Justin Taylor's Blog, page 48

September 5, 2016

What Is the Longest Book in the Bible? (Hint: It’s Not the Psalms)

Most resources claim that the book of Psalms is the longest book in the Old Testament, and therefore the Bible.

The claim is probably wrong.

If the calculation is based on the number of verses or the number of “chapters” or the number of pages, it is correct. But since those aren’t part of the original, and because some books may have words per verse or more words per chapter than another book, neither of these would be the right criteria to use.

And if we really want to calculate the lengths of the originals, English word-count shouldn’t be sufficient, either, since they are translations of the Hebrew and Greek. (Sometimes it takes several English words to translate one Hebrew or Greek word, for example.)

Here is a more refined set of date, courtesy of David J. Reimer (senior lecturer, Hebrew and Old Testament, University of Edinburgh, who penned the notes on Ezekiel for the ESV Study Bible).

Some notes:

“Graphic units” counts the number of Hebrew words in a particular books using BibleWorks (e.g., there are seven “graphic units” in Genesis 1:1).

“Morphological units” was found according to the Groves-Wheeler Westminster Morphological database (which separates prefixed elements, but not pronominal suffixes; e.g., there are eleven “morphological units” in Genesis 1:1).

The “Bytes” figure calculates the length of the Hebrew book in ASCII format (i.e., so there is no interference from extraneous word-processor code).

Here are the results of the top 10, which account for about 55% of the 39 books of the OT:

Order

Book

# Verses in Book

Graph-unit Hits

Morph-unit Hits

Bytes

1.

Jeremiah

1,364

22,285

30,203

241,209

2.

Genesis

1,533

20,722

28,848

226,894

3.

Psalms

2,527

19,662

25,465

238,562

4.

Ezekiel

1,273

19,053

26,572

214,416

5.

Isaiah

1,291

17,197

23,204

191,777

6.

Exodus

1,213

16,890

23,934

184,372

7.

Numbers

1,289

16,583

23,363

182,945

8.

Deuteronomy

959

14,488

20,329

159,872

9.

2 Chronicles

822

13,520

20,000

154,125

10.

1 Samuel

811

13,506

19,211

147,392

August 31, 2016

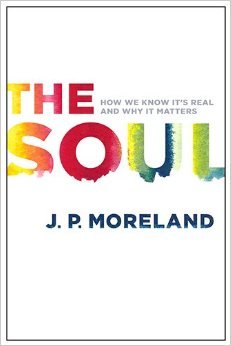

An FAQ from J. P. Moreland on the Human Soul

Some notes from J. P. Moreland’s excellent book, The Soul: How We Know It’s Real and Why It Matters (Chicago: Moody Press, 2014).

Some notes from J. P. Moreland’s excellent book, The Soul: How We Know It’s Real and Why It Matters (Chicago: Moody Press, 2014).

What is dualism?

The view that the soul is an immaterial thing different from the body and brain.

What is substance dualism?

The view that a human person has both

a brain that is a physical thing with physical properties, and

a mind or soul that is a mental substance and has mental properties.

What is Thomistic substance dualism?

The view that the (human) soul

diffuses,

informs (gives form to),

unifies,

animates, and

makes human

the (human) body.

The body is not a physical substance, but rather an ensouled physical structure such that if it loses the soul, it is no longer a human body in a strict, philosophical sense.

What is the soul?

The soul is a substantial, unified reality that informs (gives form to) its body.

The soul is to the body like God is to space—it is fully “present” at each point within the body.

The soul and body relate to each other in a cause-effect way.

Do animals have souls?

Yes, animals have a soul. But an animal soul . . .

is not as richly structured as the human soul

does not bear the image of God

is far more dependent on the animal’s body and its sense organs than is the human soul.

What are four arguments for substance dualism and the immaterial nature of the soul?

1. Our basic awareness of the self

We are aware of our own self as being distinct from our bodies and from any particular mental experience we have, and as being an uncomposed, spatially extended, simple center of consciousness.

This grounds my properly basic belief that I am a simple center of consciousness.

In virtue of the law of identity, we then know that we are not identical to our body, but to our soul.

2. Unity and the first-person perspective

If I were a physical object (a brain or body), then a third-person physical description would capture all the facts that are true of me.

But a third-person physical description does not capture all the facts that are true of me.

Therefore, I am not a physical object. Rather, I am a soul.

3. The modal argument

I am possibly disembodied (I could survive without my brain or body).

My brain or body are not possibly disembodied (they could not survive without being physical).

Therefore, I am not my brain or body, I am a soul.

4. Sameness of the self over time

A physical object composed of parts cannot survive over time as the same object if it comes to have different parts.

My body and brain are physical objects composed of parts that are constantly changing, and therefore cannot survive over time as the same object.

However, I do survive over time as the same object.

Therefore, I am not my body or my brain, but a soul.

What is the relevance of neuroscientific data to whether or not we have a soul?

Neuroscience is a wonderful tool, but it is inept for resolving disputes about the nature and existence of consciousness and the soul. The central issues in those disputes include philosophical, theological, and commonsense topics. Neuroscientific data are simply irrelevant for addressing those topics.

Neuroscience shows correlation between mind and brain, not that mind and brain are identical.

