Christopher L. Webber's Blog

June 15, 2025

The Trinity

A sermon preached at All Saints Chuurch, San Francisco on Trinity Sunday, June 15, 2025

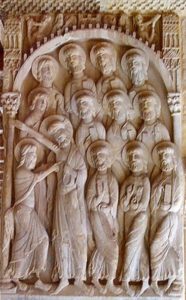

They say that drama in the western world got its start in church, that back in the middle ages the clergy (as usual) were trying to get people’s attention and so on Easter Day they had three women come down the aisle and pretend to be looking for a tomb. That’s how it all began. Then merchants’ groups and trade associations took it over and began producing what they called “mystery plays” – little dramas based on the Bible. And these were acted out around town and in church on the various holy days. There were mystery plays about the shepherds and about Herod

and about Noah’s ark.

And one thing led to another and so then there was Shakespeare and then there was Woody Allen. But it all began with the mystery plays, and they called them mystery plays not because they were whodunits or puzzles to be solved. They called them mystery plays because they dealt with the mystery of life – the parts of life you can’t explain in words or logic – things like an empty tomb.

Sometimes it’s easier to understand things if you see a play about it than if you go to a lecture or read a book. There are things you can’t explain as well with the logic of words on a page as you can with a picture or drama that says more than mere words can say about the wholeness of a reality beyond human words and logic.

Today is Trinity Sunday and if there is anything mysterious about Christianity, this is it.

What do we mean by Trinity?

We mean that God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

OK. What do we mean by that?

Well, we mean that God is Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier.

OK. What difference does that make?

Well, it means that God is at work above us and beside us and within us.

OK, I can get some meaning from that, but what if you drew me a picture? Wouldn’t that help? Well, there are diagrams that show the Trinity as a Triangle Iike the cover of the Bulletin today. Does that help? Well, maybe, a little bit,

but God is not a triangle or a set of circles or a diagram on the Bulletin cover.

The problem is that language, human language, is a tool of limited value. It can do marvelous things. It can produce the Bible and the Gettysburg Address and the plays of Shakespeare. It makes it possible for me to communicate with my family and the clerk at the checkout counter. It makes civilization possible. It makes it possible for a Senator and a Cabinet Secretary to talk to each other – if both will listen.

But a tool is only a tool and can only do certain things. And for all the sophistication of human language it seems not to be able to bridge the barriers between Israel and Hamas or Republicans and Democrats or Donald Trump and Elon Musk or Donald Trump and Governor Newsom or Donald Trump yesterday and Donald Trump today.

It was Thursday this week that we learned that while the President wants all illegal aliens out – all illegal aliens doesn’t include some illegal aliens. It doesn’t include the folks that harvest the crops in the Central Valley because someone pointed out to the President that we need those workers -legal or not – if we want vegetables on our dinner plates.

Even where both sides use the same language, it seems impossible sometimes really to hear, really to understand what the other is saying. It doesn’t bridge the gap between Sunni and Shiite, between North Korea and South Korea, between Israel and Hamas, or Israel and Iran, or bring about understanding between husbands and wives and between parents and children.

Language is just a tool. It gives us a way to talk about many things, but it has a hard time communicating the deep things, the things that matter. And it deceives us. It has a way of making us think we know something when we really don’t. Einstein can tell us “space is curved” and that sounds pretty definitive, like 2+2=4; “space IS curved.” Yes, but what does it mean? What is space? And the more scientists learn about space and time, the more we know how little we know. Light is composed of particles, but also of waves and we don’t quite know why it sometimes helps to think of it one way and sometimes the other. There are mysteries about science as well as religion, things we can’t finds words for.

There are times when we can understand more by watching a play than by listening to a sermon. A play puts things in three dimensions, brings it to life, lets us see it in the round, the way life really is. Because it is life we are trying to communicate, and words can help, they can help a lot, but the minute you start to think that you know something just because you can put it into words, just at that moment you may have missed the boat. And worse, because you think you got it and you didn’t.

The Trinity is a diagram, it’s a formula, it’s an attempt not so much to communicate a mystery beyond language as to point toward it, not so much to explain as to remind us that all explanations fall short, that finally God remains a mystery. It’s a way of recognizing who God is: the ultimate mystery, a being beyond all language, one to whom the best response is not words but actions: to genuflect, to repent, to open our hands, to rejoice, to offer one’s self to serve.

To celebrate Trinity Sunday is to recognize who we are and who God is. I think it’s interesting that Trinity Sunday has deep roots in the Anglican tradition. And maybe that’s why Anglicans, Episcopalians, are less likely than people in other churches to look for simple answers to hard questions, to expect that there are answers to all questions, to make religion a matter of rules and laws.

Most churches don’t celebrate Trinity Sunday. Protestant churches generally don’t worry about festivals except Christmas and Easter. Roman Catholics don’t have Trinity Sunday, and I think that’s unfortunate because if you celebrate Trinity Sunday every year you are brought face to face every year with the unknowable, with the God beyond knowing, beyond any reduction to black and white simplicities.

You probably don’t remember the Prayer Book before 1979. Willard and I do, but you probably don’t remember the so-called 1928 Prayer Book in which half the Sundays in the year were numbered not after Pentecost the way they are now but after Trinity Sunday. I think only Anglicans ever did that and we tend to down play it these days – after all how many preachers want to preach about the Trinity? But this day has had an enormous influence on the Anglican way of understanding God – or actually of not understanding – of remembering that our minds can only take us a little way, a very little way into the ultimate mystery of being. And that’s why we worship. Worship as we understand it is not about listening to sermons, it’s about offering our selves, our whole selves, mind and body.

Theology for us grows out of worship; it’s humble; it knows theological knowledge isn’t everything. There’s more, we know there’s more, but words alone can’t take us there. And maybe that’s why the English tradition grew up of mystery plays. Maybe they understood instinctively that some things could be acted out that couldn’t be said. Maybe there are things we can learn from a puppet show that could never be said in a sermon. Maybe there are things we can only say by coming to the altar with open hands.

One of the great contemporary American playwrights, Neil Simon, once said, “It’s like someone gave me a microscope and I looked through it at a slide and saw something of how life goes on. And I know with each play that if I can only find a more powerful microscope, I can see deeper and find out more. I believe that if I keep on working, I am going to unearth some kind of secret that will make it unnecessary for me to write again. But all I find is clues. And the more of them I find, the more fascinating and frightening life becomes. If I stop writing plays, I’ve got nothing left to do. It’s the only way I have of finding out what life is all about.”

There are mystery plays and there are musicals. It’s in a musical play – my Fair Lady – not by Neil Simon but based on a play by George Bernard Shaw – that I hear the ultimate wisdom. Maybe you remember the song with the words:

Don’t talk of stars Burning above; If you’re in love, hold me.

Tell me no dreams Filled with desire. If you’re on fire, Show me!

Here we are together in the middle of the night!

Don’t talk of spring! Just hold me tight!

“Don’t talk of love, hold me.” God might say that to us – especially on Trinity Sunday as we come forward to Communion: Here we are together in the middle of the church – don’t talk of love, hold me. Hold me.

So you want to understand the Trinity?

The Trinity is this:

it’s the sun setting over the blue line of the ocean to the west

and the rainbow arched over the city towers to the east;

it’s the cherry blossoms in full bloom on a spring day

and it’s the fog drifting in past the Golden Gate bridge;

it’s Francis of Assisi preaching to the birds,

and it’s Thomas Aquinas setting down logical propositions;

it’s a mourning family gathered around an open grave,

and it’s a newborn child placed in its mother’s arms;

it’s a scientist peering into a microscope to learn more about the retroviruses,

and it’s another scientist looking through a telescope at a distant galaxy;

it’s a hummingbird visiting the trumpet vine,

and soldiers nailing a young man’s hands to a wooden cross;

it’s women standing in puzzlement before an empty tomb.

