Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 72

May 18, 2018

Down the memory hole: Dismantling democracy, one word at a time

AP/Carolyn Kaster

This piece originally appeared on TomDispatch.

Consider us officially in an Orwellian world, though we only half realize it. While we were barely looking, significant parts of an American language long familiar to us quite literally, and in a remarkably coherent way, went down the equivalent of George Orwell’s infamous Memory Hole.

This hit me in a personal way recently. I was asked to give a talk at an annual national security conference held in downtown Manhattan and aimed largely at an audience of college students. The organizer, who had pulled together a remarkable array of speakers, encountered problems in one particular area: his efforts to include representatives of the Trump administration in the gathering. Initially, administration officials he dealt with wouldn’t even divulge the names of possible participants, only their titles, leaving who was coming a mystery until days before the conference opened.

In addition, before agreeing to send speakers, his contacts at Immigration and Customs Enforcement, known by the acronym ICE, had not just requested but insisted that the word “refugee” be removed from the conference program. It was to appear in a description of a panel entitled “Refugee Programs, Immigration, Customs and Border Protection.”

The reason given: the desire to get through the administration approval process in Washington without undue delay. It’s not hard to believe that the administration that wanted to slow to a standstill refugees coming to the U.S. didn't have an allied urge to do away with the very word itself. In order to ensure that ICE representatives would be there, the organizer reluctantly conceded and so the word “refugee” was dutifully removed from the program.

Meanwhile, the actual names of Department of Homeland Security officials coming to speak were withheld until three days before the event. Finally, administration representatives in touch with the conference organizers insisted that the remarks of any government representatives could not be taped, which meant, ultimately, that none of the proceedings could be taped. As a result, this conference was not recorded for posterity.

For — and I’ve been observing the national security landscape for years now — this was something of a new low when it came to surrounding a previously open event in a penumbra of secrecy. It made me wonder how many other organizers across the country had been strong-armed in a similar fashion, how many words had been removed from various programs, and how much of what an American citizen should know now went unrecorded.

To some extent, I understood the organizer’s plight, having myself negotiated requests from government officials for 15 years’ worth of national security get-togethers of every sort. As director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law and before that of a similar center at New York University School of Law, I had been asked by more than one current or former Bush or Obama administration official to not record his or her remarks. Indeed, one or two had even asked to be kept away from the audience until those remarks were delivered.

Still, most had come eager to debate, confident that their views were the preferable ones, aware that the perspectives of many in the room or conference hall would differ from theirs, often drastically, on hard-edged issues like torture, Guantánamo, and targeted killings. But one thing I know: not once in all those years had I been asked to change the language of an event, to wipe a word or phrase out of the program of the moment. It would have been an unthinkable violation.

The very idea that the government can control what words we use and don’t at a university-related event seems to violate everything we as a country hold dear about the independence of educational institutions from government control, not to mention the sanctity of free speech and the importance of public debate. But that, of course, was in the era before Donald Trump became president.

Assaulting the language of American democracy

Tiny as that incident was, at a conference meant largely for students but open to an array of professionals, it caught the essence of this administration’s take-no-prisoners approach to the language many of us customarily use to describe the country we live in. Such an assault is, of course, nothing new under Trump. After all, the current president had barely entered the Oval Office when the first reports began to emerge about instances in which language at various government websites was being altered, words and concepts being changed or simply obliterated.

Since then, the language of an America that the president and his associates reject has been under constant attack. Some of those acts of aggression were to be expected, given the campaign promises that preceded his election. Take climate change, which Donald Trump called a “Chinese hoax” long before he filled his administration with rabid climate deniers. The Department of Agriculture was typical. Its new officials excised the very word “climate change” from their website, substituting “weather extremes,” and changed the phrase “reduce greenhouse gases” to the palpably deceptive “increase nutrient use energy.” Across the board, in fact, .gov websites replaced “climate change” with vague words like “resilience” and “sustainability.”

But you don’t have to focus on the urge to obliterate all evidence of climate change, even the words to describe it. Other alterations have been no less notable. For starters, as at the recent conference I attended, there has been a clear rejection of language that connoted the have-nots, the excluded, and the marginalized of our world. At the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), for example, this year’s budget request carefully excluded such descriptors from its mission and purpose statement. Originally incorrectly reported as a policy decision to ban certain words from use at the agency, CDC officials were simply reading the tea leaves of the new administration and quickly ridding their budget requests of key words, now poison in Trump’s Washington, describing their mission. These were words suddenly seen as red flags when it came to the use of government funds to help the less fortunate or the discriminated against. Examples included "vulnerable," "entitlement," "diversity," "transgender," and "— and with science now in disrepute for its anti-fossil-fuel findings, also discarded were the phrases "evidence-based" and "science-based."

The disavowal of marginalized groups and of the vulnerable in society, including those “refugees,” has hardly been limited to the CDC. It also reared its head, for example, in the mission statement of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, where the label “nation of immigrants” was dropped from its mission statement, which now reads:

"U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services administers the nation’s lawful immigration system, safeguarding its integrity and promise by efficiently and fairly adjudicating requests for immigration benefits while protecting Americans, securing the homeland, and honoring our values."

Given the latest news from the border of children being torn from their parents and the president’s recently reported cabinet rant about not yet securing the border effectively, no one should be surprised that “security” and “values” have trumped “immigrants” and inclusion in that mission statement. So, too, has such a mindset left its mark on another agency created to help out those in need. The Department of Housing and Urban Development, led by Ben Carson, has ditched the terms “free from discrimination,” “quality homes,” and “inclusive communities” in favor of a mission that supports “self-sufficiency” and “opportunity.” In other words, the onus is being put on the individual rather than the government.

Trump is hardly the first president to discover the importance of language as a political tool that can be self-consciously used for practical ends. Barack Obama, for instance, banished both the name “war on terror” for America’s unending post-9/11 conflicts across the Greater Middle East and Africa and “Islamic extremist terrorism” for those we fought -- even though that “war” went right on. Still, the current president may be the first whose administration hasn’t hesitated to delete terms tied to the foundational principles of the country, among them “democracy,” “honesty,” and “transparency.”

Putting a fine point on the turn away from core values, for instance, the State Department deleted the word “democratic” from its mission statement and backed away from the notion that the department and the country should promote democracy abroad. In its new mission statement, missing words also included “peaceful” and “just.” Similarly, the U.S. Agency for International Development’s mission statement veered away from its prior emphasis on “ending extreme poverty and promoting the development of resilient, democratic societies that are able to realize their potential.” Its goal, it now explains, is “to support partners to become self-reliant and capable of leading their own development journeys” largely through increased security (including presumably the purchase of American weaponry) and expanding markets.

Alongside a diminished regard for the very thought of inclusiveness and for helping impoverished nations improve their conditions through aid, the idea of protecting civil liberties has taken a nosedive. President Trump’s first appointee to head the Guantánamo Bay Detention Center, Rear Admiral Edward Cashman, for example, took the words “legal” and “transparent” out of the prison facility’s mission statement. In a similar fashion, the Department of Justice has excised the portion of its website devoted to “the need for free press and public trial.”

