Justin Taylor's Blog, page 47

October 24, 2016

An Evening with G.K. Chesterton

Dr. John “Chuck” Chalberg has a unique vocation: attempting to bring to life historical figures. He began doing historical impersonation-characterizations of Theodore Roosevelt and H.L. Mencken as an extension of his teaching of American History at Normandale Community College in Bloomington, Minnesota.

Since that time he has added George Orwell, Branch Rickey, Bobby Jones, and Patrick Henry.

Below is a performance he gave as G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) at the Acton Institute on October 23, 2014:

You can listen below to an audio recording of the real G.K. Chesterton from July of 1933 in London, where he gave a toast to Rudyard Kipling at a luncheon given by the Royal Society of Literature for the Canadian Authors’ Association.

October 21, 2016

The Triumphal Procession in Christ: How the Conquering God Reveals Himself by Leading the Apostle Paul to His Death

“But thanks be to God, who in Christ always leads us in triumphal procession, and through us spreads the fragrance of the knowledge of him everywhere.”

—The Apostle Paul, c. A.D. 55/56, in 2 Corinthians 2:14 (ESV)

Scott Hafemann, reader in New Testament studies at the University of St Andrews, has a very helpful explanation on the background of the Roman triumphal procession in the ancient world, which ends up making sense of this perplexing and fascinating passage.

The triumphal procession was a lavish parade conducted in Rome to celebrate great victories in significant military campaigns.

Like a St. Patrick’s Day parade in Chicago, these were major cultural and civic events. Everybody in the Roman Empire knew about these parades, which were represented on Roman arches, reliefs, coins, statues, medallions, paintings, and cameos, not to mention the approximately 350 triumphs that are recorded in ancient literature.

They were ostentatious celebrations, filled with valiant soldiers, the spoils of war, and the most theatrical pomp and circumstances Rome could muster.

Moreover, the triumphal procession demonstrated Rome’s prowess as the victor not only by parading the spoils of war, but also by leading in triumph the most important leaders and intimidating warriors of the enemy, now presented as conquered slaves.

The highest honor any Roman Caesar or general could receive would be to lead one of these parades. Conversely, to be led as a prisoner in such a triumphal procession signaled one’s utter defeat. . . .

[T]he role of those led in triumph was to reveal the glory of the one who had conquered them, ultimately through their public execution and death. . . .

At the end of the parade, the Romans publicly slaughtered as a sacrifice to their god(s) those prisoners who had been led in procession (or at least a representative sample thereof, selling the rest into slavery). Though a gruesome thought to us, what better way to magnify one’s victory, while at the same time offering a sacrifice of gratitude to the gods, than to kill publicly the leaders and the most valiant of the vanquished warriors as the final act of triumph over them?

Hafemann points out that what was is so startling about 2 Corinthians 2:14 is that the Apostle Paul is the direct object, not the subject, of the Greek verb Greek, thriambeuo (“leads us in triumphal procession”).

In other words, “Paul is not the one leading the triumphal procession; he is the one being led in it like a prisoner of war!”

By using this well-known cultural event to describe his own life as an apostle, Paul’s point is that, as the one “being led in triumph,” God is leading Paul to his death. . . .

As the enemy of God’s people, God had conquered Paul at his conversion call on the road to Damascus and was now leading him, as a “slave of Christ” (his favorite term for himself as an apostle), to death in Christ, in order that Paul might display or reveal the majesty, power, and glory of God, his conqueror. . . .

. . . Paul’s suffering, as the corollary to and embodiment of his message of the cross, is the very thing God uses to make himself known. . . . Far from calling his apostleship into question, Paul’s point in 2:14 is that his suffering, here portrayed in terms of being led to death in the Roman triumphal procession, is the means through which God is revealing himself. . . .

In other words, God continually leads Paul to death in a triumphal procession and in this way everywhere reveals the knowledge of him.

— Scott J. Hafemann, 2 Corinthians, NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000), 107-10.

October 17, 2016

Do You Know the Difference Between the “Active” and “Passive” Obedience of Christ?

A common evangelical mistake is to gloss the “active obedience” of Jesus as his “sinless life,” and his “passive obedience” as his “atoning death.”

The distinction, then, is in terms of both mode and timing: Jesus was actively obedient in his living and fulfilling the law’s demand, and he was on the receiving end of the suffered he endured in his dying, which paid sin’s penalty.

But historically, that is not exactly what the terms mean—though some popular defenders of the Reformed view occasionally make this mistake, whether through ignorance or oversimplification.

Historically, the Reformed understanding is that Christ’s “passive obedience” and his “active obedience” both refer to the whole of Christ’s work. The distinction highlights different aspects, not periods, of Christ’s work in paying the penalty for sin (“passive obedience”) and fulfilling the precepts of the law (“active obedience”).

