David Boyle's Blog, page 47

October 6, 2014

The transformative force of civilising women

I am in Glasgow, theoretically to hand over my crown as Lib Dem blogger of the year last year to this year's winner: the granddaddy of the Lib Dem bloggers, Jonathan Calder. Unfortunately, being habitually late for everything, I missed the awards - but it is still much deserved and I wish I'd been there.

I also came here, partly, to speak in the debate on public services. I have blogged in similar style about public service flexibility, and how it goes beyond narrow choice, many times before and I won't try anyone's patience by repeating it now.

The debate was two and a half hours long and, as I watched and listened, I realised that the party was about to change in a far-reaching way that I hadn't realised before.

Time after time, I found myself watching, highly effective, articulate and powerful women future candidates for parliamentary seats which the party either holds or could hold.

There was Helen Flynn (Harrogate), Jane Dodds (Montgomeryshire), Layla Moran (Oxford W), Kelly Marie Blundell (Guildford), Vikki Slade (Mid Dorset), Julie Porksen (Berwick), and of course Julia Goldsworthy (Camborne) who introduced the debate. I could go on (these are just the ones who spoke in that debate).

If the party wins these seats, and they certainly could - they have all been Lib Dem seats within the past decade - it will transform an overwhelmingly male parliamentary party into something else.

Very quietly, and without a great deal of agonising about it in public, the party has gone about choosing women for many of their most winnable seats.

There are a number of cliches about the presence of women in politics which I don't entirely buy. I tell myself that there is nothing intrinsically different about women once they are in Westminster. The system takes over. But there is another part of me that doesn't quite buy this either.

If these women are elected - the generation born in the 1970s and 80s - they will be a hugely impressive, articulate and civilising intake. I don't know what they will do to the country, but they will transform the Lib Dems.

I also came here, partly, to speak in the debate on public services. I have blogged in similar style about public service flexibility, and how it goes beyond narrow choice, many times before and I won't try anyone's patience by repeating it now.

The debate was two and a half hours long and, as I watched and listened, I realised that the party was about to change in a far-reaching way that I hadn't realised before.

Time after time, I found myself watching, highly effective, articulate and powerful women future candidates for parliamentary seats which the party either holds or could hold.

There was Helen Flynn (Harrogate), Jane Dodds (Montgomeryshire), Layla Moran (Oxford W), Kelly Marie Blundell (Guildford), Vikki Slade (Mid Dorset), Julie Porksen (Berwick), and of course Julia Goldsworthy (Camborne) who introduced the debate. I could go on (these are just the ones who spoke in that debate).

If the party wins these seats, and they certainly could - they have all been Lib Dem seats within the past decade - it will transform an overwhelmingly male parliamentary party into something else.

Very quietly, and without a great deal of agonising about it in public, the party has gone about choosing women for many of their most winnable seats.

There are a number of cliches about the presence of women in politics which I don't entirely buy. I tell myself that there is nothing intrinsically different about women once they are in Westminster. The system takes over. But there is another part of me that doesn't quite buy this either.

If these women are elected - the generation born in the 1970s and 80s - they will be a hugely impressive, articulate and civilising intake. I don't know what they will do to the country, but they will transform the Lib Dems.

Published on October 06, 2014 16:26

October 2, 2014

The re-alignment of the Right

The phrase 'Re-alignment of the Left' began with Jo Grimond in 1956. It happened briefly when the SDP split away from the Labour Party in 1981, but the Left then contrived to align itself back into its old dysfunctional shape.

The phrase 'Re-alignment of the Left' began with Jo Grimond in 1956. It happened briefly when the SDP split away from the Labour Party in 1981, but the Left then contrived to align itself back into its old dysfunctional shape. For some reason, you almost never hear the phrase 'Re-alignment of the Right'. Yet, listening to David Cameron's speech yesterday, with the ghost of Ukip peering over his shoulder, convinced me that that may be what is happening.

The Conservative Party is an uneasy alliance between two elements which have little in common - the old-fashioned conservatism of family and community, and the new conservatism of markets and big business. Sometimes a broad Cameronian rhetoric of moderation can hold the two sides together; sometimes it can't.