A ministry of propaganda?

Meanwhile, in a set of parallel moves of betrayal, the dismemberment of agencies created to honor and protect peacefulness and basic civil liberties at home or abroad is ongoing. At the moment, for instance, less than half of the top positions at the State Department have been filled and confirmed. The fallout is clear: ambassadors to countries of major importance in current tension-ridden areas and the very concept of diplomacy that might go with them are missing in action. That includes the ambassadors for Libya, Somalia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates, and Syria. Meanwhile, in the first year of the Trump era, nearly 2,000 career diplomats and civil servants were pushed out of the department and, by the time Secretary of State Rex Tillerson went the way of so many Trump appointees, top posts there had been halved. In an Orwellian world, agencies stripped down to bare minimum staffs and leadership are that much easier to tilt and turn in grim new directions.

Similarly, the Trump administration has all too often endeavored to disavow or obliterate facts. It’s not just a matter of endlessly reported presidential lying and misstatements, but of a wholesale disregard for reality that can again be seen at government websites where factual information of all sorts has been tossed down the memory hole. References to climate change disappeared from the White House website on Inauguration Day 2017. Many references and links to climate change put up during the Obama years were, for example, quickly removed from the State Department’s website, and other agency websites followed this pattern.

Similarly, the White House website wiped out pages focused on federal policies toward people with disabilities, leaving only this message for interested citizens: “You are not authorized to access this page.” Nor does the administration evidently feel any responsibility to issue reports to the public on its activities, including those that might damage respect for Americans worldwide. Recently, the Trump administration missed a deadline for reporting on civilian casualties resulting from U.S. drone strikes, a yearly requirement established by President Obama in 2016. A White House spokesperson explained that such a reporting requirement was “under review” and could be “modified” or “rescinded.”

Such an approach to what should and shouldn’t be known about and available to citizens from a government still theoretically of, by, and for the people has regularly been described as fascist, Stalinist, totalitarian, or authoritarian. More important, however, than any labels is the recognition that, whatever you might call it, there is indeed a strategy at work here. This is, in fact, a far less ad hoc and amateurish administration than pundits and politicians assume. Trump associates like to talk about the in-the-moment quality of present White House decision-making, but the concerted, continual, and consistent on-message attack on words, phrases, and language that offends those now in office seems to contradict that notion.

What we are evidently living through is a coordinated attack on the previous American definition of reality. The question is: Where do such directives come from? Who has identified the words and concepts that need to be deleted from the national lexicon? However unknown to us, is there a virtual minister or ministry of propaganda somewhere? Is there someone monitoring and documenting the progress of such a strategy? And what exactly are the next steps being planned?

Whatever the circumstances under which this is happening, it certainly is a bold attempt to use language as a doorway that will take us from one reality — that of the past 250 years of American history and its progression towards inclusion, diversity, equal rights for minorities, and liberty and justice for all — to another, that of an oligarchically led transformation focused on intolerance, racial and ethnic divides, discrimination, ignorance (rather than science), and the creation of a state of unparalleled heartlessness and greed.

It might be worth reflecting on the words of Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister for Hitler’s Nazi Party. He had a clear-eyed vision of the importance of disguising the ultimate goal of his particular campaign against democracy and truth. “The secret of propaganda,” he said, is to “permeate the person it aims to grasp without his even noticing that he is being permeated.”

Consider this a word of warning to the wise. Perhaps instead of hurling insults at President Trump’s incompetence and the seeming disarray of his presidency, it might be worth taking a step back and asking ourselves whether there is indeed a larger goal in mind: namely, a slow, patient, incremental dismantling of democracy, beginning with its most precious words.

Karen J. Greenberg, a TomDispatch regular , is the director of the Center on National Security at Fordham Law and the author of Rogue Justice: The Making of the Security State . Samuel Levy, Hadas Spivack, and Anastasia Bez contributed research for this article.

Copyright 2018 Karen J. Greenberg

To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.

May 17, 2018

Is a gullible Donald Trump being taken for a ride by North Korea?

AP/Evan Vucci/Getty/KCNA

It seems like ages ago when political leaders were seriously talking about President Donald Trump winning a Nobel Peace Prize. In light of North Korea's suspension of talks with South Korea over the Max Thunder aerial drills, and national security adviser John Bolton's comparison of upcoming talks with North Korea to those undertaken with Libya in 2003, the question is now twofold: Will the proposed summit between Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un happen at all? Or are the North Koreans simply taking Trump for a ride.

"I'll begin with the caveat that most everybody would make," said Tony Arend, a professor and dean in the Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, in an interview with Salon. "That is, we don't fully understand what's in the mind of Kim Jong-un on a variety of issues and we're always trying to get more intelligence.

"That having been said, my perception is that he is feeling that he has gotten a lot of recognition from the United States," Arend continued. "He's gotten the president of the United States to agree to a summit to discuss issues on the [Korean] peninsula, and I think he's pushing to see how much he can get from the United States in the way of concessions. So he perceives himself to be in a position of strength."

If the Trump administration "seems so invested in a deal," Arend went on, Kim might be eager to see what further concessions it is willing to grant. "So I see him testing the waters and pushing the United States."

His views were largely shared by Gordon Chang, a Daily Beast columnist and author of "Nuclear Showdown: North Korea Takes on the World."

"North Korea has talked about John Bolton and his 'hostile attitudes,' as they put it," Chang told Salon, adding that he doubted Bolton's comments about the "Libyan model" played a major role, since those were made during a "Face the Nation" interview in late April. "After that, the North Koreans released the three Americans, so it's unlikely that Bolton was the motivating factor," Chang said. "I think there must have been something else that got the North Koreans upset."

Chang then speculated that one factor could well have been Secretary of State Mike Pompeo's offer to take North Korea of the official U.S. list of "state sponsors of terrorism" if the Kim regime hands over five nuclear devices. "That's much closer in time to North Korea's statement," he said, "and it also corresponds with something that North Korea said in that statement ... is about compensation for giving up their most destructive weapons."

"There are things that the North Korean aren't saying," Chang said. "I think they're using Bolton as an excuse."

Ankit Panda, adjunct senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists, told Salon that North Korea may also have concerns about whether recent American rhetoric and foreign policy actions — particularly Bolton's comments and the South Korean aerial tests — reflected a lack of seriousness about the proposed diplomatic talks.

One interpretation Panda offered was that the North Koreans "effectively thought the U.S. wasn't being serious, was running sort of an arrogant victory lap before the talks had taken place, and was still setting up complete denuclearization as the benchmark. So they put out a statement saying that we can't really meet on the basis of that because we're not going to give up our nuclear weapons.

"None of this is surprising to people who have been watching the Korean peninsula for a long time," Panda concluded. "North Korea has taken a similar approach to talks with the United States before, but the Trump administration, either willfully or by accident, simply hasn't paying attention to the details."

