Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 63

May 26, 2018

Are you and your primary care doc ready to talk about your DNA?

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News.

If you have a genetic mutation that increases your risk for a treatable medical condition, would you want to know? For many people the answer is yes. But such information is not commonly part of routine primary care.

For patients at Geisinger Health System, that could soon change. Starting in the next month or so, the Pennsylvania-based system will offer DNA sequencing to 1,000 patients, with the goal to eventually extend the offer to all 3 million Geisinger patients.

The test will look for mutations in at least 77 genes that are associated with dozens of medical conditions ranging from heart disease to cancer, as well as variability in how people respond to pharmaceuticals based on heredity.

“We’re giving more precision to the very important decisions that people need to make,” said Dr. David Feinberg, Geisinger’s president and CEO. In the same way that primary care providers currently suggest checking someone’s cholesterol, “we would have that discussion with patients,” he said. “‘It looks like we haven’t done your genome. Why don’t we do that?’”

Some physicians and health policy analysts question whether such genetic information is necessary to provide good primary care — or feasible for many primary care physicians.

The new clinical program builds on a research biobank and genome-sequencing initiative called MyCode that Geisinger started in 2007 to collect and analyze its patients’ DNA. That effort has enrolled more than 200,000 people.

Like MyCode, the new clinical program is based on whole “exome” sequencing,analyzing the roughly 1 percent of the genome that provides instructions for making proteins, where most known disease-causing mutations occur.

Using this analysis, clinicians might be able to tell Geisinger patients that they have a genetic variant associated with Lynch syndrome, for example, which leads to increased risk of colon and other cancers, or familial hypercholesterolemia, which can result in high cholesterol levels and heart disease at a young age. Some people might learn they have increased susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia, a hereditary mutation that can be fatal since it causes a severe reaction to certain medications used during anesthesia.

Samples of a patient’s blood or spit are used to provide a DNA sample. After analysis, the results are sent to the patient’s primary care doctor.

Before speaking with the patient, the doctor takes a 30-minute online continuing education tutorial to review details about genetic testing and the disorder. Then the patient is informed and invited to meet with the primary care provider, along with a genetic counselor if desired. At that point, doctor and patient can discuss treatment and prevention options, including lifestyle changes like diet and exercise that can reduce the risk of disease.

About 3.5 percent of the people who’ve been tested through Geisinger’s research program had a genetic variant that could result in a medical problem for which clinicians can recommend steps to influence their health, Feinberg said. Only actionable mutations are communicated to patients. Geisinger won’t inform them if they have a variant of the APOE gene that increases their risk for Alzheimer’s disease, for example, because there’s no clinical treatment. (Geisinger is working toward developing a policy for how to handle these results if patients ask for them.)

Wendy Wilson, a Geisinger spokeswoman, said that what they’re doing is very different from direct-to-consumer services like 23andMe, which tests customers’ saliva to determine their genetic risk for several diseases and traits and makes the results available in an online report.

“Geisinger is prescribing DNA sequencing to patients and putting DNA results in electronic health records and actually creating an action plan to prevent that predisposition from occurring. We are preventing disease from happening,” she said.

Geisinger will absorb the estimated $300 to $500 cost of the sequencing test. Insurance companies typically don’t cover DNA sequencing and limit coverage for adult genetic tests for specific mutations, such as those related to the breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 or BRCA2, unless the patient has a family history of the condition or other indications they’re at high risk.

“Most of the medical spending in America is done after people have gotten sick,” said Feinberg. “We think this will decrease spending on a lot of care.”

Some clinicians aren’t so sure. Dr. H. Gilbert Welch is a professor at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice who has authored books about overdiagnosis and overscreening, including “Less Medicine, More Health.”

He credited Geisinger with carefully targeting the genes in which it looks for actionable mutations instead of taking an all-encompassing approach. He acknowledged that for some conditions, like Lynch syndrome, people with genetic mutations would benefit from being followed closely. But he questioned the value of DNA sequencing to identify other conditions, such as some related to heart disease.

“What are we really going to do differently for those patients?” he asked. “We should all be concerned about heart disease. We should all exercise, we should eat real food.”

Welch said he was also concerned about the cascading effect of expensive and potentially harmful medical treatment when a genetic risk is identified.

“Doctors will feel the pressure to do something: start a medication, order a test, make a referral. You have to be careful. Bad things happen,” he said.

Other clinicians question primary care physicians’ comfort with and time for incorporating DNA sequencing into their practices.

A survey of nearly 500 primary care providers in the New York City area published in Health Affairs this month found that only a third of them had ordered a genetic test, given patients a genetic test result or referred one for genetic counseling in the past year.

Only a quarter of survey respondents said they felt prepared to work with patients who had genetic testing for common diseases or were at high risk for genetic conditions. Just 14 percent reported they were confident they could interpret genetic test results.

“Even though they had training, they felt unprepared to incorporate genomics into their practice,” said Dr. Carol Horowitz, a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, who co-authored the study.

Speaking as a busy primary care practitioner, she questioned the feasibility of adding genomic medicine to regular visits.

“Geisinger is a very well-resourced health system and they’ve made a decision to incorporate that into their practices,” she said. In Harlem, where Horowitz works as an internist, it could be a daunting challenge. “Our plates are already overflowing, and now you’re going to dump a lot more on our plate.”

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

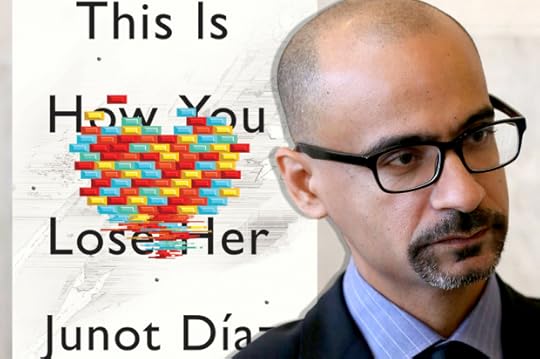

This is how you lose him: When heroes like Junot Díaz fall from the sky

Getty/Mark Wilson/Riverhead Books

On July 12, 1999, Junot Díaz found himself in a place few writers will ever even dream of finding themselves: on the front cover of Newsweek. Díaz is one of three figures standing in a blue sky dressed with clouds.

On the far right, the largest figure — crossed arms, a flat expression wrapped inside a muscular mass of face, reserved, triumphant, is boxing star Oscar de la Hoya.

In the middle: dyed red-black hair falling down in strands, hips curved around the large white letters, "U.S.," the only one of the three whose body faces the camera straight on, and the only one who seems to know how to look at a camera on purpose, Shakira.

And finally, the figure set back the most, his face ornamented with a goatee, a pair of black thin-rimmed glasses and a dry, distant look: Junot Díaz.

Together, they create the human backdrop for the edition’s title, which reads like a declaration: "Latin U.S.A.: How Young Hispanics Are Changing America."

I flip inside and find the title story, then read the first line out loud: "Hispanics are hip, hot, and making history." Much of the rest of the article reads this way, like an advertisement, and struck through with a certain unmistakable hunger. It is an old tired script now, but perhaps in 1999 it rang new, fresh, sellable. At the end of the first paragraph, these hip hot Hispanics are likened to a wave.

There is a world to uncover here, so much to put under a cultural microscope. But mostly what I want you to pay attention to is this: What is Junot Díaz doing there, in that sky?

By the time this picture was snapped, de la Hoya had won boxing titles in multiple weight classes, had taken down stars like Pernell Whitaker and Julio Cesar Chavez, had represented the U.S. in the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games and had come back a household name. In 1999, Shakira was riding on the high of her fourth studio album, "Dónde Están Los Ladrones," an album that earned her $10 million in worldwide sales, a Grammy nomination and a feature recording on "MTV Unplugged." Months before appearing on this cover, she had announced plans to work on her first ever English-Spanish crossover album (and oh, what a crossover it would be).