The last time they came apart spectacularly was during the early years of the last century - half of them backing protectionism and 'imperial preference' and the other half a kind of liberal commitment to trade, with a rump around prime minister Balfour where they had, as one of them put it, "nailed my colours firmly to the fence".

The Ukip insurgency seems to be uniting one kind of conservatism - suspicious of foreigners - from across the parties, against the other kind. Business lobby groups are in despair. Something is about to shift.

So when former Cambridge MP David Howarth argued in the latest Liberator (not online) that there is no constituency for Jeremy Browne's vision of a new kind of free market Liberalism, there is a 'yes, but...'

Because the long-term prospect is to re-align the Right so that the old curmudgeons in Ukip take over the rump of the old Conservative Party, and the modernisers, moderates, small enterprisers and open traders join the Lib Dems.

There is a 'yes, but' here too. Because it provides an opportunity for Liberals to claw back the original meaning of 'free trade' from the conservatives and advocates of turbo-capitalism.

Free trade as it was originally understood, developed by liberals for Liberals, was the right of free people to trade with each other, communicate with each other and be hospitable to each other. It emerged out of the anti-slavery movement as the antidote to the kind of economic bondage which faced former slaves in the Deep South or former serfs in Russia.

It was not what it has become: an assertion of the right of the powerful to ride roughshod over the powerless.

It was originally an antidote for monopoly; it has become a justification of it. In the Re-alignment of the Right, if Liberals embrace it - and make the intellectual running - that has to change.

It is a historic opportunity for Liberalism to take back control of a concept which they invented. I'm rather looking forward to it, especially if we can re-align the Left at the same time.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe

Published on October 02, 2014 02:17

October 1, 2014

Two expensive paradoxes of the politics of the NHS

Let's call it the Westminster Paradox, shall we? I can't believe it has always been true, but it is definitely true now.

Let's call it the Westminster Paradox, shall we? I can't believe it has always been true, but it is definitely true now.It is this. Westminster politicians constrain themselves in a whole range of ways in their understanding of what they can change - they are constrained by international trade treaties and treaty obligations, by a creaking economic belief in 'trickle down', and the overwhelming need to carry on with the economic consensus of the 1990s. It sometimes seems as if they dare change very little.

On the other hand, get them on a conference platform, get them talking about the NHS and they sound staggeringly and unrealistically powerful - 'grandiose', the psychologists would call it.

Ed Miliband promises the finance for another 30,000 more NHS staff, unaware perhaps that the finance is the least of the difficulties here - you can't just conjure up 30,000 professionals in a year or so. Are they in training? Are they already trained and wanting to hear his bugle call? Or will his people go out to the developing countries and offer enough money to their newly trained professionals and ship them over?

David Cameron promises seven-day-a-week GP surgeries, at the same time as his Chancellor promises continued austerity - at a time when primary care is shuddering under the impact of extra costs passed on by private NHS contractors and the peculiar by-product of contract and target culture and payment-by-results. Where will these new GP surgeries emerge from? Where will the extra doctors come from? Are they in training?

The answer is that they are not, at least on that scale.

But then Cameron has realised - as we all have - that the issue of getting an appointment with your doctor is going to be one of those key election issues that can sink a sitting government.

It has a symbolic value for middle England, despite the fact that - in practice - many of the most imaginative practices have managed to find solutions.

In the Blair years, this would have been solved with a vacuous piece of sticking plaster - a 48 hour target, which gave people the right to see a GP in two days if they needed to. Targets always have perverse ways of making the situation worse and this one did so especially - soon you could only get an appointment within 48 hours, no earlier and no later, and practices hoarded their appointments in the most bizarre and irritating ways.

But we have a different kind of target these days, called something else. Also, there is no doubt that surgeries need to expand their horizons, and to take back responsibility for the disastrous out-of-hours care, which was taken away from them in the equally disastrous pay agreement under the Blair government in 2004.

But then, where is the money to come from? Contracting out the out-of-hours service has been so disastrous that handing it back to GPs would cost a small fortune, just in increased insurance costs.

We also need to know rather better whether demand is actually rising in primary care and why. My own sense is that this is, at least partly, the result of target and contract culture.

This has tended to go hand in hand with contracting out to the private sector, but it actually has no necessary connection. The problem isn't which sector delivers healthcare, it is what happens inevitably if you try to define the numerical outcomes which a contractor is responsible for delivering, and to squeeze the cost at the same time.

