions, she also knows the baby's ka, or soul, is male, and that Hatshepsut was born to be pharaoh in turn. Thutmose loves his daughter but refuses to accept this. It's here the novel attains its emotional height, with triumph, shocking tragedy, and reconciliation all interwoven in heartrending ways.

The novel carried me smoothly through the characters' drama-filled lives, but I had one niggling observation. Ahmose and Nofret grew up in the House of Women, the pharaoh's harem; they barely see or know their parents or grandmother until after the story begins. There's mention of a childhood nurse, and some older friends and cousins, but the sisters rely primarily on one another. Perhaps their early closeness made it easier to set up their rivalry later on, but still, I wondered why they had no other mother figure to depend on. It felt like something was missing in their history.

Pauline Gedge is the most prolific novelist writing about the same timeframe, and fans of hers should welcome this novel, too. Gedge's ancient Egypt feels alien from the outset, but thanks to her likable heroine and informal dialogue, the world Ironside creates doesn't feel as distant… not at first. She writes in her historical note that she did her best to balance the comfort of the reader against historical accuracy, and I feel she succeeded in her aim. The names, including place names, are authentic, and subtly inserted scenes, such as when Ahmose has her scalp shaved as per custom, emphasize the fact that this isn't a place we know.

~

The Sekhmet Bed, first in a projected trilogy called The She-King, is published as an e-book in various formats at $5.99; see Smashwords, or Amazon for the Kindle version. (I read it as a trade paperback proof, and, per the author, a paperback edition is in the works.) This is a self-published novel, though don't let that put you off. Despite enthusiastic praise from mainstream publishers, the author's agent was unsuccessful in selling it to one of them; the unfamiliar setting made it too much of a risk. Fortunately, there are new options available to authors these days. For more information, visit Ironside's blog at http://lavenderironside.blogspot.com.

Published on March 11, 2012 18:00