It’s politicians willing to be patient, to seek understanding:

seeking peace in all things, seeking unity, not division.

It’s love. It’s love.

It’s God’s inexplicable love for the human race.

It’s God’s love shaping worlds,

God’s love speaking to us in Jesus Christ,

God’s love within us drawing us together –

drawing us to love, by love, through love.

The Trinity is just that simple and just that complex. But it’s that God, that triune God, who centers and renews our broken lives whom we come here to worship.

January 1, 2022

Jesus at the age of Twelve

A sermon preached at All Saints Church, San Francisco, on January 2, 2022, by Christopher L. Webber.

“After three days they found him in the temple, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions.” Luke 2:46

Do you remember being twelve years old? I do. I remember quite a lot about it. It was a traumatic year. I nearly died. I came down with pneumonia at Thanksgiving. The doctor came – they did that in those days – and said, “He’s a very sick boy.” He said I should go to the hospital.

I remember lying in bed and thinking, “I don’t care whether I get better.” When you’re twelve years old, that’s really sick. So they took me to the hospital. My home town in upstate New York had a good little hospital a couple of miles away but they didn’t have an ambulance so they borrowed the hearse from the undertaker. I had my first ride in the back of a hearse at the age of 12.

So they put me in a hospital bed and gave me blood transfusions every day and sent me tons of get well cards. I remember how they stuck the cards up on the walls. (How did they do that before Scotch tape was invented?) I guess it was all they knew to do, but with the cards and the blood transfusions I got better after a month or so and they sent me home for Christmas. I don’t remember whether I got a round trip in the hearse, but I think I must have because I know I didn’t walk out of the hospital. I remember that I was back home when I felt well enough one day to get out of bed and I fell flat on the floor because I hadn’t used my legs in a month and nobody had thought to give me exercises to keep my muscles in shape.

In January I was back in school and I remember that on my first day back at school there was a geography test on things they’d worked on while I was gone, but I got 100 anyway. Well, I had a stamp collection so I knew about countries and geography. We were also in the middle of Word War II and we had National Geographic maps pinned to the wall behind the radio and we put pins in the maps

to mark the location of battles. Geography, government, politics – that interested me and I knew about it.

I had one more significant moment that year. It came when the teacher, Miss Edwards, decided to get us thinking about pronunciation, and each of us was asked to come to the front of the room and read a passage from a book and asked the class to vote who did it best. Not a big moment, but I really wanted to win, and I did, and I still remember winning that totally unimportant reading contest at age 12.

Now, I’m not bragging about these rather minor accomplishments. I wasn’t the smartest kid on the class – there were a couple of girls that got better marks than I did – but I’m pointing to the events that mattered to me and determined who I would be. I knew life was serious and that there’s a big world out there and I wanted to know about it and I wanted to use my voice somehow to make a difference in that world.

I cared about words and language and politics at the age of twelve, and it came together by the time I got to college in the idea of a career in government. I majored in public and international affairs in college and we studied local and national problems, and the more I saw of government close up the more I saw that I wasn’t likely to make much difference. I was likely to be just one more voice in a clamor of voices – but ministry, with the building of local communities, might fit better with using my voice and finding ways to make a difference at the local level.

So I went to seminary, not Washington. I still pay close attention to the political world. After I retired I even did some canvassing and poll watching and even gave same advice one day to the Junior Senator from Connecticut about using his voice – and made a difference. But I think I made the right choice, and I began to see indications of a way forward at the age of 12.

You have your own stories, I’m sure. God works in various ways to bring us to an understanding of who we are and how we can make a difference. Jesus at the age of twelve was going through that same process: the Bible tells us he was listening and asking questions, exploring, learning.

We know from the Bible that Joseph was a builder. I think the most common Bible translations say “carpenter,” but the Greek word is “tekton.” It’s related to our word archi-tect. It’s a bigger word than “carpenter.” “Builder” might be better. So Jesus would have been involved in building, and no wonder he was interested in the great Temple in Jerusalem and wondered how those massive stones got moved and placed. The foundation stones of that temple are still there. They weigh mostly 2 to 5 tons. The biggest is estimated to weigh 570 tons. It may be the biggest stone ever moved until modern days. And the stone of the temple was lined with cedar panels.

I think Jesus, or any builder, would have looked at the Temple in Jerusalem with special interest. I imagine Jesus wandering around, looking at the temple with more understanding and curiosity than the average tourist and looking for the maintenance people to ask about it, and then, with the religious leaders and teachers, asking why this and why that until he totally lost track of the time as a 12-year old can do. But Mary and Joseph came looking for him as parents do, and took him back to Nazareth. He would come back to Jerusalem, of course, but for the moment his life was in Nazareth and he could begin to think about what he might build, how he might use his talents, perhaps to build synagogues, perhaps to build a church.

There’s a legend that makes a lot of sense to me that a few years later Jesus traveled to England with his rich uncle, Joseph of Arimathea. We know there was extensive trade between England and the Eastern Mediterranean in those days because in Cornwall, in the west of England, there are tin mines, and sometimes traders, merchants, needed to go to see for themselves who they could work with,

and how best to get things done. Joseph of Arimathea, the legend goes, made that journey and took his promising young cousin along to see something of the larger world.

Maybe you know the hymn they still sing in England:

“And did those feet in ancient times

tread upon England’s mountains green

And was the holy Lamb of God

in England’s pleasant pastures seen?”

If you go to Cornwall today, to Glastonbury, they will show you the Glastonbury thorn, a hawthorn tree that descends from a tree said to have grown from the staff that Joseph carried and that he stuck in the ground and that rooted and that often blossoms twice a year, once in May, but then again at Christmas time.

Do you remember the parable Jesus told of a rich man who traveled to a far country? He may have lived that story himself with Joseph of Arimathea.

Be that as it may, I’m suggesting that today’s gospel is one small glimpse of a process that shaped who Jesus was just the way I was shaped by my experiences and the way you have been shaped by your experiences.

There are other stories about Jesus that look at his story differently and suggest that Jesus had special knowledge and powers from day one. There’s a story told in ancient documents of how, when Jesus was maybe six or eight years old, he was playing with some other children, and they had found some clay and made clay pigeons, and Jesus’ pigeons flew away, but the other children’s didn’t. But that story is not in the Bible.

There’s a simplistic notion of Jesus that eliminates the humanity and makes him unreal, un-human from the first, but that’s not what Christianity is all about. Christianity is about incarnation: God coming to earth as a real human being of flesh and blood. It’s hard to get our minds around this idea that we sum up in the word “incarnation:” God in human flesh. It’s not about God pretending to be human. It’s about God being human, being a real 12-year old, curious about the world and how it works.

There’s that wonderful Christmas hymn that gets sung in the service of lessons and carols: “Once in royal David’s city.” It tells us that “he came down from earth to heaven, who is God and Lord of all, and his shelter was a stable and his cradle was a stall; with the poor, the scorned, the lowly, lived on earth our Savior holy.” Yes, but when they last revised the hymnal, they changed the words of that hymn and destroyed it. Cecil Frances Alexander wrote:

“He was little, weak, and helpless,

tears and smiles like us he knew . . .”

