John G. Messerly's Blog, page 76

November 11, 2017

Summary of Utilitarianism

“… the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.”

~John Stuart Mill

Utility and Happiness

Jeremy Bentham (1748 – 1832), who lived in London during the Industrial Revolution, was a philosopher and social reformer who wished to alleviate the period’s dreadful living conditions. Poverty, disease, overcrowding, child labor, lack of sanitation, and miserable prison and factory conditions inspired Bentham to be an agent of social reform. He graduated from Oxford at the age of fifteen and used his prodigious gifts as social critic and legal and constitutional reformer. He became the leader of a group of individuals, including James Mill (1773 – 1836) and John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873), who espoused the principles of a moral philosophy called utilitarianism. Utilitarianism was an influential force in eighteenth and nineteenthcentury England, and Bentham personally influenced the British legislature to adopt virtually all of his proposals.

The guiding principle of Bentham’s thought was the principle of utility: human actions and social institutions should be judged right or wrong depending upon their tendency to promote the pleasure or happiness of the greatest number of people. A popular formulation of the principle is “promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number.” Bentham himself defined the principle of utility as “that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency which it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question.” Bentham was not clear as to whether the principle referred to the utility of individual actions or classes of actions, but he was clear “the party whose interest is in question” refers to “anything that can suffer.” Thus, utilitarianism was the first moral philosophy to give a significant place to nonhuman animals.

Utility measures the happiness or unhappiness that results from a particular action. Thenet utility measures the balance of the happiness over the unhappiness or, in other words, the balance of an action’s good and bad results. To compute the net utility, we subtract the unhappiness caused by an action from the happiness it causes. If an action produces more happiness than unhappiness, a positive net utility results. If it produces more unhappiness than happiness, a negative net utility results.

When deciding upon a course of action utilitarians take the following steps. First, they determine the available courses of action. Second, they add up all the happiness and unhappiness caused by each action. Third, they subtract the unhappiness from the happiness of each action resulting in the net utility. Finally, they perform that action from the available alternatives which has most net utility. (Technically, this is “act” utilitarianism, to be distinguish from another type shortly.)

If all of the available actions produce a positive net utility, or if some produce positive and some produce negative net utility, utilitarians perform the action that produces the most positive utility. If all the available actions produce a negative net utility, then they perform the one with the least negative utility. In summary, utilitarians perform that action which produces the greatest balance of happiness over unhappiness from the available alternatives. Thus, the first key concept of utilitarianism is that of maximizing utility or happiness.

It is important to note that computations of the net utility count everyone’s happiness equally. Unlike egoists, who claim that persons should maximize their own utility, utilitarians do not place their own happiness above that of others. For example, egoism recommends that we insult others if that makes us happy, but utilitarianism does not. For utilitarians, the happiness we experience by insulting them is more than balanced by the injury they endure. Analogously, robbing banks, killing people, and not paying our taxes may make us happy, but these actions decrease the net utility. Therefore, utilitarianism does not recommend any of them.

Utilitarianism is a doctrine which grips the imagination of most twentiethcentury people. Nearly all newspaper columnists, politicians, social reformers, and ordinary citizens believe that we should “make the world a better place,” “increase social justice,” “promote the general welfare,” “establish equality,” or “create the greatest happiness for the most people.” Utilitarian thinking underlies most of these phrases, and many individuals believe they are morally obligated to increase the happiness and decrease the unhappiness in the world.

The Consequences

The second key concept of utilitarianism is that we judge moral actions by the consequences they produce. The only thing that counts in morality is the happiness and unhappiness produced by an action. In other words, according to utilitarianism, the ends justify the means. It does not matter how you do itwhat means you takeas long as you increase the net utility. In most cases, as we have already mentioned, the action that utilitarians recommend mimics the recommendations of other moral theories. For instance, given the choice of telling Sue that she looks beautiful or terrible, we would usually maximize utility by telling her the former. Similarly, given the choice of granting or denying her request for a loan, we would usually maximize utility by granting her request. However, if she will probably use the money to buy drugs, become intoxicated and then beat her children, we should deny her request. On the other hand, if Bob will use our money to feed his children, we should probably loan it to him. We should always perform that action that will, most likely, increase the happiness and decrease the misery of all involved.

Since the right action depends upon our assessment of the consequences, we must know what the consequences of our actions will be. Some object that the theory fails precisely because this is not possible. And it is true that we never know absolutely what will happen as a consequence of our action. We may think the consequence of loaning Bob some money will be to cheer him up, but he might buy a gun and commit suicide! We may think the consequence of shooting Sue will be to hurt or kill her. But her subsequent paralysis might serve as the motivation for a successful writing career! In fact, any of our minuscule choices might alter human history, but we are only responsible for consequences we can reasonably anticipate. We anticipate the consequences as best we can and proceed to act accordingly. Thus, the fact that we can never be absolutely certain of the consequences of an act does not undermine utilitarianism.

We can now summarize our discussion thus far. Moral actions are those that produce the best consequences. The best consequences are those that have the most net utility, in other words, those that increase happiness and decrease unhappiness. When calculating the net utility everyone’s interests count equally. The two key concepts of utilitarianism are happiness and consequences.

Examples of Utilitarian Reasoning

Consider this complex situation. Our teacher arrives the first day of class and makes the following announcement. “Let’s not have class all semester! We will not inform the authorities and we will keep it a secret. None of us will do any work. I will not have to teach, and you do not have to study. I will give you each an ‘A,’ and you can give me excellent teaching evaluations. All of us will be happy and the net utility increased. Any questions? Class dismissed!” On the one hand, the action appears to maximize utility. No one has to work and no one is hurt. On the other hand, consider that the students are nursing students who need to learn the class material in order to function as competent nurses. If they do not learn the material, it is easy to see that they will be incompetent nurses. A society of incompetent nurses decreases the net utility and therefore, in this case, cancelling class decreases net utility.

Note again how utilitarianism differs from egoism. If the teacher and the students were egoists, and would rather skip class than work, there would be no class. On the contrary, utilitarians assume that the net utility dereases if no teaching and learning take place. Remember, utilitarians usually prescribe exactly what other moral theories do. They forbid killing, lying, cheating, and stealing and prescribe helping others, working hard, and doing good deeds.

However, there are times when utilitarianism prescribes more controversial actions. Consider euthanasia. The natural law tradition, which has exerted more influence on Western ethics than any other, maintains that it is wrong to intentionally kill innocent persons even if they are suffering. But suppose Joe Smith is terminally ill, in excruciating pain, and asks his wife, his trusted comrade of fifty years, to shoot him. Since he is more affected by his illness than anyone else, it is reasonable to assume the net utility will increase by his death. There will be some unhappiness caused by his deathhis wife will mournbut she would rather he die than suffer.

According to the utilitarian, if his wife shoots him as he requests, she does the moral thing. This analysis applies whether he killed himself or had his physician assist him. Here is a case in which what many of us believe to be immoral is, on utilitarian analysis, perfectly acceptable. In this case, the pain and suffering of the relevant parties determines the proper course of action for a utilitarian.

Examine some other controversial cases. Many cultures have practiced infanticide, the willful killing of innocent children. Often their rationale was that the lack of available food for all children required that the youngest and most dependent be sacrificed for the group. On a utilitarian analysis, this is perfectly acceptable because one death is preferable to many. The same kind of thinking might have justified the use of atomic weapons in World War II. Assuming the choice was between “x” number of deaths as a result of dropping atomic bombs and “4x” number of deaths as a result of a land invasion of Japan by American troops, the utilitarian choice was clear.