How is the law of identity relevant to this relationship?

Leibniz’s law of the indiscernability of identicals states that for any entities x and y,

if x and y are identical,

then any truth that applies to x will apply to y as well.

Some things are true of the mind or its states that are true of the brains or its states; therefore, physicalism is false and dualism (provided it is the only other option) is true.

What are the states of the soul?

Just as water can be in a cold or hot state, so the soul can be in a feeling or thinking state.

Here are five such states:

sensation: a state of awareness, a mode of consciousness (e.g., a conscious awareness of sound or pain)

thought: a mental content that can be expressed as an entire sentence and that only exists while it is being thought

belief: a person’s view, accepted to varying degrees of strength, of how things really are

desire: a certain inclination to do, have, avoid, or experience certain things

act of will: a volition or choice, an exercise of power, an endeavoring to do a certain thing, usually for the sake of some purpose or end

What are the faculties of the soul?

The soul has a number of capacities that are not currently being actualized or utilized.

Capacities come in hierarchies:

First-order capacities (e.g., I have the first-order capacity or ability to speak English)

Second-order capacities to have first-order capacities (e.g., I have the potential to speak Russian, though it is not actualized)

And so forth

Higher-order capacities are realized by the development of lower-order capacities under them.

The capacities within the soul fall into natural groupings called faculties. A faculty is a “compartment” of the soul that contains a natural family of related capacities. For example:

Sensory faculties

sight (All the soul’s capacities to see are part of the faculty of sight. If my eyeballs are defective, then my soul’s faculty of sight will be inoperative just as a driver cannot get to work in his car if the spark plugs are broken. Likewise, if my eyeballs work but my soul is inattentive—say I am daydreaming—then I won’t see what is before me either.)

smell

touch

taste

hearing

The will: a faculty of the soul that contains my abilities to choose

Emotional faculties: one’s abilities to experience fear, love, and so forth

Mind and spirit

Mind: that faculty of the soul that contains thoughts and beliefs along with the relevant abilities to have them

Spirit: that faculty of the soul through which the person relates to God (Ps 51:10; Rom 8:16; Eph 4:23) [prior to regeneration, most of the capacities of the unregenerate spirit are dead and inoperative; at the new birth, God implants new capacities in the spirit]

August 26, 2016

J. Alec Motyer (1924-2016)

Renowned Old Testament pastor-scholar J. Alec Motyer has passed away at the age of 91.

Renowned Old Testament pastor-scholar J. Alec Motyer has passed away at the age of 91.

Born John Alexander Motyer (pronounced maw-TEAR [as in the “tear” of “teardrop”] in Dublin, he graduated with a BD (1949) and MA (1951) from Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin, Ireland, and did further studies at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford.

He was ordained in the Church of England in 1947 as a deacon, and then in 1948 as a priest, serving as a curate in Penn Fields, Wolverhampton (1947-1950), and at Holy Trinity Church in Bristol (1950-1954). In Bristol, he also served as Tutor, and then Vice Principal, of Clifton College (1950-1965).

From there, he became Vicar of St Luke’s, West Hampstead (1965-1970), but returned to Bristol as Deputy Principal of Tyndale Hall (1970-1971), and then became the Principal of the reconstituted Trinity College (1971-1981).

His final decade of active parish ministry was as the Minister at Westbourne (Bournemouth) (1981-1989).

A biographical sketch summarizes some of his publication and influence:

Few men of his generation have taught so many Anglican ordinands while also having parish experience and academic distinction; of a clearly Reformed stamp, for more than 40 years he has also been an occasional speaker at the Keswick Convention and some of its overseas equivalents. The author of an early ‘Tyndale monograph’ on Exod 6, The Revelation of the Divine Name (1959), a ‘Hodder Christian paperback’ After Death(1965), and a major commentary on Isaiah (1993), he has also contributed to Bible and Theological Dictionaries and written on Amos, James, Philippians, Zephaniah and Haggai, Psalms, Exodus, (‘A scenic route through the OT’ and ‘The days of our pilgrimage’), on the OT in general (Discovering the Old Testament) and (with his son Stephen) on Thessalonians.

You can watch him explain below why he thinks John 1:12 is the Bible’s best text:

Tim Keller explains the influence on his own approach to the Bible, becoming one of his “fathers in ministry”:

Approximately 40 years ago, during the summer between my undergraduate college years and seminary, I was working and living with my parents in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. One evening I drove over the mountains down into a long valley in the midst of the Laurel Highlands and came eventually to the Ligonier Valley Study Center, just outside the little Western Pennsylvania hamlet of Stahlstown, where R. C. Sproul was hosting at his regular weekly Question and Answer session a British Old Testament scholar, J. Alec Motyer. As a still fairly new Christian, I found the Old Testament to be a confusing and off-putting part of the Bible.

I will always remember his answer to a question about the relationship of Old Testament Israel to the church (I can’t remember if R. C. posed it to him or someone from the audience). After saying something about the discontinuities, he insisted that we were all one people of God. Then he asked us to imagine how the Israelites under Moses would have given their “testimony” to someone who asked for it. They would have said something like this:

We were in a foreign land, in bondage, under the sentence of death. But our mediator—the one who stands between us and God—came to us with the promise of deliverance. We trusted in the promises of God, took shelter under the blood of the lamb, and he led us out. Now we are on the way to the Promised Land. We are not there yet, of course, but we have the law to guide us, and through blood sacrifice we also have his presence in our midst. So he will stay with us until we get to our true country, our everlasting home.

