Jane Brocket's Blog, page 35

September 14, 2012

reaching for the sky

When I was ten, I was very ill with life-threatening complications of appendicitis. I had to go back into hospital later that same year to have the appendix removed, but this time I was fit and healthy before the operation and could plan what to take in with me to read afterwards (I had to stay in quite a while). I don't know how I'd come across it, but I took Reach for the Sky (1954), a thick biography of Douglas Bader, an ace fighter pilot in WW2 who spent time in Colditz Castle after several attempts to escape from previous holding places. What fascinated me, though, was the fact that he'd lost both his legs (one above and one below the knee) in a flying accident a few years before the war.

Reach for the Sky is also the name of the 1956 film about Bader which stars Kenneth More as the eponymous hero, but it's nothing like as good, exciting and detailed as the book which enthralled me. The descriptions of the pain of learning to walk again on tin legs put my post-operation pain into proportion, and I enjoyed imagining knotting my bed sheets together to escape from Stockport Infirmary in the same way that Bader tried to escape from a German hospital. (The Germans had enormous respect for Bader. When his plane was shot down over France and he had to bail out, he was forced to leave behind one of his legs which was trapped in the cockpit, but the RAF were given safe passage to parachute in a replacement leg for him.)

So when I see my very tall sunflowers growing upwards, the phrase 'reach for the sky' always comes to mind and makes me think of Douglas Bader who didn't let the loss of two legs prevent him from flying. Apparently, he was an intense, competitive, and difficult man (even before the accident) and nothing like the mild-mannered and terribly polite Kenneth More film version. But the real Douglas Bader was an inspiration to me as a ten year old; I can still recall reading the descriptions of his stumps rubbing against the first horrible pair of tin legs as he learned to walk again (he got better prosthetic legs later), and I was astounded by his sheer determination to fly after the accident. So although I left hospital minus an appendix (but I did take it home with me in a jar), I gained a new hero.

(Until a couple of years ago, there was a beautiful pale pink tulip called 'Douglas Bader' and I used to grow it for the connection and because it was lovely. Ironically, it wasn't very tall. Unfortunately, it's no longer available.)

September 12, 2012

west dean

Curly details in the room.

Timeless English view from the room.

Portrait of the benefactor as a young man, hanging in the corridor outside the room.

Extravagant staircase: tapestries, oil paintings, animal heads, enormous chandelier - the usual sort of thing you see on your way up and down stairs.

Crochet at West Dean.

I got lucky with my room this time. It had a high ceiling, tall shutters, an enormous fireplace, a gold-framed mirror, and a wardrobe that could hide a family of five. It was on the plush corridor, no doubt where the family or the poshest guests stayed when it belonged to the James family. It was only half the size it once was - it's been divided into two - but it still offers a flavour of country house weekends with roaring fires, billiards, croquet, and walks in the rolling Sussex countryside.

West Dean is a cracking place for a short creative course (the list is extensive - even I fancy blacksmithing and willow-weaving after reading it). There is the house itself, the surreal art, the facilities, the library, the food (you never go longer than a couple of hours without some form of sustenance), the tutors, the space and fresh air outside, and the renowned gardens opposite.

I've just spent a couple of days crocheting with Lucinda Guy who is very nice, and very good at crochet and teaching crochet. As always with West Dean, I have come back full of inspiration and creative energy. And plans to make our staircase a little more exciting.

September 10, 2012

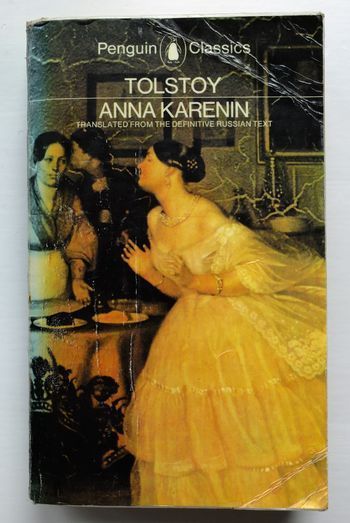

anna karenina

[my first copy of the book with my favourite cover, a detail of The Major's Wooing (1848) by Fedotov]

I first read Anna Karenina in the back of a Securicor van. The kind that has a driver and second-man in helmets, and an unseen 'backman' inside with a radio and the money, and goes around picking up and dropping off at banks and offices and high street businesses. I was a backman for the summer after I left school and, once I'd got the hang of the phonetic alpahabet and found the emergency siren on-off button, it was actually incredibly boring. Occasionally, if we stopped at a working men's club, the frontmen would put a meat pie in with the boxes of money, and I was once let out of the van to see the biggest vault and largest pile of banknotes in Manchester, but otherwise as long as I knew where we were and what the next stop was, I could doze or read as much as I liked. I chose to read, because the drivers had a nasty habit of waking you up with the siren.

So I read Anna Karenina (the copy above). I'd just done A level Russian and was about to go to university to study Russian. I read it with pure pleasure, and I was swept away. It instantly became my favourite book and, more seriously, informed my personal morality forever. I loved and disliked Anna in equal measure and saw the abandonment of her child as her primary sin. I disliked Karenin but admired his goodness. I saw Vronsky as nothing but trouble, and I wanted to live happily like Kitty and Levin but without the backbreaking scything. I found it hard to condemn anyone outright, and was as conflicted as Tolstoy about the rights and wrongs of the main characters' actions, but deep down I decided the passion was too destructive to be worth it.

Three years later, I read the same copy of the book, by now covered Blue Peter-style in sticky back plastic, in India. This was after three years' immersion in the Russian classics, Russian history and language, Russian/Soviet politics, and being part of a small, oddball department full of enthusiastic lecturers and students. I couldn't take much with me, and I chose Anna Karenina to go in the backpack. I read it on the trains between Delhi and Agra and the beaches of the south, and it gave me just as much pleasure as before and I found a much greater depth this time (though it was very odd to be reading of snowy Moscow in searingly hot temple towns).

[full painting]

So Anna Karenina carries a lot of weight with me. I still think it's one of the best books ever written. I've seen several of the film and TV adaptations but find that the usual treatment reduces the massive scope of the novel into just yet another story of doomed love. I wasn't sure how I'd find the new film, whether Keira Knightley would be able to carry off the title role, and I'd seen some of the mixed reviews.

But I thought it was brilliant. It is clever, creative, beautifully orchestrated, visually wonderful and, what no-one has said so far, incredibly Russian. No-one has pointed out the fact that Tom Stoppard is Czech by birth and has translated the work of many Central European playwrights and must, therefore, be well placed to capture the great vitality and energy of Tsarist Russian society. So the film feels and sounds and looks authentic. It also has a great dramatic quality; at times I felt as though I was in a theatre watching a play, something that usually irritates in a film but is impressive here. The lighting is always beautiful, and the costumes, jewellery, and hair are exquisite. Even the ball works (without fail, it's the scene I like least in any period drama, esp. anything from Jane Austen) because Joe Wright doesn't do the usual thing but turns it into something you might see done by Bolshoi Ballet dancers. The only dud note is the casting of Aaron Taylor-Johnson as Vronsky, mainly because he is simply too young. Vronsky needs to be older, more dangerous, more worth throwing your life away for. But Keira K was a revelation; she's becoming a seriously good actress now that she's older, and can be controlled and majestic, or energetic, girlish and charming as the scene requires.

It's quite something for me to disagree with newspaper reviewers by rating a film more highly than they have (if anything, when I don't agree it usually because I think less of a film), but this Anna Karenina does justice to the spirit of Tolstoy's book and, at the same time, it creates a stunning film-play from the text. I would happily watch it again, just as I would happily read it again.

September 7, 2012

bella bella

I'm still making quilts, still enjoying looking for and using lovely fabrics. I'm just finishing writing my second quilt book which won't be published for a while yet, and it contains about twenty quilts which have been great fun to make. But I don't have plans to stop making quilts once the book is handed in. Oh no. In fact, I'm as enthusiastic as ever, especially as there are so many beautiful fabrics around.

I've just bought some of the new Lotta Jansdotter collection, Bella, which is fresh, clean, modern, zingy, simple yet very striking. I love Lotta J's aesthetic; it's the kind of look I feel I should aim for - then I glance around and think 'no chance, far too late'. But that doesn't stop me seeing the amazing number of possiblities in the designs; the collection is very cleverly put together and you really don't need any extra fabrics, except perhaps a plain white to enhance that crisp, airy, Scandinavian feel.

I made a quilt recently with Lotta J's first collection Echo (also from Windham, one of my very favourite fabric companies). That, too, was a revelation to work with as I found it was difficult to go wrong using only her fabrics. But I was amazed at how quickly it went out of stock. Not long after it was launched, I bought enough for a quilt, but when I was looking for more fabric for the back, the selection of designs available was vastly depleted (especially here in the UK). It made me wonder once again why quilting fabric companies insist on letting their best-selling fabrics go out of print after one run, and replacing them six months later with a brand new collection.

I know there might be good economic reasons for this constant emphasis on the new, but I 'm not sure why so many enormously poopular and successful collections are never reprinted. Why not keep the 'classics' in print as book publishers do? Why generate all that creativity and hard work but deny the results the opportunity to sell as well as they deserve to - and would, given the chance? It seems mad not to keep reprinting the bestsellers just as Liberty does with its Tana lawn, Marimekko with its huge poppies, and Sanderson with its cabbage roses (and I don't see William Morris' designs disappearing). If a pattern is good it will appeal for a long time, long after other not so lovely collections have been and gone.

Interestingly, there are some signs that things might be changing. The wonderful 'Flea Market Fancy' collection by Denyse Schmidt is now available again as a legacy reprint, and Westminster Fibers have brought back some of Martha Negley designs in a . But these are only two out of a huge number of collections that deserve to stay in print. It pains me to think that Lotta J's Echo fabrics are already a thing of the past, and that the same fate awaits her bella Bella collection. And,while I'm at it, could someone please arrange for the much-missed 'Lille' collection by Kaffe Fassett to be reprinted?

September 5, 2012

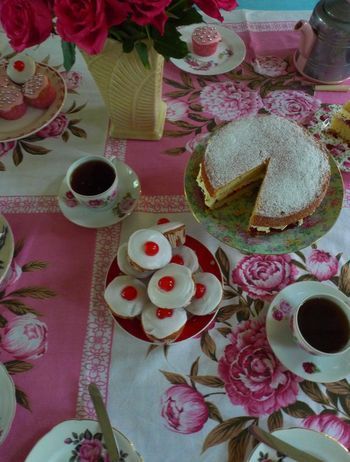

vintage cakes

[my photo of the shot that's on the book cover]

My book Vintage Cakes is available now. Here and here and here and here, and in all good bookshops. It's full of tried-and-tested favourites and classics, including all the cakes I bake regularly. I'm thrilled with it, and hope you like it, too.

September 3, 2012

between the acts

[the garden at Charleston Farmhouse where members of the Bloomsbury group often held theatrical performances]

Oh, dear. I seem to have got stuck between the acts in Between the Acts. I have ground to a halt with my reading of Virginia Woolf's novels. I missed out the first Night and Day so I suppose it's appropriate that I haven't quite read Between the Acts, her last novel. It's not for want of trying; the book has been everywhere with me over the last couple of weeks, but I think I might have had a surfeit of Woolf.

My other excuse is that I have never liked plays within plays or novels, or poems within novels, or really anything in a novel that asks me to imagine that a character wrote it rather than the author. I always skip poems and extracts from books in novels (then find later that they contained something vital to the plot), and I kept wanting to skip the play in Between the Acts. (If I'm being very pernickety, I have to say I don't deal well with the change to italics for the play parts, and the constant ellipses...drove...me...mad.) I can see that there is plenty to admire in the book, but repetition of the usual themes finally wore me down. I need something different to read now, something more warm and Whippleish. (In time, I will reread the very interesting sections on Between the Acts in Romantic Moderns and see if I can tackle it again.)

[I found some wonderful photos of a 1908 pageant here. I imagine the pageant in Bewteen the Acts might have looked a little like this.]

September 2, 2012

sunflowers

Goodness knows what was going on with apostrophes at Columbia Road flower market this morning, but the sunflowers were amazing, and the bagels at Jones Dairy (no apostrophe) on Ezra Street were brilliant.

August 31, 2012

upside-down orange muffins

August 30, 2012

the years

[Autumn Leaves (1856) John Everett Millais, Manchester Art Gallery]

I've been thinking about this Virginia Woolf novel a great deal since finishing it. The problem is that I thought I was reading one book, only to discover during and after that I'd been reading a very different book altogether. This is what The Years does; it wrongfoots the reader, setting him/her up to read one way, only for it to break up into something very odd and disconcerting. You may begin by thinking it's a recognisable family saga, the sort of thing Galsworthy might write, but it doesn't take long before the saga collides with both Dickens and Chekhov, and the likes of John Osborne and even JG Ballard.