But they rewrote that in the hymnal we now use and dropped that “weak and helpless” phrase and, indeed, where Mrs Alexander wrote “For that child so dear and gentle . . .” the new hymnal wants us to sing: “for that child who seemed so helpless . . .” “Seemed”? No, he was. He was truly, fully human and that means growing up in weakness. “Seemed” is a formal, declared heresy called “docetism,” so ruled at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Don’t ever sing the 5th verse of hymn 102. No, no, no, “the word became flesh,” one with us, one of us, here with us, and when he was an infant, he was weak and helpless as infants are, and when he was twelve he had to explore and to learn and maybe be slightly rebellious as twelve-year-olds can be. And he may well have traveled to England and seen the world and heard sailors talk and matured and grown in wisdom and understanding so that after thirty years he had gained insights and must have begun to see how hard it would be to do what he was called to do, what he was sent to do, to bring together one fully human life with the fulness of the love and power of God.

Why after all are we here today except because we believe, we know, that the Almighty God lived among us, and knows our life from the inside, and knows our need from the inside, and did it for us, and died for us, and wants still to be involved in human life, in your life, and my life, and all life.

It’s a slow, uncertain process that shapes our lives, seeming to go in one direction, and then turning in another but learning along the way. It’s a process that brings us sometimes through great sickness and suffering to understand what others are suffering. When I visit someone in the hospital, I can say, “I know; I’ve been there.” God also can say to us: “I know; I’ve been there.”

It’s pretty wonderful isn’t it? But this, after all, is what Christianity is all about, and why Christmas is so widely celebrated even by people who have barely a clue abut its meaning. It’s why we bow or genuflect at the critical words of the creed: “For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven and was incarnate,” – and became truly human – “and was crucified, (and) died, and was buried.”

God became truly human. He grew up as we do, and was curious about things as we are, and died as we do. He knows who we are; he knows our needs; he knows human life from the inside, and therefore I come back again and again to what means more to me than any other verse or verses in the Bible – Hebrews 4:15-16 – as the very best summary I know of what it’s all about:

“For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who in every respect has been tested as we are, yet without sin. Let us therefore approach the throne of grace with boldness, so that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need. ” (Hebrews 4:15-6)

Wherever we’re called to go, we can go there because he’s been here, and he understands. He knows what it’s like to be a twelve year old and curious about the world, knows what it’s like to get tired, knows what it’s like to suffer and die.

There’s a story about how Jesus later on walked on water. So what? So did Peter – till he lost his nerve. I value more the story in John’s gospel (4:6) of how Jesus was traveling through Samaria one day and got tired and had to sit down and rest. He was truly human, one with us, one of us, to whom we can turn as to a friend and not a stranger, not a mere visitor. He knows us; he’s been here. And we know him, and we can turn to him for help, and he gives us now voices to use and hands to employ to follow him and make a difference.

October 23, 2021

Being Priests

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at All Saints Church, San Francisco, on October 24, 2021, on the 65th anniversary of his ordination to the priesthood.

“The former priests were many in number, because they were prevented by death from continuing in office; but Jesus holds his priesthood permanently, because he continues forever. Consequently he is able for all time to save those who approach God through him, since he always lives to make intercession for them.”

Hebrews 7:23-28

There’s a message for me in the second reading this morning. It tells us that “The former priests were many in number, because they were prevented by death from continuing in office.”

A modern translation puts it this way: “there had to be many priests, so that when the older ones died off, the system could still be carried on by others who took their places.”

“When the older ones died off . . .” Happy anniversary!

Right: “Happy anniversary – but let’s be practical: there’s somebody waiting to take your place.”

I hope they don’t mind waiting a little longer.

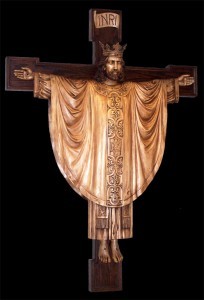

But the important point the author is making is that all this coming and going of priests takes on a whole new light when priesthood itself is reoriented, restructured, recreated by the death of Jesus Christ on the cross.

But let’s go back and start over. How did we get from there to here? What were priests for? Priests were for putting things right between God and human beings. And it wasn’t just the Jews who had priests. So did the Canaanites, so did the Romans, so did the Egyptians, so did almost everybody at a certain stage of human development because it was obvious as human beings evolved and became thoughtful that there was something askew, something out of alignment, something messed up in human affairs and therefore a need to do something to set things right.

It was pretty obvious: here on the one hand is a beautiful world and here on the other hand are human societies, human beings making a mess of things – lying, stealing, fighting, killing – husbands and wives at odds with each other, children at odds with parents and peers, politicians at odds with the facts.  Something’s wrong, something’s deeply wrong, fundamentally wrong, and we need forgiveness and renewal. We need help getting it right. But how?

Something’s wrong, something’s deeply wrong, fundamentally wrong, and we need forgiveness and renewal. We need help getting it right. But how?

Well, maybe if we could get help from above it would make things better, so let’s bring the gods an offering and ask their help in making life better. And when things go well – sometimes they do – sometimes things do go better than we could have imagined or merited – love and marriage can be great – sometimes life in a parish can be wonderful – and sometimes politicians work for the common good. Sometimes. Sometime it doesn’t rain on our parade or our picnic. Sometimes. And we should be grateful that there are achievements to celebrate: more comes our way than we could ever deserve. So let’s also celebrate that with sacrifices. Let’s bring the gods an offering, not just to say, “I’m sorry” but also to say “I’m thankful.” there are lots of reasons to offer sacrifice, to keep things cool between the gods and us because so much of life is beyond our control and we need the unseen powers on our side. So either way – because we need help or because we’re grateful – we need to bring offerings: sin offerings, thank offerings, offerings to make things right with the gods or the God and we need priests to help us make those offerings and we need to bring our best.

And so a system developed and you can read about it in your spare time in the Book of Leviticus:

“When you sacrifice to the Lord your God bring an ox or a bull and kill the animal and sprinkle the blood on the sides of the altar then skin it and quarter it and build a wood fire on the altar and put the sections of the animal and its head and its fat upon the wood; the internal organs are to be washed, then the priests will burn them upon the altar and they will be an acceptable burnt offering with which the Lord is pleased.”

Imagine doing that on Sunday morning. We’d need more hands on the altar guild for sure. But that’s just getting started. The Book of Leviticus goes on chapter after chapter with directions for sin offerings and guilt offerings and offerings of thankfulness

But also in the Old Testament you find the writings of the prophets, who took a different slant on things and spoke in God’s name to say, “I hate, I despise your sacrifices; turn from your evil ways, do justice, love mercy . . .” Which is great, but forgets that fundamental human problem: we can’t. We want to, but we can’t. We mess up. There’s always a terrible gap between the ideal and the reality. We need to do something to get things right. We always fall short, so what can we do to get the forgiveness we need, the help we need, to bring ourselves into alignment with God or God into alignment with us?