Louis Berkhof puts it in his standard Systematic Theology:

The two accompany each other at every point in the Saviour’s life. There is a constant interpretation of the two. . . .

Christ’s active and passive obedience should be regarded as complementary parts of an organic whole. (pp. 379, 380)

John Murray, in Redemption—Accomplished and Applied, expresses it quite clearly and goes into more detail:

[We cannot] allocate certain phases or acts of our Lord’s life on earth to the active obedience and certain other phases and acts to the passive obedience.

The distinction between the active and passive obedience is not a distinction of periods. It is our Lord’s whole work of obedience in every phase and period that is described as active and passive, and we must avoid the mistake of thinking that the active obedience applies to the obedience of his life and the passive obedience to the obedience of his final sufferings and death.

The real use and purpose of the formula is to emphasize the two distinct aspects of our Lord’s vicarious obedience. The truth expressed rests upon the recognition that the law of God has both penal sanctions and positive demands. It demands not only the full discharge of its precepts but also the infliction of penalty for all infractions and shortcomings. It is this twofold demand of the law of God which is taken into account when we speak of the active and passive obedience of Christ. Christ as the vicar of his people came under the curse and condemnation due to sin and he also fulfilled the law of God in all its positive requirements. In other words, he took care of the guilt of sin and perfectly fulfilled the demands of righteousness. He perfectly met both the penal and the preceptive requirements of God’s law. The passive obedience refers to the former and the active obedience to the latter. (pp. 20-22; my emphasis)

Put another way, Jesus’ so-called “passive” and “active” obedience were lifelong endeavors as he fulfilled the demands and suffered the penalties of God’s law, and both culminated in the cross.

Though some critics of Reformed theology critique the distinction as extrabiblical, I think the New Testament clearly teaches both aspects: the lifelong passive obedience of Christ (his penalty-bearing work of suffering and humiliation) and the lifelong active obedience of Christ (his will-of-God-obeying work) culminate in the cross. Those who trust in him and are united to him do not just have his active obedience credited to their account; nor do they just have his passive obedience credited to their account. The Bible doesn’t divide his obedience up in this way. Rather, believers are recognized as righteous through the imputation of the whole obedience of Christ (the reckoning of Christ’s complete work to our account).

In other words, confessionally Reformed folks argue for both-and, not either-or. In the New Testament, Christ’s righteous work is of one cloth: it’s always “obedience unto death.” One cannot separate Christ’s fulfillment of God’s precepts from Christ’s payment of the penalty for our failing to obey God’s precepts.

October 13, 2016

On the Future of Christian Hedonism

This past weekend in Minneapolis, several pastor-scholars associated with Bethlehem College & Seminary gathered to speak on the future of “Christian hedonism,” a term coined by John Piper in his 1986 book Desiring God.

In the first talk, Piper proposed a refined definition of “Christian hedonism”:

Since God is most glorified in us when we are most satisfied in him, therefore, in everything we do, we should always be pursuing maximum satisfaction in God and striving to take as many people with us into that satisfaction as we can, even if it costs us our lives.

Piper went on to give eight biblical reasons for believing in Christian hedonism, and then fifteen dreams for the future of it.

Ryan Griffith sat down with Piper, along with Sam Storms, to discuss the future of Christian hedonism in more depth.

You can watch the talk and the conversation below:

To watch or listen to all of the messages—including Piper on his dreams for the future of Christian hedonism, Storms on our Father’s call for us to be joy-filled children, DeRouchie on the book of Ecclesiastes, and Rigney on C.S. Lewis—go here.

October 11, 2016

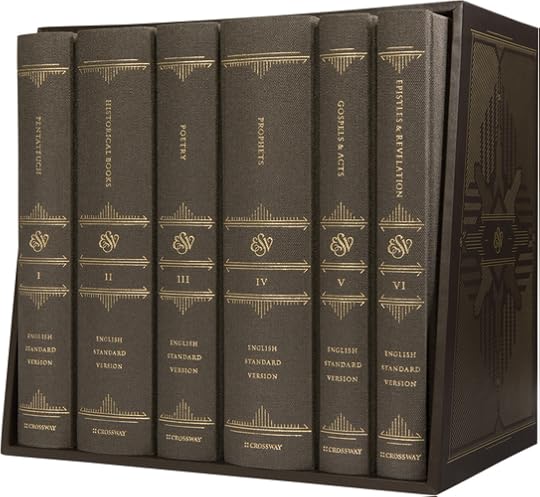

The New ESV Reader’s Bible: Six-Volume Set

Crossway has now published the six-volume ESV Reader’s Bible.