It opens as a late Victorian novel about a large family living in London, which is all quite comfortable and familiar. You believe you know where you are and where you are going. But almost immediately, there's the father with two stumps on his hand where his fingers are missing, and a frightening flasher under a lamp, leering at a young daughter who has left the house without permission. From there, it's not long before the novel is full of the usual VW mix of London life, glimpses into large lamp-lit houses, tea-time conversations, but now mixed with broken communications, touches of madness, wandering minds, and outbreaks of disgust and anger. All the way through, I was searching for the novel I thought I was reading but had somehow lost, and it took time to realise that I should be reading in a very different way, looking for very different things, making very different conclusions.

The Years is, like all VW's novels, full of repeated motifs, themes, details whose repetition I found oppressive and headache-inducing, presented as they often are in an atmosphere of morbid sensitivity. There is washing and cleansing (shades of Lady Macbeth and 'Out, damned spot!'), dirt, diseased skin, many baths and a great deal of running water, cold winds, birds and birdsong, twigs falling from trees, and leaves in all seasons, wine and the blurring of perception that comes with it, hands on shoulders, hands on knees, hands on clocks, coins and money, dressing tables and mirrors, dogs, bells, hammers, and the sounds and noises of London on every page. People are regularly late, there are fires and flames and a great deal of burning, kettles and hair-pins, windows, portraits and pictures (each section opens with a landscape picture in words) and statues and monuments, staircases and a lot of going up and down, top floor rooms, and many cows and foreigners. Just as this list shows, it is muddled in the way that a dream or, more likely, a nightmare jumbles everything but with horrible clarity, as objects and stuff loom out of a mist or the dark corners the mind. As the novel continues, the interruptions in thoughts and lost threads increase, and no-one seems to take any notice of others' difficulties in thinking clearly. It remains recognisable but somehow hellish; 'How many people, she wondered, listen?' is clearly the question at the centre of this broken-down world.

By the end the I found it painful to read.The apparently normal world has an increasingly odd, sometimes hallucinogenic and feverish feel, reminiscent of the hysterical madness of Ophelia and the ravings of Lear's fool. The loss of communication, the truly awful anti-Semitism, the treatment of 'foreigners', the constant breakings-off, lack of coherence, the muddles and oddness all tested my patience and reading skills. And yet, historically this book has been described as having a happy, positive ending with the family party and the sight of a young couple going into their house.

Perhaps The Years needs to be read a different way and most definitely not as a family saga or a historical novel. It might help to stop thinking that even VW herself knew what she was writing. She edited and changed the text over and over, it made her ill, it became a monster. Even if you don't know this beforehand, you feel it as you read. The breaking out of what lurks below the surface of facts and objects and all the things she couldn't wash away or eradicate (sex, touching, physicality, dirt, foreigners, human nature, failures in communication) are what makes it such an interesting but uncomfortable novel. Once we see beyond the apparent novelistic structure, it becomes far darker, more disturbing and, dare I say, more Dickensian book.

I admit I struggled to see the range and depth of possible readings of The Years until I read the fantastic introduction by Professor Steven Connor in the Vintage edition. Although I knew I'd found a huge amount of themes and subtexts, I wasn't putting them together in the way that Connor does. It would take another reading to find out for myself that, as Connor suggest, this is the novel that VW couldn't control which makes it the most revealing of all. And, at the moment, I just couldn't manage another reading.

August 28, 2012

the things we do for love

Like going to see North by Northwest with your Mum at the BFI, as Alice did last night. (Simon couldn't use his ticket because he's in Thailand.) Even though I've watched it many times, it was really worth going to see it on a big screen. It made the tension much more tense, and made Cary look better than ever. I also noticed how the main colour scheme throughout is silver-grey and rich tan which matches Cary's hair/suit and skin colour to perfection.

Like going on (what feels like) the tallest, scariest, most exposed ride ever with your daughter, as I did last night because Simon would never do something as daft as that, and she wanted someone to go on it with her. Plus, if the chains were going to break, we might as well both be flung across Waterloo or into the Thames. Good views of London at night up there, though. Amazed I kept my eyes open. (It's the Star Flyer at the Southbank 'Wonderground' funfair.)

The Things We Do For Love by that great Manchester band, 10cc.

Jane Brocket's Blog

- Jane Brocket's profile

- 27 followers