Well, that’s the history, but that’s not where we are. We are AD not BC. There’s really nothing we can do now because whatever is needed has been done for us by the death of Jesus Christ on the cross: a “ful l, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice” as it said in the Prayer Book 65 years ago and still says in Rite One. Nowadays we settle for calling it “a perfect sacrifice.” But whatever you call it, it’s what we never had until Jesus. Now there’s no need for sheep and oxen and all that because we have something better to offer to get ourselves right with God. Jesus is priest and sacrifice he makes the offering and he is the offering, and he joins us in that offering because are members of his body by baptism, and that body of which we are members is a priestly body so we also offer ourselves. It’s why we’re here this morning: not just to celebrate my priesthood, though that’s nice, but to enact your own. Those who are baptized are made members of the body of Christ, the body that was offered on Calvary, and we offer ourselves as a priestly people. We are a priestly people, but can’t have everyone stand at the altar on Sunday, so we ordain certain people to be priests for a priestly people. We come to take part in the one perfect sacrifice of Jesus and we all have a role to play. It’s why it makes sense for those who can and who want to to stand during the prayer of consecration: to stand with the priest and

l, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice” as it said in the Prayer Book 65 years ago and still says in Rite One. Nowadays we settle for calling it “a perfect sacrifice.” But whatever you call it, it’s what we never had until Jesus. Now there’s no need for sheep and oxen and all that because we have something better to offer to get ourselves right with God. Jesus is priest and sacrifice he makes the offering and he is the offering, and he joins us in that offering because are members of his body by baptism, and that body of which we are members is a priestly body so we also offer ourselves. It’s why we’re here this morning: not just to celebrate my priesthood, though that’s nice, but to enact your own. Those who are baptized are made members of the body of Christ, the body that was offered on Calvary, and we offer ourselves as a priestly people. We are a priestly people, but can’t have everyone stand at the altar on Sunday, so we ordain certain people to be priests for a priestly people. We come to take part in the one perfect sacrifice of Jesus and we all have a role to play. It’s why it makes sense for those who can and who want to to stand during the prayer of consecration: to stand with the priest and  express our own priesthood. The priest’s role is a unifying role, an expression of who we all are and the priest plays out that role day by day in everything he or she does, symbolizing Christ’s presence, uniting and offering the daily life of the church.

express our own priesthood. The priest’s role is a unifying role, an expression of who we all are and the priest plays out that role day by day in everything he or she does, symbolizing Christ’s presence, uniting and offering the daily life of the church.

So let me dramatize all that by telling you a story about one day in my priesthood – not a typical day, but one that dramatizes perhaps priesthood at a working level There came a Saturday morning 60 years ago when I was the priest at a parish in Brooklyn, the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn, a stable, blue colar neighborhood. I’d been there several years and one this particular Saturday morning I was for some reason sitting in the sun on the back steps of the Rectory. My wife was just inside in the kitchen reading the NY Times, and she called out, “Did you see about Peter L. in the paper?” I said “No what abut Peter L.?” And she said, “Well, they found his body in the trunk of a car on the dock” and I said, “I guess I’d better go see his family.” I’d met Peter one night when I was making a parish call on his wife. She and the three children were in church most Sundays but I hadn’t met Peter before. He came in that night and I got introduced, but he didn’t take his dark glasses off and he didn’t stay – and now he was dead. Before I could get up to get organized and go and my wife called out “Did you see about Richard Y? and I said, “No, I didn’t.” I guess I really hadn’t looked at the paper at all. “So what about Richard Y?” “Well, he stole a car and ran it into some children on the sidewalk, killing some and injuring others and fled the scene of the crime and resisted arrest.” So I said, “Well, I guess I need to call on the Y family also.” I’d been there of course – the children were often in church – but I think Richard was the oldest of 10 or 12 in a pretty chaotic family. I’m sure I’d met him, but I didn’t really know him. So I got myself organized and went to visit the L family first. Peter’s relatives were there, and they were making a great fuss about planning a funeral and insisting on emptying the bank account to buy flowers and hire limousines and make a show. Mrs L was resisting – she had small children to provide for and didn’t know where the money would come from. I took her side and told people there was no need for a big show, that’s not how we need to do things. And that carried weight, because I was the priest after all and I spoke with that authority. That’s the main thing I remember about that visit. But then I had to go on to see the Y family. I’d been there before also. A priest calls on people so he or she doesn’t come as a stranger when there’s a crisis. I’d been there and I had the sense of a family with too many children and not enough stability, but by the time I got there Mrs Y had reacted to the story about her son by dying of a heart attack. So I had to spend some time with them, and what with one thing and another it was evening, it was dark, before I tracked down Richard Y in a prison cell in Manhattan to tell him through thick glass with the help of a microphone that his mother was dead.

One day in the life of a parish priest. I will say I never had another day quite like it and that’s not a typical day in the life of a parish priest. Not every day in a priest’s life is like that. But every day in the New York Times is like that – every day is like that somewhere because every day we human beings are out there messing up our lives and other lives and it’s no wonder the ancient peoples brought sacrificial offerings and splashed blood on the altar looking for help with their lives. And not just the ancient people. There’s an old spiritual that says it all: “It’s me, it’s me, it’s me, O Lord, standin in the need of prayer; Not my father nor my mother but me O Lord. Standin in the need of prayer.”

But there’s a footnote to the story: many years later I was in my car with the radio on to get the news and there was a report about a District Attorney on Long Island who was dealing with a case in court and the name of the District Attorney was the name of one of the children in the L family. It wasn’t a usual name and I like to think that his mother hung in there and made a difference for those children, and that my successor in that parish and other priests perhaps in other parishes had also been there for them and made a difference.

Now that was not, as I said, a typical day in the life of a priest – thank goodness – but it’s a dramatic way of making my point: That the priest is someone who is there, who is here in this community, who represents this congregation and the Lord Jesus day by day, good times and bad. The priest is a  representative person, representing the members to God, representing God to the members, and leading the offering of ourselves to God that makes us who we are: God’s people, a priestly people, members of the body of Christ our great high priest in whom we live and move and have our being as we carry out our own priesthood representing Jesus wherever we are and offering our own lives for the changing, the transformation, the remaking, the renewing, the redeeming of this broken, suffering world.

representative person, representing the members to God, representing God to the members, and leading the offering of ourselves to God that makes us who we are: God’s people, a priestly people, members of the body of Christ our great high priest in whom we live and move and have our being as we carry out our own priesthood representing Jesus wherever we are and offering our own lives for the changing, the transformation, the remaking, the renewing, the redeeming of this broken, suffering world.

July 24, 2021

The Forest of Life

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at All Saints Church, San Francisco, on July 25, 2021.

I’ve lived several lives in the last ten days. I’ve had my life taken over by commitments I had made that controlled my life, sometimes it seemed every waking minute of it. They were commitments I had made – in one case several months earlier – that emerged two days apart and took over.

First, I had somehow gotten committed to reading, for a zoom-type of audience, a famous speech by the great 19th century black leader Frederick Douglass titled “What, to the American Slave, is Your Fourth of July?” Douglass made that speech to an audience of white Americans and his answer was:

“a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; . . . your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy— a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

Now, it’s one thing to read that paragraph to you on Sunday morning, but quite another to read it as one small part of an hour long speech to an unseen audience. But that’s what I had agreed to do, and it took over my life as I reread and rehearsed it.

Forty-eight hours later, I was equally committed to lead a delayed 4th of July sing-along of American  patriotic songs: “Mine eyes have seen the glory,” “Lift every voice and sing,” “America the beautiful.” and a dozen more. They’re wonderful songs, but I was committed to leading this sing-along on my recorder, and I hadn’t played my recorder in public in fifty years. So I was practicing. Believe me, I was practicing, because you have to go on instinct, the notes have to become second nature. Those two commitments took over my life for 48 hours and I survived.

patriotic songs: “Mine eyes have seen the glory,” “Lift every voice and sing,” “America the beautiful.” and a dozen more. They’re wonderful songs, but I was committed to leading this sing-along on my recorder, and I hadn’t played my recorder in public in fifty years. So I was practicing. Believe me, I was practicing, because you have to go on instinct, the notes have to become second nature. Those two commitments took over my life for 48 hours and I survived.

Haven’t you had that happen? Haven’t you had your life taken over once or twice, maybe often, in a similar way: a project at work with a deadline, a wedding reception to organize, a calling committee to find a new priest for All Saints Church. You can’t do these things and keep up with the latest Washington scandal or that book you always wanted to read. Our lives sometimes get taken over by our commitments. Usually we survive, and we learn things about ourselves – good and bad – and we are changed in good ways and bad.

Not every book or project asks us for that commitment. I’m reading a book just now about Jimmy Hoffa and the Teamster’s Union. I’m gaining new insights into another aspect of American life: murder, black mail, betrayal. It’s interesting, but I can put it down. I can put Hoffa down, but not Douglass. I couldn’t just pick up Douglass’ speech for a few minutes and put it down again. To live with Frederick Douglass’ speech full time for a few days makes a difference: you live inside another man of a different color, a different time, a radically different experience of America, and you see America with his eyes, and you are changed.

St. Paul was changed. You know the story of St Paul on the road to Damascus. He saw a great light and he heard a voice and he was changed. But just before he started that journey he had been an official witness to the death of Stephen, the first Christian martyr, stoned to death for his faith in Jesus. As Paul rode north toward Damascus how could he avoid reflecting on that witness? I think it took over his mind as he rode, mile after mile, and he saw again the stones fly and he heard again Stephen as he died praying forgiveness for his murderers. Paul relived that day and it took over his  mind and heart and life, and he was changed. But the light and the voice were only the outward, visible, audible climax of an event that had already taken over Paul’s life and changed him for ever.

mind and heart and life, and he was changed. But the light and the voice were only the outward, visible, audible climax of an event that had already taken over Paul’s life and changed him for ever.

Is your relationship with Jesus like that? That’s the question St. Paul puts to us in the second reading this morning. I pray,” he says, “that you may . . . know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, so that you may be filled with all the fullness of God.” That you may know the unknowable and be filled with the inexhaustible and be changed forever: that’s Paul’s prayer for us. It should be our prayer for ourselves: “To be filled with all the fulness of God.” “That you may be strengthened,” he continues, “strengthened in your inner being with power through his Spirit, and that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith, as you are being rooted and grounded in love.

“Strengthened in your inner being – as you are being rooted and grounded in love.” That you and I should be changed. I think that’s why we’re here.

Isn’t that why we’re here? We’re here to be changed. And Paul tells us how that change comes about: that we must be “rooted and grounded in love.”

I’ve read some books recently that help me understand what that means. One book was about trees and one was about mushrooms. Trees, it turns out, are more complicated than we might have thought. We might have thought that a tree only needed to stand there and soak up the sunshine and rain, let the roots reach down and pull in what’s needed and have a nice life. It’s not that easy. What we’ve been  learning lately is that the roots do go down, but the roots also go out. And as they spread, they intersect with the roots of other trees and with the myscelliae of mushrooms, the fibers that mushrooms send out to make more mushrooms but also to enrich the soil in which the tree has its roots. So the roots of the tree interact with the mushroom fibers and interact also with the roots of other trees, sharing nutrients and actually passing on messages. The roots the trees put down are a fibrous web of communication through which the trees cooperate for the welfare of the forest. Every single tree is rooted and grounded in a rich soil that is shared with other trees.

learning lately is that the roots do go down, but the roots also go out. And as they spread, they intersect with the roots of other trees and with the myscelliae of mushrooms, the fibers that mushrooms send out to make more mushrooms but also to enrich the soil in which the tree has its roots. So the roots of the tree interact with the mushroom fibers and interact also with the roots of other trees, sharing nutrients and actually passing on messages. The roots the trees put down are a fibrous web of communication through which the trees cooperate for the welfare of the forest. Every single tree is rooted and grounded in a rich soil that is shared with other trees.

Aren’t we like that? Don’t we put down roots here in this place that not only draw up the life saving food we need but draw from others and also enrich others so that we become a forest of Christian trees – Christian trees – mutually dependent and mutually supportive and growing together toward the sun, toward the Source, Guide, and Goal of all life, from whom all life comes and toward whom all life goes. Hold onto that image of inter-connectedness, it’s one of the hallmarks, I think, of catholic Christianity as distinct from Protestant Christianity. Its about corporate life more than individual conversion. It’s about communion. It’s about living in communion, It’s about community. It’s about church. It’s about the kind of total commitment that changes lives.

Think of ourselves that way this morning: a small forest here in this vast city, but a forest in which we grow by soaking up the gifts we are offered: the Word proclaimed, the sacrament received. Maybe that gift is given at the altar as it used to be; maybe in our pews as we need to do now, but always it’s given corporately, always together, never as solitary individuals never as the lone oak in an empty landscape, always as a family, a forest, a communion of saints, a living body of praise to the glory of God and the transformation of our lives.

Think of ourselves that way this morning: a small forest here in this vast city, but a forest in which we grow by soaking up the gifts we are offered: the Word proclaimed, the sacrament received. Maybe that gift is given at the altar as it used to be; maybe in our pews as we need to do now, but always it’s given corporately, always together, never as solitary individuals never as the lone oak in an empty landscape, always as a family, a forest, a communion of saints, a living body of praise to the glory of God and the transformation of our lives.

April 10, 2021

Touching Reality

What Can I Believe?

A sermon preached at All Saints Church on the Second Sunday of Easter, April 11, 2021, by Christopher L. Webber.

What can I believe? What can you believe?

Suppose a friend tells you, “There’s a sale at Staples today: they have iPads at 10 cents a piece. Now, you trust your friend, but you have to ask: “Are you sure? Did you see it yourself?” Is there some trick to it, some qualification like: the first five customers, or until noon yesterday, or if you buy five six packs of beer first? We just instinctively, and out of long experience, weigh what we hear by a number of factors: we balance the outlandish claim against past experience, against importance to us, against what we know about the real world, against probabilities of various sorts – and then we believe or not, depending.

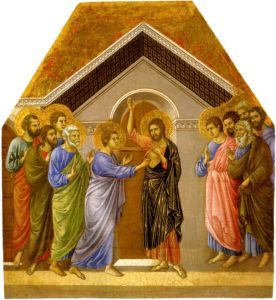

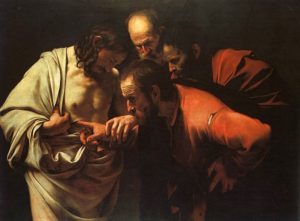

If someone tells you later today that Donald Trump has announced his candidacy for 2024, I expect you’ll believe it with no questions asked. Some things are not a surprise. So: what can I believe and how firmly can I believe it? I think these are fundamental questions we deal with daily. But Thomas in today’s gospel reading was asked to believe something on which life depends and on three grounds: first what he heard from others, secondly what he could see for himself, and thirdly what he could actually touch. Three senses: hearing, seeing, feeling.

The first sense, hearing, he was sure was not enough. I don’t think it ever is when something’s important. Hearsay evidence doesn’t carry much weight and it shouldn’t. If you ever played a game of telephone as a child – you know: you whisper something to someone who whispers it to the next who whispers it to the next and what started out as potatoes at one end winds up as baloney at the other. Who knows what will come out at the other end of the chain?

I remember a news report, back when Barack Obama was running for the first time and reports were being spread that he was a Muslim. A television reporter was shown asking some men in a midwestern diner who they would vote for and why and one of them said he couldn’t vote for Obama because Obama was a Muslim. And the reporter said, “Well, but he isn’t a Muslim.” And the man in the diner said, “But what’s what I’ve heard.”

So hearing isn’t very reliable and Thomas knew that and wasn’t about to rely on it, nor was he even ready to be satisfied by seeing. “Seeing’s believing” is the old saying but any magician knows that the hand is quicker than the eye and we can think we see something that’s not really there at all. In an age when virtual reality is a familiar idea, when we can project holographic images and show someone as present who’s actually in Bangladesh, when we can go to the movies and be shown special effects that are totally unreal and untrue, seeing is not believing.

