Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 302

September 13, 2017

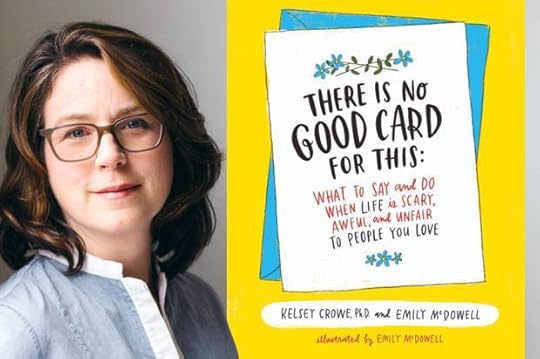

How to be a true friend when the worst happens

(Credit: Alison Christiana/HarperOne)

It’s not the awkward attempts at comfort that hurt the most when you’re grieving — it’s the silence of those you thought would be there for you.

Kelsey Crowe made this painful discovery after she lost her mother — who was her sole parent and family member — to mental illness when she was in her early 20’s.

“I experienced the loss of my entire, but very small family pretty much alone — with no recognition,” Crowe shared with me in our recent interview for “Inflection Point.”

“There were no cards, there were no invitations for the holidays, there was no record of people’s memories of my mom when she was well. And clearly the absence of all those things in that scenario was a very amplified version of what so many of us go through in difficult times.”

Years later, when her dear friend was diagnosed with breast cancer, she agonized over how to reach out–and chose to wait to be asked for help.

The problem is when people are in pain, Crowe observed, “the neediness that comes about with intense loss of any kind can cause a lot of shame. You don’t want to be that needy person — you want to be that likeable, funny, giving person.”

And that means that it’s hard for people having a tough time to ask for help, or to even be aware of what their needs are.

The popular solution, Crowe said, has been to create self-help books instructing broken people on how to fix themselves.

“At some point I realized that yes, it was very, very hard for me to ask for help. And I was like well, ‘why the fuck should I be the one learning to ask for help when I’m feeling so crappy?’ Why would I be expecting my friend [with breast cancer] to ask for help?” Crowe told me.

Why indeed?

Crowe realized that the problem isn’t that grieving people don’t know how to ask for help–it’s that the people in their lives don’t know how to offer help and reach out.

“Instead of self-help books that were proliferating beyond belief . . . I said we need a ‘help each other’ book. So that we’re not waiting to be asked by that empowered individual who feels ready to ask for help. And so that’s where I wanted to go with it is how to make it easier to show up.”

Crowe’s book “There Is No Good Card For This,” which she co-authored with Emily McDowell, is the culmination of interviews she conducted with 900 grieving people about what they needed others to say and do to help them feel less alone.

Listen to how Crowe decided to make the study of grief her life’s work and her advice on how to get past your own discomfort and offer genuine empathy to loved ones in pain.

Wyclef Jean on DACA: “If I was born now,” he says, “I wouldn’t be here”

“The policies which affect immigrants are dear to my heart, because I’m one of them,” Wyclef Jean, singer, producer and musician, told Salon’s Amanda Marcotte on “Salon Stage.”

Jean’s new album “Carnival III: The Fall and Rise of a Refugee” will release September 15, and for Wyclef Jean fans, the theme and plight of refugees in his music is nothing new. It’s been 20 years since Jean’s solo debut album “The Carnival,” but as an immigrant himself from Haiti, the sounds and experiences from his homeland, as well as the journey to the U.S., continue to inform his music today.

Jean may “be the uncle in the studio now,” as he puts it, but the experiences of young immigrants and their livelihoods feels deeply personal, because it could have been him.

“If I was born now and had to be one of them kids with the DACA policy right now, which Obama put in place, and Trump wants to dismiss,” Jean said. “I wouldn’t actually be here.”

“I know so many people with immigrant stories, similar to mine,” he continued. “If we didn’t get this chance—you don’t know, the people that you’re sending back, this is not on their will, this was on their parents will. So, you might be sending back the next Steve Jobs, without you knowing it or the next Wyclef Jean.”

Watch the full “Salon Stage” performance on Facebook.

Tune into Salon’s live shows, “Salon Talks” and “Salon Stage,” daily at noon ET / 9 a.m. PT and 4 p.m. ET / 1 p.m. PT, streaming live on Salon and on Facebook.

