Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 66

May 23, 2018

Wealthy families invest more in sons

AP/Cheryl Senter

This article was originally published by Scientific American.

Parents tend to favor children of one gender in certain situations — or so evolutionary biologists tell us. A new study used data on colored backpack sales to show that parental wealth may influence spending on sons versus daughters.

In 1973 biologist Robert Trivers and computer scientist Dan Willard published a paper suggesting that parents invest more resources, such as food and effort, in male offspring when times are good and in female offspring when times are bad. According to the Trivers-Willard hypothesis, a son given lots of resources can outcompete others for mates — but when parents have few resources, they are more inclined to invest them in daughters, who generally find it easier to attract reproductive partners. Trivers and Willard further posited that parental circumstances could even influence the likelihood of having a boy or girl, a concept widely supported by research across vertebrate species.

Studying parental investment after birth is difficult, however, and has produced conflicting results. The new study looked for a metric of such investment that met several criteria: it should be immune to inherent sex differences in the need for resources; it should measure investment rather than outcomes; and it should be objective rather than rely on self-reporting.

Study author Shige Song, a sociologist at Queens College, City University of New York, examined spending on pink and blue backpacks purchased in China in 2015 from a large retailer, JD.com. He narrowed the data to about 5,000 bags: blue backpacks bought by households known to have at least one boy and pink ones bought by households known to have at least one girl. The results showed that wealthier families spent more on blue versus pink backpacks — suggesting greater investment in sons. Poorer families spent more on pink packs than blue ones. The findings were published online in February in Evolution and Human Behavior.

Song’s evidence for the Trivers-Willard hypothesis is “indirect” but “pretty convincing,” says Rosemary Hopcroft, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, who was not involved in the new study. Hopcroft reported in 2016 that U.S. fathers with prestigious occupations were more likely to send their sons to private school than their daughters, whereas fathers with lower-status jobs more often enrolled their female children. Although the study does not prove the families were buying the blue backpacks for boys and pink ones for girls, Hopcroft notes that “it’s a clever and interesting paper, and it’s a very novel use of big data.”

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

8 dinners for when cooking just isn’t gonna happen

James Ransom/Food52

This story first appeared on Food 52, an online community that gives you everything you need for a happier kitchen and home – that means tested recipes, a shop full of beautiful products, a cooking hotline, and everything in between!

There are days where I get home, collapse on my couch, and moving seems impossible. I don’t want to touch a stove or oven, and even something as simple as scrambled eggs or pesto pasta feels out of reach. It’s a time for salads and sandwiches.

I’m not entirely sure if making a salad or sandwich constitutes cooking — okay, components of it can — but I’m certain they’re more satisfying than a bowl of cereal. From slice-and-serve caprese to dressed-up cans of chickpeas, there are dinners that don’t require that whole cooking thing. Here, I’ve collected eight of my favorites. After my night off, I’ll be ready to cook again.

(Credit: Photo by James Ransom/Food52)

This amped-up avocado toast has it all: crunchy cucumbers and tomatillo slices, creamy rounds of fresh mozzarella, and fluffy tufts of sprouts. You don’t have to Instagram it . . . but it is practically begging for a close-up.

(Credit: Food52)

You might want to wait until we hit prime tomato season, but this Italian classic should definitely be in your I’m-not-cooking weeknight rotation.

Pick up a rotisserie chicken on your way home and you’ve got the beginnings of a creamy, green-y chicken salad. You can sandwich it between slices of toast, or just eat it straight out of the bowl, like I do.

(Credit: Photo by James Ransom/Food52)

Finally, a recipe that rewards impatience. Unripe peaches get a cayenne kick before piling onto blue cheesy toast. Dinner is served.

(Credit: Photo by James Ransom/Food52)

The best part of this dish is that it comes together in minutes. The second best part? Its punchy flavor.

(Credit: Photo by James Ransom/Food52)

Pile this bold, beautiful slaw on your plate. Cold soba or leftover steak are more than welcome to join the party.

(Credit: Photo by Bobbi Lin/Food52)

Mash up canned chickpeas with mayo and a punch of curry and turmeric for a tasty dinner tonight and a wallet-friendly lunch tomorrow.

(Credit: Photo by Ty Mecham/Food52)

All of the super-smart salad tricks Genius creator Kristen Miglore’s learned in one recipe. My favorite ingredient is the crispy, crunchy raw(!) beets.

What do you eat when you don’t feel like cooking? Are you a cereal-for-dinner fan?

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

What will we eat in 2050? California farmers are placing bets

AP Photo/Nick Wagner

This post originally appeared on Grist.

Chris Sayer pushed his way through avocado branches and grasped a denuded limb. It was stained black, as if someone had ladled tar over its bark. In February, the temperature had dropped below freezing for three hours, killing the limb. The thick leaves had shriveled and fallen away, exposing the green avocados, which then burned in the sun. Sayer estimated he’d lost one out of every 20 avocados on his farm in Ventura, just 50 miles north of Los Angeles, but he counts himself lucky.

“If that freeze was one degree colder, or one hour longer, we would have had major damage,” he said.

Avocado trees start to die when the temperature falls below 28 degrees or rises above 100 degrees. If the weather turns cold and clammy during the short period in the spring when the flowers bloom, bees won’t take to the air and fruits won’t develop. The trees also die if water runs dry, or if too many salts accumulate in the soil, or if a new pest starts chewing on its leaves. “All of which is quite possible in the next few decades, as the climate shifts,” Sayer said.

The weather had been strange lately, Sayer told me. In the past year, Californians have lived through a historic drought, a massive wildfire that blotted out the sun, and a strangely warm winter followed by that unseasonable freeze. When I visited in April, his lemon trees were already loaded with ripe fruit — that usually doesn’t happen until June. “Things are screwy,” Sayer said.

From the vineyards of the north coast to the orange groves of Southern California, farmers like Sayer have been reeling from the weird weather.

“We are already suffering the effects of climate change,” said Russ Lester, who grows walnuts at Dixon Ridge Farms, east of Sacramento. “I can look out my window and see trees that don’t have a leaf on them and others that are completely leafed out.

“The trees are totally confused.”

It might feel like we’re peering into the distant future when we hear that by 2050, temperatures may very well climb 4 degrees, seas could rise a foot, and droughts and floods will become more common. But for farmers planting trees they hope will bear fruit 25 years from now, that seemingly distant future has to be reckoned with now.

A lot of the country’s tree crops grow in California, which produces two-thirds of the fruits and nuts for the United States. The same is true of grape vines, which bear abundant fruit for about 25 years (they slow down after that, but can keep going for hundreds of years). It’s in large part because so many farmers are making these long-term gambles on orchard crops that a recent scientific paper noted: “Agricultural production in California is highly sensitive to climate change.”

Jay Famiglietti, the senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, goes even further: “It’s a virtual certainty that California will get drier. I don’t think it’s a climate that’s conducive to orchard crops anymore.”

In other words, for anyone trying to make money off long-lived crops, climate change is already here. And yet new saplings are pushing out of the ground all over the state.

* * *

If these farmers were planting an annual crop, like cilantro, they’d be making a bet on the weather for the next 45 days. But they’re planting trees, which means making a bet on the next 40 years.

After years of putting it off, Sayer is about to place such a four-decade bet by planting a bunch of new avocado trees. There’s no way Sayer can foresee oncoming climate disaster, if that’s what’s hurtling toward the land his family has worked for the past 130 years in Ventura. He can see just a little bit of what might be coming — as if he’s straining to glimpse signs of danger while blinkered. When I asked him how it felt, he said: “Like I’m about to cross a very busy road with my hood pulled over my head.”

When Katherine Jarvis-Shean was a doctoral candidate researching the decline of cold winters a few years back, she thought more farmers should be freaking out. “I used to think, ‘Why aren’t you guys more worried about this? It’s going to be the end of the world.’”