So hearing isn’t very reliable and Thomas knew that and wasn’t about to rely on it, nor was he even ready to be satisfied by seeing. “Seeing’s believing” is the old saying but any magician knows that the hand is quicker than the eye and we can think we see something that’s not really there at all. In an age when virtual reality is a familiar idea, when we can project holographic images and show someone as present who’s actually in Bangladesh, when we can go to the movies and be shown special effects that are totally unreal and untrue, seeing is not believing.

The result is that touch and feel become more important than ever and especially because of what we are as human beings. I am a flesh and blood, material human being. I may see things, hear things, imagine things, but it’s touch that brings me into relationship with what I am: flesh and blood, material, capable of banging into things, being hurt by the collision; that’s reality as we experience it. That’s what we can believe. When I pound on the pulpit (which I can’t do on zoom and don’t often do anyway!) I know this is real, it’s here, I can feel it.

Now, this story about Thomas tells us several things but one that’s important is the place of the sacraments in our lives. Our worship is not just sight and sound as some worship is. We don’t go to church just to listen and maybe sing as some worshipers do but to taste and touch and feel. If I were an Evangelical, I’d get along a lot better with zoom than I can as an Episcopalian, a Christian in the Catholic tradition. I want sacraments. I want to be wholly involved: hearing, yes, but also tasting and touching and feeling. To make new members of the church we don’t just announce it, we pour water over them. We don’t just pronounce two people husband and wife, we join their hands at the altar and wrap a stole around their hands. As soon as possible, we will once again use bread and wine to know Christ’s presence here. Jesus says to us as he said to Thomas, “Reach out your hand and feel this bread, touch my body, and know that I am with you still.” Christianity is about God’s relationship with the material world.

At the center of our faith is the fact that God came into this material world that God created and lived in it in real flesh and blood. Our faith is an incarnational faith. God is real for us in a way that no other faith can claim: God took human flesh, became real for us in the ultimate way, and the celebration of Easter is about the resurrection of that flesh, that human body. I keep meeting people who think that Christians believe in the immortality of the soul and I guess some do, but that’s not what the Creed says. The Creed says it’s about the body, the resurrection of the body. It’s not about a soul that we can’t even see or hear let alone touch; it’s about a reality that we can understand, that’s tangible, that we can touch and taste and feel. Easter is not about spiritualism; it’s about materialism.

At the center of our faith is the fact that God came into this material world that God created and lived in it in real flesh and blood. Our faith is an incarnational faith. God is real for us in a way that no other faith can claim: God took human flesh, became real for us in the ultimate way, and the celebration of Easter is about the resurrection of that flesh, that human body. I keep meeting people who think that Christians believe in the immortality of the soul and I guess some do, but that’s not what the Creed says. The Creed says it’s about the body, the resurrection of the body. It’s not about a soul that we can’t even see or hear let alone touch; it’s about a reality that we can understand, that’s tangible, that we can touch and taste and feel. Easter is not about spiritualism; it’s about materialism.

Spirituality is very popular these days but fewer people are going to church. They’re two different things. Spirituality is what it is, but Christian faith is something much more. I like to quote the former Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple, who said, “Christianity is the most materialistic of the world’s religions.” And it is. It’s a religion that has to do with God here, God known to us in flesh and blood and therefore concerned with flesh and blood, concerned with problems of poverty and hunger. It’s not a religion of escapism.

So I could simply preach about the sacraments today and how central they are to Christian faith. But what I want to do is to look more deeply at the whole question of matter and spirit and ask what we mean by that classic division between spiritual and material anyway. And what I want to suggest is that this standard division between material and spiritual is really out of date, in a post-Einstein world. I don’t believe we know anymore where the border is between the physical and the spiritual. When scientists talk about quarks and mesons and subatomic particles and fields of force and dark matter that may be the commonest substance in the universe and yet is undetectable so far by human intelligence, where would you draw the line between what’s physical and what’s not?

The Prayer Book defines a sacrament as an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace as if there were two kinds of reality, the material one you can taste and touch and the spiritual one you can’t. In the middle ages, there was a clear line between material and spiritual and everything had to be one or the other. Christianity with it’s talk about incarnation and sacraments tried to cross that line but it still left us in a divided world in which the things that we knew about from every day experience were the material things while the things that mattered were the things we couldn’t know directly. But we live after Einstein and we know that the material world isn’t all that solid. The solid walls of your house, we know now, are made up of atoms that are made up of electrons and even smaller particles like meson composed of quarks and anti-quarks and more, some of which we know only as theory and have never really been seen and certainly not touched.

Worse than that, not only is there no way to taste or touch or see the ultimate elements but they can be turned into immaterial energy, because E=MC squared as I’m sure you know and MC squared=E. The wood of the pew you sit on in church can burn and become heat energy and the energy of the sun can be transformed into the green plants that push up out of the soil. Worse still than that, the material universe includes what science calls “forces.” We all know about gravity but then there’s the electromagnetic force and there are two types of nuclear force. And at the cutting edge of science you actually find them using terms like “weird” and “spooky” as technical terms as the scientists try to reduce the material world to something they can understand. But the physical world keeps escaping from their experiments and leading them out into a world that sometimes seems more spiritual than material.

What kind of world is it in which scientists use terms like “weird” and “spooky?” I saw a book review in the New York Times some while back that talked about “wildly imaginative” new ideas about the basic structure of matter. It said that the fundamental problem with these ideas is that there’s no way to test them. But science is about testing and if you can’t test it, how can it be science? The boundary between the material and the spiritual seems to have disappeared. Which takes us back to Thomas, because that was Thomas’ problem too and the problem of the Christian church when it tried to understand and explain the eucharist and the sacraments.

But isn’t that what we should have expected to learn as we explored God’s world? Shouldn’t we have expected to learn that it was all one and that the hard cold rock in our garden which God made is ultimately simply one more expression of the ultimate reality which is God? Isn’t love one form of reality and aren’t rocks another? And aren’t both of them evidence of the creativity of the same God? When we take the bread of the eucharist in our hands, that too can be analyzed as matter: It’s composed of flour and water; but those ingredients are composed of atoms of carbon and hydrogen and so on, and that’s potential energy. If you burn it, heat is created. If you eat it, the body absorbs the energy. The bread is  material, it’s physical, but that means it’s also potential energy and it’s transformed into energy when we eat it. But if you come here with faith, there’s another kind of energy at work as well, as Christians have always known even though they have often disagreed as to just what that energy is. But whatever language you want to use, it has to do with the way Christ comes to us in our worship and prayer renewing our lives by his life. You, a child of God, are joined with God and your life is renewed.

material, it’s physical, but that means it’s also potential energy and it’s transformed into energy when we eat it. But if you come here with faith, there’s another kind of energy at work as well, as Christians have always known even though they have often disagreed as to just what that energy is. But whatever language you want to use, it has to do with the way Christ comes to us in our worship and prayer renewing our lives by his life. You, a child of God, are joined with God and your life is renewed.

Now, Thomas didn’t know all that when he tried to understand what the other disciples were telling him. He thought he had it all figured out. His world was material and that was all. He thought that when matter died that was an end of it. Thomas didn’t know about Einstein. And Thomas didn’t really understand that the world is one, that God is one, that all life and matter and creation exist only because of God and there are no boundaries except the ones we make in our heads. Thomas, you might say, was the original scientist, doubting and questioning and looking for the proof. And that’s what he was made to do. It’s what we were made to do. God made us to do that: God made us to explore and to test and eventually to understand; it’s part of our job as human beings; we are here to explore and to learn and to grow in our understanding of the mystery of life. And if we are doing that at all well, we ought to be better prepared than Thomas was to understand that bodies can be raised and life can be transformed and that the piece of bread we are given at the altar is not simply a mystery beyond understanding but just one more of those places where the simple divisions break down and the things that separate us from God are overcome and the material – if we still want to use that language – reveals the spiritual, reveals deeper levels, other dimensions of God’s creation.

