John G. Messerly's Blog, page 82

March 23, 2017

Summary of Schopenhauer on Hope: From “Psychological Observations”

I would be remiss if I didn’t consider the critique of hope found in the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. (I considered his view of pessimism in my last post.) He speaks of hope most directly in an essay titled, “Psychological Observations.” Immediately preceding his brief discussion of hope, he makes these pertinent observations:

… it is usual throughout the whole world to wish people a long life. It is not a knowledge of what life is that explains the origin of such a wish, but rather knowledge of what man is in his real nature: namely, the will to live.

The wish which everyone has, that he may be remembered after his death, and which those people with aspirations have for posthumous fame, seems to me to arise from this tenacity to life …

We wish, more or less, to get to the end of everything we are interested in or occupied with; we are impatient to get to the end of it, and glad when it is finished. It is only the general end, the end of all ends, that we wish, as a rule, as far off as possible.

These considerations of wishing, especially that we don’t die, lead him directly to his discussion of hope.

Hope is to confuse the desire that something should occur with the probability that it will. Perhaps no man is free from this folly of the heart, which deranges the intellect’s correct estimation of probability to such a degree as to make him think the event quite possible, even if the chances are only a thousand to one. And still, an unexpected misfortune is like a speedy death-stroke; while a hope that is always frustrated, and yet springs into life again, is like death by slow torture.

Notice here that his conception of hope entails expectation, the kind of hope I also reject. But surprisingly, in the following passage he seems to defend hope:

He who has given up hope has also given up fear; this is the meaning of the expression desperate. It is natural for a man to have faith in what he wishes, and to have faith in it because he wishes it. If this peculiarity of his nature, which is both beneficial and comforting, is eradicated by repeated hard blows of fate, and he is brought to a converse condition, when he believes that something must happen because he does not wish it, and what he wishes can never happen just because he wishes it; this is, in reality, the state which has been called desperation.

Essentially he’s saying that to lose expectant hope, which he says is both beneficial and comforting, is to despair. This suggests that hope is a good after all. Yet this brief discussion of hope must be taken in the context of his entire philosophy. First, what he writes here is more description than prescription; he says that people do find comfort in hope, not that they should. Second, he would reject the action motivating, attitudinal hope that I advocate because he believes blind will motivates action, and we are all better off dead.

Still, Schopenhauer’s philosophy presents a great challenge for those who want to hope.

March 20, 2017

Summary of Marshall Brain’s “Robotic Nation”

There has been much recent discussion about the effect of technology on employment. With this in mind, I reprint a post from 3 years ago based on Marshall Brain‘s prescient essays of more than 15 years ago.1

Robotic Nation

Overall Summary

The Tip of the Iceberg – We now see technology’s impact on employment because of

Moore’s Law – Exponential growth is leading to a

The New Employment Landscape – where the equation

Labor = Money – will no longer hold, necessitating new economic models.

The tip of the Iceberg – Brain believes every fast food meal will be (almost) fully automated within a few years, and this is just the tip of the iceberg. Right now we interact with automated systems: ATM machines, gas pumps, self-serve checkout, etc. These systems lower cost and prices, but “these systems will also eliminate jobs in massive numbers.” There will be massive unemployment in the next decades as we enter the robotic revolution.

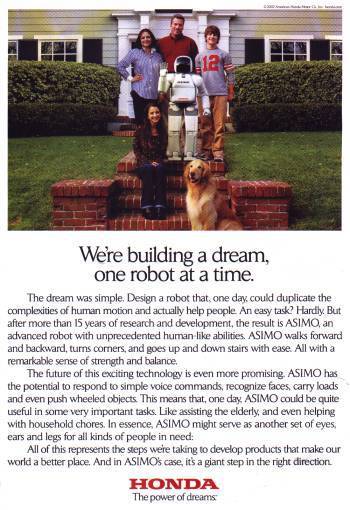

A feasible scenario suggests that in the next fifteen years most retail transactions will be automated and 5 million retail jobs lost. Next, walking, human shaped robots will begin to appear–Honda’s Asimo is an early example. By 2025 we may have machines that hear, move, see, and manipulate objects with roughly the ability of humans. These machines will be equipped with AI systems, making them seem humanlike. Robots will get cheaper and become more human shaped to easily facilitate their use of cars, elevators, and other objects in the human environment. By 2030 you will buy a $10,000 robot that will clean, vacuum, mop, sweep, mow grass, etc. These robots would last for years, need no vacation or sick time, and eliminate human jobs. Robotic fast food places will open shortly thereafter and by 2040 will be completely robotic. By 2055 robots will replace half the American workforce leaving millions unemployed. Restaurants, construction, airports, hospitals, malls, amusement parks, truck drivers and airplane pilots are just some of the jobs and locations that will have mostly robotic workers.

While robotic vision or image processing is currently a stumbling block, Brain thinks we will make significant progress in this field in the next twenty years. This single improvement will yield catastrophic changes, just as the Wright brothers breakthrough brought about aviation. Brain applauds these developments. After all, who wants to clean toilets, flip burgers, and drive trucks? “These activities represent a massive waste of human potential.”

If all this sounds crazy, Brain asks you to consider a prediction of faster than sound aircraft in 1900; a time when there were no radios, model T’s or airplanes. Then many thought heavier than air flight was impossible, and one who predicted it was often ridiculed. Such considerations lead to the conclusion that the employment world will change dramatically over the next fifty years. Why? The fundamental answer is Moore’s Law, that CPU power doubles every 18 to 24 months. Computers in 2020 will have the power of the NEC Earth Simulator. By 2100 we may have the power of a million human brains on our desktop. Robots will take your job by 2050 with the marriage of: a cheap computer with the power of a human brain; a robotic chassis like Asimo; a fuel cell; and advanced software.