Then there’s Junot. In 1999, Junot Díaz is a 31-year-old writer with a recently published collection of short stories, "Drown," and a novel in the works. "Drown" does well, probably as well as a first book could hope to do: a shining New York Times review by David Gates, a slew of literary buzz, two pieces featured in America’s Best Short Stories. And yet, Díaz was a young writer. His best known works, his Pulitzer Prize, the vast majority of his literary accolades were all years away, part of a distant future. Yet there he was in 1999, suddenly, if not all at once, planted in that sky. When I find the photo researching Junot Díaz’s rise to fame, I wonder why he is there, and I wonder what it might have to do with that hunger, a hunger for a Latin U.S.A., and maybe for a figure in that landscape who isn’t known for shaking their hips or knocking people down in a ring. Instead, a writer: male, genius, able to speak the stories of his world for anyone who wants a peek in.

And yet we can’t be unfair. It wasn’t just Newsweek and The New York Times. It wasn’t just White Liberal America who was hungry for Junot Díaz. In high school, when a friend left a copy of "This is How You Lose Her" in my backpack, resting against my biology textbook with a yellow post-it note pressed onto the front cover that read I think you need this, he was right, I did need it. Sixteen-year-old me, full of hungers, ready to place Junot Díaz in my own clouded sky.

I am trying to write about Junot Díaz; his books, his harm, and what all of it might mean for a Latinx book lover and a young man committed to the responsibility we all share in this moment of standing against violence.

Over the past several weeks, a growing collective of women, mostly women of color, have come out accusing Díaz of sexual misconduct, abuse, assault and bullying. I stand by these women. I believe their accounts. I believe their descriptions of his violent behavior to be true. And I believe in the need for real accountability.

These beliefs all point me in one direction, towards a question that has silently inhabited my life since the news broke: How do men, particularly Latinx men who saw Díaz as a hero, move forward in solidarity?

I'm trying to piece together answers to that question. Unsurprisingly, it all starts here, in that sky, our national sky and my own male sky, trying to understand what Junot Díaz was doing all the way up there in the first place.

*

Here is the short story of how Junot Díaz ended up in my sky.

In 2013, I was 16 years old, and everything in my life seemed to be breaking or moving. My parents split up, my first relationship was in pieces, my sister moved to college, and there I was, standing in the wake of it all, struck by a grey, dull feeling I would later learn has a name: Depression.

Reading is a collision — the sometimes explosive meeting of a particular book and a particular moment in a human being’s life. It's hard to piece apart the exact physics of any such collision, but in the case of me and "This is How You Lose Her," I will try. Some books meet you as companions, and yes, in Díaz's protagonist Yunior I saw a young Latinx male artist struggling with the broken pieces of family, struggling with mental health, with his weight, with the project of masculinity. I identified. It helped.

But there were other things, too, other forms this collision took. For me, "This is How You Lose Her" fell into my hands most of all as a map. All the simultaneous internal and external damage of being a man mapped out naked and bare. A set of codes I could and would use to start to make sense of all the male bullshit in my life, all the hurt it had caused. The honesty of its coordinates spoke to me.

What happened next? I clung to that book like I had never clung to a book before. I carried it everywhere, like an asthmatic carries an inhaler, and read it over and over. You wouldn’t catch me without it: in classes, at track practice, at a party, sleeping in my bed — it was never more than 100 feet from me. Then I burned through his other books, started listening to his lectures on YouTube, taking notes in the back of my journal. Notes on “the predatory nature of privilege” and on “racially organized sexual economies” and on “decolonial love.” Somewhere along the way, my heart had quietly taken to building its very own Junot Díaz altar.

Looking back at a journal from that time, I read my own account of what it felt like. I call it a grayness in me, building and building until it felt like I could explode, until it was all I could do to try and put it somewhere. In the search for that somewhere, I decided to write a song (I had taken to studying and practicing music with some discipline back then, and had the basic tools). My silent hope, not written in my journal but remembered, was to speak back to, in some way, the book that had meant the universe to me, to craft my own side of the collision.

I ended up writing a song with four vocal parts, set to the epigraph of "This is How You Lose Her," an excerpt from "One Last Poem for Richard" by Sandra Cisneros. I called my song "One Last Song for Richard." By some stroke of magic, charm and pity, I was able to convince my high school choir teacher to let us sing the song in class. Then I got a recording at our concert, and with little forethought I posted the song on YouTube. One day, the idea landed in my heart like a promise: Send the song to Junot Díaz.

My email was short, a link to the song and a quiet thank you for what his art had meant to me. Then, the act of universal wonder: a note from Junot Díaz landed in my high school email inbox. He told me my art is wonderful and asked me questions about my life (my life!!). We began to talk. All of a sudden, a whole set of miraculous things happened. Junot posted my song on his Facebook page, called it extraordinary. Strangers began to comment on the song. Sandra Cisneros wrote me an email thanking me. I emailed Brown, my dream school that weeks ago had sent me a waitlist letter (which basically read: you have some things going for you, but no), and told them what had happened. They accepted me less than a week later.

I told Junot Díaz I wanted to be a writer. He told me not to major in creative writing in school but to focus on my music and my life, that that would help my writing the most. I packed my bags for Providence intent on keeping his promise, the architecture of my Junot altar as strong as my own bones, and as firmly lodged inside of me.

This is how much Junot meant to me. He wasn’t just a hero of mine. He was the centerpiece of my sky.

For years I’ve kept that story wrapped, packaged, accessible at any time. I used to call it: the most awesome thing that ever happened to me, because it was. Such a finality to what I thought that moment had meant. So untouchable, in my mind, by any goings-on in the present — whatever shit was happening in my life, I could go back to that story, hold it in my hands, think damn, that was awesome. Junot Díaz, that man I had placed in the sky, reaching right into my life on the ground, saying you matter.

Here I am now, unwrapping, pulling apart at the wreckage of it all. Salvaging what can be salvaged, and leaving what must be left to float away. I wonder about the space between who Junot Díaz is, and who the 16-year-old me needed him to be. I trace the outline of that space, measure its coordinates on a new map. Could this be my task? To fill that space with something different, something new?

*

Maikerly and I have dinner to talk things over — her MCAT score, my relationship and what’s been going on with Junot Díaz. Maikerly came over from the DR when she was a kid, and somehow we both ended up at Brown. Now in our senior year, she’s my friend and my sister, equal parts. Together, we are mourning our hero.

And he’s Dominican. A Dominican getting big like that. That’s fucking rare. Her voice is cracked with anger. We’re sitting in her kitchen, scrolling through Junot Díaz headlines like footage of a natural disaster.

It is an anger connected to worlds Junot Díaz stands for. Not just Latinx, but Caribbean, Dominican, of African descent. It is an anger I can respect but cannot fully understand.

We are two 22-year-olds born in 1996, the year Junot’s first book was published. Our whole conscious lives have been lived with the fixture of the Latinx male genius writer who seemed to tell our truths.

We read the stories, though, all of them. The one of him asking a woman to clean his kitchen, the one of him asking a student in his program to keep their relationship quiet. The one of him kissing a grad student forcibly. So much of him and these women, shaped by asking, then sometimes shaped by not asking at all.

We read reactions. We find inspiration in the bravery, the honesty, the vulnerability of so many others.

Some say Junot Díaz is a bad writer, though, and I wonder, not about the validity of such an assertion, but about its convenience. It's easy to deal with a harmful person who is also a bad writer, easy to place that person. But what do we make of a broken, harmful person who is also a good writer? What do we do with the possibility that his brokenness, his intimate terms with harm, is also what makes his art possible, or powerful?

These are questions that inhabit the air around us, floating with the sharpness of a knife. For now, we let them be. Maikerly wants to become a doctor, and I want to be a high school teacher. I joke: Maikerly, maybe you could be my new hero. Her laughter comes out in bursts, spilling into the air around us until everything feels less sharp. We cook dinner, and we don’t talk about Junot Díaz again.