If other options were available that had a greater net utilitysay dropping the bomb in an unpopulated field as a show of forcethen that action should have been performed. We may object that in the case of infanticide or atomic bombs, “innocence” has a moral significance which overrides the utilitarian conclusion. But, according to the utilitarian, maximizing utility determines the proper action.

4. Mill and Utilitarianism

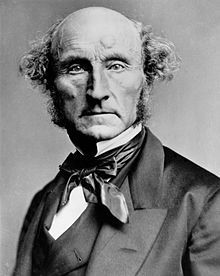

John Stuart Mill, a protegé of Bentham and Mill’s father James Mill, became the most eloquent spokesman for utilitarianism. Mill was one of the most fascinating individuals in the history of Western philosophy. A child prodigy, he studied Greek and mathematics from the age of three and read all of Plato’s dialogues in Greek by his early teens. Mill’s classic work, Utilitarianism, sets forth the major tenets of the doctrine and reformulates many of Bentham’s ideas.

In Chapter 2 of Utilitarianism, Mill noted that utilitarianism had concentrated upon the quantity of pleasure but it did not address any qualitative differences in pleasure. Mill feared the emphasis on pleasure would reduce utilitarianism to hedonism, a doctrine he considered “worthy of swine.” He argued that some pleasures are qualitatively better than others, that the “higher” mental pleasures are superior in quality to the “lower” physical pleasures. How do we know this? Those who have experienced both kinds of pleasure show a decided preference for the higher ones, Mill stated, and this demonstrates that the higher pleasures are preferable. But are they really?

Mill admitted that nonhuman animals sometimes appear happier than human beings, but this is misleading. To paraphrase his famous quote: better an unhappy human than a happy pig; better a dissatisfied Socrates than a satisfied fool. If the fool or pig disagree, Mill continued, it is only because they have not experienced higher pleasures. The major difficulty with Mill’s view was its appeal to a standard other than happiness in order to make a distinction between kinds of happiness. But if there is another value besides happiness, then we have abandoned the idea that happiness is the only good.

In Chapter 4, Mill began by defining the desirable end of all human endeavors. The only thing desirable is happiness, and all other valuable things are only means to the end of happiness. Bentham had wavered as to whether happiness or pleasure was the only good. In this more lucid version, happiness replaced pleasure as the moral standard. In this way, Mill avoided the charge that utilitarianism is hedonism in disguise.

Mill then proceeded to offer his famous “proof” of utilitarianism. We prove that something is visible by the fact that people see it and we prove that something is audible by the fact that people hear it. In the same way “the sole evidence it is possible to produce that anything is desirable, is that people do actually desire it.” For Mill, the simple fact that people desire happiness establishes it as desirable.

Of course merely because people desire happiness, the opponents of Mill replied, does not show that it is the only desirable thing. Mill answered that other goods like virtue or wealth are really means to happiness. But his opponents pointed to another difficulty with Mill’s proof. It rests upon a confusion between what people do desire and what they ought to desire. There mere fact that people actually desire happiness does not show, so critics of utilitarianism maintained, that happiness really should be desired. But Mill maintained that no other proof of the desirability of happiness was possible than to point out the fact that humans naturally desire it.

Mill also makes it clear that only the consequences matter. You do the right thingmaximize utilityby saving your friends from drowning whether you do it for love or money. After all, the net utility is merely the sum of individual utilities, and if you are happy, all the better. Why, Mill wonders, should we do our duty if it makes us unhappy? Amarillo Slim, a famous professional poker player, expressed Mill’s position succinctly when he replied to someone who criticized his occupation: “Would the world really be better off if I was miserable pumping gas?”

Act and Rule Utilitarianism

Let us now turn to the question of whether utilitarians consider individual actions or classes of actions when deciding to maximize utility. Neither Bentham or Mill addressed this question, but contemporary philosophers have made a distinction between two types of utilitarians. Act utilitarians ask “which individual action, from the available alternatives, maximizes utility?” Rule utilitarians ask “which rule, when generally adopted, maximizes utility?” Oftentimes there is no difference between the prescriptions of the two types of utilitarians; at other times, there is a great difference. We will illustrate this basic difference with a number of examples.

Imagine that we are stopped at a red traffic light at three in the morning. Looking both ways as far as possible down the road we are about to cross, we see no cars in sight. It suddenly occurs to us that we should not remain stopped. Why? Because by running the red light we will save our mother a minutes worry, the country a little gas and pollution, and ourselves a little annoyance. Furthermore, we will get home sooner rather than later, decreasing the possibility that we or others will be injured in an accident. The net utility will be increased by our action and so, according to an act utilitarian, we should do it.

Contemplate another example. The President has requested that we turn down our thermostats to save heating oil. Unfortunately, our grandmother’s arthritis is aggravated by a cold apartment. We reason as follows: if grandother keeps her heat high, she will not contribute significantly to the country’s oil problem. Moreover, she will feel much better and so will we. She will be more comfortable physically, and we will not have to listen to her complain about arthritis, government corruption, or greedy oil companies. Her physical state positively affects her mood. Her good mood makes us and our family happier. An act utilitarian advises grandmother to keep her heat on high.

Finally, ponder this simple case. The sign on the college lawn says “keep off the grass.” Officials at the college have determined that the college looks better, and attracts more students, with nice lawns. Now suppose you are in a hurry to complete some task that will make you and others happier, assuming that you complete it sooner rather than later. Assume also that cutting across the lawn saves a significant amount of time. Again, act utilitarians reason that their little footprints do not make a significant difference in the appearance of the college lawn, and since we can make so many other people happy by cutting across the lawn and completing our task sooner rather than later, we should do so.

Now consider these three cases from a rule utilitarian perspective. In every case the rule utilitarian asks, “what if we made a general rule of these actions?” In other words, “what if everybody did these?” (This is the Kantian question, but Kant wants to know about the consistency, not the consequences, of rules.) Rule utilitarians want to know if rules maximize utility or bring about good consequences. Take the first case. It should be clear that if everyone disobeys traffic lights the consequences are disastrous. Given the choice between a rule that states “always obey traffic lights” or one that says “sometimes obey traffic lights,” the first rule, not the second one, maximizes utility. Rule utilitarians argue that the net utility will decrease if persons are more selective about their obedience to rules. They might begin to disobey traffic lights at 11 p.m., whenever there are no cars in sight, or whenever they think they can beat the oncoming cars!

A comparable analysis applies in the other two case. The rule, “do not turn up your thermostat to save heat for the country” maximizes utility compared with the rule, “turn up your thermostat if you’re cold despite what the President requests.” Similarly, the rule “do not walk on the grass” maximizes utility compared with the rule, “do not walk on the grass except when you are in a hurry.” Therefore, in all of these cases act and rule utilitarians prescribe different actions. Act utilitarians perform the action that maximizes the utility, rule utilitarians act in accordance with the rule that, when generally adopted, maximizes utility. They both believe in maximizing utility but are divided as to whether the principle of utility applies to individual acts or general rules.

The issue between act and rule utilitarians revolves around the question, “is the moral life improved by practicing selective obedience to moral rules?” The act utilitarians answer in the affirmative, the rule utilitarians in the reverse. Rule utilitarians believe the moral life depends upon moral rules without which the net utility decreases. Act utilitarians believe that whether moral rules are binding or not depends upon the situation. Thus, act utilitarians treat moral rules as mere “rules of thumb,” general guidelines open to exceptions, while rule utilitarians regard moral rules as more definitive. We will look at problems for both formulations of utilitarians in a moment. Let us now look at the most general problems for utilitarianism.

