Paul E. Fallon's Blog, page 21

August 25, 2021

One Night in Tallahassee

I embrace Universal Basic Income and envision the end of work as we know it

“Look at you; look at what you’re doing. You’re engaged, you’re learning, you’re sharing. I think that’s useful. We don’t call it work because you’re not doing it for money.”

The Couchsurfing app connects me with Amre. I arrive at his spartan apartment in Tallahassee, Florida with a six-pack. Amre cooks couscous. We sit on his sofa and eat from plates on our laps. The guy hasn’t got a table. In the morning I’ll be gone. We’ll likely never meet again.

“UBI promotes the creative stuff you’re doing. In its purest form, UBI covers essential expenses. You receive it simply for inhabiting the earth.”

As our evening progresses, Amre enumerates the merits of Universal Basic Income. Other folks I’ve met along my journey have used the term, but no one’s explained it with such fervor, or clarity. I’ve been riding my bicycle fourteen months now. Over 20,000 miles. Meandering through all 48 contiguous states. Hundreds of people have invited me to share dinner and shelter. I ask every one of them the same question: “How Will We Live Tomorrow?”

“I like the ‘we’ in your question. It implies community. No one in our social system is asking this.”

Amre embraces my query with vigor. Or perhaps I’ve just become expert at discussing it, this late in my adventure. December, 2016. Florida is my terminal state. I plan to reach Jacksonville by the 21st; then Amtrak up the East Coast to be home by Christmas.

“We are living abnormally.” Amre continues. “It began with the industrial revolution, and has grown more unsustainable ever since.”

Deep and earnest intimacy blossoms between two people who come together over hospitality and intention. I offer snippets of personal history: aspirations; children; career. Amre shares immigrant trials that span Syria, France, India, Venezuela, Miami. The guy’s energetic, articulate, intelligent, movie-star handsome. I can’t imagine an IT support job and a rudimentary Tallahassee apartment will mark the end of his story. His perspective is far too expansive.

“We can proceed for one more generation, perhaps. But your children, and my hopeful children, will grasp that we need to change. That we need balance.”

Amre counters my singular query with questions of his own. “What provoked you to this journey?” How has it changed you?” “What advice would you give to your younger self?” I understand that ‘your younger self,’ means when I was Amre’s age. Our complementary souls mark beginning and end points of American’s central phase of life: the work years. Amre, in his twenties, formal education complete, is embarking on career. I’m in my sixties, retired, liberated from the pursuit of compensation. I am his role model: unjaded survivor of the work world, curiosity intact. He is my inspiration: young man with broader vision than I held at his age.

“Some things will have to be forced in order to achieve necessary balance. There will still be wars and struggles for power. But I am optimistic. I can see that we will get there.”

I didn’t plan my crisscross of America to correspond with a great political drama: the Presidential campaign of 2016. It just turned out that way. I pedaled throughout primaries and conventions, rallies, and debates, while people’s definition of ‘we’ became ever-smaller; their vision of tomorrow increasingly myopic. As our nation spiraled into cynicism and mistrust, I came to see myself as an antidote to our culture of fear: a vulnerable guy; traveling slow; embraced by thoughtful, friendly people, open to exchanging ideas. I found accord with most everyone I met. But I particularly appreciate newcomers, like Amre. Immigrants convey the most prescient insights. They express unbridled faith in our founding ideals. Such is the value of outsider perspective.

“I thought everyone here would be very hard-driven. I don’t find that at all.” Amre notes. “Yet, I believe America still has the idea of freedom. It still has more opportunity than most of the world, much more than Old Europe.”

Amre doesn’t consider UBI a welfare program or political gimmick. He explains the relatively small portion of the public budget it will consume, the bureaucracy it will unspool, the collective trust it will inspire.

“I do not believe this will make people lazy; they will be energized. If everyone who makes a non-economic choice can be happier, then universal income will lead to greater creativity and happiness.”

Amre’s enthusiasm for UBI reinforces other concepts I encountered during my pilgrimage: the exponential labor savings of automation (Detroit); the connection between consumption and sustainability (New Mexico); the ongoing quest for equity (Lower East Side). Over the past 400 years, capitalism has been instrumental in raising life expectancy and living standards. But it’s also thrown humanity and nature out of whack. Capitalism is predicated on continuous production, which yields continuous growth, which results in continuous despoiling of our planet. It straightjackets a person’s value as their capacity to work. Today, it takes so few people to produce so much more than we need. Which is why we must rethink capitalism. Which fundamentally means: rethink income; rethink work. Amre opens my eyes to how UBI acknowledges every human’s intrinsic value by accommodating basic needs independent of paid labor. As such, it offers a path to ease away from capitalism’s destructions.

Five years have passed since my evening with Amre. Much has changed. Although UBI hasn’t been instituted in its purest form, it is the undergirding idea behind the recovery checks issued during the pandemic, and as well as the recently expanded Child Tax Credit. We haven’t eliminated work, though the pandemic and Zoom have modified many jobs beyond traditional definition.