By chopping deliverables up into figures that are easy to measure and report on, all the rest gets lost - and the resulting costs land on the NHS as a whole. Staff find themselves under pressure to minimise their broad efforts, except where it relates to crossing the numerical thresholds.

See my book The Tyranny of Numbers about the perils of too much measurement.

None of this would matter if you could actually measure the full range and depth of what a good health professional does, but you can't. Anecdotal evidence suggests that doctors who build a relationship with patients deal better with risk - the patients need less reassurance and the doctors commission fewer tests.

Actually, nobody as far as I'm aware has tested this hypothesis - mainly, I suppose, because it flies in the face of current assumptions.

So there's another paradox. The more you focus on narrow costs and numerical deliverables, the more costs go up.

Published on October 01, 2014 04:12

September 30, 2014

The strange re-appearance of John Ruskin

The famous Gold Rush in California in the 1850s was a bitterly disappointing and brutalising experience for many of those taking part. But for a few, it meant a fortune.

The famous Gold Rush in California in the 1850s was a bitterly disappointing and brutalising experience for many of those taking part. But for a few, it meant a fortune.One of those, carrying his gold home with him on a ship that foundered in the Pacific, became the subject of a cautionary tale by the great Victorian critic John Ruskin a few years later.

He described how the passenger, who was carrying 200 pounds of gold with him, was loathe to abandon his hard-won wealth when the ship disappeared beneath the waves. He therefore strapped as much as he could to himself, and jumped over the side. Once in the sea, the gold dragged him down to the bottom.

“Now, as he was sinking,” asked Ruskin rhetorically, “had he [got] the gold, or had the gold [got] him?”

This neat story, written in the style of a morality tale told by preachers, could have been no more than a short homily about laying up treasure in heaven. But for Ruskin, it was an economic parable as much as a spiritual one.

He put it at the heart of his controversial 1860 essay series on economics in the Pall Mall Gazette, commissioned by the editor, novelist William Makepeace Thackeray. Ruskin launched this polemic with an attack on the people who were supposed to be experts – and in this case, the economists who believed that scarcity was the basic existence of humanity.

No, says Ruskin to Malthus and Ricardo:

"The real science of political economy, which has yet to be distinguished from the bastard science, as medicine from witchcraft, and astronomy from astrology, is that which teaches nations to desire and labour for the things that lead to life: and which teaches them to scorn and destroy the things that lead to destruction.”

The essays, and this distinction – between wealth and what he called ‘illth’ - caused such controversy that Ruskin was never invited to write about economics again. But when they were published as Unto This Last, it had the most enormous influence on the next two generations.

Gandhi read it from cover to cover on his journey to from London to South Africa and it inspired his political struggle. Schumacher was inspired by its principles to develop his concept of Buddhist economics.

That tradition – economics as if people mattered; economics that recognises that money can also be a hindrance, and that the economic system is creating poverty – is the basis of an emerging new, rather broader understanding of economics. You can read more about it in my book The New Economics: A Bigger Picture.

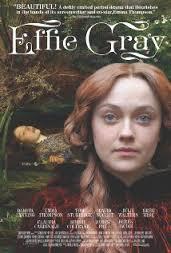

Why am I talking about Ruskin now? Because the spirit of Ruskin hovers over us this autumn with the release of two Victorian films – Emma Thompson in Effie Gray (with Greg Wise as John Ruskin) and Timothy Spall in Mr Turner (with Joshua McGuire as John Ruskin).

Effie Gray, the name of Ruskin’s wife in his disastrous marriage, has been held up for some years by legal actions which have now been resolved. Turner was Ruskin’s hero, the man who was the star of his influential book Modern Painters, and the spirit of whom he arguably translated into economic terms in Unto This Last.

The story of Effie Gray’s affair and marriage to Millais brings no great credit to Ruskin, but it is no coincidence that both these films are emerging at the same time: Ruskin’s approach to economics was a blistering critique of the Victorian age, and its commitment to ugliness, and it is an equally blistering critique of our own age - also rather committed to ugliness, for anyone who can't afford otherwise.

