Daniel Orr's Blog, page 22

May 27, 2024

May 27, 1905 – Russo-Japanese War: The start of the Battle of Tsushima

On May 27, 1905, the Japanese Navy engaged the Russian Second Pacific fleet in the two-day Battle of Tsushima (May 27-28, 1905). In the aftermath, the Russian fleet was annihilated, with 10,000 Russian sailors killed or captured, 21 ships sunk, including 7 battleships, and of the 38 Russian ships that started the voyage, only 3 managed to reach Vladivostok. Japanese losses were 700 dead or wounded, and only 3 torpedo boats sunk.

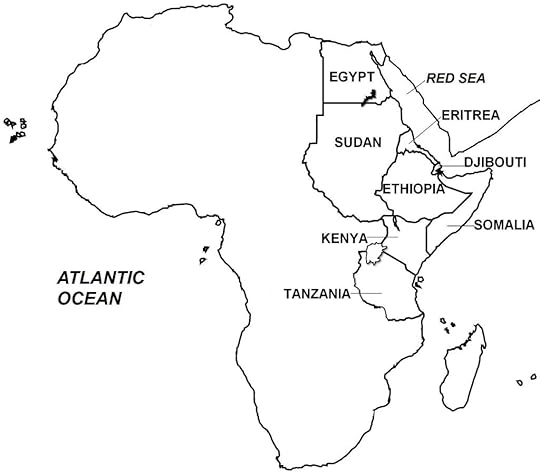

Route taken by the Russian fleet from the Baltic Sea to the Far East

Route taken by the Russian fleet from the Baltic Sea to the Far EastBackground ByMarch 1905, Japanese forces had gained control of the entire southernManchuria, including Port Arthur,the strong Russian outpost. But they hadfailed to annihilate the Russian Army (which remained relatively potent despitethe high losses). Because of seriouslogistical problems, the Japanese Army decided to abandon plans to advancefurther north.

Despite the series of battlefield defeats, Tsar Nicholas IIcontinued to believe that the Russian Army would prevail eventually in aprotracted war. The now completedTrans-Siberian Railway could transfer more troops and weapons to the Far East. Butthese hopes would be dashed in the Battle of Tsushima.

In October 1904, while the Japanese Third Army was yetbesieging Port Arthur, Tsar Nicholas II orderedthe Russian Baltic Fleet, which was led by eight battleships, to head for Port Arthur and break theJapanese naval blockade, and reinforce the Russian Pacific Fleet. The Russian Baltic Fleet, soon renamed theSecond Pacific Fleet, then embarked on a seven-month (October 1904-May 1905)33,000-kilometer voyage half-way around the world by way of the Cape of GoodHope, and around the southern tip of Africa. The Russian fleet was forced to take thismuch longer route after being denied passage across the Suez Canal by Britain following the Dogger Bank incident. In thisincident, which occurred in the North Sea inOctober 1904, the Russian fleet fired on British trawlers, mistaking them forJapanese torpedo boats. The incidentsparked a furious British government protest that nearly led to war between Britain and Russia.

In January 1905, while yet in transit, the Russian fleetreceived information that Port Arthurhad fallen. As a result, it was instructed to head for Vladivostok instead. By May 1905, the Russian fleet had enteredthe waters south of the Sea of Japan, and while traversing the Tsushima Strait,located between Japan and Korea,the fleet was spotted by a Japanese ship, which then alerted the JapaneseNavy. In the previous months, theJapanese had followed the progress of the Russian fleet’s voyage, and thusprepared to do battle with it in a decisive showdown.

The Battle of Tsushima sent reverberations around the World – an Asian nation dealing a crushing defeat on a European power. In Russia, Tsar Nicholas II abandoned his hard-line position against Japan. On June 8, 1905, one week after the Tsushima battle, Russia agreed to negotiate an end to the war. (Excepts taken from the Russo-Japanese War).

May 26, 2024

May 26, 1900 – Thousand Days’ War: Colombia’s Conservative forces defeat Liberal militias at the Second Battle of Palonegro

The rivalry between Colombia’s Conservative and Liberalpolitical parties lies at the heart of the Thousand Days’ War, which took placefrom 1899 to 1902. Colombia was a democracy andelections were held to decide between Conservatives, who advocated a strongcentralized government and greater union between church and state; andLiberals, who favored a decentralized national government and separation ofchurch and state. Colombia’s politics were bitter andviolent, however, and coups, assassinations, and even civil wars, often brokeout. Ethnicity and social class alsofactored in the discord, as Conservatives were led by the Spanish-descendedelite and wealthy landowners, while Liberals consisted of Spanish-Amerindianmestizos and were backed by middle-class merchants, traders, and smallerlandowners. Peasants, who formed thevast majority of Colombian society, supported either one of the two parties.

Thousand Days’ War

Thousand Days’ WarIn 1866, the ruling Conservative government passed a newconstitution that advocated a centralized government and greater union betweenchurch and state. The constitution hadbeen a joint effort by Conservatives and Liberals. Later, however, some Liberals asserted thatsome of the charter’s provisions were unfair and needed to be amended. As a result, two Liberal uprisings broke outin 1893 and 1895, both of which were quelled.

In 1899, Colombiaagain was on the verge of a conflict, caused by economic and politicalfactors. World coffee prices hadplummeted, hitting hard local coffee growers who were ready to break out inrevolt. The Liberals also were set totake up arms after being defeated in the previous year’s elections to theConservatives whom they accused of cheating.

Fighting broke out in Santander Province,where the Liberals had assembled their militia to face the much largerConservative forces. At the First Battleof Palonegro, fought in November 1899, Conservative forces prevailed. However, they were turned back by theLiberals at Peralonso the following month, setting the stage for a decisivebattle. In May 1900, Conservative forcesinflicted a crushing defeat on the Liberals in the Second Battle ofPalonegro. Left with insufficient forcesto continue fighting conventional battles, the Liberals retreated to thehinterlands and formed small groups to begin a guerilla war.

Toward the end of 1902, representatives from the two sides met in a series of dialogues, which led to the signing of a peace treaty that ended the war. Some 100,000 people were killed in the war. (Extracts for this write-up were taken from here. )

Panama’sSecession At the time of the war, Panamawas a “departamento” (province) of Colombia. Rebel activity was prevalent in Panama, with the insurgents even attempting toseize the Panama Railway, a U.S.facility. As a result, the United Statessent troops to protect the installation. In November 1903, or a year after the war had ended, Panama seceded from Colombia, forming its ownindependent state. The secession hadbeen preceded by an uprising that was openly supported by the United States. Colombia, still reeling from the ThousandDays’ War, was unable to prevent the secession.

May 25, 2024

May 25, 1938 – Spanish Civil War: Italian planes bomb Alicante, killing over 300 civilians

On May 25, 1938, the Spanish city of Alicante was bombed by Italian planes (belonging to the Aviazione Legionaria) during the Spanish Civil War. Over 300 people were killed, while another 1,000 were injured.

Key areas during the Spanish Civil War

Key areas during the Spanish Civil WarThe Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) pitted government forces called “Republicans” against rebel forces called “Nationalists.” The Republicans were supported by unions, communists, anarchists, workers, and peasants, while the Nationalists were backed by the bourgeoisie, landlords, and the upper class. In the wider European context just before the outbreak of World War II, the Republicans were supported by the Soviet Union and European democracies, while the Nationalists were backed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

Alicante was a Republican stronghold and was bombed many times during the war. General Francisco Franco, leader of the Nationalists, envisioned that the Alicante bombing on May 25, 1938 would eliminate the Republicans’ maritime commerce and destroy morale.

The aerial attack on Alicante coincided with similar indiscriminate bombings on Valencia, Barcelona, Granollers and other Republican-held towns and cities, which were carried out by the Aviazione Legionaria and the German Legion Condor.

Background of the Spanish Civil War (Excerpts taken from here.) In January 1930, General Miguel Primo de Rivera, Spain’s military dictator, was forced to step down from office. His ambitious infrastructure programs and socio-economic reforms had failed, and the ongoing Great Depression was devastating Spain’s economy. Spain’s unpopular monarch, King Alfonso XIII, formed two governments in succession, but both collapsed after failing to calm the growing unrest among the Spanish people. Consequently, new elections were called.

In the past, Spain’s politics had beenmonopolized by the political elite belonging to the Conservative and Liberalparties. In Spainof the early twentieth century, however, the emergence of many factors,including industrialization, labor unions, radical ideologies, publicdiscontent, anti-monarchical and anti-cleric sentiments, and separatistmovements, were all converging to radically transform Spain’s political climate.

In the municipal elections of April 1931, ananti-monarchical political coalition of leftist republicans and socialists cameto power and formed a republican government (called the Spanish Second Republic**). The military regime ended and King Alfonso XIII was forced to step downand leave for exile abroad. Thus, theSpanish monarchy ended.

The now ruling political left blamed theChurch and the monarchy for Spain’smany ills, including the socio-economic inequalities, loss of the empire’s vastterritories, and backwardness compared to other more industrialized Europeancountries.

Then in general elections held in June 1931,leftist republicans and socialists again won a majority, this time forparliament, and thereafter convened the CortesGenerales (Spanish legislature). The newgovernment, wanting to secularize the state, passed a new constitution inDecember 1931, which removed the Catholic Church’s pre-eminence over thecountry’s social and educational institutions. The new constitution promoted civil liberties and guaranteed free speechand the right to assembly, as well as universal suffrage, where women, for thefirst time, were allowed to vote.

The constitution also nationalized industriesand began an agrarian reform program. The right to regional self-determination was upheld; as a result, theregions of Basque and Catalonia, both hotbeds of separatism, gained political autonomy. The libertarian atmosphere generated by thenew regime encouraged violent anti-clericalism: starting in May 1931, manychurches, monasteries, convents, and other religious buildings in Madridand across Spainwere burned down, destroyed, or vandalized.

Spain’s traditional political elite, whichconstituted and defended the interests of the upper classes and the CatholicChurch, looked on with great alarm, as the changes threatened to destroy longvenerated Spanish institutions. In thecountryside, tensions rose between peasants and landowners, destabilizing thequasi-feudalistic agrarian system of the latifundia, i.e. the vastagricultural plantations owned by the small upper class. In August 1932, army officers, led by GeneralJose Sanjurjo, carried out an unsuccessful uprising because of his oppositionto the government’s reforms in the military establishment.

Concerned by the rising instability, the government slowed down the pace of reforms, which then drew the indignation of labor unions and peasant sector. The economic devastation caused by the ongoing Great Depression also eroded popular support for the regime. In general elections held in November 1933, centrist and right-wing political parties emerged victorious. A center-right government was formed, which reversed or stalled the previous regime’s reforms. Then in October 1934 when the right-wing party CEDA (or Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas) put pressure on the center-led coalition government that saw the appointment of CEDA into Cabinet positions, the Unión General de Trabajadores, a powerful workers’ union associated with the socialist party, launched a nationwide general strike. The strikes failed in most areas.

However, the strikes were successful(initially) in Catalonia, and morespectacularly carried out in Asturias. In the latter, in the event known as theAsturias miners’ strike of 1934, thousands of miners took over many towns and villages, including Oviero, the provincial capital, where the Catholic cathedral and governmentbuildings were burned down, and local officials and clergy were executed. Units of the Spanish Army were called in, ledby two commanders one of whom was General Francisco Franco. After two weeks of fighting, therevolt was crushed and thousands of workers were executed or imprisoned.

Consequently, military officers who werethought to be supportive of the government (i.e. right-wing) were promoted,including General Franco, who became commander-in-chief of the armedforces. Politically and socially, thecountry had become polarized into two opposite, mutually hostile forces: theleft and the right. The left targetedrightist sectors: the church with executions and arson, employers with militantactions, and agricultural landowners with seizure of farmlands. In turn, the political right killed andjailed union leaders and left-leaning intellectuals and academics.

At this time, thousands of youths fromright-wing and monarchist organizations joined the FalangeEspañola de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista or simply Falange, a fascist partyinfluenced by founding movements in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Many leftists also began to embrace moreradical and violent ideas, including armed revolution.

In general elections held in February 1936,the Popular Front, a coalition of leftist republicans, socialists, andcommunists, emerged victorious, only edging out the combined right-wing andcentrist votes but gaining a clear majority in parliament. The leftist victory came about in large partbecause of the electoral participation of the anarchists who, represented bythe anarchist labor union ConfederaciónNacional del Trabajo or CNT,were infuriated by the right-wing government’s anti-anarchist policies. With the leftist electoral victory, a wave oflawlessness took place, as leftist elements forced the release of jailedpolitical prisoners (without judicial proceedings) and peasants seizedfarmlands.

A leftist government was formed, which demotedor re-assigned military officers who were deemed to be right-wing; among theseofficers was General Franco, who was dismissed as commander-in-chief andtransferred to the distant Canary Islands. Also affected by therestructuring was General Emilio Mola, who was transferred to the northern provinceof Navarre,a monarchist stronghold, from where he began to conspire with other officers ina plot to overthrow the government. Themotivation for the plot was the perceived need to save the country fromself-destruction and/or communism. Byearly July, many military commands in Spain were ready to carry out thecoup; General Franco wavered for some time before also opting in.

In the plan, Spain’s forces in Spanish Morocco would launch a revolt on July 17,to be followed by the Spanish Army in the mainland the next day. Then on July 18, Spanish Moroccan Army would arrive in mainland Spainand together with the peninsular forces, would overthrow the government.

In Madridon July 12, 1936, an Assault Guard police officer, who also belonged to theSocialist Party, was shot and killed by Falangists. The next day, Assault Guards arrested andkilled Jose Calvo Sotelo, a monarchist politician and the leading right-wingparliamentarian. Retaliatory killingsfollowed these two incidents. Sotelo’smurder served as the tipping point for the military officers to launch thecoup.

** The First Spanish Republicexisted between February 1873 to December 1874 after the Spanish monarch, KingAmadeo I, abdicated; the republic ended with the proclamation of King AlfonsoXII.

May 24, 2024

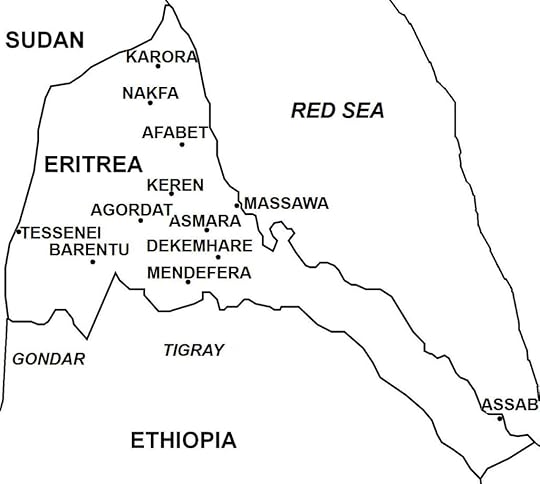

May 24, 1991 – Eritrean War of Independence: Eritrea gains its independence from Ethiopia

On May 24, 1991, Eritreagained its independence from Ethiopiafollowing a 30-year armed revolution. Ethiopiahad annexed Eritreaas a province in November 1962, inciting Eritrean nationalists to launch arebellion.

Following the war, as Eritrea was still legally bound aspart of Ethiopia, in early July 1991, at a conference held in Addis Ababa, aninterim Ethiopian government was formed, which stated that Eritreans had theright to determine their own political future, i.e. to remain with or secedefrom Ethiopia.

Then in a UN-monitored referendum held in April 23 and 25, 1993, Eritreans voted overwhelmingly (99.8%) for independence; two days later (April 27), Eritrea declared its independence. In May 1993, the new country was admitted as a member of the UN.

(Excerpts taken from Eritrean War of Independence – Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 4)

Background In September 1948, a special body called the Inquiry Commission, which was set up by the Allied Powers (Britain, France, Soviet Union, and United States), failed to establish a future course for Eritrea and referred the matter to the United Nations (UN). The main obstacle to granting Eritrea its independence was that for much of its history, Eritrea was not a single political sovereign entity but had been a part of and subordinate to a greater colonial power, and as such, was deemed incapable of surviving on its own as a fully independent state. Furthermore, various countries put forth competing claims to Eritrea. Italy wanted Eritrea returned, to be governed for a pre-set period until the territory’s independence, an arrangement that was similar to that of Italian Somaliland. The Arab countries of the Middle East pressed for self-determination of Eritrea’s large Muslim population, and as such, called for Eritrea to be granted its independence. Britain, as the current administrative power, wanted to partition Eritrea, with the Christian-population regions to be incorporated into Ethiopia and the Muslim regions to be assimilated into Sudan. Emperor Haile Selassie, the Ethiopian monarch, also claimed ownership of Eritrea, citing historical and cultural ties, as well as the need for Ethiopia to have access to the sea through the Red Sea (Ethiopia had been landlocked after Italy established Eritrea).

Ultimately, the United Statesinfluenced the future course for Eritrea. The U.S.government saw Eritrea inthe regional balance of power in Cold War politics: an independent but weak Eritrea could potentially fall to communist(Soviet) domination, which would destabilize the vital oil-rich Middle East. Unbeknown to the general public at the time, a U.S. diplomatic cable from Ethiopia to the U.S. State Department in August1949 stated that British officials in Eritrea believed that as much as75% of the local population desired independence.

In February 1950, a UN commission sent to Eritrea todetermine the local people’s political aspirations submitted its findings tothe United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). In December 1950, the UNGA, which was strongly influenced by U.S. wishes, released Resolution 390A (V) thatcalled for establishing a loose federation between Ethiopiaand Eritrea to befacilitated by Britainand to be realized no later than September 15, 1952. The UN plan, which subsequently wasimplemented, allowed Eritreabroad autonomy in controlling its internal affairs, including local administrative,police, and fiscal and taxation functions. The Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation would affirm the sovereignty of theEthiopian monarch whose government would exert jurisdiction over Eritrea’sforeign affairs, including military defense, national finance, andtransportation.

In March 1952, under British initiative, Eritrea electeda 68-seat Representative Assembly, a legislature composed equally of Christiansand Muslim members, which subsequently adopted a constitution proposed by theUN. Just days before the September 1952deadline for federation, the Ethiopian government ratified the Eritreanconstitution and upheld Eritrea’sRepresentative Assembly as the renamed Eritrean Assembly. On September 15, 1952, the Ethiopian-EritreanFederation was established, and Britainturned over administration to the new authorities, and withdrew from Eritrea.

However, Emperor Haile Selassie was determined to bring Eritrea under Ethiopia’s full authority. Eritrea’s head of government(called Chief Executive who was elected by the Eritrean Assembly) was forced toresign, and successors to the post were appointed by the Ethiopianemperor. Ethiopians were appointed tomany high-level Eritrean government posts. Many Eritrean political parties were banned and press censorship wasimposed. Amharic,Ethiopia’s officiallanguage, was imposed, while Arabic and Tigrayan, Eritrea’s mainlanguages, were replaced with Amharic as the medium for education. Many local businesses were moved to Ethiopia, while local tax revenues were sent to Ethiopia. By the early 1960s, Eritrea’sautonomy status virtually had ceased to exist. In November 1962, the Eritrean Assembly, under strong pressure fromEmperor Haile Selassie, dissolved the Ethiopian-Eritrean Federation and votedto incorporate Eritrea as Ethiopia’s 14th province.

Eritreans were outraged by these developments. Civilian dissent in the form of rallies anddemonstrations broke out, and was dealt with harshly by Ethiopia,causing scores of deaths and injuries among protesters in confrontations withsecurity forces. Opposition leaders,particularly those calling for independence, were suppressed, forcing many toflee into exile abroad; scores of their supporters also were jailed. In April 1958, the first organized resistanceto Ethiopian rule emerged with the formation of the clandestine EritreanLiberation Movement (ELM), consisting originally of Eritrean exiles in Sudan. At its peak in Eritrea, the ELM had some40,000 members who organized in cells of 7 people and carried out a campaign ofdestabilization, including engaging in some militant actions such asassassinating government officials, aimed at forcing the Ethiopian governmentto reverse some of its centralizing policies that were undercutting Eritrea’sautonomous status under the federated arrangement with Ethiopia. By 1962, the government’s anti-dissidentcampaigns had weakened the ELM, although the militant group continued to exist,albeit with limited success. Also by1962, another Eritrean nationalist organization, the Eritrean Liberation Front(ELF), had emerged, having been organized in July 1960 by Eritrean exiles inCairo, Egypt which in contrast to the ELM, had as its objective the use ofarmed force to achieve Eritrean’s independence. In its early years, the ELF leadership, called the “Supreme Council”,operated out of Cairoto more effectively spread its political goals to the international communityand to lobby and secure military support from foreign donors.

May 23, 2024

May 23, 1945 – World War II: Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, commits suicide

On May 23, 1945, Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer (Reich Leader) of the Schutzstaffel (SS; Protection Squadron), while in Allied custody, committed suicide by biting into a cyanide pill in his mouth.

Himmler was a main architect of the Holocaust, and set up and controlled the Nazi concentration camps. He was both Chief of German Police and Minister of the Interior, overseeing all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo (Secret State Police). As facilitator and overseer of the concentration camps, Himmler directed the killing of some six million Jews, between 200,000 and 500,000 Romani people, and other victims; the total number of civilians killed by the Nazi regime is estimated at 11 – 14 million people.

By April 1945, realizing the war was lost, Himmler tried to open peace talks with the Western Allies without Hitler’s knowledge shortly before the end of the war. Upon learning of this, Hitler dismissed him from all his posts and ordered his arrest. Himmler attempted to go into hiding, but was detained and arrested by British forces once his identity became known. While in British custody, he committed suicide on May 23, 1945.

By the time of his death, World War II was officially over. Admiral Karl Doenitz, head of the German Navy and Hitler’s successor, had surrendered Germany in instruments signed on May 7 and May 8, 1945. The scattered German units across Europe surrendered before and after the official surrender dates.

Apart from Hitler (who committed suicide on April 30, 1945) as well as Himmler, other high-ranking Nazi officials who took their own lives were Joseph Goebbels (Minister of Propaganda) and his wife after poisoning their six children with cyanide, on May 1, 1945; Martin Bormann, Secretary to the Fuhrer and chief of the Nazi Party Head Office, determined to have already died perhaps by suicide, on May 2, 1945; and Hermann Goering, Vice-Chancellor and head of the Luftwaffe, on the night before his execution, on October 15, 1946.

Hermann Hess, former Deputy Fuhrer, also committed suicide by hanging while serving life sentence in Spandau Prison in August 1987. He was 93 years old, and speculation arose that he was murdered, pointing to his advanced age, that he could not have been physically capable of hanging himself.

May 22, 2024

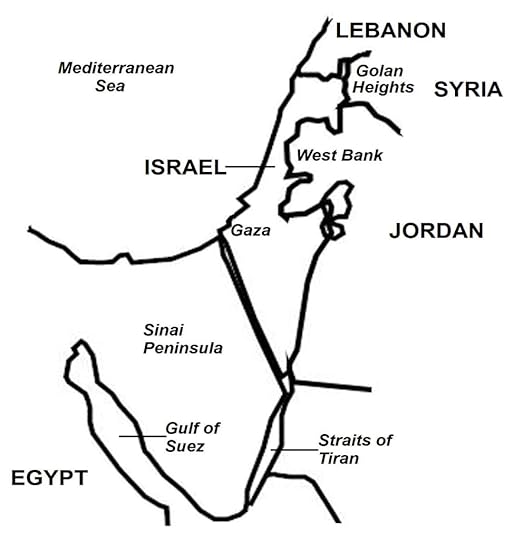

May 22, 1967 – Six-Day War: Egypt closes the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping

On May 22, 1967, Egypt announced that the Straits of Tiran would be closed to “all ships flying Israeli flags or carrying strategic materials”, to take effect on May 23. Some 90% of Israeli oil passed through the Straits of Tiran. Oil tankers that were due to pass through the straits were delayed. Israel had previously warned that the closure of the waterway would be an act of war.

The waterway’s closure greatly increased tensions between the Arab states and Israel. Just one week earlier, May 15, 1967, Egypt had ordered the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) to leave the Sinai Peninsula; the UNEF had been tasked to preserve the peace in the territory since the end of the Suez Crisis (October-November 1956).

Background The 1948 Arab-Israeli War produced tensions between Israel and surrounding Arab countries. Then in 1956, Egypt seized control of the Suez Canal, which triggered the Suez Crisis, a conflict where Britain and France sent their forces to Egypt to take back control of the Suez Canal. Israel joined the Anglo-French operation by invading and capturing the Sinai Peninsula. The United Nations, or UN, subsequently forced Israel to withdraw its forces from the Sinai Peninsula.

In the 1960s, tension rose again in the Middle East,initially between Syria and Israel. Palestinian militants belonging to thePalestinian Liberation Organization, or PLO, Fatah, and other nationalistguerilla movements, carried out armed raids and sabotage operations in Israel from bases in Syria,Jordan, and southern Lebanon. In the first three months of 1967, some 270armed incidents occurred between Israel and its Arab neighbors. Israeli planes struck at suspectedPalestinian bases inside Syria. Israeland Syria also were lockedin a dispute regarding the water resources in the Jordan River, ultimatelyleading Israelto launch air strikes against Syrian water facilities in August 1965.

Border clashes also broke out intermittently. Israeli planes attacked Syrian military basesand vital public infrastructures, and shot down a number of Syrian planes inair battles. In April 1967, Israeli andSyrian forces clashed in a major battle that included infantry, armored,artillery, and air force units.

Persistent PLO infiltrations from Syriaprompted Israel,in May 1967, to issue a warning to Syria of Israeli retaliation. Then, the Soviet Unionreleased an intelligence report (later discovered to be erroneous) to the Arabsthat indicated an Israeli troop buildup along the Syrian border. As a result, Syriaalso massed its forces along the border with Israel.

Egypt wasbound to a defense agreement with Syriaand Jordan. On May 18, the Egyptian government expelledthe UN peacekeepers in the Sinai, and sent army units to the Egypt-Israelborder, thereby militarizing the Sinai Peninsula. A few days later, Egyptprevented Israelcommercial vessels from entering the Straits of Tiran. Israel viewed the blockade as aprovocation for war.

On May 28, Israelprepared for war with a call up of reservists. Three days later, foreign embassies in Israel instructed their citizens toleave in anticipation for war. On June1, Israelfinalized its war plans. Then in ameeting held on June 4, Israel’scivilian and military leaders set the date for war for the following day, June5.

Israelfought the Six-Day War in three sectors: against Egyptin the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula, against Jordanin the West Bank, and against Syriain the Golan Heights.

War On the morning of June 5, Israeli planes attacked Egyptian airbases in the Sinai Desert and in Egypt proper. Hundreds of Egyptian planes, nearly half of Egypt’s Air Force, were destroyed on the ground. Israeli air strikes continued the whole day, knocking out the Egyptian Air Force, which was the strongest among the Arab countries. In one coup, Israel gained air domination, which decided the outcome of the war. The Six-Day War was on.

May 21, 2024

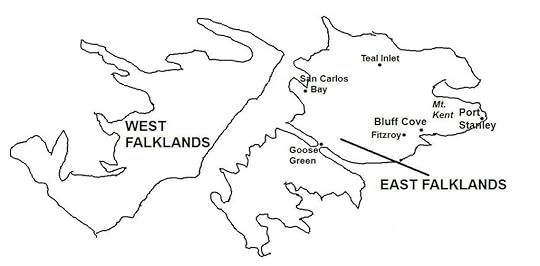

May 21, 1982 – Falklands War: British Marines land in San Carlos

By the third week of May 1982, the ships carrying the British ground forces had arrived at the waters off the Falklands. British authorities decided to launch the ground war despite not having achieved total control of the sky because the rough seas and deteriorating weather conditions indicated that winter in the South Atlantic was fast approaching. San Carlos Bay, a lightly defended area located about centrally north of the East Falklands, was chosen as the landing point. The British were unwilling to launch a direct attack on the capital Port Stanley, believing this would cause heavy British casualties.

Falkland Islands

Falkland IslandsOn May 21, 1982, some 4,000 British Marines landed at San Carlos Bay. After easily overpowering the small Argentine garrison, the Britishsoldiers secured the landing zone, where British transport ships soon arrivedto unload weapons and supplies. TheArgentineans carried out many air attacks, sinking the British frigates HMS Ardent and HMS Antelope on May 21 and May 24, respectively, and the destroyerHMS Coventry on May 25. Also badlydamaged were the British frigates HMSArgonaut and HMS Brilliant. Many other ships also could have been hit orsuffered heavy damage were it not that Argentinean pilots often released theirrockets too low, which exploded with little effect or did not detonate on time.

The British incurred heavy losses at San Carlos Bay,but succeeded in completing the landings. However, the loss of a freighter carrying the transport helicopters forthe troops meant that the British ground forces at San Carlos Bay could notbe airlifted to Port Stanley as planned, butwould have to walk the 80 kilometers of open terrain in bad weather to thecapital. The main force of 3,000 troopswas tasked to advance to Port Stanley.

Background Argentina invaded Falklands on April 2, 1982 when 100 Argentinean commandos were landed at Port Stanley, the capital, ahead of the main force of 2,000 soldiers who later were landed amphibiously. After some skirmishes, the island’s British garrison of 60 soldiers surrendered, and the Falklands came under Argentine control.

Argentina then set up a military command to administer the islands. British authorities and military personnel were expelled, and Falklanders were given the option to leave with compensation. (More details on the war here.)

May 20, 2024

May 20, 1941 – World War II: German paratroopers invade Crete

On May 20, 1941, German paratroopers landed on Crete, Greece’slargest island on the south. In early June 1941, the Axis conquest of all Greekterritories was completed by the German capture of Creteafter a two-week offensive. The Battleof Crete involved German paratroopers and glider units seizing strategic pointsin the northern coast preparatory to the arrival of other ground forces. The initial German landings brought neardisaster, as the paratroopers suffered heavy casualties and the Luftwaffe losta significant number of planes. But withthe capture of Maleme airfield following an Allied communications error, theGermans established a toehold in Crete formore troops to arrive. On June 1, 1941,the Germans seized the whole island; some 18,000 Allied soldiers who had failedto be evacuated were captured.

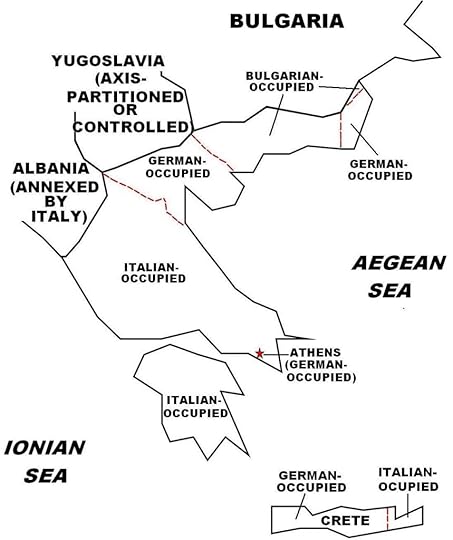

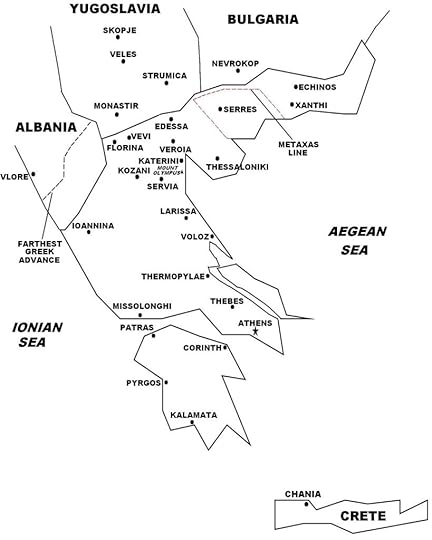

Axis occupation of Greece during World War II

Axis occupation of Greece during World War IIIn the aftermath of the Axis campaign, Greece was divided into Axis occupation zones,with Germany taking the moststrategically important regions, including Athens,and the Italians occupying much of the rest of Greece. Bulgaria,which did not participate in the invasion, was allowed to occupy Western Thraceand Eastern Macedonia. In Athens, theGermans set up a collaborationist government under the renamed “Hellenic State”, which held no real power butserved merely as a conduit for German impositions.

Background On April 6, 1941, Germany launched Operation Marita, the invasion of Greece, with the German 12th Army in Bulgaria launching offensives into southern Yugoslavia, whose capture would achieve the strategic objective of cutting off the rest of Yugoslavia in the north with Greece in the south. By the second week, the Germans had captured nearly the whole Greek mainland. Over the course of five nights starting on April 24, 1941, the British Royal Navy and other Allied ships evacuated 55,000 British and Dominion troops to Crete and Egypt. The British also left behind most of their weapons and military equipment, including trucks, tanks, and planes. For more information on this war, click here.

Battle of Greece

Battle of Greece

May 19, 2024

May 19, 1959 – Vietnam War: North Vietnam forms Group 559, tasked to establish a supply line to South Vietnam; as a result, the Ho Chi Minh Trail is built

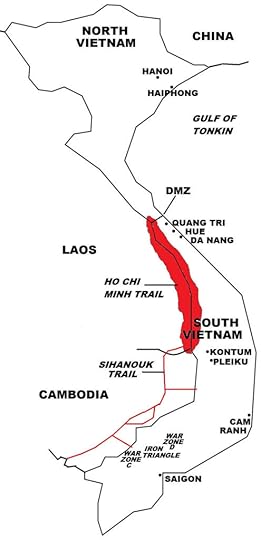

In January 1959, North Vietnam agreed to provide military support to the Viet Cong. In May of that year, it formed the 559th Transportation Group of the North Vietnamese Army, which was tasked to establish a supply route to South Vietnam. This supply route, which initially passed directly through the DMZ, was intercepted by South Vietnamese forces. North Vietnam then moved its supply route to eastern Laos and Cambodia, where manpower and war materials were transported to the Viet Cong in South Vietnam. The supply route that developed, which became known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, was located close to the shared borders of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, and initially consisted of foot tracks in sparsely inhabited rugged mountains that were covered in the dense canopy of tropical rainforests. One year earlier (May 1958), North Vietnamese forces had crossed over into and occupied sections of eastern Laos, including the strategically placed Tchepone in Savannakhet Province, in support of the Pathet Lao, a Laotian communist movement that was fighting a revolutionary war in Laos against the West-aligned Royal Lao Government.

Ho Chi Minh Trail and other sites during the Vietnam War

Ho Chi Minh Trail and other sites during the Vietnam WarWithin a few months after Group 559’s formation, weapons andsupplies from North Vietnamwere being transported in large quantities through the Ho Chi Minh Trail to theinsurgents in South Vietnam. As well, the first batches of Viet Minhsoutherners who had moved to North Vietnam following the Geneva Accords andwere now officers and soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army, were trekking downthe Ho Chi Minh Trail toward South Vietnam, where they would serve as theleaders and advisers of, or otherwise joined the ranks of, the Viet Cong.

Background InJuly 1954, the First Indochina War ended with the Geneva Accords, whichpartitioned the French colony of Vietnam into two military zones atthe 17th parallel, the northern and southern zones. The northern zone was assigned to andoccupied by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV). The DRV was led by the Viet Minh (Vietnamese:Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng MinhHội, or “League for the Independence of Vietnam”), a nationalist communist-ledorganization headed by the revolutionary Ho Chi Minh, who had fought to endFrench colonial rule in Vietnam. The southern zone was assigned to the French-established Stateof Vietnam.

The Geneva Accords stipulated that Vietnam’spartition at the 17th parallel was only a temporary expedient to separate thewarring sides. The 17th parallel wasdesignated as a demilitarized zone (DMZ) of 6 miles wide (3 miles on both sidesof the line), and was not a political/territorial boundary, and thereunification of the two halves of Vietnam was to be undertaken afternationwide elections could be held in July 1956. However, the reunification elections did nottake place, and the DRV in the northern zone and the State of Vietnam in thesouthern zone became de facto separate states, with the former becoming morewidely known as North Vietnam, and the latter known as South Vietnam.

In Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam,Ho and his DRV government consolidated power and established a Marxiststate. All lands and industries werenationalized, agrarian reform was implemented, and dissent suppressed. As in the First Indochina War, North Vietnam received military and economicsupport from the People’s Republic of China(PRC) and the Soviet Union. In South Vietnam, which officially wasa democracy based along Western lines, Prime Minister Ngo Dinh Diem onlygradually consolidated power. In April1955, Diem launched military campaigns to suppress the militant religiousgroups, Cao Dai and Hoa Hao, and the organized crime syndicate, BinhXuyen. These operations were successful,but only after some intense fighting in the capital, Saigon,that left hundreds of people dead and thousands of others homeless. Then in October 1955, to determine South Vietnam’spolitical future, a referendum (which the government manipulated using fraud)showed that the South Vietnamese overwhelmingly favored setting up a republic,and rejected the return of the monarchy. Following the referendum, Diem declared the formation of the Republic of Vietnam(South Vietnam)and named himself as its (first) President. Thereafter, President Diem reached the peak of his political power,although his government became mired in corruption, nepotism, andstagnation. Diem soon also repressed allforms of political dissent.

Also in 1955, President Diem launched a suppression campaignagainst the re-emerging communist movement in South Vietnam, and in August 1956,instituted the death penalty for persons being involved in communism. In the aftermath of the Geneva Accords, some100,000 Viet Minh southerners migrated to North Vietnam, although about 10,000 Viet Minh southerners,with the encouragement of the North Vietnamese leadership, remained in South Vietnam. These stay-behind Viet Minh communistscarried out political activism using front organizations, such as religious,farmers, students, workers, and women groups, in order to conceal theirpolitical objectives, and also to appeal to a wider segment of the population.

In March 1956, the fledging South Vietnamese insurgencyasked for military support from North Vietnam, which was turned down by the Hogovernment, because China and the Soviet Union were reluctant to becominginvolved in another potentially costly war so soon after the recent Korean War(which just ended nearly three years earlier, in July 1953). But in December 1956, when reunification of Vietnam became unlikely and North Vietnam and South Vietnam were forming separate states, North Vietnamagreed to provide only limited support to the insurgents.

In 1957, the South Vietnamese insurgents, whom the Saigon government called Viet Cong (Vietnamese communists; a contraction from the Vietnamese: Việt Nam Cộng-sản), unleashed a wave of violence in South Vietnam, with many incidents of assassinations, murders, bombings, and other terrorist acts taking place. By 1958, the Viet Cong had established a command structure, with militias organized into a regular army-type organization. For more information on this war, click here.

May 18, 2024

May 18, 1955 – First Indochina War: The end of Operation Passage to Freedom, where the U.S. Navy evacuates 310,000 Vietnamese civilians and soldiers, and non-Vietnamese personnel of the French Army from communist North Vietnam to South Vietnam

On May 18, 1955, the U.S. Navy completed Operation Passage to Freedom, evacuating some 300,000 Vietnamese civilians, soldiers, and non-Vietnamese personnel of the French Army from communist North Vietnam to South Vietnam. This action was part of the larger operation led by the French Air Force and hundreds of ships of the French Navy and U.S. Navy as well as other Western countries that moved some one million Vietnamese northerners, predominantly Catholics but also including members of the upper classes consisting of landowners, businessmen, academics, and anti-communist politicians, and the middle and lower classes, moved to the southern zone. This number included more than 200,000 French citizens and soldiers in the French army. The campaign to evacuate particularly targeted Vietnamese Catholics – some 60% of the north’s 1 million Catholics did so, and accounted for 85% of the evacuees to the south.

This mass movement was a result of a stipulation in the GenevaAccords (May 8, 1954) where representatives from the major powers: UnitedStates, Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France, and the Indochina states:Cambodia, Laos, and the two rival Vietnamese states, Democratic Republic ofVietnam (DRV) in the north, and State of Vietnam in the south, met at Geneva (theGeneva Conference) to negotiate a peace settlement for Indochina (as well asKorea). The Conference was held followingthe decisive French defeat at Dien Bien Phu (March-May1954) in the First Indochina War (December 1946 – July 1954).

Present-day Southeast Asia

Present-day Southeast AsiaOn the Indochina issue, onJuly 21, 1954, a ceasefire and a “final declaration” were agreed to by theparties. The ceasefire was agreed to byFrance and the DRV, which divided Vietnam into two zones at the 17thparallel, with the northern zone to be governed by the DRV and the southernzone to be governed by the State of Vietnam. The 17th parallel was intended to serve merely as a provisional militarydemarcation line, and not as a political or territorial boundary. The partitionwas intended to be temporary, pending elections in 1956 to reunify the countryunder a national government.

The French and their allies in the northern zone departedand moved to the southern zone, while the Viet Minh in the southern zonedeparted and moved to the northern zone (although some southern Viet Minhremained in the south on instructions from the DRV). The 17th parallel was also a demilitarizedzone (DMZ) of 6 miles, 3 miles on each side of the line.

The ceasefire agreement provided for a period of 300 dayswhere Vietnamese civilians were free to move across the 17th parallel on eitherside of the line.

The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and State ofVietnam in a massive propaganda campaign to encourage the northerners to movesouth, including spreading rumors that Red China would invade the north, thatthe northern government would confiscate people’s possessions, and distributingpamphlets with slogans such as “Christ has gone south” and “theVirgin Mary has departed from the North”, alleging anti-Catholicpersecution under Ho Chi Minh.

While one million moved from north to south, some 100,000southerners, mostly Viet Minh cadres and their families and supporters, movedto the northern zone.