If you read about saints and poets, it’s surprising, I think, how often they see evidence of God not in some great burst of light and glory but in simple, material things: a rock, a stream, a daffodil, a leper. A sacramental faith should do that for us: it should send us out into a world the great English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins described as “charged with the grandeur of God.”

“The world is charged with the grandeur of God,” he wrote,

“It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;”

I go for a walk every afternoon if I can and stop often to take out my iPad and take a picture of someone’s small front yard garden: the glory of God in the Sunset. I don’t take a picture but I see God also in an occasional homeless person huddled against a wall on Noriega Street or 19th Avenue: God present in the pain of this world as well as the glory.

We need to go out from the church – when we get back to it again – our from our homes after this time of prayer – to have our eyes opened like Thomas’ to see God again and again in this world God made, in this life that God entered, and to say again and again the same words Thomas said: “My Lord and my God.”

What can I believe? What can you believe?

Suppose a friend tells you, “There’s a sale at Staples today: they have iPads at 10 cents a piece. Now, you trust your friend, but you have to ask: “Are you sure? Did you see it yourself?” Is there some trick to it, some qualification like: the first five customers, or until noon yesterday, or if you buy five six packs of beer first? We just instinctively, and out of long experience, weigh what we hear by a number of factors: we balance the outlandish claim against past experience, against importance to us, against what we know about the real world, against probabilities of various sorts – and then we believe or not, depending.

If someone tells you later today that Donald Trump has announced his candidacy for 2024, I expect you’ll believe it with no questions asked. Some things are not a surprise. So: what can I believe and how firmly can I believe it? I think these are fundamental questions we deal with daily. But Thomas in today’s gospel reading was asked to believe something on which life depends and on three grounds: first what he heard from others, secondly what he could see for himself, and thirdly what he could actually touch. Three senses: hearing, seeing, feeling.

The first sense, hearing, he was sure was not enough. I don’t think it ever is when something’s important. Hearsay evidence doesn’t carry much weight and it shouldn’t. If you ever played a game of telephone as a child – you know: you whisper something to someone who whispers it to the next who whispers it to the next and what started out as potatoes at one end winds up as baloney at the other. Who knows what will come out at the other end of the chain?

I remember a news report, back when Barack Obama was running for the first time and reports were being spread that he was a Muslim. A television reporter was shown asking some men in a midwestern diner who they would vote for and why and one of them said he couldn’t vote for Obama because Obama was a Muslim. And the reporter said, “Well, but he isn’t a Muslim.” And the man in the diner said, “But what’s what I’ve heard.”

So hearing isn’t very reliable and Thomas knew that and wasn’t about to rely on it, nor was he even ready to be satisfied by seeing. “Seeing’s believing” is the old saying but any magician knows that the hand is quicker than the eye and we can think we see something that’s not really there at all. In an age when  virtual reality is a familiar idea, when we can project holographic images and show someone as present who’s actually in Bangladesh, when we can go to the movies and be shown special effects that are totally unreal and untrue, seeing is not believing.

virtual reality is a familiar idea, when we can project holographic images and show someone as present who’s actually in Bangladesh, when we can go to the movies and be shown special effects that are totally unreal and untrue, seeing is not believing.

The result is that touch and feel become more important than ever and especially because of what we are as human beings. I am a flesh and blood, material human being. I may see things, hear things, imagine things, but it’s touch that brings me into relationship with what I am: flesh and blood, material, capable of banging into things, being hurt by the collision; that’s reality as we experience it. That’s what we can believe. When I pound on the pulpit (which I can’t do on zoom and don’t often do anyway!) I know this is real, it’s here, I can feel it.

Now, this story about Thomas tells us several things but one that’s important is the place of the sacraments in our lives. Our worship is not just sight and sound as some worship is. We don’t go to church just to listen and maybe sing as some worshipers do but to taste and touch and feel. If I were an Evangelical, I’d get along a lot better with zoom than I can as an Episcopalian, a Christian in the Catholic tradition. I want sacraments. I want to be wholly involved: hearing, yes, but also tasting and touching and feeling. To make new members of the church we don’t just announce it, we pour water over them. We don’t just pronounce two people husband and wife, we join their hands at the altar and wrap a stole around their hands. As soon as possible, we will once again use bread and wine to know Christ’s presence here. Jesus says to us as he said to Thomas, “Reach out your hand and feel this bread, touch my body, and know that I am with you still.” Christianity is about God’s relationship with the material world.

At the center of our faith is the fact that God came into this material world that God created and lived in it in real flesh and blood. Our faith is an incarnational faith. God is real for us in a way that no other faith can claim: God took human flesh, became real for us in the ultimate way, and the celebration of Easter is about the resurrection of that flesh, that human body. I keep meeting people who think that Christians believe in the immortality of the soul and I guess some do, but that’s not what the Creed says. The Creed says it’s about the body, the resurrection of the body. It’s not about a soul that we can’t even see or hear let alone touch; it’s about a reality that we can understand, that’s tangible, that we can touch and taste and feel. Easter is not about spiritualism; it’s about materialism.

Spirituality is very popular these days but fewer people are going to church. They’re two different things. Spirituality is what it is, but Christian faith is something much more. I like to quote the former Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple, who said, “Christianity is the most materialistic of the world’s religions.” And it is. It’s a religion that has to do with God here, God known to us in flesh and blood and therefore concerned with flesh and blood, concerned with problems of poverty and hunger. It’s not a religion of escapism.

So I could simply preach about the sacraments today and how central they are to Christian faith. But what I want to do is to look more deeply at the whole question of matter and spirit and ask what we mean by that classic division between spiritual and material anyway. And what I want to suggest is that this standard division between material and spiritual is really out of date, in a post-Einstein world. I don’t believe we know anymore where the border is between the physical and the spiritual. When scientists talk about quarks and mesons and subatomic particles and fields of force and dark matter that may be the commonest substance in the universe and yet is undetectable so far by human intelligence, where would you draw the line between what’s physical and what’s not?

The Prayer Book defines a sacrament as an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace as if there were two kinds of reality, the material one you can taste and touch and the spiritual one you can’t. In the middle ages, there was a clear line between material and spiritual and everything had to be one or the other. Christianity with it’s talk about incarnation and sacraments tried to cross that line but it still left us in a divided world in which the things that we knew about from every day experience were the material things while the things that mattered were the things we couldn’t know directly. But we live after Einstein and we know that the material world isn’t all that solid. The solid walls of your house, we know now, are made up of atoms that are made up of electrons and even smaller particles like meson composed of quarks and anti-quarks and more, some of which we know only as theory and have never really been seen and certainly not touched.

Worse than that, not only is there no way to taste or touch or see the ultimate elements but they can be turned into immaterial energy, because E=MC squared as I’m sure you know and MC squared=E. The wood of the pew you sit on in church can burn and become heat energy and the energy of the sun can be transformed into the green plants that push up out of the soil. Worse still than that, the material universe includes what science calls “forces.” We all know about gravity but then there’s the electromagnetic force and there are two types of nuclear force. And at the cutting edge of science you actually find them using terms like “weird” and “spooky” as technical terms as the scientists try to reduce the material world to something they can understand. But the physical world keeps escaping from their experiments and leading them out into a world that sometimes seems more spiritual than material.

