Jake Jackson's Blog, page 17

January 27, 2016

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (1850–94) was born in a da...

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (1850–94) was born in a dank and cold Edinburgh, but travelled greatly in search of less brutal weather, finally to pass away in the temperate climes of Samoa. For today’s reader his reputation as a writer of adventure fiction is well established but as a poet, essayist, travel writer and masterful short story writer his range was great and varied. In his time, he was a popular author and associated with many of the most notable writers of the late Victorian period, although the elitism of some contemporary literary critics sought to bury him with the Romantics until his reputation was rescued in the twentieth century, as a skillful storyteller of the gothic and fantastic.

Early Years

Born to respectable parents at the height of the British Empire, Stevenson’s ill health led him to spend much of his time reading, or being read to, frequently unable to join his peers at school. His grandfather was Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University, his father a civil engineer of over 40 prestigious lighthouses, so there were great expectations for the young Stevenson. However his mind was saturated by the works of Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, John Bunyan, The Arabian Nights and the elaborate, moralising fairy tales of Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. His early instincts for storytelling were clear, in spite of the best attempts of his family who expected him to pursue a career in science.

Initially he consented to the study of engineering at the University of Edinbugh from 1867, but soon found the pull of literature to be too seductive. His parents were horrified at the prospect of their son relying on the unstable, and distasteful, pursuit of writing as career, so collectively they managed a compromise: Stevenson would study law instead. He was called to the bar in 1875, although never practised.

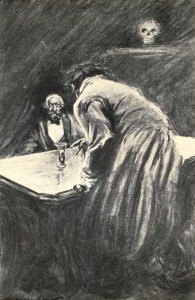

Illustration by Charles Raymond Macauley for the 1904 edition of The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Published by Scott-Thaw

As he grew into adulthood Stevenson’s conflicts with his parents – his father in particular, and all he stood for – intensified. In common with many artists, writers and musicians of the era Stevenson’s behaviour and interests were thought to be dangerously Bohemian, and in his case led to a scandalous outcome: he fell in love with Fanny Van De Grift Osbourne. Fanny rendered four terrible sins for the young Scot, any one of which would have secured his social damnation: she was American, married, had borne two children, and was 10 years his senior. However, determined to follow his own path in life, eventually he travelled, at great cost to his health, to San Francisco, in 1880 and shortly after, married the then divorced Fanny Osbourne.

Work, Writings and Themes

The lifelong tension with his father provided much for Stevenson to explore in his writing, extending beyond the natural rebellion of youth, to deeper examinations of the conflict between the past and the present, and the superficiality of society undermined by the inherent ugliness of humankind.

Stevenson’s single-minded dislike of authoritarianism provided the background to much of his writing. As with many late Victorian writers, from Arthur Machen to Oscar Wilde, the mood of hedonism and liberalism – the mode of the literate avant garde – had become attractive to those exposed to the diverse ideas of others. Stevenson’s poor health released him to think, create and write in a way that might otherwise have been denied. (This experience would be echoed only a few decades later by H.P. Lovecraft.)

Although a monumental letter writer and poet (A Child’s Garden of Verses in 1885), he is best known for his series of successful novels and short stories, Treasure Island (1883), Kidnapped (1886), Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and The Master of Ballantrae (1889). As was the tradition in the Victorian era Stevenson’s early work was initially serialized in magazines (as, of course, was that of Dickens, H.G. Wells and many others), building his readership and tuning his methods: in 1881 Treasure Island was serialized before publication as a book and allowed Stevenson to forge one of his key techniques, of page-turning suspense: ‘No need for psychology or fine writing’ he would later say.

Hypocrisy and Duality

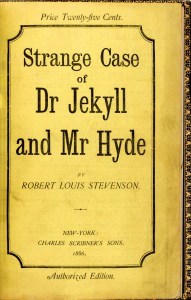

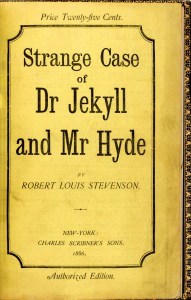

Cover of Scribner’s original 1886 edition.

The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde is an altogether darker story than most of his other novels, but an adventure springing from everyday life, it dwells on many of the same themes. Based on a story about the double life of Deacon William Brodie – cabinet maker by day, but dissolute and thief by night – it scrutinizes puritanism, secrecy and hypocrisy, hinting at dark affronts to the public consciousness of proud Victorians, suggesting murder and egregious sexual acts, which some modern critics imbue with undercurrents of homosexuality; Oscar Wilde’s fate only a few years after Stevenson’s death show the perils of this latter imputation in the Victorian age.

Stevenson was preoccupied with duality, the twin forces that wrestle for the mind and fortune of humankind, as he said in his posthumously published letter to his cousin Bob Stevenson: ‘the prim, obliterated polite face of life, and the broad, bawdy and orgiastic’. Even Kidnapped uncoils alternative, dark futures for us, if we fall unexpectedly from our comfortable lives, into a grim world that runs in parallel to our own.

It’s worth remembering that Edinburgh, the city of Stevenson’s birth, exemplified these twin forces: the ambitious, striving energies of empire, underneath which lurked the secret city of despair and criminality, with its dark corridors and passages, hidden worlds beneath the bridges, the undulating streets with rooms carved into arches that reeked of poverty and disease. The grand streets above sought to flatten the landscape for their carriages and parties, with the great bridges of the industrial revolution, the pride of Scottish engineering. Stevenson, son of a celebrated civil engineer, seemed naturally attuned to, and repulsed by, this contrast.

Cultural Landscape

Often regarded as a children’s writer, this highlights a significant misunderstanding of the literature of the Victorian period. This was the era of gothic exhortation, of intense recountings of grim fairy tales, full of bile and vitriol, the age of vivid storytelling. While the striving middle classes read great literature to their children, education had begun to snake its way through the working classes; the British Empire, with the Scots at its core, paraded itself as a moral and educating force to the world, exporting great industrial achievements in the form of the railway, the telegraph, and the mighty civil engineering projects – the ships, aqueducts and bridges.

But it was also the era of Jack the Ripper, of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, springing from the unearthly flesh of Frankenstein, the era of accelerated scientific progress, as the trading prowess of the Victorian Era brought new ideas from around the world, in art, religion, science and philosophy, so that the question of an individual’s place in the headlong charge of advancement lay suppressed, and unexamined. But the gothic literature, from Dickens’ Bleak House to Oscar Wilde’s tale of excess and greed, The Portrait of Dorian Gray, explored the tension at the heart of Empire, of the conflict between the beast and the man within.

Mary Shelley’s masterpiece Frankenstein had raised questions about superficiality, the role of humankind in creating the world around it, of responsibility and desire, but in Stevenson’s Jekyll was an everyday protagonist. A doctor by day, he was someone who could be understood by all of his readers, someone they, and we still, could all meet. Stevenson reveals the beast within, insinuating the fear of the civilized man, that the inner neanderthal might rise and overcome this new found sophistication, and drag down the advancement of science and nationhood.

Stevenson has been much criticised for his taste for the fantastic. His short novels, his racy plots, his emphasis on storytelling rather than the reflection of a supposed real life was out of step with the elite literary mood of the late Victorian, and early twentieth century. Indeed the writers who could share his inclinations were relatively unknown to him: Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, H.P. Lovecraft, unaware – as is often the case – that he was writing in an emerging tradition.

Connections, Legacy and Later Years

Stevenson admired the economy of Henry James and Guy de Maupassant, reveled in the forboding gloom of Edgar Allan Poe, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s critique of religion and the dark moments of the soul. He was widely read, and respected for the eloquence of his writing by many fellow writers: he corresponded with J.M. Barrie, Arthur Conan Doyle and Thomas Hardy, and was lauded by Edith Wharton, and later by Jorge Luis Borges, Graham Greene, and John Buchan who brought Stevenson’s page-turning adventures into the middle of the twentieth century, bridging the gap between the great nineteenth century novel and the shorter, more fragmented forms of modernism.

Stevenson’s place is secure in the Gothic Tradition but his impact was wider, both during his life and after. His last 14 years, spent with his wife Fanny, were marked by ill health, bed rest and travel, but he wrote his most celebrated books during that period. He became a celebrated, successful writer and finished his years in the Islands of Samoa, his life extinguished by a heart attack, at the relatively young age of 46.

Stevenson’s place is secure in the Gothic Tradition but his impact was wider, both during his life and after. His last 14 years, spent with his wife Fanny, were marked by ill health, bed rest and travel, but he wrote his most celebrated books during that period. He became a celebrated, successful writer and finished his years in the Islands of Samoa, his life extinguished by a heart attack, at the relatively young age of 46.

This text appears as the Life and Works biography in the Flame Tree Publishing 2015 edition of The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde. Available here.

Links

Other posts of interest in These Fantastic Worlds include:

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

Henry Fuseli: Dark Gothic Fantasy

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF Classics

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

Frankenstein by Jeffrey Catherine Jones

H.P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

The post Robert Louis Stevenson: Master of Victorian Gothic appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (1850–94) was born in oft ...

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (1850–94) was born in oft dank and cold Edinburgh, but travelled greatly in search of less brutal weather, finally to pass away in the temperate climes of Samoa. For today’s reader his reputation as a writer of adventure fiction is well established but as a poet, essayist, travel writer and masterful short story writer his range was great and varied. In his time, he was a popular author and associated with many of the most notable writers of the late Victorian period, although the elitism of some contemporary literary critics sought to bury him with the Romantics until his reputation was rescued in the twentieth century, as a skillful storyteller of the gothic and fantastic.

Early Years

Born to respectable parents at the height of the British Empire, Stevenson’s ill health led him to spend much of his time reading, or being read to, frequently unable to join his peers at school. His grandfather was Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University, his father a civil engineer of over 40 prestigious lighthouses, so there were great expectations for the young Stevenson. However his mind was saturated by the works of Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, John Bunyan, The Arabian Nights and the elaborate, moralising fairy tales of Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. His early instincts for storytelling were clear, in spite of the best attempts of his family who expected him to pursue a career in science.

Initially he consented to the study of engineering at the University of Edinbugh from 1867, but soon found the pull of literature to be too seductive. His parents were horrified at the prospect of their son relying on the unstable, and distasteful, pursuit of writing as career, so collectively they managed a compromise: Stevenson would study law instead. He was called to the bar in 1875, although never practised.

Illustration by Charles Raymond Macauley for the 1904 edition of The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Published by Scott-Thaw

As he grew into adulthood Stevenson’s conflicts with his parents – his father in particular, and all he stood for – intensified. In common with many artists, writers and musicians of the era Stevenson’s behaviour and interests were thought to be dangerously Bohemian, and in his case led to a scandalous outcome: he fell in love with Fanny Van De Grift Osbourne. Fanny rendered four terrible sins for the young Scot, any one of which would have secured his social damnation: she was American, married, had borne two children, and was 10 years his senior. However, determined to follow his own path in life, eventually he travelled, at great cost to his health, to San Francisco, in 1880 and shortly after, married the then divorced Fanny Osbourne.

Work, Writings and Themes

The lifelong tension with his father provided much for Stevenson to explore in his writing, extending beyond the natural rebellion of youth, to deeper examinations of the conflict between the past and the present, and the superficiality of society undermined by the inherent ugliness of humankind.

Stevenson’s single-minded dislike of authoritarianism provided the background to much of his writing. As with many late Victorian writers, from Arthur Machen to Oscar Wilde, the mood of hedonism and liberalism – the mode of the literate avant garde – had become attractive to those exposed to the diverse ideas of others. Stevenson’s poor health released him to think, create and write in a way that might otherwise have been denied. (This experience would be echoed only a few decades later by H.P. Lovecraft.)

Although a monumental letter writer and poet (A Child’s Garden of Verses in 1885), he is best known for his series of successful novels and short stories, Treasure Island (1883), Kidnapped (1886), Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and The Master of Ballantrae (1889). As was the tradition in the Victorian era Stevenson’s early work was initially serialized in magazines (as, of course, was that of Dickens, H.G. Wells and many others), building his readership and tuning his methods: in 1881 Treasure Island was serialized before publication as a book and allowed Stevenson to forge one of his key techniques, of page-turning suspense: ‘No need for psychology or fine writing’ he would later say.

Hypocrisy and Duality

Cover of Scribner’s original 1886 edition.

The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde is an altogether darker story than most of his other novels, but an adventure springing from everyday life, it dwells on many of the same themes. Based on a story about the double life of Deacon William Brodie – cabinet maker by day, but dissolute and thief by night – it scrutinizes puritanism, secrecy and hypocrisy, hinting at dark affronts to the public consciousness of proud Victorians, suggesting murder and egregious sexual acts, which some modern critics imbue with undercurrents of homosexuality; Oscar Wilde’s fate only a few years after Stevenson’s death show the perils of this latter imputation in the Victorian age.

Stevenson was preoccupied with duality, the twin forces that wrestle for the mind and fortune of humankind, as he said in his posthumously published letter to his cousin Bob Stevenson: ‘the prim, obliterated polite face of life, and the broad, bawdy and orgiastic’. Even Kidnapped uncoils alternative, dark futures for us, if we fall unexpectedly from our comfortable lives, into a grim world that runs in parallel to our own.

It’s worth remembering that Edinburgh, the city of Stevenson’s birth, exemplified these twin forces: the ambitious, striving energies of empire, underneath which lurked the secret city of despair and criminality, with its dark corridors and passages, hidden worlds beneath the bridges, the undulating streets with rooms carved into arches that reeked of poverty and disease. The grand streets above sought to flatten the landscape for their carriages and parties, with the great bridges of the industrial revolution, the pride of Scottish engineering. Stevenson, son of a celebrated civil engineer, seemed naturally attuned to, and repulsed by, this contrast.

Cultural Landscape

Often regarded as a children’s writer, this highlights a significant misunderstanding of the literature of the Victorian period. This was the era of gothic exhortation, of intense recountings of grim fairy tales, full of bile and vitriol, the age of vivid storytelling. While the striving middle classes read great literature to their children, education had begun to snake its way through the working classes; the British Empire, with the Scots at its core, paraded itself as a moral and educating force to the world, exporting great industrial achievements in the form of the railway, the telegraph, and the mighty civil engineering projects – the ships, aqueducts and bridges.

But it was also the era of Jack the Ripper, of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, springing from the unearthly flesh of Frankenstein, the era of accelerated scientific progress, as the trading prowess of the Victorian Era brought new ideas from around the world, in art, religion, science and philosophy, so that the question of an individual’s place in the headlong charge of advancement lay suppressed, and unexamined. But the gothic literature, from Dickens’ Bleak House to Oscar Wilde’s tale of excess and greed, The Portrait of Dorian Gray, explored the tension at the heart of Empire, of the conflict between the beast and the man within.

Mary Shelley’s masterpiece Frankenstein had raised questions about superficiality, the role of humankind in creating the world around it, of responsibility and desire, but in Stevenson’s Jekyll was an everyday protagonist. A doctor by day, he was someone who could be understood by all of his readers, someone they, and we still, could all meet. Stevenson reveals the beast within, insinuating the fear of the civilized man, that the inner neanderthal might rise and overcome this new found sophistication, and drag down the advancement of science and nationhood.

Stevenson has been much criticised for his taste for the fantastic. His short novels, his racy plots, his emphasis on storytelling rather than the reflection of a supposed real life was out of step with the elite literary mood of the late Victorian, and early twentieth century. Indeed the writers who could share his inclinations were relatively unknown to him: Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, H.P. Lovecraft, unaware – as is often the case – that he was writing in an emerging tradition.

Connections, Legacy and Later Years

Stevenson admired the economy of Henry James and Guy de Maupassant, reveled in the forboding gloom of Edgar Allan Poe, and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s critique of religion and the dark moments of the soul. He was widely read, and respected for the eloquence of his writing by many fellow writers: he corresponded with J.M. Barrie, Arthur Conan Doyle and Thomas Hardy, and was lauded by Edith Wharton, and later by Jorge Luis Borges, Graham Greene, and John Buchan who brought Stevenson’s page-turning adventures into the middle of the twentieth century, bridging the gap between the great nineteenth century novel and the shorter, more fragmented forms of modernism.

Stevenson’s place is secure in the Gothic Tradition but his impact was wider, both during his life and after. His last 14 years, spent with his wife Fanny, were marked by ill health, bed rest and travel, but he wrote his most celebrated books during that period. He became a celebrated, successful writer and finished his years in the Islands of Samoa, his life extinguished by a heart attack, at the relatively young age of 46.

Stevenson’s place is secure in the Gothic Tradition but his impact was wider, both during his life and after. His last 14 years, spent with his wife Fanny, were marked by ill health, bed rest and travel, but he wrote his most celebrated books during that period. He became a celebrated, successful writer and finished his years in the Islands of Samoa, his life extinguished by a heart attack, at the relatively young age of 46.

This text appears as the Life and works biography in the Flame Tree Publishing 2015 edition of The Strange Case of Jekyll and Hyde. Available here.

Links

Other posts of interest in These Fantastic Worlds include:

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

Henry Fuseli: Dark Gothic Fantasy

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF Classics

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

Frankenstein by Jeffrey Catherine Jones

H.P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

The post Robert Louis Stevenson: Master of Victorian Gothic appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

January 20, 2016

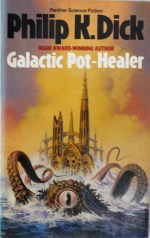

100 SF & Fantasy Books. Galactic Pot-Healer. Philip K. Dick.

Philip K. Dick. Just his name conjures excitement and imagination. There are so many books and short stories to choose from his extensive, brilliant output, but this The Galactic Pot-Healer is the one I remember with great fondness from a particularly creative period in my life when I painted, wrote, played in my first bands, and earned enough money to feed a reading habit frowned upon by my parents: Philip K. Dick, Poul Anderson, John Brunner, Ray Bradbury and so many more jostled for space on the walls, shelves and surfaces of my small apartment.

Philip K. Dick. Just his name conjures excitement and imagination. There are so many books and short stories to choose from his extensive, brilliant output, but this The Galactic Pot-Healer is the one I remember with great fondness from a particularly creative period in my life when I painted, wrote, played in my first bands, and earned enough money to feed a reading habit frowned upon by my parents: Philip K. Dick, Poul Anderson, John Brunner, Ray Bradbury and so many more jostled for space on the walls, shelves and surfaces of my small apartment.

Books to Movies

Many of Dick’s stories have made a successful transition into film. With strong storytelling and powerfully focused ideas, Dick managed to slalom through politics, society and religion. His deft touch has left us with Total Recall (based on We Can Remember it for you Wholesale), A Scanner Darkly (of the same name), The Adjustment Bureau (The Adjustment Team), Minority Report (same name), and a candidate for any list of top SF, Blade Runner (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep). These, and other great movies, glitter so brightly it’s easy to forget his other great tales, so I’ve kept with this one, which hasn’t yet made it onto the silver screen.

Galactic Visions

Like many good sf stories The Galactic Pot-Healer starts in some mundane dystopic cityscape (reminding me at the time of Terry Gilliam’s uniquely inventive Brazil), the main character struggling in a tedious life, entertaining himself with amusing mistranslations (curiously foreshadowing Google Translator) before being tempted by an apparently infallible God. It’s a mad mission to another planet, an impossible task to raise an ancient cathedral from the beneath the seas. Who wouldn’t want to?

There’s plenty of fun to be exercised at the expense of all forms of religion, the inanity of humankind, men in particular, and the inevitable jousting with fate. Still a great read today.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 SF & Fantasy Books. Galactic Pot-Healer. Philip K. Dick. appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Philip K. Dick. Just his name conjures excitement and ima...

Philip K. Dick. Just his name conjures excitement and imagination. There are so many books and short stories to choose from his extensive, brilliant output, but this The Galactic Pot-Healer is the one I remember with great fondness from a particularly creative period in my life when I painted, wrote, played in my first bands, and earned enough money to feed a reading habit frowned upon by my parents: Philip K. Dick, Poul Anderson, John Brunner, Ray Bradbury and so many more jostled for space on the walls, shelves and surfaces of my small apartment.

Philip K. Dick. Just his name conjures excitement and imagination. There are so many books and short stories to choose from his extensive, brilliant output, but this The Galactic Pot-Healer is the one I remember with great fondness from a particularly creative period in my life when I painted, wrote, played in my first bands, and earned enough money to feed a reading habit frowned upon by my parents: Philip K. Dick, Poul Anderson, John Brunner, Ray Bradbury and so many more jostled for space on the walls, shelves and surfaces of my small apartment.

Books to Movies

Many of Dick’s stories have made a successful transition into film. With strong storytelling and powerfully focused ideas, Dick managed to slalom through politics, society and religion. His deft touch has left us with Total Recall (based on We Can Remember it for you Wholesale), A Scanner Darkly (of the same name), The Adjustment Bureau (The Adjustment Team), Minority Report (same name), and a candidate for any list of top SF, Blade Runner (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep). These, and other great movies, glitter so brightly it’s easy to forget his other great tales, so I’ve kept with this one, which hasn’t yet made it onto the silver screen.

Galactic Visions

Like many good sf stories The Galactic Pot-Healer starts in some mundane dystopic cityscape (reminding me at the time of Terry Gilliam’s uniquely inventive Brazil), the main character struggling in a tedious life, entertaining himself with amusing mistranslations (curiously foreshadowing Google Translator) before being tempted by an apparently infallible God. It’s a mad mission to another planet, an impossible task to raise an ancient cathedral from the beneath the seas. Who wouldn’t want to?

There’s plenty of fun to be exercised at the expense of all forms of religion, the inanity of humankind, men in particular, and the inevitable jousting with fate. Still a great read today.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 SF & Fantasy Books. Galactic Pot-Healer. Philip K. Dick. appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

January 13, 2016

Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books. Rebel Worlds. Poul Anderson.

Poul Anderson is a seriously under-rated sf writer. If you want aliens, spaceships, intergalactic adventures, then he’s your man. He wrote a great deal of fantasy (including a pretty decent Conan the Rebel story in 1980), having been born in 1926 just as the Golden Age of pulp magazines began to influence a generations of school kids. He wrote dozens of enthralling short stories, novels and novellas, was wreathed in awards (7 Hugos, 3 Nebulas, 4 Prometheus) and honoured by his peers as a friend and influence: Heinlein, Bradbury, Campbell and many others.

Poul Anderson is a seriously under-rated sf writer. If you want aliens, spaceships, intergalactic adventures, then he’s your man. He wrote a great deal of fantasy (including a pretty decent Conan the Rebel story in 1980), having been born in 1926 just as the Golden Age of pulp magazines began to influence a generations of school kids. He wrote dozens of enthralling short stories, novels and novellas, was wreathed in awards (7 Hugos, 3 Nebulas, 4 Prometheus) and honoured by his peers as a friend and influence: Heinlein, Bradbury, Campbell and many others.

And yet, where are the movies? The re-issues? the TV shows based in his stories? It’s true, he doesn’t have the light, inventive touch of a Philip K. Dick’s or Bradbury’s gravid profundity but as a weaver of worlds, his work is intriguing and his tales move swiftly forward. For the modern taste, perhaps his work sits too squarely in the institutional, conservative-with-a-small-c sf of the 1950s, and the plot-lines are a little complex for the unravelling of a movie, but they’re a damn good read.

The Mysterious Mr Anderson

As an impressionable young sf and fantasy enthusiast I remember asking my local SF store for any of his work, only to be told, unforgivably, that he was just a figment of Robert Heinlein’s imagination. I still remember finding this particular book, a couple of years later, on a visit to Foyles in London. Embarrassingly I yelped and laughed simultaneously (I’m English, these things don’t come so easily, especially in public), so it remains one of my own favourite finds.

The Rebel Worlds is the third in Anderson’s Michael Flandry series, focusing on the Terran empire, and it offers Anderson’s usual mix of physics flavoured fantasy, romance and colonial conflict, all tightly rolled into spy-thrilling page turner. It’s probably the best of the series because it offers more emotional detail in the adversarial heroes, Flandry and Admiral McCormac, but I can also detect elements of Han Solo here too. Perhaps George Lucas was a fan too! Thoroughly recommended.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Top 100 SF & F Books. American Gods.

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books. Rebel Worlds. Poul Anderson. appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Poul Anderson is a seriously under-rated sf writer. If yo...

Poul Anderson is a seriously under-rated sf writer. If you want aliens, spaceships, intergalactic adventures, then he’s your man. He wrote a great deal of fantasy (including a pretty decent Conan the Rebel story in 1980), having been born in 1926 just as the Golden Age of pulp magazines began to influence a generations of school kids. He wrote dozens of enthralling short stories, novels and novellas, was wreathed in awards (7 Hugos, 3 Nebulas, 4 Prometheus) and honoured by his peers as a friend and influence: Heinlein, Bradbury, Campbell and many others.

Poul Anderson is a seriously under-rated sf writer. If you want aliens, spaceships, intergalactic adventures, then he’s your man. He wrote a great deal of fantasy (including a pretty decent Conan the Rebel story in 1980), having been born in 1926 just as the Golden Age of pulp magazines began to influence a generations of school kids. He wrote dozens of enthralling short stories, novels and novellas, was wreathed in awards (7 Hugos, 3 Nebulas, 4 Prometheus) and honoured by his peers as a friend and influence: Heinlein, Bradbury, Campbell and many others.

And yet, where are the movies? The re-issues? the TV shows based in his stories? It’s true, he doesn’t have the light, inventive touch of a Philip K. Dick’s or Bradbury’s gravid profundity but as a weaver of worlds, his work is intriguing and his tales move swiftly forward. For the modern taste, perhaps his work sits too squarely in the institutional, conservative-with-a-small-c sf of the 1950s, and the plotlines are a little complex for the unravelling of a movie, but they’re a damn good read.

The Mysterious Mr Anderson

As an impressionable young sf and fantasy enthusiast I remember asking my local SF store for any of his work, only to be told, unforgivably, that he was just a figment of Robert Heinlein’s imagination. I still remember finding this particular book, a couple of years later, on a visit to Foyles in London. Embarrassingly I yelped and laughed simultaneously (I’m English, these things don’t come so easily, especially in public), so it remains one of my own favourite finds.

The Rebel Worlds is the third in Anderson’s Michael Flandry series, focusing on the Terran empire, and it offers Anderson’s usual mix of physics flavoured fantasy, romance and colonial conflict, all tightly rolled into spy-thrilling page turner. It’s probably the best of the series because it offers more emotional detail in the adversarial heroes, Flandry and Admiral McCormac, but I can also detect elements of Han Solo here too. Perhaps George Lucas was a fan too! Thoroughly recommended.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post 100 Top SF & Fantasy Books. Rebel Worlds. Poul Anderson. appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

January 6, 2016

Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books. American Gods. Neil Gaiman

Gaiman’s American Gods is a modern wonder of the world. Somehow it manages to straddle the chaos of the everyday, with the power and mystery of the ancients, stirring the gods of America’s various constituent populations, with the all-powerful, glittering, idols of today. A modern moral story it’s a beast of a ride, and one of my absolute favourite books.

Gaiman’s American Gods is a modern wonder of the world. Somehow it manages to straddle the chaos of the everyday, with the power and mystery of the ancients, stirring the gods of America’s various constituent populations, with the all-powerful, glittering, idols of today. A modern moral story it’s a beast of a ride, and one of my absolute favourite books.

Published in 2001, I think I read it sometime that year or so, but I knew Gaiman more as a comic writer, Blue Orchid and Sandman mainly, where he achieved the rare balance of delivering a cracking good read, with something to say about the world we live in, in a format which, when I was young, was much derided. His work is always on the edge, without being pretentious, and he plays with multiple concepts so deftly its impossible not to be entranced by the intricacy of it all.

Gaiman: Ancient and Modern

Gaiman’s storytelling prowess is front and centre in American Gods, it races along, building myths and mini marvels, as the main character Shadow encounters the crumbling remains of once-mighty deities, their lustre diminished, destroyed even by the new Gods of the modern world: commerce, media, superficiality. The story is a road trip through the gritty, grungy landscape of the everyday, with carousels, and drunkards tumbling into a celebration of America’s combustable mix of immigrants, from the original native american tribes, to the Viking settlements of the 1100s and the many European traditions that surged into the new territories from the 1600s. This huge continent played host to the pagan gods of so many peoples, allowing Gaiman a vast playground of wonder.

The terrible power of the old Gods, from manifestions of the all-father Odin (who appears as Mr Wednesday, and brings visions of the gallows) to Anubis (Egyptian), Anansi (African) and Kali (Hindu), and Whisky Jack (a Loki-like figure from native American lore), surges through the subterranea of the narrative, emerging and sinking in the shifting dreams of reality. This is a battle for the soul of America, offering an intriguing view of the search for a cohesive American mythology that matches the power of its economic, entrepreneurial might. I loved it on first read, and every one since. Easily in the top 10, probably top 5 of the 100 SF and Fantasy Books of all time.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Top 100 SF & F Books. The Rebel Worlds (Poul Anderson)

Top 100 SF & F Books. American Gods.

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF classics

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books. American Gods. Neil Gaiman appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Gaiman’s American Gods is a modern wonder of the world. S...

Gaiman’s American Gods is a modern wonder of the world. Somehow it manages to straddle the chaos of the everyday, with the power and mystery of the ancients, stirring the gods of America’s various constituent populations, with the all-powerful, glittering, idols of today. A modern moral story it’s a beast of a ride, and one of my absolute favourite books.

Gaiman’s American Gods is a modern wonder of the world. Somehow it manages to straddle the chaos of the everyday, with the power and mystery of the ancients, stirring the gods of America’s various constituent populations, with the all-powerful, glittering, idols of today. A modern moral story it’s a beast of a ride, and one of my absolute favourite books.

Published in 2001, I think I read it sometime that year or so, but I knew Gaiman more as a comic writer, Blue Orchid and Sandman mainly, where he achieved the rare balance of delivering a cracking good read, with something to say about the world we live in, in a format which, when I was young, was much derided. His work is always on the edge, without being pretentious, and he plays with multiple concepts so deftly its impossible not to be entranced by the intricacy of it all.

Gaiman: Ancient and Modern

Gaiman’s storytelling prowess is front and centre in American Gods, it races along, building myths and mini marvels, as the main character Shadow encounters the crumbling remains of once-mighty deities, their lustre diminished, destroyed even by thenew Gods of the modern world: commerce, media, superficiality. The story is a road trip through the gritty, grungy landscape of the everyday, with carousels, and drunkards tumbling into a celebration of America’s combustable mix of immigrants, from the original native american tribes, to the Viking settlements of the 1100s and the many European traditions that surged into the new territories from the 1600s. This huge continent played host to the pagan gods of so many peoples, allowing Gaiman a vast playground of wonder.

The terrible power of the old Gods, from manifestions of the all-father Odin (who appears as Mr Wednesday, and brings visions of the gallows) to Anubis (Egyptian), Anansi (African) and Kali (Hindu), and Whisky Jack (a Loki-like figure from native American lore), surges through the subterranea of the narrative, emerging and sinking in the shifting dreams of reality. This is a battle for the soul of America, offering an intriguing view of the search for a cohesive American mythology that matches the power of its economic, entrepreneurial might. I loved it on first read, and every one since. Easily in the top 10, probably top 5 of the 100 SF and Fantasy Books of all time.

Links

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land.

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF classics

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books. American Gods. Neil Gaiman appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

December 23, 2015

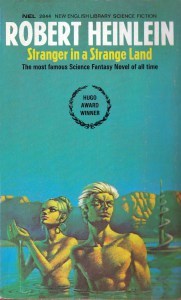

Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land. Robert Heinlein

Originally published on the lip of the 1960s Heinlein’s most popular book exists at that dangerous point in history where the patrician attitudes of the ’50s status quo collided with the rebellious freedoms of the ’60s.

Originally published on the lip of the 1960s Heinlein’s most popular book exists at that dangerous point in history where the patrician attitudes of the ’50s status quo collided with the rebellious freedoms of the ’60s.

Mike is the lone survivor of a human colony on Mars. Raised by Martians he returns to earth ignorant of human ways, brings free love and apparent magic to humanity, becomes the focus of a new religion and is soon martyred. As you might expect, there’s much playing with the notion of who’s the stranger and which is the stranger land?

Heinlein’s story is fascinating, teasing out almost every ‘ism’ you could imagine, along with some decidedly dodgy latent views on religion, female sexuality and male gender orientation. It’s very much a product if its time, and it’s a tough read now for any adult reader aware of the modern world around them.

Early inspiration

I first read this when I was 12. It had a big impact in me. I loved SF and consumed everything I could find, and I think I’d just finished the first Dune with its grandiose universe. Stranger in a Strange Land brought the alien to my doorstep, I understood the temptations and the excitement, I identified with the strangeness and loneliness of Mike, and I remember wandering the streets of my hometown blinking and trying to see the world as he would see it; but of course, barely a teenager I didn’t understand the implications.

So, part of me is still in its thrall. I reread it recently and cringed but clung to my younger self and made it to the end, reveling in the nostalgic moment, and managed to dismiss the wiser council of my later years.

It’s still in my top 100, somewhere in the lower regions of the top 50 perhaps because it ignited my imagination on a way that connected me to the Outer Limits TV show, and the Apollo lunar space missions that gripped us all in the late sixties and early seventies.

Links

Virgil Finlay’s depiction of other worlds is always fascinating

Robert Bloch covered sf, fantasy and horror

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books: American Gods

Top 100 SF & Fantasy Books: The Rebel Worlds (Poul Anderson)

Front cover photograph by Elise Wells, 2016

The post Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land. Robert Heinlein appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.

Originally published on the lip of the 1960s Heinlein’s m...

Originally published on the lip of the 1960s Heinlein’s most popular book exists at dangerous point in history where the attitudes if the patrician status quo of the 1950s collided with the rebellious freedoms of the 1960s.

Originally published on the lip of the 1960s Heinlein’s most popular book exists at dangerous point in history where the attitudes if the patrician status quo of the 1950s collided with the rebellious freedoms of the 1960s.

Mike the Martian is the lone survivor of a human colony on Mars. Raised by Martians he returns to earth ignorant of human ways, brings free love and apparent magic to humanity, becomes the focus of a new religion and is soon martyred. As you might expect, there’s much playing with the notion of who’s the stranger and which is the stranger land?

Heinlein’s story is fascinating, teasing out almost every ‘ism’ you could imagine, along with some decidedly dodgy latent views on religion, female sexuality and male gender orientation. It’s very much a product if its time, and it’s a tough read now for any adult reader aware of the modern world around them.

Early inspiration

I first read this when I was 12. It had a big impact in me. I loved SF and consumed everything I could find, and I think I’d just finished the first Dune with its grandiose universe. Stranger in a Strange Land brought the alien to my doorstep, I understood the temptations and the excitement, I identified with the strangeness and loneliness of Mike, and I remember wandering the streets of my hometown blinking and trying to see the world as he would see it; but of course, barely a teenager I didn’t understand the implications.

So, part of me is still in its thrall. I reread it recently and cringed but clung to my younger self and made it to the end, reveling in the nostalgic moment, and managed to dismiss the wiser council of my later years.

It’s still in my top 100, somewhere in the lower regions of the top 50 perhaps because it ignited my imagination on a way that connected me to the Outer Limits TV show, and the Apollo lunar space missions that gripped us all in the late sixties and early seventies.

Links

Virgil Finlay’s depiction of other worlds is always fascinating

Robert Bloch covered sf, fantasy and horror

H.P. Lovecraft created some incredible monsters in space and time.

The post Top 100 SF & F Books. Stranger in a Strange Land. Robert Heinlein appeared first on These Fantastic Worlds.