Christopher L. Webber's Blog, page 3

October 5, 2019

Faith and Mulberry Trees

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, on October 5, 2019.

Hy – per – bo – le.

That’s the key word to understand the gospel reading today. Hyperbole. Look it up on line and you’ll find lots of definitions and lots of examples.

Hyperbole is defined as “an exaggerated statement” or “extravagant exaggeration” or “a claim not meant to be taken literally.” I think we all probably use hyerbole just about every day. I could say “we use it all the time” but that would be hyperbole.

If you say to someone: “I’ve told you to clean your room a million times!” That’s hyperbole. Or if you say, “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse.” That’s hyperbole. You don’t expect someone to put a horse on your dinner plate. Or if you say, “That suitcase weighs a ton.” That’s hyperbole. You don’t expect someone to get out the scales and weigh it. And if they do, you’re going to say, “Oh, come one; you knew what I meant.” And they did. They knew exactly what you meant. Because everybody understands hyperbole even if they never heard of it. It’s hyperbole; hyperbole. It’s exaggeration for effect, to make a point dramatically.

Jesus used hyperbole. He probably thought it was pretty obvious what he was saying. But he probably never met a fundamentalist. If I said, “Faith can move mountains” you would know what I meant and you would know it’s true. And you wouldn’t expect me to relocate Mt. Tam to prove it. But somehow when Jesus says something like that we totally forget how language is used. So we read the gospel this morning and hear Jesus say:”If you had faith the size of a mustard seed, you could say to this mulberry tree, `Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it would obey you,” and it worries us,  because for some reason we think that if Jesus said it, we have to take it literally – and if we can’t relocate mulberry trees that our faith is too small.

because for some reason we think that if Jesus said it, we have to take it literally – and if we can’t relocate mulberry trees that our faith is too small.

I went on line looking for examples of fundamentalists who had taken Jesus literally and had moved mulberry trees. I didn’t find any but I did find some who are worried by this text because they don’t know about hyperbole. And it was kind of funny. I found one who said, “There’s a mulberry tree right outside my window,” and he’s never yet had a reason to move it but he sort of implied that he could if he really wanted to. I can think of lots of reasons he should try it. Think how many converts he’d make. I found one on-line preacher who tried to talk around it by blaming his congregation: “I haven’t moved any mulberry trees this week and I bet you haven’t either.” But that’s not the point! That misses the point.

I don’t know where the nearest mulberry tree is, but I think most people who have them would be happy to cast them in the sea because they’re messy trees. I remember living in a town where there was one just down the street and we learned to stay away from it in summer. They produce these  tasteless berries that mess up your sidewalk and get on your shoes and stain your clothes. Worse, the male mulberry tree produces pollen that is terrible for people with asthma. Lots of cities have actually banned them for that reason. So if there were a shortcut way to cast the things in the sea they’re be a line of people ready to help. But they would need machinery, not faith. Faith can do lots of good things for you but it’s not about moving mulberry trees.

tasteless berries that mess up your sidewalk and get on your shoes and stain your clothes. Worse, the male mulberry tree produces pollen that is terrible for people with asthma. Lots of cities have actually banned them for that reason. So if there were a shortcut way to cast the things in the sea they’re be a line of people ready to help. But they would need machinery, not faith. Faith can do lots of good things for you but it’s not about moving mulberry trees.

I wish we had Hebrews 11 to read this morning, because that’s the passage we need to go with this gospel. Hebrews 11 defines faith and Hebrews 11 describes faith. It defines it as “the evidence of things not seen.” I can’t see faith but I can see what it does. I can’t see faith but I can see faithful people: I can see you here this morning because you’re faithful. So there’s evidence of faith even though we can’t see it.

Hebrews 11 describes faith by remembering one by one the Biblical characters who acted in faith. It starts with Moses: By faith Moses identified himself with the enslaved Hebrew people, by faith they passed through the Red Sea by faith they conquered the promised land by faith they endured hardship and suffering mocking and flogging, chains and imprisonment And this great cloud of witnesses, Heb rews 11 tells us, of whom the world was not worthy gives us courage to go ahead, gives us courage to move not mulberry trees but doubt and discouragement and hardship and suffering, move them out of the way, cast them in the sea, and keep going because we have faith in God’s promises. Faith enables us to move on, to keep going, because God has given us a promise greater than any tricks with mulberry trees.

rews 11 tells us, of whom the world was not worthy gives us courage to go ahead, gives us courage to move not mulberry trees but doubt and discouragement and hardship and suffering, move them out of the way, cast them in the sea, and keep going because we have faith in God’s promises. Faith enables us to move on, to keep going, because God has given us a promise greater than any tricks with mulberry trees.

The disciples said, “Increase our faith.” I’m with them. I’d like a double dose. But Jesus doesn’t really answer them. He tells them if they had even the smallest bit of faith, they could do great things. And then he moved on down the road that led to Jerusalem and they followed him. See? That’s faith: They followed him even though they didn’t know where he was going, even though they might have guessed it wouldn’t be easy. But it turned out that they had faith enough to change the world. Forget about mulberry trees. They changed the world. And it wasn’t because he taught them any special tricks or secret formulas. They got it by walking along with him day after day, day after day. And that’s where we get it too. By being here, by saying our prayers, by reading the Bible, by following Jesus on the path in front of us. Faith comes by walking with Jesus and if we do that we’ll have enough. God promises us life: changed life now, and new life hereafter. All God asks of us is faith, faith the size of a mustard seed to accept that promise and live by that faith..

September 27, 2019

NOW AND THEN

A sermon given at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, California, on September 29, 2019, by Christopher L. Webber.

I wish we could read the story of Dives and Lazarus on Easter Day.

We come to church on Easter Day to give thanks for the gift of eternal life, life after death, Resurrection life – with happy, upbeat hymns and Easter eggs and chocolate bunnies and wouldn’t it be good to have this story with a few more specifics about eternal life? about the rich man and the poor man, about Dives and Lazarus? who died and went elsewhere. Both of them were given eternal life but not in the same place and that might be worrisome.

Does it worry you? I’m getting old enough that I have to worry. I pay for my living space a month at a time. More and more people live to be 90 and even 100, but not 110. They’re working on it, but we’re not there yet. And even 150, which some think is someday possible, is a blink of an eye to eternity. Primitive human beings were honoring their dead with burial and burying useful tributes in the  grave 100,000 years ago and that’s a long time, but even that is not eternity, not eternity. Eternal life is a long time. This life is not a long time. whether it’s three score years and ten or ninety-five, or one hundred and ten, it still has an ending and this morning’s parable puts that ending in graphic terms: Lazarus in the bosom of Abraham and Dives in flames.

grave 100,000 years ago and that’s a long time, but even that is not eternity, not eternity. Eternal life is a long time. This life is not a long time. whether it’s three score years and ten or ninety-five, or one hundred and ten, it still has an ending and this morning’s parable puts that ending in graphic terms: Lazarus in the bosom of Abraham and Dives in flames.

I have two points to make:

1 – God cares how we use our money

2 – Eternal life is real

So Point One is that there is a destiny, we’re going somewhere. We’re here for a purpose. And there’s a loving God who gives us that purpose. And it’s not about how much you can pile up. Have you seen the stories about the family who owned the company that made oxycontin that killed however many people – thousands and thousands – but made one family rich, filthy rich. And when the government began to catch up with them they transferred billions to secret accounts. It’s blood money; but they’re hanging onto it. Like Dives. Eat, drink, and be merry – and hope the Feds don’t get you, and hope there’s no hereafter because if there is, they’re in big trouble. God cares how you use your money. God cares how YOU use YOUR money. I don’t know whether there are literal flames below or not – I’ll come back to that – but I know I don’t want to face my creator with blood on my hands. And I’m not sure there isn’t.