Then Dr. Motyer concluded: “Now think about it. A Christian today could say the same thing, almost word for word.”

My young self was thunderstruck. I had held the vague, unexamined impression that in the Old Testament people were saved through obeying a host of detailed laws but that today we were freely forgiven and accepted by faith. This little thought experiment showed me, in a stroke, not only that the Israelites had been saved by grace and that God’s salvation had been by costly atonement and grace all along, but also that the pursuit of holiness, pilgrimage, obedience, and deep community should characterize Christians as well.

Not long after this I heard a series of lectures by Edmund P. Clowney on the importance of ministers always preaching Christ, even when they are preaching from the Old Testament. Dr. Motyer’s little bombshell and Ed Clowney’s lectures started me on a lifetime quest to preach Christ and the gospel every time I expound a Biblical text. They are, in a sense, the fathers of my preaching ministry.

While I believe I have read and used all of Dr. Motyer’s published works over the course of my life, three of his books were transformative to my ministry in particular. In my early days as a preacher his commentary on Amos, sub-titled “The Day of the Lion,” was a huge help to me as I struggled for the first time to expound the minor prophets. That work showed me God’s emphasis on social justice and righteousness, a standard he applied not only to his own covenant people but also to the nations around them.

The second intervention came a couple of decades later, when I was convicted about the shallowness of my prayer life. In response, I began to dig into the Psalms, and the two resources I relied on were Derek Kidner’s Tyndale commentary and Alec Motyer’s brief but luminous treatment of the Psalms in the New Bible Commentary: 21st Century Edition. Dr. Motyer’s compact description of the psalmists—that they were people who knew far less about God than we do, yet loved him a great deal more—is a crucial guide for interpreting the anguished cries, shouts of praise, and declarations of love we meet in God’s own Prayer Book. It is clear at some points that we are reading authors who were writing about God’s salvation before the “fullness of time” had come and the Cross laid bare God’s plan for saving the world. And yet the psalmists—with their less granular understanding of the outworkings of it all—did indeed grasp the gospel of salvation by grace, substitutionary atonement, and faith. Across the 150 psalms we see virtually every human condition and emotion set before God and transfigured by prayer. The authors’ love for God convicts, uplifts, and instructs us as nothing else can. Through Motyer and Kidner I was ushered into a new stage in my journey toward fellowship with God.

Finally, a few years ago I tackled a series of sermons expounding the book of Exodus mainly because I saw that Dr. Motyer had produced The Message of Exodus in 2005. It did not disappoint and became my main go-to resource for the series.

On May 9, 2000, Robert Mills of The Presbyterian Layman conducted an interview with Motyer about his formative years and his approach to the Word of God.

“I’m not really a scholar,” says J. Alec Motyer softly, “I’m just a man who loves the Word of God.”. . . . [H]e learned to love the Scriptures at his grandmother’s knee in Ireland. “Grandma was, in worldly terms, a comparatively uneducated lady,” Motyer says, “but she was a great Bible woman. Biblical studies have simply confirmed that which I learned from Grandma – that the Bible is the Word of God – and made it a coherently held position.” . . . He adds, “I had a conversion experience when I was 15, but I can’t remember a time when I didn’t love the Word of God.”

What has liberal scholarship done to the Old Testament?

It has removed the Old Testament from popular understanding. The majority of people who have gone through liberal schools in their Old Testament studies have come out totally uncertain of what the Old Testament is about. When people are taught the documentary theory they cease to understand the Pentateuch. They’ve lost the whole flow, the doctrinal as well as the historical. They’ve ceased to be able to grasp the centrality, for example, of covenantal theology.

Has it been your experience that many Christians spend little time reading the Old Testament?

Very much so. Of course, nowadays we don’t live in a literary generation. We live in a generation of lookers, not readers. That is one of our great problems as Christians. We are book people in a non-book world.

What are Christians missing by not reading the Old Testament?

The death of the Lord Jesus as understood in Old Testament categories. We don’t understand the cross unless we understand the Old Testament category of sacrifice and the shedding of blood. Likewise, the New Testament doesn’t have as strong a stated doctrine of creation. It leans on the Old Testament to reveal the nature of man and the nature of God as creator.

We have a two way traffic. I’m very drawn to the model I first read in John Bright of the two-act play. If you have a two-act play and only have act one you ask, Where is it going? If you only have act two, you ask, Where has it come from? That is a very penetrating view of the Scriptures.

Are the Old and New Testaments compatible?

The whole Bible is bound together around the single theme “I will be your God and you will be my people.” The same way of salvation is found right throughout the Bible. We trust the promises of God and are saved. I would lay most stress on the singleness and unity of the people of God running right through the Bible. We are the people of God. [Early believers] should never have allowed the people of Antioch to get away with nicknaming them Christians. Our proper name is Israel.

How would you answer the modern Marcionites who effectively teach that there is a God of law and a God of love and that Christians must follow the God of love?

Well it’s just not true. That’s the beginning and end of that one. It’s just ignoring so much evidence in each testament. It’s trading in prejudice and lack of knowledge. The Old Testament is the place where we learn about the good shepherd looking after his sheep. God is in love with us. His heart goes pitter-patter when he sees us. That’s so plain in the Old Testament. Likewise the wrath and holiness of God are equally plain in the New Testament.

How do you convince ministers and lay people that the Old Testament is an important part of God’s self-revelation?

Apart from taking every opportunity to speak to people about the Old Testament, to show them what a lovely and fascinating book it is, the slow drip method, I don’t know of any other. We need to get the people to read the Bible for themselves and become acquainted with the fact that the same mix of material occurs in the Old as well as the New. We need to ask, If you think the Old Testament is the book of a wrathful God, have you read Revelation lately? Try to get people to fall in love with the whole thing and not come with prejudgments about what love is and what love would do.

How important are questions such as who wrote the first five books of the Bible?

The veracity of Scripture is well into this discussion because of the authorship claim. If a book makes an authorship claim, that is part of the revealed scripture. We must start with that and see how it works. We must not divert unless there is good reason for doing so.

When New Testament scholars dispute the Petrine authorship of II Peter or the Pauline authorship of Ephesians, they are touching on the veracity of Scripture.

There is no authorship claim in Genesis, therefore we must leave that aside and see if any of the rest of the Bible instructs us on that. For the rest of the Pentateuch, the Mosaic claim is very strong indeed. Nothing in Exodus is free of Mosaic mediation. And when we come to Deuteronomy, the words “Moses said” and “God said” are used as equivalents.

I don’t think serious Bible study can skate round the claim and testimony of the document itself. I think there has been a methodological error. In every branch of study the student starts from what the subject claims. Whereas in Biblical studies the starting point of study has so often been what seems to be a problem. Starting from that problem the whole construction of the documents is read out. You can’t start any study from a problem, you must start from testimony. But that would leave egg on many faces and require the rewriting of many books.

What can contemporary Christians learn from the various divisions of the Old Testament, the Law, the Prophets, the Writings?

What is laid down in the Law is basic, the basic revelation of the holy God and how sinners can be made acceptable to that holy God. That is very definitely the message of the Law, the Pentateuch.

The Pentateuch prepares for the Prophets. Deuteronomy is emphatic that those who have come to God through his saving grace now have a pattern of life to live out. The prophets elaborate on that. I don’t think it’s true to say the prophets are innovators. They are expositors. They expound on and apply Mosaic theology.

The Writings either tell us what to do with it, as in the Psalms, how to rejoice in the truth of God, or wrestle with it, as in Job and Ecclesiastes. The intended implication of a wisdom and power higher than ours and wider than ours is clearly there. God says, “Can you sit on the throne? I can. There are powers in the universe that you can’t oppose but I can.”

If you have a God of wisdom, justice and power, you have no escape hatch. Take any of those out and deny it and life is totally logical. Put all three together and the only way to face life is faith.

How are the Psalms useful to our Christian faith and life?

In many ways. First in a formal way they are our window into the Old Testament, therefore they are a corrective. I think many Christians assume that the Pharisees are typical Old Testament men. They forget that Jesus said the Pharisees were a plant his heavenly Father never planted. The real window for us, what was it like to live as a believer in Old Testament times, is the Psalms.

Second, they are a great challenge. Here are people who knew far less about God than we do and yet loved him a great deal more. Third, they are instructive. They are lovely poems in their own right. If you sat down and analyzed them as poetry you would come out with a rich theology.

What are some of the consequences when the church fails to protect its members from poor or even false teaching?

The main consequence of the moment is that we are ethically illiterate. Great moral questions are being aired without professing Christian people having any guidelines on the matter. The big question is homosexuality. The vast majority of people intuitively feel that this is not something they want to go along with, but they don’t have any basis of scriptural teaching on which to rest or from which to draw conclusions.

All sorts of things have happened in my lifetime and found the Church totally unprepared. The breakdown of marriage, for example; the sexual revolution, which is not really a revolution at all but just uncontrolled sexuality. That has not been faced by the Church as a whole with any firm, reasoned response.

What can people do who are not receiving sound Biblical teaching in their churches?

The vast majority don’t know what they’re missing. They’re not aware of the loss. If people come alive in God and have been brought into a new dimension of faith through the ministry of the Word of God, then they want such teaching and they are faced with jolly difficult decisions. Do they stay where they are and soldier on?

Philip didn’t seem to worry when he was snatched away and the eunuch was left on his own. He didn’t scratch his head and say, “What about counseling?” He said, “He is a man with the Word of God. He’s safe. Let him get on with it.” I think many, many people would seek out a church where the Word of God is preached and transfer their allegiance, and that’s a difficult thing to do.

August 24, 2016

Why the Critic of the Diet-Pill Pyramid Scheme Can Never Win

The conservative commentator David French:

The conservative commentator David French:

There are few things in life more frustrating than watching your friends become victims before your very eyes and being powerless to stop it.

The Kentucky church my wife and I frequented early in our marriage was one of the best churches I’ve ever attended. Never before or since have I seen such zeal for the Gospel or such a desire to reach the most desperate and vulnerable members of society.

