Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 69

May 21, 2018

Antarctic quest seeks to predict the fate of a linchpin glacier

(AP Photo/NASA)

This article was originally published by Scientific American.

If Thwaites Glacier goes, so might the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Thwaites has long been recognized as a linchpin for the massive expanse, which covers an area the size of Mexico and could unleash more than three meters of sea level rise were it all to melt. Thwaites alone is losing 50 billion tons of ice a year, and recent research suggests the glacier has already entered an unstoppable cycle of melt and retreat that has scientists seriously worried.

If Thwaites Glacier goes, so might the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Thwaites has long been recognized as a linchpin for the massive expanse, which covers an area the size of Mexico and could unleash more than three meters of sea level rise were it all to melt. Thwaites alone is losing 50 billion tons of ice a year, and recent research suggests the glacier has already entered an unstoppable cycle of melt and retreat that has scientists seriously worried.

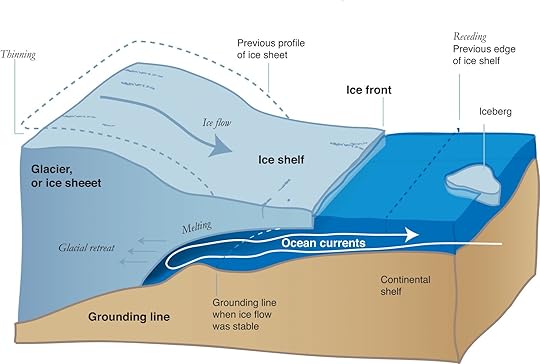

Glaciers are essentially rivers of ice. Like other Antarctic glaciers Thwaites flows toward the sea — and once there its ice begins to float, forming what is called an ice shelf. This shelf then acts as a doorstop that pushes back against the glacier’s flow. But warm ocean water has been nibbling at Thwaites’s ice shelf; as it thins, the ice behind it flows faster. That same water can chip away at the glacier’s “grounding line,” the place where the glacial ice meets the sea and where rock ridges currently help anchor it. If the ice thins enough, it could separate from those ridges, causing the grounding line to recede. And because Thwaites and much of the rest of the ice sheet rest on bedrock that sits below sea level, any retreat of the grounding line lets water penetrate farther inland, melting more ice and further speeding glacier’s flow. Because Thwaites drains the very center of the larger ice sheet system, if it loses enough volume, it could destabilize the rest of the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Scientists have been trying for years to conduct a major study of the remote glacier, in order to get an up-close look at these processes driving its retreat and to search for clues as to how quickly it could disappear. Now they are finally getting the opportunity with a $25-million joint U.S. and U.K. expedition involving eight projects that will poke and prod every aspect of the glacier and its environment — the climate science equivalent of a new Mars rover mission. The five-year effort will use tools ranging from radar devices dragged across the ice to image the glacier’s interior to autonomous underwater vehicles to sensors attached to elephant seals.

The bedrock below Thwaites Glacier slopes inward toward the continent, which allows warm, deep ocean water to flow downward under the ice shelf, chewing away at the grounding line. Credit: NSIDC, NASA

The data gathered will be plugged into climate models that will hopefully generate a clearer picture of what the future holds for Thwaites and West Antarctica, says project co-leader Ted Scambos of the National Snow and Ice Data Center. Scientific American spoke with Scambos about the scientific importance of the mission—called the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration — and about exactly what researchers will be looking for when they set out in October 2018.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows]

Why is the melting of Thwaites a concern for the U.S. and other distant areas?

What we’ve learned, actually, is that when you move this amount of mass—trillions of tons of ice—around, you actually change, just a little bit, the gravitational pull that the continent has on the ocean around it. So not only does sea level on average go up but—ironically, I guess—in the vicinity of the ice sheet that’s losing ice, sea level actually drops because the continent doesn’t pull the ocean against it quite as much as it used to. What that means is that if, on average, you get one meter of sea level rise by the year 2100, most of the tropical areas of Earth will see 1.2, 1.3 meters of sea level rise. And so it actually means bigger problems for Florida and Texas and Bangladesh and Shanghai — low-latitude coastal cities and low-lying areas.

What makes the evolution of Thwaites so hard to predict?

It’s hard to know exactly when the glacier is going to thin enough to release from these areas of the grounding line that are currently holding it back, and also hard to predict how that acceleration — the speedup of the glacier — is going to unfold as the ice continues to thin.

The issue that’s come up more recently, and the one that actually has people worried about changing the timescale [of retreat] from a few centuries to several decades, is what’s called “marine-ice cliff instability.” And what that means is that if, by some process — probably having to do with surface melting — you suddenly remove the front of the glacier and have it calve back to where all of the floating part is gone and there’s just a tall cliff over a hundred meters tall at the waterfront, that cliff is inherently unstable. The stresses at the top of that cliff are enough to fracture ice immediately, and so you get into a situation where the cliff, as soon as it’s formed, begins to collapse. But the ice behind it is thicker, and so that cliff is even less stable.

What we’ve seen in Greenland is that these processes are underway for a short while, and the ice sheet certainly thins and flows much faster than it did before the beginning of the retreat. But it seems as though the marine-ice cliff instability is temporary, because the ice is deforming so fast anyway. So the question is: Just how is this all going to unfold?

Can you talk about what some of the projects will explore?

The core of it is really these studies that focus on the ocean and the ice interaction at the front, because that’s where we think things are going to be triggered. So there [are] two studies that are aimed at looking at how the ocean that’s right up against the front of the glacier interacts with the glacier ice — how it melts it out, how fast it melts out.

The other aspects of these studies in front are to really map out the ocean currents and temperature profile in detail. One of the assistants, or collaborators, that we’re going to have are seals that will have a little instrument pack strapped to them that will measure the profile of ocean temperature and salinity every time they dive down to get food. We’re planning to use elephant seals. They’re incredible divers; they’ll go as much as a kilometer below the surface of the water. And they dive 15, 20 times a day, so we get a tremendous amount of information.

And then the really tough place to make measurements is underneath the floating ice shelf, underneath this thick plate of ice. You have to have a submersible that will go fairly deep — hundreds of meters down below the surface — and then really navigate by itself and make decisions on its own, about whether or not it needs to go up or down or around any kind of obstacle that it encounters…right to the point where the glacier first goes afloat.

There’s also some new instrumentation that we’ll install from the surface of the ice, where we use a hot-water drill. We’ll go maybe a thousand feet through the ice and then lower a string of instruments into the ocean. We’ll do that at three or four places and get year-round measurements of what’s going on underneath. So, if that ain’t a science adventure, I don’t know what is.

What are some of the features you’ll be looking for in the data—for example, from the underwater autonomous vehicles and the radar traverses of the glacial surface?

In the traverses that are driving over the glacier to get a profile of what the glacier ice is like and what the bedrock is like below it, we’re going to be looking for where the glacier is frozen to the rock below and where it’s thawed. (It’s going to be thawed in most places.) And then also where there are patches of soft sediment. This stuff is like toothpaste, basically; it’s completely pulverized rock, and smeary and sticky and slippery. And that’s a big reason why glaciers in West Antarctica can flow very quickly. The other thing that they’ll be looking for on those traverses is how the ice is deforming, and we can actually measure that by how sounds waves pass through the ice.

In general [the autonomous vehicles are] going to be [measuring] temperature and salinity. And then the more sophisticated one…will use sonar to map in detail [as] it’s flying over the seabed — and then also what the underside of the ice looks like in detail. Those structures tell you things about what’s going on at the grounding line, because the ice at the grounding line is flowing away and out to the ocean at several kilometers per year. At 10 kilometers [out], what you’re looking at used to be grounded on bedrock at the edge of Antarctica just two or three years earlier.

How do you do such intricate studies in such a remote area, and how excited is the team?