Here is the publisher’s description:

The ESV Reader’s Bible, Six-Volume Set stems from the conviction that the Bible is of immeasurable value and should therefore be treasured—and read in the most seamless way possible.

Constructed with materials carefully selected to reflect the beauty of God’s Word, the ESV Reader’s Bible, Six-Volume Set is a unique collection designed for those desiring a cleaner, simpler Bible-reading experience.

Printed on European book paper with smyth-sewn binding and packaged in an elegant slipcase, this edition features single column text that is free of all verse numbers, chapter numbers, and footnotes, as well as most section headings—resulting in a unique Bible-reading experience that helps readers encounter and delight in the beauty of God’s Word.

Here are the features:

Black letter text

Single-column, paragraph format

No verse numbers, chapter numbers, or footnotes

Reduced section headings

Printed on high-quality European book paper

Divided into six volumes:

Pentateuch

Historical Books

Poetry

Prophets

Gospels & Acts

Epistles & Revelation

Ribbon markers

Smyth-sewn binding

Packaging: Heavy slipcase

WTS is currently selling the entire set for 50% off, so you can get it for less than $100.

For an in-depth review, which is still ongoing, see J. Mark Bertrand:

Part 1: Simply Beautiful

Part 2: Layout & Typography

Here is a video about this new Bible:

October 6, 2016

Lying about Hitler: An Interview with Historian Richard Evans

The new film Denial is now in limited release and will be in theaters around the US by October 21, 2016 and in the UK in February of 2017.

The movie stars Rachel Weisz as American historian Deborah Lipstadt, Timothy Spall as Holocaust denier and Hitler apologist David Irving, and Tom Rampton as barrister Richard Rampton.

It is based on a true story of the trial of David Irving v Penguin Books and Deborah Lipstadt (2000) as recounted in Lipstadt’s 2005 book, History on Trial: My Day in Court with a Holocaust Denier (2005).

It began when Lipstadt, who teaches Jewish history at Emory University, referred to Irving as “one of the most dangerous spokespersons for Holocaust denial,” accusing him of manipulating historical evidence for his nefarious ends, in her book Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (1993). She was certainly not the only one to make such accusations, but she was the one he chose to sue for libel in English court (a British edition of her book had been published in the UK, making the suit possible).

As the trial judge explained, “It is not incumbent on defendants to prove the truth of every detail of the defamatory words published: what has to be proved is the substantial truth of the defamatory imputations published about the claimant.” In other words, in order to defend herself in the suit, Lipstadt’s lawyers had to show that what she said was accurate—namely, that Irving really did distort historical evidence in order to deny the Holocaust.

The defense hired as its star expert witness Sir Richard J. Evans, a noted historian of modern Europe who was a professor at the University of Cambridge and who specialized in German history. Since the trial, Evans has gone on to produce a landmark trilogy on the history of the Third Reich (2003, 2005, 2008).

Soon after the trial, Irving published a book entitled Lying about Hitler: History, Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial (2001), a page-turning work. It can be thought of as an extended illustration of his book In Defense of History (1997), which critiqued postmodern skepticism about the possibility of historical knowledge. Lying about Hitler offers readers a unique angle on the careful inductive work of a responsible historian and the painstaking refutation of irresponsible work.

I recently corresponded with Professor Evans, who serves today as President of Wolfson College and Regius Professor Emeritus of History, University of Cambridge, and Provost of Gresham College in London.

Historian Richard Evans (L) played by actor John Sessions (R).

Was there a time in which David Irving was considered a respectable historian? Didn’t Christopher Hitchens used to say that he was ”one of the three or four necessary historians of the Third Reich”?*

Hitchens later changed his mind when he discovered Irving’s racism. Irving was considered a ‘controversial’ historian who performed a service in digging up previously unknown sources on Nazi Germany. He was considered eccentric or perverse in his attitude to Hitler but did not move beyond the pale until he became a hard-line Holocaust denier in the late 1980s.

Even though it was Irving who sued Lipstadt, some people defended Irving’s right for free speech as if he were the victim or the one on trial. How could the public have been so confused about the nature of this well-publicized case?

This is because the defence’s tactic was to focus on Irving, repeat Lipstadt’s accusations at much greater length, and back them up with overwhelming evidence.

Had he won, the freedom of speech would have been seriously damaged in the UK. Even though he lost, I still had major problems publishing my book on the case because publishers were afraid he would sue them. The movie makes it clear what was at stake.

Your In Defense of History, in which you argued for the possibility of historical knowledge, had published just a few years before being asked to be the lead expert witness. Was Lipstadt’s counsel looking for someone with not only a command of German history but also someone who had done serious work on issues of historiography and epistemology?