6. The Problems with Happiness

A first difficulty with using happiness as the moral standard is that the concept of the net utility implies that happiness and unhappiness are measurable quantities. Otherwise, we cannot determine which actions produce the greatest net utility. Bentham elaborated a “hedonistic calculus” which measured different kinds of happiness and unhappiness according to their intensity, duration, purity, and so on. Some say that it is impossible to attach precise numerical values to different kinds of happiness and unhappiness. For example, it may be impossible to assign a numerical value to the happiness of eating ice cream compared to the happiness of reading Aristotle. Still, we can prefer one to the other, say ice cream to Aristotle, and, therefore, we do not need precise numerical calculations to reason as a utilitarian.

A second difficulty is that it may be impossible to have “interpersonal” comparisons of utility. Should we give Sue our Aristotle book or Sam our ice cream? Does Sue’s reading pleasure exceed Sam’s eating pleasure? There is no doubt that different things make different people happy. For some, reading and learning is an immense joy, for others, it is an exceptional ordeal. But we can still maximize utility. We should give Sue the book and Sam the ice cream, or if we can only do one or the other, we make our best judgment as to which action maximizes utility. Besides, we agree about many of the things that makes us happy and unhappy. Everyone is happy with some wealth, health, friends, and knowledge. Everyone becomes unhappy when they are in pain, hungry, tired, thirsty, and the like. We do not need precise interpersonal comparisons of utility to reason as a utilitarian.

Despite Mill’s proof of utilitarianism, a third difficulty concerns doubts about the overriding value of happiness. Is it more valuable than, for example, freedom or friendship? Would we sacrifice these for the net utility? We would maximize utility by dropping “happiness pills” into everyone’s drinks, but this doesn’t mean we should do it. Shouldn’t individuals be free to be unhappy? And if we believe this, isn’t that because we think freedom is a value independent of happiness? We might even refuse to take happiness pills even if given the choice, because they limit the freedom to be unhappy.

Or suppose we promise to meet a friend but, in the meantime, some little children ask us to play with them. It may be that playing with the children maximizes utility. After all, our friend is popular and will probably make other arrangements after waiting a while. But maybe we should keep our promise. Maybe promisekeeping or the friendship it engenders are valuable independent of the total happiness. These examples suggest that happiness is not the only value.

Most contemporary utilitarians have abandoned the idea that happiness is the only value. They have retreated from claims about absolute values to claims about individual preferences. (This was Gauthier’s argument in Chapter 4.) The type of utilitarianism which argues that we should maximize an individual’s subjective preferences is called preference utilitarianism. The problem with this type of utilitarianism is that some subjective preferences might be evil.

A fourth difficulty is that utilitarianism considers only the quantity of utility not its distribution. Should you give $100 to one needy person or $10 each to ten needy persons? The second alternative might be better even if the first one creates the most utility. Concerns with the total happiness have troubled many commentators and some have suggested that we consider the “average utility.” But this version has problems too. Do we want a society where the average income is very highsay $1,000,000but many people live in destitute poverty, or one where the average income is much lowersay $30,000but no poverty exists? In fact, the idea of the welfare state assumes that money has a diminishing utilityit doesn’t benefit the rich as much as the poorand thus the enforced government transfer of money from the rich to the poor is justified. But isn’t it possible that individuals who work hard for their money deserve it, whether or not forcefully taking it maximizes utility? This analysis reveals another fundamental difficulty with utilitarianism. Everything is sacrificed to the net utility. But should all moral acts be judged by the consequences they produce?

The Problem with Consequences

The most important difficulty for utilitarianism is that it emphasizes consequences exclusively. Utilitarians claim that “the ends always justify the means,” and therefore we can do anything to maximize utility as long as the consequences are good. For example, imagine that our neighbor opens our mail every day before we get home and then meticulously closes and replaces it with such skill that we cannot tell it has been opened. He derives great satisfaction from this activity and we never find out about it. When we are out-of-town and give him the key for emergencies, he rummages through our mail and personal effects, carefully replacing them before we return. He finds these activities immensely pleasurable, we never find out, and the net utility increases. An act utilitarian says he acts morally. But isn’t there something wrong here? Should our privacy be sacrificed to the net utility?

Act utilitarians are willing to sacrifice privacy, rights, or even life itself to the net utility. Imagine a country sheriff who has been charged with finding the perpetrator of a recent homicide. The powerful elite of the town inform the sheriff that if he does not find the murderer, they will kill the inhabitants of the local American Indian reservation, since they believe an American Indian committed the crime. The sheriff has no idea who committed the murder, but he does believe that framing some innocent individual will avert the ensuing riot which will almost certainly kill hundreds of innocent people. In other words, the sheriff maximizes utility by framing an innocent victim.

Now according to an act utilitarian, this analysis is certainly correct. Nonetheless, most individuals think something is terribly mistaken with framing innocent persons. But why? If we don’t frame the innocent victim, hundreds of people will die. True, something may foul our plan. For example, someone may find out that the victim has been framed. But this just repeats a critique of utilitarianism that we never know the consequences for certain which we have already answered. All the sheriff can do is the best he can. That is all anybody can do. And remember, if we do not frame the innocent victim, the blood of hundreds of other innocent victims is on our hands.

This is a situation in which a moral theory conflicts with our moral intuition. We ordinarily assume we shouldn’t frame innocent people. But maybe that is just ordinarily? And this is an extraordinary situation. Nevertheless, most of us think something is terribly wrong here. Maybe the theory can be reformulated to handle these cases?

8. The Problems with Rule Utilitarianism

Problems of this sort are precisely what led to the formulation of rule utilitarianism. Rule utilitarians claim that the rules “never violate a person’s privacy” or “never frame innocent persons” maximize utility compared with the rules “sometimes violate a person’s privacy” or “sometimes frame innocent persons.” But rule utilitarianism is beset by its own unique difficulties.

A first problem is whether utilitarian rules allow exceptions. To illustrate, consider that the moral rule “never kill the innocent” maximizes utility compared to the rule “always kill the innocent,” and thus a strict rule utilitarian adopts the former, from these two choices, without exceptions. But the rule “never kill the innocent except to save more innocent lives” might maximize the utility better than either of the other two rules. If it did, a strict rule utilitarian would adopt it without exceptions. But this is not the best possible rule either. The best possible rule is “never kill innocent people except when it maximizes the utility to do so.” But if that is the best possible rule, how is rule utilitarianism any different from act utilitarianism?

The issue is further complicated by the fact that different interpretations of rule utilitarianism exist. In what we will call a strong rule utilitarianism, moral rules have no exceptions. In what we will call a weak rule utilitarianism, rules have some exceptions. The more exceptions we build into our moral rules, the weaker our version of rule utilitarianism becomes. But if we build enough exceptions into our moral rules, rule utilitarianism becomes indistinguishable from act utilitarianism.

Think about the traffic light again. A strict rule utilitarian says “do not go through traffic lights” because, compared with most other rules, this rule maximizes utility. If we compare it with the rules “go through traffic lights when you want to,” or “go through traffic lights if you’re pretty sure you won’t cause an accident,” it fares well. But compare it with the rule :”do not go through traffic lights except in situations where it maximizes the utility to do so.” A rule utilitarian should find this rule acceptable because it is the best conceivable rule. But if rule utilitarians act according to this rule, then their theory is indistinguishable from act utilitarianism.

