Justin Taylor's Blog, page 45

December 30, 2016

How Should We Think about Watching Women Fight Women?

I invited Alastair J. Roberts, author of the big forthcoming book, Heirs Together: A Theology of the Sexes (Crossway, 2017), to share his thoughts about the popular phenomenon of women like Ronda Rousey fighting other women in mixed-martial arts.

Tonight, Ronda Rousey returns to the ring, after last year’s surprising loss to Holly Holm, to fight Amanda Nunes in the UFC.

The Rise of Women in Mixed Martial Arts

Rousey is an important figure in UFC: she was the first to sign with them, was a catalyst for their opening up to women, and has been one of their greatest audience draws.

The commercial success of women in mixed martial arts has been remarkable, with the women’s sport proving more popular in many cases than its male counterpart, albeit still with an overwhelmingly male audience (MMA has one of the greatest disparities in the gender ratio of its audience).

People like to watch women fight.

The female sport just makes sense for UFC. It is a huge money-spinner. It connects with new audiences and increases the interest of existing ones. The curiosity and sex appeal of women fighting is a considerable draw—“easy on the eyes, hard on the face”—and the UFC has foregrounded this in much of its publicity over the last few years.

Including women has also allowed the UFC to develop progressive credentials, improving the reputation of a sport that has had an unwelcome association with domestic abuse and had an exceedingly male-dominated audience. Ronda Rousey has been portrayed as a feminist standard bearer for many, someone who nicely fits the ubiquitous “first X to do Y” scripts that proliferate in the contemporary media.

Men and Fighting

Pugilistic sport has long been viewed as a largely male preserve. This isn’t an accident. The physical differences between men and women in strength and muscularity are exceedingly large. Even the most powerful women seldom exceed average male strength on criteria such as grip strength. As David Puts observes:

Men have about 90% greater upper-body strength, a difference of approximately three standard deviations (Abe et al., 2003; Lassek & Gaulin, 2009).

The average man is stronger than 99.9% of women (Lassek & Gaulin, 2009).

Men also have about 65% greater lower body strength (Lassek & Gaulin, 2009; Mayhew & Salm, 1990), over 45% higher vertical leap, and over 22% faster sprint times (Mayhew & Salm, 1990) . . .

Beyond these huge differences, however, men have always had a much greater propensity toward, aptitude for, and interest in both violence and agonism [=struggle]. Across human societies, the sex differences in this area are displayed in everything from gender ratios in the committing of violent crime, to participation and interest in agonistic sport and competitive activities, to fighting in militaries.

The extent of sexual differences in such areas is an embarrassing fact for a society that would like to neutralize the reality of gender. Continued efforts to include women in modern militaries, for instance, have repeatedly met with entirely predictable setbacks, as the natural reality proves unamenable to our desired social constructions (although new social constructions can provide opportunities to mask this).

Women’s Fighting and Gender Non-Conformity

It is unsurprising that, in activities that swim against the flow of sexual difference, people who are so-called “gender non-conforming” in broader respects should predominate. The term “homosexual” masks the fact, but sexuality is a gender difference, entangled with all sorts of other differences in behavior and interests (over 95% of men are gynephiles [sexually attractive to women or femininity] and over 95% of women are androphiles [sexually attracted to men or masculinity).

Androphilic men exhibit many commonalities with women and gynephilic women many commonalities with men (for instance, lesbians are hugely overrepresented in prisons and perform much more like men when it comes to the earnings gap, preferring higher wage, male-dominated jobs). The authors of an important recent review of science on the subject of sexual orientation observed:

Shared interests and personality characteristics beyond a common sexual orientation likely facilitate the formation of such subcultures. Same-sex-attracted individuals often have more in common with each other, even when they come from disparate cultures, than they do with their larger culture, in part because of gender nonconformity (Norton, 1997; Whitam & Mathy, 1986). For example, across cultures, androphilic men tend to be more female-typical and “people-oriented” in their interests compared to gynephilic men; conversely, gynephilic females tend to be more male-typical and “thing-oriented” than androphilic females (Cardoso, 2013; Lippa, 2008; L. Zheng et al., 2011). Not surprisingly, androphilic males in many cultures worldwide share interests pertaining to the house and home, decoration and design, language, travel, helping professions, grooming, and the arts and entertainment (Whitam & Mathy, 1986).

Opening up the UFC to women has put it on a front line of the wider cultural war against gender difference, perhaps most notably seen in the controversy surrounding Fallon Fox, an openly transsexual competitor in its featherweight division. A large number of UFC fighters have also come out as lesbians: Amanda Nunes, Liz Carmouche, Aisling Daly, Jessica Andrade, Raquel Pennington, Tonya Evinger, etc.

