Jake Jackson's Blog, page 23

August 12, 2014

Authors vs Amazon vs Publishers

Yesterday I posted the email I received from Amazon trying to enlist my help (along with thousands of others) against those big nasty traditional publishers, Hachette (est. 1826).

I’m not a fan of legacy, trade publishers, they are slow, institutional and have tendency towards elitism. Now, here’s the new kid on the block, Amazon (est. 1995), having taken half the market and made themselves indispensable, negotiating hard in the only way they know how, aggressively. The battle has been dragging on for months and both sides are trying to find a way out. Amazon has been restricting pre-orders on Hachette authors, such as Robert Galbraith (J. K. Rowling‘s detective writing alter ego) and generally restricting sales of Hachette Group’s books.

Battleground

Of course this is a battle for hearts and minds, and for the money ion our pockets. Publishers such as Hachette, not the biggest of the global publishers, and ironically one of the least corporate and macho, are struggling to maintain a moral high ground. They’re a business, they have to make a bottom line to survive, they have shareholders to satisfy and they have the traditional dynamic of an old-fashioned publisher who nurtures its carefully selected authors. But in the corporate world Publishers are pussycats, with supermarket chains such as Walmart and online giants Google and Amazon, out-roaring them with ruthless aggression. Publishing retains the faint air of altruism and culture, but Amazon and the like want to change the world, and turn it to their advantage. They’re interested in readers, but only as consumers, as cash cows.

The Big Guns: Bestselling Authors

So, in step a cadre of successful authors. They’ve had enough, they want to take a stand. The big beasts of authorship, whose brands are much more significant to their readers than the publishers who fund their advances, took an ad in the New York Times this weekend, supported by 900 authors (including James Patterson and Stephen King). These are not Hachette authors, but are pledging their support to a company who they see as supporting their own world view.

So, in step a cadre of successful authors. They’ve had enough, they want to take a stand. The big beasts of authorship, whose brands are much more significant to their readers than the publishers who fund their advances, took an ad in the New York Times this weekend, supported by 900 authors (including James Patterson and Stephen King). These are not Hachette authors, but are pledging their support to a company who they see as supporting their own world view.

A Letter to Our Readers:

Amazon is involved in a commercial dispute with the book publisher Hachette , which owns Little, Brown, Grand Central Publishing, and other familiar imprints. These sorts of disputes happen all the time between companies and they are usually resolved in a corporate back room.

But in this case, Amazon has done something unusual. It has directly targeted Hachette’s authors in an effort to force their publisher to agree to its terms.

For the past several months, Amazon has been:

–Boycotting Hachette authors, by refusing to accept pre-orders on Hachette authors’ books and eBooks, claiming they are “unavailable.”

–Refusing to discount the prices of many of Hachette authors’ books.

–Slowing the delivery of thousands of Hachette authors’ books to Amazon customers, indicating that delivery will take as long as several weeks on most titles.

–Suggesting on some Hachette authors’ pages that readers might prefer a book from a non-Hachette author instead.

As writers–most of us not published by Hachette–we feel strongly that no bookseller should block the sale of books or otherwise prevent or discourage customers from ordering or receiving the books they want. It is not right for Amazon to single out a group of authors, who are not involved in the dispute, for selective retaliation. Moreover, by inconveniencing and misleading its own customers with unfair pricing and delayed delivery, Amazon is contradicting its own written promise to be “Earth’s most customer-centric company.”

Many of us have supported Amazon since it was a struggling start-up. Our books launched Amazon on the road to selling everything and becoming one of the world’s largest corporations. We have made Amazon many millions of dollars and over the years have contributed so much, free of charge, to the company by way of cooperation, joint promotions, reviews and blogs. This is no way to treat a business partner. Nor is it the right way to treat your friends. Without taking sides on the contractual dispute between Hachette and Amazon, we encourage Amazon in the strongest possible terms to stop harming the livelihood of the authors on whom it has built its business. None of us, neither readers nor authors, benefit when books are taken hostage. (We’re not alone in our plea: the opinion pages of both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, which rarely agree on anything, have roundly condemned Amazon’s corporate behavior.)

We call on Amazon to resolve its dispute with Hachette without further hurting authors and without blocking or otherwise delaying the sale of books to its customers.

We respectfully ask you, our loyal readers, to email Jeff Bezos, CEO and founder of Amazon, at jeff@amazon.com, and tell him what you think. He says he genuinely welcomes hearing from his customers and claims to read all emails at that account. We hope that, writers and readers together, we will be able to change his mind.

It’s easy to be cynical about this. Authors who can afford the 100K USD for this sort of ad, a full page in the New York Times, are bound to side with the status quo that has brought them such wealth over the years.

Authors United?

But it is a curious turn of events. It’s rare for authors to agree so publicly, they’re in competition with each other, after all, and it’s extremely unusual for authors to attempt to speak over the heads of their publisher and retailer, to address their readers directly. Perhaps they feel emboldened by the opportunities afforded by the internet, the critical need to engage with their audience, perhaps they’re doing Amazon’s work for them, proving that the traditional publishing model is no longer necessary, that authors can have direct relationships with those who buy and read their fiction, without the need of literary agents or publishers as intermediators.

Of course, self-publishers and indie publishers have realized this for a long time. The reality is that most indies sell less than a few hundred copies, but we have the freedom to publish, to make mistakes, to correct them overnight, to adjust our methods, to gain some satisfaction. Perhaps its best to let the Olympian forces fight it out above our heads? Maybe, but it does affect us, and we have to take a view.

Of course, self-publishers and indie publishers have realized this for a long time. The reality is that most indies sell less than a few hundred copies, but we have the freedom to publish, to make mistakes, to correct them overnight, to adjust our methods, to gain some satisfaction. Perhaps its best to let the Olympian forces fight it out above our heads? Maybe, but it does affect us, and we have to take a view.

It’s an interesting fight because it’s being conducted at so many levels: powerful online retailer vs entrenched publisher, publishers’ interests vs author interests, online retailer’s interests vs author interests, big author’s interests vs indie author’s interests. In the next, and final post on this subject I’ll review these core battlegrounds in more detail.

Amazon/HDP’s letter to its authors appears in the previous post.

The next post looks at the complexities and hypocrisies of the crisis.

The full list of authors appears on authorsunited.

Filed under: Fiction, Writer's Advice Tagged: amazon, Fiction, indie publishing, James Patterson, self-publishing, stephen King

August 11, 2014

Amazon vs Publishers vs Authors

So, last week I was amongst the many thousands who received a little letter from Amazon / Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP). It’s the latest and most intriguing salvo in the big war Amazon is waging both against individual corporate publishers, and the traditional publishing industry in general.

I’m registered with KDP because I have 4 books in the pipeline and will be publishing with Amazon first, then Smashwords, or Ingram to cover the rest of the market. Amazon have created a universe of opportunity for indie publishers and self-publishers to such an extent that the structure of traditional publishing has altered radically, coinciding with a global recession that’s decimated high street retail in the western economies.

Amazon vs Publishers

Amazon vs PublishersThere’s a big spat between Hachette (only the 6th largest publisher in the world) as Amazon try to radicalize their offer to their consumer, and squeeze the middle (publishers, let alone literary agents) out of the process. The fight with Hachette is only the most visible of the battles being executed by Amazon against many of their major suppliers, while they continue to improve their customer experience, shaking up the stale methods of the past.

So here’s the letter Amazon sent:

Dear KDP Author,

Just ahead of World War II, there was a radical invention that shook the foundations of book publishing. It was the paperback book. This was a time when movie tickets cost 10 or 20 cents, and books cost $2.50. The new paperback cost 25 cents – it was ten times cheaper. Readers loved the paperback and millions of copies were sold in just the first year.

With it being so inexpensive and with so many more people able to afford to buy and read books, you would think the literary establishment of the day would have celebrated the invention of the paperback, yes? Nope. Instead, they dug in and circled the wagons. They believed low cost paperbacks would destroy literary culture and harm the industry (not to mention their own bank accounts). Many bookstores refused to stock them, and the early paperback publishers had to use unconventional methods of distribution – places like newsstands and drugstores. The famous author George Orwell came out publicly and said about the new paperback format, if “publishers had any sense, they would combine against them and suppress them.” Yes, George Orwell was suggesting collusion.

Well… history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.

Fast forward to today, and it’s the e-book’s turn to be opposed by the literary establishment. Amazon and Hachette – a big US publisher and part of a $10 billion media conglomerate – are in the middle of a business dispute about e-books. We want lower e-book prices. Hachette does not. Many e-books are being released at $14.99 and even $19.99. That is unjustifiably high for an e-book. With an e-book, there’s no printing, no over-printing, no need to forecast, no returns, no lost sales due to out of stock, no warehousing costs, no transportation costs, and there is no secondary market – e-books cannot be resold as used books. E-books can and should be less expensive.

