Justin Taylor's Blog, page 42

March 20, 2017

But What’s So Wrong about Burning Out for Jesus?

Derek Thomas recently wrote about David Murray’s new book, Reset: Living a Grace-Paced Life in a Burnout Culture:

The simple truth is this: I needed this book right now!

There are truths in this volume—pastoral insights and healing counsels—that speak to me in very personal and tender ways.

Occasionally, Murray’s point is so clear—far too clear—that it feels as though I have gotten a slap in the face.

But always—always—the point has been to drive me to Christ and to drive me to the embrace of the gospel.

This is medicine for the soul in the best possible sense, and I am grateful to the author for writing it.

It really does feel as though he wrote it for me.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Dr. Murray to find out what motivated the book, who it is for, and what he hopes it will accomplish.

Timestamps

0:00 – Who did you write Reset for?

2:31 – What do you mean by the phrase “grace-paced life”?

6:28 – What would you say to a young church planter who desires to live radically and burn out for Jesus?

9:57 – Does your book include practical, tactile, next-step action points?

13:46 – In what ways is your book specifically targeted at men?

14:44 – How do you hope the Lord uses your book in the lives of those who read it?

“This is so timely. After you read it, you will sleep better, for starters. Then you will be taken to the meeting place of essential theology and the details of all things related to our stressed lives, where David offers wisdom on every page. The book is perfect for men’s groups.”

—Ed Welch, counselor; faculty member, the Christian Counseling and Educational Foundation

“For far too long, whether consciously or subconsciously, we Christians have bought into the platonic lie that the spirit matters, but the body does not. As a result, we have neglected, and perhaps even abused, our bodies. It’s no wonder we struggle with food, sleep, and health—both physical and mental. In Reset, David Murray returns us to a biblical anthropology, providing us with a biblical and theological framework by which we may reorder our lives as whole persons—body and spirit—for God’s glory, our well-being, and the service of others.”

—Juan R. Sanchez, Senior Pastor, High Pointe Baptist Church, Austin, Texas; author, 1 Peter for You and Gracia Sobre Gracia

“From a vast reservoir of personal experience, authenticating social research, and timeless theological wisdom, David Murray shines illuminating light on the dark perils of pastoral burnout. He also offers practical guidance for how the easy yoke of apprenticeship with Jesus makes possible the grace-paced life that leads to personal and vocational wholeness. I highly recommend this needed approach.”

—Tom Nelson, author, Work Matters; Senior Pastor, Christ Community Church, Overland Park, Kansas; President, Made to Flourish

“Men, this wise book is like a personal coach for your daily life. The one who writes it understands what it is to be a man with a man’s cares and a man’s dreams. He cares deeply about the masculine body and soul that God has given you. You were made with large purpose. David Murray wants to help you learn how to practically take stock of your life, recover your purpose, and live it!”

Zack Eswine, Lead Pastor, Riverside Church, Webster Groves, Missouri; author, The Imperfect Pastor

“Reset: Living a Grace-Paced Life in a Burnout Culture, like its author, David Murray, is full of surprises. While statistics and sociologists jostle for space alongside Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and a kilted haggis, everything is set within a robust biblical anthropology and a well-grounded pastoral psychology. The whole is laced with a fine touch of self-deprecating Scottish humor. Dr. Murray is Jeremiah-like in the rigor and love with which he seeks ‘to pluck up and break down . . . to build and to plant.’ But he is also Jesus-like in the way he employs the deconstructing and reconstructing grace of the gospel. Here is a book full of practical, spiritual wisdom and a must read.”

—Sinclair B. Ferguson, Professor of Systematic Theology, Redeemer Seminary, Dallas, Texas

“You hold in your hand what is quite possibly the most culturally relevant book for pastors I have ever read. Contained in this book is the answer to the epidemic among both pastors and hardworking Christian men who are physically, emotionally, and spiritually collapsing because of the lightning-fast pace our modern culture demands. Murray lays out a thoroughly biblical, immensely practical plan for any Christian man looking to take back his life from the enslavement of his schedule. Murray’s beautiful personal testimony of his own need to reset is worth the book alone. This book will be required reading for every pastor I know.”

—Brian Croft, Senior Pastor, Auburndale Baptist Church, Louisville, Kentucky; Founder, Practical Shepherding; Senior Fellow, Church Revitalization Center, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

“In Reset, David Murray pries our fingers from the death grip we have on the idol of activity. Since I am a confessed workaholic, this book was right on time for me. I quickly implemented the strategies outlined in this book, and experienced immediate results in terms of relief, rest, and peace. Relentlessly honest, refreshingly concise, and eminently practical, this book may literally save your marriage, your ministry, and your health. I see myself revisiting Reset every time I need to be reminded of the grace of both work and rest.”

—Jemar Tisby, Cofounder and President, Reformed African American Network; Cohost, Pass the Mic

You can read a sample from the book here.

In October 2017, Crossway will publish Shona and David Murray’s Refresh: Embracing a Grace-Paced Life in a World of Endless Demands, written specifically for women.

In October 2017, Crossway will publish Shona and David Murray’s Refresh: Embracing a Grace-Paced Life in a World of Endless Demands, written specifically for women.

March 16, 2017

What 16 Words Would You Choose to Summarize the Whole Bible?

Chris Bruno—recently named Assistant Professor of New Testament and Greek at Bethlehem College and Seminary—is the author of a new book, The Whole Message of the Bible in 16 Words.

Chris Bruno—recently named Assistant Professor of New Testament and Greek at Bethlehem College and Seminary—is the author of a new book, The Whole Message of the Bible in 16 Words.

Here is a brief description:

At the heart of the Bible is one overarching message: God saving his people through their promised Messiah.

This accessible introduction to the main point of the Bible traces the development of sixteen key themes— creation, covenant, kingdom, temple, judgment, and more—from Genesis to Revelation, showing how both the Old and New Testaments come together to declare a single unified message.

A concise primer to biblical theology, this book helps readers trace God’s unfolding plan of redemption throughout the Bible.

I sat down with Dr. Bruno to ask him about the book, how it relates to his prequel (The Whole Story of the Bible in 16 Verses), and how this book should be used.

Timestamps

0:00 – What were you trying to do in the first book you wrote—The Whole Story of the Bible in 16 Verses?

1:37 – What are you doing differently in your new book, The Whole Message of the Bible in 16 Words?

3:30 – Why did you begin with eschatology—the study of the end things—in your book?

6:15 – Why are the themes of creation, covenant, and kingdom foundational for understanding the overall message of Scripture?

8:30 – Knowing this is a book on the Bible’s whole message, can you discuss the length and format of your book?

11:21 – How do you hope a book like this will be used?

You can download an excerpt of the book here.

An FAQ on Shaping Your Ministry Culture Around Disciple-Making

In 2009 a small Australian publisher quietly released a book entitled The Trellis and the Vine: The Ministry Mind-Shift that Changes Everything, co-authored by Sydney Anglicans Colin Marshall and Tony Payne.

The book became an unlikely international bestseller, especially when Mark Dever offered his unsolicited endorsement that “This is the best book I’ve read on the nature of church ministry,” and began reading excerpts of the book aloud at conferences.

If you haven’t read it, you don’t need to. It’s been superseded by their new book, The Vine Project: Shaping Your Ministry Culture around Disciple-Making. I’ve read it, found it compelling and convincing, and would recommend it to anyone in ministry.

The book replicates the vision from the earlier book, but this time with more nuance. Even more importantly, it carefully and thoroughly seeks to help ministries actually implement the vision. It’s for those who are convinced of this biblical vision but don’t know how to put it into practice.

(You can read reviews of the book from 9Marks, TGC, and Challies.)

(If you get the book, make sure you connect with them here, where you can interact, watch videos, download manuals, and get further support and training.)

I’ve reproduced below, with permission, their summary answers to the five convictions they unpack.

1. Why make disciples?

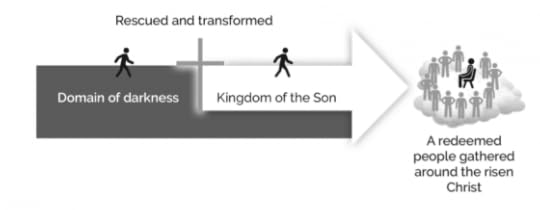

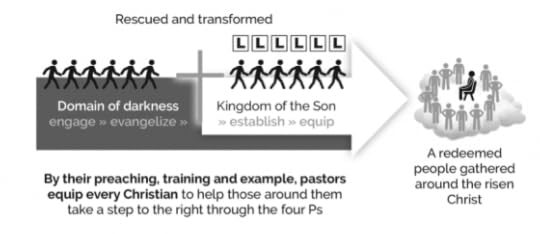

The reason we want to make more and more disciples of Jesus Christ is because God’s goal for the whole world and the whole of human history is to glorify his beloved Son in the midst of the people he has rescued and transformed.

God is now putting this plan into effect, by rescuing people out of “this present darkness” into the kingdom of his Son by his death and resurrection—people who are being transformed to be like Jesus, and who now have a sure and certain place around Christ’s throne in a new creation where evil and death are no more.

This is the zoomed-out picture that explains why making more disciples is so important and so urgent a task.

We could represent it like this:

2. What is a disciple?

A disciple is a forgiven sinner who is learning Christ in repentance and faith.

In the Gospels a “learner” (or “disciple”) of Christ is someone who has recognized the dark and lost state they were living in under God’s judgement, and who has turned to Christ in repentance and faith as Master, Savior, and Teacher to commit themselves totally to obeying him, to learning to keep all his commandments, and to living out that repentance and faith daily for the rest of their lives. This kind of “transformational learning” is really another way of describing the totality of the Christian life.

This same framework of thinking carries into the rest of the New Testament, where “learning Christ” means hearing the word of the gospel (of Christ’s saving rule), responding to that word in faith, and thereby passing from death to life in Christ—with a resulting urgency to kill off the sinful worldly behavior that remains from their former life, and to put on instead the new clothes of Christ.

To become a “Christ-learner,” then, is both a decisive and gigantic step of repentance in accepting the salvation that God has won for us through Christ (symbolized by baptism), and an ongoing daily commitment to living out the implications and consequences of this massive salvation that God has won for us (symbolized by the yoke).

We could add one small detail to our diagram to represent this—namely an ‘L’ (learner) sign above the person who has been transferred out of darkness and into the kingdom of the Son, and who now continues that transformational learning in every sphere of life, especially in the “transformational learning community” that we call “church.”

3. How are disciples made?

How does this rescue and redemption happen? The making of disciples is God’s work, achieved as his word and Spirit work through the activity of Christian disciples and in the hearts of those they speak to. We summarize that activity as the persevering proclamation of the word of God by the people of God in prayerful dependence on the Spirit of God, otherwise known as the four Ps:

Proclamation of the word in multiple ways

Prayerful dependence on the Spirit

People are God’s fellow workers

Perseverance, step by step

The goal of every form of Christian ministry could therefore be summarized simply as seeking to help each person, wherever they happen to be, to take “one step to the right” through these four Ps—that is, to hear the gospel and be transferred out of the domain of darkness into the kingdom, and then to press forward toward maturity in Christ in every aspect of life, by the constant, persevering, prayerful proclamation of God’s word by people in multiple ways.

Our diagram would now look like this:

To think more clearly about the different “places” people occupy on this spectrum of moving to the right, we could usefully identify four broad stages that people pass through on their road ‘to the right':

Some people are very “far away” from Christ and his kingdom; they may not have ever met or spoken with a Christian person. Very often the first thing they need in order to take a step to the right is to meet and engage with a Christian.

Others have met and engaged with Christians or Christianity in some way. The next step for them is to hear the gospel; that is, to be evangelized .

For those who have responded to the gospel in faith and repentance, their next step is to be established as a Christian, to send down roots, and to begin to grow in godliness and Christlikeness (a “walk” that will continue for the rest of their lives).

As Christians are established, and grow in love and knowledge, they will become increasingly concerned not only to step to the right themselves, but to help others do so in whatever way they can. They will benefit from being equipped to do so through teaching, encouragement, coaching and prayer.

We like to use these four Es as handy signposts for different stages of the journey: Engage, Evangelize, Establish and Equip.

We could add them to our diagram like this:

4. Who makes disciples?

In this conviction, we dig deeper into the idea that it is the joy and privilege of all God’s people to be involved in the four Ps. The Bible teaches that God by his Spirit opens the mouths of all disciples to speak the one word of Christ, in a richly varied way. Speaking the word of God to others for their salvation and encouragement is an expected and necessary component of the normal Christian life. And correspondingly, a healthy church culture is one in which a wide variety of word ministries are exercised by a constantly growing proportion of the membership.

Expository preaching is vitally connected to this kind of “every member word ministry.” An expository pulpit is the foundational word ministry that feeds and regulates and equips and builds an “expository church,” in which the word of the Bible is being ministered at multiple levels in a rich variety of ways by the congregation.

In other words, we could answer the question “Who makes disciples?” as follows: By their preaching, training and example, pastors equip every Christian to be a Christ-learner who helps others to learn Christ.

Or to use our language of “moving to the right,” we could change the summary statement at the bottom of our diagram to reflect this integrated picture of the expository church:

5. Where are disciples made?

Making and growing “Christ-learners” is not just something that happens with new Christians, or in small groups, or in one-to-one counseling. It is the basic activity that should be at the center of everything we do as a church—that is, as a transformational learning community—including and especially our Sunday gatherings. One way of describing Sunday church is as a “theatre for disciple-making,” in which we seek to help everyone present take a “step to the right” through the prayerful proclamation and speaking of the word of God.

The missional or evangelistic side of making Christ-learners is not something that only happens overseas in traditional “mission work.” The where of making more learners of Christ is all around us—in our families and streets and communities, in every corner of this present darkness in which people are so desperately in need of the saving gospel of Christ.

Where, then, does learning Christ take place? It happens in every facet and activity of the transformative learning communities we call churches; and through our churches, it also happens in every corner of this present darkness.

March 10, 2017

Fred Sanders on the Trinity and The Shack

I’ve never been able to must up enough interest to read the runaway self-published bestseller, The Shack.

I don’t plan to see the movie—more from apathy than from some great opposition.

And I won’t be writing any “hot takes” on the theology of the movie or on the critics or on criticism of the critics of the critics . . .

But I’ll listen to Fred Sanders talk about (almost) anything—especially when it relates to the Trinity.

Fred, who teaches in the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola University, has written a technical work on the Trinity, has a new book out on The Triune God, and will come out in April with a second edition of The Deep Things of God: How the Trinity Changes Everything (now with study guide, discussion questions, action points, recommended reading, and more).

March 9, 2017

I Am a Poor Wayfaring Stranger

A beautiful rendition sung by Karen Ellis:

I am a poor wayfaring stranger

Just traveling through this world of woe

But there’s no sickness, toil, or danger

In that bright land to which I go

I’m going there to see my Father

I’m going there no more to roam

I’m only going, going o’er Jordan

I am just a-going to my home

I know dark clouds will gather ’round me

I know my way is rough and steep

Yet beauteous fields lay just before me

Where the redeemed, no more shall weep

So I will wear my crown of glory

When I get home to that good land

And I will sing redemption’s story

In concert with the blood-washed band

I’m going there to see my Savior

I’m going there to praise my Lord

I’m going, going o’ver Jordan

I’m only going to my home

An Analysis of One of the Greatest Sentences Ever Written

Because you have made us for Yourself,

and our hearts are restless till they find their rest in Thee.

Augustine, Confessions, 1.1.1.

Peter Kreeft:

Here it is: one of the greatest sentences ever written, the basic theme . . . of life itself.

It has two parts.

The first is the objective fact, and the second is the subjective experience.

In fact, the first is the fundamental objective fact of life, and the second is the fundamental subjective experience of life.

They are connected by an implied “therefore”: our hearts are restless until they rest in God because He has made us for Himself. We feel like homing pigeons because we are.

Thus the fundamental claim of Christian anthropology (that God has made us for Himself) explains the fundamental fact of human experience (that our hearts are restless).

There are three truths here:

1. You stir man to take pleasure in praising you*

2. because you have made us for yourself

3. and our heart is restless until it rests in you.

They are related logically by the “for” [because] and by the “and,” which implies “and therefore.”

The fact (2) that God has made us for Himself is the fundamental objective fact.

The other two statements are the two subjective experiences that follow from it and are explained by it (and by it alone:

(1) that the human heart finds joy . . . in praising God, the God it has found; and

(3) that if finds only restlessness without Him.

Thus the deepest fact of Christian theological anthropology explains the two deepest facts of human experience.

The “for” [because] in the first part is the English translation not of pro but of ad. “Fecisti nos ad te.”

Pro is the preposition for ownership, but if Augustine had written pro, the sentence still would have been profoundly true: God our Creator owns us, rightly claims us.

But ad makes a deeper point. It is a preposition expressing dynamic movement. It means “toward.” God has made us toward Himself. We exist “to” or “toward” or “in movement to” Him, like arrows moving toward a target or homing pigeons flying home. We are verbs as well as nouns.

We are not static objects, but dynamic, moving subjects. We are not God’s property so much as God’s lovers. He is not only our origin and our owner, He is also our end, our purpose, our destiny, our identity, our meaning, our peace, our joy, our home.

The story of Augustine’s life is the story of a homeless person’s journey to his true home. And when he arrives, he finds both His own identity and God’s. The two always go together . . .

In his Soliloquies, which are imaginary conversations between God and himself, Augustine imagines God asking him what he wants to know, and he replies that he wants to know only two things: who he is and who God is. “Nothing else?” God asks. “Nothing else,” Augustine replies. For everything else is relative to these two things. . . . God and myself are the only two realities I can never escape for a single moment, in time or in eternity; that is why the one absolutely essential thing is to know both. And they are a package deal; neither can be known without the other also being known.

Therefore the Confessions is simultaneously the story of Augustine’s search for himself and his search for God. And it is only Christ who shows us both, who reveals God to man and man to himself by being both perfect God and perfect man.

Ultimately, of course, it is God’s search for Augustine. His search for God is a function of God’s search for him, not vice versa. As the old hymn says,

I sought the Lord and afterward I knew

He moved my soul to seek Him, seeking me.

It was not I that found, O Savior true,

no, I was found by Thee.

Elsewhere Augustine imagines God saying to him, “Take heart; you would not be seeking Me if I had not already found You.”The “restless heart” is the very heart of every human heart.

What makes Augustine different is only that he is honest enough to admit it and passionate enough to run rather than stroll through it.

This restlessness is the second most precious thing in the world, since it is the means to the only good that is even greater than itself, namely, the rest that comes only in God.

Our homelessness, our alienation, our misery, our confusion, our lover’s quarrel with the world—this is our greatest blessing, next to God Himself.

Peter Kreeft, I Burned for Your Peace: Augustine’s Confessions Unpacked (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2016), 21-23.

*I’ve changed this quote from Shedd’s translation (which Kreeft uses) to Chadwick’s because I can’t make sense of how Shedd is rendering the Latin (tu excitas ut laudare te delectet).

March 8, 2017

Writing with Flannery O’Connor: A Six-Week Course

Jonathan Rogers—a novelist and a biographer of Flannery O’Connor—is teaching a six-week online writing course, which he introduces below:

You can sign up for it here. Below is more information on what is covered each week, followed by a brief introduction to Flannery O’Connor.

March 13-April 21, 2017

Besides being a brilliant writer, Flannery O’Connor wrote quite a bit about the craft of writing. In this six-week course, we will look at O’Connor’s essays about writing in Mystery and Manners, examine ways that she implemented her principles in her short stories, and implement those principles ourselves in short writing exercises.

My goal as instructor will not be to get you to mimic O’Connor, but to help you find your own voice–to help you write in your native tongue, just as O’Connor wrote in hers. Though O’Connor’s wrote more or less exclusively about fiction, most of her principles are equally applicable to non-fiction narratives.

Typical weekly workload

Reading: One essay and one story from O’Connor (there will also be optional readings)

Writing: 2-3 pages

Listening: 20-30 minute lecture

Online Discussion: I will post several discussion questions each week. Hopefully they will lead to fruitful discussion in which you can participate as time allows.

Required Texts

Flannery O’Connor, Mystery and Manners

Flannery O’Connor, Complete Stories

Recommended Text

Jonathan Rogers, The Terrible Speed of Mercy: A Spiritual Biography of Flannery O’Connor

Syllabus (tentative)

Week 1: The Nature of Narrative

Essay–“Writing Short Stories”

Short Story–“The Life You Save May Be Your Own”

Week 2: Native Country, Native Tongue

Essay–“The Fiction Writer and His Country”

Short Story–“Greenleaf”

Week 3: Using Metaphor and Symbol

Essay–“The Nature and Aim of Fiction”

Short Story–“Good Country People”

Week 4: Unexpected but Believable

Essay–“Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction”

Short Story–“A Good Man Is Hard to Find”

Week 5: Mystery and Manners

Essay–“Novelist and Believer”

Short Story–“A Temple of the Holy Ghost”

Week 6: Fiction and Faith

Essay–“The Catholic Novelist in the Protestant South”

Short Story–“The River”

Here is an excerpt from Rogers’s spiritual biography of Flannery O’Connor:

If her stories offend conventional morality, it is because the gospel itself is an offense to conventional morality. Grace is a scandal; it always has been. Jesus put out the glad hand to lepers and cripples and prostitutes and losers of every stripe even as he called the self-righteous a brood of vipers.

In “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” it is painful to see a mostly harmless old grandmother come to terms with God and herself only at gunpoint.

It is even more painful to see her get shot anyway.

In a more properly moral story, she would be rewarded for her late-breaking insight and her life would be spared.

But the story only enacts what Christians say they believe already: that to lose one’s body for the sake of one’s soul is a good trade indeed. It’s a mystery, and no small part of the mystery is the reader’s visceral reaction to truths he claims to believe already. O’Connor invites us to step into such mysteries, but she never resolves them. She never reduces them to something manageable.

O’Connor speaks with the ardor of an Old Testament prophet in her stories. She’s like an Isaiah who never quite gets around to “Comfort ye my people.” Except for this: there is a kind of comfort in finally facing the truth about oneself. That’s what happens in every one of Flannery O’Connor’s stories: in a moment of extremity, a character—usually a self-satisfied, self-sufficient character—finally comes to see the truth of his situation. He is accountable to a great God who is the source of all. He inhabits mysteries that are too great for him. And for the first time there is hope, even if he doesn’t understand it yet . . .

In O’Connor’s unique vision, the physical world, even at its seediest and ugliest, is a place where grace still does its work. In fact, it is exactly the place where grace does its work. Truth tells itself here, no matter how loud it has to shout.

On April 22, 1959, at the age of 34, O’Connor visited Vanderbilt University and read her best-known story, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” It was first published in 1955:

Four years later, when she gave a reading of this story at Hollins College in Virginia on October 14, 1963—just 9 months before she died from complications of lupus—she prefaced it with some remarks.

Among other things, she addressed “what makes a story work, and what makes it hold up as a story.” She answered:

I have decided that it is probably some action, some gesture of a character that is unlike any other in the story, one which indicates where the real heart of the story lies. This would have to be an action or a gesture which was both totally right and totally unexpected; it would have to be one that was both in character and beyond character; it would have to suggest both the world and eternity. The action or gesture I’m talking about would have to be on the anagogical level, that is, the level which has to do with the Divine life and our participation in it. It would be a gesture that transcended any neat allegory that might have been intended or any pat moral categories a reader could make. It would be a gesture which somehow made contact with mystery.

She identifies the place of such a “gesture” in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”:

The Grandmother is at last alone, facing the Misfit. Her head clears for an instant and she realizes, even in her limited way, that she is responsible for the man before her and joined to him by ties of kinship which have their roots deep in the mystery she has been merely prattling about so far. And at this point, she does the right thing, she makes the right gesture.

I find that students are often puzzled by what she says and does here, but I think myself that if I took out this gesture and what she says with it, I would have no story. What was left would not be worth your attention. Our age not only does not have a very sharp eye for the almost imperceptible intrusions of grace, it no longer has much feeling for the nature of the violence which precede and follow them. The devil’s greatest wile, Baudelaire has said, is to convince us that he does not exist.

On the violence in her stories, O’Connor comments:

In my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace. Their heads are so hard that almost nothing else will do the work. This idea, that reality is something to which we must be returned at considerable cost, is one which is seldom understood by the casual reader, but it is one which is implicit in the Christian view of the world.

O’Connor knows that some people label this story “grotesque,” but she prefers to call it “literal.”

A good story is literal in the same sense that a child’s drawing is literal. When a child draws, he doesn’t intend to distort but to set down exactly what he sees, and as his gaze is direct, he sees the lines that create motion. Now the lines of motion that interest the writer are usually invisible. They are lines of spiritual motion. And in this story you should be on the lookout for such things as the action of grace in the Grandmother’s soul, and not for the dead bodies.

O’Connor elsewhere expanded on the comparison of stories and drawings:

When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock-to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.

Quotes from: Flannery O’Connor, “On Her Own Work,” in her Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, ed. Sally Fitzgerald and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1969), pp. 107-118. The “stick figures” quote is from “The Fiction Writer and His Country,” Mystery and Manners, p. 34.

March 6, 2017

‘If I Were a College President, I Would Require Every Incoming Freshman to Read This Book and Pass a Test on It before Taking Other Courses’

The headline is a quote from Peter Kreeft, professor of philosophy at Boston College since 1965, in his book Socratic Logic:

On the basis of over 40 years of full time college teaching of almost 20,000 students at 20 different schools, I am convinced that one of the reasons for the steep decline in students’ reading abilities is the decline in the teaching of traditional logic.

Mortimer Adler’s classic How to Read a Book is based on the traditional common-sense logic of the “three acts of the mind” [simple apprehension, judging, reasoning]. . . .

If I were a college president, I would require every incoming freshman to read Adler’s book and pass a test on it before taking other courses.

Mortimer Adler—with co-author Charles Van Doren—suggests there are three main stages for analytical reading, with fifteen major rules for reading well.

I have reproduced an outline below.

Stage 1: What Is the Book About as a Whole?

Rule 1. You must know what kind of book you are reading, and you should know this as early in the process as possible, preferably before you begin to read. / Classify the book according to kind and subject matter. (p. 60)

Rule 2. State the unity of the whole book in a single sentence, or at most a few sentences (a short paragraph). State what the whole book is about with the utmost brevity. (pp. 75-76)

Rule 3. Set forth the major parts of the book, and show how these are organized into a whole, by being ordered to one another and to the unity of the whole. / Enumerate its major parts in their order and relation, and outline these parts as you have outlined the whole. (p. 76)

Rule 4. Find out what the author’s problems were. / Define the problem or problems the author has tried to solve. (p. 92)

Stage 2: What Is Being Said in Detail, and How?

Rule 5. Find the important words and through them come to terms with the author. / Come to terms with the author by interpreting his key words. (p. 98)

Rule 6: Mark the most important sentences in a book and discover the propositions they contain. / Grasp the author’s leading propositions by dealing with his most important sentences. (p. 120)

Rule 7: Locate or construct the basic arguments in the book by finding them in the connections of sentences. / Know the author’s arguments, by finding them in, or constructing them out of, sequences of sentences. (p. 120)

Rule 8: Find out what the author’s solutions are. / Determine which of his problems the author has solved, and which he has not; and as to the latter, decide which the author knew he had failed to solve. (p. 135)

Stage 3: Is It True? What of It?

General Maxims of Intellectual Etiquette

Rule 9: You must be able to say, with reasonable certainty, “I understand,” before you can say any one of the following things: “I agree,” or “I disagree,” or “I suspend judgment.” / Do not begin criticism until you have completed your outline and your interpretation of the book. (pp. 142-143)

Rule 10: When you disagree, do so reasonably, and not disputatiously or contentiously. (p. 145)

Rule 11: Respect the difference between knowledge and mere personal opinion, by giving reasons for any critical judgment you make. (p. 150)

Special Criteria for Points of Criticism

12. Show wherein the author is uninformed.

13. Show wherein the author is misinformed.

14. Show wherein the author is illogical.

15. Show wherein the author’s analysis or account is incomplete.

“If I Were a College President, I Would Require Every Incoming Freshman to Read This Book and Pass a Test on It before Taking Other Courses”

The headline is a quote from Peter Kreeft, professor of philosophy at Boston College since 1965, in his book Socratic Logic:

On the basis of over 40 years of full time college teaching of almost 20,000 students at 20 different schools, I am convinced that one of the reasons for the steep decline in students’ reading abilities is the decline in the teaching of traditional logic.

Mortimer Adler’s classic How to Read a Book is based on the traditional common-sense logic of the “three acts of the mind” [simple apprehension, judging, reasoning]. . . .

If I were a college president, I would require every incoming freshman to read Adler’s book and pass a test on it before taking other courses.

Mortimer Adler—with coauthor Charles Van Doren—suggests there are three main stages for analytical reading, with fifteen major rules for reading well.

I have reproduced an outline below.

Stage 1: What Is the Book About as a Whole?

Rule 1. You must know what kind of book you are reading, and you should know this as early in the process as possible, preferably before you begin to read. / Classify the book according to kind and subject matter. (p. 60)

Rule 2. State the unity of the whole book in a single sentence, or at most a few sentences (a short paragraph). State what the whole book is about with the utmost brevity. (pp. 75-76)

Rule 3. Set forth the major parts of the book, and show how these are organized into a whole, by being ordered to one another and to the unity of the whole. / Enumerate its major parts in their order and relation, and outline these parts as you have outlined the whole. (p. 76)

Rule 4. Find out what the author’s problems were. / Define the problem or problems the author has tried to solve. (p. 92)

Stage 2: What Is Being Said in Detail, and How?

Rule 5. Find the important words and through them come to terms with the author. / Come to terms with the author by interpreting his key words. (p. 98)

Rule 6: Mark the most important sentences in a book and discover the propositions they contain. / Grasp the author’s leading propositions by dealing with his most important sentences. (p. 120)

Rule 7: Locate or construct the basic arguments in the book by finding them in the connections of sentences. / Know the author’s arguments, by finding them in, or constructing them out of, sequences of sentences. (p. 120)

Rule 8: Find out what the author’s solutions are. / Determine which of his problems the author has solved, and which he has not; and as to the latter, decide which the author knew he had failed to solve. (p. 135)

Stage 3: Is It True? What of It?

General Maxims of Intellectual Etiquette

Rule 9: You must be able to say, with reasonable certainty, “I understand,” before you can say any one of the following things: “I agree,” or “I disagree,” or “I suspend judgment.” / Do not begin criticism until you have completed your outline and your interpretation of the book. (pp. 142-143)

Rule 10: When you disagree, do so reasonably, and not disputatiously or contentiously. (p. 145)

Rule 11: Respect the difference between knowledge and mere personal opinion, by giving reasons for any critical judgment you make. (p. 150)

Special Criteria for Points of Criticism

12. Show wherein the author is uninformed.

13. Show wherein the author is misinformed.

14. Show wherein the author is illogical.

15. Show wherein the author’s analysis or account is incomplete.

March 5, 2017

World Magazine’s Book of the Year in Accessible Theology

Congratulations to Andrew and Rachel Wilson, whose book The Life We Never Expected: Hopeful Reflections on the Challenges of Parenting Children with Special Needs (Crossway, 2016; foreword by Russell Moore) is World Magazine’s Book of the Year in the category of accessible theology.

Susan Olasky writes:

The Wilsons begin their short but powerful book in an arresting way: “This is a book about surviving, and thriving, spiritually when something goes horribly wrong.” Their somethings are two children, apparently normal at birth, who developed regressive autism, losing over time their ability to do the normal things that children do. The Wilsons invite readers into the messy reality of their lives, their exhaustion, and the strains on their marriage. They paint a picture of difficult yet delightful children. And they show how they make sense of their lives in the light of Christ. The book carries the reader through cycles of weeping, worshipping, waiting, and witnessing. It’s theologically rich and full of hope that in the face of many unknowns “the future will include the grace, blessing, and goodness of God.”

For more on the book, see this written interview with TGC and TGC review (it was TGC’s Book of the Year in the category of Christian Living), along with this podcast interview with the Wilsons, hosted by Alastair Roberts.

[For other categories in the World Magazine Books of the Year, go here.]

Here are some more endorsements of the work:

“What a great book! Andrew and Rachel’s surprise journey with their two autistic children opened the door to knowing God and his ways more deeply. They learned, or should I say experienced, that the gospel isn’t something you just believe; it is something you inhabit when God permits long-term suffering in your life. I’d recommend this book even if your family doesn’t have a child affected by disability—it is soul food.”

—Paul E. Miller, Executive Director, seeJesus; author, A Praying Life and A Loving Life

“The Life We Never Expected is an honest, confessional, and hopeful book. It doesn’t flinch from telling the whole truth about the trials of parenting special-needs children, and it reminds us of our need for the gospel every day. This isn’t a book that’s going to tell you to pull yourself up by your bootstraps and try harder. This is a book for those who are on the floor, weeping, because they need to know Jesus is with them.”

—Russell D. Moore, President, Southern Baptist Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission

“This is a helpful book both for those experiencing disability in their families and for those who love such families—not because of how the Wilsons are ‘dealing’ with disability but in how they rightly orient to our great and purposeful God. Having parented a child with multiple disabilities for more than two decades, I smiled regularly at their honest portrayal of life with disability. Anger, disappointment, and confusion along with delight and insight are offered in right measures. As both Andrew and Rachel point out, families like ours frequently do not experience the ‘great resolution’ about the circumstances of our lives, but we can always trust the promises of the One who made and sustains us and who will ultimately make all things new.”

—John Knight

“I am not a parent of children with special needs. In fact, I’m not a parent at all. Even so, I couldn’t put this book down. The Life We Never Expected is about so much more than parenting. It is about loss, lament, hope, humility, contentment, joy—and about finding God to be more than sufficient through it all.”

—Karen Prior, Professor of English, Liberty University, Lynchburg, Virginia

“This is a poignant and delightfully forthright book, written by parents who are still clearly raw from their experiences. Here is hard-earned wisdom, biblical realism, and winning sensitivity. Recommended for all in the throes of suffering and for all who would comfort them.”

—Michael Reeves, Director of Union and Senior Lecturer, Wales Evangelical School of Theology

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers