David Boyle's Blog, page 45

November 6, 2014

The risks of investigating the banks now

It is both exhilarating and disturbing to find that the great edifice of government is moving in the directions you have urged. Not that I am in any way influential on these - the Treasury's inquiry into digital currencies and the new Competition and Markets Authority investigation into the banking market.

It is both exhilarating and disturbing to find that the great edifice of government is moving in the directions you have urged. Not that I am in any way influential on these - the Treasury's inquiry into digital currencies and the new Competition and Markets Authority investigation into the banking market.But it is still disturbing. Why are they doing it now? Will they actually make things worse?

It isn't clear to me, for example, that the Treasury has the authority it needs to regulate digital currencies, and I am always nervous when government departments start thinking about regulating areas which require innovation - they so often go about it in entirely the wrong way.

On the other hand, I would prefer UK banking regulators to have a go at setting out a framework for new kinds of money than any other European nation. Heaven help innovation if the Banque de France or the Bundesbank start throwing their Napoleonic weight about.

The Bank of England has already written something open-minded about the whole field. History demands that they take their responsibility to take charge of this on behalf of the continent. Or so it seems to me.

But I am confused about the government's decision to call in the banking market. I am not naive enough to believe that it had anything to do with my suggestion in this blog last month.

It is true that the banks require rescuing from themselves. The domestic banking market is no longer viable with free banking, partly because of low interest rates. None of them can afford to move first, but - if they collude among themselves to charge - they risk going to gaol. An investigation of this kind is precisely what they need.

In which case, why are they complaining?

The other question is this. The investigation is going to take 18 months, over the period of the next general election when the future of banking ought to be one of the main objects of debate. It is absolutely vital that we don't allow the parties to use this process to avoid discussing it with voters.

I very much hope that the Lib Dems will campaign on their new policy of banking with boots on the ground - and will act on it, alone or with others, after the election. Fingers crossed.

Published on November 06, 2014 03:21

November 5, 2014

We should nominate Elle for the Turner Prize

The mainstream arts world is a peculiar place. It struggles these days, not so much for beauty in the Ruskinian fashion, but for controversy - to frame a contradiction more sharply, to act it out, to see things more clearly.

The mainstream arts world is a peculiar place. It struggles these days, not so much for beauty in the Ruskinian fashion, but for controversy - to frame a contradiction more sharply, to act it out, to see things more clearly.It is true that most of what is produced, even for the Turner Prize, fails to rise this far. But then something comes along in real life that makes all their efforts redundant.

Can you imagine how a artist's career would have been made just by dreaming up and performing the bizarre dance of embarrassment by Elle, Whistles and the Fawcett Society over their sweat-shop T-shirt campaign. How everyone in search of popularity managed to be photographed putting one on, how they checked - of course they did - the so-called supply chain. But failed to pick up the phone to speak to someone in the actual factory.

I hope Elle and Whistles are pleased that they have inadvertently publicised the issue of sweatshops - but I expect they are still execrating each other behind closed doors.

What this whole mistake means, it seems to me, is that the gulf between trendy, branding campaigns and the real underlying economic issues is as wide as ever.

Yes, people can be photographed in a T-shirt, but they seem blind to the underlying economics - even a bit bored by it. As if it was somehow unavoidable. As if anything more than one-dimensional causes are really too much.

There encapsulated in this amazing installation is the central blindness of the modern world. It would be enough to win the Turner Prize. In fact, I'm going to see if I can nominate the Elle magazine and Whistles.

Published on November 05, 2014 07:06

November 3, 2014

Why governments take so long to act

I'm a little behind with my reading, what with moving house in the summer and the constant business of navigating the remaining cardboard boxes full of books. So it has taken until now for me to read the edition of Fortune magazine from last month about the progress of General Motors.

I'm a little behind with my reading, what with moving house in the summer and the constant business of navigating the remaining cardboard boxes full of books. So it has taken until now for me to read the edition of Fortune magazine from last month about the progress of General Motors.What I read was so fascinating and seems to me to shed light, not just on the strange business of the Home Office's failure to appoint anyone to head the historic abuse inquiry who can sustain the job for more than a few days, but the mysterious business of why governments mess up as often as they do. Maybe even a clue about crashes like Virgin Galactic (though Branson has denied that warnings were ignored, so maybe not).