Planning, planning, planning — and a lot of spares for the critical components. We’re just going to have to hope for enough luck and enough skill to get through the first few seasons, and get the real data that we’re after out of all of this.

It’s going to be a heck of a lot of work. The e-mail traffic alone is already just enormous. But we’re excited to be able to get out there. It’s going to be remote. There’s going to be days when we hate ourselves for having signed up for this. But in the end it’s going to be a great story, both for science and — I’m going to be frank with you — for adventure as well.

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

May 20, 2018

Bangladeshi rappers wield rhymes as a weapon, with Tupac as their guide

AP/Bebeto Matthews

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Bangladesh, which became independent from Pakistan in 1971, is a young country. Only 7 percent of the 160 million people in this South Asian country — which is home to more Muslims than Iran, Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia combined – are over the age of 60, according to a 2016 United Nations Development Program report.

It is young, but not hopeful. Youth unemployment is high in Bangladesh, especially among those with only a primary school education. According to a recent survey, 82 percent of young people are not optimistic about getting a job.

One consequence of this youthful unrest is religious radicalization. Once lauded for its secularism, Bangladesh is now seeing young people increasingly adopt more conservative Islamic values. Though many conservative Muslims denounce violence in the name of Islam, religiously motivated crimes are on the rise. Since 2013, at least 30 secular bloggers, authors, intellectuals and publishers have been murdered.

But there is another story about youthful anger in this Muslim nation, too. And it contradicts that all-too-familiar narrative about radicalization. It’s the story of hip-hop.

Tupac, Eminem and young rage

Over the past 15 years or so, a new kind of musical activism has emerged in Bangladesh, one inspired by American rappers like Tupac Shakur, Eminem, NWA and Public Enemy.

The old school hip-hop icon Tupac Shakur — who was murdered in Las Vegas in 1996 — holds particular significance for Bangladeshi MCs. Like Shakur, who spoke of police brutality and racism in the U.S., Bangladesh’s young rappers want to use their music to criticize their country’s political dysfunction, democratic erosion and gaping inequality.

Hip-hop was born as protest music in the United States. The genre emerged in the late 1970s, as black Americans raised their voices against the poverty, police brutality and violence taking place in black communities.

"Fight the Power," an early hip-hop anthem by rap pioneers Public Enemy.

Songs like “Fight the Power” by Public Enemy and NWA’s “F*!k tha Police” underpinned the black struggle for black freedom and freedom of speech in America. This trend continues today, with hip-hop fueling the social movement Black Lives Matter.

Breaking the culture of silence

Over the past 12 months, I have listened to about 50 tracks by some two dozen Bangladeshi hip-hop artists. With this project, which grew out of my research on political Islam in Bangladesh, I hope to understand how this emerging underground genre reflects the youthful unrest that drives violence and radicalization in the country.

Though many Bangladeshi rappers rhyme about love, money and romance, there are several recurring political themes. One is the culture of silence around inequality.

“Everyone is silent … nobody is talking,” observes rapper Skib Khan in “Shob Chup.” The elite need inequality, he says, because “otherwise how will the rich get servants to serve their families?”

In Bangladesh, more than 60 million people – nearly a third of the population – live below the poverty line of US$1.90 per day. Twenty percent of Bangladeshis hold 41 percent of all wealth in the country.

Inequality is visible everyday in the slums of the capital Dhaka, arguably the world’s most crowded city. But it is ignored in the nation’s political debate.

“Shob Chup,” which translates to “everyone is silent,” frames the country’s inequality and disenfranchisement as a betrayal of the inclusive, secular and democratic ideals behind Bangladesh’s 1971 revolution.

Rapping for freedom of speech

Bangladeshi hip-hop, which is celebrated with an annual festival in Dhaka, is also a defense of free speech in a country where that right is rapidly eroding.

In 2013, the government amended the Information and Communication Technology Act to mandate a jail sentence of seven up to 14 years for online speech deemed “offensive” by the courts. Since then, 1,271 Bangladeshi journalists and activists have been charged with cyber defamation, according to the international nongovernmental organization Human Rights Watch.

A proposed new digital security law would impose even stricter regulation of speech.

In his track “Bidrohi,” or “rebel,” rapper Towfique Ahmed sees these crackdowns as a violation of Bangladesh’s founding ideals.

“I haven’t seen the war but I heard of it. I don’t know how to do revolution but my blood is on fire,” he raps. “Don’t take me as someone who is stupid because of my silence.”

Another group Cypher Project raps about the high-profile 2014 murder case in which security forces abducted and killed seven people in the Bangladeshi city of Narayanganj.

Dysfunctional politics

Bangladesh’s politics is bloody. By virtually any measure — political equality, freedom of speech, human rights, religious tolerance, press freedom — this is a country struggling with the most basic tenets of democracy.

Rappers’ criticism of Bangladeshi politics can be fierce.

One group, Uptown Lokolz has declared elections, which are held every five years, pointless. The “country’s situation changes in every five years,” they rap. Yet “whoever comes in the power . . . everything is lost under the curtains of self-interest.”

Rappers also indict self-serving politicians for the rise in religious violence in Bangladesh. In “White Democracy,” the rapper Matheon wonders “for how long religion would be subject of big politics . . . maybe I am a Christian but I understand your corruption.”

"White Democracy" indicts the corrupt politicians who manipulate religiosity to amass power.

Research confirms that mainstream parties in Bangladesh have embraced religious zealotry for political gain, giving Islamic extremists more power. Religious radicalization is not a marginal phenomenon in Bangladesh: Studies have found that many who support terrorism in the name of religion come from a middle-class background.

The U.S.-based Bangladeshi rapper Lal Miah condemns politicians who foment religious zealotry as “frauds who are betraying the secular spirit of 1971.”

Towfique Ahmed has perhaps the most pointed critique. Bangladeshi politicians corrupting society for their own benefit, he says, are waging “false Jihad.”

Speaking truth to power in a time and place where that habit is strongly discouraged sends a powerful political message. Hip-hop in Bangladesh, as in the U.S., becomes protest music simply by unflinchingly portraying the harsh reality that too many young people live everyday.

This article has been updated to correct the date and location of Tupac Shakur’s death.

Mubashar Hasan, Postdoctoral fellow, Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University of Oslo

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

Meet Barbara McClintock, who used corn to decipher “jumping genes”

Christy Thompson via Shutterstock

This article originally appeared on Massive.

I love corn. My favorite way to have it is cooked over a grill until charred, and then lathered with cilantro mashed up in Mexican sour cream, feta cheese, chilli, lime, and lots of garlic. Yummy.

I love corn. My favorite way to have it is cooked over a grill until charred, and then lathered with cilantro mashed up in Mexican sour cream, feta cheese, chilli, lime, and lots of garlic. Yummy.

I really do love corn, but not as much as one woman: Barbara McClintock. For nearly 70 years, she could not get enough of the stuff and, in 1983, her fixation won her a Nobel Prize.

By meticulously crossbreeding corn, McClintock showed that DNA is far more complicated than scientists originally thought. DNA, the blueprint of life, is about two meters long when unfurled and packaged into tightly coiled, thread-like structures called chromosomes, of which we have 23 pairs. You may have been told that our genes are instructions stored on DNA in our chromosomes like information stored on magnetic tape in the 1980s. Read out those instructions and voilà! You can build an organism.

However, in the 1930s and 40s, McClintock’s work showed that some genes did not exist in fixed position on chromosomes, but could actually jump around from one part of the chromosome to another. These “jumping genes” are now called transposable elements. She also found that the genome is not just a passive database of information but a sensitive and dynamic system, containing a whole host of elements that interact with their environment and each other. Her ideas were completely radical at the time and met with “puzzlement, and even hostility” as she described it. It took everyone else over 20 years to catch up.

Early education and research

McClintock was born in 1902 in Hartford, CT. Her father was a homeopathic doctor whose parents emigrated to America from Britain, and her mother was a housewife, poet, and artist from an upper-middle-class Bostonian family. Growing up, McClintock, one of four children, liked being alone, often reading by herself in an empty room for hours. Her comfort with solitude was also true in adulthood, where she became a pioneer in corn cytogenetics, the combination of classic genetic techniques and microscopic examination of corn chromosomes.

Her love affair with genetics started in 1921, when she took a genetics course as an undergraduate at Cornell’s University of Agriculture led by plant breeder and geneticist C.B. Hutchison. Hutchison was impressed by McClintock and invited her to participate in the graduate genetics program. That was it. In 1923 she received her bachelors, in 1925 her masters, and in 1927 a PhD - a feat quite commendable for a 24-year-old woman at the time.

After earning her PhD at Cornell, McClintock stayed on as an instructor and assembled a close-knit group of plant breeders and cytologists in the Department of Plant Breeding there, including two fellow graduate students, Marcus Rhoades and George W. Beadle (who went on to also win a Nobel Prize) and the department head Rollins A. Emerson.

“We were considered very arrogant,” she said. “We were ahead of all these other people, and they couldn’t understand what we were doing. But we knew, and we were really a very united, integrated group.”

Back in the 1930s, the tools that we now have available to simply read a genetic code and link it to a particular trait did not exist; the fact that genes were encoded in DNA had not even been discovered yet. To understand the mechanisms of inheritance in plants, Barbara McClintock had to rely on cross-breeding corn and developing hybrids. Her research focused on finding a way to visualize corn chromosomes and characterize their shape in the resulting hybrids, igniting the field of corn cytogenetics at Cornell. In 1932, McClintock moved to the University of Missouri to work with geneticist Lewis Stadler, who taught her how to use X-rays to introduce mutations into chromosomes. She turned out to be very gifted at doing so.

Nobel-caliber research

In 1941, McClintock took up a research position at Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island and later became a permanent faculty member there, becoming known for her tenacity. My favorite story about McClintock is the one about her telling off a group of students — including a young James Watson, one of the scientists who would go on to discover the double helix structure of DNA — for wayward balls landing in her crop during their baseball games. Watson described McClintock as “like your mother” - and not in the good way. Little did he know that her research on corn genetics would go on to challenge the simplified version of DNA his work would later support.

McClintock remained at Cold Spring Harbor for the rest of her career. She spent much of her time there studying the relationship between color patterns on corn plants and the look of their chromosomes under a microscope. Drawing upon what she had learnt in Missouri, she used X-rays to destroy sections of chromosomes in order to work out where genes were, what they did and how they mutated, linking changes in genes on the chromosomes to changes in traits on the plant.

However, there were two genetic elements that McClintock could not locate on the chromosome and concluded that this was because they were not fixed to one particular position — they appeared to be jumping around the chromosomes and explained why some corn had a mosaic pigmentation pattern rather than being one solid color. This phenomenon had been described before – they were called ‘transposable elements’ — but McClintock had a new theory about them: she thought that they were responsible for controlling and regulating how the genes that they found themselves next to were expressed, and that this was a deliberate feature of how the genome worked not just in corn but in other organisms like humans.

McClintock was not completely right. Firstly, jumping genes — transposons — do exist in abundance; today we know that they make up 50 percent of the human genome. Secondly, though there are controlling elements in the genome that are responsible for switching genes ‘on’ and ‘off’ like molecular switches, they’re not transposons. These elements, which regulate the expression of different genes and traits at different stages of development and allow different cell types with the same genome to have different patterns of gene expression, actually sit next to the genes they control and stay put. Still, she had stumbled upon an important fundamental idea about genetics. But when she presented what she believed to be the most important findings of her career at Cold Springs Harbor annual symposium in 1951, her work was not well received; her peers could not follow her theories, which they considered to be preposterous.

Disheartened, she decided not to bother publishing her work again after that. But she did not stop working on corn genetics — “When you know that you are right, you know that sooner or later it will come out in the wash,” she said.

In the 1960s and 70s, independent groups of scientists began to describe genetic regulation and the phenomenon of transposition in bacteria. In 1960, Francois Jacob and Jacques Monod described genetic regulation in bacteria. (Not missing a beat, McClintock responded in 1961 with a paper: “Some Parallels Between Gene Control Systems in Maize and in Bacteria”.) McClintock’s earlier work started to gain credibility and finally, in 1984, at the age of 82, she got the recognition she deserved and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “The discovery of mobile genetic elements.” Apparently, McClintock had no telephone at the time and happened to hear the news on the radio.

Gender discrimination?

McClintock’s profound discovery was dismissed by her male colleagues for years. In the book "A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock," Evelyn Fox Keller paints this as gender discrimination, putting her late recognition down to the fact that she was a woman. This a story we hear a lot. Watson and Crick vs Rosalind Franklin and the Nobel Prize in Physiology in Medicine, Hewish and Ryle vs Jocelyn Bell Burnell and the Nobel Prize in Physics.

However, this may not have been the case for McClintock. As research for his book "The Tangled Field: Barbara McClintock’s Search for the Patterns of Genetic Control," historian of biology Nathanial Comfort spent many hours looking through McClintock’s correspondences, research notes, and interviews and argues that this notion of gender discrimination is not consistent with the facts. She was enormously well respected in her time by both her male and female colleagues.

Describing this story of gender discrimination as mythology, arising only when she gained popularity in the run up to her Nobel Prize in the 70s and 80s and began to give more interviews, he explained in an interview on the BBC in April 2018 that her late recognition really was down to the fact that movable elements were reinvented in the 1960s when they were discovered in bacteria and given a different context.

Barbara McClintock died in 1992, eight years after her Nobel Prize. Whatever the reason for her late recognition, she didn’t seem to mind — saying to People magazine 1983, “It might seem unfair to reward a person for having so much pleasure over the years.”

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

It took food poisoning, $7500, and an intervention to make me realize I had a kombucha problem

On the day of our OKCupid date, I woke up thinking not about my suitor, but about his fungus. How big would it be? What would it smell like? I waited on a bench at the park. He arrived holding a mason jar covered in saran wrap. I made my best small talk, occasionally grazing his arm and offering a compliment, so he wouldn’t change his mind about the SCOBY. As soon as I could get away, I raced home to examine my prize. It reminded me of a placenta, slippery and grotesque and beautiful.

I never saw the guy again.

Let me explain: a SCOBY (“symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast”) is the fermentation engine of kombucha, a probiotic tea drink made from tea and sugar. Kombucha purportedly aids digestion, boosts immunity, reduces inflammation, increases energy, alleviates anxiety and depression, and—according to the most ardent believers—cures cancer. As a daily kombucha drinker, I’d decided to save money (and admittedly develop a deeper relationship with my favorite beverage) by brewing it myself.

New to San Francisco, I was already using OKCupid to date and expand my social circle, so I decided to use it to procure a SCOBY. Using a keyword search I found a blond grad student who listed kombucha brewing as one of the “six things he couldn’t live without.” He wasn’t my type, but that was of little concern. When I mentioned my interest in brewing, he offered to bring a SCOBY to our first date.

To start the brewing process I sterilized a large glass jar, brewed black tea with sugar, and fed it to my newly christened treasure: Toby the SCOBY. Each week I moved the prior week’s batch into an airtight jar in the fridge to further ferment. I showed off Toby to anyone who visited my apartment, as slap-happy as a kid at a science fair.

I first tasted kombucha at the health food store where I worked during college. It was effervescent and tangy, reminiscent of champagne; life-affirming. The store stocked just one brand and flavor, GT’s Original. At 60 calories, 4 grams of sugar, and one billion probiotic organisms per bottle, I marveled at how something so delicious could actually be good for me.

Growing up in LA, the only way to have your cake and eat it too was to make the cake gluten-free and vegan and not eat anything else that day. With kombucha, I was changing the part of myself that thought I’d always feel bad for tasting something good.

Each week I started trading in some of my paycheck for kombucha. I drank it when my stomach hurt, or when I needed to de-stress before a test, or when I had a reason to celebrate. It soothed me, similar to how I imagine the effects of Xanax, or catnip, might feel.

Over the years, what began as an occasional treat evolved into a daily need. I started bringing my own to dinner parties. When it was on sale I bought triple. Wherever I was, I had a mental map of where to purchase a bottle and the price difference at each location. If it was a particularly good day—or a particularly bad day—I might let myself have two. I had favorite flavors for different moments: ginger for stomach malaise, lemon for a hot day, cranberry for a cocktail mixer.

And now that I was brewing Kombucha myself, I could enjoy it on a daily basis without forking over $4 a bottle. A few months into my brewing experiment, however, I was at the office mid-PowerPoint presentation when I started feeling queasy (more than the normal nausea induced by PowerPoint). I took an urgent Lyft ride home and spent the rest of the day running between the bed and the bathroom, clutching my stomach and praying to the gods of food poisoning relief.

That night, I texted my mom to tell her I thought my kombucha had made me sick, as I hadn’t consumed anything else questionable in the last 24 hours. The next day she sent me an email with the subject line “kombucha and your health.” According to the FDA and the CDC, home-brewed kombucha can cause lead poisoning, fungal infections, and (in one reported case) even death. My med school brother also texted me.

“When brewing kombucha, it’s easy to not only grow good bacteria, but bad bacteria too.”

“We think you should stop,” he added.

Was this my family’s version of an intervention?

A few days later, after I had recovered, I decided to do my own research into the risks of home-brewing. Apparently, contamination of homebrewed kombucha is more likely because the SCOBY and the resulting liquid aren’t tested for quality; plus, temperature controls and sterilization aren’t managed as closely. As a result, the SCOBY can produce harmful bacteria and aspergillus (a toxin-producing fungus), which can cause illness.

I loved brewing kombucha, but I didn’t want to make myself ill from it. I decided to stop brewing. Then came a truly San Francisco problem: Should I put Toby the SCOBY in the compost bin or the trash? With a sigh I placed Toby in the compost bin, feeling as if I was saying goodbye to someone I liked but had only just met. To comfort myself I went to the corner store and spent $3.99 on kombucha made by professionals.

That was five years ago. Since then, I’ve continued to drink professionally brewed kombucha every day. By my accounting, I have spent $7,580.04 on kombucha in my lifetime. While that probably sounds extravagant to some, to me it seems like a reasonable sum in exchange for the daily moment of solace and enjoyment and well-being kombucha has provided.

A few months ago for a writing class I endeavored to write a humorous, lighthearted piece about my “addiction” to kombucha. In doing research for the piece, I learned that the health benefits of kombucha are scientifically unproven. And then that light-hearted piece turned into this more serious essay.

While studies do show that probiotic foods (such as kombucha) aid digestion and help maintain intestinal health, ascribing these benefits to kombucha is an act of inference. A 2014 academic journal article elaborates: “Most of the benefits were studied in experimental models only and there is a lack of scientific evidence based on human models.”

Until then, I genuinely believed kombucha made me feel better. When I drank it, a sense of calm and ease washed over my body, particularly my mind and stomach. And I’d read research about how the health of your brain stems from the health of your gut, and as such, probiotics (like kombucha) can play a role in improving mental health. Being no stranger to the blues, I viewed kombucha as one way to keep the lows at bay. In the words of Hippocrates: “Let food be thy medicine, and medicine be thy food.”

Upon realizing the dearth of evidence for kombucha’s purported health benefits, I felt betrayed. Kombucha had been part of my daily routine—both for pleasure and for keeping myself well—for eight years. But here’s the thing: Despite my newfound knowledge and the resulting sense of betrayal, my cravings didn’t stop, and so I kept drinking it. And that’s when I began to wonder if I had a problem.

Was I actually addicted to kombucha? Psychology Today describes addiction as “a substance or activity that can be pleasurable but becomes compulsive and interferes with ordinary responsibilities and concerns.” While I didn’t think kombucha interfered with my everyday life, a friend pressed me to be honest. “You used a date to get a SCOBY, missed work because it made you sick, and spent thousands of dollars that you could have invested in other things.”

Well, true. I did sense my dependence on kombucha wasn’t normal, and this caused shame which at times led me to hide my habit. When I started dating my boyfriend, I mustered all my willpower to stop myself from darting into Walgreens or Whole Foods to pick one up. I eventually came out to him and offered him a sip. When he liked it—and didn’t tease me about how much I drank—my heart swelled with relief.

While one part of me thought my kombucha habit wasn’t normal, another part of me resisted giving it up. Wasn’t being addicted to kombucha better than being addicted to martinis or cigarettes or video games? Plus, drinking kombucha was part of my identity; something people knew me for: a coworker once ordered a delivery of kombucha for my birthday, and I’ve hosted parties thematically dedicated to kombucha cocktails. And even though the health benefits of kombucha were unproven, the drink (perhaps by placebo effect) made me feel better. So I wondered: Is an addiction by definition a detriment to health and happiness, or can it be a good thing?

While considering these questions, my boyfriend and I decided to create a monthly budget to increase our savings. “I’m willing to cut any expense but kombucha,” I said. “I’ll give up drinking alcohol, or spend less money on clothes. Anything.”

“For this to work,” my boyfriend said, “I think we need to be willing to at least consider all expenses, no exceptions.”

At first I felt angry. But then I realized he was right. Especially considering the lack of evidence for kombucha’s benefits, did I really need to insist on my daily habit?

Partly due to the budget project, and partly just to see if I could, I decided to stop drinking kombucha every day. First, I stopped stocking the refrigerator with kombucha. As there was no place to buy kombucha within walking distance of work, anytime I wanted a bottle I needed to get in the car, drive someplace, park, and get one. When no longer aided by convenience, each time I thought about kombucha I had to think about how bad I really wanted it.

At first, every day I didn’t have it I wanted it. But then I learned to sit with the wanting. And then I began to like the confidence that came with not feeling dependent on a substance. Once I recognized the meaning I ascribed to the drink—I thought I needed it to feel good, and to indulge without guilt—it was easier to look for other ways to fulfill that need. I realized I could have good days—and great days—without it. I still drink kombucha, but not every day, and not with the same sense of need.

A few weeks ago I had a big presentation at work. I normally manage my public speaking anxiety by drinking a bottle of kombucha beforehand to soothe my nerves. The evening before my presentation, I started walking to the store to get some to bring with me the next day. Mid-walk, I turned around and came home.

The next morning, I stepped up to the podium. I was fine—even great—without it.

Why America needs a new approach to school desegregation

Getty/recep-bg

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Despite all the time and effort invested desegregating the nation’s schools over the past half century, the reality is America’s schools are more segregated now than they were in 1968.

Keep that statistic in mind as the nation marks the 64th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education – the 1954 Supreme Court decision that famously mandated the desegregation of U.S. public schools.

If the vision of educational fairness expressed in the Brown decision is to be achieved, the nation must deal with the underlying driver of racial segregation in schools: the inclination of white citizens to hoard educational resources.

I make these arguments as one who has studied school segregation up close for over a decade.

Racial segregation has proved resilient over the last half century. It circumvented court orders and reappeared in housing patterns shaped by school zoning policies. It adapted by moving down to the classroom level to take the form of tracking students into gifted and talented programs or Advanced Placement classes. It has become alloyed with economic segregation so that low-income students and students of color end up concentrated in the same schools. The consequences have been predictably dire for students relegated to these increasingly underfunded and racially isolated schools.

Why school segregation persists

The historical record shows that the desire for predominantly white educational spaces has undermined desegregation orders from 1954 to the present. For example, willfully resistant interpretations of the charge to desegregate “with all deliberate speed” in Brown v. Board delayed substantive action on school segregation for over a decade.

This resistance has only increased in sophistication and effectiveness over time. Carefully choreographed legal and political strategies slowed desegregation of schools. The 1992 Freeman v. Pitts Supreme Court decision made it easier to lift desegregation orders and opened the way for a national swing back toward racial segregation in schools.

This new segregation is not directly enforced by law, but indirectly through school zoning, housing patterns, and recently by neighborhood secessionist movements.

All of this permits affluent white families to continue to monopolize premium educational resources.

Charter schools have not been able to slow this resurgence of school segregation. Neither did the federal No Child Left Behind law. In fact, there are reasons to believe both have made segregation worse.

Corrosive effects of segregation

Students of color in racially isolated schools experience lower academic outcomes. Their dropout rates increase.

My own research has shown how school segregation communicates corrosive messages to students of color. My colleagues and I spent 10 years interviewing students in an Alabama school district that had its federal desegregation order lifted. These children watched as the district’s predominantly white leadership moved immediately to rezone and resegregate their schools.

Students assigned to the district’s underresourced all-black high school reported concluding that they were regarded as “bad kids,” “garbage people,” or “violent or something,” and therefore not worthy of investment.

Perhaps worse, the black students in the newly resegregated school read the harm being done to them as intentional and often saw no hope of redress. One student remarked: “I feel like this is an injustice, the way we were brought here to fail. And now it is becoming a reality. I think five or 10 years more down the line it’s going to be horrible. Seriously, it’s going to be horrible.”

Where schools have been desegregated, the negative academic effects are significantly reduced. Rucker Johnson, associate professor in the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley, has found that desegregation raises income levels and wealth accumulation across generations, and even improves health outcomes across students’ lifespans.

The psychological effects of desegregation, however, are more complicated. Desegregating schools provides more balanced access to resources, but puts students of color in schools staffed primarily by white educators who still often harbor implicitly and explicitly racist attitudes. Children of color pay a price for this.

For white students, school desegregation has no measurable negative effects on academic performance and graduation rates. Meanwhile, school desegregation provides many positive social effects for all students, including reduction of racial prejudice and generally becoming more comfortable around people of different backgrounds.

Possible remedies

So, what lessons have been learned from America’s failed efforts to desegregate its public schools?

The first is that the desire for racially segregated schooling evolves in response to efforts to promote racial equity in schools. This implies that lawmakers should not presume integration of schools will help communities “outgrow racism.” Desegregation orders, where needed, need to be permanent.

Second, geography has always been used as a proxy to preserve school segregation. Communities need housing policies that effectively inhibit the creation of racially and economically segregated neighborhoods.

Third, adequate and equitable funding is needed across school districts. There is nothing magically educational about sitting next to a white person in school. The primary problem is the way resources disproportionately follow white bodies.

Finally, the teaching profession must be fully diversified. Fifty-one percent of students entering public schools are persons of color, but more than 80 percent of teachers are white. Placing children of color in predominantly white schools and counting on color-blind professionalism to protect them is not an adequate plan. Research conducted by my colleagues and I reveals how this approach misunderstands the way racism operates and leaves children of color exposed to psychological and pedagogical harm.

America’s school systems need to recruit, support and retain teachers who identify with the experiences of the students they serve. Additionally, all teachers must be educated to recognize the constantly evolving forms of segregation in the nation’s school systems, to protect students from its worst effects and to join the struggle to build a better system.

Jerry Rosiek, Professor of Education Studies, University of Oregon

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

David Bowie, up close and personal: How the “David Bowie Is” exhibit was made

AP

The Brooklyn Museum’s current exhibit “David Bowie Is” brings David Bowie's work and spirit to life like never before with unprecedented access to his personal archive. The exhibit is open at the museum through July 15.

Matthew Yokobosky, chief designer and director of exhibition design at the Brooklyn Museum, sat down for "Salon Talks" this week to discuss the traveling multimedia exhibit’s last stop in Brooklyn and how it spotlights Bowie’s unorthodox and unique career through music, movies and pop culture.

This is a pretty exciting exhibit. It’s hard to get into and I enjoyed it very much. I was interested in the fact that it doesn’t follow the typical, chronological order that you’d expect of an exhibit of somebody’s life's work. It feels kind of more organic. Tell me about how the flow of this exhibit was conceived.

The first part of the exhibition is really about his history. Where he was born, what England was like in the 1950s. That goes up until his first hit, which is "Space Oddity" in 1969. Then from there it just breaks chronology completely and we go into an area where you learn about David’s songwriting techniques and about how he created the characters he did during the 1970s. Then, after that, you’re really hitting it into his media sound. You’re following his early music videos, his 1980s music videos which we all know, his career on Broadway, his career in film, and then of course, on stage -- we have a big concert moment at the end.

When I was there, I noticed that there was a wide range of visitors. There were people I think like me who are big David Bowie-heads and then there were people who were more casual fans. How do you balance the needs of both experts and newbies?

We spent a lot of time working on the labeling for the exhibitions. We have readers from the education department. We have readers who are arts scholars. We have people from visitor’s services. They all read the labels and information and they give a lot of feedback. We spent a lot of time working it out so that if you were new to David Bowie, you’d learn about his career. If you’re a big megafan like I think you are, we give a lot of new information also, a nice mix.

Watch the full interview on David Bowie

A Salon Talks conversation with curator Matthew Yokobosky

Yeah. It was fun. Audio is obviously a big aspect of this exhibit. You actually walk around with headphones on. Can you talk about how the sound was designed for this exhibit?

When you come to the exhibition, we give you a set of these amazing, sound-cancelling headphones by Sennheiser — plug, plug. They’re state-of-the-art headphones. And as you walk through the exhibition, the sound is changing with you. The audio system knows where you’re at. Most of the time it changes as you’re approaching a new video, which might be a documentary or it might be a music video. The trick was to have the songs on and off proximity to each other so that as you’re walking from one it would transition. There’s a lot of wiring in the floor, in the ceiling, to make all that magic happen.

The audio, as you said, is like the exhibition in that it’s not strictly chronological. It goes back and forth and it’s a bit more dramatic. One of the great features of the audio tour is that we had Tony Visconti, who produced 14 of David Bowie’s albums, do a mega mix for the exhibition. It’s the only place that you can hear it. He went back to the master tapes of 60 of David Bowie’s songs and went in with scissors and created this amazing mix track.

That’s amazing. I heard that and was impressed but I didn’t know that Tony Visconti did it.

He came into the talk at the museum a couple of weeks ago and yeah, he really went into depths about what it was like working with David on all those major albums. Then last week, we had Mick Rock in, who took a lot of the early photographs. He was the official David Bowie photographer for 20 months during the Ziggy Stardust "Aladdin Sane" [period]. And this week, tomorrow night actually, we have Kansai Yamamoto, who’s flying in from Tokyo and was David’s costume designer for Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane. We’re all hoping that’s a fantastic and interesting conversation.

A lot of his work is in the exhibit, right?

There’s eight costumes by Kansai in the show. When David became aware of Kansai, Kansai had just done a fashion show in London and he was supposed to be the first major Japanese designer to do a presentation in London. David saw the show and he went to a store that was selling Kansai Yamamoto and saved up his money until he could get one of the outfits. Kansai’s stylist found out that he was wearing Kansai and so they came to New York to Radio City Music Hall when David was premiering "Aladdin Sane" and they met backstage. And when David went to Tokyo, Kansai had made all these amazing outfits for him.

There’s so much about David Bowie. It’s very hard to narrow it down. But I was impressed by how much the exhibit kind of focuses on science fiction. How much did science fiction impact David Bowie’s work?

I think it’s both science and science fiction. In the late 1960s, the first photograph was taken of Earth from outer space, which was by astronaut Bill Anders and it was December 1968. No one had seen what the Earth looked like from outer space before. This was the first photograph and it was on the cover of the London Times in January and David wrote the lyrics for "Space Oddity," which was "planet Earth is blue / And there’s nothing I can do." It’s based on that photograph.

At that time he was also obsessed with Stanley Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" and so "Space Oddity" is really just a word play on "Space Odyssey."

He invented that character of Major Tom, the astronaut at that point, which pops up again and again throughout his whole career. That was important to him. Stanley Kubrick's other movies, [such as] "A Clockwork Orange" were also very influential, especially on the costume designs. Then he kind of goes in and out of science fiction and fantasy throughout the career until you get to "Black Star," where, if you see the music video for "Black Star," you see the astronaut die. I think he’s a lot of an adventurer and wanting to just kind of explore and explore and fantasize about what the future might be like.

In other albums, for example, "Station to Station," he was a character of the train conductor at the beginning of it. A lot of this is all very interesting because David was also afraid to fly. Often times, he would choose to take a boat instead of flying in an airplane. And you’ll read different passages where sometimes he's OK with flying and other times he’s not. At the end of the Ziggy Stardust/Aladdin Sane tour, he was in Tokyo and everybody was flying back to London and he decided that he was going to take the train. He went on the Trans-Siberian railroad from Asia all the way back to London. It was very important trip for him because it went through to Berlin, which was where he ends up going in 1976 to make the Berlin Trilogy. But he first saw it on that trip in ’73.

The exhibit really does spend a lot of time on the Berlin years. Why do you think German culture had such a hold on Bowie’s imagination?

He first got interested in German film and theatre when he saw a production of "Cabaret" in London starring Judi Dench.

It must have been amazing.

Yeah. Sounds incredible. Right? I wish I was there. "Cabaret" is set in 1920s in Berlin and it features a lot of that chiaroscuro lighting, the white shirts with black jackets. And then, when he turned 27, there’s a singer named Amanda Lear who took him to see [the 1927 Fritz Lang film] "Metropolis" for his birthday. It’s kind of an interest in "Cabaret," kind of an interest in German expressionist film, and the design of those things really came out in a number of different ways for him.

When he was working on the "Diamond Dogs" tour, the set was based on "Metropolis," and we have a model of it in the exhibit. Later on, when he’s working on the Berlin Trilogy, he’s using a lot of the lightning techniques that you would find in these 1920s films. It was a big contrast, the German expressionist black and white with the more colorful, flamboyant Ziggy Stardust. Those were kind of two ends of that he was contrasting the whole time.

Bowie had a lot of collaborators over the years — we’ve already talked about Tony Visconti — including, obviously most famously, the producer Brian Eno. How do you incorporate this important aspect of his work? Because I feel like you always included other people as much as [the exhibit] could.

He was one of those people that always had their ear to the ground. Always trying to find out who was new, who was next, who was most interesting. With Brian Eno, the great thing about it was that Brian was also very curious all the time. They started working together because David liked his album "Discreet Music," which is just before he does "Music for Airports," which are just landmark albums. When they got into the studio, they just became a bubble, threw everything out the window and tried new things. They called up Robert Fripp and [said] do you have any interesting guitar things that you’re making? Do you want to come to Berlin and work with us? We’re in a studio working and this isn’t quite working out. So they used those oblique strategy cards which were designed for artists who are having artistic blocks to kind of try something new. It would be like using unexpected color or try two musicians swapping instruments and just play even though you don’t now how to play them.

Brian Eno brought a lot of experimentation into the process. But, I think overall David was always looking for something that was intriguing. He didn’t want his music or his look to just look like anybody else’s, he always wanted to have its own unique flavor and texture.

I don’t know if you’ve been following this story about hip-hop producer and rapper Kanye West who has been running around saying provocative things about Donald Trump. It reminded me of how Bowie would do some of that in the ’70s. He said he was intrigued by fascism. He would claim that he was gay when he wasn’t. Do you see similarities in their behaviors and do you think there’s anything we can kind of learn from that period of Bowie’s life?

I think people go through different phases in their life where they're interested in certain things and they don’t know why. You’re just kind of attracted to them and you want to read about it and explore it. I think people probably have that a lot with the internet today. It’s so easy if you find out about something you want to know about; you just Google it and it will come up. But it wasn’t always like that. Back in the ’70s, if you wanted to look and find out about something avant-garde or something that was kind of underground, you had to either go to a library with sunglasses on, or you had to be a little bit discreet. I think David was very interested in people mostly, and then he was always intrigued by how they worked. He was going to do a production of "1984" and couldn’t get permission to do that, but that’s very heavy book to work on.

I think he was definitely flirting with sexuality in the early '70s, both with his look and the things that he said, and there’s always a little bit of truth in everything.

It’s not always like a hundred percent or . . . it could be like 80/20 or something. Points of view changed, too. I mean —

Obviously, he regretted saying some things.

He regretted saying some things like Kanye West might regret saying some things later on. It’s tricky. But it gets you in the news. They’re definitely the things that people write about [which] come up again later. Certainly, later on, David I think regretted some of the things that he might have said in interviews. But sometimes he made up things for interviews too, like even if it’s about the most benign thing. He didn’t want to answer the same question the same way again. He would invent a new answer and those would become mythological and people would keep reprinting them and he would evidently just allow it to keep being wrong. He wouldn’t correct it.

That’s amazing and just so counter to a lot of how we think of celebrity working now. Everyone has been so literal now, I think.

Yeah. They try to [have] this façade of being down to earth and honest about every moment. Even reality TV is scripted. You’re not really seeing the Kardashians at home.

This exhibit has been around the world for the past five years. Why is it making its final stop in Brooklyn?

The exhibit started in London and its been to Paris, Berlin, Tokyo, Sao Paulo, Chicago, and at the beginning there was always a little bit of a thought that the exhibition would kind of begin where he began, and end where he lived at the end of his life. He lived in New York for 20 years, which might be the place that he lived the longest.

I went to see the show in 2013 in London. And I'm a big cheerleader of David Bowie. We started these discussions about it. David had done an acoustic guide for the Brooklyn Museum in around 2000. We had a big exhibit called "Sensation." He was the voice of the audio tour and that began our relationship with him. We were very happy to be the final venue for the tour.

Nevada marijuana grower questioned for his connection to Michael Cohen

AP/Andrew Harnik

A licensed marijuana grower in Nevada named Semyon "Sam" Shtayner is under scrutiny for his ties to Michael Cohen, the president's personal attorney and fixer. Local officials in Henderson, Nev., recently questioned Shtayner, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Shtayner informed officials that Cohen did not have any involvement with his marijuana enterprise, but did say that Cohen and his family had loaned him some money to help buy taxi medallions.

Cohen “absolutely and unequivocally has no connection to my Marijuana Facilities,” Shtayner wrote in a statement.

The genesis of their relationship began when Shtayner and Cohen's father-in-law both immigrated from Ukraine and settled in New York, where they both worked in the taxi business.

Shtayner provided a legal statement to city officials explaining his financial relationship with Cohen. According to records reviewed by the Journal, Shtayner borrowed as much as $6 million from Cohen in 2014 and 2015. Shtayner claimed he invested in the pot business because of the downturn of the taxi industry.

Shtayner's connection with Cohen aroused the FBI after the bureau raided Cohen's office and home in earlier April and found records pertaining to Shtayner. The Wall Street Journal reported that the FBI specifically sought documents relating to Shtayner and his wife.

Investigators have been probing Cohen for possible bank fraud and campaign-finance violations. Cohen has denied any wrongdoing at this point.

Shtayner appears to have satisfied officials in Henderson, who told the Journal. “Staff are no longer looking into anything further related to Mr. Shtayner unless new information is brought to our attention."

Cannabis in Nevada became legal for recreational use on January 1, 2017, having been legalized by ballot initiative in 2016. Trump's attorney general, Jeff Sessions, issued a memo earlier this year that proposed a federal marijuana crackdown in states that had legalized the substance. States that have legalized pot immediately protested these efforts, resulting in Trump conceding on the issue.

An excerpt from “RAF: The Birth of the World’s First Air Force,” by historian Richard Overy

Getty Images

The Royal Air Force was formally activated on 1 April 1918, April Fools’ Day. It was an inauspicious date on which to launch the world’s first independent air force, and there were hesitations about choosing it. Perhaps the army and the Royal Navy, both for their own reasons wary of the fledgling service, quietly approved the choice of date, hoping that a separate air force would soon prove itself a joke. They certainly both hoped that the RAF and the new Air Ministry it served would not last beyond the end of the war. In this they were soon to be disabused. The RAF survived victory in 1918 and has survived regular calls for its dissolution since, and now celebrates an uninterrupted hundred years.

The birth of the RAF was surrounded by argument and controversy. There already were two air services fighting Britain’s aerial contribution to the First World War: the Royal Naval Air Service and the army’s Royal Flying Corps. The establishment of an entirely new branch of the armed forces was a political decision, prompted by the German air attacks on London in 1917, not a decision dictated by military necessity. The politicians wanted a force to defend the home front against the novel menace of bombing, amidst fears that the staying power of the population might be strained to breaking point by the raids. From the politicians’ viewpoint, the air defense of Great Britain was one of the principal charges on the new force, and it is the defense of the home islands twenty-two years later in the Battle of Britain that is still remembered as the RAF’s ‘finest hour’. The reality of the past hundred years has been rather different. The RAF has principally served overseas and for most of the century was a force dedicated to bombing and to ground support for the other services. This future was anticipated in the final seven months of combat in 1918 when the RAF, building on the legacy of its two predecessors, contributed substantially to the air support of Allied armies in Western Europe and the Middle East, and organized the Independent Force (independent of the front line) for the long-range bombing of German industrial towns. By the time of the Armistice in November 1918, the shape of RAF doctrine was already in firm outline, even if its future as a separate force was thrown into doubt once the fighting was over.

* * *

In 1908, only five years after the Wright brothers’ first powered flight in December 1903, the British novelist H. G. Wells published The War in the Air, in which he imagined a near future when aircraft would decide the outcome of modern war. The novel’s hero, Bert Smallways, watching the destruction of New York by German airships, reflects on Britain’s vulnerability: ‘the little island in the silver seas was at the end of its immunity.’ Aircraft changed the whole nature of war. Writing twenty-five years later in his autobiography, Wells noted with a grim satisfaction that he had written the novel ‘before any practicable flying had occurred’, but he had been correct to predict that aircraft would abolish the traditional divide between a military front line and the home population, and so erode the distinction between combatant and civilian. With the arrival of aircraft, Wells concluded, war was no longer a ‘vivid spectacle’ for the home front, watched like a cricket or baseball match, but a horrible reality for ordinary people. Only seven years separated Wells’s novel from the first bombs to fall on British soil and only ten from the establishment of the Royal Air Force, set up to try to protect Britain’s vulnerable people from an air menace described so graphically by Wells at the dawn of the air age.

One of the many remarkable consequences of the coming of powered flight was the speed with which the armies and navies of all the major powers sponsored the development of aircraft —both dirigibles and aeroplanes — for military purposes. The technical development of aircraft in the decade following the Wright brothers was exponential and knowledge of the new invention universal, but for the British people, all but immune to invasion for a millennium, aviation posed a particular strategic threat. This perhaps explains why the evolution of military air power in Britain in the age of the Great War was strongly influenced by public opinion and political pressure and was not solely a result of the military need to respond to innovation. Critics at the time and since have blamed military conservatism for the slow development of organized air power in Britain before 1914 and have assumed that public disquiet, noisily expressed in the popular press, prompted a grudging army and navy to explore the use of aircraft despite harbouring strong prejudices against their use.

The army and navy were, in truth, less narrow-minded than the popular image suggests. The first powered flight in Britain was only made in 1908 by A.V. Roe, who managed a distance of just 60 yards (55 metres). A mere three years later the army began developing a military air arm when the Royal Engineers established an Air Battalion consisting of a company of airships (still considered a major factor for the future of air warfare) and a company of aeroplanes. On 13 April 1912 the King issued a Royal Warrant for a new service, and a month later, on 13 May, the battalion was replaced by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), the direct ancestor of the future RAF. The Corps consisted of a military wing, a naval wing, a Central Flying School and a reserve, loosely controlled by an Air Committee with representatives from the two services.3 A small cluster of soldiers and seamen who had qualified as pilots joined the force. The RFC adopted a modified khaki army uniform and the Latin motto Per ardua ad astra (‘Through adversity to the stars’), still the motto of today’s air force. The intention was to keep a unified corps serving both the army and the Royal Navy, but when Winston Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty in 1913, he exploited his personal enthusiasm for flight to insist that the navy should have a separate air force. The first commander of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was Captain Murray Sueter, the director of the Admiralty’s Air Department. In July 1914 the RNAS was formally divorced from the RFC just as Europe was about to plunge into war. A year later the Admiralty assumed full responsibility, a bifurcation that was to lead to endless friction between military and naval aviation until united as awkward rivals in the RAF in 1918. In the same month that the RNAS was created, a Military Aeronautics Directorate was established by the War Office to oversee the military wing of the RFC under one of the pioneers of army aviation, Major-General David Henderson.

Both the navy and the army understood that aircraft were likely before long to become assets indispensable to their operations. ‘In view of the fact that aircraft will undoubtedly be used in the next war,’ wrote the Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1911, ‘we cannot afford to delay . . .’ The army Field Service Regulations published in July 1912 were the first to contain reference to the use of aircraft, and in the 1912 field exercises two airships and fourteen aircraft were used for reconnaissance purposes. The observer in one of the aircraft was Major Hugh Trenchard, the man later regarded as the ‘father of the RAF’; commander of one of the armies in the exercise was Douglas Haig, who later formed a close working relationship with Trenchard on the Western Front. By the summer of 1914, on the eve of the Great War, a major RFC training exercise saw experiments in night flying, flight at high altitudes, aerial photography, and the first attempt to fit machine-guns to an aircraft. The RFC Training Manual issued the year before stressed the need for offensive aviation well before the means were available.

It was nevertheless true that the RFC was a considerable way behind the development of aviation elsewhere. In France, Austria and Germany rapid progress had been made in military aeronautics; the small Bulgarian air force was responsible for inventing the first modern aerial bomb; and in 1914 the Russian engineer Igor Sikorsky developed the multi-engine Ilia Muromets Sikorsky Type V aeroplane, the first modern heavy bomber. British services were slower to respond, partly because they did not anticipate a major European war, partly because public and government were fixated on the battleship arms race, and partly because the British army was so much smaller and less politically powerful than its Continental rivals. When war broke out in August 1914, the RNAS possessed only six airships and ninety- three aeroplanes, many of which were unserviceable, and could field only one flying squadron (the word chosen in 1912 to describe the small air units being formed). The RFC arrived in France with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) with just four squadrons totalling approximately sixty aircraft. There were 105 officers and 755 other ranks. The French army put twenty-three squadrons in the field, the German army twenty-nine.

The first two years of war provided a steep learning curve for air forces on all sides. Aircraft technology improved all the time, but aircraft remained fragile objects, subject to frequent damage and repair. They were constructed chiefly of wood and fabric, carried a heavy metal engine and were held together with wire or wooden struts. Some idea of the nature of early aviation engineering can be gleaned from the trades assigned to each RFC squadron, which included two blacksmiths, six carpenters, four coppersmiths, 21 riggers and four sailmakers. Flying was an exceptionally hazardous undertaking with few base facilities, primitive navigational instruments, and the constant threat posed by sudden changes in the weather. Naval aviators were occasionally sent off over the sea never to be seen again. Diaries kept by servicemen in the RFC talk repeatedly of the cold. Aloft in an open cockpit, thousands of feet up, the temperature was debilitating. The RFC Training Manual in December 1915 listed the clothing pilots and observers were expected to wear to combat the intense cold: two pairs of thick long drawers, a woollen waistcoat, a British ‘warm coat’ with a waterproof oilskin over it, a cap with ear pads, two balaclavas, a flying helmet, goggles, a warm scarf, and two pairs of socks and gloves.

Although the RFC manuals stressed that aircraft could accomplish little or nothing in ‘heavy rain, fog, gales or darkness’, pilot records show that flying continued even in cloudy, cold conditions with limited visibility. Advice on weather in the air force Field Service Book was rudimentary: ‘Red at sunset . . . Fair weather’; ‘Red at dawn . . . Bad weather or wind’; ‘Pale yellow at sunset — rain’. Crashes and accidents were as a result routine occurrences. British air forces lost 35,973 aircraft through accident or combat during the war, and suffered the loss of 16,623 airmen, either dead, or severely injured, or prisoners of war. A diary kept by an air mechanic during the later war years gives a vivid description of a typical accidental death:

Lt. J. A. Miller was taking off in an S.E.5 when he crashed, his machine caught fire & he was burned to death, we were powerless to help him, the ammunition in his guns & boxes was exploding & bullets were flying around, soon the fire died down and his charred remains were taken out of the machine & buried in a wood close by, a wooden cross made out of a propeller marks his grave.

The situation in the first years of the war was not helped by the poor level of training of novice pilots, many of whom would have only 20 hours flying time or less before being posted to operations, where only two hours would be spent learning to fly the frontline aircraft assigned to them. A young John Slessor, later Chief of the Air Staff in 1950, recalled that he was commissioned as an RFC pilot with just twelve hours solo flying, and was fortunate to survive. There were no parachutes.

Adapted excerpt from "RAF: The Birth of the World's First Air Force" by Richard Overy. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Wildfire risks are high again this year — here’s what travelers need to know

AP Photo/Esteban Felix

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Memorial Day marks the traditional opening of the summer travel season. This year the American Automobile Association projects that more than 41.5 million Americans will hit the road over Memorial Day weekend, nearly 5 percent more than last year and the most in a dozen years.

For many years, AAA has urged drivers to prepare for trips through steps such as testing their car batteries, checking for engine coolant leaks, and making sure their tires are in good shape. The group also recommends packing a mobile phone and car charger, a flashlight with extra batteries, a first-aid kit, a basic toolkit, and drinking water and snacks for all passengers.

But travelers should also think about conditions beyond their cars. As coordinator of Colorado State University’s Veterinary Extension programs, I help people in rural and urban communities manage all kinds of threats that can affect them and their animals, from disease to disasters. When people travel in unfamiliar places, far from their social safety nets, they should know what challenging conditions exist and prepare appropriately. In particular, anyone visiting the western United States this summer should understand risks associated with wildfires, since once again the risk of fires is high in many areas.

Understanding fire conditions

The 2017 wildfire season was one of the most challenging years on record. More than 71,000 wildfires burnt over 10 million acres. Federal agencies spent nearly US$3 billion on fire suppression, and 14 firefighters were killed in action.

This year the U.S. Forest Service expects another above-average fire season. Many parts of the Southwest that depend on winter precipitation for moisture are dry. Coupled with above-average growth of grasses last year, conditions are ripe to turn a harmless spark into flames. Wildland fire potential is forecast to be above normal through August across portions of the Southwest, Great Basin, Southern California and the Pacific Northwest.

Wildland fires are fickle beasts that behave erratically, depending on wind speed and direction and the landscape over which they travel. If you are close to a fire, it can be difficult to tell which way the fire is moving. Firefighters, police and other first responders have access to information that defines the scope of a fire and the potential pattern of its movement. They use this information to define evacuation areas to keep people safe. It is essential to respect these boundaries.

Travelers in unfamiliar territory should research hazards they may face (including events such as blizzards, floods and tornadoes, as well as wildfires), and prepare accordingly. Here are some basic recommendations:

Know where you are. GIS systems are convenient, but Siri may not always be available. Carry paper maps that you know how to read.

Share your exact travel plans with friends or family. Inform them when you change course. Someone else should know where you think you are.

Develop situational awareness. Pay attention to your environment: Seeing or smelling smoke is significant. Avoid rising rivers and flooded roads.

Have a communication backup plan if cell service is not available. Sign up for reverse 911, subscribe to an emergency communications service such as Everbridge, or listen to AM channels advertised on road signs in rural communities.

Check weather reports and respect red flag advisories.

Respect warnings from local emergency managers and cooperate with first responders.

The wildfire danger is high today and tomorrow across parts of northern Arizona.

It only takes one spark to start a raging wildfire as wind speeds increase and conditions remain very dry, so please use caution! #abc15wx #azwx pic.twitter.com/JJwAZvOGef

— Iris Hermosillo (@IrisABC15) May 16, 2018

The human factor in wildfires

People trigger most wildfires in the United States. According to a 2017 study, 84 percent of wildfires federal and state agencies were called to fight between 1992 and 2012 were ignited by humans. Wildfires can also be ignited by lightning or sparks from railroads and power lines.

People start fires by discarding cigarettes carelessly, leaving campfires unattended or inadequately extinguished, and losing control of crop fires and prescribed burns. The 2017 study calculated that human actions have tripled the length of the national wildfire season, extending it into spring, fall and winter.

The U.S. Forest Service has been educating Americans about their role in preventing wildfires since 1942, when Disney lent it images of Bambi the fawn and his forest friends for an educational poster. The campaign was very popular and confirmed that an animal was an effective fire prevention symbol. Because Bambi was only on loan, the agency had to find a new animal symbol. A majestic, powerful and appealing bear fit the bill.

The Smokey Bear Wildfire Prevention campaign, the longest-running public service advertising campaign in U.S. history, started in August 1944. The initial poster depicted a bear pouring a bucket of water on a campfire. In 2001, Smokey’s catchphrase was updated to “Only You Can Prevent Wildfires.”

Smokey’s message to prevent unwanted and unplanned outdoor fires is as relevant and urgent today as it was in 1944. By learning about campfire safety, safe management of backyard debris burns, and protecting houses and property from wildfire, Americans can make themselves safer, both on the road and at home.

Smokey’s message to prevent unwanted and unplanned outdoor fires is as relevant and urgent today as it was in 1944. By learning about campfire safety, safe management of backyard debris burns, and protecting houses and property from wildfire, Americans can make themselves safer, both on the road and at home.

Ragan Adams, Coordinator, Veterinary Extension Specialist Group, Colorado State University

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

May 19, 2018

How to set screen rules that stick

Getty Images

This post originally appeared on Common Sense Media.

In many homes, getting kids to turn off their cell phones, shut down the video games, or quit YouTube can incite a revolt. And if your kids say they need to be online for schoolwork, you may not know when the research stops and idle activity begins.

In many homes, getting kids to turn off their cell phones, shut down the video games, or quit YouTube can incite a revolt. And if your kids say they need to be online for schoolwork, you may not know when the research stops and idle activity begins.

When it comes to screen time, every family will have different amounts of time that they think is "enough." What's important is giving it some thought, creating age-appropriate limits (with built-in flexibility for special circumstances), making media choices you're comfortable with, and modeling responsible screen limits for your kids. Try these age-based guidelines to create screen rules that stick.