Yes; not his counsel but his solicitor, Anthony Julius, who instructed his counsel, Richard Rampton QC.

How long did it take you to do research preparations for your expert testimony, and how long did the actual trial last?*

Preparations with two researchers took from January 1998 to July 1999. The trial lasted from 11 January 2000 to 11 April 2000.

Was the eventual verdict ever in doubt for you?

No, the only question was by how much the defence would win. In the event, the victory was comprehensive.

In theological circles, we sometimes say that *all* who speak and write about God are “theologians”—there are just “good theologians” and “bad theologians.” Some might say the same for those who write about history: they are “historians,” whether for good or for ill. Yet in Lying about Hitler, you suggest that Irving should not be labeled a “historian.” Why?

Because he lacks the facility of recognizing when documentary evidence goes against his theories or arguments. If they do, he manipulates distorts or ignores them.

Bear in mind, however, that the judge said I was wrong to say he was not a historian because Sir John Keegan in particular said he was.

How is is that reputable, professional historians, seeking to be objective and working with the same evidence, can come to varied conclusions?

A distinction must be made between fact and argument, even if it is not always very clear. The evidence poses the limits within which interpretations are possible.

One of my favorite sections of Lying about Hitler is where you compare historians to figurative painters sitting at various places around a mountain. Could you repeat the comparison here

The figurative painters paint the mountain “in different styles, using different techniques and different materials, they will see it in a different light or from a different distance according to where they are, and they will view it from different angles. They may even disagree about some aspects of its appearance, or some of its features. But they will all be painting the same mountain. If one of them paints a fried egg, or a railway engine, we are entitled to say that she or he is wrong; whatever it is that the artist has painted, it is not the mountain. The possibilities of legitimate disagreement and variation are limited by the evidence in front of their eyes.

“An objective historian is simply one who works within these limits. They are limits that allow a wide latitude for differing interpretations of the same document or source, but they are limits all the same.”

It’s not often that a living historian is portrayed by an actor in a film about a trial that has to do in part with the epistemology and objectivity of responsible historiography! Assuming you have seen the film, do you have any thoughts on the historical accuracy of the movie itself, recognizing that the dramatic needs and the compressed timeframe for the story lead many screenwriters to play fast and loose with the details?

I have not seen the movie, which is not being released in the UK till February. I have, however, read the screenplay, which sticks very closely to the record, particularly the trial transcripts, and where it deviates from it, for dramatic effect, I don’t think it betrays the spirit in which the case was fought.

[Note from JT: the screenwriter has written about the process of sticking closely to the historical record.]

Can you tell us a bit about your latest book, now published in the UK and due out in the US in November, on The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914?

This is a comprehensive, large-scale history of Europe in the 19th century focusing on politics, economy, society and culture, set in the global context of Europe’s relations with the wider world in a period when it dominated the globe. It includes many portraits of individuals, mostly ordinary people, quotes and anecdotes to make the period come alive in all its mixture of strangeness and familiarity.

What are you working on next?

I am writing a biography of the historian Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012), with the support of his family and access to his papers.

September 29, 2016

How to Pray a Psalm

A practical illustration from Don Whitney’s little book, Praying the Bible, using Psalm 23:

You read the first verse—“The Lord is my shepherd”—and you pray something like this:

Lord, I thank you that you are my shepherd. You’re a good shepherd. You have shepherded me all my life. And, great Shepherd, please shepherd my family today: guard them from the ways of the world; guide them into the ways of God. Lead them not into temptation; deliver them from evil. O great Shepherd, I pray for my children; cause them to be your sheep. May they love you as their shepherd, as I do. And, Lord, please shepherd me in the decision that’s before me about my future. Do I make that move, that change, or not? I also pray for our under-shepherds at the church. Please shepherd them as they shepherd us.

And you continue praying anything else that comes to mind as you consider the words, “The Lord is my shepherd.” Then when nothing else comes to mind, you go to the next line: “I shall not want.” And perhaps you pray:

Lord, I thank you that I’ve never really been in want. I haven’t missed too many meals. All that I am and all that I have has come from you. But I know it pleases you that I bring my desires to you, so would you provide the finances that we need for those bills, for school, for that car?

Maybe you know someone who is in want, and you pray for God’s provision for him or her. Or you remember some of our persecuted brothers and sisters around the world, and you pray for their concerns.

After you’ve finished, you look at the next verse: “He makes me lie down in green pastures” (v. 2a). And, frankly, when you read the words “lie down,” maybe what comes to mind is simply, “Lord, I would be grateful if you would make it possible for me to lie down and take a nap today.”2

Possibly the term “green pastures” makes you think of the feeding of God’s flock in the green pastures of his Word, and it prompts you to pray for a Bible teaching ministry you lead, or for a teacher or pastor who feeds you with the Word of God. When was the last time you did that? Maybe you have never done that, but praying through this psalm caused you to do so.

Next you read, “He leads me beside still waters” (v. 2b). And maybe you begin to plead,

Yes, Lord, do lead me in that decision I have to make about my future. I want to do what you want, O Lord, but I don’t know what that is. Please lead me into your will in this matter. And lead me beside still waters in this. Please quiet the anxious waters in my soul about this situation. Let me experience your peace. May the turbulence in my heart be stilled by trust in you and your sovereignty over all things and over all people.

Following that, you read these words from verse 3, “He restores my soul.” That prompts you to pray along the lines of:

My Shepherd, I come to you so spiritually dry today. Please restore my soul; restore to me the joy of your salvation. And I pray you will restore the soul of that person from work/school/down the street with whom I’m hoping to share the gospel. Please restore his soul from darkness to light, from death to life.

You can continue praying in this way until either (1) you run out of time, or (2) you run out of psalm. And if you run out of psalm before you run out of time, you simply turn the page and go to another psalm. By so doing, you never run out of anything to say, and, best of all, you never again say the same old things about the same old things.

So basically what you are doing is taking words that originated in the heart and mind of God and circulating them through your heart and mind back to God. By this means his words become the wings of your prayers.

September 26, 2016

“Choose You This Day Whom You Will Serve” (Or, The Problem with Christian Wall Art)

Greg Koukl says that Christians should Never Read a Bible Verse:

If there was one bit of wisdom, one rule of thumb, one single skill I could impart, one useful tip I could leave that would serve you well the rest of your life, what would it be? What is the single most important practical skill I’ve ever learned as a Christian?

Here it is: Never read a Bible verse. That’s right, never read a Bible verse. Instead, always read a paragraph at least. . .

The key to the meaning of any verse comes from the paragraph, not just from the individual words. . . .

It’s the most important practical lesson I’ve ever learned . . . and thing single most important thing I could ever teach you.

Let’s take, for example, Joshua 24:15. It is not uncommon to see inspirational Christian art that quotes the verse as follows:

Choose this day whom you will serve . . .

But as for me and my house, we will serve the LORD.

The problem, we could say, is with the ellipses: the dots that indicate that something has been left out. In fact, there should be ellipses before “choose this day” as well, since this is halfway through a sentence.

Here is the passage with the complete sentences, starting with verse 14:

[14] Now therefore fear the LORD and serve him in sincerity and in faithfulness.

Put away the gods that your fathers served beyond the River and in Egypt, and serve the LORD.

[15] And if it is evil in your eyes to serve the LORD, choose this day whom you will serve, whether the gods your fathers served in the region beyond the River, or the gods of the Amorites in whose land you dwell.

But as for me and my house, we will serve the LORD.

In context, Joshua has just relayed to the tribes of Israel gathered at Shechem a message from YHWH, their covenant Lord, giving a history lesson of how their forefathers had served other gods until the one true God rescued them out of Egypt and brought them to the Promised Land.

In verse 14, Joshua begins drawing a conclusion from what YHWH has said: positively, they are to fear YHWH, serving him faithfully and sincerely (14a).

Negatively, and conversely, they are to put away the false rival gods that their ancestors served.

Then, in verse 15, Joshua provides an “if-then” clause.

If you Israelites determine that serving YHWH is evil,

then go ahead and make your choice of what kind of gods you’re going to choose: the false gods from the past beyond the River, or the false gods of the Amorites in your current location.

In contrast to this, Joshua says, he and his house are going to serve YHWH.

To recap, then, when Joshua says “choose this day whom you will serve,” he’s not talking about serving YHWH here. He’s speaking rhetorically about what they should do if they have already rejected YHWH—choose which set of pretender gods you want follow.

Now, does this interpretation make a major difference to how a Christian lives his or her life? No. It’s more like “the right doctrine from the wrong text.” The more we quote something like “choose ye this day whom you will serve” out of context, the more it suggests that we have memorized or picked up certain wording but failed to pay attention to or meditate upon the context and flow of how YHWH has revealed his actual words and arguments to his covenant people.

September 9, 2016

The Stories of Two Barths: Chaser or Gateway Drug?

The following is a guest post Michael Allen, associate professor of systematic and historical theology at Reformed Theological Seminary in Orlando, Florida. He has written a number of books including Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics: An Introduction and Reader (London: T & T Clark, 2012).

My theological twin, Scott Swain, recently tweeted:

My theological twin, Scott Swain, recently tweeted:

It’s important for Protestant theologians to get Karl Barth and to get over Karl Barth.