While the employment landscape is not so different from the one of 100 years ago, it will be vastly different once robots that see, hear, and understand language compete with humans for jobs. The 50 million jobs in fast food, delivery, retail, hotels, restaurants, airports, factories, construction will be lost in the next fifty years. But America can’t deal with 50 million unemployed. And the economy will not create 50 million new jobs. Why?

In the current economy people trade labor for money. But without enough work people wont’ be able to earn money. What then? Brain thinks we might erect housing for the unemployed since you can’t live without a job, and we need to have a guaranteed income. But whatever we do, we had better start thinking about the kind of societal structures needed in a “robotic nation.”

Robots in 2015

Overall Summary

We Will Replace all the Pilots – and then

Robots in Retail – but we won’t

Create New Jobs – which means there will be

A Race to the Bottom – so

Where Do We Want to Go?

If you went back to 1950 you would find people doing most of the work just like they do in 2000. (Except for ATM machines, robots on the auto assembly line, automated voice answering systems, etc.) But we are on the edge of the robotic nation and half the jobs will be automated in the near future. Robots will be popular because they save money. For example, if an airline replaces expensive pilots, the money saved will give them a competitive advantage over other airlines. We’ll feel sorry for the pilots at first, but forget about them when the savings are passed on to us. Next will be the retail jobs and then others will follow. What about new job creation? After all, the model T created an automotive industry. Won’t the robotic industry do the same? No. Robots will assemble robots and engineering and sales jobs will go to those willing to work for less.

The robotic nation will have lots of jobs—for robots! Our economy does not create many high paying jobs. (And for those there is intense competition.) Instead there is a “race to the bottom.” A race to pay lower wages and benefits to workers and, if technologically feasible, to eliminate them altogether. Robots will make the minimum wage—which has declined in real dollars for the last forty years—irrelevant; there will be no high paying jobs to replace the lost low-paying ones. So where do we want to go? We are on the brink of massive unemployment unknown in American history, and everyone will suffer because of it. We need to answer a fundamental question: How do we want the robotic economy to work for the citizens of this nation?

Robotic Freedom

Overall Summary

The Concentration of Wealth – is accelerating bringing about

A Question of Freedom – why not let us be free to create

Harry Potter and the Economy – which leads us to

Stating the Goals – increase human freedom by weaning away from unfulfilling labor by

Capitalism Supersized – economic system that provides for all people which has

The Advantages of Economic Security – better for everyone because

You, Personally, and the Robots – because even your job is vulnerable.

We are on the leading edge of a robotic revolution that is beginning with automated checkout lanes; the pace of this change will accelerate in our lifetimes. Furthermore, the economy will not absorb all these unemployed. So what can we do to adapt to the catastrophic changes that the robotic nation will bring?

People are crucial to the economy. But increasingly there is a concentration of wealth in the hands of a few–the rich make more money and the workers make less. With the arrival of robots, all the income of corporations will go to the shareholders and executives. But this automation of labor—robots will do almost all the work 100 years from now—should allow people to be more creative than ever. Can we design the economy to do this? Why not design an economy where we abandon the “work or don’t eat” philosophy?

This is a question of freedom. Consider J.K. Rowling, author of the Harry Potter books. Amazingly she wrote them while on welfare and would not have done so without public support. Think how much human potential we lose because people have to work to eat. How much music, art, science, literature, and technology have never been created because people had to work. Consider that Linux, one of the world’s best operating systems, was created by people in their spare time. Why not create an economic model that encourages this kind of productivity? Why not create an economic model where we don’t have to hope the aged die before they collect too much social security, where we don’t have so many working poor, or people sleeping in the streets? Brain says “we are entering an historic era that has the potential to completely change the human condition.”

Brain argues that we shouldn’t ban robots because that leads to economic stagnation and lots of toilet cleaning. Instead he states the goals: raise the minimum wage; reduce the work week; and increase welfare systems to deal with unemployment. What is needed is a complete re-thinking of economic goals. The primary goal of the economy should be to increase human freedom. We can do this by using robotic workers to free people to: choose the products; start the businesses, creative projects; and use their free time as they see fit. We need not be slaves to the sixty hour work week “the antithesis of freedom.”

The remainder of the article offers specific suggestions (supersize capitalism, guaranteed economic security) of how we would fund a society in which persons actualize their potential to create art, literature, science, music, etc. without the burden of wage slavery. The advantages of such a system would be significant. (If all this seems fanciful, consider how fanciful our world would be to the slaves and serfs that most humans have been throughout history.) Brain says we are all vulnerable to the coming robotic nation.Let us then rethink our world, and welcome the robotic workers who will give us the time and the the freedom we all so desperately desire.

“Robotic Nation FAQ”

Question 1 – Why did you write these articles? What is your goal? Answer – Robots will take over half the jobs by 2030 and this will have disastrous consequences for rich and poor alike. No one wants this. I’d like to plan ahead.

Question 2 – You are suggesting that the switchover to robots will happen quickly, over the course of just 20 to 30 years. Why do you think it will happen so fast? Answer – Consider the analogy to the auto or computer revolutions. Once things get going, they proceed rapidly. Vision, CPU power, and memory are currently holding robots back—this will change. Robots will work better and faster than humans by 2030-2040.

Question 3 – In the past technological innovation created more jobs, not less. When horse-drawn plows were replaced by the tractor, security guards by the burglar alarm, craftsman making things by factories making them, human calculators by computers, etc., it improved productivity and increased everyone’s standard of living. Why do you think that robots will create massive unemployment and other economic problems? Answer – First, no previous technology replaced 50% of the labor pool. Second, robotics won’t create new jobs. The work created by robots will be done by robots. Third, we are creating a second intelligent species which competes with humans for jobs. As this new species gets better, it will do more of our work. Fourth, past increases in productivity meant more pay and less work but today worker wages are stagnant. Now productivity gains result in concentration of wealth. This may work itself out in the long run, but in the short run it is devastating.

