Paul E. Fallon's Blog, page 20

November 2, 2021

Death of a Family?

October 28, 2021

It’s after midnight. I cannot sleep. I rise from my thrashing, flame on the computer, and spill my thoughts.

My sister-in-law is lying in a hospital bed, 2000 miles away. Body temperature lowered to 75 degrees. In hope that when the medical personnel warm her up she will come back to life. In some form. Six minutes without oxygen is a long time. That’s the length of time her heart was starved. The medical jargon is convoluted but the facts are simple. Julie teeters on death. Complications from COVID.

Julie’s 64 or thereabouts. After-midnight stats are unreliable. She’s beautiful. Got this dimple squish in her nose that struck me odd when we first met, forty years ago. Until it seemed unique. Then distinctive. Her love of music and her positive outlook is astonishing. She also bakes killer cinnamon rolls. A dozen years ago, she abandoned her Eighties’ mass of curls for a blunt cut and I realized—wow—this woman’s come into her own. That’s when I moved past loving Julie because she’s my sister-in-law, and just starting loving her. No adjectives or obligations attached.

My brother Bill’s text about his wife arrived last morning, along with a group email from my sister. I was soon added to a thread daughter Jessica began. Jess’ first message described how Bill’s COVID came on first; he’s already been in and out of the ICU.

Anger tornadoed up and through me. My head pulsed. I could barely finish reading. I took deep breaths, dozens of them, typed out a reply, and then opted out of the thread.

“Thank you for letting us know. I am so sorry that Julie is in such a precarious state. She’s so lovely; I have always been fond of her grace and devotion. I am doubly sorry because we all know you and Julie could have minimized, or even prevented, this from ever happening. By denying sound science, you’ve deepened the tragedy.”

How could I be so hard-hearted during this fragile time? I hit ‘send’ and let the repercussions fly.

I mind my own business; don’t quiz anyone of their vaccination status. I got my two shots, wear a mask indoors, stay six feet away from everyone. I don’t like it, but it’s not all that hard. When recommended precautions evolve and change, so do my behaviors. This is a new, virulent disease; our understanding continues to unfold. I could still contract COVID, of course. No one’s guaranteed immune. But if I do, I believe I’ll find solace in knowing that I took the recommended precautions for myself and my community.

There are a few things we know for certain. That if you are seventy with a history of respiratory disease, as my brother is, you present a high risk. That if you bring COVID home, it’s easy to spread. That if you’re vaccinated, the risk of getting COVID nosedives, and if you suffer a breakthrough case, it’s more likely mild.

My brother and his wife chose not to get vaccinated. We didn’t discuss it; the information was simply conveyed.

I can no longer pretend that whether a person gets vaccinated is a rational choice, deserving a sympathetic response.

So why didn’t I squelch my itch to type, “denying sound science,” and simply send a message of sympathy? Because the image of sweet Julie lying in a cold coma snapped something in me. I can no longer pretend that whether a person gets vaccinated is a rational choice, deserving a sympathetic response. Such silence condones their behavior.

Within a few hours, blowback came. From another family voice. How could I toss out an ‘I told you so’ under the circumstances?

I could disagree with that interpretation of my message. The sorrow of an accident is great, but the grief of a trauma over which we exercise some control is deeper, uglier. But that would be quibbling since, no doubt, I ricocheted blame for Julie’s condition. I extracted it from the sphere of the arbitrary and Almighty. I placed, at least some of her agony, back on those suffering.

The range of humans that flower from a single gene pool is amazing. My immediate family and their offspring represent phenomenal diversity. Aside from being mostly white and altogether too-Irish, we hit just about every demographic point: red, blue; rich, poor; drop-out, Ph.D.; evangelical, atheist; alcoholic, teetotaler; veteran, felon. I’ve always prided myself that, no matter how different we are, we stay in touch. Not every-Sunday-for-dinner-close. Still, I’ve always remained on speaking terms with every member of my family. Even when they’re hard for me to figure out. Ditto when my peccadillos confound them.

But tonight, in the after-midnight blackness, I can’t forecast how that tradition continues. What is the right path for me to be a good person: politely accommodate whatever my family says and does under the banner of family solidarity; or stand true to what I know is true.

I strive to see others point of view. But I cannot, cannot, cannot fathom any reasoning why intelligent people whom I love choose not to be vaccinated against this horrific disease. An inaction of perverse selfishness, cruel to their family, callous to society. If their disdain of vaccination is as strong as my conviction, we enter an arena with no middle path.

In this moment I am so angry at my brother, I’m unable to be a good brother myself. I cannot share his burden. I cannot console. Will I find compassion and generosity in my heart to move past my anger? Will I extend the empathy he and Julie need? Or will my principles provide meager solace? Will my anger fester? Prompt reciprocal anger? Drive a rift that we cannot heal? We are none of us getting younger, and some of us are very ill. No matter what differences have surfaced in the past, we’ve always come together again, in time. Will we come together this time? Or will a piece of our family die?

_____

This piece was written in the early hours of October 28, 2021.

As of November 2, Julie was determined to suffer from generalize brain damage. She is being weaned off her ventilator.

