Daniel Orr's Blog, page 29

January 22, 2024

January 22, 1981 – The start of the Paquisha War, started when a Peruvian transport helicopter is attacked in the Comaina Valley

On January 22, 1981, the Paquisha War between Peru and Ecuadorbroke out when a Peruvian transport helicopter was fired upon in the Comaina Valley, in a Peruvian-controlled areathat had been seized by Ecuadorian troops. Subsequently, Peruvian authorities discovered that the Ecuadorians hadconstructed three outposts in the Comaina Valley along the easternslope of the Condor. The Ecuadoriansnamed their outposts Mayaicu, Machinaza, and Paquisha, with the latter for whichthe coming war was named. In anOrganization of American States (OAS) foreign ministers meeting held onFebruary 2, 1981, the Peruvian representative denounced the Ecuadorian action. Then in the next few days, Peruvian forcesattacked the outposts, forcing the Ecuadorians to withdraw to their side of theCondor Mountain Range. By February 5, Peru had regained control of the whole Comaina Valley and also seized Ecuadorianmilitary supplies and equipment that had been abandoned.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, producing tensions and wars between the two countries.

Ecuador and Peru (and other nearby South American countries) as they appear in current maps. For much of the twentieth century, the Ecuador–Peru border was incompletely demarcated, producing tensions and wars between the two countries.(Taken from Paquisha War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background InJuly 1941, Ecuador and Peru(Map 38) fought a war for possession of disputed territory located in theAmazon rainforest. After the war, bothcountries signed, in January 29, 1942, the Rio Protocol (officially called theProtocol of Peace, Friendship, and Boundaries), which called for establishingthe international border between Ecuadorand Peru. Four guarantor countries of the Rio Protocol,namely, the United States, Brazil, Argentina,and Chile,were tasked to under the border delineation process. Since much of the territory where the borderwould pass was thick Amazonian jungle, U.S. planes were brought in toundertake aerial surveys and thereby upgrade the existing Spanish colonial-eramaps of the region. Consequently, theMixed Border Commission, which was composed of technical teams from Ecuador, Peru, and the four guarantorcountries, succeeded in plotting much of the 1,600 kilometers of theEcuador-Peru border.

The U.S. aerial maps, released in February 1947, showed anerror in the technical descriptions used as the basis of the Rio Protocol inthe watered areas adjoining the Condor Mountain Range (Spanish: Cordillera del Condor). In particular, the CenepaRiver, situated between the Zamora and Santiago Rivers, was discovered tobe much more extensive than previously thought. As a result of the flaw, Ecuadorwanted to renegotiate the border along the 78-kilometer length of the CondorMountain Range, a proposal that was rejected by Peru. Furthermore, the U.S.maps showed two divortium aquariums, and not just one, between the Zamora and Santiago Rivers, as indicated inArticle VIII of the Rio Protocol, a discrepancy that eventually led theEcuadorian government to declare that the Protocol, being flawed, wasimpossible to implement.

Two years earlier, in July 1945, when the length of the Cenepa Riverwas yet undetermined and only one divortium aquarium was thought to exist inthe Condor, the question of the placement of the border in the Condor MountainRange was brought before Brazilian Naval Captain Braz Dias de Aguiar. The multinational guarantors of the RioProtocol had tasked Captain Dias de Aguiar, a technical expert, to mediate onthe disputes that should arise. In hisdecision, Captain Dias de Aguiar, declared that the Condor Mountain Range wasthe border; this decision was accepted by Ecuadorand Peru.

As a result of the discrepancies in the Rio Protocolrevealed by the U.S.aerial maps, the Ecuadorian government pulled out its representatives from theMixed Border Commission in September 1948, and withdrew altogether from theDemarcation Committee in 1953. Thedemarcation of the border then stopped, with all but 78 kilometers of the wholelength left unsettled. In September1960, Ecuadordeclared the Rio Protocol as null and void, stating that the Ecuadoriangovernment during the 1941 war, had been forced under duress to accede to theProtocol, as Peruvian forces were occupying Ecuadorian territory at that time.

Consequently, no major diplomatic initiatives were made toresolve the disputed border area. Forthe next several years, the heavily forested region was unexplored andunsettled, although a few indigenous tribes resided there. The area soon became militarized as Ecuador and Perusent troops to stake claims, setting up bunkers and outposts, with theEcuadorians positioned at the top and on the western slopes of the CondorMountain Range and Peruvians along the eastern slopes and adjacent Comaina Valley areas. Supplies to these army positions were sent byhelicopters, as the region practically did not have any roads.

January 6, 2024

January 6, 1921 – Turkish War of Independence : Greek forces attack the town of Eskişehir

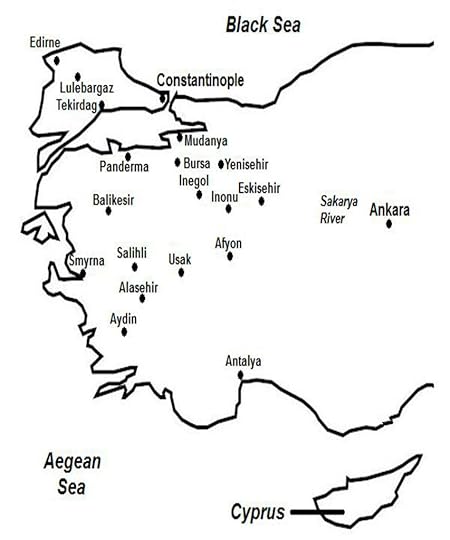

On January 6, 1921, the Greek Army attacked in the directionof the strategic town of Eskişehir,but was repulsed at the First Battle of Inonu. The battle was downplayed by the Greeks as a minor setback, but itconsiderably raised the morale of the Turks, who for the first time, had turnedback the enemy. Because of thisdevelopment, the Allied Powers (Britain,France, and Italy) met withrepresentatives of the Ottoman government and Turkish nationalists in London (known as theConference of London) in February-March 1921 in order to negotiate changes tothe Treaty of Sevres, which by this time was impossible to implement. However, the Turkish nationalists wereunyielding in their position that Turkey’s territorial integrity wasnon-negotiable and that the Allies must withdraw. As a result, the conference ended withoutreaching a settlement.

In early March 1921, with the arrival of reinforcements, theGreeks attacked again, but were defeated at the Second Battle of Inonu, andforced to return to Bursa. The Greeks’ southern advance captured Afyon,but a Turkish attempt to cut the railway line between Afyon and Usak forced theGreeks to meet and contain the threat, and then withdraw to Usak.

The Western Front in the Turkish War of Independence.

The Western Front in the Turkish War of Independence.(Taken from Turkish War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Western Front Greece had entered World War I on the side ofthe Allies because of Britain’spromise to reward Greecewith a large territorial concession of Ottoman Anatolia at the end of thewar. Greeceparticularly was interested in the Ottoman territories that contained a largeethnic Greek population, notably Smyrna, whichhad a sizable to perhaps even a majority Greek population and was the Greeks’cultural and economic center in Anatolia, and Eastern Thrace, as well as theislands of Imbros and Tenedos on the Aegean Sea.

As the Ottoman government had repressed ethnic Greeks inAnatolia during the war, the Allied Powers invoked a stipulation in theArmistice of Mudros to allow Greek forces to occupy Smyrna. The presumption was that despite the Ottoman capitulation, ethnic Greekscontinued to be threatened by the Ottomans with massacres and dispossession ofproperties, which were reported to have taken place extensively during the war.

A post-war complication arose since Britain, France,and Italy previously hadsigned a treaty (Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne of April 1917), whereby Smyrna and western Anatoliawere to be allocated to the Italians. Atthe Paris Peace Conference held after the war, both the Italian and Greekdelegations lobbied hard for Smyrna; in the end,the other Allied powers (led by Britain)voted in favor of Greece.

Then in the Treaty of Sevres of 1920, Italy was granted southern Anatolia centered in Antalya, while Greecewas given western Anatolia around Smyrna (aswell as most of Eastern Thrace). The Italians, however, felt that they hadreceived the short end of the deal without Smyrna, a resentment that would influence theoutcome of the western front.

On May 16, 1919, with Allied approval, 20,000 Greek soldierslanded in Smyrna,where they were greeted as liberators by a large crowd of ethnic Greeks. A commotion broke out when a Turkish gunmanfired at the Greek Army, killing one soldier. The Greek Army then opened fire, triggering a spate of violence acrossthe city. When order later was restored,some 300 Turkish and 100 Greek civilians had been killed; many incidents oflootings, beatings, rapes, and other crimes also took place.

War Of the Alliedoccupations, the Greek entry in Smyrnagreatly provoked the Turks. As a result,many Turkish guerilla groups formed, while it was at this time that Kemal beganorganizing his revolutionary nationalist government. The western front (more commonly known as theGreco-Turkish War of 1919-1922) began in earnest in mid-1920 (eleven months afterthe initial Greek landing) as a result of Britain’s attempt to implement thenewly released Treaty of Sevres. Thetreaty was presented to and signed by the Ottoman government, but was notratified; Ottoman authorities insisted that the treaty must be concurred to alsoby Kemal, who clearly would not agree to it. In fact, Kemal’s nationalist forces, by this time, were fighting theFrench in the southern front and were preparing a major offensive against theArmenians in the eastern front.

Furthermore, by the time of the Treaty of Sevres, divisionscaused by competing interests had developed among the Allies: France resented Britain’sdomineering position; Italywanted to curb British and French domination and Greek expansionism; and theFrench-Armenian alliance was faltering.

January 3, 2024

January 3, 1949 –Arab-Israeli War: Israeli forces trap Egyptian units in Gaza

On January 3, 1949, the Israeli Army surrounded the Egyptianforces inside the Gaza Strip in southwestern Palestine during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Three days later, Egypt agreed to a ceasefire whichsoon came into effect, ending the war. In the following months, Israelsigned separate armistices with Egypt,Lebanon, Jordan and Syria.

At war’s end, Israelheld 78% of Palestine,22% more than was allotted to the Jews in the original UN partition plan. Israel’sterritories comprised the whole Galilee and JezreelValley in the north, the whole Negevin the south, the coastal plains, and West Jerusalem. Jordanacquired the West Bank, while Egyptgained the Gaza Strip. No PalestinianArab state was formed.

During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and the 1947-1948 CivilWar in Palestine (previous article) thatpreceded it, over 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fled from their homes, with most ofthem eventually settling in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and southern Lebanon (Map11). About 10,000 Palestinian Jews alsowere displaced by the conflict. Furthermore, as a consequence of these wars, tens of thousands of Jewsleft or were forced to leave from many Arab countries. Most of these Jewish refugees settled in Israel.

1948 Arab-Israeli War. Key battle areas are shown. The Arab countries of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, assisted by volunteer fighters from other Arab states, invaded newly formed Israel that had occupied a sizable portion of Palestine.

1948 Arab-Israeli War. Key battle areas are shown. The Arab countries of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, assisted by volunteer fighters from other Arab states, invaded newly formed Israel that had occupied a sizable portion of Palestine.(Taken from 1948 Arab-Israeli War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

On May 14, 1948, the Palestinian Jews established the Stateof Israel. The next day, the infantnation was attacked by the armies of Egypt,Jordan, Syria, Lebanon,and Iraq,assisted by volunteer fighters from other Arab states. The Arabs’ stated reasons for the invasionwere to stop the violence and to restore law and order in Palestine, and to allow the Palestinianpeople to form a government of their choice. Also cited by the Arabs was the displacement of Palestinian Arabs causedby Jewish aggression. As the nation of Israel was by now in existence, theresulting 1948 Arab-Israeli War was one fought by sovereign states.

From the east, Jordanian and Iraqi forces crossed the JordanRiver into Palestine. The Jordanians advanced along two columns forJerusalem,which they surrounded on May 17, 1948. After heavy house-to-house fighting, the Jewish defenders of the citywere forced to surrender when they ran low on food and ammunition. The Jordanians captured Jerusalemand then occupied Latrun, a strategic outpost overlooking the highway that ledto Jerusalem.

Meanwhile, the Iraqis advanced to the vicinity surroundingthe Arab-populated city of Jenin, Nablus, and Tulkaran. On May 25, they captured Geulim, Kfar Vona,and Ein Vered before being stopped at Natanya, their ultimate objective on thewestern coast. Natanya’s fall would havedivided Israel’scoastal areas in two.

A strong Israeli counterattack on Jenin forced the Iraqis topull back and defend the city. TheIraqis repulsed the Israeli attack. Now,however, they were concerned with making further advances because of the riskof being cut off from the rear. TheIraqis, therefore, switched to a defensive position, which they maintained forthe rest of the war.

From the northeast, Syrian forces began their campaign byadvancing toward the south side of the Sea of Galilee. They captured some Israeli villages beforebeing defeated at Degania. The Syrianssoon withdrew across the border in order to regroup. On June 6, they launched another attack, thistime in northern Galilee, where they capturedMishmar Hayarden. Israeli Armyreinforcements soon arrived in northern Palestine,stopping further Syrian advances.

From the south, the Egyptian Army, which was the largestamong the invading forces, entered Palestinethrough the Sinai Desert. The Egyptians then advanced through southern Palestine on two fronts: one along the coastal road forTel-Aviv, and another through the central Negev for Jerusalem.

On June 11, 1948, the United Nations (UN) imposed a truce,which lasted for 28 days until July 8. AUN panel arrived in Palestineto work out a deal among the warring sides. The UN effort, however, failed to bring about a peace agreement.

By the end of the first weeks of the war, the Israeli Armyhad stopped the supposed Arab juggernaut that the Israelis had feared wouldsimply roll in and annihilate their fledging nation. Although the fighting essentially had endedin a stalemate, Israeli morale was bolstered considerably, as many Israelivillages had been saved by sheer determination alone. Local militias had thrown back entire Arabregular army units.

Earlier on May 26, Israeli authorities had merged thevarious small militias and a large Jewish paramilitary into a single IsraeliDefense Force, the country’s regular armed forces. Mandatory conscription into the militaryservice was imposed, enabling Israelto double the size of its forces from 30,000 to 60,000 soldiers. Despite the UN arms embargo, the Israeligovernment was able to purchase large quantities of weapons and militaryequipment, including heavy firearms, artillery pieces, battle tanks, andwarplanes.

The Arabs were handicapped seriously by the UN armsrestriction, as the Western countries that supplied much of the Arabs’ weaponsadhered to the embargo. Consequently,Arab soldiers experienced ammunition shortages during the fighting, forcing theArab armies to switch from offensive to defensive positions. Furthermore, Arab reinforcements simply couldnot match in numbers, zeal, and determination the new Israeli conscriptsarriving at the front lines. And just asimportant, the war revealed the efficiency, preparedness, and motivation of theIsraeli Army in stark contrast to the inefficiency, disunity, and inexperienceof the Arab forces.

During the truce, the UN offered a new partition plan, whichwas rejected by the warring sides. Fighting restarted on July 8, one day before the end of the truce. On July 9, Israeli Army units in the centerlaunched an offensive aimed at opening a corridor from Tel-Aviv to eastern Palestine, in order to lift the siege on Jerusalem. The Israelis captured Lydda and Ramle, two Arab strongholds nearTel-Aviv, forcing thousands of Arab civilians to flee from their homes toescape the fighting. The Israelis reachedLatrun, just outside Jerusalem,where they failed to break the solid Jordanian defenses, despite makingrepeated assaults using battle tanks and heavy armored vehicles. The Israelis also failed to break into theOld City of Jerusalem, and eventually were forced to withdraw.

On July 16, however, a powerful Israeli offensive innorthern Palestine captured Nazarethand the whole region of lower Galilee extending from Haifain the coastal west to the Sea of Galilee inthe east. Further north, the Syrian Armycontinued to hold Mishmar Hayarden after stopping an Israeli attempt to takethe town.

In southern Palestine,the Egyptian offensives in Negba (July 12), Gal (July 14), and Be-erot Yitzhakwere thrown back by the Israeli Army, with disproportionately high Egyptiancasualties. On July 18, the UN imposed asecond truce, this time of no specified duration.

The truce lasted nearly three months, when on October 15,fighting broke out once more. During thetruce, relative calm prevailed in Palestinedespite high tensions and the occasional outbreaks of small-scalefighting. The UN also proposed newchanges to the partition plan which, however, were rejected once more by thewarring sides.

December 31, 2023

December 31, 1948 – Indian-Pakistani War of 1948: India and Pakistan agree to a UN-mandated ceasefire

The United Nations (UN) released twopreviously approved resolutions for a ceasefire and the future of Kashmir,which were accepted by Indiaand Pakistan. The war officially ended on December 31,1948.

On January 5, 1949, the UN approvedthe following:

1. Pakistanmust withdraw its forces from Kashmir;

2. Indiamust also withdraw its forces from Kashmir,but leave a small police contingent to maintain local peace and order;

3. After these two stipulations aremet, Kashmiris will hold a plebiscite to decide the future of their land.

(Taken from Indian-Pakistani War of 1948 – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 2)

Background On August 15, 1947, the newstate of Kashmir (Map 1) found itselfgeographically located next to India and Pakistan, tworival countries that recently had gained their independences after thecataclysmic partition of the Indian subcontinent. Fearing the widespread violence that hadaccompanied the birth of Indiaand Pakistan, the Kashmirimonarch, who was a Hindu, chose to remain neutral and allow Kashmirto be nominally independent in order to avoid the same tragedy from befallinghis mixed constituency of Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs.

Pakistan exerted diplomatic pressure on Kashmir, however, as the Pakistanigovernment had significant strategic and economic interests in the former Princely State. Most Pakistanis also shared a common religion with the overwhelminglyMuslim Kashmiri population. India also nurtured ambitions on Kashmir andwanted to bring the former Princely State into its sphere ofinfluence. After Kashmir gained back itssovereignty, the British colonial troops departed; consequently, Kashmir was left only with a small native army to enforcepeace and order.

War On October 22, 1947, when rumorssurfaced that Kashmir would merge with India, Muslim Kashmiris in thestate’s western regions broke out in rebellion. The rebels soon were joined by Pakistani fighters who entered theKashmiri border from Pakistan. The rebels and Pakistanis seized the towns ofMuzzafarabad and Dommel (Map 1) where they disarmed the Kashmiri troops, whothereafter also joined the rebels.

Within a few days, the rebellion hadspread to Baramula and threatened Srinagar, Kashmir’s capital. The Kashmiri ruler fled to India, where he pleaded for militaryassistance with the Indian government. The Indians agreed on the condition that Kashmir be merged with India,to which the Kashmiri ruler gave his consent. Soon thereafter, Kashmir’s status as asovereign state ended. On October 27,1947, Indian forces arrived in Srinagar and expelled the rebels, whoby this time, had entered the capital.

Earlier, Indiaand Pakistan had jointlyagreed to a policy of non-intervention in Kashmir’sinternal affairs. But with theterritorial merger of Indiaand Kashmir, Indian forces gained the legal authority to occupy the former Princely State. The Pakistani government now ordered its forces to invade Kashmir. ThePakistan Armed Forces chief of staff, however, who was also a British Armyofficer, refused to comply, since doing so would pit him against LordMountbatten, the British Governor General of India, who had ordered the Indiantroops to Kashmir. With the Pakistanimilitary leadership in a crisis and its army placed on hold, the Indian Armyvirtually deployed unopposed in Kashmir andsecured much of the state.

In early November 1947, the GilgitScouts, a civilian paramilitary based in the Gilgit region in northern Kashmir, broke out in rebellion over some disagreement withthe Kashmiri government. The GilgitScouts soon were joined by tribal militias from Chitral in northern Pakistan. Together, they wrested control of the wholenorthern Kashmir.

By mid-November 1947, the IndianArmy’s counter-attacks in the west had recaptured Uri and Baramula and hadpushed back the coalition of Kashmir rebelsand Pakistani fighters toward the Pakistani border. Further Indian advances were stalled by theonset of winter, however, as the Indian troops were not prepared for fightingin the cold, high altitudes and were encountering logistical problems.

With the Indian forces settling downto a defensive position, the rebel coalition forces went on the attack andcaptured the towns of Kotli and Mirpur in the south, thereby extending the battlelines on the west to a nearly north to south axis. In southwest Kashmir, the Indians took Chamb,and fortified the key city of Jammu,which remained in their possession throughout the war.

India and Pakistan. Diagram shows India and the two “wings” of Pakistan (West Pakistan and East Pakistan) on either side. Kashmir, the battleground during the Indian-Pakistani War of 1947, is located in the northern central section of the Indian subcontinent

With the arrival of spring weather inMay 1948, the Indians launched a number of offensive operations in the west andretook the towns of Tithwail, Keran, and Gurais. In the north, a daring Indian attack usingbattle tanks at high altitudes captured Ziji-La Passand Dras. But later that year, thearrival of Pakistan Army units in rebel-held Kashmirin the west stopped further significant Indian advances.

PakistanArmy units also were deployed in Kashmir’s HighHimalayas to augment the Gilgit-Chitral rebel coalition forces. Together, they advanced south and capturedSkardu and Kargil, and threatened Leh. Acounter-attack by the Indian Army in May 1948, however, stopped the PakistanArmy-led forces, which were pushed back north of Kargil.

September 14, 2023

September 14, 1960 – Congo Crisis: Mobutu Sese Seko launches a military coup

On September 14, 1960 Mobutu Sese Seko, head of the armedforces, seized power in the Republic of the Congo(present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) in the midst of theCongo Crisis. The crisis consisted of a series of civil wars that began shortlyafter the country gained its independence from Belgium on June 30, 1960. Mobutulaunched the coup following the impasse between President Patrice Lumumba andPresident Joseph Kasa-Vubu after Lumumba had sought Soviet support to quell aBelgian-supported uprising in Katangaand South Kasai.

After the coup, Mobutu remained as head of the Congomilitary until November 1965, when he seized power in another coup followinganother impasse in the government. He would hold power in a totalitariangovernment for the next 32 years.

In his long reign, he grossly mismanaged the country, whichhe renamed Zaire. Government corruption was widespread, thecountry’s infrastructure was crumbling, and poverty and unemployment wererampant. And while Zaire’s economy stagnated under ahuge foreign debt, President Mobutu amassed a personal fortune of severalbillions of dollars.

In 1997, he was deposed in the First Congo War.

(Taken from First Congo War – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 1)

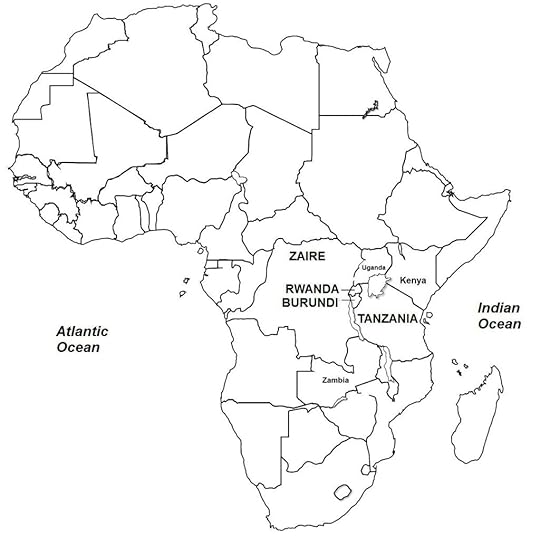

Background of theFirst Congo War In themid-1990s, ethnic tensions rose in Zaire’s eastern regions. Zairian indigenous tribes long despised theTutsis, another ethnic tribe, whom they regarded as foreigners, i.e. theybelieved that Tutsis were not native to the Congo. The Congolese Tutsis were called Banyamulengeand had migrated to the Congoduring the pre-colonial and Belgian colonial periods. Over time, the Banyamulenge established somedegree of political and economic standing in the Congo’s eastern regions. Nevertheless, Zairian indigenous groupsoccasionally attacked Banyamulenge villages, as well as those of othernon-Congolese Tutsis who had migrated more recently to the Congo.

During the second half of the twentieth century, the Congo’s eastern region was greatly destabilizedwhen large numbers of refugees migrated there to escape the ethnic violence in Rwanda and Burundi. The greatest influx occurred during theRwandan Civil War, where some 1.5 million Hutu refugees entered the Congo’sKivu Provinces (Map 17). The Huturefugees established giant settlement camps which soon came under the controlof the deposed Hutu regime in Rwanda,the same government that had carried out the genocide against RwandanTutsis. Under cover of the camps, Hutuleaders organized a militia composed of former army soldiers and civilianparamilitaries. This Hutu militiacarried out attacks against Rwandan Tutsis in the camps, as well as against theBanyamulenge, i.e. Congolese Tutsis. TheHutu leaders wanted to regain power in Rwandaand therefore ordered their militia to conduct cross-border raids from theZairian camps into Rwanda.

To counter the Hutu threat, the Rwandan government forged amilitary alliance with the Banyamulenge, and organized a militia composed ofCongolese Tutsis. The Rwandangovernment-Banyamulenge alliance solidified in 1995 when the Zairian governmentpassed a law that rescinded the Congolese citizenship of the Banyamulenge, andordered all non-Congolese citizens to leave the country.

War In October1996, the provincial government of South Kivu in Zaire ordered all Bayamulenge toleave the province. In response, theBanyamulenge rose up in rebellion. Zairian forces stepped in, only to be confronted by the Banyamulengemilitia as well as Rwandan Army units that began an artillery bombardment of South Kivu from across the border.

A low-intensity rebellion against the Congolese governmenthad already existed for three decades in Zaire. Led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, the Congorebels opposed Zairian president Mobutu Sese Seko’s despotic, repressiveregime. President Mobutu had seizedpower through a military coup in 1965 and had in his long reign, grosslymismanaged the country. Governmentcorruption was widespread, the country’s infrastructure was crumbling, andpoverty and unemployment were rampant. And while Zaire’seconomy stagnated under a huge foreign debt, President Mobutu amassed a personalfortune of several billions of dollars.

Kabila joined his forces with the Banyamulenge militia;together, they united with other anti-Mobutu rebel groups in the Kivu, with thecollective aim of overthrowing the Zairian dictator. Kabila soon became the leader of this rebelcoalition. In December 1996, with thesupport of Rwanda and Uganda,Kabila’s rebel forces won control of the border areas of the Kivu. There, Kabila formed a quasi-government thatwas allied to Rwanda and Uganda.

The Rwandan Army entered the conquered areas in the Kivu anddismantled the Hutu refugee camps in order to stop the Hutu militia fromcarrying out raids into Rwanda. With their camps destroyed, one batch of Huturefugees, comprising several hundreds of thousands of civilians, was forced tohead back to Rwanda.

Another batch, also composed of several hundreds ofthousands of Hutus, fled westward and deeper into Zaire, where many perished fromdiseases, starvation, and nature’s elements, as well as from attacks by theRwandan Army.

When the fighting ended, some areas of Zaire’s eastern provinces virtuallyhad seceded, as the Zairian government was incapable of mounting a strongmilitary campaign into such a remote region. In fact, because of the decrepit condition of the Zairian Armed Forces,President Mobutu held only nominal control over the country.

The Zairian soldiers were poorly paid and regularly stoleand sold military supplies. Poordiscipline and demoralization afflicted the ranks, while corruption was rampantamong top military officers. Zaire’smilitary equipment often was non-operational because of funding shortages. More critically, President Mobutu had becomethe enemy of Rwanda and Angola,as he provided support for the rebel groups fighting the governments in thosecountries. Other African countries thatalso opposed Mobutu were Eritrea,Ethiopia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

In December 1996, Angolaentered the war on the side of the rebels after signing a secret agreement withRwanda and Uganda. The Angolan government then sent thousands ofethnic Congolese soldiers called “Katangese Gendarmes” to the KivuProvinces. These Congolese soldiers werethe descendants of the original Katangese Gendarmes who had fled to Angola in the early 1960s after the failedsecession of the Katanga Province from the Congo.

The presence of the Katangese Gendarmes greatly strengthenedthe rebellion: from Goma and Bukavu (Map 17), the Gendarmes advanced west andsouth to capture Katanga andcentral Zaire. On March 15, 1977, Kisanganifell to the rebels, opening the road to Kinshasa, Zaire’scapital. Kalemie and Kamina in Katanga Provincewere captured, followed by Lubumbashiin April. Later that month, the AngolanArmy invaded Zairefrom the south, quickly taking Tshikapa, Kikwit, and Kenge.

Kabila also joined the fighting. Backed by units of the Rwandan and UgandanArmed Forces, his rebel coalition force advanced steadily across central Zaire for Kinshasa. Kabila met only light resistance, as theZairian Army collapsed, with desertions and defections widespread in itsranks. Crowds of people in the towns andvillages welcomed Kabila and the foreign armies as liberators.

Many attempts were made by foreign mediators (United Nations, United States, and South Africa)to broker a peace settlement, the last occurring on May 16, 1977 when Kabila’sforces had reached the vicinity of Kinshasa. The Zairian government collapsed, withPresident Mobutu fleeing the country. Kabila entered Kinshasaand formed a new government, and named himself president. The First Congo War was over; the secondphase of the conflict broke out just 15 months later (next article).

May 9, 2023

May 9, 1936 – Italy annexes Ethiopia

Benito Mussolini, whose quest for Italiancolonial expansion was only restrained by the reactions from both the Britishand French, saw the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as British betrayal to theStresa Front. To Mussolini, it was agreen light for him to launch his long desired conquest of Ethiopia[1] (thenalso known as Abyssinia). In October 1935, Italyinvaded Ethiopia, overrunningthe country by May 1936 and incorporating it into newly formed Italian East Africa. In November 1935, the League of Nations,acting on a motion by Britainthat was reluctantly supported by France,imposed economic sanctions on Italy,which angered Mussolini, worsening Italy’srelations with its Stresa Front partners, especially Britain. At the same time, since Hitler gave hissupport to Italy’s invasionof Ethiopia, Mussolini wasdrawn to the side of Germany. In December 1937, Mussolini ended Italy’s membership in the League of Nations, citing the sanctions, despite the League’s alreadylifting the sanctions in July 1936.

(Taken from Events leading up to World War II in Europe – Wars of the 20th Century –Vol. 6)

In January 1936, Mussolini informed theGerman government that he would not oppose Germanyextending its sphere of influence in Austria (Germany annexed Austria inMarch 1938). And in February 1936,Mussolini assured Hitler that Italywould not invoke the Versailles and Locarno treaties if Germanyremilitarized the Rhineland. In March 1936, Hitler did just that,eliciting no hostile response from Britainor France. Then in the Spanish Civil War, whichstarted in July 1936, Italyand Germanyprovided weapons and troops to the right-wing Nationalist forces that rebelledagainst the Soviet Union-backed leftist Republican government. In April 1939, the Nationalists emergedvictorious, and their leader General Francisco Franco formed a fascistdictatorship in Spain.

In October 1936, Italy and Germanysigned a political agreement, and Mussolini announced that “all other Europeancountries would from then on rotate on the Rome-Berlin Axis”, with the term“Axis” later denoting this alliance, which included Japan as well as other minorpowers. In May 1939, German-Italianrelations solidified into a formal military alliance, the “Pact of Steel”. In November 1937, Italy joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which Germany and Japansigned one year earlier (November 1936), ostensibly only directed against theCommunist International (Comintern), but really targeting communist ideologyand by extension, the Soviet Union. In September 1940, the Axis Powers wereformed, with Germany, Italy, and Japan signing the Tripartite Pact.

In April 1939, Italy invaded Albania(separate article), gaining fullcontrol within a few days, and the country was joined politically with Italyas a separate kingdom in personal union with the Italian crown. Six months later (September 1939), World WarII broke out in Europe, which took Italy completely by surprise.

Despite its status as a major militarypower, Italywas unprepared for war. It had apredominantly agricultural economy, and industrial production forwar-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for war-importantitems such as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind those ofother western powers. In militarycapability, Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostlyobsolete, although the Italian Navy was large, ably powerful, and possessedseveral modern battleships. Cognizant ofItalian military deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts to build up armedstrength, and by 1939, some 40% of the national budget was allocated tonational defense. Even so, Italianmilitary planners had projected that full re-armament and building up of theirforces would be completed only in 1943; thus, the unexpected start of World WarII in September 1939 came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

[1] Also encouraging Mussolini to invade was the recently signedItalian-French agreement (January 1935), where France,hoping to keep Italy fromsiding with Germany, cededto Italy some colonial areasin Africa, and promised not to interfere if Italyinvaded Ethiopia.

March 11, 2023

March 11, 1969 – Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Demonstrators in Beijing besiege the Soviet Embassy in protest for the attack on the Chinese Embassy in Moscow

Fighting broke out between Soviet and Chinese units on onDamansky/Zhenbao Island on March 2, 1969. Following this incident, sensationalist news reports by the mediastirred up the general population in both countries. On March 3, 1969 in Beijing, large protests were held outside theSoviet Embassy, and Soviet diplomatic personnel were harassed. In the Soviet Union, demonstrations were heldin Khabarovsk and Vladivostok. In Moscow,angry crowds hurled stones, ink bottles, and paint at the Chinese Embassy.

On March 11, 1969 in Beijing,demonstrators besieged the Soviet Embassy in protest for the attack on theChinese Embassy. Then when Soviet mediareported that captured Russian soldiers during the Damansky/Zhenbao incidenthad been tortured and executed, and their bodies mutilated, largedemonstrations consisting of 100,000 people broke out in Moscow. Other mass assemblies also occurred in other Russian cities.

On March 15, 1969, a second (and larger) clash broke out inDamansky/Zhenbao Island, where both sides sent a force of regimental strength,or some 2,000-3,000 troops. The Chineseclaimed that the Soviets fielded one motorized infantry battalion, one tankbattalion, and four heavy-artillery battalions, or a total of over 50 tanks andarmored vehicles, and scores of artillery pieces. The two sides again claimed victory in the10-hour battle, and also accused the other side of firing the first shots. Both sides suffered heavy casualties.

(Taken from Sino-Soviet Border Conflict – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia: Vol. 5)

Background Historically,the communist parties of Russiaand Chinahad not had close ties, and were even hostile to each other. During the early years of the ChineseCommunist Party, in 1923, the Soviet government under Vladimir Lenin encouragedthe Chinese communists to join the non-communist Kuomintang (ChineseNationalists). Then in World War II,Stalin urged Mao to form an alliance with Chiang Kai-shek to fight theJapanese. In the 1930s, Mao began toview traditional Marxism, like that applied in the Soviet Union, as relevantonly in the industrialized countries, and not consistent with China’s agricultural society. Mao soon developed a new branch of Marxismcalled Maoism, which stated that in agricultural societies, the revolutionarystruggle should be led by the peasants.

In September 1963-July 1964, Mao published a series ofpapers condemning Khrushchev and Soviet policies. In October 1964, Leonid Brezhnev succeeded asthe new leader of the Soviet Union, and overturnedsome of the liberal reforms of his predecessor, although he generally continuedto implement party policies. Brezhnevadopted a hard-line stance on the West, which did not lead to improvedSino-Soviet relations. Instead, tiesbetween the two communist countries continued to decline. By 1963, the Sino-Soviet split involved thelong-standing territorial dispute along the two countries’ poorly defined4,380-kilometer shared border. In July1964, Mao stated that the territory of the Soviet Union was excessive, and thatSoviet regions of Lake Baikal, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, and Kamchatka formerly belonged to China. Mao then said that Chinahad “not yet presented our bill for this list” to the Soviet Union.

Chinathen declared that two 19th century treaties with the Soviet Union, the Treatyof Aigun (1858) and the Convention of Peking (1860), were “unequal treaties”,in that the then ruling powerful Russian Empire had forced the war-weakenedChinese Qing Dynasty to cede one million square kilometers of territory inManchuria and Siberia to Russia. Mao’s government also stated that throughother “unequal treaties” which the Qing court was forced to sign in the 19thcentury, China lost some 500,000 square kilometers of land in its westernborder, lands which now are part of the Soviet Union.

The Chinese government soon made the clarification that bybringing up the matter of “unequal treaties” with the Soviet Union, China didnot seek to reclaim these territories, but that it wanted the Soviet Union to acknowledgethat the treaties indeed were unjust, and that the two sides must negotiate afinal border agreement on the basis of present-day boundaries. In this respect, for China, the disputed territoryamounted to only 35,000 square kilometers along the common border. And of this figure, 34,000 square kilometerswere located in the western side bordering the SovietSocialist Republicsof Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Another 1,000 square kilometers were locatedalong the eastern side running along the length of three rivers: the Argun,Amur, and Ussuri (Figure 20).

Both the Treaty of Aigun and the Convention of Peking, whichcodified the border along the eastern side, stipulated that the Sino-Russianborder was located on the Chinese side running the whole length of the threerivers, thus giving the Russians full sovereignty along these rivers, includingthe many hundreds of islands located therein. Chinawanted to negotiate a readjustment of this river border, and proposed that thenew border line be placed at the midpoint of the rivers. The Soviet Unionrejected any readjustments, stating that the existing treaties had alreadyfixed the border.

Furthermore, the Soviet Uniondenied that the 19th century treaties were “unequal treaties”, and countered bystating that the Chinese rulers themselves were territorially ambitious at thattime. The Soviets also stated that inrecently signed land treaties between Chinaand the Soviet Union, Mao’s government had notbrought up the matter of the earlier “unequal treaties” in these areas, andthus constituted a tacit acknowledgment of Soviet sovereignty of theseareas. In February 1964, the two sidesheld border talks, which collapsed later that year when Mao raised newcriticisms against the Soviet government.

Both sides now increased their forces at the border, raisingtensions. The Soviet government alsostrengthened its relations with Mongolia(a socialist client state of the Soviet Union). In January 1966, the two countries signed amilitary alliance that allowed Soviet troops to deploy in Mongolia to help defend the countryagainst a possible Chinese attack.

In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, where hepurged his political rivals and took full control of the Chinese CommunistParty. But the Cultural Revolutionbrought widespread turmoil in China,and also exacerbated the ideological clash between Chinaand the Soviet Union, increasing tensionsbetween them.

In August 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, and overthrew thesocialist government there that had tried to implement liberal reforms. Mao saw this aggression as one which theSoviets could potentially undertake against China. By the mid-1960s, the Soviet-Chinese borderwas heavily militarized, and hundreds of skirmishes took place, which increasedin frequency in 1968 in the highly volatile eastern border region. Soviet soldiers used physical force to removeChinese fishermen and worker groups, as well as Chinese military patrols, whichhad entered the river islands. InJanuary 1968, China filed adiplomatic protest when Soviet troops attacked and killed Chinese workers in Qiliqin Island.

January 26, 2023

January 26, 1939 – Spanish Civil War: Nationalist forces capture Barcelona

By the third week of January 1939, the Nationalistshad reached the outskirts west and south of Barcelona. The Republican government, led by President Manuel Azaña and Prime Minister Negrin, evacuated from thecapital and fled north to the Spanish-French border. Some 500,000 Republican soldiers andcivilians joined the retreat, pursued by the Nationalist Army. Prime Minister Negrin appealed to GeneralFranco for peace talks, but was rejected, as the Nationalist leader wanted onlyunconditional surrender. On January 26, Barcelona fell to theNationalists.

(Taken from Spanish Civil War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 3)

Background In the municipal elections of April 1931, ananti-monarchical political coalition of leftist republicans and socialists cameto power and formed a republican government (called the Spanish Second Republic**). The military regime ended and King AlfonsoXIII was forced to step down and leave for exile abroad. Thus, the Spanish monarchy ended.

The now ruling political left blamed the Church andthe monarchy for Spain’smany ills, including the socio-economic inequalities, loss of the empire’s vastterritories, and backwardness compared to other more industrialized Europeancountries.

Then in general elections held in June 1931, leftistrepublicans and socialists again won a majority, this time for parliament, andthereafter convened the Cortes Generales(Spanishlegislature). The new government, wantingto secularize the state, passed a new constitution in December 1931, whichremoved the Catholic Church’s pre-eminence over the country’s social andeducational institutions. The newconstitution promoted civil liberties and guaranteed free speech and the rightto assembly, as well as universal suffrage, where women, for the first time,were allowed to vote.

The constitution also nationalized industries andbegan an agrarian reform program. Theright to regional self-determination was upheld; as a result, the regions ofBasque and Catalonia, both hotbeds ofseparatism, gained political autonomy. The libertarian atmosphere generated by the new regime encouragedviolent anti-clericalism: starting in May 1931, many churches, monasteries, convents, and other religious buildings in Madrid and across Spain were burned down, destroyed,or vandalized.

Spain’s traditional political elite, whichconstituted and defended the interests of the upper classes and the CatholicChurch, looked on with great alarm, as the changes threatened to destroy longvenerated Spanish institutions. In thecountryside, tensions rose between peasants and landowners, destabilizing thequasi-feudalistic agrarian system of the latifundia,i.e. the vast agricultural plantations owned by the small upper class. In August 1932, army officers, led by GeneralJose Sanjurjo, carried out an unsuccessful uprising because of his oppositionto the government’s reforms in the military establishment.

Concerned by the rising instability, the governmentslowed down the peace of reforms, which then drew the indignation of laborunions and peasant sector. The economicdevastation caused by the ongoing Great Depression also eroded popular supportfor the regime. In general electionsheld in November 1933, centrist and right-wing political parties emergedvictorious. A center-right governmentwas formed, which reversed or stalled the previous regime’s reforms. Then in October 1934 when the right-wingparty CEDA (or Confederación Española de DerechasAutónomas) putpressure on the center-led coalition government that saw the appointment ofCEDA into Cabinet positions, the Unión Generalde Trabajadores, apowerful workers’ union associated with the socialist party, launched anationwide general strike. The strikesfailed in most areas.

However, the strikes were successful (initially) in Catalonia, and more spectacularly carried out in Asturias. In the latter, in the event known as theAsturias miners’ strike of 1934, thousands of miners took over many towns andvillages, including Oviero, the provincial capital,where the Catholic cathedral and government buildings were burned down, andlocal officials and clergy were executed. Units of the Spanish Army were called in, led by two commanders one of whomwas General Francisco Franco. Aftertwo weeks of fighting, the revolt was crushed and thousands of workers wereexecuted or imprisoned.

Consequently, military officers who were thought tobe supportive of the government (i.e. right-wing) were promoted, includingGeneral Franco, who became commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Politically and socially, the country hadbecome polarized into two opposite, mutually hostile forces: the left and theright. The left targeted rightistsectors: the church with executions and arson, employers with militant actions,and agricultural landowners with seizure of farmlands. In turn, the political right killed andjailed union leaders and left-leaning intellectuals and academics.

At this time, thousands of youths from right-wingand monarchist organizations joined the FalangeEspañola de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista or simply Falange, a fascist party influencedby founding movements in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Many leftists also began to embrace moreradical and violent ideas, including armed revolution.

In general elections held in February 1936, thePopular Front, a coalition of leftist republicans, socialists, and communists,emerged victorious, only edging out the combined right-wing and centrist votesbut gaining a clear majority in parliament. The leftist victory came about in large part because of the electoralparticipation of the anarchists who, represented by the anarchist labor union Confederación Nacional delTrabajo or CNT, were infuriated by theright-wing government’s anti-anarchist policies. With the leftist electoral victory, a wave oflawlessness took place, as leftist elements forced the release of jailedpolitical prisoners (without judicial proceedings) and peasants seizedfarmlands.

A leftist government was formed, which demoted orre-assigned military officers who were deemed to be right-wing; among theseofficers was General Franco, who was dismissed as commander-in-chief andtransferred to the distant Canary Islands. Also affected by the restructuring wasGeneral Emilio Mola, who was transferred tothe northern province of Navarre, a monarchist stronghold,from where he began to conspire with other officers in a plot to overthrow thegovernment. The motivation for the plotwas the perceived need to save the country from self-destruction and/orcommunism. By early July, many militarycommands in Spainwere ready to carry out the coup; General Franco wavered for some time beforealso opting in.

In the plan, Spain’s forces in Spanish Morocco would launch a revolt on July 17, to befollowed by the Spanish Army in the mainland the next day. Then on July 18, Spanish Moroccan Army would arrive in mainland Spain and together with thepeninsular forces, would overthrow the government.

In Madridon July 12, 1936, an Assault Guard police officer, who also belonged to theSocialist Party, was shot and killed by Falangists. The next day, Assault Guards arrested andkilled Jose Calvo Sotelo, a monarchist politicianand the leading right-wing parliamentarian. Retaliatory killings followed these two incidents. Sotelo’s murder served as the tipping pointfor the military officers to launch the coup.

War On July 17, 1936, Spain’sforces in Spanish Morocco declared in a radio broadcast a state of war againstthe central government in Madrid,an act of rebellion that opened the Spanish Civil War. These overseas forces, called the “Army ofAfrica”, were the Spanish Army’s strongest fightingunits and consisted of the Spanish Legion and Moroccan regiments. The Army of Africa would contributesignificantly to the outcome of the land operations in the coming war.

Earlier, local authorities in Spanish Morocco hadlearned of the plot. As a result, therebels were forced to move forward the uprising from the previously plannedschedule of 5 AM on July 18. Shortlyafter the rebellion was broadcast, the Army of Africa gained control of SpanishMorocco, in the process also killing dozens of persons, includingpro-government army officers and civilian leaders.

** The First Spanish Republicexisted between February 1873 to December 1874 after the Spanish monarch, KingAmadeo I, abdicated; the republic ended with the proclamation of King AlfonsoXII.

January 24, 2023

January 24, 1986 – Ugandan Bush War: Rebel forces capture Kampala

On January 22, 1986, rebel forces of the National ResistanceArmy (NRA), led by Yoweri Museveni, laid siege to Kampala, capturing theUgandan capital three days later. Thegovernment collapsed, with its leaders fleeing into exile abroad. Thousands of Kampala residents took to the streets andwarmly received Museveni and the NRA fighters. On January 23, 1986, Museveni took over power and declared himselfpresident of Uganda. The Ugandan Bush War was over; between300,000 and 500,000 persons had lost their lives.

(Taken from Ugandan Bush War – Wars of the 20th Century – Vol. 3)

Background OnApril 11, 1979, General Idi Amin was removed from power when the TanzanianArmy, supported by Ugandan rebels, invaded and took over Uganda (previous article). Uganda then entered a transitionalperiod aimed at a return to democracy, a process that generated great politicalinstability. A succession of leadersheld power only briefly because of tensions between the civilian government andthe newly reorganized Ugandan military leadership. Furthermore, ethnic-based political partieswrangled with each other, hoping to gain and play a bigger role in the futuregovernment.

In general elections held in December 1980, former PresidentMilton Obote, who had been the country’s head of state before being deposed ina coup by General Amin in 1971, returned to power by winning the presidentialrace. It was hoped that the electionswould advance the country’s transition to democracy. Instead, they served as the trigger for thecivil war that followed. Defeatedpolitical groups accused President Obote of cheating to win the elections. Tensions rose within the already chargedpolitical atmosphere. Many armed groupsthat already existed during the war now rose up in rebellion against thegovernment.

War The UgandanCivil War is historically cited as having started on February 6, 1981, when oneof the armed groups attacked a Ugandan military facility. The various rebelmilitias were tribe-based, operated independently of each other, and generallycarried out their activities only within their local and regionalstrongholds. One such rebel militiaconsisted of former Ugandan Army soldiers still loyal to General Amin, andfought out of the West Nile District, which was General Amin’s homeland. The various rebel militias had limited capabilityto confront government forces and therefore employed hit-and-run tactics, suchas ambushing army patrols, raiding armories and seizing weapons, and carryingout sabotage operations against government installations.

The rebel group that ultimately prevailed in the war was theNational Resistance Army (NRA), led by Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’sformer Defense Minister. As a universitystudent, Museveni had received training in guerilla warfare, which he wouldlater put to use in the war.

In response, the Ugandan Army launched an extensivecounter-insurgency campaign in the countryside. The soldiers particularly targeted the rural population, which theybelieved was supporting the rebels. Themany atrocities committed by soldiers included summary executions, tortures,rapes, lootings, and destruction of homes and properties. The West Nile District was hard hit becauseof its fierce opposition to President Obote. Furthermore, soldiers from other ethnic groups were repressed during thereign of General Amin. Thus, after thedictator’s overthrow, these ethnic groups, particularly the Acholi and Langowhich formed the majority in the Ugandan Army, carried out revenge by targetingcivilians in the West Nile District.

The insurgency spread throughout most of Uganda, but the greatest concentration of rebelactivity took place in the Luwero Triangle (Map 23), a rural region locatedjust north of Kampala,the country’s capital. Consequently, thegovernment’s counter-insurgency measures were most intense in the LuweroTriangle, which also received widespread international media attention. To cut off the insurgency’s source ofsupport, government forces depopulated villages and settlements in the LuweroTriangle and relocated the residents into guarded resettlement camps.

The military campaigns had a great impact on thecountryside, particularly in terms of human casualties. In the Luwero Triangle, tens of thousands ofcivilians were killed, while hundreds of thousands fled from the region. In the West Nile District, 30,000 personslost their lives, while 500,000 fled to neighboring Sudanand Zaire. As a result of the increasing violence, Britain and the United States ended their economic support to Uganda, which only worsened thealready dire conditions in that African country.

In December 1983, General David Oyite-Ojok, the UgandanArmed Forces chief of staff, died in a helicopter crash. General Oyite-Ojok was an Acholi. President Obote appointed a fellow Lango asthe new chief of staff. General BazilioOlara-Okello, an Acholi, was infuriated as he was the next in line to succeedGeneral Oyite-Ojok. Tensions rosebetween Acholis and Langos in the military, which led to skirmishes. In July 1985, General Olara-Okello and otherofficers, declaring their dissatisfaction with the government’s conduct of thewar, overthrew President Obote in a coup.

The coup leaders took over power and formed a “MilitaryCouncil” to run the country. Peace talkswere held with the various rebel groups, which soon led to an agreement thatestablished a power-sharing government that included rebel leaders who haddisarmed and disbanded their militias. However, Ugandacontinued to experience unrest and widespread violence, and the enmity betweenAcholi and Lango soldiers undermined the military’s ability to operateeffectively. Most crucially, thegovernment’s peace agreement with Museveni and the NRA, although signed by thetwo sides, was not implemented, and hostility and mistrust remained.

November 23, 2022

November 23, 1946 – First Indochina War: French forces bombard Haiphong

By September 1946, tensions had risen between French andViet Minh forces, which led to armed threats and provocations. The Viet Minh (“League for the Independenceof Vietnam”; Vietnamese: Việt Nam Độc LậpĐồng Minh Hội) was a merger of Vietnamese nationalist/independene movementsled by the Indochinese Communist Party which sought the end of French colonialrule. In November 1946, fighting broke out in Haiphong when French port authorities seizeda Chinese junk, but were in turn fired upon by the Viet Minh. The French first demanded that the Viet Minhyield control of Haiphong,and then bombarded the city using naval and ground artillery, and air strikes. The French gained control of Haiphong, expelling theViet Minh, with 6,000 civilians killed in the fighting.

Southeast Asia today.

Southeast Asia today.(Taken from First Indochina War – Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Background OnAugust 14, 1945, Japanannounced its acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, marking theend of the Asia-Pacific theatre of World War II (the European theater of WorldWar II had ended earlier, on May 8, 1945). The sudden Japanese capitulation left a power vacuum that was quicklyfilled by the Viet Minh, which in the preceding months, had secretly organizedso-called “People’s Revolutionary Committees” throughout much of thecolony. These “People’s RevolutionaryCommittees” now seized power and organized local administrations in many townsand cities, more particularly in the northern and central regions, includingthe capital Hanoi. This seizure of power, historically calledthe August Revolution, led to the abdication of ex-emperor Bao Dao and thecollapse of his Japanese-sponsored government.

The August Revolution succeeded largely because the VietMinh had gained much popular support following a severe famine that hitnorthern Vietnam in the summer of 1944 to 1945 (which caused some 400,000 to 2million deaths). During the famine, theViet Minh raided several Japanese and private grain warehouses. On September 2, 1945 (the same day Japansurrendered to the Allies), Ho proclaimed the country’s independence as theDemocratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), taking the position of President of aprovisional government.

At this point, Ho sought U.S.diplomatic support for Vietnam’sindependence, and incorporated part of the 1776 U.S. Declaration ofIndependence in his own proclamation of Vietnamese independence. Ho also wrote several letters to U.S.President Harry Truman (which were unanswered), and met with U.S. StateDepartment and OSS officials in Hanoi. However, during the war-time Potsdam Conference (July 17 – August 2,1945), the Allied Powers (including the Soviet Union) decided to allow Franceto restore colonial rule in Indochina, but that in the meantime that France wasyet preparing to return, Vietnam was to be partitioned into two zones north andsouth of the 16th parallel, with Chinese Nationalist forces tasked to occupythe northern zone, and British forces (with some French units) tasked to enterthe southern zone.

By mid-September 1945, Chinese and British forces hadoccupied their respective zones. Theythen completed their assigned tasks of accepting the surrender of, as well asdisarming and repatriating the Japanese forces within their zones. In Saigon,British forces disbanded the Vietnamese revolutionary government that had takenover the administration of the city. This Vietnamese government in Saigon, called the “Provisional ExecutiveCommittee”, was a coalition of many organizations, including the religiousgroups Cao Dai and Hoa Hao, the organized crime syndicate Binh Xuyen, thecommunists, and nationalist organizations. In Cochinchina and parts of Annam,unlike in Tonkin, the Viet Minh had onlyestablished partial authority because of the presence of these many rivalideological movements. But believingthat nationalism was more important than ideology to achieve Vietnam’s independence,the Viet Minh was willing to work with other groups to form a united front tooppose the return of French rule.

As a result of the British military actions in the southernzone, on September 17, 1945, the DRV in Hanoilaunched a general strike in Saigon. British authorities responded to the strikesby declaring martial law. The Britishalso released and armed some 1,400 French former prisoners of war; the latterthen launched attacks on the Viet Minh, and seized key governmentinfrastructures in the south. OnSeptember 24, 1945, elements of the Binh Xuyen crime syndicate attacked andkilled some 150 French nationals, which provoked retaliatory actions by theFrench that led to increased fighting. British and French forces soon dispersed the Viet Minh from Saigon. The latterresponded by sabotaging ports, power plants, communication systems, and othergovernment facilities.

By the third week of September 1945, much of southern Vietnam wascontrolled by the French, and the British ceded administration of the region tothem. In late October 1945, anotherBritish-led operation broke the remaining Viet Minh resistance in the south,and the Vietnamese revolutionaries retreated to the countryside where theyengaged in guerilla warfare. Also in October,some 35,000 French troops arrived in Saigon. In March 1946, British forces departed from Indochina, ending their involvement in the region.

Meanwhile in the northern zone, some 200,000 Chineseoccupation forces, led by the warlord General Lu Han, allowed Ho Chi Minh andthe Viet Minh to continue exercising power in the north, on the condition thatHo include non-communists in the Viet Minh government. To downplay his communist ties, in November1945, Ho dissolved the ICP and called for Vietnamese nationalist unity. In late 1945, a provisional coalitiongovernment was formed in the northern zone, comprising the Viet Minh and othernationalist organizations. In January1946, elections to the National Assembly were held in northern and central Vietnam, wherethe coalition parties agreed to a pre-set division of electoral seats.

The Chinese occupation forces were disinclined to relinquishcontrol of northern Vietnamto the French. Chinese officers alsoenriched themselves by looting properties, engaging in the opium trade in Vietnam and Laos,and running black market operations in Hanoi andHaiphong. However, the Chinese commander also was awareof the explosive nature of the hostile French and Vietnamese relations, whilethe French and Vietnamese suspected the Chinese of harboring territorialambitions in northern Vietnam.

But the Chinese Army, which held the real power, also openednegotiations with the French government, which in February 1946, led to anagreement where the Chinese would withdraw from Vietnam in exchange for Francerenouncing its extraterritorial privileges in China and granting economicconcessions to the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam.

In March 1946, Major Jean Sainteny, a French governmentrepresentative, signed an agreement with Ho, where Francewould recognize Vietnam as a“free statehaving its own government, its own parliament, its own army, and its ownfinances, forming a part of the Indo-china Federation and the FrenchUnion”. In exchange, the Viet Minh wouldallow some 15,000 French troops to occupy northern Vietnam for a period of fiveyears. The agreement also stipulatedthat the political future of Vietnam,including whether Cochinchina would form part of Vietnam or remain as a Frenchpossession, was to be determined through a plebiscite. Soon thereafter, French forces arrived in Hanoi and northern Vietnam. In June 1946, Chinese forces withdrew from Vietnam.

Throughout the summer of 1946 in Dalat (in Vietnam) and Fontainebleau(in France), Ho Chi Minhheld talks with French government officials regarding Vietnam’sfuture. The two sides were so far apartthat essentially nothing was accomplished, save for a temporary agreement (amodus vivendi), signed in September 1946, which called for furthernegotiations. Meanwhile in Saigon,Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu, the French High Commissioner for Indochina,refused to acknowledge that the Ho-Sainteny agreement includedCochinchina. In June 1946, withoutconsulting the French national government, he established the “AutonomousRepublic of Cochinchina”, which seriously undermined the ongoing talks in France.

In the summer of 1946, the Viet Minh purged non-communistsfrom its party ranks, effectively restoring the DRV into a fully communistentity. By September 1946, tensions hadrisen between French and Viet Minh forces, which led to armed threats andprovocations. In November 1946, fightingbroke out in Haiphongwhen French port authorities seized a Chinese junk, but were in turn fired uponby the Viet Minh. The French firstdemanded that the Viet Minh yield control of Haiphong, and then bombarded the city usingnaval and ground artillery, and air strikes. The French gained control of Haiphong,expelling the Viet Minh, with 6,000 civilians killed in the fighting.