How does the government use my money? To build a wall, to incarcerate women and children fleeing conditions our policies helped create. We spend more money on bombs and guns – military – than  anything else, and how much good does it do? But I am a citizen of a country that builds walls and makes bombs and I may or may not have voted for a particular candidate but did I work for someone else or sit on the sidelines? I’m a citizen and I’m responsible.

anything else, and how much good does it do? But I am a citizen of a country that builds walls and makes bombs and I may or may not have voted for a particular candidate but did I work for someone else or sit on the sidelines? I’m a citizen and I’m responsible.

But forget the government, how do I myself spend my money? I donate to Episcopal Relief and Development every Christmas and I know they do good things, but I spend more on myself every month for things I don’t really need. Is my lifestyle more like Dives or Lazarus? Notice that nothing is said about who went to church or synagogue or mosque – only one thing counts in this story that Jesus told: Dives had the good things all his life and he never shared so much as the crumbs with the poor man at his gate. And that settles it. That does it. That’s all that matters.

How do you and I measure up? Did I – did you – do something about the needs around us while we had time or did we not? What charities do you support? And how will you vote in this next election? Will you ask what’s in it for me or are you asking, How can we as a country do most for those with the most needs whoever and wherever they may be?” Are we asking which candidate will lower my taxes most or which candidate shares my values most fully in terms of human need? This country perhaps is Dives and perhaps Honduras is Lazarus.

How should we respond? “Stay away from my door?” “Build a wall?” People who think you can separate church and state need to look at the Bible. It’s a political document; it’s about God at work in history. Jesus talked often about money, about wealth and poverty. God cares and God wants us to care. And when you get a stewardship letter sometime in the next few weeks we need to consider our response in these terms: in the light of eternity: sub specie aeternitatis. So let me also say a word or two about that: about eternity and eternal life.

And notice also that Lazarus gets named in the story, but not the rich man. Names matter. And the poor man got no recognition from the rich man, but Jesus only names Lazarus. The rich man is just another rich man: met one, you’ve met them all. Somewhere later on in the Middle Ages they began calling the rich man “Dives,” the Latin word for “rich.” Maybe his name was Richard and they called him Rich for short. God, I believe, knows the rich man also by name but Jesus doesn’t give him a name. He’s just “a certain rich man who fared sumptuously every day.” As I do. As most of us do, although there are homeless men and women lying not far from our doors. But Lazarus is given a name to make the point: the Good Shepherd knows his sheep whether the world does or not.

Second, think about the picture of flames and all that. I don’t expect the scene painted in the gospel to play out in real time, or at the end of time. I think pearly gates and raging fire – or, perhaps, as Dante saw it, a place of terrible cold – are useful images. Perhaps they are, but I know perfectly well that whatever comes next is beyond picturing, beyond imagining, because my imagination is so narrowly limited by the familiar things of tis earth. The Bible pictures heaven as Jerusalem – only better. You might think of it as an infinite golf course or an endless Mozart concert. You might see it as a choice between Tahoe and Arizona. Our imaginations are too small. But the picture the gospel gives us, I think, is a useful reminder all the same that how we live matters. It matters.

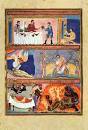

Speaking of the picture the Bible gives us, let me end with a word about the picture that came with your Bulletin this morning. I printed up some pictures because, they say, one picture is worth a thousand words. It almost doubles the length of the sermon. But the passage we read this morning describes Lazarus with Abraham. It says that Dives saw Abraham far away with Lazarus “by his side.” But that’s not what the Bible says. Some of us are old enough to remember the King James Version that says Dives saw Abraham “afar off and Lazarus in his bosom.” So the modern translators were squeamish about that and we get “by his side” Instead of “in his bosom.” But what St Luke wrote was “En tois kolpois autou” – “In his bosom.” You can look it up. So that’s why I got that picture printed. There’s Lazarus: maybe we could say he’s “in Abraham’s lap” and all the other souls are lined up to get their turn. It’s very real and very physical and that’s important, really important.

Speaking of the picture the Bible gives us, let me end with a word about the picture that came with your Bulletin this morning. I printed up some pictures because, they say, one picture is worth a thousand words. It almost doubles the length of the sermon. But the passage we read this morning describes Lazarus with Abraham. It says that Dives saw Abraham far away with Lazarus “by his side.” But that’s not what the Bible says. Some of us are old enough to remember the King James Version that says Dives saw Abraham “afar off and Lazarus in his bosom.” So the modern translators were squeamish about that and we get “by his side” Instead of “in his bosom.” But what St Luke wrote was “En tois kolpois autou” – “In his bosom.” You can look it up. So that’s why I got that picture printed. There’s Lazarus: maybe we could say he’s “in Abraham’s lap” and all the other souls are lined up to get their turn. It’s very real and very physical and that’s important, really important.

Don’t let people soften it up by talking about souls. Jesus never talked about souls nor did Paul. They talked about the resurrection of the body. Not, of course, these particular atoms which are new every seven years anyway, but what Paul calls a “resurrection body.” Buddhists believe in immortal souls but Christians believe in the resurrection of the body: a resurrected body that Abraham can embrace. Bodies matter – now and hereafter – bodies matter. We are physical beings with physical needs, and we will be judged hereafter by how we cared for those needs – and especially the needs of others, those lying at our gate, those outside the wall. We come here, and form a community and support each other in this brief pilgrimage and we need to do what we can to reach out to Lazarus – while we have time.

August 17, 2019

Making History

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at All Saints Church, Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco, on August 18, 2019.

I meet every week with a small Bible study group where I live and we’ve been making our way through the so-called history books: 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings. And the Bible is unlike the sacred scriptures of any other faith because of books like those, books of history. Much of the Bible is history, history, not teaching, or, rather, teaching with history. If you’re into comparative religion you can look at the Muslim Koran and the Hindu Bhagavadgita or the Buddhist Pali Canon and Agama and you will find wisdom but you will not find anything like the history books of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures. Even the Old Testament this morning provides history indirectly as a parable.

Today we have to look at the first New Testament reading to get the Old Testament history summarized. It has to be summarized here, the author says,

For time would fail me to tell of Gideon, Barak, Samson, Jephthah, of David and Samuel and the prophets– who through faith conquered kingdoms, administered justice, obtained promises, shut the mouths of lions, quenched raging fire, escaped the edge of the sword, won strength out of weakness, became mighty in war, put foreign armies to flight… Others suffered mocking and flogging, and even chains and imprisonment. They were stoned to death, they were sawn in two, they were killed by the sword; . . . (They were) destitute, persecuted, tormented– of whom the world was not worthy.

The passage ends by saying:

Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight  and the sin that clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us . . .looking to Jesus the author and perfecter of our faith

and the sin that clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us . . .looking to Jesus the author and perfecter of our faith

One modern translation puts it: Jesus “the pioneer and perfecter of our faith.” I like that: “pioneer and perfecter.” I like that because Americans know about pioneers: people who range out ahead, exploring new land, settling, finally, even places like California and maybe the moon and Mars. Human beings are pioneers by nature. Think of the very first Americans crossing the Bering Strait – long before Jamestown or Plymouth – and moving down the west coast of the continent and spreading out across America first from west to east: first California, then New York, – that’s not the sequence they taught me in school but that’s what those first Americans did and not stopping in California either but moving also further south, crossing the border into Mexico without a wall to stop them. And all of that is part of the larger chronicle of which the Bible gives us only snippets, bits and pieces, but significant bits and pieces in which we can see more clearly the things we need to know about human society and human nature, things God wants us to learn and knows that we can learn by experience better than books. Our sacred book, our Bible, does have teaching, yes, of course, but grounded always in human experience, in history. We know because we’ve been there, we’ve done that, we’ve learned from events.