After all, many fruit and nut trees require a good winter chill to bear fruit. But after spending a few years as an extension agent for the University of California — working directly with farmers and translating science into techniques they can apply on the land — she understands better. It comes down to this: Farmers have a ton of concerns, and the climate is just one of them.

“If you decide what to plant based on climate, but then can’t make the lease payment, that’s not sustainable,” Jarvis-Shean said.

If you are worried about water running out in 15 years, you might think it’s a good idea to cut down half the state’s almond groves — but if those almond trees are still putting money in your pockets, that wouldn’t make sense until the killer drought hits. That’s the crux of the matter for Sayer, and other farmers I interviewed. They’re concerned about the changing climate, but they always come up with ingenious plans to adapt to bad weather. It’s much harder for them to adapt to an overdrawn bank account.

Sayer grows mostly lemons right now, but they’re not long for this world. “You can see these lemon trees are getting a little rangy looking,” Sayer said, gesturing toward a leafless branch. “This is going to be their last harvest, then they’ve got a date with the chipper.”

Sayer knows lemons. He knows how to coddle them in old age, how to nudge them to produce more, how to keep them alive when rains fail, how to protect them from aphids and snails and scale insects and the nematodes in the ground. But this land has provided a home to a citrus orchard for 70 years, and each year more pests accumulate to suck the life from the trees. So Sayer needs to move on from lemons, and he’s settled on avocados.

From a climate perspective, the leather-skinned fruit are a risky choice. Avocado trees like their surroundings not too hot and not too cold, and they always need water. One studyestimated that climate change would hurt California avocado trees so much that the state’s production could be cut in half by 2050.

As the sun burned off the marine layer of clouds over the orchard, Sayer patiently laid out the reasoning that led him to plant avocado trees. He explained that climate poses risks that are easy for outsiders to see — when you’re reading about historic droughts in the newspaper and driving past acres of withered crops, it seems crazy to plant orchards. But farmers often have to contend with other risks that outweigh the danger of bad weather. Sayers puts them into three categories: climate risk, market risk, and execution risk.

If he were only worried about climate risk, Sayer said, he’d plant prickly pear. “They would grow in any post-apocalyptic hellscape you could imagine,” he said. But who would buy them? Most Americans don’t put prickly pear on their shopping lists. So there’s a huge market risk.

Then there’s execution risk: the chance that Sayer screws things up. If he didn’t have to worry about that, Sayer might follow his neighbor’s lead and start growing annual crops. He pointed across the road from his farm, where orchards once stood, at a flat expanse of strawberries dotted with hustling pickers. There’s always an appetite for strawberries so they pose a low market risk. And because strawberries get planted every year, they’re not such a big gamble on the changing climate. If a freak storm kills everything growing in Ventura, for instance, Sayer’s neighbor would lose that year’s strawberry crop while Sayer would lose a 30-year avocado investment.

But the execution risk of switching to strawberries — figuring out how to grow them, buying the right equipment, and learning how to sell them — is too high for him. “We’re talking about years of learning,” Sayer said. “It would be like me deciding to go back to college to study medicine.” He’s 52, and not prepared to start fresh.

Sayer has one other option that would eliminate all the climate, market, and execution risks: Pave his farmland and build houses. When I visited in April, workers were constructing apartments on what used to be farmland at the end of his street. If more farmers start taking climate risks seriously, a surge of subdivisions could start sprawling across some of the most fertile farmland on the planet. But the thought of that saddens Sayer. He wants to farm.

After weighing all those risks, he decided to bet the farm on avocados. These trees are no climate savior — far from it. But Sayer been experimenting with them for decades and understands how they work. He knows he can sell avocados, because he’s tapped into a network that reserves spots for the fruit in every grocery store, and turns sunburned avocados into frozen guacamole. Also, you might have noticed the market is strong: Americans are chowing down so much avocado tonnage in new, creative ways — smoothies, toast, ice cream, you name it — that consumption has increased sevenfold since 2000.

* * *

Orchards can endure weird weather brought on by climate change, but if they don’t get any water, the trees will die. In the past, California farmers have always survived droughts by sticking deeper and deeper straws into the ground to suck up groundwater. But since 2014, the state has had a law against depleting aquifers, and farmers soon won’t be able to take out more water than goes in.

That policy alarms growers, especially since they can no longer depend on snow in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Mountains hold water — in the form of glaciers — through the colder months, then release it during the warmer months. But as the climate heats up, more of the precipitation that fell in California as snow will turn to rain. That means more floods in winter and more droughts in summer.

To adapt to this boom-and-bust cycle, a few farmers around California are letting swollen rivers spill into their orchards. If carried out on a large scale, this would slow down rushing flood waters and let them percolate into aquifers.

After four years of experimentation in almond groves, scientists have found that this inundation hasn’t hurt the trees. They’ve also identified nearly 700,000 acres under almond trees suitable for recharging groundwater, said Richard Waycott, president of the Almond Board of California. At the same time, growers continue to use less freshwater for irrigation and draw more water recycled from city drainpipes.

In another example of climate adaptation, farmers are developing a kind of hyper-local climate engineering, spraying clay dust over their trees to create shade and cool them down in unseasonably hot weather, according to David Zilberman, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley. Elsewhere, scientists have planted a pistachio orchard where no self-respecting pistachio farmer would ever put a tree: in the middle of the Southern California desert near Coachella.

Most pistachio trees grow 200 miles north, where colder winters allow them to settle into their natural cycles. But in a few decades, that traditional pistachio land could have the climate of Coachella. It’s a type of time travel; the idea is to find a version of the future that already exists.

The pistachio trees aren’t at all happy in the desert: “It’s just terrible out there,” said Craig Kallsen, another extension agent for the University of California. “It looked like someone had irradiated the place with toxic chemicals.”

All the same, a few pistachio trees are beginning to produce leaves. By growing this orchard in this analogue of the climate future, researchers like Kallsen can see which varieties stand up to heat, and then zero in on the genes that allow those trees to adapt. Using those genes, researchers hope to breed trees that can thrive in a hotter, drier world.

Sayer is also adapting by growing different varieties of avocados, but the most visible climate adaptation in the orchard was the knee-high carpet of grasses and turnip stems we waded through as we made our way among the trees.

“Back in the 1970s, bare dirt between the rows was considered clean and tidy,” Sayer said. “If you had a blade of grass sticking out, oh man, that wasn’t good.”

Letting plants grow beneath the trees seemed like a squalid, lazy, weed-spreading hazard. When he and his father first began planting between the rows in 2005, it felt taboo. Other farmers would sidle up to them at the coffee shop and ask in an undertone, “What’s going on with your orchard? Is that a cover crop?”

A cover crop protects the soil from heavy rains and helps turn it into a habitat for worms, beetles, and thousands of microbes. As we walked through the dappled sunlight, the ground beneath my feet was yielding like a giant sponge.

Sayer has calculated that, since first planting the cover crop, his lemon orchard can absorb 2.5 million gallons more water in a downpour. “Since every scenario I’ve seen involves water stress, better soil is going to put us in a better position, because it holds and absorbs more rain,” he said.

Lester, the Sacramento-area walnut grower, also plants cover crops. And he has an audacious justification for planting new trees: He hopes to reverse climate change.

Cover crops pull carbon from the air into the soil and — if we can figure it out — all of agriculture could become a giant carbon-dioxide sponge. Lester powers his operation with solar panels and a walnut-shell burning furnace (releasing carbon his walnut trees recently sucked out of the air), making his farm carbon negative.

“Call me optimistic, but I believe if all farmers adopted healthy soils technology, agriculture can play a huge role in stopping, slowing down, maybe even reversing climate change,” Lester said.

Not all farmers are as scientifically literate as Lester or Sayer; many shrug off climate change as just another shift in the weather. But even the ones who readily accept the science of climate change continue to plant trees. Perhaps they are overly optimistic. Perhaps they are just human: It’s not in our nature to ignore threats right in front of our face so we can focus on those in the seemingly far-off future.

After I’d spent the day with Sayer, his decision to plant more avocados made sense: It’s the choice that allows him to keep farming. He’s making preparations based on the best climate projections he can get, while also setting himself up to react to the unexpected. He can see a path to profitability, though he allows that his vision into the future — in terms of both climate and weather forecasting — is severely restricted.

If you recall, he likened planting a new round of avocado trees to crossing a busy road with a hood over his head. There was a second part to that analogy: “At least I know which way to look for the oncoming traffic.”

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

It’s time to choose between guns and kids

Getty/Scott Olson

Forget “this is not normal.” This is what the country has decided to accept as the price for the “right” to privately own more firearms than any nation on earth. Face it: many of our fellow citizens would rather own inert, deadly guns than bring up living, breathing children.

Our fellow citizens elected the demonstrably corrupt and traitorous occupant of the White House and our corrupt, lily-livered Congress. We've done this to ourselves.

Look in the mirror. This is who we are. We now face the question of who we want to be.

It shouldn’t have taken us this long. We shouldn’t have waited until the nearly back-to-back shootings at Parkland and Santa Fe this year, until 27 more lost their lives, until 27 more were wounded. But here we are.

It’s not like we haven’t been here before, because we have. Twenty years ago, there was the March 1998 school shooting in Jonesboro, Arkansas, when two boys aged 11 and 13 fatally shot four students and a teacher and wounded ten more. One year later, in April of 1999, two students, aged 17 and 18, walked into their high school in Columbine, Colorado and unleashed a fusillade, killing twelve students and one teacher and wounding 21 more.

There have been 25 more school shootings at elementary and high schools since Columbine, including the killings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, when a single shooter, aged 20, killed 20 children and six school staff members. More than 150 children have been killed by firearms since 1999 in American schools, according to FBI statistics.

All the killings share two things: they were committed by boys or young men, and they were committed with firearms. The weapons used in these school shootings ranged from 9mm pistols to double-barrel shotguns to AR-15 military style semi-automatic rifles. Many of the shooters used high capacity magazines. The shooters at Columbine used several different firearms with 13 magazines holding 10 rounds, and three more magazines holding 28, 32, and 52 rounds. Between them, they discharged two shotguns 37 times, and two more weapons 151 times. The shooter at Sandy Hook used one shotgun, one AR-15 style rifle and two handguns. He used 10 rifle magazines carrying 30 rounds each and 12 pistol magazines carrying 30 rounds each.

The number of firearms and the quantity of ammunition used by these school shooters was comparable to and even exceeded what is carried by infantry soldiers in combat. Some of the weapons and ammunition used to kill school children were acquired at gun stores and gun shows. Some were taken from the firearms collections of adult parents or grandparents of the shooters. In the case of the killers at Jonesboro, they took more than 1,000 rounds of ammunition from the top of a grandfather’s refrigerator. One thousands rounds of ammunition stored in a suburban kitchen! All the firearms and ammunition used in school shootings were readily available to the shooters. All the firearms were legal in the states where the shootings took place. In most states, it would have been harder for the killers to obtain a switchblade knife than a firearm, because switchblades were illegal.

While the arsenals used by school shooters are comparable to the weapons carried by soldiers in combat, the way that the military controls its deadly weapons is remarkably different than what is required by most states in this country. When weapons of war are not being used in combat or training in the military, they are required to be kept under lock and key along with their ammunition and accounted for daily. Most states do not require that firearms or ammunition be locked up by gun owners. Neither Florida or Texas requires gun owners to lock up their weapons. Leaving firearms unprotected around the house can result in the accidental deaths of children. About 1,300 children were killed in accidents involving firearms each year between 2012 and 2014, according to a study published in the journal Pediatrics in 2017. More children have been killed in school shootings in the United States this year than have been killed in the military, either accidentally or in combat.

No other developed nation in the world has comparable numbers of children killed by school shootings or accidentally from firearms. But then no other country has laws that make firearms and ammunition as easily available as they are in the United States.

It’s long past time for parents of school children and every other American to stand up and demand the passage of sane gun laws. At a minimum, background check loopholes should be closed. There should be a requirement that guns be locked up in the house when not in use. Gun owners should be required to be licensed, and they should be required to carry liability insurance on every firearm they own, equivalent to the liability insurance required by every state on motor vehicles. There should be even stricter licensing requirements to open carry or conceal carry firearms. All gun owners should be required to take firearm safety courses as a requirement to be licensed. Renewing firearms licenses should be required at least as often as states require the renewal of drivers’ licenses.

There should be laws holding parents criminally responsible for shootings committed by minor children with firearms owned by the parents. States should be required to create a fund that will pay for the hospital costs of anyone wounded in a school shooting or in a mass shooting. Gun manufacturers should have to pay into that fund, and the balance can be secured by levying a tax on gun sales. Individuals who are wounded should not have to bear the financial burden resulting from lax gun laws.

Teachers showed us how effectively pressure can be brought on state legislatures and governors when they shut down the entire school systems in multiple states seeking pay raises. Parents of school children can force states to pass sane gun laws if they get together and pull their kids out of schools until their demands are met. Schools provide the atmosphere for a perfect political storm. Schools cross all lines of race, class, and political party. Everyone wants their kids educated. Shutting down the education systems of entire states would eclipse even the NRA in the power it would have to put pressure on state legislatures and governors.

People who see their guns as a part of their identity, or as the governor of Texas claimed last week, believe that “guns are in our DNA,” face a stark choice. Do they want their kids to be safe, or do they want unfettered access to weapons designed to maim and kill?

The rest of us need to decide what kind of country we want. How do you choose? Guns or kids?

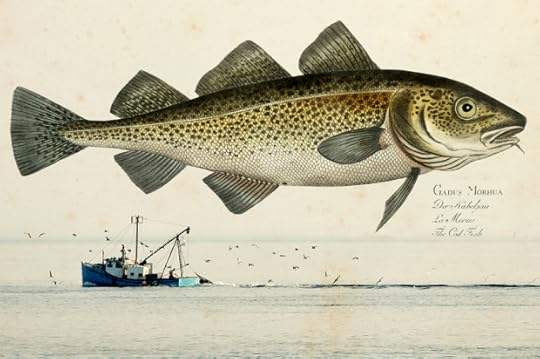

Tongue and cheek: Eating the once-discarded parts of Newfoundland’s number one fish

Getty/Shutterstock

A grizzled man in full fishing gear waggled the shiny, dead cod in his hands. We stood in a circle around him, a group of Americans, Canadians, Brazilians, and New Zealanders nervously awaiting the next step in this unique ceremony. Soon, the floppy fish would approach each of our faces, and we’d have to kiss it. All of us had paid $20 for the opportunity.

The cost also covered a cube of Spam, a shot of Screech (rum), and a paper certificate claiming the status of “Honorary Newfoundlander,” issued by the Newfoundland Labrador Liquor Corporation. Mine is hanging in my kitchen (I kissed the cod).

This tourist-aimed process is known as getting “screeched in,” after the potent Newfoundland rum you have to drink during the ceremony. You can get “screeched in” on George Street, which consists of bars stacked atop bars, in downtown St. John’s, Newfoundland’s capital city. I became an honorary Newfoundlander on the second floor of Christian’s, which has been trolling foreigners (or “come from aways,” like the name of the popular Broadway play that takes place in the province) for about 18 years by having them kiss dead cod.

“Have you ever done this?” I remember asking my partner and his two friends, all Newfoundlanders, before I joined the group of “screechers” in summer 2016. They laughed. “Nah, by, of course not.” No self-respecting Newfoundlander would pay money to kiss the type of fish that they’d been eating for breakfast, lunch, and dinner their whole lives. But as someone dating a Newfoundlander who’d traveled to the small island off the east coast of Canada for the first time, I had no choice but to get so acquainted with its staple food.