The Public Appetite for Fighting Women

There is a significant appetite among the public for “kicka*s women,” perhaps especially seen in the trope of the “strong female character,” typically a thin, underdressed, conventionally attractive young woman who can comfortably beat up men much larger than her [think Jennifer Garner as Sydney Bristow in Alias, for example]. Such women exemplify the virtues of much contemporary feminism and gender theory, which commonly seek to deny the reality of sexual difference, overturn all gender norms, and disproportionately celebrate women who achieve in traditionally male activities or contexts. Kicka*s women improve the “representation” of women in male-dominated realms and are frontline heroes from the ongoing war against the patriarchy.

Young and attractive kicka*s women hold a great appeal for many men too. Not only are they nice to look at, they can also relieve men of some of the burdensome sense of duty to treat women differently from men, to be gentler towards them, to protect them, to accord them particular honor, to be mindful of the advantages they generally enjoy naturally over women in power and agency, and to recognize the fact that women and men have many deeper differences in personality, behavior, and interests. Such representations of women can play into a pornographic mindset, which celebrates sex purged of the deeper reality of sexual difference, ridding sexual relations of any genuine reckoning with the particular subjective and objective otherness of the other sex, an otherness that should excite wonder, love, responsibility, and care.

In a manner similar to pornography, in celebrating women fighting, a taboo is being broken, something that may add to the frisson of the female sport for many audiences. However, this taboo is an important one, one that upholds the dignity of the sexes in their differences. As women fight and are exposed to violence for our entertainment, the male fantasy that men could justifiably treat women with the greater roughness with which they treat men is being indulged. We are dulled to our responsibilities towards women, to our need to hold back our strength for their sake, and to our duty to employ it for their well-being and in their service.

A Negative Development for Women

The strength and athleticism of women such as Rousey and Nunes is worthy of admiration in many respects. However, the rise of female pugilistic sports and the presentation of women in such sports as standard bearers for their sex is not a trend to celebrate. This is just another indication of our culture’s idealization of those women who most break with the natural tendencies of their sex and our desire to deny the insistent reality of sexual difference more generally. It is a further example of the idealization of women who most conform to male norms of behavior, interests, and aptitudes, an idealization that can make unlikely allies of contemporary feminists and male fantasists.

The vast majority of women, whose differences with men are far-reaching in ways that they may not be for a fictional female action hero or a lesbian UFC fighter, may be those who are most ill-served by our cultural fixation on celebrating those women who most conform to male norms and succeed in male realms. In the intense celebration of such figures there has been a corresponding devaluation of natural female tendencies, interests, and aptitudes. As our cultural awareness of sexual difference is effaced, many of the forms of honor, recognition, and protection that were once extended to women in society are being removed. While these cultural norms were often sadly caught up with abusive attitudes towards and restrictive constraints upon women, in relieving ourselves of the latter, we risk jettisoning many of the good things that characterized the former.

The Good Ends of Creation

In Scripture, natural differences between men and women are related to more fundamental realities. In Genesis 2 and elsewhere, we see that men and women were created for different yet inescapably intertwined purposes. The physical differences in strength and the psychological differences in relation to agonism between men and women aren’t accidental and unimportant contrasts, but relate to the more basic differences between the purposes for which men and women were created. The differences between male and female strengths, tendencies, interests, and aptitudes testify, to greater and lesser degrees, to these differences in creational purpose. That, from Genesis 2, the duty of guarding and, by implication, fighting falls to the man is a reality borne out through the rest of the Scriptures.

The many moral questions raised by pugilistic sports in the case of men are very considerably heightened in the case of women when we appreciate the manner in which such an activity cuts against the grain of the ends for which they were created.

Why Christians Should Refuse to Celebrate Women Fighting

I invited Alastair J. Roberts, author of the big forthcoming book, Heirs Together: A Theology of the Sexes (Crossway, 2017), to share his thoughts about the popular phenomenon of women like Ronda Rousey fighting other women in mixed-martial arts.

Tonight, Ronda Rousey returns to the ring, after last year’s surprising loss to Holly Holm, to fight Amanda Nunes in the UFC.

The Rise of Women in Mixed Martial Arts

Rousey is an important figure in UFC: she was the first to sign with them, was a catalyst for their opening up to women, and has been one of their greatest audience draws.

The commercial success of women in mixed martial arts has been remarkable, with the women’s sport proving more popular in many cases than its male counterpart, albeit still with an overwhelmingly male audience (MMA has one of the greatest disparities in the gender ratio of its audience).