We’ve had some history lessons in recent weeks, haven’t we? Not for the first time. How many times do we need to be taught the same lesson before we act? Take chapter 4 of the Bible, for example: the story of Cain and Abel? In the larger picture – this is a personalized summary of what happens when shepherds and farmers, ranchers and farmers, have their eyes on the same land. But Abel was a keeper of sheep And Cain was a tiller of the soil. It’s condensed history: the Jews come on the scene as keepers of sheep moving into farm land in Canaan and fighting with the native farmers for that land. You can’t grow lettuce if the cattle aren’t fenced out and you can’t raise cattle if somebody fenced off the grazing land. So Cain and Abel happened, and it happened again as the west was settled, first by ranchers until human beings recognize that God made human beings for a purpose, that God made them to live together in peace and they need to learn the art of compromise and find ways to settle disputes before it comes to blows.

There came a time, long ago, when human beings understood that well enough to sum it up in four words: Thou shalt not kill. And later they learned an even better way to say it: love your neighbor as  yourself. We learned that out of history by sad experience – or started to learn it because we’re not there yet, are we? Columbine, Parkland, Sandy Hook, Gilroy, Dayton, El Paso – the list gets longer and longer. How long, O Lord, how long?

yourself. We learned that out of history by sad experience – or started to learn it because we’re not there yet, are we? Columbine, Parkland, Sandy Hook, Gilroy, Dayton, El Paso – the list gets longer and longer. How long, O Lord, how long?

Martin Luther King, Jr. confronted that question again and again. If you are black in America, you’re bound to ask. In one of his greatest sermons, King said,

I know you are asking today, “How long will it take?” Somebody’s asking, “How long will prejudice blind the visions of men, darken their understanding, . . . Somebody’s asking, “When will wounded justice, lying prostrate on the streets of Selma and Birmingham and communities all over the South, be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men?” Somebody’s asking, . .. . How long will justice be crucified, and truth bear it?” I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, because “truth crushed to earth will rise again.”

How long? Not long, because “no lie can live forever.” How long? Not long, because “you shall reap what you sow.” How long? Not long: How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. How long? Not long, because: Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord . . .

And our eyes have seen the glory in the battles raging now in the streets of Charlottesville and El Paso and still in Ferguson, Missouri, where American citizens are still stopped for driving while black as a good friends of mine have been even on Long Island and in northwestern Connecticut just a few years ago. It happens. It’s happening right now. But what we see when these dreadful things take place – what we’ve seen when people come together in a common grief – what we’ve seen is always a renewed determination to work and pray for something better. Not thoughts and prayers, Not hope and pray. No, but work and pray. Make a commitment to change, make a commitment to work and give to the city that has foundations. a commitment to the kingdom of God. A commitment to work together in faith remembering, remembering what God’s people have accomplished in faith, what we read about this morning:

By faith the people passed through the Red Sea as if it were dry land, By faith the walls of Jericho fell . . .

By faith we will move on. And we read last week in this same passage from Hebrews about those others:

who confessed that they were strangers and foreigners on the earth, for people who speak in this way (we read) make it clear that they are seeking a homeland, that they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God; indeed, he has prepared a city for them.

Yes, and some people are willing to wait, but I think God gives us the vision of that heavenly city to make us less patient with this one. I think we wouldn’t mind so much what’s happening if we didn’t have a vision of a different world, a better community. But we do and that’s why we’re not willing to settle for things as they are.

Dorothy L Sayers once said, “The best kept inns are on the through roads.” That was a hundred years ago. The best kept inns today are likelier to be at the airports than the train stations. We’re people in a hurry and now we know what’s possible and we’re not willing to wait. It’s because we have that vision that the patterns of life are being challenged and that’s frightening to some people who don’t share the vision, who think they can turn the clock back and build walls and deny travel documents to stop change from happening. It can’t be done. God is at work. Mine eyes have seen the glory – the glory of the vision of a nation where color no longer matters and ethnicity no longer matters but love matters and justice matters and peace matters and the faith that we can get there is the faith proclaimed in the readings last week and this: the faith that is shaking the foundations to tear down the city of human pride and build up the city of God

is at work. Mine eyes have seen the glory – the glory of the vision of a nation where color no longer matters and ethnicity no longer matters but love matters and justice matters and peace matters and the faith that we can get there is the faith proclaimed in the readings last week and this: the faith that is shaking the foundations to tear down the city of human pride and build up the city of God

August 10, 2019

Don’t Worry!

A sermon for the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, on August 11, 2019, by the Rev. Christopher L. Webber.

“Do not be afraid, little flock, for it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom.” St. Luke 12:32

It se ems to me in the nature of things that sermons should make you worry. My job as a preacher, I sometimes think, is to make people worry. Either there is something you’re supposed to learn or something you’re supposed to do or maybe there are other people we should worry about because they aren’t up to snuff or need converting or something. So the sermon tells us things to worry about.

ems to me in the nature of things that sermons should make you worry. My job as a preacher, I sometimes think, is to make people worry. Either there is something you’re supposed to learn or something you’re supposed to do or maybe there are other people we should worry about because they aren’t up to snuff or need converting or something. So the sermon tells us things to worry about.

I guess it goes with the territory. All this last month, we’ve been reading passages that set standards and point directions: “Love God,” “Listen to God’s word,” “Don’t set your mind on wealth” – – that kind of thing: things to worry about.

So it’s nice to come to church in the middle of August and hear a Gospel that says, “Don’t worry.” The Gospel said, “Don’t be afraid, little flock…” but, you know, right there is one of the things we worry about: we are a little flock. 25 or 30 people on a typical Sunday is what percent, do you suppose, of the neighborhood. Does anyone of our neighbors on this street come here on Sunday? Just to keep the church doors open takes a certain number of committed people, and generally just a few more than seem to be on hand.

So we do worry. We’d like a bigger flock. Even on a national basis, two or three million Episcopalians in a population of over 300 million is not good odds. And worldwide, 85 million Anglicans in a population of several billion is even worse. But even if you take the biggest church, the Roman Catholic, maybe one third of the world’s Christians and easily a quarter of the population of California – with all those people they don’t have enough priests to hold services in many of their churches nor can they avoid really serious divisions over the direction the church should go. And they are closing churches.

300 million is not good odds. And worldwide, 85 million Anglicans in a population of several billion is even worse. But even if you take the biggest church, the Roman Catholic, maybe one third of the world’s Christians and easily a quarter of the population of California – with all those people they don’t have enough priests to hold services in many of their churches nor can they avoid really serious divisions over the direction the church should go. And they are closing churches.

I talked last week to a friend who spent most of his life in Pittsburgh as an active member of a large Roman Catholic parish with multiple priests – it’s closed.

So Christians are, and maybe always will be, a little flock: seldom overwhelming in numbers, seldom seeming to have the resources or manpower needed, and yet here is Jesus saying, “Don’t worry.”