*

It’s 2013, and it’s raining. I am lying on the floor of my living room, back to the sky, re-reading "This is How You Lose Her." The first story, "The Sun, the Moon, the Stars," begins with lines I’d long ago memorized: “I’m not a bad guy. I know how that sounds—defensive, unscrupulous—but it’s true. I’m like everybody else. Weak, full of mistakes, but basically good.”

All at once, the pages disappear. My sister Livia has pulled the book out of my hands and is holding it in the air like a toy I wasn’t supposed to be playing with. "This book is so sexist," she says, "I don’t get why you’re so crazy about it." I reach for it — my inhaler — but she is already by the stairs taking the book away.

Trying to find my breath, I offer what I know to be true. "That book means everything to me."

Back then, with all the forthrightness of a little brother, I had come to one conclusion about my sister’s opinions on Díaz: she doesn’t get it. She must be missing something. How could something so impactful to me be so easily dismissible to her. She’s wrong.

Now I am doing away with those certainties and wondering what it would mean for both of us to have been right.

For me, "This Is How You Lose Her" was that map, that everything. My own toxic masculinity Rosetta Stone.

For my sister, "This is How You Lose Her" was a book without any women. So many female characters, but where were the women? Where were the capital-w Women with their humanity in full sight? To her, this book was nothing more than a tired script, a re-inscription of a language that has already been inscribed too many times on every surface of our world.

Reading is a collision, shaped by the human being on the other side of the page who is looking in, and the things they bring — their wounds, their hungers — to the words on the page.

No wonder she grabbed the script out of my hand. To me, this act represents so much of growing up male in a household of women. Me, coming home with a masculine script I’d been given from the world. My sister and my mother pulling it out of my hands, commanding me: Be a good man, be different, don’t be like them. And because I love and admire them more than anything, I would try, as hard as it is to walk through life without a script.

So many people say these stories about him sound just like his books. This feels wrong to me. These stories are not his books. They are the opposite of his books. They are his books’ blank pages, the spaces between the lines. All those female fixtures, collateral damage on the path of Yunior’s self-realization, now alive, human, here to say, me too.

*

I wanted to write an essay about taking Junot Díaz out of your sky, particularly for men. I wanted to arrive in a place with a formula for how to de-heroicize the man who had been our biggest hero — not only for me but for others too. I know I’m not the only one who put him there.

There doesn’t seem to be a formula. There doesn’t seem to be a graceful way for something to fall from the sky, even a man so committed to grace in all things.

I know this: In college I am able to take new kinds of classes, on topics like Latinx Literature and Latinx Cultural Studies. I read works by Gloria Anzaldúa, Ana Castillo, Julia Alvarez, Cherríe Moraga, Yalitza Ferreras, Daisy Hernández, Patricia Engel and many others. Before college I knew two Latinx writers: Sandra Cisneros (still a God in my heart) and Junot Díaz. Two lone stars. Now, new worlds of writer and books to reach into my life, to give me companions, maps, or maybe to give me new things, too.

I know this: I had made a man into a hero, and losing him hurts. But it is better to let the sky fall. Better to let it fall and see what new things we can build. Better to deal with Junot Díaz as a human being on the ground who’s been hurt and who spread that hurt out and must take responsibility.

An old mentor from my high school years writes this to me, about Junot: It’s all deep. All pivotal. All instructive. Work through this. Internalize this. Be another type of man. So I try. Try to let the lesson in it all reach me, settle in a place deeper than my bones. Let it stay there along with the knowledge that I will be endlessly in debt to the women in my life who have chosen to take the time, energy and love to teach me, to guide me in my struggle to be different.

I look back to that cover of the book placed in my backpack all those years ago. It is a heart constructed from rainbow-colored bricks, some disfigured, glitching, others falling away. Most broken hearts are drawn with a single line. This one, run through with different kinds of brokenness, feels more accurate.

Looking at that cover, I am struck by the realization that perhaps we all deserve more than a model of what it means to be broken. So I take my eyes off the sky for a while and focus on the ground, and commit myself to living life without a script, to constructing my own map along the way, to searching for books that might one day teach me what it looks like for a man to be harmless, to be whole.

Why Katie Couric is rethinking the past

The journalist reflects on power and #MeToo

Debunking the 6 biggest myths about “technology addiction”

Robert Kneschke via Shutterstock

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

How concerned should people be about the psychological effects of screen time? Balancing technology use with other aspects of daily life seems reasonable, but there is a lot of conflicting advice about where that balance should be. Much of the discussion is framed around fighting “addiction” to technology. But to me, that resembles a moral panic, giving voice to scary claims based on weak data.

For example, in April 2018, television journalist Katie Couric’s “America Inside Out” program focused on the effects of technology on people’s brains. The episode featured the co-founder of a business treating technology addiction. That person compared addiction to technology with addictions to cocaine and other drugs. The show also implied that technology use could lead to Alzheimer’s disease-like memory loss. Others, such as psychologist Jean Twenge, have linked smartphones with teen suicide.

A National Geographic Channel show raises alarms about technology use.

I am a psychologist who has worked with teens and families and conducted research on technology use, video games and addiction. I believe most of these fear-mongering claims about technology are rubbish. There are several common myths of technology addiction that deserve to be debunked by actual research.

Technology is not a drug

Some people have claimed that technology use activates the same pleasure centers of the brain as cocaine, heroin or methamphetamine. That’s vaguely true, but brain responses to pleasurable experiences are not reserved only for unhealthy things.

Anything fun results in an increased dopamine release in the “pleasure circuits” of the brain – whether it’s going for a swim, reading a good book, having a good conversation, eating or having sex. Technology use causes dopamine release similar to other normal, fun activities: about 50 to 100 percent above normal levels.

Cocaine, by contrast, increases dopamine 350 percent, and methamphetamine a whopping 1,200 percent. In addition, recent evidence has found significant differences in how dopamine receptors work among people whose computer use has caused problems in their daily lives, compared to substance abusers. But I believe people who claim brain responses to video games and drugs are similar are trying to liken the drip of a faucet to a waterfall.

Comparisons between technology addictions and substance abuse are also often based on brain imaging studies, which themselves have at times proven unreliable at documenting what their authors claim. Other recent imaging studies have also disproved past claims that violent games desensitized young brains, leading children to show less emotional connection with others’ suffering.

Technology addiction is not common

People who talk about tech addictions often express frustration with their smartphone use, or they can’t understand why kids game so much. But these aren’t real addictions, involving significant interference with other life activities such as school, work or social relationships.

My own research has suggested that 3 percent of gamers — or less — develop problem behaviors, such as neglecting schoolwork to the point that grades suffer. Most of those difficulties are mild and go away on their own over time.

Technology addiction is not a mental illness

At the moment, there are no official mental health diagnoses related to technology addiction. This could change: The World Health Organization has announced plans to include “gaming disorder” in the next version of its International Compendium of Diseases.

But it’s a very controversial suggestion. I am among 28 scholars who wrote to the WHO protesting that the decision was poorly informed by science. The WHO seemed to ignore research that suggested “gaming disorder” is more a symptom of other, underlying mental health issues such as depression, rather than its own disorder.

This year, the Media Psychology and Technology division of the American Psychological Association, of which I am a fellow, likewise released a statement critical of the WHO’s decision. The WHO’s sister organization, UNICEF, also argued against using “addiction” language to describe children’s screen use.

Controversies aside, I have found that current data doesn’t support technology addictions as stand-alone diagnoses. For example, there’s the Oxford study that found people who rate higher in what is called “game addiction” don’t show more psychological or health problems than others. Additional research has suggested that any problems technology overusers may experience tend to be milder than would happen with a mental illness, and usually go away on their own without treatment.

"Tech addiction" is not caused by technology

Most of the discussion of technology addictions suggest that technology itself is mesmerizing, harming normal brains. But my research suggests that technology addictions generally are symptoms of other, underlying disorders like depression, anxiety and attention problems. People don’t think that depressed people who sleep all day have a “bed addiction.”

This is of particular concern when considering who needs treatment, and for what conditions. Efforts to treat “technology addiction” may do little more than treat a symptom, leaving the real problem intact.

Technology is not uniquely addictive

There’s little question that some people overdo a wide range of activities. Those activities do include technology use, but also exercise, eating, sex, work, religion and shopping. There are even research papers on dance addiction. But few of these have official diagnoses. There’s little evidence that technology is more likely to be overused than a wide range of other enjoyable activities.

Technology use does not lead to suicide

Some pundits have pointed to a recent rise in suicide rates among teen girls as evidence for tech problems. But suicide rates increased for almost all age groups, particularly middle-aged adults, for the 17-year period from 1999 to 2016. This rise apparently began around 2008, during the financial collapse, and has become more pronounced since then. That undercuts the claim that screens are causing suicides in teens, as does the fact that suicide rates are far higher among middle-aged adults than youth. There appears to be a larger issue going on in society. Technopanics could be distracting regular people and health officials from identifying and treating it.

One recent paper claimed to link screen use to teen depression and suicide. But another scholar with access to the same data revealed the effect was no larger than the link between eating potatoes and suicide. This is a problem: Scholars sometimes make scary claims based on tiny data that are often statistical blips, not real effects.

To be sure, there are real problems related to technology, such as privacy issues. And people should balance technology use with other aspects of their lives. It’s also worth keeping an eye out for the very small percentage of individuals who do overuse. There’s a tiny kernel of truth to our concerns about technology addictions, but the available evidence suggests that claims of a crisis, or comparisons to substance abuse, are entirely unwarranted.

Christopher J. Ferguson, Professor of Psychology, Stetson University

Top Trending

Check out the major news stories of the day

Pete King ironically compares NFL players kneeling during the national anthem to the Nazi salute

AP

A Republican congressman alluded to the Nazi salute in a cringeworthy tweet that denounced support of the NFL players protest.

Rep. Pete King, who represents New York's 2nd District in Washington D.C., took to Twitter on Saturday to disparage his local team's plan to circumvent the NFL's new, zero-tolerance policy on the national anthem protest.

King specifically targeted New York Jets CEO Christopher Johnson, who pledged to pay all fines incurred by his players who kneel during the national anthem during this upcoming season.

King tweeted:

Disgraceful that @nyjets owner will pay fines for players who kneel for National Anthem. Encouraging a movement premised on lies vs. police. Would he support all player protests? Would he pay fines of players giving Nazi salutes or spew racism? It’s time to say goodbye to Jets!

— Rep. Pete King (@RepPeteKing) May 26, 2018

King's stance on the national anthem protest was not all that surprising considering he has backed President Donald Trump's rebukes on the subject in the past. King has publicly stated that he was "proud to stand with Trump" on the controversial issue and called on everyone to support "America's military and police."

King's latest tweet, however, demonstrates a new level of contempt from the congressman. It also reveals his complete lack of understanding of world history.

In 1934, the Third Reich banned a German soccer team for refusing to do the Nazi salute. Newspaper clippings from the time explain that the Karlsruhe Football Club received a twelve-month ban after failing to give the Nazi salute before a match in France. The German club did not make this decision in protest of the Nazi regime. Rather, the French side had threatened to boycott the game if the German players participated in the disdained performance, so the German team acted accordingly. Snopes found a digital copy of the article archived in the National Library of Australia.

Regardless of the German players' motivations, it is ironic that King would compare the Nazi salute to athletes kneeling during the national anthem. The NFL protests began because black players felt as if their community was unfairly treated by the police and that there civil rights were constantly violated. This message has wholly escaped Trump supporters, such as King, who view the national anthem as a mandatory act of national pride and patriotism. That the Nazi's placed so much emphasis on the salute should give normal Americans pause about the meaning and significance of the national anthem. That the Nazi's took punitive actions against those who refused to respect the salute should trouble Americans who feel as if the current administration has spread its authoritarian tendencies.

The debate over the merits of the protests, and their overall effectiveness, only took on more notoriety when Trump offered his nationalistic position that players "shouldn't be playing" and maybe "shouldn't be in the country," in an interview on Fox & Friends.

Meanwhile, New York Jets ownership, which CEO Johnson is a part of, has offered solidarity with the players.

Statement from Chairman and CEO Christopher Johnson pic.twitter.com/4JObk43oDT

— New York Jets (@nyjets) May 23, 2018

Johnson has also put his money where his mouth is.

“I do not like imposing any club-specific rules,” Johnson told Newsday. “If somebody [on the Jets] takes a knee, that fine will be borne by the organization, by me, not the players. I never want to put restrictions on the speech of our players. Do I prefer that they stand? Of course. But I understand if they felt the need to protest. There are some big, complicated issues that we’re all struggling with, and our players are on the front lines. I don’t want to come down on them like a ton of bricks, and I won’t. There will be no club fines or suspensions or any sort of repercussions. If the team gets fined, that’s just something I’ll have to bear.”

This reasonable response from an NFL team somehow enraged a congressman to the point that he would drop his fandom. King's histrionics were obviously the manifestation of a political calculation. King has decided that he should run towards the brewing culture war as opposed to adopting the Karlsruhe Football Club's blueprint--simply refusing to participate.

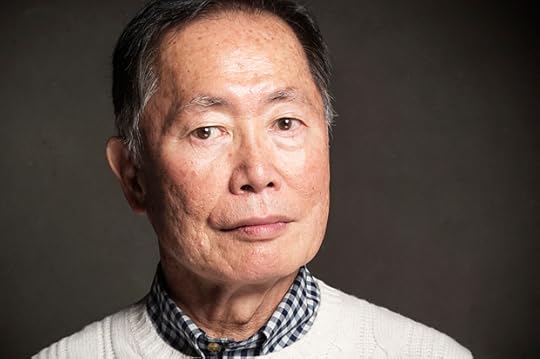

New details emerge about the sexual assault allegation against actor George Takei

AP/Victoria Will

In November 2017, "Star Trek" icon and activist George Takei was accused of sexual assault, stemming from an incident that allegedly took place in 1981. The report was first published by The Hollywood Reporter (THR). Later, Scott Brunton, the former model who accused Takei, said he was also drugged by the actor.

One writer, Shane Snow, spent months investigating these claims, as well as interviewing Brunton, experts and many people who know Takei. The result is a detailed and lengthy article published in the Observer that challenges many of the most damning details against Takei. His takeaway is: "We — both public and press— got the George Takei assault story wrong."

Snow focuses on the inconsistencies in Brunton's story, as told to different outlets once the THR exposé went viral. "Brunton didn’t appear to mention being drugged until two days after the THR story, following Takei’s public denial," Snow wrote. "And then, in a CNN interview, he confusingly didn’t recount any groping."

After the THR story, it was Twitter users who assumed Brunton was drugged because of his description that, after having two drinks at Takei's apartment, he tried to stand up and felt dizzy. He said Takei led him to a bean bag chair, and either he briefly lost consciousness or experienced a short memory brownout. Brunton said after the alleged groping, he was able to sober up and drive home and did not suffer from a hangover the next day.

But, after Takei denied the allegations from the THR story, Brunton told The Oregonian: "I know unequivocally he spiked my drink."

To Snow, Brunton said, "I thought it was just I was drunk . . . I didn’t even start thinking that until years later when they started talking about date rape drugs – and then Cosby and all."

When Snow shared the information with two toxicologists, both immediately concluded that Brunton's drinks were not spiked. "The alcohol alone, if drunk quickly, could account for [his browning out], particularly if there was a bit of postural hypotension," date-rape expert Michael Scott-Ham of Principal Forensic Toxicology & Drugs, a consulting firm in London, told Snow. "To recover so speedily doesn’t sound like the actions of a drug."

After Snow shared the conclusions from the toxicologists, Brunton apparently conceded and said of Takei, "It makes him a little less sinister."

Then, Snow dived into the groping claim, one which he said Brunton vacillated on to the several publications he spoke to. Snow asks:

"Did he touch your genitals?"

"You know . . . probably . . ." Brunton replied after some hesitation. "He was clearly on his way to . . . to . . . to going somewhere."

