John G. Messerly's Blog, page 78

September 4, 2017

Summary of Eric Hoffer’s, The True Believer

“Hatred is the most accessible and comprehensive of all the unifying agents … Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a god, but never without a belief in a devil.” ~ Eric Hoffer, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements[image error].

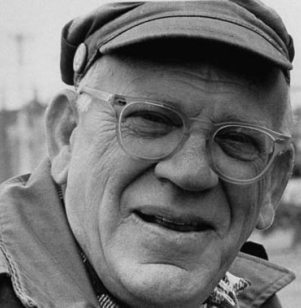

Eric Hoffer (1898 – 1983) was an American moral and social philosopher who worked for more than twenty years as a longshoremen in San Francisco. The author of ten books, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1983. His first book, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements[image error] (1951), is a work in social psychology which discusses the psychological causes of fanaticism. It is widely considered a classic.

Overview

The first lines of Hoffer’s book clearly state its purpose:

This book deals with some peculiarities common to all mass movements, be they religious movements, social revolutions or nationalist movements. It does not maintain that all movements are identical, but that they share certain essential characteristics which give them a family likeness.

All mass movements generate in their adherents a readiness to die and a proclivity for united action; all of them, irrespective of the doctrine they preach and the program they project, breed fanaticism, enthusiasm, fervent hope, hatred and intolerance; all of them are capable of releasing a powerful flow of activity in certain departments of life; all of them demand blind faith and single-hearted allegiance.

All movements, however different in doctrine and aspiration, draw their early adherents from the same types of humanity; they all appeal to the same types of mind.

Though there are obvious differences between the fanatical Christian, the fanatical Mohammedan, the fanatical nationalist, the fanatical Communist and the fanatical Nazi, it is yet true that the fanaticism which animates them may be viewed and treated as one …

This book concerns itself chiefly with the active, revivalist phase of mass movements. This phase is dominated by the true believer—the man of fanatical faith who is ready to sacrifice his life for a holy cause …

Yet Hoffer’s interest is to understand and explain, not to judge: “The assumption that mass movements have many traits in common does not imply that all movements are equally beneficent or poisonous. The book passes no judgments, and expresses no preferences. It merely tries to explain… (pp. xi-xiii)

Part 1 – The Appeal of Mass Movements

Hoffer says that mass movements begin when discontented, powerless people lose faith in existing institutions and demand change.

Starting out from the fact that the frustrated predominate among the early adherents of all mass movements … it is assumed: 1) that frustration of itself, without any proselytizing prompting from the outside, can generate most of the peculiar characteristics of the true believer; 2) that an effective technique of conversion consists basically in the inculcation and fixation of proclivities and responses indigenous to the frustrated mind. (p. xii)

Feeling hopeless, such people participate in movements that allow them to become part of a larger collective. “ . . . a mass movement … appeals not to those intent on bolstering and advancing a cherished self, but to those who crave to be rid of an unwanted self because it can satisfy the passion for self-renunciation.” (p. 12)

Put another way, Hoffer says: ““Faith in a holy cause is to a considerable extent a substitute for the loss of faith in ourselves.” (p. 14)

Leaders inspire these movements, but the seeds of mass movements must already exist for the leaders to be successful. And while mass movements typically blend of nationalist, political and religious ideas, they all compete for angry and/or marginalized people.

Part 2 – The Potential Converts

The destitute are not usually converts to mass movements, as they are too busy trying to survive to become engaged. But what Hoffer calls the “new poor,” those who previously had wealth or status but who have now lost it, are potential converts for mass movements. Such people are resentful and blame others for their problems. Mass movements also attract the partially assimilated—those who feel alienated from mainstream culture.

Though the disaffected are found in all walks of life, they are most frequent in the following categories: a) the poor, b) misfits, c) outcasts, d) minorities, e) adolescent youth, f) the ambitious, g) those in the grip of some vice or obsession, h) the impotent (in body or mind), i) the inordinately selfish, j) the bored, k) the sinners. (p. 25)

What converts all share is the feeling that their lives are meaningless and worthless.

A rising mass movement attracts and holds a following not by its doctrine and promises but by the refuge it offers from the anxieties, barrenness, and meaninglessness of an individual existence. It cures the poignantly frustrated not by conferring on them an absolute truth or remedying the difficulties and abuses which made their lives miserable, but by freeing them from their ineffectual selves—and it does this by enfolding and absorbing them into a closely knit and exultant corporate whole. (p. 41)

Hoffer emphasizes that creative people—those who experience creative flow—aren’t usually attracted to mass movements. Creativity provides inner joy which both acts as an antidote to the frustrations with external hardships. Creativity also relieves boredom, one of the main causes of mass movements:

There is perhaps no more reliable indicator of a society’s ripeness for a mass movement than the prevalence of unrelieved boredom. In almost all the descriptions of the periods preceding the rise of mass movements there is reference to vast ennui; and in their earliest stages mass movements are more likely to find sympathizers and

support among the bored than among the exploited and oppressed. To a deliberate fomenter of mass upheavals, the report that people are bored still should be at least as encouraging as that they are suffering from intolerable economic or political abuses. (p. 51-52)

Part 3 – United Action and Self-Sacrifice

Of a follower, mass movements demand a “total surrender of a distinct self.” (p. 117) Thus a follower identifies as “a member of a certain tribe or family.” (p. 62) Mass movements also denigrate and “loath the present.” (p. 74) By regarding the modern world as worthless, the movement inspires a battle against it.

What surprises one, when listening to the frustrated as the decry the present and all its works, is the enormous joy they derive from doing so. Such delight cannot come from the mere venting of a grievance. There must be something more—and there is. By expiating upon the incurable baseness and vileness of the times, the frustrated soften their feeling of failure and isolation … (p. 75)

Mass movements also “promote the use of doctrines that elevate faith over reason and serve as “fact-proof screens between the faithful and the realities of the world. (p. 79)

The effectiveness of a doctrine does not come from its meaning but from its certitude…presented as the embodiment of the one and only truth. If a doctrine is not unintelligible, it has to be vague; and if neither unintelligible nor vague, it has to be unverifiable. One has to get to heaven or the distant future to determine the truth of an effective doctrine….simple words are made pregnant with meaning and made to look like symbols in a secret message. There is thus an illiterate air about the most literate true believer. (pp. 80-81).

Thus believers are good at ignoring facts that contradict their fervent beliefs. But this hides the fact that,

The fanatic is perpetually incomplete and insecure. He cannot generate self-assurance out of his individual sources … but finds it only by clinging passionately to whatever support he happens to embrace. The passionate attachment is the essence of his blind devotion and religiosity, and he sees in it the sources of all virtue and strength … He sacrifices his life to prove his worth … The fanatic cannot be weaned away from his cause by an appeal to reason or his moral sense. He fears compromise and cannot be persuaded to qualify the certitude and righteousness of his holy cause.” (p. 85).

So the doctrines of the mass movement must not be questioned—they are regarded with certitude—and they are spread through “persuasion, coercion, and proselytization.” Persuasion works best on those already sympathetic to the doctrines, but it must be vague enough to allow “the frustrated to… hear the echo of their own musings in the impassioned double talk.” (p. 106) Hoffer quotes Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels: “a sharp sword must always stand behind propaganda if it is to be really effective.” (p. 106) The urge to proselytize comes not from a deeply held belief in the truth of doctrine but from an urge of the fanatic to “strengthen his own faith by converting others.” (p. 110)

Moreover, mass movements need an object of hate, which unifies true believers, and “the ideal devil is a foreigner.” (p. 93) Mass movements need a devil. But in reality the “hatred of a true believer is actually a disguised self-loathing …” and “the fanatic is perpetually incomplete and insecure.” (p. 85) Through their fanatical action and personal sacrifice, the fanatic tries to give their life meaning.