I haven’t seen either film, though I’m going to. And I know they won't really be comfortable viewing for those of us who admire Ruskin. But his spirit has a habit of re-emerging at times like our own, and these films seem to me to be some evidence of a return.

And that much, I'm glad about - because we need a spark of Ruskinian radicalism now more than ever before.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe

Published on September 30, 2014 02:16

September 29, 2014

The roots of Ukip, the roots of the SDP

[image error]

I have just moved house, an unexpectedly stressful business which involves a good deal more wandering around with a screwdriver than I had intended.

There I was pulling apart the crumbling casing for some hot water pipes, and what should I find - a copy of the Daily Mirror from 30 January 1981. Inside was a fascinating editorial castigating a poll in the Sun. This is what it said:

"Forty-three per cent of voters with a telephone would vote for a centre party which doesn't exist - and isn't likely to.... The Mail said a centre party would get 30 per cent of the vote, but 40 per cent if the Liberals were in it. "

There was then an obscure discussion about the support that David Steel would get if he was leader, trumped by Shirley Williams if it was her. But then, as we all know, later that same year, the Mirror had to eat their words: the SDP was indeed launched, and shot up in the opinion polls for a couple of exciting and rather stressful years - I speak as a twentysomething Liberal activist at the time.

But it set me thinking about the need people have in every age for a new political pretender, on whom they might project their greatest hopes.

So have people really swung to the right in the three and a half decades since then? From the enthusiastic endorsement of a centre party with the European Union in its DNA to a right wing party which looks very different (though I don't think Ukip will ever manage 30 per cent in the polls).

I doubt it. What that editorial reminded me is how much people long for political outsiders who might speak for them against the establishment. It doesn't really matter if it is Ukip or an SDP which didn't yet exist. They will gather support.

I'm not arguing that they will inevitably fade away. The SDP came back in the form of Blair and inherited the world, after all. Ukip could pull off a similar trick with the Conservative Party. They are parallel phenomena.

There are other parallels between then and now. Back in 1981, people felt a sense that their government was powerless to help them - inflation was at nearly 12 per cent, UK industry was closing its door thanks to the high pound, the unemployed were marching from Jarrow again and riots were about to tear apart the inner cities.

These days, the economic situation is a whole lot better, but there is a doubt - it seems to me - whether the establishment wants to support the people of the nation. I'm not talking about welfare here. I'm talking about the sense that even the middle classes have that the establishment is somehow governing on behalf of someone else altogether.

The trickle down effect which so motivated the government in 1981, and which so manifestly failed to trickle, has become such a doctrine of faith that the mainstream political world seems not to have noticed that, actually, it doesn't trickle down - it hoovers up!

So when I heard that another Conservative MP has thrown in his lot with Ukip, it partly reminded me of 1981 when the same thing was happening to the Labour Party - and it partly reminded me of what drives the rage behind Ukip.

It is the same phenomenon that drove the independence vote in Scotland. It is people's sense that their own politicians are not on their side - that they have become so stuck in the fantasy of trickle down that they appear to be governing entirely on behalf of a global elite. Smoothing the way for their luxury high rise flats, their cheap labour, their monopolistic ambitions.

This is not going to last, because it can't - it throws up ugly, intolerant politics. It provides no answers. Something is going to shift, and my guess it will do so in the next parliament - but we are going to go through a rough period before we get there, and there is a lot of thinking to be done in the meantime.

There I was pulling apart the crumbling casing for some hot water pipes, and what should I find - a copy of the Daily Mirror from 30 January 1981. Inside was a fascinating editorial castigating a poll in the Sun. This is what it said:

"Forty-three per cent of voters with a telephone would vote for a centre party which doesn't exist - and isn't likely to.... The Mail said a centre party would get 30 per cent of the vote, but 40 per cent if the Liberals were in it. "

There was then an obscure discussion about the support that David Steel would get if he was leader, trumped by Shirley Williams if it was her. But then, as we all know, later that same year, the Mirror had to eat their words: the SDP was indeed launched, and shot up in the opinion polls for a couple of exciting and rather stressful years - I speak as a twentysomething Liberal activist at the time.

But it set me thinking about the need people have in every age for a new political pretender, on whom they might project their greatest hopes.