We shared a pause.

"So . . . you don’t remember him touching your genitals?"

Brunton confessed that he did not remember any touching.

In Brunton's recollection, he said that, all of sudden, his pants were down and Takei was pulling on his underwear, to which Brunton said he did not want to have sex. He said Takei replied, "I am trying to make you comfortable." But Brunton shoved him saying, "No."

Former Senior Deputy District Attorney Ambrosio Rodriguez, who prosecuted rapists and molesters in California, told Snow, "There’s nothing to prosecute here," after hearing about the night in detail. "People get drunk on dates and take off each other’s pants all the time."

Rodriguez told Snow that it is the actions that follow that are critical for legal ramifications. "The crucial detail in the context of a consensual date with two adults who are drinking, he said, is that when the man who made the advance was denied consent, he backed off," Snow writes. "Making a move itself is not a crime," Rodriguez said.

Snow then dove into other details, such as the culture of the Los Angeles gay nightclub scene where Brunton and Takei met and the difference between the lone accusation against Takei and the long-known industry reputations of accused celebrity predators like Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein, including their history of legal settlements.

He also shared some offensive statements from Brunton about Takei and how he oft told the encounter not as a story of trauma, but as "a great party story."

"I rarely thought of it," Brunton said. "He was 20 years older than me and short. And I wasn’t attracted to Asian men." He added, "I was a hot surfer, California boy type that he probably could have only gotten had he bought, paid for or found someone just willing to ride on his coattails of fame."

Brunton said the alleged assault was "not painful . . . It didn’t scar me," but that he decided to come forward after Takei criticized Kevin Spacey for announcing his sexuality as a way to deflect from a pedophilia accusation. Mostly, Brunton told Snow, he just wanted an apology.

There are many more details, but Snow's thesis is about more than Takei or this single accusation. Snow reminds readers that the exposés on Harvey Weinstein in the New York Times and the New Yorker were done over many months and with exhaustive reporting, fact-checking and corroboration.

"But, once that dam broke, the power of and interest in these stories has led to an incentive for the press to get them out quickly and for our polarized social media to quickly weaponize them," Snow writes. "It’s easy to forget that every story has its own subtleties and nuances, and the consequences for getting things wrong can be severe."

He added, "We owe it to both the victims and the accused to investigate all sides of a story before we unleash it for the masses to devour."

On the eve of the 1968 Chicago Police riot, MC5 took a torch to rock & roll

Elektra Records/Bloomsbury Publishing/Salon

Excerpted from “MC5’s Kick Out the Jams” by Don McLeese (Continuum, 2005). Reprinted with permission from Bloomsbury Publishing.

As we made the short walk to the park from Chicago’s Old Town—the neighborhood that was the heart of local hippie culture—our balloon of expectation deflated. Where were all the people? Okay, maybe a half-million had been a bit optimistic, but there weren’t a tenth that number in the park on a Sunday afternoon. Or even a hundredth. Instead, if you counted (and you could have), there were perhaps two thousand milling around the southwestern sector of the park—the Yippie enclave—a motley assemblage of tie-dyed freaks, bushy-haired hippies, curious high-school kids and a few buttoned-down radicals sitting or strolling, looking at each other, waiting for something to happen. We would later learn that, amid the few, there were plenty of undercover agents who had infiltrated the gathering and might later incite some aggressive action.

Instead of the high drama anticipated, the early part of that afternoon was closer to the era’s cliches of summer in the park—mellow, groovy, filled with good vibes. Allen Ginsberg sat in the lotus position under a tree amid the grassy expanse, leading a circle in the chanting of “Ommmmm.” (He would subsequently chant for seven hours, as the vibes turned increasingly sinister.) The two wild-haired, flashing-eyed Yippie masterminds—Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin—put a brave face on the meager turnout, smiling in the sunshine as they scurried and schemed, darting this way and that, recognizable from their pictures in the newspapers as “leaders” of whatever was about to transpire. Yet few of the locals in the park that day seemed to show much interest in following the lead of these manic East Coast activists. Rolling Stone had warned us.

Anyway, where was the music? Where were the Dead, the Stones? Where was Country Joe? From what we could see, the Festival of Life had been a pipe dream. There was no stage, no amps, no mic.

It wasn’t until late afternoon that one band would be brave enough—or foolhardy enough—to attempt to spark a revolution in Chicago and risk the wrath of the police. One band not only matched the anticipatory hype, but exceeded it. One band would transform itself into myth, embodying the chaos of cultural uprising for generations to come.

"Brothers and sisters, are you ready to testify? I bring you a testimonial: the MC5!!!!!”

Let me admit, brothers and sisters, that I can barely remember significant details of the day that I’ll never forget. Impressions dissolve in the haze of marijuana from that sunny summer afternoon in Chicago, while the subsequent passage of almost four decades has sacrificed more to the mists of memory. Yet the imprint remains indelible. Like a car crash or a blitzkrieg, it divides my existence into Before and After. For nothing was more important in my eighteen-year-old life than rock and roll. And rock and roll would never be the same for me after I saw—experienced? endured? survived?—the band that would change my life.

No, I’m not going to pull a Jon Landau. I won’t claim that I had a vision of rock’s future when I first withstood the aural assault of the Motor City Five, whose sound and fury disrupted that idyllic Sunday in Lincoln Park. Contrary to common legend, the MC5 didn’t spark a riot with their free concert on the eve of the 1968 convention. They simply lit the fuse, escalating the tension, energizing the crowd to a fever pitch of musical militancy as the police encircled the park, with their riot gear and billy clubs, maintaining a stone-faced vigil.

I can still see the orb-like Afro of the lead singer as he badgered the crowd, pointing his finger, thrusting his fist, working his feet like a speed-freak James Brown. I would later know him as Rob Tyner, but all I knew at the time was that he was crazy. But not as crazy as the two guitarists, the ones I would later know as Wayne Kramer and Fred “Sonic” Smith, both brandishing their instruments as if they were lethal weapons while swiveling their hips, arching their backs, flailing their arms, kicking their legs.

All this over a rhythm section that left no space unfilled in its relentless propulsion, a bassist and drummer—Michael Davis and Dennis “Machine Gun” Thompson, I would later learn—less concerned with staying within the pocket than obliterating that pocket. When a low-flying surveillance helicopter buzzed the band, the whoosh and whirr of its blades didn’t interrupt the music, but enhanced it. Even the occasional roar of a cop’s motorcycle seemed like part of the musical gestalt, amid a crowd that fully expected that musical chaos would lead to physical violence. This wasn’t a rock band; it was a street fight. This wasn’t a concert; it was a battle zone.

We had been waiting for something to happen, even desperate for something to happen. The MC5 were what happened. We hadn’t known what to expect, but none of us had expected the 5. Almost none of us had ever heard of the band, except those who had made the drive from their native Detroit. Though we thought we’d been ready for anything, the frenzied, ear-splitting performance left most of us shell-shocked. It was a musical mugging so far beyond the realm of expectation that it would take years before punk or metal would provide some sort of frame of reference, though no punk or metal band would ever match the galvanizing force of the 5.

Despite the band’s railings against the “pigs” and exhortations to “kick out the jams,” the music didn’t rouse the rabble so much as render us benumbed or bewildered, confused or bemused. In the wake of that aural assault, the most prevalent reaction was What was that?—mouthed more than heard, with the aftershock continuing to ring in our ears. When Abbie Hoffman announced that the cops had pulled the plug on the festival, as if there was anything on the bill beyond the half-hour blitz by the MC5, an uneasy calm returned to the park, mixed with a sense of foreboding, as the crowd waited once again for whatever would happen next.

It wouldn’t transpire until well after dark, when the 5 were long done and my brother and I were long gone—back to the domestic safety of the suburbs—as those police on the park’s periphery invaded what had once been a peaceful, even playful gathering. By enforcing the park’s 11 PM closing time and camping prohibition, they sent a few thousand protestors fleeing into the streets with nowhere to sleep. As a prelude to four long days of billy clubs and tear gas, no band could have better anticipated the street fighting to come than the MC5.

