John G. Messerly's Blog, page 84

February 2, 2017

Douthat’s “How Populism Stumbles” and Frum’s “How To Build An Autocracy”

(I keep intending to return to my existential concerns about the meaning of life, but the troublesome situation in my home country keeps bringing me back to politics.)

In today’s New York Times conservative columnist Ross Douthat penned, “How Populism Stumbles.” Douthat argues that movements like Trumps fail because of bigotry, extremism and, especially, hubris. Thus Douthat dismisses my worries about authoritarianism:

The great fear among Trump-fearers is that he will deal with this elite opposition by effectively crushing it—purging the deep state, taming the media, remaking the judiciary as his pawn, and routing or co-opting the Democrats. This is the scenario where a surging populism, its progress balked through normal channels, turns authoritarian and dictatorial …

Douthat tries to assuage our fears of autocracy noting that “nothing about Trumpian populism to date suggests that it has either the political skill or the popularity required to grind its opposition down.” This theme echoes those of another conservative New York Times columnist, David Brooks. In “The Internal Invasion,” he says, “Some on the left worry that we are seeing the rise of fascism, a new authoritarian age. That gets things exactly backward. The real fear in the Trump era should be that everything will become disorganized, chaotic, degenerate, clownish and incompetent.”

I hope that Douthat and Brooks are right—that we should worry more about incompetence than autocracy, although I have argued the opposite in multiple essays. I’m no expert on the competence necessary for the successful implementation of autocratic rule, but intuitively I doubt that it takes much. With power, and compliant, fearful subordinates, descent into all manners of fascism and violence is plausible—history books and nightly television provide ample evidence of this claim. Moreover, incompetence and authoritarian rule aren’t mutually exclusive.

Now, in the latest issue of The Atlantic, former President George W. Bush speechwriter David Frum describes a darker future in his essay, “How To Build An Autocracy.” Frum, a conservative, writes one of the most important and perceptive pieces I’ve read about our frightening times. He points out, among other things, that constitutional government “is founded upon the shared belief that the most fundamental commitment of the political system is to the rules.” That’s why Clinton conceded despite winning millions more votes, and California accepts the outcome despite rejecting Trump “by an almost two-to-one margin.”

Frum asks conservative ideologues, who are tempted to disregard the rule of the law in order to pursue their self-interest, to temper their enthusiasm for their newfound power. In a powerful paragraph that distills the essence of the situation that Republicans find themselves in, he tries to awaken their conscience:

Perhaps the words of a founding father of modern conservatism, Barry Goldwater, offer guidance. “If I should later be attacked for neglecting my constituents’ ‘interests,’ ” Goldwater wrote in, The Conscience of a Conservative[image error], “I shall reply that I was informed their main interest is liberty and that in that cause I am doing the very best I can.” These words should be kept in mind by those conservatives who think a tax cut or health-care reform a sufficient reward for enabling the slow rot of constitutional government.

He also points out that Trump wants to subvert precisely those institutions that “protect the electorate from its momentary impulses toward arbitrary action: the courts, the professional officer corps of the armed forces, the civil service, the Federal Reserve—and undergirding it all, the guarantees of the Constitution and especially the Bill of Rights.” To implement their plans Trump and his team count on public indifference. (That’s why, for example, they believe they can get away with not releasing Trump’s tax returns.) This means that what happens in the coming years will depend on whether Trump is right about political apathy. Yet, if people care enough, “they can restrain him.” Given our situation Frum exhorts us to:

Press your senators to ensure that prosecutors and judges are chosen for their independence—and that their independence is protected. Support laws to require the Treasury to release presidential tax returns if the president fails to do so voluntarily. Urge new laws to clarify that the Emoluments Clause applies to the president’s immediate family, and that it refers not merely to direct gifts from governments but to payments from government-affiliated enterprises as well. Demand an independent investigation by qualified professionals of the role of foreign intelligence services in the 2016 election—and the contacts, if any, between those services and American citizens. Express your support and sympathy for journalists attacked by social-media trolls, especially women in journalism, so often the preferred targets. Honor civil servants who are fired or forced to resign because they defied improper orders. Keep close watch for signs of the rise of a culture of official impunity, in which friends and supporters of power-holders are allowed to flout rules that bind everyone else.

Frum sees that the threat of totalitarianism is real, as do I. Perhaps conservatives like Brooks and Douthat dismiss the danger because it’s hard for them to admit that the side with which they’re partly allied has brought about frightening results. Then, to maintain cognitive equilibrium, they tell themselves that things won’t really get that bad because of the incompetence of Trump and his minions. Surely it couldn’t be that reactionary forces against modernity are the problem? Surely it couldn’t be that, independent of competence, the seeds are being sown for our future destruction? Surely it couldn’t be that we have been allied with the wrong side all along?

Of course, in Douthat’s and Brook’s defense, they have been ardent critics of Trump. For that they are to be praised. Still they are associated with a political party that is on the wrong side of history. (As is Frum, a conservative himself.) The way forward doesn’t demand the in-group loyalty and out-group hostility embedded in reptilian brains, nor does it necessitate a retreat to medieval institutions, social values, discredited economic theories, and a rejection of science. I’m not saying that Brooks and Douthat would disagree, but they often write as if they are enemies of the future.

Moreover, while the future is unknown, the vast majority of thinkers who have studied the issue agree with myself and Frum, the threat to the American republic is greater now than at any other time in our history, with the possible exception of the period leading up to and including the American civil war. Frum concludes his essay with a keen description, a dire warning, and a call to action. We should consider his thoughts carefully, and then act appropriately:

Those citizens who fantasize about defying tyranny from within fortified compounds have never understood how liberty is actually threatened in a modern bureaucratic state: not by diktat and violence, but by the slow, demoralizing process of corruption and deceit. And the way that liberty must be defended is not with amateur firearms, but with an unwearying insistence upon the honesty, integrity, and professionalism of American institutions and those who lead them. We are living through the most dangerous challenge to the free government of the United States that anyone alive has encountered. What happens next is up to you and me. Don’t be afraid. This moment of danger can also be your finest hour as a citizen and an American.

I would like to thank David Frum for his sagacious essay.

February 1, 2017

Review of Michael Moore’s: Where To Invade Next

Last night I watched, Where to Invade Next, a 2015 American documentary film written and directed by Michael Moore.[3][4] The film can be watched free with an amazon prime account, or rented for a few dollars here: Where to Invade Next; or purchased for a few more dollars here: Where To Invade Next[image error].