Part 4 – Beginning and End

Hoffer states that three personality types typically lead mass movements: “men of words”, “fanatics”, and “practical men of action.” In the beginning: “men of words” lead the movements. (In the USA think of the late William F. Buckley.) Men of words try to “discredit the prevailing creeds” and creates a “hunger for faith” which is then fed by “doctrines and slogans of the new faith.” (p. 140) Slowly followers emerge.

Then fanatics take over. (In the USA think the Koch brothers, Murdoch, Limbaugh, O’Reilly, Hannity, etc.) Fanatics don’t find solace in literature, philosophy or art. Instead viciousness and the urge to destroy characterizes them; perpetual struggle for power and change fulfills them. But after mass movements transform the social order, the insecurity of their followers is no longer ameliorated. At this point the “practical men of action” take over and try to lead the new order. Now the leaders try to control their former followers.

In the end mass movements that succeed often bring about a social order worse than the previous one. (This was one of Will Durant’s The Lessons of History.[image error]“) As Hoffer puts it near the end of his work: “All mass movements … irrespective of the doctrine they preach and the program they project, breed fanaticism, enthusiasm, fervent hope, hatred, and intolerance.” (p. 141)

__________________________________________________________________________

Quotes from Hoffer, Eric (2002). The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. ISBN 978-0-060-50591-2.

August 28, 2017

Summary of Cicero on Old Age

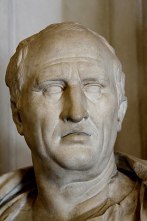

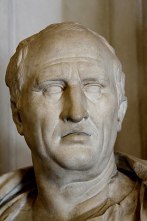

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Cicero (106 BC – 43 BC) was a Roman politician and lawyer who is considered one of Rome’s greatest orators and prose stylists. “On Old Age” is an essay written on the subject of aging and death. It has remained popular because of its profound subject matter as well as its clear and beautiful language.

The treatise defends old age against its alleged disadvantages: “first, that it withdraws us from active pursuits; second, that it makes the body weaker; third, that it deprives us of almost all physical pleasures; and, fourth, that it is not far removed from death.” He examines each claim in turn.

Charge #1 – “Old age withdraws us from active pursuits …”

Cicero replies that older people remain active, just in different ways than their younger counterparts. While they may less physically adept, they may do more for their community, or they be more introspective and philosophical. As he puts it:

Those… who allege that old age is devoid of useful activity… are like those who would say that the pilot does nothing in the sailing of his ship, because, while others are climbing the masts, or running about the gangways, or working at the pumps, he sits quietly in the stern and simply holds the tiller. He may not be doing what younger members of the crew are doing, but what he does is better and much more important. It is not by muscle, speed, or physical dexterity that great things are achieved, but by reflection, force of character, and judgment; in these qualities old age is usually not … poorer, but is even richer.

So for Cicero, the prudence and wisdom that accompanies aging more than compensates for declining physical vigor. (Research has found that elders outperformed younger adults in understanding and solving complex social situations.) He says that for Homer, Sophocles, Pythagoras, Plato and others, old age did not “destroy their interests of take away their powers of expression.” Old age can be a busy time where we continue lifelong projects or develop new interests.

Charge #2 – Old age “makes the body weaker …”

Cicero acknowledges that aging negatively affects the body, but

At my age, I don’t yearn for the physical vigor of a young man … any more than in my youth I yearned for the vigor of a bull or an elephant. Use whatever you have: that is the right way. Do whatever is to be done in proportion as you have the strength to do it … Use the advantages you have while you have them; when they are gone, don’t sit around wishing you could get them back.

He then proceeds:

enjoy the blessing of strength while you have it and do not bewail it when it is gone unless… you believe that youth must lament the loss of infancy, or early manhood the passing of youth. Life’s race-course is fixed; Nature has only a single path and that path is run but once, and to each stage of existence has been allotted its own appropriate quality; so that the weakness of childhood, the impetuosity of youth, the seriousness of middle life, the maturity of old age — each bears some of Nature’s fruit, which must be garnered in its own season.

He also notes that we can lessen aging’s impact through exercise, moderation in food and drink, and by caring for our intellect. Ideally we should care for our body throughout our lives so that they remain strong into old age. Often our bodies betray us in large part because we have mistreated them in our youth.

Still it is our intellect that we should cultivat as we age. Physical vigor is good, and we should try to be healthy, but “much greater care is due to the mind and soul; for they, too, like lamps, grow dim with time, unless we keep them supplied with oil.” So achieving wisdom in old age is paramount.

Charge #3 – Old age “deprives us of almost all physical pleasures …”

Cicero responds that eating and drinking still give sensual pleasure, and that he finds that he enjoys meals with friends even more than he did as a youth. But to the extent that old age detracts from enjoying such pleasures, this is mostly beneficial:

the fact that old age feels little longing for sensual pleasures not only is no cause for reproach, but rather is ground for the highest praise. Old age lacks the heavy banquet, the loaded table, and the oft-filled cup; therefore it also lacks drunkenness, indigestion, and loss of sleep. But if some concession must be made to pleasure, since her allurements are difficult to resist, … then I admit that old age, though it lacks immoderate banquets, may find delight in temperate repasts.

Regarding sexual pleasure he writes:

… granting that youth enjoys pleasures of that kind with a keener relish … although old age does not possess these pleasures in abundance, yet it is by no means wanting in them. Just as (a great actor) gives greater delight to the spectators in the front row at the theatre, and yet gives some delight even to those in the last row, so youth, looking on pleasures at closer range, perhaps enjoys them more, while old age, on the other hand, finds delight enough in a more distant view.

So while the intensity of sensual pleasure diminishes with age, it can be appreciated in new ways.

Charge #4 – Old age “is not far removed from death …”

Cicero responds by dismissing the fear of death:

death should be held of no account! For clearly (the impact of) death is negligible if it utterly annihilates the soul, or even desirable, if it conducts the soul to some place where it is to live forever. What, then, shall I fear, if after death I am destined to be either not unhappy or happy?

As for the hopes of younger versus older people Cicero states:

the young man hopes that he will live for a long time and this hope the old man cannot have. Yet (the old man ) is in better case than the young man, since what the latter merely hopes for, the former has already attained; the one wishes to live long, the other has lived long.

In fact death should be seen as something to look forward to after a life well-lived:

Therefore, when the young die I am reminded of a strong flame extinguished by a torrent; but when old men die it is as if a fire had gone out without the use of force and of its own accord, after the fuel had been consumed; and, just as apples when they are green are with difficulty plucked from the tree, but when ripe and mellow fall of themselves, so, with the young, death comes as a result of force, while with the old it is the result of ripeness. To me, indeed, the thought of this “ripeness” for death is so pleasant, that the nearer I approach death the more I feel like one who is in sight of land at last and is about to anchor in his home port after a long voyage.

Cicero conclusion reinforces the above themes:

…my old age sits light upon me…, and not only is not burdensome, but is even happy. For as Nature has marked the bounds of everything else, so she has marked the bounds of life. Moreover, old age is the final scene … in life’s drama, from which we ought to escape when it grows wearisome and, certainly, when we have had our fill.

Recap – Cicero’s Lessons on Successful Aging

1. A good old age begins in youth – Cultivate the virtues that will serve you well in old age

—moderation, wisdom, courage—in your youth.

2. Old age can be a good part of life – You can live well in old age if you are wise.

3. Youth and old age differ – Accept that as physical vitality declines, wisdom can grow.

4. Elders can teach the young – Older people have much to teach the young, and younger people can invigorate older persons.