Salon Talks: Andrew W.K.

The legendary rocker and professional partier discusses his new album “You're Not Alone.”

Guns N’ Roses commemorative album will cost fans $1,000

AP/Reuters/Arben Celi/RTNKabik/Owen Sweeney

The average rock fan may find the upcoming Guns N' Roses album a little hard to get. Next month, the legendary rock band will celebrate the 30th anniversary of its debut album, "Appetite for Destruction," to the tune of a $1,000 commemorative album.

The remastered and expanded edition of the album debuts June 29, made available in multiple packages. The biggest, most expansive package is the Locked N’ Loaded edition, which comes in a huge box with a handmade 3D cross, and will cost $999.

The package will also include 25 unreleased demos recorded during a 1986 session at Sound City. Never-before-seen posters, guitar picks, and Blu-ray Discs round out the offerings.

The original album, which came out in 1987, catapulted to the top of the Billboard charts thanks to hit singles such as "Sweet Child O' Mine" and "Paradise City." The album ultimately sold 30 million copies worldwide.

Many music lovers have scoffed at the hefty price tag, some saying the album should be encased in gold for it to be worth the exorbitant price. The album's distributor, Universal Music Group, clearly expects some serious demand, as the company has issued a 10,000-unit production run. Experts of the music industry told CNBC that the price tag will not deter fans from getting their hands on the special edition.

"Guns N' Roses has gobs of fans across the globe who were teens or of college age during the band's heyday," Rafe Gomez, co-owner of VC Inc. Marketing, told CNBC.

"Many of these Guns N' Roses devotees, who are now adults, have the disposable cash to invest in the band's new release," he added.

Moreover, $1,000 has been considered good value to see Guns N' Roses live in concert, so the notion that fans would dish out similar cash for the album shouldn't be all that absurd.

"Fans pay well over $1,000 on either secondary premium tickets or for those V.I.P. experiences that many bands offer," Armen Shaomian, a professor of entertainment at the University of South Carolina, told CNBC.

The reissue is available for pre-order in all its forms.

Hosts in Pyongyang are up to get down with pizza and kereoke

Hachette Books

The following is an excerpt from "See You Again in Pyongyang: A Journey into Kim Jong Un's North Korea," (Hachette), by Travis Jeppesen

We cruise through the city streets. Although it’s Saturday, there’s a steady flow of traffic and a lot more taxicabs than I ever recall seeing before. After dropping Comrade Kim off at his office on the willowed banks of the Potong River, we make our way to the hotel. Situated on an incline overlooking a football stadium and the surrounding palaces devoted to tae kwon do and gymnastics, the Sosan’s towering, thirty-floor, salmon-colored presence unmistakably connotes hotel in international functionalist lingo. The building underwent renovation last year for the seventieth anniversary of the founding of the Workers’ Party, and the empty lobby is grand and palatial, much like the other Pyongyang hotels I’ve stayed at in the past. In place of the usual souvenir shop, there is an outlet vending sportswear and gear.

As we wait for Min and Roe to check us in, I’m reminded by the row of international clocks posted above the reception desk that my watch is off by thirty minutes — yet another change from my visit to the country just two years ago. On August 15, 2015, the seventieth anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japan, the North officially set its clocks back thirty minutes, creating its own time zone. This was to revert to the time the country kept before the occupation. But this modification can also be seen as yet a further notch in North Korea’s idiosyncratic manufacture of time; rather than referring to the birth of Christ as their way of marking the years, North Korea marks the first year, Juche 1, as 1912, which saw the birth of Kim Il Sung. So here we are in Juche 105, 6:46 p.m.: thirty minutes behind South Korea, thirty minutes ahead of Beijing. One thousand nine hundred eleven years behind the rest of the world.

My room is on the twenty-eighth floor, across from Alek and Alexandre, who are sharing to cut down on costs. We drop our bags off. I’m grateful to find that the renovations weren’t restricted to the lobby. My room has two brand- new queen-sized beds and glittering made-in-China furnishings, a big closet, a balcony overlooking the city—and a leaking air conditioner. So much for the renovation work. I don’t have much time to take it all in, however. The comrades want us to come down for dinner.

Min had frowned when Alek told her in the van that we wanted to make some changes to the itinerary. So Alexandre suggested we offer to take them out for pizza that night to help smooth things over. Min and Roe smiled at the idea. Things are going well.

They’re eager to show us the newly opened Mirae Scientists’ Street, where there is also a new Italian restaurant. The street occupies six lanes between the Taedong River and the main railway station. Replete with the snazziest new apartment buildings—with their strange but endearing blend of postmodern skyrise and retro-futuristic seventies housing block—it’s an architecture you can’t really see anywhere else. The street, which is meant to house scientists and institutes from the Kim Hwak University of Technology, is the city’s latest showpiece. Here we are in the twenty-first century, it seems to say: we’ve finally made it.

Inside the restaurant, we order pizzas for the table. Driver Hwa eyes the strange bread with bloodred sauce and white goo suspiciously. He has never seen or tasted pizza before. We cut a slice and put it on his plate, encouraging him. He picks up a pair of metal chopsticks and pokes at it before digging in for his first bite. He smiles. Not bad!

We order beers and soju. Since Alexandre’s not drinking, there’s more for the rest of us. Min chatters away idly. “Ahh, sometimes I really miss Cuba,” she says absentmindedly.

What?! Cuba? I was just there!

“I lived there for eight years,” she tells me.

Eight years? I’m shocked. It’s rare to meet a North Korean who’s even traveled, let alone lived, abroad. Especially one so young. “So were your parents diplomats?” I ask.

She shakes her head no and then looks down embarrassed. Too much information, too soon.

Suddenly, music comes blasting through the PA system, the triumphant opening bars to “Dash Towards the Future,” the latest Moranbong Band hit. Our waitresses step in front of the karaoke machine with wireless microphones in hand and fall into a synchronized dance routine as they sing the opening bars.

In this proud era we reached our youth There is nothing we cannot achieve/

Dash towards the future—a new century is calling/

My country—a strong and prosperous fatherland, Let’s cultivate it into a paradise!/

The North Korean guests at the tables surrounding us clap their hands to the rhythm, drunkenly elated.

After dinner, I suggest we finish the night off with our own round of karaoke at the Taedonggang Diplomatic Club. With its somewhat deceptive name, the club was built in 1972 to host diplomatic relations of a very specific sort—meetings between North and South Korean nationals.

When the frequency of such acts of diplomacy dwindled and showed no signs of increasing, it was time to turn the building into a restaurant and recreational facility for foreigners and their hard currency. It is located in the vicinity of the Taedong River and the diplomatic quarter; it is not, however, the exclusive domain of diplomats — all foreigners, whether they be tourists, diplomatic staff, NGO workers, or students like us, are permitted to use its facilities, which now include several restaurants, an indoor swimming pool, karaoke rooms, and bars. The Diplomatic Club also functions as a sort of continuing education center, with foreign residents able to take classes here in the Korean language, painting, calligraphy, swimming, and tae kwon do.

Mostly, however, in a city all but devoid of nightlife options in the conventional sense, the Diplomatic Club serves as a haven for drunken debauchery. On an earlier trip to the country, one of my guides, an older woman who had lived abroad in the 1980s as an employee at the DPRK Embassy in Vienna, was hopped up to get down to “Dancing Queen” the moment she checked that the door to our private karaoke salle was tightly secured. Throughout the course of the night, she proved herself to be familiar with ABBA’s entire repertoire. Even more astounding, she smoked several cigarettes. It’s common for men to smoke in the DPRK (it is believed that the country statistically has the highest rate of smoking-related deaths in the world) but it is verboten for women to partake — in public, at least. North Koreans of both sexes, however, love to drink, much like their Southern counterparts, and it is among the few activities that know no restrictions here.