What kind of world is it in which scientists use terms like “weird” and “spooky?” I saw a book review in the New York Times some while back that talked about “wildly imaginative” new ideas about the basic structure of matter. It said that the fundamental problem with these ideas is that there’s no way to test them. But science is about testing and if you can’t test it, how can it be science? The boundary between the material and the spiritual seems to have disappeared. Which takes us back to Thomas, because that was Thomas’ problem too and the problem of the Christian church when it tried to understand and explain the eucharist and the sacraments.

But isn’t that what we should have expected to learn as we explored God’s world? Shouldn’t we have expected to learn that it was all one and that the hard cold rock in our garden which God made is ultimately simply one more expression of the ultimate reality which is God? Isn’t love one form of reality and aren’t rocks another? And aren’t both of them evidence of the creativity of the same God? When we take the bread of the eucharist in our hands, that too can be analyzed as matter: It’s composed of flour and water; but those ingredients are composed of atoms of carbon and hydrogen and so on, and that’s potential energy. If you burn it, heat is created. If you eat it, the body absorbs the energy. The bread is material, it’s physical, but that means it’s also potential energy and it’s transformed into energy when we eat it. But if you come here with faith, there’s another kind of energy at work as well, as Christians have always known even though they have often disagreed as to just what that energy is. But whatever language you want to use, it has to do with the way Christ comes to us in our worship and prayer renewing our lives by his life. You, a child of God, are joined with God and your life is renewed.

Now, Thomas didn’t know all that when he tried to understand what the other disciples were telling him. He thought he had it all figured out. His world was material and that was all. He thought that when matter died that was an end of it. Thomas didn’t know about Einstein. And Thomas didn’t really understand that the world is one, that God is one, that all life and matter and creation exist only because of God and there are no boundaries except the ones we make in our heads. Thomas, you might say, was the original scientist, doubting and questioning and looking for the proof. And that’s what he was made to do. It’s what we were made to do. God made us to do that: God made us to explore and to test and eventually to understand; it’s part of our job as human beings; we are here to explore and to learn and to grow in our understanding of the mystery of life. And if we are doing that at all well, we ought to be better prepared than Thomas was to understand that bodies can be raised and life can be transformed and that the piece of bread we are given at the altar is not simply a mystery beyond understanding but just one more of those places where the simple divisions break down and the things that separate us from God are overcome and the material – if we still want to use that language – reveals the spiritual, reveals deeper levels, other dimensions of God’s creation.

If you read about saints and poets, it’s surprising, I think, how often they see evidence of God not in some great burst of light and glory but in simple, material things: a rock, a stream, a daffodil, a leper. A sacramental faith should do that for us: it should send us out into a world the great English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins described as “charged with the grandeur of God.”

“The world is charged with the grandeur of God,” he wrote,

“It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;”

I go for a walk every afternoon if I can and stop often to take out my iPad and take a picture of someone’s small front yard garden: the glory of God in the Sunset. I don’t take a picture but I see God also in an occasional homeless person huddled against a wall on Noriega Street or 19th Avenue: God present in the pain of this world as well as the glory.

We need to go out from the church – when we get back to it again – our from our homes after this time of prayer – to have our eyes opened like Thomas’ to see God again and again in this world God made, in this life that God entered, and to say again and again the same words Thomas said: “My Lord and my God.”

April 2, 2021

The Cross Makes a Difference

A sermon preached to the congregation of All Saints Church, San Francisco, on April 2, Good Friday, 2021

They passed a law in Georgia last week that makes it a crime to be a Christian. Did you see that? They made it a criminal offense to give food or water to someone standing in line to vote. Seriously? They really did that? Yes, and I’ve been trying to think ever since how I can get to Georgia next time they have an election to give someone in line to vote a cup of cold water.

I hope I don’t need to. I hope the line of people bringing food and water to people waiting to vote is longer than the line of people waiting to vote. I hope they run out of cars to take people to jail for doing it and run out of police to arrest them.

Jesus said, “. . . if you give even a cup of cold water to one of the least of my followers, you will surely be rewarded.” (Matthew 10:42)

Go to Georgia to claim your reward! Faith has consequences. It’s Christianity 101 – basic Christianity – that faith has consequences, but it’s now illegal in Georgia to do what Jesus taught us to do. But it may remind us of some simple and basic aspects of being a Christian. It doesn’t require deep thought; you don’t have to do anything complicated: spend hours on your knees or in the lotus position or recite ten Hail Mary’s before breakfast – no, do all that if you want and if you find it helps you, but Jesus said nothing about that; he only promised that you will not lose your reward if you just give someone a cup of cold water in his name.

I like the fact that here on Good Friday, while we read the awful story of how Jesus was crucified, we also read a passage from one of the least read but most important books of the Bible, the Epistle to the Hebrews, because while the Gospel reading confronts us with the crucifixion in excruciating detail, the Epistle reading reminds us that faith has consequences, faith has consequences, faith makes a difference, and there are simple, basic everyday things we ought to be thinking about, ought to be doing something about, because it changes lives; changes every day we live; changes every relationship; changes us. Here’s part of that same passage in a simple translation called “The Bible in Basic English:”

Hebrews, because while the Gospel reading confronts us with the crucifixion in excruciating detail, the Epistle reading reminds us that faith has consequences, faith has consequences, faith makes a difference, and there are simple, basic everyday things we ought to be thinking about, ought to be doing something about, because it changes lives; changes every day we live; changes every relationship; changes us. Here’s part of that same passage in a simple translation called “The Bible in Basic English:”

“. . . let us be moving one another at all times to love and good works; 25 Not giving up our meetings, as is the way of some, but keeping one another strong in faith; and all the more because you see the day coming near.” (Hebrews 10:24-25)

“Let us be moving one another to love and good works, not giving up our meetings as some do but keeping one another strong in faith.” That’s what’s essential, because the Crucifixion has consequences, it makes a difference. I have sometimes spent three hours on Good Friday preaching about the crucifixion, and there’s value in that: remembering how much God loves us. But then what? Then what? If we go away saying, “How awful” and no more, maybe it wasn’t awful enough, because we haven’t gotten the message. It’s a very simple message summed up in a familiar childhood hymn: “He died that we might be forgiven; he died to make us good.” “He died to make us good.” He died to make a difference. He died to change human lives. He died to change us.

There’s a kind of Christianity that centers almost exclusively on the cross. I had an evangelical friend in college who thought he hadn’t heard a sermon if he didn’t hear about the cross. Well, yes, but what about the consequences of the cross? I’m not sure we’ve really heard about the cross if we haven’t heard about the difference it makes, if we haven’t heard about its purpose and how it changes lives. It’s great to accept Jesus as your savior, but it needs to make a difference, it needs to change lives, it needs to motivate and strengthen us to go out and not just think about Jesus, but to be guided and motivated and directed and, yes, inspired, to be Jesus in our world, to ignore the selfish and even hostile forces around us, and just make sure we make a difference because Jesus makes a difference, because the cross makes a difference, and at the simplest, most every day level the cross requires us to make a difference ourselves.

March 20, 2021

“We would see Jesus”

A sermon preached to the congregation of All Saints Church, San Francisco, on the 5th Sunday of Lent, March 20, 2021, by Christopher L. Webber.

I remember reading an interview years ago with a famous Russian writer who was asked what he would do if Tolstoy or Dostoevsky moved in across the street: would he be anxious to meet him? No, he said; he had read their books and had no need to meet them. So what would you say if the opportunity came to meet Jesus: would you say, “No, thanks, I’ve read the Bible and that’s enough?” Some have said that after you die you will first of all come face to face with Jesus.

The bishop who ordained me said he had heard that, and he said, “I think I’d rather be fried.”

Well, I understand that. When you stop to think about your life – what you know Jesus called