Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 68

May 22, 2018

How to end partisan gerrymandering

Orhan Cam, fpdressvia Shutterstock/Salon/Benjamin Wheelock

This originally appeared on Robert Reich's blog.

One of the biggest challenges to our democracy occurs when states draw congressional district lines with the principal goal of helping one political party and hurting the other. It’s called “partisan gerrymandering.”

Unlike racial gerrymandering — drawing districts to reduce the political power of racial minorities, which the Supreme Court has found to violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment — partisan gerrymandering would seem to violate the First Amendment because it punishes some voters for their political views.

In North Carolina in 2016, for example, Republicans won 10 of the state’s 13 House seats with just 53 percent of the popular vote.

In the 2018 elections, because of partisan gerrymandering, Democrats will need to win the national popular vote by nearly 11 points to win a majority in the House of Representatives. No party has won this margin in decades.

So what can be done?

The Supreme Court will soon decide on the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering. Hopefully, the Court will rule against it. But regardless of its decision, here are two other ways to abolish it:

First, state courts could rule against partisan gerrymandering under their state constitutions, as happened this year in Pennsylvania — where the state court invalidated a Republican congressional map that gave Republicans 13 out of 18 congressional seats even though the state is about evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans. The state court implemented its own map for the 2018 election, creating districts that are less biased in favor of Republicans.

Second, states can delegate the power to design districts to independent or bipartisan groups. Some states, like California, have already done this.

But if you want your state to end gerrymandering, you’re going to have to get actively involved, and demand it.

After all, this is our democracy. It’s up to us to make it work.

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

May 21, 2018

I teach refugees to map their world

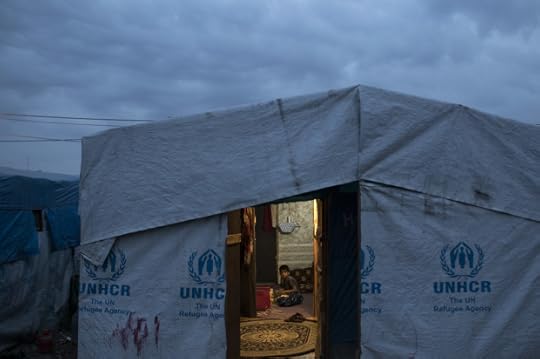

AP Photo/Felipe Dana

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

I first visited the Zaatari refugee camp in early 2015. Located in northern Jordan, the camp is home to more than 80,000 Syrian refugees. I was there as part of a research study on refugee camp wireless and information infrastructure.

It’s one thing to read about refugees in the news. It’s a whole different thing to actually go visit a camp. I saw people living in metal caravans, mixed with tents and other materials to create a sense of home. Many used improvised electrical systems to keep the power going. People are rebuilding their lives to create a better future for their families and themselves, just like any of us would if faced with a similar situation.

As a geographer, I was quickly struck by how geographically complex Zaatari camp was. The camp management staff faced serious spatial challenges. By “spatial challenges,” I mean issues that any small city might face, such as keeping track of the electrical grid; understanding where people live within the camp; and locating other important resources, such as schools, mosques and health centers. Officials at Zaatari had some maps of the camp, but they struggled to keep up with its ever-changing nature.

An experiment I launched there led to up-to-date maps of the camp and, I hope, valuable training for some of its residents.

The power of maps

Like many other refugee camps, Zaatari developed quickly in response to a humanitarian emergency. In rapid onset emergencies, mapping often isn’t as high of a priority as basic necessities like food, water and shelter.

However, my research shows that maps can be an invaluable tool in a natural disaster or humanitarian crisis. Modern digital mapping tools have been essential for locating resources and making decisions in a number of crises, from the 2010 earthquake in Haiti to the refugee influx in Rwanda.

This got me thinking that the refugees themselves could be the best people to map Zaatari. They have intimate knowledge of the camp’s layout, understand where important resources are located and benefit most from camp maps.

With these ideas in mind, my lab teamed up with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and Al-Balqa and Princess Sumaya universities in Jordan.

Modern maps are often made with a technology known as Geographic Information Systems, or GIS. Using funding from the UNHCR Innovation Fund, we acquired the computer hardware to create a GIS lab. From corporate partner Esri, we were obtained low-cost, professional GIS software.

Over a period of about 18 months, we trained 10 Syrian refugees. Students in the RefuGIS class ranged in age from 17 to 60. Their backgrounds from when they lived in Syria ranged from being a math teacher to a tour operator to a civil engineer. I was extremely fortunate that one of my students, Yusuf Hamad, spoke fluent English and was able translate my instructions into Arabic for the other students.

We taught concepts such as coordinate systems, map projections, map design and geographic visualization; we also taught how to collect spatial data in the field using GPS. The class then used this knowledge to map places of interest in the camp, such as the locations of schools, mosques and shops.

The class also learned how to map data using mobile phones. The data has been used to update camp reference maps and to support a wide range of camp activities.

I made a particular point to ensure the class could learn how to do these tasks on their own. This was important: No matter how well-intentioned a technological intervention is, it will often fall apart if the displaced community relies completely on outside people to make it work.

As a teacher, this class was my most satisfying educational experience. This was perhaps my finest group of GIS students across all the types of students I have taught over my 15 years of teaching. Within a relatively short amount of time, they were able to create professional maps that now serve camp management staff and refugees themselves.

My experiences training refugees and humanitarian professionals in Jordan and Rwanda have made me reflect upon the broader possibilities that GIS can bring to the over 65 million refugees in the world today.

It’s challenging for refugees to develop livelihoods at a camp. Many struggle to find employment after leaving.

GIS could help refugees create a better future for themselves and their future homes. If people return to their home countries, maps – essential to activities like construction and transportation — can aid the rebuilding process. If they adopt a new home country, they may find they have marketable skills. The worldwide geospatial industry is worth an estimated US$400 billion and geospatial jobs are expected to grow over the coming years.

Our team is currently helping some of the refugees get GIS industry certifications. This can further expand their career opportunities when they leave the camp and begin to rebuild their lives.

Technology training interventions for refugees often focus on things like computer programming, web development and other traditional IT skills. However, I would argue that GIS should be given equal importance. It offers a rich and interactive way to learn about people, places and spatial skills – things that I think the world in general needs more of. Refugees could help lead the way.

Brian Tomaszewski, Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technologies, Rochester Institute of Technology

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

10 things you don’t know about yourself

pogonici, via Shutterstock

This article was originally published by Scientific American.

1. Your perspective on yourself is distorted

Your “self” lies before you like an open book. Just peer inside and read: who you are, your likes and dislikes, your hopes and fears; they are all there, ready to be understood. This notion is popular but is probably completely false! Psychological research shows that we do not have privileged access to who we are. When we try to assess ourselves accurately, we are really poking around in a fog.

Princeton University psychologist Emily Pronin, who specializes in human self-perception and decision making, calls the mistaken belief in privileged access the “introspection illusion.” The way we view ourselves is distorted, but we do not realize it. As a result, our self-image has surprisingly little to do with our actions. For example, we may be absolutely convinced that we are empathetic and generous but still walk right past a homeless person on a cold day.

The reason for this distorted view is quite simple, according to Pronin. Because we do not want to be stingy, arrogant or self-righteous, we assume that we are not any of those things. As evidence, she points to our divergent views of ourselves and others. We have no trouble recognizing how prejudiced or unfair our office colleague acts toward another person. But we do not consider that we could behave in much the same way: because we intend to be morally good, it never occurs to us that we, too, might be prejudiced.

Pronin assessed her thesis in a number of experiments. Among other things, she had her study participants complete a test involving matching faces with personal statements that would supposedly assess their social intelligence. Afterward, some of them were told that they had failed and were asked to name weaknesses in the testing procedure. Although the opinions of the subjects were almost certainly biased (not only had they supposedly failed the test, they were also being asked to critique it), most of the participants said their evaluations were completely objective. It was much the same in judging works of art, although subjects who used a biased strategy for assessing the quality of paintings nonetheless believed that their own judgment was balanced. Pronin argues that we are primed to mask our own biases.

Is the word “introspection” merely a nice metaphor? Could it be that we are not really looking into ourselves, as the Latin root of the word suggests, but producing a flattering self-image that denies the failings that we all have? The research on self-knowledge has yielded much evidence for this conclusion. Although we think we are observing ourselves clearly, our self-image is affected by processes that remain unconscious.

2. Your motives are often a complete mystery to you

How well do people know themselves? In answering this question, researchers encounter the following problem: to assess a person’s self-image, one would have to know who that person really is. Investigators use a variety of techniques to tackle such questions. For example, they compare the self-assessments of test subjects with the subjects’ behavior in laboratory situations or in everyday life. They may ask other people, such as relatives or friends, to assess subjects as well. And they probe unconscious inclinations using special methods.

To measure unconscious inclinations, psychologists can apply a method known as the implicit association test (IAT), developed in the 1990s by Anthony Greenwald of the University of Washington and his colleagues, to uncover hidden attitudes. Since then, numerous variants have been devised to examine anxiety, impulsiveness and sociability, among other features. The approach assumes that instantaneous reactions require no reflection; as a result, unconscious parts of the personality come to the fore.

Notably, experimenters seek to determine how closely words that are relevant to a person are linked to certain concepts. For example, participants in a study were asked to press a key as quickly as possible when a word that described a characteristic such as extroversion (say, “talkative” or “energetic”) appeared on a screen. They were also asked to press the same key as soon as they saw a word on the screen that related to themselves (such as their own name). They were to press a different key as soon as an introverted characteristic (say, “quiet” or “withdrawn”) appeared or when the word involved someone else. Of course, the words and key combinations were switched over the course of many test runs. If a reaction was quicker when a word associated with the participant followed “extroverted,” for instance, it was assumed that extroversion was probably integral to that person’s self-image.

Such “implicit” self-concepts generally correspond only weakly to assessments of the self that are obtained through questionnaires. The image that people convey in surveys has little to do with their lightning-fast reactions to emotionally laden words. And a person’s implicit self-image is often quite predictive of his or her actual behavior, especially when nervousness or sociability is involved. On the other hand, questionnaires yield better information about such traits as conscientiousness or openness to new experiences. Psychologist Mitja Back of the University of Münster in Germany explains that methods designed to elicit automatic reactions reflect the spontaneous or habitual components of our personality. Conscientiousness and curiosity, on the other hand, require a certain degree of thought and can therefore be assessed more easily through self-reflection.

3. Outward appearances tell people a lot about you

Much research indicates that our nearest and dearest often see us better than we see ourselves. As psychologist Simine Vazire of the University of California, Davis, has shown, two conditions in particular may enable others to recognize who we really are most readily: First, when they are able to “read” a trait from outward characteristics and, second, when a trait has a clear positive or negative valence (intelligence and creativity are obviously desirable, for instance; dishonesty and egocentricity are not). Our assessments of ourselves most closely match assessments by others when it comes to more neutral characteristics.

The characteristics generally most readable by others are those that strongly affect our behavior. For example, people who are naturally sociable typically like to talk and seek out company; insecurity often manifests in behaviors such as hand-wringing or averting one’s gaze. In contrast, brooding is generally internal, unspooling within the confines of one’s mind.

We are frequently blind to the effect we have on others because we simply do not see our own facial expressions, gestures and body language. I am hardly aware that my blinking eyes indicate stress or that the slump in my posture betrays how heavily something weighs on me. Because it is so difficult to observe ourselves, we must rely on the observations of others, especially those who know us well. It is hard to know who we are unless others let us know how we affect them.

4. Gaining some distance can help you know yourself better

Keeping a diary, pausing for self-reflection and having probing conversations with others have a long tradition, but whether these methods enable us to know ourselves is hard to tell. In fact, sometimes doing the opposite — such as letting go — is more helpful because it provides some distance. In 2013 Erika Carlson, now at the University of Toronto, reviewed the literature on whether and how mindfulness meditation improves one’s self-knowledge. It helps, she noted, by overcoming two big hurdles: distorted thinking and ego protection. The practice of mindfulness teaches us to allow our thoughts to simply drift by and to identify with them as little as possible. Thoughts, after all, are “only thoughts” and not the absolute truth. Frequently, stepping out of oneself in this way and simply observing what the mind does fosters clarity.

Gaining insight into our unconscious motives can enhance emotional well-being. Oliver C. Schultheiss of Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany has shown that our sense of well-being tends to grow as our conscious goals and unconscious motives become more aligned or congruent. For example, we should not slave away at a career that gives us money and power if these goals are of little importance to us. But how do we achieve such harmony? By imagining, for example. Try to imagine, as vividly and in as much detail as possible, how things would be if your most fervent wish came true. Would it really make you happier? Often we succumb to the temptation to aim excessively high without taking into account all of the steps and effort necessary to achieve ambitious goals.

5. We too often think we are better at something than we are

Are you familiar with the Dunning Kruger effect? It holds that the more incompetent people are, the less they are aware of their incompetence. The effect is named after David Dunning of the University of Michigan and Justin Kruger of New York University.

Dunning and Kruger gave their test subjects a series of cognitive tasks and asked them to estimate how well they did. At best, 25 percent of the participants viewed their performance more or less realistically; only some people underestimated themselves. The quarter of subjects who scored worst on the tests really missed the mark, wildly exaggerating their cognitive abilities. Is it possible that boasting and failing are two sides of the same coin?

As the researchers emphasize, their work highlights a general feature of self-perception: each of us tends to overlook our cognitive deficiencies. According to psychologist Adrian Furnham of University College London, the statistical correlation between perceived and actual IQ is, on average, only 0.16 — a pretty poor showing, to put it mildly. By comparison, the correlation between height and sex is about 0.7.

So why is the chasm between would-be and actual performance so gaping? Don’t we all have an interest in assessing ourselves realistically? It surely would spare us a great deal of wasted effort and perhaps a few embarrassments. The answer, it seems, is that a moderate inflation of self-esteem has certain benefits. According to a review by psychologists Shelley Taylor of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Jonathon Brown of the University of Washington, rose-colored glasses tend to increase our sense of well-being and our performance. People afflicted by depression, on the other hand, are inclined to be brutally realistic in their self-assessments. An embellished self-image seems to help us weather the ups and downs of daily life.

6. People who tear themselves down experience setbacks more frequently

Although most of our contemporaries harbor excessively positive views of their honesty or intelligence, some people suffer from the opposite distortion: they belittle themselves and their efforts. Experiencing contempt and belittlement in childhood, often associated with violence and abuse, can trigger this kind of negativity — which, in turn, can limit what people can accomplish, leading to distrust, despair and even suicidal thoughts.

It might seem logical to think that people with a negative self-image would be just the ones who would want to overcompensate. Yet as psychologists working with William Swann of the University of Texas at Austin discovered, many individuals racked with self-doubt seek confirmation of their distorted self-perception. Swann described this phenomenon in a study on contentment in marriage. He asked couples about their own strengths and weaknesses, the ways they felt supported and valued by their partner, and how content they were in the marriage. As expected, those who had a more positive attitude toward themselves found greater satisfaction in their relationship the more they received praise and recognition from their other half. But those who habitually picked at themselves felt safer in their marriage when their partner reflected their negative image back to them. They did not ask for respect or appreciation. On the contrary, they wanted to hear exactly their own view of themselves: “You’re incompetent.”

Swann based his theory of self-verification on these findings. The theory holds that we want others to see us the way we see ourselves. In some cases, people actually provoke others to respond negatively to them so as to prove how worthless they are. This behavior is not necessarily masochism. It is symptomatic of the desire for coherence: if others respond to us in a way that confirms our self-image, then the world is as it should be.

Likewise, people who consider themselves failures will go out of their way not to succeed, contributing actively to their own undoing. They will miss meetings, habitually neglect doing assigned work and get into hot water with the boss. Swann’s approach contradicts Dunning and Kruger’s theory of overestimation. But both camps are probably right: hyperinflated egos are certainly common, but negative self-images are not uncommon.

7. You deceive yourself without realizing it

According to one influential theory, our tendency for self-deception stems from our desire to impress others. To appear convincing, we ourselves must be convinced of our capabilities and truthfulness. Supporting this theory is the observation that successful manipulators are often quite full of themselves. Good salespeople, for example, exude an enthusiasm that is contagious; conversely, those who doubt themselves generally are not good at sweet talking. Lab research is supportive as well. In one study, participants were offered money if, in an interview, they could convincingly claim to have aced an IQ test. The more effort the candidates put into their performance, the more they themselves came to believe that they had a high IQ, even though their actual scores were more or less average.

Our self-deceptions have been shown to be quite changeable. Often we adapt them flexibly to new situations. This adaptability was demonstrated by Steven A. Sloman of Brown University and his colleagues. Their subjects were asked to move a cursor to a dot on a computer screen as quickly as possible. If the participants were told that above-average skill in this task reflected high intelligence, they immediately concentrated on the task and did better. They did not actually seem to think that they had exerted more effort—which the researchers interpret as evidence of a successful self-deception. On the other hand, if the test subjects were convinced that only dimwits performed well on such stupid tasks, their performance tanked precipitously.

But is self-deception even possible? Can we know something about ourselves on some level without being conscious of it? Absolutely! The experimental evidence involves the following research design: Subjects are played audiotapes of human voices, including their own, and are asked to signal whether they hear themselves. The recognition rate fluctuates depending on the clarity of the audiotapes and the loudness of the background noise. If brain waves are measured at the same time, particular signals in the reading indicate with certainty whether the participants heard their own voice.

Most people are somewhat embarrassed to hear their own voice. In a classic study, Ruben Gur of the University of Pennsylvania and Harold Sackeim of Columbia University made use of this reticence, comparing the statements of test subjects with their brain activity. Lo and behold, the activity frequently signaled, “That’s me!” without subjects’ having overtly identified a voice as their own. Moreover, if the investigators threatened the participants’ self-image — say, by telling them that they had scored miserably on another (irrelevant) test — they were even less apt to recognize their voice. Either way, their brain waves told the real story.

In a more recent study, researchers evaluated performances on a practice test meant to help students assess their own knowledge so that they could fill in gaps. Here subjects were asked to complete as many tasks as possible within a set time limit. Given that the purpose of the practice test was to provide students with information they needed, it made little sense for them to cheat; on the contrary, artificially pumped-up scores could have led them to let their studies slide. Those who tried to improve their scores by using time beyond the allotted completion period would just be hurting themselves.

But many of the volunteers did precisely that. Unconsciously, they simply wanted to look good. Thus, the cheaters explained their running over time by claiming to have been distracted and wanting to make up for lost seconds. Or they said that their fudged outcomes were closer to their “true potential.” Such explanations, according to the researchers, confuse cause and effect, with people incorrectly thinking, “Intelligent people usually do better on tests. So if I manipulate my test score by simply taking a little more time than allowed, I’m one of the smart ones, too.” Conversely, people performed less diligently if they were told that doing well indicated a higher risk for developing schizophrenia. Researchers call this phenomenon diagnostic self-deception.

8. The “true self” is good for you

Most people believe that they have a solid essential core, a true self. Who they truly are is evinced primarily in their moral values and is relatively stable; other preferences may change, but the true self remains the same. Rebecca Schlegel and Joshua Hicks, both at Texas A&M University, and their colleagues have examined how people’s view of their true self affects their satisfaction with themselves. The researchers asked test subjects to keep a diary about their everyday life. The participants turned out to feel most alienated from themselves when they had done something morally questionable: they felt especially unsure of who they actually were when they had been dishonest or selfish. Experiments have also confirmed an association between the self and morality. When test subjects are reminded of earlier wrongdoing, their surety about themselves takes a hit.

George Newman and Joshua Knobe, both at Yale University, have found that people typically think humans harbor a true self that is virtuous. They presented subjects with case studies of dishonest people, racists, and the like. Participants generally attributed the behavior in the case studies to environmental factors such as a difficult childhood—the real essence of these people must surely have been different. This work shows our tendency to think that, in their heart of hearts, people pull for what is moral and good.

Another study by Newman and Knobe involved “Mark,” a devout Christian who was nonetheless attracted to other men. The researchers sought to understand how the participants viewed Mark’s dilemma. For conservative test subjects, Mark’s “true self” was not gay; they recommended that he resist such temptations. Those with a more liberal outlook thought he should come out of the closet. Yet if Mark was presented as a secular humanist who thought being homosexual was fine but had negative feelings when thinking about same-sex couples, the conservatives quickly identified this reluctance as evidence of Mark’s true self; liberals viewed it as evidence of a lack of insight or sophistication. In other words, what we claim to be the core of another person’s personality is in fact rooted in the values that we ourselves hold most dear. The “true self” turns out to be a moral yardstick.

The belief that the true self is moral probably explains why people connect personal improvements more than personal deficiencies to their “true self.” Apparently we do so actively to enhance appraisals of ourselves. Anne E. Wilson of Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario and Michael Ross of the University of Waterloo in Ontario have demonstrated in several studies that we tend to ascribe more negative traits to the person we were in the past—which makes us look better in the here and now. According to Wilson and Ross, the further back people go, the more negative their characterization becomes. Although improvement and change are part of the normal maturation process, it feels good to believe that over time, one has become “who one really is.”

Assuming that we have a solid core identity reduces the complexity of a world that is constantly in flux. The people around us play many different roles, acting inconsistently and at the same time continuing to develop. It is reassuring to think that our friends Tom and Sarah will be precisely the same tomorrow as they are today and that they are basically good people—regardless of whether that perception is correct.

Is life without belief in a true self even imaginable? Researchers have examined this question by comparing different cultures. The belief in a true self is widespread in most parts of the world. One exception is Buddhism, which preaches the nonexistence of a stable self. Prospective Buddhist monks are taught to see through the illusionary character of the ego—it is always in flux and completely malleable.

Nina Strohminger of the University of Pennsylvania and her colleagues wanted to know how this perspective affects the fear of death of those who hold it. They gave a series of questionnaires and scenarios to about 200 lay Tibetans and 60 Buddhist monks. They compared the results with those of Christians and nonreligious people in the U.S., as well as with those of Hindus (who, much like Christians, believe that a core of the soul, or atman, gives human beings their identity). The common image of Buddhists is that they are deeply relaxed, completely “selfless” people. Yet the less that the Tibetan monks believed in a stable inner essence, the more likely they were to fear death. In addition, they were significantly more selfish in a hypothetical scenario in which forgoing a particular medication could prolong the life of another person. Nearly three out of four monks decided against that fictitious option, far more than the Americans or Hindus. Self-serving, fearful Buddhists? In another paper, Strohminger and her colleagues called the idea of the true self a “hopeful phantasm,” albeit a possibly useful one. It is, in any case, one that is hard to shake.

