Christopher L. Webber's Blog, page 9

July 3, 2016

Fear and Freedom: Thoughts for the 4th of July

A sermon preached at All Saints Church, San Francisco, on July 3, 2016, by Christopher L. Webber.

It’s Fourth of July weekend and I, as a preacher by trade, instinctively want to put that day in a theological context, so I wonder whether we could raise our eyes for a few minutes this morning from the heat of American politics – the heat and the horror of American politics – and remember the vision, remember that there is a vision, and it’s a vision of hope, not fear.

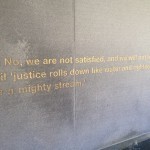

I’m afraid – my fear is – that for all too many the basic question is not the one we should be asking: “What is the vision,” but “What are you afraid of?” Too many of us, I think, are governed this year by our fears, not our hopes. And there are all too many politicians along the whole political spectrum who are ready to pander to those fears, to stir up fears, even to create fears. To tell us, “Be afraid, be very afraid; elect me because if I am not elected you will be less safe; your job will be sent over seas, immigrants will move into your neighborhood, you will be shot down by terrorists, the price of gas will get back out of control, the price of soft drinks may go up; they will cut your social security, defund your medicare, make you share your bathroom. I wonder if a nation so powerful has ever been populated by such fearful people. We have forgotten how at another critical turning point in our history we were told that “the only thing we have to fear is – fear itself. Nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror that paralyzes needed effort to turn retreat into advance.” That is as true today as it was when Franklin Roosevelt said it over 80 years ago.

I was no great admirer of Ronald Reagan but he did have a way sometimes at least of calling us back to a vision a vision of a shining city on a hill, of hope, not fear. An appeal not to make America great again as if the best days were in the past but to remember the vision, to look ahead in hope, not behind in fear. The first settlers in Massachusetts Bay – illegal immigrants, we should remember – the first settlers in Massachusetts Bay were given a vision of a city on a hill. And if we are such a  city, as they foresaw, we will inevitably draw other people here as your ancestors and mine were drawn here by a vision, often, yes, a very selfish and practical vision of a good job, opportunities for my children, the right to practice my religion without fear, to believe or not believe whatever I want. Sometimes it’s ben a pretty narrow and self-centered vision, but it’s a vision nonetheless, a vision about hope, not a vision about fear.

city, as they foresaw, we will inevitably draw other people here as your ancestors and mine were drawn here by a vision, often, yes, a very selfish and practical vision of a good job, opportunities for my children, the right to practice my religion without fear, to believe or not believe whatever I want. Sometimes it’s ben a pretty narrow and self-centered vision, but it’s a vision nonetheless, a vision about hope, not a vision about fear.

I read a very interesting book some years ago about Russia and the factors that have shaped its history and its relationship with the world. The author made the point that after World War I as Russia descended into chaos the western powers attempted to intervene to prevent the communist faction from taking control. The communists therefore moved back – away from the modern, western capital city of St Petersburg, which had always prided itself on its European culture, its art, its music, its openness to the west and they set up shop instead in the deep interior city of Moscow cut off from the west, suspicious of the west, fearful of the west. You might imagine what would happen if we moved the capital of the United States from Washington to Wichita or Dallas. So the result of western attempts to shape Russian history was the creation of a fearful power, paranoid about the west. Marx at least had a vision; Stalin and his coterie only had fears. For a brief moment Gorbachev tried to change all that, but he failed and Russia lapsed back into paranoia and fear.

It seems to me that it’s bad enough to have Russia dominated by fear but far worse if we move in that same direction ourselves. But isn’t that what’s happening as our political process is controlled more and more by fearful people who talk about building walls rather than opening doors?

It’s 4th of July weekend and it’s a natural time to think about ourselves as American Christians or Christian Americans and ask ourselves what that means and whether we have a vision and if so whether that vision has any relationship with our faith. Too often it seems as if the only people who even ask that question are people who put America first and faith second, whose nationalism is deepened by their faith rather than redeemed by it.

Now, the first reading today gives us one way to think about faith and nation. It’s a really funny story set many centuries before Christ at a time when the Jews were attempting to hang on to some shreds of the glory that David and Solomon had won. They were constantly harassed by other petty kingdoms especially to the north and more powerful kingdoms lurking further afield in Egypt and Babylon. And they were weakened by their own division into two tiny Hebrew kingdoms, Israel to the North and Judah to the south, that spent a lot of time fighting each other. North of Israel was Aram which included a good deal of what we now call Syria. That sets the stage for the story we just read.

Naaman was commander of the armies of Aram, but he had leprosy – or some sort of skin disease – and an Israeli slave girl he had captured told him that there was a prophet in Israel, Elijah, who could cure him. So Naaman told the king and the king said, “Well, go down and get cured, and I’ll give you some stuff to give the prophet to pay him for his cure.” So Naaman went and – to make a long story short – he got to Elisha’s house and Elisha sent a servant out to tell Naaman what to do: “Go wash in the Jordan River and you’ll be cured” Well, that set Naaman off – imagine if you went to the doctor’s office with cancer and the doctor didn’t even see you, just sent a nurse out with some pills.

Naaman was upset already because he had to come ask help from someone in a nation his armies had beaten and the prophet wouldn’t even give him face time. To make it worse the servant told him to go wash in the waters of the Jordan, a muddy little Israelite river. So Naaman went off in a huff saying, “What’s so special about the Jordan? “Don’t we have better rivers in Aram?” But his servant said, “Wait a minute. Look, if he asked you to do some big thing, you would have done it, so why not this little thing? What have you got to lose?” So Naaman did it – grumbling all the way – and was cured.

What we didn’t get to read today is the best part of the story. We didn’t hear how Naaman tried to heap gifts on Elisha and how he took bushels of Israeli soil back with him so he could stand on Israeli dirt when he prayed. It seemed to Naaman that there were gods for Aram and gods of Israel and the God of Israel was obviously powerful so Naaman thought he’d like to stay in touch with this Israelite God so he would bring some of the Israelite dirt back with him to Aram so he could stand on it when he prayed to Israel’s god.

Now I hope we’ve come a way since then. When I moved here three years ago I would have liked to bring a bushel of Connecticut topsoil with me, but for gardening, not for prayer. I hope none of us would feel a need to take a chunk of California with us if we worked for a company that sent us off to work in Russia or China.  Our God is not an American God. I think we know that. God is not limited to America, we know that. The Creator of the universe can hear prayers from every imagined corner of this round earth, and we know that. And God is listening to prayers offered in Russian and Chinese and a thousand other languages as well as ours, and American prayers – we ought to know this – have no preferential treatment in the halls of heaven.

Our God is not an American God. I think we know that. God is not limited to America, we know that. The Creator of the universe can hear prayers from every imagined corner of this round earth, and we know that. And God is listening to prayers offered in Russian and Chinese and a thousand other languages as well as ours, and American prayers – we ought to know this – have no preferential treatment in the halls of heaven.

There’s a very early Christian document called The Epistle to Diognetus and that letter puts such ideas in perspective: “Christians,” it says, “live in both Greek and barbarian cities, as each one’s lot was cast, and follow the local customs in dress and food and other aspects of life, at the same time they demonstrate the remarkable and admittedly unusual character of their own citizenship. They live in their own countries, but only as aliens; they participate in everything as citizens, and endure everything as foreigners. Every foreign country is their fatherland, and every fatherland is for them a foreign land. They live on earth, but their citizenship is in heaven.”

Now that puts things in perspective. Do we think of ourselves as living here as foreigners, as aliens, possibly as illegal immigrants? Does it ever occur to us to think of ourselves as citizens first of heaven and only secondly as Americans? But isn’t that exactly the perspective we need in thinking about this year’s elections? It seems to me that the way this year’s election is shaping up that perspective could be very useful. That perspective could be really useful in compelling us to clarify if only for ourselves who we are as American Christians and what vision we have for our world.

I hear people asking, “Is this really what America is all about?” We need to have answers for that question. What seems to be coming clear is that this year’s elections are not more of the same, the “same old same old.” In other years we have tended to edge one way or another but never change course entirely. It’s been 150 years since we made a radical choice. I wonder whether those who went to the polls in 1860 to choose among Stephen A Douglas, John Breckinridge, Abraham Lincoln, and  John Bell fully realized the consequences of their choice. For almost a hundred years elections had come and gone. Federalists had won, sometimes; Democrats had won sometimes; Whigs had won sometimes. Candidates and even parties had come and gone, but the country had survived and even prospered. But 1860 was different. We moved in four years from being a loose federation of agricultural states to being a centrally governed industrial nation. Fewer than two million voters, less than 40% of the electorate changed America forever.

John Bell fully realized the consequences of their choice. For almost a hundred years elections had come and gone. Federalists had won, sometimes; Democrats had won sometimes; Whigs had won sometimes. Candidates and even parties had come and gone, but the country had survived and even prospered. But 1860 was different. We moved in four years from being a loose federation of agricultural states to being a centrally governed industrial nation. Fewer than two million voters, less than 40% of the electorate changed America forever.

The question being asked is whether 2016 is also different, if our politics is changing in fundamental ways, if there is still enough in common, to hold us together. I wonder what the consequences of our choices this year will be for next year and beyond. Does anyone, for that matter, know what the consequences of Brexit will be and whether Europe, too, is changing in fundamental ways. I think most of us assumed that England would do the sensible thing and be a united kingdom in a united Europe, but we were wrong. I think whatever the incredible aspects of this year’s election are, we still assume that sensible people will prevail and nothing really radical will happen. But is there anything in human history that would lead us to believe that? Does the crucifixion tell us that sensible people ultimately prevail? I think not. I think we’ve taken it for granted that at least in the west we’ve outgrown the horrors of war, that we’ve been on a path toward deeper unity. But maybe not; maybe we can’t take it for granted anymore that Europe will not revert to anarchy, that we can finally slowly overcome our divisions, that the arc of history is moving toward unity. Perhaps not; perhaps the sin of pride and self is as deeply rooted as the Bible tells us; perhaps faith does make a difference, and we need to be very clear about what the difference is and look with a new urgency at the differences among Christians that prevent us from holding up a standard and a vision.

One thing we should know is that the world does change, that choices make a difference. So surely Americans who call themselves Christians need to ask what it means to have a deeper loyalty than a narrow nationalism and a faith that overcomes fear. The Gospel today tells us how Jesus sent his disciples out to proclaim the kingdom of God. To be politically correct, we might prefer to say, “The realm of God.” But after 50 years of Queen Elizabeth everyone still talks about the United Kingdom – or did until a week ago. But one way or another, the gospel suggests a summons to a fundamental allegiance to a power not of this world; it’s a summon to take hold of a different standard, to judge our common life not by the Constitution or the Bill of Rights or the latest rulings of the Supreme Court or actions of Congress – if that isn’t an oxymoron. It’s not political statements we need, but kingdom righteousness, realm righteousness, basic Biblical standards: Love God. Love your neighbor as yourself. Reach out to the wounded stranger lying beside the road, the one even respectable people have no time for. Care for the stranger in your midst.

Re-reading the Book of Numbers recently, the fourth book of the Bible, I came across the commandment that, “there shall be both for you and the resident alien a single statute . . . you and the alien who resides among you shall have the same law.” The prophet Malachi, in the last book of the Old Testament asked, “Have we not all one Father? Has not one God created us?”

Christians are people who know, or should know, that “Love is patient, love is kind. . . (love) does not dishonor others, is not self-seeking, is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. . . It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.” Can we bear some of that in mind in making choices this year, in talking with others about the election, in thinking through what we are called to stand for, what it means to be a Christian – for whom every father land is a foreign land – who are not surprised when their fellow citizens opt for values that seem far from the kingdom of God?

Notice finally one other thing: In the Gospel today, when Jesus sent the disciples out to proclaim a  new world, God’s realm, God’s kingdom, he told them to seek for peace and where no peace existed to wipe the dust of that place from their feet. Naaman would have understood. Don’t stand on ground alienated from God, in a land that has turned away from peace. Shake it off and move on. Set your feet on the solid rock of faith in the city on a hill. Be a shining light of faith in a world of doubt and fear.

new world, God’s realm, God’s kingdom, he told them to seek for peace and where no peace existed to wipe the dust of that place from their feet. Naaman would have understood. Don’t stand on ground alienated from God, in a land that has turned away from peace. Shake it off and move on. Set your feet on the solid rock of faith in the city on a hill. Be a shining light of faith in a world of doubt and fear.

May 29, 2016

Freedom From/Freedom For: Making Choices Today

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, on May 29, 2016.

Last year as some of you know I wrote a book called “Dear Friends.” It’s a re-write of St Paul’s Epistles, imagining that he was writing today to churches in Washington DC and California and Florida and Texas. I had the most fun  writing the one to Texas, probably because Texas is the only state in which I have never set foot, not even landed briefly in an airport.

writing the one to Texas, probably because Texas is the only state in which I have never set foot, not even landed briefly in an airport.

It’s always easier to write about something when you don’t know anything about it. But I do know some things and one of them is that Texas has come to symbolize a certain attitude that may be uniquely American – and yet not uniquely American because we find St Paul inveighing against it in a letter he wrote to some congregations of Christians in Asia almost two thousand years ago.

The Galatians he wrote to were probably Celtic tribes living just north of territories fought over today by various sects of Syrians and Kurds and others: Christians and Muslims, Shiite and Sunni, and some of the issues are not really that different from issues we face today whether we face them in Syria or Texas or the Sunset district of San Francisco. They are issues, or attitudes, that will shape our upcoming presidential election. It’s about freedom and law, It’s about law and freedom.

Paul could get angry at times and we see him at his angriest in this letter to the Galatians and we will be working through it the next five weeks when we read the epistle. There are six chapters in the epistle; and we have six weeks to read it. We have a lifetime to learn to live by it. But the essence of it is simple, a stark choice, the same choice we face in this year’s election: to live by law or to live in freedom, to be subject to law or to be free.

Paul barely gets into it this week, but keep it in mind from now til the fourth of July: law vs. freedom: How do we shape our lives: Is it by law or is it by freedom? It’s appropriate that we come to the end of this reading from Galatians on Fourth of July weekend when we celebrate American freedom. Maybe we can come to it this year with a clearer sense of what that freedom is. And it’s bigger than American independence. Freedom from England is all very well, but for what? Freedom for what? That’s what Paul wants the Galatians to think about. Freedom for what? Christ has set you free, so what does it mean to live as free people? Freedom FROM is all very well but what is freedom for?

What is freedom for? I think there’s no better way to answer that question than working carefully through this epistle and I don’t want to get ahead of the story. Sometime next month we will hear Paul say, “For freedom Christ has set us free.” It sounds as if freedom is an end in itself, but I don’t think so. I think it has a purpose. I think it’s a gift to use to shape all our relationships and to grow in love and worship.

But let me begin by trying to put it in context. Paul was writing to Galatians, a Celtic group in what we would now call central Turkey, an area impacted now by tens of thousands of refugees desperately seeking freedom: freedom from  killing and war, freedom from hunger and chaos, and freedom to be able to put down roots and find jobs and build families – things most of us take for granted – freedom for all of that. The lives of the Galatians, as far as we know, were a lot less chaotic than the lives of the people living there now. Then they had the stability provided by the Roman Empire, which gave them the freedom to live peacefully as long as they stayed within the rules and didn’t cause trouble. That’s a lot more than most people in that area have today. So when Paul wrote to the Galatians about freedom I don’t think political freedom was first in their minds. I mean, what chance do you have of gaining freedom when the armies of Rome are in control? And who wants political freedom as long as you have peace and security?

killing and war, freedom from hunger and chaos, and freedom to be able to put down roots and find jobs and build families – things most of us take for granted – freedom for all of that. The lives of the Galatians, as far as we know, were a lot less chaotic than the lives of the people living there now. Then they had the stability provided by the Roman Empire, which gave them the freedom to live peacefully as long as they stayed within the rules and didn’t cause trouble. That’s a lot more than most people in that area have today. So when Paul wrote to the Galatians about freedom I don’t think political freedom was first in their minds. I mean, what chance do you have of gaining freedom when the armies of Rome are in control? And who wants political freedom as long as you have peace and security?

Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote of the peace and security of the prisoners in the Gulag Archipelago, the forced labor camps in Siberia, where every day was the same and they had no decisions to make or choices to worry about. As prisoners, they were free from all the pressures of living in freedom. The Galatians had that kind of freedom thanks to the Roman Empire. But some of them were converts to Judaism and they had learned the value of law in their relationship with God. Judaism in their religious life provided them with a structure just as Rome did in their political life. Judaism gave them laws that enabled them to bring their lives into obedience to the living God. But Paul was talking about freedom from that legal structure and a way to build new lives of faith in freedom.

Over the next five weeks we will hear Paul telling them – and us – that the law was good to bring you to a knowledge of the living God, a relationship with the living God, but in Christ there’s no need of that structure, that system of law, the requirements of kosher and circumcision and keeping the Sabbath, because Christ has set you free. The great danger now is being drawn back to that reliance on law. You need to learn, Paul tells them, to live as free men and women so don’t fall back into reliance on law. Law can only take you so far but there’s much more growth possible in freedom.

Now we come to this subject, this letter to the Galatians, as Americans and as Christians. We don’t read it as subjects of the Roman Empire or residents of the Gulag Archipelago, but as Americans, as people who talk a lot about freedom but are sometimes as much afraid of it as the Galatians. I think some of us are even more afraid of freedom than the Galatians were. It was only a couple of years ago that I was thinking about all this – maybe because I was working on that book I mentioned – my own version of Paul’s letters – and so I was thinking about freedom and wondering why so many Americans are so resistant to any kind of law – even laws intended for our good. I mean, freedom is all very well, some of us seem to be saying but aren’t there some limits?

Those on both sides of the debate have issues with the law. What about, for example, laws intended to keep guns out of the hands of criminals and crazy people? Lots of us think it’s useful to limit our freedom to buy guns and use them. And what about laws intended to provide health care for those unable to afford it themselves? What about laws to protect the atmosphere and preserve life on the planet? Aren’t there times when we need to limit our freedom because it’s dangerous to have angry people with guns and dangerous to have factories belching out coal gas dangerous to try to live without health insurance. So we have one party pushing for laws to preserve us from those dangers and another political party dedicated freedom fro law regardless of consequeces. Some seek to keep us free from certain laws so we can shoot people and pollute the atmosphere and pay our own medical bills if we are able.

There are millions of Americans very angry at the idea that government should place any limits on our freedom even for our own good. Why such fierce opposition? I was really puzzled by it as I said and it occurred to me for the first time – and it maybe should have been obvious – that a great many Americans came here – and still come here – to be free of tyrants. In the 18th century it was tyrants in England, Germany, and France. In the 19th century it was tyrants in Russia and Germany again or still and China and other countries. In the 20th century immigrants came, refugees came, from tyrannies in Germany – again – and Russia and Italy and Japan and China. Late in the 20th century and into the 21st century refugees have come from Cuba and have often joined a political party that warned of oppressive government because they knew about oppressive government and laws that deprived them of freedom. If you come to escape laws that made you victims, it’s maybe not surprising that you would have a deep suspicion of government and pass it on to your children and grandchildren. It might be hard to trust government when the only government you had known had been a tyranny. So I think I have some understanding of where we are today, why so many are so suspicious, so angry, so afraid of the government. It’s understandable that many Americans would instinctively resist any new laws that impinge on their lives however good the purpose. Add to that the fact that the Bible also – especially the New Testament, especially the writings of Paul, provides so negative an outlook on law.

I think the passage we read today is very relevant. Paul begins with his usual greeting: “Grace to you and peace” and all that. Usually he goes on to say some nice things like “I have you in my prayers” Or “I have good memories of my visit to you” but to the Galatians he’s on their case right away. “I am astonished,” he writes, “that you are so quickly deserting the one who called  you in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel . . .” He has, as they, “issues.” And the issue is freedom. “Why have you abandoned the freedom we have as Christians?” I think he would ask that same question of 21st century American Christians. Why are so many of you giving up your freedom. You claim to be defending your freedom, but you arm yourselves with guns as if you were under attack; you claim to be free, but you pass law after law to limit human freedom, you enact a death penalty, you restrict access to abortion, you denounce illegal immigrants, you limit the freedom of others and limit your own freedom at the same time because people who live in fear of others are not free.

you in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel . . .” He has, as they, “issues.” And the issue is freedom. “Why have you abandoned the freedom we have as Christians?” I think he would ask that same question of 21st century American Christians. Why are so many of you giving up your freedom. You claim to be defending your freedom, but you arm yourselves with guns as if you were under attack; you claim to be free, but you pass law after law to limit human freedom, you enact a death penalty, you restrict access to abortion, you denounce illegal immigrants, you limit the freedom of others and limit your own freedom at the same time because people who live in fear of others are not free.

One of the four freedoms that the western allies held up in World War II was “freedom from fear.” Guns don’t free us from fear; they create fear. Walls on our border are the evidence of fear. St John tells us “perfect love casts out fear. “Fearful Christians” is a contradiction in terms and that’s what St Paul is telling the Galatians We are not called to live in fear, behind walls, protected by guns but we are called to live unafraid in freedom because Christ has set us free. That’s Paul’s message to the Galatians and that is also Paul’s message to us. And it begins in the new life we have in Christ.

That life also has a law, but that law is love: to love God and love our neighbor because Christ first loved us. And perfect love casts out fear. Why should we be afraid if God loves us? What is there to fear If God loves us? Who can do us any harm if God loves us? That’s the question Paul asks the Galatians and the same question Paul asks us. What are you afraid of?

Isn’t this then the problem: that we have two kinds of law, laws that restrict us and laws that free us and two attitudes toward those laws. On the one hand those who are fearful of government and on the other those willing to trust government and each prepared to use laws to shape society toward their goals. Paul, I think, would say laws can never save us, whatever our politics laws cannot save us. But fear can imprison us. If Christ has set us free from fear that should enable us to work together to use laws to build a more just and free society. These are the issues to keep in mind as we read again Paul’s letter to the Galatians and Paul’s letter to us.

May 22, 2016

Therefore We Worship

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, on Trinity Sunday May 22, 2016.

There’s a story that’s often told so you may well have heard it before of the priest who was called to give the last rites to a dying man and so he began as the forms provided by asking for a profession of faith: “Do you believe in the holy Trinity, Three persons and one God?” And the dying man looked up and said, “I’m dying and he’s asking me riddles!”

Years ago, I invited a well-known seminary professor to be the guest preacher in the parish I was serving on Trinity Sunday and he preached eloquently about the Trinity. Afterwards a member of the congregation thanked him for his sermon and told him how helpful it had been. “I never could understand the Trinity before,” she said, “but now I do.” The professor looked surprised and said, “I guess I said something wrong.”

in the parish I was serving on Trinity Sunday and he preached eloquently about the Trinity. Afterwards a member of the congregation thanked him for his sermon and told him how helpful it had been. “I never could understand the Trinity before,” she said, “but now I do.” The professor looked surprised and said, “I guess I said something wrong.”

But what’s so strange about the Trinity? When you stop to think about it, trinities are everywhere. “Animal, vegetable, mineral.” Ford, Chrysler, General Motors Clinton, Saunders, Trump. Christianity, Judaism, Islam. And it’s not that there aren’t other forces out there, other brands of cars, other political candidates, other religions, but most of the time we seem to come down to three.

You might say, “Well, but don’t we have a two party system in this country?” Technically perhaps we do, but it doesn’t work. We all know it doesn’t work. Through most of our history, the two parties have been loose alliances within each of which you had conservatives and liberals so the borders were very flexible and usually overlapped so there were Democrats more conservative than most Republicans and Republicans more liberal than many Democrats and lots of room for compromises and bargaining and getting things done. But in recent years the parties have become more and more rigid, conservative Democrats have become Republicans and liberal Republicans have been frozen out and we have wound up with gridlock: two narrowly ideological parties offering “my way or the highway” with no room to maneuver or compromise or get anything done. At this very moment we are waiting to see whether an extremist Republican party can hold together or whether a third party will appear. I’m probably not the only one not satisfied with the two choices we seem to be faced with.

Dualism doesn’t work. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, it takes three to tango. We need trinities. And what a difference a trilogy makes. You see, the problem is that when you just have two, it’s a fight two is a battle: one has to win. Three provides alternatives, room for shifting alliances: two weak teams can stand up to one strong team. A world divided between two great powers is a world where there has to be a winner and a loser. With three, it’s a different world with room for maneuver. I have no respect or liking for Nixon or Kissinger but they did one good thing which was to move from the dangerous, bi-polar post-world war II world to a trinitarian world, no longer the US vs Russia but a third party to take into account which made a safer world for everybody.

Most of us grew up in a different Trinitarian world of communism, fascism, and democracy – but communism and fascism took a dualistic view of the world, us vs. them, in which they had to conquer. But democracy won out because it contained room for differences within itself. Two is never a lasting solution. Two thousand years ago there were theologians who argued for a binary world, a world torn between the spiritual and the material, between good and evil: “dualism” is one name for it. There are fancier names for it: Manicaeanism, Gnosticism. You find it in Eastern religions: the Yin and the Yang. Jews and Christians said, “No; there is one God, creator of all things. The spiritual is good, but so is the material: God created it. Evil exists, but evil has no ultimate power. “The devil,” the Bible tells us, “has come down to earth in great wrath, because he knows that his time is short.”

Ultimately there is no room for evil in God’s universe. Evil has no ultimate power. Nor does there need to be a world of binary opposites, of dualism, nor even of shifting human trinities: because the God we worship is a Trinitarian God encompassing our conflicts, resisting simplistic solutions, insisting on the mystery beyond human knowledge and understanding. a mystery at the heart of the world. Three in one and one in three. Not a cold monolith but not an incoherent diversity either. Three and yet equally one; one and yet equally three. It’s the richness of three that leads to worship. One is lonely and sterile. Two is dangerous. But three opens up a world too big to control, rich with possibility.

of the world. Three in one and one in three. Not a cold monolith but not an incoherent diversity either. Three and yet equally one; one and yet equally three. It’s the richness of three that leads to worship. One is lonely and sterile. Two is dangerous. But three opens up a world too big to control, rich with possibility.

I remember reading somewhere once that there’s an Eskimo counting system that goes, “One – two – many.” My mother used to say that you don’t have a family until you have more than two children. With two children, she pointed out, you can grab one with each hand, but with three there’s always one out of control. That was her definition of family and she knew, because there were four of us. It’s not just our hands, but I think our minds are binary also. A unitarian God is simple and logical. A binary God of good and evil makes sense to our limited minds. But a trinity moves beyond what our minds can fathom into the mystery at the heart of the universe, more than we can grasp and analyze, always more, always beyond us.

I suggested that one of our human Trinities is Judaism, Islam, and Christianity but that trinity like fascism, communism, and democracy, is an unstable Trinity because two of the members are unitarian which is a logical solution but lacks enough room for mystery. A God I can understand is not God. So I’m not here today to explain the Trinity but to explain, if I can, why at the heart of our faith there’s a mystery that leaves us free to respond in love.

There’s a human instinct to want to make things simple, to reduce things to a binary choice: Black or white, A or B, True or False. Choose up sides, win or lose. Life is not that simple. God is not that simple. And I’m glad of it. Can you imagine how boring life would be if we had all the answers, if our human minds could grasp the ultimate nature of God. But a God I can understand is not a God I can worship. and worship is critical.

Way at the back of the Prayer Book is a strange document called the Creed of Saint Athenasius or the Athenasian Creed or the Quicunque Vult. It’s on page 864 but don’t look it up now. It begins this way: “Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that he hold the Catholic faith and the Catholic faith is this, that we worship one God in Trinity and Trinity in unity.” I had a professor in seminary who liked to say, “It’s simpler than that. The catholic faith is this, that we worship.” And that is the essence of it: a God beyond  understanding, a triune God, must be worshiped; there’s no other adequate way to respond. We will not and cannot understand, but we can worship and we must. There are churches where people come together on Sunday to be inspired or lectured or bored; we come to worship, to recognize a God beyond understanding and to fall down in worship.

understanding, a triune God, must be worshiped; there’s no other adequate way to respond. We will not and cannot understand, but we can worship and we must. There are churches where people come together on Sunday to be inspired or lectured or bored; we come to worship, to recognize a God beyond understanding and to fall down in worship.

BUT! BUT! There are lots of things I do not understand that I do not worship: computers head the list. Well, there are, of course, people who do worship computers, center their lives on a silicon box. Or maybe their cell phone. They can’t live without it. But that’s to worship the creation not the Creator. And it’s not that we have a choice between worship and understanding, not an either/or that lets me off the hook of trying to understand, no, we have no business on our knees until we have gone as far as we can with our heads. It’s not either/or but both/and: understanding and worship or as someone once said, I worship in order to understand. It’s not giving up, it’s coming to understand so much that we are awestruck, and go on to the next stage. I might even say that worship is a deeper kind of understanding, beyond logic, beyond what the mind can see. When we have gone that far, as far as our minds and understanding can take us, we can go further when we worship.

I’ve never been in a mosque to worship but I’ve been in more than one mosque and struck by the emptiness of it: no symbols, nothing to represent God – but for the Muslim, the Koran itself becomes a sacred thing, a visible symbol of Allah. Synagogues also are usually rather stark and empty but front and center there will be a bemah and a scroll of the Torah and during the service the Torah will be taken out with great reverence and carried up one aisle and down another and people will reach out to touch it. We want some kind of contact with God, some symbol we can touch and if our religion offers nothing more than a sacred book, we will touch it to try to make contact with the Holy. But a Unitarian God remains remote. The God we worship is not remote: our God “Almighty, invisible, In light inaccessible, hid from our eyes . .” is also the God who was laid in a manger and nailed to a cross, who shared our human life to the full and took our human nature to the throne of the Most High. Therefore we worship, but therefore also we come here today to taste and touch and share the bread and the wine, created substances in which the uncreated God comes to us to unite us also in the mystery we worship.

And that’s what Incarnation is all about. It’s what non-Trinitarian monotheism lacks: God not in a book or a scroll but closer than those could ever be: here, within us, in our own human lives. The First Epistle of John puts it well – chapter one, verse one That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched—this we proclaim concerning the Word of life. This we proclaim, the Triune God at the heart of the universe and in the heart of our lives in the risen Christ.

April 2, 2016

Two Kinds of Christians

A sermon preached at the Church of the Incarnation on April 3, 2016, by Christopher L. Webber.

I had a seminary professor who said there are two kinds of sermons: one kind in which you proclaim the Gospel and therefore begin, “In the Name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” and another kind in which you are less definitive, more opening a discussion in which other viewpoints are possible, and then you might begin as I did today: Let the words of my mouth and the meditations of our hearts be acceptable in your sight, O Lord our strength and our redeemer.

So what I want to do today is not proclaim the gospel, but explore some issues and invite a response because there are issues we need to think about and I don’t think I have the last word on the subject. The apostles said, “We must obey God rather than any human authority.” Where are the stress lines today between God and human authority? How do we serve God in the political world?

I’d like to begin by suggesting that there are two kinds of Christians in this country and the difference between them is sharper than ever before. I say “in this country” because I think the difference exists elsewhere but not as sharply as here because our history is unique. Two kinds of Christians came here. You might call them “establishment” and “dissenters.”

Massachusetts Bay was settled by Christians fleeing the English establishment. They were the dissenters, uncomfortable with an established church. But they didn’t want freedom for everyone to dissent, they wanted a church where everyone thought the way they did or would get out as Roger Williams did to Rhode Island and Ann Hutchinson did to Connecticut and still others did again and again moving on to the frontier as long as there was a frontier, but always dissenting, always questioning, always valuing the individual over the larger society.

Then there were the Christians who were the establishment, who came to Virginia, for example, and recreated as nearly as they could the English establishment with a Governor in place of the king and a church supported by taxes. One kind of Christian worried most about individual freedom; the other kind cared more about an orderly world where everyone knew his or her place. Carried to its logical extreme establishment Christians saw no harm in slavery since the slaves also had their place, clearly established.

Carried to its extreme, the New England pattern was not only willing to expel the Roger Williamses and Ann Hutchinsons but saw no harm in killing witches; they were looking for a pure society where everyone agreed with everyone else.

You could look no further than Ronald Reagan as a prototype of the dissenting model. Reagan was brought up in a small mid-western church whose pastor frequently cited the Puritan heritage and the shining city on a hill, stressing the individual, dedicated to limited government.

On the other hand, Franklin Roosevelt would exemplify the establishment figure: Episcopalian, Harvard educated, putting programs in place for the needs of the whole society. There are two kinds of Christians in this country and have been from the beginning, but the differences between them it seems to me are sharper than ever before. Oddly, the difference is sharpest right now within one of our political parties rather than between them. Republicans see their party divided between the so-called establishment on the one hand and the radical individualists on the other. It’s the radical individualists, oddly enough, who are called “conservatives” in the media. But if words still mean anything it’s the establishment who are the conservatives. People who want to keep things as they are are the real conservatives. Hillary Clinton is really much more of a conservative than Ted Cruz or Bernie Sanders who want to make radical changes and both of them are more conservative than Donald Trump who wants to change almost everything. He’s the ultimate radical, the ultimate individualist.

But it’s the people called conservative in the media who are individualists first of all, people who want as much freedom from the state as they can possibly get. So they reject programs like social security and the affordable care act and so on. They don’t want the state involved in their lives – with the single odd exception of abortion and birth control where they do want the state to make the rules and limit people’s freedom. It’s not logical that the same people who inveigh against the government controlling our lives would work to control people’s lives where it matters most – but logic is not their strong point.

Now these are obviously political issues, but they are also theological issues, most obviously in relation to issues of birth control and abortion. But social security and affordable care and the use of torture and nuclear weapons and immigration are theological issues also. They have to do with the working out of the great command: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. They have to do with the question Jesus was asked: Who is my neighbor? Is my neighbor a Syrian refugee or a Mexican immigrant or a young woman unable to face a pregnancy or a Gulf War veteran living on the street with post traumatic stress disorder? Who is my neighbor? What is my responsibility to my neighbor and to the state and to God? We fight these things out as matters of politics, but if we are Christians, the division is first of all theological and it runs between our churches and within our churches and it goes back to our origins in dissent and establishment and the tendency of one side to stress individual freedom and the other side to stress social concerns. You can see it reflected in the web pages of different churches. The biggest Baptist church in Dallas, for example, says, we believe “that God desires a personal relationship with every individual . . . ” but Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, talks about its “social justice endeavors” and the Church of the Incarnation says, “We live and share the Good News of Jesus Christ through worship, education, fellowship, pastoral care, and service to the world” There’s nothing in either Episcopal statement about a personal relationship with Jesus and nothing in the Baptist statement about society or justice.

Of course, as an Anglican I would also want to say there’s truth in both positions. God does desire a  personal relationship with each individual, but God also draws us together in communities and calls on us to build up communities in which we take responsibility for each other.

personal relationship with each individual, but God also draws us together in communities and calls on us to build up communities in which we take responsibility for each other.

Now, I’m saying all this because we had a reading this morning that put all this in the starkest possible terms. It tells us how the apostles were brought before the authorities in the early days after the resurrection. They were told that they were making trouble; they were told that they were creating divisions; they were told that they were disturbing the peace of the community; and they were told they should stop it before the situation got any worse. They were told they were making trouble, but “the apostles answered, ‘We must obey God rather than any human authority.’”

Well, I’m an Anglican and I understand where the authorities were coming from. How can you have a peaceful community if individuals can all respond to their own particular vision without regard for its impact? But as an Anglican I also have to ask how can you have a just community if God’s will is neglected? How do you balance out the establishment desire for stability and the radical desire for freedom? What does God ask of us in terms of society, in terms of our social obligations?

I’ve just finished reading a 600-page biography of Abraham Lincoln and, of course, it walked me back through the Civil War, the catastrophe that re-shaped this nation and you can see it again in terms of those two perspectives on human life: the slave-holding south where some thought it was perfectly fine to  worship God and establish a personal relationship with Jesus while at the same time holding other people in slavery and the abolitionist north where many others felt that slavery was inconsistent with God’s will to create a just society.

worship God and establish a personal relationship with Jesus while at the same time holding other people in slavery and the abolitionist north where many others felt that slavery was inconsistent with God’s will to create a just society.

Well, that was then and this is now but the same fault lines still exist. Slavery may be gone, but that same fundamental division haunts us still and I think we need to be very clear about the source of the problem and try to work through it in faithfulness to the risen Christ who calls us into a personal relationship with himself and a loving relationship with our neighbor. We need to ask how we are called to respond both as individuals and as a church and we need to do whatever we can to help our friends and neighbors see what the issue is and try to approach it insofar as possible without anger and hostility and division.

I’m sure you get as tired as I do of the way the media seems to portray Christians as narrow-minded, negative people – against immigration, against health care, against so many things and angry about it – and then the media ignore the maybe quieter work going on by more traditional Christians – catholic and liturgical Christians: Anglican, Lutheran, Roman, Orthodox and others – to reach out to the homeless and welcome the newcomer and act the way we think Jesus would want us to act, changing not just individual lives but the whole society. Now you can call that “establishment” if you want but I think that misses the point. Peter and John were not speaking for the establishment in this morning’s reading but neither were they speaking as solitary individuals responding to God on the basis of individual conviction. They didn’t say, “I must obey God,” but “we” must obey. I think that’s important. They are acting as a church, as a  society within a society, as Christians caught in a bind, as we often are, between dissent and establishment and having to make a choice.

society within a society, as Christians caught in a bind, as we often are, between dissent and establishment and having to make a choice.

It’s worth noticing how the Collect for this Sunday deals with these issues: “Grant” it says “that all who have been reborn into the fellowship of Christ’s Body may show forth in their lives what they profess by their faith . . .” Do you see what that does? It grounds our discipleship in our membership. It’s talking about the consequences of our baptisms and it says we have been reborn. It says we have been baptized into a personal relationship with Jesus, yes, but into the fellowship of Christ’s Body, into a corporate relationship with each other, and it’s in that body and with that body that we are to show forth what we profess, that we are to act as if we believe what we say, that our faith makes a difference, that our love for our neighbor needs to be acted out and can be because in Christ, drawn into a personal relationship with Jesus as our Savior, we are members of his body and never acting alone.

March 23, 2016

Making a Difference

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, on Maundy Thursday, March 24, 2016.

Back in September, scientists turned on a new machine that they had constructed at enormous cost: 350 million for starters in 1995 and another 660 million for a complete overhaul in 2015 The English and Australians and Germans were involved; so were Cal Tech and MIT. They call it LIGO because nobody can remember Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. It’s designed to detect gravity waves and prove or disprove an aspect of Einstein’s theory of relativity.

They turned it on on September 14 last year and almost  immediately they heard the distinctive chirp that said something had been detected. They then spent five months analyzing the chirp before telling the world on February 11 what they had heard. What they had heard was the result of the collision of two black holes, one 29 times as massive as our sun and the other 26 times as massive. These two black holes collided and in merging gave off so much energy that gravity itself was warped and the resulting gravity waves which Einstein had predicted almost exactly one hundred years ago produced that tell-tale chirp.

immediately they heard the distinctive chirp that said something had been detected. They then spent five months analyzing the chirp before telling the world on February 11 what they had heard. What they had heard was the result of the collision of two black holes, one 29 times as massive as our sun and the other 26 times as massive. These two black holes collided and in merging gave off so much energy that gravity itself was warped and the resulting gravity waves which Einstein had predicted almost exactly one hundred years ago produced that tell-tale chirp.

The instruments scientists created for the purpose are capable of measuring a variance in the distance between earth and sun of the diameter of a human hair and gravity waves that are 4 one-thousandths of the charge diameter of a proton which is so small it’s ridiculous. Two black holes colliding 1.4 billion light years away produced a gravity wave that the LIGO measured and produced the chirp that thrilled the scientists.

It’s an amazing universe. Can you imagine, can your mind grasp, can you comprehend a collision so far away that if you could travel at the speed of light for a billion years you would not be much more than halfway to where it used to be when you started. Who knows how much further you could go and still be within  this universe? And who knows whether there are other universes beyond ours?

this universe? And who knows whether there are other universes beyond ours?

But what got my attention was the colossal impact that produced a barely measurable result. And I wondered whether the experiment could be reversed and a tiny, almost unmeasurable change here produce cataclismic effects there. Now you might say, “Wait a minute; you can’t do it backwards. Just because a massive collision produced so much energy that even a billion light years away, it makes an impact doesn’t mean that a tiny release of energy here will expand and destroy black holes a billion light years away.”

But why not? Don’t the scientists tell us that the movement of a butterfly’s wings in China affects the weather in the United States? One meteorologist remarked that if the theory were correct, one flap of a sea gull’s wings would be enough to alter the course of the weather forever. If we could just figure out which butterflies make it rain in San Francisco, wouldn’t that be wonderful!

I want you to think about impact. I want you to think about your impact and whether you could produce a chirp in a LIGO or change the weather in Tahoe. I want you to think about the inter-relatedness of this unimaginable universe and this unimaginable planet earth and a God so far beyond our imagining as to be the Creator of it all, a God so far beyond our imagining as to create you and me and love us. But I want you still to think about how vast the discrepancy can be between cause and effect. Do you remember, for another example, how we had to ban cfc (chlorofluorocarbon) in spray cans some years back to prevent a hole opening up in the ozone layer that could have destroyed life on earth? We had these neat new devices that gave us instant whipped cream and bug spray and so on but threatened all life on earth because it doesn’t take much to unbalance the web of life. It doesn’t take much to alter it. It doesn’t take much to make a difference.

I’m coming slowly around to the events of Maundy Thursday, but I want to make one more stop on the way. Just tonight we celebrate another event which, at the time, must have seemed about as un-impact-ful as an event could be, as unlikely to be felt even by a LIGO. Dom Gregory Dix, an English Anglican monk, wrote about it in a very influential book about the liturgy back in the 1950s. He wrote about what he called

a thing of an absolute simplicity — the taking, blessing, breaking and giving of bread and the taking, blessing and giving of a cup of wine and water, as these were first done with their new meaning by a young Jew before and after supper with His friends on the night before He died. He had told his friends to do this henceforward with the new meaning `for the anamnesis of Him, (the re-calling, calling back of him) )and they have done it always since.

An insignificant event; not noticed even by the passers by in the street and certainly not by Pilate in his palace. But Dix proceeds to recite a litany on this theme: the unimaginable consequences of a seemingly insignificant event. He asked:

Was ever another command so obeyed? For century after century, spreading slowly to every continent and country and  among every race on earth, this action has been done, in every conceivable human circumstance, for every conceivable human need from infancy and before it to extreme old age and after it, from the pinnacle of earthly greatness to the refuge of fugitives in the caves and dens of the earth. Men have found no better thing than this to do for kings at their crowning and for criminals going to the scaffold; for armies in triumph or for a bride and bridegroom in a little country church; for the proclamation of a dogma or for a good crop of wheat; for the wisdom of the Parliament of a mighty nation or for a sick old woman afraid to die; for a schoolboy sitting an examination or for Columbus setting out to discover America; for the famine of whole provinces or for the soul of a dead lover; in thankfulness because my father did not die of pneumonia; for a village headman much tempted to return to fetich because the yams had failed; because the Turk was at the gates of Vienna; for the repentance of Margaret; for the settlement of a strike; for a son for a barren woman; for Captain so-and-so wounded and prisoner of war; while the lions roared in the nearby amphitheatre; on the beach at Dunkirk; while the hiss of scythes in the thick June grass came faintly through the windows of the church; tremulously, by an old monk on the fiftieth anniversary of his vows; furtively, by an exiled bishop who had hewn timber all day in a prison camp near Murmansk; gorgeously, for the canonisation of S. Joan of Arc—one could fill many pages with the reasons why men have done this, and not tell a hundredth part of them. And best of all, week by week and month by month, on a hundred thousand successive Sundays, faithfully, unfailingly, across all the parishes of Christendom, the pastors have done this just to make the plebs sancta Dei—the holy common people of God.

among every race on earth, this action has been done, in every conceivable human circumstance, for every conceivable human need from infancy and before it to extreme old age and after it, from the pinnacle of earthly greatness to the refuge of fugitives in the caves and dens of the earth. Men have found no better thing than this to do for kings at their crowning and for criminals going to the scaffold; for armies in triumph or for a bride and bridegroom in a little country church; for the proclamation of a dogma or for a good crop of wheat; for the wisdom of the Parliament of a mighty nation or for a sick old woman afraid to die; for a schoolboy sitting an examination or for Columbus setting out to discover America; for the famine of whole provinces or for the soul of a dead lover; in thankfulness because my father did not die of pneumonia; for a village headman much tempted to return to fetich because the yams had failed; because the Turk was at the gates of Vienna; for the repentance of Margaret; for the settlement of a strike; for a son for a barren woman; for Captain so-and-so wounded and prisoner of war; while the lions roared in the nearby amphitheatre; on the beach at Dunkirk; while the hiss of scythes in the thick June grass came faintly through the windows of the church; tremulously, by an old monk on the fiftieth anniversary of his vows; furtively, by an exiled bishop who had hewn timber all day in a prison camp near Murmansk; gorgeously, for the canonisation of S. Joan of Arc—one could fill many pages with the reasons why men have done this, and not tell a hundredth part of them. And best of all, week by week and month by month, on a hundred thousand successive Sundays, faithfully, unfailingly, across all the parishes of Christendom, the pastors have done this just to make the plebs sancta Dei—the holy common people of God.

And even if you can perhaps imagine a carefully planned bread-breaking ceremony having some lasting influence, can you imagine anything, anyone, less powerful, less influential than a dying criminal with his arms nailed to a wooden cross? The French author, Anatole France, put it in context in a short story written in 1902 called The Procurator of Judea in which a retired Roman official falls into conversation with a man named Pilate also long retired. It turns out that both of them had served in the middle east as we would call it and the retired official tells Pilate of the love he had once for a Jewish woman who suddenly disappeared. He searched for her until he says,

I learned by chance that she had attached herself to a small company of men and women who were followers of a young Galilean thaumaturgist. His name was Jesus; he came from Nazareth, and he was crucified for some crime, I don’t quite know what. Pontius, do you remember anything about the man? Pontius Pilate contracted his brows, and his hand rose to his forehead in the attitude of one who probes the deeps of memory. Then after a silence of some seconds: ‘Jesus?’ he murmured, ‘Jesus of Nazareth? I cannot call him to mind.”

The crucifixion, Anatole France is probably quite right, probably made no impact at all on the man who ordered it and whose  name we recite every time we recite the Creed. And who would remember one out of all the thousands crucified by the Roman Legions; what difference would it make: one more or one less?

name we recite every time we recite the Creed. And who would remember one out of all the thousands crucified by the Roman Legions; what difference would it make: one more or one less?

But we are talking about a world in which the fluttering of a butterfly in Brazil can set off a tornado in Texas. A world where the decisions that matter are somehow not made in colossal buildings in the Kremlin, or Beijing, or Washington nor by jihadists in tiny Parisian apartments or militants in Cairo or Taliban fighters in Afghanistan. Ultimately it is not power – not even the power of two black holes colliding and making a chirp – that governs this world, at least not power as this world’s powers understand it and exercise it. But in this vast universe – this is my point – the smallest things can make an infinite difference. And Christians have claimed that the lonely death of one man has changed the world forever. The cross changes everything for us and through us must – and will – change the world.

Put it again in the larger context of the immeasurable created universe: that God, the God of black holes and billions of light years, that God, that God, that Creator should have done something so inconsequential, so over-lookable as to plant the seed of life on one small blue planet in a vast universe of black holes and spiral nebulae and spinning rocks without atmosphere or water or oxygen – a universe devoid of life so far as we know except for one tiny rock on which over millions of years a species of life evolved capable of looking around with awe and wonder and acknowledging a Creator – a loving, personal Creator who seems to have brought it all into being for us – for you – and in the expectation that you and I – always only a few – and never the ones who seemed to have the power, that you and I, obeying Christ’s command and sharing as we do tonight in this bread and wine the life of Jesus – that you and I would make a difference also.

February 27, 2016

What Is God Like?

A sermon preached at the Church of the Holy Innocents, San Francisco,, California on February 28, 2016.

How do we know what God s like? Maybe someone told us something: your mother or father, maybe; Maybe a church school teacher; maybe a friend. Maybe you read a book – or lots of books. Maybe you just sort of picked up ideas here and there.

I think the readings you heard this morning, one from the Old Testament one from the Gospel, throw some light on the subject. I think they give us several different ways to think about God and who God is. First there’s a story about a burning bush in the desert, (Exodus 3:1-15) then there’s a story about a wall that fell on some people, (St.Luke 13:4-5) and then there’s a third story about a gardener and a fig tree (St. Luke 13:6-9). Three stories that give us clues about how we know God.

So we hear the stories and then it’s up to us to think about them and see what we can learn. That, by the way, is the plus and the minus of being an Episcopalian: we are asked to think. And I think most of us do that at least a little bit and once in while and what we know about God is the result of that process. We know about God by thinking about something we heard but thinking is hard work and I think how we want to know about God is in the first two stories where thinking is not required. we want to see a burning bush or have a wall fall on us. We want evidence. We want to be sure.

I remember a scene in an Ingmar Bergman movie (The Seventh Seal) years ago in which the hero says, “I want God to reach out his hand and touch me.” Wouldn’t it be nice to be sure? Sometimes that happens. It happened to Moses at the burning bush. Moses was Jewish, you know, but he had been brought up Egyptian. He had all the privileges of the royal palace and saw his brothers and sisters being slowly killed off in slavery and it upset him. He got angry enough one day to kill one of the slave drivers and he fled from Egypt to escape punishment and he found a job taking care of a flock of sheep in the desert, and there in the desert, as he stood and watched the sheep, with nothing to do  except ponder the mysteries of life, God got his attention beyond doubt or question with a burning bush. He saw a fire that burned the bush but did not consume it. Now that’s unusual; it calls for a response, and Moses responded and he was told what he had to do. God spoke to him and gave him clear directions. Go speak to Pharaoh and tell him, Let my people go. Don’t you wish God would do that for you?

except ponder the mysteries of life, God got his attention beyond doubt or question with a burning bush. He saw a fire that burned the bush but did not consume it. Now that’s unusual; it calls for a response, and Moses responded and he was told what he had to do. God spoke to him and gave him clear directions. Go speak to Pharaoh and tell him, Let my people go. Don’t you wish God would do that for you?

But I think Jesus is telling us in the Gospel that it’s time to grow up and not wait for God to hit us over the head with something so miraculous and wonderful that it leaves no room for doubt, something that compels our response, that eliminates our freedom. Maybe there was a time in the childhood of our race when we needed burning bushes and a path through the sea and all that sort of thing. But we’re grown ups and we need to be free to think and understand and free to choose.

Isn’t that what Jesus is telling us in that story about the wall. He asked the crowd, “What about those eighteen who were killed when the tower of Siloam fell on them–do you think that they were worse people than all the other people living in Jerusalem?” You get the impression it was a big news event, something the disciples might have seen on the evening news the previous day. There was this new building going up and maybe the construction company cut a few corners, paid off the building inspectors, put too much sand in the concrete, and at a point the whole thing collapsed and some people were killed. That’s not something unique that never happened before or since. It happens still. You hear about it. You hear about it more when there’s an earthquake in a third world country where it’s easier to bribe the building inspectors and there are lots of buildings that will fall – not, unfortunately on the cheating contractors who deserve it but on innocent people who became their victims. And sometimes it happens here too. And not always because someone cut corners. Sometimes they do everything right and it still falls down. But the point is that people got killed and the conventional wisdom then was that there was a reason for it: the people who died must have been bad people, they brought it on themselves.

That does two things. It gives us a nice easy explanation of something awful and it makes us feel a bit safer ourselves — at least it does if we’ve been behaving ourselves lately. It gives us an explanation but it also provides a picture of God as an angry parent that maybe raises more questions than it answers.

So what is God like? How do we know? I think God wants us to know God; God wants us to know the love of God and God wants us to respond to it and obviously God could do whatever it takes: God could put a burning bush in our path or drop a wall on us – whatever it takes to get our attention. God could – but usually God doesn’t and that leaves us free to ignore God if we want. We can live our own lives, make our own mistakes, and God seems generally to leave us alone as if it doesn’t matter. How come? Why doesn’t God work harder to get our attention? How come it’s so easy to ignore God most of the time? Wouldn’t you think God would want us to notice, plant a few more burning bushes here and there, drop a few more walls on people here and there.

Well, think some more about that tower that fell. Did God make it fall? Give it a push? That would certainly get people’s attention. But there are problems. First of all, if a wall falls on you and kills you, you don’t usually learn anything from it because you’re dead. It’s too late. Of course, there will be lots of other people who can learn something from it: all the people that hear the news. If you hear about it, you can explain it as God dealing with bad guys, and that will be a good lesson for lots of other people, but what does it tell you about God? It tells you that God is like an angry parent. And some people do think that and it gives them a framework for understanding the world.

But it’s wrong. That’s what Jesus was telling the disciples. It’s wrong. That’s not who God is. “Do you think the people that died, were worse than anyone else in Jerusalem?” he asked. “Do you think God arranged that the eighteen worst people in Jerusalem were all at the right place at the right time to get their come-uppance? Is that how God works?” I mean, yes, that would be a nice logical world to live in with clear laws and clear punishments and a God who couldn’t be doubted. But it’s not the God of the Bible. We might want to run the world that way, but God doesn’t.

And there are reasons: think of the problems it causes. Suppose you can mix sand with the cement and get away with it; people will keep on dying, and even worse things will happen. There will be famines and wars and unfair tax laws and children starving and politicians conniving and no clear evidence that there even is a God. You can live your whole life as if there is no God and seem to get away with it. You can be rich and famous and lie and cheat and no towers ever seem to fall on you while someone else, good and decent and going to church every Sunday suddenly has the wall fall on them, What kind of world is that? What kind of a God would have that kind of world? Well, our God. The God made known in Jesus of Nazareth.

We get a glimpse of that God in today’s gospel, because Jesus also tells his disciples a little story about a man with a fig tree that never seems to produce figs. What does that have to with falling walls? Everything. These are not two totally disconnected stories – not at all. Listen again. “A man had a fig tree planted in his vineyard; and he came looking for fruit on it and found none.” So he tells the gardener to cut it down; why waste space in the garden on a tree that bears no fruit? But the gardener says, Let’s give it another year; let me give it a little more help; let’s wait and see.

And the point is that God is like that gardener and we are like that fig tree, and the years go by and we produce no figs or certainly not very many and the logical question would be, “Why?” Why shouldn’t God expect some return on the investment? Isn’t it time to fish or cut bait? Isn’t it time to put that land to better use? Why not a burning bush or falling wall to get our attention, remind us that we’re here for a reason? Why should God continue to be patient? But God is patient. The God Jesus tells us about, the God we worship here, is very patient. Year after year, we make our mistakes, we mess things up, and you do have to wonder why God doesn’t either put a burning bush in our path or say, “Enough already.” Why doesn’t God do that? It’s because God is patient, and because God is merciful: that’s why.

God wants us to think and to understand. And, yes, it means that sometimes the walls fall on the wrong people but after a while people begin to notice that we have some responsibility in the matter, and someone suggests that we need to create a system of laws to protect us and others from the unscrupulous builders who put up faulty towers, the unscrupulous polluters who endanger our health and our climate, and do something about it and create better building codes and environmental protection and indict more corrupt building inspectors and more self-serving politicians – which would never happen if God always pushed over the faulty towers and always had them fall on corrupt politicians and we didn’t need to worry. Why should we fix the building code if God keeps us safe anyway? Slowly and unpredictably, we do learn from these things.

And yes, innocent people suffer along the way but unfortunately we would never learn if they didn’t and we would never act responsibly unless God insisted that we be responsible, that we are responsible. I think God wants us to grow and take responsibility and it seems as if God will not protect us from the consequences of our failure to do that. There’s a price to pay for our failures. But one of the annual lessons of Lent and Holy Week and Good Friday is that though innocent people suffer God in Christ has shared that suffering. If the cost of our freedom is the suffering of innocent people, God knows that and God suffers also. So it’s about all these things: it’s about a merciful and patient God and a bunch of slow learners who test God’s patience daily.

But not forever. There is an end to it. The epistle reading reminds us of that. “If you think you are standing, watch out that you do not fall.” Sooner or later, we will be judged. We test God’s patience at our own risk and God is not mocked. I think it would not be smart to put off any real commitment on the off chance that we are so important to God’s plan that we will find a burning bush on our path home today to convince us beyond doubt or question of what we have to do. No, God wants us to grow up and respond freely out of love, not force.

So how do we know God? One way is by thinking about things we hear about: like today’s readings. Here God is revealed, God is made known, no longer in a burning bush not at all in a falling tower but in a simple story that Jesus told about a farmer and a fig tree. What is God like? God is like the gardener. God is patient and God is merciful, and that’s more than enough reason to be patient and merciful ourselves and to be here week by week and to be on our knees day by day to give thanks for God’s mercy.

February 19, 2016

Be a Pilgrim

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at the Church of the Incarnation, San Francisco, on February 21, 2016.

I’m wearing a scallop shell this morning because some ten years ago I was in Santiago in the northwest corner of Spain and the scallop shell is a symbol of pilgrimage to Santiago. The name Santiago means Saint James and the legend is that Saint James, one of the 12 apostles, went to Spain as a missionary and eventually, to make a long story short, died and was buried there. That’s the furthest west any of the apostles went and so his tomb became an important pilgrimage site especially for western  Europe. People came from all over Europe to visit his tomb and they would pick up a scallop shell from the nearby seacoast and take it home as a souvenir and evidence that they had been there. So I have the evidence that I was there, but I don’t feel much like a Santiago pilgrim. In fact even today to get a certificate that you have really made the pilgrimage you have to walk at least the last 100 miles. I only walked the last few 100 yards and that doesn’t count.

Europe. People came from all over Europe to visit his tomb and they would pick up a scallop shell from the nearby seacoast and take it home as a souvenir and evidence that they had been there. So I have the evidence that I was there, but I don’t feel much like a Santiago pilgrim. In fact even today to get a certificate that you have really made the pilgrimage you have to walk at least the last 100 miles. I only walked the last few 100 yards and that doesn’t count.

I’m wearing the scallop shell because I wanted a symbol this morning to help focus attention on the Old Testament reading. The story picks up from last week’s reading which reminded us that we are the descendants of wanderers. “A wandering Aramean was my father;” that’s what last week’s reading told us. It reminded us that the Jewish people have been nomads and wanderers and we are their children. This week we continue with the story of Abraham who left Iraq to go to Canaan.

For 12 years I served the parish in Canaan, Connecticut, so I feel a very direct tie to this story. Canaan was the goal of some of the first pilgrims and Canaan, Connecticut, was the land of promise for some New England wanderers. California also has been a land that wanderers have come to from many places: Asia, first of all, across the Bering Strait, and then from South America and Europe and the eastern states. You and I are wanderers or descendants of wanderers. Few of us go back to the forty-niners but the story of California begins with pilgrims and wanderers, most of them, of course, in search of something more material than a spiritual reward.