Still, the major mind shift required to redirect from constant growth towards common equity looms distant. All politicians of both parties still clamor for economic growth instead of advocating economic balance. Work is still seen as the primary measure of an individual’s worth.

Universal Basic Income will not eliminate work. Rather, it will make work a choice. Those who might be content with a simpler life can opt to pursue non-economic dreams. Others will choose paid work in order to gain creature comforts. However, having that choice will change the nature of work forever. Rote, low-wage, routine jobs will be automated. Those jobs that remain will be more creative and engaging.

Beyond transforming our attitudes about work, UBI will reframe other challenges. Income inequity could actually increase, though I maintain inequality that accommodates basic needs and offers individual choice is fairer than the economic insecurity many face today. UBI will (hopefully) slow the economy down according to traditional measures, as some opt out of the workplace; make things rather than buy them. A desirable step toward a more sustainable planet. But the most important thing UBI will do, on an individual level, is release us from fear that our basic needs will go unmet. We will be free to pursue whatever makes us most fully human.

Four hundred years ago, the dawn of capitalism and ensuing industrial revolution invented our current definition of work as an activity divorced from the rest of our daily lives, whose purpose is to generate money to survive. The twentieth-century refined that concept; as work conferred status and influence, and defined our identity. In this century, let’s champion the technology that enables us to provide basic needs for all. Let’s reimagine work as a choice.

I’ve never seen Amre again. But the grand vision of UBI he offered me one night in Tallahassee holds clear and bright.

August 18, 2021

Nobody Wants to Work Anymore…a Tale of Three Cities’ Trash

“Nobody wants to work anymore.” I encounter the phrase every day. From retiree’s impatient for the waitress to take their order. From people complaining insufferable wait times to be connected to a customer service rep. In media reports of worker shortages in every sector, agriculture to manufacturing.

Perhaps I need to stop hanging around folks who still use the term, “waitress,” and avoid the over-sixty crowd who reflexively chant, “I put in my time.” Still, the phrase, “nobody wants to work,” transcends ideological bounds. Conservatives blame pandemic largesse of extended unemployment, eviction moratoriums, and relief payments. Liberals complain that the shortage of ready workers further erodes our global economic position.

When I hear, “Nobody wants to work anymore,” I keep my mouth shut. Because I totally disagree. People want work. Work that’s engaging, creative, meaningful. Work that lifts their talents and abilities. Which is rarely the work advertised.

Throughout history, pandemics have triggered major changes in how humans organize labor. I’m hoping the current pandemic will do the same. After fifty years of wage stagnation and unravelling safety net, Americans are no longer interested in working for the conditions that companies offer. I envision two distinct yet connected threads of how work will evolve in a post-pandemic world.

The first, obvious, change recalibrates the balance between owners and laborers. Wages will rise, benefits grow, working conditions improve. Management won’t like it and inflation could result, though we might actually make a dent in our nation’s obscene income discrepancies.

The second, less likely but more valuable change, will be that fewer people work. We will (finally) acknowledge that the number of workers required to sustain a basic standard of living is diminishing, while the excesses of our ever-increasing consumer spiral is rending our planet unfit for human habitation. The number of jobs will decrease until, ideally, work becomes optional.

Consider a case study that illustrates three models: current state vs. higher wage and benefits vs. fewer workers. Consider an industry we all use, all need, and all hate to think about. Consider trash removal.

“A putrid problem is piling up in Webster, Massachusetts.” Thus begins NBC-10’s local news story that Republic Services has failed to pick up the trash in the city in over two weeks. Irate neighbors, potential rodents, rising temperatures, even a hint of lawsuit portray the $23-Billion corporation in an unfavorable light. Republic’s requisite company statement tacked onto the end of the expose doesn’t much help. “Many industries are facing staffing challenges at this time, and the recycling and waste disposal industry is no different …” In other words, nobody wants to work anymore.

I investigated Republic Services offerings to new drivers. The Auburn office, which services Webster, advertises a 5K bonus. Average driver salaries are just north of $21 per hour. There’s a nice list of benefits, though several online comments decry that most of the benefit costs must be borne by the employee.

Judging from the trash piling up in Webster, offering someone $45,000 a year to pick up trash isn’t enough incentive to put up with the flies and the smell and the mess.

Where can a trash hauler do better? Consider Cambridge, my hometown, where a trash truck with a crew of three collects whatever I put at my curb every Tuesday like clockwork. Ditto the compost truck, the yard waste truck, and the recycling truck. Cambridge’s sanitation workers, members of the Teamsters union, earn over $24 per hour, with premium benefits. A noticeable notch above what Republic offers. The city places no limits on the number of bins I can put out, removes any furniture, even takes used appliances with a pre-arranged tag. Cambridge provides a high-touch sanitation service that one of America’s most affluent cities can afford, and I’m happy to pay for service so good.