One underlying problem, as foreign policy experts have previously told Salon, is that Trump already made a major diplomatic concession to Kim Jong-un by agreeing to meet with him, something no previous U.S. president has ever done. As a result, North Korea is now in a position to humiliate Trump if he fails to extract major concessions from the Kim dictatorship. In typical fashion, Trump has made clear that he hopes to achieve a lasting peace between North and South Korea, a maddeningly difficult goal that is of course impossible without North Korean cooperation. Kim's government understands this perfectly well.

The North Korean "end game," Chang said, "is to keep their most destructive weapons, have a meeting with President Trump which legitimizes Kim Jong-un, and be able to continue to threaten the rest of the world. Getting relief from sanctions, getting money from South Korea ... there's a whole laundry list of things that they want. The question is whether they'll get them or not, which is a different story. And it's up to President Trump to make sure that they don't."

Arend noted that North Korea may simply be preemptively establishing the pretext it can use to undermine the Trump-Kim summit, if and when it actually happens.

"It could also simply be a way of North Korea scuttling the summit and scuttling any kind of agreement by putting up this roadblock, and then if the United States doesn't agree to it, to say, 'Well, we're just not going to be able to move forward,'" Arend said. "Then Kim Jong-un can present himself as saying, 'I was being cooperative. I was being collaborative. I returned the three hostages ... I tried, but the United States once again was an impediment to any kind of peace discussions.'"

The risk of nukes and North Korea

Matthew Rozsa talks with Laura Rosenberger, director of the Alliance for Securing Democracy, about the threat posed by North Korea.

Millennial women say dismal economy is preventing them from having children

Shutterstock

The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) released updated statistics regarding the country’s fertility rate — the pace at which American women in their childbearing years are having children — and according the data, it has reached a record low for the second year in a row.

The U.S. fertility rate decreased to 60.2 births per 1,000 women in 2017, a 3 percent decrease from 2016. The report also showed that birth rates — the number of live births per 1,000 people — declined for nearly all age groups under the age of 40, though increased for women in their early 40s.

As Pew Research Center has previously explained, this is not exactly a cause for concern for economists. It is also debatable as to whether this historically low fertility rate constitutes an “all-time low” as some described it, due with the way in which the rates are calculated.

Yet since the report's release, researchers have been publicly expressing surprise over the decline. The number of women in their childbearing years is increasing, but fewer children are being born. And while fertility rates usually fall during recessions, as they did during the 2008 financial crisis, they have not recovered since.

So what exactly is going on?

As one might expect given the demography of who is child-bearing age, the dip in fertility rate can be largely be attributed to two cohorts: teens and Millennials. A decrease in teen pregnancies is a good thing — that could likely be attributed to better sex education programs and birth control.

But Millennials are in their mid-twenties and thirties. Wouldn't one expect their fertility and pregnancy rates to be increasing, not decreasing?

“It's definitely true that a smaller share of Millennial women [ages] 20 to 35 are moms (48%) today compared with the share of Gen X women who were moms by that same age (57%),” Gretchen Livingston, a senior researcher at Pew Research, told Salon. “It's possible that Millennial women are delaying motherhood because of economic anxieties, but we do not have evidence that explicitly shows that.”

William Frey, a demographer at The Brookings Institution, said the dip in Millennial women having children caught his interest.

“What really hit me with these new numbers is the sustained decline for women in their twenties,” Frey told Salon. "Millennial women have been the most affected by the economy, putting their lives on hold... they also have something other generations haven't had: college debt."

Millennial women started entering the workforce at the end of the Great Recession, yet static wages and the increase in the cost of living that followed put many Millennial women in poor financial situations to have children. Add record-breaking student debt loads to the equation, and you have a formula for low fertility rates.

Many of the Millennial and Generation X women who spoke to me for this article and who were interested in having children cited economic uncertainty as one prominent reason that they have decided not to have children yet, or in some cases to delay the decision. In a country where merely giving birth can cost over $31,000, who can blame them?

Genevieve Diaz, a 27-year-old who lives in San Francisco, says that when she made the transition from working at a tech company to freelancing and starting her own business, the thought of having children seemed to be less attainable prospect for her.

“The thing I think about is by the time I pay off my student debt, will I still be able to have kids?” she told Salon. “Will I have enough time to be fertile, have kids, and build this business, put food on the table for myself, and live in San Francisco?”

Kelsi*, a 25-year-old who lives in Hawaii, had trouble envisioning being in a financial position to have kids. Growing up in a low-income family, Kelsi had to quit dance lessons after her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, as her family couldn’t afford to pay a babysitter to watch her during her mother's chemotherapy sessions. Later, Kelsi worked as a nanny for wealthy families, and saw the difference firsthand in how money helps when having children.

“I would want that type of lifestyle for my kids,” she told Salon. “I love kids, I was an excellent nanny and know I would be an excellent mother. However, I'm realistic that I will likely never have enough money to give my children the type of lifestyle they would deserve.”

She also has $250,000 in student loan debt.

The economic anxieties of having children are not exclusive to women in their twenties. These worries are also burden to those in their 30s and older. Eloise Merrifield, who is 36, relocated with her partner of three years for a new job to Sacramento, California. Merrifield went to law school when she was 29, and thus expected a delay in having children, but said the delay is now almost certainly due to financial insecurity, as her partner is still looking for a new job.

“Knowing that the likelihood that I’ll be over 40 when we start trying for a family bums me out,” she told Salon. “But trying before we are financially stable enough to take care of a kid scares me more.”

Meghan* lives in Florida, and had to wait until she was 33 to have a child because of her financial concerns. As a licensed mental health counselor at a nonprofit, she does not make a lot of money, despite having a master’s degree.

“I wasn’t even making enough to live alone, I was living with a roommate until I was 30,” she told Salon. “Living alone wasn’t possible, and I would constantly think, 'wow, what would happen if I had a kid?'”

Eventually she met her partner and moved in together; still, finances were a huge concern when it came to bearing children.

“As awful as it sounds, my mom passed away and she left me an inheritance where we could afford to have kids,” she told Salon.

Even with the inheritance, she estimates she spends $1,200 a month on daycare. She said her and her partner would like to have one more child, but have decided not to at this time because affording the cost of daycare for two children “is not a reality.”

*Editor's note: Some subject's names have been changed due to the sensitive nature of the topic.

In defense of fish parasites

Shutterstock

It's hard to make the case for fish parasites (which yes, this article is going to do). For one thing, most people love eating fish; personally, I resisted when I was younger but succumbed as an adult. Fish are tasty, healthy, and can be prepared in a variety of ways.

More important, though, is the fact that most people hate parasites. And it's kind of hard not to, especially when there are stories like this one from The Washington Post in January floating around the internet:

It was a Monday in August last year when the man showed up in the emergency room of UCSF Fresno's Community Regional Medical Center clutching a plastic grocery bag and asking doctors to treat him for tapeworms — parasites that can invade the digestive tract of animals and humans. Banh said he didn't think too much of it; he had heard patients express similar concerns about tapeworms in the past.

Banh opened the sack.

Inside, he said, was a cardboard toilet paper tube — with a tapeworm wrapped around it.

Banh said the worm was dead when he saw it but noted the man told him “it was alive when he pulled it out and it was wiggling in his hand.” Banh stretched it out on the ER floor and measured it — all 5½ feet of it, he said in an interview Friday with The Washington Post.

“It got long enough that some of it was sneaking out of him,” he said about the parasite.

And yes — it is believed that the man in that story contracted the fish parasite by eating sashimi, another term for raw or undercooked fish.

"Animals get sick and carry pathogens, just like people, and there is an elevated risk of contracting a food-borne illness when eating raw meat or fish," Dr. Jillian Fry, Project Director of the Public Health & Sustainable Aquaculture Project at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told Salon. "Sensitive populations, like pregnant women and people with a compromised immune system, should avoid eating raw meat or fish for this reason. When consuming raw fish, consumers should eat at reputable businesses with good food handling practices."

She added, "The possibility of a tapeworm infection is very unappetizing, but it is not a reason to avoid eating fish; the current risk level is low and there are effective and safe treatments for tapeworms."

Fry's verdict was echoed in the abstract of a 2005 article in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases called "Sushi Delights and Parasites: The Risk of Fishborne and Foodborne Parasitic Zoonoses in Asia," which warned that the growing popularity of Japanese cuisine carried with it certain unpleasant health risks:

Because of the worldwide popularization of Japanese cuisine, the traditional Japanese fish dishes sushi and sashimi that are served in Japanese restaurants and sushi bars have been suspected of causing fishborne parasitic zoonoses, especially anisakiasis. In addition, an array of freshwater and brackish-water fish and wild animal meats, which are important sources of infection with zoonotic parasites, are served as sushi and sashimi in rural areas of Japan. Such fishborne and foodborne parasitic zoonoses are also endemic in many Asian countries that have related traditional cooking styles. Despite the recent increase in the number of travelers to areas where these zoonoses are endemic, travelers and even infectious disease specialists are unaware of the risk of infection associated with eating exotic ethnic dishes.

In short: While stories like the fish parasite one from January are unappealing, to say the least, the reality is that we should not be concerned about there being too many parasites. We should be worried about how changes to our environment — and, specifically, global warming — might be causing an ecologically dangerous reduction in the number of parasites.

"Ironically, one of the very few 'positive' impacts of global warming could be a decrease in some of the most horror-inducing parasites like tapeworm," Michael E. Mann, a distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University, joked in an email to Salon. After referring me to a New York Times article from last year by Carl Zimmer, Mann said, "I’m being intentionally a bit glib here of course, because the demise of parasites in general could have larger negative ramifications for food webs and ecosystems."

He added, "Loss of species, in general, is not a good thing."

This notion was shared by Zimmer's article, which argued that "as much as a tapeworm or a blood fluke may disgust us, parasites are crucial to the world’s ecosystems. Their extinction may effect entire food webs, perhaps even harming human health." After detailing an extensive study led by University of California, Berkeley graduate student Colin J. Carlson on how global warming will impact parasite species, Zimmer described the impact that the mass extinction of various parasitic species may have on the planet (the study projected that roughly 30 percent of them could disappear).

Mr. Carlson said that climate change would do more than just drive some species extinct. Some parasites would move into new territory.

Deer ticks, for example, spread Lyme disease, and climate change models suggest they have a rosy future as they expand northward. “We’re not worried about them going extinct,” said Mr. Carlson.

Migrating parasites like these will arrive in ecosystems where other parasitic species are disappearing. With less competition, they may be able to wreak more havoc — and not just on animal hosts. Many human diseases are the result of parasites and pathogens jumping from animal species to our own.

“If parasites are keeping disease down in wildlife, they might also be indirectly keeping them down in humans,” Mr. Carlson said. “And we might lose that.”

There are two lessons that can be learned from these stories:

1. While you shouldn't shy away from exotic cuisines that you love out of fear, it is important to exercise caution about what you put into your body. Because raw and undercooked seafood can often be riddled with parasites, make sure that you do not eat those foods unless you know they are being sold by reputable stores, restaurants and other vendors.

2. Parasites, both those that come from fish and animals that live in other types of hosts, play an important role in our ecosystem. It is important to look at the planet beyond the interests of our own species and appreciate how even the most disgusting organisms can still be essential for its survival.

This last point doesn't mean that we have to like parasites. It just means we have to recognize that they are still important.

Top Trending

Check out the most recent news stories below.

We need to talk about “Avengers: Infinity War”’s treatment of Mantis

Marvel Studios/Disney

"Avengers: Infinity War" is a film up to its eyeballs in superheroes. In fact, there are superheroes of almost every variety: the technologically advanced, the genetically modified, the masters of magic, and even a god or two. That said, one can’t really be angry that Mantis, the newest member of the Guardians of the Galaxy, didn’t have many lines of dialogue. Though, one can certainly be disappointed with what she said in those limited lines, particularly the way in which she underestimated her own empathic abilities.

"Avengers: Infinity War" is a film up to its eyeballs in superheroes. In fact, there are superheroes of almost every variety: the technologically advanced, the genetically modified, the masters of magic, and even a god or two. That said, one can’t really be angry that Mantis, the newest member of the Guardians of the Galaxy, didn’t have many lines of dialogue. Though, one can certainly be disappointed with what she said in those limited lines, particularly the way in which she underestimated her own empathic abilities.

During the course of the film, Iron Man, Star-Lord, Spider-Man, Nebula, Doctor Strange, Drax, and Mantis find themselves on Titan, Thanos’s home planet. It’s about the most unlikely group of superheroes — some Avengers, some Guardians, and, um, Doctor Strange — but the team works quite well. Together, they devise a plan to take down Thanos by relying on the individual strength of each character. It really wasn’t a bad plan, as Doctor Strange’s mystical arts, Spider-Man’s web shooters, and Mantis’s empathic ability confused, overwhelmed, and disabled Thanos enough so that Tony Stark was this close to taking the gauntlet. That is, until Star-Lord went and did the thing that Star-Lord did. But Star-Lord has always been a charming screwup, so it’s unfair to hold the annihilation of half the galaxy against a personality trait the audience already knew he had.

Read the rest of the article at The Mary Sue.

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

Judge rejects Trump’s request to halt Summer Zervos suit

Getty/Valerie Macon

A New York Appeals Court rejected President Donald Trump’s request to halt further legal proceedings in a defamation case filed by Summer Zervos, a former contestant on “The Apprentice,” the Washington Post reports.

Zervos alleges that Trump sexually harassed her; she she filed for a defamation lawsuit after he denied her accusations publicly. Recall, Trump called Zervos, and the other women who have accused him of sexual harassment, “liars.”

The report surmises that this legal setback could open Trump up to discovery in the case, lest he continue to attempt to legally delay proceedings. Trump’s attorney has tried to argue that when he called the women “liars,” he was expressing a political opinion. New York Supreme Court Justice Jennifer G. Schecter dismissed that claim in an opinion in March.

“No one is above the law,” Schecter wrote.

Trump appealed that opinion, which is the request the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court denied today. They described it as “a stay of the action pending hearing and determination of Trump’s appeal of Schecter’s order,” via the Post’s report.

Marc Kasowitz, an attorney for Trump, criticized the appeals court’s decision to the Post via email. According to the report:

Marc Kasowitz, an attorney for Trump, called the appeals court’s decision incorrect, citing an earlier case against President Bill Clinton that stemmed from a sexual harassment claim. Kasowitz wrote in an emailed statement that it was “completely and unjustifiably contrary to the stays the courts uniformly granted when deciding whether a lawsuit against President Clinton could proceed in federal court.”

“There is no valid reason in this case — in which plaintiff is seeking merely $3,000 in damages, and which plaintiff’s counsel has repeatedly insisted was brought for political purposes — for the Court not to grant the requested stay in order to take the time to first decide the threshold Constitutional issue that is at stake,” he continued.

Zervos’ attorney, Mariann Meier Wang, said in a statement she "look[s] forward to proving Ms. Zervos’s claim that [Donald Trump] lied when he maliciously attacked her for reporting his sexually abusive behavior."

Trump is also facing a separate defamation lawsuit by Stormy Daniels, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford. The defamation lawsuit is a response to when Trump called her a "con job" after she released a sketch of a man who allegedly threatened her to be quiet about their alleged affair.

“A sketch years later about a nonexistent man,” Trump on Twitter. “A total con job, playing the Fake News Media for Fools (but they know it)!”

A sketch years later about a nonexistent man. A total con job, playing the Fake News Media for Fools (but they know it)! https://t.co/9Is7mHBFda

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 18, 2018

In defense of Florida: “I would much rather find humanity in a place like that”

Getty Images

This feature is part of Salon’s Young Americans initiative, showcasing emerging journalists reporting from America’s red states. Read more Young Americans stories.

Florida holds a special place in the country’s imagination. It’s the home of Disney World. Alligators fight pythons on golf courses. People move here for the beach, and a second chance.

Florida holds a special place in the country’s imagination. It’s the home of Disney World. Alligators fight pythons on golf courses. People move here for the beach, and a second chance.

But the state, so full of possibilities, isn’t always the paradise people expect. Because of laws and geography, Florida seems to amplify the country’s problems with drugs, guns and income disparity. This tension of sunshine and scandal makes Florida unique, and few write about it better than Sarah Gerard. She’s a true Floridian, one who revels in the state’s idiosyncrasies and a good key lime pie from that one place near the beach.

Her essay collection "Sunshine State" deftly examines her relationship to Florida, a state full of characters often misunderstood by outsiders. Gerard, who gained acclaim for her 2015 novel "Binary Star," looks at Florida with a loving yet measured eye, and last year the book landed on a bunch of best-of-the-year lists.

We both grew up in the same part of town in Pinellas County, and Gerard, who’s about three-quarters through a new novel and currently lives in New York City, plans to move back to the area this summer. The rent’s too high to make art, she said, and in this political climate, she believes her vote and voice means more in Florida than it does in New York.

In your "Sunshine State" essay “Records” you talk about high school partying in Ybor. I used to do the same, but reading about it helped me realize how dangerous it all was.

When you’re a teenager you think you know everything, like, "I got this under control, nothing bad is going to happen." It was definitely reckless. I convinced myself that it wasn’t dangerous because a lot of the people I was doing it with had done it before and they “knew how,” like my boyfriend at the time. But in retrospect he was a pretty serious drug addict, so what did he know. I was hungry for any kind of experience. Anything that would give me a thrill.

Same. I went to a Christian School with a morality contract, but in Tampa I thought I could do whatever I wanted.

Yeah, across the bay — no one is going to see me over here. God can’t see me in Tampa. A lot of that stuff I was doing in St. Petersburg, too. I would go to raves in Tampa. I’d say Tampa bay is a pretty liberal place, but there are also a lot of staunch conservatives throughout all of Florida and in Tampa Bay. I’m thinking about the massive Confederate flag that flies over I-75. Or Dixie Hollins high school, whose mascot is a rebel. They make the argument for Southern Pride or celebrating our pride, but why do we need this? Why do we need to continue celebrating this fucked up heritage?

There’s always the conversation that Florida’s not the South.

It is the South. It is very heavily. A lot of my friends growing up have Southern accents. When my girlfriend and I were down in April for my book tour we were driving — I can’t remember where, somewhere in the middle of the state — and we stopped at a gas station. We were kissing in a parking lot and suddenly I realized everyone was staring at us. I actually can’t kiss you here, it’s not safe. It was a scary realization. People were openly staring. Florida is absolutely South — some areas more than others.

It’s such a long state, and not every county has the same rights for the LGBT community.

As an artist I don’t want to be in a place where I’m completely comfortable all the time. It’s not a way for me to grow as a person. It’s not a way for me to make interesting art that I think is important.

I feel pampered in New York, politically. It’s very easy to get involved, which is a great thing. But I don’t really feel like I’m needed in the room, because a lot of people are already there. For the political work that I want to do, I want to be in a place where there’s some resistance or where it needs to happen. I think my vote matters more in Florida than it does in New York.

Sometimes Floridians don’t want to tell people we’re from the state because of the reputation, and people say, "Oh, you must be crazy."

I think when people hold that kind of opinion, it’s because they’re unaware of their classist and ableist inclinations. A lot of the people I grew up with have gone to prison for drug offenses. I could have just as easily gone to prison for a drug offense when I was living in Florida, but I don’t think that addiction makes you a bad person or low class. I think the idea of high or low class is so stupid. It’s so shallow.

There are a lot of interesting characters in Florida. I also have an intimate understanding of some interesting characters that non-Floridians find inexplicable or off-putting at first. To me, they’re very endearing. I understand them. As a writer, I’m always looking for interesting characters, and it’s also just a really beautiful landscape. It’s a beautiful setting.

Last night I watched "The Florida Project" — it’s really good. Some of the cinematography was beautiful because there’s a talented cinematographer, but always because it’s a very photographic place. It’s very colorful. There’s a lot of green space. You have places like Twistee Treat that is shaped like an ice cream cone. It’s almost comical. We have exotic plants. Some of the most beautiful sunsets in the world. The beach.

You have the nice beach houses, and there’s the actual beach where anyone can go.

There are all these public spaces where people of all walks of life intermingle. On the beach, everyone is in a bathing suit. You don’t know what kind of house they live in. It doesn’t matter what the shape of their body is. You get so used to all these different kinds of body types when you’re at the beach, too.

I never thought about that.

It was one of the most freeing experiences when I was in an eating disorder rehab. I was there for two months, and toward the end we went to the beach. At first I was terrified that I had to wear a bathing suit because everyone would see me. But once I got there I was like oh, here’s this 80-year-old woman who doesn’t care at all what you think of her body. It was very liberating.

I started my recovery in Florida, too, but people have this image it’s always spring break.

Maybe it’s because of the leisurely lifestyle and people think that they should should go to a place of leisure for recovery. And a lot of people go to Malibu, too.

And that’s expensive.

Yeah exactly, so Florida’s cheaper and easier to get on your feet. I mean, we’re leaving New York because it’s too expensive. In Florida we can have green space, sunshine, and time. I don’t have a lot of grass here in New York.

When I lived in St. Petersburg [Florida] I had time to write in the afternoons, and I didn’t feel a whole lot of pressure to make money like I do in New York. I could actually take an afternoon off and work on my novel. I began to identify as a writer because I had space and time to do that. I didn’t need to put a lot of pressure on my writing to make money because my rent was super cheap at the time. My studio apartment in New York costs $1,100, which is considered cheap, and it takes me 45 minutes to an hour to get to lower Manhattan. I’m pretty remote, and my apartment is still pretty expensive. It’s like 460 sq. feet so I have no space at all. Comparatively speaking, it’s easy to be an artist in Florida and sunshine is good for your mental health.

Contrary to that trope that unhappy artists make better art, it’s not true. When you’re suicidally depressed, you’re not going to want to get out of bed and write something. You’re not going to have that kind of motivation. It’s much more conducive to making good art to have a healthy, happy, safe mind and to have some distance from your emotional trauma.

How do your collages factor into that part of your writing?

They’re outgrowths of an artistic impulse. Sometimes I’ll become interested in a certain topic and the best way to explore that topic is with text and that’s what happens most of the time. But sometimes there’s not a story so much that can be articulated linearly, and it’s a different process of exploring materials. Collages are much more freeform way of creation for me. I put much less pressure on my collages than I do with my writing. I don’t expect them to be perfect. I can’t control the outcome as much as I can with writing, so I think it’s a healthy exercise for me because I can be a little bit perfectionistic.

It’s good to do something creative that you just like.

I didn’t know that I was good at collage until I started making them. I never went to school for it. I never had the goal of a solo show or having work in a permanent collection. It’s not about that. It’s just a form of play. I use the collages as a springboard for ideas and as a way of unsticking myself when I get stuck. It’s a way to depart from the writing and let my brain doing the work for me instead of trying to force and outcome. If I don’t know what’s coming next, I get up and go to my drafting table to work on a collage. My brain is still making connections. Not every feeling has a clear verbal articulation. I might not know how to explain what I’m feeling in the writing, so the collage kind of helps my ideas.

Making art takes so much energy.

Exactly. It’s time, it’s energy. You need space to make art. You need privacy to make art. You’re not going to get any of that in rehab if that’s where you end up.

Or New York, it seems.

Every time you walk outside, it costs $50.

In Florida you can pay $75 to swim with manatees. My girlfriend and I did it with my family over Thanksgiving. They took us out on the boat, gave us wetsuits, and went diving in three sisters spring and a fucking manatee swam up to my mom and kissed her on the face. You can do that down there.

I love manatees so much.

I know, me too. I’m so glad they’re not endangered anymore. I think last year I saw it, and I was like crying because I was so happy. They’re still protected but not endangered.

There is a lot of nature here. We used to kayak, and an alligator would just swim under us.

And that’s the other thing, too. There are so many wrong stereotypes about Florida. First of all, alligators are not that vicious. They’re actually pretty chill. They don’t want anything to do with you. You can walk right up to one of them and won’t even notice you’re there if it’s the right time of day, not feeding time. Wildlife is one of my top five reasons to move back.

The other day I saw a dolphin jump out of the water, then a hawk flew over with a fish in its mouth.

Florida so fucking magical. It’s very picturesque but also kind of seedy and grungy. One of the reasons I’ve always felt like an outsider in New York is because there’s always this pressure to present and imitate high society. I can’t do that regularly. I just don’t give a fuck.

I would much rather be in the Emerald Bar than the Astor Hotel. It’s just not my style. It just makes me very uncomfortable, and I find that kind of posturing distasteful. I’ve always found myself more comfortable in places like Florida where people are a little bit more downtrodden. They have real life experiences. I would much rather find humanity in a place like that.

The above interview has been edited for length and flow.

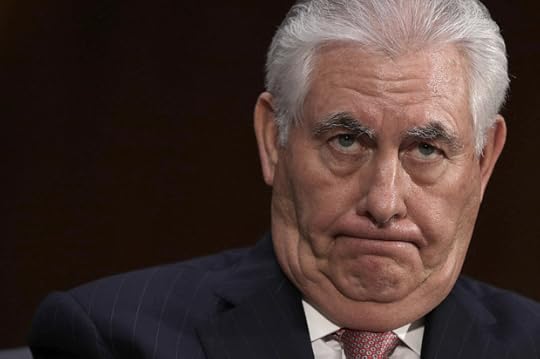

Rex Tillerson makes veiled attacks on Trump in speech

Getty/Alex Wong

It's hard to listen to former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson's commencement speech at the Virginia Military Institute and not conclude that he was talking about his erstwhile boss, President Donald Trump.

Consider this passage:

If our leaders seek to conceal the truth or we as people become accepting of alternative realities that are no longer grounded in facts, then we as American citizens are on a pathway to relinquishing our freedom.

In addition to taking a swipe at Trump's penchant for playing fast and loose with the facts, Tillerson's speech seemed to reference an infamous line from Counselor to the President Kellyanne Conway about "alternative facts." Consequently Tillerson's description of respect for the truth as a "central tenet of a free society" seemed to imply that dishonesty is not only wrong, but a threat to freedom.

Tillerson also had this to say:

When we as people, a free people, go wobbly on the truth — even on what may seem the most trivial of matters — we go wobbly on America.

He added:

If we do not as Americans confront the crisis of ethics and integrity in our society and among our leaders in both public and private sector — and regrettably at times even the nonprofit sector — then American democracy as we know it is entering its twilight years.

To be fair to Trump, the reference to the nonprofit sector makes it unlikely that this section was meant to refer to the president. On the other hand, it is hard to imagine that the man who just finished working with a president under a cloud of scandal wasn't at least thinking of his commander-in-chief when he commented that "without personal honor, there is no leadership."

Tillerson went on to say:

But a warning to you as you leave this place — a place where the person sitting on either side of you shares that understanding. You will now enter a world where, sadly, that is not always the case. And your commitment to this high standard of ethical behavior and integrity will be tested.

Tillerson left the White House with a speech that took a hard line toward Russia, something that Trump has been unwilling to do, perhaps foreshadowing his speech at the Virginia Military Institute. Tillerson was also reported to have privately referred to the president as a moron last year and to have been tempted to resign after the president made a politically charged speech to a Boy Scout convention.