It’s not surprising actually that Jesus would need to say this. Jews had been worried about numbers for centuries before Jesus came. Way back in the Book of Deuteronomy we find Moses saying, “It was not because you were more numerous than any other people that the Lord set his heart on you and chose you, for you were the fewest of all peoples.” There is a feeling of smallness and inadequacy right from the beginning, but always the reassurance that God does not save by numbers. So relax; God promises that we will always have the resources we need. Not the resources we might like to have or the resources that would make us feel confident about doing the job. But enough. And it always has been enough. That’s why we’re here.

They say th at God made the universe – – the sun and stars and planets beyond any counting – – out of the tiny ball of matter which exploded out into everything that exists, and here is this tiny earth floating along in infinite space, a mere grain of dust in the expanse of the universe, but big enough, big enough for God’s purpose. Don’t be afraid. It’s enough.

at God made the universe – – the sun and stars and planets beyond any counting – – out of the tiny ball of matter which exploded out into everything that exists, and here is this tiny earth floating along in infinite space, a mere grain of dust in the expanse of the universe, but big enough, big enough for God’s purpose. Don’t be afraid. It’s enough.

We have a way of borrowing trouble, fearing possibilities rather than realities, and it’s probably part of the human tendency to want to be independent and self-sufficient and in charge of our lives. But we’re not. We are not any of those things. We are not in charge. Neither the President of the United States, nor Bill Gates is wise enough or smart enough or rich enough or powerful enough to control events, much as they might like to, nor are we. But we keep trying and keep scaring ourselves to death at the thought that the situation is not really under control. But you know, what’s scary is not the situation but our presumption. If we hadn’t been trying to go it alone, if we had accepted our status as totally dependent beings, we would have had nothing to worry about except the nature of the One who is in control. And the evidence of that is what the Bible is all about, what the Gospel is all about: that God is good and is in charge and loves us and can be relied on.

Don’t be afraid. that comes first, and why? Because “It is your father’s good pleasure to give you the kingdom.” I wish all the worried people in the world could hear this, really hear it. You know, there are people out there with guns and dynamite who think God’s will depends on them. In the nam e of God they blow up federal buildings and abortion clinics and airplanes and shoot down dozens of innocent people because they don’t trust God, don’t believe God’s promise, or have never heard it. And so they create the violence that is absolutely opposite to all that God wills and promises. Does that make any sense at all?

e of God they blow up federal buildings and abortion clinics and airplanes and shoot down dozens of innocent people because they don’t trust God, don’t believe God’s promise, or have never heard it. And so they create the violence that is absolutely opposite to all that God wills and promises. Does that make any sense at all?

God promises to give us the kingdom. It’s a gift; it would have to be. We ourselves can’t take it or make it. Human beings have been trying to do that now for thousands of years, trying to create the ideal society, and you see what we’ve got. And the societies that do best if you notice, are the ones that are so set up that it’s almost impossible for human beings to get anything done. Dictators can get the trains run on time, but not democracies. Dictatorships can reduce crime and produce unity, rallies of people all shouting the same thing, whether it’s “Heil Hitler” or “Down with the great Satan.”

And yet we worry: “What do I have to do?” “When do I have to do it?” Again, there are churches with answers. One of the first great heresies to shake the church was preached by a man called Pelagius who had the idea that we can save ourselves. There are churches that set rules to follow about doing this and not doing that, and they may all be good rules but they won’t save us. God saves us. And see what Jesus tells his little flock to do? Wait. Just wait. Be like servants waiting for their master to come home. Yes, be on the lookout, stay awake and be alert, remember who you belong to and what you ought to be doing when he comes; don’t wander off and get so engrossed in your own concerns that you forget your primary allegiance. But basically, have an attitude of expectant waiting, joyful expectancy, because what’s going to happen? When the master comes, what will happen? Everyone will run around in a dither trying to meet all his demands? No, not at all. They will open the door and then, Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, he will fasten his belt and have them sit down to eat, and he will come and serve them.” Now isn’t that incredible! He will serve us!

It’s amazing, but that’s the promise: he will serve us. And it must be true because it’s happening already. Every day we wake up and find air to breathe and water to drink and the sun to warm us (well,  sometimes the fog breaks and the sun is still there) and it’s all free of charge, and when we come here to give thanks for all God’s gifts, what happens? God gives us still more: feeds us at God’s own table. And, you know, if we happened to whisper to others what kind of God we know and invited them to come and share the gifts instead of worrying so much, we might even become a slightly bigger little flock.

sometimes the fog breaks and the sun is still there) and it’s all free of charge, and when we come here to give thanks for all God’s gifts, what happens? God gives us still more: feeds us at God’s own table. And, you know, if we happened to whisper to others what kind of God we know and invited them to come and share the gifts instead of worrying so much, we might even become a slightly bigger little flock.

July 26, 2019

God Does Not Give Wetas

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, July 28, 2019.

“If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him!” (St. Luke 11:13)

Ten years ago the Anglican Church of New Zealand produced a new Prayer Book. It got rave reviews on all sides. It’s a beautiful book: beautiful cover, beautiful pages, wonderful art work, red-edged pages in  the center so you can easy find the Eucharist and built-in book marks so you don’t lose your place when you find it. And besides all that it has almost everything not only in English but also in the Maori language.

the center so you can easy find the Eucharist and built-in book marks so you don’t lose your place when you find it. And besides all that it has almost everything not only in English but also in the Maori language.

My wife and I traveled to New Zealand eighteen years ago and we were there on September 11, 9/11, 2001. We were glad to find churches open and services to go to and a chance to use the New Zealand Prayer Book. Quite apart from 9/11, I was fascinated to see that at every service whether there were Maori New Zealanders present or not, some part of the service was always spoken in Maori and everyone seemed to know that language as well as English.

There’s one special section of the book that provides a brief and easy-to-use form of prayer for morning and evening of a seven day week. I’ve begun to use it first and last thing every day as well as the American Prayer Book Morning and Evening Prayer later in the morning and earlier in the evening. The New Zealand form for daily prayer is all in English, but there are sections provided in Maori as well and just one place where a Maori word is used in the middle of an English reading. It’s the same reading we had this morning in the Gospel and found Jesus saying, “If your child asks for a fish, will you give a snake instead of a fish? Or if your child asks for an egg, will you give a scorpion?” In the New Zealand Prayer Book those few verses come up every Monday morning as if we need to be reminded every week – and we probably do – that God knows our needs and won’t give us gifts we can’t use. But in the New Zealand Prayer Book one Maori word sneaks into the English as if it’s just one of those words everybody knows. And probably in New Zealand they do. It says, “Would any of you who are parents give your child a weta when asked for a fish?”

I guess everyone in New Zealand knows what a weta is, but I had to look it up. It’s easy to do on line. And  what I learned is that a weta is one of the world’s largest insects, often bigger than a mouse, and fierce. Go on line and you can find a video of a weta attacking a cat. No, if your child asks for a fish, you will not give them a weta. Nor will God give one to you – unless you go to New Zealand. Thank goodness!

what I learned is that a weta is one of the world’s largest insects, often bigger than a mouse, and fierce. Go on line and you can find a video of a weta attacking a cat. No, if your child asks for a fish, you will not give them a weta. Nor will God give one to you – unless you go to New Zealand. Thank goodness!

The Gospel today is about prayer. There’s nothing more important for Christians to understand than the importance of prayer. St Paul brings it up again and again: He says, “Pray without ceasing,” and he says he himself is praying constantly for the church. And it’s not so much about rewards; it’s not so much about getting something measurable or specific; it’s not about an answer to prayer that you might easily recognize. It’s about the relationship. It’s about building your relationship with God.

