Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 45

July 14, 2015

Sherfy's Peaches

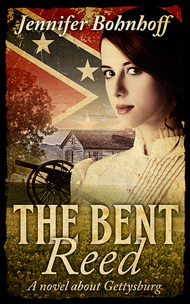

One of the reasons that fruit trees figure fairly prominently in The Bent Reed is that they figure prominently in many diaries of the period. By late June 1863, the Civil War had been raging long enough that many of the farmlands of the South were in disarray. The Confederate soldiers who invaded Pennsylvania on their way to the Battle of Gettysburg delighted in the produce and animals on the North’s untouched farms, and wrote about Pennsylvania’s green bounty.

One of the reasons that fruit trees figure fairly prominently in The Bent Reed is that they figure prominently in many diaries of the period. By late June 1863, the Civil War had been raging long enough that many of the farmlands of the South were in disarray. The Confederate soldiers who invaded Pennsylvania on their way to the Battle of Gettysburg delighted in the produce and animals on the North’s untouched farms, and wrote about Pennsylvania’s green bounty. Before the Civil War, almost every farm had a small apple orchard that was used to produce cider, fruit for the home, and food for pigs. With new roads, canals and railroads providing better transportation, many farmers in the Gettysburg area began expanding their orchards in the 1840s and 1850s to produce fruit for the growing urban markets.

Joseph Sherfy, 1840s. One example of this new, enterprising farmer was the Reverend Joseph Sherfy, who purchased 50 acres along the Emmitsburg Road, south of the town of Gettysburg, in 1842. Sherfy planted much of his land in peach trees, and by the time of the Civil War, his fresh, dried, and canned peaches were locally famous.

Joseph Sherfy, 1840s. One example of this new, enterprising farmer was the Reverend Joseph Sherfy, who purchased 50 acres along the Emmitsburg Road, south of the town of Gettysburg, in 1842. Sherfy planted much of his land in peach trees, and by the time of the Civil War, his fresh, dried, and canned peaches were locally famous. Joseph and Mary Sherfy and their six children were ready to help when the Union army reached Gettysburg on the first of July 1863. Joseph dragged a large water tub out to the road and kept it filled for the thirsty soldiers. Mary and her mother baked loaf after loaf of bread and handed them over to the army. The next day they were forced to evacuate their home. Their home ended up being the center of the whirlwind of war on July 2nd and 3rd, which is the reason I chose to put the fictional McCoombs farm right next to Sherfy’s farm.

The Sherfy farm was in the thick of things because Union General Dan Sickles disobeyed his commanding officer, General George Meade. He moved his men onto a piece of high ground in the middle of the orchard instead of keeping them in a line that extended south of the town of Gettysburg to a hill called Little Round Top. This created a sharp bend in the line, a vulnerable salient that the Confederate army attacked from two sides. The fight in the peach orchard was one of the most hotly contested of the Gettysburg battle.

The Sherfy farm was in the thick of things because Union General Dan Sickles disobeyed his commanding officer, General George Meade. He moved his men onto a piece of high ground in the middle of the orchard instead of keeping them in a line that extended south of the town of Gettysburg to a hill called Little Round Top. This created a sharp bend in the line, a vulnerable salient that the Confederate army attacked from two sides. The fight in the peach orchard was one of the most hotly contested of the Gettysburg battle. When Sherfy returned to his land on the 6th, he discovered that his house had been ransacked. At least seven artillery shells had hit it. The yard was covered with the family’s possessions, churned into the mud with body parts left over from the Confederate field hospital that had been in their barn. Bodies of dead men and horses lay strewn about everywhere. The ruins of the barn were filled with the charred remains of the men who had been unable to escape the fire that occurred when shells of the Union batteries scored a direct hit.

Undaunted, the Sherfys cleaned, replanted, and rebuilt, and for years sold peaches from the famous orchard.It was a popular destination for veterans who had fought in its fields and wanted to relive their experiences. One wall of the house supposedly was covered with photographs of veterans who had fought there. The farm today, which still has some holes from artillery shells, is owned by the National Park Service. At some point in the late 19th or early 20th century the peach trees were all removed, but the National Park Service restored them about 15 years ago, and Sherfy's Peaches are again being sold at Gettysburg.

Published on July 14, 2015 09:34

July 6, 2015

Quirky Ideas from the WWI History Museum

The reflecting pool at the museum's entrance. When I went to the National World War I Museum in Kansas City last May, I was delighted by quirky artifacts that really got me thinking. I wouldn't be surprised if some of them make it into a future novel, because they would add great depth and detail to a narrative.

The reflecting pool at the museum's entrance. When I went to the National World War I Museum in Kansas City last May, I was delighted by quirky artifacts that really got me thinking. I wouldn't be surprised if some of them make it into a future novel, because they would add great depth and detail to a narrative. Here are a few of my favorites:

This projectile from a from a French 58 mm trench mortar was nicknamed the "Flying Pig" because of what it looked like in the air.

This projectile from a from a French 58 mm trench mortar was nicknamed the "Flying Pig" because of what it looked like in the air.The Flying Pig was used by French, Belgian, and U.S. troops and had a range of 490 yards.

The video below isn't of a Flying Pig, but of an Australian trench mortar.

If I ever write a novel set in the trenches of World War I, I have GOT to have a Flying Pig in it!

This Austrian helmet was sent home as a souvenir by an American. Back then, I guess the postal service had less restrictions than now, because no box or packaging was required to get this helmet from Europe to the U.S. The soldier (I'm assuming it was a soldier. It could have been a sailor or a relief worker for all I know.) Simply attached a tag with his mother's (girlfriend's? sisters?) Kansas City address and stuck stamps directly to the helmet. I hope I find a character with enough spunk and creativity to think about sending home souvenirs like this!

This Austrian helmet was sent home as a souvenir by an American. Back then, I guess the postal service had less restrictions than now, because no box or packaging was required to get this helmet from Europe to the U.S. The soldier (I'm assuming it was a soldier. It could have been a sailor or a relief worker for all I know.) Simply attached a tag with his mother's (girlfriend's? sisters?) Kansas City address and stuck stamps directly to the helmet. I hope I find a character with enough spunk and creativity to think about sending home souvenirs like this!  This is an Imperial German Border sign. Made of painted cast iron, a series of these marked the border between Germany and France.

This is an Imperial German Border sign. Made of painted cast iron, a series of these marked the border between Germany and France.In August of 1914, an elite French strike force penetrated the border on the southern flank of the engagement, capturing many of these border signs.

Can you imagine a young Frenchman bringing this home to his maman? Am I planning to write a book set in World War I? Not at present. Right now, I'm finishing a final edit on a young adult novel that has two concurrent settings: Swan Song switches back and forth between a modern high school girl and a girl living in Europe during the Ice Age. I'm also researching a book which will be set in New Mexico during the Civil War. But I'm always musing what comes next, especially when I see something quirky that brings the period to life!

Published on July 06, 2015 08:52

June 29, 2015

The best place in America to Look back at World War I

Last month I had the joy of visiting the National WWI Museum and Liberty Memorial in Kansas City. If you are at all interested in the war that changed the world a hundred years ago, this is the place to visit in America.

Last month I had the joy of visiting the National WWI Museum and Liberty Memorial in Kansas City. If you are at all interested in the war that changed the world a hundred years ago, this is the place to visit in America.The Liberty Memorial was created in the 1920's through the subscription of Kansas City's citizens. Perched high on a grassy hill, this Beaux Arts and Egyptian Revival memorial consists of a 266 ft tower topped by four 40 foot tall figures who are the Guardian Spirits. Each figure holds a sword. They represent Honor, Courage, Patriotism and Sacrifice.

Two sphinxes flank the tower. "Memory" faces east, towards the battlefields of France. "Future" faces west. Both shield their eyes with their wings: one hiding from the horrors of war, the other symbolizing that the future is unknown and unseen.

Two sphinxes flank the tower. "Memory" faces east, towards the battlefields of France. "Future" faces west. Both shield their eyes with their wings: one hiding from the horrors of war, the other symbolizing that the future is unknown and unseen.  Two halls face toward the tower. One is Memory Hall, which has some of the most beautiful friezes I have ever seen. Exhibit hall houses some of the collection of the museum, which rests underground, beneath the Memorial.

Two halls face toward the tower. One is Memory Hall, which has some of the most beautiful friezes I have ever seen. Exhibit hall houses some of the collection of the museum, which rests underground, beneath the Memorial.Liberty Memorial is noble and somber. It is epic in scale. But what rests beneath it in the museum is even more awe-inspiring.

Published on June 29, 2015 10:03

June 23, 2015

Eating in a Different Era

When I toured the National World War I Museum in Kansas City last month, I ate at their museum cafe. It was a different kind of experience.

When I toured the National World War I Museum in Kansas City last month, I ate at their museum cafe. It was a different kind of experience.Most museums have cafes for their patrons. Most serve the same, ubiquitous dinning room food: cold wraps or sandwiches from a glass case, salads, bags of chips. Some of the fancier ones might have a grill that serves up burgers. But this cafe was different.

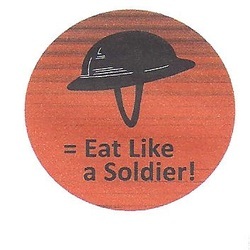

The Menu for the Over There Cafe had a little symbol in its upper right corner: an orange circle with a helmet. It said that the helmet next to a menu item meant that the food was similar to that served to soldiers during World War I. Minus, of course, the bugs and dirt.

The Menu for the Over There Cafe had a little symbol in its upper right corner: an orange circle with a helmet. It said that the helmet next to a menu item meant that the food was similar to that served to soldiers during World War I. Minus, of course, the bugs and dirt.I had to choose between chipped beef on gravy over toast (which my WWI grandfather called "shit on a shingle," a mix of corned beer, turnips and carrots called trench stew, cabbage soup, or army goulash: a mix of hamburger, pork and beans, oregano and tomato sauce.

I ordered a cup of coffee and trench stew, which came with a side of WWI slaw and a biscuit served on a tin plate. The stew came in a glass-covered sauce pot. Perhaps serving the stew and coffee in battered tin cups would have been more authentic. Recently I sent a recipe for triple ginger cookies to people on my friends, family and fans email list. One friend wrote back, suggesting that I incorporate period recipes in my historical novels. I think she may be on to something. What do you think? Should I include recipes in my historical novels? post them on my blog? Send them to people who are on or Sign up for my friends, family and Fans email list? Name * First Last Email * Comment * Submit

I ordered a cup of coffee and trench stew, which came with a side of WWI slaw and a biscuit served on a tin plate. The stew came in a glass-covered sauce pot. Perhaps serving the stew and coffee in battered tin cups would have been more authentic. Recently I sent a recipe for triple ginger cookies to people on my friends, family and fans email list. One friend wrote back, suggesting that I incorporate period recipes in my historical novels. I think she may be on to something. What do you think? Should I include recipes in my historical novels? post them on my blog? Send them to people who are on or Sign up for my friends, family and Fans email list? Name * First Last Email * Comment * Submit

Published on June 23, 2015 13:58

June 15, 2015

liberty born in a swamp!

Today marks the 800th anniversary of the western world's concept of liberty. The idea was born in a swamp.

Today marks the 800th anniversary of the western world's concept of liberty. The idea was born in a swamp.On June 15, 1215, in a place called Runnymede, King John signed the Magna Carta, the Latin name for the Great Charter that Daniel Hannan calls "the most important bargain in the history of the human race." Not only did the charter formalize the notion of freedom of an individual against the arbitrary authority of a despot, but it instituted a from of conciliar rule that was the progenitor of England's Parliament and America's Legislative Branch.

The Magna Carta was written by a group of rebellious barons who wanted to protect their rights and property from the overzealous taxation of the cash-poor King John. Before he was king, England's coffers were emptied by those seeking to ransom John's brother, Richard the Lionheart, who had been captured by a German prince on his way back to the Holy Land. Once crowned, John threw himself into battle with France in an attempt to regain the lands traditionally held by his family, the Angevins. John was not a good military leader, and suffered a series of staggering blows that resulted in the loss of all French lands for he English crown

When the defeated John returned from the Continent, he tried to rebuild his coffers by demanding scutage, a fee paid in lieu of military service, from the barons who had not joined him in war. The barons refused, and 40 joined in open rebellion. After they captured London, the barons forced John to meet with them at Runnymede and put his seal to the charter that protected their feudal rights.

Attribution: WyrdLight.com Runnymede isn't really a swamp, but a water-meadow in what is called the 'Thames Basin Lowland.' 20 miles south and west of London, this area of gently rolling hills and vales is filled with ponds, meadows, and heath.

Attribution: WyrdLight.com Runnymede isn't really a swamp, but a water-meadow in what is called the 'Thames Basin Lowland.' 20 miles south and west of London, this area of gently rolling hills and vales is filled with ponds, meadows, and heath.Its name comes from a combination of the Anglo-Saxon word 'runieg,' which means regular meeting, and 'mede,' which means meadow. During the time of Anglo-Saxon rule, from the 7th to 11th centuries, the Witan, or King's Council, met in the open air at Runnymede. It is not surprising, then, that John's Barons would choose this site to reassert their ancient rights and privileges.

The Barons didn't really care about the interests of the common man when they had John place his seal on their charter. But two principles expressed in the Magna Carta resonated with the founders of America. Both "No freeman shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or in any way destroyed, nor will We proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land" and "To no one will We sell, to no one will We deny or delay, right or justice" sound awfully American to most ears.

The Barons didn't really care about the interests of the common man when they had John place his seal on their charter. But two principles expressed in the Magna Carta resonated with the founders of America. Both "No freeman shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or in any way destroyed, nor will We proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land" and "To no one will We sell, to no one will We deny or delay, right or justice" sound awfully American to most ears.For a translation of the Magna Carta in to English, click here.

Published on June 15, 2015 09:47

June 10, 2015

Thunder reverberates

Towards the end of the school year I was visiting with a fellow teacher when I noticed a book on her book rack. The cover was so intriguing that I had to borrow the book and take it home to read.

Towards the end of the school year I was visiting with a fellow teacher when I noticed a book on her book rack. The cover was so intriguing that I had to borrow the book and take it home to read.

The book was entitled Thunder at Gettysburg, and it was written by Patricia Lee Gauch in the 1970's. Ms. Gauch went on to become a prominent and very influential editor. During her career she edited three Caldecott books: Owl Moon by Jane Yolen, illustrated by John Schoenherr, Lon Po Po by Ed Young and So You Want to Be President by Judith St. George, illustrated by David Small. She authored 39 book of her own. And although I'm sure she doesn't remember it, she rejected my manuscript for The Bent Reed, my Gettysburg novel intended for a slightly older readership, back in 2004.

The book was entitled Thunder at Gettysburg, and it was written by Patricia Lee Gauch in the 1970's. Ms. Gauch went on to become a prominent and very influential editor. During her career she edited three Caldecott books: Owl Moon by Jane Yolen, illustrated by John Schoenherr, Lon Po Po by Ed Young and So You Want to Be President by Judith St. George, illustrated by David Small. She authored 39 book of her own. And although I'm sure she doesn't remember it, she rejected my manuscript for The Bent Reed, my Gettysburg novel intended for a slightly older readership, back in 2004.

Thunder at Gettysburg is a simple little chapter book written for elementary-age students who have mastered easy readers. It is tells the story of one girl's experience and is based on the memoir of Tillie Pierce, who witnessed the Battle of Gettysburg when she was a young girl. More than 20 years after the battle, she wrote her memoir, which I read as part of my research. Tillie actually shows up in a crowd scene in my book: she is named in a group of girls who went to the ladies seminary,which was a finishing school, and are waving flags during a Union parade through town. I got the description of the parade from her memoir.

Thunder at Gettysburg is a simple little chapter book written for elementary-age students who have mastered easy readers. It is tells the story of one girl's experience and is based on the memoir of Tillie Pierce, who witnessed the Battle of Gettysburg when she was a young girl. More than 20 years after the battle, she wrote her memoir, which I read as part of my research. Tillie actually shows up in a crowd scene in my book: she is named in a group of girls who went to the ladies seminary,which was a finishing school, and are waving flags during a Union parade through town. I got the description of the parade from her memoir.  It's fun to read two works based on the same primary source. When you do so, if you come across a scene or turn of phrase that is common to both, it's a safe bet that the words or the scene came from the original material. Ms. Gauch's main character is Tillie, and her book is not a work of fiction but a retelling of the biography on a very simple level. My book is a work of fiction. The McCombs family doesn't exist, although most of their neighbors did. I set the fictitious family's farm right in the thick of the action, between two real farms that took a beating with actual artillery. Almost everything that happened in The Bent Reed actually did happen, but to other, real people. One of those people was Tillie Pierce.

It's fun to read two works based on the same primary source. When you do so, if you come across a scene or turn of phrase that is common to both, it's a safe bet that the words or the scene came from the original material. Ms. Gauch's main character is Tillie, and her book is not a work of fiction but a retelling of the biography on a very simple level. My book is a work of fiction. The McCombs family doesn't exist, although most of their neighbors did. I set the fictitious family's farm right in the thick of the action, between two real farms that took a beating with actual artillery. Almost everything that happened in The Bent Reed actually did happen, but to other, real people. One of those people was Tillie Pierce.

Published on June 10, 2015 16:08

May 11, 2015

Medieval Women Knights

A friend recently posted a link on my Facebook page to an article entitled Could a Woman Become a Knight in Medieval Times?

A friend recently posted a link on my Facebook page to an article entitled Could a Woman Become a Knight in Medieval Times?The article stated that when a knight died, his land passed to his wife or daughter. The woman was then responsible for the duties that went along with the land, including a certain number of days on campaign, if called up.

What the article didn't say was that usually the lady in question either hired knights to fulfill her obligation, or, even more regularly, married. Often, her liege lord would tell her who it was she would marry and she would have no say in the matter. (Birgitta finds herself in a similar situation in my medieval novel On Fledgling Wings .)

But there were women during the Middle Ages who were warriors. In "The Woman Warrior: Gender, Warfare, and Society in Medieval Europe," Women's Studies, 17, 1990, Megan McLaughlin says that women warriors were certainly more common" during the Middle Ages "than has usually been assumed,"

One example of a medieval woman warrior is Sichelgita of Salerno, a twelfth-century noblewoman who fought side by side with her husband, Robert of Hautevilleon.

Oderic Vitalis, a twelth-century historian, says that Isabel of Conches, daughter of the knight Simon de Montfort, rode armed as a knight among the knights and showed courage far greater than her husband.

Oderic Vitalis, a twelth-century historian, says that Isabel of Conches, daughter of the knight Simon de Montfort, rode armed as a knight among the knights and showed courage far greater than her husband.Oronata Rodiana, an Italian woman who died in 1452, was an artist who fought off a young nobleman who attempted to rape her. She escaped to the mountains, where she joined a group of mercenary soldiers. She died defending her town, Castelliono, years later.

Want more on women warriors? Try here.

Published on May 11, 2015 18:35

April 26, 2015

A short History of Windmills

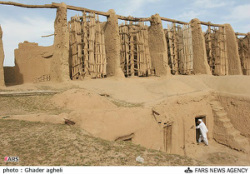

Nashtifan, the ancient city of windmills No one knows who first acted on the idea of using wind to grind grain.

Nashtifan, the ancient city of windmills No one knows who first acted on the idea of using wind to grind grain. We do know that there were windmills in Iran by the 7th century. These windmills had a long, vertical drive shaft around which rotated six to twelve rectangular, reed-covered sails. This type of device is called a "panemone" windmill.

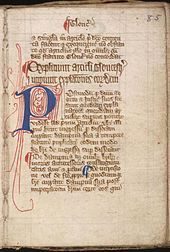

The first windmills in Northern Europe date from the 1180s and have a very different design. They are called "post" windmills because of the large upright post on which the mill's main structure, the "buck," is balanced so that the mill can rotate to catch the wind when it comes from different directions. The mill was moved using a tailpole or tiller beam that extended from the rear of the body. The picture below, from a 14th century manuscript, shows a post windmill. The two prone figures to the right make me wonder if this illustrates Chaucer's Miller's Tale, but I might be wrong since the text is in Latin and Chaucer wrote in Middle English.

Fourteenth century windmill image licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons This is the kind of windmill that Nathan Marsall had to wrestle into position in my middle grade medieval novel,

On Fledgling Wings.

Fourteenth century windmill image licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons This is the kind of windmill that Nathan Marsall had to wrestle into position in my middle grade medieval novel,

On Fledgling Wings.

It has widely been suggested that returning Crusaders brought the idea of windmills back to Europe with them. While the timing is right, the huge difference in design suggests that this might not be the case, and that windmills might have been designed independently in Europe and the Middle East. How do windmills work? Inside the mill, a shaft attaches to the sails, and called a windshaft for obvious reasons, moves a large wheel. This is called the brake wheel because it has a large wooden friction brake around its outer edge that could slow or stop the milling process. The brake wheel transferres power to a smaller gear at right angles to it. This smaller gear, called the wallower, shares a vertical shaft with a spur wheel, which drive the millstone.

By the 1300s, those who could afford it build tower mills. This type of windmills has a rotating cap that holds just the roof, the sails, the windshaft and the brake wheel while the body of the mill remains stable. They are built from stone or brick, and therefore can be built taller, allowing for larger sails and greater power. However, they were also expensive to produce.

By the 1300s, those who could afford it build tower mills. This type of windmills has a rotating cap that holds just the roof, the sails, the windshaft and the brake wheel while the body of the mill remains stable. They are built from stone or brick, and therefore can be built taller, allowing for larger sails and greater power. However, they were also expensive to produce.Photo by Francis Franklin (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The Dutch developed a better windmill in the middle of the sixteenth century. Smock mills, named after the dress-like peasants' clothing they resemble, these were large enough to be powerful, yet less expensive to build. (photo by Uberprutser (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 nl (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)]

The Dutch developed a better windmill in the middle of the sixteenth century. Smock mills, named after the dress-like peasants' clothing they resemble, these were large enough to be powerful, yet less expensive to build. (photo by Uberprutser (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 nl (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)]Windmills were a major source of power in Europe from the 1300s to the 1800s. They went out of favor with the development of steam power, and for two hundred years they have languished. However, the trend for organic and non-manufactured foodstuffs has shifted the economics slightly back in their favor once again.

Published on April 26, 2015 13:01

April 16, 2015

Not a Spring Chicken

Last fall I visited my mother and entered the house to the luscious, comforting smell of roasting chicken.

Last fall I visited my mother and entered the house to the luscious, comforting smell of roasting chicken.On the three hour drive home the next day I kept thinking about that chicken and what I could do with the leftovers. Enchiladas. Crepes. Pot pies. Tetrazzinis. Soups. My mouth watered and my mind wandered all the way home.

The next time I bought groceries I bought a chicken, but then the inevitable business of life got between it and getting it into the oven. One night I got home too late. Another night we ate out. I began thinking that maybe I needed to put it in the crock pot, but my mornings proved just as harried as my evenings.

The chicken languished in my fridge for a while. A week? Two? I'm not sure. Over time, I forgot about the chicken in the bottom bin of the fridge. What finally brought it back into my consciousness was a smell. The smell wasn't overpowering. It was just a teensy, tiny bit off, but it was definitely off.

Here I will admit that most of you are smarter than I am. Most of you would have known what to do if you'd have taken one whiff of a chicken that's sat in solitary confinement for so long. Your offending chicken would have gone directly into the trashcan. But not mine.

Call me over optimistic. Or cheap. Or stupid. Or a combination of all three, but I didn't throw away my smelly chicken. I decided that maybe, just maybe a day in the crockpot would kill whatever was making that chicken smell bad.

Instead, I came home that evening to a house filled with a stench that made me want to retch before I even got in the door. The crockpot had helped that smell multiply a thousand times over. I took the crock out and dumped its contents into the garbage, opened every window in the house and turned on every fan. We ate out that night.

A chicken is just a chicken unless you're a writer or a teacher. Then, it's liable to become a metaphor or an object lesson. What part of your life is just a teensy, tiny bit off? What failures are you holding onto in the hopes that someday you can make good on them? Sometimes it's smart to recognize that a situation or relationship isn't going to get any better, and it's time to s

Published on April 16, 2015 11:13

April 1, 2015

The Crusades: the Middle Ages for Middle Graders

By Anomyme (Livre d'heures, Londres, British Library) For many middle grade readers, the Middle Ages were exciting times! Knights on horseback! Damsels in distress! Dragons! (Forget the dragons. Contrary to popular opinion, there were no more dragons in Europe during the Middle Ages than there are now.)

By Anomyme (Livre d'heures, Londres, British Library) For many middle grade readers, the Middle Ages were exciting times! Knights on horseback! Damsels in distress! Dragons! (Forget the dragons. Contrary to popular opinion, there were no more dragons in Europe during the Middle Ages than there are now.)

Grateful Jews accept Crusader protection. One of the most exciting of times for readers of Medieval fiction is the Crusades. In 1095, Emperor Alexius I of Byzantium asked Pope Urban II for help in fighting the Seljuk Turks. Urban's call received a tremendous response from western Christians. One reason so many wanted to go was the promise of an indulgence: the forgiveness of sins for any who accepted the mission. Not only was this a free pass for anyone who wanted to act badly, but a "get out of purgatory free" card for those who wanted continued amnesty from consequences in their next life.

Grateful Jews accept Crusader protection. One of the most exciting of times for readers of Medieval fiction is the Crusades. In 1095, Emperor Alexius I of Byzantium asked Pope Urban II for help in fighting the Seljuk Turks. Urban's call received a tremendous response from western Christians. One reason so many wanted to go was the promise of an indulgence: the forgiveness of sins for any who accepted the mission. Not only was this a free pass for anyone who wanted to act badly, but a "get out of purgatory free" card for those who wanted continued amnesty from consequences in their next life.  Historians aren't completely sure what Urban asked of Europe's Christians. Many people wrote down their remembrances of his call to arms, but not until many years later. Perhaps he just asked for Europe's warriors to help Alexius repel the Turkish threat. Perhaps he asked for more. Whatever he asked for, those who went on Crusade decided that the recapture the Holy Land, especially the holy city of Jerusalem, from the Moslems was their primary focus. The Holy Land remained the central battlegrounds of the Crusades until 1291.

Historians aren't completely sure what Urban asked of Europe's Christians. Many people wrote down their remembrances of his call to arms, but not until many years later. Perhaps he just asked for Europe's warriors to help Alexius repel the Turkish threat. Perhaps he asked for more. Whatever he asked for, those who went on Crusade decided that the recapture the Holy Land, especially the holy city of Jerusalem, from the Moslems was their primary focus. The Holy Land remained the central battlegrounds of the Crusades until 1291.

The Third Crusade (1187-1197) is the one that receives the most literary attention. This is primarily due to the star power of Richard the Lionheart, whose tall frame and handsome face helped him become known as the noblest and most chivalric of England's kings.

The Third Crusade (1187-1197) is the one that receives the most literary attention. This is primarily due to the star power of Richard the Lionheart, whose tall frame and handsome face helped him become known as the noblest and most chivalric of England's kings.  Richard's primary opponent was Saladin, an extraordinary Moslem leader and war lord who managed to rally the disparate Arab and Middle Eastern Tribes into one united force even though he was a minority Kurd.

Richard's primary opponent was Saladin, an extraordinary Moslem leader and war lord who managed to rally the disparate Arab and Middle Eastern Tribes into one united force even though he was a minority Kurd.  Add to that the mystique of the Knights Templars. These men were a heady combination of warrior knight and religious monk, and, because their order was both widespread and wealthy, also became the chief financiers and bankers of the Middle Ages. The favorite figures of conspiracy theorists (think Da Vinci Code!), the Templars show up in almost every work of literature about the Crusades.

Add to that the mystique of the Knights Templars. These men were a heady combination of warrior knight and religious monk, and, because their order was both widespread and wealthy, also became the chief financiers and bankers of the Middle Ages. The favorite figures of conspiracy theorists (think Da Vinci Code!), the Templars show up in almost every work of literature about the Crusades. Want to read more about the Crusades? Check out these works of historical fiction.

Published on April 01, 2015 11:20