It wasn’t a wealthy church. I was the only lawyer in the congregation, and there was only one doctor. Many people struggled to make ends meet. Sadly, that rendered them vulnerable to scams, and when a diet-pill pyramid scheme started racing through the congregation, I was aghast. People were spending money they didn’t have to join networks and create “down lines,” firmly believing that economic salvation was at hand. The sales pitch was slick, but the pills scarcely disguised the pyramid. One presenter even said, “You can get rich without even selling any pills.”

I’d worked on consumer fraud cases before, and I thought that I could help stop the madness. I went to the presentations, I researched the materials, and then I started talking to friends.

Some listened, but most got mad and a few got furious. To this day, those are some of the most painful conversations I’ve ever had, and I realize now why:

My friends were hearing two voices.

One of them was speaking authoritatively about numbers and dollars and selling hope.

The other was speaking with the same degree of assurance about numbers and dollars but was instead trying to extinguish hope.

I never stood a chance.

Yes, voters have a responsibility to exercise good judgment. But the greatest responsibility lies with the con artist and his knowing enablers. Trump — like Obama before him — is selling hope. But that hope is a false hope, and all those “establishment” figures who scorn the alleged “moral preening” of Never Trump know it. They’re aware of the pyramid scheme, and they choose to further it anyway, like the minions who circulate to cheap hotels across the land, pitching scams in meeting rooms. They’re co-conspirators. No one likes to be told they’re wrong. But it is, in fact, wrong to support Trump, and when I see a member of the GOP establishment selling the Trump brand, I’m transported back to Kentucky, watching a huckster exploit people I love.

For the full context, you can read the whole thing here.

Update: Note that French is mainly talking about Trump support among the GOP Establishment. He undoubtedly thinks it’s wrong for anyone to vote for Trump. I’d qualify this a little and say that though I disagree with those who will vote for Trump, I understand the reasoning of some.

The best thing I’ve read on Trump support by evangelicals, which captures my sentiments precisely, is this piece by David Bahnsen. Here’s a lengthy excerpt:

There are three categories of Trump supporters on the right. . . .

First, there are the people who were early adopters, those who actually jumped on his bandwagon well before there was any remote reason to do so. They are his apologists. They either ignore or shrug off his comments on McCain/POW record, his mocking a disabled person, and his inability to so much as name a major player in the global terrorist Jihad. On the low brow, pedestrian punditry level, they include Sean Hannity, Laura Ingraham, and Ann Coulter. There are others too. The rather lengthy list here includes a lot of people I didn’t care for before the election, and I certainly have no use for them now. I suspect for them, Trump had them the second he said “Mexican immigrants are rapists” – illegal immigration is their one-trick pony. And Trump “tapped into something” with them (perhaps the worst and most brainless cliché to have come out of the 2016 election).

Then there is category two Trump supporters, and this is the list that has by far caused me the most grief the last eight months. It is a list that has forced hours of soul-searching upon me, and frankly created an entirely new formulation of who I respect in conservative leadership. These are the people that well before Trump had sewn up the nomination, well before we were stuck with the “Trump or Hillary” dilemma, as a pure result of seeing him as a front-runner, not only threw in the towel and began to cozy up to him, but began a totally unforgivable process of rationalizing his perverse behavior and reconciling his ideological heresies through unrelenting gymnastics that still do not make any sense whatsoever. This list is massive, and I mean truly massive. I actually have a list. I am not kidding. It has many, many public figures on it, and it has caused me to lose immense respect for people you all know, and people you do not know. This list is not populated with people that “Trump tapped into.” It is not filled with people who “saw the light on the plight of the white middle class in rural and rust belt America.” It certainly is not filled with people who realized that “Trump alone can defeat ISIS.” It is filled rather with people who, I firmly believe, lacked the courage of their own convictions. It is a sad list, for it is people who absolutely should have known better. From Mark Steyn to Newt Gingrich to Ben Carson to Bill Bennett, and just innumerable others I can’t bear to list by name, this is the list that enabled Trump. And it has been painful to watch.

The third category is . . . the “look, Trump was not my guy, but I now have to support him because he’s certainly better than Hillary” camp. I strongly suspect the bulk of you reading right now are in this camp. Few category 1 and category 2 Trumpkins read my writings, and the sentiment embedded in category 3 is entirely understandable.

However, before I can present my response to this camp and discuss the “what now” of the U.S. Presidential election, I want to split category 3 up into two groups.

I will call the first “category 3a”, and they are those who were not enablers of Trump but now are prepared to support him to stop Hillary, but in doing so, have decided to actually defend much of the indefensible about him.

Category 3b is, in my estimation, more benign. It essentially is the group of people who really find Trump nauseating, and while they may hope he surprises them in a positive way, they are disheartened that he is the candidate, but simply cannot stomach the thought of a Hillary Presidency.

In other words, category 3a are those lying to themselves and others because they hate Hillary so much; category 3b are those who are telling the truth, and simply dealing with a painful electoral reality.