* * *

“Fish is cod in Newfoundland,” said Jeremy Charles, head chef at St. John’s restaurant Raymonds, a member of the Diner’s Club World’s 50 Best Restaurants, on a recent episode of “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown.” Although Anthony Bourdain is my pet peeve, I had to watch him experience the cuisine of an island I’d come to love over the past two years (and whose name Bourdain failed to learn to pronounce over the course of his visit — it rhymes with “understand”).

While Bourdain chowed down on gourmet fish and brewis (pronounced “brews”), a salty, hearty meal featuring flaky cod, potatoes, hardtack (bread you have to soak in water overnight before you can bite it), and scrunchions (cubes of pork fat fried in pork fat — indulgence at its best), he skimmed over some of the best parts of the cod. Namely, their tongues and cheeks. Lightly battered and fried in pork fat, both are a delight.

But first, some background on Newfoundland’s fraught history with cod: As early as the 15th Century, Newfoundland’s teeming cod population attracted fishermen from across the globe, including France, Spain, England, and Portugal. You can still trace back certain Newfoundlanders’ family names to fishermen who settled there in the early 17th Century, according to “Fishery to Colony: A Newfoundland Watershed, 1793-1815,” by Shannon Ryan. Cod fishing contributed to a steady increase in Newfoundland’s population over the 19th Century, and by the 20th Century, some 30,000 Newfoundlanders were making a living off cod, even though fleets from abroad harvested the majority each year. Overfishing was inevitable.

The industry still proved extremely profitable for Newfoundlanders in the 1900s, even as the number of fish began to dwindle. In the 1970s, the International Commission for the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries, a management body for extranational fishing, first implemented “catch quotas,” limiting the number of Northern cod fishermen could take home. Fishermen continued to fill those quotas with ease, misleading authorities into believing that hefty catches meant plentiful cod. In reality cod numbers were going down — the fishermen’s technology and gear had just gotten better and allowed them to work more efficiently. “A 1989 internal review revealed DFO [the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans] had overestimated cod populations by as much as 100 percent during the decade leading up to the moratorium,” according to the Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Website.

The infamous Newfoundland cod fishing moratorium went into effect three years later. The industry closed down “indefinitely,” leaving tens of thousands of hardworking Newfoundlanders without a job and on “pogey” (Canadian slang for unemployment insurance).

The movie “The Grand Seduction” captures the moratorium’s impact on the island’s many small, rural communities well. In it, Brendan Gleeson (“In Bruges,” “The Guard”) plays a Newfoundlander (alongside several actual Newfoundlander actors) in the post-moratorium generation who lives in a 120-person community, where it seems like all 120 locals rely on pogey for a living. They feel deflated compared to their parents’ generation, who worked long hours on the boats and docks and came home satisfied, with full pockets and a sense of purpose. In the movie, this generation’s contentment is exemplified in the collective sigh heard throughout the town as each couple, at the end of the long workday, experiences post-coital bliss.

My partner, Ryan, pale with curly hair and tattoos featuring St. John’s harbor on his leg and an unspecified fish on his arm, grew up closer to the capital city and therefore didn’t quite have “The Grand Seduction” experience. However, his grandfather tangentially benefited from the cod fishing industry in Bay Roberts, where he ran a general store that catered to workers from the nearby fish plant and people who stopped in from passing boats. Ryan ate cod “every other day growing up . . . Anytime Sobeys [a Canadian grocery store chain] had cod on up there for half off a pound, my grandmother would pick it up, throw it down in the freezer, and you’d be eating cod for two weeks.”

His grandmother would prepare the cod by thoroughly boiling it, until it was “flaky and soft and tender but bland as all hell,” a recipe that called for liberal salting. Cod loves salt like meat loves salt, and salt had been employed to preserve the caught fish for centuries, making salt fish a common addition to any meal. To make salt fish palatable, you have to soak it, usually overnight, after which it becomes a delectable component of the aforementioned fish and brewis.

As for cod tongues (and cheeks), the best recipes are simple. Newfoundlanders learned how to perfect them because they come from the least desirable part of a cod—their heads. Since the rest of the world imported Atlantic cod for the abundant meat in their two to three-foot-long bodies, Newfoundlanders were left with a lot of extra heads, deemed worthless by those who didn’t know to cut out the tongues and dig beneath the cheek bones for tender meat.

You can treat cod tongues and cheeks pretty much the same when you’re cooking them. First, mix up some flour, salt, and pepper. You can do this on a kitchen countertop or in a plastic bag sitting atop a pile of snow in the woods. Meanwhile, fry up some cubes of pork fat in pork fat to make scrunchions (a sinfully addictive food item hard to encounter outside of Newfoundland — perhaps fried pancetta is the closest I’ve gotten in the States).

Then it’s time to throw the tongue and cheeks on your frying pan. Keep them there until one side turns golden brown, then flip to achieve the same effect on the other. The resulting meal is one of perfect texture variation, a crisp crunch covering up soft, flavorful meat that comes apart easily in your mouth, topped off with the juicy, salt burst of scrunchions.

“Everyone likes to compare food to chicken,” Ryan told me. “Think of cod tongue as the dark meat of the chicken…oily with flavor, it’s full-bodied like chicken legs and thighs.”

In spite of their roots as the throwaway parts of the cod, cod tongues have become a delicacy in the eyes of visitors to the island. I had my first fried cod tongue at St. John’s Fish Exchange, the kind of restaurant to which you’d wear a collared shirt, overlooking the city’s harbor. Pan-fried with scrunchions, the cod tongues exemplified a classic, poor man’s recipe gone haute, a once cast-aside organ playing dress-up. I could not complain.

“Cod tongues and other Newfoundland cuisine is a good analogy for what it feels like to be a Newfoundlander now,” Ryan mused, watching flaky salt cod sizzle alongside softened, doughy hard tack, golden brown potatoes, and crackling scrunchions in a pan on our stove. You used to be able to go down to the fishery and pay a dollar a pound to cut the meat out of cods’ heads to fry up at home. Now, you can pay $15 for a few tongues at St. John’s Fish Exchange. “It’s bizarre growing up in a place no one knew existed that is now going through a renaissance of being cool and interesting.”

The U.S. is going through a sort of discovery period with Newfoundland. Besides Bourdain, VICE made a trip to the island with its food show, “Munchies,” and David Letterman reflected on his post-“retirement” trip to Fogo Island, a newly trending vacation spot off Newfoundland’s coast, with Barack Obama on the first episode of the former’s new Netflix show.

All this newfound interest happens to correspond to a resurgence of cod in the region. It’s been 26 years since the moratorium, and the population has been going up by about 30 percent year over year for the last decade, according to Canada’s National Post as of March 2017. The cod population is still nowhere near the size of its heyday, but it is growing — just in time for foreigners to start developing a taste for their tongues.

* * *

The “screeching in” ceremony ends with a call and response. After you’ve had your rum and kissed your cod, the man in the fishing gear will ask you, “Is you a Newfoundlander?”

Top Trending

Check out the top news stories here!

Harvey Weinstein is being investigated by federal prosecutors

Getty/Alexander Koerner

Harvey Weinstein is being investigated by federal prosecutors in Manhattan for sex-abuse allegations, the Wall Street Journal reported. According to people familiar with the investigation, "The U.S. attorney’s office for the Southern District of New York is examining whether Mr. Weinstein lured or induced any women to travel across state lines for the purpose of committing a sex crime," the Wall Street Journal said. If true, the claims could result in federal charges for Weinstein.

This federal investigation adds to the local inquiry by the New York Police Department, which has been investigating Weinstein for claims of sexual harassment and assault since October 2017. Two investigations into sexual assault accusations against Weinstein were filed in Los Angeles in January. And a lawsuit was filed against The Weinstein Co. by the New York Attorney General claiming Weinstein's former production company violated New York civil rights, human rights, and business laws.