Apparently this was controversial, as it kicked up some rather excited demurral. I’m not on twitter, but Scott’s tweet makes me wish (momentarily) that I was. It’s brilliant in both its distinct points: Get Barth. And, yes, get over Barth. Punchy, but wise. But it’s also not surprising that it drew such ire, and I want to explore why.

Two narratives shape how one thinks of Karl Barth and his theology, at least among those who view him as a relative good of significant note.[1]

If one reads Barth in one story, then getting over him would be futile.

If one reads him as part of another story (which I deem more plausible), then doing so makes all the sense in the world.

Admittedly the stories are somewhat too neat, but I do believe they prove instructive just the same.

The First Story: Barth Is the Chaser that Ends the Party

Narrative number one involves a story of the onward progress of the Word of God. I emphasize that final prepositional phrase (“of the Word of God”) because I do not take these persons to be beholden to belief in modern progress as such. They honestly claim that God—and God alone—will lead his people to ever-greater illumination regarding his Word. Following the fundamental principles of the Protestant Reformation, then, they expect the church to be continually reformed by God’s Word. Note, the church does not reform itself, for progress is not a matter of optimism in one’s intrinsic capacities; rather, God reforms the church through his Word. They believe God to be active, his Word to be powerful, and thus they expect doctrinal progress (alongside other forms of progress, no doubt, ranging from the moral and social to liturgical and ecumenical).

What progress do they affirm? Barth clearly offers so much here: theological realism, a scripture-soaked imagination, a Christ-centered particularism, conversation with a wide-ranging litany of Christian witnesses from the tradition, a vivid sense of the singularity of Jesus and the grace of his work. We could list still more gains. Further, they note that Barth offered this in the modern era, attesting the gospel in a (more advanced) cultural setting. While they may not buy into modern progress as a philosophy, they do believe we cannot turn back the clock on philosophical and cultural developments even though we must see how the gospel sublimates them. Thus, they take it as rather strange that one would seek to “get over Karl Barth” unless one is claiming to want to move forward to something still more contemporary (say, T. F. Torrance or, for the slightly more exotic, Wolf Krötke or Helmut Gollwitzer). In this narrative, Barth signals the latest significant advance of the active Word of God, received thoughtfully by his servants, and he beckons us come to him. This is the first story of Barth.

The Second Story: Barth Is a Gateway Drug to Something More

But there is another story of Barth, which I deem to be more viable and convincing.

Narrative number two affirms those basic principles but contextualizes them within a story of marked decline. The advance of God’s Word by his Spirit’s power nonetheless runs its course through a human and even ecclesial history that manifests twists and turns, struggles and sins. The modern era, particularly in Europe, was a time of remarkable decline and of giving up territory in terms of historic orthodoxy. Barth and others confessed as such when he took up the newly established honorary chair in reformed theology at Göttingen. John Webster has traced the way in which Barth worked feverishly in the 1920s at reading not only biblical texts but also the Reformed theological tradition carefully. By the time he turned his hand to the dogmatic task, he was able to steer back towards the realm of historic orthodoxy. In so many ways he returned a focus to exegesis, to conversation with the history of doctrine, and to resolve in speaking in a Christian and theological manner. All the positives mentioned above would be affirmed here as gains, even if sometimes taken as limited gains or intertwined with some problems or at least with some tension-laden supplements. And I might add that other areas are not only returns to earlier achievements but genuinely extend theological reflection in a profound manner worthy of emulation, an example of which I take to be his penetrating focus upon the agency of the exalted Christ.

Perhaps most notably, however, this story observes that Barth saw himself as a theologian doing “church dogmatics” and thinking after the confession of the people of God and, even more signally, receiving the intrusively life-giving Word of God from the outside. They take it as rather straightforward, then, that Barth’s own trajectory would suggest moving in his work and through his witness to the greater fullness of the catholic and Reformed theological tradition where that Word has been heard in even more alert and nuanced ways. A number of examples could be offered, which might likely include a greater desire for a more nuanced rendering of covenant history than the sometimes reductive exegesis offered in CD II/2, to gleaning from the way that (having listened well to Barth) Kate Sonderegger has nonetheless suggested that we better follow the canonical order of teaching by beginning with the oneness of God as was dominant in the classical Reformed and catholic tradition, to more patient attention to the doctrine of creation in its own right (even to Calvin’s teaching on nature and grace on the matter!), and to a number of matters sacramental and scriptural (where, at the end of his life, John Webster was gesturing toward advances beyond Barth). In this narrative, Barth represents a remarkable move towards receiving historic orthodoxy in an intelligent manner yet again in a place where it had been decimated and occasionally a genuine advance on particular topics, but he is fundamentally a witness gesturing us to go still further. Again, Webster serves as an example of one who remained to the end committed to listening and learning respectfully from Barth but who had been led by him to still greater riches in the catholic and Reformed tradition.

A Suggestion

Our posture toward Barth will relate to the story within which we view him. I can’t help but think that the second narrative the more viable, and I observe that the first narrative tends to be convincing to those involved in the professional world of Barth Studies as their major theological interest while the second narrative plays out across the work of a host of figures who respectfully engage with Barth with a still deeper commitment to tracing beyond him ways in which the Christian confession might be thought more fully. Folks such as the late John Webster, Kevin Vanhoozer, Michael Horton, Kate Sonderegger, Fred Sanders, or my colleague Scott Swain come to mind. One would be hard-pressed to find dismissive or ungrateful reflection on Barth in their work, but their gratitude takes the form of taking him seriously enough to delight in going deeper into the tradition and most especially into biblical exegesis than he might have done. In this approach Barth is a gateway drug, we might say, to more in the world of Reformed catholicity in its patristic, medieval, and modern treasures, rather than treating him as a chaser that ends the party.

Two concluding thoughts come to mind by way of suggestion.

First, I have trouble noting these narratives without seeing the first one as possessing a much more vigorous sense that theology is a constructive or poetic practice involving creation as part of its movement and, thus, progress and contemporaneity holding a high prestige. On the other hand, the second model seems to suggest much more of a receptive model, wherein the first mode of theology’s practice and its defining characteristic at every point is its hearing that which has been said. (Of course, Barth himself offers analysis of these two modes of thought in speaking of the hearing and the teaching church.) Without denying the integrity of created being and activity in its intellectual mode, it seems to me that Christian teaching—especially the character of the gospel itself—demands the second posture be treated as more definitive: theology is a positive and receptive task, not a poetic or creative practice. While the Word always confronts us from outside, the theologian is not to be a savant but fundamentally a student who listens ever deeper, ever wider. It is a shame when Barth, who sought to tune our ears to that wider chorus of saints, is left playing solo.

A second observation is also worth our attention. Barth was used to help right some wrongs. We do well to be grateful. Profoundly grateful. His confession was vital. His ministry inspires and informs. He was also put to such work in a setting that was far less theologically resourced than many others today (this is not my judgment alone for, again, he noted as such early in his teaching career!). And, today, I know there are settings that are so bereft of biblical fidelity and Christ-centeredness that his theology would be a remarkable move in the right direction, but others live (thankfully) in settings that have maintained a vibrant biblical and confessional witness (albeit always with limits and failures) wherein embrace of his thought as a whole would involve some declensions. We are wise not to forget that contextual reality. While I would not want my presbytery to take on his theology in its most notable revisions to the catholic and Reformed confessions, I can still read, show gratitude, and celebrate what good was worked in that setting through him.

What of Barth? While we would be foolish to chide him for somehow leading the church astray from an orthodoxy it did not possess at that time in any lively way, we would be equally unwise to pretend that he wasn’t himself grasping for something more than that which he was able to provide. As we should appreciate that he beckoned people unto the Jesus of the Word, perhaps we should also seek go past where he might point us to the still more faithful testimony of others.

Footnote

[1] Two other narratives could be added as possibilities, though I don’t think either worth our worry.

First, some would suggest that Karl Barth brought liberalism into the church like a wolf in sheep’s clothing. It is hard to see the value of such an approach, given that Barth’s church did not need liberalism coming in from outside, for there was plenty within already. He was by all accounts seeking to restore some notion of orthodoxy, even if not arriving quite where one might like in that regard. While some in the USA may have sought to broaden its churches and loosen doctrinal standards by making use of him (e.g. elements in both the Northern and Southern Presbyterian churches prior to their merger as the PC[USA]), that is another matter not attributable to Barth himself. To chide Barth for making the Reformed church broader is like looking at Paul’s biography and noting mainly that he circumcised Timothy rather than the more contextually notable fact that he did not circumcise Titus.

Second, others would suggest that Barth did work to move a liberal church back towards orthodoxy and, thus, was an impediment to the onward march of progressivism. Such liberal or revisionist approaches would demand a much more basic response regarding the nature of the Christian faith, of biblical teaching, and of the commendable value of historic orthodoxy (to whatever degree Barth led there).

September 6, 2016

Why Protestants Need to Use Tradition When They Read Their Bibles

A few of my favorite quotes on the topic:

“It seems odd, that certain men who talk so much of what the Holy Spirit reveals to themselves, should think so little of what he has revealed to others.”

—Charles Haddon Spurgeon, Commenting and Commentaries (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1876), 1.