Perhaps channeling Orwell’s decades old suggestion, Hachette has already been caught illegally colluding with its competitors to raise e-book prices. So far those parties have paid $166 million in penalties and restitution. Colluding with its competitors to raise prices wasn’t only illegal, it was also highly disrespectful to Hachette’s readers.

The fact is many established incumbents in the industry have taken the position that lower e-book prices will “devalue books” and hurt “Arts and Letters.” They’re wrong. Just as paperbacks did not destroy book culture despite being ten times cheaper, neither will e-books. On the contrary, paperbacks ended up rejuvenating the book industry and making it stronger. The same will happen with e-books.

Many inside the echo-chamber of the industry often draw the box too small. They think books only compete against books. But in reality, books compete against mobile games, television, movies, Facebook, blogs, free news sites and more. If we want a healthy reading culture, we have to work hard to be sure books actually are competitive against these other media types, and a big part of that is working hard to make books less expensive.

Moreover, e-books are highly price elastic. This means that when the price goes down, customers buy much more. We’ve quantified the price elasticity of e-books from repeated measurements across many titles. For every copy an e-book would sell at $14.99, it would sell 1.74 copies if priced at $9.99. So, for example, if customers would buy 100,000 copies of a particular e-book at $14.99, then customers would buy 174,000 copies of that same e-book at $9.99. Total revenue at $14.99 would be $1,499,000. Total revenue at $9.99 is $1,738,000. The important thing to note here is that the lower price is good for all parties involved: the customer is paying 33% less and the author is getting a royalty check 16% larger and being read by an audience that’s 74% larger. The pie is simply bigger.

But when a thing has been done a certain way for a long time, resisting change can be a reflexive instinct, and the powerful interests of the status quo are hard to move. It was never in George Orwell’s interest to suppress paperback books – he was wrong about that.

And despite what some would have you believe, authors are not united on this issue. When the Authors Guild recently wrote on this, they titled their post: “Amazon-Hachette Debate Yields Diverse Opinions Among Authors” (the comments to this post are worth a read). A petition started by another group of authors and aimed at Hachette, titled “Stop Fighting Low Prices and Fair Wages,” garnered over 7,600 signatures. And there are myriad articles and posts, by authors and readers alike, supporting us in our effort to keep prices low and build a healthy reading culture. Author David Gaughran’s recent interview is another piece worth reading.

We recognize that writers reasonably want to be left out of a dispute between large companies. Some have suggested that we “just talk.” We tried that. Hachette spent three months stonewalling and only grudgingly began to even acknowledge our concerns when we took action to reduce sales of their titles in our store. Since then Amazon has made three separate offers to Hachette to take authors out of the middle. We first suggested that we (Amazon and Hachette) jointly make author royalties whole during the term of the dispute. Then we suggested that authors receive 100% of all sales of their titles until this dispute is resolved. Then we suggested that we would return to normal business operations if Amazon and Hachette’s normal share of revenue went to a literacy charity. But Hachette, and their parent company Lagardere, have quickly and repeatedly dismissed these offers even though e-books represent 1% of their revenues and they could easily agree to do so. They believe they get leverage from keeping their authors in the middle.

We will never give up our fight for reasonable e-book prices. We know making books more affordable is good for book culture. We’d like your help. Please email Hachette and copy us.

Hachette CEO, Michael Pietsch: Michael.Pietsch@hbgusa.com

Copy us at: readers-united@amazon.com

Please consider including these points:

- We have noted your illegal collusion. Please stop working so hard to overcharge for ebooks. They can and should be less expensive.

- Lowering e-book prices will help – not hurt – the reading culture, just like paperbacks did.

- Stop using your authors as leverage and accept one of Amazon’s offers to take them out of the middle.

- Especially if you’re an author yourself: Remind them that authors are not united on this issue.

Thanks for your support.

The Amazon Books Team

P.S. You can also find this letter at www.readersunited.com

If you don’t know, this is a response to an unprecedented letter written by a group of major authors (Stephen King amongst them) and supported by 900 more (yes!). At the weekend they paid over 100K USD to take a full page ad in the New York Times. (This appears in the next post.)

The Amazon response is pretty clever. You’d be forgiven for thinking that it was a little independent company. In fact it’s more than 7 time bigger than the largest book publishing company in the world (Pearson).

Opportunities

But these are curious times. There’s no question that Amazon is carrying out a Napoleonic sweep across Publishing, burning the past in its wake; but the effect, and their method, is to create mini-publishers of hundreds of thousands authors, empowering us, if we are willing, to work the system, market, sell and engage with our readers.

Changes

ChangesIt’s true, it does not make sense to price an ebook at the same level as a hardback (if that’s what Hachette are actually doing). My opinion is that paperback prices and ebook prices should be equivalent, with room to price promote immediately and track the results, as is possible with all ebooks. A printed hardback is an old fashioned way of publishers trying to recover a loss on the the large number of books they publish, while waiting for luck to hit the one title they hadn’t guessed would be a success, and extend the life across various formats.

But the market has changed, and it’s Amazon has changed it, with their consumer-facing flexibility and immediacy. They’ve burned through billions of dollars of investment, more that any publisher could dream of, but the fact is, they are here, and they give the sort of short term benefit that the consumer (i.e. readers) loves.

Post with Bestselling Author letter to Amazon, is here.

Post on the context for this battle, coming just after.

Filed under: Fiction, Writer's Advice Tagged: amazon, ebooks, Hachette, hardback books, indie publishing, KDP, kindle, paperback books, Pearson, self-publishing

July 15, 2014

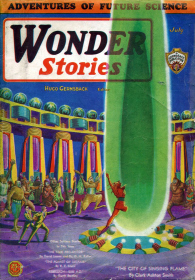

Virgil Finlay: Master of Dark Fantasy Illustration

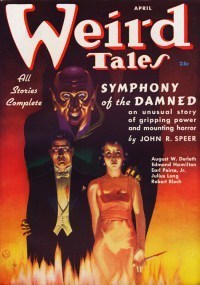

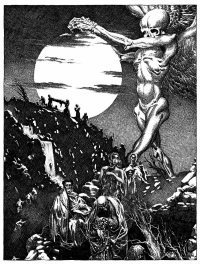

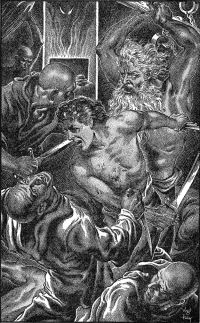

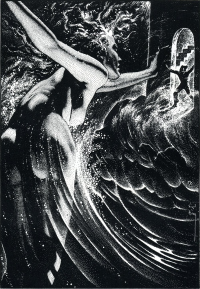

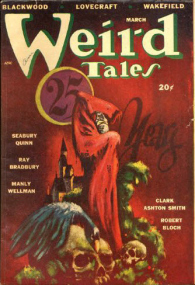

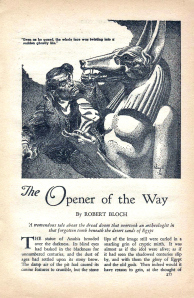

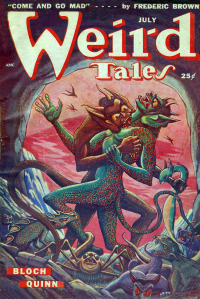

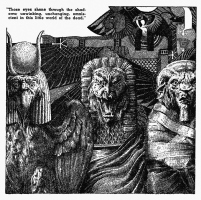

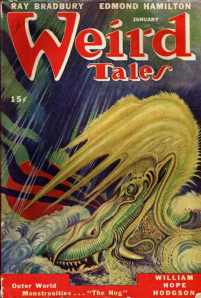

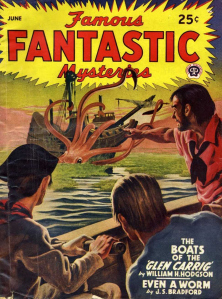

Virgil Finlay was a contemporary of H. P. Lovecraft, Robert Bloch and Robert E. Howard. He started as an illustrator on Weird Tales, went on to create fantastic art for the best genre fiction of his day, (Clark Ashton Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury) and for many of the other pulp magazines: Fantastic Novels, Super Science Stories, Thrilling Wonder, and Famous Fantastic Mysteries. He is regarded as one of the great twentieth century illustrators of horror, sf and fantasy at the point when these genres met the mass market in the Golden Age of the Pulps, then the Golden Age of Science Fiction. He made ever 2500 artworks, a remarkable achievement given his painstaking method of scratchboard and ink.

Early Years and Inspirations

Finlay was born in 1914, in Rochester, New York, at an exciting period for artists, released by modernism and the heady popularity of adventurous literature; but it was a perilous era for anyone trying to make a living. Born just before the First World War Finlay was delivered to hardworking, but impoverished parents as the family was hit by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Finlay’s inherited work ethic both supported and confined him, as the tireless industry of his technique suffocated any form of great enterprise.

But the young Finlay loved his art. He surrounded himself with the inspiration that would nudge him into a lifetime of aliens, robots, demons and sirens. His imagination was stirred by the shining stars of commercial art that decorated the magazines, newspapers, and books of the time. This was the era of the pulps but had started with the Golden Age illustrators, of Arthur Rackham, Franklin Booth, Maxfield Parrish, Howard Pyle, and Joseph Clement Coll. These artists created the direct and powerful illustrations for the thrilling stories of the time, from Arthur Conan Doyle, to Brothers Grimm, mythological tales of the Native American, the Celts and the Ancient Greeks. Booth was a giant of such illustration creating detailed pen and ink work that would make commercial art respectable and Clement Coll’s old school craftsmanship would add a darker and more mysterious mood to the fertile imagination of the young Finlay. During this period Alexander Anderson too was the first american engraver and much admired by this generation of eager dreamers.

But the young Finlay loved his art. He surrounded himself with the inspiration that would nudge him into a lifetime of aliens, robots, demons and sirens. His imagination was stirred by the shining stars of commercial art that decorated the magazines, newspapers, and books of the time. This was the era of the pulps but had started with the Golden Age illustrators, of Arthur Rackham, Franklin Booth, Maxfield Parrish, Howard Pyle, and Joseph Clement Coll. These artists created the direct and powerful illustrations for the thrilling stories of the time, from Arthur Conan Doyle, to Brothers Grimm, mythological tales of the Native American, the Celts and the Ancient Greeks. Booth was a giant of such illustration creating detailed pen and ink work that would make commercial art respectable and Clement Coll’s old school craftsmanship would add a darker and more mysterious mood to the fertile imagination of the young Finlay. During this period Alexander Anderson too was the first american engraver and much admired by this generation of eager dreamers.

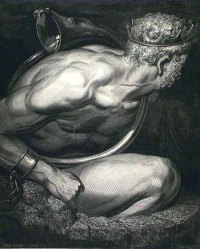

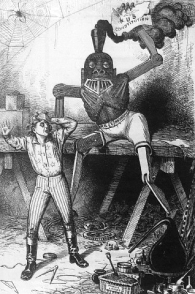

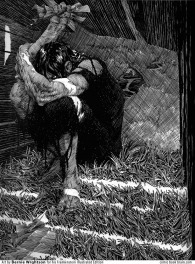

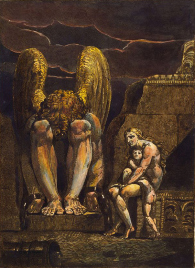

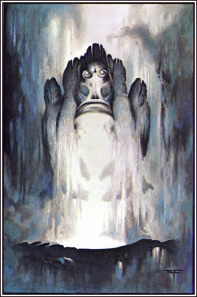

Finlay’s own art developed in the late 1920s and 30s and a settled on scratchboard illustration. For him, and many others of that generation the visual impact of the technique could be traced back to Gustave Dore‘s fantastical worlds and, further, to Henry Fuselli whose fearful, gothic compositions focused on single subjects with little but the dark backgrounds to frame their purpose.

Finlay’s own art developed in the late 1920s and 30s and a settled on scratchboard illustration. For him, and many others of that generation the visual impact of the technique could be traced back to Gustave Dore‘s fantastical worlds and, further, to Henry Fuselli whose fearful, gothic compositions focused on single subjects with little but the dark backgrounds to frame their purpose.

When we look at the inspirations of an artist it is too easy to fall into a historical narrative, but for the artists themselves, it doesn’t matter where the art comes from. Dore’s line engravings of Dante’s Inferno, Martin Schmidts‘ stipple engravings of Fuselli’s Nightmare), Rockwell Kent‘s Blakean Moby Dick woodcuts, Booth’s elegant pen and ink work, all would have been consumed by Finlay who was entranced by the fierce detail of such art. It is hard to tell exactly why he fell for the scratchboard technique, but it gave him the satisfaction and clarity that would please both his desire to echo his inspirations, and the earn the appreciation of readers of the pulps of the 1930s and 40s.

When we look at the inspirations of an artist it is too easy to fall into a historical narrative, but for the artists themselves, it doesn’t matter where the art comes from. Dore’s line engravings of Dante’s Inferno, Martin Schmidts‘ stipple engravings of Fuselli’s Nightmare), Rockwell Kent‘s Blakean Moby Dick woodcuts, Booth’s elegant pen and ink work, all would have been consumed by Finlay who was entranced by the fierce detail of such art. It is hard to tell exactly why he fell for the scratchboard technique, but it gave him the satisfaction and clarity that would please both his desire to echo his inspirations, and the earn the appreciation of readers of the pulps of the 1930s and 40s.

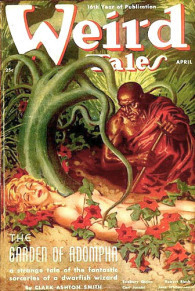

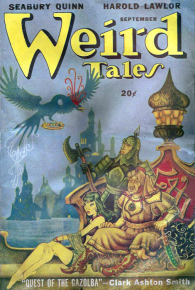

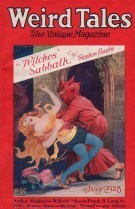

Weird Tales

In December 1935 he sent 6 artworks to Farnsworth Wright, then editor of Weird Tales, one of the magazines that would have bewitched a young man desperate to see his work featured alongside his storytelling heroes, H. P. Lovecraft, Abraham Merritt and Robert E. Howard. By all accounts Wright loved the art but was concerned that the detail would translate only into a muddy mass on the rough pulp of the magazine. A few tests persuaded him otherwise and so began a long career of inventive illustration, with Finally providing mainly interior, but occasional cover art for Weird Tales, entrancing an audience that had been used to simple decorations and dense lines of text. Finlay brought the stories to life, drew the reader in, made the tales of Merritt, C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner sing on the page. His work was greatly admired by the writers, Kuttkner became a close friend, Lovecraft , Seabury Quinn and Merritt wrote in glowing terms as the appreciation of his work, garnered further publication in other popular pulps, Amazing, Fantastic Adventures, and Strange Stories.

In December 1935 he sent 6 artworks to Farnsworth Wright, then editor of Weird Tales, one of the magazines that would have bewitched a young man desperate to see his work featured alongside his storytelling heroes, H. P. Lovecraft, Abraham Merritt and Robert E. Howard. By all accounts Wright loved the art but was concerned that the detail would translate only into a muddy mass on the rough pulp of the magazine. A few tests persuaded him otherwise and so began a long career of inventive illustration, with Finally providing mainly interior, but occasional cover art for Weird Tales, entrancing an audience that had been used to simple decorations and dense lines of text. Finlay brought the stories to life, drew the reader in, made the tales of Merritt, C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner sing on the page. His work was greatly admired by the writers, Kuttkner became a close friend, Lovecraft , Seabury Quinn and Merritt wrote in glowing terms as the appreciation of his work, garnered further publication in other popular pulps, Amazing, Fantastic Adventures, and Strange Stories.

All of Finlay’s WT work is good—especially the designs for your Lost Paradise & Bloch’s Faceless God. Bloch tells me that Wright considers the latter the finest illustration ever drawn for WT, & that the original hangs framed in the office.

H.P. Lovecraft to C. L Moore, 1936

Finlay’s technique distinguished himself from his fellows, with only Hannes Bok coming close to his mastery of the sf and fantasy mode. Although Finlay’s compositional focus and background detail was not his greatest strength, he created unsurpassed mood with the graduations of dots, recalling the effects of the engravers and woodcutters so admired in his youth. A special edition of Midsummer Night’s Dream was created to highlight his astonishing work, and although this was not a success in his lifetime is much admired today and was found to have been collected by his greatest contemporary rival, Bok.

Finlay’s technique distinguished himself from his fellows, with only Hannes Bok coming close to his mastery of the sf and fantasy mode. Although Finlay’s compositional focus and background detail was not his greatest strength, he created unsurpassed mood with the graduations of dots, recalling the effects of the engravers and woodcutters so admired in his youth. A special edition of Midsummer Night’s Dream was created to highlight his astonishing work, and although this was not a success in his lifetime is much admired today and was found to have been collected by his greatest contemporary rival, Bok.

Abraham Merritt, who had achieved exalted status in the pulp era, with his early novels, The Moon Pool (1918), Metal Monster (1920) and The Ship of Ishtar (1924) became an editor on American Weekly (a sunday newspaper supplement selling in its millions); he commissioned Finlay as staff artist, to illustrate stories, articles and make decorations. Over a few short years more than 800 artworks were published, mainly executed in Finlay’s painstaking style.

Abraham Merritt, who had achieved exalted status in the pulp era, with his early novels, The Moon Pool (1918), Metal Monster (1920) and The Ship of Ishtar (1924) became an editor on American Weekly (a sunday newspaper supplement selling in its millions); he commissioned Finlay as staff artist, to illustrate stories, articles and make decorations. Over a few short years more than 800 artworks were published, mainly executed in Finlay’s painstaking style.

The late 1930s were a busy period for Finlay, a man fulfilling his potential and living in a world that made sense to him at last: he married, moved to New York City, took night classes in technical drawing, worked for a wide range of magazines, created the iconic cover for Arkham House‘s first book, Lovecraft’s The Outside and Others (1939), and corresponded with his collaborators, many of whom had been his childhood heroes.

Works and Awards

Although interrupted by the Second World War Finally still managed to illustrate stories while serving, and as the Golden Era of the Pulps waned, he continued to produce for Fantastic Novels, Super Science Stories, Thrilling Wonder, and Famous Fantastic Mysteries. As this work thinned out, his much admired art was picked up by the new wave of digests such as Famous Science Fiction and Astrology, although their circulation was considerably lower.

Finlay’s art was widely appreciated both by fans and fellow creators, and his enduring contribution was recognized by a series of awards from the late 1940s: Best fantasy artist in the Beowulf Poll, 1941 and 1945, Best fantasy Illustrator, Fantasy Annual 1948, Best Interior Illustrator, Hugo Award 1953 (the first to receive what is now a long tradition of excellence). A hard-working, modest man he rarely appeared in public, even to receive the awards, although he attended a presentation where his incredible gifts were acknowledged with the award of ‘Dean of Science-Fiction Art for unexcelled imagery and technique’ by The Eastern Science Fiction Association in 1964.

Finlay’s art was widely appreciated both by fans and fellow creators, and his enduring contribution was recognized by a series of awards from the late 1940s: Best fantasy artist in the Beowulf Poll, 1941 and 1945, Best fantasy Illustrator, Fantasy Annual 1948, Best Interior Illustrator, Hugo Award 1953 (the first to receive what is now a long tradition of excellence). A hard-working, modest man he rarely appeared in public, even to receive the awards, although he attended a presentation where his incredible gifts were acknowledged with the award of ‘Dean of Science-Fiction Art for unexcelled imagery and technique’ by The Eastern Science Fiction Association in 1964.

Legacy

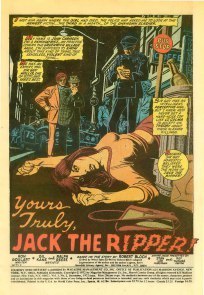

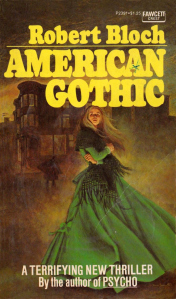

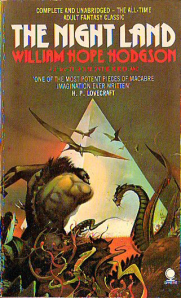

Virgil Finlay died of cancer in 1971. He had illustrated the entire canon of science fiction and fantasy: Clark Ashton Smith, Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, H.P. Lovecraft, Abraham Merritt, H.G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, Frank Belknapp, Long Arthur C. Clarke ,Theodora Sturgeon, Otis Kline, ERB, H. Rider Haggard and many more. The inheritors of the gothic novel aided by the technology of the twentieth century had taken flight and found in Virgil Finally, a creative partner who was their equal. His work graced the magazines that launched their reputations, and he created a look and feel of sf and fantasy that prevails still today: in John Schoenherr‘s art for Frank Herbert‘s original Dune, in Analog, Bernie Wrighton‘s darkly horrific work in Warren Magazines, the spacescapes of Star Trek of the 1960s and Star Wars of the 70s, Stanley Kubrick‘s pioneering sf movies, (2001, 2010), the deep terrors of the Alien movies, and so much more. Virgil Finlay’s fine dots, and his elegant and effective lines, are etched indelibly into the foundations of science fiction and fantasy offering us imaginative visions of far-flung futures that sit somewhere between hope and uncomfortable fact.

Virgil Finlay died of cancer in 1971. He had illustrated the entire canon of science fiction and fantasy: Clark Ashton Smith, Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, H.P. Lovecraft, Abraham Merritt, H.G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, Frank Belknapp, Long Arthur C. Clarke ,Theodora Sturgeon, Otis Kline, ERB, H. Rider Haggard and many more. The inheritors of the gothic novel aided by the technology of the twentieth century had taken flight and found in Virgil Finally, a creative partner who was their equal. His work graced the magazines that launched their reputations, and he created a look and feel of sf and fantasy that prevails still today: in John Schoenherr‘s art for Frank Herbert‘s original Dune, in Analog, Bernie Wrighton‘s darkly horrific work in Warren Magazines, the spacescapes of Star Trek of the 1960s and Star Wars of the 70s, Stanley Kubrick‘s pioneering sf movies, (2001, 2010), the deep terrors of the Alien movies, and so much more. Virgil Finlay’s fine dots, and his elegant and effective lines, are etched indelibly into the foundations of science fiction and fantasy offering us imaginative visions of far-flung futures that sit somewhere between hope and uncomfortable fact.

Links

A couple of Pinterest boards are linked to this blog: one packed with Virgil Finlay‘s art, another with examples of scratchboard technique from other great artists.

Other posts of interest in These Fantastic Worlds include:

Henry Fuseli: Dark Gothic Fantasy

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF Classics

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

H. P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

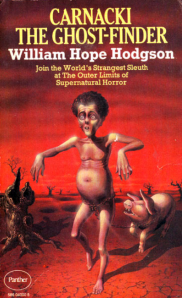

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

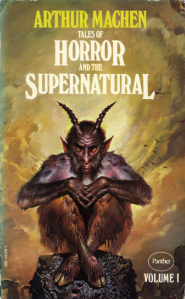

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

Filed under: Art & Artists, Only Connect Tagged: Dark fantasy, Golden Age of Illustrators, Golden Age of Science Fiction, Gustave Dore, H.P. Lovecraft, Henry Fuselli, Horror, Hugo Awards, Pulp Magazines, Robert Bloch, Robert E Howard, science fiction, Supernatural, Weird Tales

June 26, 2014

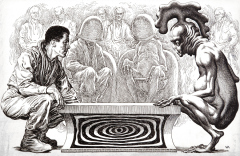

Clark Ashton Smith: Master of Gothic, Pulp and SF classics

Golden Age writer of over 100 stories Clark Ashton Smith enjoyed a reputation for fast-paced, evocative narratives in the thrilling forms of the golden age genre fiction: horror, science fiction, heroic fantasy and the macabre. He was a successor to H.P. Lovecraft, a fellow of Robert E. Howard and his relatively long life allows us a view of his place on the development of modern genre fiction, and his link between H.G Wells‘ early pioneering sf, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, to it’s harrowing conclusion in Stephen King and Clive Barker at the end.

Early Life and influences

Ashton Smith was born in January, 1893, in Long Valley, California. He was delivered into a tight family unit and barely left it. Home schooled from an early age he read all the time, and clearly possessed a love of language that served him well throughout his life. As he emerged into adulthood he was influenced by two strong literary forces.

Ashton Smith was born in January, 1893, in Long Valley, California. He was delivered into a tight family unit and barely left it. Home schooled from an early age he read all the time, and clearly possessed a love of language that served him well throughout his life. As he emerged into adulthood he was influenced by two strong literary forces.

George Sterling, a Californian poet of the generation before Ashton Smith, was mentored by gothic colossus Ambrose Bierce, and was a bohemian experimentalist in the style of the Romantic poets, Coleridge in particular whose florid style of poetry explored dreamscapes and other worlds. Similarly inclined Ashton Smith fell under Sterling’s spell, as the older man encouraged his fellow Californian: the rich dense language of the younger man’s poetry bears the indelible mark of Sterling, and although it was critically well received in his lifetime, it remains largely neglected by the reading public.

The other early influence was Baudelaire. Although a great thinker and poet he was brought to the attention Ashton Smith’s generation because of his bold translations of the hugely popular Edgar Allan Poe, the hero of dark horror. But it was Baudelaire who created the earliest roots of modernism that would rise up and storm the 20th century. He sought to capture the ephemeral urban existence of industrial Europe and America, broke free of the status quo and unleashed a wave of critical thinking that would stir all forms of culture, from music (Debussy, Satie) and the painted arts (Kandinky, Picasso), to T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster, and other titans of the written word, creating a landscape into which was fed a gigantic wave of imaginative fiction. In America the price of wood pulp reduced so much that very cheap magazines could be produced and soon were devoured in their millions by a readership that looked for excitement and escapism of far flung landscapes. Ashton Smith read, translated and absorbed Baudelaire, revelling in the journey that would bring him to friendship with H. P. Lovecraft and the opportunities of the Golden Age of Pulp.

The other early influence was Baudelaire. Although a great thinker and poet he was brought to the attention Ashton Smith’s generation because of his bold translations of the hugely popular Edgar Allan Poe, the hero of dark horror. But it was Baudelaire who created the earliest roots of modernism that would rise up and storm the 20th century. He sought to capture the ephemeral urban existence of industrial Europe and America, broke free of the status quo and unleashed a wave of critical thinking that would stir all forms of culture, from music (Debussy, Satie) and the painted arts (Kandinky, Picasso), to T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster, and other titans of the written word, creating a landscape into which was fed a gigantic wave of imaginative fiction. In America the price of wood pulp reduced so much that very cheap magazines could be produced and soon were devoured in their millions by a readership that looked for excitement and escapism of far flung landscapes. Ashton Smith read, translated and absorbed Baudelaire, revelling in the journey that would bring him to friendship with H. P. Lovecraft and the opportunities of the Golden Age of Pulp.

Weird and Wonder Tales

His first short stories were sold, at the young age of seventeen, to The Black Cat and Overland Monthly, and his poetry was published in anthologies, and journals such as The Yale Review, Wings and many more. But it was the opening of Weird Tales in the early 1920s, that introduced him to the weird and fantastic worlds of 20th century mass market literature.

His first short stories were sold, at the young age of seventeen, to The Black Cat and Overland Monthly, and his poetry was published in anthologies, and journals such as The Yale Review, Wings and many more. But it was the opening of Weird Tales in the early 1920s, that introduced him to the weird and fantastic worlds of 20th century mass market literature.

Still living at home, and isolated from smart society Ashton Smith found kindred spirits in Lovecraft and Howard both of whom weaved stories of savage lands and dark terrors from their own remote locations. Mainly by correspondence he was also introduced to others of this circle, August Derleth and E. Hoffman Price, Robert Bloch and together they created stories that interwove, sought meaning in a godless society, and focused on a form of sensuous masculinity that would become the sword and sorcery strand of fantasy writing.

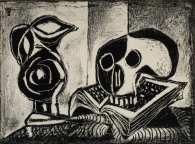

For Ashton Smith though he also experimented heavily with far future narratives, in a concentration of short stories in Weird Tales (starting with The Last Incantation in June 1930 edition) and Wonder, from the early to mid 1930s. He continued still to live in the rural idyll with his parents and created sculptures as well as fiction and poetry. These 3D forms, and paintings offer glimpses of a unique vision, without quite delivering the quality of a Giacometti or a Picasso. He led an enviable life of utter immersion, working long days in his studio creating macabre objects (such as mini statues of the elder gods Cthulhu, Yuggoth and Hastur) that populated the world of his writing.

For Ashton Smith though he also experimented heavily with far future narratives, in a concentration of short stories in Weird Tales (starting with The Last Incantation in June 1930 edition) and Wonder, from the early to mid 1930s. He continued still to live in the rural idyll with his parents and created sculptures as well as fiction and poetry. These 3D forms, and paintings offer glimpses of a unique vision, without quite delivering the quality of a Giacometti or a Picasso. He led an enviable life of utter immersion, working long days in his studio creating macabre objects (such as mini statues of the elder gods Cthulhu, Yuggoth and Hastur) that populated the world of his writing.

Works

Many of Ashton Smith’s themes reflect his association with the Lovecraft circle (within which he created the Land of Averoigne, the Book of Eibon and Tsathoggua), and he was a key figure at the nexus of horror, sword and sorcery and science fiction, creating Hyperborean fantasy that was taken up by Lin Carter and L. Sprague le Camp. But his highly imaginative writing also took him from ancient civilizations and rastionalistic gods, to explorations of deep space, and the effects of the unknown on humanity, teasing at the greed and avarice, feasting on a body that also nourished Ray Bradbury’s own burgeoning sf.

Unlike Howard and Lovecraft who both died in 1936 and 1937 respectively Ashton Smith was able to move from the Golden Age of Pulp to the new Golden Age of Science Fiction and enjoyed publication by friends and colleagues such as Lin Carter and August Derleth in the 1940s and 50s.

Unlike Howard and Lovecraft who both died in 1936 and 1937 respectively Ashton Smith was able to move from the Golden Age of Pulp to the new Golden Age of Science Fiction and enjoyed publication by friends and colleagues such as Lin Carter and August Derleth in the 1940s and 50s.

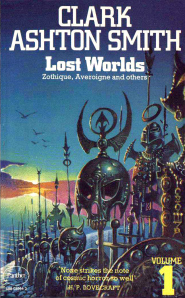

Key stories include The City of the Singing Flame (July 1931 Wonder Stories), The End of the Story, A Night in Malnéant, The Double Shadow, The Return of the Sorcerer, and The Dark Eidolon, with major works collected as Out of Space and Time (1942), Lost Worlds (1944), The Abominations of Yondo (1960) Tales of Science and Sorcery (1964). Much of his writing has been anthologized over the years, in many different forms, but a particularly good sequence, The Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith in five volumes was published by Night Shade Books from The End of the Story (Volume 1, 2006), to The Last Hieroglyph in 2010.

Legacy

After his parents died, Ashton Smith married, in 1954, just eight short years before his own death in California in 1961. For most of his life he had lived in the bosom of his family and the countryside, with its incubations that fed his fertile imagination. His work affected contemporaries such as Robert Bloch and Ray Bradbury, and his influence can be felt in Ramsey Campbell, Kurt Vonnegut, Stephen King and Clive Barker. He lived a remarkable life, writing when he wanted to, but also taking odd jobs crafting and cutting and grinding. He was an intensely practical man who combined his understanding of the physical world around him with a fierce imagination, and worked hard to create a huge canon of fiction that remains enjoyable and thrilling today.

After his parents died, Ashton Smith married, in 1954, just eight short years before his own death in California in 1961. For most of his life he had lived in the bosom of his family and the countryside, with its incubations that fed his fertile imagination. His work affected contemporaries such as Robert Bloch and Ray Bradbury, and his influence can be felt in Ramsey Campbell, Kurt Vonnegut, Stephen King and Clive Barker. He lived a remarkable life, writing when he wanted to, but also taking odd jobs crafting and cutting and grinding. He was an intensely practical man who combined his understanding of the physical world around him with a fierce imagination, and worked hard to create a huge canon of fiction that remains enjoyable and thrilling today.

Other articles coming soon on Virgil Finlay, Robert E. Howard, M.R. James, Ambrose Bierce, Edgar Allan Poe and Ray Bradbury.

Links

Other posts of interest in These Fantastic Worlds include:

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

H. P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

Henry Fuseli: Dark Gothic Fantasy

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

Clark Ashton Smith has inspired fierce loyalty amongst his fans. Eldritch Dark is a terrific website with art, poetry, analysis and writing, and a gallery of his cultures and paintings.

Filed under: Fiction, Only Connect Tagged: Dark fantasy, Edgar Allan Poe, gothic, H.P. Lovecraft, Horror, kandinsky, Modernism, Picasso, Robert Bloch, Virgil Finlay, Weird Tales

June 12, 2014

Henry Fuseli: Dark Gothic Fantasy

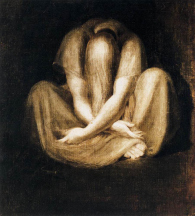

The early gothic found ghastly, thrilling form in the supernatural intimations of Henry Fusili. A writer, translator and artist of fierce intelligence we know him primarily as the creator of the famous Nightmare painting, with its incubus sitting on the limp chest of a slumbering female form, and a leering, supernatural ‘night mare’ casting its glowing eyes across the scene.

Fusili though was a towering figure in late 18th Century and his work forges links between great tragedic literature of Shakespeare and Milton, and popular culture classics of the modern era. He was an energetic man whose prodigious works rose above the stagnant classicism of his day to wage a cultural war against the a British Establishment that was on the brink of losing America, and fearful in the face of an apocalyptic, revolutionary France.

Fusili though was a towering figure in late 18th Century and his work forges links between great tragedic literature of Shakespeare and Milton, and popular culture classics of the modern era. He was an energetic man whose prodigious works rose above the stagnant classicism of his day to wage a cultural war against the a British Establishment that was on the brink of losing America, and fearful in the face of an apocalyptic, revolutionary France.

Early Years

Fusilli was born in Zurich, Swizerland in 1741. His father was a celebrated portrait painter at a time in Europe when the well-bred and literary elite studied throughout the great cities of the continent. An ordained minister he was obliged to leave the country of his birth due to a youthful outburst against local dignitary, a sign of the strong convictions that would leave its mark throughout his life.

He found himself in London in 1764 and the good fortune of parentage granted him access to high society: he soon met a friend of his father, Joshua Reynolds, the celebrated painter and founding president of the Royal Academy (RA), who advised him to go to Italy and learn his trade as a painter. With some initial reluctance he departed, spent eight years studying the graceful sinews of Michelangelo and came to lead a group of firebrand painters, writers and thinkers.

In the years after his return to London Fuselli gained a reputation for painting direct and powerful works that echoed the disenchantment of with the corrupt institutions of state and am Hanovarian aristocracy that had grown effete and aloof. Fuselli’s intensity and his incendiary preoccupation with the supernatural found a willing audience in a public fixated on the early gothic novel, and it is this association that shaped both his popularity, and an inspiration that is still felt, nearly 250 years later.

In the years after his return to London Fuselli gained a reputation for painting direct and powerful works that echoed the disenchantment of with the corrupt institutions of state and am Hanovarian aristocracy that had grown effete and aloof. Fuselli’s intensity and his incendiary preoccupation with the supernatural found a willing audience in a public fixated on the early gothic novel, and it is this association that shaped both his popularity, and an inspiration that is still felt, nearly 250 years later.

Era and Culture

In March 1775 Goethe said, “What fire and fury the man has in him.” Fuselli was admired by artists, writers, thinkers and composers of a Sturm und Drang movement that created a fortress against stale classicism: Goethe, Wagner, Schiller and the philosopher Hamann celebrated the individual response to art rather than the collective acceptance of classical norms, focusing on the real and, to shock their audiences into action, used extremes of human emotion rather than perceptions of classical truth and beauty. They formulated the horrific and terrific as a means of inducing such effects, and this would prepare the ground for the Romantic poets with their wild imaginings, of Coleridge, Keats, Shelley and Lord Byron, and the Romantic artists, Romney, Gainsborough and Constable who gloried in the world around them, offering sumptuous landscapes of the contemporary world.

But this was also the time of Thomas Paine, William Godwin, Joseph Priestley, and Mary Wollstonecraft, thinkers and radicals who traced an intellectual orbit around publisher Joseph Johnson. Fuselli was powerful voice in their literary lunches, a campaigner against slavery and the status quo. Such gatherings were echoed throughout Europe and the Americas as intellectuals discussed the shortcomings of the various inbred institutions that had carried Nation-States into war, continents into slavery and the corrupt instruments of Empire, the East India Companies. In New York, Charles Brockden Brown revelled in constitution building in New York, wrote pamphlets, critiques and american gothic novels, in Weimar Goethe breathed the fire of secular damnation and in London William Blake harangued politicians, priests and public alike.

But this was also the time of Thomas Paine, William Godwin, Joseph Priestley, and Mary Wollstonecraft, thinkers and radicals who traced an intellectual orbit around publisher Joseph Johnson. Fuselli was powerful voice in their literary lunches, a campaigner against slavery and the status quo. Such gatherings were echoed throughout Europe and the Americas as intellectuals discussed the shortcomings of the various inbred institutions that had carried Nation-States into war, continents into slavery and the corrupt instruments of Empire, the East India Companies. In New York, Charles Brockden Brown revelled in constitution building in New York, wrote pamphlets, critiques and american gothic novels, in Weimar Goethe breathed the fire of secular damnation and in London William Blake harangued politicians, priests and public alike.

Contradictions and Conformism.

In common with artists throughout history, Fuseli’s ethical position was complex: painters require wealthy sponsors. The radical and reforming tended to be less prosperous so although Fuselli associated with William Roscoe (an affluent campaigner against slavery), he also consorted with Thomas Coutts, the banker. Along with Schiller, Goethe, Beethoven and other remarkable artists he endured periods of utter conformism, in order to survive and it is curious to identify the Professor of Art at the uber-institutional Royal Academy as a founder of the gothic mode. His personal work was drenched in deviation, sexuality and challenged every acceptable concept of the art he taught to the obliging and well-connected students of the RA. His po-faced translation of ‘Winckleman’s Reflections on Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks’ and revision of a ‘Dictionary of Painters’ was conducted at the same time as his dark and sensual paintings.

From 1785-1799 he participated in John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, a project designed to educate Europe into the benefits of the greatest English dramatist, but also to forge a base for historical painting. It was an idea conceived at a dinner with the Lord Mayor of London, and Boydell and several other great painters of the day, and reinforced the institutional game of survival and patronage. Shakespeare though was a lifelong obsession and we can detect the origins of Fuseli’s gothic awakening in the dark, supernatural corners of Macbeth, Hamlet, Lear and Midsummer Night’s Dream. Almost as a rite of passage Fusilli would go on to illustrate all other great literary works: Milton, Norse Legends, Dante, Spenser’s Faerie Queen and more.

From 1785-1799 he participated in John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, a project designed to educate Europe into the benefits of the greatest English dramatist, but also to forge a base for historical painting. It was an idea conceived at a dinner with the Lord Mayor of London, and Boydell and several other great painters of the day, and reinforced the institutional game of survival and patronage. Shakespeare though was a lifelong obsession and we can detect the origins of Fuseli’s gothic awakening in the dark, supernatural corners of Macbeth, Hamlet, Lear and Midsummer Night’s Dream. Almost as a rite of passage Fusilli would go on to illustrate all other great literary works: Milton, Norse Legends, Dante, Spenser’s Faerie Queen and more.

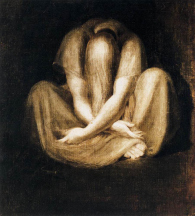

Our vision of Fusilli is dominated by a few of his most celebrated paintings, many of which express the night-time terrors and the power of dreams over the conscious form: Nightmare, (1781), Titania and Bottom (c.1790), The Three Witches (1783) and The Shepherd’s Dream (1793), Mrs. Fuseli Seated by a Fireplace (1799), Macbeth Consulting the Vision of the Armed Head (1793), Wolfram Looking at his Wife, whom he has Imprisoned with the Corpse of her Lover (1812-20), A Sleeping Woman and the Furies (1821).

Our vision of Fusilli is dominated by a few of his most celebrated paintings, many of which express the night-time terrors and the power of dreams over the conscious form: Nightmare, (1781), Titania and Bottom (c.1790), The Three Witches (1783) and The Shepherd’s Dream (1793), Mrs. Fuseli Seated by a Fireplace (1799), Macbeth Consulting the Vision of the Armed Head (1793), Wolfram Looking at his Wife, whom he has Imprisoned with the Corpse of her Lover (1812-20), A Sleeping Woman and the Furies (1821).

The Gothic Sensibility

The Gothic is often lambasted for its stock characters and formulaic situations, but these are fundamental to the structure of its effect. They represent the constant echo, the toll of a familiar bell that draws the reader in to revel in dream-like terrors, a reader both comforted and excited by the horrors within.

In the latter stages of the 18th century the rise of the gothic was associated with what were regarded as feminine values of imagination, rather than the robust civic values aligned to government and masculine thought. Britain was a highly conformist society, used to success after its hard-won defeat of the traditional enemies, France and Spain: it was shaken by the revolution in America and soon the shocking republicanism of France. The forces that created these challenges represented a way of thinking that was alien and dangerous to the ruling elite, but provided excitement to a generation of readers, writers, artists and musicians who relished the new creative landscapes.

In the latter stages of the 18th century the rise of the gothic was associated with what were regarded as feminine values of imagination, rather than the robust civic values aligned to government and masculine thought. Britain was a highly conformist society, used to success after its hard-won defeat of the traditional enemies, France and Spain: it was shaken by the revolution in America and soon the shocking republicanism of France. The forces that created these challenges represented a way of thinking that was alien and dangerous to the ruling elite, but provided excitement to a generation of readers, writers, artists and musicians who relished the new creative landscapes.

The Gothic boom of this period offered new heroic models. The languid classical heroes appeared to have failed and were replaced by the tragic fire-breathing males of Matthew Lewis’s Monk, Fusilli’s Wolfram and Goethe’s Faust, and lapped up by a new breed of female reader who sought the escapist fantasies of Ann Radcliffe in particular, whose heroes would not rush off to war to die, but stay at home to woo and cherish their languid lovers.

The traditional newspaper press would attempt to skewer this gothic obsession and Fusilli’s work was caught in the crossfire; he was often dismissed as a fantasist who created whimsical and frivolous scenes without classical authenticity; but Fusilli was his own man, creating wild-eyed, exaggerated forms with a heavy emphasis on the central figures and little or no background. He used strongly contrasting light and filled the canvas with shadows to create a form of art that was devoured by the gothic reading public and today could be recognized as a precursor to the mass market comic books and the early sf and fantasy paperback covers of the 1930s and 40s, with their lurid colours and direct, seductive effects. This became the space occupied by Frank Frazetta, Jeffrey Catherine Jones and Virgil Finlay, who displayed dark forms that both intrigued and terrified an excitable 20th Century audience.

The traditional newspaper press would attempt to skewer this gothic obsession and Fusilli’s work was caught in the crossfire; he was often dismissed as a fantasist who created whimsical and frivolous scenes without classical authenticity; but Fusilli was his own man, creating wild-eyed, exaggerated forms with a heavy emphasis on the central figures and little or no background. He used strongly contrasting light and filled the canvas with shadows to create a form of art that was devoured by the gothic reading public and today could be recognized as a precursor to the mass market comic books and the early sf and fantasy paperback covers of the 1930s and 40s, with their lurid colours and direct, seductive effects. This became the space occupied by Frank Frazetta, Jeffrey Catherine Jones and Virgil Finlay, who displayed dark forms that both intrigued and terrified an excitable 20th Century audience.

Archetypes and Stereotypes

Against the convention of the time Fuseli invented many of his own heroes and heroines (Ezzelin, Belisaire) , creating them as archetypes and ciphers, not just regurgitations of other artist’s work. Classical and biblical stories were not rejected but assimilated into the fantastic and Fuseli became an icon of the gothic aesthetic as the supernatural and the power of the unconscious mind played out in the dream-like palette of his paintings.

Against the convention of the time Fuseli invented many of his own heroes and heroines (Ezzelin, Belisaire) , creating them as archetypes and ciphers, not just regurgitations of other artist’s work. Classical and biblical stories were not rejected but assimilated into the fantastic and Fuseli became an icon of the gothic aesthetic as the supernatural and the power of the unconscious mind played out in the dream-like palette of his paintings.

Fuseli’s work represents men and women in clear physical forms. We do not rely on the legacy of classical behavioural norms to identify their behaviour. These characters live in the moment, and they suffer supernatural actions and fantasies. The women are subject still to the male, but at least the males are more gripped by emotional imagination than entirely heroic action.

Fuseli was still a man within a male dominated society, however radical his instincts might have been. Although he was one of the first artists to create his own heroes, still they were binary products of their time, bursting with stereotypical representations of the bold male, adored by the submissive, often languid female, offering a sexualised, response to navigate the problems of the day, the uncertainties and confusions. For modern tastes the woman is helpless or a hag, no hint of the Hunger Games or Buffy-like defiance, and no there is no moral aspect to the relative position of his men and women. But for the time Fuseli’s work was certainly revolutionary, and he was greatly censured for his stance.

Fuseli was still a man within a male dominated society, however radical his instincts might have been. Although he was one of the first artists to create his own heroes, still they were binary products of their time, bursting with stereotypical representations of the bold male, adored by the submissive, often languid female, offering a sexualised, response to navigate the problems of the day, the uncertainties and confusions. For modern tastes the woman is helpless or a hag, no hint of the Hunger Games or Buffy-like defiance, and no there is no moral aspect to the relative position of his men and women. But for the time Fuseli’s work was certainly revolutionary, and he was greatly censured for his stance.

Of course, it is hard to ignore a particular criticism of the gothic, that it is deliberately simplistic, appealing to the stereotypes, the guilty secret pleasures of its audiences, abandoning the sophistication of more elitist art. It’s no wonder that the gothic mode was so popular!

Legacy

Fuseli died on April 16, 1825 in Putney Hill. He was buried at St. Paul’s Cathedral, near Sir Joshua Reynolds who was the first to take his art seriously.

Fuseli has influenced so may of those that followed. There is something about the gothic sensibility itself that resonates with a primal instinct in humanity.

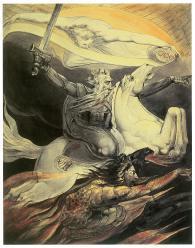

Fuseli’s impact ran through contemporaries such as George Romney, James Barry, John Flaxman, Theodor von Holst, and, of course, William Blake. Blake engraved some of Fuseli’s work and was a great admirer, although Fuselli did not care for Blake’s writing, especially his prophetic works, and his public enthusiasm for revolution. Blake’s Night of Enithamon’s Joy (1795), House of Death (1795), Death on a Pale Horse (1800) are clear descendants of Fuselli’s gothic aesthetic.

Fuseli’s impact ran through contemporaries such as George Romney, James Barry, John Flaxman, Theodor von Holst, and, of course, William Blake. Blake engraved some of Fuseli’s work and was a great admirer, although Fuselli did not care for Blake’s writing, especially his prophetic works, and his public enthusiasm for revolution. Blake’s Night of Enithamon’s Joy (1795), House of Death (1795), Death on a Pale Horse (1800) are clear descendants of Fuselli’s gothic aesthetic.

Mary Shelley too, her father William Godwin and mother Mary Wollstencroft were friends of Fuselli, drew on Fuselli’s dark themes for Frankenstein, and Edgar Allen Poe‘s gothic masterpiece ‘The Fall of the House of Usher‘ references Fuseli’s Nightmare, borrowing the effects of its dreamy horror and themes subconscious sexual jealousy.

In literature, amongst his many admirers in the 20th Century was H.P. Lovecraft, who confessed that “Fuseli really brings a shiver”; Algernon Blackwood, Stephen King, Angela Carter and Tony Morrison each inherit his influence. Early movies such as 1922′s Nosferatu, the first Dracula movie and probably the closest to the feel of Bram Stoker‘s novel, lit the action with the same contrasting intensity as Fuseli’s paintings while the dark gothic challenges of modern TV series such Buffy the Vampire Slayer leap forward into broader popular culture media such as manga and Twilight fan fiction.

In literature, amongst his many admirers in the 20th Century was H.P. Lovecraft, who confessed that “Fuseli really brings a shiver”; Algernon Blackwood, Stephen King, Angela Carter and Tony Morrison each inherit his influence. Early movies such as 1922′s Nosferatu, the first Dracula movie and probably the closest to the feel of Bram Stoker‘s novel, lit the action with the same contrasting intensity as Fuseli’s paintings while the dark gothic challenges of modern TV series such Buffy the Vampire Slayer leap forward into broader popular culture media such as manga and Twilight fan fiction.

Of course his demon seed can be found in the art of Margaret Brundage (illustrator of most of the 1930s Weird Tales covers), the dark, brooding shadows of Bernie Wrightson‘s Warren Magazine illustration and some of the more lurid work of Frank Frazetta and Jeffrey Catherine Jones, and Gene Colan

Of course his demon seed can be found in the art of Margaret Brundage (illustrator of most of the 1930s Weird Tales covers), the dark, brooding shadows of Bernie Wrightson‘s Warren Magazine illustration and some of the more lurid work of Frank Frazetta and Jeffrey Catherine Jones, and Gene Colan

Fuselli’s paintings made a convenient separation of morality from art. He created stereotypes of heroic men and submissive women, subject to the terror of their dreams and the shadows of jealous retribution. As Fuseli said, “our ideas are the offspring of our senses”, his work was hugely popular and his connection with the supernatural themes of Shakespeare’s dark tragedies to the gothic work of those that followed, the comic books, graphic novels, the paperbacks and the movies demonstrates the acute power of the gothic sensibility and the sheer power of imagination.

Links

Other posts of interest include:

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

H. P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

And here’s a Pinterest board on Fuseli and Dark Gothic Fantasy.

Filed under: Art & Artists, Only Connect Tagged: Dark fantasy, dracula, Frank Frazetta, Frankenstein, gothic, H.P. Lovecraft, Horror, Supernatural, William Blake

May 28, 2014

Algernon Blackwood: Master of Supernatural Fiction

“…such delicate phantasies as Jimbo or The Centaur. Mr. Blackwood achieves in these novels a close and palpitant approach to the inmost substance of dream, and works enormous havock with the conventional barriers between reality and imagination.” Supernatural Horror in Literature‘ 1926, H.P. Lovecraft.

Algernon Blackwood lived through the late Victorian era, the surge of modernism and literature, art and music, the great social changes that brought industrialization and consumerism to society, but he remained largely unaffected by it all. For many he is regarded as a stalwart of the modern ghost story, alongside M. R. James, but he wrote fiction with a heavy undertow of horror and the supernatural, later in life falling into the gentle rhythm of magical children’s tales.

Early Years

Blackwood was born, in 1869, in Shooters Hill, on the outskirts of London, England. His parents, wealthy and well connected, ensured their son was provided for, privately educated and they tried to inculcate him into their strict religious views. As is common amongst the well-to-do of the era Blackwood’s upbringing prepared him for precisely the opposite of his parents intentions; he gained the confidence and security of his background but rebelled against its strictures by exploring eastern philosophies and travelling extensively, trying half-heartedly to make his way in the world of work, without the motivations forced by the need for survival.

Blackwood was born, in 1869, in Shooters Hill, on the outskirts of London, England. His parents, wealthy and well connected, ensured their son was provided for, privately educated and they tried to inculcate him into their strict religious views. As is common amongst the well-to-do of the era Blackwood’s upbringing prepared him for precisely the opposite of his parents intentions; he gained the confidence and security of his background but rebelled against its strictures by exploring eastern philosophies and travelling extensively, trying half-heartedly to make his way in the world of work, without the motivations forced by the need for survival.

Toronto and New York.

He left Edinburgh University after only a year and he moved, at his parent’s bidding, to Canada to set up a dairy farm, and tried several other ventures before retiring, disillusioned, from everyday life and escaping periodically to revel in the interior landscapes of the vast Ontario forests. The morning mists, preternatural light, the comforting and terrifying sounds of nature forged a powerful effect on Blackwood, amplifying the insubordination of his schooling. Lonely fears of primeval darkness often form the backdrop of his stories, lending them a powerful, supernatural undercurrent.

Searching for work, and a purpose, he moved to New York in the early 1990s, eventually acquired a minor job as reporter on The Evening Sun where he found a primal terror of a very different kind: the corruption of humanity crushed within the tiny spaces of a modern city. A visceral lover of nature he hated the man-made degradation and, once again, found himself depressed and isolated.

Searching for work, and a purpose, he moved to New York in the early 1990s, eventually acquired a minor job as reporter on The Evening Sun where he found a primal terror of a very different kind: the corruption of humanity crushed within the tiny spaces of a modern city. A visceral lover of nature he hated the man-made degradation and, once again, found himself depressed and isolated.

He returned to England, apparently homesick, carrying with him a collection of haunting, supernatural stories that expressed his inner terrors. His friend Angus Hamilton sent some of these short tales, without Blackwood’s knowledge, to the London Publisher, Eveleigh Nash (who then had Arthur Conan Doyle and Robert Louis Stevenson in his stable). The result was the publication in 1906 of The Empty House and Other Ghosts Stories, establishing Blackwood as a writer of dark and subtle horror, with undertones of the mysticism that had sustained him in the dark, lonely woods of Ontario.

Main Works

Blackwood had been writing steadily during his years away from England, traverlling North America, but much of Europe too, and it seems he was able to turn the experiences into a series of effective fictions, finally becoming a full time writer in the first years of the new century.

The haunted house collection of The Listener, 1907, contained one of his most celebrated tales, The Willows, was swiftly followed by a slight change in emphasis, as he tapped into the contemporary obsession with detectives and crime solving cases. This was the era of readers who devoured Conan Doyles’ Sherlock Holmes and, only to slightly lesser extent, Arthur Machen‘s Carnacki stories which teased at the great social changes wrought by industrialization and explored mystical and supernatural themes. Blackwood, as a believer in the world’s beyond and a lifelong explorer of Eastern mysticism, wrote his own answer, John Silence: Physican Extraordinaire. It was a critical and popular success that would increase his confidence, and his ability to make a living from his writing.

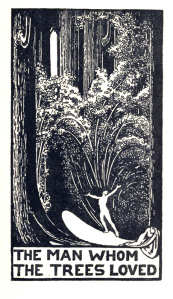

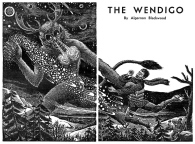

The Silence stories marked his move away from the haunted house tradition as he began to explore physic adventures. The books that followed were full of possession, souls in torment, reincarnation and visionary mystics: The Lost Valley and Other Stories (1910, including the celebrated Wendigo), Jimbo: a Fantasy (1909), The Education of Uncle Paul (1909), The Human Chord (1910), The Centaur (1911), Pan’s Garden (1912) and A Prisoner in Fairyland (1913). This latter book, was adapted first as a play (called Starlight Express), then a musical, with a score by Edward Elgar, the greatest English composer and cultural darling of the pre-War period.

The Silence stories marked his move away from the haunted house tradition as he began to explore physic adventures. The books that followed were full of possession, souls in torment, reincarnation and visionary mystics: The Lost Valley and Other Stories (1910, including the celebrated Wendigo), Jimbo: a Fantasy (1909), The Education of Uncle Paul (1909), The Human Chord (1910), The Centaur (1911), Pan’s Garden (1912) and A Prisoner in Fairyland (1913). This latter book, was adapted first as a play (called Starlight Express), then a musical, with a score by Edward Elgar, the greatest English composer and cultural darling of the pre-War period.

His writing was rudely interrupted by the First World War where he served in intelligence, in Switzerland. These harrowing years of intrigue and near-death provided more fuel for his narratives and he continued to write successful novels into the 1920s, just as the wave of modern horror and and science fiction began to flower in the era of the pulp magazines. 1921 saw publication both of The Bright Messenger, The Wolves of God and other Fey Stories.

In the twilight years of the pulps Blackwood’s earlier short stories were often republished in Weird Tales, and illustrated by Virgil Finally and Matt Fox but as his evocations of the natural world began to fall from public grace (overtaken by the fascination with other worlds and robots in early science fiction) his later work drifted into gentle children’s stories. His last decades brought him great popularity in the new medium of radio, then television. He was a graceful and charming storyteller with a heartening tone, perfect for broadcast: he was honoured with a CBE in 1949 for his public service.

In the twilight years of the pulps Blackwood’s earlier short stories were often republished in Weird Tales, and illustrated by Virgil Finally and Matt Fox but as his evocations of the natural world began to fall from public grace (overtaken by the fascination with other worlds and robots in early science fiction) his later work drifted into gentle children’s stories. His last decades brought him great popularity in the new medium of radio, then television. He was a graceful and charming storyteller with a heartening tone, perfect for broadcast: he was honoured with a CBE in 1949 for his public service.

Legacy and Connections

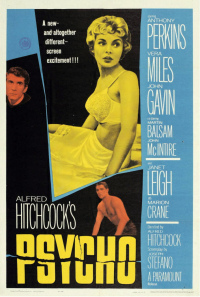

Blackwood lived an independent life. He didn’t marry, and he travelled extensively in his early to middle years, but it is the travel of his mind that seems to have been the most potent force of his storytelling. He explored many forms of mysticism, and his interest in eastern philosophies went far beyond the fashionable dalliances of his contemporaries. He was a true believer in the power and mystery of nature, of the cycle of life and the universe, and his fiction, rooted in the dark corners of the world, the forests and streams, the lonely houses and the shadows of the twilight, highlights the ancient terrors that lurk around every corner. His work influenced Arthur Machen, H. P. Lovecraft and Ramsey Campbell, as well as filmmakers with their own supernatural intimations, such as Guillermo del Toro, Alfred Hitchcock and Terry Gilliam.

Blackwood lived an independent life. He didn’t marry, and he travelled extensively in his early to middle years, but it is the travel of his mind that seems to have been the most potent force of his storytelling. He explored many forms of mysticism, and his interest in eastern philosophies went far beyond the fashionable dalliances of his contemporaries. He was a true believer in the power and mystery of nature, of the cycle of life and the universe, and his fiction, rooted in the dark corners of the world, the forests and streams, the lonely houses and the shadows of the twilight, highlights the ancient terrors that lurk around every corner. His work influenced Arthur Machen, H. P. Lovecraft and Ramsey Campbell, as well as filmmakers with their own supernatural intimations, such as Guillermo del Toro, Alfred Hitchcock and Terry Gilliam.

He died peaceful, in 1951, one of the great storytellers of the 20th Century.

Links

Other posts of interest include:

Robert Bloch: Master of Psychological Terror:

H. P. Lovecraft: From Weird to Modern Gothic

William Hope Hodgson: Master of Weird Fiction

Arthur Machen: Master of Supernatural Horror

William Blake: Artist and Revolutionary

Myths and Legends: Origins and Traditions

Filed under: Fiction, Only Connect Tagged: Arthur Machen, H. G. Wells, H.P. Lovecraft, Horror, Robert Bloch, Supernatural, Virgil Finlay, Weird Tales

May 22, 2014

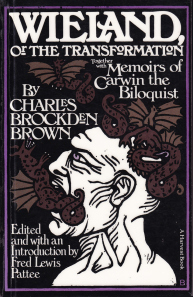

Charles Brockden Brown: First American Gothic

Born at the point of American Independence and living through the political revolutions and culturally romantic eras of Europe, Charles Brockden Brown was a man of his time. He revelled in the forces of independence, freedom and republicanism during America’s founding years, writing pamphlets, articles, letters and uniquely American gothic fiction. Hard work, economic progress and personal freedom were key drivers for the search of an early American identity and Brockden Brown’s work also reflects the adolescence of his country: arrogant and energetic, it was psychologically fragile with great fears lurking all around.

A Short Life

Born into a Quaker family in Philadelphia in 1771, just six years before the Declaration of Independence, Brown was one of six siblings. Physically weak, he died, in 1810 of the tuberculosis that had afflicted him throughout his life, but by all accounts he was an adventurous, strong-willed young man, industrious and considerate. He lived through a key turning point in history; Philadelphia was one of the largest cities in the world, an exciting melting pot of culture and politics and the site of all major Congress decisions in the newly independent country (the Declaration was signed there on July 4th 1776). During his life the new America broke its ties to colonial Europe with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, and wrestled with blockades, naval wars and treaties which served to firm the new America’s resolve to grow strong and economically independent in a complicated world.