The disgraced Hollywood producer has been accused by dozens of women of sexual harassment, sexual abuse, sexual assault and rape. Weinstein's lawyer told the Journal that he met with federal prosecutors in Manhattan "in an attempt to dissuade them from proceeding." He added, "Mr. Weinstein has always maintained that he has never engaged in nonconsensual sexual acts."

Manhattan federal prosecutors were already investigating alleged fraud related to financial transactions orchestrated by Weinstein for a charity auction, the Journal reported, but the expansion to include possible sex crimes is a new development.

For the local investigation, there has been some tension between police and the Manhattan district attorney's office for what some officials see as the office dragging its feet.

"How much longer can they let it linger?" Michael Bock told the Journal, who investigated Weinstein when he was a supervisor for the New York Police Department’s Special Victims Division before retiring last year. "We believe he should be arrested."

Further, two NYPD officials told the Journal that the NYPD is prepared to arrest Weinstein, and is just waiting for confirmation from Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. His office became notorious for deciding not to charge Weinstein for a sexual assault charge in 2015. In March, Gov. Andrew Cuomo directed the New York attorney general to look into the way Vance's office handled the investigation.

A spokesperson for the district attorney's office said its current investigation into Weinstein is in "an advanced stage." The investigation by federal prosecutors is independent from the Manhattan district attorney's.

Since the New York Times and New Yorker exposés, which brought the accusations against Weinstein into the national spotlight, Weinstein has been expelled from both the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and his production company, which recently filed for bankruptcy.

Broadway director George C. Wolfe on Eugene O’Neill and the strange music of “The Iceman Cometh”

Getty/Rob Kim

Five-time Tony Award winning playwright and director George C. Wolfe shares the story behind his sizzling new Broadway production of Eugene O'Neill's "The Iceman Cometh,” in which Academy Award winner Denzel Washington plays Hickey, the mysterious traveling salesman who drives a barroom full of drunks in 1912 New York into a dizzying downward spiral.

Wolfe's production has garnered eight Tony Award nominations, including one for Wolfe's direction and one for star Denzel Washington.

Wolfe stopped by Salon's studio recently to discuss the challenges of mounting a classic revival, O'Neill's career and style, the incantatory nature of the language in this play, and seeing Tony Kushner's groundbreaking "Angels in America," for which Wolfe won a directing Tony in 1993, be revived on Broadway as well. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve tackled a lot of different kinds of theatre and plays, classic, modern, contemporary. I know that you’ve directed Shakespeare. I imagined you’ve dealt with Ancient Greek drama, and created new plays. How much have you done of those sort of bedrock, big American plays? I was wondering if "Iceman" was a slight departure for you?

"Iceman" is a slight departure. I normally don’t like doing revivals because I figure . . . always when I do a play there’s got to be an equation of risks and potential failure. When you’re working on a new play, it’s like, how the hell do I do this, and do we have the time? All of these huge questions engage, hopefully, the smartest part of me. And then when you’re doing a revival, I went, well, somebody’s already solved it.

What do I have to offer for it? But then, at one point, Denzel was interested in coming back to Broadway, which he regularly does, which I’m really glad because he’s just a brilliant actor and it’s really nice that there’s a person who has an incredibly vibrant and vital film career who is dedicated and deeply invested in doing theatre. After series of conversations, he made a commitment to do "Iceman."

I got inside of it and I went, there is potential for failure all over the place. Let me jump on board. It was fascinating to me because I found myself inside of it by accident, in someway. I was going to like OK, I think I can be smart about this.

Then, as you get inside of it, you go, “Oh my God, his language is extraordinary. He writes this incredibly brilliant, what I call tribal speak of New York and it’s stunning.” When you read it, you don’t get it and then when you start to animate it, it’s extraordinary.

I ended up finding myself in love.

Watch the full conversation with George C. Wolfe

The five-time Tony winner on his revival of "The Iceman Cometh."

Talk about the character of Hickey, who Denzel Washington plays in this production. Who is he? Where does he come from? What does he mean in this show?

Well, Hickey is an incredibly dynamic, charismatic door to door salesman.

He’s stuck inside of this marriage where perfection and honesty and purity of thought is expected of him. He is not that, nor is anyone.

To escape that, every year he shows up for about a month and he gets clustered out of his mind for a month and then he leaves there and goes back to his life and to his marriage and to his work. Except for this time, when he shows up, he’s clicked to this thought process that he’s going to rescue everybody from all of their illusions and he’s going to have this crash course in confrontation of self because he’s had an epiphany.

It seems to anticipate all kinds of things about self help psychology.

Exactly, exactly.

They must have existed somewhat in the American character, but you didn’t have Tony Robbins in 1912 –

I know, exactly, exactly, exactly.

You didn’t even have Dale Carnegie yet, I don’t think –

Exactly, exactly. No. You didn’t have A.A.

Right, right.

But he’s on a mission to solve everybody’s life and he needs to do it in a finite amount of time.

This guy traditionally has been the life of the party, right?

Yes. Exactly, exactly. He brings joy and drunkenness and foolishness and no sense of responsibility, and all of a sudden, I’m going to change you instantly.

You’re going to be better because I now understand what that means and what that means is living your life without any illusions, without any bullshit, without any fake promises of what you’re going to do tomorrow. Confront your limitations. Confront the shallowness of the pressure that you put on yourself and you will be free.

This is a dangerous possibility for any of us, isn’t it?

To all of us, exactly. I mean, it sounded like what is that correct proportion of truth than lie that we need to live with.

Because if it’s too much one way or the other, we’re screwed.

Because — I don’t know about you — I don’t actually spend all day drinking, but that doesn’t mean that I don’t have illusions.

Precisely. Exactly and that’s how we wake up in the morning. It’s like, OK, I’m going to solve everything today and you’ll end up solving one inch of the depth of what you want to solve.

In watching Denzel Washington, his extraordinary performance as Hickey in "The Iceman Cometh," I never actually asked myself whether the character as he was playing him was white or black. Is that in the ballpark of what you guys were going for? Or how did you approach that question? Because you can read the play and say, well, there’s some evidence that he’s probably a white guy from context and there is in fact, of course, interestingly for 1912, a black character in the play, where race is very specifically a part of this story.

Race is very specifically and white privilege is discussed in an incredibly, ridiculously sophisticated way. At one point, the character Joe Mott says to two of his friends, Joe Mott, his illusion that he’s going to open up this gambling joint and he says show up and I’ll treat you white.

If you win that’s gold, and then if you lose it don’t count, can’t treat you any whiter than that. Which is incredibly sophisticated thinking for Eugene O’Neill to have in 1944 about a character in 1912.

But interestingly enough, that is the definition of white. And one point earlier on the character says, when he tries to open up his… back in time when he tried to open up his gambling institution, he goes to this man whose part of the [0:07:53 inaudible] machine and he says, you know, you black son of a bitch, you better be white . . .

And that context is you better pay the bribes that we all pay.

If you play the game, you’re white.

Hickey shows up and Denzel is a black man. He’s going to be a black man on stage, but he shows up with money. He shows up with possibilities and he’s connected to the world in a way that none of them are. They’re given the advantage point that they are looking at the world which is from the bottom up. He’s a star.

I think that when somebody is buying a series of people who are drunks free liquor for two weeks to two months, I really don’t thing race is going to be a part of their conversation.

They're going to select to not observe his color at one point.

One hundred percent. But color — [the] color white is possibility.

One of the things that I think O’Neill does which I think is really brilliant, with Joe Mott but with all the characters that went there, three women and the character who are prostitutes, is that he get some access to their rage. Which is a really astonishing thing.

Because if you look for comparable movies, if you look at anything that Hollywood was producing in 1944, it’s no where near what these characters are allowed to have and what they’re allowed to express.