Question 4 – There is no evidence for what you are saying, no economic foundation for your proposals. Answer – Just Google ‘jobless recovery,’” for the evidence. Automation fuels production increases but does not create new jobs.

Question 5 – What you are describing is socialism. Why are you a socialist/communist? Answer – I am a capitalist who has started three successful businesses and written a dozen books. “I am all for free markets, innovation and investment.” Socialism is the view that producing and distributing goods is done collectively by centralized governmental planning. He argues that individuals should own the means of producing and be free “to earn whatever they can with their products, services, and innovations.” By giving consumers a share of the wealth–which they won’t be able to earn with work–we will “enhance capitalism by creating a large, consistent river of consumer spending. It is also a way of providing economic security to every citizen…” Communism is usually identified by the loss of freedom and choice, whereas he wants people to have “economic freedom for the first time in human history…”

Question 6 – Why do you believe that a $25,000 per year stipend for every citizen is the solution to the problem? Answer – With robots doing all the work, we will finally have an opportunity to do this, which is better for everyone.

Question 7 – Won’t your proposals cause inflation? Answer – Tax rebates, similar to his proposals, don’t cause inflation. Neither do taxes, social security or other programs that re-distribute wealth.

Question 7a – OK, maybe it won’t cause inflation. But there is no way to give everyone $25,000 per year. The GDP is only $10 trillion. Answer – Brain argues that we should do this gradually. Remember $150 billion, about what the US spent on the Iraq war in 2003, is $500 for every man, woman, and child in the US. It isn’t that much in our economy. At the moment our government collects about $20,000 per household in taxes each year and so “it is very easy to imagine a system that pays US citizens $25,000 per year.”

Question 7b – Is $25,000 enough? Why not more? Answer – “As the economy grows, so should the stipend.”

Question 8 – Won’t robots bring dramatically lower prices? Everyone will be able to buy more stuff at lower prices. Answer – True. But current trends show that most of the wealth will end up in the hands of a few. Also, if you have no wealth it won’t matter that prices are lower. To let every citizen benefit from the robotic nation distribute the wealth to all.

Question 9 – Won’t a $25,000 per Year Stipend Create a Nation of Alcoholics? Answer – Brain notes this is a common question since many people assume that if we aren’t forced to due hard labor we’ll just do nothing or drink all day. He says he has no idea where this fear comes from (probably from political, philosophical, moral, and religious ideas promulgated by certain groups.) He dispels the idea with examples: a) he supports his wife who works at home; b) his in-laws are retired and live on a pension and social security; c) he has independently wealthy friends; d) he knows students supported by loans; and e) many are given free education and training. None of these people are lazy or alcoholics! (Perhaps its the reverse, with no possible source of income people give up.)

Question 9a – Yes, stay-at-home moms and retirees are not alcoholic parasites, but they are exceptions. They also are not productive members of the economy. Society will collapse if we do what you are talking about. Answer – Everyone participates in the economy by spending money. Unless there are people with money there’s no economy. The cycle of getting paid by a paycheck and spending it at businesses who get the money from customers is just that–a cycle—which will stop if people have no money. And giving a stipend won’t stop people from trying to make more money, create, invent or play. Some people will become alcoholics though, just as they do now, but Brain thinks we’ll have less lazy alcoholics “if we give them enough money to live decent, dignified lives…”

Question 10 – Why not let capitalism run itself? We should eliminate the minimum wage, welfare, child labor laws, the 40-hour work week, antitrust laws, etc. Answer – “…because of the power of economic coercion.” This economic power is why companies pay wages of a few dollars a week in most parts of the world. “We, The People, should enact the stipend to give ourselves true economic independence.”

Question 11 – Why didn’t you include the whole world in your proposals–why are you U.S. centric? Answer – Ideally, the global economy would adopt these proposals.

Question 12 – I love this idea. How are we going to make it happen? Answer – We should spread the word.

Thank you Marshall Brain for such an uplifting vision.

____________________________________________________________________

1. The articles in their entirety can be found here.

March 17, 2017

Summary of Schopenhauer’s Pessimism

I have written in some detail about Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860), who was a German philosopher known for his atheism and pessimism—in fact he is the most prominent pessimist in the entire western philosophical tradition. Schopenhauer’s most influential work, The World as Will and Representation, examines the role of humanity’s most basic motivation, which Schopenhauer called will. This will is an aimless striving which can never be fully satisfied, hence life is essentially dissatisfaction. Moreover consciousness makes the situation worse, as conscious beings experience pain when thinking about past regrets and future fears.

He concluded that desires cause suffering. Consequently, he favored asceticism—a lifestyle of negating desires or a denying the will similar to the teachings of Buddhism and Vedanta. In its most extreme form, asceticism leads to a voluntarily chosen death by starvation, the only form of suicide that is immune to moral critique.

Schopenhauer’s overall pessimism can be seen in his claims that:

(1) existence is a mistake;

(2) there is no meaning or purpose to existence;

(3) the best thing for humans is non-existence;

(4) life is essentially suffering and suffering is evil;

(6) this is the worst of all possible worlds.

Of course many, like Nietzsche, argued that Schopenhauer’s view of the world says more about him than it does about the world. Moreover, Nietzsche argued that Schopenhauer’s asceticism and denial of Will were self-defeating. For to will nothingness was still a willing. Schopenhauer was willing nothing, rather than not willing at all. Thus Nietzsche argued that Schopenhauer advocates a kind of “romantic pessimism.” Schopenhauer desired or willed nothing so as to achieve tranquility and peace. In contrast to Schopenhauer, Nietzsche adopted a philosophy that said yes to life, fully cognizant of the fact that life is mostly miserable, evil, ugly, and absurd.