People like to watch women fight.

The female sport just makes sense for UFC. It is a huge money-spinner. It connects with new audiences and increases the interest of existing ones. The curiosity and sex appeal of women fighting is a considerable draw—“easy on the eyes, hard on the face”—and the UFC has foregrounded this in much of its publicity over the last few years.

Including women has also allowed the UFC to develop progressive credentials, improving the reputation of a sport that has had an unwelcome association with domestic abuse and had an exceedingly male-dominated audience. Ronda Rousey has been portrayed as a feminist standard bearer for many, someone who nicely fits the ubiquitous “first X to do Y” scripts that proliferate in the contemporary media.

Men and Fighting

Pugilistic sport has long been viewed as a largely male preserve. This isn’t an accident. The physical differences between men and women in strength and muscularity are exceedingly large. Even the most powerful women seldom exceed average male strength on criteria such as grip strength. As David Puts observes:

Men have about 90% greater upper-body strength, a difference of approximately three standard deviations (Abe et al., 2003; Lassek & Gaulin, 2009).

The average man is stronger than 99.9% of women (Lassek & Gaulin, 2009).

Men also have about 65% greater lower body strength (Lassek & Gaulin, 2009; Mayhew & Salm, 1990), over 45% higher vertical leap, and over 22% faster sprint times (Mayhew & Salm, 1990) . . .

Beyond these huge differences, however, men have always had a much greater propensity toward, aptitude for, and interest in both violence and agonism [=struggle]. Across human societies, the sex differences in this area are displayed in everything from gender ratios in the committing of violent crime, to participation and interest in agonistic sport and competitive activities, to fighting in militaries.

The extent of sexual differences in such areas is an embarrassing fact for a society that would like to neutralize the reality of gender. Continued efforts to include women in modern militaries, for instance, have repeatedly met with entirely predictable setbacks, as the natural reality proves unamenable to our desired social constructions (although new social constructions can provide opportunities to mask this).

Women’s Fighting and Gender Non-Conformity

It is unsurprising that, in activities that swim against the flow of sexual difference, people who are so-called “gender non-conforming” in broader respects should predominate. The term “homosexual” masks the fact, but sexuality is a gender difference, entangled with all sorts of other differences in behavior and interests (over 95% of men are gynephiles [sexually attractive to women or femininity] and over 95% of women are androphiles [sexually attracted to men or masculinity).

Androphilic men exhibit many commonalities with women and gynephilic women many commonalities with men (for instance, lesbians are hugely overrepresented in prisons and perform much more like men when it comes to the earnings gap, preferring higher wage, male-dominated jobs). The authors of an important recent review of science on the subject of sexual orientation observed:

Shared interests and personality characteristics beyond a common sexual orientation likely facilitate the formation of such subcultures. Same-sex-attracted individuals often have more in common with each other, even when they come from disparate cultures, than they do with their larger culture, in part because of gender nonconformity (Norton, 1997; Whitam & Mathy, 1986). For example, across cultures, androphilic men tend to be more female-typical and “people-oriented” in their interests compared to gynephilic men; conversely, gynephilic females tend to be more male-typical and “thing-oriented” than androphilic females (Cardoso, 2013; Lippa, 2008; L. Zheng et al., 2011). Not surprisingly, androphilic males in many cultures worldwide share interests pertaining to the house and home, decoration and design, language, travel, helping professions, grooming, and the arts and entertainment (Whitam & Mathy, 1986).

Opening up the UFC to women has put it on a front line of the wider cultural war against gender difference, perhaps most notably seen in the controversy surrounding Fallon Fox, an openly transsexual competitor in its featherweight division. A large number of UFC fighters have also come out as lesbians: Amanda Nunes, Liz Carmouche, Aisling Daly, Jessica Andrade, Raquel Pennington, Tonya Evinger, etc.

The Public Appetite for Fighting Women

There is a significant appetite among the public for “kicka*s women,” perhaps especially seen in the trope of the “strong female character,” typically a thin, underdressed, conventionally attractive young woman who can comfortably beat up men much larger than her [think Jennifer Garner as Sydney Bristow in Alias, for example]. Such women exemplify the virtues of much contemporary feminism and gender theory, which commonly seek to deny the reality of sexual difference, overturn all gender norms, and disproportionately celebrate women who achieve in traditionally male activities or contexts. Kicka*s women improve the “representation” of women in male-dominated realms and are frontline heroes from the ongoing war against the patriarchy.

Young and attractive kicka*s women hold a great appeal for many men too. Not only are they nice to look at, they can also relieve men of some of the burdensome sense of duty to treat women differently from men, to be gentler towards them, to protect them, to accord them particular honor, to be mindful of the advantages they generally enjoy naturally over women in power and agency, and to recognize the fact that women and men have many deeper differences in personality, behavior, and interests. Such representations of women can play into a pornographic mindset, which celebrates sex purged of the deeper reality of sexual difference, ridding sexual relations of any genuine reckoning with the particular subjective and objective otherness of the other sex, an otherness that should excite wonder, love, responsibility, and care.

In a manner similar to pornography, in celebrating women fighting, a taboo is being broken, something that may add to the frisson of the female sport for many audiences. However, this taboo is an important one, one that upholds the dignity of the sexes in their differences. As women fight and are exposed to violence for our entertainment, the male fantasy that men could justifiably treat women with the greater roughness with which they treat men is being indulged. We are dulled to our responsibilities towards women, to our need to hold back our strength for their sake, and to our duty to employ it for their well-being and in their service.

A Negative Development for Women

The strength and athleticism of women such as Rousey and Nunes is worthy of admiration in many respects. However, the rise of female pugilistic sports and the presentation of women in such sports as standard bearers for their sex is not a trend to celebrate. This is just another indication of our culture’s idealization of those women who most break with the natural tendencies of their sex and our desire to deny the insistent reality of sexual difference more generally. It is a further example of the idealization of women who most conform to male norms of behavior, interests, and aptitudes, an idealization that can make unlikely allies of contemporary feminists and male fantasists.

The vast majority of women, whose differences with men are far-reaching in ways that they may not be for a fictional female action hero or a lesbian UFC fighter, may be those who are most ill-served by our cultural fixation on celebrating those women who most conform to male norms and succeed in male realms. In the intense celebration of such figures there has been a corresponding devaluation of natural female tendencies, interests, and aptitudes. As our cultural awareness of sexual difference is effaced, many of the forms of honor, recognition, and protection that were once extended to women in society are being removed. While these cultural norms were often sadly caught up with abusive attitudes towards and restrictive constraints upon women, in relieving ourselves of the latter, we risk jettisoning many of the good things that characterized the former.

The Good Ends of Creation

In Scripture, natural differences between men and women are related to more fundamental realities. In Genesis 2 and elsewhere, we see that men and women were created for different yet inescapably intertwined purposes. The physical differences in strength and the psychological differences in relation to agonism between men and women aren’t accidental and unimportant contrasts, but relate to the more basic differences between the purposes for which men and women were created. The differences between male and female strengths, tendencies, interests, and aptitudes testify, to greater and lesser degrees, to these differences in creational purpose. That, from Genesis 2, the duty of guarding and, by implication, fighting falls to the man is a reality borne out through the rest of the Scriptures.

The many moral questions raised by pugilistic sports in the case of men are very considerably heightened in the case of women when we appreciate the manner in which such an activity cuts against the grain of the ends for which they were created.

Why Hollywood Wants to Crush Family-Friendly Filtering Services

This is an entertainingly informative overview on the Hollywood studios’ work to shut down VidAngel:

How can you help?

Currently the best ways to support VidAngel are:

Sign the #SaveFiltering petition at www.SaveFiltering.com

Share our “Is VidAngel Legal?” video with your friends to help get our message out.

Watch the movies that will very soon be offered exclusively on our site (and generously tip the creators so VidAngel can bring in more titles!)

December 21, 2016

How a Little Philosophy Can Help Our Christology

The Apostle Paul famously warned Christians to be on guard lest anyone takes them “captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ” (Col. 2:8). Some have misunderstood this to mean a rejection of philosophy per se.

But done well, and within its limitations, philosophy—literally, φιλο-σοφίας, love of wisdom—can take commonsensical things that we use intuitively and formalize them into definitions with distinctions.

Who Are You?

Take the question, “Who are you?”

We would answer this in terms of those properties—attributes, qualities, characteristics—that make me who I am as an individual. We often answer this identity question by pointing to our relationships (firstborn son of my X and Y; husband of Z; father of A, B, and C) or our physical characteristics (think driver’s license: address; certain height and weight; color of skin, hair, eyes).

What Are You?

A less common question, but one quite relevant for theology, is “What are you?” With regard to persons, this is getting at the kind of being that one is. This can be called a “kind essence”—the set of properties (or collection of characteristics) sufficient to establish one’s membership in a certain “kind” of being (e.g., God, angel, human, animal, etc.).

Different Kinds of Characteristics

There is also a difference between “common properties” and “essential properties.”

Common properties would be the sort of qualities that most people in that kind or category would have.

Essential properties would be the things that every member of that category has to have—such that to lack one of these properties is not to be a member of this kind.

A common property of being a human being might be “having two arms and two legs.” It’s a true characteristic in most cases. But obviously an amputee is still a human being, therefore we know it’s not an essential property. Properties like “having a human soul” would be in a different category. All living human beings have human souls, such that the absence of a human soul would mean that the being is not a human being.

There are some properties that might give us a bit more pause. For example, we say “to err is human.” But if we’re operating from a biblical worldview we know that this is true for all of us who have inherited Adam’s sin—but it’s not necessarily true for the category “human being” per se. Or take the property “being the biological product of two parents.” Again, it’s true for almost every human, but it is not a necessary property, as a human clone would still be a human being.

The Person of Christ

Believe it or not, this is not merely fun philosophical slicing and dicing. It actually can help us to think about Jesus as God Incarnate, the God-Man.

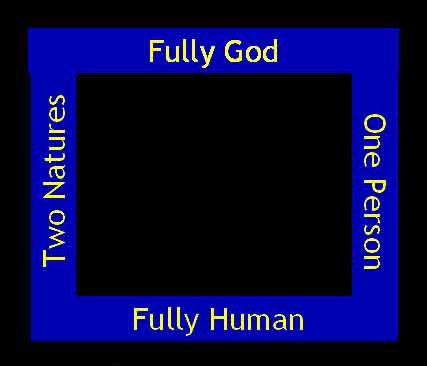

Here’s a simple chart (courtesy of Fred Sanders) summarizing Chalcedonian orthodoxy on the person of Jesus:

What Is Jesus?

Let’s take our second question above, “What are you?” and apply it to Jesus.

On the one hand, he (like all human beings), belongs to the natural kind of humanity. Even if he is not merely human, he is fully human. He has all the essential properties required for full humanity.

On the other hand, he belongs to the natural kind of divinity. He lacks no essential property or attribute required for him to be fully God.

Who Is Jesus?

What about the question “Who are you?” This is asking about Jesus’ individual essence. If we understand this to be the essential properties that make him who he is, then we would want to include his divine kind-essence—his fully-God nature—for those cannot be lost without him ceasing to be the Son of God. Jesus’s human kind-essence, on the other hand, is contingent. It is not something he had forever. And if he had never become incarnate, he still would remain God’s Son.

So in everyday language, we could paraphrase the conclusion of Chalcedon as saying that Jesus is “one who” (one person), with “one what” (fully divine nature), who took on “another what” (fully human nature) in the incarnation—such that he is now “one who” (one person) with “two what’s” (two natures).

In so doing, Chalcedon insisted, these “two what’s” experience “no confusion, no change, no division, no separation.”

How Do We Talk About Things That Only Apply to One Nature?

Now this raises another question. How should we talk about qualities that would apply to only one of Jesus’ natures? For example, “existed from all eternity” applies to his divine nature, not his human nature; “was tired” applies to his human nature, not his divine nature.

The Italian theologian Peter Martyr Vermigli (1492-1562) gives the right answer:

Christ Jesus is one person in whom the two natures subsist in a way that they are joined with each other so that they cannot in any way be pulled apart from each other.

Therefore all the actions of Christ should be attributed to the hypostasis or person because the two natures do not subsist separately and by themselves; neither do they act separately as if one nature is said to do some certain work but the other nature something else.

Therefore just as the [two natures] have one hypostasis or experience, so every work of Christ of any sort should be ascribed to the hypostasis or person itself.

Meanwhile the properties of the two natures which are in Christ should be kept distinct, whole and unmixed so that they cannot in any way be confused. Hence when Christ is said to have been born of the Virgin Mary, been wounded, died, and buried and taken up into heaven—all these things assigned to the person itself in which the two natures exist, but insofar as he was a man, not as God. The divine nature does not allow these changes and sufferings. Again when it is said that Christ is the creator of heaven and earth, that he was before Abraham existed, even that he exists from eternity and is everywhere—these are to be understood of the person or hypostasis, but insofar as it was God, not as a man. For such things are not proper for a created and finite nature. (“A Letter to Poland,” in The Peter Martyr Reader, pp. 127-128.)

In the following century, the Westminster Confession of Faith 8.7 put it like this:

Christ, in the work of mediation, acts according to both natures, by each nature doing that which is proper to itself [Heb. 9:14; 1 Pet. 3:18]; yet, by reason of the unity of the person, that which is proper to one nature is sometimes in Scripture attributed to the person denominated by the other nature [Acts 20:28; John 3:13; 1 John 3:16].

(For more reading on Christology, see Stephen Wellum’s new work, God the Son Incarnate: The Doctrine of Christ.)

The Goal Is Wonder and Worship

In all of our analysis, let us remember that our goal should always be for these doctrines to terminate on wonder and worship of the Incarnate God:

Infinite and yet an infant.

Eternal and yet born of a woman.

Almighty, and yet nursing at a woman’s breast.

Supporting a universe, and yet needing to be carried in a mother’s arms.

Heir of all things, and yet the carpenter’s despised son.”

—Charles Haddon Spurgeon

That man should be made in God’s image is a wonder,

but that God should be made in man’s image is a greater wonder.

That the Ancient of Days would be born.

That He who thunders in the heavens should cry in the cradle?”

—Thomas Watson

Man’s Maker was made man

that the Bread might be hungry,

the Fountain thirst,

the Light sleep,

the Way be tired from the journey;

that Strength might be made weak,

that Life might die.

—Augustine

And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us,

and we have seen his glory,

glory as of the only Son from the Father,

full of grace and truth.”

(John 1:14)

December 18, 2016

Finding Hope When You Lose a Loved One

Nancy Guthrie on the experience behind her new, short book, What Grieving People Wish You Knew about What Really Helps (and What Really Hurts):

December 16, 2016

A Short Biblical Theology of Marriage: A Conversation with Ray Ortlund

Dane Ortlund (co-editor with Miles Van Pelt of Crossway’s Short Studies in Biblical Theology series) talks with his father, Ray Ortlund, on the latest book in the series, Marriage and the Mystery of the Gospel:

You can download a free excerpt of the book here.

“There is no one alive I would rather read than Ray Ortlund. This book will show you why. It shows us how marriage is a metaphor for the gospel itself, the one-flesh union of Christ to his church. This book will help you see the gospel and marriage both in a clearer light—in the light of an unveiled mystery.”

Russell D. Moore, President, The Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention; author, Onward

“Captivating, alluring, and tearfully rendered, Ray Ortlund’s Marriage and the Mystery of the Gospel displays the blood-bought gift of biblical marriage amidst the splendor of the whole biblical landscape. No polemics here—just the love of God poured out to conquer hell itself. Each page shows the biblical worldview in its aesthetic loveliness and disarming power. And don’t let the title fool you. This is not just another book on marriage. Readers will drink in a tour de force of biblical majesty on display on each and every page.”

Rosaria Butterfield, former tenured Professor of English at Syracuse University; author, The Secret Thoughts of an Unlikely Convert; mother, pastor’s wife, and speaker

“Ray Ortlund brilliantly enables you to carefully examine your marriage through the lenses of creation, fall, law, and gospel. In so doing, he helps us deepen our understanding of marriage, know why it is a struggle for us all, diagnose the marriage confusion in our culture, be clear where marriage help is to be found, and fall in love all over again with our God of amazing love, wisdom, and grace.”

Paul David Tripp, President, Paul Tripp Ministries; author, What Did You Expect?

“In this movement through Scripture, Ray gave me more reason to love and nurture my wife. He also let me gaze at even bigger matters. He took my marital story and revealed how it is by Jesus, for Jesus, and to Jesus.”

Ed Welch, counselor; faculty member, the Christian Counseling and Educational Foundation

“My husband and I asked Ray Ortlund to preach on marriage as a picture of redemption at our wedding. We knew him to be a pastor with a scholar’s head and a lover’s heart. And we admired his and Jani’s marriage as a beautiful picture of the passionate, tender, loving relationship between Christ and his church. For the same reasons, I commend this book to you. It will deepen your understanding of the divine mystery of marriage and why it matters, and will inflame your heart to pursue greater love and oneness with Christ and with your mate.”

Nancy DeMoss Wolgemuth, author; Host, Revive Our Hearts

“Marriage and the Mystery of the Gospel lifts our eyes above the contemporary debates over complementarianism and egalitarianism, feminism and patriarchy, same-sex unions, and divorce and remarriage. Ortlund places our focus on the glory of the cosmic love story, and the joy-filled hope this story offers for finding true romantic love in a fallen world. This is biblical theology at its best.”

Eric C. Redmond, Assistant Professor of Bible, Moody Bible Institute; Pastor of Adult Ministries, Calvary Memorial Church, Oak Park, Illinois

“The widespread tendency to treat the Bible as if it has been dropped straight down from heaven into the hands of the individual believer significantly inhibits the life and hampers the mission of the church. This series of Short Studies in Biblical Theology holds important promise of helping to remedy this situation with its goal of providing pastors and their congregations with studies of key biblical themes that will foster a growing understanding and appreciation of the redemptive-historical flow and Christ-centered focus of Scripture as a whole. I look forward with anticipation to the appearance of these volumes.”

Richard B. Gaffin Jr., Professor of Biblical and Systematic Theology, Emeritus, Westminster Theological Seminary

December 14, 2016

He Came Down: The Best Christmas Pageant Ever

From Speaklife in the UK:

December 7, 2016

A Woman of Whom the World Was Not Worthy: Helen Roseveare (1925-2016)

“God never uses a person greatly until He has wounded him deeply.

The privilege He offers you is greater than the price you have to pay.

The privilege is greater than the price.”

—Helen Roseveare

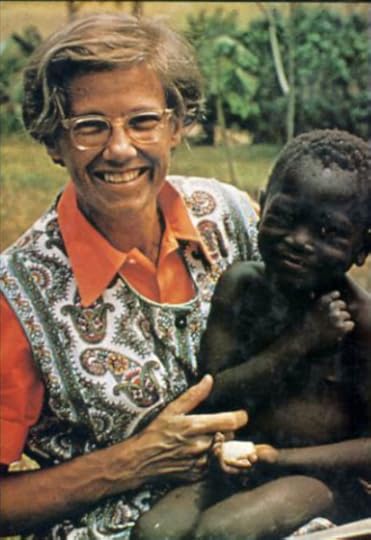

Dr. Helen Roseveare, a famous English missionary to the Congo, has passed away at the age of 91.

Dr. Helen Roseveare, a famous English missionary to the Congo, has passed away at the age of 91.

Helen Roseveare was born in 1925 at Haileybury College (Hertfordshire, England), where her father taught mathematics.

Raised in a high Anglican church, Helen’s Sunday school teacher once told their class about India, and Helen resolved to herself that she would one day be a missionary.

Despite the Christian heritage of her family, and faithful attendance at church, Helen sensed a void in her life and distance from God.

She enrolled in Newnham College at Cambridge University to study medicine. There she joined the Cambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union (CICCU) through the invitation of a student named Dorothy. She became an active participant in the prayer meetings and Bible studies, reading the New Testament for the first time. But she later said that her understanding of Christianity was more head knowledge than heart engagement.

In the winter of 1945, the Lord seemed to meet her in a personal way during a student retreat. She gave her testimony on the final evening, and Bible teacher Graham Scroggie wrote Philippians 3:10 in her new Bible, and told her:

Tonight you’ve entered into the first part of the verse, “That I may know Him.” This is only the beginning, and there’s a long journey ahead. My prayer for you is that you will go on through the verse to know “the power of His resurrection” and also, God willing, one day perhaps, “the fellowship of His sufferings, being made conformable unto His death.”

She felt an increased sense of calling toward missions, and publicly declared during a missionary gathering in North England, “I’ll go anywhere God wants me to, whatever the cost.”

Afterwards, I went up into the mountains and had it out with God. “O.K. God, today I mean it. Go ahead and make me more like Jesus, whatever the cost. But please (knowing myself fairly well), when I feel I can’t stand anymore and cry out, ‘Stop!’ will you ignore my ‘stop’ and remember that today I said ‘Go ahead!’?”

After graduating from Cambridge with her doctorate in medicine, Helen studied for six months at the Worldwide Evangelization Crusade college at Crystal Palace. From there she went to Belgium to study French and Holland to take a course on tropical medicine as she prepared for her appointment as a medical missionary in the Congo.

In mid-March of 1953, at the age of 28, she arrived in the northeastern region of the Congo (later named Zaire).

In the first two years, she founded a training school for nurses, training women to serve as nurse-evangelists, who in turn would run clinics and dispensaries in different regions.

In October 1955, she was asked to transfer seven miles away to run an abandoned maternity and leprosy center in Nebobongo. Working with local Africans, Helen helped to transform the center into a hospital with 100 beds, serving mothers, lepers, and children, along with a training school for paramedics and 48 rural clinics. Outside of these facilities, there was no other medical help for 150 miles in any direction.

In October 1955, she was asked to transfer seven miles away to run an abandoned maternity and leprosy center in Nebobongo. Working with local Africans, Helen helped to transform the center into a hospital with 100 beds, serving mothers, lepers, and children, along with a training school for paramedics and 48 rural clinics. Outside of these facilities, there was no other medical help for 150 miles in any direction.

Exhausted, Helen returned to England in 1958 for a furlough, during which time she received further medical training.

The Congo became independent from Belgium in 1960, and civil war broke out in 1964. All of the medical facilities they had established were destroyed. Helen was among ten Protestant missionaries put under house arrest by the rebel forces for several weeks, after which time they were moved and imprisoned.

She describes the horror of what happened after she tried to escape:

They found me, dragged me to my feet, struck me over head and shoulders, flung me on the ground, kicked me, dragged me to my feet only to strike me again—the sickening searing pain of a broken tooth, a mouth full of sticky blood, my glasses gone. Beyond sense, numb with horror and unknown fear, driven, dragged, pushed back to my own house—yelled at, insulted, cursed.

Her captors, she wrote, “were brutal and drunken. They cursed and swore, they struck and kicked, they used the butt-end of rifles and rubber truncheons. We were roughly taken, thrown in prisons, humiliated, threatened.”

On October 29, 1964, Helen Roseveare was brutally raped.

She later recounted:

On that dreadful night, beaten and bruised, terrified and tormented, unutterably alone, I had felt at last God had failed me. Surely He could have stepped in earlier, surely things need not have gone that far. I had reached what seemed to be the ultimate depth of despairing nothingness.

In this darkness, however, she sensed the Lord saying to her:

You asked Me, when you were first converted, for the privilege of being a missionary. This is it. Don’t you want it? . . . These are not your sufferings. They’re Mine. All I ask of you is the loan of your body.

She eventually received an “overwhelming sense of privilege, that Almighty God would stoop to ask of me, a mere nobody in a forest clearing in the jungles of Africa, something He needed.”

She later pointed to God’s goodness despite this great evil:

Through the brutal heartbreaking experience of rape, God met with me—with outstretched arms of love. It was an unbelievable experience: He was so utterly there, so totally understanding, his comfort was so complete—and suddenly I knew—I really knew that his love was unutterably sufficient. He did love me! He did understand!

She also wrote:

[God] understood not only my desperate misery but also my awakened desires and mixed up horror of emotional trauma. I knew that Philippians 4:19, “My God will supply every need of yours according to his riches in glory in Christ Jesus,” was true on all levels, not just on a hyper-spiritual shelf where I had tried to relegate it. . . . He was actually offering me the inestimable privilege of sharing in some little way in the fellowship of His sufferings.

This theme of “privilege” became prominent in Helen’s ministry. In her Urbana ’76 address, she said:

One word became unbelievably clear, and that word was privilege. He didn’t take away pain or cruelty or humiliation. No! It was all there, but now it was altogether different. It was with him, for him, in him. He was actually offering me the inestimable privileged of sharing in some little way the edge of the fellowship of his suffering.

In the weeks of imprisonment that followed and in the subsequent years of continued service, looking back, one has tried to “count the cost,” but I find it all swallowed up in privilege. The cost suddenly seems very small and transient in the greatness and permanence of the privilege.

After returning to African in 1966, she soon left Nebobongo to establish a new medical center in Nyankunde in northeastern Zaire, producing a 250-bed hospital, maternity ward, training college for doctors, a center for leprosy, and other endeavors.

There, too, she experienced several trials and relational difficulties. She never claimed to see visions or hear the voice of the Lord, but she did sense him rebuking her attitude. On one occasion, her conviction from the Lord went as follows:

You no longer want Jesus only, but Jesus plus . . . plus respect, popularity, public opinion, success and pride. You wanted to go out with all the trumpets blaring, from a farewell-do that you organized for yourself with photographs and tape-recordings to show and play at home, just to reveal what you had achieved. You wanted to feel needed and respected. You wanted the other missionaries to be worried about how they’ll ever carry on after you’ve gone. You’d like letters when you go home to tell how much they realize they owe to you, how much they miss you. All this and more. Jesus plus. . . . No, you can’t have it. Either it must be “Jesus only” or you’ll find you have no Jesus. You’ll substitute Helen Roseveare.

In 1973, Helen returned to the UK for health reasons, settling in Northern Ireland. She traveled, wrote several books, and served as a missionary advocate.

She went to be with her Lord, from whom she counted it a privilege to suffer, on December 7, 2016, at the age of 91.

December 5, 2016

Why This Woman Is Not Sad After a Mistrial for Her Son Being Shot in the Back

Amazing testimony from Walter Scott’s mother, whose comments begin at 1:45:

You can read more about the trial here.

Why This Woman Is Not Sad After a Mistrial for Her Son Being Shot in the Back and

Amazing testimony from Walter Scott’s mother, whose comments begin at 1:45:

You can read more about the trial here.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers