Paul E. Fallon's Blog, page 18

March 30, 2022

Civilization: Chris Rock and Will Smith

A civilized person is one “…with inborn instincts inhibited.”

That phrase stopped me short, even though it was embedded—mid-paragraph, page two—in Peter Schjeldahl’s review of “As They Saw It: Artists Witnessing War,” the current exhibit at The Clark (The New Yorker, March 22, 2022).

I like to think of civilization as an unalloyed, if imperfect, good. The accumulation of human potential and achievement over time, evolving ever onward towards equity and light. I never considered that the fundamental building block of civilization—the civilized person—could be defined by how well we inhibit instinct.

Yet, as a child, I grew up on the myth of the American West and therefore equate ‘real men’ with wild, lawless, open space. As an architect, I witnessed the testosterone throb of Bosses who thrive in chaotic Haiti, and the countervailing deference every worker in China displays. These international experiences helped me appreciate Haitian culture even as I recognize it as so fundamentally different than our own that direct comparison is useless. Meanwhile, I understand how China’s culture of conformity is the fuel of its economic juggernaut.

While mulling the tradeoffs between the benefits civilization provides against the constraints each individual must accommodate for a supposed greater good, I considered several current paradoxes, seeking a keen example. Perhaps, how asserting the right to participate in society unvaccinated and unmasked compromises others’ health? Or how people of certain identities demand equal rights which others (who may not understand or even recognize those identities) see as special treatment? Maybe, how regulating the way gender/sexuality can be taught in public schools protects (coddles?) some innocents at the expense of eliminating viable visions of adulthood for those few students for whom it is their healthy path?

But then Will Smith slapped Chris Rock on national television at the Oscars; and shortly thereafter the audience gave the perpetrator a standing ovation. If ever there is an example of inborn instincts unleashed in a forum pretending to be civilized, this is it.

First, consider Chris Rock. Why does the Academy Awards keep inviting him back? His first outing as host, in 2005, got mixed to poor reviews by mainstream media and was resoundingly panned in-house. His riffs twittered between mean-spirited and raw. His spoof highlighting what movie-goers actually see versus what’s nominated exposed an uncomfortable Hollywood truth. His insistent jabbering at Jude Law for showing up in virtually every movie that year received a direct rebut, on stage, from the ever-dour Sean Penn. Yet, the Academy invited him back again in 2016: the year of #OscarSoWhite. That must have been quite a party, though by 2016 I had stopped watching the Oscars. Still, The Academy invited him back again. Why? Because Hollywood endures insults better than crashing ratings, and Chris Rock is a better audience draw than some of the movies celebrated.

I watched the first hour of this year’s show: about as much pomp and makeup and exposed cleavage and limousine liberal-speak I can stomach. I witnessed Will Smith’s prominent seat, since he was a shoo-in for Oscar glory, with his beautiful wife sitting beside. I noticed that Jada was bald, and gave it no more thought than her sumptuous gown. Everybody’s gotta have a look. Chemotherapy? Alopecia? Fashion? Who cares? Among our inalienable rights, there must be the right to be bald.

It is not, however, Jada Pinkett Smith’s inalienable right to sit front and center at the Oscar’s with irreverent Christ Rock at the mic, and escape whatever wrath he inflicts. Chris Rock isn’t invited to the party to be nice, and Jada Pinkett Smith is a public person. Whatever one thinks of the GI-Jane joke, it was classic Chris Rock, and it wasn’t libel.

Enter Will Smith, storming up center stage and slapping Chris Rock. So much for inhibiting instincts. Fisticuffs has a long-standing among men of grit protecting their women-folk. But on stage at the Dolby Theater, in tuxedoes, in front of the peers about to give him a little golden man, before however many dwindling numbers of television viewers? Welcome to civilization removing its gloves.

Will returned to his seat and cursed and cursed. What the video views I’ve watched don’t show is: Will consoling his wife. Defending the purity of the little woman has always been more about the men than the supposedly injured party, anyway.

Will returns later to claim his statue. Aligns himself with his character, King Richard. Talks of defending his family. Cries. The audience gives him a standing ovation. The world heaves a kind of chest-thumping ‘huzzah’ for the strong man. Even left-leaning Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley tweets, “#Alopecia nation stand up! Thank you #WillSmith. Shout out to all the husbands who defend their wives living with alopecia in the face of daily ignorance & insults.”

The show ends and the crowd parties hard. The next morning everyone wakes up. The spirit of unleashed instinct yields to the demands of civilization. Will Smith issues a formal apology. Others call for Chris Rock to do so. The Academy considers withdrawing Will Smith’s Oscar. Representative Pressley’s tweet disappears. A tiny few clamor to address the obvious: a crime has been committed, and documented pretty well. Where are the charges? The arrest?

In my fantasy, Will Smith is arraigned, convicted, and delivered a special sentence: to play Serf Richard, in the flesh, picking crops among migrant workers, hanging out with hood gangs, addressing meetings in union halls, counseling Silicon Valley tech bros on how easily the façade of civilization can fold when we fail to inhibit the toxic masculinity coursing through our inborn instincts.

The Oscar slap is an important moment for crystallizing the chaos of America today; a civilization in retreat as more and more of us refuse to inhibit our innate instincts. As for next year’s Oscar’s? I might not even tune in for an hour. Just go straight to WWF for a dose of more honest violence.

March 23, 2022

How Do You KIVA?

During my time in Haiti I witnessed the benefits of micro-lending first hand. The idea of providing low- or no-interest loans directly to small entrepreneurs appeals at many levels. It’s a direct person-to-person connection that sidesteps much of the bureaucracy of institutional philanthropy, and it fosters small-scale initiatives that are simultaneously rewarding, and useful.

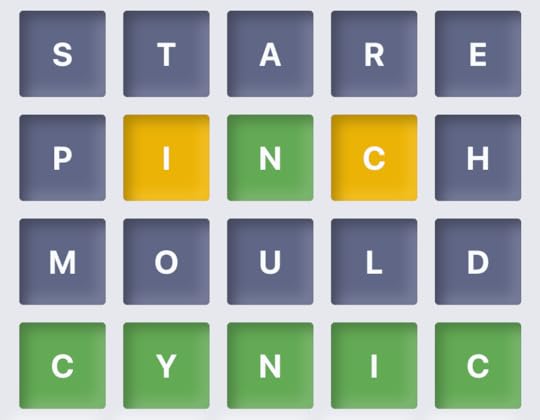

I plunked a hundred dollars into a Kiva.org account over a decade ago, sifted through a range of fledging entrepreneurs, and designated $25 each to four different endeavors. Each time a portion of a loan gets repaid, I designate to a new endeavor. Today, my initial $100 has been lent and repaid eight times over. A very good return on investment.

I’ve also realized that I gravitate toward a particular loan-seeker profile: a person wanting to start or expand some kind of construction. This makes obvious sense for an architect, yet also appeals to my penchant for KIVA loans with a business focus. I don’t have a gender or geographic focus: I lend to women and men all over the world. I shy away from folks wanting money to build their own house, because, even though everyone deserves a house, I don’t see how it generates cash flow for repayment. And I don’t lend to people in retail. Retail is just not my thing.

Last Christmas I gave everyone on my (admittedly small) gift list a $100 KIVA gift card. Recently, I checked in with each of them and asked how they allocated their loans. The responses I received made me appreciate the infinite customization KIVA offers micro lenders.

I was not surprised by my boyfriend Dave, a gentleman farmer, distributed his loans for agricultural purposes. Or that my daughter, a former Peace Corps volunteer in Cambodia, selected businesses in Southeast Asia. But why did my son plunk his full amount on a woman in the Solomon Island to buy a piglet? While most KIVA loans include an aggregate of small amounts from multiple donors, he looked specifically for folks seeking $100 exactly, and fully funded one person’s dream. KIVA loans can be seriously, or serendipitously applied. One of my recipients—who shall remain nameless—admitted to lending money only to gorgeous men from the Middle East. Clearly, KIVA offers something for everyone.

KIVA has a four-star rating on Charity Navigator, 94 out of 100 possible points. That’s not perfect, but for me KIVA includes a worthy fun-factor: exploring potential borrowers and guessing how this loan might change their life. Not everyone will enjoy this: one of the people I gifted hasn’t used their card, thus reminding me of the hazards of gifts that require recipient involvement. No matter, if the card goes unused, the money will revert to KIVA administration: it must take some money to collect a world-wide array of aspirants. And worthy aspirants they are: KIVA’s repayment rate is very high; the default rate on my donations is less than 2%, ensuring a constant cycle of repayments to redirect again and again.

So if you are inclined to make a macro-impact on the life of a person you’ll never meet, consider buying a Kiva card. Better yet, give them out to the people you love, and let everyone KIVA in the way they like best.

My current roster of borrowers

My current roster of borrowers

March 16, 2022

What’s That Got to Do with the Price of Gas?

I got a text from a friend last week: “Paid $4.09 per gallon today. A 30-cent increase from my last fill-up.”

I wasn’t sure what to make of the message. My friend knows I don’t own a car; the price of gas is immaterial in my life. Yet even I understand that pump price is the immediate barometer of our national psyche. As gas prices spike, our collective mood plummets.

The price of gas, at any given moment, is universally known down to the fractional tenth of a cent. It’s posted along roadsides in big, easily changed numbers. It towers over freeway interchanges. And it fluctuates in irrational yet immediate relation to demand, supply, and the news cycle.

Tankers queue, unloaded, outside the Port of Long Beach, and the price of liquid cisterned beneath pavement in Waltham, Massachusetts automatically shoots up. Shut off imports from Russia and the value of crude flowing through New Jersey refineries skyrockets.

The spontaneous correlation between the price of gas and perceived threats to our way of life is not new. Sixty years ago, in 1962, I recall my father dismissing a news report about Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. “What’s that got to do with the price of gas?” His subtext was clear. Science, environmentalism, harmony with nature. That’s all fine, so long as it doesn’t affect me. One iota.

The inverse relationship between our national well-being and the price of a slippery substance that we never actually see makes perfect sense in a nation enthralled with the twin idylls of constant movement and individual independence. Despite what Dunkin’ proclaims, American runs on gasoline, and the cheaper it is, the faster, farther we run.

Today, a trifecta of challenges is driving up the price of gas with record speed: supply chain issues as production awakens from the pandemic; overheated demand due to that same sad pandemic; and the brutal war in Ukraine. The number of media reports angsting over gas prices appears exponentially proportional to the number of fingers we can wag at the problem. My favorite recent headline: “Is $5 per Gallon Gas Worth the Price of Democracy?” That’s how literal we draw the connection between the price of gas and…pretty much anything we value.

Most prudent analyses of human society indicate that burning gasoline is the primary contributor to making our planet warmer, thus less hospitable to humans; that our short-term actions are undermining our long-term survival. We know, intellectually, that we could improve the quality of our planet by using less gas; and Capitalism 101 teaches us that a sure-fire way to decrease demand is to increase price. But the gap between awareness and action since Rachel Carson’s clarion call and today only gets wider. We say we want a fresh, green earth. But our actions betray that what we really want is to be able to drive, in private vehicles, wherever we want, whenever we want.

We are willing to pay handsomely for this privilege, in both time and money. The average American spends over an hour a day commuting, and 20% of their annual income on transportation. Me? A fraction of that. Yet I confess I must be a genetically mutant American, as my DNA simply lacks the love-of-automobile gene. I always preferred the lethargic ease of Ferdinand the Bull rather than racing frantic like Wiley E. Coyote.

My response to my friend’s text was as inadequate as it was expected. “I love you guys, but you’re probably not surprised I don’t have much empathy for the price of gas. We need to use a lot less of it unless we’re gonna burn this planet up.” The moment I hit ‘Send’ I realized how insufficient.

I may choose to operate differently from my fellow citizens, but I cannot dismiss the reality of their lives. Despite our kneejerk despair, the price of gas does have a direct effect on most Americans; and even if we wanted to rearrange our lives to be less auto-dependent, we can’t do it anytime soon. We have spent the last hundred years building a nation of suburbs and freeways that preferences easy, long-distance driving over any other mode of travel. It would take years of collective effort to restructure the United States from a nation of automobiles to one of trains and buses, bicycle and pedestrians. Yet I see no evidence that we even want to make such change.

Five dollar per gallon gas is a fact in the here and now. The fate of democracy—or of the earth—is too abstract to draw a reasoned comparison. And so we will complain. But we will also pony up and keep driving. Because we are creatures of habit who have built a world that offers no other option.

I have little faith in human ability to better balance the long-term consequences of short-term action. But I have tremendous faith in humanity’s ability to react to crisis. And if there’s anything I know for certain: over the next few decades, we’ve got a lot of crises coming down the pike.

So I hope that my friend accepts my response to his plight as honest rather than flippant. I’ve crafted a life immune to the fluctuating price of gas, yet I know that price hikes have real consequences for many, many Americans. I also understand that the price of gas is our totem for the mess we’ve made of our world. The higher it climbs, the deeper out despair.

March 9, 2022

My Day in Court

On June 8, 2021, more than ten months after State Trooper Stanley stopped me along Huron Ave and ordered me to stop painting names of unarmed Blacks killed on the guardrail where we held our nightly BLM vigil, I received ‘Notice of Magistrate’s Hearing on Complaint by the Massachusetts State Police against Paul E Fallon.’ Malicious Destruction of Property; estimated damage $1200; hearing date: 9/22/2021.

After I read the legalese. And my hands stopped shaking. And I resolved myself to several nights and days of confused anxiety. I shared a copy with Peter Gately, a fellow kneeler at our vigil, who is also an attorney.

“I can’t believe the State Police are making a fuss about this. Surely, this will go away.” I said with the intonation of a question.

“Most likely, if you want it to.” Peter replied.

“Why wouldn’t I want it to go away?”

“Because this is harassment. You might want to take a stand.” Peter is a mostly retired attorney with a failing body and a brilliant mind. “Declare you were exercising free speech; refuse to admit any wrong.” He offered to represent me, pro bono. His eyes glistened at the prospect.

“Any chance I would go to jail for this?” Peter’s laugh alleviated my doubt. So I figured, worst case, I’d be out $1200. A worthy gamble for an opportunity to gum up the State Police, a notoriously scandalous organization.

I attended the hearing on 9/22. Trooper Stanley made a statement. I declined. The hearing officer offered to settle the charge if I did not pursue similar behavior for a year. I declined. She simultaneously sweetened the deal to six months, while warning me that the penalty amount could exceed $1200. I could tell she wanted this to simply go away. Yet again, I declined. The court agent acknowledged my right to trial.

I was arraigned in December. The pre-trial hearing was set for February 15, 2022. The first public hearing of the case.

Peter laid out the legal argument thus. Back in the 1960’s, protestors of the Vietnam War argued, successfully, that the only way they could exercise their free speech was through civil disobedience, since all of the mechanisms of law and governance were allied with the war. The same logic could be applied to protesting the actions of police against Blacks in 2020.

Our tactics were threefold. First, Peter would contact the City Solicitor and request that the city request the charge dismissed, since my painting of names occurred on city property and Black Lives Matter slogans festooned public spaces all across Cambridge. Second, he would encourage the District Attorney to invoke Nolle Prosequi, a legal position that declares the prosecution will not prosecute. In Nolle Prosequi, the judge has no say, the case is fully dismissed. The third leg—my job—was to contact elected representatives to weigh in on my behalf, enlist supporters to show up at court, and notify any media who might be interested.

When called to account, people—and politicians—show their true colors. The City Solicitor’s office dismissed Peter’s inquiries. So too the city councilors remained mute, including the one who’d sent me an initial note of support. Fortunately, my superb State Representative, Steven Owens, sent a meaningful letter of support to the DA’s office. Folks from SURJ Boston spun an elaborate Signal thread of how my case needed to be coordinated with other efforts, and therefore wound up doing nothing. No one from the media followed up, but a half dozen fellow vigil-kneelers arrived at court.

The Assistant DA for the case took Peter’s calls, and after coordinating with others, arrived at the hearing with a document declaring Nolle Prosequi. My day in court lasted less than a minute.

Afterwards, over coffee, I wondered what value the entire exercise delivered. Peter was philosophical as ever. “We can’t know whose mind we might have bent in this exercise. Did anyone at the city rethink their perspective? Did our fresh ADA come to see things differently? It is unlikely that Trooper Stanley will hear about the outcome. But if he does this again and again, eventually, he’ll be disciplined to allow citizens to express themselves.

“You should also realize you took a bigger gamble than you thought. I never actually said you couldn’t go to jail; I just figured it was wildly improbable. A much larger fine, even jail time, were possibilities, however remote.

“One last thing you might want to think about,” Peter added, “whether you want to have this expunged from your record.”

“My badge of civil disobedience?” I replied. “No way.”

March 2, 2022

Police and Me

There’s a holdup in the Bronx,

Brooklyn’s broken out in fights.

There’s a traffic jam in Harlem

That’s backed up to Jackson Heights.

There’s a scout troop short a child,

Khrushchev’s due at Idlewild

Car 54, Where Are You? – Nat Haken

One of my favorite shows growing up was Car 54. It shaped my image of police as goofy, seven-year-old appropriate friends in a big yet friendly world. Thank you, NBC circa 1962.

Fast forward fifty years, plus a couple more. I’ve heard the term police brutality, winced at the Rodney King videos, and dismissed my children’s complaints that police harassed teens on Cambridge Common. Anything that didn’t jive with the antics of Fred Gwynne and Joe E. Ross simply didn’t stick. Like many middle-class white folks, I could count my complete interactions with police on one hand. Every one of them benign.

Four years ago, fresh home from a 20,000-mile meander on my bicycle, I was fishing around for community activities. Mary and John, a lovely couple I know, suggested I join the Cambridge Police Auxiliary. The idea appealed to my conviction that if we simply extend ourselves to one another; regardless of income, education, or politics; we can all reach accord. So, I entered the training program to become a City of Cambridge Auxiliary Police Officer.

The Cambridge Police Auxiliary doesn’t do a whole lot, mostly direct traffic for city events like marathons and parades. But they’re valuable ambassadors, the physical manifestation of community support for our officers in blue. Auxiliary police do not carry guns; they don’t even have to know how to shoot. I envisioned myself as law enforcement’s friendly face.

Training was terrific. I got a behind-the-scenes tour of Cambridge’s snazzy new police station. I learned how to respond to taunts with respect, and how to stay calm among intoxicated rowdies. (As the son of an Irish drunk, this was more of a refresher course.) I learned how to strike a stable stance: legs spread, feet angled apart, knees flexed. I felt butch, so solidly planted. I was the oldest trainee; the only one not volunteering as a stepping stone to eventually, hopefully, joining the full-time force. Still I felt welcome. I might have finished, I might have actually cordoned off streets for community races and encouraged Head of the Charles revelers to move along, if I hadn’t realized that, although owning and firing a gun was not required: that was the bond. When the trainees planned a day at a shooting range in advance of our indoctrination, I realized my connection with my fellow auxiliarians was flimsy. I dropped out.

Then Derek Chavin crushed George Floyd’s neck, and something broke in me. What manifested itself as reeducation and greater public activism was really the death of long held belief. I can no longer pretend that police are fundamentally good; that Derek Chavin was ‘one bad apple.’ After all, three of his brothers cheered him on.

On July 25, 2020, at 8:24 a.m., while in the process of committing the crime of defacing public property, Massachusetts State Police Officer Stanley stopped his vehicle and approached me. He demanded to know what I was doing (stenciling the names of Black people killed by police on the guardrail where we took a knee every evening), asked if I had permission (I had written to DPW—twice—and interpreted no reply as assent), told me my efforts were wrong since those killed weren’t from here (I remained silent per civil disobedience training), proceeded to state misleading information about jurisdiction for this property (i.e. he lied), told me to stop, clean the area, and leave. Trooper Stanley wore a badge. His gun glistened in the morning sun. My only weapon was a paintbrush. Thus, my longest interaction ever with a police officer ended with me doing exactly as he commanded.

Trooper Stanley won the Saturday morning skirmish of the guardrail. But he lost the battle: on two fronts. Within days, other folks painted all sorts of messages on the guardrail, in support of Black Lives Matter, in support of the police; a chaotic visualization of our bifurcated nation. Officer Stanley also lost the battle for my support. Quick as a flipped switch, I viewed police in a completely different light. After offering default respect to anyone in the uniform for sixty-five years, my initial response to every police officer I see today is: you have abused your power too often, for too long. Despite what’s painted on your car, you do not protect and serve. My respect is no longer granted. It must be earned.

Machiavelli’s dictum: “Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts absolutely,” applies to institutions as well as men. One by one the securities of my youth have fallen. The Catholic Church is morally corrupt. Corporate America is ethically corrupt. Police are racially corrupt. There is nothing surprising about these institutional failures: anything granted outsize power breeds the cancer that fuels its own doom. The challenge of democracy is to be constantly vigilant of power abused. To curb and restrain and readjust. Which is what we need to do—now—with our police.

February 23, 2022

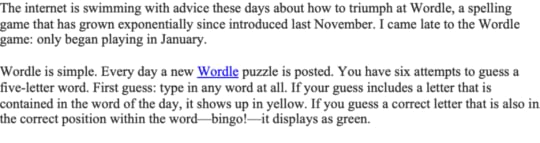

Wordle: Success!

February 16, 2022

Spielberg’s West Side Story:

Withered on Arrival, Dead at the Box Office

The nominations have been announced: welcome to Oscar season! Steven Spielberg’s remake of West Side Story nabbed seven. I call that a gesture of sentimentality.

Before last December’s premiere, my musical theater friends (of which I have several) celebrated the reboot of this American classic. My response to their excitement was: why?

Movie remakes are common. A Star is Born three times over, and each iteration has its merits. There’s also money to made remaking a classic. The original West Side Story won a whopping ten Oscars. It was also box office gold: recouping its $6.5 million budget more than six times over (worldwide receipts: $44 million). Surely we are ready for a dazzling yet culturally sensitive update.

Ahhh, I never thought so. And judging from the tepid audience response the film has received ($62 million worldwide on a production budget of $100 million two full months after release), neither do many others.

Here’s my take on why:

American film took a sharp turn circa 1970, flipping from a medium that specialized in escape to one that held up a mirror to reality. All of the flashiest movie musicals, from The Great Ziegfeld through West Side Story, The Sound of Music, and culminating in Oliver! premiered prior to 1970. Each capitalized on the silver screen’s enormous scale to create worlds so ecstatic that mere speech was insufficient. Our heroes simply had to burst into song.

Once Hollywood caught its New Wave, such exuberance didn’t fly.

Big-time musicals still churn magic on stage: theater audiences are eager to suspend belief. But film is too prescriptive a medium to accommodate the ambiguity of characters who are simultaneously like us (mere human beings) and yet not like us (when confronted by trauma or delight, they sing). Movie-worlds are very specific. They either reinforce the reality we already know, and hopefully deepen our appreciation of it, or—like most blockbusters—they provide escape to fully realized alternatives. That’s why the few great movie musicals made since 1970 (1972’s Cabaret and 2002’s Chicago) incorporate songs as commentary on the characters interior lives or society’s tumultuous times. What Rogers and Hammerstein’s ground breaking Oklahoma! accomplished on stage in 1943—integrating music as direct extension of the action—comes off as odd, even silly, on today’s screen.

Given how movie audiences have changed, Spielberg’s West Side Story battles uphill before the opening credits even begin. Hoodlums dancing through New York City streets in 2021 simply don’t elicit the same delight they did sixty years ago.

Unfortunately, once the credits begin, the film establishes a further tone of doom. The original West Side Story begins with a bright orangey-red screen. Vertical lines pop in rhythm with the upbeat overture, then morph into the Manhattan skyline as viewed from the statue of Liberty. We, the audience, are immigrants arriving in hope after a long voyage. The camera shifts up and over the city’s grid and flies us over the island, revealing the promise of America, eventually landing, softly, into the territory of the Jets.

Spielberg’s West Side Story also opens with aerial footage: demolition wrought by urban renewal. Similarly, we land on Jet’s turf. But before one single Shark appears, any promise, any hope is futile: the neighborhood is already lost to powers greater than either of these two-bit gangs.

West Side Story, based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, is a tragedy no matter how interpreted. By the end, most of the major characters are dead. But the tenor of the original film, like most musicals, is mostly upbeat. We know the sparring between the Sharks and the Jets is petty; that it will lead to no good. But at least they’re fighting with intention over something they believe is worth having. In the recent version, the gangs are neutered from the start. Forces beyond the screen have already won, so there’s literally no one for the audience to root for. I credit screenwriter Tony Kushner for the hollow ache ag the center of this film. The language in the script is beautiful, the insights deep, yet as in any Kushner endeavor, the overall affect a downer.

There are two disparate audiences for West Side Story 2.0. People who saw the original and want to see how today’s masters handle the same material. And people too young to know West Side Story as a cultural phenomenon. The latter group, by and large, find the story irrelevant, and have stayed away. The older group, who showed up as a dismal dozen for the Christmastime matinee I attended, find it all too relevant if only because so little has changed. The prejudices, the violence, the injustices of the 1961 film are all still with us: made uglier by our media-saturated age. A movie-goer above a certain age doesn’t actually watch the film. We analyze it, comparing frames and dialogue and phrasing with an original we know so well.

There are many things about Spielberg’s West Side Story that are better than the original. Bringing “America” off of the rooftop and into the street makes sense. Setting “I Feel Pretty” among an after-hours cleaning crew cavorting through Gimbal’s is terrific. Casting Rita Moreno as ‘Doc’ is an inspired idea. Every scene with her throbs with energy, even when she delivers the loneliest rendition of “Somewhere” ever conceived.

A few of Spielberg’s moves work less well. As a director allergic to serenity, Spielberg litters Tony’s rendition of “Maria” with visual distractions. Trust me Steve, the audience simply wants to hear Ansel Elgort deliver the goods, which he does beautifully. And to whomever decided to jump from the deaths at the rumble directly to the Gimbal’s girls: bad shift.

The new West Side Story is a bountiful kit of parts: great scenes, good acting, excellent singing, lush orchestrations, phenomenal dancing. But ultimately, the pieces do not come together to create a vital work of art. The ‘updates’ strip away the fantasy elements that make musicals such delight, without being bold enough to forge an independent vision. The movie begins with a bleak view of the world, and despite snazzy dancing and colorful skirts, ends on the same drab note.

One of my most enthusiastic musical buddies claimed, “They will be talking about this movie one hundred years from now!” Without doubt, we’ll be celebrating the 1961 in version in 2061. But Spielberg’s decaying Manhattan in 2121? I doubt it.

February 9, 2022

On Rent Control: Part Four—Opportunity

The Joint Housing Committee of the Massachusetts Legislature recently held a virtual hearing on House Bill H.1378, a proposal to grant cities and towns the right to establish rent control. As a person who lived in a rent control apartment, then owned rent-controlled apartments, and now owns unregulated apartments, I have broad experience of the issue. This series explores the potential, and pitfalls, of rent-control as a mechanism to address our housing supply and affordability crisis.

Link to Part One—Legal History

Link to Part Two—Personal History

Better Options to Addressing our Housing Crisis

The knee-jerk reaction to addressing our housing crisis is simple: build more housing. That is certainly part of the solution. But a comprehensive and sustainable approach to ensuring housing for all must also include: create different housing. Different types of housing, different size housing, different arrangements of groups sharing housing.

Over the past seventy-five years, the average size of a home in the United States has more than doubled, while the average family size has shrunk. Most of us occupy more square feet than our parents, and magnitudes more than our grandparents. Space that we must heat and cool and furnish. Space that, despite stricter energy codes, consumes an unsustainable amount of fossil energy. We cannot construct housing for all without structural changes to the way we conceive and deliver housing, because the lion’s share of housing we create is simply gobbled up by the ever more affluent end of our population, while bottom dwellers are denied access.

The atomization of our housing fuels another problem plaguing our nation: the mental health of loneliness. Twenty-five percent of us live alone. A direct result of an affluent society that celebrates autonomy. Yet, humans are social creatures. For all we crave independence, isolation is unhealthy.

I began researching this series, “On Rent Control,” with an open mind as to whether Massachusetts should reenable rent control. However, the more I read, the more I understood that rent control provides housing security for a select few at the expense of others. Its most tantalizing attribute is political: the illusion equity without public cost.

There’s no value in denigrating one approach to providing affordable housing without offering options in its stead. And so, I offer this smattering of ideas that, collectively, could actually alleviate our housing crisis. They fall into two main threads: First, opportunities that require public resolve without large public expenditures. Second, opportunities that require public resolve—and public money.

Increasing Housing Stock and Affordability without Large Public Expense

Some of these ideas have been around awhile; others may be new. Some tread on existing rights of property owners, but no more than rent control does.

1. Zoning Reform. The first, most obvious, and most impactful way to create more housing, and more affordable housing, is zoning reform. Zoning’s noble roots as a means to ensure public health have been coopted to protect property values. We should abolish all single-family zoning. We should enable auxiliary units in existing buildings, or in fresh outbuildings. We should reduce parking requirements to allow greater density.

Zoning reform would actually cost less than instituting rent control. No need to create the bureaucracy of a Rent Control Board; zoning review boards already exist. In addition, rather than simply regulating existing dwellings, looser zoning would actually create new dwellings.

2. Inclusionary Zoning. Maintain, and possibly expand, inclusionary zoning. Since Cambridge is a desirable place to develop, the city currently requires 20% of residential units in new buildings to be ‘inclusionary.’ (i.e. rented to people of moderate income). Although inclusion does not serve low-income people, it is a welcome and integrated form of subsidizing moderate income housing. Can we boost it to 25%? Will the developers still come at that threshold? I think so.

3. Shared Housing. Create more generous forms of shared housing. In a college town like Cambridge, shared housing can have a bad name. Nonetheless, it exists. Current zoning defines four or more people living together as ‘group housing’, with different requirements than a single-family unit. Group housing should be better defined, more easily organized, and given inducements, so that four, five, six, even eight people can live legally and cooperatively.

4. Housing Match. Instead of creating a Rent Control Board, how about a Housing Match Board? Cambridge is full of people, mostly elderly, who have extra room. They might welcome an additional person living with them, whether for assistance, income, chores, or just companionship. Craigslist and NextDoor provide ways for individuals to trade goods and services, but don’t offer the kind of vetting that someone seeks before they welcome another into their home. What if the city developed guidelines to define and match these opportunities?

5. Legislate and/or Tax Dwelling Units Taken Out of Service. If it can be legal for the city or state to establish maximum rents on privately owned property, why not consider other, more generative forms of controlling existing housing stock? Every block of my Strawberry Hill neighborhood has two family houses that have been converted to single-family, as well as two-family houses where the owners no longer rent their extra unit. In a city short of housing, do owners of multi-family buildings have a responsibility to rent them? Can the city restrict conversions that reduce the total number of dwelling units? At the very least, let’s levy a hefty tax on units taken out of service and allocate that money to creating new housing.

Former Two-family House, now Single Family, in my neighborhood

Former Two-family House, now Single Family, in my neighborhoodIncreasing Housing Stock and Affordability through Public Measures

Regardless of zoning reform, inclusion requirements, and disincentives to take units off line, we are unlikely to address the problems of affordable housing for all our citizens though manipulating the parameters of private ownership. Some tenants will remain too poor; too challenging. Public interest in building and operating housing for people unable to participate in the private market has waxed and waned over the past century. But we have enough examples of doing it well that if we commit with purpose, and allocate the money required, we can house everyone.

1. Expand Section 8. The Section 8 program has many benefits, primary among them that it integrates tenants in the fabric of existing community. Section 8 does not increase the amount of housing per se, but offers access to more units for low-income people.

2. Build more affordable housing. Easier said than done. Whether through the Cambridge Housing Authority or local non-profits, we need more fully affordable housing projects. The recent 100% Affordable Overlay Zone is a good step in this direction. Now, we just have to pony up funding.

3. Build more alternative forms of housing. The private development market is not a forum for innovation. Developers only build what they know will rent: independent, full-service dwelling units. The more private amenities, the better. Publicly funded housing should move beyond creating warrens of individual apartments. We should use public resources to experiment with new, more sustainable and socially integrated forms: congregate housing where four-to-six-bedroom suites share common spaces; old school SRO housing in urban centers; even residential hotels where residents’ private suites come with chits to local restaurants or a subsidized dining room. All options that provide housing for single or coupled people in less space. All options that encourage people to be out and about. All options that, if proven successful, the private market will emulate.

No one of these suggestions will solve our housing crisis. Given our culture of uber-privacy, I doubt many will be realized. The American mania for autonomy baffles me. I’ve lived with other people my entire life, as family, spouse, or housemate. I find the tremendous benefit in having someone nearby—accountable for and accountable to—offsets the downside of, like, having to get along with someone else on a bad day. Besides, living among others is more sustainable, more affordable, and more sociable.

Our housing crisis is real. Implementing rent control is an easy feel-good that won’t really address the issue. This essay outlines eight other possibilities, none of which will resolve the problem in total, any of which can provide more housing, or more affordable housing, than rent control offers. The solutions I suggest—and there must be others—will be more difficult to bring forth than simply rechurning rent control.

Do we have the resolve required to rise beyond an approach already tainted, and implement real change in how we will live and how we will care for our fellow humans?

February 2, 2022

On Rent Control: Part Three—Prognosis

The Joint Housing Committee of the Massachusetts Legislature recently held a virtual hearing on House Bill H.1378, a proposal to grant cities and towns the right to establish rent control. As a person who lived in a rent control apartment, then owned rent-controlled apartments, and now owns unregulated apartments, I have broad experience of the issue. This series explores the potential, and pitfalls, of rent-control as a mechanism to address our housing supply and affordability crisis.

Link to Part One—Legal History

Link to Part Two—Personal History

Can Rent Control Help to Address our Housing Crisis?

Social assistance programs transfer resources from one group in society to another. Our reasoning for these transfers falls into two basic camps. First: all humans are entitled to basic food, shelter, and healthcare (thus: food stamps and Medicaid). Second: we attempt to balance opportunity and access in an inherently inequitable society (thus: higher education Pell Grants and set-asides for minority businesses). Ultimately, every social program debate can be reduced to whether something ought to be taken from Peter to benefit Paul. Since I believe everyone is entitled to the basic requirements of life, and that we should attempt to balance the inequities of our world, I support both approaches.

There are also two fundamental ways in which resources are redistributed. They’re either ‘targeted’ by need (again, food stamps and Medicaid) or ‘universal,’ equally distributed across the entire population (the recent Economic Impact Payments). Both forms of redistribution are valid, though each achieves different purposes.

To assess whether rent control is a worthwhile social program, let’s consider whether it helps fulfill a basic human need and/or balances inequities of our society; and whether it’s ‘targeted’ or ‘universal.’ The studies and statistics I reference are from, “Rent Control: What Does the Research Tell us about the Effectiveness of Local Action,” a white paper published by the Urban Institute (January 2019) and “America’s Rental Housing 2020,” by the Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Does rent control help fulfill a basic human need?

At first glance, the answer to this question is yes: rent control provides secure housing because it remains affordable to tenants over time. However, evidence indicates that rent control dampens the development of new housing. Thus, while it provides security for residents of rent-controlled units, it hinders the total amount of housing available.

Does rent control help to balance the inequities of our society?

In 1994, when Cambridge lost the ability to enforce rent control, 26% of people living in rent-controlled units were in the bottom quartile of income; while 30% of rent control residents were in the top half. At first glance, it appears beneficiaries of rent control at least parallel economic strata.

However, lower income people are more likely to rent than own. Over 40% of families in the bottom quartile rent, so if they claim only 26% of rent-controlled units, they are actually underrepresented. Since rent control doesn’t include income guidelines, and since most landlords will be predisposed to higher income tenants (as I am), logic follows that proportionately fewer low-income families will benefit.

If we include income guidelines into rent control, the program could better balance inequity. Unfortunately, this would usher in a new set of challenges. How would we monitor income eligibility? If a family’s income rose above a certain threshold, would they have to move out? Would this be reverse discrimination against people whose income exceeds the guidelines, as they would have less access to the pool of available rental units? Providing means tests to rent control would enhance the claim that rent control provides more affordable housing for those who need it. But the means are thorny.

Is Rent Control ‘targeted’ to a particular group?

As long as rent control does not include a means test, the only group it targets is renters as opposed to owner-occupants. Although renters, in aggregate, are less affluent than home owners, there are plenty of renters who don’t fall within most governmental definitions of ‘need.’ In fact, people who live in rent control apartments are statistically older, single, and childless when compared to renters overall. Again, the beneficiaries of rent control do not neatly align with groups in need of assistance.

Can Rent Control be applied universally?

The answer to this is: definitely not. Rent Control is limited by the number of units available to control, not the number of people who could benefit. It creates a new category of division in our cities: those who receive rent control, versus those who do not. A recent study in San Francisco estimated the economic ‘transfer’ of those living in unregulated units to those living in rent-controlled units is $2.7 billion per year. That’s a mighty big transfer to people who very likely landed their rent-controlled apartment through luck or connection rather than need.

If rent control does not meet the basic requirements of an effective social service program, why is Massachusetts considering enabling it (once again)? The answer is easy as it is illogical. Politics.

Enabling cities to establish rent control provides the illusion of doing something about our housing crisis at no direct cost. It costs the state nothing to pass the legislation. Cities who implement rent control bear only the cost of their operating boards. Politicians can say, “We made over 50,000 units in Cambridge more affordable,” without adding a single residential unit to our city.

Rent control is a politically expedient means to claim progress in our housing crisis, and a demonstrated path to creating a secure voting block among the lucky folks who wind up occupying rent-controlled units. State Senators, Representatives, and City Councilors know that the unlucky ones, who cannot find an apartment in Cambridge, won’t be voting in their district!

If rent control isn’t a panacea, how can we address the crisis of housing availability and affordability in Cambridge and beyond?

Tune in next week for…Better Options to Address Our Housing Crisis.

January 26, 2022

On Rent Control: Part Two—Personal History

The Joint Housing Committee of the Massachusetts Legislature recently held a virtual hearing on House Bill H.1378, a proposal to grant cities and towns the right to establish rent control. As a person who lived in a rent control apartment, then owned rent-controlled apartments, and now owns unregulated apartments, I have broad experience of the issue. This series explores the potential, and pitfalls, of rent-control as a mechanism to address our housing supply and affordability crisis.

Link to Part One—Legal History

Rent Control and Me

My first experience with rent control came quick upon getting engaged. Time for me and my fiancé to move out of our respective group houses into a place of our own. Our budget was tight, apartments scarce. In July of 1979 we found a 425 square foot one bedroom on Mass Ave between Central Square and Harvard. Four tiny windows facing a blank wall. A measly abode in an excellent location for $224 per month. We signed a September first lease, confident that love would bind in such tight quarters. In the last week of August we received a notice from the Rent Control Board: the rent on our apartment was reset to $277. What the $#@**%. A 24% increase! So much for rent control, like, controlling our rent. We tightened our belt and winced every month as we wrote out the check.

Years passed, and the traditional single-family house always dangled beyond our financial grasp. We moved to Oklahoma City and purchased a two-family house in a place where no one’d ever heard of rent control. Moved back east in 1986 and purchased a two-family in Somerville, where rent control had already been terminated. By 1992, we had two children and decided to relocate along the Route 2 corridor: Lexington, Arlington, Belmont or Cambridge. I’m a city guy, but Cambridge was a long shot: houses were either super experience or, if under rent control, in shambles. Lucky us! We come upon an albatross: an asymmetrical four family with a large three-story unit attached to three flats. The sellers (SPOA activists) had legally subdivided the place down the party wall, but the communicating porches and cross-doors defied the simple line drawn on the paper deed. Our real estate agent proved a savvy negotiator, and we flipped from being out-priced seekers to mortgaged owners of a 5,000 square foot behemoth. Still, everyone wrinkled their brow at our stupidity: you bought a house under rent control?

The illogic of the system became immediately apparent. The smallest apartment, an attic studio, had the highest allowable rent, by a wide margin. The appraiser thoroughly investigated the side we would inhabit, but declined to even walk inside the rent control side. He explained, “The value of a rent control property is established by rents set by the Board; the actual condition is irrelevant.”

Within a week of closing, I received notice to appear before the Rent Control Board. I arrived in dress shirt and tie, clueless to the agenda. I was greeted as the enemy, with full bore skepticism and derision. “Why did this building get legally subdivided?” “How are you trying to circumvent rent control?” I knew that the rent control equation was a zero-sum game: the previous owner had subdivided a four-family building, in which one unit was owner occupied and three under rent control, into two legally separate properties. As the new owner of both properties, we would live in the ‘single family’ while the ‘three family’ would remain under rent control, since it was not owner occupied. The legal description of the property had changed; the de facto rent control status had not. This reality did not stop the Board from grilling me from every angle, convinced I was up to no good. I remained uncharacteristically calm; while they fumed.

The following summer my attic-studio tenant moved out. Within an hour of posting notice, I had three applicants. One was a single mother with a young child. The second, a single woman who planned to run an at-home day care out of the apartment, The third was a medical resident at Children’s Hospital. Since rent control did not demand a means test or other social criteria, I did what any conscientious landlord would do: rented to the person with the highest and most secure income. The medical resident proved to be an excellent tenant.

In the run-up to the 1994 state ballot initiative that ended rent control, local media was ripe with pro-rent control articles. One morning, the front page of the Cambridge Chronicle featured an article about the woes of a tenant who claimed “I will not be able to afford my apartment if rent control is eliminated.” The quote stuck in my throat. The subject of the article was my own tenant and no one— from the Chronicle or anywhere else—had asked me, her landlord, what her uncontrolled rent might be. I called the Chronicle, accused them of pandering, and lambasted their shoddy reporting. The following week, the cover page story featured me, explaining how small landlords valued continuity and would not necessarily toss out every tenant in the city.

For the last thirty years I’ve managed the three apartments attached to my own house. I am attentive and fair in the rents I charge and maintenance I provide. So far, I’ve only had one tenant to whom I have not offered an extended lease: the woman from the Chronicle article. I am disinclined to be generous toward people who malign me, even if indirectly.

My three apartments are safe and sanitary, yet hardly fancy. The rents I charge fall within the guidelines of HUD’s Section 8 rental assistance program. I could sign on for the program and be guaranteed tenants and rent. But I do not. I know how arbitrary HUD guidelines can be from my days designing affordable housing, and rumors surrounding the hassle of annual property inspections keep me from welcoming the housing authority into my 120-year-old building.

I am fully aware of the inconsistency in my behavior. I believe everyone should be entitled to basic housing, and I could provide truly affordable housing to at least a few people. Yet I steer clear of inviting government busyness into my affairs, and choose to rent to folks whose decent incomes don’t require subsidy.

My personal experience with rent control reflects a program that proclaims a set of benefits far different than what it delivers. If the state once again passes enabling legislation to allow rent control in Massachusetts, and if the City of Cambridge adopts it, of course I will comply. But we’ve already lived through one generation of rent control, and it failed to deliver affordable housing to those in need. I wonder: can rent control be structured to better align with our objectives, or are there are better ways to achieve stable housing for everyone?

Next Up: Can Rent Control Help to Address our Housing Crisis?