October 27, 2021

A Member of the One Percent

(No, not that One Percent)

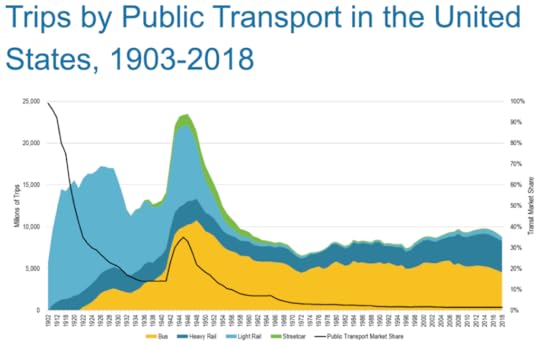

There’s a new crop of one-percenter’s in our nation. Not the one percent who hold ninety percent of the wealth. Rather, a distinctly different group. The one percent who hazard to ride on public transportation. We represent a complete reverse from the turn of the last century, when ninety-nine percent of all travel was on public transit.

Public transit use has been in free-fall for the past 120 years, except for an uptick during World War II when Americans actually modified individual behavior for a perceived greater good. How quaint!

Once the war was over and the consumer economy developed full steam, public transit kept slip-sliding away. The reasons are legion: increased affluence, our love affair with the automobile, disinvestment in streetcars, increased investment in pavement, Madison Avenue’s persistent trumpet of autonomy, the Interstate Highway System, demolition of urban neighborhoods, fossil fuel subsidies, railroad decay.

For most of the 2000’s, public transit use hovered around two percent of all vehicle trips. Most American cities of any size had some sort of subway, streetcar, or bus system, though one-third of all public transit trips occurred in New York City alone. Virtually all systems lost money. Large, older, dense cities like Boston and Chicago, even D.C. and San Francisco, accepted these costs to counter-balance horrific car and truck congestion. And some growth cities, like Denver and Houston, added streetcar systems in the hope of curbing individual auto use. To little avail. Public transit might be charming in Europe, or essential in developing mega-cities like Sao Paulo and Wuhan, but it is an anachronism in most American lives.

Then the pandemic hit and all things communal went from merely annoying to potentially fatal. Public transit use plummeted. For months, the number 75 bus rumbled past my house in darkness; never a passenger regardless of day or time.

For almost a year I stayed off the buses and trains. Then last spring I started to ride again. Not often; there still aren’t many places to go. But occasionally I find reason to commuter rail out to Worcester or subway downtown. The stations are clean and empty. Ditto the trains.

This fall, with schools in full session and more businesses open in person, car traffic around Boston is tense as ever. Every evening news includes pulsing maps of thronged highways. But when I ride the train—sometimes the only person in the car—station after station of commuter lots sit empty.

Today, people abandoning public transportation has little to do with the pandemic: we crowd into restaurants, bars, and stadiums at much higher densities. The T is pretty inexpensive (a trip from Newtonville to Worcester costs me a whopping 11 cents per mile). And though the media loves to dwell on the derailments and delays that occur on our aging, undermaintained system, MBTA buses and trains run with remarkable regularity.

There will be some rebound in public transit use, as car traffic snarls to a halt or gasoline prices hike. But I doubt we’ll return even to the pathetic pre-pandemic two percent number. Once unfettered from patterns, we don’t return to those we never much liked. And Americans really don’t like public transportation.

Which, to me, is a shameful reflection of the worst elements of our society. The decline in our use of public transportation reflects our paramount aspirations: independence; isolation; a literal fear of being in each other’s presence. It’s also a potent example of how easily we abandon any pretense of sustainability. Our disdain of public transportation further normalizes a so-called society in which ninety-nine percent of us are too atomized, too privatized, too fast-moving, too self-absorbed and too self-important to actually interact as a society at all.

October 20, 2021

Dancing with Angelina

Turns and Twirls for People with Parkinson’s Disease

One of my childhood nicknames, Two Left Feet, was all-too accurate. My stout, clumsy body didn’t fit into a family of agile baseball players. Over time I trimmed down and reached average height. But I never acquired the quick reactions required for team sports. Instead, I developed the methodical gait of a distance runner, an oarsman, a dancer. My penchant for poise over speed led me to yoga, and when I became a yoga teacher I took particular interest in people with movement challenges. Folks with weak backs, sciatica, and Parkinson’s. Thus I came upon Urbanity Dance’s community class for Parkinson’s patients.

Angelina arrives ten minutes early, spots my new face, and hustles over to introduce herself. She volunteers her age, phone number, and email address. “Ask me anything you want,” she says before I have a chance to say a word. Angelina moves as quickly as she speaks; her arms and legs twitching with every word.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive disorder that affects movement when the muscle-triggering cells in our brain degenerate due to insufficient amounts of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Uncontrolled tremors are Parkinson’s most familiar sign, but the disease can also produce stiffness, slowing movement, changes in speech, and erratic gait. There is no cure. Medications help people control Parkinson’s, while exercise has proven effective in alleviating symptoms and extending mobility. Physical activities that incorporate pattern and sequence, like Tai Chi, yoga, zumba, and dance, are particularly effective.