Interestingly enough he said it in 1912, because 1912 was a very monumental year for him.

He tried to commit suicide. He travelled to Buenos Aires. He acquired a neural disease from a prostitute. He became a writer. He decided he was going to invest in becoming a writer, Eugene O’Neill did. It was a transformational year and he spent a tremendous amount of time living at two rooming houses which were connected to bars — the Golden Swan, which was on 6th Avenue and Jimmy the Priest, which was on Fulton, where the site of the World Trade Center was, and it was torn down for that.

He said really fascinatingly, and his father was a very, very, very famous and very successful actor, living in those places taught him to not judge anyone.

It gave birth not only to him as an artist, but I think expanded his definition of himself as a human being on the planet.

Well, that’s very interesting because in watching the play I was sort of identifying the character that David Morris plays — who by the way is fantastic, I’m so glad to see that he got a Tony nomination. But I sort of identified David Morris’ character as maybe being the authorial voice or stand-in, but maybe it’s the younger guy too, Parritt.

O’Neill does a really interesting thing. There’s a relationship between Parritt, the young kid, and Hickey. You know that they are both haunted by the past. One speaks very specifically. Hickey does about his father and never mentions a word about his mother and he’s haunted by the mother. Together they are a collective person in some respects and [the question they explore is] that can you escape? Can you escape the pain of your past? Can you escape your legacy and redefine you? The young kid is defined by a very, very powerful of mother who is committed to a cause and not at all the least be committed to him.

It’s really fascinating just the range of characters and the range of many women that are presented in, in this play. It’s such an incredibly expansive and sophisticated brain that’s working, and at 1944.

Obviously, this was something that you and your cast worked on very hard, but for a play that was written 70 years ago or so, I was really startled to feel how contemporary it felt in terms of the issues. You just mentioned the political element that comes up, which is something that recurs in America likely. The elements of race and ethnicity that come up. As a comment on masculinity, which is a very contemporary topic.

Absolutely. Totally it is. It’s out. It was also interesting to me that he wrote it very late in his career and he followed this by “Long Days Journey into Night," which is his most intimate play.

But this is also astonishingly intimate too.

And he sets them both in 1912. Interestingly or not.

Interesting. He was about 24 or something in 1912. That's quite a young man.

Yeah, very young man. Very young. Very young.

But the stuff about how to function as a man and how to relate to women, there’s even weirdly a kind of a #MeToo subject to this play —

Yeah. Exactly. Exactly, exactly, exactly. Because these issues, because frighteningly or brutally, we go on a journey and we end up back at the same the place.

We’re evolve. We’re clear. We have that nowhere not. We broke and thrill. Everything is better, no it’s not.

You know what I mean and I think they’re because I think that’s the character of the American psyche because we figure out, and one of the things that I think is really interesting is Hickey is trying to do something that in its own way is incredibly powerful, which is confront the truth.

He’s trying to do it at a rate and an intensity that is impossible for any fragile human being to process, but he is trying to look truthfully, and O’Neill is trying to look truthfully, at what’s going on and what’s happening. And we frequently rewrite history as the characters do at the end of the play.

We bury the truth and rewrite history so that we don’t have to take any responsibility for events that happen.

It’s an incredibly sophisticated thing that we all do. Yeah, well, but I wasn’t and yeah, well, but I know, but still. We all play that game on ourselves. We play the game on ourselves, individually, and we set play within the politics and the racial and sexual and gender identity reality of America. Yeah, I understand, but.

One of the things that struck me, I think we now gotten to the point where we don’t necessarily think of these so-called realist American plays — thinking for example of O’Neill, of Arthur Miller, of Tennessee Williams. We don’t think of them as just realistic. They have another dimension to them. I felt like you were playing with that it at times.

I very much [was]. I read this quote of the original designer of "The Iceman Cometh," and he said, “Realism is the thing we do when we don’t go quite up to that extra effort.” That quote, it exploded my brain.

[O'Neill] was experimenting with form and so there’s this kind of fallacy which I really resent . . . that he evolved. That all of that was experimentation and now he finally became a mature artist with "The Iceman Cometh." No, my contention is all that experimentation of form, of style, is all present in "Iceman Cometh." It’s all there.

What’s also interesting in the year 1912, he was forced to marry this woman because of the fame of his father. And in order to get into a divorce, you had to prove infidelity. He went to a whore house which was right across the street, at that time it was across the street from the Lyceum Theatre, picked out a woman, went upstairs, after an hour invited his lawyer and her lawyer up to witness them in bed so that therefore infidelity could be proven. He then went the next day, expecting money from his father and never received it. And then he tried to commit suicide.

Then, a period later, he then went on tour with his father who was performing the Count of Monte Cristo in Vaudeville. Those Vaudeville union rhythms desperation of young man wanting the approval of his parents, who try to kill himself, who was forced to exposed himself to all of that is inside of this play. He didn’t set it 1944. He set it in 1912 which is not only an expression of the time period, but anexpression of who he was at the time.

He was a person. The writer was a person searching for an identity and that rambunctiousness and that volatility of trying to figure out who you are is built into the play. And so stylistically all of that is in the play.

I didn’t want to entomb the play — and I do mean that in a literal sense — in these walls and in a heavy handed realism. It’s been done that way and done that way beautifully, but I was intrigued by what happens to the language. What happens to these souls when they are allowed to breathe in a space where you’re not completely always? You’re watching true emotions but you aren’t unnecessarily always watching realistic behavior.

These are loaded terms, but there’s something almost incantatory ritualistic in this production.

Yes. One hundred percent.

I was struck by the similarity, and I may know it from your European folk tales but I think, every single tradition has the tale of the devil or the trickster or the demigod, where the trickster figure comes to town with a message which is a very ambiguous message. That is kind of what the story is, right?

Exactly. It’s very much so, very much so. It’s really interesting that you picked up that particular trait of incantation because it is to me, it’s symphonic.

It’s emotionally and linguistically symphonic. There are these recurring themes . . . how people’s language and how people tell one story one way and they repeat the story another way and then they tell the story the third time, and what's shifting are the stakes in the desperation behind it. But so there are these recurring linguistic and musical motifs and what of the things that’s really fascinating it was trying to figure out the music if you will of each act because it’s very, very different.

Also, I wanted to try to craft the space so that it was also very different and you’re watching the frailty of the human condition served up to you. A music serves truth up to you in a really interesting way that allows you to luxuriate in its beauty and at the same time to hopefully see yourself in its fragility.

That’s marvelously put. I was struck by the fact that Hickey seems to be able to hear what people say about him when he’s not on stage.

I’ve never noticed that end of tale before. I do want to ask you one question before we close about something else which is a play that you were intimately associated, “Angels in America." It’s back on Broadway for first time since you were the director of it in the '90s, right? You must have emotions about gladness, a sense of disconnection, the fact that it’s your baby.

Well, all of that. I mean, all of that. There’s an incredible sense of pride. There’s an incredibly shallow sense of why are you dating someone else? You love only me. But at the same time, there is majesty in the words.

There is majesty in the words and the next generation of clueless, or not so evolved people you need to pass in that majesty.

At the end of the day, the best part of me goes, I’m glad it’s here and I’m really thrilled that people are going there and experiencing its power and its command and its truth.

I’m really thrilled about that, but it was an extraordinary journey to work on that play. On the opening night, I think I walked on stage with a cane, because I had gout, because I was beaten the hell up by it.

I remember it, we played at the Walter Kerr Theatre and any time I went into the Walter Kerr Theatre for at least three years after . . . it was like . . . I’m back at the scene of the crime.

At the same time, I worked with an astonishing group of actors, an astonishing group of wonderful, wonderful, wonderful, actors. I received Part One ["Millennium Approaches"] as sacred text. And then Part Two ["Perestroika"], I think three or four days prior to going into rehearsal, I got five new acts into the course of the rehearsal process, and two-thirds of those five new acts changed.

