Jake Jackson's Blog, page 16

March 29, 2016

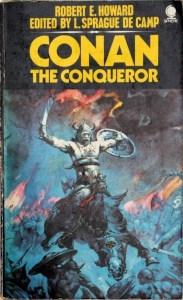

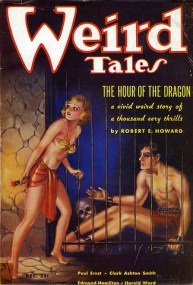

100 Top SF & F Books. Conan the Conqueror. Robert E. Howard

Conan: adventurer, mercenary, reaver, butcher of wizards and demons, in this short paperback we meet him late in life, as King of Aquilonia, his rule threatened by dark forces beyond the understanding of humankind. Howard delivers Conan’s trademark taciturnity, a warrior who doesn’t think or emote too much, but acts decisively and lustily.

This was my first introduction to the gritty realism of Conan and the sweeping tales of Hyboria. I picked up this edition in the 70s during what I now know to be the first Robert E Howard Boom. I read the comics, all the books, saw the bombastic Kull movie, then later, the moody Schwarzenegger film. Conan’s world was so far from my own it gripped me with its thrilling, dirty fingernails. Now I can blame it on the rejection of a picture I submitted to the school magazine with an ill-advised scene of Conan flavoured mysogyny. Thankfully, I’ve grown up now…

The Hour of The Dragon

Weird Tales 1935 Hour of the Dragon by Robert E Howard, and a Clark Ashton Smith contribution.

Originally published as Hour of the Dragon, in serial form in the Weird Tales from December 1935, just before Howard’s death a year later. Conan the Conqueror, along with others published in the 1960s and 70s, is interesting because it’s not entirely Robert E Howard. Somehow that revisionist fraud L. Sprague de Camp had inveigled himself into the literary crevices of the father of Sword and Sorcery and ‘cleaned him up’, tidied what he saw as inconsistencies and other infelicities, and, even, claimed copyright. Such hubris!

Conan, Krenkel, Frazetta and Howard.

Anyway, at the time, the Frazetta cover (and the reference to the masterful Roy J. Krenkel as adviser), the discovery of this dangerous new world (more savage even than Tarzan) pricked at my young head and filled it with reavers and desert plains, ancient gods of Cimmeria, and a feverish swirl of heroic fantasy, black magic and a very male form of misplaced determination. I loved it, and part of me still leans heavily into sword and sorcery which seems to go in and out of fashion every decade or so.

I thought long and hard about this. Subsequently I’ve read Howard’s originals, but this book, along with Conan the Avenger and others in the series, must be part of my 100 best because they formed an indelible influence on my mental landscape. Probably in the top 10, unless Orson Scott Card’s Ender series edges him out, or Bradbury’s Illustrated Man. We’ll see.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. American Gods. Neil Gaiman

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

Robert Louis Stevenson: Master of Victorian Gothic

Dark Fantasy

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 Top SF & F Books. Conan the Conqueror. Robert E. Howard appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

March 24, 2016

William Morris: Utopia, Industry and Art

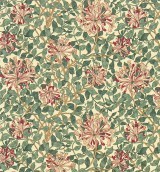

The works of William Morris pulsate with energy, passion and inventiveness. His appeal, still strong today through the medium of his designs for wallpapers and fabrics, derives from the breadth of his achievements, a concern for his fellow man and the powerfully sympathetic response to nature which fed the swirling patterns of his decorative designs.

Poet, painter, designer, typographer, polemicist, manufacturer and Socialist, Morris leapt from one enthusiasm to another, living his life with a restless energy that led him constantly to seek and solve new challenges. At his core was the commitment to a basic philosophy that good design came from a good society. He was a warm, generous man prone to enraged frustrations, a sensitive man who could be brutal in his constant grip on quality. His mastery over one craft after another ensured his absolute dominance in the field of the decorative arts where he is still regarded as the greatest British pattern designer.

His contemporaries viewed him with a mixture of reverence and affection. The designer and teacher William Letharby, a prodigious talent himself, declared that Morris was the ‘…greatest pattern designer we have had or ever can have, for a man of scale will not again be working in the minor arts’. W.B. Yeats, in Autobiographies 1955, said that

‘…if some angel offered me the choice, I would rather live his life, poetry and all rather than my own or any other man’s.’

Bernard Shaw wrote that Morris was

‘…great not only among little men but among great ones’.

These observations, from men of very different disciplines reveal the strengths of Morris. To all appearances the scale of his interests and achievements can be daunting if taken methodically, one at a time. To do so would undermine the essential diversity and range of a man whose doctor reported that the cause of death was ‘simply being William Morris, and having done more work than most ten men.’ Morris toiled with a rumbustuous joy that drove his broad creative energies hard.

To many he seemed like a Renaissance Man, which was ironic because he detested the period and all it stood for, and yet he was straightforward in his motivations, above all a designer, signing himself as such when he joined the Democratic Federation in 1883. This essentially simple vocation informed his thinking and absorbed his attention : for Morris there was a strong moral association between the artist and his work. He believed that true artists were people who could express themselves completely through the material they worked with, benefiting from the full value of their labours. He did not, however, fully express himself in any one activity, settling instead for a complex vortex of crafts, arts, literature and politics as though no single medium could contain the passionate committed turmoil of his imagination.

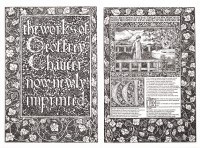

Morris and The Victorians

It is ironic that the name William Morris is linked with the notion of Victorian design. This would have enraged Morris. His philosophies on the rightness of art, the value of human endeavour and the corrupting nature of manufacturing from profit runs in direct opposition to Victorian society. The artifice, indulgence and shoddy workmanship represented by industrial advances were anathema to him. He preferred sentiment to sentimentality, natural simplicity to artificial profusion. Such tensions gave rise to much of his greatest work, ranging from the beauty of the Kelmscott edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the burgeoning tendrils of the wallpaper design Honeysuckle and his strident lectures on art and democracy in the 1880s.

Morris fulminated against the dehumanising industrialisation that fuelled the economy of the British Empire. He did not object to the machines themselves but their use by some to produce profits through the exploitation others. This was part of an holistic world view which saw art as a litmus test for the health of the nation. ‘Unless people care about carrying on their business without making the world hideous, how can they care about art?’ he declared. The production of shoddy goods for the express purpose of making only profit led to a decline in the moral standing of those who were forced to produce them. Only by making, for instance, furniture, honestly with a true joy in the craftsmanship and a share in the benefits in making it, could people become true to themselves.

Medieval Authenticity

Morris, like many of the thinkers and artists of the day, looked back to the pre-industrial middle ages where a sense of natural order prevailed, where there was respect for the countryside and an understanding of the value in a craftsman’s work. Like the poetry of Tennyson, the music of Wagner and the paintings of Millais, Morris sought to express his vision of the world through an ideal medieval landscape, turning, initially, from the squalor of the nineteenth century to an escape into romance, mythology and chivalry.

Later, equipped with the experiences of his exceptional life he sought to change the world he lived in rather than seek a temporary escape from it. He harnessed the lessons of the past into a unified vision of society where art was intrinsic to everyday life. This was a search for a better life through constructive criticism, positive action and by example. Morris saw no difference between the maker and the thinker, the artist and the politician because he was all of these things himself and he understood that relative values were false, that the skills of one contributor to society such as a thinker like Thomas Carlyle or John Ruskin were no greater than those human skills of making a chair or a painting. He rarely compromised on his strong sense of vision, which included the requirement to think and feel through the raw materials:

‘Never forget the material you are working with, and always try to use it for what it can do best.’

This came partly from a desire to reflect the flowing lines and rough fluidity of the natural world. He drew a precise and lyrical pleasure from the whole process of designing his patterns, ranging from the research of natural and historical references to the physical mixing of the colour for the cloth.

Morris & Co

William Morris was a rare and genuine force of cultural change, a central figure in the development of modern culture. He was an entrepreneur of unusual creativity, surrounding himself with a cauldron of talented people both as friends and memebers of his company Morris & C; Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ford Madox Brown, Philip Webb and Arthur Mackmurdo were all drawn to and sympathetic with his rebellion against Victorian values. The clarity and honesty of his approach enabled these men and many others to define their own revolt against the Age and turn it to a more worthy future. Morris’ own fiction, including the influential News from Nowhere (1890), and his achingly difficult epic poetry brought his ideals, and Utopian instincts for hard work, honesty and creativity to an audience which was probably more interested in the beautiful designs of his wallpaper!

Links

Other posts of interest in These Fantastic Worlds include:

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

Henry Fuseli: Dark Gothic Fantasy

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF Classics

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

Frankenstein by Jeffrey Catherine Jones

H.P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

The post William Morris: Utopia, Industry and Art appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

March 22, 2016

Fantastic Quotes 01 | Aldous Huxley

“Maybe this world is another planet’s hell.”

Aldous Huxley

#FantasticQuotes

The post Fantastic Quotes 01 | Aldous Huxley appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

March 10, 2016

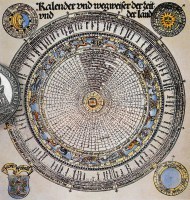

What is Time? The Gregorian Calendar

From 1540, two major developments brought long-lasting change to our notions of time. The calendar reforms of Pope Gregory gave us the Gregorian calendar we have today, and the ultimate acceptance of the heliocentric system (that the earth circulated the sun, not the other way round) provided a victory for science over the Catholic Church.

Copernicus’ Radical Idea

Polish astronomer and monk Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) used his knowledge of recent mathematical advances in Western understanding to predict the motion of the planets more accurately. He concluded that the earth and the planets must revolve around the sun. He was reluctant to publish his findings for fear of the criticism his theories might generate from astronomers and from the Catholic Church. It was, however, over 70 years after his death that the Church first condemned his work.

For centuries this heliocentric system had been known to scholars in the East and to some in Europe, but the Church based its worship on the fact of God creating the earth and therefore explicitly making our planet the centre of the universe. This was supported by Christian philosophers who adopted ancient Greek Aristotelian and Ptolomeic concepts of the sun and the universe revolving around the almighty earth (the geocentric system). Any threat to this was deemed heretical. Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), the celebrated Italian astronomer and mathematician, initially supported Copernicus’s work, but was forced to recant in 1633 in one of the last great efforts of the Grand Inquisition to halt the march of scientific progress.

For centuries this heliocentric system had been known to scholars in the East and to some in Europe, but the Church based its worship on the fact of God creating the earth and therefore explicitly making our planet the centre of the universe. This was supported by Christian philosophers who adopted ancient Greek Aristotelian and Ptolomeic concepts of the sun and the universe revolving around the almighty earth (the geocentric system). Any threat to this was deemed heretical. Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), the celebrated Italian astronomer and mathematician, initially supported Copernicus’s work, but was forced to recant in 1633 in one of the last great efforts of the Grand Inquisition to halt the march of scientific progress.

The Triumph of Science

After the discoveries of Copernicus, the German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), with his important work on the elliptical planetary orbits, and Galileo’s telescopic observations generated much work on the motion of planets through to Isaac Newton (1642–1727), who established the fundamental concept of gravity and formed the basis of modern scientific observation.

Copernicus’s calculations in his De Revolutionibus demonstrated how far the West had finally assimilated the knowledge of the East. He showed, for instance, the solar year to be 365.2425 days long, only 35 seconds out by our current reckoning. At last, Europe finally recovered from the fall of Rome, some 1200 years before, having lost in the Dark Ages, the knowledge inherited from the ancient Egyptian, Greek, Sumerian and Indian civilisations. Observations of differences between the lunar, sidereal and solar year had become increasingly obvious, and could now be resolved.

Pope Gregory

Pope GregorySo, the Church, in the form of Pope Gregory XIII (1502–85) acknowledged that the cumulative errors of Julian calendar (Easter, Christmas, Saint’s days) undermined its authority. Since the 1450s, printed calendars had been distributed to anyone who wished to use them, using the new technology of printing on paper, putting further pressure on the Church to be accurate. Pope Gregory set up a calendar commission, consulted widely with church and state authorities and eventually published his Papal Bull of 1582 which transformed the official calendar.

Core Gregorian Reforms

New Year’s Day was established as 1 January.

Ten days were to be lost, 5–14 October.

Leap days were to be inserted after 28 February every four years, except those divisible by 100, but not 400 (i.e. 1900 was not a leap year, but 2000 is).

Easter dates were recalculated against a complicated formula which compensated for differences between the solar, sidereal and lunar years, the different observations of which had originally prompted the gathering call for change.

Acceptance and Denial

It took nearly 400 years for the Gregorian calendar to be accepted throughout the Christian world, and the story of its acceptance reflects the continuing conflicts of faith within the Christianity and the political machinations of its secular partners.

Most Catholic countries adopted the reforms within the first year, although a further order had to be issued suspending days in February.

In the first wave were France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Poland and Luxembourg, followed by Sweden, Bavaria and Austria.

The Netherlands, Belgium and Catholic Germany agreed in 1584, Hungary in 1587.

Other countries followed at a very different pace: United Kingdom 1752, Japan 1873, Egypt 1875, Eastern Europe 1912–19, including Russia in 1918.

China adopted it in 1912, but it took the overthrow of the Nationalist government by Mao Zedong in 1949 to enforce countrywide change.

Rejection

In the first years, while Catholic states accepted the changes the Protestant countries, such as Britain and much of Germany, took much longer to agree to the need for change. This was because the Catholic pope was seen as trying to exert his authority over the whole Christian community after the splits of the Reformation.

This prolonged process of adoption and rejection led, in England, to two centuries of parallel calendar notations, with letters and documents recording ‘Old Style’ (OS) and ‘New Style’ (NS).

New Year’s Day was also erratically enforced throughout the Christian world with 1 March, 25 March and 25 December also being used. This all changed, though, by the time the last major European power, Britain, finally joined the Gregorian scheme in September 1752, bringing, with it the colonies, especially the increasingly influential North America.

The English Mob

Voltaire’s famous jibe, that ‘the English mob preferred their calendar to disagree with the sun, than agree with the Pope’ was entirely accurate. Although the English court, since the brief reign of the Catholic Mary, had been a cauldron of murderous prejudice both for and against Catholics, Queen Elizabeth I had been consulted during the reform process and all her senior astronomical and scientific advisers agreed with the calculations and the need to change. The newly formed Church of England however, did not, particularly because the most recent Papal Bull had excommunicated Queen Elizabeth for establishing the new Church in place of the papal, Catholic authority. The position was not helped by the attempted Spanish invasion of 1588 which had the blessing of the Catholic Church.

William Hogarth, 1750

Eventually, in 1750, the Calendar (New Style) Act was passed, invoking Roger Bacon’s influence on the reforms, instructing the loss of 3–13 September 1752, one day more than the original reform because the errors of the Julian calendar had pushed the date of Easter even further back.

It is difficult to imagine the strength of feeling, but there were riots in Bristol with people shouting for the return of their 11 days. There were quiet revolts too, of the bankers in the City of London: the changes meant that they would have had to pay their taxes 11 days earlier than the normal year end, which for centuries from the days of the early Saxons had been 25 March (Lady Day or the Feast of the Annunciation, the apparent date on which Jesus Christ was conceived and hence an appropriate start to the year). Prudently, they refused to lose the 11 days of interest on their money, paying on 5 April, creating the precedent which still gives us this date as the end of the financial year.

The Eastern Orthodox Church

Since the excommunications and consequential divisions of the eleventh century, co-operation between the two main limbs of Christianity – the Catholic and Eastern orthodoxy – was at best grimly courteous. At the time of Gregory’s papacy, the Eastern Orthodox Church remained at odds with the Catholic Church over its lack of support during the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453.

Eventually, in 1923, the Eastern orthodox faith adopted the majority of the reforms, but its calculation of leap years is based on a different system (bringing it slightly closer to the true solar year than the Gregorian) and their Easter dates retain the Julian calendar method, with the result that there can be a five-week difference in the Easter dates of the Catholic and Orthodox Christian countries.

Calendars and the Modern World

The struggle to adopt a calendar that reflects the world around us has been long and difficult, a 400 year journey of conflict between the spiritual, the political and the everyday. During that time the conflict between and within religions, and increasingly with science has intensified as technology accelerates our powers of observation and analysis.

The next post on Time will provide a quick summary of calendars before we move off to the more intimate subject of clocks!

Some other posts of interest.

The first post in the What is Time? sequence

What is Time? Julian Calendar

What is Time? Ancient Calendars

What is Time? Beginnings of Our Time

What is Time? Time and the Calendar

What is Time? Lunar vs Solar Calendar

What is Time? The Dark Ages

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Only Connect, the Creative Melting pot of 1910 and Modernism

Fibonacci 0

Micro-fiction podcast: Time Thief

The post What is Time? The Gregorian Calendar appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

February 29, 2016

Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books. Dune by Frank Herbert.

Dune. Forget the movie and the mini-series, just read the book. It’s an epic sf read of Shakespearean proportions and delves into every crevice of life. Grander than Game of Thrones, more sweeping than Star Wars, as fundamental as a religious text Dune has the power to enthral, and that’s just what it did to me when I was young and picked up this battered 1970s edition on a can-kicking Saturday at my local SF store.

Dune: SF on a Grand Scale

Dune: SF on a Grand ScaleAlthough Herbert’s masterpiece is dressed as an SF space opera, it revels in the diversity of humankind: think War and Peace without the shadow of the Russian revolution. It takes the machinations of the Atriedes dynasty and their conflict with their Harkonnen rivals, with its echoes of the Plantagenets vs the Tudors in Medieval Europe, and mixes in a strong dose of cosmic drug trafficking reminiscent of the insidious Opium trade in the China in the late 1800s. Then Herbert turns it into a saga of prophecy, mysticism and Fate, with all the battles and adventures you’d need to keep the reader turning the page. Oh, and throw in some loss, grief, hope and love!

Paul Atriedes

The main protagonist Paul Atriedes is a spoilt child to some, a solider to others, a prophet, a friend, a scheming opponent, a strategist, he’s a human laid bare in a mirror ball of relationships. I’ve read this, and the other books in the canon three times now, at different ages, and still find new insights into Atriedes’ preogression from outcast, to prophet, then ruler. And there are so many other threads: his duplicitous mother, her treachery of the Reverend Mothers, the Spice (essential for interplanetary travel, and a powerful hallucinogen), the blue eyes, the tribes, and, above all, the mighty, roving sand-worms.

So Dune has it’s flaws (the best women are the bad ones, the love interest is mainly a naked plot device) and it’s longer than is sane, but oh what a book, it still gives me goosebumps. In the top ten of course, higher I’m sure once this is all over.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Top 100 SF & F Books. The Rebel Worlds (Poul Anderson)

Top 100 SF & F Books. The Subtle Knife.

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF classics

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books. Dune by Frank Herbert. appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

February 18, 2016

100 Top SF & F Books. Blackmark by Gil Kane.

Blackmark is the creation of masterful artist-storyteller, Gil Kane. It’s a rare beast, and you won’t find it in many top SF and Fantasy lists. However, for me it brings together so many genres (Sword and Sorcery, SF, Wild West), and expresses the mix with great power: in a post apocalyptic world, brought to its knees by the banished forces of science an unlikely hero rises from the brutality of a miserable life, to conquer all and become King. Hardly an archetype, but utterly compelling.

Blackmark is the creation of masterful artist-storyteller, Gil Kane. It’s a rare beast, and you won’t find it in many top SF and Fantasy lists. However, for me it brings together so many genres (Sword and Sorcery, SF, Wild West), and expresses the mix with great power: in a post apocalyptic world, brought to its knees by the banished forces of science an unlikely hero rises from the brutality of a miserable life, to conquer all and become King. Hardly an archetype, but utterly compelling.

Innovative Blackmark

That said, the story is rather less important than the manner of its telling. It’s one of the earliest attempts at the first graphic novel form, with a courageous mix of prose blocks and comic frame narrative, all black and white with Letraset tones for shadows, like a mad newspaper strip. Re-reading it now the details of the birth in poverty of hero-to-be-King, the rediscovery of a rocket ship buried in the middle of the land, and the string of desperate battles bring the book into the realms of Game of Thrones, ERB’s John Carter of Mars, Star Wars and Robert E. Howard’s enduring creation, Conan. For today’s cinematic-reared audience, fed on a diet of streaming video Blackmark will seem thin gruel but emerging in the early 1970s, when paperback fiction was the engine room of SF and fantasy (Frazetta covers, Michael Moorcock’s Elric, and Marvel’s upmarket magazine-comic Epic) Gil Kane’s experiment in crossover fantasy was thrilling.

Marvel, DC & Beyond

For many Gil Kane was a direct successor to Jack Kirby, with his bold, direct lines, and pacy sense of story-telling. His Spiderman, Iron Fist and others for Marvel, Green Lantern, Wonder Woman and Superman for DC brought him to the zenith of the superhero market during a golden period of comics, now long supplanted by the mobile and movie technology of today.

The story was re-issued years later in true comic and graphic novel style (by Fantagraphics I think), with the unpublished second book in the series, but I bought mine second-hand in the 1970s, along with various Robert E. Howard paperbacks, and still treasure its gracefully yellowed pages. Definitely in my top 100 SF and Fantasy books.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Top 100 SF & F Books. The Rebel Worlds (Poul Anderson)

Top 100 SF & F Books. The Subtle Knife.

The Avengers: A Back Story

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 Top SF & F Books. Blackmark by Gil Kane. appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

February 11, 2016

100 Top SF & F Books. The Subtle Knife. Phillip Pullman

The second book in Pullman’s Dark Materials trilogy The Subtle Knife is a roaring good read, and a sophisticated modern fantasy. Originally I bought the edition here for my son, 12 at the time, but he was rather less interested than I was, mainly, as I now discover, because he didn’t share my taste for science fiction and fantasy.

Fantasy for Children?

It’s also a mistake to classify this as a children’s book (many so-called children’s writers would say the same about their own work). For those not particularly keen on fantasy there’s a tendency to equate triviality with the genre, especially if the main characters are children. Of course any cursory reading of Pullman will reveal a strong philosophical thread, and a desire to challenge which an enquiring reader of any age will enjoy. The character of Will Parry, a young lad from Oxford, and Lyra, with their adventures flitting between worlds, remind me of Little Dorrit and Pip in Great Expectations (Dickens’ children are often perfectly etched) and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies with its community of children attempting to run their own lives. Pullman though brings his pacy narrative into the modern world with flourishes of mystery that keep the interest flowing throughout.

Fantasy Greats

Dark Materials is sometimes considered to be one of the great fantasy sequences of our time, but it falls behind Tolkein’s ground-breaking high fantasy, and J.K. Rowling’s hermetically sealed magical creations perhaps because it deals so transparently with big issues, attracting more criticism than affection. However, strong central ideas, such as the use of the knife itself, the clustering of dust (a sort of dark matter) and the marvellous daemons, probably brings this particular book into my top 20, perhaps top 10 on this gathering list of 100 best SF and Fantasy books.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. American Gods. Neil Gaiman

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

Robert Louis Stevenson: Master of Victorian Gothic

Dark Fantasy

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 Top SF & F Books. The Subtle Knife. Phillip Pullman appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

February 4, 2016

100 Top SF & F Books. The Songs of Distant Earth. Arthur C Clarke

Arthur C. Clarke demands to be taken seriously. His fiction operates on the grand scale, employing meticulous scientific knowledge to create a series of “what ifs?” based on plausible technological, psychological or ecological events. Sometimes he offers too much detail, and forgets about the storytelling part of his fiction – I re-read the RAMA series recently, and struggled with its dry tone – but The Songs of Distant Earth has always appealed to me, and, apparently, was Clarke’s own favourite.

Future Earth

Taking place far into the future, from the middle of the 3600s the plot follows a pleasing logic: humankind identifies our sun will die, and so, naturally, to survive it must leave the solar system. Over hundreds of years interplanetary missions depart to seed other worlds, using ever more advanced technology. The book traces the consequences of existential threat and the creation of new civilisations from scratch, focusing on one colony (on the beautiful Thalassa) that thinks it’s the last outpost of human life, until a visit by the final ship to leave earth arrives. The Magellan, a starship holding a million people, is a shock to the people of Thalassa whose perfect lives are disturbed and excited in equal measure.

Micro vs Macro

Clarke offers a decent balance between philosophical questions about humanity’s purpose and place in the universe, and individual psychological strife. In his refracted, dispassionate style most of his books play with the micro human vs macro universe conundrum, the comfort of society and companionship vs the severe indifference of the cosmos. Notably contemptuous of religion, there’s (always in his work) an awkwardness about his characters which, for me at least, stems from his dismissal of this fundamental motivating force in many people’s lives. Perhaps it’s not a major criticism though – it allows him to explore the issues of humanity, survival and isolation by concentrating exclusively on pushing at the limits of science.

The Song of Distance Earth is an enticing, enjoyable read, and a leap forward from the bleak enigma of the better known 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time

Harry Harrison. R.I.P.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 Top SF & F Books. The Songs of Distant Earth. Arthur C Clarke appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Arthur C. Clarke demands to be taken seriously. His fict...

Arthur C. Clarke demands to be taken seriously. His fiction operates on the grand scale, employing meticulous scientific knowledge to create a series of “what ifs?” based on plausible technological, psychological or ecological events. Sometimes he offers too much detail, and forgets about the storytelling part of his fiction – I re-read the RAMA series recently, and struggled with its dry pace – but The Songs of Distant Earth has always appealed to me, and apparently, was Clarke’s own favourite.

Future Earth

Taking place far into the future, from the middle of the 3600s the plot follows a pleasing logic: humankind identifies our sun will die, and so, naturally, to survive it must leave the solar system. Over hundreds of years interplanetary missions depart to seed other worlds, using ever more advanced technology. The book traces the consequences of existential threat and the creation of new civilisations from scratch, focusing on one colony (on the beautiful Thalassa) that thinks it’s the last outpost of human life, until a visit by the final ship to leave earth arrives. The Magellan, a starship holding a million people, is a shock to the people of Thalassa whose perfect lives are disturbed and excited in equal measure.

Micro vs Macro

Clarke offers a decent balance between philosophical questions about humanity’s purpose and place in the universe, and individual psychological strife. In his refracted, dispassionate style most of his books play with the micro human vs macro universe conundrum, the comfort of society and companionship vs the severe indifference of the cosmos. Notably contemptuous of religion, there’s (always in his work) an awkwardness about his characters which, for me at least, stems from his dismissal of this fundamental motivating force in many people’s lives. Perhaps it’s not a major criticism though – it allows him to explore the issues of humanity, survival and isolation by concentrating exclusively on pushing at the limits of science.

The Song of Distance Earth is an enticing, enjoyable read, and a leap forward from the bleak enigma of the better known 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time

Harry Harrison. R.I.P.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 Top SF & F Books. The Songs of Distant Earth. Arthur C Clarke appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

January 27, 2016

Robert Louis Stevenson: Master of Victorian Gothic

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (1850–94) was born in a dank and cold Edinburgh, but travelled greatly in search of less brutal weather, finally to pass away in the temperate climes of Samoa. For today’s reader his reputation as a writer of adventure fiction is well established but as a poet, essayist, travel writer and masterful short story writer his range was great and varied. In his time, he was a popular author and associated with many of the most notable writers of the late Victorian period, although the elitism of some contemporary literary critics sought to bury him with the Romantics until his reputation was rescued in the twentieth century, as a skillful storyteller of the gothic and fantastic.

Early Years

Born to respectable parents at the height of the British Empire, Stevenson’s ill health led him to spend much of his time reading, or being read to, frequently unable to join his peers at school. His grandfather was Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University, his father a civil engineer of over 40 prestigious lighthouses, so there were great expectations for the young Stevenson. However his mind was saturated by the works of Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, John Bunyan, The Arabian Nights and the elaborate, moralising fairy tales of Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. His early instincts for storytelling were clear, in spite of the best attempts of his family who expected him to pursue a career in science.

Initially he consented to the study of engineering at the University of Edinbugh from 1867, but soon found the pull of literature to be too seductive. His parents were horrified at the prospect of their son relying on the unstable, and distasteful, pursuit of writing as career, so collectively they managed a compromise: Stevenson would study law instead. He was called to the bar in 1875, although never practised.

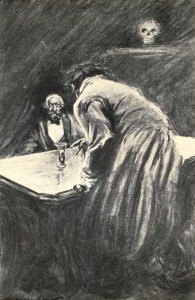

Illustration by Charles Raymond Macauley for the 1904 edition of The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Published by Scott-Thaw

As he grew into adulthood Stevenson’s conflicts with his parents – his father in particular, and all he stood for – intensified. In common with many artists, writers and musicians of the era Stevenson’s behaviour and interests were thought to be dangerously Bohemian, and in his case led to a scandalous outcome: he fell in love with Fanny Van De Grift Osbourne. Fanny rendered four terrible sins for the young Scot, any one of which would have secured his social damnation: she was American, married, had borne two children, and was 10 years his senior. However, determined to follow his own path in life, eventually he travelled, at great cost to his health, to San Francisco, in 1880 and shortly after, married the then divorced Fanny Osbourne.

Work, Writings and Themes

The lifelong tension with his father provided much for Stevenson to explore in his writing, extending beyond the natural rebellion of youth, to deeper examinations of the conflict between the past and the present, and the superficiality of society undermined by the inherent ugliness of humankind.

Stevenson’s single-minded dislike of authoritarianism provided the background to much of his writing. As with many late Victorian writers, from Arthur Machen to Oscar Wilde, the mood of hedonism and liberalism – the mode of the literate avant garde – had become attractive to those exposed to the diverse ideas of others. Stevenson’s poor health released him to think, create and write in a way that might otherwise have been denied. (This experience would be echoed only a few decades later by H.P. Lovecraft.)

Although a monumental letter writer and poet (A Child’s Garden of Verses in 1885), he is best known for his series of successful novels and short stories, Treasure Island (1883), Kidnapped (1886), Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and The Master of Ballantrae (1889). As was the tradition in the Victorian era Stevenson’s early work was initially serialized in magazines (as, of course, was that of Dickens, H.G. Wells and many others), building his readership and tuning his methods: in 1881 Treasure Island was serialized before publication as a book and allowed Stevenson to forge one of his key techniques, of page-turning suspense: ‘No need for psychology or fine writing’ he would later say.

Hypocrisy and Duality

Cover of Scribner’s original 1886 edition.

The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde is an altogether darker story than most of his other novels, but an adventure springing from everyday life, it dwells on many of the same themes. Based on a story about the double life of Deacon William Brodie – cabinet maker by day, but dissolute and thief by night – it scrutinizes puritanism, secrecy and hypocrisy, hinting at dark affronts to the public consciousness of proud Victorians, suggesting murder and egregious sexual acts, which some modern critics imbue with undercurrents of homosexuality; Oscar Wilde’s fate only a few years after Stevenson’s death show the perils of this latter imputation in the Victorian age.

Stevenson was preoccupied with duality, the twin forces that wrestle for the mind and fortune of humankind, as he said in his posthumously published letter to his cousin Bob Stevenson: ‘the prim, obliterated polite face of life, and the broad, bawdy and orgiastic’. Even Kidnapped uncoils alternative, dark futures for us, if we fall unexpectedly from our comfortable lives, into a grim world that runs in parallel to our own.

It’s worth remembering that Edinburgh, the city of Stevenson’s birth, exemplified these twin forces: the ambitious, striving energies of empire, underneath which lurked the secret city of despair and criminality, with its dark corridors and passages, hidden worlds beneath the bridges, the undulating streets with rooms carved into arches that reeked of poverty and disease. The grand streets above sought to flatten the landscape for their carriages and parties, with the great bridges of the industrial revolution, the pride of Scottish engineering. Stevenson, son of a celebrated civil engineer, seemed naturally attuned to, and repulsed by, this contrast.

Cultural Landscape

Often regarded as a children’s writer, this highlights a significant misunderstanding of the literature of the Victorian period. This was the era of gothic exhortation, of intense recountings of grim fairy tales, full of bile and vitriol, the age of vivid storytelling. While the striving middle classes read great literature to their children, education had begun to snake its way through the working classes; the British Empire, with the Scots at its core, paraded itself as a moral and educating force to the world, exporting great industrial achievements in the form of the railway, the telegraph, and the mighty civil engineering projects – the ships, aqueducts and bridges.

But it was also the era of Jack the Ripper, of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, springing from the unearthly flesh of Frankenstein, the era of accelerated scientific progress, as the trading prowess of the Victorian Era brought new ideas from around the world, in art, religion, science and philosophy, so that the question of an individual’s place in the headlong charge of advancement lay suppressed, and unexamined. But the gothic literature, from Dickens’ Bleak House to Oscar Wilde’s tale of excess and greed, The Portrait of Dorian Gray, explored the tension at the heart of Empire, of the conflict between the beast and the man within.

Mary Shelley’s masterpiece Frankenstein had raised questions about superficiality, the role of humankind in creating the world around it, of responsibility and desire, but in Stevenson’s Jekyll was an everyday protagonist. A doctor by day, he was someone who could be understood by all of his readers, someone they, and we still, could all meet. Stevenson reveals the beast within, insinuating the fear of the civilized man, that the inner neanderthal might rise and overcome this new found sophistication, and drag down the advancement of science and nationhood.

Stevenson has been much criticised for his taste for the fantastic. His short novels, his racy plots, his emphasis on storytelling rather than the reflection of a supposed real life was out of step with the elite literary mood of the late Victorian, and early twentieth century. Indeed the writers who could share his inclinations were relatively unknown to him: Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, H.P. Lovecraft, unaware – as is often the case – that he was writing in an emerging tradition.

Connections, Legacy and Later Years

Stevenson admired the economy of Henry James and Guy de Maupassant, reveled in the forboding gloom of Edgar Allan Poe, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s critique of religion and the dark moments of the soul. He was widely read, and respected for the eloquence of his writing by many fellow writers: he corresponded with J.M. Barrie, Arthur Conan Doyle and Thomas Hardy, and was lauded by Edith Wharton, and later by Jorge Luis Borges, Graham Greene, and John Buchan who brought Stevenson’s page-turning adventures into the middle of the twentieth century, bridging the gap between the great nineteenth century novel and the shorter, more fragmented forms of modernism.

Stevenson’s place is secure in the Gothic Tradition but his impact was wider, both during his life and after. His last 14 years, spent with his wife Fanny, were marked by ill health, bed rest and travel, but he wrote his most celebrated books during that period. He became a celebrated, successful writer and finished his years in the Islands of Samoa, his life extinguished by a heart attack, at the relatively young age of 46.

Stevenson’s place is secure in the Gothic Tradition but his impact was wider, both during his life and after. His last 14 years, spent with his wife Fanny, were marked by ill health, bed rest and travel, but he wrote his most celebrated books during that period. He became a celebrated, successful writer and finished his years in the Islands of Samoa, his life extinguished by a heart attack, at the relatively young age of 46.

This text appears as the Life and Works biography in the Flame Tree Publishing 2015 edition of The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde. Available here.

Links

Other posts of interest in These Fantastic Worlds include:

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

Henry Fuseli: Dark Gothic Fantasy

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF Classics

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

Frankenstein by Jeffrey Catherine Jones

H.P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

The post Robert Louis Stevenson: Master of Victorian Gothic appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.