My response to 3a is this: Please join category 3b. It is not necessary to sell your soul to go to the “stop Hillary” level of thinking, and you lose all credibility when you accompany your “stop Hillary” thinking with a retroactive defense of that which is indefensible. Trump has not “tapped into something” on minimum wage, trade deals, ISIS, law and order, or how bold it is to insult disabled people and mock POW’s. His warm and fuzzy comments about Vladimar Putin and Saddam Hussein are not cute, and they actually reflect the intellect of a total dunce. He is a fine marketer and he has tremendous enablers in the press, but that does not mean it is “Reaganite” to have absolutely no policy depth (or employed policy advisors). It’s frankly shameful. It will likely cost him the election against the second most unpopular person in America. But you can go to category 3b without the corrosive sell-out actions of category 3a, so please resist that temptation.

Bahnsen then goes on to address category 3b supporters. It’s worth a read.

August 19, 2016

Writing a New Obituary for Her Absentee Father

August 10, 2016

One of the Most Important Lessons John Piper Learned in the Pursuit of Racial and Ethnic Harmony and Diversity

This may be my favorite section from John Piper’s book, Bloodlines: Race, Cross, and the Christian (Crossway, 2011): 232-33.

No lesson in the pursuit of racial and ethnic diversity and harmony has been more forceful than the lesson that it is easy to get so wounded and so tired that you decide to quit. This is true of every race and every ethnicity in whatever struggle they face. The most hopeless temptation is to give up—to say that there are other important things to work on (which is true), and I will let someone else worry about racial issues.

The main reason for the temptation to quit pursuing is that whatever strategy you try, you will be criticized by somebody. You didn’t say the right thing, or you didn’t say it in the right way, or you should have said it a long time ago, or you shouldn’t say anything but get off your backside and do something, or, or, or. Just when you think you have made your best effort to do something healing, someone will point out the flaw in it. And when you try to talk about doing better, there are few things more maddening than to be told, “You just don’t get it.” Oh, how our back gets up, and we feel the power of self-pity rising in our hearts and want to say, “Okay, I’ve tried. I’ve done my best. See you later.” And there ends our foray into racial harmony.

My plea is: never quit. Change. Step back. Get another strategy. Start over. But never quit. Langston Hughes, one of the twentieth century’s most notable African American poets, expressed the cry for not giving up like this (titled “Mother to Son”):

Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor— Bare.

But all the time

I’se been a-climbin’ on,

And reachin’ landin’s,

And turnin’ corners,

And sometimes goin’ in the dark

Where there ain’t been no light.

So boy, don’t you turn back.

Don’t you set down on the steps

‘Cause you finds it’s kinder hard.

Don’t you fall now—

For I’se still goin’, honey,

I’se still climbin’,

And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

To white or black—or any other race or ethnicity—that is my plea. I’m not saying you have to make it the number-one emphasis of your life. Some are called to that. Not all. But I am saying to make it an emphasis of your life. Again Shelby Steele, in his stirring book The Content of Our Character, issues the call in words that I find very moving.

What both black and white Americans fear are the sacrifices and risks that true racial harmony demands. This fear is the measure of our racial chasm. And though fear always seeks a thousand justifications, none is ever good enough, and the problems we run from only remain to haunt us. It would be right to suggest courage as an antidote to fear, but the glory of the word might only intimidate us into more fear. I prefer the word effort—relentless effort, moral effort. What I like most about this word are its connotations of everydayness, earnestness, and practical sacrifice.

Amen. Earnest, practical, everyday effort. What I have tried to do in this book is show that the gospel of Jesus Christ—the death and the resurrection of the Son of God for sinners—is the only sufficient power for this effort, and the only power that in the end will bring the bloodlines of race into the single bloodline of the cross. It is the only power to bring about Christ-exalting harmony, which, in the end, is the only kind that matters, because all things were made through him and for him (Col. 1:16). To his grace, and his name, and his Father be glory forever. Amen.

August 9, 2016

How Can I Learn to Receive—and Give—Criticism in Light of the Cross?

Years ago Alfred Poirier wrote a piece on “The Cross and Criticism“—first published in The Journal of Biblical Counseling (Spring 1999): 16-20—that I think is worth revisiting.

Poirier defines criticism broadly, referring to

any judgment made about you by another, which declares that you fall short of a particular standard.

He writes:

The standard may be God’s or man’s.

The judgment may be true or false.

It may be given gently with a view to correction, or harshly and in a condemnatory fashion.

It may be given by a friend or by an enemy.

But whatever the case, it is a judgment or criticism about you, that you have fallen short of a standard.

Here’s the key point of his analysis:

A believer is one who identifies with all that God affirms and condemns in Christ’s crucifixion.

In other words, in Christ’s cross I agree with God’s judgment of me; and in Christ’s cross I agree with God’s justification of me. Both have a radical impact on how we take and give criticism.

Here are four points that he makes:

1. Learn to critique yourself.

Here are some questions to ask:

How do I typically react to correction?

Do I pout when criticized or corrected?

What is my first response when someone says I’m wrong?

Do I tend to attack the person?

Do I tend to reject the content of criticism?

Do I tend to react to the manner?

How well do I take advice?

How well do I seek it?

Are people able to approach me to correct me?

Am I teachable?

Do I harbor anger against the person who criticizes me?

Do I immediately seek to defend myself, hauling out my righteous acts and personal opinions in order to defend myself and display my rightness?

Can my spouse, parents, children, brothers, sisters, or friends correct me?

2. Ask the Lord to give you a desire to be wise instead of a fool.

Use Proverbs to commend to yourself the goodness of being willing and able to receive criticism, advice, rebuke, counsel, or correction.

Meditate upon these passages: Proverbs 9:9; 12:15;13:10,13; 15:32; 17:10; Psalm 141:5.

3. Focus on your crucifixion with Christ.

While I can say I have faith in Christ, and even say with Paul, “I have been crucified with Christ,” yet I still find myself not living in light of the cross. So I challenge myself with two questions.

If I continually squirm under the criticism of others, how can I say I know and agree with the criticism of the cross?

If I typically justify myself, how can I say I know, love, and cling to God’s justification of me through Christ’s cross?

This drives me back to contemplating God’s judgment and justification of the sinner in Christ on the cross. As I meditate on what God has done in Christ for me, I find a resolve to agree with and affirm all that God says about me in Christ, with whom I’ve been crucified.

4. Learn to speak nourishing words to others.

I want to receive criticism as a sinner living within Jesus’s mercy, so how can I give criticism in a way that communicates mercy to another?

Accurate, balanced criticism, given mercifully, is the easiest to hear—and even against that my pride rebels.

Unfair criticism or harsh criticism (whether fair or unfair) is needlessly hard to hear.

How can I best give accurate, fair criticism, well tempered with mercy and affirmation?

The following attitudes are essential to giving criticism in a godly way:

I see my brother/sister as one for whom Christ died (1 Cor. 8:11; Heb. 13:1).

I come as an equal, who also is a sinner (Rom. 3:9, 23).

I prepare my heart lest I speak out of wrong motives (Prov. 16:2; 15:28; 16:23).

I examine my own life and confess my sin first (Matt. 7:3-5).

I am always patient, in it for the long haul (Eph. 4:2; 1 Cor. 13:4).

My goal is not to condemn by debating points, but to build up through constructive criticism (Eph. 4:29).

I correct and rebuke my brother gently, in the hope that God will grant him the grace of repentance even as I myself repent only through His grace (2 Tim. 2:24-25).

August 8, 2016

The Trailer for the New Animated Short Film, “The Biggest Story” (Narrated by Kevin DeYoung)

Here is a trailer for a 26-minute animated short film, The Biggest Story, written and narrated by Kevin DeYoung, featuring the artwork of award-winning artist Don Clark and the animation of Jorge Rolando Canedo Estrada, with an original score composed by John Poon:

The film is due out in August 2016. The DVD includes a free digital copy and a free two-sided poster. Or you can order just the digital download.

August 4, 2016

A Converation with Phil Ryken about the Darkest Period of His Life: “I Started to Wonder How I Would End It All”

Phil Ryken—the president of Wheaton College—has written a new book called When Trouble Comes.

In this small book, I tell the stories of men and women from the Bible who were in all kinds of trouble—people such as Isaiah, Elijah, Ruth, and Paul. They were weighed down by guilt and shame, suffered the death of loved ones, had family crises, or went through other painful trials that tested their faith. For some, the trial was absolutely a matter of life and death.

But before he tells their stories, he tells his own story from a few years ago. Here’s a paragraph from it:

I could tell that I was in a downward spiral. One day I said to myself: “You know, I understand why people kill themselves. This is how they feel. It seems like the only way out.” A few days later, I started to wonder how I would end it all, if, you know . . . It wasn’t a thought I wanted to have, but Satan was after me. Give him any little chance and he will take it. Things were moving in a bad direction, and at the rate they were going, how long would it be before I was in real danger?

I sat down with Dr. Ryken recently to ask him to tell me more about this period of time in his life, and how the president of a Christian college with a PhD in historical theology who seemingly has everything all together can begin to doubt God’s love for him:

Crossway has provided some timestamps for our conversation:

00:00 – Why did you decide to include the story of your own personal troubles in your new book?

1:37 – How serious was the suffering you faced?

2:49 – Can you tell us about how you began to doubt the Lord’s love for you?

3:45 – What did the Lord use to bring you out of your season of suffering?

5:10 – What is your book all about? What is its format?

6:30 – What struggles did the prophet Jeremiah face, and what lessons can we learn from his story?

8:32 – Are there common themes that surface among biblical figures who faced trouble?

10:11 – How do you envision people using your book?

“Written by a sufferer who is also a skilled theologian-exegete, this book is honest, tender, full of grace, and bursting with the street-level wisdom of God’s Word. With story after story from Scripture, Dr. Ryken shows how the Bible accurately portrays our sufferings and how God meets us in the midst of them. Since suffering really is a universal human experience between the ‘already’ and the ‘not yet,’ this is a book worth getting and living with. I found it to be enormously helpful, and you will too.”

Paul David Tripp, President, Paul Tripp Ministries; author, What Did You Expect?

“When trouble comes, most Christians want to escape it, deny or divorce it, or medicate or avoid it—we do everything but actually try to live with it! Thankfully, Dr. Ryken takes great pains in this remarkable book to show us how to live gladly and gloriously through our troubles. Rather than take us on a detour around our hardships, he serves as our guide through them. If you are finding it hard to ‘welcome trials as friends,’ this is the book for you.”