It was the strange story of GM's recall scandal involving the failure of the airbags in the Chevrolet Cobalt. It was clear from April 2013 that the fault lay in the ignition system. Then - nothing. This is how the business writer Geoff Colvin put it:

"No order for an immediate recall, no report to high-level executives. Not even the general counsel was told. Instead ... 'the response to the revelation was to hire an expert'. It took six months for the expert to provide his written report, which merely concurred with what outsiders had been telling GM for years: that faulty ignition switches too easily turned from run to accessory mode, disabling the airbags.".

Even then, they didn't act. The engineer had to read and consider the report. Then he put his views to various committees. Finally, GM recalled the model in February this year. They had known exactly what the problem was for nine months - and 12 years after it was clear there was a problem.

GM's new CEO Mary Barra is using the disaster - which seems to have killed about 13 people - as a way to turn GM's exhausting culture on its head, not by forming another committee but by "behaving differently every day".

One of the problems about deciding urgently important things by networks of committees - in giant corporations or in Whitehall - is that people can avoid responsibility for the decisions. There are benefits too, but it makes change so exhausting that it happens extremely slowly - often beyond the point where it comes too late to make a difference.

Or, like constitutional reform, you wait and wait and then the committees disgorge some hastily contrived, seat-of-the-pants compromise. I heard the late lamented Joel Barnett on the radio today, to mark his death, complaining that the Barnett Formula which still governs the fiinancial settlement for Scotland and Wales was just one of these - something to satisfy some urgent crisis at the time. But decades ago.

So much decision making in government seems to be like that - government sometimes seems to be the sum total of every short-term sticking plaster ever cobbled together.

The bigger the organisation, of course - the more crass the management style - the worse these features tend to be.

So Mary Barra fascinates me. As head of HR at GM, she cut their ten-page dress code down to two words - 'dress appropriately'.

It is the high risk approach to simply fly in the face of this by the way you behave. I suspect that may be the only way to change a decision-making culture. But could any elected politician dare?

Published on November 03, 2014 23:46

November 2, 2014

Lib Dems, Greens must not hate/barbarians are at the gate

I was one of those young-ish activist types who took part in the extremely unofficial talks held between the Young Liberals, Liberal Ecology Group and the Green Party in the late 1980s to see if there was any basis for a re-merger.

I was one of those young-ish activist types who took part in the extremely unofficial talks held between the Young Liberals, Liberal Ecology Group and the Green Party in the late 1980s to see if there was any basis for a re-merger.In practice, what actually happened was that the Green Party abandoned the talks in response to their spectacular result in the 1989 Euro-elections, and - as it turned out - the Liberal Party merged with the SDP.

That probably was all for the best. We have gone our separate ways as parties in the last decade and a half. Everyone would agree that there are parts of the Green Party which are emphatically not liberal. There are certainly parts of the Lib Dems which are not green.

But back in 1987 (or was it 1988?) there was a strong measure of agreement. The main difference, as it was put to me by a prominent Green activist, was that the Liberals were more pragmatic - they compromise on the way to their objectives.

I noted this remark away rather cynically. Just wait until they run a city, I said to myself, and we'll see how long that attitude lasts.

What I didn't understand at the time was that this division (the realo/fundi division) was absolutely at the heart of Green politics, as much as the Tories are divided between free marketeers and xenophobes or between social and economic Liberals. The division has emerged over and over again, and disastrously, from the Hungarian Green Party to the Green ruling group on Brighton and Hove Borough Council.

All of this is a way of saying I don't agree with Caroline Lucas, the Green MP, when she dismissed the idea of any kind of electoral arrangements between the two parties, as proposed by St Ives MP Andrew George. Because there are ways in which Greens and Liberals represent missing wings of each other's philosophy.

I like and respect Caroline. She is a principled humanitarian, and she is quite right that we shouldn't waste time with any kind of formal electoral pact. But I'm not sure we have the luxury of happily bashing each other when a combined Ukip/Tory force may emerge to take down the wind farms and frack us all to kingdom come.

She is quite right, it seems to me, that the Lib Dems in office have compromised too much with nuclear subsidies (I believed Chris Huhne's 2010 promise "read my lips, no nuclear subsidies" and I was horribly wrong).

But she knows as well - not just that the Green Party originally emerged from the Liberal Party, but there are important parallels between us, and that there are Lib Dems who would oppose nuclear energy or shale gas extraction all the way, just as she would.

It makes sense, it seems to me, to work together if we can do so informally, to keep them in Parliament and keep her in Parliament, and bring in some colleagues too.

So yes, I would back informal arrangements, starting in Brighton. A Liberal UK needs people like Caroline Lucas and a Green UK needs people like Andrew George. The barbarians are now at the gate, and we may look back in a few years and wish we had acted together when we could.

Published on November 02, 2014 23:15

October 30, 2014

I am standing for the Lib Dem policy committee. This is why.

Why would you, after all? Nights crawling home on the late train. Sitting in interminable debate about the intricacies of social care till way into the dark. Queuing up for half an hour in the rain to get through the equally interminable parliamentary X-ray machines. I’ve done it before and I want to do it again.

Why would you, after all? Nights crawling home on the late train. Sitting in interminable debate about the intricacies of social care till way into the dark. Queuing up for half an hour in the rain to get through the equally interminable parliamentary X-ray machines. I’ve done it before and I want to do it again.Let me explain by describing the email I received from the party a few days ago asking me to respond to a simple question with a one-word answer: what is the issue that will be most important to you at the next election?

Come on, answer – quick, quick? What is it: health? The environment? Immigration?

The odd thing about this survey, and so many other similar surveys where the results were solemnly studied around the committee table in the past, is that it begs so many questions that it isn’t really worth asking.

Is there really any difference between health and the environment, for example? Does pretending there is misunderstand either issue in some people's minds?

If I say health, what would it mean? That I want the NHS to stay the same as it was in 1978? That I want it to undergo radical change to survive? That I want to privatise it? That I don’t want to privatise it? That I want more or fewer hospitals? That I believe resources should be shifted to prevention instead? That I believe air quality should be improved? That there should be more or fewer targets? Or not?

The answers to every one of these questions are somehow assumed? What does it mean that I think health is important – as I do? Has anybody wondered?

There is far better and more intricate polling being done by political parties these days, including in the Lib Dems. But this apparently simple, actually meaningless, survey betrays the old paint-by-numbers approach to policy – that all political platforms are kneejerk, that there is no new thinking, that it is all about positioning, and positioning from a point of view as free as possible from ideology or meaningful content.

I want to join the FPC (federal policy committee, for the uninitiated) because I don’t believe this. In fact, I don’t believe any political force which believes these boneheaded things can survive.

It is de rigueur to criticise party strategists when you are standing for an internal election, and I know this isn’t fair – they are actually increasingly sophisticated. But there is a fear, deep in the Lib Dems, of ideas. And I want to be at the table to put the opposite point of view as strongly as possible.

The world is about to change fundamentally, as I argued a few days ago. This is not the moment to assume that the existing systems, or the existing compromises, represent the only possible world.

It is particularly important when it comes to economics, the traditional blind spot among Liberals everywhere. The present dispensation is unravelling day by day. Everyone except mainstream economic policy makers understands that change is coming.

I am a Liberal. I believe in the potential of the party I joined in 1979 and the bundle of changing ideas they represent. If the party is going to survive as a potent force, it also has to represent an intellectual force, a force of coherent new ideas that allow us to navigate a safe way through the forces that threaten us.

That is especially so when it comes to inventing an economic dispensation that has some chance of spreading prosperity through the world, rather than hoovering up the available wealth like so many vampire squids.

If the Lib Dems become the cutting edge of policy thinking for the future, setting a bold course for change – and on people’s side, not compromising them for the sake of the survival of existing institutions and technocratic compromises – then the party will come back strongly in the years ahead, and just in time for the big shifts due around 2020.

That’s why I’m asking people to get me into a position where I have some chance of doing something about it. Fingers crossed...

Published on October 30, 2014 02:27

October 29, 2014

The strange re-emergence of virtual currencies

I used to consider myself an expert on the future of money. I realise I am not any more. Experts on the future of money have to include more IT geek about them than I will ever have, and this realisation follows finding this: a table of some of the market capitalisations of the most valuable 'virtual currencies'.

I used to consider myself an expert on the future of money. I realise I am not any more. Experts on the future of money have to include more IT geek about them than I will ever have, and this realisation follows finding this: a table of some of the market capitalisations of the most valuable 'virtual currencies'.The roller-coaster success of bitcoin has launched a flurry of activity, unfortunately somewhat similar activity - from darkcoin and feathercoin to litecoin and auroracoin. Many of them - and there are anything up to 500 of them - are created by rather shadowy figures, often with codenames, using the bitcoin 'blockchain' technology that allows the currencies to bypass the control of banks.

The best introduction I've seen is by my colleague Leander Bindewald, who explains that we are seeing the beginning of a new kind of currency platform about as different from the conventional banking way as it is possible to be - using transparency where the banks use secrecy.

We will see, but this is certainly an awkward step towards the multi-currency world I've been predicting for some time. But it isn't yet the diverse multi-currency world that I've been expecting.

But what I really find extraordinary about this is the way the financial world has been taken by surprise by it, because we have had parallel currencies of one kind of another since 1933.

I was staggered to see on Wikipedia that the term 'virtual currencies' "appears to have been coined in 2009".

This makes me feel more ancient than really I deserve. In 1999, a good ten years before that, I was commissioned by Financial Times Business Reports to write an expert study called Virtual Currencies.

I wrote it and it retailed at the shocking price of £495. It didn't sell terribly well, but then - as the dot.com boom collapsed around then - many of the virtual currencies I was talking about, flooz or beenz for example, were no more.

I put the concluding chapter online here not long ago, since it is now interesting primarily as a museum piece. It is pretty clear that I didn't envisage the explosion of bitcoin-style lookalikes - perhaps because of the demise of digicash not long before - and it included this paragraph:

"Do financial service companies have a unique role in the development of virtual currencies? Probably not, but they are in a good position to capitalise on them, because of the inherent trust which the industry can provide to new kinds of money..."

I'm not proud of this. I was right but for completely the wrong reason. In fact, the idea that financial service companies might lend trust to currencies is now completely laughable. Bitcoin and the other coins are testament to the opposite trend.

In fact, the financial services are so untrustworthy that people have been flocking to invest in a money system so anonymous that its creators are still unknown.

And if you read it, cut me a bit of slack. I wrote it 15 years ago.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe

Published on October 29, 2014 00:46

October 28, 2014

The world will change around 2020

Something is happening out there. A fascinating article in Der Spiegel (thanks, Joe) puts the issue pretty succinctly: the global economy is no longer working as it should - the banks are not lending, and the huge sums to be distributed by them simply shore up their balance sheets, the middle classes struggle increasingly to make ends meet - and the poor just struggle. While the handful of those at the top - less than one per cent actually - extract more and more.

Something is happening out there. A fascinating article in Der Spiegel (thanks, Joe) puts the issue pretty succinctly: the global economy is no longer working as it should - the banks are not lending, and the huge sums to be distributed by them simply shore up their balance sheets, the middle classes struggle increasingly to make ends meet - and the poor just struggle. While the handful of those at the top - less than one per cent actually - extract more and more.It is the Piketty thesis and it is accepted increasingly in every area of modern life, except among national policy-makers. The idea that the institutions of modern capitalism have become extractive - as institutions have done occasionally in history, with disastrous results - is becoming increasingly accepted. The problem is that there are few agreed solutions, even tentative ones. Certainly not from Piketty.

This is how Michael Sauga puts it in the article, describing the economist Daron Acemoglu:

He became famous two years ago when he and colleague James Robinson published a deeply researched study on the rise of Western industrial societies. Their central thesis was that the key to their success was not climate or religion, but the development of social institutions that included as many citizens as possible: a market economy that encourages progress and entrepreneurship, and a parliamentary democracy that serves to balance interests....

Extremely well read, Acemoglu can cite dozens of such cases. One is 14th century Venice, where a small patrician caste monopolized maritime trade. Another is Egypt under former President Hosni Mubarak, whose officer friends divided up key economic posts among themselves but were complete failures as businessmen. These are what Acemoglu calls 'extractive processes', which lead to economic and social decline. The question today is: Are Western industrial societies currently undergoing a similar process of extraction?

The parallel I draw in my book Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis is with Spain at the height of its imperial power, where the gold poured in, the ability to manufacture withered away and inflation finally overtook the empire.

It may be that deflation is the demon that will do for us. It does look increasingly as though the struggling big banks will go through another period of instability, as the big economies begin to struggle again A new settlement is required - and one that can include people again - and, history has a habit of providing these things once the situation is really desperate.

What is more, those moments of reboot seem to happen pretty regularly every 40 years or so. The last one was in 1979/80. The one before was the rapid political and economic shift in the UK and USA in 1940/41. Before that, it was the new settlement ushered in by the People's Budget of 1909 and Teddy Roosevelt's busting of Standard Oil, which ended finally in 1911. The big political shift before that came in the mid-1860s.

We are not quite overdue for a major reboot, but it is coming and - by my 40-year pattern - it should emerge around 2020. We don't know how it will happen, or what constipated failure to tackle the underlying forces at work will provoke it, but we can be pretty clear already the kind of shape it will be.

And here the Der Spiegel article reaches a parallel conclusion, quoting Acemoglu again:

What is needed, he argues, is a new political alliance that takes a stand against the power of the financial industry and its lobby. He sees the anti-trust movement from the beginning of the last century in the United States as a model. It was a broad coalition from the center of society and finally achieved its great victory after decades of struggle: the breakup of major corporations like Standard Oil.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on October 28, 2014 00:44

October 27, 2014

Lidl, Tesco and the need to control us all

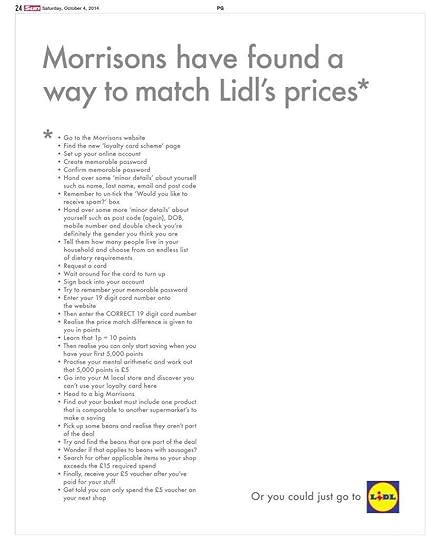

I've never felt much kinship with Lidl. The bare, rather unfriendly aisles, the functional and inadequate space for paying, never gives me much comfort to be there. It feels somewhat alien, even now. But I warmed to them when I saw their advert giving Morrisons a good kicking.

I've never felt much kinship with Lidl. The bare, rather unfriendly aisles, the functional and inadequate space for paying, never gives me much comfort to be there. It feels somewhat alien, even now. But I warmed to them when I saw their advert giving Morrisons a good kicking.You can read it here. It explains the palaver of getting a Morrisons loyalty card, fiddling around with passwords, remembering what food items qualify for the system of loyalty points. As they say at the end: 'Or you could just go to Lidl'.

It must have enraged Morrisons, and so it should do.

The advert makes things horribly clear to me, especially since Tesco now seems to be on a terminal slide to takeover.

The first was that, if we had the sense to realise it, a 2005 survey by The Grocer - which I now can't find a copy of - should have given us a clue about what was about to happen. It found that, of all the major retailers, Tesco was the bottom of the list for enjoying shopping there.

Waitrose came top. I remember thinking at the time that the survey had identified something important. It was simply unpleasant shopping in Tesco, from the badly designed aisles to the security guard peering at you. What I didn't realise at the time was that there would come a time when this would be count. When people understood that, actually, Tesco wasn't really cheap after all - even the street markets in London were cheaper at the time - then the fact that it was no fun to shop there would suddenly matter very much.

There was a kind of sneering atmosphere about the place - a bit like Ryanair - a smug, knowing attitude that people simply had to shop there because it was so cheap. There was a whiff of contemptuous monopoly about it. And the result now is all too obvious.

But Lidl's advert makes me realise how far that contempt has spread through the biggest organisations we deal with, public and private. You read through the list of Morrison's instructions, padded out somewhat by the copywriters, and realise that the most important aspect of the way we are treated these days, by those who rule us, sell to us, supply us with energy or anything else, is control.

Tesco thought they controlled us. The other utlities, banks, public services and superstores, have designed customer service systems primarily with control in mind. They are designed to make us easier to process.

And then we wonder why people seem so angry that they are apparently prepared to vote for a party led by a man who used to sing Hitler Youth songs at school (sorry, the story was 'exaggerated', I gather).

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on October 27, 2014 08:51

October 24, 2014

Is the NHS pulling in opposite directions?

Years ago, I remember sitting in the Lib Dem policy committee talking about I meant to call 'preventative health', but which I accidentally kept on referring to as 'health prevention'.

Half-way through, Conrad Russell - the much-missed Earl Russell - tapped me on the shoulder, indicated his packet of cigarettes, and said: "I'm just popping outside for a bit of health prevention".

All of which is a way to say that prevention as the key to the future of the NHS is hardly new.