So have people really swung to the right in the three and a half decades since then? From the enthusiastic endorsement of a centre party with the European Union in its DNA to a right wing party which looks very different (though I don't think Ukip will ever manage 30 per cent in the polls).

I doubt it. What that editorial reminded me is how much people long for political outsiders who might speak for them against the establishment. It doesn't really matter if it is Ukip or an SDP which didn't yet exist. They will gather support.

I'm not arguing that they will inevitably fade away. The SDP came back in the form of Blair and inherited the world, after all. Ukip could pull off a similar trick with the Conservative Party. They are parallel phenomena.

There are other parallels between then and now. Back in 1981, people felt a sense that their government was powerless to help them - inflation was at nearly 12 per cent, UK industry was closing its door thanks to the high pound, the unemployed were marching from Jarrow again and riots were about to tear apart the inner cities.

These days, the economic situation is a whole lot better, but there is a doubt - it seems to me - whether the establishment wants to support the people of the nation. I'm not talking about welfare here. I'm talking about the sense that even the middle classes have that the establishment is somehow governing on behalf of someone else altogether.

The trickle down effect which so motivated the government in 1981, and which so manifestly failed to trickle, has become such a doctrine of faith that the mainstream political world seems not to have noticed that, actually, it doesn't trickle down - it hoovers up!

So when I heard that another Conservative MP has thrown in his lot with Ukip, it partly reminded me of 1981 when the same thing was happening to the Labour Party - and it partly reminded me of what drives the rage behind Ukip.

It is the same phenomenon that drove the independence vote in Scotland. It is people's sense that their own politicians are not on their side - that they have become so stuck in the fantasy of trickle down that they appear to be governing entirely on behalf of a global elite. Smoothing the way for their luxury high rise flats, their cheap labour, their monopolistic ambitions.

This is not going to last, because it can't - it throws up ugly, intolerant politics. It provides no answers. Something is going to shift, and my guess it will do so in the next parliament - but we are going to go through a rough period before we get there, and there is a lot of thinking to be done in the meantime.

Published on September 29, 2014 01:59

September 26, 2014

The unexpected paradox of school choice

This is the time of year for the collective meltdown of the middle classes, and anyone else concerned to choose the right secondary school for their child. See my book Broke to explain how we got here.

This is the time of year for the collective meltdown of the middle classes, and anyone else concerned to choose the right secondary school for their child. See my book Broke to explain how we got here.The system which has the shorthand word ‘choice’ attached is, more accurately, the right to express a preference and it works relatively well in some areas. In London, where just over 60 per cent go to the secondary school they want to, it has become a source of insanity and panic.

I became fascinated with this phenomenon when I was writing the Barriers to Choice review for the Cabinet Office in 2012-13. The hard fact is that, although the system works in some places – probably even most places – it has precisely the opposite effect that it should in London and elsewhere.

It is billed as ‘choice’ but in these places it is nothing of the kind, given that the schools and the local authorities are doing the choosing. That leads to a range of the most egregious abuses – terrifying house prices around good schools, tutoring from the age of four and all the rest.

It is a major factor in my own decision to leave London, and a recent visit back to my old neighbourhood revealed the meltdown in full flow.

“I know what my child needs,” said one parent I know, through gritted teeth. “It is just that he can’t have it.”

That sums up succinctly my own conclusions on the subject. Where there are enough local schools, and there is some diversity between them, the system can work well. Where there is a shortage of places or all the schools are identical, then you have serious difficulties.

Combine that with areas of high population growth and high deprivation, as you get in London’s East End, and you get the seeds of what could become a serious source of injustice.

This leads me to support the idea of free schools, because that is the way you inject diversity into the system. But clearly it isn’t the only solution.

The basic problem lies in the way school choice was designed, by a group of economists at 10 Downing Street during the Blair and Brown years. Like many economists, they seemed to have believed there were approved ways of making our choice – on results, as mediated in the approved way through league tables.

In fact, once you talk to parents – or interrogate yourself – you find that what many parents want from schools is something much broader and diverse. Will their child be happy there? Will they make friends or be bullied? What is the staff turnover? Will they be allowed the flexibility to study what they want? Will they be encouraged to be what they want?

None of these were on the approved list of the economists behind public service choice, or on the league tables or websites. Nor do they undermine the idea of choice – they support it. If only they could get one.