The film received positive reviews from critics. Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports that 78% of 169 reviews are positive, with an average rating of 6.7/10. The site’s consensus states: “Where to Invade Next finds documentarian Michael Moore approaching progressive politics with renewed — albeit unabashedly one-sided — vigor”.[15] On Metacritic, the film holds a 63/100 rating, based on 33 critics, indicating “generally favorable reviews”.[16]

I think it is Moore’s best film, managing to be solemn and humorous at the same time. My reaction was more somber. For me the film reveals, without explicitly saying it, how the toxic masculinity of American society, especially our propensity for violence and domination, leaves us bereft of community, compassion, and respect for human dignity. Social harmony and caring, juxtaposed with social dysfunction and aggressive competition, make the USA look horrific by comparison. Our cruelty and brutality are on full display and, compared with more civilized countries, American social policies are revealed for what they are—sheer madness.

In the film Moore visits (invades) various countries and claims some of their most successful ideas for the US. The idea is that rather than invade to destroy, we invade to learn how we could have a better and more just society.

Here are the countries he visits, and topics he considers, in order of appearance:

In Italy: labor rights and workers’ well-being – paid holiday, paid honeymoon, thirteenth salary, two-hour lunch breaks, paid parental leave, speaking with the executives of Lardini and Claudio Domenicali, the CEO of Ducati

In France: school meals and sex education

In Finland: education policy (almost no homework, no standardized testing), speaking with Krista Kiuru, the Finnish Minister of Education

In Slovenia: debt-free/tuition-free higher education, speaking with Ivan Svetlik, University of Ljubljana‘s rector, and Borut Pahor, the President of Slovenia

In Germany: labor rights and work–life balance, visiting pencil manufacturer Faber-Castell, and the value of honest, frank national history education particularly as it relates to Nazi Germany

In Portugal: May Day, drug policy of Portugal, and the abolition of the death penalty

In Norway: humane prison system, visiting the minimum-security Bastøy Prison and maximum-security Halden Prison, and Norway’s response to the 2011 Utøya attacks

In Tunisia: women’s rights, including reproductive health, access to abortion and their role in the Tunisian Revolution and the drafting of the Tunisian Constitution of 2014

In Iceland: women in power, speaking with Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, the world’s first democratically elected female president; the Best Party with Jón Gnarr being elected Mayor of Reykjavík City; the 2008–11 Icelandic financial crisis and the criminal investigation and prosecution of bankers, with special prosecutor Ólafur Hauksson

The fall of the Berlin Wall

No one could watch the film objectively, assuming they realized that everything Moore is saying is true, and restate that stale line “America is the greatest country.” In fact, one should draw nearly the opposite conclusion. I highly recommend the film.

January 30, 2017

Command and Control: Damascus Titan Missile Explosion

[image error][image error]Last night I viewed the new documentary film, Command and Control from director Robert Kenner. It was released January 10, 2017, and broadcast by PBS as part of its American Experience series. [11] The documentary is based on Eric Schlosser’s book, Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety[image error]. The book focused on the explosion, as well as other Broken Arrow incidents during the Cold War.[6][7] It was a finalist for the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for History.[10]

The Damascus Titan missile explosion refers to an incident where the liquid fuel in a LGM-25C Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile exploded at missile launch facility Launch Complex 374-7 in Van Buren County farmland just north of Damascus, Arkansas, on September 18–19, 1980. The initial explosion catapulted the 740-ton silo door away from the silo and ejected the second stage and warhead. Once clear of the silo, the second stage exploded. The W53 warhead landed about 100 feet (30 m) from the launch complex’s entry gate; its safety features operated correctly and prevented any loss of radioactive material.

However, we came frighteningly close to a nuclear catastrophe that night. Had the warhead detonated, millions of people would have either been killed outright or died shortly thereafter from the effects of the radioactive fallout.

The documentary is riveting, especially when your realize how many times we’ve had nuclear close calls, incidents that could start an unintended nuclear war, and nuclear accidents, incidents involving nuclear material that led to, or could have led to, events significant consequences to people, the environment or the facility. Examples include lethal effects to individuals, large radioactivity release to the environment, or reactor core melt.”[4]

The simple fact is that we have so far avoided more costly failures primarily because we’ve been lucky. It is also ironic how the having these weapons poses as much threat to those who have them as to those at whom they are aimed. It’s reminiscent of the idea that the more personal guns we have the safer we’ll be—which is self-evidently absurd and contradicted by all available evidence from societies around the world.

Of course superpowers with thousands of nuclear weapons find themselves in a version of the prisoner’s dilemma. Russia and the USA, who possess more than 90% of the world’s largest nuclear arsenals, find themselves in the following situation: If they both disarm they both do better, they can spend that money on their societies; if they both arm they both do worse, they must spend that money on nuclear weapons and face mutually assured destruction. But both fear that they will disarm and the other side won’t, which would allow the other side to dominate them.

In matrix form, where B = best; S = second best; T = third best; and W = worst; and the first outcome in each parenthesis is the USA outcome, and the second is Russia’s outcome, the situation looks like this:

Russia

Arm Disarm

Arm (T, T) (B, W)

USA

Disarm (W, B) (S, S)

It is easy to see here that both do better and neither does worse if they both disarm, but disarming without assurance that the other disarms risks being made a sucker. Still, if each can be assured that the other will comply with an agreement to disarm, both sides should. The alternative is the inevitable nuclear wars and accidents that will result.

All of this reminds me of reading Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth years ago, when he warned of the existential threat posed by nuclear weapons. Then, in today’s New York Times we read that ” Thanks to Trump, the Doomsday Clock Advances Toward Midnight.”

It is now two and one-half minutes to midnight. Our organization, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, is marking the 70th anniversary of its Doomsday Clock on Thursday by moving it 30 seconds closer to midnight. In 2016, the global security landscape darkened as the international community failed to come to grips with humanity’s most pressing threats: nuclear weapons and climate change.

There can be little doubt that humankind threatens their own existence. How things will turn out or whether there will be anyone left to read these or any other words is unknown. The chances for using these weapons, either on purpose or accidentally, is almost certain given sufficient time. And when you consider even more deadly technologies in the future, the situation is truly dire. As for me, I’m not optimistic.

January 29, 2017

One Million Views!

January 29, 2017

I started my blog in December 2013 and began to use site stats to record traffic in February 2014. Now, just less than three years later, I have passed 1,000,000 page views. It took me roughly two years to get my first half million views, and one year to get the next half million. So readership is picking up. To date I have published 661 posts. I do this work voluntarily, and social security provided my entire income—thanks FDR—so I’m not rich. But I am privileged to share my thoughts in the hope that some might benefit from them.

In addition to weekly posting, I would like to publish a new meaning a life book that elaborates on my own evolving thoughts. My first book on the topic was always meant as the prerequisite research necessary to write a second more personal book.

Finally, I would like to thank my readers, many of whom have made insightful comments, and a few of whom I’ve come to know through email. Despite what they might say about writing for themselves, most writers also wants to be read. So again thanks to all who have viewed these pages.

JGM

January 27, 2017

Alternative Facts: Did Orwell Make This Stuff Up?

For, after all, how do we know that two and two make four? Or that the force of gravity works? Or that the past is unchangeable? If both the past and the external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable—what then? ~ George Orwell, 1984.

In an earlier post i wrote how Donald Trump—an amygdala with a twitter account as my son-in-law puts it—had tweeted: “In addition to winning the electoral college in a landslide, I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” And on Monday Trump repeated this false claim in a meeting with congressional leaders. Mike Pence has defended Trump’s false claim by saying: “He’s entitled to express his opinion on that.”

Then, in the first official White House briefing, Press Secretary Sean Spicer blasted the press and contradicted all available evidence by claiming that the crowd was the “largest audience to ever witness and inaguration, period.” Trump’s senior adviser Kellyanne Conway defended Spicer last Sunday “Meet the Press” saying that Spicer didn’t perpetrate falsehoods but “gave alternative facts …”

These are just two recent examples of Trump’s mendacity. As of November 4th, 2016, The Toronto Star had already collected a database of almost 500 Trump lies. That Trump and his minions lie with impunity is hardly news. But as a retired philosophy professor who devoted his life to a search for truth, I’d like to briefly remind readers why the defenses offered by Pence and Conway are so ridiculous, and why the truth is so important.

Let’s begin by asking: Do you have a right to your own opinion? For example, suppose that you claim that you don’t believe in evolution since it’s just a theory. In response, I point out that when scientists use the word theory—as in atomic, gravitational, quantum, relativity, or evolutionary—it means what normal people mean by “true beyond any reasonable doubt.” I then explain that multiple branches of science converge on evolution—zoology, botany, genetics, molecular biology, geology, chemistry, anthropology, fossil evidence, etc. I also provide evidence that no legitimate biologist denies evolution, and that evolution is confirmed in laboratories around the world every single day. Now suppose your respond, “well I disagree and I have a right to my opinion.” Is that relevant? No it isn’t! I wasn’t claiming that you didn’t have a right to an opinion, I was showing you that your opinion is wrong.

The key here is understanding what you mean by a right. If you are referring to a political or legal right to believe anything you want, no matter how groundless, then you are correct that free speech allows you to ignorantly profess: “the earth is flat,” or “climate change in a hoax created by the Chineses,” or “the moon is made of cheese,” or whatever other nonsense you believe in. But you do not have a right to believe anything if you mean an epistemic right—one concerned with knowledge and truth. In that sense you are entitled to believe something only if you have good evidence, sound arguments, and so on. Ignoring this distinction, many people believe that their opinions are sacred and others must handle them with care. Then, when confronted with counterarguments, they don’t consider that they might be wrong, instead they take offense. But if someone is really interested in what’s true, they won’t take the presentation of counter evidence as an injury.

Of course many persons aren’t interested in what’s true; they just like believing certain things. If pressed about their opinions, they find it annoying and say: “I have a right to my opinions.” There are many reasons for this. Their false beliefs may be part of their group identity; they may find it painful to change their minds; they may be ignorant of other opinions; they may profit from holding their opinion; etc. But if someone continues to defend themselves against counterevidence with “I have a right to my opinion,” you can be assured of one thing—they aren’t interested in whether their opinion is true or not. So no Trump doesn’t have an epistemic right to his opinions because generally he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

As for “alternative facts” this idea defends a discredited theory that philosophers call epistemological relativism. The basic idea is that there are no universal truths about the world, just different ways of interpreting it. The theory dates back at least to the ancient Greek philosopher Protagoras, who said: “man is the measure of all things.” Today we capture this idea with clichés like: “What you believe is true for you and what I believe is true for me” or ” truth is in the eye of the beholder,” or “it’s all relative.” While it is easy to say such things, it is also easy to see that they are wrong.

Do you really think there are alternative facts? Your math teacher says that 2 + 2 = 4, but you like 6 so your alternative truth is 6. Really? Physicists say that the earth is spherical, but your alternative fact that the earth is flat. Just as good? Engineers have their way of constructing bridges but your alternative fact is that duct tape works just as well. Want to cross that bridge? Your doctor tells you to eat healthy, exercise, maintain an ideal weight, and engage in stress reduction activities, but your alternative facts are that eating poorly, living a sedentary lifestyle, being overweight, and smoking to relieve stress is just an alternative fact. No, you don’t really believe any of this. If you think about it for even a moment, you’ll realize that the truth is independent of your opinions; you’ll realize that there are true statements and false ones. And alternative facts are just falsehoods.

As a professional philosopher who devoted his life to a search for truth, the spectacle of constant lying and bullshitting truly pains me. Here is a great quote from fellow professor Michael Brenner. Let’s all keep shoveling out from under all the bullshit:

“THE TRUTH BE TOLD….”

THAT ADMONITION HAS FAINT RESONANCE WITHIN OUR PUBLIC DISCOURSE TODAY. CANDOR, VERACITY AND CONVICTION ARE RARELY DELIVERED NOR ARE THEY EXPECTED. ARTIFICE AND CONTRIVANCE RULE OUR THOUGHTS. TERMS OF REFERENCE ARE CONVENIENTLY OBSCURED, FACTS ARE NOTED OR MISSTATED AT WHIM. VIRTUAL REALITY SO ECLIPSES ACTUAL REALITY AS TO MAKE THE VERY NOTION OF TRUTH INFINITELY ELASTIC. AS A CONSEQUENCE, WE COLLECTIVELY HAVE BECOME LITERALLY MINDLESS.

CEASELESS IMAGE-MONGERING, LAXNESS AMONG THE POPULACE THAT IS ITS TARGET, AND A PANDERING FOURTH ESTATE TOGETHER HAVE DEGRADED THE WAY WE THINK AND BEHAVE IN THE PUBLIC REALM. OUR ULTRA-PERMISSIVE CULTURE GIVES LICENSE TO PUBLIC FIGURES TO SAY JUST ABOUT ANYTHING WITHOUT BEING HELD TO ACCOUNT – BY ETHICAL, POLITICAL, OR AESTHETIC STANDARDS. ALL DEMOCRACIES GENERATE ENORMOUS AMOUNTS OF TRASH. THAT IS ESPECIALLY SO IN AMERICA. THE KEY TO A HEALTHY DEMOCRATIC POLICY IS TO PROVIDE SHOVELLING CAPACITY TO MATCH. WE NO LONGER DO. THEREFORE, IT BECOMES EVERY CARING CITIZEN’S RESPONSIBILITY TO GRAB A SHOVEL …

January 25, 2017

Why Truth Matters

Truth, holding a mirror and a serpent (1896). Olin Levi Warner, Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C.