What kind of relationship do you have with God? I lived in a community for a number of years where people could give their children whatever they wanted, but sometimes they did that to be rid of them. “You want another toy: fine, here it is. Take it and leave me alone.” There were lots of young people in that community who had everything they wanted, but not what they needed. No, it’s not the gift that matters; it’s the relationship. And in a good relationship good things happen.

The Old Testament shows us that kind of relationship. Do you know the word “chutzpah”? Maybe you haven’t lived in Brooklyn. Look it up on line. It’s a Yiddish term for “unbelievable gall; insolence; audacity, cheekiness, crust, freshness, impertinence, impudence, insolence; the trait of being rude and  impertinent; inclined to take liberties.” For a text book example of chutzpah, read today’s passage from Genesis: It’s the story of Abraham bargaining with God. “If I find fifty righteous people in Sodom,” Abraham says to God, “will you save the city? What about forty? What about thirty? Maybe twenty? How about ten? And each time, God agrees to the bargain and each time Abraham ups the ante until finally God just walks away. But Abraham got what he wanted. He persisted. Nevertheless he persisted. And I think that’s what God wants most of all: the kind of persistence that builds a relationship. The kind of persistence that develops a pattern of prayer: Daily. Frequent. Constant. A life of prayer centered on God’s will.

impertinent; inclined to take liberties.” For a text book example of chutzpah, read today’s passage from Genesis: It’s the story of Abraham bargaining with God. “If I find fifty righteous people in Sodom,” Abraham says to God, “will you save the city? What about forty? What about thirty? Maybe twenty? How about ten? And each time, God agrees to the bargain and each time Abraham ups the ante until finally God just walks away. But Abraham got what he wanted. He persisted. Nevertheless he persisted. And I think that’s what God wants most of all: the kind of persistence that builds a relationship. The kind of persistence that develops a pattern of prayer: Daily. Frequent. Constant. A life of prayer centered on God’s will.

Will you get the gifts you want? Not necessarily. Do you always give children what they want? Not necessarily. But you will give them what they need. You will take them to the doctor for shots and you will take them to the dentist for drilling. It’s not what they want, but it’s what they need. But I am sure you will never give them a weta.

Let me tell you a story. I lived as you probably know for six years in Japan and one day I was driving in Tokyo and I took a wrong turn and got completely lost and found myself driving through a cemetery. On both sides there were the typical Buddhist shrines where ashes are placed. But suddenly I saw on my left some typical western grave stones and some with crosses on them. There wasn’t any traffic, so I pulled over and got out and took a closer look and I was amazed to see that I was standing at the grave of Samuel Isaac Joseph Schereschewsky. Now that may not be a familiar name to you but it was and is to me. It’s one of the great names in the history of the Episcopal Church.

Schereschewsky was born in Lithuania in 1831 in a Jewish family and he was studying to be a rabbi when someone gave him a copy of the New Testament in Hebrew. He studied it and he became convinced that Jesus was indeed the promised Messiah. He went to Germany to study further and after three years he came on to the United States where he was baptized in a Baptist congregation and then went for some reason to a Presbyterian seminary in Pittsburgh to study for the ministry. But after two years there they told him, “You can’t be ordained because you’re Jewish.” So he moved on to New York and found the Episcopal seminary which accepted him without a problem. So he graduated and was ordained and volunteered to go as a missionary to China where eventually they made hm a bishop. He founded a university and began translating the Bible into Chinese but after twelve years he had a stroke that left him confined to a wheel chair. So he moved to Japan and he spent the rest of his life translating the Bible into a basic Chinese dialect using a special typewriter and pressing the keys with one finger of his partly paralyzed right hand.

Schereschewsky was born in Lithuania in 1831 in a Jewish family and he was studying to be a rabbi when someone gave him a copy of the New Testament in Hebrew. He studied it and he became convinced that Jesus was indeed the promised Messiah. He went to Germany to study further and after three years he came on to the United States where he was baptized in a Baptist congregation and then went for some reason to a Presbyterian seminary in Pittsburgh to study for the ministry. But after two years there they told him, “You can’t be ordained because you’re Jewish.” So he moved on to New York and found the Episcopal seminary which accepted him without a problem. So he graduated and was ordained and volunteered to go as a missionary to China where eventually they made hm a bishop. He founded a university and began translating the Bible into Chinese but after twelve years he had a stroke that left him confined to a wheel chair. So he moved to Japan and he spent the rest of his life translating the Bible into a basic Chinese dialect using a special typewriter and pressing the keys with one finger of his partly paralyzed right hand.

Bishop Schereschewsky died in 1906, and toward the end of his life he told a visitor: “I have sat in this chair for over twenty years. It seemed very hard at first. But God knew best. He kept me for the work for which I am best fitted.” God did not give him a weta. Nor did God give him a stroke. But God gave him great gifts as a linguist and translator and the perseverance to use those gifts.

If you know how to give your children good gifts, how much more will your heavenly Father. So pray for the gifts God is wise enough to give and pray for the wisdom to use them well.

July 5, 2019

What about borders?

A sermon preached at All Saints Church, San Francisco, on July 7, 2019, by Pastoral Associate Christopher L. Webber.

I woke up last Sunday to pictures of the President stepping across a raised line in Korea and I’ve been trying all week to understand why the same man would want to ignore a border in Korea and build one up in Texas. I’ve been wondering whether today’s Old Testament reading can help us understand. It’s all about borders: the walls we build and the walls we tear down.

Naaman was a Syrian: commander of the armies of Aram Aram or Syria – same thing – a major power in those days stretching from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates It took in modern Syria and most of Iraq. Some borders mattered to Naaman and some didn’t. He ignored borders when he wanted to plunder his Hebrew neighbors. He was raiding south of the border one day and captured a young Hebrew woman and brought her north as a slave to serve his wife. Borders couldn’t stand in the way of personal gain.

Naaman’s behavior is similar, I think, to the way American corporations have plundered Central America for generations, exploited resources, overthrown governments, enriched a few and  impoverished many. The American novelist, O Henry, invented the term “Banana Republic” to describe the governments created by the United Fruit Company and others to enrich American investors and impoverish Hondurans and Guatemalans. Borders don’t matter when we’re looking for plunder.

impoverished many. The American novelist, O Henry, invented the term “Banana Republic” to describe the governments created by the United Fruit Company and others to enrich American investors and impoverish Hondurans and Guatemalans. Borders don’t matter when we’re looking for plunder.

Israel had been a plunderer in the time of David and Solomon but now Israel was the plunderee, now it was a banana republic, ravaged by Egypt to the south and Syria to the north. Naaman would have understood our politics today. You might bring a few Central Americans north as servants and to work in the fields, you would certainly plunder the wealth, but you would build walls to keep most of the people you impoverished from coming north themselves. You build borders to protect yourself from that.

But the situation was complicated because Naaman was a leper. Well, it looked like leprosy. They couldn’t much tell different skin diseases apart in those days, but it looked like leprosy and that was scary. Leprosy ate away at your body and slowly destroyed you, and it was contagious so you exiled lepers, you made them stay outside the towns and cities, wander the countryside, but not get close. Lepers had to stay outside an invisible border ringing a bell to warn you and calling out “Unclean, unclean.”