Oddly enough, tonight I’ve been delegated to give a tour of the premises. Neither Min nor Roe has been here before, nor have Alek and Alexandre. Even though it’s Saturday night, the place is eerily deserted. We make our way down the dimly lit marble corridor into the karaoke bar. Two waitresses chat with a single customer, a middle-aged man from Nepal.

Alexandre and Alek take advantage of the empty room to impress our hosts with their extensive repertoire of DPRK pop songs. A waitress turns on the karaoke machine, and Alexandre bursts into a rendition of “Whistle.” A love song, highly unusual for North Korea, it stems from the late 1980s and early 1990s, reflecting somewhat of a relaxation from the heavy ideological content that infuses most cultural expression. The era could hardly be recognizable as a perestroika—the DPRK leadership watched the transformations under way in China and the Soviet Union with a combination of shock and dread—but it was also during this period that Kim Jong Il was at the height of his obsession with modernizing his country’s film industry.

Up until the late 1980s, romance had never been a big theme of DPRK films, music, or literature. The only time the word “love” was meant to be uttered was in reference to the Leader, the Nation, the Revolution. “People love love,” Kim Jong Il reportedly complained. “We must show it on the screen!” What followed from this directive was a set of films featuring storylines in which attractive citizens would fall in love with one another for their selfless patriotism and devotion to the revolution. In literature, the “Hidden Heroes” movement of the period turned its fictional narratives away from the exploits of Kim Il Sung and his guerilla fighters and toward everyday characters like factory workers and farmers. Accompanying this wave was a spate of love songs, of which “Whisper” is the most famous and catchy. Its lyrics boast almost no political referents whatsoever. Today, the release of such a song would be unthinkable.

Alexandre strikes up a conversation with the Nepalese guy. He’s been living here now for seven years, working for a children’s charity, one of many NGOs stationed in Pyongyang. Alexandre asks him where all the action is—after all, it’s 11 p.m. on a Saturday night, and this is the Diplo Club; surely some of his fellow expats are eager to let loose? He tells us that the happening spot right now is the Friendship Club. “But I don’t think your guides will let you go there,” he warns us.

The preceding is an excerpt from "See You Again in Pyongyang: A Journey into Kim Jong Un's North Korea," Hachette), by Travis Jeppesen

Top Trending

Check out the top news stories here!

Dodging dementia: more of us get at least a dozen good, happy years after 65

Shutterstock/DedMityay

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News.

You’ve turned 65 and exited middle age. What are the chances you’ll develop cognitive impairment or dementia in the years ahead?

New research about “cognitive life expectancy” — how long older adults live with good versus declining brain health — shows that after age 65 men and women spend more than a dozen years in good cognitive health, on average. And, over the past decade, that time span has been expanding.

By contrast, cognitive challenges arise in a more compressed time frame in later life, with mild cognitive impairment (problems with memory, decision-making or thinking skills) lasting about four years, on average, and dementia (Alzheimer’s disease or other related conditions) occurring over 1½ to two years.

Even when these conditions surface, many seniors retain an overall sense of well-being, according to new research presented last month at the Population Association of America’s annual meeting.

“The majority of cognitively impaired years are happy ones, not unhappy ones,” said Anthony Bardo, a co-author of that study and assistant professor of sociology at the University of Kentucky-Lexington.

Recent research finds that:

Most seniors don’t have cognitive impairment or dementia. Of Americans 65 and older, about 20 to 25 percent have mild cognitive impairment while about 10 percent have dementia, according to Dr. Kenneth Langa, an expert in the demography of aging and a professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Risks rise with advanced age, and the portion of the population affected is significantly higher for people over 85.

Langa’s research shows that the prevalence of dementia has fallen in the U.S. — a trend observed in developed countries across the globe. A new study from researchers at the Rand Corp. and the National Bureau of Economic Research finds that 10.5 percent of U.S. adults age 65 and older had dementia in 2012, compared with 12 percent in 2000.

Because the population of older adults is expanding, the number of people affected by dementia is increasing nonetheless: an estimated 4.5 million in 2012, compared with 4.1 million in 2000.

More years of education, which is associated with better physical and brain health, appears to be contributing to this phenomenon.

But gains are unequally distributed. Notably, college graduates can expect to spend more than 80 percent of their lifetime after age 65 with good cognition, according to a new study from researchers at the University of Southern California and the University of Texas at Austin. For people who didn’t complete high school, that drops to less than 50 percent.

This research looks at the older population as a whole and can’t predict what will happen to any given individual. Still, it’s helpful in getting a general sense of what people can expect.

An expanding period of good brain health. With longer lives and lower rates of dementia, most seniors are enjoying more years of life with good cognition — a welcome trend.

Two years ago, Eileen Crimmins, AARP chair of gerontology at the University of Southern California’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, and colleagues documented this shift in the United States in research using data about adults 65 and older from the Health and Retirement Study.

In 2000, she found, a 65-year-old woman could expect to live 12.5 years with good cognition, four years with mild cognitive impairment and 2.6 years with dementia, on average. A decade later, in 2010, the period in good cognition had expanded to 14.1 years, with 3.9 years spent with mild cognitive impairment and 2.3 years spent with dementia.

For men, the 2010 figures are different: 12.5 years with good cognition after age 65 (compared with 10.7 in 2000); 3.7 years with mild cognitive impairment (the same as in 2000); and 1.4 years with dementia (compared with 1.8 years in 2010).

Improvements in education and nutrition, better control of hypertension and cholesterol, cognitively demanding jobs in middle age, and social engagement in later life may all contribute to this expanded period of good brain health, the study noted.

Well-being often coexists with impairment. Bardo’s research adds another dimension to this literature by addressing two questions: Do older adults with cognitive impairment feel they have a good quality of life and, if so, for how long?

His study, which has not yet been published, focuses on happiness as an important indicator of quality of life. The data come from thousands of adults 65 and older who participated in the Health and Retirement Study between 1998 and 2012 and who were asked if they were happy “all/most of the time” or “some/none of the time” during the past week.

These answers were combined with information about cognitive impairment derived from tests that examined seniors’ ability to recall words and to count backward, among other tasks.

Findings suggest that cognitive impairment is not a deterrent to happiness. Of the period that seniors spent cognitively impaired, about 5.5 years on average, they reported being happy for 4.8 years — about 85 percent of the time. Of the 12.5 years that older adults spent in good cognitive health, they reported being happy nearly 90 percent of the time.

The bottom line: “Cognitive impairment doesn’t equate with unhappiness,” Bardo said. Still, he cautioned that his study didn’t look at how happiness correlates with the extent of impairment. Certainly, people with moderate to severe dementia experience serious difficulties in their lives, as do their caregivers, he noted.

Amal Harrati, an instructor at Stanford University Medical School, said Bardo’s paper appears sound, methodologically, but wondered whether older adults with cognitive impairment can be trusted to report reliably on their happiness.

Langa of the University of Michigan said the findings “fit my general experience and sense of treating older patients in my clinical work.” In the early stages of cognitive impairment, people often start focusing on enjoying family and being in the “here-and-now” while paying less attention to “small frustrations that can get us down in our daily lives,” he wrote in an email response to questions.

“As cognitive decline worsens, I think it is more likely that one can become unhappy, possibly due to the advancing pathology that can affect specific brain regions” and behavioral issues such as hallucinations and paranoia, he added.

Jennifer Ailshire, an assistant professor of gerontology and sociology at USC’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, noted that happiness is often tied to an individual’s personality characteristics. This measure “doesn’t necessarily reflect how individuals with cognitive impairment are interacting with other people or their environment,” she commented.

Laura Gitlin, dean of the college of nursing and health professions at Drexel University in Philadelphia, observed that happiness is only one element of living well with cognitive impairment and dementia. Going forward, she suggested, “there is much work to do” to identify what contributes more broadly to well-being and a positive quality of life in older adults with these conditions.

Top Trending

Check out what's trending in the news right now.