“It is morally as bad not to care whether a thing is true or not, so long as it makes you feel good, as it is not to care about how you got your money as long as you have got it.”

~ Edmund Way Teale

In my last post I discussed Princeton emeritus professor Harry Frankfurt’s distinction between lies and bullshit. I suggested that the difference between truth and falsity is even more important than the difference between lies and bullshit. Now I’d like to elaborate.

There are many reasons to revere truth: along with beauty and goodness it is one of the great ideas we judge by; it is universally regarded as a virtue; it is something, on this planet at least, that only humans discern; it is necessary to make good decisions about living our lives; and it allow us to predict the future and avoid future dangers. But there’s more.

When I started teaching ethics 30 years ago I learned that truth-telling is one of the only moral imperatives across cultures. Why would that be? Simply put, human communication is pointless unless we assume that others will tell the truth. If I ask you what time it is or for directions to London, I’m assuming you won’t lie. If I assume the opposite, there’s not much point to the question. Sincere, honest exchange essentially is communication, all the rest just manipulation.nother problem with lies, ignorance, and bullshit is that they undermine our rationality; they leave us slaves to our passions; and they keep us groping in the dark when we try to solve problems. Problems are hard to solve when you start with truth, much more so when you begin with falsehoods. Lies and nonsense will ultimately be our downfall, however temporarily attractive they may be. But why?

If we disregard the truth we’ll undo the project of classical Greece and the Enlightenment, when humans realized that reason could improve their world; if we disregard the truth we will remain slaves to the reptilian impulses of our anciently-formed brains; if we disregard the truth we’ll destroy our planet’s atmosphere and biosphere and kill ourselves. People suffer when the truth is distorted. So it is our choice. Face the truth of our biological and cultural heritage and transcend them, or we will all perish. But why is this so hard to understand?

I think that those so careless with their bullying, destruction, ignorance, power, and naked pursuit of self-interest just don’t realize or care how fragile biological and cultural life are. We live within what Carl Sagan called the thin blue line that separates us from the unimaginably cold and dark emptiness of space. Our atmosphere, climate, and ecosystem support life only if we support them. Culture too is extraordinarily fragile. It took 10,000 years to achieve, but we can destroy it in an instant. But even if we survive biologically, imagine living in a post-apocalyptic world. A world in which we have to reinvent physics, mathematics, chemistry and computer science. Where we would have to reconquer fire, reinvent the wheel, rediscover electricity. Where we would have to reconstruct atomic, relativity, evolutionary, gravitational, and quantum theory. A world without engineering, dentistry, or medicine. Think really hard about all that. Thomas Hobbes, familiar only with seventeenth-century science and technology described the scene like this:

“No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death: and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

Why then the hubris of ignorant people? They come and go, flickering flames with moth-like lifespans, nonetheless convinced of their importance. For some perspective they might contemplate their own death, or hear the voice of Carl Sagan:

January 23, 2017

Harry Frankfurt on Bullshit And Lying

[image error][image error]Emeritus professor of philosophy at Princeton Harry Frankfurt‘s book, On Bullshit, was a surprise best seller a few years ago. Given the public musings of our recently installed President, I thought it time to revisit the main idea of the book.

Frankfurt starts his book by jumping right in: “One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit.” This is a truism, but it provides small comfort to those of us forced to listen to so much of what is said by politicians, generals, clergy, and other uninformed citizens. It is seems no pain is too severe for them to inflict on those with relatively well-ordered minds.

But what is bullshitting and in what ways it is similar to, and different from, lying? Here are the basics as Frankfurt sees them:

Main Similarities –

1) Both liars and bullshitters (bsers) want you to believe that they are telling the truth.

2) And both want to get away with something.

Major Differences

Liars –

1) Liars engage in a conscious act of deception.

2) Liars know the truth, but attempt to hide it. (that’s what they want to get away with.)

3) Liars spread untruths, but they still accept the distinction between the truth and false.

Bsers

1) Bsers do not consciously deceive.

2) Bsers just don’t know or care about the truth. (that’s what they want to get away with.)

3) Bsers ignore or reject the distinction between truth and falsity altogether.

(Notice that what the liar says is necessarily false. If I stole your wallet or know that Jupiter is a gaseous planet, and claim otherwise, then what I’m saying is false. But if I have no idea of what I’m talking about, and then make various claims my bullshit might turn out to be correct.)

To reiterate the main point. Liars know the truth and try to hide it; bsers don’t know or care about the truth and try to hide their lack of commitment to it. Thus bullshitting is more like bluffing or faking. Surprisingly, Frankfurt thinks bullshit is more dangerous than lies because it erodes the possibility of the truth existing and being found. As he puts it:

It is impossible for someone to lie unless he thinks he knows the truth … Producing bullshit requires no such conviction. A person who lies is thereby responding to the truth, and he is to that extent respectful of it. When an honest man speaks, he says only what he believes to be true; and for the liar, it is correspondingly indispensable that he considers his statements to be false. For the bullshitter, however, all bets are off … He does not reject the authority of the truth, as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays no attention to it at all. By virtue of this, bullshit is a greater enemy of truth than lies are.

As to the cause of so much bullshit, Frankfurt argues that:

Bullshit is unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about. Thus the production of bullshit is stimulated whenever a person’s obligations or opportunities to speak about some topic are more excessive than his knowledge of the facts that are relevant to that topic.

Brief reflections – I accept the basic distinction between knowing the truth and lying about it, and not knowing or caring about the truth, and then trying to impress people by talking about things you know nothing about.

I’m less convinced that bullshitting is worse than lying. To clarify, consider the following:

1) I am scientifically literate. Therefore I know that biological evolution is true beyond any reasonable doubt. If I lie about this—say because I think that will make you more likely to contribute to my political or religious cause—then I subvert the truth.

2) I am scientifically illiterate. Therefore I don’t know if evolutionary theory is true or false. If I bullshit about this—say because I want you to think that I know what I’m talking about—then I ignore the truth.

In these two cases I think lying is worse than bullshitting because the liar always subverts the truth whereas the the bser might inadvertently tell the truth.

But if the bser not only doesn’t know or care about the truth, but rejects the very distinction between the two, if the bullshitter believes that there is no truth, then bullshitting is worse. A world that denies the existence of truth is a far worse one that still accepts the difference between truth and falsity.

What I think is more important than any distinction between lying and bullshitting is the mundane reason that Frankfurt gives for the importance of truth in his follow-up book On Truth[image error]. “How could a society which cared too little for truth make sufficiently well-informed decisions concerning the most suitable disposition of its public business?”

In my next post I will further explore why truth matters.

January 20, 2017

How to Cope with Today’s Presidential Inauguration

(This post is dedicated with love to a dedicated reader)

The American Political World Is Bad And Getting Worse

At the request of a reader depressed by today’s American presidential inauguration, I’m quickly writing a post. (This is a disclaimer as to its quality and completeness.) My own views—in more complete form—about the tragedy and danger of electing someone so manifestly unqualified, so psychologically, morally and intellectually unfit, (“An amygdala with a twitter account,” as my son puts it,) have been expressed over and over in previous posts. (For more scroll down on “politics” at the right, top corner of the page.)

My readers’ pain about our current state of affairs results from being more educated than most about the issues, political climate, new president, recent history, and the corruption, shenanigans, lies, and bs that surround us. Perhaps ignorance is bliss. And, as we have seen in a previous post, less education, even accounting for all other factors, was the biggest predictor of Trump support. It also evokes sadness to think of all the people who will suffer and die if some of the promises of the Republicans come true—the loss of health care for millions, increased economic inequality, etc. And this says nothing of people around the world who might die in wars resulting from a more unstable world.

Plato told us more than 2,000 years ago that you can’t have a good life without a good government, and you can’t have a good government without morally and intellectually virtuous leaders. He told us that democracy is one of the worst kinds of government—it’s the blind leading the blind—and that it inevitably leads to tyranny where power joins with vice. Trump in charge of nuclear codes; Perry in charge of nuclear energy; Tillerson and Exxon in charge of diplomacy; Sessions in charge of the law; Devos in charge of education—it would be hard for a dystopian novel to invent all this. Its 2017, but we live in 1984. The ministry of truth tells lie; the ministry of peace fights war; and no lie is too bold.

If only the masses truly understood what they did. They thought their TV was broke so they decided to try something new. Call knowledgeable people? No! Instead they banged on their TV with a hammer. Might work. Probably will make things worse.

And let me add—a society that has no respect for truth will make bad decisions. Replacing the rule of law and the pre-eminence of reason with the rule of the passions is a prescription for tyranny and anarchy as Aristotle told us long ago.

Sure one can wonder how we got from Nixon’s southern strategy, to Reagan saying government was the problem, to Delay’s and Gingrich’s moral corruption, to Republican obstructionism and disdain for truth, to the Tea Party, to the freedom caucus, to nearly one-party fascist rule. But this is the job of historians and political scientists to unpack. The past is closed, and we must move forward.

How To Cope

My reader doesn’t want more gloom and doom or historical analysis—she wants advice about coping. Lacking any special insights, I’ll just try to think the problem out as I write.

It seems there are at least two things you’re coping with today if you are relatively conscious of what’s going on politically. First, the bad things that have already happened, and second, the bad things that might happen as a result of this past.

As for what has already happened, you can’t do anything about it, so it is pointless to waste time thinking about it—to worry is an exercise in mindlessness. As for what might happen, we must remember that we don’t know the future. Many things we worry about never happen, so it is ineffective to worry about the merely possible. I know this is easier said than done, but realizing the pointlessness of worry is a start.

What is not pointless is doing something to make the dystopian future less likely. This may include writing, marching, creating beauty, getting politically active, or it may simply imply helping those few that you can help. It might mean being a good parent, so that we less psychologically damaged individuals run the government; it might mean learning more about marital conflict resolution; it might mean meditating to achieve greater mind control; it might be all of these things and more. But it definitely means doing something as opposed to ruminating about all the bad things that are happening.

Yet here we must also remember the sage advice of the Stoics, Buddhists, and Hindus. As they long ago discovered, you can’t control the world, you can only influence it. You shouldn’t be indifferent, passive, or apathetic; rather, you should discharge your duties to help the world. But remember that you can’t control the outcome of your efforts. Thus, as long as you do what you can, you shouldn’t feel shame or guilt.

This advice may seem trite, but I don’t know what else to say. Change what you can; ignore what you can’t change, and recognize the difference between the two, to paraphrase Niebuhr’s serenity prayer. Reflecting on this, it isn’t surprising that we can’t say much more than has been said in the 10,000 years of human culture. It isn’t likely that we would discover something that all the sages and seers missed. Perhaps then trite isn’t the right word for our advice. Our advice may lack originality, but that doesn’t make it worthless.

In short my advice is: 1) learn to control the mental disturbance caused by obsession over a past that you can’t change, or a future that may not come to be; and 2) act now to better the world and ourselves based on the best knowledge available, with the recognition that you can’t control the outcome of your efforts. We are suggesting a middle way between the helplessness and impotence that accompanies worry, and the hubris of thinking we can perfect the world, and our responsible that perfection.

These Two Pieces of Advice in World Literature

The most profound statement of these points—that we try to control our minds and fight to better the world—that I’m aware of come from French mathematician and philosopher Rene Descartes, who wrote about the peace that accompanies the stoical mind, and the Greek novelist and essayist Nikos Kazantzakis, who wrote deeper than anyone I’ve ever encountered about fighting the battle of life, and taking pride in our efforts.

Here is Descartes:

My third maxim was to endeavour always to conquer myself rather than fortune, and change my desires rather than the order of the world, and in general, accustom myself to the persuasion that, except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power; so that when we have done our best in respect of things external to us, all wherein we fail of success is to be held, as regards us, absolutely impossible: and this single principle seemed to me sufficient to prevent me from desiring for the future anything which I could not obtain, and thus render me contented; for since our will naturally seeks those objects alone which the understanding represents as in some way possible of attainment, it is plain, that if we consider all external goods as equally beyond our power, we shall no more regret the absence of such goods as seem due to our birth, when deprived of them without any fault of ours, than our not possessing the kingdoms of China or Mexico; and thus making, so to speak, a virtue of necessity, we shall no more desire health in disease, or freedom in imprisonment, than we now do bodies incorruptible as diamonds, or the wings of birds to fly with. But I confess there is need of prolonged discipline and frequently repeated meditation to accustom the mind to view all objects in this light; and I believe that in this chiefly consisted the secret of the power of such philosophers as in former times were enabled to rise superior to the influence of fortune, and amid suffering and poverty, enjoy a happiness which their gods might have envied. For, occupied incessantly with the consideration of the limits prescribed to their power by nature, they became so entirely convinced that nothing was at their disposal except their own thoughts, that this conviction was of itself sufficient to prevent their entertaining any desire of other objects; and over their thoughts they acquired a sway so absolute, that they had some ground on this account for esteeming themselves more rich and more powerful, more free and more happy, than other men who, whatever be the favours heaped on them by nature and fortune, if destitute of this philosophy, can never command the realization of all their desires.

And here is Kazantzakis (with my commentary):

Kazantzakis believed that the meaning of our lives is to find our place in the chain that links us with these undreamt of forms of life.

We all ascend together, swept up by a mysterious and invisible urge. Where are we going? No one knows. Don’t ask, mount higher! Perhaps we are going nowhere, perhaps there is no one to pay us the rewarding wages of our lives. So much the better! For thus may we conquer the last, the greatest of all temptations—that of Hope.[i]

I remember being devastated the first time I read those lines. I had rejected my religious upbringing, but why couldn’t I have a hope? Why was Kazantzakis taking that from me too? His point was that the honest and brave struggle without hope or expectation that they will ever arrive, be anchored, be at home. Like Ulysses, the only home Kazantzakis found was in the search itself. The meaning of life is found in the search and the struggle, not in any hope of success.

In the prologue of his autobiography, Report to Greco[image error], Kazantzakis claims that we need to go beyond both hope and despair. Both expectation of paradise and fear of hell prevent us from focusing on what is in front of us, our heart’s true homeland … the search for meaning itself. We ought to be warriors who struggle bravely to create meaning without expecting anything in return. Unafraid of the abyss, we should face it bravely and run toward it. Ultimately we find joy by taking full responsibility for our lives—joyous in the face of tragedy. Life is essentially struggle, and if in the end it judges us we should bravely reply, like Kazantzakis did:

General, the battle draws to a close and I make my report. This is where and how I fought. I fell wounded, lost heart, but did not desert. Though my teeth clattered from fear, I bound my forehead tightly with a red handkerchief to hide the blood, and ran to the assault.” [ii]

Surely that is as courageous a sentiment in response to the ordeal of human life as has been offered in world literature. It is a bold rejoinder to the awareness of the inevitable decline of our minds and bodies, as well as to the existential agonies that permeate life. It finds the meaning of life in our actions, our struggles, our battles, our roaming, our wandering, and our journeying. It appeals to nothing other than what we know and experience—and yet finds meaning and contentment there.

Just outside the city walls of Heraklion Crete one can visit Kazantzakis’ gravesite, located there as the Orthodox Church denied his being buried in a Christian cemetery. On the jagged, cracked, unpolished Cretan marble you will find no name to designate who lies there, no dates of birth or death, only an epitaph in Greek carved in the stone. It translates: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.”

The gravesite of Kazantzakis.

____________________________________________________________________

[i] James Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 11th ed. (Belmont CA.: Wadsworth, 2012), 656.

[ii] Nikos Kazantzakis, Report to Greco (New York: Touchstone, 1975), 23

January 18, 2017

Summary of Maslow on Self-Transcendence

It is quite true that [we live] by bread alone—when there is no bread. But what happens to [our] desires when there is plenty of bread and when [our bellies are] chronically filled?

~ Abraham Maslow

The Hierarchy of Needs

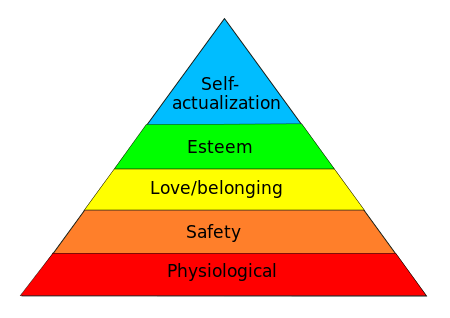

Abraham Maslow (1908 – 1970) was an American psychologist best known for creating a theory of psychological health known as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Textbooks usually portray Maslow’s hierarchy in the shape of a pyramid with our most basic needs at the bottom, and the need for self-actualization at the top.[1] Note how the iconic pyramid ignores self-transcendance:

The basic idea here is that survival demands food, water, safety, shelter, etc. Then, to continue to develop, you need your psychological needs for belonging and love met by friends and family, as well as a sense of self-esteem that comes with some competence and success. If you have had these needs fulfilled, then you can explore the cognitive level of ideas, the aesthetic level of beauty and, finally, you may experience the self-actualization that accompanies achieving your full potential.

Note that the higher needs don’t appear until lower needs are satisfied; so if you are hungry and cold, you can’t worry much about self-esteem, art, or mathematics. Notice also that the different levels correspond roughly to different stages of life. The needs of the bottom of the pyramid are predominant in infancy and early childhood; the needs for belonging and self-esteem predominate in later childhood and early adulthood; and the desire for self-actualization emerges with mature adulthood.

Self-Transcendence

What is less well-known is that Maslow amended his model near the end of his life, and therefore the conventional portrayal of his hierarchy is inaccurate, as it omits a description of his later thought. In his later thinking, he argued that the we can experience the highest level of development, what he called self-transcendence, by focusing on some higher goal outside ourselves. Examples include altruism, or spiritual awakening or liberation from egocentricity. Here is how he put it:

Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos. (The Farther Reaches of Human Nature[image error], New York, 1971, p. 269.)

Notice that placing self-transcendence above self-actualization results in a radically different model. While self-actualization refers to fulfilling your own potential, self-transcendence puts your own needs aside to serve something greater than yourself. In the process, self-trancenders may have what Maslow called peak experiences, in which they transcend personal concerns. In such mystical, aesthetic, or emotional states one feels intense joy, peace, well-being, and an awareness of ultimate truth and the unity of all things.

Maslow also believed that such states aren’t always transitory—some people might be able to readily access them. This led him to define another term, “plateau experience.” These are more lasting, serene, and cognitive states, as opposed to peak experiences which tend to be mostly emotional and temporary. Moreover, in plateau experiences one feels not only ecstasy, but the sadness that comes with realizing that others can’t have similar encounters. While Maslow believed that self-actualized, mature people are those most likely to have these self-transcendent experiences, he also felt that everyone was capable of having them.

MaGiven that Maslow’s humanistic psychology emphasized self-actualization and what is right with people, it isn’t surprising that his later transpersonal psychology explored extreme wellness or optimal well-being. This took the form of interest in persons who have expanded their normal sense of identity to include the transpersonal, or the underlying unity of all reality. (Thus the connection between transpersonal psychology and the mystical and meditative traditions of the world’s religions.)

Let me conclude by looking at two succinct and eloquent statement of the difference between self-actualization and self-transcendence. The first can be found in an excellent summary of the Maslow’s later thought: “Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification” by Mark E. Koltko-Rivera of New York University. As he puts it:

At the level of self-actualization, the individual works to actualize the individual’s own potential [whereas] at the level of transcendence, the individual’s own needs are put aside, to a great extent, in favor of service to others …

Maslow’s conclusion that self-transcendence is the highest level of psychological development reminds me of Victor Frankl, about whom I have written many times in this blog. In Man’s Search for Meaning, one of the most profound books ever written and one that I have taught out of many times, Frankl states:

The true meaning of life is to be found in the world rather than within [our own] psyche, as though it were a closed system … Human experience is essentially self-transcendence rather than self-actualization. Self-actualization is not a possible aim at all, for the simple reason that the more [we] would strive for it, the more [we] would miss it … In other words, self-actualization cannot be attained if it is made an end in itself, but only as a side effect of self-transcendence.

This seems to line up perfectly with what I think Maslow had in mind.

Reflections

I like the idea of going beyond self-actualization or fulfillment of personal potential to furthering causes beyond the self, or to experiencing communion beyond the self through peak and/or plateau experiences. I am receptive to these ideas as long as they derive from human or transhuman concerns without reference to a supernatural (imaginary) realm. I can accept mysticism if that means that some things are mysterious, but I reject it if it refers to anything supernatural—the mysterious is not supernatural.

What especially appeals to me is how Maslow’s later thinking about self-transcendence can be understood as prefiguring transhumanism. I doubt that Maslow consciously thought about it in this way, but clearly his questions about the limits of human development—and the possibility that there are few limits—foreshadows transhumanist thinking. In fact it was Maslow who said: “Human history is a record of the ways in which human nature has been sold short. The highest possibilities of human nature have practically always been underrated.” Perhaps we need both meditation and human enhancement through technology.

__________________________________________________________________________

Addendum: Excerpts from “Theory Z” (re-printed in: The Farther Reaches of Human Nature[image error])

1. For transcenders, peak experiences and plateau experiences become the most important things in their lives….

2. They speak more easily, normally, naturally, and unconsciously the language of Being (B-language), the language of poets, of mystics, of seers, of profoundly religious men….

3. They perceive unitively or sacrally (i.e., the sacred within the secular), or they see the sacredness in all things at the same time that they also see them at the practical, everyday D-level….

4. They are much more consciously and deliberately metamotivated. That is, the values of Being…, e.g., perfection, truth, beauty, goodness, unity, dichotomy-transcendence, B-amusement, etc. are their main or most important motivations.

5. They seem somehow to recognize each other, and to come to almost instant intimacy and mutual understanding even upon first meeting….

6. They are more responsive to beauty. This may turn out to be rather a tendency to beautify all things… or to have aesthetic responses more easily than other people do….

7. They are more holistic about the world than are the “healthy” or practical self-actualizers… and such concepts as the “national interest” or “the religion of my fathers” or “different grades of people or of IQ” either cease to exist or are easily transcended….

8. [There is] a strengthening of the self-actualizer’s natural tendency to synergy—intrapsychic, interpersonal, intraculturally and internationally…. It is a transcendence of competitiveness, of zero-sum of win-lose gamesmanship.

9. Of course there is more and easier transcendence of the ego, the Self, the identity.

10. Not only are such people lovable as are all of the most self-actualizing people, but they are also more awe-inspiring, more “unearthly,” more godlike, more “saintly”…, more easily revered….

11. … The transcenders are far more apt to be innovators, discoverers of the new, than are the healthy self-actualizers… Transcendent experiences and illuminations bring clearer vision of the B-Values, of the ideal, …of what ought to be, what actually could be, … and therefore of what might be brought to pass.

12. I have a vague impression that the transcenders are less “happy” than the healthy ones. They can be more ecstatic, more rapturous, and experience greater heights of “happiness” (a too weak word) than the happy and healthy ones. But I sometimes get the impression that they are as prone and maybe more prone to a kind of cosmic sadness or B-sadness over the stupidity of people, their self-defeat, their blindness, their cruelty to each other, their shortsightedness… Perhaps this is a price these people have to pay for their direct seeing of the beauty of the world, of the saintly possibilities in human nature, of the non-necessity of so much of human evil, of the seemingly obvious necessities for a good world…. Any transcender could sit down and in five minutes write a recipe for peace, brotherhood, and happiness, a recipe absolutely within the bounds of practicality, absolutely attainable. And yet he sees all this not being done… No wonder he is sad or angry or impatient at the same time that he is also “optimistic” in the long run.

13. The deep conflicts over the “elitism” that is inherent in any doctrine of self-actualization—they are after all superior people whenever comparisons are made—is more easily solved—or at least managed—by the transcenders than by the merely healthy self-actualizers. This is made possible because they … can sacralize everybody so much more easily. This sacredness of every person and even of every living thing, even of nonliving things … is so easily and directly perceived in its reality by every transcender that he can hardly forget it for a moment.

14. My strong impression is that transcenders show more strongly a positive correlation—rather than the more usual inverse one—between increasing knowledge and increasing mystery and awe…. For peak-experiencers and transcenders in particular, as well as for self-actualizers in general, mystery is attractive and challenging rather than frightening. … I affirm … that at the highest levels of development of humanness, knowledge is positively, rather than negatively, correlated with a sense of mystery, awe, humility, ultimate ignorance, reverence, and a sense of oblation [surrender to the Divine].

15. Transcenders, I think, should be less afraid of “nuts” and “kooks” than are other self-actualizers, and thus are more likely to be good selectors of creators (who sometimes look nutty or kooky). … To value a William Blake type takes, in principle, a greater experience with transcendence and therefore a greater valuation of it…. A transcender should also be more able to screen out the nuts and kooks who are not creative, which I suppose includes most of them.

16. …Transcenders should be more “reconciled with evil” in the sense of understanding its occasional inevitability and necessity in the larger holistic sense, i.e., “from above,” in a godlike or Olympian sense. Since this implies a better understanding of it, it should generate both a greater compassion with it and a less ambivalent and a more unyielding fight against it….

17. … Transcenders … are more apt to regard themselves as carriers of talent, instruments of the transpersonal, temporary custodians so to speak of a greater intelligence or skill or leadership or efficiency. This means a certain peculiar kind of objectivity or detachment toward themselves that to nontranscenders might sound like arrogance, grandiosity or even paranoia…. Transcendence brings with it the “transpersonal” loss of ego.

18. Transcenders are in principle (I have no data) more apt to be profoundly “religious” or “spiritual” in either the theistic or nontheistic sense. Peak experiences and other transcendent experiences are in effect also to be seen as “religious or spiritual” experiences….