Strong rule utilitarians can avoid this problem by not allowing exceptions to rules. They argue that if we make exceptions in individual cases, then the net utility will decrease because individuals naturally tend to be bias because they make exceptions that favor themselves. The act utilitarians counter by calling rule utilitarians superstitious “rule-worshipers.” If it maximizes the utility to do “x,” then why obey a rule that prescribes “y?” This issue could be resolved with some modified rule utilitarianism that would allow exceptions but not collapse into the situational character of act utilitarianism. The attempt to formulate such rules completely has met with mixed success.

A second problem with rule utilitarianism is that it tells us to abide by the rules that maximize the utility if generally accepted. Suppose they aren’t generally accepted? If we still abide by them we make useless sacrifices. Imagine that public television is conducting their annual fundraising campaign. A rule utilitarian reasons that if everyone abides by the rule “give what you can to public television,” the net utility will be increased. But suppose no one else contributes and public television goes broke? Then the individual that contributes has made a useless sacrifice. These objections show that many difficulties plague rule utilitarianism.

Conclusion

The two key concepts in utilitarian thinking—happiness and consequences—are problematic. Whereas deontology places moral value on something intrinsic to the agent his/her intentions utilitarianism places moral value on something extrinsic to the agent the action’s consequences in terms of happiness produced. For deontologists, the end never justifies the means; for utilitarians the end always justifies the means. Note that both theories are based on a principle. For Kant, the principle is the categorical imperative and for Mill it is the principle of utility. The ultimate principle in natural law is to promote the good or natural and in contract theory it is to do what is in our own interest. But maybe all of these theories are too formal and precise. Is there any theory of moral obligation that is less reliant on objective, abstract, moral principles and more contingent upon subjective, concrete, human experience?

November 9, 2017

What To Do About “Fake News”

In a recent post I expressed worry that the objective findings of the Mueller investigation won’t matter because right-wing media won’t report them, and instead create their own false narratives. This leads Trump’s followers to actually believe these lies—its Clinton whose connected to the Russians, Mueller is a Democrat, etc.—which then puts pressure on Republicans to act based on these lies, and the politicians, fearing primary challenges, then either pretend to believe the lies in order to get re-elected, or are themselves so crazy that they actually believe the lies. So what do we do?

There are only 2 basic strategies I can think of: 1) educating the populace so they don’t believe the lies; or 2) keeping the lies and misinformation from the people in the first place. Thirty years of university teaching, including at some prestigious universities, convinces me that the first strategy is problematic. Teach critical thinking, logic, and encourage students to take courses in the mathematical and natural sciences by all means, but reptilian brains full of cognitive biases leftover from our evolution naturally rebel. We are just so programmed to fall for bullshit. Better to mandate the teaching of critical thinking to young students, especially as a tonic to the religious indoctrination which typically undermines critically thinking for a lifetime.

The second strategy was once relatively successful in the USA when media was governed by the fairness doctrine. The Fairness Doctrine was a policy of the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC), introduced in 1949, that required the holders of broadcast licenses both to present controversial issues of public importance and to do so in a manner that was—in the Commission’s view—honest, equitable, and balanced. The FCC eliminated the policy in 1987 and removed the rule that implemented the policy from the Federal Register in August 2011. This set the stage for the rise of Fox news and right-wing talk radio that has coarsened political discourse and undermined truth.

Recently, Finland has made news for its relatively successful effort in combatting fake news. They have combined the approaches above, emphasizing both government action and the teaching of critical thinking in the excellent schools. Apparently they have been more successful than anyone else so far.

November 7, 2017

What If Everyone Had Guns?

I have to chuckle at President Trump and the Republicans claim that tougher gun laws won’t stop mass shootings. That’s weird, they do so in every other country in the world with tough gun laws. In Japan, England and many other countries almost no one dies of gun violence because … THEY DON’T HAVE GUNS! In the last 50 years more Americans have died of gun violence in the US than were killed in all the wars America ever fought!

And the idea that more guns is the solution is self-evidently absurd. Let’s follow that argument to its logical conclusion. Ok, everyone should own a gun. No, not good enough, you must carry it with you. Ok, everyone should always carry a loaded gun. No, not good enough, you might be shot before you pull it out of your holster. Ok, everyone should always carry a loaded gun pointed at others ready to fire. No, not good enough, the bad guy might have an assault rifle. Ok, everyone should always carry an assault rifles pointed at others ready to fire. Heck, why not make it illegal to go outside without an assault rifle? Then every person you in the grocery store, church, casino or bar, will be pointing their rifles at you and you at them.

Now think about it. Do you feel safer in such a country? Or would you feel safer in England where there are about 50 gun killings annually? Or in Japan where in 2014 there were just six gun deaths!

In 2014 there were 33,599 gun deaths in the US.

November 6, 2017

Summary of Kant’s Ethics

Kant’s Deontological Ethics

1. Kant and Hume

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), called by many the greatest of modern philosophers, was the preeminent defender of deontological (duty) ethics. He lived such an austere and regimented life that the people of his town were reported to have set their clocks by the punctuality of his walks. He rose at 4 a.m., studied, taught, read, and wrote the rest of the day. He was an accomplished astronomer, mathematician, metaphysician, one of the most celebrated epistemologists and ethicists of all time, and, in many ways, the crowning figure of the Enlightenment. During the Enlightenment, European civilization celebrated the idea that human reason was sufficient to understand, interpret, and restructure the world. Perhaps the greatest rationalist ever, Kant defended this view in both his epistemology and ethics. His motto was “dare to think.”

To understand Kant, we might briefly consider his immediate predecessor David Hume (1711-1776). Hume had awakened Kant “from his dogmatic slumber,” forcing him to reconsider all of his former beliefs. Hume’s skepticism had challenged everything for which the Enlightenment stood, and he was, perhaps, the greatest and most consistent skeptic the Western world had yet produced. He argued that Christianity was nonsense, that science was uncertain, that the source of sense experience was unknown, and that ethics was purely subjective.

Hume believed that moral judgments express our sentiments or feelings and that morality was based upon an innate sympathy we have for our fellow human beings. If humans possess the proper sentiments, they were moral; if they lack such sympathies, they were immoral. Thus, Hume continued the attack on authority and tradition—an attack characteristic of the Enlightenment—but without the Enlightenment’s faith in reason. In particular, he criticized the view that morality was based upon reason which, according to Hume, can tell us about facts, but never tell us about values. In short, reason is practical; it determines the means to some end. But ends come from desires and sentiments, not from reason. In vivid contrast to natural law theory, our ends, goals, and purposes depend upon our passions and, consequently, no passions are irrational. Hume made these points in a few famous passages: “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions…[Thus]…Tis not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger.”

Hume’s skepticism stunned Kant. What of the Enlightenment’s faith in reason? If desire preceded reason, and desires cannot be irrational, then Enlightenment rationalism was dead. How can we reestablish faith in reason? How can we show that some passions and inclinations are irrational? In his monumental work The Critique of Pure Reason, Kant attempted to elucidate the rational foundations of both the natural and mathematical sciences, defending reason against Hume’s onslaught. He then turned his attention to establishing a foundation for ethics in The Critique of Practical Reason. If morality were subjective, as Hume thought, then the concept of an objective moral law was a myth. And if no passions were irrational, then anything goes in morality. In essence, Kant needed to answer Hume’s subjectivism and irrationalism by demonstrating the rational foundations of the moral law.

2. Freedom and Rationality

Kantian philosophy is enormously complex and obscure. Yet, Kant’s basic ideas are surprisingly simple. His most basic presupposition was his belief in human freedom. While the natural world operates according to laws of cause and effect, he argued, the moral world operates according to self-imposed “laws of freedom.” We may reconstruct one of his arguments for freedom as follows:

Without freedom, morality is not possible.

Morality exists, thus

Freedom exists.

The first premise follows if we consider how determinism undermines morality. (See chapter 2) The second premise Kant took as self-evident, and the conclusion follows logically from the premises. But where does human freedom come from? Kant believed that freedom came from rationality, and he advanced roughly the following argument to support this claim:

Without reason, we would be slaves to our passions

If we were slaves to our passions, we would not be free; thus

Without reason, we would not be free.

Together, we now have the basis upon which to cement the connection between reason and morality.

Without reason, there is no freedom

Without freedom, there is no morality, thus

Without reason, there is no morality.

Kant believed moral obligation derived from our free, rational nature. But how should we exercise our freedom? What should we choose to do?

3. Intention, Duty, and Consequences

Kant began his most famous work in moral philosophy with these immortal lines: “Nothing in the world—indeed nothing even beyond the world—can possibly be conceived which could be called good without qualification except a good will.” For Kant, a good will freely conformed itself and its desires to the moral law. That is its duty! Nevertheless, the moral law does not force itself upon us, we must freely choose to obey it. For Kant, the intention to conform our free will to the moral law, and thereby do our duty, is the essence of morality.

The emphasis on the agent’s intention brings to light another salient issue in Kant’s ethics. So long as the intention of an action is to abide by the moral law, then the consequences are irrelevant. For instance, if you try valiantly to save someone from a burning building but are unsuccessful, no one holds you responsible for your failure. Why? Because your intention was good. The reverse is also true. If I intend to harm you, but inadvertently help you, I am still morally culpable. Kant gave his own example to dramatize the role intention played in morality. Imagine shopkeepers who would cheat their customers given the opportunity, but who do not only because it is bad for business. In other words, the shopkeepers do the right thing only because the consequences are good. If they could cheat their customers without any repercussions, they would do so. According to Kant, these shopkeepers are not moral. On the other hand, shopkeepers who gave the correct change out of a sense of duty are moral.

The emphasis on the agent’s intention captures another important idea in deontology, the emphasis on the right over good. Right actions are done in accordance with duty; they do not promote values like happiness or the common good. Kant makes it clear that dutiful conduct does not necessarily make us happy. In fact, it often makes us unhappy! We should do the right thing because it is our duty, not because it makes us happy. If we want to be happy, he says, we should follow our instincts, since instinct is a better guide to happiness than reason.

But morality cannot rest upon passions. If it did, morality would be both subjective and relative. For ethics to be objective, absolute, and precise—to be like the sciences—it needs to be based upon reason. Only the appeal to the objectivity of reason allows us to escape the subjectivity of the passions. In summary, a good will intends to do its duty and follows the moral law without consideration of the consequences.

4. Hypothetical Imperatives

But what exactly does reason command? We have already seen how reason commands actions given antecedent desires. If we want a new car, then reason tells us the various means to achieve this end. We can save or borrow the money, pray, enter a raffle, call our mother, or steal a car. But whatever we do, reason only tells us how to pursue the end; it does not tell us which ends are worth pursuing. Commands or imperatives of this sort, Kant called hypothetical imperatives, since they depend upon some desires or interests that we happen, hypothetically, to have.

Kant distinguished between two types of hypothetical imperatives. The type we have been discussing so far, what he called “rules of skill,” demand a definite means to a contingent (dependent) end. There are also what Kant called “counsels of prudence,” which are contingent means to a definite end. Kant recognized that happiness was a common end or universal goal for all individuals, but that the means to this end was uncertain. For example, we may think that getting a new car or losing weight will make us happy, but when we get the new car or figure we may still be unhappy. Even though the end is definite, the means to the end are not. Thus, there are no universal hypothetical imperatives because either the ends are contingent or the means to the end are uncertain.

5. The Categorical Imperative

Does reason command anything absolutely? In other words, does reason issue any imperatives which do not depend upon contingent ends or un-certain means? Hume had claimed that reason did not command in this way and that any rational commands depend upon our passions. But if absolute commands exist—commands independent of personal taste—then the essence of the moral law is revealed.

If we think about any law—say temporal relativity—we recognize immediately that law is characterized by its universal applicability. So that, if relativity theory is true, then time is relative to motion everywhere through-out the universe. Similarly, the distributive law of mathematics applies no matter what numbers we insert into it or what planet we are on. Mundane physical laws are similar. Suppose we are asked about the post-operative effects of aspirin. We do not know about the anti-clotting effects of aspirin and believe it should be given after operations. In this example, it seems clear that the truth of the matter does not depend upon us; it depends upon laws governing how human bodies respond to aspirin. Kant believed that the moral law was like this. If there really is a reason why killing innocent people is wrong, then the reason applies universally. It doesn’t matter that we want, desire, or like to kill innocent persons; we violate the moral law by doing so.

Of course, we can say that killing innocent people does not violate the moral law just as we can say that time is not relative to motion, that the distributive law works only on Monday, or that aspirin should only be given after operations. But our statements do not affect these laws; rather, the laws determine the truth of our statements. Kant held that a universally applicable moral law governs human behavior and can be discovered by human reason.

Kant had seized upon the idea of universalization as the key to the moral law. He called the first and most famous formulation of the moral law the categorical imperative: “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” A maxim is a subjective principle of action which reveals our intention. To universalize a maxim is simply to ask, “what if everybody did this?” We should act according to a principle which we can universalize with consistency or without inconsistency. By testing the principle of our actions in this way, we determine if they are moral. If we can universalize our actions without any inconsistency, then they are moral; if we cannot do so, they are immoral. Ponder these simple examples. There is no logical inconsistency in universalizing the maxim, whenever we need a car we will work hard to earn the money. However, there is something inconsistent about universalizing the maxim, whenever we need a car we will steal it.

Kant advanced five formulations of the same imperative. Another famous formulation was: “Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, always as an end and never merely as a means.” This formulation introduces us to the idea of respect for persons. Individuals are not a means to an end; we should not use people. Instead, they are ends in themselves with their own goals and purposes. Whether we use ourself or others, we violate the imperative if we treat any human being without dignity and respect. Certainly it is true that we all use people to an extent. We use physicians, teachers, nurses, and auto mechanics to get what we want. But there is a difference between paying persons for services and using them merely as a means to your end. In the latter case, we disregard their inherent worth.

6. Perfect and Imperfect Duties

The categorical imperative commands actions in two different ways. It specifically forbids or requires certain actions, and it commands that certain general goals be pursued. The former are called perfect duties, the latter imperfect duties. Perfect duties include: do not lie, do not kill innocent persons, and do not use people. We should never perform these actions! Imperfect duties include: helping others, developing our talents, and treating others with respect. These duties are absolute, but the way we satisfy them varies. There is flexibility in how we help others, treat them with respect, or develop our talents. When we universalize a maxim that violates a perfect duty, we will an inconsistent world. When we universalize a maxim that violates an imperfect duty, we will an unpleasant world.

7. Kant’s Examples

Kant provided four examples—making false promises, committing suicide, developing our talents, and helping others—to demonstrate how the categorical imperative governs human conduct. Consider Kant’s first example, making a false promise. Can we consistently will the principle, “whenever in need of money make a false promise to get it?” We cannot, since a world where everyone acts according to this maxim would be inconsistent. This is easy to demonstrate. In such a world: 1) false promises would be useful because there would be persons to believe them; and 2) false promises would not be useful because, in a short time, nobody would believe them. Such a world is not even possible. On the one hand, it would contain the necessary preconditions for false promises to be successful—people to believe our lies—and, on the other hand, the normal and predictable result of universal false promising would be that no lies would be believed. So it is not just that this world is unpleasant; it is logically impossible!

Consider Kant’s second example. Imagine that we are depressed and con-template suicide. Our principle of action is “whenever we are depressed we will commit suicide.” Now try to universalize a world in which everyone does this. What would it be like? In such a world: 1) people would exist to commit suicide; and 2) people would not exist to commit the suicides they intend. Such a world is not logically possible. On the one hand, it would contain the necessary preconditions of suicide—live people to commit the act—and, on the other hand, the normal and predictable result of universal suicide would be that everyone would be dead. It is easy to think of other examples. Worlds where everyone were killers or bank robbers would be logically impossible in the same way. Kant had demonstrated, at least to his own satisfaction, that these actions were both immoral and irrational!

If we consider the same two actions—making false promises and suicide—in terms of the second formulation of the categorical imperative, we discover that they violate it as well. If we make a false promise to someone, then we use that person as a means to our end. Analogously, if we commit suicide, then we use ourself to achieve some end. When universalization of a maxim is inconsistent or when we use ourself or others, we violate perfect duties. Kant believed that telling the truth and not committing suicide exemplify perfect duties. There are no exceptions to them.

Kant believed we have a moral obligation to develop our talents, which was his thirdexample. Suppose we are comfortable and prefer to indulge ourselves rather than develop our talents. We act according to this maxim: “since we are reasonably well-off, we won’t develop our talents.” Upon reflection, we recognize that failure to develop our talents violates a duty and could not be universalized consistently. For if everyone failed to develop their natural talents, they would not fulfill the purpose for which those talents exist.

Furthermore, he might have added, nothing useful would be accomplished in human society without the development of talent. Yet, Kant never claimed such a world was impossible, unimaginable, or logically inconsistent. Rather, rational persons cannot will this maxim to be a universal law without disastrous and unpleasant results.

Similarly, we have a moral obligation to help others, Kant’s fourth example. Suppose we are prosperous and care little for others. We violate a duty by not helping others, and we cannot universalize the maxim. For we may need the benefit of others in the future. Again, Kant did not say this world was impossible, but he did not think any rational person desired such a world.

If we consider the same two actions—developing our talents and helping others—in terms of the second formulation of the categorical imperative, we discover similar difficulties. When universalization of a maxim has disastrous results or when we fail to treat ourselves and others as ends, we violate imperfect duties. Therefore, developing our talents and helping others are imperfect duties. They are absolute duties, but the specific means by which we satisfy these duties are open.

We may say that the categorical imperative is the formal representation of the moral law to the human mind. It commands human conduct independent of context. Compare the categorical imperative, as an abstract formulation of the moral law, to the distributive law in mathematics. This law states: a(b+c)=ab+ac. As stated, the principle is merely formal and without content. We give it content by putting numbers into the equation. The categorical imperative functions similarly in the moral domain. There, we place the maxim that operates in the moral context (situation) into the formulation to determine what to do. When we want to steal a library book or trash the sidewalk we ask, “what if everybody did this?” Recognizing the negative implications of our maxim, we see how it violates the categorical imperative. Theoretically, we may place any principle into the formulation to determine its morality. Those who do not test their maxim in this manner, turn away from the moral law.

8. Contemporary Applications

Let us consider a contemporary application of deontology to medical ethics. The emphasis on truth-telling precludes lying by health-care professionals to their patients or research subjects. Imperfect duties such as beneficence are straightforward, but how we help others is vague. The permissibility of euthanasia is also problematic. On the one hand, we may be able to universalize some forms of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide, but, on the other hand, suicide is unequivocally forbidden. Thus, the permissibility of euthanasia depends in large part on how suicide is interpreted. The respect for persons notion is equally vague, since it is not clear what it entails. Again, we are prohibited from treating ourselves or others as means, yet we should respect our’s and others’ autonomy.

9. Problems with Universalization

Despite its initial plausibility, universalization is problematic. For one thing, it is easy to universalize immoral maxims. Suppose we act according to the maxim, “Catholics should be exterminated.” There is no problem universalizing this maxim, in fact, we hope it does become universal if we really hate Catholics. The maxim “always kill Catholics,” just like the maxim “never kill Catholics,” can be universalized without contradiction by consistent Catholic-haters. Therefore, the test for universalization cannot discriminate between the two actions. We can also universalize a non-moral action like, “whenever we are alone, we sing.” We may universalize this without contradiction, but that does not mean it is moral.

It is also easy enough to think of non-moral and supposedly moral maxims which cannotbe universalized. We cannot universalize maxims like, “whenever hungry, go to Sue’s diner,” or “whenever we want to go to school, go to our school.” It is not possible foreveryone to go Sue’s diner or our school. More significantly, many moral actions cannot be universalize. We cannot universalize the maxim, “sell all you have and follow the Lord.” If everyone is selling, no one is buying! We cannot even universalize a simple maxim like, “put other people first,” since everyone cannot be last! (The so-called altruist’s dilemma.) So the test for universalization does not seem to adequately distinguish moral from immoral actions.

This brings to light a related difficulty. What maxim must we test for universalization? Maxims vary according to their generality or specificity. Kant tested very general maxims for universalization. “We cannot lie to achieve an end.” Suppose we made the maxim more specific. “We cannot lie except to save innocent people from murder.” This maxim is universalizable and spares us from telling the truth to inquiring murderers who ask the whereabouts of their intended victims. We could make the maxim even more specific. “We cannot lie except to save innocent people from murder and to spare people’s feelings.” The problem is that as maxims become more specific, more questionable maxims become capable of consistent universalization. Eventually, we would be testing very specific maxims. Suppose a bald, bearded, philosopher professor, Horatio Rumpelstiltskin, was about to steal a book from the college library on Thursday at 12:22 p.m. He would discover, upon careful examination, that he could universalize a world where all so named and described individuals stole books at precisely that time. If maxims become this specific, universalization has no meaning. Thus, maxims must have some generality to be properly tested.

Now suppose I test the following maxim. “We cannot lie except to achieve our ends.” This maxim is sufficiently general to be universalized, but not sufficiently specific to rule out immoral actions. And the problem is not ameliorated by turning to the second formulation of the imperative. Does respect for persons tell us anything about whether we should universalize general or specific maxims? Should I always respect persons or always respect them except in certain situations? It appears that universalization is not as simple as it initially appeared.

10. General Difficulties

Kant claimed that duties are absolute. If duties are absolute, then what about conflicts between duties? Kant states that perfect duties supersede imperfect ones, and thus the duty not to lie precedes the duty to help others. If this is so, it follows that we must tell the truth to inquiring murderers. But this presented great difficulties for Kant. Surely duties have exceptions and perfect duties are not sacrosanct. Kant might have avoided this difficulty, as we have seen, by advocating that we universalize maxims with exceptions. A maxim like, “never lie except to inquiring murderers,” is not problematic.

Along these lines, the twentieth-century philosopher W.D. Ross argued that no duties were absolute. Ross, who taught at Oxford for nearly fifty years and was one of the world’s great Aristotelian and Kantian scholars, tried to modify Kant’s theory to account for conflict of duty cases. according to Ross, we have prima facie—at first glance—duties, but they are conditional. Our actual duties—at second glance, you might say—depend upon the situation. In conflict of duty cases, we carefully weigh our duties and then proceed to do the best we can. The problem is whether Ross’ conception of duties is too subjective and situational, since individuals decide which duties apply in given situations. The main problem with Ross’ version of deontology is its emphasis on subjects and situations, an emphasis Kant wanted to avoid.