9. Insecure people tend to behave more morally

Insecurity is generally thought of as a drawback, but it is not entirely bad. People who feel insecure about whether they have some positive trait tend to try to prove that they do have it. Those who are unsure of their generosity, for example, are more likely to donate money to a good cause. This behavior can be elicited experimentally by giving subjects negative feedback—for instance, “According to our tests, you are less helpful and cooperative than average.” People dislike hearing such judgments and end up feeding the donation box.

Drazen Prelec, a psychologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explains such findings with his theory of self-signaling: what a particular action says about me is often more important than the action’s actual objective. More than a few people have stuck with a diet because they did not want to appear weak-willed. Conversely, it has been empirically established that those who are sure that they are generous, intelligent or sociable make less effort to prove it. Too much self-assurance makes people complacent and increases the chasm between the self that they imagine and the self that is real. Therefore, those who think they know themselves well are particularly apt to know themselves less well than they think.

10. If you think of yourself as flexible, you will do much better

People’s own theories about who they are influence how they behave. One’s self-image can therefore easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Carol Dweck of Stanford University has spent much time researching such effects. Her takeaway: if we view a characteristic as mutable, we are inclined to work on it more. On the other hand, if we view a trait such as IQ or willpower as largely unchangeable and inherent, we will do little to improve it.

In Dweck’s studies of students, men and women, parents and teachers, she gleaned a basic principle: people with a rigid sense of self take failure badly. They see it as evidence of their limitations and fear it; fear of failure, meanwhile, can itself cause failure. In contrast, those who understand that a particular talent can be developed accept setbacks as an invitation to do better next time. Dweck thus recommends an attitude aimed at personal growth. When in doubt, we should assume that we have something more to learn and that we can improve and develop.

But even people who have a rigid sense of self are not fixed in all aspects of their personality. According to psychologist Andreas Steimer of the University of Heidelberg in Germany, even when people describe their strengths as completely stable, they tend to believe that they will outgrow their weaknesses sooner or later. If we try to imagine how our personality will look in several years, we lean toward views such as: “Level-headedness and clear focus will still be part and parcel of who I am, and I’ll probably have fewer self-doubts.”

Overall, we tend to view our character as more static than it is, presumably because this assessment offers security and direction. We want to recognize our particular traits and preferences so that we can act accordingly. In the final analysis, the image that we create of ourselves is a kind of safe haven in an ever-changing world.

And the moral of the story? According to researchers, self-knowledge is even more difficult to attain than has been thought. Contemporary psychology has fundamentally questioned the notion that we can know ourselves objectively and with finality. It has made it clear that the self is not a “thing” but rather a process of continual adaptation to changing circumstances. And the fact that we so often see ourselves as more competent, moral and stable than we actually are serves our ability to adapt.

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

First, marijuana — are magic mushrooms next?

Shutterstock/Getty

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News.

In Oregon and Denver, where marijuana is legal for recreational use, activists are now pushing toward a psychedelic frontier: “magic mushrooms.”

Groups in both states are sponsoring ballot measures that would eliminate criminal penalties for possession of the mushrooms whose active ingredient, psilocybin, can cause hallucinations, euphoria and changes in perception. They point to research showing that psilocybin might be helpful for people suffering from depression or anxiety.

“We don’t want individuals to lose their freedom over something that’s natural and has health benefits,” said Kevin Matthews, the campaign director of Denver for Psilocybin, the group working to decriminalize magic mushrooms in Colorado’s capital.

The recent failure of a nationally publicized campaign to decriminalize hallucinogenic mushrooms in California may not portend well for the psilocybin advocates in Oregon and Denver — though their initiatives are more limited than California’s.

The proposal in the Golden State would have decriminalized sales and transportation of magic mushrooms, not just possession. The proposed Denver measure would apply only to that city, while in Oregon mushroom use would be allowed only with the approval of a physician and under the supervision of a registered therapist.

None of the proposed initiatives envisions fully legalizing psilocybin mushrooms, which would allow the government to regulate and tax sales in a similar fashion to medical and recreational marijuana.

In Oregon, advocates face a steep climb to qualify their measure for the ballot, because such statewide initiatives typically require hiring paid signature gatherers, said William Lunch, a political analyst for Oregon Public Broadcasting and a former political science professor at Oregon State University.

Still, familiarity with recreational marijuana may have “softened up” voters and opponents of drug decriminalization, he said. Oregon legalized marijuana for recreational use in 2015, Colorado in 2012.

The Oregon and Denver activists, echoing Lunch, say they hope voters who already accepted pot would now feel comfortable decriminalizing personal use of magic mushrooms as well.

Taking mushrooms can lead to nausea, panic attacks and, rarely, paranoia and psychosis. But they generally are considered safer and less addictive than other illegal street drugs.

Even so, Paul Hutson, professor of pharmacy at the University of Wisconsin who has conducted psilocybin research, says he is wary of the drive for decriminalization. Psilocybin isn’t safe for some people — particularly those with paranoia or psychosis, he said.

“I reject the idea that this is a natural progression from medical marijuana,” Hutson said, noting that the safety of pot is much better established. Mushrooms, he added, “are very, very potent medicines that are affecting your mind. In the proper setting, they’re safe, but in an uncontrolled fashion, I have grave concerns.”

Even psilocybin advocates share Hutson’s concerns. “It is such a powerful compound. People should take it very seriously when experimenting,” Matthews said.

These efforts to legitimize hallucinogenic mushrooms come at a time of renewed interest in the potential mental health benefits of psychedelics, including mushrooms, LSD and MDMA (known as ecstasy). Two small studies published in 2016 by researchers from Johns Hopkins University and New York University found that a single large dose of psilocybin, combined with psychotherapy, helped relieve depression and anxiety in cancer patients.

A British company backed by Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel plans clinical studies in eight European countries to test the use of psilocybin for depression. Other research has examined the effectiveness of psilocybin in treating alcohol and tobacco addiction.

In California, the campaign to decriminalize psilocybin was always a long shot — even though the famously liberal state legalized possession of recreational marijuana in November 2016 and sales starting this year.

California ballot measures typically require nearly 366,000 signatures to qualify, and supporters usually have to spend between $1 million and $2 million to pay signature gatherers. A Monterey County couple leading the decriminalization campaign managed to collect more than 90,000 signatures for their proposal with the help of volunteers, but they halted their efforts late last month.

The initiative would have exempted Californians 21 and over from criminal penalties for possessing, selling, transporting or cultivating psilocybin mushrooms.

Possessing them is generally a misdemeanor under California law, but selling them is a felony. State statistics on psilocybin offenses are scarce, but few people are jailed for such crimes, according to an analysis by the California attorney general’s office.

“It’s not a reckless community,” said Kitty Merchant of Marina, Calif., who spearheaded the California psilocybin campaign alongside her husband, Kevin Saunders. “It’s experimentation with your mind and your thoughts. There’s a safeness to it. And there’s an intelligence to it.”

Merchant said she and Saunders, both medical marijuana advocates, spent about $20,000 of their own money on the campaign.

In Denver, Matthews and his pro-psilocybin colleagues want voters to pass a city ordinance eliminating criminal penalties for possessing, using or growing magic mushrooms. City officials have cleared the measure for signature gathering. Supporters need 5,000 signatures to get it on the ballot in November. Matthews said he has already lined up dozens of volunteer signature gatherers.

He said he has used mushrooms to help alleviate depression and other mental health problems. A big part of the decriminalization campaign, he said, is promoting responsible use.

Denver, a progressive city in a state that was the first to legalize recreational marijuana, “is a good testing place for this initiative nationwide,” Matthews said. Just getting it on the ballot, whether or not it passes, would be “a huge victory,” he added.

In Oregon, activists are proposing a measure for the 2020 ballot that would decriminalize psilocybin statewide for adults 21 and over who get approval from their doctors and agree to participate in a “psilocybin service.” The service would include a preparatory meeting with a therapist, one session of supervised mushroom use and a follow-up visit. Patients would be under the care of state-certified “Psilocybin Service Facilitators.”

Tom Eckert, a Portland, Ore.-based therapist who leads the psilocybin decriminalization campaign with his wife, Sheri, said the proposed limitations on psilocybin use are important.

“Psilocybin is generally safe, but it puts you in a vulnerable state of mind,” he said. “If you do it in the wrong setting, things can go sideways.”

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

California’s new solar rooftop mandate could be better

AP

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

More California rooftops will soon sport solar panels, partly due to a new state mandate requiring them for all new houses and low-rise residential buildings by 2020.

This rule immediately sparked lively debates. Even experts who generally advocate for solar energy expressed skepticism that it was actually a good idea.

As an environmental economist who studies the design of environmental policies, I believe that doing something about climate change is important, but I don’t consider this new solar mandate to be the best way to achieve that goal. I’m also concerned that it could exacerbate problems with California’s housing market.

#California to require rooftop #solar for new homes. #Renewables #EnergyIsChanging https://t.co/Xmjeg0SUpB pic.twitter.com/fQAAXsEjvf

— Jeffrey Clark (@JeffClarkTweets) May 15, 2018

More than two sides

You might expect the debate over this policy, which became official when the California Energy Commission unanimously voted in favor of it on May 8, to pit two well-defined camps against each other.

Environmentalists who prize fighting climate change might love it due to a presumption that increasing the share of power California derives from solar panels will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by cutting demand for natural gas and coal.

On the other hand, those who question whether the costs of addressing climate change are worth it might hate the solar mandate, since they either see no benefits or think the benefits aren’t worth the costs.

But there are more than two sides.

Environmental economics 101

Many renewable energy experts, including economists like me, want governments to do something to address climate change but question the mandate.

University of California, Berkeley economist Severin Borenstein summed up this take in his open letter to the California Energy Commission opposing the rule. University of California, Davis economist James Bushnell also opposes the mandate for similar reasons.

Above all, what we economists call “command-and-control policies” like this mandate – inflexible requirements that apply to everyone – often don’t make sense. For example, going solar is less economical in some cases. Even in sunny California, builders can construct housing in shady areas, and not all homeowners use enough electricity for the investment to pay off before they move away.

The mandate does have some exemptions tied to shade and available roof space, but there could property owners subjected to the requirement to own or lease solar panels who might consider it unreasonable.

We tend to think that “market-based policies” would work better. By relying on incentives instead of requirements, people get to decide for themselves what to do.

Good examples of these policies include a tax on pollution, like British Columbia’s carbon tax, or a cap-and-trade market, like the European Union’s Emissions Trading System. Instead of restricting the right to pollute, these approaches make people and businesses pay to pollute, either through taxation or by buying mandatory permits.

The flexibility of market-based policies can make meeting pollution reduction goals cost-effective. When people – or businesses – have to factor the costs of pollution into their decision-making, they have a financial incentive to pollute less and will find ways to do so. By reducing pollution as cheaply as possible, more money is left over to spend on other pressing needs like housing, health care and education.

This advantage is not merely theoretical. By many accounts, market-based policies have successfully worked according to theory, including the U.S. sulfur dioxide trading program and the EU’s carbon trading program.

California itself has a cap-and-trade market. I believe that expanding and improving it would cut carbon emissions more cost-effectively than the solar mandate would.

Many economists also fear that the mandate will worsen California’s housing unaffordability. This crisis has many causes, such as restrictive zoning regulations that curtail construction. But the solar-panel requirement, which could increase the cost of a new home by more than $10,000, probably won’t help, even though supporters of the policy argue that the solar panels will pay for themselves in terms of lower monthly electricity costs.

The solar mandate’s fans

The solar mandate’s defenders, including Gov. Jerry Brown and Sierra Club leader Rachel Golden, make several arguments – two of which I find credible.

The first is what I’d call the “Panglossian” argument, after the character in “Candide,” Voltaire’s 18th-century classic satire. In what Voltaire would call “the best of all possible worlds,” taxing carbon would make perfect sense.

But this is a world riddled with political obstacles that make enacting almost any climate policy next to impossible. If a big American state can enact an imperfect law like this mandate that might do some good, then it should go for it.

The other argument I find reasonable is that by drumming up more demand, the solar mandate will expand the solar panel market – thereby driving solar costs down, perhaps more quickly than a carbon tax would. There’s some evidence supporting the theory that these mandates can spur innovation in renewable electricity technologies.

Heard that California is mandating solar panels on all new homes? Not sure what to think about it? Come with me & wallow in ambivalence! https://t.co/1TtDxEruK0

— David Roberts (@drvox) May 15, 2018

If the mandate works out, it might address two issues at once: shrinking California’s carbon footprint and bolstering technological progress in the solar industry.

To be sure, the cost of residential solar panels has plummeted in recent years, although generating solar energy through rooftop panels remains less cost-effective than power from utility-scale solar farms.

A practical policy

After mulling all the various arguments made by these different camps, I don’t think that whether California’s rooftop solar mandate is the perfect policy for the climate or the state’s homebuyers is the question.

The answer to that question is a resounding no – but that is beside the point because no policy is perfect. The key question is whether this policy – given its imperfections and given the difficulty in passing more cost-effective policies – is a winner overall. That question is harder to answer.

Ultimately, I believe the mandate will yield some environmental benefits, though they could be more cost-effectively achieved through other means.

Garth Heutel, Associate Professor of Economics, Georgia State University

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

As social media giants push bullying prevention, experts wonder if it will be enough

Getty/Shutterstock

Soon after cyberspace came into existence, cyber-cafés, cybersex, and — regrettably — cyber-bullying all followed. For young people nowadays, many of whom experience much of their social lives vis-a-vis their phones, cyberbullying is as common or even more common than "normal" IRL bullying. Digital harassment has changed the teenage experience, and has even been cited as one reason why some have taken their own lives.

Yet the internet is no longer the wild west it once was, and Silicon Valley tech companies seem to be taking cyber-bullying more seriously — or at least paying lip service to the idea. In the past month, both Twitter and Instagram, popular youth hangouts, rolled out new plans to combat bullying on their platforms. And while experts say these two companies' policy actions are commendable, they do not seem to have the one-size-fits-all solution to remove abuse from our digital lives.

Last week Twitter unveiled a new, proactive strategy to fight abusive trolls. While Twitter’s policy already prohibits harassment, and has the authority to suspend or block certain Twitter accounts, the company's CEO Jack Dorsey announced the company will be using technology to identify behavioral signals of harassers and then limit the visibility of harmful tweets.

“We want to take the burden of the work off the people receiving the abuse or the harassment,” Dorsey told reporters, via Reuters. He said previous efforts to combat abuse “felt like Whac-A-Mole.”

According to the Reuters report, the new approach decreased abuse reports originating from search results by 4 percent. It decreased abuse reports that stemmed from conversations—such as replies to tweets—by 8 percent.

Twitter is following suit of Instagram, the Facebook-owned company that announced in early May a new initiative to protect its users from cyberbullying. While Instagram previously filtered offensive comments, particularly those aimed at “at-risk groups,” the new filter hides comments that attack a person’s appearance, character, well-being or health.

“The bullying filter is on for our global community and can be disabled in the Comment Controls center in the app,” Kevin Systrom, Co-Founder & CEO wrote in a blog post. “The new filter will also alert us to repeated problems so we can take action.”

The notion of hiding harassment from users is commendable. Anyone who has been a victim of cyberbullying knows the stress and the emotional impact. Yet some experts told Salon they are not convinced that these two tech giants' plans are more than a small step in the right direction.

Sherryll Kraizer, the director of the Coalition for Children, said she gives “high praise” to the tech companies regarding their latest initiatives.

“I think is particularly hopeful [how] they are approaching it by using their own technology,” Kraizer tells Salon. “Having said that, the fact that Twitter only reports 4 to 8 percent decline in abuse reports that is not the best start.”

Kraizer said they should continue to use the technology they have to further their efforts.

Sameer Hinduja, co-director of the Cyberbullying Research Center and professor of criminology at Florida Atlantic University, tells Salon it has always been a “learn as you go” for tech companies in the fight to combat cyber abuse—and these latest updates will likely be similar.

“On some level, we have had to be gracious with them as they figure out how to deal with never-before-seen problems arising at the intersection of humanity and technology,” Hinduja tells Salon. “Their use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to programmatically predict what may be abusive or toxic will similarly require our grace as they work out the kinks and figure out how to deal with contextual clues, sarcasm, constantly changing slang, varying cross-cultural definitions and perceptions of free speech, implicit bias and hate, and similar complex issues.”

Hinduja says while nobody should expect their systems to be perfect, it is indeed positive that the field is “rapidly developing.”

Christine McComas, an advocate in preventing cyberbullying abuse—and mother whose daughter Grace McComas took her own life after being cyber-bullied—tells Salon she feels encouraged by the policy changes.

“Do I think it will work? I'm not sure, but I am hopeful. It's a start, which is better than nothing,” she tells Salon. "My hope is that 30 years from now, much like drunk driving, we will see cyberabuse for the damaging behavior that it is, and that we will make the positive social changes necessary to curb it,” McComas added.

Notably, Twitter and Instagram's actions do not necessarily address when the abuser is not a stranger — which is typically the case with younger victims.

“By and large, when it comes to adolescent populations, the aggressor is primarily someone the target knows — and usually from school.” Hinduja says.

Pope’s latest remarks get nods — but he’s no LGBTQ ally

AP/Alessandra Tarantino

Following Pope Francis’s meeting last week with 34 Chilean bishops — many of whom have been accused or suspected of covering up instances of clerical sexual abuse in their country and all of whom have offered to resign — a survivor who met with Francis recently has shared details of his encounter with the pontiff.

"He told me, 'Juan Carlos, the fact that you’re gay doesn’t matter. God made you like that, and he loves you like that, and I don’t care,'" Juan Carlos Cruz told Spanish newspaper El Pais, recalling his nearly three-hour conversation with the pontiff. He said the Pope made the comments when they met for a private discussion last month to discuss the sexual abuse and cover-up scandal involving clergy members in Cruz's native Chile.

Cruz, who was sexually assaulted as a child by the Rev. Fernando Karadima, Chile's disgraced pedophile priest who was found guilty of abusing young boys in Santiago in the 1970s and 1980s in a 2011 Vatican investigation, told the paper that his sexual orientation came up during the conversation. Specifically, Cruz has been targeted for being gay, and experienced painful personal attacks after speaking out about his abuse.

"They had told [Francis] that I was practically a pervert. I explained that I’m not the reincarnation of San Luis Gonzaga, but I am not a bad person, I try to not harm anyone," Cruz told El Pais.

A representative at the Vatican declined to confirm or deny the remarks, telling The Los Angeles Times, "We don’t normally comment on the pope’s private conversations."

Official church teaching calls for acceptance and respect of lesbian, bisexual and gay people, but considers homosexual activity "intrinsically disordered." Francis, though, has attempted to make the church more welcoming to the community, most notably with his 2013 remark, "If someone is gay and searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?" Later that year, he suggested in an interview that God does not "reject and condemn" gay people.

While the Pope's recent comments have been praised by some in the LGBTQ community as another indication of his vision of inclusion in the Catholic Church, some have sought to downplay the significance of the remarks as merely being in line with his pastoral practice and believe he has a lot of catching up to do on transgender issues.

"While it's a good comment, it really doesn't change the church's teachings," Francis DeBernardo, executive director of New Ways Ministry, an LGBTQ-affirming Catholic advocacy organization, told Salon. "What it does show is that he is much more pastorally inclined about LGBT issues than his predecessors have been, meaning that he's willing to dialogue and listen and learn from LGBT people."

He also said he doesn't think the Pope "has a good handle of the science of transgender issues and gender identity."

"He has this blind spot about what transgender reality really is," DeBernardo added. "He seems to have a problem with with this belief, that he has, that people are educating children to believe that they have a choice about their gender, and that's that's just not true. That's not that's not how transgender identity works. Transgender people report that they discovered their their true gender identity, not that they have chosen their true gender identity."

Marianne Duddy-Burke, executive director of Dignity USA, an organization that focuses on LGBTQ rights within the Catholic Church, echoed DeBernardo.

She told Salon that while the Pope's reported comments "could have important implications" for the LGBTQ community, but cautioned against interpreting the outreach as a change in church teaching. "The question is going to be about whether these comments are allowed to stand, or if there's going to be a lot of pushback from the very dogmatically-oriented members of the Curia or the right-wing Catholic organizations that tend to have a lot of influence with the Vatican," she said.

Duddy-Burke pointed out that "the current church teachings and practices are very dangerous to all kinds of queer people and to our families," explaining that they're being used to help wage campaigns "to restrict access to healthcare for transgender people and gay people."

"Most critically impacted by the health care issues is the transgender community, with many Catholic hospitals refusing to provide any kind of gender confirmation services," she said. "And now [Catholic hospitals] are not even being required to provide referrals to places that will serve trans folk, and that's incredibly dangerous for the mental and physical health of transgender people in our own country."

Pope Francis has previously come under scrutiny from the LGBTQ community, most recently after he condemned technologies that are making it easier for people to change their genders, saying this "utopia of the neutral" threatens the creation of new life, according to the Associated Press. Such advances in "biomedical technology," the pontiff said, "risk dismantling the source of energy that fuels the alliance between men and women and renders them fertile."

And in 2015, Francis compared transgender people to nuclear weapons, saying both do not "recognize the order of creation."

"Let’s think of the nuclear arms, of the possibility to annihilate in a few instants a very high number of human beings," he said in an in an interview with Italian journalists Andrea Tornielli and Giacomo Galeazzi. "Let’s think also of genetic manipulation, of the manipulation of life, or of the gender theory, that does not recognize the order of creation."

"With this attitude, man commits a new sin, that against God the Creator," he added. "The true custody of creation does not have anything to do with the ideologies that consider man like an accident, like a problem to eliminate."

And the Catholic Church only recently revised the teaching that insisted that sexual orientation was not something people choose, but that it was designed by God.

The first edition of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the summary of Catholic teaching published by St. John Paul II in 1992, said gay individuals "do not choose their homosexual condition; for most of them it is a trial."

The updated edition was amended to remove the reference to homosexuality not being a choice. The revised version says, "This inclination, which is objectively disordered, constitutes for most of them a trial."

While the Catholic Church has become more progressive with Pope Francis leading its direction, it's clear that it has a long way to go to holding its arms wide open to the to the LGBTQ community.

The “cheese of kings and popes” is at the core of a mac and cheese-based recipe for salvation

Getty/burwellphotography

I used to dream of mac and cheese. There were actual dreams, where I’d wake up hungry with a plate of noodles soaked in cheesy sauce dancing in my half-consciousness. And there were daydreams, where I’d plot the perfect roux that would allow that cheese to cling beautifully to that pasta.

When I was in the thick of my anorexia, I also became obsessed with muffins: berry muffins with lemon curd, apple muffins with streusel topping, sour cream muffins with dark chocolate chips. I baked them for my roommates. I brought them to class. But I would never, ever let a crumb touch my lips. I was too afraid of that sugar/flour/butter showing up on my thighs and arms and stomach. I was too afraid of gaining the weight that I had worked so painstakingly to lose the year before.

Muffins were just the start. At Picholine, the restaurant where I worked as a hostess on nights and weekends during my freshman year of college, we served a Daube of Short Rib, a fancy way to say short ribs braised in red wine until nearly melting. I had let myself try a bite of the dish that was passed around during our pre-shift meeting, a scant mouthful, and it sent a meaty, garlicky jolt straight to my brain. Who knew short ribs could taste like that!

And don’t even get me started with the cheese cart: the shards of butterscotchy Gouda, the fudgy Stilton, and the nearly liquid rounds that required a spoon for serving. My palate was developing; my mind was expanding; my body was shrinking; and my heart hurt from a bitter mix of obsession, fear, and self-loathing.

Sophomore year, I made it to my college Student Health Services and then to a non-college therapist and nutritionist. The code on my insurance form read “anorexia-nervosa.” I thought that sounded like bullshit. Sure, I was terrified of food, ruled by it, but I was also in love with the alchemy of cooking, the way my college house smelled when I tried my hand at those short ribs, my few found minutes with the chef’s massive cookbook collection. I began dreaming of opening my own restaurant after school.

It turns out an intense preoccupation with food is a part of many eating disorders. When it comes to restriction, especially, it’s a perverse sort of torture. In my sick brain, it sounded something like this: I can’t gain weight by pouring over recipes, cooking and baking for my classmates, and watching marathons of Top Chef (the first season aired my freshman spring in 2006). It makes a sick sort of sense. We are fueled by our demons.

I especially delighted in cooking things that felt too decadent to possibly eat: I braised short ribs in red wine and rosemary, and then in ginger, lemongrass, and rice wine. I layered phyllo dough and pistachios into baklava. I had this fantasy that I would reach some imaginary place of perfect thinness, and that the thinness would lead to joy and peace, and then I would daintily eat the dishes I spent all day thinking about and cooking and stalking.

Chief among them was a grown-up mac and cheese, made in my imagination with shells, or corkscrews, and an ooey cheese sauce with just a little bit of funk from a brawny blue. It would be blanketed with breadcrumbs turned golden and crunchy in the oven. Carbs. Cheese. Butter. Perfection.

Sometime in the middle of college, my anorexia morphed into an equally miserable binge and restrict cycle. I think my brain and body couldn’t take the starving anymore. They rebelled without my consent. I began scarfing massive quantities of whatever food I could get my hands on. I’d wake up the next morning sick with regret, mentally tallying the caloric damage wrought, vowing to diet harder, stricter, better. Which I managed for a few days, weeks, or even months, before finding myself shoveling things straight from box and bag to mouth in a fugue state. Rinse and repeat.

My housemates missed the muffins — I devoured the whole bowl of batter before they made it anywhere near the oven. I started to stay away from the kitchen. It felt like the scene of the crime. Who knew what would happen there.

Over the last six years, I've slowly recovered from these multiple incarnations of eating disorders. I've (mostly) made peace with food, which I often think of untangling the love for all things culinary that led me to a career in restaurants from the destructive obsession that led to so much pain.

For the first year of recovery, I was uneasy about cooking. Spending too much time in kitchens felt like tempting fate. I ate a lot of simple meals that didn’t require much fuss: oatmeal with lots of cinnamon for breakfast, salads from Westside Market for lunch, and delivery pho for dinner. These things felt safe.

But cooking is a part of me, and I wanted my new, tenuous peace treaty with food to extend to my kitchen, then in a studio on West 95th Street. My cookbooks were stacked up, as if smiling kindly at me. I had a good cast iron skillet, and a hand-me-down casserole dish, and a hodge-podge of supplies from Housing Works. I had a new job at Fairway, which meant a discount on groceries and a whole lineup of free olive oils and vinegars on my counter.

Somehow, it felt less daunting to cook for friends than to cook for myself. I’ve always loved to host. I invited four people over, because I had five chairs. I sautéed hearty greens with a pile of shallots. I drizzled my best olive oil over sweet tomatoes. And I made that mac and cheese, the one that lived only in my culinary fantasies. I chose a sharp cheddar, and nutty Gruyere, and Roquefort. Roquefort was the favorite of Emperor Charlemagne. It’s sometimes called the “cheese of kings and popes,” and its regal nature made it feel appropriate, a cheeky contrast to the comfort food banality of mac and cheese.

A miracle happened: the dinner was a success. Not just because my friends had fun, so much fun one ended up falling asleep at the foot of my bed, like a cat, but because I ate the way I imagine a normal person eats. I had a plate of food—not a miniscule plate, not a ginormous plate, just a plate. I enjoyed it thoroughly. I didn’t binge after. I didn’t even hate myself for the pasta and cheese that graced my lips.

But I did think that the recipe needed a little more butter mixed into the breadcrumbs, to make them crispier, so I tweaked it and made it again. And again.

I have a significant Seamless habit, but my kitchen is one of my favorite places to spend time today. I don’t think obsessively about what I’m going to make for dinner. When I do think about it, it makes me smile.

Roquefort Mac and Cheese

Serves: 6 – 8

Ingredients

Kosher salt

1 pound cavatappi, shells, or classic elbow macaroni

1 stick unsalted butter, divided, plus extra for buttering the dish

3 cups milk

4 tablespoons all-purpose flour

6 ounces Gruyere, grated

6 ounces sharp Cheddar, grated

6 ounces Roquefort or other blue cheese, crumbled

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Pinch nutmeg

1 cup panko breadcrumbs

1 handful freshly chopped basil leaves

Directions

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F. Butter a 2-quart casserole dish.

Boil a large pot of salted water. Add the pasta and cook according to the directions for al dente on the package. Drain well.

Make the cheese sauce: While the pasta is cooking, melt half of the butter (4 tablespoons) in a saucepan over medium heat. Whisk in the flour to make a roux, stirring continuously until the mixture turns pale brown and begins to bubble, about three minutes. Slowly whisk in the milk, one half cup at a time, until the sauce thickens. Remove from the heat. Stir in Gruyere, Cheddar, Roquefort, pepper, and nutmeg.

Make the topping: Melt the remaining butter. In a small bowl, stir the panko breadcrumbs with the butter.

Transfer the macaroni and cheese to the prepared baking dish and top with the buttered panko. Sprinkle with basil. Bake until the dish bubbles around the edges, about 25 minutes. Remove from oven and let rest for five minutes before serving.

70 years of instant photos, thanks to the Polaroid camera

Shutterstock

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

It probably happens every minute of the day: A little girl demands to see the photo her parent has just taken of her. Today, thanks to smartphones and other digital cameras, we can see snapshots immediately, whether we want to or not. But in 1944 when 3-year-old Jennifer Land asked to see the family vacation photo that her dad had just taken, the technology didn’t exist. So her dad, Edwin Land, invented it.

Three years later, after plenty of scientific development, Land and his Polaroid Corporation realized the miracle of nearly instant imaging. The film exposure and processing hardware are contained within the camera; there’s no muss or fuss for the photographer who just points and shoots and then watches the image materialize on the photo once it spools out of the camera.

Land is probably best known for the “instant photo” – or the spiritual progenitor of today’s ubiquitous selfie. His Polaroid camera was first released commercially in 1948 at retail locations and prices aimed at the postwar middle class. But this is just one of a host of technological breakthroughs Land invented and commercialized, most of which centered around light and how it interacts with materials. The technology used to show a 3D movie and the goggles we wear in the theater were made possible by Land and his colleagues. The camera aboard the U-2 spy plane, as featured in the movie “Bridge of Spies,” was a Land product, as were even some aspects of the plane’s mechanics. He also worked on theoretical problems, drawing on a deep understanding of both chemistry and physics.

I’m a vision scientist who has touched many of the fields in which Land made great advances, through my own work on new imaging methods, image processing techniques and human color vision. As the 2018 recipient of the Edwin H. Land Medal, awarded by the Optical Society of America and the Society for Imaging Science and Technology, my own work relies on Land’s technological innovations that made modern imaging possible.

Controlling light’s properties

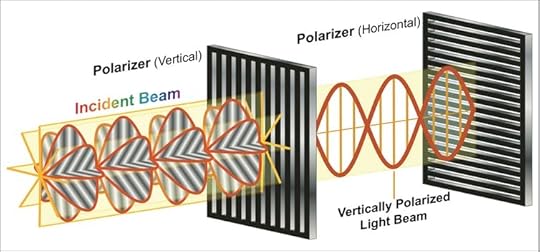

Edwin Land’s first optics breakthrough came as a young man, when he figured out a convenient and affordable method to control one of the fundamental properties of light: polarization.

You can think of light as waves propagating from a source. Most light sources produce a mixture of waves with all different physical properties, such as wavelength and amplitude of vibration. Light is considered polarized if the amplitude varies in a consistent manner perpendicular to the direction the wave is traveling.

A polarizing filter can block all the light waves that don’t match its orientation.

Fouad A. Saad/Shutterstock.com

Given the right material for the light waves to pass through, the light waves may be rotated into another plane, slowed down or blocked. Modern 3D goggles work because one eye receives light waves vibrating along the horizontal plane while the other eye receives the light vibrating along the vertical plane.

Before Land, researchers built components to control polarization from rock crystals, which were assigned almost magical names and properties, though they merely decreased the velocity or amplitude of light waves traveling at specific orientations. Land created “polarizers” by growing small crystals and embedding them in plastic sheets, altering the light passing through depending on its orientation in relation to the rows of crystals. His inexpensive polarizer made it possible to reliably and practically filter light so only wavelengths with a particular orientation would pass through.

Land founded the Polaroid Corporation in 1937 to commercialize his new technology. His sheet polarizers found applications ranging from the identification of chemical compounds to adjustable sunglasses. Polarizing filters became standard in photography to reduce glare. Today the principles of polarized light are used in most computer and cellphone screens, to enhance contrast, decrease glare and even turn on or off individual pixels.

Polarizing filters help researchers visualize structures that might not be seen otherwise – from astronomical features to biological structures. In my own field of vision science, polarization imaging localizes classes of chemicals, such as protein molecules leaking from blood vessels in diseased eyes. Polarization is also combined with high-resolution imaging techniques to detect cellular damage beneath the reflective retinal surface.

A new way to get the data out

Before the days of high-speed digital capture of data and affordable high-resolution displays, or use of videotape, Polaroid photography was the method of choice to obtain output in many scientific labs. Experiments or medical tests needed graphical or pictorial output for interpretation, often from an analog oscilloscope which plotted out a voltage or current change over time. The oscilloscope was fast enough to capture key features of the data – but recording the output for later analysis was a challenge before Land’s instant camera came along.

A common example in vision science is the recording of eye movements. A research study reported in 1960 plotted light reflected from an observer’s moving eye on an oscilloscope screen, which was photographed with a mounted Polaroid camera – not unlike the consumer Polaroid camera a family might pull out at a birthday party. For decades, research labs and medical facilities have used setups consisting of a Polaroid camera and a mounting rig to collect electrical signals displayed on oscilloscope screens. The format sizes are less than dazzling compared to modern digital resolutions, but they were revolutionary at the time.

In 1987, with the founding of my new retinal imaging laboratory, there was no inexpensive method to provide sharable output of our novel images. After a few years of struggling to obtain high-quality output for conferences and publications, the Polaroid Corporation came to our rescue, with the donation of a printer, allowing our scientific contributions to reach an audience beyond our lab.

Eyes are not cameras

Land’s contributions go beyond patenting over 500 innovations and inventing products that millions purchased. His understanding of the interaction of light and matter promoted novel ways of characterizing chemicals with polarized light. And he provided insights into the workings of the human visual system that had seemed to defy the laws of physics, coming up with what he called the Retinex theory of color vision to explain how people perceive a broad range of color without the expected wavelengths being present in the room.

Despite his brilliance, Land’s Polaroid Corporation eventually hit hard times in the decades after his death in 1991. Heavily invested in its film sales, Polaroid wasn’t prepared as all tiers of the imaging market went digital, with everyone from consumer photographers to high-end medical and optical imagers abandoning film and processing.

But rather than sink with the film market, Polaroid reinvented itself with new products that could help output the new world of digital images. And in a case of history repeating itself, Polaroid and other manufacturers of instant cameras are enjoying renewed popularity with younger generations who had no exposure to the original versions. Just like little Jennifer Land, plenty of people today still want a tangible version of their pictures, right now.

Ann Elsner, Professor of Optometry, Indiana University

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

Billionaires are rushing into biotech. Inequality is following them into science

(Wikimedia/Richard Wheeler - Zephyris)

This article originally appeared on Massive.

You exit a cramped, hazy subway car with a throng of professionals. As you emerge blinking into Kendall Square in Cambridge, MA, the crowd descends on a nest of pharmaceutical offices huddled around the Charles River, overlooking downtown Boston. MIT, Harvard, bougie cafes and hotels, trendy co-working spaces filled with startups, and giants like Google are dispersed throughout the biotech colosseum. Last but not least, there are the Institutes — the Ragon, the Koch, the McGovern, the Picower, the Whitehead, and the Broad — all named after billionaire donors seeding a stake as a powerhouse in their respective fields. And more is on the way. The Gates Foundation is building a nonprofit research institute and China is moving to secure space in the area.

You exit a cramped, hazy subway car with a throng of professionals. As you emerge blinking into Kendall Square in Cambridge, MA, the crowd descends on a nest of pharmaceutical offices huddled around the Charles River, overlooking downtown Boston. MIT, Harvard, bougie cafes and hotels, trendy co-working spaces filled with startups, and giants like Google are dispersed throughout the biotech colosseum. Last but not least, there are the Institutes — the Ragon, the Koch, the McGovern, the Picower, the Whitehead, and the Broad — all named after billionaire donors seeding a stake as a powerhouse in their respective fields. And more is on the way. The Gates Foundation is building a nonprofit research institute and China is moving to secure space in the area.

This is why biotechnology and life sciences are exceptionally strong in Boston. Almost everyone in biotech works in Boston, or works with somebody who does. It’s why they continue to bring new students from all over — and why I came here. The area is in a cycle of shared dominance with other epicenters like San Francisco, Research Triangle in North Carolina, the metropolitan New York area, and DC. But these zones represent a growing erosion of geographical diversity in America’s higher education system. These areas are raking in thousands of awards, worth billions, and are reinforced with billions of venture capital funding and huge amounts of new lab space. Even between two major centers, Boston and DC, Boston acquires151 percent more funding from the National Institutes of Health, 58 percent more patents, and 2,010 percent more venture capital investment. These are the gaps just at the top of the pyramid.