What does sanitation look like with fewer workers rather than premium price? Nearby Watertown deals with its trash more efficiently, though it requires more resident effort. Watertown’s trash and recycling are also contracted to Republic Services, though I doubt NBC-10 will report from there, as I’ve witnessed that Watertown’s system works. The city provides specific containers for trash and recycling. Their website outlines strict instructions for how to place containers along the street. A lone driver navigates the side-loading truck, a lever-arm mechanically lifts each container and empties it into the hopper. A solo driver/collector is less flexible than Cambridge’s three-person crew. But it’s an appealing approach to collecting trash with fewer people, more machinery.

Trash collection offers but one example of post-pandemic work trade-offs. The current state, Webster, is broken because people simply won’t work for the wage/benefit packages of the past. Some individuals or communities, such as Cambridge, will pony up more money to retain a high level of service. Others, like Watertown, will incorporate mechanics/robotics to minimize human labor.

The problem is not human resources. We have enough people to pick up our trash—provided we boost their pay. We also have technology if we prefer to collect garbage with fewer workers. More likely, the problem is human expectation: we want a Cambridge level of service at a Webster price point. Or what to do with sanitation workers who are displaced by mechanical arms. How will we value fellow human beings when they’re no longer needed to drive the economy, even if only to pick up our garbage?

Creating a better world of work requires that we shift from the mantra of full employment to one of worthwhile employment. To decouple human stature from mere capacity for labor. To provide a basic standard of living for everyone regardless of whether they ‘work.’

This will have profound ramifications. We will have to shift our unsustainable narrative of economic growth to one of economic balance. Some, wishing to remain untethered from employment, will choose to live in community, share our cars, tend our gardens, cook our own meals. Live lives that don’t increase the GDP. When we automate the work ‘nobody’ wants to do, we can focus on more satisfying pursuits and celebrate what we create through that liberation.

“Nobody wants to work anymore,” is thin-veiled code for “Nobody will do menial tasks for the pittance I’m willing to pay.” We have the capability to get rid of menial tasks and redefine work as the pursuit of human potential. I am pretty sure everybody will want to do that.

August 11, 2021

Tower of e-Babel

Five thousand years ago, give or take a few centuries, the people of the earth, speaking in unified tongue, got together and decided to build a tower to reach the heavens (Genesis 11:1-9). God, ever wary of humans getting uppity, put an end to their folly with two neat tricks. First, she made their utterances incomprehensible to each other. Then, he scattered people across the face of the earth. Thus marks the beginning of widescale human interference with the natural order, and our inability to understand each other.

Fast forward five thousand years, give or take a few centuries, and human hubris bristles anew. Seven point eight billion of us completely dominate the planet. And though we speak over 6500 languages, our communication is seamless as in the days of Babel. Thanks to Google translate and its technology cousins, we can bridge any communication gap.

So why are we suffering through an era of unprecedented miscommunication? Because, as humans are wont to do, just as we smooth out one problem—translation—we create another confusion—format. Back in the days of Babel, we had only the human voice. Plus a bit of stone chiseling. Over time we developed paper and ink, which Guttenberg refined with the printing press. This led to the hard bound book, the penny rag, the Sears Catalog, and Trader Joe’s Fearless Flyer. The more paper we printed upon, the less valuable it became, until the only folks who will mess with it hang out at US Post Office. They deposit junk in our mail slots, which we recycle, unopened.

These days, real communication is electronic.

Whoever invented email is my friend. I think it was Al Gore. Anyway, no surprise to anyone that I’m an email kind of guy. Email is perfectly suited to a sixty-six-year-old guy finnicky about writing stuff down, documenting conversation, and keeping it all in order. I keep my Inbox trim, ruthlessly ‘unsubscribe’ from junk, yet maintain years of missives organized in dozens of subfolders. It’s doubtful I will ever need to retrieve any of them, but infinitely reassuring to know that I can.

I read, save, delete or otherwise deal with every message I receive by email. Texts are more problematic. If my phone beeps when I’m out and about, I forget about it. The message gets queued down. It disappears from my consciousness as well as my contact roll. Opportunity lost.

And then there are the other formats. Instagram. Snapchat. Facetime. Zoom. Google Docs. iMessage. eye-yay-eye. No way I can keep up.

Of course, the affinities are flipped for folks who made their primal scream just as ‘You’ve Got Mail” dominated the multiplex. In the recent article, “Could Gen-Z Free the World from Email?” Adam Simmons, age 24, proclaims, “Email is all your stressors in one area, which makes the burnout thing so much harder. You look at your email and have work stuff, which is the priority, and then rent’s due from your landlord and then Netflix bills. And I think that’s a really negative way to live your life.”

I can agree with Adam that an inbox full of work tasks and bills is a negative way to live. Unfortunately, since Adam doesn’t do email, and I don’t Tweet or Signal or Google Group or Substack or use whatever cool format post-Millennials favor this week, I doubt we’ll ever have the opportunity to share a meaningful moment of cohesion on the matter.

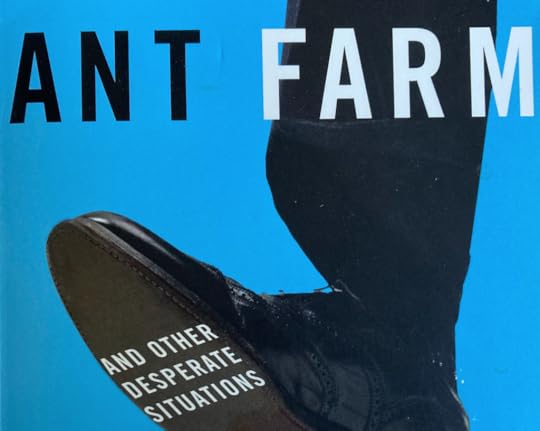

August 4, 2021

Education…huh…yeah…What is it Good For?

When Edwin Starr released his anti-anthem “War (What is it Good For?)” in 1970, the number of high school graduates in the United States heading off to college was near peak, just north of 50%. The percentage had been growing for over twenty years, thanks in large part to World War II era perks for veterans.

For the previous three hundred years, college had been, more or less, the province of gentlemen, with all the privilege and snobbery that F. Scott Fitzgerald reveals in This Side of Paradise. College cost a relative lot of money and prepared mostly white men for soft-hand positions like the ministry and law, or even loftier pursuits of literature or philosophy.

The GI Bill shook all that up, making college accessible and affordable, just as our thrall with a technology-based consumer society ratcheted the demand for engineering and science. College became more than a place to refine etiquette and noodle your brain; you could also learn useful stuff. Slide-rule meccas like Cal Tech and Purdue flourished. As did niche start-ups, like Berklee School of Music, whose mass-churn business model embraced music’s electronic potential and, within two generations, grew from concept to the largest music school in the world.

Through the 1950’s and 60’s Americans embraced the aspirations of accessible higher education. College was a passage to a better life that provided marketable skills and made us better-informed individuals and more engaged citizens. We had the best institutions in the world, we were the best-educated citizens: indisputable facts (to us) at the time. Neither of my parents graduated from college, but each of their children grew up assuming that we would. It was our honor, even our patriotic duty, to participate in the privilege.

Back to “War (What is it Good For?).”

In 1970, a more immediate benefit of attending college held sway: student deferment draft status to avoid Vietnam. Going to college became a short-term strategy as well as a long-term objective. But the disparity between those who trudged through the rice paddies and those who loitered within ivory towers established the fault lines that define our culture wars to this day.

By autumn 1973, when I was a college freshman, American troops in Vietnam dwindled. The draft was gone. College enrollment declined proportionately. Diminished as well, was college’s aspirational notion. Upper classmen whose political protests had shut down MIT in 1970 and again in 1972 dazzled my emerging awareness. Yet no such activism occurred during my four years on campus. And by the time I graduated in 1977, the riskiest thing a student did was apply to business school.

Also, during those four years, the cost of MIT tuition exactly doubled. A walloping acceleration that’s kept on climbing ever since. Over the last forty years, college costs accelerated at more than double the rate of inflation.

Today, college is big business. Expensive to attend for reasons beyond the hefty ‘list price.’ Expensive because the amount of state and federal student aid has diminished (students and families paid 33% of the total cost in 1980, versus 51% today). Expensive because families contribute proportionately less of that cost, bumping up the amount students borrow. Expensive because student loans are more costly than the direct-federal loans of the 1970’s. (Whereas my 3% interest did not begin to accrue until after I completed college and national service and graduate school—a period of eight years—today’s students accumulate interest from the date they sign the note, often at higher rates.)

As the sticker price of college ticks up, tales of diploma-less success proliferate. The business case for college is skinnier than it was fifty years ago. Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg are billionaire dropouts. Venture capitalists underwrite genius ideas fresh from high school. If going to college can’t trigger our first million, why waste four years piling up that debt?

There are two fundamental flaws with current arguments against going to college. First, though college is not as ‘lucrative’ as in the glorious 70’s, it’s still a way smarter investment than not. For sure, a student has to be prudent: early education majors graduating with $100,000 in debt will likely never balance sheet to black. But study after study reveal that college graduates enjoy more financial success (twice the lifetime earning of high school graduates), career stability, satisfaction, longer lives, and overall well-being than their less credentialed counterparts.

Second, and I believe more importantly, are the non-quantifiable benefits of education. To cultivate our curiosity, become more aware of ourselves and our surroundings. To be better-informed individuals and more engaged citizens. Growing up emmeshed in John F. Kennedy’s stirring, “ask what you can do for your country,” I was indoctrinated in the idea that education promotes culture as well as craft. Younger folks, nursed on 1980’s dictums that “greed is good,” and “the government is the problem,” don’t even possess a metric for education as societal benefit.

The United States has never been a nation that particularly values education, certainly not for its own sake. We don’t erect statues of great scholars in our city squares, as seen in China. We don’t elect intellectuals as President, as sometimes occurs in Europe. We value the clever and the rugged over the thoughtful.

To be sure, education in the United States is in precarious shape. It’s too expensive, too irrelevant, too internally focused, yet—trigger warning—too sensitive. It indulges the individual, dismisses the collective, and reinforces our demand of rights over our moral responsibilities. How could it be otherwise? A nation’s educational system is the most direct expression of its values; the cultural glue that welds cohesion. And so in this moment, when what most binds Americans is our vast disagreement, education all too accurately reflects our challenges.

Yet, I do not despair.

“The chief wonder of education is that it does not ruin everybody concerned in it, teachers and taught.” Henry Adams penned those words more than a century ago, decrying the futility of a nineteenth-century educational system increasingly irrelevant to his rapidly changing times. Still, I can’t help but wonder whether his years at Harvard might have somehow informed The Education of Henry Adams, named Modern Library’s best English-language non-fiction book of the 2oth century.

Education will survive the internet, the culture wars, legislated revisionist history, even fascism. It will have to shed the too-often tepid approach of bottom-line driven, special interest pandering colleges. It will have to shake off America’s narcissistic, myopic vision of itself via-a-vis the world. It will have to become more inclusive, so that essays reflecting personal experience, like this one, don’t feature so many pics of white guys.

But I am confident that we will do it. For no matter how long fear and narrow visions of power try to rein us in, ultimately, education is the only thing that expands and enlightens human experience.

War…huh…yeah…What is it Good For? Absolutely Nothing!

Education…huh…yeah…What is Good For? Absolutely Everything!

July 28, 2021

Comrades! Asexuals of the World! Unite!

I recently copy-edited a Guest Opinion essay by Michele Kirichanskaya for the upcoming issue of GL&R (Gay & Lesbian Review). “How Asexuals Got Organized.” I proof read the article. Made a few grammatical notations. Checked out the website for Asexual Visibility and Education Network. Asexual.org. Yep, It’s a thing.

Then I laughed. Out. Loud.

In our current alphabet soup of sexual identity, LGBTQIA+ stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Questioning (old-schoolers like me sometimes mistakenly say Queer) Intersex, and Asexual. We tack on the ‘+’ because, well, we certainly don’t want to exclude anyone from the big tent of identities whose unifying thread is that we are not heterosexual.

Of course, there’s a good chance more letters will be added, as this whole sexual identity business rests on historically recent and shifting sands. Before the mid-nineteenth century, a Lesbian was a person from Lesbos, a heterosexual was a person with “an abnormal or perverted appetite toward the opposite sex,” and the word homosexual had nothing to do with its current meaning. It wasn’t until 1934 that the term heterosexual took on a normative context, until the 1970’s that the terms gay and lesbian came into vogue, and until the 1990’s that RuPaul made it all so fabulous.

Gay…lesbian…trans…the labels occupied a confluence of meanings. Political, to be sure, for people traditionally oppressed. But also fun. They absorbed the gravity of our biologic inclinations, as well as our conscious choice to set ourselves apart from convention. For years after I came out I described myself as homosexual because my life held nothing else in common with what was then heralded as ‘gay lifestyle.’

Now, it’s 2021. Identity politics carves division with surgical precision, and no one’s got even a shredded sense of humor. So, all we have left is a basketful of identities, each stocked with its precious grievances.

Which brings me back to asexual organizing. According to AVEN’s website, an asexual is “…is a person who does not experience sexual attraction.” Okay. Fine. Actually, on a 92-degree July day with 86% humidity, being asexual sounds like a sort of blessing. No chance of getting hot and bothered, when those of us cursed with the urge will only end up wallowing in sticky execution.

Here’s what I don’t understand. Why do asexual folks seek to include themselves in the LGBTQIA+ mix, an umbrella that includes all kinds of peeps whose sexual attractions are so strong we insist on exercising them despite discrimination and rebuke? I can’t construct a political affinity, or a social one.

At the risk of political incorrectness, I cannot even comprehend the point of organizing people whose commonality is what they don’t like to do? How is asexual.org different from CoffeeDecliners.org? ModelTrainsNotForMe.com? IHateHats.biz?

Actually, I can see how asexual people might harbor legitimate complaint, condemned to navigate our hyper-sexualized world. Yet the essay makes no mention of that. Perhaps asexual people want to meet one another away from the Tindr prowl. The article doesn’t suggest that either. Instead, Ms. Kirichanskaya posits that being asexual is a sexual orientation. In fact, it is precisely the opposite: a lack of orientation.

Aha! No orientation? Unacceptable. In this era of identity is everything, robbing someone of a full identity-complement to spill after their name is true harm.

Paul E Fallon: cisgender gay white male. Irish-American. Retired architect. Father. Non-smoker. Pathetic drinker. Writer. Cyclist. Intermittent depressive. I could go on, but no matter how long the list, it will never fully describe. Because, regardless how many adjectives I string, I am human. Sometimes irrational. Often unpredictable. Still appreciative of a shapely woman, identity be damned. Pretty much like seven billion others. Unique in all the world.

Really? What does this slogan mean?

Really? What does this slogan mean?I don’t know what asexuals do when they get organized. (Although I do know what they don’t do.) If someone feels the need to adopt an identity whose chief characteristic is a disinterest, and get together with others similarly disinclined, go for it. But I still find it funny.

July 21, 2021

Massachusetts’ Bold Opportunity: Abolish Women’s Prison

Massachusetts S. 2030, a bill to place a moratorium on all prison construction for five years while we evaluate alternatives to our carceral system, is accepting written testimony through August 4. Please consider offering your testimony (link). This post is an essay published in the Cambridge Chronicle that advocates for even more.

The moment I learned that the international architecture firm HDR was selected to create the preliminary plan for a new women’s prison to replace MCI-Framingham, my mind reeled back forty years. 1981. One month out of Architecture School. My first professional assignment: a new hangar for the U.S Navy. I was dumbfounded. School projects had included clinics, housing, arts centers; nothing that challenged the ethics of a bloke who’d chosen to be a VISTA Volunteer rather than a veteran. Next day I explained to my boss why I could not, in conscience, work on a military facility. Today, I wonder how many HDR staff feel compelled to decline working on the new prison.

MCI-Framingham, built in 1877, is the oldest operating women’s prison in the United States. Department of Correction’s (DOC) has determined that the antiquated facility needs to be replaced. To the tune of $50 million.

I suggest we consider a bolder, more cost-effective, more humane option. Instead of replacing the building, let’s replace the system. Let’s change our operating assumption and decide that no woman in Massachusetts will be sent to prison. Period. Let’s create alternative, decentralized methods to deal with criminally accused and convicted women. (Note: the term ‘women’ reflects DOC terminology regarding inmates’ gender identity.)

Massachusetts is at a propitious inflection point that makes abolishing incarceration of women both practical and feasible. In April 2021, there were 162 inmates at MCI-Framingham; across the state 480 women total were held for bail, in jail, accused or convicted. The lowest female incarceration rate of any state.

This is something worth celebrating; unless you’re one of those 480 women, or a member of her family. How much do we spend keeping these women behind bars? Over $117,000 per inmate per year in direct costs; thousands more in collateral human services (over 60% of female inmates leave children under age eighteen behind). Now, we’re proposing to spend over $300,000 per inmate in additional capital expenditure.

The combination of (relatively) small prison population and abundant resources is a perfect opportunity for a pilot program that acknowledges the prison system, as we know it and grow it, is successful in keeping folks we don’t like out of sight, but it’s a failure in enabling them to rejoin and participate in society. It’s time to rise above the illusion of prison ‘reform’ and commit to developing accountability, reconciliation, and restitution within our community. This will be more difficult than putting women behind bars, but it offers transformational possibilities.

If we resolve to have ‘no women’s prison,’ we are free to reallocate resources to address underlying criminal causes: violence, poverty, racism, mental illness. We can replace incarceration with community-based residential support facilities that enable families to remain intact. We can use technology to monitor women during periods of restitution. We can actually create the rehabilitation that prison fails to produce by embedding women in their communities, responsible to their communities, accountable to their communities.

I don’t pretend to know how to create community-based alternatives to incarceration. My expertise lies in quite different arenas. After declining to work on military facilities, I focused on healthcare design, and became a savvy at synthesizing and articulating clinical, patient, and financial demands with soothing polish. So when I hear HDR intone the phrase ‘trauma-informed prison design,’ I’m keen to the phony buzz. There is no such thing as trauma-informed prison design. Prison is, by definition and design, a trauma that we inflict on already traumatized people. Sometimes the convicted have traumatized others. Almost always, the convicted traumatize us: by acting outside norms; by exposing the hypocrisy of societal benevolence.

The economic case against building a new women’s prison is strong. The humane case is irrefutable. Will we take this opportunity to do the truly right thing and commit ourselves to no women in Massachusetts’ prisons? We can replace the oldest women’s prison in the nation with a new paradigm of criminal justice; a model that demonstrates it’s unnecessary to imprison women. Once we develop that, we can adapt the approach to unprison adolescents, geriatrics, and eventually: everyone.

July 14, 2021

The High Price of Elite Housing

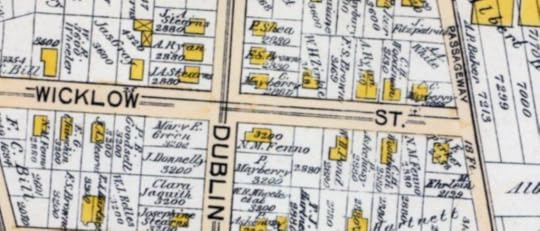

One hundred thirty years ago, in 1891, Mr. A.E. Parker built a house at 60 Wicklow Street in Cambridge. A 2-1/2 story wood frame building that he shared with his wife. The building first appears in the 1894 Bromley Atlas, another yellow outline in the growing city of Cambridge.

By the time the next Bromley Atlas was published, in 1903, Wicklow Street had become Stearns Street. Eventually, it was designated part of Neighborhood Nine, a sort of shorthand for saying, neither here nor there. Stearns Street’s an equidistant walk from Cambridge’s long-time tony, Tory, Brattle Street; Victorian-fashionable Avon Hill; and the rough-and-tumble worker housing near Alewife’s clay pits.

The Harvard/Radcliffe Archive of Cambridge Buildings and Architects includes no other references to 60 Stearns Street. Little wonder, since the ordinary building on its meager lot hardly warranted special attention. At some point it was chopped into a two-family residence. It got wrapped in aluminum siding.

In the early 1990’s, before my family moved to the hinterlands of Cambridge—Strawberry Hill—I looked at a couple of houses on Stearns Street. Not this particular address, but buildings like it. Priced in the $200-$300 thousand range. An astronomical price for century-old workingman’s digs, chopped into mazes, cracked plaster covered with thin wood paneling, creaky floors slathered with shag carpet.

The long-standing family that owned 60 Stearns Street finally sold it in 2018. By then, the city assessed the 4,457 square foot piece of land at $791,300 and the structure at $446,200. Though the city fell far short of the market. A developer bought the property for $1,648,000 and promptly tore the building down. That’s $370 per square foot for land alone.

As the pandemic waned, and I returned to the gym, I noticed a new house on the site in final throes of construction. I traded jokes with the Portuguese guys laying pavers; Hispanics installing the landscaping. We laughed that none of us could ever live there, and wondered what kind of people would.

In June 2021, the new 60 Stearns Street came on the market. The 4,200 square foot, single family, five-bedroom, 5.5 bath house is marketed as “the world’s first Victorian passive house.” I guess, when you’re trying to sell a big house on a small plot with no appreciable view for $4.5 million, you’ve got to work the lingo.

Apparently, the lingo works, as the house was featured on Boston.com, June 15, 2021 as ‘Luxury House of the Week,” and merited an article in Harvard Magazine.

As I walked by one recent sunny morning, a father walked onto the second-floor deck with his young daughter, prospective buyers, obviously touring. “Do you think you could be a princess here?” I heard the man say. (Really. I couldn’t make up that line if I tried.) Thereafter, an older gent, the grandfather, stepped onto the deck. And I beheld a vision of generational wealth.

I don’t know whether that family purchased the house. If not someone like them did: 60 Stearns Street went under contract within thirty days. The City of Cambridge will make out well financially: the new property taxes are estimated at $7,439 per year, are almost twice what they were. But socially, culturally, I fear our city will be further diminished, as it becomes more impossible, one property at time, for people of average means—actual workers—to afford to live here.

July 7, 2021

Clothesline Romanticism

What comes to mind when you see this photo? Crisp air, fresh scent, a stiff sleeve that lovingly conforms to your arm as if softens to your unique form.

I cribbed the image from Heather Cox Richardson’s newsletter. Ms. Richardson, a professor of American History at Boston College, writes the brilliant daily “Letters from an American,” an intelligent blend of current events and historical perspective. Five nights a week she publishes polished essays that put the events of our day in context. On weekends, she frequently posts an evocative image, often from her family camp in Maine. A few weeks ago, she offered this yesteryear photo of laundry on the line.

The photo caught my eye because, not long ago, I created my own, urban, telescoping clothesline. When I posted pics on Facebook, I received glowing comments, like, “there’s nothing better than air-dried clothes,” “heavenly,” and, “reminiscent of grandmother.”

Clotheslines were part of my youth. Behind every house on our street was a slab of concrete in which a vertical pole supported an awkward square of galvanized metal and cotton ropes. I wonder how many, if any, still remain.

It’s been decades since I’ve seen an active clothesline. If you live in a covenant development or gated community, clotheslines are likely prohibited. Even along traditional streets, they’re rare as hitching posts.

If air-dried clothes are so wonderful and evocative, why don’t we see more clotheslines? The answer is easy. American life is the steady march of time-saving convenience over sensory experience. Mechanical dryers are simple and quick. They free us from the uncertainties of weather. So what if they use energy already swirling free in the wind. So what if our clothes smell a bit musty. We add Snuggle or Downy or Bounce to our load; something else to purchase that simulates what we’re too busy to get for free.

I love the image of the clothes drying near the sea. Ms. Richardson apparently does as well. Never mind that there are more grey, drizzly days on the Maine coast than sunny ones; that hanging laundry is an arduous task; collecting it later as well. That air-dried laundry is time consuming work, almost always relegated to women, binding them to the home.

Most anyone would give up their clothesline for a gas dryer. And yet we romanticize laundry on the line. Another picturesque of a bygone, simpler time in when our existence was rooted in rudimentary tasks that, incidentally, bound us to nature.

July 1, 2021

Cliff Notes: Free, Smart, Real, Just America

If you have 45 minutes to ponder the state of this great nation over the upcoming Independence Day weekend, I recommend “How America Fractured into 4 Parts,” by George Packer, published by The Atlantic in Medium. If you don’t have kind of time, I offer these Cliff Notes to a useful perspective on our country’s status.

The melting pot that is the United States of America has devolved into that picky eater who separates his food into discrete piles, and freaks out when runny egg seeps under his bacon or a single grain of rice infiltrates his beans. Each of us falls, with scary precision, into one of four camps. Each camp crafts a narrative that stakes legitimate claim as rightful owner of the 21st century American dream. Yet each dismisses all others as immoral or unpatriotic, ignorant or communist. In truth, each faction is a little bit right, a little bit wrong, and all whole lot obstructive.

Free Americans are the ideological descendants of libertarian backlash to the New Deal that gathered steam under Barry Goldwater, came to full flower under Ronald Reagan, and flourishes as today’s dominant politics insomuch as every policy discussion gets couched in terms set by Free Americans. The individual is supreme. His rights are paramount. The only good government is less government. And that extends to corporations, who fill campaign coffers in exchange for unfettered freedom.

Smart Americans are highly educated citizens who feast upon the bounty of a knowledge/technology-based economy. We are the coastal elites (plus university-town pimples on the landscape like Austin, Texas; Lawrence, Kansas; and Madison Wisconsin). Smart Americans are affluent and motivated, albeit removed from fundamental economic tasks like growing food or manufacturing objects. Globalists rather than nationalists for the simple reason that globalism serves us well. We consult and program and hedge-fund under the delusion of meritocracy’s inherent equity, without admitting that the operating systems are stacked in our favor. We have the answers—and the economic success—that proves we’re right; we can’t fathom why others don’t climb aboard. (I use the pronoun ‘we’ for this faction, since both George Packer and I are, for better or worse, Smart Americans.)

Real Americans consider themselves the backbone of our nation. Rural, in spirit if not in fact. Religious, of an evangelical slant. Traditional in their values, especially those that evoke a white, agrarian past. Hostile to modernity. Allergic to intellectual authority. These are the Americans who catapulted Donald Trump to the Presidency. But Trump didn’t invent this faction; he’s simply a master of tapping into their long-standing suspicions. More than a century ago, populist William Jennings Bryan said, “If we have to give up either religion or education, we should give up education.” Sentiment that echoes the priorities of Real Americans today.

Just Americans—or perhaps they should be labelled Unjust Americans—are typically younger, disenfranchised citizens weaned on critical race theory and identity politics. Mr. Packer dates their emergence to 2014, when Michael Brown’s death became an indictment of our system rather than of bad apples. Just Americans reframe our entire history through the lens of racism. And though that perspective has been long discounted, it alone offers a monocular vision of a complex nation. When society is conceived as a collection of conflicting group identities, there’s no accounting for an individual’s responsibility and motivation. Thus, in direct contrast to Free Americans, Just Americans repudiate our central myth of rugged individualism. The circle of ideological conflict is complete.

Today, Free Americans and Real Americans have an uneasy political alignment, as do Smart Americans and Just Americans. Mr. Packer does not see those affiliations as fixed. However, as his article is centered on describing the state of ourselves—now—rather than speculating how we will evolve, he does not suggest how affiliations might morph and change. His concluding tone remains optimistic, perhaps even Pollyannaish: we’re all in this together and will eventually figure out how to move in sync.

I’m unconvinced of Mr. Packer’s optimism. But it’s summertime, and the living is easy, and our flags are flying high. So enjoy! Own whatever faction of American politic suits you best, but please acknowledge our fellow citizen’s claims. And strive to get along. Whether Free or Smart or Real or Just, we need each other so much more than we’re willing to admit.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Note: All images courtesy of Lucy Jones and Atlantic Magazine.

June 23, 2021

: (

In honor of summertime and all things light, I share with you a piece by humorist Simon Rich, which cracked me up.

I used 2 B a typical teenage girl, gossiping with my gal friends on the weekends (I luv U guys!) throwing slumber partis (zzzzzzz!) That was B4 I contracted hepatitis C.

Sometimes I ask myself, “Y? Y has the lord 4saken me? R U there God? Have U 4gotten me?” I’m trying 2 B positive, but it’s hard when U know that your death is a 4gone conclusion. It’s only a matter of time B4 my D4med liver ceases 2 function 4ever.

My innards R swarming w/2morous growths & the pain is excruci8ing. I no longer have any will 2 live. 2morrow I’ll be sed8ed 4 the oper8tion. Secretly, I hope I don’t come 2.

I’ve decided 2 stop praying. Y should I? I h8 god. He sh@ on me & I h8 him,

All I can do now is w8 4 death.