On the other hand, Tillerson's tenure as Secretary of State was tainted by the fact that he left numerous positions unstaffed, a decision that many foreign policy experts believe weakened the department. He also took a softer approach toward protecting human rights than many of his critics would have liked, contradiction the philosophical approach of many of his predecessors.

All of this means that, while Tillerson's words about his former boss may ring true, this last statement could have an uncomfortable meaning for himself as well as the president.

Blessed is the man who can see you make a fool of yourself and doesn’t think you’ve done a permanent job. Blessed is the man who does not try to blame all of his failures on someone else. Blessed is the man that can say that the boy he was would be proud of the man he is.

Top Trending

Check out the latest news stories here!

The science of the plot twist: How writers exploit our brains

Getty/g-stockstudio

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Recently I did something that many people would consider unthinkable, or at least perverse. Before going to see “Avengers: Infinity War,” I deliberately read a review that revealed all of the major plot points, from start to finish.

Don’t worry; I’m not going to share any of those spoilers here. Though I do think the aversion to spoilers — what The New York Times’ A.O. Scott recently lamented as “a phobic, hypersensitive taboo against public discussion of anything that happens onscreen” — is a bit overblown.

As a cognitive scientist who studies the relationship between cognition and narratives, I know that movies — like all stories — exploit our natural tendency to anticipate what’s coming next.

These cognitive tendencies help explain why plot twists can be so satisfying. But somewhat counterintuitively, they also explain why knowing about a plot twist ahead of time — the dreaded “spoiler” — doesn’t really spoil the experience at all.

The curse of knowledge

When you pick up a book for the first time, you usually want to have some sense of what you’re signing up for — cozy mysteries, for instance, aren’t supposed to feature graphic violence and sex. But you’re probably also hoping that what you read won’t be entirely predictable.

To some extent, the fear of spoilers is well-grounded. You only have one opportunity to learn something for the first time. Once you’ve learned it, that knowledge affects what you notice, what you anticipate — and even the limits of your imagination.

What we know trips us up in lots of ways, a general tendency known as the “curse of knowledge.”

For example, when we know the answer to a puzzle, that knowledge makes it harder for us to estimate how difficult that puzzle will be for someone else to solve: We’ll assume it’s easier than it really is.

When we know the resolution of an event — whether it’s a basketball game or an election — we tend to overestimate how likely that outcome was.

Information we encounter early on influences our estimation of what is possible later. It doesn’t matter whether we’re reading a story or negotiating a salary: Any initial starting point for our reasoning — however arbitrary or apparently irrelevant — “anchors” our analysis. In one study, legal experts given a hypothetical criminal case argued for longer sentences when presented with larger numbers on randomly rolled dice.

Plot twists pull everything together

Either consciously or intuitively, good writers know all of this.

An effective narrative works its magic, in part, by taking advantage of these, and other, predictable habits of thought. Red herrings, for example, are a type of anchor that set false expectations — and can make twists seem more surprising.

A major part of the pleasure of plot twists, too, comes not from the shock of surprise, but from looking back at the early bits of the narrative in light of the twist. The most satisfying surprises get their power from giving us a fresh, better way of making sense of the material that came before. This is another opportunity for stories to turn the curse of knowledge to their advantage.

Remember that once we know the answer to a puzzle, its clues can seem more transparent than they really were. When we revisit early parts of the story in light of that knowledge, well-constructed clues take on new, satisfying significance.

Consider “The Sixth Sense.” After unleashing its big plot twist — that Bruce Willis’ character has, all along, been one of the “dead people” that only the child protagonist can see — it presents a flash reprisal of scenes that make new sense in light of the surprise. We now see, for instance, that his wife (in fact, his widow) did not snatch up the check at a restaurant before he could take it out of pique. Instead it was because, as far as she knew, she was dining alone.

Even years after the film’s release, viewers take pleasure in this twist, savoring the degree to which it should be “obvious if you pay attention” to earlier parts the film.

The pluses and minuses of the spoiler

At the same time, studies show that even when people are certain of an outcome, they reliably experience suspense, surprise and emotion. Action sequences are still heart-pounding; jokes are still funny; and poignant moments can still make us cry.

As UC San Diego researchers Jonathan Levitt and Nicholas Christenfeld have recently demonstrated, spoilers don’t spoil. In many cases, spoilers actively enhance enjoyment.

In fact, when a major turn in a narrative is truly unanticipated, it can have a catastrophic effect on enjoyment — as many outraged “Infinity War” viewers can testify.

If you know the twist beforehand, the curse of knowledge has more time to work its magic. Early elements of the story will seem to presage the ending more clearly when you know what that ending is. This can make the work as a whole feel more coherent, unified and satisfying.

Of course, anticipation is a delicious pleasure in its own right. Learning plot twists ahead of time can reduce that excitement, even if the foreknowledge doesn’t ruin your enjoyment of the story itself.

Marketing experts know that what spoilers do spoil is the urgency of consumers’ desire to watch or read a story. People can even find themselves so sapped of interest and anticipation that they stay home, robbing themselves of the pleasure they would have had if they’d simply never learned of the outcome.

Vera Tobin, Assistant Professor of Cognitive Science, Case Western Reserve University

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

An empire of nothing at all?

AP

This piece originally appeared on TomDispatch.

Editor's Note: This essay is the introduction to Tom Engelhardt’s new book, "A Nation Unmade by War," a Dispatch Book published by Haymarket Books.

As I was putting the finishing touches on my new book, the Costs of War Project at Brown University’s Watson Institute published an estimate of the taxpayer dollars that will have gone into America’s war on terror from September 12, 2001, through fiscal year 2018. That figure: a cool $5.6 trillion (including the future costs of caring for our war vets). On average, that’s at least $23,386 per taxpayer.

Keep in mind that such figures, however eye-popping, are only the dollar costs of our wars. They don’t, for instance, include the psychic costs to the Americans mangled in one way or another in those never-ending conflicts. They don’t include the costs to this country’s infrastructure, which has been crumbling while taxpayer dollars flow copiously and in a remarkably -- in these years, almost uniquely — bipartisan fashion into what’s still laughably called “national security.” That’s not, of course, what would make most of us more secure, but what would make them — the denizens of the national security state -- ever more secure in Washington and elsewhere. We’re talking about the Pentagon, the Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. nuclear complex, and the rest of that state-within-a-state, including its many intelligence agencies and the warrior corporations that have, by now, been fused into that vast and vastly profitable interlocking structure.

In reality, the costs of America’s wars, still spreading in the Trump era, are incalculable. Just look at photos of the cities of Ramadi or Mosul in Iraq, Raqqa or Aleppo in Syria, Sirte in Libya, or Marawi in the southern Philippines, all in ruins in the wake of the conflicts Washington set off in the post–9/11 years, and try to put a price on them. Those views of mile upon mile of rubble, often without a building still standing untouched, should take anyone’s breath away. Some of those cities may never be fully rebuilt.

And how could you even begin to put a dollars-and-cents value on the larger human costs of those wars: the hundreds of thousands of dead? The tens of millions of people displaced in their own countries or sent as refugees fleeing across any border in sight? How could you factor in the way those masses of uprooted peoples of the Greater Middle East and Africa are unsettling other parts of the planet? Their presence (or more accurately a growing fear of it) has, for instance, helped fuel an expanding set of right-wing “populist” movements that threaten to tear Europe apart. And who could forget the role that those refugees — or at least fantasy versions of them — played in Donald Trump’s full-throated, successful pitch for the presidency? What, in the end, might be the cost of that?

Opening the Gates of Hell

America’s never-ending twenty-first-century conflicts were triggered by the decision of George W. Bush and his top officials to instantly define their response to attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center by a tiny group of jihadis as a “war”; then to proclaim it nothing short of a “Global War on Terror”; and finally to invade and occupy first Afghanistan and then Iraq, with dreams of dominating the Greater Middle East — and ultimately the planet — as no other imperial power had ever done.

Their overwrought geopolitical fantasies and their sense that the U.S. military was a force capable of accomplishing anything they willed it to do launched a process that would cost this world of ours in ways that no one will ever be able to calculate. Who, for instance, could begin to put a price on the futures of the children whose lives, in the aftermath of those decisions, would be twisted and shrunk in ways frightening even to imagine? Who could tote up what it means for so many millions of this planet’s young to be deprived of homes, parents, educations — of anything, in fact, approximating the sort of stability that might lead to a future worth imagining?

Though few may remember it, I’ve never forgotten the 2002 warning issued by Amr Moussa, then head of the Arab League. An invasion of Iraq would, he predicted that September, “open the gates of hell.” Two years later, in the wake of the actual invasion and the U.S. occupation of that country, he altered his comment slightly. “The gates of hell,” he said, “are open in Iraq.”

His assessment has proven unbearably prescient — and one not only applicable to Iraq. Fourteen years after that invasion, we should all now be in some kind of mourning for a world that won’t ever be. It wasn’t just the US military that, in the spring of 2003, passed through those gates to hell. In our own way, we all did. Otherwise, Donald Trump wouldn’t have become president.

I don’t claim to be an expert on hell. I have no idea exactly what circle of it we’re now in, but I do know one thing: we are there.

The infrastructure of a Garrison State

If I could bring my parents back from the dead right now, I know that this country in its present state would boggle their minds. They wouldn’t recognize it. If I were to tell them, for instance, that just three — Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Warren Buffett — now possess as much wealth as the bottom half of the US population, of 160 million Americans, they would never believe me.

How, for instance, could I begin to explain to them the ways in which, in these years, money flowed ever upward into the pockets of the immensely wealthy and then down again into what became one-percent elections that would finally ensconce a billionaire and his family in the White House? How would I explain to them that, while leading congressional Democrats and Republicans couldn’t say often enough that this country was uniquely greater than any that ever existed, none of them could find the funds — some $5.6 trillion for starters — necessary for our roads, dams, bridges, tunnels, and other crucial infrastructure? This on a planet where what the news likes to call “extreme weather” is increasingly wreaking havocon that same infrastructure.

My parents wouldn’t have thought such things possible. Not in America. And somehow I’d have to explain to them that they had returned to a nation which, though few Americans realize it, has increasingly been unmade by war — by the conflicts Washington’s war on terror triggered that have now morphed into the wars of so many and have, in the process, changed us.

Such conflicts on the global frontiers have a tendency to come home in ways that can be hard to track or pin down. After all, unlike those cities in the Greater Middle East, ours aren’t yet in ruins -- though some of them may be heading in that direction, even if in slow motion. This country is, at least theoretically, still near the height of its imperial power, still the wealthiest nation on the planet. And yet it should be clear enough by now that we’ve crippled not just other nations but ourselves in ways that I — though I’ve tried over these years to absorb and record them as best I could — we can still barely see or grasp.

In my new book, "A Nation Unmade by War," the focus is on a country increasingly unsettled and transformed by spreading wars to which most of its citizens were, at best, only half paying attention. Certainly, Trump’s election was a sign of how an American sense of decline had already come home to roost in the era of the rise of the national security state (and little else).

Though it’s not something normally said here, to my mind President Trump should be considered part of the costs of those wars come home. Without the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq and what followed, I doubt he would have been imaginable as anything but the host of a reality TV show or the owner of a series of failed casinos. Nor would the garrison-state version of Washington he now occupies be conceivable, nor the generals of our disastrous wars whom he’s surrounded himself with, nor the growth of a surveillance state that would have staggered George Orwell.

The makings of a blowback machine

It took Donald — give him credit where it’s due — to make us begin to grasp that we were living in a different and devolving world. And none of this would have been imaginable if, in the aftermath of 9/11, George W. Bush, Dick Cheney & Co. hadn’t felt the urge to launch the wars that led us through those gates of hell. Their soaring geopolitical dreams of global domination proved to be nightmares of the first order. They imagined a planet unlike any in the previous half millennium of imperial history, in which a single power would basically dominate everything until the end of time. They imagined, that is, the sort of world that, in Hollywood, had been associated only with the most malign of evil characters.

And here was the result of their conceptual overreach: never, it could be argued, has a great power still in its imperial prime proven quite so incapable of applying its military and political might in a way that would advance its aims. It’s a strange fact of this century that the U.S. military has been deployed across vast swaths of the planet and somehow, again and again, has found itself overmatched by underwhelming enemy forces and incapable of producing any results other than destruction and further fragmentation. And all of this occurred at the moment when the planet most needed a new kind of knitting together, at the moment when humanity’s future was at stake in ways previously unimaginable, thanks to its still-increasing use of fossil fuels.

In the end, the last empire may prove to be an empire of nothing at all — a grim possibility which has been a focus of TomDispatch, the website I’ve run since November 2002. Of course, when you write pieces every couple of weeks for years on end, it would be surprising if you didn’t repeat yourself. The real repetitiousness, however, wasn’t at TomDispatch. It was in Washington. The only thing our leaders and generals have seemed capable of doing, starting from the day after the 9/11 attacks, is more or less the same thing with the same dismal results, again and again.

The U.S. military and the national security state that those wars emboldened have become, in — and with a bow to the late Chalmers Johnson (a TomDispatch stalwart and a man who knew the gates of hell when he saw them) — a staggeringly well-funded blowback machine. In all these years, while three administrations pursued the spreading war on terror, America’s conflicts in distant lands were largely afterthoughts to its citizenry. Despite the largest demonstrations in history aimed at stopping a war before it began, once the invasion of Iraq occurred, the protests died out and, ever since, Americans have generally ignored their country’s wars, even as the blowback began. Someday, they will have no choice but to pay attention.

Tom Engelhardt is a co-founder of the American Empire Project and the author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture. He is a fellow of the Nation Institute and runs TomDispatch.com. His sixth and latest book, just published, is A Nation Unmade by War (Dispatch Books).

To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com here.

Copyright 2018 Tom Engelhardt.

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.