“Tradition is the fruit of the Spirit’s teaching activity from the ages as God’s people have sought understanding of Scripture. It is not infallible, but neither is it negligible, and we impoverish ourselves if we disregard it.”

—J.I. Packer, “Upholding the Unity of Scripture Today,” JETS 25 (1982): 414

“The best way to guard a true interpretation of Scripture, the Reformers insisted, was neither to naively embrace the infallibility of tradition, or the infallibility of the individual, but to recognize the communal interpretation of Scripture. The best way to ensure faithfulness to the text is to read it together, not only with the churches of our own time and place, but with the wider ‘communion of saints’ down through the age.”

—Michael Horton, “What Still Keeps Us Apart?”

“There is rugged terrain ahead for those who are constitutionally incapable of referring to the paths marked out by wise and spirit-filled cartographers over the centuries.”

—Larry Woiwode, Acts (New York: HarperCollins, 1993).

Theologians Peter Leithart and Brad Littlejohn have recently been having a back-and-forth online on the quest and dangers of novelty in theological exploration and formulation. In citing the following, I am not suggesting that Leithart is ignorant of the dogmatic tradition. But Littlejohn’s extended metaphor is instructive and illuminating, so I wanted to share it in full:

The Word of God is a lamp to our feet and a light to our path, and we should examine every step we take in its light lest we plunge into a pit or tread on a viper. And yet sometimes (most times!) it is useful to be able to see a bit of the broader landscape. This is what the the dogmatic tradition of the church supplies. Think of a systematic theology as being like a map (or, in the case of some of those 17th-century guys, a full-blown atlas), which offers us an overview of the vast and treacherous terrain of trying to speak about our God and who he has called us to be in this world, as it has been revealed by intrepid explorers over two millennia. With the aid of this map, one can quickly gain a sense of the well-traveled paths that are tried-and-true ways of getting to one’s destination, as well as the craggy and unexplored heights which the more adventurous might want to explore one day. It warns one of dead-ends that will end on the edge of a sudden precipice, and of boggy morasses where the unwary pilgrim might lose his way for days or weeks. It shows where one can expect to find friendly shelter and protection among trustworthy comrades, and where one is liable to be waylaid by thieves or lured away by deceivers.

Now imagine someone comes along and declares that ours is a new era, that the landscape has changed so much since the maps were made that it is time to start from scratch and explore anew. Now, he might be right from time to time (for the landscape does slowly change), but one can also imagine him triumphantly declaring that he has discovered a new pass through the mountains when a look at the map (or indeed, the recently-used campsites scattered around him) would tell him that it is one that has been in use for centuries. This would be a foolish error, but a harmless enough one, if he did not also pause to make a speech, deploring the oversights of his predecessors, who had been too blind to discover this wonderful mountain pass—more proof, if any was needed, that their maps should not be trusted. (This, of course, is one of my greatest complaints about Leithart’s Delivered from the Elements—he offers us soteriological insights that are often quite reminiscent of what the Reformers mined from the Scriptures, while telling us over and over how confused and unreliable those Reformers were.) So our intrepid explorer, in his zeal to do something new, would find himself more often than not, doing nothing of the sort.

Not only would such an explorer tend to tread well-worn paths while claiming to be a trailblazer, but when he did succeed in charting new paths, they might not be very good ones, or at any rate very useful at present. They would turn out to be rocky and circuitous, plunging through heavy vegetation so that any trying to follow after would be liable to get lost in the thickets and wander over a nearby precipice. Until our intrepid explorer had succeeded in clearing, smoothing, and signposting this new trail, the majority of pilgrims would be wise to avoid it, whatever its theoretical advantages. So it is with Leithart’s Delivered from the Elements—when it comes to the features of the book that seem most genuinely new (such as Leithart’s theories about “nature” and “natures,” and what it might mean for the church to be a “poststoicheic society”), they are also the most confusing and opaque. The nice thing about the well-worn paths is that they are, well, well-worn. The footprints of thousands of adventurers have crushed the brambles and smoothed out the treacherous bumps. Doctrines that have been refined over centuries, whatever their weaknesses, at least usually have the strength of having gained remarkable clarity (at least, for those patient enough to examine them) and having weathered the barrage of centuries worth of objections, becoming ever more refined through the process. Brand-new doctrines, like brand-new trails, don’t have this advantage. Indeed, they are often hard to make out at all, so that anyone trying to follow in the footsteps of the trailblazer is likely to miss the new path entirely and wander off a cliff. This is not to discourage the important work of trailblazing (whether in mountaineering or in theology); simply to note that any trailblazer needs to recognize that he has a lot of work to do (more than he can probably do single-handed) before he is ready to advertise his trail to the public and say, “Come and follow me!”

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers