Paul E. Fallon's Blog, page 15

October 26, 2022

Bringing the World to Me

Next week, we’re having dinner with an organic farmer from Australia. Last week, a nurse from the Philippines shared the antics of that country’s infamous ruling family Marcos. Last month, a Russian geology student, nearing the end of the H-1 visa he received just before the Ukraine War erupted, was anxious to avoid what he referred to as, “the situation,” upon returning home. Over the summer, a lovely couple from the Czech Republic offered us a glimpse young people untarnished from ever living under Soviet influence. Another weekend, a Brazilian museum curator marveled us with the beauty of Belo Horizonte, a city of 3 million people which, probably like many Americans, I’d never heard of.

Vinicius implored us to come visit Belo Horizonte, just as Furkun invited us to Istanbul, and Sara wants to tour us around Prague. (Interestingly, Artem did not suggest we visit Ufa, Russia.)

Invitations notwithstanding, I doubt I’ll be visiting any of those places anytime soon, as I have no desire to travel anywhere. One of the last lingering habits of my pandemic existence seems to be an extreme contentment in being at home. Yet I’m curious as ever about the world around me. So, instead of traveling, my housemate and I have opened our doors to couchsurfers, who brings the world to us.

“Couchsurfing” is a term that means offering a traveler a place to crash for a few nights. It’s also a web site (www.couchsurfing.com). It’s also a mindset, a way of being, a demonstration of living outside the norms of individual privacy that infect these United States.

I first learned about couchsurfing back in 2015, when a former hippie I met in Oregon told me I could find places to stay while bicycling throughout the country. She jumpstarted my immersion by providing my first reference. Over the next year I stayed with dozens of couchsurfing hosts all over the country. I did not have any dangerous experiences, though I will admit to several weird ones. Some people offer you a guest suite with a basket of warm muffins in the morning; others eat their dinner right out of the pan and don’t offer you a bite. Gun owners like to show off their racks; Mormons like to show off their children. The key to enjoying couchsurfing is: have no expectations and welcome every host as an adventure.

When I returned home it took a while to convince my housemate that he would enjoy hosting couchsurfers. If you haven’t done it, it can sound a bit odd. Over the next few years, several people I had stayed with across America came to Cambridge; and stayed with us. Finally, my housemate admitted that he liked them all, and agreed to list us as “Accepting Guests” on the couchsurfing website. When the pandemic hit, there were no guests to accept. Gradually, that has changed. We got a trickle of requests, hosted a few nice folks; the trickle became a river; and these days the requests are nearing flood proportion.

Our objective is to host one or two people a month. We always do that, and sometimes more. We could easily host two or three guests a week. So far, our hosting experience mirrors my experience as a guest: no dangerous people, a few oddballs, mostly awesome folks.

Choosing who to accept is a bit of a challenge; a bit of a game. First criteria: instinct. If something seems off, it probably is, and you don’t want to invite your worries into your own home. Second: profile. What has this person said about themselves and their travels to the world? If someone’s profile is mostly blank, I’m not likely to invite them. Third: references. We will not invite anyone to stay with us who does not have references from other hosts. I realize that this is a Catch-22 for people new to couchsurfing, but positive references are the currency of this community. You must be clever to get your first ones, but then they multiply. I have 55 positive references in my profile; some people have hundreds. We don’t require anywhere near that number, but a person needs to have at least a few.

If someone interesting meets those criteria, we are likely to invite them. If it’s a time when we receive many requests, we up the ante and read their ‘ask’ with more interest. Did they customize their request to reflect what’s in my profile? Does their request align with what we offer? Our profile is clear: we accept guest for one or two nights only. We’re not likely to accept anyone seeking a full week unless they make a truly compelling ask.

Aside from only wanting short-term couchsurfers, we offer a great stay. A private guest room. Good access to public transportation. And, we always have our guest join us for dinner at least one night. The point of couchsurfing is not simply to provide lodging for someone travelling on the cheap. It’s to share stories, opinions, learn how other people live.

For two years of my life, I was the traveler who arrived on his bicycle with stories of adventure in the wide world. These days, I’m disinclined to be that person. Instead, I prefer being the host, and hearing about lives all over the world from the comfort of my kitchen.

October 19, 2022

Beautiful

“What I really remember…was the man telling my mother and me that it was difficult for his wife to live in Norman, because in Norman, no one tells you that you’re beautiful. ‘Not at the grocery store. Not at the hardware store. Not on the street. Nowhere! That is so hard for her.’”

Of course I as drawn to Rivka Galchen’s childhood memoir as an Israeli immigrant growing up in Norman Oklahoma in the 1970’s. (“Who Will Fight with Me,” The New Yorker; October 3, 2022). I was an immigrant of sorts myself in that place and time; where my Jersey edge was almost as foreign as Ms. Glachen’s Judaism. Yet the line that grabbed me had nothing to do with either the particulars of Rivka’s enchanting, mercurial, meteorologist father (Norman OK, nestled in Tornado Alley, is home to the National Severe Storms Center. The place is teeming with meteorologists.), or the lulling, happy childhood that a place like Norman can induce. It was this one-line vignette that another immigrant—a graduate student from Brazil—offered Rivka’s family.

At first glance, you kinda wanna slap the Brazilian wife upside the head. Really, girl? The worst thing about living in the United States is that no one fawns over your beauty? Get a grip. Until the husband’s complaint seeps in, and you realize the pain we all endure in a society where so much cannot be spoken.

When was the last time I told someone I did not know well, in public, as a matter of daily course, that they were beautiful? The answer for me, and I imagine many others, is: never. American culture has always been stingy on unsolicited praise, and in these days of toxic misunderstanding, giving someone you don’t know well an unsolicited comment is like begging to be cancelled.

In my years of staffing the Information Desk at my local hospital, I learned that it was alright to give unsolicited compliments to some people who approached: the matronly Black woman’s fabulous hat deserved notice; the woman with inch-long finger nails enameled and rhinestoned, glittered for attention; the disheveled gent wearing a crisp “Marine Veteran” cap stopped belly-aching about being screened if I said, “I appreciate your service.” If I was feeling feisty, I might even compliment a young Black man on his razor-sharp haircut. But I never complimented a white woman, or any age, for any reason. They are too prickly to risk a venture into pleasantries.

Yet even among those I complimented, my focus was always on some component they had personally shaped; their defining accessory. Never anything as all-encompassing or arbitrary as, “You are beautiful.” Although that statement means the exact opposite of, “You are ugly.” Each is equally, and totally inappropriate.

The Brazilian man’s wife is certainly not the only person who would appreciate receiving a positive compliment from a well-meaning stranger. Flattery is a basic human boost. The problem, of course, is that the compliment stirs the bubbling pot of power dynamic, entitlement, and who gets to define beauty. Note: the Brazilian man does not bemoan that no calls him beautiful; he likely has other means and measures of receiving affirmation. I suppose many the well-intentioned feminist would advocate for the man’s wife to find other, deeper, forms of affirmation, rather than pining for comments from strangers about her physical proportions.

All of these arguments are valid and true. They are also dispiriting. For it seems a shame that we live in a world where, when we come upon someone who is beautiful, we can’t simply express our joy in their gift.

October 12, 2022

The Planet Fitness Conundrum

Planet Fitness has built a nationwide network of fitness centers based on simple economics: $10 per month. For the well healed, a Black Card membership at $23.99 entitles you to use any Planet Fitness location, have unlimited guests, and use the massage bed. Everyone also pays is an annual “equipment fee” of $69 to cover equipment maintenance. Still, the root appeal of Planet Fitness is strong: $10 per month.

I used to belong to a full-service gym, with a pool and a basketball court, yoga and Pilates classes, as well as acres of machines. It went under during the pandemic, so I joined my local Planet Fitness. I opted for the Black Card, as I frequent locations all over Greater Boston.

Plant Fitness is the McDonald’s of gyms: every one is the same. Yellow and purple walls with stone-age font supergraphics and gear logos. Lots of machines, an area of free weights, the 30-Minute Fitness corral, and the Black Card ‘lounge.’ Nothing less; nothing more. The speakers play the same music, the screens display the same ads touting convenience and low cost, with emphasis on our current fixation on clean, clean, clean. Plant Fitness facilities are, in fact, super clean. The staff is super nice. For ten bucks a month, Planet Fitness is an awesome deal.

The exception, unfortunately, is my home gym in Cambridge, where the staff is spotty and the space is, frankly, filthy. My experience there hit a low last Saturday morning. The gym was open, the lights were on, people were during their thing. However, there was no one at the desk, no one monitoring the workout area, no one cleaning the locker rooms. I checked in, changed, and did my workout. Trash cans overfull, paper towels scattered on the floor, locker room floor slippery with water and random coils of body hair. Still no sign of staff. I slipped behind the reception desk and helped myself to massage chair coins. In the lounge, I encountered a staff person draped over a massage chair, engrossed in a cell phone conversation. (A sign states no cell conversations, but let’s not quibble.) He chatted with whomever throughout my entire massage, still at it when I finished. I showered, dressed, and left. The check-in desk was still unstaffed.

Clearly, the gym had inadequate staff, and what staff there was, was negligent. What’s a person to do? Confront the guy chatting with his chum instead of working? Complain to non-existent management? File a report on the Planet Fitness website? None are satisfying options. Yet, my experience did not match Planet Fitness’ advertisements. At all.

Fortunately, I had just completed a good workout, so was mellow enough not to confront the lackadaisical non-worker. In fact, I tried to see things from his perspective. The Cambridge Planet Fitness often advertises for staff. Recently they posted $14.75 per hour. That is a pittance in an area where Target starts at $17 per hour, and Trader Joe’s is pushing $20 per hour. You’re not going to get chirper check-in folks and fastidious mopsters for $14.75 an hour. Maybe unlocking the door and turning on the lights is all we can expect from a person receiving that kind of wage.

The crux of the problem spans the full range of Planet Fitness’ operations: from a lowly unsupervised, disinterested employee right up to a national policy fixed on $10 per month. Fewer and fewer items sell for a dollar at Dollar General. Motel Six only cost six dollars per night, when I was six years old. Today, the closest Motel Six to me is a hundred bucks a night, even though I am decades away from my century mark. Eventually, Planet Fitness is going to have to raise its prices. I for one, am willing to pay more to go to a clean, well-staffed gym.

I don’t want to let Cambridge off the hook. I often go to the Planet Fitness in Dorchester, also a busy urban gym. Yet, Dorchester has friendly staff, neat workout areas, and gleaming locker rooms. Cambridge needs to clean up its act: be more like Dorchester. Which, if you know anything about the neighborhood dynamics of metro Boston, won’t happen anytime soon. Cambridge emulating Dorchester would be like intellectuals actually listening to workers. A topic for another day…

October 5, 2022

PERFECTION

Constellation at MassMOCA

Constellation at MassMOCAI associate the pandemic years with heightened awareness and training about how racism infiltrates, and often defines, our culture; the underbelly of white supremacy and capitalism. After George Floyd’s death, I spent many an evening in Zoom workshops and trainings, grappling with how we might order a more just and equitable world. The message was often difficult to swallow for a man who’s navigated the dominate culture pretty well, and benefited as a result. I came to appreciate how Zoom made it easier for me—accustomed to the take-charge stance often associated with white males—to lay low, listen more than speak, absorb the perspectives of voices that bloomed on a remote platform.

Power points, bullet points, listicles. The presentations often highlighted the injustices of white supremacist/capitalist systems, and then offered alternative ways to interact among ourselves. Antidotes to the status quo were often inspirational, usually utopian, sometimes naïve. But the ‘fundamental defects’ of our inequitable society were pretty much always cataloged in the same way. (For this essay, I reference the thirteen characteristics that Tema Okun outlines in her article, “White Supremacy Culture.”)

Some of these characteristics seem clear, and clearly problematic: Paternalism; Individualism; Power Hoarding; Progress defined as more and bigger; Quantity over Quality; Either/Or Thinking; and Fixation on one Right Way. Others are less obvious, but make sense with a deeper understanding: how our society thrives on creating an (often false) sense of Urgency; how it promotes Defensiveness; assumes a Right to Comfort; and fosters the illusion of Objectivity. I reach the limits of my ability to envision a new world if I must consider Worship of the Written Word as a societal fault: reliance on writing certainly favors people with a particular form of education, but do we really want a world that denies credence to either record-keeping or creative writing? Still, the most difficult of all Ms. Okun’s characteristics to embrace—the one she lists first—is Perfectionism.

What can be wrong for aiming for perfection? Perhaps even achieving it?

In Ms. Okun’s view, the pursuit of perfectionism makes us focus on what’s wrong, what needs to be fixed, rather that appreciate whatever portion of an endeavor may be satisfactory. It makes the output of our effort personal: you made a mistake and therefore you are a mistake. A culture of perfectionism turns us all into critics, often turning criticism upon ourselves, thus undermining our own esteem. The antidote would be a culture of appreciation, a culture where mistakes are learning opportunities rather than shaming opportunities.

What Ms. Okun aspires to: a more accommodating and appreciative culture is a worthy objective. However, I don’t see why she (and others) label the current state, ‘Perfectionism.’ I understand that the pursuit of perfection can be destructive—if it means trampling on others to reach the pinnacle. But the goal of perfection is a noble aim, and pursuing perfection has resulted in mankind’s most illustrative accomplishments. It is, in many ways, the brightest upside to human development: our desire to constantly strive; to be better; to be the best.

I recently watched a delightful and inspiring documentary, First Position, a serendipitous find from the local library that provided an evening of insight and joy. The film follows half dozen young ballet dancers in pursuit of a medal, or scholarship, at the Youth America Grand Prix in New York City. Ballet, like ski jumping, curling, or even football, is a pursuit of perfection that lies completely outside the realm of basic human subsistence. There is no practical, evolutionary advantage to exquisite jumping on pointe. And yet we love it, we aspire to it, and we laud those who achieve—dare I say—perfection in the act. The pain these six young dancers endure in chasing their personal glory illustrates the abundance of human spirit in a way that ‘woke’ curricula simply do not account.

It is easy to overlook the many good things that our current form of society provides. So many people are poor, disenfranchised, and prejudiced against, we forget that never in the history of the world have so many lived so well. True, we do it at the expense of our planet, and we need to address that. True, we do it at the expense of our fellow man, and we need to address that. But let’s be careful what we wish for. As I sat through hours of education about what a utopian world might be like, I often found myself envisioning a bowl of oatmeal: adequate sustenance that lacked texture or flavor. We don’t seek a just world in which everyone settles into the mean. We seek a just world where human excellence is celebrated, in many more forms than we currently value.

I find it odd—and wrong— to condemn the reach for perfection as another insatiable anxiety foisted upon humanity by a capitalist system hellbent on creating constant hunger. I think it is much more than that. It is the ultimate expression of humanity at its best.

September 28, 2022

MFA Boston Draws a Clear Line Between Fine Art and Community

It was the staples, that got to me. Stickpins too.

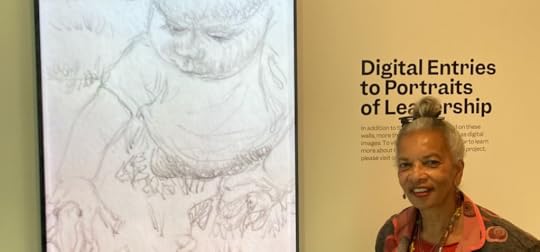

My friend Jackie emailed, in total excitement. A drawing she had made of her grandson, William, had been selected for an MFA Boston exhibit, “Portraits of Leadership.” “I’m not really sure what William has to do with leadership, though I suppose he represents future leaders. Still, I’m thrilled that one of my drawings will be on display at the Museum of Fine Art.” Jackie is an accomplished artist in pen, pencil and watercolor. Submitting a piece to the MFA was an aspiration too fantastic to ever dream: come true.

New logo for MFA Boston on mfa.org

New logo for MFA Boston on mfa.orgStaples right through the paper.

Museum of Fine Art Boston is rebranded. It has a new logo and a new font, blocky and easy to read. Their website has a banner ad that floats, “Art is better together.” A prominent page features a quartet of portraits under the heading “Here All Belong: Creating community where all belong.” The second paragraph of MFA Boston’s Mission statement begins, “The Museum aims for the highest standards of quality in all its endeavors.” The rebranding leaves no doubt: MFA Boston is all about inclusion.

Banner on mfa.org

Banner on mfa.orgStaples that made permanent holes in each drawing, every painting.

Jackie and I made plans to go to the MFA on a weekday afternoon to see her drawing. “I don’t quite know how they’re going to display it,” Jackie said. “I sent a digital copy, and they never requested the original.” Surely, I thought, the MFA must have some high-quality process they use to print electronic submissions. When we met outside the museum, Jackie was quiet, almost despondent. She had seen the display on opening day; this was her second visit. “Don’t get too excited.”

Community art work, bostonglobe.com

Community art work, bostonglobe.comStaples and stickpins that defaced every work of art.

“Portraits of Leadership” is a collection of drawings and paintings by local artists—and many school children—that accompanies the MFA’s temporary display of the National Gallery’s portraits of former President Obama and his wife Michelle. In one large, spacious gallery, hang two life-size portraits of the Obamas. In the corridor beyond, and on plywood walls built around columns in the visitor information area, are the community contributions to the exhibit: 5×7 sheets of paper, portrait orientation, stapled or stick pinned directly to the plywood. In the corner near the atrium café is a single digital display, where more than a hundred digital entries scroll through; ten seconds per image. Jackie and I waited patiently for “William and his World” to emerge so I could snap her photo alongside her artwork.

Jackie with “William in the World”

Jackie with “William in the World”Formalities extinguished, our anger rose. Why was this such a shabby display? How could the MFA stickpin and staple artwork directly to the walls? The message is all wrong: fine art displayed in gilt frames, while community art is permanently defaced.

After our visit, Jackie emailed her (our) concerns to Sophia Walter of the MFA staff. I appreciate that Ms. Walter responded; unfortunately all of her justifications only exacerbated the duality between fine art and community art. She said they made the exhibit as nice as possible given they had teen curators and 2600 items to display. Why did the MFA not use real curators? Why not select specific items to display, as they do in all of their other collections?

The message the museum will put forth is: we want wide community representation. The cynical reasoning I calculate is: 2600 items multiplied by two, maybe even four family members per ‘artist’ adds up to a lot of tickets sold. In fact, Jackie lamented, “I have other friends and family members who want to see my work on display. But I am so disappointed. How do I tell them it’s not worth the visit?”

I am not a museum curator or a display designer. However, it’s not challenging to figure out how to display hundreds of identically sized pieces of paper without permanently defacing them. Correctly spaced rows of narrow channels will do the trick, as many a retail display can confirm.

Obama Portraits at MFA Boston, boston.com

Obama Portraits at MFA Boston, boston.comBy definition, the MFA is an elitist institution. It decides what art to purchase, what art to display, and in that process it establishes the parameters by which our culture defines art. The MFA can rebrand itself, highlight inclusive words on its website, and proclaim a mission of highest quality endeavors. But all of that is simply eyewash unless it treats ‘community’ art comparably to ‘fine’ art, with appropriate standards of curation and display. “Portraits of Leadership” does not do that. Worse, it illustrates that MFA Boston is tone deaf, even in its effort to get ‘woke.’

The Obama portraits will be transported to the National Gallery, where they will be hung as treasures for years to come. The paper portraits stapled to plywood walls? They will surely rip when the display is dismantled. Damaged beyond repair.

September 21, 2022

Insatiable Want

“As Alito’s power on the Supreme Court has grown, and case after case has gone his way, he has come to seem more aggrieved.” The New Yorke

“As Alito’s power on the Supreme Court has grown, and case after case has gone his way, he has come to seem more aggrieved.” The New Yorke“Why is a man who is winning as much as Sam Alito is so furious?”

That line—deep into Margaret Talbot’s profile of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito, in the September 5, 2022 edition of The New Yorker—jumped out at me. After twelve pages of Justice Alito’s personal story, the pablum he offered the Senate at his confirmation hearings, his plodding behavior during his early years on the Court, his emergence as the right-wing kingpin of the so-called “Originalist” crowd, up to his tossing away a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization; that single line captured the man’s essence.

It also pretty much describes any human being who finally gets what he wants. The taste of victory is sweet, yet short. But when that victory is long-fought—and contrary to the public will—a man cannot rest on his laurels. Victory does not beget contentment. It only fuels resolve to deeper, more corrosive battles.

If you want to follow the evolution of Sam Alito in detail, please read Ms. Talbot’s excellent article. But if you want to view Justice Alito through the prism of just another power figure for whom every victory, every electoral vote, every Dow Jones jump is nothing more than incentive to enact bigger, more ludicrous, more repressive schemes, Ms. Talbot’s simple line sums it up.

Donald Trump wants to own the White House; Elon Musk wants to own space; Mark Zuckerberg wants to own our screentime; Tom Brady wants to own (another) Super Bowl ring. Sam Alito wants to own our private lives. These men are allergic to being content. Whatever they achieve only fuels them to want more.

The human condition is a balancing act between striving and contentment. Every man wants a better life for his child; yet every man reaches an age when he modifies his dreams and accepts his reality (except perhaps for the examples listed above). Many, perhaps most of us, can achieve a healthy level of contentment. Unfortunately, it only takes a few ravenous souls pushing, pushing, pushing their agenda for the rest of us to suffer the consequences of their bravado. A person who is content has no reason to exert energy against a hell-bent dynamo, until that dynamo has upset their contentment. In which case, it is often too late.

I don’t believe that insatiable want is the sole province of white men; in our society white men simply have the greatest opportunity to indulge gargantuan egos. Nor do I believe that women or BIPOC folk, given more access to power, would act more humbly. The sample pool is small, but Margaret Thatcher, Betsy DeVos, Ellen DeGeneres, and Will Smith are hardly shining examples of people who have used their outsized influence wisely.

Are humans genetically trapped by insatiable want? I can’t believe its fundamental to our DNA, as hunter gathers have no reason to hunt or gather more than they can eat before it rots. Agrarians, alas, have incentive to over produce…store…covet; and modern man has crafted a society in which work and wealth are distinct. Capitalism demands unrestrained so-called growth, and so far, globalism has only exacerbated the distinctions.

Regardless, even if insatiable want only infects a small segment of our species, and we could evolve out of it, we are unlikely to so in any timeframe that will stop our rapacious ways from destroying ourselves.

It may not seem obvious how Sam Alito is a threat to our existence in the same way that income inequality might lead to revolution or environmental devastation will lead to an uninhabitable planet. And yet, thanks to his opinion in Dobbs, a fifteen-year-old girl in Oklahoma is compelled to deliver a baby to term, even as she is too young to check out a book on sex ed from the library. That duality eats away at our ability to live healthy, informed lives just as much as a minimum wage job or a half degree Celsius.

And don’t think for a moment that Sam Alito will rest content on his achievement in overthrowing a woman’s right to an abortion. The man has a lifetime appointment to our highest Court. He has tasted victory. And he is furious.

September 14, 2022

AIM!

In case you are wondering what the opportunity cost of our consumer culture is, I suggest it is 234%: the net difference between a tube of Crest or Colgate toothpaste and their lowly competitor: AIM.

There are over 330 million people in the United States; almost all of us use toothpaste. The American toothpaste market is dominated by two major brands: Colgate (36% market share) and Crest (30% market share). That leaves a third of the playing field for all those down-market brands, such as Aquafresh, Ultrafresh, Arm & Hammer, and that 50’s favorite, Pepsodent; plus the niche pastes like Sensodyne, Parodontax, and Pronamel; as well as the preferred choice of the crunchy set: Tom’s of Maine.

I don’t use any of those toothpastes. I use AIM, a reddish gel, manufactured in New Jersey. AIM sells for $1.19 cents per 5.5-ounce tube at my local Target, as opposed to $2.79 for a similar size tube of Colgate or Crest. If you live near a Family Dollar, you can still get AIM for a mere 99 cents.

Surely, AIM must be inferior to Crest or Colgate, since it sells for less than half the price. I asked my hygienist, who informed me that AIM is easily as good as other mass market toothpastes. They all have fluoride, and AIM’s gel consistency is better for teeth and gums than abrasive toothpastes. I also checked online, where an NBC survey of dentists confirmed that AIM is considered equivalent by most dentists, and actually preferred by many.

So if AIM is equally good at less than half the price, it must dominate the market, right? The toothpaste aisle of my Target has rows and rows of Colgate and Crest, in a dizzying array of tube sizes, with a variety of embedded features. On the bottom shelf sits a single-wide stack of AIM.

Why is it that a perfectly good toothpaste that sells for dimes on the dollar of the popular brands has such a small market share, and so little shelf space? The answer is simple. When was the last time you saw an advertisement for AIM?

The next time you buy toothpaste, you can save 234% if you simply reach down to the bottom shelf. Or, choose Crest and Colgate and rack up another victory for Madison Avenue.

September 7, 2022

Tyranny in Fact and Fiction

My summer reading developed a prescient theme: tyranny. Every day, we hear terms like fascist, oligarch, autocrat, even democracy, tossed around the media with little or no consensus meaning. I developed a thirst to better understand what tyranny really is, how it’s played out in the past, and how it might visit upon us sometime soon.

Actually—how tyranny might already be here.

Fortunately, I came upon a trio of excellent books I recommend to anyone who wants a greater perspective on our nation’s ongoing challenges in civil civics.

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century by Timothy D. Snyder is longer than a listicle, yet short for a book. But it is dense, very dense. I recommend the graphic edition, with provocative drawings by Nora Krug. Each of the twenty chapters is only a few pages long, yet Professor Snyder (Yale) packs so much to ponder, I paused in front porch thought to consider each chapter’s implications. Then, after I finished the entire book, I read it all again.

Each of the twenty lessons is historically interesting. However, when I hit upon number 6 (Beware of paramilitaries), I realized that history is repeating itself, a bit too close. The rising number of paramilitary organizations proliferating in our country is dangerous, not only because there are so many guns in so many hands, but that those hands get trigger happy for reasons against our collective best interests. As Snyder continues on to #10 (Believe in Truth) and #14 (Establish a private life) I began to understand how tyranny, always sleuthing for opportunity to bloom, is gaining solid ground in these United States. I actually found a trace of solace in this book’s grim message with #18 (Be calm when the unthinkable arrives). Americans are notoriously difficult to herd. Let us hope that when the wannabe tyrant stages their coup, we will not be so docile as the Cambodians who marched into the killing fields, or the Germans who turned a blind eye as Jews, homosexuals, and gypsies marched to their death. The challenge, of course, is that the actual coup, whether occupying Phnom Penh or setting fire to the Reichstag, is a mere tipping act, enacted long after the populace has been worn down by so many seemingly small compromises to personal liberty and identity. History is full of well-meaning citizenry who blindly followed under the guise of freedom. American exceptionalism may not exempt us from tyranny’s call.

I came away from On Tyranny thinking it should be required reading for every high school student (as Civics used to be). I also think there should be a copy of it in every house so that when they come to burn the books, there will be too many copies of this thought-provoking treatise to flame them all.

Much as I valued On Tyranny, a non-fiction account of the fate that awaits the passive cannot invoke the same pathos as fiction. I discovered that, when it comes to fiction about tyranny, Hans Fallada is the master.

Hans, who, you say? I’d never heard of Fallada until a very well-read friend suggested him. Hans Fallada is a German author who survived World War I, led a checkered life as a journalist, novelist, and all-around depressant. His two best-known works chronicle the rise and fall of Nazism; the first by barley mentioning it; the latter by being consumed with it.

Little Man, What Now? recounts the endless petty challenges of a working-class bloke lumbering under the stagflation of the Weimar Republic and the naissance of the Nazis. Today, the novel reads as premonition, though when it came out, in 1932, no one could have predicted how accurately Fallada anticipated the atrocities to follow.

Every Many Dies Alone, published in 1947, is a fictionalization of actual enemies of the state: Otto and Elise Hampel, whose treason was so innocuous (they dropped one or two anti-Nazi post cards in public buildings every week), and so ineffective (virtually every card was immediately handed to authorities) that it took the SS over two years to find the petty resistors.

The treachery that loiters in the shadows of Little Man, What Now? is relentless in Every Man Dies Alone. What sustains each novel is an unconventional, yet sustaining love between the protagonist couple of each book. The tenderness of Johannes and Emma Pinneberg, and the complete trust of Otto and Anna Quangel, are among the most beautifully rendered images of marriage I have ever read; the human salve for so much trauma.

Whether you resonate toward short, fact-binding commentary, or prefer to explore the psychological wrath that tyranny showers on everyone involved, I recommend any of these books. We must all be keen to the threat that tyranny poses, or we will find ourselves under its thumb.

Illustrations by Nora Krug.

August 31, 2022

Mental Health V: Peace of Mind

The last in a series of five essays about Mental Health to celebrate the dog days of August.

Mental Health I: Why Do I Write?

Mental Health II: Suicide is Painless

Mental Health III: You Were Never Sick; Get Yourself Better

Mental Health IV: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The United States is the most individualist society on earth. Our relentless quest for autonomy causes us to suffer high rates of consumption, isolation, and loneliness. The internet and social media laid the foundation for online society and planted the confusion that virtual friends were equivalent to physical ones. When COVID-19 made virtual encounters the default choice, our atomization accelerated.

Weathering the shut-down was easier for me than many. I was already retired, so didn’t need to go anywhere; I enjoyed the company of a pleasant housemate; I live in a walkable city. Still, the pandemic left me, like so many, more isolated than ever. It also shut down my particular magic pill for mental health: without my gym, I atrophied. The careful balance I’d crafted through applying Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) slipped away.

An ugly exchange with a cherished friend spiraled me down. I spent a week in a swamp of despair, maybe longer. Time is an unreliable construct when I’m depressed. When the curtain of solace slowly ascended, and I was able to see how irrational I’d been, I realized it was necessary—once again—to reach out for help. I was more amenable to therapy this round, as my experience with CBT had been positive. I needed a CBT booster.

Instead, I enudred a series of interactions with health care providers so pathetic (yet common) I need not elaborate here. I finally found a large therapy group that advertised accepting new patients, persevered through applications and interviews, only to be told their practice was full. I suppose these frustrations provided therapy in themselves, as my exasperation with our miserable healthcare system eclipsed the emotional space occupied by depression.

At peak anger, three months after my initial quest for therapy, with nothing even potential, I posted a scathing Google review of the practice who advertised taking new patients, and then reneged. Guess what? Within an hour, I received a personal call from the head of the practice, with effusive apology. Would I rescind the review? Absolutely not! What can I do to make this right? Set up an appointment with a CBT therapist. Doctor Apology did not do that. However, a few days later, I received in the mail, The Cognitive Behavioral Workbook for Depression, by William J. Knaus, EdD.

It is a sad world, when a person only gets heard when he goes postal. I can understand people who say, “What’s he got to be depressed about?” I can understand that there are others with greater mental instability. I’m not trying to trump anyone else’s problems. My problems are not relevant to the cosmos, but they are real to me. They hold me back, and they make me miserable. Here I am, trying to steady myself before I slip into the trauma that once led me to suicide, yet no attention gets paid until I do something extreme.

The idea did not fill me with dread.

Actually, it was satisfying.

I appreciated the gesture of the workbook. And I used it. Twice a week, for over six months. I read, I notated, I wrote responses to the guided questions; an entire folder of essays that I’ll spare those of you who’ve read this far. I worked, I learned, I felt better, and I became more self-aware. I likely got more out of the workbook than I would have from another round of talk.

Then, something both strange and amazing happened to me.

One morning last year, at age 66, I woke up and my initial thought was, “Hmmm, I could live to be ninety.” And the idea did not fill me with dread. Actually, it was satisfying.

Waking to the pleasant prospect of life may not seem amazing to many. But this was the first time—the very first time in my entire life—that I woke in the morning and greeted the day, the week, the year, however long the gods choose to keep me around, with equanimity. For a guy who’s suffered morning dread for…ever, this was a superb beginning to the day.

This new mindset of awakening occurred, again. Then, with increased frequently. These days, waking to calm is my usual mode. And on mornings clouded with angst, I am quick to soothe myself. When stuck, I go back to the book, review how to direct my thoughts, and thereby modulate my feelings.

I know I’ll weather more episodes of mental anguish; my pot-stirring brain demands constant diligence. However, the stasis I’ve enjoyed over the past year is a revelation that will not easily dim. I have the tools and the confidence to vanquish the forces that made my days so grueling for so long. Confident enough to write publicly about my journey.

As I neurologically whither and physically deteriorate, new challenges will arise. I may yet choose to end my life someday: I am a strong believer in the right of a person to orchestrate their finale. But end it in depression? I don’t think so.

We have created a world fueled by competition and aggression, fixated on physical enticements, bereft of mental stability. Mental illness will surely escalate as the human psyche is further starved of calm, repose, reflection. I feel blessed to have found a path to peace of mind. I hope that others can find their own.

August 24, 2022

Mental Health IV: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The fourth in a series of five essays about Mental Health to celebrate the dog days of August.

Mental Health I: Why Do I Write?

Mental Health II: Suicide is Painless

Mental Health III: You Were Never Sick; Get Yourself Better

Mental health is a different animal than physical health, and though it’s important that we destigmatize mental illness and provide access to services and medications, our tendency to treat psychiatry as simply another medical specialty is misguided. Western medicine is rooted in considering the human body as a machine. When the machine is broken, we fix the components. Thus, we excel in treating physical trauma: repairing a broken bone is a matter of physics; installing a stent a function of fluid mechanics. Complicated chronic conditions are trickier: the same chemotherapy that remisses one person’s cancer may well kill someone else. The more complex our mind-body-societal interrelations, the more we flounder: no drug cocktail can calm a brain and alleviate all the stress our society inflects on a person’s sanity.

In the 1990’s, I was a forty-ish gay man in tumult, grappling with the realization that I’d spent most of my life running from a so-called mental illness that, turns out, had been redefined into the range of normal.

A psychiatric diagnosis is a reflection of the society that ascribes the label. Although mental illness may have roots in organic brain function, it often triggers in response to our over-specialized, hyperactive, competitive society; in revolt or capitulation to norms and expectations. By definition, a person who conforms to the basic standards of their culture possesses positive mental health, whereas a person at deviance to those norms is considered ill.

When I came of age, testosterone-fueled antics, heavy drinking, and sexual bravado were tolerated, even encouraged, as healthy signs of manliness; whereas male sensitivity was suspect, sodomy a crime, and homosexuality a certified mental disorder. Sixty years later, young men who drink, drug and whore to excess get shuttled off to twelve-step programs, while my particular predilections are legal and, in some sectors of society, my brand of masculinity actually embraced.

The proclivities of human males have not evolved all that much in two generations: we all still try to do whatever we happen to like as much as we can. What’s changed are society’s standards.

You’d think I’d be happy to learn, “You used to be sick but now you’re not.” Yet I suffered psychological whiplash. Years of having one’s nature bullied and denied hard-wires inadequacy. I was unable to simply rise one morning all Happy Gilmore, and during dark days I still knew depression as my oldest, truest friend. He might not be good for me, but he was a known quantity, and my life was so upended—marriage kaput, children by schedule, finances teetering, old friends grown distant—I welcomed depression’s familiar anchor.

I still dreaded mornings. I suffered doubt. I became jittery. I averted panic through constant activity. I read deep into sleepless nights, and immediately upon finishing one book, started another before turning off the light. I needed the illusion of required tasks to fill the abyss that loomed over my next day, week, month. The line between depression and anxiety blurred. And even though I no longer believed that therapy or psychopharmaceuticals offered anything to me, sometimes I felt so lost and unable to find a way through, I returned. To talk, and more talk.

A psychiatric diagnosis

is a reflection of the society

that ascribes the label.

One of my iterative searches—in my Fifty’s now, wondering when the hell life would ever start to smooth roll—led to with a therapist who practiced CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. The gist is: thoughts influence feelings; we have (at least some) control over our thoughts; therefore by directing our thoughts, we gain mastery of our feelings. CBT struct me as cookie-cutter, more pop-psych than careful analysis. However, over our allotted eight sessions (plus assigned homework), several things became clear. First, all my previous talk therapy, premised on the notion that mine was a unique case of singular mental struggle, simply resulted in circular conversation. Second, CBT was practical: I could actually apply what we discussed in therapy to my life beyond. I reported concrete examples of catching runaway thoughts, slowing them down, and in the process, calming my feelings. Third, CBT played to my strengths. It’s a structure, a discipline, it lends itself to study. And if there’s one thing I’m good at, it’s studious discipline. When I applied the same skills that enabled me to escape my family and rise in stature, I yielded something more important: a deeper understanding of me.

CBT aligned with other aspects of my life at that time: my emerging yoga practice; exploring meditation; the conscience decision to cap my career. I still felt anxious, but less often descended into depression. I still responded to mental agitation with hyper-action, but my busyness turned inward, channeling energy into personal enlightenment rather than professional perfection. I became more comfortable with my introverted nature, neither needing nor wanting as much social life.

I’d never contemplated retirement, but when intriguing options presented, I stopped working. At age 58. Unstructured time had always been a challenge, but self-motivation kicked in. I volunteered, many gigs. I read, all variety of topics. I travelled, very slowly. I wrote: one book, then another; a play, then another, and another; and so many blog posts. For nearly a decade, I faired pretty well. Conscious adherence to the discipline of CBT helped me manage my life.

Then our nation grew ugly, isolated and divisive; and a pandemic hit. And the diligence required to sustain equilibrium became too great to sustain.