5. We can be active in old age, with limitations. – We should try to remain healthy and active, while accepting our limitations.

6. The aged should exercises our minds. – We should continually learn new things.

7. Older people should be assertive. – Older people will be respected only if they aren’t too passive.

8. Sex is overrated – We should accept physical limitations and enjoy other aspects of life.

9. Pursue enjoyable, worthwhile activities. – Happiness derives in large part from doing productive work that gives us joy.

10. Don’t fear death. – Don’t cling to life—a good actor knows when to leave the stage.

__________________________________________________________________________

A new book on the topic that I would recommend is Greenstein and Holland’s Lighter as We Go: Virtues, Character Strengths, and Aging[image error] (Oxford University Press).

[image error] [image error]

Summary of Cicero on Aging

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Cicero (106 BC – 43 BC) was a Roman politician and lawyer who is considered one of Rome’s greatest orators and prose stylists. “On Old Age” is an essay written on the subject of aging and death. It has remained popular because of its profound subject matter as well as its clear and beautiful language.

The treatise defends old age against its alleged disadvantages which are: “first, that it withdraws us from active pursuits; second, that it makes the body weaker; third, that it deprives us of almost all physical pleasures; and, fourth, that it is not far removed from death.” He then examines each claim in turn.

Charge #1 – “Old age withdraws us from active pursuits… ”

Cicero replies that older people remain active, just in different ways than their younger counterparts. While they may less physically adept, they may do more for their community, or be more introspective and philosophical. As he puts it:

Those… who allege that old age is devoid of useful activity… are like those who would say that the pilot does nothing in the sailing of his ship, because, while others are climbing the masts, or running about the gangways, or working at the pumps, he sits quietly in the stern and simply holds the tiller. He may not be doing what younger members of the crew are doing, but what he does is better and much more important. It is not by muscle, speed, or physical dexterity that great things are achieved, but by reflection, force of character, and judgment; in these qualities old age is usually not … poorer, but is even richer.

So for Cicero, the prudence and wisdom that accompanies aging more than compensates for declining physical vigor. (Research has found that elders outperformed younger adults in understanding and solving complex social situations.) He says that for Homer, Sophocles, Pythagoras, Plato and others, old age did not “destroy their interests of take away their powers of expression.” Old age can be a busy time where we continue lifelong projects or develop new interests.

Charge #2 – Old age “makes the body weaker …”

Cicero acknowledges that aging negatively affects the body, but

At my age, I don’t yearn for the physical vigor of a young man … any more than in my youth I yearned for the vigor of a bull or an elephant. Use whatever you have: that is the right way. Do whatever is to be done in proportion as you have the strength to do it … Use the advantages you have while you have them; when they are gone, don’t sit around wishing you could get them back.

He the proceeds to explain:

enjoy the blessing of strength while you have it and do not bewail it when it is gone unless… you believe that youth must lament the loss of infancy, or early manhood the passing of youth. Life’s race-course is fixed; Nature has only a single path and that path is run but once, and to each stage of existence has been allotted its own appropriate quality; so that the weakness of childhood, the impetuosity of youth, the seriousness of middle life, the maturity of old age — each bears some of Nature’s fruit, which must be garnered in its own season.

He also notes that we can lessen aging’s impact through exercise, moderation in food and drink, and by caring for our intellect. Ideally we should care for our body throughout our lives so that they remain strong into old age. Often our bodies betray us because we have mistreated them in our youth.

Still it is our intellect that should be most cultivated as we age. Physical vigor is good and we should cultivate bodily health, but “much greater care is due to the mind and soul; for they, too, like lamps, grow dim with time, unless we keep them supplied with oil.” So again we should appreciate the wisdom of old age.

Charge #3 – Old age “deprives us of almost all physical pleasures … ”

Cicero responds that eating and drinking still give sensual pleasure, and he finds that he enjoys meals with friends even more than he did as a youth. But even old age has detracted from enjoying such pleasures, this is mostly beneficial:

the fact that old age feels little longing for sensual pleasures not only is no cause for reproach, but rather is ground for the highest praise. Old age lacks the heavy banquet, the loaded table, and the oft-filled cup; therefore it also lacks drunkenness, indigestion, and loss of sleep. But if some concession must be made to pleasure, since her allurements are difficult to resist, … then I admit that old age, though it lacks immoderate banquets, may find delight in temperate repasts.

Regarding sexual pleasure he responds:

… granting that youth enjoys pleasures of that kind with a keener relish, …although old age does not possess these pleasures in abundance, yet it is by no means wanting in them. Just as (a great actor) gives greater delight to the spectators in the front row at the theatre, and yet gives some delight even to those in the last row, so youth, looking on pleasures at closer range, perhaps enjoys them more, while old age, on the other hand, finds delight enough in a more distant view.

Thus Cicero argues that while the intensity of sensual pleasure diminishes with age, it can be appreciated in a different way in old age.

Charge #4 – Old age “is not far removed from death.”

Cicero responds by dismissing the fear of death:

death should be held of no account! For clearly (the impact of) death is negligible if it utterly annihilates the soul, or even desirable, if it conducts the soul to some place where it is to live forever. What, then, shall I fear, if after death I am destined to be either not unhappy or happy?

As for the hopes of younger versus older people Cicero states:

the young man hopes that he will live for a long time and this hope the old man cannot have. Yet (the old man ) is in better case than the young man, since what the latter merely hopes for, the former has already attained; the one wishes to live long, the other has lived long.

In fact death should be seen as something to look forward to after a life well-lived:

Therefore, when the young die I am reminded of a strong flame extinguished by a torrent; but when old men die it is as if a fire had gone out without the use of force and of its own accord, after the fuel had been consumed; and, just as apples when they are green are with difficulty plucked from the tree, but when ripe and mellow fall of themselves, so, with the young, death comes as a result of force, while with the old it is the result of ripeness. To me, indeed, the thought of this “ripeness” for death is so pleasant, that the nearer I approach death the more I feel like one who is in sight of land at last and is about to anchor in his home port after a long voyage.

Cicero conclusion reinforces the above themes:

…my old age sits light upon me…, and not only is not burdensome, but is even happy. For as Nature has marked the bounds of everything else, so she has marked the bounds of life. Moreover, old age is the final scene, as it were, in life’s drama, from which we ought to escape when it grows wearisome and, certainly, when we have had our fill.

Conclusion – Cicero’s Lessons on Successful Aging

1. A good old age begins in youth – Cultivate the virtues that will serve you well in old age

—moderation, wisdom, courage—in your youth.

2. Old age can be a good part of life – You can live well in old age if you are wise.

3. Youth and old age are different – Accept that as physical vitality declines, wisdom can grow.

4. Elders can teach the young – Older people have much to teach the young, and younger people can invigorate older persons.

5. We can be active in old age, with limitations. – We should try to remain healthy and active, but we must accept our limitations.

6. The should exercises our minds. – We should continually learn new things.

7. Older people should be assertive. – Older people will be respected only if they aren’t too passive.

8. Sex is overrated – We should accept physical limitations and enjoy other aspects of life.

9. Pursue enjoyable, worthwhile activities. – Happiness derives in large part from doing productive work that gives us joy.

10. Don’t fear death. – Don’t cling to life—a good actor knows when to leave the stage.

__________________________________________________________________________

A new book on the topic that I would recommend is Greenstein and Holland’s Lighter as We Go: Virtues, Character Strengths, and Aging[image error] (Oxford University Press).

[image error] [image error]

August 26, 2017

Modern Philosophers on Human Nature

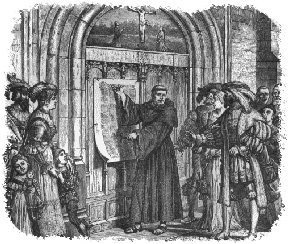

The Reformation: Where Lies the Authority for Faith? – Christianity dominated the social, political, and religious life of Europe for more than a 1000 years, from the fall of Rome till at least the 17th century. The first major division of Christianity occurred with the schism of 1054 when the Eastern Orthodox Church broke from the western Catholic Church. But four successive cultural movements slowly unraveled the hegemony of the Catholic Church in Europe: the Renaissance, the Reformation, the 17th century scientific revolution, and the Enlightenment.

The Renaissance refers to the flowering of reason and humanism, literally “the rebirth” or rediscovery of Greek and Roman thought. The next great cultural movement was the Reformation, begun when Martin Luther posted his ninety-five thesis of the door of his German church. There had been other reforming voices before Luther, such as John Wycliffe and John Hess, but Luther’s protest really sparked the Reformation. [Both Wycliffe, who was one of the first to translate the Bible into English, and Huss met terrible fates. Huss was burned at the stake, while Wycliffe was declared a heretic whose remains exhumed and burned. William Tyndale, another of the early translators of the Bible was also burned at the stake.]

Luther had many disagreements with the Church, especially with their selling of indulgences which allowed people to believe they could buy their way into heaven. Theologically Luther believed that one is save by faith and grace alone, thus there was no need for the Church to act as an intermediary between god and humans. He also rejected reason which he famously called a whore. [He rejects the Church, its scholasticism (using reason in theology) and the rise of reason associated with the Renaissance.] And he emphasized the scripture as a truer source of religious truth than the Church.

This religious reform—especially the emphasis on faith and the authority of the Bible—spread throughout northern Europe. The emphasis on scripture was particularly strong in the thought of John Calvin. He helped develop a theocratic state in Geneva, and his ideas spread with the puritans to England and then to America where the doctrine of the infallibility of the Bible was developed. Of course this hardly settled matters as the issue of interpretation of the Bible arose. In response some sects like the Quakers placed more emphasis on religious experience. All of this led to centuries of violent conflict and genocide between various religious groups. [Today Europe is almost completely secular, while America is much more overtly religious.]

The Rise of Science: How Does Scientific Method Apply To Human Beings? – The 17thcentury scientific revolution changed the world. [Look around you anywhere and you see the overwhelming evidence of its influence.] The combination of an experimental method [most associated with Francis Bacon] and the mathematical reasoning utilized by Galileo and Newton showed that science could explain the heavens and earth. Consequently appeals to the Bible and the Church in matters of science began to seem futile. But how far can a scientific approach go in explaining human beings? Are humans material only or is there some immaterial component to them?

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1659) – Hobbes was a materialist [one who believes only matter exists] who rejected dualism [the idea that both matter and mind/soul exist.] He argued that the idea of an immaterial soul made no sense, espousing instead a materialistic explanation for all states of body and brain—human nature is exclusively materialistic. Hobbes also argued that humans are selfish, desiring wealth, power, fame, food, clothing, shelter and more for themselves. But as all these things are in limited supply, humans are at war with each other in an effort to obtain them. To avoid this state of war humans accept a coercive political authority to adjudicate their disputes—they trade some of their freedom for the security of the state. This is ultimately in each individual’s interest, inasmuch as it helps them survive. Hobbes was also an atheist who wanted the churches subordinate to the state.

Rene Descartes (1596 – 1659) – Descartes is probably the most famous exponent of the dualist view—human nature is composed of a material body and an immaterial mind/soul. The body occupies space and is studied by science; the mind/soul doesn’t occupy space and can’t be studied by science. This immaterial component can exist without the body. While one can doubt the existence of the body and the external world—perhaps you are dreaming the world or some evil demon is making you think there is one—you cannot doubt your own consciousness. [Even if you are deceived about the existence of your consciousness, you must be to be deceived. Thus “I think therefore I am.] In this way Descartes could remain a Catholic and a and scientist at the same time.

[image error]

Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677) – Spinoza attempts to reconcile dualism and materialism. Spinoza is a pantheist—god and nature are identical. [This begins to reconcile the material and immaterial.] He also advocated the dual-aspect theory of mind or human nature. For Spinoza mind and matter are two aspects of one underlying reality. Mental events are the same as brain events but we can describe these events as either mental or physical. In other words mind is what the brain does. [This is a bit more materialistic than dualistic.]

The Enlightenment: Can Science Be Our Guide To Life? – As science became accepted as the only cognitive authority in the world [religion and science basically has switched places since the middle ages] the question of apply these insights to human nature arose. Could reason and science explain human beings and improve the human condition? [The evidence is in … the answer is YES.] Could scientific explanations replace religious, philosophical, poetic explanations of human beings? Gradually rational approaches, especially in politics, replaced religious explanations.

David Hume (1711 -1776) – Hume was an empiricist, one who believes that knowledge derives from sense experience. Reason tells us about the relationship between logical and mathematical ideas, but sense experience tells us how the world works. Our ideas are derived from impressions, either sense impressions or introspective reflection of one’s own mind. What we call matter is just a bundle of perceptions—and so are we. There is no soul or self, only a flow of consciousness, a succession of mental states. We are simply a bundle of perceptions, a continual flow of perceptions without any underlying substance. [This is similar to the doctrine of no self in Buddhism.] Needless to say there are no religious overtones to Hume’s thought, as he was a thorough going atheist and freethinker.

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) – Rousseau is famous for his belief in the goodness of humans before the corrupting influence of civilization [the so-called “noble savage.”] He also believed that children have a good intrinsic nature that is corrupted by society. Like most romantics he believed that the natural was good. [This is quite dubious.] However he doesn’t allow for the innate selfishness so characteristic of the human race.

All these strains of thought will lead to Immanuel Kant, the crowing figure of the Enlightenment.

August 21, 2017

Bob Dylan’s “Only A Pawn in Their Game” and Charlottsville VA

Bob Dylan’s song, “Only A Pawn In Their Game,” came to mind while watching the neo-Nazis and white supremacists at Charlottesville VA. Let me say that race is a social construct, not a genetic or biological one, and none of the protestors are really white, whatever that means. Their DNA is from all over the world. Furthermore, not only did modern humans originate in Africa, but all of us living today outside Africa today have small amounts of Neanderthal DNA! Moreover, our DNA is about 99% identical with chimpanzee DNA. Simple observation of humans should confirm this last fact.

But here’s what interesting about the protestors. They vilify African-Americans, Jews, Hispanics and others, not realizing their real oppressors are people like their racist President, who has a long history of scamming the working classes.

The plutocrats have always divided the rest of us, distracting us from the fact that they oppress us. (They write influence the laws that shred the social safety net, and keep wages down along with their taxes.)They encourage racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia and other forms of bigotry so that we see our fellows as the enemy. In other words they create scapegoats who divert attention away from themselves, and redirecting anger helps them retain their power. But it’s weatly bankers and wall street and corporations that make most of our lives hard—not immigrants, atheists, blacks or LGBT folks.

It’s straightforward. If you have power, you want to keep it. But you might create a revolution if you oppress or exploit your subjects. So instead you direct your subject’s anger away toward those they should be aligned with—other oppressed people.

The lyrics of the song are below. Medgar Evers gave his life in the struggle for justice, and I fear he won’t be the last.

A bullet from the back of a bush

Took Medgar Evers’ blood

A finger fired the trigger to his name

A handle hid out in the dark

A hand set the spark

Two eyes took the aim

Behind a man’s brain

But he can’t be blamed

He’s only a pawn in their game

A South politician preaches to the poor white man

“You got more than the blacks, don’t complain

You’re better than them, you been born with white skin, ” they explain

And the Negro’s name

Is used, it is plain

For the politician’s gain

As he rises to fame

And the poor white remains

On the caboose of the train

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game

The deputy sheriffs, the soldiers, the governors get paid

And the marshals and cops get the same

But the poor white man’s used in the hands of them all like a tool

He’s taught in his school

From the start by the rule

That the laws are with him

To protect his white skin

To keep up his hate

So he never thinks straight

‘Bout the shape that he’s in

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game

From the poverty shacks, he looks from the cracks to the tracks

And the hoofbeats pound in his brain

And he’s taught how to walk in a pack

Shoot in the back

With his fist in a clinch

To hang and to lynch

To hide ‘neath the hood

To kill with no pain

Like a dog on a chain

He ain’t got no name

But it ain’t him to blame

He’s only a pawn in their game

Today, Medgar Evers was buried from the bullet he caught

They lowered him down as a king

But when the shadowy sun sets on the one

That fired the gun

He’ll see by his grave

On the stone that remains

Carved next to his name

His epitaph plain

Only a pawn in their game

August 19, 2017

Summary of Medieval Philosophers on Human Nature

(This post is my summary of a chapter in a book I often used in university classes: Twelve Theories of Human Nature, by Stevenson, Haberman, and Wright, Oxford Univ. Press)

Our discussion of theories of human nature will now move from the ancient worlds to the 18th century with Immanuel Kant. Needless to say a lot happened in the interim. In order to make the transition of almost 2000 years, here is a brief description of a few of the major thinkers during this long period including: Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, Hobbes, Descartes, Spinoza, Hume and Rousseau. [This is a good representative sample. Notable omissions include: Bacon, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Voltaire, and Hegel.]

Augustine – St. Augustine was the most important link connecting the ancient world and the Christian medieval world. Augustine affected a philosophical synthesis of Plato, the neo-Platonists and Christianity. [Plato’s idea of the good became divine illumination; Platonic forms became ideas in god’s mind, the cave became the story of the soul’s journey to god, and more. Moreover the idea of the trinity owes much to a similar 3 fold distinction in the philosophy of the neo-Platonist Plotinus.] Despite the influence of Greek rationalism, Augustine said “I believe in order to understand.” In other words faith comes first and an exercise of will is necessary for belief, since reason by itself always fall short.

Augustine also believed that humans are sinful and that nothing we do can save us—our salvation depends on god’s grace. Thus we are predestined to be saved or not, we cannot merit salvation. This was the source of his dispute with Pelagius who argued we can save ourselves by our free acts. This is still a vexing issue in Christian theology. Augustine particularly identified sin as sexual, an idea which has had a profound influence on Christianity to this day. He also believed in a “city of god,” the ideal destiny where god’s will is fulfilled. The relationship between the church and this final destiny is ambiguous. [I think the idea is that the church helps bring about this final destiny, although if you are only saved by grace it is hard to see how this can be—which was Martin Luther’s point.]

[image error]

[image error]

The Islamic Philosophers – There were a number of prominent Islamic philosophers from the 9th through 13th centuries. They had discovered and preserved the work of Aristotle, which had been lost to the West, and their translators introduced Aristotle in Spain in the 12th century. [This would eventually make its way to Aquinas at the University of Paris.] Islam, like Christianity, assumes the authority of their religion is based on divine revelation, but this also suggests that issues of the relationship between faith and reason are prominent. The most important of these thinkers were Avicenna, who believed that god (Allah) spoke through both the intellect and imagination of Muhammad; Al-Ghazali, a Sufi mystic who emphasized mysticism rather than philosophical arguments; and Averroes, who reasserted the primacy of reason in interpreting the Koran. Each of these philosophers had considerable influence on the West.

Thomas Aquinas – While many in the Catholic Church tried to ban Aristotle, Aquinas embraced his thought and tried to synthesize it with Christianity. “Though controversial in its time, it has since become Roman Catholic orthodoxy, backed by papal authority.” Aquinas placed a greater emphasis on reason than had Augustine. Like Aristotle he believed that knowledge begins with the senses and that the intellect recognizes types or forms of things in order to categorize the world. This leads to a distinction between rational and revealed theology, the former using unaided reason to prove god’s existence, while the latter depends on the Bible and the Church.

Like Aristotle he believed we have a rational soul or structure which includes perception, intellect, reason and free will. He identifies the idea of eudaimonia with knowledge and love of god. [Is it better to know god or love him was a famous medieval dispute.] The most important virtues are the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity. Aquinas believed that immortality would involve the resurrection of the body, but tried to also maintain that the disembodied soul somehow survived between death and resurrection. Still, despite his emphasis on reason, the authority of the Church was paramount and like Augustine he was prepared to use force against dissent, arguing that heretics should be killed.

Medieval Philosophers on Human Nature

(This post is my summary of a chapter in a book I often used in university classes: Twelve Theories of Human Nature, by Stevenson, Haberman, and Wright, Oxford Univ. Press)

Our discussion of theories of human nature will now move from the ancient worlds to the 18th century with Immanuel Kant. Needless to say a lot happened in the interim. In order to make the transition of almost 2000 years, here is a brief description of a few of the major thinkers during this long period including: Augustine, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, Hobbes, Descartes, Spinoza, Hume and Rousseau. [This is a good representative sample. Notable omissions include: Bacon, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Voltaire, and Hegel.]

Augustine – St. Augustine was the most important link connecting the ancient world and the Christian medieval world. Augustine affected a philosophical synthesis of Plato, the neo-Platonists and Christianity. [Plato’s idea of the good became divine illumination; Platonic forms became ideas in god’s mind, the cave became the story of the soul’s journey to god, and more. Moreover the idea of the trinity owes much to a similar 3 fold distinction in the philosophy of the neo-Platonist Plotinus.] Despite the influence of Greek rationalism, Augustine said “I believe in order to understand.” In other words faith comes first and an exercise of will is necessary for belief, since reason by itself always fall short.

Augustine also believed that humans are sinful and that nothing we do can save us—our salvation depends on god’s grace. Thus we are predestined to be saved or not, we cannot merit salvation. This was the source of his dispute with Pelagius who argued we can save ourselves by our free acts. This is still a vexing issue in Christian theology. Augustine particularly identified sin as sexual, an idea which has had a profound influence on Christianity to this day. He also believed in a “city of god,” the ideal destiny where god’s will is fulfilled. The relationship between the church and this final destiny is ambiguous. [I think the idea is that the church helps bring about this final destiny, although if you are only saved by grace it is hard to see how this can be—which was Martin Luther’s point.]

[image error]

[image error]

The Islamic Philosophers – There were a number of prominent Islamic philosophers from the 9th through 13th centuries. They had discovered and preserved the work of Aristotle, which had been lost to the West, and their translators introduced Aristotle in Spain in the 12th century. [This would eventually make its way to Aquinas at the University of Paris.] Islam, like Christianity, assumes the authority of their religion is based on divine revelation, but this also suggests that issues of the relationship between faith and reason are prominent. The most important of these thinkers were Avicenna, who believed that god (Allah) spoke through both the intellect and imagination of Muhammad; Al-Ghazali, a Sufi mystic who emphasized mysticism rather than philosophical arguments; and Averroes, who reasserted the primacy of reason in interpreting the Koran. Each of these philosophers had considerable influence on the West.

Thomas Aquinas – While many in the Catholic Church tried to ban Aristotle, Aquinas embraced his thought and tried to synthesize it with Christianity. “Though controversial in its time, it has since become Roman Catholic orthodoxy, backed by papal authority.” Aquinas placed a greater emphasis on reason than had Augustine. Like Aristotle he believed that knowledge begins with the senses and that the intellect recognizes types or forms of things in order to categorize the world. This leads to a distinction between rational and revealed theology, the former using unaided reason to prove god’s existence, while the latter depends on the Bible and the Church.

Like Aristotle he believed we have a rational soul or structure which includes perception, intellect, reason and free will. He identifies the idea of eudaimonia with knowledge and love of god. [Is it better to know god or love him was a famous medieval dispute.] The most important virtues are the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity. Aquinas believed that immortality would involve the resurrection of the body, but tried to also maintain that the disembodied soul somehow survived between death and resurrection. Still, despite his emphasis on reason, the authority of the Church was paramount and like Augustine he was prepared to use force against dissent, arguing that heretics should be killed.

August 14, 2017

Review of Andrew Stark’s, “The Consolations of Mortality: Making Sense of Death”

Andrew Stark’s new book, The Consolations of Mortality: Making Sense of Death, addresses those who disavow belief in an afterlife. So what consolation might these non-believers find when confronting death? Stark argues that traditionally there are “four distinct ways of persuading us to accept, maybe even appreciate, the fact that we will die.” (1)The book investigates and defends of each of these four consolations. (Stark knows that science may eventually defeat death, but he says that for most of us alive today that won’t happen soon enough—perhaps not for centuries.)

The first consolation says that “death itself is actually a benign or even a good thing.” (2) Many have made such an argument. For example, Epicurus famously said that when we are alive death is not present, and when we are dead we are not alive to suffer from it. Consolation arises from understanding that we never encounter death. In addition, most existentialists claim that only if we are aware of our finitude we will feel the urgency to make the choices that define a true self. If we dawdle we won’t create our selves, so death is essential for having a self. And Buddhism tells us there is no self, so death is really nothing. If the self is just conscious experiences, then those will continue on in others after we die. So these disparate philosophies all share the idea that death is basically benign.

The second consolation states that “within mortal life as it is, we can acquire all the intimations of immortality we could ever desire.” (3)The idea is that all the good things of death’s alternative, immortality, are available now, so death doesn’t deprive us of anything. Most importantly, we want to preserve the contents of our consciousness, and we want to help shape the future. But we have consciousness and we can shape the future now. So, even if we were immortal, we wouldn’t gain anything that we don’t have now, or so the argument goes.

The third consolation states that “immortality itself would actually be an awful fate … ” (4) For example, if we have memories of all our experiences, then we might become bored after having done and seen everything. But if your oldest memories slowly vanished, and your character continually changed, then it would be as if you were periodically dying and being reborn, which is like being mortal. Now suppose your immortal self retained its memories and character, and continual novelty eliminated boredom. Yet then you might find that your self became antiquated as time moved on. And, if your memories and character continually disappear, then that hardly seems like an enviable immoral life. Perhaps we’re lucky we don’t have to be forever.

The fourth consolation claims that “life, with its losses, is itself nothing but an intimation of death.” (6) In other words, life already gives us all the bad things we associate with death, so death isn’t worse that life. For example, we dread leaving behind all the people and things that we love. But we lose homes, keepsakes, places, comforting ideas, and people we love throughout life–goodbyes are part of life. Of course death also means that our own consciousness vanishes, but that happens when we sleep too.

Stark begins his discussion with two aveats. First, he will discuss whether death is a good thing for relatively healthy people who have lived a normal lifespan of about 80 years, not whether death might be a welcome relief to suffering. And second, he won’t discuss whether lives of two hundred or two thousand years are bad; he is talking about an endless life, or at least one long enough to feel that way to the person living it. With these caveats in place the rest of the book explores whether the four consolations are sufficient.

Stark rejects the first consolation—death is benign, good for us, nothing to us—because Epicurean, existential, and Buddhist notions of self all deny “the reality that cries out for consolation; we are selves who move inexorably through time … while the moments of our lives flow incessantly through our fingers … back into the past.” (95) Rejecting these conceptions of self, he necessarily rejects the consolations they offer.

He also rejects the second consolation—mortal life provides the good things that immorality does. Technology might allow us to record our entire lives for others to view, or we might learn to be so connected with others that the continuation of their lives provides comfort. But none of this is enough. For “to believe that our mortal selves and mortal lives could even begin to give us the good things that their immortal versions would, we have to pretend that those selves and lives are bare shadows of what they actually are. We have to pretend that they are already half-dead.” (147)

Stark agrees that even the best immortality scenarios are unappealing, so he finds solace in the third consolation. Dissolving in time, subsisting in time, uniting with time, or uniting with a great ocean of being—none of this satisfies. For we “unavoidably see our selves as moving forward relentlessly in time … while the experiences of our lives flow remorselessly backward in time …” (189) So mortality is a blessing after all, if for no other reason than that immortality seems like a curse.

At this point in the text Stark addresses the issue of optional immortality, where we could live forever, but could opt out if we wanted to. But he rejects this option. If immortal life were so bad that we would want to opt out, wouldn’t that mean that such a life wasn’t a good one? Of course most mortals think their lives are worth it even they will end unpleasantly. But, according to Stark, option immortals would end their lives because they were bored, their memories prevented them from experiencing novelty, or for other reasons that made immortality unbearable. Stark doubts that option immortals would, in retrospect, value a life that had become so pointless that they wanted to end it.

Stark now investigates the final consolation—that life already gives us all the bad things that death does. Every second we move forward in time while the moments of our lives slowly slip away from us. It seems we are losing our lives every moment. But, surprisingly, he says this comforting because the alternative is being immortal and watching others die. And if events persisted longer then, when they ended, the grief over their loss would be greater than if events and experiences were more fleeting. Summarizing Stark says, “these two features of mortal existence—that our selves move together relentlessly into the future while the events of our life ceaselessly disappear into the past—are finally what bar life’s losses from ever resembling death’s. And while that fact doesn’t console me about death, it does console me about life.” (225) In short, it is good that life is fleeting.

Stark now reiterates that immortality isn’t desirable—we would either grow bored, if we remained the same, or our selves would die continually by always changing—and in this he finds consolation. As he concludes:

Either we die or we are immortal. And either our selves move relentlessly forward in time while the moments of our lives slip continually backward out of reach, or else we gain the capacities to stop moving forward in time and to keep the precious moments of our lives from flowing backward in time beyond our grasp. Of all the possibilities, none is better than the one we have. We die, and our selves move inexorably forward in time while the moments of our lives ineluctably vanish into the past. In fact, it may be the option that contains the least amount of death.

At that most fundamental level, the bundle of ego and anxiety that dwells within me feels consoled about our mortal condition. Not cheered. But consoled. I—you, we, humankind—got the best deal imaginable. (231)

Reflections – I am a transhumanist who has argued vehemently that death is an ultimate evil and that death should be optional. ( I have written almost 50 posts on various aspects of death.) So it is hard to put aside some of my preconceived ideas, and give Stark’s book a fair hearing. But I have tried. Still, while I find many of Stark’s arguments puzzling or unconvincing, there is a big problem with the book that undermines its basic argument.

The book suffers from a shocking lack of imagination. If we must either die or live forever, and if living forever is terrible, then dying is preferable. That’s his argument in a nutshell. But his conceptions of immortality are so limited. He offers but a few immortality scenarios which compare unfavorably with dying, when we cannot even comprehend what immortality might be like or how many immortality scenarios there may be. So yes, dying is better than living forever in hell or being infinitely bored, but there are an infinite number of other possibilites, many now unimaginable.

His argument against optional immortality perfectly displays this lack of imagination. Somehow the lives of beings for whom death is optional would be so bad that they would be better off without that option. Really? He feels so good about life transitoriness that he doesn’t even want the option to live longer? If he were given a death sentence and were otherwise healthy, he wouldn’t want the option to have the order rescinded? I doubt it.

People who reject the option of not dying also suffer from a lack of imagination. Since they don’t think they can have it, they reject it. This is an example of “adaptive preferences,” when you adapt your preferences to what you can get. I can’t get a date with Scarlett Johannson, so I say I don’t want her anyway. I can’t get a billion dollars, so I say I don’t want it anyway.

Death is like having a time bomb strapped to your chest; it will eventually go off, we just don’t know when. Actually its worse since we might die quite slowly. So, you really don’t want the option of having it turned off, even if you have the option of setting it off yourself if you get tired of living?

Here’s one thing you can bet your life on. When an effective anti-aging pill becomes available at the drug store … it will be popular! When the dying are given the option to take a shot which makes them completely healthy, many will take the shot!

Finally, this lack of imagination reveals itself most clearly in the book’s final lines. It is hard not to choke when reading: “Of all the possibilities, none is better than the one we have … I—you, we, humankind—got the best deal imaginable.” This is Leibniz’ assertion that this is the best of all possible worlds without Voltaire to lampoon it. But I can. Stark simply can’t believe dying and the loss it entails is “the best deal imaginable.” The only way to honestly draw this conclusion is if you can’t realistically imagine anything better. But I can. And so can many others.

August 7, 2017

Summary of Lars Tornstam on Gerotranscendence

Lars Tornstam (1943 – 2016)

My recent post, Summary of Maslow on Self-Transcendence, elicited many thoughtful comments. One reader, Dr. Janet Hively, suggested that self-transcendence is connected with aging, writing, “people gain experience and wisdom as they grow older, reaching the age for generativity toward the end of life.” She also suggested that I look into the theory of gerotranscendence, elucidated in detail by the Swedish sociologist Lars Tornstam in his 2005 book, Gerotranscendence: A Developmental Theory of Positive Aging[image error]. As Tornstam put it:

Gerotranscendence is the final stage in a natural process moving toward maturation and wisdom. The gerotranscendent individual experiences a new feeling of cosmic communion with the spirit of the universe, a redefinition of time, space, life and death, and a redefinition of self.1

Here is another definition:

The theory of gerotranscendence describes a … perspective shift from a more materialistic and rational view of life to a more transcendental [one] … leading to significant changes in the way of perceiving self, relationships with other people and life as a whole …2

According to Tornstam growing older and “into old age has its very own meaning and character, distinct from young adulthood or middle age.” In other words, there is ongoing personality development into old age. Interviews with individuals between 52 and 97 years of age confirmed this idea, and led to his theory of gerotranscendence. Gerotranscendent individuals are those who develop new understandings of: 1) the self; 2) relationships to others; and 3) the cosmic level of nature, time, and the universe. Specific changes that occur include:

Level of Self

A decreased obsession about one’s body

A decreased interest in material things

A decrease in self-centerdness

An increased desire to understand oneself

An increased desire for inner peace and meditation

An increased need for solitude

Level of Personal and Social Relationships

A decreased desire for prestige

A decreased desire for superfluous, superficial social interaction

A decreased interest in conforming to social roles

An increased concern for others

An increased need for solitude, or the company of only a few intimates

An increased selectivity in the choice of social and other activities

An increased spontaneity that moves beyond social norms

An increase in tolerance and broadmindness

An increased sense of life’s ambiguity

Cosmic Level

A decreased distinction between past and present

A decreased fear of death

An increased affinity with, and interest in, past and future generations

An increased acceptance of the mysteries of human life

An increased joy over small or insignificant things

An increased appreciation of nature

An increased feeling of communion with the universe and cosmic awareness

According to the theory of gerotranscendence, people should surrender their youthful identity in order to achieve true maturity and wisdom. This view of aging stand in contrast to the view that successful aging is a kind of perpetual youth where people try to remain active, productive, independent, healthy, wealthy and sociable. But an 80-year-old differs from their 50-year-old self, just as the latter did from their 30-year-old self. Your 80-year-old mother may not want to party, play golf, make money or be very much engaged, not because she’s sick or depressed, but because she now prefers painting, reading, writing, meditating, walking, gardening or listening to music. We are often so enamored with activity that we forget that Mom may enjoy siting in her rocking chair sometimes. None of this implies that this is the only way to successfully age, just that it is reasonable way.

Now just growing older doesn’t mean that one will become gerotranscendent, although aging does bring existential questions about death and the meaning of life to the forefront. So how does one become a gerotranscendent? The process is mostly stimulated by experiencing hardships, challenges, transitions and the losses of living, combined with continual reflection about one’s life, the life of others, and universal life. Still there are a number of obstacles to becoming a gerotranscendent including:

job preoccupation (or ego differentiation): the inability to let go of your earlier careers. Gerotranscenders are able to transcend the way that their identity was tied to their previous work.

body preoccupation (or body transcendence): the inability to let go of obsessing about bodily ailments. Gerotranscenders care about their bodies, but transcend identifying with it.

ego preoccupation (or ego transcendence): inability to let go of obsessing about the ego. Gerotranscenders transcend the ego by accepting the inevitability of death, and by living more unselfishly.

Some of the weaknesses of the theory include the fact that gerotranscendence: 1) isn’t precisely defined; 2) is limited to old age when there are some younger persons who possess the above qualities; and 3) considers gerotranscendence from an individual perspective without much consideration of the social and biological factors that influence successful aging. It also seems to conflict with the fact that “the prevalence of depression in old age” is quite high.3

Still there is substantial evidence that gerotranscendence captures the essence of aging successfully. Much of this research is described in “Theory of Gerotranscendence: An Analysis,” by Rajani and Nawaid. Some of the highlights of this research show that those who have faced life crisis have higher levels of gerotranscendence, and that there is “a positive relationship between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction.” Furthermore, research has shown “a significant correlation between the cosmic transcendence and feeling of coherence and meaning of life. Transcendence in life promotes health, harmony, healing and meaningfulness in life of older adults. Studies have also attested the fact that people who find meaning in life tend to experience better physical health.”

Reflections – I like the gerotranscendent theory of aging. It reminds me somewhat of the idea of being “weened away from life” in Thorton Wilder’s marvelous play “Our Town.” It also brings to mind this profound statement about aging from the great philosopher Bertrand Russell in his essay,”How To Grow Old.”

The best way to overcome it [the fear of death]—so at least it seems to me—is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, +without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The man who, in old age, can see his life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he cares for will continue. And if, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will not be unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carry on what I can no longer do and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.

So I do agree with Dr. Hively’s that there is a connection between age, and the wisdom to transcend the self and its concern with body, prestige, material possessions. Maslow’s self-transcendence is closely aligned with Tornstam’s gerotranscendence. This kind of wisdom and change of heart is hard to achieve without having lived and loved and suffered—the wisdom of the heart seems largely based upon time. This isn’t to say that older people are always wiser than younger people of course but, all things being equal, the achievement of wisdom is aided by time.

Yet, having said all this, I still believe that death itself is an evil that we should try to defeat. As I’ve written elsewhere, death should be optional. But for those of us who must age and die, Tornstam has shown us a noble and enlightening way to travel that road.

_______________________________________________________________________

1. “Transcendence in late life.” Generations, 23 (4), p. 11.

2. https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerotra...

3. Rivard TM, Buchanan D. National Guidelines for Seniors’ Mental Health: The Assessment and Treatment of Depression. 2006.

I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Jan Hively for introducing me to Tornstam’s work.

July 31, 2017

Nick Hughes:”Do We Matter in the Cosmos?”

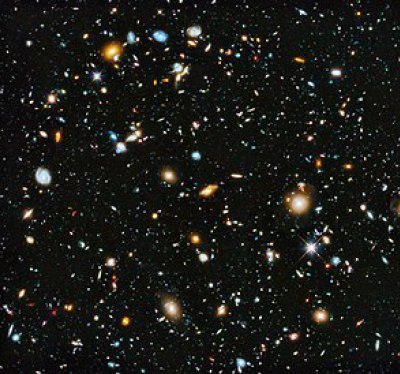

The Hubble Ultra-Deep Field image shows some of the most remote galaxies visible with present technology, each consisting of billions of stars (the image’s area of sky is very small – equivalent in size to one tenth of a full moon)[1]

Nick Hughes is a postdoctoral research fellow at University College Dublin. His recent piece in Aeon Magazine, “Do we matter in the cosmos?” begins by placing humanity in our true temporal and spatial perspective:

Travelling at the speed of light—671 million miles per hour—it would take us 100,000 years to cross the Milky Way. But we still wouldn’t have gone very far. By recent estimates, the Milky Way is just one of 2 trillion galaxies in the observable Universe, and the region of space that they occupy spans at least 90 billion light-years. If you imagine Earth shrunk down to the size of a single grain of sand, and you imagine the size of that grain of sand relative to the entirety of the Sahara Desert, you are still nowhere near to comprehending how infinitesimally small a position we occupy in space …

And that’s just the spatial dimension. The observable Universe has existed for around 13.8 billion years. If we shrink that span of time down to a single year, with the Big Bang occurring at midnight on 1 January, the first Homo sapiens made an appearance at 22:24 on 31 December. It’s now 23:59:59, as it has been for the past 438 years, and at the rate we’re going it’s entirely possible that we’ll be gone before midnight strikes again. The Universe, on the other hand, might well continue existing forever …

In response to the inconceivable immensity of space and time, Hughes poses two philosophical questions: 1) if we are so insignificant compared to the vastness of space and time, do we matter at all? and 2) if are lives are inconsequential, is despair and nihilism the proper response?

William’s Response

To answer such questions, Hughes quotes the English moral philosopher Bernard Williams:

… significance from the cosmic point of view is the same thing as having objective value. Something has objective value when it is not only valuable to some person or other, but valuable independently of whether anyone judges it to be so … valuable … from a universal perspective. By contrast, something can be subjectively valuable even if it is not objectively valuable … Williams takes it to be a consequence of a naturalistic, atheistic worldview that nothing has objective value. In his posthumous essay ‘The Human Prejudice’ (2006), he argues that the only kind of value that exists is the subjective kind …

Since, according to Williams, to be significant from the cosmic point of view is to be objectively valuable, and there is no such thing as objective value, it follows that there is no such thing as cosmic significance. The very idea, he argues, is ‘a relic of a world not yet thoroughly disenchanted’. In other words, of a world that still believes in the existence of God. Once we recognise that there is no such thing, he says, there is ‘no other point of view except ours in which our activities can have or lack a significance’. The question of what is significant from the point of view of the cosmos is incoherent: one might as well ask what is significant from the point of view of a pile of rocks.

Kahane’s Response

If Williams is right, then we are cosmically insignificance by definition. But, as Oxford’s Guy Kahane argues in ‘Our Cosmic Insignificance’ (2013), “if the naturalistic worldview does indeed rule out the possibility of anything having objective value, then it would still do so if the Universe were the size of a matchbox, or came into existence only moments ago.” Thus whether anything has objective value is independent of the size or age of the universe. (Thomas Nagel argued similarly in “The Absurd,” 1971.)

Kahane thinks that those who dismiss our significance fail to recognize that significance “is the product of two things: how valuable (or disvaluable) it is, but also how worthy it is of attention.” And how worthy of attention your life is decreases as the background against which it is measured enlarges. So your life is relatively imporant from the point of view of your family, but less so as you consider it from the point of view of your city, country, planet and eventually the univerese—from which we are surely physically and temporally insignificant.

But “significance is also a function of value” and “if the primary source of value is intelligent life, it follows that our cosmic significance depends on how much intelligent life there is out there.” If the Universe is teeming with intelligent life “then we are indeed cosmically insignificant. If, however, we are the sole exemplars of intelligent life, then we are of immense cosmic significance …”

My Response to Kahane

I’m not moved by Kahane’s argument that our cosmic significance depends much on whether other intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe. There is a sense in which the species becomes more significant if we are the only intelligent beings in the universe—no other life exists with which to share significance—but that doesn’t ameliorate my worries about my life and the universe being significant. In fact, I would prefer there is intelligent life elsewhere so that, were life on earth to die, intelligent life would remain somewhere. Moreover, you could reverse Kahane’s argument and say intelligent life becomes more significant when it is diffused throughout the universe, for then it would be more capable of affecting that universe.

However, I agree with Kahane that the size and age of the universe is irrelevant to the question of objective value. I also agree that we aren’t significant in the sense of being worthy of attention given the fact of the immensity of time and space. So I do think the cruz of the issue of whether we are significant has to do with values.

Hughes’ Response

Hughes begins by noting “that something can be significant while being neither valuable nor disvaluable.” For example, meteorologists may “say that the formation of the body of air was significant in the chain of events that led to the storm turning into a hurricane.” But there is no value judgment here about the body of air or the hurricane unless they affect sentient life. Instead, the body of air was significant in a causal sense. It “was significant because it played an important role in the tropical storm developing into a hurricane.”

Hughes argues that “it is a sense of causal, rather than value, insignificance that is central to the sense that we are cosmically insignificant.” And that’s because “causally speaking, we really are insignificant from the point of view of the whole Universe.” However, if our causal powers were infinitely larger—say we could control stars and galaxies or warp spacetime—then we wouldn’t feel as cosmically insignificant. Perhaps “the causal-powers explanation might also explain …some of the appeal of theism … through allegiance to a supremely powerful being [believers] are able to share in its power.”

Still Hughes doesn’t think our lack of causal power should lead to nihilism and despair. For one thing casual power, even if we had more of it, is merely an instrumental good. Yet what really satisfies us are things that are “intrinsically valuable to us,” even if they aren’t objectively valuable. As he concludes:

the ends that matter to us, the things that we care about most—our relationships, our projects and goals, our shared experiences, social justice, the pursuit of knowledge, the creation and appreciation of art, music and literature, and the future and fate of ours and other species—do not depend to any considerable extent on our having control over a vast but largely irrelevant Universe. We might be distinctly lacking in power from the cosmic perspective, and so, in a sense, insignificant. But having such power and such significance wouldn’t make much of a difference anyway. To lament its lack and respond with despair and nihilism is merely a form of narcissism. Most of what matters to us is right here on Earth.

My Response to Hughes

Hughes is right that we don’t need to be able to control the universe to experience intrinsic goods or subjective values. Still, without some power over myself and my environment, I can’t experience any goods. So, if our species became more powerful as well as more intellectually and morally excellent, then we would be well on our way to creating a more meaningful reality. Still I agree with Hughes that our lack of causal power, by itself, doesn’t necessarily lead to nihilism.

However, I don’t think causal insignificance is the main reason for a nihilistic view of life’s meaning. True, life might be more meaningful if we were more powerful, but I think the more pressing concern is that objective values might not exist, and subjective values might not matter.

So, do we matter in the cosmos? From sub specie aeternitatis, nothing matters. From our point of view we somewhat matter to ourselves and those close to us, but in the end, when the universe has grown cold and dark, when entropy has run its course, even our subjective values will vanish. In the end I fear that Williams has it about right.

Still I care about things nonetheless. I act as if my actions matter.