Joni Eareckson Tada, Founder and CEO, Joni and Friends International Disability Center

“When Trouble Comes is a profound book for people in profound trouble. We don’t need to go looking for it, of course. Sooner or later, some life-altering catastrophe that only God can get us through crashes into our lives. And God does help us, very wonderfully, as we fall into his loving arms. Dr. Ryken, a man I highly respect, gently shows us from the Bible how God cares for us when our very lives are on the line. May the Lord bless you as you read this encouraging book, even as he has blessed me.”

Raymond C. Ortlund Jr., Lead Pastor, Immanuel Church, Nashville, Tennessee

You can find more info about the book, including the table of contents and sample material, here.

(At time of writing, the book is only $7.42 at Amazon.)

July 27, 2016

Two Ways that Evangelicals Have Failed Women—And How a New Book Can Help

Karen Swallow Prior—professor of English at Liberty University and the author of Fierce Convictions: The Extraordinary Life of Hannah More: Poet, Reformer, Abolitionist—wrote the foreword for historian Michael Haykin’s new book, Eight Women of Faith (Crossway, 2016):

Genesis 2 tells us that God created a garden with “every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” (v. 9). God told Adam to eat freely of every tree except one. But rather than focusing on the abundance God had offered freely, Adam and Eve turned their focus on the single thing that was off-limits. And the rest is human history.

Both within the church and outside it, we too have treated in a similar fashion the biblical admonition against women preaching: we focus on the single thing that is off-limits and thereby fail to see the abundant opportunities and roles God has clearly offered, some of which are compellingly portrayed in the stories presented in this book. Likewise, the biblical admonition has led too often to extrabiblical limitations on women, as well as unbiblical oppression, also reflected in the societal restraints these eight women experienced during their lives. This kind of failure toward women—unjustly imposed limitations on their personhood and soul equality—has sometimes led to a secondary failure: the failure to see and tell women’s stories clearly, truthfully, and well.

Thus, there exists an abundance of works on the lives of women in the church that present readers with unrealistic saints, not flesh- and-blood women. Such accounts make good fairy tales but not just or suitable examples of the true life of faith. On the other hand, much of today’s retrospectives on women in history tend to focus, understandably and sometimes rightly, on limitations placed on women. Women have been and still are denied much, both in the church and in the culture at large.

This book’s snapshots of a mere eight women from a mere two centuries offer an astonishing array of roles and achievements by women in a time when women were not so much second-class citizens as not citizens at all. Yet despite (and perhaps because of) such obstacles, what women have contributed and accomplished is rich and varied. Here in these pages we meet queen, wife, theologian, hymnist, novelist, missionary, daughter, and friend. Even more importantly, we meet women of faith whose lives manifested the grace and glory of God through their faithful obedience to the roles to which they were called, whether in singleness or marriage, in sickness or in health, in riches or in poverty, and, ultimately, in death.

The facets of womanhood represented in Eight Women of Faith shine brilliantly. This abundance is particularly striking within the early modern era represented by the lives detailed here. The period hinges on a significant turning point in both human history and church history: the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation’s emphasis on faith alone and Scripture alone gave birth to the modern individual (and thus the evangelical tradition)—and it is the lives of women that most clearly reflect the dramatic historical shifts that took place as a result. It is women of faith, particularly evangelical faith (with its emphasis on individual salvation), who mirror most clearly this great shift in human history and culture that elevated human agency and equality. These developments drew me to my own study on an evangelical woman of this era, Hannah More, the British poet, abolitionist, and reformer of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries—and they drew me to this fascinating work as well.

The portraits Haykin paints of these wildly different women reduce them neither to their roles nor to their religion, but rather show how their faith informed, shaped, and fulfilled their earthly callings. Furthermore, regardless of their relationships to men (single, married, wife, daughter, mother), the women are presented as individuals in their own right, as influenced as they are influential in the roles they fill. Margaret Baxter and Sarah Edwards, for example, are shown as faithful servants of the gospel who are as much served by as servants to their respective husbands, Richard Baxter and Jonathan Edwards. The theology embodied by the written works of Anne Dutton, Anne Steele, and Jane Austen models the abundance in God’s garden: we can obey the command not to eat the forbidden fruit and still enjoy a feast abundant enough to nourish all of the faithful.

The lives here demonstrate the truth of Jane Austen’s words, applicable to men and women equally, that “Christians should be up and doing something in the world.” The women in this book, each in her own way, did just that. After reading about them, you will want to, too.

Here is the table of contents for Haykin’s book:

The Witness of Jane Grey, an Evangelical Queen

“Faith Only Justifieth”

Richard Baxter’s Testimony about Margaret Baxter

“Ruled by Her Prudent Love in Many Things”

Anne Dutton and Her Theological Works

“The Glory of God, and the Good of Souls”

Sarah Edwards and the Vision of God

“A Wonderful Sweetness”

Anne Steele and Her Hymns

“The Tuneful Tongue That Sung . . . Her Great Redeemer’s Praise”

Esther Edwards Burr on Friendship

“One of the Best Helps to Keep Up Religion in the Soul”

Ann Judson and the Missionary Enterprise

“Truth Compelled Us”

The Christian Faith of Jane Austen

“The Value of That Holy Religion”

You can read an excerpt here.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers