Michael A. Ross's Blog, page 7

August 5, 2014

The Arrest of the “Voudous”: African-American...

The Arrest of the “Voudous”: African-American Leaders’ Conflicted Response to Police Tactics in the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case of 1870

During Reconstruction, the biracial police force of New Orleans responded to the rumors that Mollie Digby, the kidnapped daughter of Irish immigrants, had been captured for use as a human sacrifice. The police arrested more than a dozen “prominent Voudous,” even when it was clear the women had no connection to the crime. “Their influence over the negro population is such,” the New Orleans Times said of the female Voodoo detainees, “that with proper appliances the truth may be brought out.”

Many African Americans viewed the arrest and interrogation of black women with ambivalence. On the one hand, they wanted the integrated Metropolitan Police to succeed and felt the force was being unfairly criticized as being ineffective by the white press. On the other hand, they thought officers were unjustly harassing black women. In late June, the John Brown Pioneer Radical Republican Club, a leading black political organization from the Digbys’ Third Ward neighborhood, issued a public proclamation about the case. The club’s members were staunch supporters of Radical Reconstruction who had campaigned to remove the words “white” and “colored” from the state’s laws and who funded lawsuits against inns, hotels, restaurants, and other businesses that denied club members equal service. They felt torn as black policemen aggressively interrogated many of their neighbors. In their proclamation they asked whether the police had convincing evidence “that the child of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Digby was kidnapped by a colored woman” and wondered whether the Digby case was being used “to create prejudice and distrust against the colored people as a class.” At the same time, they asserted that the Metropolitans were “as efficient a police corps as can be found in any city” and were “making use of all means in human power to bring the guilty to justice.” The reactionary white press quickly picked up on this apparent contradiction and lampooned the “Sable John Brown Club” for “its praise of the police who, it complains, have been guilty of unjustly arresting thirty colored women.”

August 2, 2014

Allegations of Voodoo and human sacrifice in the Great New...

Allegations of Voodoo and human sacrifice in the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case (Mobile Register 1870)

During the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case of 1870, the rumor circulated that Voodoo practitioners had abducted Mollie Digby for use as a ceremonial human sacrifice. The rumor tapped into white New Orleanians’ longstanding fear of Voodoo priests and priestesses. Before the Civil War, government officials worried that Voodoo leaders such as Marie Laveau and her daughter Marie the Second could incite slave revolts. Their presence destabilized the racial status quo that had bolstered slave society.

After Appomattox, Voodoo men and women took advantage of freedom that came with Reconstruction to practice their religion openly. Although Voodoo practitioners considered themselves to be Catholics, many frightened white residents saw the postwar Voodoo renaissance as yet another example of impending social chaos. White reactionaries, vowing to fight the “Africanization” of the city, used sensationalized accounts of Voodoo rituals to malign black culture and to portray black people as unfit to vote or govern. White editors demanded that Voodoo priests and priestesses “be closely observed by the police to prevent the intolerable excesses to which their ignorance and fanaticism lead.” For many of the city’s white residents, the Digby rumors confirmed those fears. During Reconstruction, one commentator warned, black people had “passed so much out of, and beyond the influence of white civilization” that “Voudouism” was flourishing. “It is horrible to think,” he added, “that the little child of Mr. Digby has been sacrificed to this savage superstition.”

As the hysteria grew, one editor after another demanded that what became known as “The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case” be solved.

July 29, 2014

The Elite Women of New Orleans, the “Boy Governor,”...

The Elite Women of New Orleans, the “Boy Governor,” and the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case of 1870.

As coverage of the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case became more sensational, prominent white women from the most famous New Orleans families adopted the Digby case as their own. In late June and early July wealthy women of New Orleans would usually be preparing to leave town for cooler climes. Just as many theaters and restaurants closed for the season each summer, elite families put linen covers on furniture, packed white dresses, suits, and Panama hats into trunks, and set off by rail and steamboat for the coast, the North, or Europe. But in 1870, Matilde Ogden, Armantine Allain, Louisa Huger, and wives of dozens of the city’s other richest financiers, merchants, and cotton factors took time to march to police headquarters to demand resolution of the Digby case.

By intertwining themes of motherhood, crime, and race, the Digby case provided an opportunity for the city’s elite women to enter the public debate over Reconstruction and to express publicly their anger at Governor Henry Clay Warmoth, his biracial police force, and the emerging racial order in Louisiana. Raised in a culture that required them to behave as traditional ladies, most elite women left public commentary on politics, business, and civic affairs to men. But in early July, sixty-one prominent women presented a petition to Warmoth urging him to do something to solve the case.

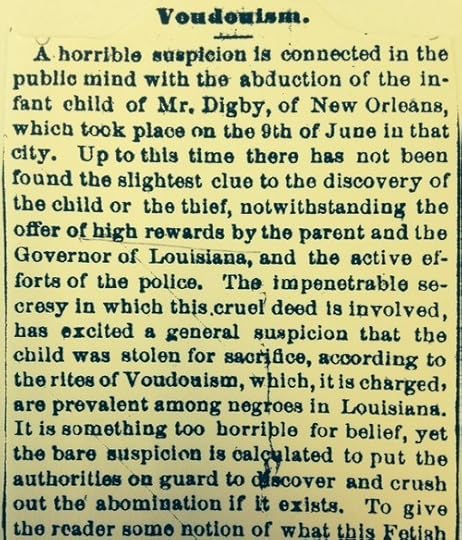

Warmoth knew that many white Louisianans questioned his qualifications and abilities. He had just turned twenty-eight years old that May and was one of the youngest governors in United States history. His critics dubbed him “the boy governor.” Wanting desperately to prove the competence of his integrated government to the city’s elite, Warmoth responded by becoming personally involved in the Digby investigation. Shortly after receiving the women’s petition, he offered a state reward of $1,000 (about $20,000 in 2014 dollars) in the Digby case—$500 for recovery of the child and $500 for the arrest and conviction of the abductors. He also ordered New Orleans’s chief of police to put the city’s entire police force “on watch” for the baby and kidnappers, and to send handbills describing the crime, the perpetrators, and the reward to postmasters and police authorities in Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and the rest of Louisiana.

July 26, 2014

African-American Policemen and Detectives Played an Important...

African-American Policemen and Detectives Played an Important Role in Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case of 1870.

July 21, 2014

The Afro-Creole Detective: John Baptiste Jourdain and The Great...

The Afro-Creole Detective: John Baptiste Jourdain and The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case of 1870.

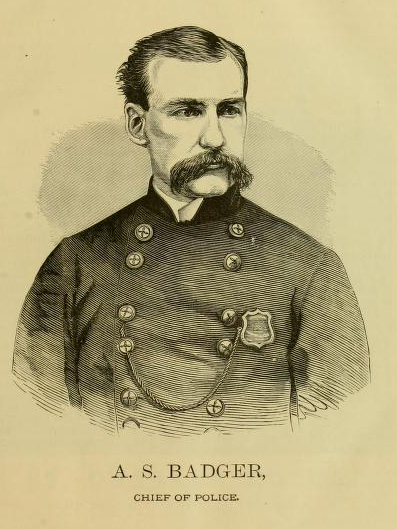

In the summer of 1870, John Baptiste Jourdain became the first African American detective ever to make national news. New Orleans Chief of Police Algernon Badger made Jourdain lead detective in the sensational Digby kidnapping case, in part, for political reasons. 1870 was the height of Radical Reconstruction and the New Orleans police force had just been integrated. If a black detective found the Digby baby or her abductors, Badger hoped it might dispel white fears that black law officers were not up to the task.

Detective Jourdain was forty years old and relatively new to the police force when he was thrust into the national spotlight. He was tall, grey-eyed, delicately featured, and dapper. The press described him as “intelligent and well-educated.” Born in New Orleans in June 1830, Jourdain was the son of a free woman of color who had once been enslaved and a white Creole descendant of one of Louisiana’s founding families. Relationships like his parents’ were common in pre-Civil War New Orleans, where wealthy, white, Francophone men often had children with “mulatto” partners. Unlike the Americans who had settled in New Orleans after the United States acquired Louisiana in 1803 who opposed racial “amalgamation,” Jourdain’s parents were part of a lingering French and Spanish colonial culture that tolerated interracial relationships.

As a Creole of color, Detective Jourdain belonged to a class of mixed-race men and women unique to the Gulf Coast. Although the term creole had different meanings in different societies, in colonial Louisiana anyone born in the colony was called a Creole. Over time, Louisianans, black and white, who identified with French culture and language and feared being overwhelmed by the American parvenus who arrived in New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase, self-identified as Creoles. Black Creoles of Jourdain’s class considered themselves to be cosmopolitan gentlemen and ladies. Bilingual and mannerly, they looked to Paris for aesthetic inspiration. Many elite Afro-Creole men wore stylish silk pants, leather slippers, and fine jackets. They dined with silver utensils, filled their homes with books and mahogany furniture, attended the opera, published their own newspaper, studied classical literature, formed exclusive Masonic lodges, and drew inspiration from the egalitarian ideals of the French Revolution. Their ranks included writers, poets, painters, sculptors, and composers, as well as doctors, merchants, and skilled artisans.

During Reconstruction, Louisiana’s Republican Governor Henry Clay Warmoth counted on educated Afro-Creoles to fill key positions in his biracial administration and Warmoth knew no roles were more important than those in law enforcement. The Republican government had to prove that it could ensure the safety of persons and property. While rough and illiterate men had previously dominated the police ranks, Warmoth and Chief Badger wanted only educated, healthy, honest, and diligent officers who would lead by example and uphold Victorian ideals of manly self-restraint. New regulations prohibited officers from using “coarse, profane, or insolent language” and required them to “set an example of sobriety, discretion, skill, industry, and promptness.” Rules required officers to pay their debts on time, to “be quiet, civil and orderly,” and to “maintain decorum and command of temper.” These skills were second nature for Afro-Creoles like Jourdain who had long relied on their manners and erudition to distinguish themselves from slaves and poor whites. Jourdain could now use those skills to further his career and to demonstrate that African Americans deserved full equality.

For Jourdain and other Creoles of color, Radical Reconstruction provided a singular opportunity to prove that they numbered amongst society’s “best men.” Given the right to vote, hold office, and serve on juries, Afro-Creoles seized the moment. Confident that men of their class could govern as well as (or better than) white men, Creoles ran for office, accepted patronage posts, or, like Jourdain, joined the integrated police force. During Reconstruction, almost all of the black elected officials from New Orleans and 80 percent of the black officers on the Metropolitan Police came from the Afro-Creole community. Afro-Creoles took on these roles knowing that their success or failure could affect the status of all black people in Louisiana. If they failed, they would confirm the prejudices of ex-Confederate reactionaries bent on restoring white supremacy. If they succeeded, they might convince moderate whites to join a biracial coalition committed to economic prosperity and democratic rule. Jourdain immediately helped the cause by leading several successful investigations that received notice in the newspapers, including a case that led to the arrest of two jewel thieves. But the public pressure to solve the Digby case would be far greater than anything Jourdain had experienced. The press so sensationalized the Digby kidnapping that it became a crime that could not go unsolved.

(Note: No known image of Detective Jourdain exists. The drawing above is of Afro-Creole musician and composer M.Basile Barres and is included as an illustration of a member of the Afro-Creole class in Louisiana)

July 8, 2014

The Remarkable Detective Noble: Former Slave, Drummer Boy, Union...

The Remarkable Detective Noble: Former Slave, Drummer Boy, Union Soldier, and Trailblazing Sleuth.

In mid-July 1870, the lead detective in the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case, John Baptiste Jourdain, received a tip that a former slave named Rosa Lee knew of the whereabouts of the kidnappers he sought. Because policemen were “invariably met with silence and suspicion” in black neighborhoods, Jourdain hoped he could dress in workman’s clothes and trick Lee into divulging what she knew about the case. As a light-skinned Creole of color from a privileged background, Jourdain would need to play his role well by adopting the mannerisms of a freedman. To lend authenticity to his disguise, Jourdain brought along gray-haired Detective Jordan Noble who, at age seventy-two, was the oldest man on the force and one of the few former slaves in the ranks of the Metropolitan Police.

Detective Noble was famous in New Orleans and perhaps an odd choice for an undercover assignment. Born into slavery in Georgia, Noble had earned his freedom after serving as Andrew Jackson’s drummer boy at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. He later accompanied Louisiana troops in the Everglades during the Seminole War, as well as serving as drummer for the elite New Orleans-based Washington Artillery during the Mexican War. In the 1850s, Noble regularly marched with his drum in patriotic parades alongside white veterans who nicknamed him “Old Jordan.” When the Civil War began, he helped organize one of the regiments that volunteered to fight with the Confederacy, but he later switched sides and served in the Union ranks. Like Jourdain, Noble seized the opportunity during Reconstruction to join the Metropolitan Police as a detective, and despite Noble’s celebrity Jourdain believed that he and Noble, like the famous French detectives they emulated, could be “masters of disguise.”

Dressed in grubby work clothes, the two detectives made their way to the neighborhood near the back-swamps where Rosa Lee lived. When they found Lee standing outside of her house, the detectives’ deception began.

July 3, 2014

The First African-American Detectives, The Great New Orleans...

The First African-American Detectives, The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case, and the Fate of Reconstruction

When police departments in the mid-twentieth-century appointed African-American detectives, the nation took note. Through countless books, movies, and television shows, detectives had become the most glamorous figures in law enforcement, and the appointment of black detectives—first in the North and then in the South—was seen as a sign of a transforming society. Sidney Poitier’s portrayal of Philadelphia homicide detective Virgil Tibbs in the 1967 film In the Heat of the Night became iconic. But few commentators noted at the time that the trailblazing African- American detectives of the Civil Rights Era were not the first black detectives in American History. That honor goes to the black “special officers,” as detectives were often called, who served in a handful of cities in the South during Reconstruction. In Reconstruction-era New Orleans, for example, John Baptiste Jourdain, Jordan Noble, and other black detectives investigated high profile crimes including the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case of 1870.

Until the mid-1840s, American urban police forces did not employ detectives at all; before then, the role of policemen, night watchmen, and town constables was to prevent crimes, not to solve them. Cities usually depended on common citizens to identify criminals. Even with the rise of professional policing in the 1830s, officers focused their energies on prevention and made most arrests based on evidence that witnesses had voluntarily brought forth. After Boston introduced the first detective squad in 1846, other American cities, including New Orleans, followed suit, and detectives soon became celebrated figures. Stories, both real and fictional, of whip-smart sleuths deciphering clues, using disguise, spotting telltale signs, and outsmarting wily criminals captured the American imagination. True crime tabloids like the National Police Gazette, as well as the short stories of Edgar Allan Poe, helped propel the national obsession with detective work.

But until Reconstruction, all police detectives in the United States

had been white. Even in 1870, police departments in the North still had not hired black patrolmen, let alone detectives. The Boston force would not add a black officer until 1878; in New York City, the ranks remained all-white until 1911. But in the South, five cities employed black officers. Reconstruction, it seemed, had brought real change; only a few years earlier, the idea of a black man serving on a southern police force in any capacity would have been unthinkable. But in 1870 in New Orleans, black detectives followed leads, interrogated white and black witnesses, and used their deductive skills in efforts to solve sensational crimes like the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case. More was at stake, of course, than simply solving crimes. If they succeeded, black detectives could help convince skeptical whites that biracial government could work. If they failed, however, they would arm the critics who demanded the restoration of white supremacy.

June 27, 2014

The “Carpetbagger” Police Chief and the Dream of an Integrated...

The “Carpetbagger” Police Chief and the Dream of an Integrated New Orleans.

White southerners called them “carpetbaggers.” They were Yankees in the post-war South: former Union Army soldiers, Freedmen’s Bureau agents, lawyers, and businessmen who, white southerners alleged, were there to enrich themselves at the expense of the defeated Confederate states. Many of the so-called carpetbaggers, however, were principled men who believed they were doing God’s work. They hoped that with northern guidance the old slaveholding South could be reconstructed in the North’s image and might soon be crisscrossed with railroads and filled with mills, factories, public schools, and prosperous free laborers.

Included in this idealistic group in 1870 was the Massachusetts-born police chief in New Orleans, thirty-one-year-old Algernon Sidney Badger. A tall, powerfully built Union Army veteran, Badger oversaw the integration of the New Orleans police force during Reconstruction and he was eager to demonstrate that his black officers and detectives could effectively and fairly protect the public’s safety. When the kidnapping of Mollie Digby made headlines that spring, Badger appointed his best black detectives to the case. Although many ex-Confederates could not stand the thought of armed black policemen patrolling the streets with full authority to arrest whites, Badger hoped that by solving a high-profile, racially explosive case his men could build public confidence in his integrated force.

Badger was not naive. He knew well the challenges he faced; he had seen firsthand the ferocious animosity many white southerners held for northerners. In April 1861, an angry, gun-wielding mob had attacked Badger’s 6th Massachusetts Infantry as the men changed trains in Baltimore en route to Washington in response to President Lincoln’s first call for volunteers. Four of Badger’s comrades had died in the Pratt Street melee. As a civilian in New Orleans after the war, he had witnessed ex-Confederates shooting unarmed black men and their white allies during the 1866 New Orleans Riot. Badger nevertheless believed that in a city long known for its corrupt and thuggish police force, professional and honest policing could help win over moderate whites. Successfully solving the Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case of 1870 became key to Badger’s campaign.

June 20, 2014

The Kidnapping that Captivated the Country

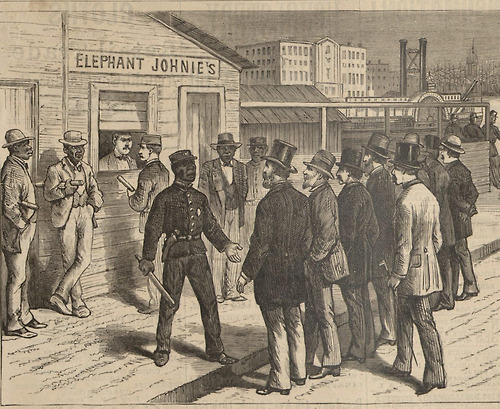

New Orleans was a city on edge in June 1870 when two African American women abducted 17-month-old Mollie Digby from in front of her family’s home in the working-class “back of town.” It was the height of Radical Reconstruction. Former slaves, freed during the Civil War, had poured into the city and African American men could now vote, serve on juries, and hold public office. Black men and women demanded service in formerly whites-only restaurants and saloons. Many white residents, still emotionally wounded by Confederate defeat, seethed as the new order emerged.

When the police reported that Mollie Digby, the daughter of Irish immigrants, had been kidnapped by a “fashionable, tall, mulatto woman, probably for the purpose of receiving a ransom,” the white press seized on the case as an example of a world turned dangerously upside down. They demanded that Louisiana’s Reconstruction government solve the crime.

News of the kidnapping spread throughout the South and made headlines in Chicago, New York, and other cities as the story, and the efforts to find Mollie Digby, became intertwined with the fearsome politics of Reconstruction. “The Great New Orleans Kidnapping Case” had begun.

To be published by Oxford University Press, October 2014