But then, there are days where Tony [Kushner, the playwright] would go "I wrote this thing," and you read and it’s the character of Belize’s vision of heaven that he says to Roy Cohn. And it's exquisite writing. I was in that room the moment the first time those words were said. And that lives inside of you in a perpetually intense, raw, lovely extraordinary way. And at the exact same time it’s like and now and your job as helping to give birth to it is done. Now, it’s out in the world and people are experiencing it. That’s thrilling. That really is thrilling.

Fox News’ Melissa Francis on #MeToo in media and why “you cannot just have one news source”

Getty/Mike Coppola

Melissa Francis has been working her entire life — she booked her first commercial when she was six months old. But after a high profile stint on "Little House on the Prairie" as Cassandra Cooper Ingalls, she stepped away from acting, got her education and embarked on a career in journalism. Today she's the co-anchor of "After the Bell" on Fox Business and a regular on Fox News.

When her latest memoir, "Lessons from the Prairie: The Surprising Secrets to Happiness, Success, and (Sometimes Just) Survival I Learned on "Little House," came out in 2017, her network was embroiled in the double disgraces of Bill O'Reilly and Roger Ailes. Now one year, a #MeToo movement and the Cambridge Analytica scandal later, "Lessons from the Prairie" is out in paperback, and her observations about harassment and media accountability have taken on new resonance. Salon spoke to Francis recently about public trust, reaching across the aisle and why she wouldn't want to live a fairy tale.

You've talked about your experiences with sexual harassment early on in your career. I've read some of the interviews you did a year ago about what was going on at Fox News and what you thought about those things. Now, what began as a few seemingly isolated examples of men in power abusing their positions is an entire movement. We are seeing this conversation across all industries. You were one of the first people really talking about this in your book. What has this year changed for you?

I’m in awe of the distance that we have traveled. I will never forget that the first day I went out to promote my book was the day after Bill O’Reilly was fired from Fox. I was going over to the "Today" show to be on with Hoda and Kathie Lee. I knew, of coursem that they were going to ask me about Bill O’Reilly because they’re reporters. How could they not?

One of them said to me, in essence, “What is in the water over there at Fox — the combination of Bill O’Reilly and Roger?" I said something to the effect of, “It’s been very painful, and we’re going through our stuff, and I do believe that the network is committed to cleaning things up. But I've got to tell you, there are predators in this building too and they’re at every network. It’s not a left/right thing. It’s not a media thing. It’s not a network thing. It’s everywhere. I bet people here know who the people in this building are who do really similar things."

I had had experiences where other women at NBC had come to me crying in the aftermath of having been grabbed, various things. And I had offered to that person to go be the witness, because I was there in the direct aftermath. And they had said, “No, I don’t want to because I think that would be the end of my career.”

My husband had said to me, “Why do you think it is that it’s all come out about Fox, but we know this is going on at the other networks?” He was there at the time when I came home and said, “You’ll never guess what happened at work." And I said, “I don’t know. Hopefully, the movement's big enough that the women at these other networks will feel safe finally coming forward and they’ll see a light rather than, they'll will never work again in this industry by virtue of the fact that they've have reported this incident. They’ll instead feel like there is the support out there for them to come forward." And sure enough that’s what happened.

I know it’s really hard. And I even faced blowback since then, where people say, “If you knew about people at other networks who were doing this, why didn’t you say anything?” Number one, I would say, “Because it didn’t happen to me. It happened to someone else, and I was a witness for that person. So it was their decision as a victim whether to come forward or not.” But at that time, I certainly sympathized with their feeling that there was no point in coming forward.

In fact, as I said in the book, my first experience with this was when I was very young at a local station and my news director showed up [on] my doorstep in the middle of the night.

I was doing an early morning shift, and so I had been asleep for quite some time. I opened the door, and I was very disoriented, and he was clearly inebriated. He was on the phone, mumbling about telling his wife that he was on the doorstep of this young girl and what he thought was going to happen when he entered the apartment. I was floored because I couldn’t figure out what I had ever done to give him the impression that that was going to be OK.

Somehow I faked some sort of highly contagious disease that kept him from coming in my apartment. But in the morning when I woke up, I called my agent and I said, “You got to get me the hell out of Dodge. He’s going to sober up. He’s either going to be angry, or humiliated, or whatever, but no matter what it is, I can’t stay here because he also thinks that this is OK.” And I fled the city.

What I realize now in this day and age is that I left that monster there to prey on many more women. I feel really bad about that. I also don’t know if there even was an HR at that station. He was the boss. I don’t know who I would have told, but I did leave him there. I think that we have come a really long way.

This was a very pervasive problem and it had nothing to do with politics, or what side of the aisle, or any of the other things. It was a pervasive problem in industries where the jobs were highly coveted, where people would stay quiet about horrible things because it’s so hard to get the job and so hard to keep the job. That was one of the things that contributed to it. But I do really believe it’s over because it has swept so wide and so pervasively.

I also think that for many of us for a very long time, it seemed like experiences were isolated. You weren’t hearing other women coming forward, so the idea that, “Oh, yeah. This guy is doing this to other people,” seemed almost impossible.

It just didn't seem possible. There was also that pervasive thing that we know as women, where when a woman is successful, they would say, “Oh, she’s sleeping with the boss.” I used to cover energy for CNBC, and I broke a lot of stories on energy. I remember there was this pervasive [rumor] that there was something going on between me and the Saudi Arabian oil minister. He was over 80. It was the most ridiculous thing in the world. I wasn’t even insulted by it because it was just so common to claim that something was going on based on the fact that a woman was getting ahead, that that conditioned me to be like, “Nah. Nobody’s having sex in our office, that’s just a rumor.”

In your book, you talk about how you have tried to figure out how to balance the illusion of objectivity in your career. And you ask specifically, why should news people be neutral? That's fair enough, but we look at where we are now from where you were writing this book, about two years ago. Katie Couric has brought up this distrust that is so pervasive among people now with the media. And she's said it’s because we’re all so much in our silos and we are getting our information from sources that reinforce our own points of view.

How do we get past that? How do we, as journalists, work our way back to public trust? How do we reach across the aisle and foster real dialogue and real diversity of opinion?

One thing I do on a very basic level is read everything: read the competition, read the other side, read the groups that are painted as being in opposition to Fox or Fox Business, and try and see how their take is different.

I do a lot of debate shows here at Fox where they have liberals on. I think you have to constantly expose yourself to the other side of the argument. But I think what’s a lot more nefarious than a lot of people give the credit is really about the algorithm. When you click on a story online, when you click on a video, there’s an algorithm out there. The point of Facebook, and the point of Google, and the way they make money is by the amount of time that you stay on their site. One thing they figured out through the algorithms is, “Oh, she likes this kind of story, so I’m going to feed her stories that are similar. What are the keywords, and what’s the point of view?”

People warned me about this a year, two, three years ago, that the most dangerous place to get your news is Facebook. I knew about this ages ago because there were engineers who had written the algorithms, who told me the point is they’re customizing what you’re seeing to make you feel satisfied and happy and stay there longer. There’s nothing wrong with that; that’s their business. The amount of time you spend on the site is something that they monetize. But the way they do that is by reflecting stories back at you that already agree with what your opinion is. That’s really dangerous from a journalistic and human being point of view because you live in this echo chamber forever. I have been knowledgeable of that and make sure I break out of that, also because it’s my job.

What’s different about my job is that when I’m facing a guest one-on-one, my job is to take the opposite side of that guest, whatever it is, and challenge them. If there are two people that I’m interviewing, my job is to try and keep their debate balanced and if somebody is really getting their hat handed to them, to intervene on the side of the person who’s weaker to help the debate be balanced. When I’m in a group show with four or five people, my job is to bring an original point of view or nugget of information and a fact to the discussion or a point of view that the others haven’t considered. All of those things take a ton of research every day. I have to dig down into all different types of points of view to know an angle from everybody’s side.

[For] people that, it’s not their job and they’re just trying to get their information in the morning, it is incredibly dangerous. You sit there in an echo chamber. I can tell because when I go out and I talk to people casually, they’ll tell me, “Oh, my goodness. I can’t believe . . .” and then they fill in the blank about a news event of the day. And I can tell by virtue of what they’ve said which channel they watched that day. I’m like, “You've got to try and mix it up.”

If you want to really know what’s going on, you cannot just have one news source. Even if you think there’s a news source that you trust and you believe in, you've got to continue testing that and go look at something else. I think now since the truth that we all knew about Facebook has been exposed, more people out there understand that you've got to educate yourself across all lines.

We’re never going back to the days when there was one guy telling the news at 6 p.m. and that was it. We have so many opportunities now to really micro-curate the information that we get.

The other thing that’s amazing about it is that I ask reporters, “Why do you think it is that all all these stories have come out about predators and before, those predators were able to use lawyers and money and intimidation to keep the stories from being published?” And they say, “Social media.” Before, as a news organization, you would have to really bring a lot to your editor to publish a story that was so shocking that it was going to really take someone down. You had to have so much evidence, and chances are that person, if they were powerful enough, they would have gone in to threaten somebody. It was so hard to do before, that the stories weren’t getting out.

Now, a victim can post their account on social media and the news organization can then investigate it without worrying about being sued because they’re investigating a claim that’s already out there. The reporters have said, “If somebody wants to hide what they’ve done, they probably aren’t able to find and buy out every single victim. Someone’s going to go online.” Or a friend of someone is going to say, “Guess what I heard about this one?”

You just can’t keep things quiet any longer, and yes, it makes it easier to make false claims. When you see one claim about someone and then no one else says anything, you kind of wonder. But when there's this chorus about somebody, you’re like, “Well, wait a second. There must be a nugget of truth in here, let’s investigate.”

The reactiveness has changed so much in the past year or so. I think that the willingness to believe survivors has really changed. The initial, “No, no, no,” because he’s famous or he’s rich or he’s powerful, has definitely deteriorated.

But speaking of image and power in the media, one of the things you are very, very much trying to advocate for is keeping it real, Melissa.

It would break my heart any time I went on a field trip and a mother next to me would say, “How do you make your hair so perfect? How do you do this?” I’m like, “I don’t. There are fairies that do that. I’m wearing three pairs of Spanx and I have 47 fake eyelashes on right now. In the morning, I look horrible.” It’s important for people to know that, because when we hold ourselves up to this false, fake idea, we drive ourselves crazy, and we miss what is important and what is beautiful in our everyday lives.

I joke about showing everyone your cellulite, but there’s a plus side to being vulnerable and to being real, and it's that people like you better. We hate Superwoman. We hate her. She’s usually a bitch, and if she’s nice, that’s just one more thing that we can’t possibly achieve.

There’s no reason to pretend. And it’s exhausting. I’m also at an age where I don’t care that much about what other people think. I’m me. I’m fine with it. I’m tired. I've got yogurt in my hair most of the time and you know what? I’m doing the best I can.

That’s one of the blessings of getting older. You have the wisdom of experience to know that you will bounce back from challenges. You certainly talk about that a lot in the book. But I’m wondering why, Melissa, do you think we still are fascinated with perfection? Why do we buy into it? Why do I go on Instagram and look at pictures of beautiful women who do seem to have it all, and their table is perfectly set and their hair looks wonderful?

I was having this conversation with, of all people, my makeup artist this morning. I was saying, “It’s funny that we like to watch royal stories and fairy tales and not only the royal wedding, but 'The Crown' and all that kind of stuff.” I said that it’s funny because it’s almost like watching the perfect fantasy. You would think it would be irritating, but for some reason, it’s escapist and you watch that like, “Isn’t that pretty?” I guess maybe the next layer is knowing you look at it as pleasure to the eye. It’s interesting to see what’s going on. But then, on some level, it’s not annoying because you know that so much of it isn’t real. And the truth be told, would any of us really trade places with Meghan Markle? I know I wouldn’t. She’s got a lifetime of no privacy and no time to herself ahead of her. The night in which she gets in bed to eat bonbons and watch reruns is never going to happen.

Or pizza bites! When the Duchess of Cambridge left the hospital with her baby the same day that Louis was born, I was like, “Come on, lady. You've got to be kidding me.” The hours after you have given birth are not a beautiful People Magazine cover by any stretch of the imagination for most of us.

I can’t imagine anything worse than knowing that the whole entire world is standing outside the hospital waiting to take a picture of you when you exit. Can [you] imagine if you went into a delivery room and you told a woman, “The whole entire world is going to be standing outside the hospital to put you on camera forever the second you leave”? I think that we would have to be put in a straightjacket.

The truth of their predicament isn’t glamorous or fairy tale at all. But still, there’s that moment where it’s a happy story, and you escape, and you look at them with the kids and how much they look like they’re in love, and you escape into that fantasy. It’s a little diversion during the day.

You talk in the book about the liberal and progressive media. I appreciate when someone is willing to talk to someone who carries around different opinions and who sees things through different eyes and [is] able to say, "Can we have a civilized conversation about pizza bites, or parenting or other important things?" Because it is really important.

My seven- and 11-year-olds have both gone to school and had people tell them, “Your mom works for fake news.” One even said, “Your mom’s a liar.” It’s hard for kids to hear that. Megyn Kelly’s a good friend of mine, and certainly she's faced a lot worse than that. What I always tell [my children] is that, “We are like opposing sports teams or football teams out there. We may go out onto field and you say, 'This one’s fake news. That one’s fake news. You’re doing this. You’re doing that. But at the end of the day, we’ll all meet on the field and shake hands.'" That is honestly my view of it in real life. We’re all moms, and dads and humans.

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Katie Couric's #MeToo moment

The veteran journalist on shattering the glass ceiling

Judge rules Trump can’t block users from his Twitter feed

Getty/Chip Somodevilla

President Donald Trump cannot block users on his Twitter feed, a federal judge in New York City ruled on Wednesday.

Preventing individual users from viewing his Twitter account is unconstitutional and a violation of the First Amendment, Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald wrote in her ruling. Twitter, she said, is a "designated public forum" from which the president cannot exclude certain plaintiffs.

"While we must recognize, and are sensitive to, the President’s personal First Amendment rights, he cannot exercise those rights in a way that infringes the corresponding First Amendment rights of those who have criticized him," Buchwald wrote in her ruling.

The judge's ruling was in response to a case filed last July by the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University. The institute represented seven individuals who said they had been blocked from directly interacting with the president on the social media platform.

The Knight Institute's executive director, Jameel Jaffer, said in a statement, "We're pleased with the court's decision, which reflects a careful application of core First Amendment principles to government censorship on a new communications platform."

Jaffer added, "The President's practice of blocking critics on Twitter is pernicious and unconstitutional, and we hope this ruling will bring it to an end."

Katie Fallow, a senior staff attorney at the institute, said, "The First Amendment prohibits government officials from suppressing speech on the basis of viewpoint ... The court's application of that principle here should guide all of the public officials who are communicating with their constituents through social media."

The president loves Twitter and his tweets routinely make the news. He even uses the social media platform to announce senior administration departures (Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Veterans Affairs Chief David Shulkin were both fired via a tweet from Trump). In 2012, Trump tweeted, "I love Twitter.... it's like owning your own newspaper---without the losses."

I love Twitter.... it's like owning your own newspaper--- without the losses.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 10, 2012

Twitter announced on Wednesday that it will begin verifying political candidates running for the House, Senate and governor in general elections this fall.

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day.

Beyond Golden Shower diplomacy: Preserving the positive legacy of an empire in decline

AP/Evan Vucci