Daniel Orr's Blog, page 18

July 8, 2024

July 8, 1960 – Cold War: U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers is charged for espionage by the Soviet Union

On May 1, 1960, a United States U-2 spy plane piloted byFrancis Gary Powers was shot over Soviet airspace by a Russian surface-to-airmissile. Power’s mission, directed bythe U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), was to take surveillancephotographs on an overflight over central Russiafrom a base in Pakistan toanother base in Norway.

Powers survived by parachuting to the ground where he was arrested by Soviet authorities. The U.S. government of President Dwight D. Eisenhower initially stated that the plane was on a NASA research mission but later admitted that the U-2 was conducting surveillance of Russian territory after the Soviet government produced the captured pilot and evidence of the plane’s wreckage, and more important, the intact surveillance equipment and photographs of Soviet military installations taken during the flight.

Subsequently, Powers was convicted of espionage andsentenced to ten years imprisonment. Hedid not serve the full sentence but was released in February 1962 on a prisonerexchange “spy swap” agreement between the American and Soviet governments.

Following the 1960 incident, the United States made changes to policy, procedures, and protocols regarding surveillance and reconnaissance missions. Subsequently, the U-2 was used in overflight missions in Cuba when in August 1962, the first evidence of the presence of Soviet nuclear-capable surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites were detected on the island, sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis.

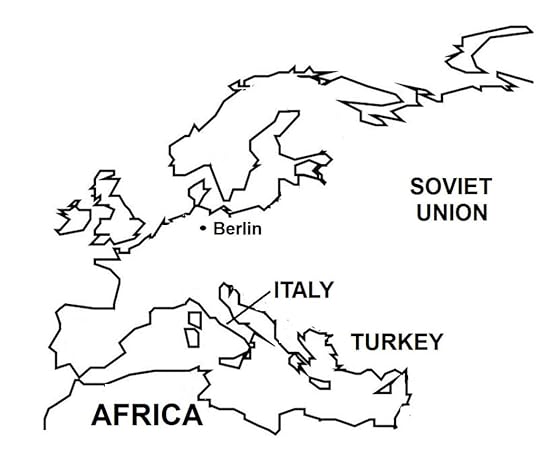

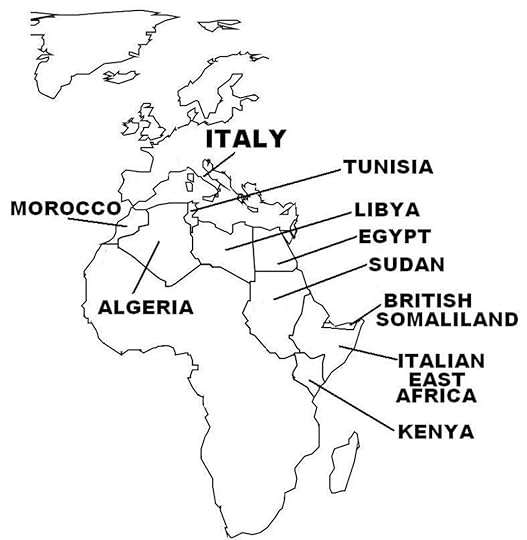

NATO’s deployment of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s decision to install nuclear weapons in Cuba.

NATO’s deployment of nuclear missiles in Turkey and Italy was a major factor in the Soviet Union’s decision to install nuclear weapons in Cuba.(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2)

Background of the Cuban Missile Crisis After the unsuccessful Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961 (previous article), the United States government under President John F. Kennedy focused on clandestine methods to oust or kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro and/or overthrow Cuba’s communist government. In November 1961, a U.S. covert operation code-named Mongoose was prepared, which aimed at destabilizing Cuba’s political and economic infrastructures through various means, including espionage, sabotage, embargos, and psychological warfare. Starting in March 1962, anti-Castro Cuban exiles in Florida, supported by American operatives, penetrated Cuba undetected and carried out attacks against farmlands and agricultural facilities, oil depots and refineries, and public infrastructures, as well as Cuban ships and foreign vessels operating inside Cuban maritime waters. These actions, together with the United States Armed Forces’ carrying out military exercises in U.S.-friendly Caribbean countries, made Castro believe that the United States was preparing another invasion of Cuba.

From the time he seized power in Cubain 1959, Castro had increased the size and strength of his armed forces withweapons provided by the Soviet Union. In Moscow,Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev also believed that an American invasion wasimminent, and increased Russian advisers, troops, and weapons to Cuba. Castro’s revolution had provided communismwith a toehold in the Western Hemisphere andPremier Khrushchev was determined not to lose this invaluable asset. At the same time, the Soviet leader began toface a security crisis of his own when the United States under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization(NATO) installed 300 Jupiter nuclear missiles in Italyin 1961 and 150 missiles in Turkey(Map 33) in April 1962.

In the nuclear arms race between the two superpowers, the United States held a decisive edge over the Soviet Union, both in terms of the number of nuclearmissiles (27,000 to 3,600) and in the reliability of the systems required todeliver these weapons. The Americanadvantage was even more pronounced in long-range missiles, called ICBMs(Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles), where the Soviets possessed perhaps nomore than a dozen missiles with a poor delivery system in contrast to the United States that had about 170, which whenlaunched from the U.S.mainland could accurately hit specific targets in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet nuclear weapons technology had been focused onthe more likely war in Europe and therefore consisted of shorter rangemissiles, the MRBMs (medium-range ballistic missiles) and IRBMs(intermediate-range ballistic missiles), both of which if installed in Cuba,which was located only 100 miles from southeastern United States, could targetportions of the contiguous 48 U.S. States. In one stroke, such a deployment would serve Castro as a powerful deterrentagainst an American invasion; for the Soviets, they would have invoked theirprerogative to install nuclear weapons in a friendly country, just as theAmericans had done in Europe. More important, the presence of Sovietnuclear weapons in the Western Hemisphere would radically alter the globalnuclear weapons paradigm by posing as a direct threat to the United States.

In April 1962, Premier Khrushchev conceived of such a plan,and felt that the United States would respond to it with no more thana diplomatic protest, and certainly would not take military action. Furthermore, Premier Khrushchev believed thatPresident Kennedy was weak and indecisive, primarily because of the Americanpresident’s half-hearted decisions during the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion inApril 1961, and President Kennedy’s weak response to the East German-Sovietbuilding of the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

A Soviet delegation sent to Cuba met with Fidel Castro, whogave his consent to Khrushchev’s proposal. Subsequently in July 1962, Cubaand the Soviet Union signed an agreementpertinent to the nuclear arms deployment. The planning and implementation of the project was done in utmostsecrecy, with only a few of the top Soviet and Cuban officials being informed. In Cuba, Soviet technical and militaryteams secretly identified the locations for the nuclear missile sites.

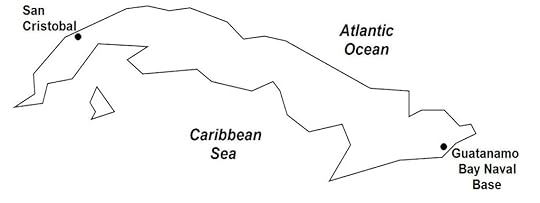

In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane detected a Soviet nuclear missile site under construction in San Cristobal, Pinar del Rio. After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the continued presence of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, a U.S. military facility located at the eastern end of Cuba, greatly infuriated Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane detected a Soviet nuclear missile site under construction in San Cristobal, Pinar del Rio. After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the continued presence of the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, a U.S. military facility located at the eastern end of Cuba, greatly infuriated Cuban leader Fidel Castro.In August 1962, U.S.reconnaissance flights over Cubadetected the presence of powerful Soviet aircraft: 39 MiG-21 fighter aircraftand 22 nuclear weapons-capable Ilyushin Il-28 light bombers. More disturbing was the discovery of the S-75Dvina surface-to-air missile batteries, which were known to be contingent tothe deployment of nuclear missiles. Bylate August, the U.S.government and Congress had raised the possibility that the Soviets wereintroducing nuclear missiles in Cuba.

By mid-September, the nuclear missiles had reached Cubaby Soviet vessels that also carried regular cargoes of conventionalweapons. About 40,000 Soviet soldiersposing as tourists also arrived to form part of Cuba’sdefense for the missiles and against a U.S. invasion. By October 1962, the Soviet Armed Forces in Cubapossessed 1,300 artillery pieces, 700 regular anti-aircraft guns, 350 tanks,and 150 planes.

The process of transporting the missiles overland from Cubanports to their designated launching sites required using very large trucks,which consequently were spotted by the local residents because the oversizedtransports, with their loads of canvas-draped long cylindrical objects, hadgreat difficulty maneuvering through Cuban roads. Reports of these sightings soon reached theCuban exiles in Miami, and through them, the U.S.government.

July 7, 2024

July 7, 1937 – Second Sino-Japanese War: The Marco Polo Bridge Incident takes place

On July 7, 1937, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident became the spark for the outbreak of hostilities between Japan and China in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Marco Polo Bridge (the Western name for the Lugou Bridge) is located southwest of the Chinese capital Beijing. On the evening of July 7, 1937, Japanese military units were conducting military exercises near the bridge when some exchange of gunfire broke out between them and Chinese forces positioned at the other side of the bridge. Soon after, the Japanese command learned that one of its soldiers was missing (but who later returned). Japanese authorities demanded to search Wanping for the missing soldier, which the Chinese refused . By early July 8 with increasing tensions, the two sides began massing infantry and armoured units into the surrounding area of the bridge. Soon, skirmishes and artillery bombardment broke out. Attempts by both sides to negotiate an end to the fighting led to a ceasefire, but which ultimately failed to defuse tensions. Full-scale fighting soon commenced in the capital and elsewhere, starting the Second Sino-Japanese War on July 8, 1937.

In the period before the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, heightenedtensions already existed between the two countries following the JapaneseInvasion of Manchuria in 1931 and further Japanese incursions into northern China.

East Asia.

East Asia.(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5)

Prelude The Japanese invaded Manchuria in September 1931, gaining control of the territory by February 1932. While the Manchurian conflict was yet winding down, another crisis erupted in Shanghai in January1932, when five Japanese Buddhist monks were attacked by a Chinese mob. Anti-Japanese riots and demonstrations led the Japanese Army to intervene, sparking full-scale fighting between Chinese and Japanese forces. In March 1932, the Japanese Army gained control of Shanghai, forcing the Chinese forces to withdraw.

With the League of Nations providing no more than a rebukeof Japan’s aggression,Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek saw that his efforts to force internationalpressure to restrain Japanhad failed. In January 1933, to secure Manchukuo, a combined Japanese-Manchukuo force invaded Jehol Province,and by March, had pushed the Chinese Army south of the Great Wall into Hebei Province.

Unable to confront Japanmilitarily and also beset by many internal political troubles, Chiang wascompelled to accept the loss of Manchuria and Jehol Province. In March 1933, Chinese and Japaneserepresentatives met to negotiate a peace treaty. In May, the two sides signed the Tanggu Truce(in Tanggu, Tianjin), officially ending the war, which provided the followingstipulation that was wholly favorable to Japan: a 100-km demilitarized zone wasestablished south of the Great Wall extending from Beijing to Tianjin, whereChinese forces were barred from entering, but where Japanese planes and groundunits were allowed to patrol.

In the immediate aftermath of Japan’sconquest of Manchuria, many anti-Japanese partisan groups, called “volunteerarmies”, sprung up all across Manchuria. At its peak in 1932, this resistance movementhad some 300,000 fighters who engaged in guerilla warfare attacking Japanesepatrols and isolated outposts, and carrying out sabotage actions against Manchukuoinfrastructures. Japanese-Manchukuoforces launched a series of “anti-bandit” pacification campaigns that graduallyreduced rebel strength over the course of a decade. By the late 1930s, Manchukuowas deemed nearly pacified, with the remaining by now small guerilla bandsfleeing into Chinese-controlled territories or into Siberia.

The conquest of Manchuria formed only one part of Japan’s “North China Buffer State Strategy”, abroad program aimed at establishing Japanese sphere of influence all acrossnorthern China. In 1933, in China’sChahar Province (Figure 32) where a separatistmovement was forming among the ethnic Mongolians, Japanese military authoritiessucceeded in winning over many Mongolian nationalists by promising themmilitary and financial support for secession. Then in June 1935, when four Japanese soldiers who had entered Changpeidistrict (in Chahar Province) were arrested and detained (but eventuallyreleased) by the Chinese Army, Japanissued a strong diplomatic protest against China. Negotiations between the two sides followed,leading to the signing of the Chin-Doihara Agreement on June 27, 1935, where China agreed to end its political,administrative, and military control over much of Chahar Province. In August 1935, Mongolian nationalists, ledby Prince Demchugdongrub, forged closer ties with Japan. In December, with Japanese support,Demchugdongrub’s forces captured northern Chahar, expelling the remainingChinese forces from the province.

In May 1936, the “Mongol Military Government” was formed inChahar under Japanese sponsorship, with Demchugdongrub as its leader. The new government then signed a mutualassistance pact with Japan. Demchugdongrub soon launched two offensives(in August and November 1936) to take neighboring Suiyuan Province,but his forces were repelled by a pro-Kuomintang warlord ally of Chiang. However, another offensive in 1937 capturedthe province. With this victory, inSeptember 1939, the Mengjiang United Autonomous Government was formed, still nominallyunder Chinese sovereignty but wholly under Japanese control, which consisted ofthe provinces of Chahar, Suiyuan, and northern Shanxi.

Elsewhere, by 1935, the Japanese Army wanted to bring Hebei Provinceunder its control, as despite the Tanggu Truce, skirmishes continued to occurin the demilitarized zone located south of the Great Wall. Then in May 1935, when two pro-Japanese headsof a local news agency were assassinated, Japanese authorities presented the Hebei provincialgovernment with a list of demands, accompanied with a show of military force asa warning, if the demands were not met. In June 1935, the He-Umezu Agreement was signed, where China ended its political, administrative, andmilitary control of Hebei Province. Hebei thencame under the sphere of influence of Japan, which then set up apro-Japanese provincial government.

China’slong period of acquiescence and appeasement ended in December 1936 whenChiang’s Nationalist government and Mao Zedong’s Communist Party of Chinaforged a united front to fight the Japanese Army. Full-scale war between China and Japan began eight months later, inJuly 1937.

July 6, 2024

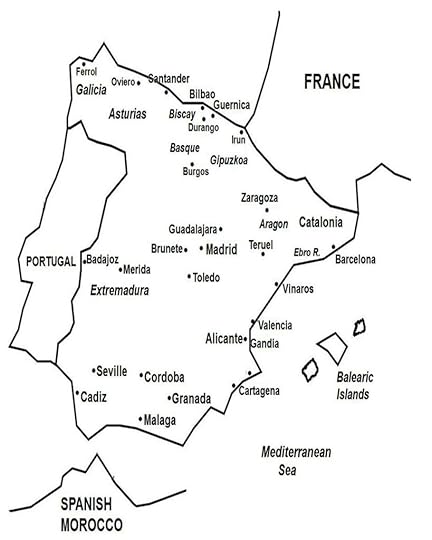

July 6, 1937 – Spanish Civil War: The start of the Battle of Brunete, where Republican forces attack the Nationalists to ease pressure on Madrid

On July 6, 1937, Republican forces launched an offensive on the Nationalists to relieve pressure on the besieged capital Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. The attack gained ground but soon sputtered. With the Nationalists launching a counter-offensive, the Republicans were forced to retreat after suffering heavy losses in men, particularly in the ranks of the International Brigades, as well as material. The International Brigades were a militia organized by the COMINTERN (Communist International) based in Paris, and consisted mostly of communist civilian volunteers from many countries including the Soviet Union, France, United States, Britain, France, Germany and Italy. In total, some 35,000 – 50,000 International Brigades volunteers fought in the Spanish Civil War.

The contribution of the Condor Legion, the Germanexpeditionary air force, to the Nationalist victory, allowed Germany to gain substantial trade concessionsfrom the Nationalists, with the latter agreeing to send raw materials to Germany.

Key areas during the Spanish Civil War

Key areas during the Spanish Civil War(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 3)

Aftermath of the Spanish Civil War Following the war, General Franco established a right-wing, anti-communist dictatorial government centered on the Falange Party. Socialists, communists, and anarchists, were outlawed, as were free-party politics. Political enemies were killed or jailed; perhaps as many as 200,000 lost their lives in prison or through executions. The political autonomies of Basque and Catalonia were voided. These regions’ culture, language, and identity were suppressed, and a single Spanish national identity was enforced.

After World War II ended, Spain became politically and economically isolated from most of the international community because of General Franco’s association with the defeated fascist regimes of Germany and Italy. But with increasing tensions in the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union, the U.S. government became drawn to Spain’s staunchly anti-communist stance and its strategic location at the western end of the Mediterranean Sea.

In September 1953, Spainand the United Statesentered into a defense agreement known as the Pact of Madrid, where the U.S. government infused large amounts ofmilitary assistance to Spain’sdefense. As a result, Spain’sdiplomatic isolation ended, and the country was admitted to the United Nationsin 1955.

Its economy devastated by the civil war, Spainexperienced phenomenal economic growth during the period from 1959 to 1974(known as the “Spanish Miracle”) when the government passed reforms that openedup the financial and investment sectors. Spain’stotalitarian regime ended with General Franco’s death in 1975; thereafter, thecountry transitioned to a democratic parliamentary monarchy which it is today.

July 5, 2024

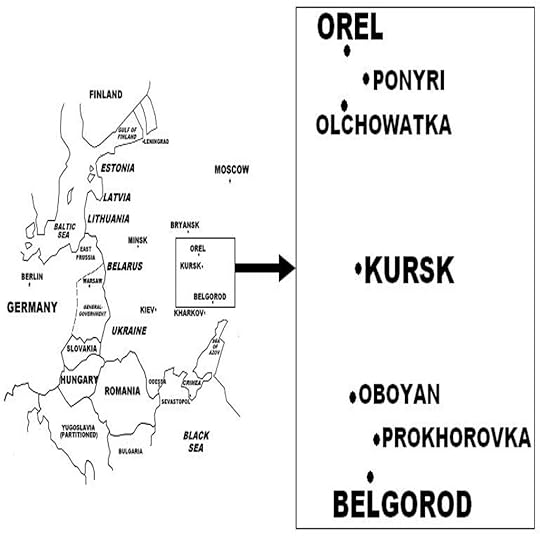

July 5, 1943 – World War II: German and Soviet forces clash at the Battle of Kursk

On July 5, 1943, the German Army launched Operation Citadel,attacking north and south to pinch off Soviet positions at the Kursk salient. Theoffensive made little headway in the face of extensive Soviet defensive lines consistingof minefields, fortifications, artillery fire zones, and anti-tank positionsthat stretched 300 km deep. Further, on July 12, Adolf Hitler ordered that theoffensive be discontinued to transfer German units to southern Italy,where the Western Allies had just opened a new front.

For some time, it was widely believed that the Battle of Kursk, particularly the German-Soviet armoured encounter at Prokhorovka, featured the largest combined number of tanks that was brought into battle. Studies using newly released Soviet archives confer this distinction to an earlier Soviet-German armoured encounter, the Battle of Brody (June 1941), at the start of Operation Barbarossa.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 6 – World War II in Europe)

Preparations On March 10, 1943, as the battle of Kharkov was winding down, General Manstein, head of German Army Group South, set his sights on eliminating a large gap around Kursk that had formed between his forces and those of German Army Group Center. With Hitler issuing Order No. 5 (March 13) authorizing such an operation, General Manstein and General Gunther von Kluge, commander of German Army Group Center, made preparations to immediately attack the Kursk salient. But with strong Soviet concentrations on the northern side of the salient, as well as reinforcements being rushed to the south to stem General Manstein’s northern advance, the proposed joint offensive was suspended. By then also, German forces were exhausted, and the rasputitsa season had set in, preventing further large-scale armored movement.

The Kursksalient was a Soviet protrusion into German-occupied territory, measuring 160miles long from north to south and 100 miles from east to west. Kurskand the surrounding region held no strategic value to either side, but to theGermans (and the Soviets), pinching off the salient would eliminate the dangerto their flanks.

In April 1943, Hitler’s Order No. 6 formalized the attack onthe Kursk salient under Operation Citadel, which consisted of a pincersmovement aimed at trapping five Soviet armies, with the northern pincer ofGerman Army Group Center’s 9th Army thrusting from Orel, and the southernpincer of German Army Group South’s 7th Panzer Army and German Army DetachmentKempf advancing from around Belgorod. The offensive was set for May 3.

In late April 1943, Kluge expressed doubts to Hitler aboutthe feasibility of Operation Citadel, as German air reconnaissance showed thatthe Soviets were constructing strong fortifications along the northern side ofthe salient. As well, General Mansteinwas concerned, as his idea of launching a surprise attack on the unfortifiedsalient could not be achieved anymore. The May 3 launch was not met, and on May 4, Hitler met with GeneralsKluge and Manstein and other senior officers to discuss whether or notOperation Citadel should proceed, or that other options be explored. But as the meeting produced no consensus,Hitler remained committed to the operation, resetting its launch for June 12,1943. With other issues consequentlycoming up, Hitler postponed the launch date to June 20, then to July 3, andfinally to July 5, 1943.

As Operation Citadel was successively pushed back, with thedelays ultimately lasting over two months, it also grew in importance, asHitler saw Kursk as the battle that wouldrestore German superiority in the Eastern Front following the Stalingraddebacle, which continued to weigh heavily on him and the German HighCommand. Like his generals, Hitler wasconcerned with the massive Soviet buildup in the salient, but believed that hisforces would break through, as well as surprise the enemy, using theWehrmacht’s latest armored weapons, the versatile Panther tank, the heavy Tigerbattle tank, and the goliath Elefant (“Elephant”) tank destroyer. Regaining the military initiative with avictory at Kursk also might convince Hitler’sdemoralized Axis partners, Italy,Romania, and Hungary, whose armies were battered at Stalingrad, to reconsider quitting the war.

Hitler’s concerns regarding Kursk were warranted, as the Soviets wereindeed fully concentrating on the region. But unbeknown to Hitler and the German senior staff, Stalin and theSoviet High Command were aware of many details of Operation Citadel, with theinformation being provided to Soviet intelligence by the Lucy spy ring, anetwork of anti-Nazi German officers working clandestinely in cooperation withthe Swiss intelligence bureau. Stalinand a number of senior officers wanted to launch a pre-emptive attack todisrupt the German plans.

However, General Georgy Zhukov, deputy head of the SovietHigh Command and who was instrumental in the Soviet successes in Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad and was therefore highly regarded by Stalin,convinced the latter to adopt a strategic defense against the German attack,and then to launch a counter-offensive after the Wehrmacht was weakened. Under General Zhukov’s direction, the SovietCentral Front and Voronezh Front, which defended the northern and southernsides of the salient respectively, implemented a “defense-in-depth” strategy:using 300,000 civilian laborers, six defensive lines (three main forward andthree secondary rear lines) were constructed on either side of Kursk, the totaldepth reaching over 90 miles. Thesedefensive lines, particularly the main forward lines, were fortified withminefields, wire entanglements, anti-tank obstacles, infantry trenches, dug-inarmored vehicles, and artillery and machinegun emplacements.

A German attack, even if it broke through all six lineswhile facing furious Soviet artillery fire in the minefields in between eachline, would then encounter additional defensive lines by the reserve SovietSteppe Front; by then, the Germans would have advanced through many defensivelayers a distance of 190 miles under continuous Soviet air and armoredcounter-attacks and artillery fire.

The buildup to Kurskalso saw the Soviets making extensive use of military deception, e.g. dummyairfields, camouflaged artillery positions, night movement of troops, falseradio communications, concealed troop concentrations and ammunition stores,spreading rumors in German-held areas, etc. These measures were so effective that the Germans grossly underestimatedSoviet strength at Kursk:at the start of the battle, the Red Army had assembled 1.9 million troops,5,100 tanks, and 25,000 artillery pieces and mortars, while the Germans fielded780,000 troops, 2,900 tanks, and 10,000 artillery pieces and mortars. This great imbalance of forces, as well aslarge numbers of Red Army reserves and extensive Soviet defensive preparations,would be decisive in the outcome of the battle.

BattleTo pre-empt the Germans, on the nightof July 4, 1943, the Red Army launched a massive artillery bombardment alongthe northern and southern zones of the salient, but which caused only lightdamage or disrupt German forces assembling for the attack. Early on April 5, the Wehrmacht opened itsown artillery barrage, and thereafter, German 9th Army in the north and German4th Panzer Army and Army Detachment Kempf (the latter having the strength of aregular field army; so-named after its commander, General Werner Kempf) in thesouth, launched their ground offensives. The German plan was for the northern and southern forces to conduct apincers movement to trap and destroy Soviet forces in the Kursk salient. The Battle of Kursk was on.

July 4, 2024

July 4, 1994 – Rwandan Genocide: Rebels capture the capital Kigali

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 2 Twenty Wars that shaped the Present World)

On July 4, 1994, Kigali fell to the Rwandan Patriotic Front as the Rwandan Army abandoned the city after running low on ammunitions. The Hutu government had vacated Kigali at the start of the siege, moving its headquarters to Gitarama in the east. With the rebels’ capture of Gitarama in mid-June, the government moved its capital to the north, first to Ruhengeri, and later, Gisenyi, both of which fell on July 13 and July 18, respectively.

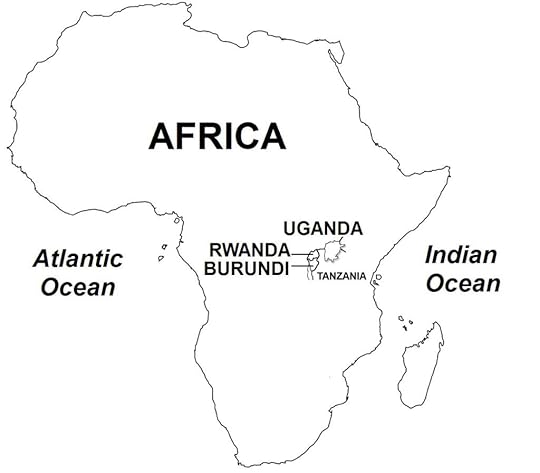

Rwandan Civil War. In April 1994, the Rwandan Genocide was in full swing, with Hutus targeting Tutsis. From their bases in northern Rwanda, Tutsi rebels launched separate offensives aimed at Kibungo in the southeast, Ruhengeri in the north, and Kigali, Rwanda’s capital.

Rwandan Civil War. In April 1994, the Rwandan Genocide was in full swing, with Hutus targeting Tutsis. From their bases in northern Rwanda, Tutsi rebels launched separate offensives aimed at Kibungo in the southeast, Ruhengeri in the north, and Kigali, Rwanda’s capital.On many occasions, the UN called for a ceasefire, but each time, this was rejected by rebel leader Paul Kagame. Then prompting on France’s suggestion, the UN established a security zone in the southwest region of Rwanda in areas that had not yet fallen to the rebels. The UN purposed the security zone to be used as a sanctuary for civilians affected by the war. On July 23, 1994, France led a coalition force (comprising military units from a number of countries) that took control of the security zone. Hundreds of thousands of Hutu refugees and soldiers entered the security zone to escape the ever-widening areas being captured by the rebels. The presence of the French forces deterred the rebels from entering the security zone in pursuit of the Rwandan Army.

The UN mandate on the security zone ended on August 21,forcing the French-led coalition to withdraw completely from Rwanda. The Hutus fled from the security zone, whichwas then occupied by the Tutsi rebels. Shortly thereafter, Kagame brought the whole country under hiscontrol. The Rwandan Civil War was over.

Background Rwanda, a small country in Africa,experienced a long period of ethnic unrest before and after it gained itsindependence in the 1960s. Then in the1990s, this unrest culminated in two events known as the Rwandan Civil War andthe Rwandan Genocide, both of which caused great loss in human lives andmassive destruction of the country.

The conflict revolved around the hostility between Rwanda’s twomain ethnic groups, the majority Hutus, who comprised 85% of the population,and the Tutsis, who made up 14% of the population. The origin of this hostility goes back manycenturies to when a Tutsi monarchy was established in the Hutu-populated landof what is present-day Rwanda. Over time, the Tutsi monarch gaineddomination over the Hutus. The Tutsimonarch also acquired ownership over most of the land, which he divided intovast estates that were overseen by a hierarchy of Tutsi overlords, and workedby Hutu laborers in a feudal-type system. For the most part, however, Tutsis and Hutus lived in harmony. In the course of time, some Hutus becamewealthy, while many ordinary, non-aristocratic Tutsis remained poor.

Rwandan GenocideOn April 6, 1994, President Habyarimina and Burundi’shead of state, Cyprien Ntaryamira, were killed by undetermined assassins whentheir plane was shot down by a rocket-propelled grenade as it was about to landin Kigali. A staunchly anti-Tutsi military government tookover power in Rwanda.Within a few hours and in reprisal for the double assassinations, the newgovernment unleashed the Interahamwe “death squads” to murder Tutsis andmoderate Hutus on sight. Over the nextseveral weeks, in the event known as the “Rwandan Genocide”, large numbers ofcivilians were murdered in Kigaliand throughout the country. No place wassafe; in some instances, even Catholic churches were the scenes of themassacres of thousands of Tutsis where they had taken refuge.

The attackers used clubs, spears, firearms, and grenades,but their main weapon was the machete, with which they had trained extensivelyand which they used to hack away at their victims. At the urging of local officials, Hutu civiliansjoined in the killing frenzy, and turned against their Tutsi neighbors,acquaintances, and even relatives. Inmany cases, the threat of being killed for appearing sympathetic to Tutsisforced many otherwise disinterested Hutus to participate.

The Rwandan Army provided the Interahamwe with a list ofTutsis to be killed, and raised road blocks to prevent any escape. The death toll in the Rwandan Genocide rangesfrom between 800,000 to one million; some 10% of the fatalities were moderateHutus. The genocide lasted for about 100days, from between April 6 to July 15, producing a killing rate of 10,000persons a day. The speed by which it wascarried out makes the Rwandan Genocide the fastest in history. (By comparison, the Holocaust in Europe during World War II, although producing a muchhigher death toll, was carried out over a number of years.)

During the course of the genocide, the UN force in Rwanda wasordered not to intervene by the UN Secretary General. In any case, the UN force was seriouslyundermanned and only lightly armed to stop the widespread violence.

The UN peacekeepers, however, managed to protect thecivilians inside their zone of authority. Shortly after the violence began, foreign diplomats and their staff fromthe various embassies in Kigalifled the country. Other civilianexpatriates were evacuated as well. Theinternational community, including the Western powers, chose not to intervenein the genocide or misread the upsurge in violence as just another combat phasein the civil war.

July 3, 2024

July 3, 1940 – World War II: The British Navy attacks the French fleet in Mers El Kebir

On July 3, 1940, British ships attacked and destroyed the French fleet at Mers El Kebir, in French Algeria. Some 1,300 French sailors were killed and another 350 wounded; 1 battleship was sunk and another 2 damaged; 3 destroyers were damaged and another grounded. British losses were 2 sailors killed and 6 aircraft shot down.

The British attack came after France had signed armistices with Germany and Italy on June 22, 1940. The British feared that the new French state, called Vichy France, would hand over its fleet to Germany or that it would be seized by the German Navy. The British had opened negotiations with French authorities in North Africa to hand over the French fleet, or even continue the war against Germany. But these negotiations failed, prompting the British to launch the attack at Mers El Kebir; French ships docked in British ports were also attacked.

Another French fleet in Alexandria, in Egypt, was blockaded by the British Navy. After difficult negotiations, the French commander allowed his fleet to be disarmed and to remain in port until the end of the war.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Volume 6 – World War II in Europe) Aftermath of the German Invasion of France Despite Germany’s overwhelming military position at the end of hostilities, the armistice negotiations were conducted with consideration of other realities: for Hitler, that the French government and army could very well move to French colonies in North Africa from where they could continue the war; and for the French government, that it wanted to remain in France but only if the Germans did not impose “dishonorable or excessive” terms. Terms that were deemed unacceptable included the following: that all of France would be occupied, that France should surrender its navy, or that France should relinquish its (vast) colonial territories.

Not only did Hitler not impose these terms, in fact, hedesired that France remain a sovereign state for diplomatic and practicalreasons: in the first case, France had ostensibly switched sides in the war,isolating Britain; and in the second case, France, with its large navy, wouldmaintain its global colonial empire, which Germany could not because it did nothave enough ships.

Thus, in the armistice agreement, Francewas allowed to remain a fully sovereign state, with its mainland territory andcolonial possessions intact, with some exceptions: Alsace-Lorraine became partof the Greater German Reich, although not formally annexed into Germany; and Nord and Pas-de-Calais wereattached to Belgium in the“German Military Administration of Belgium and Northern France”. France alsoretained its navy, but which was demobilized and disarmed, as were the otherbranches of the French armed forces.

Because of the continuing hostilities with Britain, as part of the armistice agreement, theGerman Army occupied the northern and western sections of France (some55% of the French mainland), where it imposed military rule. The occupation was intended to be temporaryuntil such time that Germanyhad defeated or had come to terms with Britain, which both the French andGerman governments believed was imminent. The Italian military also occupied a small area in the French Alps. In the rest of France (comprising 45% of theFrench mainland), which was not occupied and thus called zone libre (“freezone”), on July 10, 1940, the French government formed a new polity called the“French State” (French: État français), which dissolved the French ThirdRepublic, and was led by Petain as Chief of State.

The “French State” had its capital at Vichy,some 220 miles south of Paris, and was commonlyknown as “Vichy France”. Officially, VichyFrance retained sovereigntyover all France,but in reality, it exercised little authority in the occupied zones. Vichy France did have full administrativepower in zone libre, and in the ongoing war, it maintained a policy ofneutrality (e.g. it did not join the Axis), and was internationally recognized,and maintained diplomatic relations with the United States, Canada, the SovietUnion, even Britain, and many neutral countries.

The Vichy government imposedauthoritarian rule, with Petain holding broad powers, which was a full turn-aroundand rejection of the liberalism and democratic ideals of the French Third Republic. Using Révolution nationale (“NationalRevolution”) as its official ideology, the Petain regime turned inward-looking(la France seule, or “France alone”),was deeply conservative and traditionalist, and rejected liberal and modernistideas. Traditional culture and religionwere promoted as the means for the regeneration of France. The separation of Church and State wasabolished, with Catholics playing a major role in affairs, the French ThirdRepublic was reviled as morally decadent and causing France’s military defeat,and anti-Semitism and xenophobia predominated, with Jews and other“undesirables”, including immigrants, gypsies, and homosexuals beingpersecuted. Communists and left-wingers,and other radicals were included in this category following the German invasionof the Soviet Union in June 1941. Xenophobia was particularly directed against Britain, with Petain and other leadersexpressing strong antipathy with the British, calling them France’s“hereditary” and lasting enemy.

The Vichy regime waschallenged by General Charles de Gaulle, who in June 1940 in Britain, formeda government-in-exile called Free France, and an army, the Free FrenchForces. De Gaulle criticized Vichy Franceas illegitimate, that it had usurped power from the French Third Republic, and that it wasa puppet state of Nazi Germany. In a BBCbroadcast on June 18, 1940 (the so-called “Appeal of 18 June”; French: Appel du18 juin), he called on the French people to reject the Vichy regime and resist the German occupiers.Initially, de Gaulle received little support in Franceand among expatriate French, who regarded the Petain regime as being theconstitutionally legitimate authority for France.

Despite the armistice agreement’s stipulation thatdeactivated the French naval forces, the British government feared that theFrench fleet would be seized by the Germans who then would use it to invade Britain. Thus, on July 3, 1940, British ships attackedthe French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir (in Algeria),sinking or damaging several French ships, while the French squadron at Alexandria (in Egypt) allowed itself to beinterned by the British fleet.

By October 1940, the Petain regime had began to activelycollaborate in implementing the Nazi government’s Anti-Semitism laws. Using information of the poll registers onthe Jewish population that earlier had been collected by the French police,French authorities and the Gestapo (German secret police), working together orseparately, conducted raids where thousands of Jews (as well as other“undesirables”) were rounded up and confined in internment camps for eventualtransport to concentration and extermination camps in Eastern Europe; manyconcentration camps also were set up in France. Of the 330,000 Jews in France,some 77,000 perished in the Holocaust, a death rate of 25%.

As the armistice agreement also required France to paythe cost of the German occupation, the French became dependent on and subservientto German impositions. French farmproduction and resources were seized by the Germans, resulting in thedeterioration of the French economy and causing severe hardships to the Frenchpeople, who suffered food and fuel shortages or rationing, curfew, andrestricted civil liberties.

The Battle of France resulted in some 1.5 million Frenchsoldiers becoming German prisoners of war. To prevent Vichy France from re-mobilizing these troops, Germanauthorities kept these French soldiers in labor camps in Germany and France,although some 500,000 were later released at various times, and the remainingone million freed by the Allies at the end of World War II.

By 1941, a French resistance movement comprising many smallgroups had emerged, with its memberships increased by the influx of communistsfollowing the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, and forced workevaders following the implementation of Service du Travail Obligatoire(“Obligatory Work Service”) in February 1943. The French resistance soon also made contactwith de Gaulle’s government-in-exile, the British Special Operations Executive(SOE) and the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which sent supplies andagents. The resistance conductedsabotage operations against military-vital targets, provided the Allies withintelligence information, and sheltered and helped escape downed Allied airmen,Jews, and other elements targeted by German and Vichy authorities.

In November 1942, following the Allied invasion of westernNorth Africa, the German military also occupied the territory of Vichy Francein order to safeguard the southern flank. The Italian occupation zone also was expanded. While Franceostensibly continued its sovereignty over its territories, in reality, Germanmilitary authority came into force throughout France,and the Vichygovernment exercised little power. TheGerman occupation of Vichy France also ended the latter’s diplomaticrelations with the United States,Canada,and other Allies, and also with many neutral states.

July 2, 2024

July 2, 1976 – Vietnam War: North and South are reunified at the end of the war

On July 2, 1976, the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) was dissolved, and its people and territory were reunified with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), with the merger giving rise to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam that exists today. The reunified Vietnam came following the fall of the South Vietnamese capital Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War in April 30, 1975.

At the end of the Vietnam War, the Provisional RevolutionaryGovernment (PRG) was tasked to govern South Vietnam preparatory to reunification.The PRG was a South Vietnamese subversive organization that formed in June 1969consisting of a broad coalition of communist, non-communist, anti-imperialist, farmers,workers, and ethnic groups that opposed the current South Vietnamesegovernment. After reunification, the PRG was dissolved.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath of the Vietnam War The war had a profound, long-lasting effect on the United States. Americans were bitterly divided by it, and others became disillusioned with the government. War cost, which totaled some $150 billion ($1 trillion in 2015 value), placed a severe strain on the U.S. economy, leading to budget deficits, a weak dollar, higher inflation, and by the 1970s, an economic recession. Also toward the end of the war, American soldiers in Vietnam suffered from low morale and indiscipline, compounded by racial and social tensions resulting from the civil rights movement in the United States during the late 1960s and also because of widespread recreational drug use among the troops. During 1969-1972 particularly and during the period of American de-escalation and phased troop withdrawal from Vietnam, U.S. soldiers became increasingly unwilling to go to battle, which resulted in the phenomenon known as “fragging”, where soldiers, often using a fragmentation grenade, killed their officers whom they thought were overly zealous and eager for combat action.

Furthermore, some U.S.soldiers returning from Vietnamwere met with hostility, mainly because the war had become extremely unpopularin the United States,and as a result of news coverage of massacres and atrocities committed byAmerican units on Vietnamese civilians. A period of healing and reconciliation eventually occurred, and in 1982,the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was built, a national monument in Washington, D.C.that lists the names of servicemen who were killed or missing in the war.

Following the war, in Vietnamand Indochina, turmoil and conflict continuedto be widespread. After South Vietnam’scollapse, the Viet Cong/NLF’s PRG was installed as the caretakergovernment. But as Hanoide facto held full political and military control, on July 2, 1976, North Vietnam annexed South Vietnam, and the unifiedstate was called the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Some 1-2 million South Vietnamese, largely consisting offormer government officials, military officers, businessmen, religious leaders,and other “counter-revolutionaries”, were sent to re-education camps, whichwere labor camps, where inmates did various kinds of work ranging fromdangerous land mine field clearing, to less perilous construction andagricultural labor, and lived under dire conditions of starvation diets and ahigh incidence of deaths and diseases.

In the years after the war, the Indochina refugee crisisdeveloped, where some three million people, consisting mostly of those targetedby government repression, left their homelands in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos,for permanent settlement in other countries. In Vietnam,some 1-2 million departing refugees used small, decrepit boats to embark onperilous journeys to other Southeast Asian nations. Some 200,000-400,000 of these “boat people”perished at sea, while survivors who eventually reached Malaysia, Indonesia,Philippines, Thailand,and other destinations were sometimes met there with hostility. But with United Nations support, refugeecamps were established in these Southeast Asian countries to house and processthe refugees. Ultimately, some 2,500,000refugees were resettled, mostly in North America and Europe.

The communist revolutions triumphed in Indochina: in April1975 in Vietnam and Cambodia, and in December 1975 in Laos. Because the United States used massive air firepower in the conflicts, North Vietnam, eastern Laos, and eastern Cambodia were heavily bombed. U.S.planes dropped nearly 8 million tons of bombs (twice the amount the United States dropped in World War II), and Indochina became the most heavily bombed area inhistory. Some 30% of the 270 millionso-called cluster bombs dropped did not explode, and since the end of the war,they continue to pose a grave danger to the local population, particularly inthe countryside. Unexploded ordnance(UXO) has killed some 50,000 people in Laosalone, and hundreds more in Indochina arekilled or maimed each year.

The aerial spraying operations of the U.S. military, carriedout using several types of herbicides but most commonly with Agent Orange(which contained the highly toxic chemical, dioxin), have had a direct impacton Vietnam. Some 400,000 were directlykilled or maimed, and in the following years, a segment of the population thatwere exposed to the chemicals suffer from a variety of health problems,including cancers, birth defects, genetic and mental diseases, etc.

Some 20 million gallons of herbicides were sprayed on 20,000km2 of forests, or 20% of Vietnam’stotal forested area, which destroyed trees, hastened erosion, and upset theecological balance, food chain, and other environmental parameters.

Following the Vietnam War, Indochinacontinued to experience severe turmoil. In December 1978, after a period of border battles and cross-borderraids, Vietnam launched afull-scale invasion of Cambodia(then known as Kampuchea)and within two weeks, overwhelmed the country and overthrew the communist PolPot regime. Then in February 1979, inreprisal for Vietnam’sinvasion of its Kampuchean ally, Chinalaunched a large-scale offensive into the northern regions of Vietnam, but after one month ofbitter fighting, the Chinese forces withdrew. Regional instability would persist into the 1990s.

July 1, 2024

July 1, 1942 – World War II: The start of the First Battle of El Alamein

On July 1, 1942, the First Battle of El Alamein began pitting the Axis (comprising German and Italian forces) against the Allies (comprising units from Britain, British India, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand). The nearly month-long battle (July 1-27, 1942) ended inconclusively, but was a strategic setback for the Axis forces as their planned further advance into Egypt (Alexandria, Cairo, and the Suez Canal) was stopped.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century (Volume 6) – World War II in Europe)

The Axis in the African Theatre of World War II In East Africa, the Italian Army achieved success initially, launching offensives from Italian territories of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland and driving away the British from British Somaliland, and seizing some border regions in British-controlled Sudan and Kenya. At this stage of World War II, Britain’s overseas possessions were extremely vulnerable, as British efforts were diverted to the homeland to confront the ongoing German air offensives (Battle of Britain, separate article). But with the Luftwaffe scaling down operations in Britain as 1941 progressed, the British soon counter-attacked in East Africa, throwing back the Italians and regaining lost territory, and then capturing Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland, and forcing the surrender of the remaining Italian forces in East Africa.

In North Africa, which was a major battleground in World WarII, the Italian Army also achieved some success initially, launching from Libya and advancing 62 miles (100 km) intoBritish-administered Egyptin September 1940, while taking advantage of the desperate situation of theBritish in the ongoing Battle of Britain. In December 1940, the British counter-attacked and threw back the muchlarger Italian forces into Libya,taking some 130,000 Italian prisoners and advancing 500 miles (800 km) to ElAgheila. Now poised to expel the ItalianArmy from North Africa altogether, the British were forced to halt theiroffensive to transfer some of their troops to Greece, to help contain a newItalian offensive there.

The pause allowed Hitler to come to the aid of hisbeleaguered ally Mussolini, in February 1941, sending the first units of theGerman Afrika Korps led by General Erwin Rommel, to fight alongside the Italianforces, which also were bolstered by reinforcements arriving from Europe. A see-sawbattle ensued for over a year, with one side pushing the other hundreds ofmiles through the desert, and then the other side launching a counter-offensivethat threw back the other and penetrating deep into enemy territory.

Then in October-November 1942, the British 8th Armydecisively defeated the German-Italian force at the Second Battle of ElAlamein, forcing the Axis to retreat 1,600 miles (2,600 km) to theLibya-Tunisia border.

Also in November 1942, an American-British force landed at Morocco and Algeria,which were administered by Vichy France. After a short period of fighting, theAmericans and British succeeded in persuading French forces there to switchsides to the Allies. American-British-French forces from the west and the British 8th Armyfrom the east then attacked and encircled the German-Italian forces in Tunisia, and in May 1943, expelled the Axis fromNorth Africa. As a result, Italylost all its African territories.

June 30, 2024

June 30, 1936 – Interwar period: Ethiopia appeals to the League of Nations against the Italian invasion

On June 30, 1936, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie addressed the League of Nations appealing for aid against the Italian invasion of his country. The League of Nations condemned the Italian invasion, but imposed only partial and ineffective economic sanctions on Italy.

In October 1935, the Italian Army invaded independent Ethiopia, conquering the African nation by May 1936 in a brutal campaign that included the Italians using poison gas on both soldiers and civilians. In the aftermath, Italy annexed Ethiopia into the newly formed Italian East Africa, which included Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. Italy also controlled Libya in North Africa as a colony.

(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 6 – World War II in Europe)

Mussolini and His Quest for an Italian Empire In the midst of political and social unrest in October 1922, Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party came to power in Italy, with Mussolini being appointed as Prime Minister by Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III. Mussolini, who was popularly called “Il Duce” (“The Leader”), launched major infrastructure and social programs that made him extremely popular among his people. By 1925-1927, the Fascist Party was the only legal political party, the Italian legislature had been abolished, and Mussolini wielded nearly absolute power, with his government a virtual dictatorship.

By the late 1920s through the 1930s, Mussolini pursued anovertly expansionist foreign policy. Hestressed the need for Italian domination of the Mediterranean region andterritorial acquisitions, including direct control of the Balkan states of Yugoslavia, Greece,Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania,and a sphere of influence in Austriaand Hungary, and colonies inNorth Africa. Mussolini envisioned a modern Italian Empire in the likeness of theancient Roman Empire. He explained that his empire would stretchfrom the “Strait of Gibraltar [western tip of the Mediterranean Sea] tothe Strait of Hormuz [in modern-day Iranand the Arabian Peninsula] (Figure 20)”. Although not openly stated, to achieve thisgoal, Italy would need toovercome British and French naval domination of the Mediterranean Sea.

Furthermore, in the aftermath of World War I, a strongsentiment regarding the so-called “mutilated victory” pervaded among manyItalians about what they believed was their country’s unacceptably smallterritorial gains in the war, a sentiment that was exploited by the Fascistgovernment. Mussolini saw his empire asfulfilling the Italian aspiration for “spazio vitale” (“vital space”), wherethe acquired territories would be settled by Italian colonists to ease theoverpopulation in the homeland. Mussolini’s government actively promoted programs that encouraged largefamily sizes and higher birth rates.

Mussolini also spoke disparagingly about Italy’sgeographical location in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about how it was“imprisoned” by islands and territories controlled by other foreign powers(i.e. France and Britain), and that his new empire would include territoriesthat would allow Italy direct access to the Atlantic Ocean in the west and theIndian Ocean in the east.

In October 1935, the Italian Army invaded independent Ethiopia,conquering the African nation by May 1936 in a brutal campaign that includedthe Italians using poison gas on civilians and soldiers alike. Italythen annexed Ethiopia intothe newly formed Italian East Africa, which included Eritreaand Italian Somaliland. Italyalso controlled Libya in North Africa as a colony.

The aftermath of Italy’sconquest of Ethiopia saw arapprochement in Italian-Nazi German relations arising from Hitler’s support ofItaly’s invasion of Ethiopia. In turn, Mussolini dropped his opposition to Germany’s annexation of Austria. Throughout the 1920s-1930s, the majorEuropean powers Britain, France, Italy, the Soviet Union and Germany, engagedin a power struggle and formed various alliances and counter-alliances amongthemselves, with each power hoping to gain some advantage in what was seen asan inevitable war. In this powerstruggle, Italystraddled the middle and believed that in a future conflict, its weight wouldtip the scales for victory in its chosen side.

In the end, it was Italy’sties with Germanythat prospered; both countries also shared a common political ideology. In the Spanish Civil War (July 1936-April1939), Italy and Germany supported the rebel Nationalist forcesof General Francisco Franco, who emerged victorious and took over power in Spain. In October 1936, Italyand Germanyformed an alliance called the Rome-Berlin Axis. Then in 1937, Italyjoined the Anti-Comintern Pact, which had been signed by Germany and Japan in November 1936. In April 1939, Italymoved one step closer to forming an empire by invading Albania,seizing control of the Balkan nation within a few days. In May 1939, Mussolini and Hitler formed amilitary alliance, the Pact of Steel. Two months earlier (March 1939), Germanycompleted the dissolution and partial annexation of Czechoslovakia. The alliance between Germany and Italy,together with Japan,reached its height in September 1940, with the signing of the Tripartite Pact,and these countries came to be known as the Axis Powers.

On September 1, 1939 World War II broke out when Germany attacked Poland,which immediately embroiled the major Western powers, France and Britain,and by September 16 the Soviet Union as well (as a result of a non-aggressionpact with Germany, but notas an enemy of France and Britain). Italydid not enter the war as yet, since despite Mussolini’s frequent blustering ofhaving military strength capable of taking on the other great powers, Italy in factwas unprepared for a major European war.

Italy wasstill mainly an agricultural society, and industrial production forwar-convertible commodities amounted to just 15% that of Britain and France. As well, Italian capacity for vital itemssuch as coal, crude oil, iron ore, and steel lagged far behind the otherwestern powers. In military capability,Italian tanks, artillery, and aircraft were inferior and mostly obsolete by thestart of World War II, although the large Italian Navy was ably powerful andpossessed several modern battleships. Cognizant of these deficiencies, Mussolini placed great efforts tobuilding up Italian military strength, and by 1939, some 40% of the nationalbudget was allocated to the armed forces. Even so, Italian military planners had projected that its forces wouldnot be fully prepared for war until 1943, and therefore the sudden start ofWorld War II came as a shock to Mussolini and the Italian High Command.

In April-June 1940, Germanyachieved a succession of overwhelming conquests of Denmark,Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium,Luxembourg, and France. As Franceverged on defeat and with Britainisolated and facing possible invasion, Mussolini decided that the war wasover. In an unabashed display ofopportunism, on June 10, 1940, he declared war on Franceand Britain, bringing Italy into World War II on the side of Germany, andstating, “I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peaceconference as a man who has fought”.

June 29, 2024

June 29, 1950 – Korean War: The U.S. Navy blockades the Korean coast

On June 29, 1950, United States President Harry S. Truman ordereda naval blockade of the Korean coastline following the start of the Korean War.At the same time, he authorized the deployment of U.S.troops to assist the beleaguered South Korean-American forces defending South Korea.The U.S. Air Force was also instructed to launch bombing raids on military targetsin North Korea.

North Korealaunched its invasion of South Korea four days earlier, June 25, and rapidlygained territory, pushing back the small South Korean-American defenders. TheUnited Nations Security Council, upon the request of the United States, passed a resolution urging UNmember states to come to the aid of South Korea.

Some key battle sites during the Korean War

Some key battle sites during the Korean War(Excerpts taken from Wars of the 20th Century: Volume 5 – Twenty Wars in Asia)

Aftermath of the Korean War An armistice was signed on July 19, 1953. Eight days later, July 27, representatives of the UN Command, North Korean Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army signed the Korean Armistice Agreement, which ended the war. A ceasefire came into effect 12 hours after the agreement was signed. The Korean War was over.

War casualties included: UN forces – 450,000 soldierskilled, including over 400,000 South Korean and 33,000 American soldiers; NorthKorean and Chinese forces – 1 to 2 million soldiers killed (which includedChairman Mao Zedong’s son, Mao Anying). Civilian casualties were 2 million for South Korea and 3 million for North Korea. Also killed were over 600,000 North Koreanrefugees who had moved to South Korea. Both the North Korean and South Korean governments and their forcesconducted large-scale massacres on civilians whom they suspected to besupporting their ideological rivals. In South Korea,during the early stages of the war, government forces and right-wing militiasexecuted some 100,000 suspected communists in several massacres. North Korean forces, during their occupationof South Korea,also massacred some 500,000 civilians, mainly “counter-revolutionaries”(politicians, businessmen, clerics, academics, etc.) as well as civilians whorefused to join the North Korean Army.

Under the armistice agreement, the frontline at the time ofthe ceasefire became the armistice line, which extended from coast to coastsome 40 miles north of the 38th parallel in the east, to 20 miles south of the38th parallel in the west, or a net territorial loss of 1,500 square miles toNorth Korea. Three days after theagreement was signed, both sides withdrew to a distance of two kilometers fromthe ceasefire line, thus creating a four-kilometer demilitarized zone (DMZ)between the opposing forces.

The armistice agreement also stipulated the repatriation ofPOWs, a major point of contention during the talks, where both partiescompromised and agreed to the formation of an independent body, the NeutralNations Repatriation Commission (NNRC), to implement the exchange ofprisoners. The NNRC, chaired by GeneralK.S. Thimayya from India, subsequently launched Operation Big Switch, where inAugust-December 1953, some 70,000 North Korean and 5,500 Chinese POWs, and12,700 UN POWs (including 7,800 South Koreans, 3,600 Americans, and 900British), were repatriated. Some 22,000Chinese/North Korean POWs refused to be repatriated – the 14,000 Chineseprisoners who refused repatriation eventually moved to the Republic of China (Taiwan),where they were given civilian status. Much to the astonishment of U.S. and British authorities, 21 Americanand 1 British (together with 325 South Korean) POWs also refused to berepatriated, and chose to move to China. All POWs on both sides who refused to be repatriated were given 90 daysto change their minds, as required under the armistice agreement.

The armistice line was conceived only as a separation offorces, and not as an international border between the two Korean states. The Korean Armistice Agreement called on thetwo rival Korean governments to negotiate a peaceful resolution to reunify the Korean Peninsula. In the international Geneva Conference heldin April-July 1954, which aimed to achieve a political settlement to the recentwar in Korea (as well as in Indochina, see First Indochina War, separatearticle), North Korea and South Korea, backed by their major power sponsors,each proposed a political settlement, but which was unacceptable to the otherside. As a result, by the end of the GenevaConference on June 15, 1953, no resolution was adopted, leaving the Koreanissue unresolved.

Since then, the KoreanPeninsula has remained divided alongthe 1953 armistice line, with the 248-kilometer long DMZ, which was originallymeant to be a military buffer zone, becoming the de facto border between North Korea and South Korea. No peace treaty was signed, with thearmistice agreement being a ceasefire only. Thus, a state of war officially continues to exist between the two Koreas. Also as stipulated by the Korean ArmisticeAgreement, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) was established,comprising contingents from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Sweden, and Switzerland,tasked with ensuring that no new foreign military personnel and weapons arebrought into Korea.

Because of the constant state of high tension between thetwo Korean states, the DMZ has since remained heavily defended and is the mostmilitarily fortified place on Earth. Situated at the armistice line in Panmunjom is the Joint Security Area,a conference center where representatives from the two Koreas hold negotiationsperiodically. Since the end of theKorean War, there exists the constant threat of a new war, which is exacerbatedby the many incidents initiated by North Koreaagainst South Korea. Some of these incidents include: thehijacking by a North Korean agent of a South Korean commercial airliner inDecember 1969; the North Korean abductions of South Korean civilians; thefailed assassination attempt by North Korean commandos of South KoreanPresident Park Chung-hee in January 1968; the sinking of a South Korean navalvessel, the ROKS Cheonon, in March 2010, which the South Korean governmentblamed was caused by a torpedo fired by a North Korean submarine (North Koreadenied any involvement), and the discovery of a number of underground tunnelsalong the DMZ which South Korea has said were built by North Korea to be usedas an invasion route to the south.

Furthermore, in October 2006, North Korea announced that it haddetonated its first nuclear bomb, and has since stated that it possessesnuclear weapons. With North Korea aggressively pursuingits nuclear weapons capability, as evidenced by a number of nuclear tests beingcarried out over the years, the peninsular crisis has threatened to expand toregional and even global dimensions. Western observers also believe that North Korea has since beendeveloping chemical and biological weapons.

North Korea and South Korea Sincethe end of the war, the two Koreashave pursued totally divergent paths. North Korea,a Marxist state, implemented a centrally planned policy, nationalizedindustries, lands, and properties, and collectivized agriculture. During the Japanese occupation of the Korean Peninsula,industrialization (and thus also wealth and power) was concentrated in thenorth. Following the Korean War, North Korea focused on heavy industrialization,particularly power-generating, mineral, and chemical industries, which washelped greatly by large technical and financial assistance from the SovietUnion, China,and other Eastern Bloc countries. It wasalso determined to achieve juche (self-reliance). Simultaneously, North Korea funneled a large shareof its national budget to building a large Army. To fund both its large industrial andmilitary programs, the government borrowed heavily from foreign sources. But after the 1973 global oil crisis, theprice of minerals fell in the world market, negatively affecting North Koreawhich was unable to pay its large foreign debt. By the mid-1980s, it failed to meet most of its debt repaymentobligations, and defaulted.

By the late 1980s, socialism was waning across eastern andcentral Europe, with Eastern Bloc countriesshedding off Marxism-Leninism and centrally planned economies, and adoptingWestern-style democracy and a free market system. In December 1991, the Soviet Union disintegrated. North Korea,suddenly without Soviet financial support, went into an economic freefall. Also in the 1990s, widespread famine in North Koreacaused by various factors, including failed government policies, massiveflooding in 1995-1996, a drought in 1997, and the loss of Soviet support, ledto mass starvation. The number of deathsfrom the famine is estimated at between 500,000 and 2 million people, even upto 3 million. The internationalcommunity responded to the calamity, and North Korea received food and other humanitarian aid from theUN, China, South Korea, the United States, and othercountries. At present, North Korea, when measured in termsof its Gross Domestic Product (GDP), ranks among the poorest and leastdeveloped countries in the world.

By contrast, South Korea, which pursued Western-style democracyand a free market economy, initially suffered from severe political, social,and economic difficulties in the years following the Korean War. The country, which traditionally had animpoverished agricultural economy, was nearly exclusively dependent on U.S.financial aid (up to 90%). In October1953, South Korea and the United Statessigned a Mutual Defense Treaty.

In May 1961, General Park Chung-hee came to power in South Koreathrough a military coup. Soon becomingpresident, Park began the dramatic economic transformation of South Korea. Within a few decades, the country had becomea regional and global economic powerhouse, its rapid growth being called the“Miracle on the Han River” (referring to the Han River, which flows through Seoul).

Because of the prevailing unstable security climate, President Park imposed authoritarian rule and aone-party state system. His regimesuppressed political opposition, censored the press, and committed grave humanrights violations. But at the same time,his government initiated large-scale modernization and export-centeredindustrialization. Succeeding nationaladministrations (after President Park was assassinated in1979) have continued the country’s economic growth. By the 1990s, South Korea had become one of Asia’sbusiness and commercial centers, boasting a highly developed economy. South Koreahas since become the world’s 12th large economy, with a GDP that is nearlyforty times greater than that of North Korea.