March 14, 2017

Is Hope Bad?

Hope is the worst of evils, for it prolongs the torment of men. ~ Friedrich Nietzsche

For the past few weeks we investigated the concept of hope. In the process we have come to offer a spirited defense of hope and, to a lesser extent, optimism. I’d now like to “play the flip side,” as an old colleague used to say, and consider some critics of hope.

Kazantzakis’ Case Against Hope

I have previously expressed my affinity for the thought of the Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis (1883 – 1957). I have also discussed his case against hope in detail in, “Kazantzakis’ Epitaph: Rejecting Hope.” Here are a few highlights of his case against hope:

… leave the heart and the mind behind you, go forward … Free yourself from the simple complacency of the mind that thinks to put all things in order and hopes to subdue phenomena. Free yourself from the terror of the heart that seeks and hopes to find the essence of things. Conquer the last, the greatest temptation of all: Hope …

Why should we abandon hope according to Kazantzakis? Because we often lose hope and cease acting. Instead, we should seek and strive, even if our efforts are in vain. Don’t hope for good outcomes, or understanding, or meaning, he counsels, but ascend and move forward. We are tempted by hope, but the courageous live without it, carrying on in its absence. Kazantzakis describes his rejection of hope or optimism, in this passage from his autobiography, Report to Greco:

Nietzsche taught me to distrust every optimistic theory. I knew that [the human] heart has constant need of consolation, a need to which that super-shrewd sophist the mind is constantly ready to minister. I began to feel that every religion which promises to fulfill human desires is simply a refuge for the timid, and unworthy of a true man … We ought, therefore, to choose the most hopeless of world views, and if by chance we are deceiving ourselves and hope does exist, so much the better … in this way man’s soul will not be humiliated, and neither God nor the devil will ever be able to ridicule it by saying that it became intoxicated like a hashish-smoker and fashioned an imaginary paradise out of naiveté and cowardice—in order to cover the abyss. The faith most devoid of hope seemed to me not the truest, perhaps, but surely the most valorous. I considered the metaphysical hope an alluring bait which true men do not condescend to nibble …

Note – The hope that Kazantzakis rejects is metaphysical and forward-looking, and I too reject such hopes. And he want us to act, which I argue is the essence of hope. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Nietzsche’s Pessimism

There are many great pessimists in the Western philosophical tradition—Voltaire, Rousseau, Schopenhauer, and others—but let’s focus on Nietzsche. He associates weak pessimism with Eastern renunciation; strong pessimism with Eastern notion of harmonizing contradictions; and Socratic optimism with Western philosophy’s emphasis on logic, beauty, goodness, and truth. For Nietzsche pessimism refers to the fact that reality is cruel, irrational, and always changing; while optimism is the view that reality is orderly, intelligible, and open to betterment. Optimists mistakenly believe that they can overcome the abyss and make the world better by action, but Nietzsche wants us to see reality realistically and be pessimists.

Yet Nietzsche doesn’t want us to be weak pessimists like the Buddha, who advises us to eliminate desires, or like Schopenhauer, who believes that in resignation from striving we find freedom. Instead, Nietzsche wants us to be strong pessimists who affirm life rather than renounce it, who fill life with their enthusiasm, and who take pleasure in what is hard and terrible. Salvation and freedom come from accepting the contradictory and destructive nature of reality, and responding with joyous affirmation.

In other words, Nietzsche’s response to the tragedy of life is neither resignation nor self-denial, but a life-affirming pessimism. He sees Socratic philosophy and most religion as an optimistic refuge for those who will not accept the tragic sense of life. But he also rejects Schopenhauer’s pessimism and nihilism. Nietzsche’s pessimism says yes to life. He counsels us to embrace life and suffer joyfully.

Note – Nietzsche’s thoughts are consistent with Kazantzakis’ and my own. He rejects both resignation and a hope which includes expectations. Instead, he calls us to action, as do I. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Stoicism

While Michael and Caldwell use Stoicism to defend caring without lamentation, a view that they argue is consistent with optimism, most interpret the Stoics differently. For example, consider how the Stoics address the issue of anxiety. When you are anxious, most people try to cheer you up by telling you things will be ok. But the Stoics hate consolation meant to give hope—the opiate of the emotions. They believe that we must eliminate hope to find inner peace because hoping for the best makes things worse when your hopes are dashed, as they inevitably will be. Instead, they advise that we tell ourselves that things will get worse because, when we envision the worst, we will discover that we can manage it. And if things get too bad, the Stoics remind us that we can always commit suicide.

Or consider the Stoics on anger. Anger comes when misplaced hopes smash into unforeseen reality. We get mad, not at every bad thing, but at bad, unexpected things. So we should expect bad things—not hope they don’t occur—and then we won’t be angry when things go wrong. Wisdom is reaching a state where no expected or unexpected tragedy disturbs our inner peace, so again we do best without hope. Still this doesn’t imply total resignation to our fate; there are still some things we might be able to change.

Finally consider this quote from Seneca who relates hope to fear

[t]hey are bound up with one another, unconnected as they may seem. Widely different though they are, the two of them march in unison like a prisoner and the escort he is handcuffed to. Fear keeps pace with hope. Nor does their so moving together surprise me; both belong to a mind in suspense, to a mind in a state of anxiety through looking into the future. Both are mainly due to projecting our thoughts far ahead of us instead of adapting ourselves to the present. (Seneca, Letter 5.7–8; in: 1969: 38)

Note – The stoics reject hope as expectation, lamentation, and consolation; not hope as action. Thus nothing they say here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Simon Critchley’s Case Against Hope

Simon Critchley, chair and professor of philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York City, recently penned this piece in the New York Times: “Abandon (Nearly) All Hope.” In it he defends a theme similar to the one he argued for in his book, Very Little … Almost Nothing … [image error](I reviewed the book on this blog.) Critchley regards hope as another redemptive narrative, or perhaps as an element in all redemptive narratives. Instead of succumbing to the temptation of hope, he suggests we be realistic and brave—a view reminiscent of the one held by Nietzsche and Kazantzakis.

Critchley begins by asking: “Is it [hope] not rather a form of moral cowardice that allows us to escape from reality and prolong human suffering?” If hope is escapism or wishful thinking, if it is blind to reality or contrary to all evidence, then it is a form of moral cowardice?

To elucidate these ideas Critchley recalls Thucydides’ story of the Greeks’ ultimatum to the Melians—surrender or die. Rather than submit, the Melians hoped for reprieve from their allies or their gods, despite the evidence that such hopes were misplaced. The reprieve never come, and all the Melians were either killed or enslaved. In such situations Critchley counsels, not hope, but courageous realism. False hopes will seal our doom as they did the Milians.

From such considerations Critchley concludes: “You can have all kinds of reasonable hopes … But unless those hopes are realistic we will end up in a blindly hopeful (and therefore hopeless) idealism … Often, by clinging to hope, we make the suffering worse.”

Note – I too reject false hopes, but Critchley admits you can have reasonable hopes. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Oliver Burkeman on Hope as Deception

In a recent column in the Guardian, Oliver Burkeman argued that what is often called hope is really deception—hoping for things which are virtually impossible. For example, hoping that one wins the lottery, or that the victims of an accident have survived when their deaths are near certainties.

By contrast, letting go of hope often sets us free. To support this claim he refers to “recent research … suggesting that hope makes people feel worse.” For instance: the unemployed who hope to find work are less happy than those who accept they won’t work again; those in the state of hoping for a miraculous cure for a terminal disease are less happy than those who accept that they will die; and people more often act for change when they stop hoping that others will do so. Perhaps there is something about giving up hope and accepting reality that is comforting.

Note – I too reject hope with expectations. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

My Reflections

The common theme in these critiques is the futility of false hopes, which lead inevitably to disappointment. I agree. If I hope to become the world’s most famous author or greatest tennis player, my expectations are bound to be dashed. Silly to hope for such things. Much better to hope that I enjoy writing and tennis despite my shortcomings in both.

For instance, when confronted by the reality of the concentrations camps, Victor Frankl didn’t hope to dig his way out of his prison. That wasn’t impossible. Instead, he hoped that the war would end and he might be freed. That was realistic. Thus the difference between false and realistic hope. The former is delusional, the latter worthwhile. Sometimes only fools keep believing; sometimes you should stop believing. False hopes prolong misery.

But I want to know if I’m justified in hoping (without expectation) that life has meaning or that truth, beauty and goodness matter. And I think I am. Why? Because regarding questions about the ultimate purpose of the ourselves and the cosmos, we just don’t know enough to say that hope is unjustified. It is reasonable to think that life might have meaning, it is not impossible that it does. Thus this is not a false hope, even if the object of my hopes may not be fulfilled.

Thus we can legitimately hope that life is meaningful without being moral cowards. Of course life may be pointless and meaningless. We just don’t know. But if we bravely accept that we just don’t know whether life is meaningful or not, then we live with moral and intellectual integrity. And there is no more honest or better way to live.

March 11, 2017

Hope and Pandora’s Box

In Greek mythology, Pandora was the first human woman created by the gods. Zeus ordered Hephaestus to mold her out of earth as part of the punishment of humanity for Prometheus‘ theft of the secret of fire. According to the myth Pandora opened a jar, in modern accounts often mistranslated as “Pandora’s box,” releasing all the evils of humanity such as pain and suffering, leaving only hope inside once she had closed it again. (Most scholars translate the Greek word elpis as “expectation.”) The Pandora myth is a kind of theodicy—an attempt to explain why there is evil in the world.

The key question is how to interpret the myth. Is the imprisonment of hope inside the jar a benefit for humanity, or a further bane? If hope is another evil, then we should be thankful that hope was withheld. The idea is that by hoping for or expecting a good life we can never have, we prolong our torment. Thus it is better to live without hope, and it is good that hope remained in the jar. But if hope is somehow good, then its imprisonment makes life even more dreary and insufferable. All the evils were scattered from the jar, while the one potentially mitigating force, hope, remains locked inside. Of course this makes us wonder why this good hope is in the jar of evils. To this question I have no answer.

But I do have another interpretation. Perhaps hope is good and it is good that it remained in the jar. In other words, the jar originally served as a prison for the evils, but thereafter it serves as a residence for this good hope. It’s as if hope, separated from evil, takes on a new character—it becomes good. But had hope been released into the world with the other evils, it would have been another evil, a bad kind of hope.

My interpretation depends on understanding hope, not as an expectation, but as an attitude that leads us to act rather than despair. This is the good kind of hope preserved in the jar. To better understand my interpretation, remember the words of Aeschylus from his tragedy, Prometheus Bound. Prometheus’ two great gifts to humanity are hope and fire. Hope aids our struggle for a better future while fire, the source of technology, makes success in that struggle possible. Hope is the first gift that Aeschylus mentions.

Chorus: Did you perhaps go further than you have told us?

Prometheus – I stopped mortals from foreseeing their fate.

Chorus – What kind of cure did you discover for this sickness?

Prometheus – I established in them blind hopes.

Chorus – This is a great benefit you gave to men.

March 8, 2017

In Hope Lies All Possibilities

For the last few weeks I have been writing about the concept of hope. I recently found an insight from the work of my graduate school mentor and dissertation director Richard J. Blackwell. I have written previously about the profound effect that Professor Blackwell had on my philosophical development.

The January 1999 edition of the philosophical journal, The Modern Schoolman, was titled: “Philosophy and Modern Science: Papers Presented in Honor of Richard J. Blackwell.” The introduction of that work was penned by Professor Richard Dees, now of the University of Rochester. Dees begins thus:

The articles gathered here honor the legacy of Richard J. Blackwell, a dedicated scholar, a consummate colleague, and above all, a much-loved and much-revered teacher … During his tenure, he has directed a program in the history and philosophy of science, written five books on topics ranging from the logic of discovery to his now-famous work on Galileo, translated four other books of historical significance, held the Danforth Chair in Humanities, won the Nancy McNair Ring Outstanding Teacher Award, directed over 30 dissertations, and guided literally hundreds of students.

After describing Blackwell’s many philosophical projects, and introducing the articles written in his honor by the distinguished scholars, Dees summarizes Blackwell’s conclusions about the Galileo affair—the work for which he became most well-known. And it was in the concluding paragraph that I found a pearl of wisdom. Dees writes:

So, for Blackwell, the real lesson of the Galileo Affair is … what it shows us about our own intellectual enterprises. When a standpoint becomes over-intellectualized, it becomes so rigid that no changes are possible without destroying the view itself. In the seventeenth-century, that danger lay primarily in the system-building philosophy that dominated the Catholic Church and the intellectual climate of Europe … The … question is whether the Catholic Church—or any organized religion—can open up its inquiries into the nature of reality in the same way that science has. Blackwell thinks that such a change is possible, but not without reconceptualizing the very structure of traditional Christian thought. As long as faith is considered the key virtue, any religion can fall too easily into dogmatism. Instead, he suggests, hope should be the center of our thought, for in hope lies all possibilities. (emphasis mine)

I believe that Professor Dees describes Blackwell’s overall philosophical attitude perfectly. And since I’m fortunate to still correspond with Professor Blackwell, I can say that he has maintained a positive, optimistic, or hopeful attitude despite age, pain and infirmity. I am fortunate to have known Professor Blackwell. And I’d like to thank Professor Dees for his clear and eloquent prose.

March 6, 2017

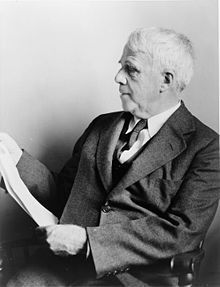

Robert Frost: Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening

The first poem I ever committed to memory was Robert Frost’s, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening. I first encountered the poem as a sophomore in high school almost 50 years ago, and I remember being moved by my teacher’s vocal rendition. My mind can still sees that classroom where I first heard the poem, but I didn’t know then that I would still remember the poem so many years later. Now I have less miles to go now than I did in my youth, and the “dark and deep” are beginning to look lovelier.

Robert Frost (1874 – 1963) was an American poet who is highly regarded for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech.[2] One of the most popular and critically respected American poets of the twentieth century,[3] Frost was honored frequently during his lifetime, receiving four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America’s rare “public literary figures, almost an artistic institution.”[3] He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960, and he read his poem “The Gift Outright” at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy on January 20, 1961.

I have always enjoyed that the poem rhymes, as I generally find free verse harder to digest. As Frost famously remarked free verse was like “playing tennis without a net.” The poem is written in iambic tetrameter in the Rubaiyat stanza created by Edward Fitzgerald. Overall, the rhyme scheme is AABA-BBCB-CCDC-DDDD.[3] Frost himself called the poem “my best bid for remembrance”.[1]

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

March 3, 2017

Summary of Victor Frankl on “Tragic Optimism”

Viktor Emil Frankl M.D., PhD. (1905 – 1997) was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist as well as a Holocaust survivor. Frankl was the founder of logotherapy, a form of Existential Analysis, and the best-selling author of Man’s Search for Meaning, which has sold over 12 million copies. According to a survey conducted by the Library of Congress and the Book-of-the-Month Club, it is one of “the ten most influential books in America.” (I have taught out of the book in many universities classes, and it is one of my favorite books. I have summarized it here.)

The postscript to the book, “Tragic Optimism,” was added in 1984 and is based on a lecture Frankl presented at the Third World Congress of Logotherapy, Regensburg University, West Germany, June 1983. Here are its main ideas.

Frankl begins like this:

“Let us first ask ourselves what should be understood by “a tragic optimism.” In brief it means that one is, and remains, optimistic in spite of the “tragic triad,” … a triad which consists of … (1) pain; (2) guilt; and (3) death. This … raises the question, How is it possible to say yes to life in spite of all that? How … can life retain its potential meaning in spite of its tragic aspects? After all, “saying yes to life in spite of everything,” …presupposes that life is potentially meaningful under any conditions, even those which are most miserable. And this in turn presupposes the human capacity to creatively turn life’s negative aspects into something positive or constructive. In other words, what matters is to make the best of any given situation. … hence the reason I speak of a tragic optimism … an optimism in the face of tragedy and in view of the human potential which at its best always allows for: (1) turning suffering into a human achievement and accomplishment; (2) deriving from guilt the opportunity to change oneself for the better; and (3) deriving from life’s transitoriness an incentive to take responsible action.

Of course you can’t force someone to be optimistic, anymore than you can force them to be happy. Rather, you need a reason to be happy, just like you need a reason to laugh or smile. Give someone a reason to happy or laugh or smile and they will. Try to force them to and they will have fake happiness or forced laughter or an unnatural smile.

Real happiness comes when we find meaning in our lives—meaning provides the reason to be happy despite the tragic triad. Without meaning, we give up. And this meaninglessness often lies behind our experiences of: 1) depression; 2) aggression; and 3) addiction. Now we can trace many neurosis to biochemical conditions, but Frankl found that often their origins derive from a sense of meaninglessness.

As a therapist, Frankl was “concerned with the potential meaning inherent and dormant in all the single situations one has to face throughout his or her life,” rather than trying to understand the meaning of a life as a whole. He was not suggesting there is no meaning to an entire human life, but that this final meaning depends “on whether or not the potential meaning of each single situation has been actualized …” In other words: “the perception of meaning … boils down to becoming aware of a possibility against the background of reality or … becoming aware of what can be done about a given situation.”

But how do we find meaning in our lives? Frankl reiterates that there are three main sources of meaning in life: 1) creating a work or doing a deed; 2) experiencing something or encountering someone (as in love); and 3) transcending, learning, and finding meaning from the inevitable suffering which we will experience. Frankl also argues that we can find meaning despite the tragic triad of suffering, guilt, and death.

As for suffering, Frankl doesn’t claiming that we must suffer to discover meaning, but that meaning can be found despite, or even because of, suffering. Here he reminds me of the Stoics: “If it [suffering] is avoidable, the meaningful thing to do is to remove its cause, for unnecessary suffering is masochistic rather than heroic. If, on the other hand, one cannot change a situation that causes his suffering, he can still choose his attitude.” We might not have chosen to break our necks, but we can choose to not let that experience break us. As for guilt, we overcome it primarily by taking responsibility for our actions, rising above guilt, and transforming ourselves for the better .

As for death, the ephemeral nature of life should remind us how we are dying every moment, and thus should make good use of our time. This leads to Frankl’s imperative: “Live as if you were living for the second time and had acted as wrongly the first time as you are about to act now.” In other words, live your life as if you were getting a second chance to correct all the mistakes you made in your first life. Frankl’s ruminations on the irreversibility of our lives always moves me deeply:

… as soon as we have used an opportunity and have actualized a potential meaning, we have done so once and for all. We have rescued it into the past wherein it has been safely delivered and deposited. In the past, nothing is irretrievably lost, but rather, on the contrary, everything is irrevocably stored and treasured. To be sure, people tend to see only the stubble fields of transitoriness but overlook and forget the full granaries of the past into which they have brought the harvest of their lives: the deeds done, the loves loved, and last but not least, the sufferings they have gone through with courage and dignity.

Surprisingly these considerations lead him to this profound thought about aging:

From this one may see that there is no reason to pity old people. Instead, young people should envy them. It is true that the old have no opportunities, no possibilities in the future. But they have more than that. Instead of possibilities in the future, they have realities in the past—the potentialities they have actualized, the meanings they have fulfilled, the values they have realized—and nothing and nobody can ever remove these assets from the past.

Frankl says that society mistakenly adores the usefulness of achievement, success, happiness and youth. However, the quest for meaning is the most worthwhile pursuit, and the only way to true happiness. Life’s tragedies—pain, guilt, and death—may lead to meaninglessness, but they don’t have to. For we can be optimistic. We can find meaning through our work, our relationships, and by nobly bearing our suffering.

March 1, 2017

Doug Muder on Hope

At times our light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.

~ Albert Schweitzer

Hope is like peace. It is not a gift from God. It is a gift that only we can give to one another. ~ Elie Wiesel

The retired mathematics professor Doug Muder writes a great political blog, The Weekly Sift. Recently he has addressed the question of hope, primarily in response to the political situation in America today. Here are brief summaries of his thoughts about hope.

In “Hope, True and False,” Muder writes that we often feel hopeless and helpless about, for example, political issues like gun violence or campaign finance reform. We don’t think we can win these battles, and we just give up. Muder points out that many struggles for justice initially appear hopeless, but that things change after people commit to changing them.

Such change is often aided by optimistic beliefs—that your god or your friends are on your side; that truth will eventually win out; or that there is moral progress. Such optimism often strengthens your resolve. And though you are often defeated, Muder recommends fighting for justice anyway. Our efforts express our nature and, if we have comrades in our struggles, so much the better. He concludes:

As I said before, that’s not a perfect answer. I don’t promise that it will hold up against every horrible series of events that could possibly happen to a person. But fortunately, none of us needs to stay strong through every horrible thing that could ever happen. Each of us only needs enough resilience to complete the journey of our own lifetime. So I want to close by wishing you good luck on that journey, and reminding you to take care of each other.

Summary – We should struggle for truth and justice because we might succeed, and we both express ourselves and enjoy an affinity with others when we work for justice.

In “Season of Darkness, Season of Hope,” Muder begins by distinguishing hope from optimism. Muder defines optimism as “Believing that things will improve …” and its opposite, pessimism, as “the belief that things will get worse.” He then notes that “the opposite of hope is something far more devastating than pessimism, it’s despair. To be in despair is to believe that it’s useless to try, because your actions don’t matter.” And this leads him to conclude that: “Optimism and pessimism are beliefs about the future. Hope and despair are attitudes towards the present.”

For example, when thinking about a future exam, an optimist thinks she’ll probably pass while a pessimist thinks she’ll probably fail, but both take the exam. On the contrary, in the midst of despair a person won’t even take the test. After all, what’s the point if you are going to fail anyway? However, hope is the opposite:

Hope is that feeling deep within you that you are alive, and that in this particular time and place, the only thing you need to concern yourself with is what you do next. Hope means refusing to prejudge the situation, it means doing whatever you can think to do and then whatever happens will happen … [and] hope … focuses on those parts of the future that remain undetermined, and it says, “Let me see what I can do.”

So hope is about acting in the face of the unknown; about rejecting despair; about not giving up; about caring for justice and believing in the potential for human goodness. We can’t know if our actions will bring about a better world, and what we do will always seem inadequate, but, “Here, in a time of darkness, we choose to act, but we do not know what will come from that action. We cannot know. And so, we hope.”

Summary – Hope is an attitude, in the present, which rejects despair and encourages action.

In “The Hope of a Humanist,” Muder wonders: What do we do when we lose hope?

In answer to this question, religion tells us to come back to god or believe in an afterlife, but these answers only work for the devout. Humanists might comfort themselves with a belief in progress, but we can’t be sure things will progress, or that our species will survive. And, even if the long-term trends are good, that provides little comfort now. So Muder rejects both a god and progress as reasons to be hopeful.

Why then be hopeful? “I see hope as an experience in the moment, the feeling that it is worthwhile to try. It’s worthwhile to get out of bed in the morning.” For Muder, hope expresses itself in the joy we take in doing things—like playing games or solving puzzles—even if they are objectively pointless. We do these things “just to experience the sense of striving, not to produce something for the future.” So he sees “hope as that pure feeling of let’s-do-this.” He concludes:

If you have had or are having a crisis of hope … Don’t get distracted into debates about optimism and pessimism. Some people believe in God and some don’t. Some people are optimists and some are pessimists. But any of them can learn to live hopefully in the present … it’s always better to live in hope than to live in despair.

Final Summary – We should struggle for truth and justice because we might succeed, and we both express ourselves and enjoy an affinity with others when we work for justice. Hope is an attitude which rejects despair and manifests itself in an active striving. And it is good for us. Muder’s ideas about hope closely correspond to those expressed in this previous post.

Doug Muder on Hope

At times our light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.

~ Albert Schweitzer

Hope is like peace. It is not a gift from God. It is a gift that only we can give to one another. ~ Elie Wiesel

The retired mathematics professor Doug Muder writes a great political blog, The Weekly Sift. Recently he has addressed the question of hope, primarily in response to the political situation in America today. Here are brief summaries of his thoughts about hope.

In “Hope, True and False,” Muder writes that we often feel hopeless and helpless about, for example, political issues like gun violence or campaign finance reform. We don’t think we can win these battles, and we just give up. Muder points out that many struggles for justice initially appear hopeless, but that things change after people commit to changing them.

Such change is often aided by optimistic beliefs—that your god or your friends are on your side; that truth will eventually win out; or that there is moral progress. Such optimism often strengthens your resolve. And though you are often defeated, Muder recommends fighting for justice anyway. Our efforts express our nature and, if we have comrades in our struggles, so much the better. He concludes:

As I said before, that’s not a perfect answer. I don’t promise that it will hold up against every horrible series of events that could possibly happen to a person. But fortunately, none of us needs to stay strong through every horrible thing that could ever happen. Each of us only needs enough resilience to complete the journey of our own lifetime. So I want to close by wishing you good luck on that journey, and reminding you to take care of each other.

Summary – We should struggle for truth and justice because we might succeed, and we both express ourselves and enjoy an affinity with others when we work for justice.

In “Season of Darkness, Season of Hope,” Muder begins by distinguishing hope from optimism. Muder defines optimism as “Believing that things will improve …” and its opposite, pessimism, as “the belief that things will get worse.” He then notes that “the opposite of hope is something far more devastating than pessimism, it’s despair. To be in despair is to believe that it’s useless to try, because your actions don’t matter.” And this leads him to conclude that: “Optimism and pessimism are beliefs about the future. Hope and despair are attitudes towards the present.”

For example, when thinking about a future exam, an optimist thinks she’ll probably pass while a pessimist thinks she’ll probably fail, but both take the exam. On the contrary, in the midst of despair a person won’t even take the test. After all, what’s the point if you are going to fail anyway? However, hope is the opposite:

Hope is that feeling deep within you that you are alive, and that in this particular time and place, the only thing you need to concern yourself with is what you do next. Hope means refusing to prejudge the situation, it means doing whatever you can think to do and then whatever happens will happen … [and] hope … focuses on those parts of the future that remain undetermined, and it says, “Let me see what I can do.”

So hope is about acting in the face of the unknown; about rejecting despair; about not giving up; about caring for justice and believing in the potential for human goodness. We can’t know if our actions will bring about a better world, and what we do will always seem inadequate, but, “Here, in a time of darkness, we choose to act, but we do not know what will come from that action. We cannot know. And so, we hope.”

Summary – Hope is an attitude, in the present, which rejects despair and encourages action.

In “The Hope of a Humanist,” Muder wonders: What do we do when we lose hope?

In answer to this question, religion tells us to come back to god or believe in an afterlife, but these answers only work for the devout. Humanists might comfort themselves with a belief in progress, but we can’t be sure things will progress, or that our species will survive. And, even if the long-term trends are good, that provides little comfort now. So Muder rejects both a god and progress as reasons to be hopeful.

Why then be hopeful? “I see hope as an experience in the moment, the feeling that it is worthwhile to try. It’s worthwhile to get out of bed in the morning.” For Muder, hope expresses itself in the joy we take in doing things—like playing games or solving puzzles—even if they are objectively pointless. We do these things “just to experience the sense of striving, not to produce something for the future.” So he sees “hope as that pure feeling of let’s-do-this.” He concludes:

If you have had or are having a crisis of hope … Don’t get distracted into debates about optimism and pessimism. Some people believe in God and some don’t. Some people are optimists and some are pessimists. But any of them can learn to live hopefully in the present … it’s always better to live in hope than to live in despair.

Final Summary – We should struggle for truth and justice because we might succeed, and we both express ourselves and enjoy an affinity with others when we work for justice. Hope is an attitude which rejects despair and manifests itself in an active striving. And it is good for us. Muder’s ideas about hope closely correspond to those expressed in this previous post.