Another problem with Kant’s system is that it is so formal and abstract it hardly motivates us. Even if Kant could prove that ethics were completely rational, wouldn’t this take something away from the importance of moral choice? Isn’t ethics too messy and imprecise for the formality, precision, and logic of Kant’s system? Aristotle said that ethics could never be so precise. Maybe Kant demanded too much precision from his ethics?

Another general difficulty is Kant’s rejection of the importance of consequences. According to Kant, if we do our duty we are absolved of all responsibility for the consequences of our action. He defends this view in part because he believes we can never know the consequences with certainty. This is true to an extent, but this view rests upon very pessimistic assumptions about our knowledge of the consequences of our actions. If for no apparent reason we tell our friend she looks positively awful and disgusting, we can be pretty sure she will feel bad about this. We are hardly absolved by our claim that we were not sure she would feel bad. Sometimes we can be reasonably sure of the consequences, in which case duty may not be important. Much trouble has been caused by people who were simply “doing their duty.”

11. Kant’s Fundamental Idea

Despite the nuances connected with the idea of universalization, there is a core idea at the heart of Kant’s theory which is his lasting legacy. We have all been reprimanded by someone saying “how would you like someone to do that to you?” This is Kant’s fundamental idea. If there is a reason why you don’t want people to do something to you, then that same reason applies to what you want to do to others. It gives you a reason not to treat others in a way that you do not want to be treated. And, if you ignore that reason, you are acting irrationally. This is the kind of rational constraint Kant believed imposed itself upon our conduct. Of course, we have all experienced people who believe that the rules that apply to us do not apply to them, and, if they are bigger or more powerful than we are there is not much we can do. They might say to us, “You help me move on Saturday, but I won’t help you move next week.” We feel that they are doing something unfair and inconsistent, whether or not they recognize it. That is Kant’s fundamental idea. A reason for one is a reason for all.

A purely rational morality is a fascinating idea. We saw in an earlier chapter how moral judgments might be truths of reason. Whether this is true depends upon our understanding of concepts like rationality, interests, and individuality. In the strong conception of rationality, others’ interests give us a reason to act. In the weak conception, others’ interests do not give us a reason. This issue also relates to the earlier discussion of egoism between Kalin and Medlin. If we think other people should respect our interests, so the argument goes, then we should respect theirs. But when we say others should respect our interests does that mean: 1) we want them to respect our interests; or 2) they have a reason to respect our interests. Kant, and his contemporary followers argue for “2,” while other philosophers argue for “1.” Clearly we want others to act in our interest, but it is not clear our interests give others a reason to act.

A conception of individualism is also relevant. If we have a strong conception of individuality—one in which individuals are radically separate—it is hard to see how the other’s desires/interests/wants give us a reason to do anything. On the other hand, if we have a weak conception of individuality —one in which all individuals are intimately connected—it is easy to see how the other’s interests give us reason to act. Maybe the rise of individualism lessens our sense of obligation toward others, or maybe communalism lessens our sense of obligation toward ourselves. Whatever our conclusions, the conceptions of rationality, interests, and individuality play a significant role in determining whether Kant’s primary idea is convincing for us.

Kant’s basic idea is that morality is grounded in reason. Essentially, if there really is a reason why we should not commit immoral acts, then that reason applies to all of us. If there really is a reason to treat people with dignity and respect, or not to lie or cheat them, then this reason applies to all of us whether we want it to or not. To say there are universal moral reasons ultimately confirms our belief in the intelligibility of reality. And, if the moral universe is unintelligible, nothing matters.

12. Conclusion

Despite all the positive contributions of Kant’s moral thought, one final difficulty plagues the theory. Kant argued that the good life is a life of duty and that other lives are not worthwhile. But there have been many decent and happy lives that were not motivated by duty. Consider also persons who live from a sense of duty, but who are miserable and unhappy. They live without love, compassion, pleasure, beauty, or intellectual stimulation. Are such individuals moral exemplars? True, many live decadent lives in exclusive pursuit of pleasure or happiness while dismissing moral virtue. But Kant’s ethics suffer from its emphasis on duty and virtue while neglecting happiness and pleasure. And if a philosophy stresses duty over happiness, then why should we do our duty? Duty may be part of morality, but so is happiness . In a forthcoming post I’ll turn to a moral theory which emphasizes the good over the right, happiness over duty. That theory is utilitarianism

November 3, 2017

What if Mueller proves his case and it doesn’t matter?

Dave Roberts of Vox has just published what I believe is the most important article I’ve read recently about the crisis of American democracy: America is facing an epistemic crisis: What if Mueller proves his case and it doesn’t matter?

The essence of his argument is:

1) Republicans believe fairy tales: Pizzagate, Obama wasn’t born in the USA and wiretapped Trump, Seth Rich was assassinated by Democrats, Trump had millions of votes stolen, uranium deal is a scandal, Clinton emails issue is criminal, etc.

2) There is plenty of evidence that makes it highly probable that there was collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia meant to affect the election.

3) This leads to the following possible scenario: a) Mueller proves his case; b) Trump and right-wing media reject the evidence and invent fairy tales about the issue; and c) the Republican base believe their media.

4) In other words, the right-wing no longer accepts knowledge.

“What if there is no longer any evidentiary standard that could overcome the influence of right-wing media?” Over the last two decades, conservatives have rejected the mainstream institutions which previously arbitrated factual disputes and disseminated knowledge—government, journalism, science, and the academy. Instead the right relies on their own parallel set of institutions, especially their media ecosystem.

But the right’s institutions are not of the same kind as the ones they seek to displace. Mainstream scientists and journalists see themselves as beholden to values and standards that transcend party or faction. They try to separate truth from tribal interests and have developed various guild rules and procedures to help do that. They see themselves as neutral arbiters, even if they do not always uphold that ideal in practice.

But the difference of course is that the right’s institutions don’t care about values or truths that transcend party or faction. They don’t care to be neutral arbiters; they are only concerned with spreading propaganda. Of course the pretense for conservative media was that mainstream institutions were biased.

But the right did not want better neutral arbiters. The institutions it built scarcely made any pretense of transcending faction; they are of and for the right. There is nominal separation of conservative media from conservative politicians, think tanks, and lobbyists, but in practice, they are all part of the conservative movement. They are prosecuting its interests; that is the ur-goal.

Indeed, the far right rejects the very idea of neutral, binding arbiters; there is only Us and Them, only a zero-sum contest for resources. That mindset leads to what I call “tribal epistemology” — the systematic conflation of what is true with what is good for the tribe.

Of course there have always been fringe views on the right, but they were held in check by gatekeepers until “the 1990s and 2000s swept those gatekeepers away, giving the loudest voice, the most exposure, and the most power to the most extreme elements on the right. The right-wing media ecosystem became a bubble from which fewer and fewer inhabitants ever ventured.” And the evidence shows that uber partisanship is primarily on the right. Unfortunately the mainstream media has never learned to deal with this right-wing bubble.

5) Republican politician have no incentive to indict Trump since: a) right-wing media demands fealty to Trump; b) the base believes and leans on their politicians; and c) GOP officials, fearing a challenge from the right, pay obeisance. So they can’t cross a base who is being lied to about the Mueller investigation or anything else.

As long as Republican politicians are frightened by the base, the base is frightened by scary conspiracies in right-wing media, and right-wing media makes more money the more frightened everyone is, Trump appears to be safe. As long as the incentives are aligned in that direction, there will be no substantial movement to censure, restrain, or remove him from office.