19. … Transcenders, I suspect, find it easier to transcend the ego, the self, the identity, to go beyond self-actualization. … Perhaps we could say that the description of the healthy ones is more exhausted by describing them primarily as strong identities, people who know who they are, where they are going, what they want, what they are good for, in a word, as strong Selves… And this of course does not sufficiently describe the transcenders. They are certainly this; but they are also more than this.

20. I would suppose… that transcenders, because of their easier perception of the B-realm, would have more end experiences (of suchness) than their more practical brothers do, more of the fascinations that we see in children who get hypnotized by the colors in a puddle, or by the raindrops dripping down a windowpane, or by the smoothness of skin, or the movements of a caterpillar.

21. In theory, transcenders should be somewhat more Taoistic, and the merely healthy somewhat more pragmatic. B-cognition makes everything look more miraculous, more perfect, just as it should be. It therefore breeds less impulse to do anything to the object that is fine just as it is, less needing improvement, or intruding upon. …

22. … “Postambivalen[ce].” …Total wholehearted and unconflicted love, acceptance, … rather than the more usual mixture of love and hate that passes for “love” or friendship or sexuality or authority or power, etc.

23. [Transcenders are interested in a “cause beyond their own skin,” and are better able to “fuse work and play,” “they love their work,” and are more interested in “kinds of pay other than money pay”; “higher forms of pay and metapay steadily increase in importance.”] Mystics and transcenders have throughout history seemed spontaneously to prefer simplicity and to avoid luxury, privilege, honors, and possessions. …

24. I cannot resist expressing what is only a vague hunch; namely, the possibility that my transcenders seem to me somewhat more apt to be Sheldonian ectomorphs [lean, nerve-tissue dominated body-types] while my less-often-transcending self-actualizers seem more often to be mesomorphic [muscular body-types] (… it is in principle easily testable).

January 16, 2017

Analysis of the Last Line of Fitzgerald’s, The Great Gatsby

I few years ago I wrote back to back posts about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby[image error]. (One about the book’s first lines; the other about the its last lines.) An astute reader provided a careful analysis of the book’s famous last line that merits its own post. Here is that analysis with Fitzgerald’s text indented, and the reader’s analysis in [brackets.]

[For me it’s a haunting love story that reverberates with the human condition of…‘We are so smart. We can overcome anything, nature, others, and ourselves.’ And all the while, in the short term, we think we’re making things better. But in the long run, we are only making things worse. And that’s sadder than the love story. Here’s my breakdown:]

Most of the big shore places were closed now and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world.

[We drift back into the past to see that the island represents Daisy when Gatsby first laid eyes on her.]

Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house,

[The vanished trees demonstrate Gatsby’s toil and preparation over the years in an attempt to recapture that initial magic with Daisy. The vanished trees – like that magic – have been lost. Although Gatsby is too busy ‘doing’ to look up and see the destruction – the waste – the emptiness of his labor.]

had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams;

[The greatest of all human dreams, to have a soul mate.]

for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an æsthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired,

[Love? The unknown? Something you can’t describe or grasp because you can’t fully understand it. That was what Gatsby was feeling when he first encountered Daisy.]

face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

[From this first encounter with Daisy on, he would only drift farther and farther from his ‘Daisy island’ – regardless of how hard he paddled against the current (his toil for Daisy) – the current would only carry him farther and farther from his dream.]

And as I sat there, brooding on the old unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it.

[His excitement at seeing the green light after all his paddling over the years with one goal to reclaim Daisy. Green = money. The light = the dream of being with Daisy. The dream now seemed in reach.]

He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

[The dream – the possibility of being with Daisy – had begun receding from the moment Daisy discovered he didn’t have money. Gatsby was set adrift from his ‘Daisy island’. So, years later the possibility of reaching the dream was far away, far out of reach. He could see the point source of the green light in the darkness – but not the land or other perspective cues that would have told him that he was drifting away.]

Gatsby believed in the green light,

[He felt money – the thing that initially set him adrift – would be the thing that could make his dream come true. He believed in the power of money to make his dream come true. Sounds all too familiar in this ‘American Dream’ world in which we live.]

the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.

[But it was too late – although he worked for and gained the money (the green) – and although he could see a wonderful magical future with Daisy (the light) it had all the while been receding – imperceptibly to him since he was focused on working so hard. He couldn’t see – or didn’t pay attention to the fact that it was receding. The same way we may see vaccines or fracking or pesticides that kill everything but the GMO crops – as seemingly making things better in the short run – an omniscient narrator can see that in the long run, the loss of natural herd immunity, build up of toxins in our bodies, chemical pollution of our water, and the damage to the organisms in the soil are all making things worse in the long run. There is a long term price for the ‘more, faster, bigger’ – American Dream. We too often fail to see the long term price because we’re blinded by staring at the the short term excitement of the gains in the green light. Like Gatsby, we’re cutting down the trees on the island in an effort to reach our dream and in the process destroying the very island that is our dream. We are trying to get what we want – now – without regard to how it affects others and the environment in the future. In the end, we all lose.]

It eluded us then,

[His dream hasn’t yet come true.]

but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning—-

[In Gatsby’s perspective, all his plans seem to be working out and he believes that he is getting closer to his dream with Daisy and if he just continues day by day he will make it come true. We’re just like Gatsby. Things seem to be working out with our brilliant plans because we’re not paying attention to their effects along the way. Not acknowledging how they have made things worse so far on our voyage. We’re too busy making it better – to see or acknowledge the fact that we’re improving it into a failure.]

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

[The past is where we started. The dream. We feel we are progressing. But we’re not progressing in the big picture. And here, Nick, with the omniscient view of the narrator – can see what Gatsby could not. Nick can see that Gatsby – despite all his effort and sweat at paddling against the current – was drifting backward away from the island – (from Daisy). Repeating the same mistakes over and over – ignoring the signs from Daisy that she could not commit 100% to him, as he worked toward his dream. Gatsby was continually fooling himself with his dream of Daisy from the past – blinded by the green light – and could not see his forward progress was over powered by the permanence of the past (the current). At the end he feels so close. He’s waiting in the pool for her call. I see his murder as a merciful event. For he feels as close to his dream as he will ever get. He is at the top of the roller coaster. Daisy is too torn to fully commit to him and if he had lived to see this played out – everything would have been downhill from there. His psychological life would not only have been destroyed – he would have had to live through the destruction. And that would be crushing for Gatsby – as well as for the reader. We need a ‘Nick’ to help us see the bird’s eye view of what we’re doing.]

I thank my reader for his efforts.