But Naaman was the commanding general of the Syrian armies, so he wouldn’t be exiled quickly, but if that patch on his arm began to spread and he couldn’t hide it that was the end: no more palace, no more servants, no more luxuries, but a slow, painful, miserable death away from everything he valued and everything he cared about. But the Hebrew servant girl knew something, and she told Naaman’s wife and Naaman’s wife told him. The servant girl said, “There’s a prophet in Israel who does healings. Some say he even raised the dead. Maybe he can solve your problem.” So Naaman told the king and the king gave consent and Naaman headed south with a small army of servants and soldiers and went straight to the king’s palace in Israel.

The king of Israel at the time was probably King Jehoram, son of Ahaz, but this minor king was so unimportant we’re never told his name. So Naaman showed up at the door with a small army and said, “Cure my leprosy.” Well, the maid never said the king could do it, but Naaman just started at the top and scared Jehoram to death. “Me cure leprosy? Is he looking for another war?” But they got things straightened out and General Naaman went to see Elisha. And Elisha couldn’t be bothered even to go to the door. “Leprosy? No problem. Tell him to go wash in the Jordan and he’ll be fine.”

But Naaman was outraged. “Wash in the Jordan? That muddy creek?” We’ve got better rivers in Syria. Well, they did. Yjey had the Euphrates. He could have washed in the mighty Euphrates. Why bother to come all the way down south to wash in some muddy brook in Israel? Naaman flew into a rage and it took a while for his servants to calm him down. “Look,” they said, “if he’d asked you to do a hundred pushups or wash all over with Chanel #5 – wouldn’t you have done it? So why not the simple thing? What’s to lose?” So, grudgingly, he did. And it worked. And he was thrilled And that’s the end of today’s reading. It’s supposed to parallel or connect with the Gospel reading about Jesus sending the disciples out on a healing mission, but I’d rather make the connection to the headlines and borders.

So let me just finish off the story that the reading left hanging, unfinished. Here’s what we didn’t hear. Naaman was thrilled. He went back to Elisha and offered to pay him. But Elisha waved him off. “No problem. Go on home. Don’t worry. Forget about it.” So then – here’s the part I like – Naaman said, “Well, OK, but at least let me take back to Syria two mule loads of earth.”

Why? What’s that about? Naaman wants the dirt because now he knows there’s a God in Israel who answers prayer and he wants a chunk of Israel to stand on from now on when he prays so the God of Israel will hear him.

Do you see what’s happening? We’re at a stage of human development, religious development, when different people had different gods and the gods were connected with certain areas, certain lands. When in Israel, pray to Jehovah. When in Syria, pray to Baal. Gods have borders too. But Baal didn’t help my leprosy and Yahweh did. So if I have to go back to Syria maybe I can take some of Israel with me and stand on it when I pray and this powerful Israelite God will still hear my prayers

Here’s the point: this is a story of events that took place almost 3000 years ago and they were at a very early stage in the story of the human understanding of God. Move down a few centuries and you find Isaiah, another prophet for another time, and Isaiah knew something Naaman didn’t know and maybe Elishah didn’t either. Isaiah knew that God is a God who rules all nations. Isaiah knew that God could  take King Cyrus of Babylon and use him as a tool in God’s hand. Isaiah knew that the God of Israel is the only God and there is no other. Isaiah knew that from the rising of the sun to it’s setting there is no other God. “I am the Lord,”“ says the God of Isaiah, “and there is no other.”

take King Cyrus of Babylon and use him as a tool in God’s hand. Isaiah knew that the God of Israel is the only God and there is no other. Isaiah knew that from the rising of the sun to it’s setting there is no other God. “I am the Lord,”“ says the God of Isaiah, “and there is no other.”

Think again about borders. We have a president who can step across one border and build walls on another. But what’s the big picture here? Where is God in all this? What does God care about borders? Here we are on the weekend celebrating American Independence and I learned something about that last week that I hadn’t known before. We have a prayer in the Prayer Book for Independence Day and we have assigned readings from the Bible, and I thought we always had. But No. No, the committee that created the first American Prayer Book in 1789 wrote a prayer for Independence Day and chose readings from the Bible, but the Bishop of Pennsylvania said, “Wait a minute. A lot of the clergy were not on board with this business. They had been loyal to their ordination oath to the King of England and some have gone back to England and some to Canada and we don’t want to embarrass the ones who remain by making them give thanks for something they aren’t thankful for.” So there was no prayer for Independence Day in the Episcopal Prayer Book until 1928 when most people had gotten over it. So in 1928 they put back the readings that are more relevant today than ever. They called on Episcopalians down to our own day to read these verses: Deuteronomy 10:17-21:

“The Lord your God is God of gods and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty and awesome, who is not partial and takes no bribe, who executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and who loves the strangers, providing them food and clothing. You shall also love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”If that’s not clear enough, there’s a newer translation, almost ten year s old, but more relevant than ever, that puts it this way: “The Lord your God is the God of all gods and the Lord of all lords . . . He enacts justice for orphans and widows, and he loves immigrants giving them food and clothing. That means that you must also love immigrants because you were immigrants in Egypt.” (Common English Bible)

s old, but more relevant than ever, that puts it this way: “The Lord your God is the God of all gods and the Lord of all lords . . . He enacts justice for orphans and widows, and he loves immigrants giving them food and clothing. That means that you must also love immigrants because you were immigrants in Egypt.” (Common English Bible)

Argue the politics however you want and do what you want about walls and borders but our instructions

are clear. I took a certain pride in the presence of the one openly Episcopalian candidate on stage lastweek and the fact that he alone acknowledged that Christians are under orders. He said: “we should call out hypocrisy when we see it. . . a party that associates itself with Christianity . . . (and) suggests that. . . God would condone putting children in cages has lost all claim to ever use religious language again.”

And, yes, is it really so good a thing that there’s another set of borders in the world, another division between human beings? Is it a good thing that Korea is divided North and South? Is it a good thing that North America is divided three ways? Is it a good thing that Central American terrorists can control tiny countries and that we respect their right to rape and pillage as they like because, hey, there’s a border we have to respect?

What is it about borders? How is it that capitalists can ravage tiny countries with no one to hinder them, but when their victims flee for their lives we turn them away? What’s wrong with this picture? The wall is not the whole picture. The picture includes small countries destroyed by our corporations, but we’re not responsible and I don’t understand why.

Now I’m a priest, not a politician. I get to ask questions, not give answers. Except this: our God is the God of Isaiah, who knows no borders. Except this: we have a vision given us and a mandate to fulfill and the same God who loves us and calls us will also be our judge.

We will end the service today with the singing of that great hymn, “America the beautiful,” that puts into words and music something of what I’ve been trying to say:

“O beautiful for patriot dream

that sees beyond the years

thine alabaster cities gleam

undimmed by human tears . . .”

Few things, I think, cause more tears than borders, but we are given a vision that sees beyond the politics, beyond the borders, beyond the years; a vision that calls us and questions us: Must it indeed be always “beyond the years”?

Why not in our own day?

Why not now?

June 30, 2019

A Homily for Independence Day 2019

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber, Pastoral Associate, at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, on July 2, 2019.

It never before occurred to me to wonder why we celebrate the 4th of July in Church until this year. This year it happened to be my turn to do the service today and I did the research. I had assumed that of course Americans would celebrate the 4th of July in church – well, at least some church-going Christians would do that – because freedom is a gift of God and our existence as a nation is a gift of God so of course there would be readings and a prayer assigned for the occasion.

