Jake Jackson's Blog, page 19

September 23, 2015

Every ancient culture made accurate measurements of celes...

Every ancient culture made accurate measurements of celestial motion, but they had a range of different solutions to the conflict between the lunar and solar year.

Lunar Calendars

Twenty thousand years ago, Ice Age hunters scratched lines and holes in bones to show the days before the next new moon. The discovery of an eagle bone at le Placard, dated to 13,000 BC, is one of the earliest examples of humankind recording itself against natural phenomenon. Similar observations were made by ancestors of each of the ancient civilisations, but as they approached 5000 BC, their understanding of astronomy led them all to note the differences between lunar and solar time, and to find ways of catching up periodically.

Cultures of the Tigris and Euphrates

Some written records exist from these ancient cultures, although much has been lost, particularly from the Babylonians (whose methods and mythology prefigured much in the Christian Bible), due to great fires at the libraries of Alexandria in 97 BC and AD 696. We do know, at least, that their lunar year, before 2000 BC, consisted of 12 months of alternating 29 and 30 days. The Sumerians, their predecessors, rounded the lunar month up to 30 days, giving them 360 days every year, which neatly dovetailed with their base 60 numbering system, (which formed the basis of the imperial system of 12 inches in a foot and 24 hours in a day).

Some written records exist from these ancient cultures, although much has been lost, particularly from the Babylonians (whose methods and mythology prefigured much in the Christian Bible), due to great fires at the libraries of Alexandria in 97 BC and AD 696. We do know, at least, that their lunar year, before 2000 BC, consisted of 12 months of alternating 29 and 30 days. The Sumerians, their predecessors, rounded the lunar month up to 30 days, giving them 360 days every year, which neatly dovetailed with their base 60 numbering system, (which formed the basis of the imperial system of 12 inches in a foot and 24 hours in a day).

Solar Years

Some evidence of time notation remains in the form of artifacts. Stonehenge, for instance, is an incredible formation of standing stones which, whatever its other purposes, perfectly records the summer solstice, designed so the sun shines down the central avenue, illuminating the centre stone.

Archeological finds and early documents have revealed that the ancient Greeks added 90 days every eight years to make up the difference between the lunar and solar years. The Chinese, by c. 2350 BC, had added seven months every 19 years. Jewish astronomers added one month every three years with a further month added by decree when necessary.

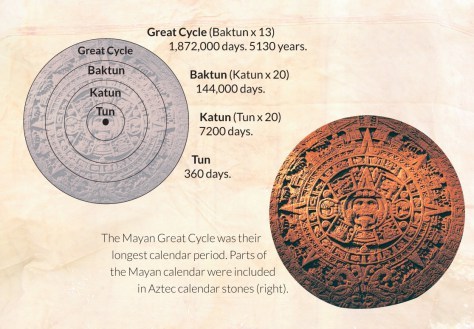

Unusually, the Mayans of Central America used a solar year of 365 days, with 18 months of 20 days each and a further five special days. In fact, they also had another calendar of 260 days, a cycle reserved for days of worship. Using this – combined with the 365-day calendar – they calculated what they termed Calendar Rounds. Separately they measured Long Cycles of 360-day units called tuns, which they multiplied by 400 then 13 to create their Great Cycles of 5130 years which marked the end of one life and the start of another. The end of the current cycle, the end of the world according to Mayan predictions, was AD 2012.

The Ancient Egyptians

The ancient Egyptians are especially important to our concept of time because their intellectual and cultural influence had a major impact on the development of the Julian calendar, leading to the Gregorian form we use today.

The Nile, as the source of life, was also the key to the Egyptian understanding of time. Using a nileometer, possibly as early as 5000 BC, they determined that the year was 365 days long. The nileometer had notches or steps in the banks of the Nile marking the different levels of water height from the low point in May to its highest in September, so they could plan for the floods between June and October, the planting and growth of crops from October to February and the harvest from February to June. The shadows cast by the pyramids were also used to measure equinoxes, in a similar way to the menhirs of Stonehenge.

The ancient Egyptians’ advanced pursuit of knowledge led them to observe that the star we know as Sirius rose in line with the sun at the point every year when the annual inundation of the Nile occurred. This enabled them to conclude that the year was in fact 365 1⁄4 days long.

In a move which has echoes throughout the history of time, however, local priests resisted this slight change, having adopted the 365-day year as sacred, even though scientific observation proved them to be incorrect. The priests saw science as undermining their authority, a theme we’ll encounter again in Europe’s Dark and Middle Ages.

Alexandria

By 334 BC, Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) had conquered Greece, Egypt and Persia – three of the most literate, philosophically and scientifically inclined nations in the world. The knowledge from these three cultures was brought together in the cosmopolitan Egyptian city of Alexandria, built by Alexander in 332 BC. This metropolis, with its population of 300,000 (not counting slaves) by the first century AD, also housed the most extensive library of the world’s great literature, including Aristotle’s works. Waterclocks were created here, an encyclopedia of astronomy was drawn up, mathematical treatises and musings on the nature of time and man were distributed.

By 334 BC, Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) had conquered Greece, Egypt and Persia – three of the most literate, philosophically and scientifically inclined nations in the world. The knowledge from these three cultures was brought together in the cosmopolitan Egyptian city of Alexandria, built by Alexander in 332 BC. This metropolis, with its population of 300,000 (not counting slaves) by the first century AD, also housed the most extensive library of the world’s great literature, including Aristotle’s works. Waterclocks were created here, an encyclopedia of astronomy was drawn up, mathematical treatises and musings on the nature of time and man were distributed.

It is possible to trace the origins of all core principles behind the measurement of time (and the calendar) to the astronomical and mathematical scholarship of Alexandria in the two centuries before the birth of Christ and beyond.

Caesar and Cleopatra

Shakespeare’s dramatic Cleopatra (69–30 BC)seems to have been an accurate portrayal of the intelligent, passionate, politically sagacious historic figure who seduced Julius Caesar (100–44 BC) in order to remove her brother Ptolemy from the stewardship of an Egypt which had by been conquered by the Roman Empire.

Caesar was a powerful military and political leader, whose success had given him power over the whole of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East: more than half the known world of the time. The chaos and dispute of dates throughout the vast Empire made Caesar determined to bring the calendar under his authority: it is said that in 47 BC, at a feast arranged by Cleopatra to honour Caesar, he discussed the Egyptian method of measuring the year with the celebrated astronomer Sosigenes and decided how to effect a far-reaching reform of time.

The next Time post looks at the Julian Calendar which was used in the West until 1582, by which time 13 days had been lost! So Christmas, Easter, the Summer Solstice and more were celebrated at the wrong time…

Some other posts of interest.

The first post in the What is Time? sequence

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

What is Time? Time and the Calendar

What is Time? Lunar vs Solar Calendar

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Only Connect, the Creative Melting pot of 1910 and Modernism

Fibonacci 0

Micro-fiction podcast: Time Thief

The image in the head of this post is the Aztec calendar stone, from 15th Century, now housed at the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City (see here for a good article)

The post What is Time? Ancient Calendars appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

What is Time? Ancient Calendars

Every ancient culture made accurate measurements of celestial motion, but they had a range of different solutions to the conflict between the lunar and solar year.

Lunar Calendars

Twenty thousand years ago, Ice Age hunters scratched lines and holes in bones to show the days before the next new moon. The discovery of an eagle bone at le Placard, dated to 13,000 BC, is one of the earliest examples of humankind recording itself against natural phenomenon. Similar observations were made by ancestors of each of the ancient civilisations, but as they approached 5000 BC, their understanding of astronomy led them all to note the differences between lunar and solar time, and to find ways of catching up periodically.

Cultures of the Tigris and Euphrates

Some written records exist from these ancient cultures, although much has been lost, particularly from the Babylonians (whose methods and mythology prefigured much in the Christian Bible), due to great fires at the libraries of Alexandria in 97 BC and AD 696. We do know, at least, that their lunar year, before 2000 BC, consisted of 12 months of alternating 29 and 30 days. The Sumerians, their predecessors, rounded the lunar month up to 30 days, giving them 360 days every year, which neatly dovetailed with their base 60 numbering system, (which formed the basis of the imperial system of 12 inches in a foot and 24 hours in a day).

Some written records exist from these ancient cultures, although much has been lost, particularly from the Babylonians (whose methods and mythology prefigured much in the Christian Bible), due to great fires at the libraries of Alexandria in 97 BC and AD 696. We do know, at least, that their lunar year, before 2000 BC, consisted of 12 months of alternating 29 and 30 days. The Sumerians, their predecessors, rounded the lunar month up to 30 days, giving them 360 days every year, which neatly dovetailed with their base 60 numbering system, (which formed the basis of the imperial system of 12 inches in a foot and 24 hours in a day).

Solar Years

Some evidence of time notation remains in the form of artifacts. Stonehenge, for instance, is an incredible formation of standing stones which, whatever its other purposes, perfectly records the summer solstice, designed so the sun shines down the central avenue, illuminating the centre stone.

Archeological finds and early documents have revealed that the ancient Greeks added 90 days every eight years to make up the difference between the lunar and solar years. The Chinese, by c. 2350 BC, had added seven months every 19 years. Jewish astronomers added one month every three years with a further month added by decree when necessary.

Unusually, the Mayans of Central America used a solar year of 365 days, with 18 months of 20 days each and a further five special days. In fact, they also had another calendar of 260 days, a cycle reserved for days of worship. Using this – combined with the 365-day calendar – they calculated what they termed Calendar Rounds. Separately they measured Long Cycles of 360-day units called tuns, which they multiplied by 400 then 13 to create their Great Cycles of 5130 years which marked the end of one life and the start of another. The end of the current cycle, the end of the world according to Mayan predictions, was AD 2012.

The Ancient Egyptians

The ancient Egyptians are especially important to our concept of time because their intellectual and cultural influence had a major impact on the development of the Julian calendar, leading to the Gregorian form we use today.

The Nile, as the source of life, was also the key to the Egyptian understanding of time. Using a nileometer, possibly as early as 5000 BC, they determined that the year was 365 days long. The nileometer had notches or steps in the banks of the Nile marking the different levels of water height from the low point in May to its highest in September, so they could plan for the floods between June and October, the planting and growth of crops from October to February and the harvest from February to June. The shadows cast by the pyramids were also used to measure equinoxes, in a similar way to the menhirs of Stonehenge.

The ancient Egyptians’ advanced pursuit of knowledge led them to observe that the star we know as Sirius rose in line with the sun at the point every year when the annual inundation of the Nile occurred. This enabled them to conclude that the year was in fact 365 1⁄4 days long.

In a move which has echoes throughout the history of time, however, local priests resisted this slight change, having adopted the 365-day year as sacred, even though scientific observation proved them to be incorrect. The priests saw science as undermining their authority, a theme we’ll encounter again in Europe’s Dark and Middle Ages.

Alexandria

By 334 BC, Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) had conquered Greece, Egypt and Persia – three of the most literate, philosophically and scientifically inclined nations in the world. The knowledge from these three cultures was brought together in the cosmopolitan Egyptian city of Alexandria, built by Alexander in 332 BC. This metropolis, with its population of 300,000 (not counting slaves) by the first century AD, also housed the most extensive library of the world’s great literature, including Aristotle’s works. Waterclocks were created here, an encyclopedia of astronomy was drawn up, mathematical treatises and musings on the nature of time and man were distributed.

By 334 BC, Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) had conquered Greece, Egypt and Persia – three of the most literate, philosophically and scientifically inclined nations in the world. The knowledge from these three cultures was brought together in the cosmopolitan Egyptian city of Alexandria, built by Alexander in 332 BC. This metropolis, with its population of 300,000 (not counting slaves) by the first century AD, also housed the most extensive library of the world’s great literature, including Aristotle’s works. Waterclocks were created here, an encyclopedia of astronomy was drawn up, mathematical treatises and musings on the nature of time and man were distributed.

It is possible to trace the origins of all core principles behind the measurement of time (and the calendar) to the astronomical and mathematical scholarship of Alexandria in the two centuries before the birth of Christ and beyond.

Caesar and Cleopatra

Shakespeare’s dramatic Cleopatra (69–30 BC)seems to have been an accurate portrayal of the intelligent, passionate, politically sagacious historic figure who seduced Julius Caesar (100–44 BC) in order to remove her brother Ptolemy from the stewardship of an Egypt which had by been conquered by the Roman Empire.

Caesar was a powerful military and political leader, whose success had given him power over the whole of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East: more than half the known world of the time. The chaos and dispute of dates throughout the vast Empire made Caesar determined to bring the calendar under his authority: it is said that in 47 BC, at a feast arranged by Cleopatra to honour Caesar, he discussed the Egyptian method of measuring the year with the celebrated astronomer Sosigenes and decided how to effect a far-reaching reform of time.

The next Time post looks at the Julian Calendar which was used in the West until 1582, by which time 13 days had been lost! So Christmas, Easter, the Summer Solstice and more were celebrated at the wrong time…

Some other posts of interest.

The first post in the What is Time? sequence

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

What is Time? Time and the Calendar

What is Time? Lunar vs Solar Calendar

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Only Connect, the Creative Melting pot of 1910 and Modernism

Fibonacci 0

Micro-fiction podcast: Time Thief

The image in the head of this post is the Aztec calendar stone, from 15th Century, now housed at the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City (see here for a good article)

Filed under: Science, Time Tagged: Anthony and Cleopatra, Babel, Babylon, calendar, days of the week, medieval, millennium, religion, science fiction, space-time, Sumeria, Time, Time and the Calendar

September 16, 2015

The dark waters of the storm-racked lake toss the small c...

The dark waters of the storm-racked lake toss the small craft and its terrified occupants. So much for a weekend break!

Echoes | Undertow

The thunder overhead had raged around them as they drifted helplessly across the dark lake. If they had sailed closer to the banks, they would have stopped, secured everything, and sat out the storm. But they were too far away, and the grinding and the bumping under the boat had begun to scare the skipper and his mate .

It had started as a fine day across the lakes, with the surrounding mountains topped by reflections from the blameless skies. It was late in the season so not so many boats had taken to the waters, but Eowen and his childhood friend Gordon, had chanced upon an advert in a local newspaper which offered a weekend away, on a old boat, with food and beer, for less than half the price. Neither of them had planned for a holiday this year, their money was fully committed, they worked every hour they could in the streets, running from one trade to another. They were exhausted, their young lives withering away in the rout of everyday life.

So the boat had been a gift from Heaven. Both managed to organise the weekend off, faking illness or, family disaster, and so would rendezvous at the wharf.

Eowen arrived first, battling down the twisted lane, ducking the brambles and low, groaning branches, of the ever-reducing path until he faced a broken gate. A number was painted roughly across the wiry frame, with other decorations that had flaked long beyond recognition.

“Hey! You made it!” Eowen turned to greet his friend who had also just emerged from the entrails of distressed, ancient trees.

“Yeah, just about.” Gordon wrestled with a grin. “Difficult to find.”

“Me too, been past the top of this lane so many times before, ” he shrugged, “never noticed it. So, this is number 6?” Eowen looked up at the fractured frame. “What happened to 1 through 5?”

“Well, if they’re here, they don’t want to be found,” a slight sneer played across Gordon’s thick lips. He was hot, sweat making islands in his shirt. His eyes flickered between his friend and the decrepit portal.

The gate screeched open abruptly, and sent them backwards by a short step.

“So, you made it.” An improbably old man, his head bent low, eyes peering up at the visitors, fixed them with a stare that rattled down their backs.

“Oh, yes, it took a while to get here!” Eowen attempted to make polite conversation but it fell into the dusty cracks of the path.

“Indeed.” The old man gave a short nod to Gordon, then raised a ragged eyebrow at Eowen. “Follow me.”

The next hour was filled with preparations. The boat lay still in a small, covered bay, rocking slightly in repressed waters. The long shed within which it was housed, was almost completely dark, with only the light of the door to confirm its existence. The old man had taken the cash from the boys, and looked at them, almost ruefully. He took them onto the boat, gave them the instructions, the beers, and a simple map.

“So, you enjoy your time on my pride and joy here.” The old man placed a gentle hand on its bow, patting it, before performing an odd gesture with his right hand and alighting.

“Gordon?” Eowen called out to his friend who sat at the back of the boat, with the tiller and the engine key. “Hey, you ok? Seem awful quiet?”

“Sure, just tired, good to get away.” Gordon shrugged.

“Yeah, me too, let’s go.” Eowen felt the boat surge beneath him, and the doors to the shed shuddered apart, swilling quietly to the side, and Gordon navigated out to the huge lake.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

“Wooh!” Eowen felt his way to the back of the boat, “Did you feel that?”

“Probably just some silt. We’ll be free of it in a minute.” Gordon grimaced, annoyed.

“That was one weird guy back there.” Eowen turned his head to the shore and tried to pick out the shed. Already, it had disappeared into the gloom of the surrounding trees.

“Yeah, now we know why it was so cheap, not exactly throbbing with trade!”

“No.” Eowen paused. “I said I’d text my sister to tell her––” He sighed. “Damn! No signal!”

“Well that’s a surprise!” Gordon half-laughed. “Didn’t expect anything else, did you?”

“‘Suppose not.” Eowen slumped his shoulders. “I should have texted earlier. She’s looking after our mother, seemed fed up.”

“You’ll be back soon enough, I guess.” Gordon smiled.

Eowen looked out at the wide stretch of water. The two males were typically taciturn. Minutes drifted by with just the sound of the engine chugging beneath them, and the gentle lapping of the water all around. The occasional bubble from below heralded the presence of other creatures.

“FIsh?” Gordon queried, wondering at the absence of birds. He noticed the gathering clouds from the South, scudding in towards the dark lake.

“That’s quick.” He pointed.

“Yeah, weather changes so fast round here. It’ll come and go”

“Ok,” Eowen looked up at his friend, “you’ve done this before.”

“Yep.” Gordon seemed to swallow a shadow, and gulped. The clouds had arrived above the lake, their bold, burgeoning curves reflected deep onto the surface of the Lake.

And then the storm broke.

The little boat was flicked across the water, almost turning over.

“What they Hell!” Eowen shouted, gripping the side of the boat, water lashing into his eyes, his stomach lurching.

“It’ll be over soon.” Gordon remained steadfast at the tiller, feet apart, his face was turned into the storm, his hand on the engine throttle, chasing it hard.

The rain burst across them, a wave smashed into the bow of the little boat, and the sound of a heavy wrench cranked hard. The engine stopped.

“Damn.” Eowen muttered, his face white.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

“Gordon? What is that?” He knock his head against the side.

“Not sure.” Gordon looked back at his friend, his eyes narrow and fringed with great drops of water.

The thunder overhead continued to rage around them as now they drifted helplessly across the dark lake. If they had been closer to the banks, they’d have stopped, secured everything, and sat out the storm. But they were too away, and the grinding under the boat had begun to worry the skipper and his mate.

The storm abated. Eowen had scrunched his eyes and prayed to the God he’d ignored for the last decade of his life. Gordon shook his friend. “Hey, it’s ok now.”

Eowen could feel the craft was no longer rocking, so he opened a single eye. “But it’s so dark. Is the engine ok?” He could smell the mist on the water. Perhaps it was smoke.

Gordon tried to start the engine. “Nope. Too waterlogged. Battery’s gone too.”

“Oh great.” Eown struggled up, still holding the side of the boat. “Oh!” Another jolt from below, and more grinding. “Where are we then? Look!” He pointed at the shore, which was crowded with trees, but its banks were stripped of vegetation, fallen trunks strewn like discarded bodies. Long shadows stretched across the water as the boat drifted on.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

“I thought we were on the lake?” Moist leaves slipped across the Eowen’s cheek. He jumped back, and winded himself against the edge of the boat. A faint mist seemed to linger across the water, burning at its touch.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

Time passed. Night passed.

“Gordon?” He could just see his friend, still at the tiller, his legs firm. Eowen struggled for breath, and looked around drowsily, wondering why it was still dark. All around was silent except for the rutting noises below, as the prop shaft seemed to grind against rocks and silt underwater.

Eowen found his eyelids dragging down, as though drowning him in the agony of sleep. As the darkness descended he surrendered to its charms.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

A warmth swam a cross his face, and woke him. In a half-lucid state, his back aching, and left leg numb from its awkward position he looked up at Gordon still at the tiller, then shook his head and allowed it to loll in the direction of the water.

Bump. Bump. Grind

He thought he saw a reflection, just below the surface. He blinked. He realized it was a face, eyes closed, grey, mouth drawn down, and following the path of the boat, alongside, was a head, and another, and another. Eowen looked across and saw that everywhere was crowded with bodies.

“Gordon, have you seen––?”

“Yep.” The response was distant.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

A skull now emerged, bobbling alongside the boat, and banging sickeningly. Then a broken ribcage materialized.

“Oh my God.” Eowen looked down again, beside the boat, the face he stared at, opened its eyes.

For a long moment Eowen and the face gazed at each other, separated only by the swilling surface of the dark waters.

And he realised he looking at his own face. But it was not a reflection.

Eowen yelped as hands reached up and hauled him overboard, splashing black water high into the air, until he disappeared below, scrambling, screaming until, bubbles skittered up and across the surface, and the sounds of choking subsided

* * *

Later, as the morning cleared the remnants of the night Gordon navigated slowly back to the boat shed, and waved at the shore. The little old man emerged from the bushes, and responded in his own desultory way.

“Is it done?” The old man cried out, his voice carried echoes of the heads still bobbing on the other side of the lake.

“Aye.” Gordon passed the mooring rope across, mumbled his last words, and shimmered back into the lake.

“One day, we shall all rise my friend.”

[ends]

More in two weeks, (more from What is Time? next week)

There are many other stories in this series, including:

Time Thief

Water Grave

Ophelia A.I.

Helm

Deadly Survey

Masks

Henge

Here’s a related post, 5 Steps to the SF and Fantasy Podcasts

And a post on the life, work of Robert Bloch.

The post Micro-fiction 027 – Undertow appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Micro-fiction 027 – Undertow

The dark waters of the storm-racked lake toss the small craft and its terrified occupants. So much for a weekend break!

Echoes | Undertow

The thunder overhead had raged around them as they drifted helplessly across the dark lake. If they had sailed closer to the banks, they would have stopped, secured everything, and sat out the storm. But they were too far away, and the grinding and the bumping under the boat had begun to scare the skipper and his mate .

It had started as a fine day across the lakes, with the surrounding mountains topped by reflections from the blameless skies. It was late in the season so not so many boats had taken to the waters, but Eowen and his childhood friend Gordon, had chanced upon an advert in a local newspaper which offered a weekend away, on a old boat, with food and beer, for less than half the price. Neither of them had planned for a holiday this year, their money was fully committed, they worked every hour they could in the streets, running from one trade to another. They were exhausted, their young lives withering away in the rout of everyday life.

So the boat had been a gift from Heaven. Both managed to organise the weekend off, faking illness or, family disaster, and so would rendezvous at the wharf.

Eowen arrived first, battling down the twisted lane, ducking the brambles and low, groaning branches, of the ever-reducing path until he faced a broken gate. A number was painted roughly across the wiry frame, with other decorations that had flaked long beyond recognition.

“Hey! You made it!” Eowen turned to greet his friend who had also just emerged from the entrails of distressed, ancient trees.

“Yeah, just about.” Gordon wrestled with a grin. “Difficult to find.”

“Me too, been past the top of this lane so many times before, ” he shrugged, “never noticed it. So, this is number 6?” Eowen looked up at the fractured frame. “What happened to 1 through 5?”

“Well, if they’re here, they don’t want to be found,” a slight sneer played across Gordon’s thick lips. He was hot, sweat making islands in his shirt. His eyes flickered between his friend and the decrepit portal.

The gate screeched open abruptly, and sent them backwards by a short step.

“So, you made it.” An improbably old man, his head bent low, eyes peering up at the visitors, fixed them with a stare that rattled down their backs.

“Oh, yes, it took a while to get here!” Eowen attempted to make polite conversation but it fell into the dusty cracks of the path.

“Indeed.” The old man gave a short nod to Gordon, then raised a ragged eyebrow at Eowen. “Follow me.”

The next hour was filled with preparations. The boat lay still in a small, covered bay, rocking slightly in repressed waters. The long shed within which it was housed, was almost completely dark, with only the light of the door to confirm its existence. The old man had taken the cash from the boys, and looked at them, almost ruefully. He took them onto the boat, gave them the instructions, the beers, and a simple map.

“So, you enjoy your time on my pride and joy here.” The old man placed a gentle hand on its bow, patting it, before performing an odd gesture with his right hand and alighting.

“Gordon?” Eowen called out to his friend who sat at the back of the boat, with the tiller and the engine key. “Hey, you ok? Seem awful quiet?”

“Sure, just tired, good to get away.” Gordon shrugged.

“Yeah, me too, let’s go.” Eowen felt the boat surge beneath him, and the doors to the shed shuddered apart, swilling quietly to the side, and Gordon navigated out to the huge lake.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

“Wooh!” Eowen felt his way to the back of the boat, “Did you feel that?”

“Probably just some silt. We’ll be free of it in a minute.” Gordon grimaced, annoyed.

“That was one weird guy back there.” Eowen turned his head to the shore and tried to pick out the shed. Already, it had disappeared into the gloom of the surrounding trees.

“Yeah, now we know why it was so cheap, not exactly throbbing with trade!”

“No.” Eowen paused. “I said I’d text my sister to tell her––” He sighed. “Damn! No signal!”

“Well that’s a surprise!” Gordon half-laughed. “Didn’t expect anything else, did you?”

“‘Suppose not.” Eowen slumped his shoulders. “I should have texted earlier. She’s looking after our mother, seemed fed up.”

“You’ll be back soon enough, I guess.” Gordon smiled.

Eowen looked out at the wide stretch of water. The two males were typically taciturn. Minutes drifted by with just the sound of the engine chugging beneath them, and the gentle lapping of the water all around. The occasional bubble from below heralded the presence of other creatures.

“FIsh?” Gordon queried, wondering at the absence of birds. He noticed the gathering clouds from the South, scudding in towards the dark lake.

“That’s quick.” He pointed.

“Yeah, weather changes so fast round here. It’ll come and go”

“Ok,” Eowen looked up at his friend, “you’ve done this before.”

“Yep.” Gordon seemed to swallow a shadow, and gulped. The clouds had arrived above the lake, their bold, burgeoning curves reflected deep onto the surface of the Lake.

And then the storm broke.

The little boat was flicked across the water, almost turning over.

“What they Hell!” Eowen shouted, gripping the side of the boat, water lashing into his eyes, his stomach lurching.

“It’ll be over soon.” Gordon remained steadfast at the tiller, feet apart, his face was turned into the storm, his hand on the engine throttle, chasing it hard.

The rain burst across them, a wave smashed into the bow of the little boat, and the sound of a heavy wrench cranked hard. The engine stopped.

“Damn.” Eowen muttered, his face white.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

“Gordon? What is that?” He knock his head against the side.

“Not sure.” Gordon looked back at his friend, his eyes narrow and fringed with great drops of water.

The thunder overhead continued to rage around them as now they drifted helplessly across the dark lake. If they had been closer to the banks, they’d have stopped, secured everything, and sat out the storm. But they were too away, and the grinding under the boat had begun to worry the skipper and his mate.

The storm abated. Eowen had scrunched his eyes and prayed to the God he’d ignored for the last decade of his life. Gordon shook his friend. “Hey, it’s ok now.”

Eowen could feel the craft was no longer rocking, so he opened a single eye. “But it’s so dark. Is the engine ok?” He could smell the mist on the water. Perhaps it was smoke.

Gordon tried to start the engine. “Nope. Too waterlogged. Battery’s gone too.”

“Oh great.” Eown struggled up, still holding the side of the boat. “Oh!” Another jolt from below, and more grinding. “Where are we then? Look!” He pointed at the shore, which was crowded with trees, but its banks were stripped of vegetation, fallen trunks strewn like discarded bodies. Long shadows stretched across the water as the boat drifted on.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

“I thought we were on the lake?” Moist leaves slipped across the Eowen’s cheek. He jumped back, and winded himself against the edge of the boat. A faint mist seemed to linger across the water, burning at its touch.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

Time passed. Night passed.

“Gordon?” He could just see his friend, still at the tiller, his legs firm. Eowen struggled for breath, and looked around drowsily, wondering why it was still dark. All around was silent except for the rutting noises below, as the prop shaft seemed to grind against rocks and silt underwater.

Eowen found his eyelids dragging down, as though drowning him in the agony of sleep. As the darkness descended he surrendered to its charms.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

A warmth swam a cross his face, and woke him. In a half-lucid state, his back aching, and left leg numb from its awkward position he looked up at Gordon still at the tiller, then shook his head and allowed it to loll in the direction of the water.

Bump. Bump. Grind

He thought he saw a reflection, just below the surface. He blinked. He realized it was a face, eyes closed, grey, mouth drawn down, and following the path of the boat, alongside, was a head, and another, and another. Eowen looked across and saw that everywhere was crowded with bodies.

“Gordon, have you seen––?”

“Yep.” The response was distant.

Bump. Bump. Grind.

A skull now emerged, bobbling alongside the boat, and banging sickeningly. Then a broken ribcage materialized.

“Oh my God.” Eowen looked down again, beside the boat, the face he stared at, opened its eyes.

For a long moment Eowen and the face gazed at each other, separated only by the swilling surface of the dark waters.

And he realised he looking at his own face. But it was not a reflection.

Eowen yelped as hands reached up and hauled him overboard, splashing black water high into the air, until he disappeared below, scrambling, screaming until, bubbles skittered up and across the surface, and the sounds of choking subsided

* * *

Later, as the morning cleared the remnants of the night Gordon navigated slowly back to the boat shed, and waved at the shore. The little old man emerged from the bushes, and responded in his own desultory way.

“Is it done?” The old man cried out, his voice carried echoes of the heads still bobbing on the other side of the lake.

“Aye.” Gordon passed the mooring rope across, mumbled his last words, and shimmered back into the lake.

“One day, we shall all rise my friend.”

[ends]

More in two weeks, (more from What is Time? next week)

There are many other stories in this series, including:

Time Thief

Water Grave

Ophelia A.I.

Helm

Deadly Survey

Masks

Henge

Here’s a related post, 5 Steps to the SF and Fantasy Podcasts

And a post on the life, work of Robert Bloch.

Filed under: Microfiction, Podcasts Tagged: creepy stories, Dark fantasy, gothic, Horror, podcast, Robert Bloch, sf fiction, Supernatural

September 3, 2015

The significant differences in the length of the solar an...

The significant differences in the length of the solar and lunar years, and the reliance on both the sun and the moon to determine the daily routines of our lives highlights basic paradoxes that have to be controlled by a central calendar-making authority.

The development of our record of everyday time, as expressed through the use of calendars, is a vivid story of tension and conflict: between religious institutions and political authorities, between factions within faiths and, fundamentally, between the different lengths of the solar year and the lunar year.

Western Christian faiths valued the date of Easter above all others. As most cultures were strictly ruled either by or alongside a religious authority, the dates of worship were more than a simple matter of noting time. Like the sculpting of the hidden gargoyles of Canterbury Cathedral (the actual making of which was the act worship), or the rituals of Shabbat to the Jewish religion, certain actions are an article of faith in their own right, whether observed publicly or in private: a fundamental expression of a whole way of life.

The Effect on Daily Life

For most people, up to the end of the Middle Ages, life was lonely, dirty and extremely hard work. The rhythm of the seasons and the ending and arrival of daylight were pillars of their short lives (people lived on average no longer than 35 years).

For most people, up to the end of the Middle Ages, life was lonely, dirty and extremely hard work. The rhythm of the seasons and the ending and arrival of daylight were pillars of their short lives (people lived on average no longer than 35 years).

Unfortunately, these two rhythms – the season and the day – work against each other, because the 12 lunar months of 29 and a half days produce a shorter year than the measurement from one year to the next of the date of the spring and autumn equinoxes (when the sun crosses the equator and day and night are of equal length everywhere on earth, generally around 21 March and 23 September) and the summer and winter solstices (22 June and 22 December). The lunar year, at 354 days, is just over 11 days short of the solar year.

A further complication is that, because the earth does not rotate around the sun in a perfect circle, there is some shifting between one year and the next for these equinoxes and solstices.

Global Considerations

Practical problems only manifest themselves over many years – for example, the Julian calendar became a concern for the Christian faith, which placed high authority on the date of the risen Christ at Easter, only to realise that the date had moved backwards. By the time of the Gregorian calendar reform in the sixteenth century, Easter was 11 days nearer summer, a long way from the spring equinox. In AD 325 the Council of Nicea had agreed that Easter should be on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, making it between 23 March and 25 April. Over the centuries there have been many attempts to fix Easter, like Christmas, to a particular date, one of the most recent of which was a move in 1923 by the then League of Nations. But agreement was never reached.

Practical problems only manifest themselves over many years – for example, the Julian calendar became a concern for the Christian faith, which placed high authority on the date of the risen Christ at Easter, only to realise that the date had moved backwards. By the time of the Gregorian calendar reform in the sixteenth century, Easter was 11 days nearer summer, a long way from the spring equinox. In AD 325 the Council of Nicea had agreed that Easter should be on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, making it between 23 March and 25 April. Over the centuries there have been many attempts to fix Easter, like Christmas, to a particular date, one of the most recent of which was a move in 1923 by the then League of Nations. But agreement was never reached.

A further practical issue is the need to establish a reliable system between cultures which trade or war with each other (both of which have been features of humankind’s relationship with itself over the millennia). The calendar used in Iraqi and Aphganistan is slightly different to the one generally accepted in Europe and the USA, a fact not understood by the military hierarchy, causing terrible human suffering during times of religious observance in the wars of the last decades.

Mean starting date for each Season

A short reminder to finish off:

Vernal Equinox has equal hours, day and night 21 March

Summer Solstice is longest day of the year 22 June

Autumn Equinox has equal hours, day and night 23 September

Winter Solstice is shortest day of the year 22 December

The next What is Time? article will cover ancient calendars, from Egyptian and Mesopotamian to early Roman.

Some other posts of interest.

The first post in the What is Time? sequence

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

What is Time? Time and the Calendar

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Only Connect, the Creative Melting pot of 1910 and Modernism

Fibonacci 0

Micro-fiction podcast: Time Thief

The image in the head of this post is an illustration of the Copernican system of the universe, from The Harmonia Macrocosmica of Andreas Cellarius (published in 1660)

The post What is Time? Lunar vs Solar Calendar appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

What is Time? Lunar vs Solar Calendar

The significant differences in the length of the solar and lunar years, and the reliance on both the sun and the moon to determine the daily routines of our lives highlights basic paradoxes that have to be controlled by a central calendar-making authority.

The development of our record of everyday time, as expressed through the use of calendars, is a vivid story of tension and conflict: between religious institutions and political authorities, between factions within faiths and, fundamentally, between the different lengths of the solar year and the lunar year.

Western Christian faiths valued the date of Easter above all others. As most cultures were strictly ruled either by or alongside a religious authority, the dates of worship were more than a simple matter of noting time. Like the sculpting of the hidden gargoyles of Canterbury Cathedral (the actual making of which was the act worship), or the rituals of Shabbat to the Jewish religion, certain actions are an article of faith in their own right, whether observed publicly or in private: a fundamental expression of a whole way of life.

The Effect on Daily Life

For most people, up to the end of the Middle Ages, life was lonely, dirty and extremely hard work. The rhythm of the seasons and the ending and arrival of daylight were pillars of their short lives (people lived on average no longer than 35 years).

For most people, up to the end of the Middle Ages, life was lonely, dirty and extremely hard work. The rhythm of the seasons and the ending and arrival of daylight were pillars of their short lives (people lived on average no longer than 35 years).

Unfortunately, these two rhythms – the season and the day – work against each other, because the 12 lunar months of 29 and a half days produce a shorter year than the measurement from one year to the next of the date of the spring and autumn equinoxes (when the sun crosses the equator and day and night are of equal length everywhere on earth, generally around 21 March and 23 September) and the summer and winter solstices (22 June and 22 December). The lunar year, at 354 days, is just over 11 days short of the solar year.

A further complication is that, because the earth does not rotate around the sun in a perfect circle, there is some shifting between one year and the next for these equinoxes and solstices.

Global Considerations

Practical problems only manifest themselves over many years – for example, the Julian calendar became a concern for the Christian faith, which placed high authority on the date of the risen Christ at Easter, only to realise that the date had moved backwards. By the time of the Gregorian calendar reform in the sixteenth century, Easter was 11 days nearer summer, a long way from the spring equinox. In AD 325 the Council of Nicea had agreed that Easter should be on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, making it between 23 March and 25 April. Over the centuries there have been many attempts to fix Easter, like Christmas, to a particular date, one of the most recent of which was a move in 1923 by the then League of Nations. But agreement was never reached.

Practical problems only manifest themselves over many years – for example, the Julian calendar became a concern for the Christian faith, which placed high authority on the date of the risen Christ at Easter, only to realise that the date had moved backwards. By the time of the Gregorian calendar reform in the sixteenth century, Easter was 11 days nearer summer, a long way from the spring equinox. In AD 325 the Council of Nicea had agreed that Easter should be on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, making it between 23 March and 25 April. Over the centuries there have been many attempts to fix Easter, like Christmas, to a particular date, one of the most recent of which was a move in 1923 by the then League of Nations. But agreement was never reached.

A further practical issue is the need to establish a reliable system between cultures which trade or war with each other (both of which have been features of humankind’s relationship with itself over the millennia). The calendar used in Iraqi and Aphganistan is slightly different to the one generally accepted in Europe and the USA, a fact not understood by the military hierarchy, causing terrible human suffering during times of religious observance in the wars of the last decades.

Mean starting date for each Season

A short reminder to finish off:

Vernal Equinox has equal hours, day and night 21 March

Summer Solstice is longest day of the year 22 June

Autumn Equinox has equal hours, day and night 23 September

Winter Solstice is shortest day of the year 22 December

The next What is Time? article will cover ancient calendars, from Egyptian and Mesopotamian to early Roman.

Some other posts of interest.

The first post in the What is Time? sequence

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

What is Time? Time and the Calendar

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Only Connect, the Creative Melting pot of 1910 and Modernism

Fibonacci 0

Micro-fiction podcast: Time Thief

The image in the head of this post is an illustration of the Copernican system of the universe, from The Harmonia Macrocosmica of Andreas Cellarius (published in 1660)

Filed under: Science, Time Tagged: calendar, days of the week, lunar calendar, medieval, millennium, religion, science fiction, solar calendar, space-time, Time, Time and the Calendar

August 19, 2015

The remnants of an ancient civilization lurk beneath the ...

The remnants of an ancient civilization lurk beneath the waves and draw the diver down into the darkest layers of the sea, where the weird and the timeless collide.

Origins | Watery Grave

She saw it from above the surface of the ocean, a huge carving scored into the base of the sheer cliffs, deep below the ragged edges of the island. She’d heard this entire land mass, now mostly swallowed by the sea, had once been the site of a civilization that stretched across the Mediterranean, folded into the Arab lands, and far into Africa, down to the rift valley. Perhaps the carving was a god, or an emperor at least. She smiled, checked her oxygen, and dived further towards the grim, tentacled form.

She was strong, and young, pricked with invincibility, unencumbered by wisdom and the failures of age. She pulled at the water, seeking ever further down, consciously following the line of sunlight that sliced into the blue waters until they were devoured by a slow churn of darkness in the deepest layers below. She brushed past swarms of silver fish, with gold and blue trails flicking at her, puzzled by her persistence.

Something inside her pressed her on. She was excited. She had heard the stories, of this outcrop of islands, circling the edge of land like a gigantic maw, each jagged isle, a tooth stabbing above the surf, froth clinging to the wreckage of its glorious memories. She remembered the tales of lost cities, washed from the shores of their grandeur by the grim carelessness of a greater power. She’d seen a few murky photos, some fanciful drawings of the hidden treasures below, treasures that once had shone above the surface, as symbols of the great and powerful.

But now, she was within diving distance of her first discovery. She had read everything she could find on the underwater statues that stretched into the deep valleys of the sea floor, disappearing into the cracks and fissures of the tectonic plates that split the underwater worlds from the land above. She had imagined the huge carvings in the cliff dispatching the statues into the core of the earth, the sea and mud swirling at their feet, their pin-hole, stoney eyes facing forward, resolutely.

Again, she checked her oxygen. She would have to turn back soon, so started to glide down less vigorously, slowing her breaths. In the distance still she could see the carving, so similar to the photos, but more livid, chilling, it drew her on, and she began to notice that there were fewer fish, replaced instead by larger creatures, sea turtles, and eels. She drifted down silently, unwilling to disturb the reveries of this ancient place and its strange, foreboding beings.

As she began to feel a little giddy, she looked again towards the carving, and saw it move. No. An octopus perhaps, slithering in front, obscuring her view for a moment. She began to mutter to herself, taken by the mood around her, as the beams of sunlight withered before the darkness below, and she passed through another layer of the sea, to find no creatures around her at all, but deep below, still the carving and what seemed to be tiny pinpricks of light, perhaps the desperate eyes of deep sea fish, locked to the ocean floor, destined to gaze upwards, yearning for the freedom and the light above.

She checked her oxygen for the last time, certain that she must turn, but something else caught her attention. The seaweed shivered in long trails around the carved limbs before her, the carving in the cliff wall was so much larger than she had realized, its massive head several times the size of her whole body.

She muttered, ‘Oh, look at you, my beauty!” And now she glided further, following the line of the cliff, to the gigantic wonder. She was struck by the stillness, and the eerie glow from the thousands of eyes that cast across the edges of the carving. She realized there were other carvings too, most of them smaller than the one she had seen from above the surface, as though she’d been called by this one, amongst the many.

“Chosen?” She dismissed the thought as soon as she had allowed it to escape her mouth. A thrill of bubbles burst from her helmet. She swore, knowing she had wasted precious air by speaking.

She swam around the carving, noting the corral skeletons at its feet. She sighed, and determined to take a final look at the form, she swam closer. Her eyes traced the tentacles, clearly some evocation of an octopus. perhaps the gods had all been modelled on the great sea creatures, perhaps some of the other carvings would be figures based on turles and sea horses. She smiled at the naivety of these ancient peoples, their lack of sophistication, at the mercy of the elements, and, watching the creatures around them who surveyed the ocean roar, and the winds, and the tumid heat, sought to emulate their properties in manifestations of their gods.

Her foot grazed against the side of the carving.

A cascade of air pockets burst around her.

She reared back, as a huge eye opened before her, covering her entire view with its pale, pulsating surface, oozing at the edges, entrails of seaweed flung away by the lifting of the vast eyelids.

“Ah! The creature rose.

“Ah!” The diver swam backwards, struggling with her air, and the churning waters.

“Ah!” Both screamed.

The creature then shifted its bulk and two feet emerged. Its body wrenched from the cliff, and it fixed the swimmer with its eye.

“Ah!” The creature stood, flinging a storm of water backwards, roiling the darkness, sending it spinning upwards to consume the light, and so it scrambled up and ran, its great eye stolen with fear and astonishment.

“Ah, ah!” The creature looked back, and watched its dream creation dissolve: the sea, the swimmer, the storm. Unable to stare into the face of its cosmic fantasies the creature hung its head in frustration at its own timidity. This dream had been good, the aeons of sleep had fashioned so much detail from the dark waters of the universe, and the little swimming creature had been so real. But now it was all gone, and he would have to start again.

[ends]

More in two weeks, (more from What is Time? next week)

There are many other stories in this series, including:

Time Thief

Butterfly

Ophelia A.I.

Helm

Deadly Survey

Masks

Henge

Here’s a related post, 5 Steps to the SF and Fantasy Podcasts

And a post on the life, work and gothic inheritance of H.P. Lovecraft.

The post Micro-fiction 026 – Watery Grave appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Micro-fiction 026 – Watery Grave

The remnants of an ancient civilization lurk beneath the waves and draw the diver down into the darkest layers of the sea, where the weird and the timeless collide.

Origins | Watery Grave

She saw it from above the surface of the ocean, a huge carving scored into the base of the sheer cliffs, deep below the ragged edges of the island. She’d heard this entire land mass, now mostly swallowed by the sea, had once been the site of a civilization that stretched across the Mediterranean, folded into the Arab lands, and far into Africa, down to the rift valley. Perhaps the carving was a god, or an emperor at least. She smiled, checked her oxygen, and dived further towards the grim, tentacled form.

She was strong, and young, pricked with invincibility, unencumbered by wisdom and the failures of age. She pulled at the water, seeking ever further down, consciously following the line of sunlight that sliced into the blue waters until they were devoured by a slow churn of darkness in the deepest layers below. She brushed past swarms of silver fish, with gold and blue trails flicking at her, puzzled by her persistence.

Something inside her pressed her on. She was excited. She had heard the stories, of this outcrop of islands, circling the edge of land like a gigantic maw, each jagged isle, a tooth stabbing above the surf, froth clinging to the wreckage of its glorious memories. She remembered the tales of lost cities, washed from the shores of their grandeur by the grim carelessness of a greater power. She’d seen a few murky photos, some fanciful drawings of the hidden treasures below, treasures that once had shone above the surface, as symbols of the great and powerful.

But now, she was within diving distance of her first discovery. She had read everything she could find on the underwater statues that stretched into the deep valleys of the sea floor, disappearing into the cracks and fissures of the tectonic plates that split the underwater worlds from the land above. She had imagined the huge carvings in the cliff dispatching the statues into the core of the earth, the sea and mud swirling at their feet, their pin-hole, stoney eyes facing forward, resolutely.

Again, she checked her oxygen. She would have to turn back soon, so started to glide down less vigorously, slowing her breaths. In the distance still she could see the carving, so similar to the photos, but more livid, chilling, it drew her on, and she began to notice that there were fewer fish, replaced instead by larger creatures, sea turtles, and eels. She drifted down silently, unwilling to disturb the reveries of this ancient place and its strange, foreboding beings.

As she began to feel a little giddy, she looked again towards the carving, and saw it move. No. An octopus perhaps, slithering in front, obscuring her view for a moment. She began to mutter to herself, taken by the mood around her, as the beams of sunlight withered before the darkness below, and she passed through another layer of the sea, to find no creatures around her at all, but deep below, still the carving and what seemed to be tiny pinpricks of light, perhaps the desperate eyes of deep sea fish, locked to the ocean floor, destined to gaze upwards, yearning for the freedom and the light above.

She checked her oxygen for the last time, certain that she must turn, but something else caught her attention. The seaweed shivered in long trails around the carved limbs before her, the carving in the cliff wall was so much larger than she had realized, its massive head several times the size of her whole body.

She muttered, ‘Oh, look at you, my beauty!” And now she glided further, following the line of the cliff, to the gigantic wonder. She was struck by the stillness, and the eerie glow from the thousands of eyes that cast across the edges of the carving. She realized there were other carvings too, most of them smaller than the one she had seen from above the surface, as though she’d been called by this one, amongst the many.

“Chosen?” She dismissed the thought as soon as she had allowed it to escape her mouth. A thrill of bubbles burst from her helmet. She swore, knowing she had wasted precious air by speaking.

She swam around the carving, noting the corral skeletons at its feet. She sighed, and determined to take a final look at the form, she swam closer. Her eyes traced the tentacles, clearly some evocation of an octopus. perhaps the gods had all been modelled on the great sea creatures, perhaps some of the other carvings would be figures based on turles and sea horses. She smiled at the naivety of these ancient peoples, their lack of sophistication, at the mercy of the elements, and, watching the creatures around them who surveyed the ocean roar, and the winds, and the tumid heat, sought to emulate their properties in manifestations of their gods.

Her foot grazed against the side of the carving.

A cascade of air pockets burst around her.

She reared back, as a huge eye opened before her, covering her entire view with its pale, pulsating surface, oozing at the edges, entrails of seaweed flung away by the lifting of the vast eyelids.

“Ah! The creature rose.

“Ah!” The diver swam backwards, struggling with her air, and the churning waters.

“Ah!” Both screamed.

The creature then shifted its bulk and two feet emerged. Its body wrenched from the cliff, and it fixed the swimmer with its eye.

“Ah!” The creature stood, flinging a storm of water backwards, roiling the darkness, sending it spinning upwards to consume the light, and so it scrambled up and ran, its great eye stolen with fear and astonishment.

“Ah, ah!” The creature looked back, and watched its dream creation dissolve: the sea, the swimmer, the storm. Unable to stare into the face of its cosmic fantasies the creature hung its head in frustration at its own timidity. This dream had been good, the aeons of sleep had fashioned so much detail from the dark waters of the universe, and the little swimming creature had been so real. But now it was all gone, and he would have to start again.

[ends]

More in two weeks, (more from What is Time? next week)

There are many other stories in this series, including:

Time Thief

Butterfly

Ophelia A.I.

Helm

Deadly Survey

Masks

Henge

Here’s a related post, 5 Steps to the SF and Fantasy Podcasts

And a post on the life, work and gothic inheritance of H.P. Lovecraft.

Filed under: Microfiction, Podcasts Tagged: Cthulhu Mythos, Dark fantasy, dystopia, gothic, H.P. Lovecraft, Horror, podcast, post-apocalypse, sf fiction, Supernatural

August 11, 2015

What is Time? Time and The Calendar

In the time of dreams, two brothers, the Bagadjimbiri, come out of the earth as dingoes. They turn into two giants in human form and grow so tall that their heads touch the sky. Nothing exists before this: no trees, no animals, no people. The brothers come out of the earth just before the dawn of the first day. A few moments later they hear the call of a little bird, the duru, which always sings at the break of day, so they know it must be dawn. They see plants and animals and give them names. Once named, they come to life.

This Dreamtime creation myth from the Karadjeri Aboriginals of Australia is retold, orally, always in the same form, with the storyteller connecting to and being part of this beginning of time, at once inside the past and a part of the present. The Karadjeri believe that at the point of creation a fundamental rhythm is established, the call of the little bird at daybreak, so that a definition of time is imposed on humankind by the natural order of things.

Origins of the Modern Calendar

The history of humankind’s measurements of days, months and years is the history of civilisation and, the conflict between sacred and secular political forces. It has propelled us through a history of ideas and understanding to a point at the start of the third millennium where we can measure the beginnings of the universe itself, rather than just rely on articles of faith, myth or simple conjecture.

Our view of our place in the universe has moved on from the geocentric perspective of our forbears.

Our view of our place in the universe has moved on from the geocentric perspective of our forbears.The Ancient World, with its immense reserves of knowledge stretching from the ancient Chinese to the Greeks, Babylonians and Vedic Indians, struggled to explain the rhythm of the year using mathematical and astronomical observations that were, by the end of the first millennium, the envy of an embarrassed Europe cloaked in the Dark Ages. The balance of knowledge then shifted, with ideas and learning flooding through Europe, resulting in the powerful cultural synthesis of the Renaissance and ultimately causing the separation of sacred and secular authority over the instruments of time. This is significant because religion and what has been termed organised superstition had played the primary role in controlling the lives and minds of humankind for as long as the skies and the stars have been relied on for succour and inspiration.

Definitions of the Astronomical Year

There are many different types of year, and the differences fuel the twists and turns in the story of time and the calendar.

The length of the year depends on where you measure it from. Our perceptions of time have changed and developed as science and technology have improved the accuracy of its measurement over the past 4000 years.

Lunar Year

This is the most easily observable type of year and it formed the basis of many cultures’ early government of time. As each month starts at the new moon and lasts for 29.5306 days this was generally translated into alternating months of 29 days (hollow months) and 30 days (full months). This gives a year of 354 days: too short by 0.3672 of a day of the true lunar year, so in order to redress the balance, a leap day every third year had to be inserted. (The addition of days or other units, like seconds, to balance the calendar, is known as an intercalation.) To make this calculation more accurate, a further leap day would have to be added every 10 years.

Over time, lunar years become out of sync with the seasons which are determined by the solar calendar. Several cultures, including the ancient Chinese and Greeks, used a combination of lunar and solar years by adding leap months and combining the seasonal cycles with the moon’s phases (the time from one new moon to the next), creating in one common solution a 19-year solar cycle which coincided with 235 lunar months.

Solar Year

There are a number of recognised forms of the solar year, all necessary because of the slightly elliptical rotation of the earth around the sun:

The tropical year – marks the year of the sun’s passage between two vernal (spring) equinoxes. The seasons are fixed and the length of the year is 365.242199 days. Generally speaking tropical year is used when the solar year is discussed.

The sidereal year – marks the passage of the sun relative to a fixed star. The length of the year is 365.256366 days.

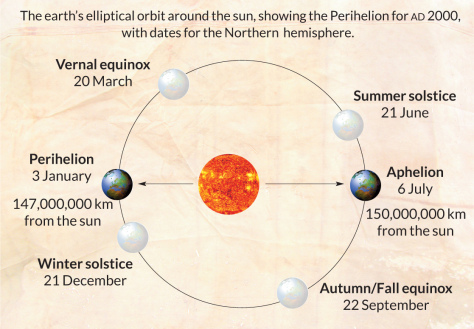

The anomalistic year – marks the passage of the sun at the point of the perihelion, when the earth is nearest to the sun. The length of the year is 365.259636 days.

The Perihelion for 2000 CE

The Perihelion for 2000 CEThe next post looks at the use of different calendars.

Some other posts of interest.

The first post in the What is Time? sequence

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Only Connect, the Creative Melting pot of 1910 and Modernism

Fibonacci 0

Micro-fiction podcast: Time Thief

The image in the head of this post is Inapaku Dreaming by Malcolm Maloney Jagamarr. Interviews with the artist appear here.

Filed under: Science, Time Tagged: Buddhism, calendar, days of the week, medieval, millennium, religion, science fiction, space-time, Taoism, Time, Time and the Calendar

August 4, 2015

Micro-fiction 025 – Southern Gothic (Echoes series)

Ghosts stalk the swamps as the past rises from the deep, with memories of shame and old dreams .

Echoes | Southern Gothic

The chair creaked as she eased back and forth in the heat, at the end of the day. This white board house, built on the edge of the swamp when the price of land was cheap, now was a curse, impossible to sell, impossible to inhabit, and stalked by the creeping bayou.

She looked across at her brother. His contorted body reflected back the years, perspiration draining down the edges of his stiff collar. He had been a slaver. And paid for it. Not like the beatings, and worse he had dealt to his people. She looked at his limpet eyes, and crumpled shell, and remembered the day of dissent, when everyone on the plantation had stopped, too tired to continue, resigned finally to their death, and joined together in a mournful chant that stirred across the rice fields, murmuring and churning the swamp with their utter exhaustion.

“Well, Mary,” she remonstrated with herself, “I was just a little girl. What could I have done. Louis was determined to prove himself.”

She remembered standing close to her present position on the porch, looking out to the fields, where suddenly she observed the men, their bodies drenched in the heat of the summer, standing like the cypress trees and tupelo of the swamp, with their heads held high, their mouths open to the skies, their tools broken or discarded. To her imaginative eyes it was a vista of old ghosts stretching back into the horizon, of the swamp returning to reclaim its land, shimmering in the heat, calling for mercy, and the blessing of death.

But her brother, overfed since birth like a Christmas Turkey, had stumped to the cellar and picked up his father’s rifle and a long knife. Since his pa had died, a vile man with sadistic tastes that brought him respect from the wrong quarters, little Louis had been desperate to demonstrate that a fourteen year old boy was as much the master of this plantation as his mad old dad. And so, with the fever of the sun in his eyes, and the dark temptations of the swamp in his soul he decided to show them.

“It really was the hottest day of the year.” Mary muttered to herself, waving, as she did then, at the corpse flies, and the mosquitos that invaded the most private places. She recalled that day, when nobody wanted to move. But the men in the field and the swamps were expected to continue with their duties, their heads slung low, struggling, she noticed, to breathe in the thick air, taking a moment to gather their strength, to draw on generations of stoicism and fear.

And so her brother, drunk on the heat, and the responsibility burdened upon himself, lumbered his fat frame down the front yard and out into the swamp. He found two of the men malingering, wiping their brow. He shot them, while their backs were turned against him. Mary put her hand to her chest as she did then and watched him wade through the thick waters, heading to the group of men assigned to clearing the waterways on the edges of the fields, their boney chests dripping with sweat. They stood next to the fallen branches that gripped the cool underbelly of the bayou.

“Little Master,” one of the men leaned over, his red eyes wary and tired, he had worked for the family for a generation, his children born into slavery and even now learning survival at the table of deference, “why don’t you go home, it’s too hot for one such as yourself.”

Of course, the little master, so eager to prove himself at the alter of righteous fury announced to them all, “why don’t you just get on with your damned jobs instead of idlin’ here: the heat should be no trouble for people such as you, my father used to tell me so.”

“Ah, indeed, your father.” One of the slaves, slightly smaller than his companions and a little less cautious uttered sagely to his fellows.

The little master was trained by his father to pick up on such inflections of dissent. “What did you say about my father?”

“I didn’t say anythin’, little master.”

“I heard yer words, you worthless whore of satan.”

The first of the group stood a little taller, and took an affronted air. “Little master, that’s no way to speak to a God-fearing man.”

“How dare you question––.” Louis, his face red with heat and anger, spat into the waters. “You, worthless––” The boy yelled at the perplexed group in front of him.

The tallest of them looked across at his fellow who was now fidgeting his hat, pulling it from his head to expose a bald pate to the unforgiving sun, and watching it flap before him. “Sir, no offence was intended, I’m sure.” It was clear to the impartial observer that this was so.

But somehow little Louis responded to this as an act of war. “First you disrespect my father,” he shouted, his eyes bulging in the heat, “and then you dare, still, to question me?” He bellowed, his porcine frame well suited to the braying. But then he drew his knife, and set about the man whose hat had, for a brief moment exhibited an uncharacteristic taste for freedom. The boy, large for his age, and reckless in his manner performed his frenzied act with such efficiency, that the group around him could only gape in awe. After the ordeal, the hat, flecked with blood and perspiration had drifted back into the swamp to pursue its final journey toward the children and wife of the wronged man.

And so the chanting had started, a deep, woeful hollering that endured for hours. It rolled across the fields, slithered across the choking cypress trees, and oozed into the matted fur of the swamp rats and the ailing lilies, sinking into the intestines of the submerged forest of the swamp where it slowed, clung to the remnants of its origins, then dispersed into the deep whispers and subtle rumbles of the land. This was the long call of death, for Louis went on a rampage and hacked down the men, one by one.

By nightfall it was over, the chanting had stopped, the faint echoes only rustling in the dark vegetation around the fields. Louis returned, exhausted, triumphant, covered in the suffocating tendrils of slimey, organic matter, and in the dark waters of the slaughtered men.

From that point on, the bayou seemed to gain in strength, sustained by the woe and misfortune within. Mary imagined that a person might now get lost in the swamp, and die, but still dream of life and leer across the living at twilight.

***

Years later, the bones of slavery long buried, in law at least, the family retained its flimsy grasp on the immediate land around the slowly disintegrating home. Without the manpower of the slaves the swamp groves had reclaimed their former splendour, and now gathered about the white board house, no longer subservient to the whims of a man’s anxieties.

Mary sighed. No children illuminated the house. No neighbours were left to visit and carouse. Just Mary and her brother Louis. She looked at him, curled in his basket-weave chair, a shrivelled version of the young man who had pretensions to rule the plantation with his rifle and his temper.

But she had observed the events of her long life, and now, at eighty years old, she shed the ennui of her youth. Her brother had become a relic, an ornament in the landscape, and she knew her fate would be the same. Soon this house, and all its contents would be overwhelmed by the bayou, and returned to the natural order, to the darkness, to the shadows in the waters, and the heat, always the heat.

With the memories of that fateful, deadly day fresh in her head, she realized that she despised her brother. She stood up, and decided to lock the door to the back porch, behind her, and leave this ghost, her brother to his misery, just one last time. In the morning, he would be gone, burned up by the rising sun, and the vengeful call of the bayou.

[ends]

More in two weeks, (more from What is Time? next week)

There are many other stories in this series, including:

Time Thief

Dark Blood

Ophelia A.I.

Helm

Deadly Survey

Masks

Henge

Here’s a related post, 5 Steps to the SF and Fantasy Podcasts

Filed under: Microfiction, Podcasts Tagged: Dark fantasy, dystopia, gothic, Harper Lee, Horror, Mockingbird, podcast, post-apocalypse, sf fiction, Supernatural, swamp