But there is a fascinating twist to this story. I went to the open day of our local secondary school last night, and it was very impressive. It certainly impressed my ten-year-old.

The headteacher didn’t exactly pour scorn on Ofsted, and he mentioned the word ‘outstanding’ whenever he could. But equally he claimed not to be very interested in their structures or standards.

True to his word, the word ‘results’ didn’t pass his lips – perhaps he assumes we already knew them – and he said what his audience really wanted to hear: that he believed our children “would be safe, happy and make friends there”.

“I believe that, when children are safe and happy, then there are opportunities for learning,” he said. Happiness came first – not a word from the lectionary of approved choice.

This is interesting because it is, in some ways, a vindication of school competition, in precisely the opposite way that the doyens of service choice intended.

He was appealing over the heads of the regulators to what he knows parents really want, drawing on our scepticism about the league tables and Ofsted inspections, with their computerised reports.

The hall was packed with salivating parents and excited children. It worked. I don’t believe it worked in the way that Ofsted intended.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the wordblogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on September 26, 2014 03:00

September 24, 2014

Ed Miliband and wheeze-itis

The very first party conference I ever attended was the 1982 Liberal Assembly in Bournemouth. There, squeezed into a crowded and sweaty room, I heard Adrian Slade's brilliant performance as Roy Jenkins, in front of the very uncomfortable man himself.

The very first party conference I ever attended was the 1982 Liberal Assembly in Bournemouth. There, squeezed into a crowded and sweaty room, I heard Adrian Slade's brilliant performance as Roy Jenkins, in front of the very uncomfortable man himself.I believe Jenkins later described the experience as the least comfortable moment of the Alliance years. Hard to believe that, actually.

Among Slade-as-Jenkins' best lines was the phrase "our great crusade to change everything - just a little bit".

I was reminded of that today on two occasions. The first was reading an absolutely beautifully written and elegantly argued pamphlet by Giles Wiles and Stian Westlake, proposing a break-up of the Treasury. The pamphlet is published by Nesta and includes this description of the Treasury's role in what they call government 'wheeze-itis':

"The power of Treasury spending teams, combined with the short-term nature of Budgets and Autumn Statements encourages a tendency towards policy wheezes, where a long-term approach to policy-making would generally be more productive."

I entirely agree with that. It is paradoxical that the high-minded Treasury should be the cause of such short-termism, but that is one of the side-effects of centralisation, as the report The End of the Treasury argues so convincingly.

Then along came the evening paper with the lead story about Ed Miliband's speech. A hypothecated tax on 'mansions' to pay for more than 30,000 new NHS staff. There was something desperately depressing about this, and I believe the clue to why lies in Miliband's Jenkins-esque campaign to change everything, just a little bit.

It wasn't that any of these objectives were mistaken, but of all the big ideas he might have come up with, this one has a staggering inability to leave the key problems we face unscathed.

Will it tackle the imbalance of regional finances (no, the focus on property tax which shifts so much economic power to London will remain)?

Will it tackle the property bubble? (maybe on homes above £2m, but otherwise no)?

Will it tackle the structural difficulties in the NHS, its focus on pharmacalogical treatment rather than prevention, its obsession with one-off interventions rather than tackling chronic ill-health (no)?

It will, in short, leave most of our difficulties exactly the same, but it's a good soundbite.

It reminds me horribly that the UK system of government is the sum total of all the last generation's wheezes and quick fixes - with the possible exception of public services, which are regularly dug up by the roots to make sure they are still alive.

I remember sitting across the table in Whitehall in the early years of the Blair government and being told by a senior official that what they wanted was 'big ideas'. I was briefly excited by this, until I discovered it was a delusion - they actually wanted small ideas. The smaller the better.

This slightly world-weary blog post is critical of Labour, because this is somewhere where they always end up. But it is only fair to point out that every party has their besetting sin when it comes to developing policies. The Conservatives certainly have one ("I see no problem"). So do the Lib Dems ("well, I wouldn't start from here if I were you").

What is infuriating about Miliband's speech is that this particular example of wheeze-itis is so obvious in its origins. It was so obviously cobbled together in a focus group that it almost still shows the signs of the bourbon biscuits eaten during the event.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on September 24, 2014 01:26

September 23, 2014

Tesco and the great technocratic secret

The news that Tesco, formerly the Great Satan of anti-monopoly campaigners, have overstated their estimated profits by £250m is rather extraordinary – but only logical, given the way the politics of measurement is developing.

The news that Tesco, formerly the Great Satan of anti-monopoly campaigners, have overstated their estimated profits by £250m is rather extraordinary – but only logical, given the way the politics of measurement is developing.They have succumbed to the spirit of the age, and the besetting sin of Westminster and Whitehall: the idea that figures will always represent reality.

If you believe that, and unfortunately many of us do, it is but a short step to the obvious conclusion: if you change the figures, you can change reality.

You can see why some public service managers and their voluntary sector contractors fall under the delusions of this idea. The whole system encourages them to do so – their success or failure depends on them subverting the cage of outcome figures created for them.

Years so, a New Economics Foundation colleague of mine overheard the voluntary sector people counting attendance at a public meeting say: “If any couples come in, put them both down as women – we don’t have enough of those.”

Out of these small lies, big lies hatch. But both are symptoms of the basic mistake – that you can measure progress objectively like this.

You can see why politicians fall for it. The English doctrine of only doing the minimum required to achieve an administrative outcome leads inexorably to this idea – why do we have to actually reduce unemployment, after all, when all you need to is manipulate the definition? Or so they whisper to each other.

You can see why financiers fall for it. Change the figures, change the belief and you move markets, and there is a residial idea that prices are always real.

Collectively, we seem to have fallen under the spell of the utilitarian idea that everything can be measured, every problem calculated, every issue resolved by data. The truth is that numbers are indeed hard and objective, but they are chained irrevocably to definitions, which are endlessly malleable.

This is the great truth about evidence-based policy which the Masters of the Universe have convinced themselves that only they understand.

Data, statistics, evidence – those are for the hoi polloi – they know the truth: there is no objective reality.

Actually, this is just as much of a delusion, but this quiet understanding leads to the present corruption – manipulated data in public services, Libor rate manipulation, tweaked definitions in every area of public life.

One answer is to set up trusted institutions – monetary policy committees, NICE, offices of budget responsibility and so on – but those soon get dragged into the controversy. They remain influenced in a subtle way. How could they not be?

The other, more commonsense idea, is to remember that there is no way out of the human business of making complex judgements. We can’t escape it – and the sooner we wake ourselves up from the utilitarian Big Data dream and start doing so again, the sooner we might be able to take some control of our own destinies again.

Published on September 23, 2014 04:42

September 22, 2014

The death knell for failed UK centralisation

It's a funny thing but I found myself suddenly emotional about the Scotland vote on Friday. Having been far less convinced about the future of the union as maybe I should have been - what does nationhood mean in practice these days? - I happened to be on the phone to an office selling sheds in Edinburgh after the result come in.

It's a funny thing but I found myself suddenly emotional about the Scotland vote on Friday. Having been far less convinced about the future of the union as maybe I should have been - what does nationhood mean in practice these days? - I happened to be on the phone to an office selling sheds in Edinburgh after the result come in.I felt an overwhelming urge to say to the friendly Scottish voice at the other end how glad I was that we were still in the same country. I managed to restrain myself - perhaps I shouldn't have - but I am glad.

The prospect of being what I've always wanted to be - a Liberal little Englander - was, in the end, outweighed by three centuries of partnership and a faint memory of Night Mail, and Auden's poem set to Britten's music.

Three things now seem to be clear:

1. The big loser of the whole affair was Ed Miliband, and it was pretty clear that he doesn't have the charisma to shift the nation, as he rather clearly failed to shift Scotland.

2. You can't have major constitutional change without some kind of cross-party consensus, as Danny Alexander bravely pointed out over the weekend.

3. Where is Charter 88 now that you need them?

A brief aside: I spent the 1992 general election helping to organise well over 100 local Charter 88 debates the week before polling, all about the UK constitution. It was known as Democracy Day, and it had a huge impact, but little effect at the time. Even so, five years later, a great deal of the consensus (PR for Europe, national parliaments etc) was enacted by the Labour government with Lib Dem support.