But what I learned is: it’s not that obvious. When they sat down to create a Prayer Book for the newly independent Episcopal Church – no longer a part of the church of England but an independent church within the Anglican Communion – they included a form of service to celebrate what they called: “the inestimable blessings of Religious and Civil Liberty to be observed by this church for ever.” Of course. Obvious. Who would question?

Well, one who questioned was William White, the first bishop of Pennsylvania, who pointed out that the great majority of American clergy had not supported the Revolution – indeed had opposed it – and many had fled to Canada rather than work or pray for independence. Those who remained, White pointed out, were not likely to use such a service, celebrating what they had opposed, and would be greatly embarrassed if they did. White himself had supported independence, had served as a chaplain to the Congress, but he was concerned for his colleagues who had seen things differently. The war was over, White thought; let’s not embarrass each other. So the General Convention took the form out of the Prayer Book and it was only added in 1928 when the one-time loyalists had presumably all gone to their reward.

So it’s been there all my life time – and probably yours unless you’re over 91 – but we shouldn’t take it for granted. It took a while, but here we are, and here we ought to be because freedom is a gift of God and we have great cause to be thankful.

But look what they gave us when they finally got up their nerve: not just an appropriate form of thanksgiving for events well over 200 years ago but words to challenge us as if they had been especially chosen for current events, words to remind us of what it means to be a nation blessed with great gifts. The gift of freedom is a gift of God and it comes with an obligation. Listen again to the words we read this morning from the Old Testament:

“The Lord your God …. executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and . . . loves the strangers, providing them food and clothing. You shall also love the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

If that’s not clear enough, I would refer you to the newest translation I know of, the Common English Bible, published under ecumenical auspices less than ten years ago, which puts it this way:

“He enacts justice for orphans and widows, and he loves immigrants giving them food and clothing. That means you also must love immigrants, for you were immigrants in the land of Egypt.”

Yes. “You must love immigrants.” “You yourselves were immigrants.” What part of that is not clear?

Now those words, of course, were written to Jewish people living in Canaan centuries after their ancestors had escaped from Egypt. I would guess most of us – most of our families – have not been around that many centuries. Three of my grandparents were immigrants. I know how my parents grew up as first generation Americans, first of their families to go to college and, in my father’s case, only after dropping out of school to help support the family and being enabled to go back to finish high school and college and seminary by a wealthy neighbor who took an interest and an older sister who had dropped out of school after 8th Grade to help support the family. This is a country where such things are possible. No wonder it continues to draw others.

No wonder also that we have an obligation to share the gifts we’ve been given. “. . . he loves immigrants giving them food and clothing. That means you also must love immigrants . . .”

But what instead do we see? You’ve seen the pictures. I don’t need to tell you.

I was delighted in watching the debates last week to hear the one Episcopalian in the debate say this: “We are committed to the separation of church and state and we stand for people of any religion and people of no religion. But we should call out hypocrisy when we see it in a party that associates itself with Christianity to say that it is okay to suggest that God would smile on the division of families at the hands of federal agents, [to say] that God would condone putting children in cages has lost all claim to ever use religious language again.”

Yes. Absolutely. The Bible lays a claim on our lives, lays a claim on our actions. We  as Americans, as American Christians, are under obligation, under orders and we will sing about it before we leave:

as Americans, as American Christians, are under obligation, under orders and we will sing about it before we leave:

“O beautiful for patriot dream that sees beyond the years

thine alabaster cities gleam undimmed by human tears . . .”

But must it be indeed always “beyond the years”?

Why not in our own day?

Why not now?

June 11, 2019

Free Advice for Harvard

I received a brochure today from Harvard University offering gift strategies by which I can enrich Harvard – as if I could make a difference anyhow in the zillions they have salted away! I was interested, however, in the high-lighted words on the cover from a 1948 graduate: “I felt like I had graduated from an institution that now truly reflects American society.” Yes: if improper English “truly reflects American society,” that phrase does it. If you go on line, you will find the following:

“The word like should never be used before a clause.

Example 1 (incorrect usage): It looks like it will rain.

“Like should be used before a noun only, as in the following example:

Example 2 (correct usage): The girl looks like her mother.

“Take a close look at the two sentences above. Do you see the difference in how they are used? In the first sentence, like is followed by the clause it will rain. In the second sentence, like is followed by her mother. Whenever a subject and verb follow, remember to substitute like with either as though or as if, as illustrated in the final example below.

Example 3 (correct): It looks as if it will rain.”

Free advice for the folks at Harvard Planned Giving: check with a Princeton graduate to make sure your English usage is proper before asking them to contribute!

June 10, 2019

A Good Man

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber on June 11, St. Barnabbas Day, 2019, at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco.

Many years ago, I was called on to preach at an ordination on the 11th day of June – St Barnabas Day – and we read the same lesson from the book of Acts that we read this morning and I remember making a point in that sermon about the fact that Barnabas is described as “a good man.” That phrase, “a good man,” is used of no other individual in the whole Bible, not even Jesus.

What does it mean to call someone a good man or a good woman or a good person? Is it really that rare? I think we use the phrase ourselves more often than the Bible, don’t we? Don’t we say: “he’s a good man” or “she’s a good woman” fairly often? I hope we do because it would be hard to live somewhere where we never had occasion to say it.

I would imagine we depend on a certain general level of goodness just to get through the day. When tragedy strikes we’re often amazed at the way people rally around and go way out of their way to be helpful, to pitch in, to share, to go beyond what we might have expected because whatever the evangelicals may say about how we’re all sinners and need to repent – and I don’t disagree – I think it’s more important to recognize that there’s a fundamental goodness in human beings because, after all, we were made in the image of God and, yes, Eve offered an apple or banana or whatever it was and Adam ate it but she still probably cooked his meals and he probably still brought in the harvest and they still probably took time to play with the children and after the one boy killed the other and went off into exile they picked themselves up and started again.

There was a fundamental goodness in Adam and Eve because they were made in the image of God. We all are. It’s the exception who is known best as a liar or a bully. All of us of a certain age remember the lawyer, Joseph Welch, saying to Joseph McCarthy: “At long last, have you left no sense of decency? Have you at last no decency.” Just decency. We have to expect some basic level of goodness and decency in our fellow human beings just to get through the day and have to be saddened when we realize it’s not there, that someone in the public eye or someone in our own acquaintance has failed, has been corrupted, has yielded to temptation and no longer seems to have that basic goodness we depend on to get through the day.

Barnabas was a good man. Well, there lots of good people in the Bible but only Barnabbas gets the adjective, So he was special. I think the Bible is telling us he stood out – was “gooder” than most. But as we read on in the story what we hear is pretty basic stuff. You need to be able to count on people just for ordinary things like contributing financially. Barnabbas might be the patron saint of the every member canvass. Early on, in chapter 4 of Acts, we hear that he sold some property he had and gave the proceeds to the apostles. That qualifies as a good man; we need more of them.

But then Barnabbas also brought in a new member and we surely need people like that. It was Barnabbas who brought Paul to church with him. Paul had been converted on the Damascus Road but when he showed up in Jerusalem nobody trusted him. I mean, why would you? This man had been  trying to destroy the church and now he wants us to take him in? I don’t think so. But Barnabbas took the chance and brought him along – and we all know what a difference Paul made.

trying to destroy the church and now he wants us to take him in? I don’t think so. But Barnabbas took the chance and brought him along – and we all know what a difference Paul made.

But not right away. The church in Jerusalem was still suspicious and Paul finally went home to Tarsus apparently feeling unwanted. But Barnabbas remembered him. Time went by and the church in Jerusalem heard that the church was growing in Antioch and they sent Barnabbas to help out but when Barnabbas got there and saw what was happening he saw there was work enough for two and he remembered Paul and went to Tarsus to find him and get him to help. And that’s how it all began.

Still later things were going badly in Jerusalem. There was a famine and people were starving so the new church in Antioch sent Barnabbas and Paul with some badly needed funds. And still later when they decided they should share the word with still other cities they chose Paul and Barnabbas to go off on the first formal missionary road trip and one place they went – I think this is really interesting about Barnabbas – they came to a place called Lystra and the people were so impressed with Paul and Barnabbas they decided Paul and Barnabbas were gods and they called Paul “Mercury” because he was the chief speaker and Barnabbas they called “Jupiter” – the chief god in the Greek mythology. That’s the impression Barnabbas made even without speaking: people said, he must be god.

So Barnabbas was a good man: he did it by chipping in and pitching in and recognizing the gifts of others and trusting when others were doubtful. Without Barnabbas we might not have had Paul and without Paul what would have happened to the Christian church? But it’s all summed up in one word: “he was a good man.” We need more of them.

May 21, 2019

Walls and Gates

A sermon by Christopher L. Webber for the 6th Sunday of Easter – May 26, 2019

In the spirit the angel carried me away to a great, high mountain and showed me the holy city Jerusalem coming down out of heaven from God.

I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb. And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it. Its gates will never be shut by day– and there will be no night there. People will bring into it the glory and the honor of the nations. Revelation 21:22-27

Here’s the tragedy: millions of Christians will go to church this morning but not all of them will hear the description we just heard of the city of God. Roman Catholics will hear it, and Lutherans and Presbyterians and Methodists and Episcopalians, but you know who won’t hear it: most evangelical Christians, because those churches follow no set lectionary and the pastor can choose what he wants to preach about. So most evangelicals won’t hear today about the promised city of God which may have walls but also has gates that are never shut.

We Americans need to think about that: heaven is like a city with gates that are never shut, never closed at all day or night. The divisions within our society seem constantly to grow worse and it doesn’t help at all that we hear different parts of the Bible on Sunday morning. Imagine what a difference it could make if we all began the week from the same place with the same words of scripture in our minds and hearts. Imagine what a difference it would make if we all began this week with the same vision: God’s city, God’s city, where the gates are never closed.

You could point out, of course, that the city of God described in the Bible does have walls. Yes, it does, but that’s because an ancient city was defined by walls. If a community has walls, it’s a city. If it doesn’t, it isn’t. But in the heavenly city, the gates are never closed. That’s what makes the difference.

There was a time in the progress of humanity when people began coming together to build a more complex community. They had learned how to grow grain – rice or wheat or barley or quinoa and grain was a food that could be stored and that meant that you could settle down and live in one place. You could have a house instead of a cave. You could be a farmer instead of a hunter-gatherer. You could develop a community and you could put up walls to protect yourself against wild animals and wild people. You could live inside the walls and be safe and go out to work in your fields and bring your harvest into the city to store it safely. Outside the city walls there might be other smaller communities, but they also relied on the city walls for safety. A city was a community with walls. A village was a community without walls, but near enough to the city to fly there for refuge in times of trouble.

Maybe you’ve visited England or France or other European countries and seen the remnants of the walls that once protected them but are no longer needed. I think there’s only one city left in England that has a complete wall still standing, and that’s the city of Cheshire on the border with Wales. I spent some time in that area years ago and I took time one day to walk around that wall. These days there’s as much city outside the wall as inside because they’ve outgrown the need for city walls. In most places around the world human beings have outgrown the need for border walls as well. The Great Wall of China is for  tourists to climb on. Even the Berlin wall finally had to come down. The idea of a wall on our southern border is out of date and absurd. Most illegal immigrants don’t come across the Mexican border anyway; they come by plane and overstay their visas. And they will continue to come as long as there are jobs Americans don’t want. They will continue to come to do not just the stoop labor of picking strawberries in the central valley emptying bed pans in our nursing homes and waiting on table in retirement communities. I’ve met people where I live from the Philippines and Bosnia and Uruguay and Uzbekistan and the Ukraine. And they don’t necessarily want to be here. Many of them have families back home that depend on them and they go back whenever they can – if they can. This country does have walls, but they’re economic walls. There are millions who would come here if they could, millions who are here who would rather be elsewhere.

tourists to climb on. Even the Berlin wall finally had to come down. The idea of a wall on our southern border is out of date and absurd. Most illegal immigrants don’t come across the Mexican border anyway; they come by plane and overstay their visas. And they will continue to come as long as there are jobs Americans don’t want. They will continue to come to do not just the stoop labor of picking strawberries in the central valley emptying bed pans in our nursing homes and waiting on table in retirement communities. I’ve met people where I live from the Philippines and Bosnia and Uruguay and Uzbekistan and the Ukraine. And they don’t necessarily want to be here. Many of them have families back home that depend on them and they go back whenever they can – if they can. This country does have walls, but they’re economic walls. There are millions who would come here if they could, millions who are here who would rather be elsewhere.

Trump ponders the wall

There are millions of Americans, by the way, who live elsewhere by choice – in Mexico and Panama and Portugal – because its cheaper and warmer there than here. People who can afford to live elsewhere are happy to leave America. So we can build a wall on the Mexican border or not and it won’t make much difference. What will make a difference is the kind of community we build here, here where we are. Walls don’t matter; they keep them in Chester as a tourist attraction and someday whatever we build between us and Mexico may have that value also, but what matters is what happens inside the walls – in the city – don’t miss what the Bible says about that: “People will bring into it the glory and the honor of the nations. But nothing unclean will enter it, nor anyone who practices abomination or falsehood.” No one who practices falsehood will be in God’s city, no one who tells lies will be there. God’s city is a place where people tell the truth and they bring into that community all that is good – the glory and honor of the nations. Nothing unclean will enter it. In God’s city no one will sleep on the sidewalk or under bridges. Forget about the borders, what matters is what happens inside.

In God’s city the walls are a tourist attraction but there’s no darkness there, nothing false, nothing unclean, San Francisco is not like that. I hope for the day that I can walk up 19th avenue from the N-Judah and see no litter, no trash on the sidewalk. I may be wrong, but I think it comes from the young men and women who I see standing on those sidewalks at 8 and 8:30 every weekday morning waiting for the giant bus to come and scoop them up and take them to Silicon Valley. I don’t see trash on the other side of the avenue so I think it’s these young Americans with jobs no Mexican immigrant could hope for who trash the sidewalks that others sleep on. Wouldn’t you think that we who live here because of choices our grandparents or great grandparents made could do better at preserving the dream?

We’re given a vision. How do we share it? How do we tell our friends and neighbors it doesn’t have to be this way? God gives us a vision of a new community. The verses we read this morning come from the next to last chapter of the Bible: This where we are going. This is the vision God gives us, not just to dream about but to work for and to share. A few verses earlier the vision began this way – I wish we’d had a longer reading but I’ll read it anyway:

Revelation 21:1 Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. 2 And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. 3 And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; 4 he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away.” 5 And the one who was seated on the throne said, “See, I am making all things new.” Also he said, “Write this, for these words are trustworthy and true.”

Notice this one thing: this new city is not somewhere else, not in a distant heaven, but here. We don’t go up to it; it comes down to us. And I believe it’s up to us to prepare the way: to hold in our minds and hearts the vision of the city of God and not settle for anything less.