From my seat across the circle of five dancers I notice that even when Angelina stops talking, she doesn’t stop moving. Her left thigh swivels from her hip, her shin pivots at her knee, and her foot traces a broad arc across the floor. Before Angelina’s left foot reaches her right, it ricochets back to where it began while her right leg and foot mirror the movement. I try to discern a rhythm in her windshield wiper motion, but random twitches and sudden jumps defy pattern.

Class begins as the teacher, Betsi, invites us to envision Spain. Her arms trace a flamenco rhythm. Right swoop and snap, left swoop and snap. She adds a staccato foot shift and tap, right then left, and encourages us all to follow. We repeat the 32-beat seated sequence—twice—while the keyboard player picks out a zesty melody. By the third repetition, the circle reflects the pattern.

Engaging dance to alleviate Parkinson’s symptoms began over a decade ago when the Brooklyn Parkinson’s Group teamed with Mark Morris Dance Group. Dance for PD has grown to over 100 cities in nine countries. The focus is dance as a pathway to greater mobility, not therapy derived from dance. Participants are dancers, not patients. Teachers are dancers, not therapists. Classes take place in studios, not clinics.

Betsi begins a series of languid arm movements; elegant arcs reach out and up, in and down. Within moments we coalesce into unified motion. I notice Angelina’s feet are quiet. Not still, yet calm. I wonder how the rhythm, pattern, music and reverie contribute to her ease. It would be difficult to construct a scientific study to prove the long-term benefit of this momentary lapse from frenzy, but simple observation reveals that in this moment, Angelina assuages constant uncontrolled movement.

After an hour of chair dancing we stand up, grip the back of our chairs and execute bigger moves based in traditional ballet. Then Betsi calls for a Virginia reel. Angelina claims me as her partner. Her face is determined: dosey-does and hooked arms require a lot of concentration. But when we circle in the correct direction, her resolve melts to a smile.

Betsi signals the musician to improvise. Angelina shouts, “Let’s dance!” Takes my hands in hers. The keyboardist fingers a swing beat. She throttles up the pressure in her hand. Angelina’s the kind of woman who likes to lead. But I’m wary of her stability, so I take control. A solid Lindy step: side; side; back step. She mirrors my pattern. I raise my right arm and guide her through an underarm turn with my left. Keep everything close, trace my left hand along her right arm and grab her right-hand firm. She pushes against my strong lead; this girl has dominated many a wedding dance floor. But I am determined on keeping her upright. I guide Christina through another turn, then another. She spins on a perfect axis, her feet land where they need to be. I stop worrying about having to protect her from falling. We just dance.

October 13, 2021

The Universal Charm of Spokes

Lincoln Street in Gardner Massachusetts is mid-way up the hill. Higher than the rows of worker housing that sit tight to the shuttered mill buildings below. Less elevated than the formerly grand mansions of the mill owners above. A solid street of century old dwellings, originally inhabited by foremen and moneymen. Now sheltering a smattering of immigrant families moving up, old-time malingerers floating down. A mid-rung on the American ladder of success. Its Victorian detail sheathed in vinyl siding.

My friend Huguener recently bought a house for his family on Lincoln Street; a 3,000 square foot behemoth. Huguener wants to figure out how to how to make his mark on a place that began life as a sturdy single family, was cut up into four units, damaged by fire, and rebuilt as a maze of purple partitions. There are several potential solutions, but first step requires accurate drawings of the existing condition. I just spent four hours with tape measure and pencil, angling into every corner, basement to attic. It’s great to return to the autumn air, primed to ride my bike ten miles to Wachusett Train Station, and then let the rails roll me back home.

A husky guy with a beautiful dog comes out of the house near my pole. ‘Jerry’ is chatty. He’s lived in the house all his life, except for two years in the Army. He thought of moving on, but then his parents took ill. Now they’re gone. So he stays. The unique particulars of a universal story. Jerry reveals reams of information in the short time it takes to load my pannier and don my helmet. He’s genuinely pleased about his new neighbor, and Huguener’s plans for improvement. The thought races through my mind that perhaps we are making progress. A generation or two ago a Haitian family moving into a neighborhood would trigger white flight. But ideology can’t fester on this glorious day. We’re just a couple of real people having a real conversation in a real place.

I linger in our chat, even as I know I have a train to catch. Finally, it’s time to pedal on. I roll my bike away from the post.

BANG!!!

The loudest blow-out I’ve ever heard. My ears ring. Jerry shouts, “What’s that?” He looks about, leery. “I thought it was a gun.”

I see my tire, in shreds. The tube is slit and mangled around the frame. I have no idea what occurred. I’ve got well over a hundred miles on that tube; thousands on the tire. It rode fine all the way here. Foul play? I look up and down the street. Dismiss that theory.

“Wow, that was loud.” Jerry pulls at his ear as echoes ricochet up and down the street. “What are you going to do?”

“I carry repair tools and a spare tube.” True. Yet I lie. This blow-out is beyond anything my spare tools can fix. I’ll wheel the bike out of Jerry’s sight, pretend to make a repair, and call an Uber.

“You can’t fix that. Let me drive you to the train station.”

“No, I can’t impose.”

“Forget it. I’ve got time and you’re not going anywhere on that.”

An hour later, I’m riding the gentle downhill path in the train from Wachusett to Belmont. October’s passing leaves create a brilliant collage. The day could so easily have been a tragedy. But I’ve learned, when things go wrong on your bicycle, the world responds with generosity.

At Kevin’s insistence I threw the damaged bike into the bed of his pick-up. Along Route 2 I heard about his military experience and his current ailments: described with equal enthusiasm. I shared the triumph in his voice proclaiming how walking his dog helped him lose forty pounds. I offered Jerry money when he dropped me off, well in advance of my departure time (cars and truck go so fast). He refused. Perhaps pouring his stories over my fresh ears is his compensation.

When the train trucked up the hill, a friendly conductor emerged, gave my bike the once over, and motioned me to follow her. She put me in a particular car to ease my exit in Belmont Center. Later, when she collected my fare, we chatted about the book I’m reading. Pressed the boundary of mere transaction with actual conversation.

I have come to believe bicycles are perhaps the world’s best diplomats. No one is ever wary of a person on a bicycle. Ever. People jump to service of cyclists in distress; simultaneously intrigued by our peculiar transport and gladdened at the chance to extend themselves in such a clear yet virtuous manner. The bicycle enables each of us the comfort to express our best selves.

I have hassles ahead; navigating the deformed bicycle from train to home; replacing my damaged tire and mutilated tube. But all of that is later. In this moment, as the yellows and oranges and reds stream in and among the fleeting green outside my window, I am pleasantly satisfied. My near-tragedy triggered not one, but two, memorable interactions. That’s a sweet deal.

October 7, 2021

The Neutral Zone

This time of year the days and nights are even-handed, the temperature is benign, neither too warm nor too cool. A kind of balance that reminds me of a virtue in yoga that I discovered long ago.

After a few hundred classes, the euphoria of yoga wanes. Not enough to make me stop practicing, but enough that my after-class high is diminished, and like a junkie in search of a bigger fix, I yearn for more. Fortunately, more is there. Though instead of manifesting as more adrenaline, ‘more’ reveals itself through greater control, and deeper peace.

In yoga, we embrace what is uncomfortable, settle into it, befriend it. When I rise out of eagle pose at the end of warm-up, when the sweat has started to flow across every pore, I feel dizzy.

I’ve learned to accept the wooziness, to stand still and upright, to allow the spinning in my head play itself out. Experience has taught me that I will not fall; that my equilibrium will sort itself out in stillness; I need not lurch my body in pursuit of more gravity.

I’ve learned that, in standing head to feet pose, I can balance better when I grip the entire connection between my foot on the ground and the one I hold between my hands; a route that extends up through one stiff knee, across my butt, out through my clenched thigh, across the stretched Achilles. My legs find stillness only when I acknowledge their connection to every other part of my body.

As the initial thrill of yoga gives over to greater understanding, I’ve discovered that achieving full expression of a pose, from an accustomed position of standing, kneeling, or lying flat to a yogic position of strength plus balance, includes passing through a neutral zone, a moment of suspended time and mass en route from idle rest to conscious alignment. The neutral zone doesn’t exist at the beginning of the posture, as I extend arms or legs in a new direction. Nor does it exist in its full expression, which must always be realized with maximum effort. The neutral zone is that pinpoint of time and space when forces of momentum counter disequilibrium. When my body is not balanced, yet I do not fall.

The moment casts shadow on Newton’s second law of motion. For even though I move, my mass times acceleration, for an instant, equals zero.

September 29, 2021

Gimme Shelter – 3

A Primer on Housing America

In two previous posts I outlined a brief history of affordable housing in the United States and the current mechanisms for creating more. Still, the gap between the affordable housing supply and demand increases. Is there any way to turn that around?

Part Three: Fresh Strategies for Providing Affordable Housing

There are approximately 141 million housing units in the United States. We added about ten million units over the past decade, which represents continued flattening over time (11 million new units 2000-2020; 14 million 1990-2000; 18 million from 1980-1990). Still, the net increase in the number of housing units outpaces the rate of change in our population (7.4 % increase 2010-2020; 9.7% increase 2000-2010; 13.1 % increase 1990-2000; 9.8% increase 1980-1990). Housing supply siders advocate that if we simply build more housing, prices will stabilize and affordability will increase. Yet, for forty years we’ve consistently added proportionately more housing units than our population increase, So, why do we have a persistent shortage of affordable housing?

Two powerful demographics contribute to the problem. First, family size in the United States continues to shrink. In 2020, the average family size was 2.53 people per household. In 1980, it was 2.76 people. This seemingly small difference (0.23 people per household) balloons to a demand for over ten million additional housing units. Regardless, simple division illustrates that 141 million dwelling units can accommodate 330 million people clustered in 2.53 family units. With ten million to spare. Yes, but…

Vacancy rates stubbornly hold at three to four million units at any time. Over five million units are second homes—vacant most of the time. And housing is simply not as portable as people and jobs and economic opportunity. For every growing city with expensive and scarce shelter, there are a dozen dwindling burgs where houses depreciate and languish, empty. Thus, demand exceeds the number of housing units in places people want to live. The whole situation is aggravated when available housing costs so much more than many can afford. As a result, too many people spend too much of their income on shelter.

Our mechanisms for creating more affordable housing are tepid; our collective will to make safe housing a basic right is feint. Supply side housing advocates suffer the same blinders as supply side economists: the rich simply consume too many ‘benes’ for anything much to trickle down. Forty years of creating more housing than our relative population increase has produced bigger and bigger houses occupied by smaller and smaller families. It hasn’t created more affordable housing.

Revised zoning laws: enabling accessory dwellings; reducing parking; requiring inclusion; are all promising strategies to promote more housing that could be affordable. But if we are serious about generating more affordable housing, we have to think more comprehensively, and more boldly. We have to acknowledge that our housing problems are intricately tied to our economic inequality, our unsustainable consumption; our dwindling sense of community. We need to be as bold as Ebenezer Howard and last century’s Utopian idealists. We need to create housing that will root thriving, sustainable communities.

Three simple ideas.

First, create housing target zones. Incentivize people to move to existing communities with solid housing but declining population: Western New York; Mississippi; Nebraska. The pandemic and the Internet have proven that geography is fluid. True, many people prefer to live in cities. But the right incentives can help revitalize once vibrant towns to be lively again.

Second, promote smaller and more efficient dwelling units through ‘graduated’ real estate taxes. Just like a graduated income tax, a family with a large house, or multiple houses, should pay a higher tax rate on their excessive real estate. Meanwhile, a family with a modest home should pay proportionately less tax, which will help make entry-level home ownership more affordable.

Third, reinvigorate the Utopian notion that creating housing is an opportunity to reflect higher ideals. ‘Affordable’ housing shouldn’t be architecturally stigmatized on the outside, but within, it should experiment with new ways to accommodate family and community. Non-profit and government supported housing should be more congregate in nature, incorporate a range of private and shared spaces, explore how we can all live better with less stuff and more interaction.

Housing in the United States is a direct reflection of our culture, it promotes autonomy, privacy, and consumption. But our culture is environmentally unsustainable, mentally isolating, and physically unhealthy. Let’s reconceive affordable housing. Not as an inferior reflection of what the private market already provides. But as an experiment in preferred ways to live, which the rest of the housing market can then follow.

September 22, 2021

Gimme Shelter – 2

A Primer on Housing America

Last week, I provided a brief, if somewhat snarly, history of affordable housing in the United States. Today, I offer an overview of the strategies and mechanisms available to create affordable housing today.

Part Two: Creating Affordable Housing Circa 2021

330+ million Americans live in approximately 141 million housing units in the United States. Over two million of us live in public housing, 4.7 million live in Section 8 housing, and a smattering live in other kinds of subsidized shelter. Still, there are only 36 affordable housing units available for every 100 low-income households. Almost two thirds of qualified families either pay too much for a roof overhead, or suffer subsistence housing. What mechanisms do individuals, organizations, and governments have to alleviate this situation?

Public Housing and Section 8. Over 3,000 public housing authorities own and maintain the nation’s public housing stock, much of which is now over fifty years old. Housing Authorities also manage local Section 8 programs, which are split between project-based vouchers (the subsidy belongs to a specific housing development, which is owned by a non-profit rather than the housing authority) and portable vouchers, which a family can use to rent an approved unit of their choice. If you are low-income person lucky enough to land either a public housing unit or Section 8 voucher, you pretty much stay put, as wait lists for these opportunities often span more than ten years. The number of new public housing units being built is nil; the number of new Section 8 vouchers tiny. These are steady-state programs, at best, that won’t make a dent in unmet affordable housing needs.

Non-profit Developer Housing. Since the federal government stopped actually creating new housing, non-profit developers utilize a web of economic development grants, housing set-aside funds, tax-exempt bonds, Community Development Block Grants, low-income housing tax credits, and community reinvestment loans to create affordable housing. These efforts probably do more to provide cover for politicians who want to be able to champion the idea affordable housing than actually generate it. The complexity of permitting and financing affordable housing is a significant reason why affordable housing units cost 25% more to bring online than privately financed housing.

Affordable Home Ownership. Over the past fifty years, the rate of home ownership in America—65%— has been pretty consistent. The percentage shifts in a narrow range in sync with economic cycles, but the average barely budges. Unfortunately, home ownership rates for Blacks and Hispanics are well below 50%. One attempt to increase home ownership rates is to provide affordable home ownership opportunities for moderate income people. Financing these programs is as byzantine as rental programs, but the incentives of ownership are strong. However, most of these programs cap a family’s ability to accrue equity and deny passing a dwelling on to their heirs. As a result, they do not provide the same ladder to economic security that people who purchase houses in the private market and pay them off over their lifetime enjoy.

If there is any bright spot on the affordable housing horizon it inhabits a single word: zoning. More individuals and communities are coming to realize that traditional zoning is environmentally unsustainable, increases sprawl, and exacerbates economic inequality. In the 21st century there have been small, yet significant, moves to reverse restrictive zoning. This can be as simple as reducing parking requirements from two cars per unit to one car per unit, thus increasing the number of units a particular site can accommodate. Several communities now allow accessory-units in any district, including single family zones. This allows folks to make in-law apartments, add a small studio, or create a basement rental unit. Accessory-unit zoning can immediately increase the potential number of dwelling units in a community by 25% or more, while spreading them out among existing structures with almost no additional infrastructure.

There are also two zoning trends specifically targeted at creating affordable housing. The most common is ‘inclusionary zoning.’ Inclusionary zoning requires developers to set aside a certain number of units in new projects for moderate income households. The percentage is pre-determined, and is usually a function of what a ‘hot’ real estate market will bear. In Cambridge, MA, where rents and housing prices are sky-high, developers must provide 20% inclusionary units. In a cooler market, like Des Moines, that threshold requirement doesn’t fly.

Inclusionary zoning provides the ancillary benefit of economically integrating housing on a project level. I’ve met enough people who live in subsidized housing to know that some people welcome this, while others prefer to live among their peers, even poor peers. Inclusion in Cambridge is clear: the subsidized units must be within the development. In other cities, like Boston, direct inclusion is optional. A developer can make a ‘set-aside’ payment to an affordable housing trust fund to build housing elsewhere rather than include subsidized units in their project. Thus, the shiny Seaport District of Boston includes almost no apartments for poor people, while Seaport developers underwrite housing in Mattapan and other traditionally poorer neighborhoods.

Another zoning mechanism for increasing affordable housing is allowing more generous development options for projects in ‘overlay’ districts. Cambridge recently created an ‘affordable housing overlay district’ that increases density, reduces setbacks, and lowers parking requirements for any project that is 100% long-term affordable. This makes the approvals and permitting process easier, and increases the capacity of a given site.

Despite a lot of talk about affordable housing in our nation in 2021, our nation’s political apparatus is hardly primed to invest in directly in building housing, and the financing process for affordable housing remains, well, unaffordable. Many housing activists have redirected their focus from pressing for affordable housing to simply pressing for easier development standards, under the assumption that if more housing can be built, housing will become more affordable as a result. This is a logical argument, but smacks of supply side economics, which leaves me justifiably skeptical.

At this moment, we are losing the battle of creating enough affordable housing. Zoning freedoms may offer increased affordability. Will that be enough to address the need? I doubt it. Next week I’ll suggest some other strategies.

September 15, 2021

Gimme Shelter

A Primer on Housing America

A friend recently asked me how we create affordable housing in the United States. It seemed a simple query. Yet, like so many questions, the deeper I delved, the more complex and frustrating it became. Too much for a single blog post. So, over the next few weeks I will offer three perspectives. Today, a brief history of providing housing for folks unable to access the private market. Next week, the current grab bag of ways that government and non-profit institutions create affordable housing. Round out September with ideas about how we can create more housing and stronger communities by reimagining the entire situation.

Techwood Homes Atlanta, GA 1935

Techwood Homes Atlanta, GA 1935Part One: A Brief History of Affordable Housing

Before there was ‘housing’ there were simply houses. On farms, in towns, hand built by their owners or erected by developer/builders before those labels acquired their present meaning. As cities grew, building, leasing, and maintaining dwellings became different functions from occupying them, whether you lived along a London Crescent or in a Dickensian slum. Neither The Crescent (exclusive by design) nor the slum (completely lacking in design) fit our current notion of ‘housing:’ intended for the masses yet consciously designed in a manner supposedly morally uplifting. In reality, ‘housing’ is simultaneously generic and architecturally obvious; no one who can afford a private domicile chooses to live in it.

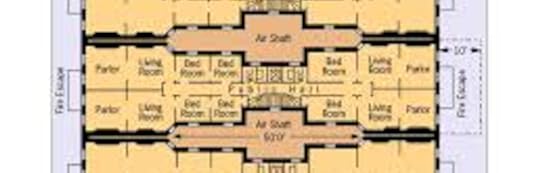

The earliest examples of what we now call ‘affordable housing’ are New York City’s 19th century tenements. A city laid out on simple grid of regular building lots, teeming with newcomers clamoring for shelter, was the perfect place for repetitive blocks of mass housing. Dense, unsanitary, ill-ventilated. These buildings prompted the Tenement Laws of 1867, 1879, and 1901. Although there were already building codes in some US cities proscribing structural integrity and fire-safety, the tenement laws set standards for ventilation and sanitation that acknowledged the connection between private habitat and public health. These well-intentioned laws inadvertently established an operating principle of housing: navigate the law for maximum profit. Before the Tenement Law of 1879, dumbbell apartment buildings did not exist. But once entrepreneurs discovered how that shape met the letter of the law at optimal density, the dumbbell proliferated. Until the Tenement Law of 1901 outlawed such buildings that provided light and air in theory, but were unsafe and unsanitary in fact.

Dumbbell Tenement

Dumbbell TenementIn the twentieth century, utopian theorists turned their focus from rural ideals to urban opportunities. Ebenezer Howard and other reformers envisioned ‘garden cities’ where light and space, commerce and leisure entwined. Some failed. A few, like Forest Hills, New York, prospered too well and became instantly affluent. Still others, such as Sunnyside Gardens (also in Queens) retained communitarian ideals for a long time. Although the Garden City movement was too small and too elitist to generate housing on the scale required by 20th century America, it was instrumental in prompting the first zoning ordinances (Los Angeles, 1908; New York 1916; model ordnances by the 1920’s). Zoning restricted development more comprehensively than mere tenement laws. It also established two key attributes to our nation’s development, albeit without stating either directly: density is bad; racial segregation is good.

Forest Hills, New York

Forest Hills, New YorkThe first affordable housing project built by the Federal Government (1935), Techwood Homes in Atlanta Georgia, established the blueprint for economic, architectural, and social standards for a generation of public housing. Techwood Flats was a fourteen-block neighborhood just north of downtown Atlanta, sandwiched between Georgia Tech and Coca-Cola headquarters. The haphazard collection of wood-framed houses, many dating from the nineteenth century, was home to over 1600 families, one quarter of whom were African-American. Atlanta businessmen wanted to remove this blight. The federal government provided $2,375,000 to demolish the neighborhood and construct 604 units in its place. The faintly colonial brick buildings zig-zag across open lawns, thereby establishing one hallmark of public housing: its form does not follow conventional street frontages and is therefore easy to identify as ‘housing.’ The second hallmark: all 604 units were reserved for white people. Later, a public housing project designated for Blacks was built further out of downtown, but by that the time, the original residents of Techwood Flats were long scattered.

This prototype of public housing, in form and disruption, exists all across the United States. Public housing did not carry immediate stigma; being poor was a reality for too many of us during the Depression and through World War II. The apartments were sanitary, with many windows and cross-ventilation. Amenities like full bathrooms, overhead lights, and bedroom closets were welcome. However, during the 1950’s and 1960’s housing projects got larger and larger and became receptacles of people left behind in a society of increasing affluence. In large cities, like New York, Chicago, and St. Louis, wide lawns fronting brick townhouses were abandoned in favor of high-rise buildings. Hives of the have-nots.

Pruitt Igoe Project St. Louis

Pruitt Igoe Project St. LouisPresident Lyndon Johnson inadvertently spelled public housing’s doom when he signed The Fair Housing Act of 1968, which ended segregation in public housing. Richard Nixon’s HUD initiated the Section 8 program, in 1974. The program touted the virtue of the enterprise (and sidestepped integration) by providing vouchers toward private-market rents. Thus began the transition from the federal government creating housing, to the federal government subsidizing housing provided by others, to eventually providing tax credits, dedicated subsidies, and loan guarantees that pretty much ensure everyone involved in developing affordable housing will get their cut, even as creating affordable housing units grows complex and expensive.

At present, the cost of creating an affordable apartment unit is about 25% higher (2016 national average just above $200,000) than a unit in the private market. In pricey states, like California, this cost can exceed $450,00 per unit. In pricey cities, like San Francisco, an affordable unit can cost over $1 million from concept to occupancy.

In the meantime, through the 20th century, zoning restrictions grew ever-more restrictive, allowing fewer units, requiring larger lots, deeper setbacks, and more parking. All of which made housing in general more expensive, and affordable housing more scarce. A general rule of thumb is that families should pay about 30% of their income for total shelter costs: rent or mortgage, maintenance, and utilities. Yet, entering the new millennium, over 40% of all renters paid more than 30% of their income on housing and 20% paid more than 50% of their income for shelter.

Affordable Housing San Francisco

Affordable Housing San Francisco What are we doing today to alleviate the affordable housing crisis? Is it effective? Check in next week.

September 8, 2021

History as Fact—and as Gap

Whitney Plantation, Louisiana

Whitney Plantation, LouisianaWithin a few moments of Clint Smith’s recent Harvard Radcliffe Institute Book Talk about How the Word is Passed, I was fully won over by the man and his message. Mr. Smith is a 33-year-old poet and scholar drenched in wisdom deep as it is nuanced. His book chronicles seven places he visited, and the people he met, in search of reckoning the past and present impact of American slavery. I’ve never encountered legitimate anger coupled with such compassion.

How the Word is Passed appeals to me in multiple ways. The book is architectural: Clint’s descriptions of the beauty, the grit, the cramped, and the expansive center us in these places. The people he encounters resonate with their setting, whether generationally-bound locals or passing tourists. His writing is lyrical. He pinpoints the passion and perspective of every individual he encounters. Then gently casts a shroud over their given truth. Some people, some positions, are more generous and humane than others. But no one is completely bad, nor completely good. Mr. Smith grants each human their fallacies, with a dollop of grace.

The seven sites are a junket through the familiar and exotic. I’ve been to two of the locations (Monticello and Whitney Plantation), and was reassured that Mr. Smith’s perspectives resonate with my own. His experience in two other places I know, New York City and Galveston, provide fresh information and insight of each. I only know of Angola Prison and Goree Island from films, and appreciate how Clint’s descriptions gave them fuller life.

Statues of slave children at Whitney Plantation

Statues of slave children at Whitney PlantationThe remaining place the author visited, Blandford Cemetery in Petersburg, VA, was completely new to me. Yet it merits his meatiest essay, the very heart of the book, and best illustrates Mr. Smith’s compassion. He witnesses a rally in honor of Confederate dead. The man stands out, for the obvious reason that Clint Smith is Black. Afterward, he engages in conversations with mourners and reenactors and finds a way to appreciate humanity on all sides. The writer presents facts of history that clearly connect the succession of Southern states to the preservation of slavery. Then he outlines the evolution of post-Civil War narratives that whitewash slavery’s centrality from Reconstruction through today. Yet, he acknowledges the appeal for twenty-first century men to honor the truths that generations of forefathers extolled.

“What would it take—what does it take—for you to confront a false history even if it means shattering the stories you have been told throughout your life? Even if it means having to fundamentally reexamine who you are and who your family has been? Just because something is difficult to accept doesn’t mean you shouldn’t refuse to accept it. Just because someone tells you a story doesn’t make that story true.”

The central thesis of How the Word is Passed is recited in the opening essay, Monticello. Not by the author. Rather by a tour guide at Jefferson’s plantation. David Thorson is a white male, retired after thirty years in the US Navy. He guides the tour that highlights the life of slaves at Monticello. The people owned, and bought, and sold by the the man who declared “…all men are created equal.” Mr. Thorson is the perfect mouthpiece for Mr. Smith’s thesis, because our image of a white retired military Virginian does not correlate with a tour guide who reveals the underbelly of our third President.

“I think that history is the story of the past, using all available facts, and that nostalgia is a fantasy about the past, using no facts, and somewhere in between is memory.”

David Thorson, tour guide, Monticello My tour guide at Whitney

My tour guide at WhitneyAs Clint Smith journeys to seven places particular to slavery, all the way back to Goree Island where thousands of Africans left their shore and their freedom forever, he offers us myriad perspectives. Northern ‘reformers’ who kept their thumb in chattel’s bounty. Eugenicists who proclaimed the scientific superiority of Caucasians. European colonizers who stirred unrest in Africa to generate slaves. African rulers who sold their fellow human beings. Slavers who landed as little as 30% of their original cargo. Plantation owners who bought them and sold them and whipped them and mated them and worked them again and again and again. The liberation of the original Juneteenth. The repression of present-day Angola Prison.

Toward book’s end, Mr. Smith returns to David Thorson’s statement, and relates it to the gaps that underlie our inability to reckon with American slavery. Gaps of information, when one side crafts selective stories and the other side’s story is barely even recorded. Gaps in understanding when we disagree on such fundamental questions as: Who is fully human? Who is granted fully human rights?

How the Word is Passed offers history that is rich and nuanced. It suggests that we can learn it, appreciate it, and apply it toward a more equitable world. Only not through slogans and sound bites. The closing sentence is daunting as it is inspiring. “It is no longer a question of whether we can learn this history but whether we have the collective will to reckon with it.”

September 1, 2021

Hope is a Discipline

“Hope is not an emotion…hope is not optimism.”

– Mariame Kaba, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us

“Optimism is a state of mind in which you are hopeful that things will turn out well.”

– William J. Knaus, Ed D, The Cognitive Behavioral Workbook for Depression.

“In the world we live in, it is easy to feel a sense of hopelessness, that everything is bad all the time, that nothing is going to change ever…I understand why people feel that way. I just choose differently. I choose to think in a different way, and I choose to act in a different way.”

– Mariame Kaba, We Do This ‘Til We Free Us

“Unfortunate events happen, but the fatalistic resignation of hopelessness thinking is optional.”

– William J. Knaus, Ed D, The Cognitive Behavioral Workbook for Depression.

I suppose that anyone who occupies his long summer days reading Mariame Kaba and working his way through a self-help book to combat depression is, by definition, a man of hope.

Ms. Kaba’s insights into social justice and prison abolition are generous and humane. She commands us to action yet simultaneously recognizes that the timeframe of equity is measured in decades and generations.

As for the self-help, depression is my longest and darkest acquaintance. A foe so comfortable it too often feels like a friend. It feeds on me, as on so many others, during the disconnection and isolation of pandemic. But have you tried to get an appointment with a living breathing therapist lately? That is hopeless.

I first began seriously thinking about hope during my time in Haiti. How people who possessed so little—by our measure—seemed altogether more satisfied than most Americans. Haitian joie de vivre is rooted in an odd combination of resilience and dependence. Life in Haiti is hard. No one is presumptive enough to think he can make it on his own. Yet, Haitians are resourceful in crafting lives on an over-crowded, thin-soiled, institutionally bereft island. We Americans are their polar opposite. Quick and fierce in proclaiming our independence even as we navigate a thoroughly interdependent society.

The laughing and singing I heard each evening as I walked home in Haiti got me thinking, and reading, about hope. At a first order of magnitude, hope is indirectly proportional to affluence. The more you have, the more you have to lose, the more you’re annoyed by inconvenience, the less satisfied you become, the less goodwill you harbor toward the future. The highest levels of hope on this earth are reported in Africa. I don’t know the science behind that declaration, but I endorse its validity. Hope is nourishing, and it’s free.

Nearly ten years later, during pandemic summer 2.0, I encounter the idea: hope is a discipline; and its corollary: hopelessness thinking is optional. I’ve been running these notions round my head because, upon first absorption, they don’t jive. How can hope (all light and spirit) be a discipline (all serious rigor)? How can ruminating on the intractable problems of our era and the demons in our private lives be optional?

By choice. Our thoughts, our feelings, our physical health feed upon and reinforce each other. When we choose hope, it reframes our perspective. We acknowledge our despair, our limitations. We accept that our influence on this planet is tiny and short-lived. Yet our presence, our influence, still has meaning.

So, we seek out the beneficent. We lead with trust. At first we must force ourselves to thinking that’s so contrary to our cynical society. Until hope becomes a pattern. Then a disciple. And we emerge into a more positive way of being.