Even so could you imagine anyone coming out with a report on the future of the NHS which is clear about the problems, honest about the solutions, minces no words and gets the overwhelming endorsement of absolutely everyone? Because that is what Simon Stevens has managed in his Five Year Forward View, published yesterday.

That is a huge achievement in itself. It is a bold approach to prevention and local control that everyone appears to be embracing. It only has a paragraph on what I would call co-production, but Stevens evidently gets it.

Three things occur to me.

The first is kind of partisan: the combination of prevention, flexibility and integration is precisely what the Lib Dems set out - though in slightly different terms - in their new public services programme debated in Glasgow.

I'm not sure what it means when the NHS chief executive comes up with the same themes a few weeks later. It may mean the Lib Dems were right; it may also mean that they didn't go far enough.

The second is that prevention requires a little more thought. The New Labour approach to prevention patently didn't work - advertising and professional exhortation to us to drink and eat a little better. Part of the problem is that effective prevention policies can't be pursued by the NHS alone - because they involve food policy, employment policy and much else besides. Stevens hints at this but it requires very high level backing indeed. As he says, it needs to be a national 'movement'.

It also implies a serious shift in funding away from hospitals. Which is when the trouble starts.

The third is that this report seems to me to mark the end of conventional competition in the NHS. There will still be a market, and a commissioner-provider split. There will still be choice - but there is no way that Monitor, for example, can preside over the kind of integrated care that is set out here and regulate it as a market in the way that Andrew Lansley originally intended.

In fact, I find what passes for a debate about the NHS at the moment really rather peculiar. Partly because the left seems to forget that the original turbo-competitive version of the Health and Social Care Act wasn't actually passed. Partly because the Department of Health seems to be going in two directions at once - on the one hand towards more formal competition, on the other hand towards more integration.

The two can live alongside each other up to a point, but only just. One of them must be compromised, and the idea that the NHS is being 'sold off' in some way - which we hear constantly from commentators - is not quite accurate. Something else is going on as well.

Yes, there is a great deal of private investment and private sector provision, though far too few social enterprises and mutuals being commissioned. The narrowing of contract culture is having a serious effect - the real problem here, it seems to me. Yet at the same time, this report is evidence that there is another direction entirely being planned - integrated primary care, integration between the NHS and social care.

How does this live with more competition? I don't know but I think we should be told.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe

Published on October 24, 2014 02:29

October 23, 2014

Plunging ourselves into delusory data

The principle that numerical measurements will always be inaccurate if they are used to control is now known as Goodhart's Law.

The principle that numerical measurements will always be inaccurate if they are used to control is now known as Goodhart's Law.The law was formulated by Charles Goodhart to shed light on macro-economic policy, but it mainly now informs - or, more accurately, fails to inform public services.

The point is that, however incompetent staff may be, they will always be skilful enough to make targets work for them rather than against them. Take for example, the rule that patients shouldn’t be kept on hospital trolleys for more than four hours. It was early in the targets story that hospitals got round this by putting them in chairs. Others bought more expensive kinds of trolleys and re-designated them as ‘mobile beds’.

In similar ways, we transformed services into a huge industry dedicated primarily to making the output numbers seem as if they are rising. This is achieved sometimes despite the job they are supposed to do, and often instead of it. See more in my book The Human Element.

But it is the inaccurate measurements that concern me here. And this is where the staggering naivety of management consultants seems to cause so much trouble - and I've been thinking about this in relation to the idea that GPs should be paid £50 for diagnosing dementia.

There are no effective treatments for dementia now, so the only possible justification for this idea is that it will provide more accurate data about how many people have this problem. That is pretty much the conclusion of Ann Robinson's article in the Guardian. But by creating a situation where doctors are tempted to fall over themselves to diagnose dementia, as a way of plugging the growing hole in their cashflow, the last thing we will have is accurate data.

Data is the new icon. We worship it. The prime minister sits demanding graphs, imagining they can make visible the tiny changes around the nation. We assume that, once we have the data, no further action is necessary.

But what the new utilitarians forget is just how inaccurate this data is - and especially when we give such an incentive to game it.

The same is increasingly true of financial data, gamed from inside the banks or the dark pool traders. We are awash in a sea of inaccurate data - no problem there except that we appear at the same time to be losing our scepticism about it and loading it into the machines which manage the nation.

Published on October 23, 2014 08:12

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.