Nothing is quite so conveniently available off the peg this time. But my overwhelming sense is that the period of centralised government by Whitehall - the invention of a combination of the Attlee government of 1945, driven ad absurdam by the Thatcher government of 1983 - is now over ("The gentleman in Whitehall really does know better what is good for people than the people know themselves," Douglas Jay, 1937).

Somehow or other, the next government is going to have to find us a more effective, more innovative form of government, handing powers out widely to cities and counties, as part of a wider settlement that is far more important than the development of an English parliament at Westminster (another kind of centralisation, it seems to me).

Centralisation has been tried and failed. I'm reminded of the Gladstonian doctrine here which distinguishes between Liberalism and Conservatism, and carved under the bust of the Grand Old Man in the lobby of the National Liberal Club:

"Liberalism is trust in the people tempered by prudence. Toryism is distrust in the people tempered by fear."

Published on September 22, 2014 08:02

September 18, 2014

The two Scotlands

Yes, I know, it's almost too late to comment on Scottish independence - they're voting today. I suspect that the result, whatever it is, won't be the end of the debate, so I'm having another shot at it.

Yes, I know, it's almost too late to comment on Scottish independence - they're voting today. I suspect that the result, whatever it is, won't be the end of the debate, so I'm having another shot at it.It is interesting, watching the news coverage, how much of the Yes case is bound up with anger about what might be broadly termed 'inequality'.

This is the sense I get from the vision of Two Scotlands. It isn't so much the haves and the have-nots, but it is about different beliefs about how the have-nots might eventually have.

The financial elite believe inequality is an outdated irrelevance, which has little to do with them. Meanwhile the currency shoots up and down in value because of the fears of secession across Europe - and all driven precisely because people no longer feel a stake in their own nations.

The truth is this: inequality is market sensitive after all.

Having said all that, I don't know - in the new world of interdepedence - whether nationhood really means anything any more. Not in practice.

And that fact is, as much as anything, down to the legacy of the Scottish enlightenment, and its emphasis on humanity and rationalism. That is the message of Adam Smith, Lord Kames, James Boswell and all the rest of them.

And here we really see the Two Scotlands. In 1745, when the highlanders reluctantly rallied to the flag of Bonnie Prince Charlie, those involved in the Scottish enlightenment barred the gates of Edinburgh and Glasgow against the rebels.

Bonnie Prince Charlie was a Roman Catholic, and therefore wholly unacceptable to the traditional Calvinist elders in the central belt of Scotland – the great medieval cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow

But he was also opposed by the new traders of Glasgow and the new middle class academics and publishers of Edinburgh. He was a symbol of the old-fashioned world for those who were lighting the first sparks of intellectual excitement that were emerging, and would be known to history as the Scottish enlightenment.

The irony was that it was this dismal moment of Scottish defeat that made possible a new kind of Scotland which gave itself to the world. The final capitulation of the other Scotland, the medieval memory of clan loyalty and absolute authority, was finished.

It was dead and mourned, but its destruction had made way for the new Scotland to emerge. It emerged in a way that it did almost nowhere else in Europe, among a group of like-minded writers, philosophers, historians and lawyers, who wanted to dispel the old fog of Calvinism and look at mankind differently.

Human nature and the scientific study of mankind was at the heart of the beginning of the Scottish enlightenment, and the defence of Edinburgh against the rebels also fell to the enlightenment.

They were led by the mathematics professor Colin Maclaurin. The future historian William Robertson joined him as a volunteer on the battlements. The seventeen-year-old future architect Robert Adam was his assistant. The defence failed and the volunteers repaired to Turnbull’s tavern for claret.

When the news of Culloden came through, celebratory bonfires were lit all across Glasgow as well.

David Hume was away tutoring the Marquis of Annandale, who was classified as a ‘lunatic’ (it was not a happy relationship). Smith was having his nervous breakdown in Oxford. The future writer James Boswell was in Edinburgh, but still only five years old. They missed the excitement, but it was really only after the trauma of the rebellion that the enlightenment was free to spread its wings.

So when we think of the Two Scotlands today, remember that it is in this sense a longstanding division, and it has at its heart a different understanding of nationhood.

I think of it as closer to Robbie Burns' idea that human beings, whatever their nation, "shall brothers be for 'a that".

Published on September 18, 2014 05:18

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.