6) So what happens if Trump is proven guilty and we can’t do anything about it?

Mainstream scholars may not think that Trump will be able to get away with firing Mueller or pardoning everyone involved. But why not? “What if facts and persuasion just don’t matter anymore?” As Roberts puts it:

As long as conservatives can do something — steal an election, gerrymander crazy districts to maximize GOP advantage, use the filibuster as a routine tool of opposition, launch congressional investigations as political attacks, hold the debt ceiling hostage, repress voting among minorities, withhold a confirmation vote on a Supreme Court nominee, defend a known fraud and sexual predator who has likely colluded with a foreign government to gain the presidency — they will do it, knowing they’ll be backed by a relentlessly on-message media apparatus.

And if that’s true, if the very preconditions of science and journalism as commonly understood have been eroded, then all that’s left is a raw contest of power.

Donald Trump has the power to hold on to the presidency, as long as elected Republicans, cowed by the conservative base, support him. That is true almost regardless of what he’s done or what’s proven by Mueller. As long as he has that power, he will exercise it. That’s what recent history seems to show.

Democrats do not currently have the numbers to stop him. They can’t do it without some help from Republicans. And Republicans seem incapable, not only of acting on what Mueller knows, but of even coming to know it.

Roberts concludes that “we may just have to live with a president indicted for collusion with a foreign power.” But I think that’s not even the worst of it. The worst part is that society can’t survive without the assumption that people tell the truth. That is the reason why truth-telling is a universal moral imperative. Of course the truth will eventually find us. The climate will continue to change, people will increasingly live under a tyrannical government, science education will continue to degrade, immigration will end, H1B visas will be revoked, and we will slowly become a 3rd rate technological power. The Japanese or Chinese or Russians will divide us and then build a robotic army to kill us all.

And all of this for tax cuts, the license to pollute the planet, and to make sure people don’t get health care. What an exceptional nation we are.

Furthermore, once the battle is for power alone, once there is no forum for rational discourse to adjudicate between competing views, then force and fraud will be all that’s left. Some will come to increasingly dominate, others to further submit. We will really live in a Hobbesian state of nature. And, as long as those who have ursurped power can hold onto it, as long as their opponents are not relative power equals, they will have won the battle. But then again, they too live now live in a state of war. They too must continually look over the shoulder for the next coup. I wonder if that’s really in their self-interest.

November 2, 2017

Will Trump Fire Mueller?

A tyrant is an absolute ruler unrestrained by law or person, or one who has usurped legitimate sovereignty.

I’m 62 years old and have lived through Vietnam, Watergate, Iran-Contra, Newt Gingrich, Tom Delay, Dick Cheney, and the American glorification of torture. Yet things keep getting worse. It’s hard to know where to begin, but just this year alone we’ve seen the sabotaging of health care, the firing of the FBI director to obstruct justice, the pardon of Arpaio, withdrawl from the Paris climate agreement, nuclear saber rattling, more voter suppression, the destruction of the EPA , the approval of dangerous chemicals, the silencing of scientists, the undermining of the energy, education, and most of the other governmental departments, and more. And this is all just off the top of my head. Those who are aware and possess a moral compass should either cry or revolt.

And for what? Mostly for a little bit of money. For tax cuts that won’t even make the rich happier. But now I think we are at a crucial moment, and here’s what I think will happen—although I hope that countervailing forces of which I am unaware will prevent this.

As Mueller’s investigation of Trump closes in, I believe Trump will fire Mueller and the Republicans will not object. This depends on how close Mueller gets, but if he uncovers enough of Trump’s crimes then I think the firing is almost inevitable. I hope I’m wrong.

And the Republicans won’t object because their position has been staked out—party over country. We have seen this over and over, most recently with the revelation by PBS Frontline that when the Obama administration and intelligence officials informed Ryan and McConnell in a closed-door meeting that the election was being compromised by Russia, the Republican leaders said they would not join a statement informing the American public of this fact. Here’s one reporter’s commentary on that meeting:

“It’s a moment when politics and partisan positioning appears to take precedence over national security,” Greg Miller of The Washington Post tells FRONTLINE. “In other words, they are so worried about each other, the Democrats and Republicans as adversaries, that they can’t get around the idea that there is a bigger adversary.”

So if Trump fires Mueller and the Republicans don’t object, then the thin reed upon which an already fragile rule of law rests will collapse. If there is no accountability of the executive branch, then nothing prevents it from shutting down opposition media, jailing political opponents, completely looting the treasury, and all the rest.

And McConnell and Ryan aren’t protected from the onslaught either. Like other conservative Republicans—Cantor, Boehner, Flake, Corker, McCain—they too won’t seem sufficiently loyal to Trump, Bannon, the Mercers, the Koch brothers, and all the rest of the suit wearing gangsters. In the end no one is safe from arbitrary power, even the mafia godfather Trump himself must look over his shoulder. Perhaps they will prefer Pence. But even the oligarchs themselves aren’t secure. By unraveling the social stability upon which their fortunes rest, they too become susceptible to the chaos. It is hard to see how undermining the stability of the country is in their long-term interest.

Aristotle said long ago that when human passion rather than reason provides the basis for law, we are all at the mercy of the changing, irrational passions of men. Aristotle was right.

What all this implies is that white Americans might actually experience what African and Native Americans have experienced for centuries—law based on power alone, with considerations of justice being irrelevant. At that point we live under tyranny, as most people have in human history. Perhaps it is our turn?

October 31, 2017

What is Social Cooling?

“Like oil leads to global warming …

Data leads to social cooling”

Social cooling refers to the idea that if “you feel you are being watched, you change your behavior.” And the massive amounts of data being collected, especially online, is exxagerating this effect. This may limit our desire to speak or think freely thus bring about “chilling effects” on society—or social colling.

Here’s a summary of how this works:1. Your data is collected and scored. Then databrokers use algorithms to reveal thousands of private details about you—friends and acquintances, religious and political beliefs, educational background, sexual orientation, reading habits, personality traits and flaws, economic stability, etc. This derived data is protected as corporate free speech.

2. Your digital reputation may affect your opportunities. Facebook posts may affect job chances of getting or losing a job, bad friends may affect the rate of your loan, etc. These effects are independent of whether the data is good or bad.

3. People start changing their behavior to get better scores which has disparate outcomes. Social Cooling describes the negative side effects of trying to be reputable online. Some of the negative effects are:

a) Conformity – you may hesitate to click on a link because you fear being tracked. This is self-censoring, which has a chilling effect. You fear choosing freely.

b) Risk-aversion – When physicians are scored, those who try to help sicker patients have lower scores that those who avoid such patients, because sicker patients have higher mortality rates.

c) Social rigidity – Our digital reputations limit our will to protest. For instance Chinese citizens have begun to get “social credit scores,” which score how well-behaved they are. Such social pressure is a powerful form of control.

4) As your weaknesses are mapped, you become increasingly transparent. This leads to self-censorship, conformity, risk-aversion, and social rigidity becoming normal. No longer is data a matter of simple credit scores.

All of this leads to questions like: When we become more well behaved, do we also become less human? What does freedom mean in a world where surveillance is the dominant business model? Are we undermining our creative economy because people fear non-conformity? Can minority views still inform us?

5) The solution? Pollution of our social environment is invisible to most people, just like air pollution and climate change once were. So we begin by increasing awareness. But we should act quickly, as data mining and the secrets it reveals is increasing exponentially.