May 25, 2018

TED Talks in prison: What I learned coaching inmates on their public speaking debuts

Shutterstock

I looked up at the razor wire atop the 15-foot double electrified fence and thought, this is my last chance to turn back. I was about to enter a maximum security prison, voluntarily and a tad apprehensively. I still had time to change my mind, get sick or just fade into the weeds like that little voice deep inside me kept whispering to do.

I’ve been a speaker coach with TEDxSanDiego, the local version of the influential TED Talks series, for the past five years. Our main event last year attracted a live audience of more than 1,800 at the gorgeous San Diego Copley Symphony Hall. With years of TEDx support experience behind me, along with 25 years in Toastmasters coaching others, my next project would put my speaking coach skills to work at a new venue: TEDx Donovan Correctional.

This wouldn’t be an ordinary TEDx event. We would be helping inmates — many in for life without parole — tell their stories. No emails, computers or phones were allowed. We'd have only one face-to-face visit each week, every Tuesday behind the razor wire, for the first two months. We'd add all-day Sunday sessions for the second two months. There would be very little one-on-one coaching time allowed. Much of our work would be done in the noisy activity room, where we'd meet in small groups instead.

The TEDx team and I signed the book in the entry room, received our visitor badges and proceeded through a series of three electronically secured gates. After passing through a sea of electrified fences, we entered Alpha Yard, one of five autonomous yards, each housing almost 800 men. Alpha Yard houses the high security Level 3 inmates. As we cleared the final gate, we entered the yard and were greeted by an inmate in a wheelchair who said “God Bless You” as we began our 300-yard walk to the activity room. We were inside now. So far so good. As we walked past the men in the yard, many smiled and offered “Good to see you,” greetings.

On that first day, more than a dozen men gathered to audition for a spot on stage, where, in front of three cameras and 200 strangers, they would be telling stories they crafted and practiced with us. They had no idea how to go about it. None had ever spoken before a group before — other than, in some cases, their gangs. Despite their outward toughness, these men appeared to be scared to death. That's one way the inmates are no different from prospective speakers on the outside — getting on stage in front of people, it’s been said, is the number one fear in the world, even surpassing death.

The men gathered were affable but shy. Their average age appeared to be late-40s, and most were African-American. All wore blue, with “prisoner” printed in big yellow letters on their pants. We started this and every meeting with a circle led by our team leader and TEDx organizer, who had become very familiar with prison life through her continuing volunteer work. In the circle she described the game plan. The participants would be divided into three groups: one for prospective speakers, another the core team — the planners, organizers and logistics people — and the last group would create wall art, banners and notecards to promote the event.

The men auditioned by telling a snippet of their stories in first-draft form, and five men were selected by their peers to be speakers for the event. I relaxed as we settled into our work groups. We only had four months to get ready for show time, and now the painstaking work of tuning and rewriting their stories could begin. We had two months of writing work ahead of us before we would even start on delivery, and unlike my usual coaching assignments, we would have to do this without exchanging any materials, email or phone calls.

To protect the inmates' privacy, I won’t use any real names, but one individual stood out to me. As I scanned the group that first day, I noticed a young white inmate standing amongst the older men. I’ll call him Donnie. His shoulder-length hair framed a youthful face that looked like a razor had never touched it. He hugged a guitar like a teddy bear, gazing at the floor and avoiding eye contact as he very quietly plucked the strings. He looked like he had wandered into the wrong room by accident.

Donnie surprised me by returning for our second meeting with his hair cut short and no guitar. When we rehearsed, he was last to mumble through his story.

Experienced writers and public speakers alike know that before a good story is told a good story must be written. In addition to a powerful opening and compelling close, the body of the story must draw the audience in and keep them connected emotionally, either riding a wave or hitting bottom — or even better, both. Writing is re-writing. Even cherished ideas may be discarded in the process. This can be tedious work, especially under the limited conditions that prison offers.

The men had no access to computers. They wrote in longhand their stories of horrendous discomfort, painful choices and powerful heartfelt lessons. Edits were cross-outs, notes scribbled in the margins. Like sculptures, their stories took their shapes inch by inch. But the men were up to the challenge; they pressed on. They had one advantage over people on the outside — supreme focus. It wasn't just because they were incarcerated with few options for distraction. They had learned the hard way to channel their thoughts to one place, one mission, one outcome. This was a revelation to me — it was the opposite of my usual coaching experience.

Week after week, the men hammered away at draft after draft. Some began very guarded and opened up gradually through encouragement and applause (but never hugs, which were off-limits). As coaches, we pushed them to go deeper: “And how did you feel?” “Show me, don’t tell me.” Often, revising a sentence involved revisiting pain.

The talks began to take shape. Meaningful, passionate and in some cases shocking, each one took the rest of the group deep into the specifics of each man's journey. The inmates expressed themselves clearly, with a strong command of language and the nuances of story. They mostly needed help with structure and flow.

Donnie was one of the first to fully memorize his story. He painted a picture of being pulled in opposite directions as a child by fighting parents. He described what it was like to feel hated and irrelevant in his own home. His father had a violent temper and was bitterly, vocally racist, while his mother sought comfort in an illicit affair. And in his story, Donnie exposed his deepest secret, slowly and painfully: He had been sexually abused multiple times by two people he loved and trusted.

Even on the tenth draft, Donnie agonized over every word. I was beginning to feel he could never tell his story in front of an audience. But I was also beginning to root for him to prove me wrong.

By the time they were ready to start rehearsing out loud, most of the men had proven to be as strong of communicators as any I’ve coached over the past 25 years. They were ready to stand up in front of a real audience — a group of fellow inmates — and share their stories for the first time outside of the group. This was a monumental task for men who, as tough as they seemed, normally shuddered at the thought of opening up like this. They warmed up with terror, pacing back and forth, offering little to no eye contact, speaking in low, almost whispering voices. Everyone spoke too fast at first, which is a common issue all speakers have, even the most experienced.

But they kept practicing, and most memorized their talks much quicker than I had experienced in my many years of preparing people. With help from the coaches, they shaped, tightened and trimmed their talks, crafting impactful and compelling openings and call-to-action closes, and delivering with passion and conviction. They talked about transformation from hate to love, about formative moments in their lives, about parenting from prison, about gang life, about coping with massive changes and how abusive childhoods alter lives.

As their confident voices emerged, the back-and-forth nervous pacing stopped. They punctuated with animated facial expressions and gestures. These men were speakers now.

As we approached the final week of preparation, Donnie had written and delivered a passionate, articulate, heartbreaking story. His fellow inmates had applauded him in every rehearsal. After each practice run, his smiles confirmed he felt the love from his small group. But could he deliver that performance in front of a wider audience? Who would show up at the main event — the boy or the man?

One Saturday in March, we ran through a full dress rehearsal. The men mouthed their talks in the makeshift Green Room as they steeled their nerves. Four months of writing, memorizing and digging up passion from the dark corners of their lives came down to one day.

A miracle happened. To a man, each speaker — from the Arsenio Hall-smooth emcee and the Voice of God narrator to every individual storyteller — delivered as strongly as Daniel Day-Lewis telling the story of his mother. I couldn't have been more proud. They were ready.

March 11 was the big day. The art team had decorated the activity room with a magnificent banner and a wall mural that said “Hope.” The members of the core team, who managed all of the logistics of the event, beamed with pride. Two hundred chairs, lined up in perfect rows, faced a stage framed by colorful red and black drapery and the customary TedX seven-foot tall “X” to one side.

After four months of working together, I felt I knew these men. Greeters welcomed us, and other men passed out snacks to inmates and guests. Inmates, starved for outside conversations, approached every outsider with genuine enthusiasm and warm handshakes. When I sat down in the fourth row, my pride began to overtake me. These men in blue had worked, focused, practiced, adjusted, massaged and mastered the difference between talk and expression. Now their day had come — a day I'll never forget.

A musician kicked things off with a beautiful tune about hope on guitar and vocals, "Raise My Hands." The emcee, with his baritone delivery, had been reading hand-held notecards two months before. Now he was outdoing any TV host, introducing each speaker with his own comfortable, upbeat style.