Martin Shkreli goes to jail

(Credit: Associated Press)

Martin Shkreli — the ethically compromised former pharmaceutical executive, likely sociopath, and media-savvy troll who seemed to relish in the national reports of his bad behavior — is going to jail.

The incorrigible ex-CEO had been found guilty last month on 3 charges of securities fraud, though was out on bail, awaiting his sentencing in January 2018. His bad behavior led to his bail being revoked, meaning Shkreli is headed to jail immediately.

Shkreli had posted on Facebook last week that he would pay whoever could obtain for him a lock of Hillary Clinton’s hair, as the former Secretary of State traveled the country on her book tour. As CNN reported, Shkreli’s alarming post prompted prosecutors to argue to the judge that Shkreli represented a threat, and the judge agreed:

Prosecutors said the [Facebook] post reflected “an escalating pattern of threats and harassment,” adding that it had triggered an investigation by the Secret Service that required “a significant expenditure of resources.”

In a hearing in Brooklyn federal court, Judge [Kiyo] Matsumoto said she was particularly concerned that he had “doubled down” on his challenge for someone to grab Clinton’s hair. Shkreli said he required a hair with a follicle while urging his social media followers not to hurt anyone.

She said his behavior indicates he is “an ongoing risk to the community.”

Shkreli’s jail term is particularly surprising given that the U.S. justice system tends to systematically favor the rich and powerful, while punishing the poor and underprivileged. Just this year, a Virginia man was sentenced to a 137-year prison sentence for stealing tires; meanwhile, no one at Wells Fargo Bank was prosecuted for defrauding customers by opening at least one million accounts and credit cards on customers’ behalf without their knowledge. And despite their role in creating a recession that immiserated vast swaths of the populace, no bankers went to jail for their hand in the 2008/2009 financial crisis. Shkreli is a peculiar exception to a “golden” rule.

It is worth noting that Shkreli’s most publicly shamed behavior — price-gouging a drug commonly used to treat HIV-positive patients — was not illegal, and has nothing to do with his conviction. Rather, Shkreli was convicted on three counts of securities fraud — a crime that affects rich people. His role in price-gouging an HIV drug, a move that affected the poor rather than the rich, was perfectly legal.

Top FEMA nominee withdraws after ethics questions raise eyebrows

Dan Craig (Credit: FEMA News Photo/Greg Schaler)

President Donald Trump’s nominee for a top position at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) withdrew from consideration after questions were raised about a federal investigation regarding falsified government travel and timekeeping records, as well as ethical behavior about his work after Hurricane Katrina.

Daniel A. Craig told NBC News on Wednesday that he would no longer pursue the job as deputy FEMA administrator, the second highest position in the agency. “Given the distraction this will cause the Agency in a time when they cannot afford to lose focus, I have withdrawn from my nomination,” he wrote in an email.

A joint investigation by the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General was launched to determine whether or not Craig violated conflict of interest laws, and whether he profited off of FEMA’s lackluster response to the devastating 2005 hurricane. Craig was the director of recovery for the agency from 2003 to 2005.

The 2011 report was never made public, but Craig was “allegedly exploiting his position as FEMA’s director of recovery for personal gain,” NBC reported, after having reviewed the report. “At the time, the agency was giving $100 million contracts to private firms for temporary housing of Katrina victims, and the report said that Craig was seeking employment with those firms.”

Craig was never charged with a crime, and has repeatedly maintained his innocence. After he left FEMA, he became a lobbyist for the Miami-based law firm Akerman Senterfitt, where he worked “on behalf of a client that secured more than $1 billion in FEMA contracts as part of the Katrina relief effort,” NBC reported.

Because Craig was a federal employee in a senior position, he was not allowed to lobby FEMA officials for a full year. However, the report alleged that “he had dinner with two FEMA employees” before an full year passed “and submitted the bill to his firm as business expenses, according to Akerman account statements cited in the report,” NBC reported.

One of the employees he met with for dinner was the FEMA administrator, David Paulison, who secretly recorded conversations with Craig after the FBI had informed him of the conflict of interest investigation, according to NBC.

The report also alleges that Craig “committed travel-voucher fraud for a trip he took to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in August 2005,” NBC reported. Craig had claimed “his travel expenses were for official government business when in fact he was interviewing for a job with the Shaw Group, an engineering and construction firm that received a big post-Katrina contract.”

The Shaw Group was awarded with a “$100 million contract to provide temporary housing for victims of Katrina” by FEMA, and Craig was eventually offered a job, but he later turned it down after his initial acceptance.

NBC elaborated:

Under federal law, executive-branch employees are prohibited from participating in government matters in which they have a financial interest. In a Sept. 21, 2005 letter to Paulison, then FEMA’s acting director, Craig made an effort to recuse himself, but the letter was dated after the report said he had begun interviewing with Shaw, and after FEMA had already awarded the contract to the firm. A FEMA official also told investigators that Craig had not properly recused himself before interviewing with Shaw, according to the report.

Craig told Paulison that he was potentially pursuing a job with Shaw, among other firms, and could no longer participate in matters that affected the financial interests of those companies, according to the letter, which was obtained by the Project on Government Oversight, a non-partisan watchdog group.

Craig also informed DHS’s Office of Inspector General that he had landed a job with a FEMA contractor but did not take it, according to the report. That was what prompted the IG’s office to open its initial investigation into Craig’s potential conflict-of-interest violation, the report said.

Trump’s inability to turn promise into policy

(Credit: AP/Jae C. Hong/Salon)

We created our “While He Was Tweeting” series to help readers keep up with the rolled-back regulations and budget and staff cuts under the Trump administration that may be getting lost amid coverage of the American president’s twitter account. We’re also keeping an eye on new legislation under the 45th president, but seven months in, Trump has achieved little on his “big ticket” items.

Here’s the status on some of Trump’s signature initiatives.

Commission on “Electoral Integrity”

Donald Trump’s Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity has been controversial since it was set up in May. While the commission bills itself as being “bipartisan” its two leaders, Vice President Pence and Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, are both Republicans.

After the commission’s first meeting, Dartunorro Clark of NBC News reported that it was clear that members “don’t see eye to eye” on the key question facing the panel.

Is there widespread fraud at the ballot box? Some of President Donald Trump’s appointees say yes, including its vice chairman, Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach; others on the commission argue certainly not and want to focus on issues like upgrading aging voting systems and encouraging registration.

It’s first action, requesting that all 50 states send in their voter registration records, has already led to a number of lawsuits. As of early July, 44 states said they either would not or could not, for legal reasons, hand over voter data to the commission.

Some voting rights experts, like Ari Berman, have called the commission a “sham” and called for its dismantling. He writes, “The commission was set up for one purpose — to spread false information about voter fraud, like Trump’s gigantic lie that millions of people voted illegally, in order to build support for policies that make it more difficult to vote.”

The Iran Deal

President Trump has repeatedly denounced the agreement that Barack Obama brokered with Iran on nuclear compliance. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal in July, Trump said he would have declared Iran as being noncompliant with the Obama-era nuclear deal “180 days ago.” The trouble is, as The WSJ reporter pointed out, Iran had been inspected twice before and was certified to be in compliance with the agreement.

The Trump administration has unsuccessfully tried to carve out plans to pull out of the deal. Earlier this summer, Steve Bannon asked former US ambassador to the United Nations John Bolton to come up with a strategy to that end. Then, Bannon was fired from the White House in early August, leaving Bolton’s plan in limbo.

Even if Bolton’s plan had somehow made it to the president’s desk, it was unlikely to pass any type of legislative review process. As Gardiner Harris from The New York Times reports, there’s bipartisan animosity to move forward with any type of changes to the current deal if Iran is found to be in compliance with the agreement, as it previously has:

Senate Republicans have signaled unease with the president’s vow to undo the deal and his own security advisers recommend preserving it. Calls placed to more than 20 Senate offices of opponents of the deal found few willing to discuss their positions publicly. Mirroring Republican unease, some of the groups that once fiercely opposed the deal are similarly silent.

Border Wall

Since day one of his campaign, the promise to build a wall along the US-Mexico border to prevent unauthorized immigration to US territory has been a key driver of the president’s popularity.

However, as shown during the Obamacare repeal “negotiations,” a promise does not always translate into policy. Many legislators are unwilling to fund Trump’s border fantasy. On one hand, most, if not all, Senate Democrats refuse to provide funding for the project. It is also unlikely that Republican leaders will support funds for the wall, especially given the fraught relationship between GOP leaders and the president after Congress failed to secure an Obamacare repeal earlier this summer.

Not surprisingly, knowing he’s unlikely to get congressional approval, Trump is again claiming that Mexico will pay for the border wall. On August 27th, he tweeted:

With Mexico being one of the highest crime Nations in the world, we must have THE WALL. Mexico will pay for it through reimbursement/other.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 27, 2017

Later that day, Mexico responded:

As the Mexican government has always stated, our country will not pay, under any circumstances, for a wall or physical barrier built on US territory along the Mexican border. This statement is not part of a Mexican negotiating strategy, but rather a principle of national sovereignty and dignity.

School Lunches

One of the most controversial moments in the young Trump presidency was a move that seemed like a direct slap in the face to former first lady Michelle Obama. The administration announced early on that it was scrapping her healthy eating school lunch initiative.

Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Pudue made the announcement in the annual conference of the School Nutrition Association. The New York Times reports:

After reminiscing about the cinnamon rolls baked by the lunchroom ladies of his youth, he delivered a rousing defense of school food-service workers who were unhappy with some of the sweeping changes made by the Obama administration. The amounts of fat, sugar and salt were drastically reduced. Portion sizes shrank. Lunch trays had to hold more fruits and vegetables. Snacks and food sold for fundraising had to be healthier.

“Your dedication and creativity was being stifled,” Mr. Perdue said. “You were forced to focus your attention on strict, inflexible rules handed down from Washington. Even worse, you experienced firsthand that the rules were failing.”

The former first lady memorably replied: “You have to stop and think, why don’t you want our kids to have good food at school? What is wrong with you? And why is that a partisan issue? Why would that be political? What is going on?”

Some of the 7,000 members of the School Nutrition Association walked out on Purdue. But it turns out that it’s not all that easy to roll back the progress made in the last few years. Backboned by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, which took effect in 2010, most of the moves toward healthier options are here to stay. As with civil forfeiture, which we reported on recently, much of the policy is made on the local level and school boards and nutrition groups are not willing to take a step backward.

Plus, there’s lots of grass-roots resistance. As The New York Times reports:

[The] Chef Ann Foundation, which provides grants to help schools create healthier food, will start the School Food Institute, which uses video courses to help school food-service operators and parents navigate the daunting bureaucracy of local and federal aid, with the aim of bringing from-scratch cooking back to all schools.

So what has the Trump administration accomplished with its very public move? Well, some areas of the country will see extensions on rules determining how much whole grain is required. Second, flavored milk can go back to having 1 percent fat (non-flavored milk is already fat-free). And most importantly, the limits on sodium will not rise as quickly as under the previous administration.

The U.S. should go Dutch to avoid building another Houston

An ice skaters on nature skate near a mill in the Ryptsjerksterpolder in Tietjerk, on December 5, 2016. / AFP / ANP / Catrinus van der Veen / Netherlands OUT (Photo credit should read CATRINUS VAN DER VEEN/AFP/Getty Images) (Credit: Afp/getty Images)

Want to design a city to maximize flood damage? Start on very flat land — any kind of slope will help water flow out of town. Next you’d want to create incentives for people to build the city wide and low; by covering a large area with concrete and asphalt, you collect more water whenever it rains. Then, be sure not to build much in the way of a drainage system. Ideally you’d be close to a humid body of water. And if you really wanted to put a cherry on top, you’d devote the city to industry that contributes to the warming of the seas, thereby increasing the likelihood of extreme downpours.

Voilà! You’ve just built Houston.

While America’s fourth-largest city is a poster child for flood vulnerability, much of the United States is built on similar principles. When the Dutch, the experts in flood prevention, look at us, they try to be polite, but really there’s no way around the truth.

“The United States is a little bit lagging behind in flood protection, to be honest,” says Jeroen Aerts, professor of water and climate risk at Vrije University in Amsterdam.

Aerts says that good flood control rests on three pillars: first, fortification to keep water out; second, buildings that can withstand flooding; and third, resources for evacuation and reconstruction.

The United States does fine on the third pillar, but fails on the first two. We build low-slung, widespread exurbs — partly because many American cities grew after the advent of the automobile. Thus, U.S. cities lack density, violating a key tenet advanced by the Dutch for making flood control possible and affordable. To avoid future Harvey-scale events, the U.S. could do well to take a page from Holland and get ahead of flooding, rather than scrambling to recover from it.

It’s hard to keep a city dry if it’s huge. The reverse is also true, says Jeff Carney, director of the Coastal Sustainability Studio at Louisiana State University. When cities stack their housing up, rather than sprawling out, they are easier to defend and are more resilient.

One example of a well-stacked American city is New York, New York — aka the island of Manhattan. It’s compact, with more than 1.5 million people in fewer than 34 square miles of land, so flood-prevention efforts are feasible.

A couple of years ago, the New York City government allocated $100 million to build a flood barrier around the lower part of the borough, and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development kicked in nearly twice that last year to ensure it becomes a reality.

“Lower Manhattan has the ability — because of the amount of people and the amount of economic value on the island — to build a wall around itself,” Carney says. “They can do infrastructure that Houston isn’t going be able to do. You’re not going to be able to pump water out of Houston. It’s just too big.”

Houston took a laissez-faire approach to development, essentially allowing people to build whatever — and wherever — they wanted. Aerts thinks the United States would benefit from a baseline urban-planning rule requiring some level of fortification against floods.

If government required a measure of flood protection, a lot of the low-lying development just wouldn’t pencil out economically. If you have to build a levee around a sprawling subdivision, it drives up construction costs, as well as home prices — and not because the neighborhood is suddenly hip. (Strangely, the Trump administration is moving in the opposite direction: Earlier this month it revoked an Obama-era rule mandating that potential future flooding be taken into account when constructing federally funded buildings.)

From a European perspective, American flood protection is astonishingly fragmented and ad hoc. Some U.S. cities use levees, drains, or pumps; others do nothing. Usually, Aerts says, cities build their protections only after a disaster. That’s the case in lower Manhattan, where the proposed flood-protection system is a direct response to Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

Still, prevention isn’t enough. Even if Houston had state-of-the-art infrastructure, according to Aerts, it would have flooded. “If we had 30 inches of rain in 12 hours, the Netherlands would flood as well,” he says. “And we have the biggest flood-safety system in the world.”

Nature can always overwhelm humanity’s efforts, and so we need backup plans.

When authorities issue a flood warning, people tend to focus on escaping by moving out of the area — getting in cars and driving away. But it’s much easier, and often safer, to go up, rather than out.

“If you can flee to a higher floor and stay there for days, you will be safe,” says Frans van de Ven, an engineer at the Dutch institute Deltares who helped New Orleans design new flood-control plans after Hurricane Katrina.

This works a lot better if the lights stay on, plumbing continues to work, and food in refrigerators stays fresh. So cities need to invest more to keep critical services above the water line, says van de Ven. If power plants and hospitals stay dry, electricity could continue to flow, and patients could be moved upstairs instead of out of town.

Apartment-dwellers like Louise Walker are exceptions to Houston’s single-family-home norm. When the water rose into her first floor apartment, Walker was able to bunk upstairs with her neighbor. This kind of “vertical evacuation” is often a better option than jamming freeways or evacuating people to convention centers, arenas, and megachurches.

“If we really are moving into a time of greater dynamics in the weather — and I think the science is suggesting that we are — we’re going to have to build our cities differently,” says Louisiana State’s Carney. “We really need to rethink our obsession with the single-family house. We need to rethink our obsession with auto-dependent development.”

Deltare’s van de Ven is less prescriptive about designing cities. He says governments have every right to build in floodplains, but they should require those houses to be constructed to withstand and mitigate floods, rather than making them worse by converting landscape that could absorb water into a bigger bathtub.

American cities have started requiring builders to pay for the problems they cause. Even Houston’s in on it. In 2010, it voted to start taxing landowners $3 for every 1,000 square feet of shingles and pavement that sheds water from their properties into the sewers. The tax is providing some money for the city to start beefing up its drainage system.

That’s good, but not good enough, van de Ven says. Because Houston is so flat, there’s nowhere for draining stormwater to go, and even the best system will be overwhelmed unless people can also capture water on their own lots.

Here’s where even the Dutch look elsewhere for inspiration. Singapore requires builders to create water-retention basins when constructing new homes.

“You dig a hole for a retention basin,” van de Ven says. “And you can use the soil from that hole to build a hill so your house is on higher ground.”

Jeroen Aerts says America focuses mostly on flood insurance — futher proof we prioritize recovery over thinking about preventing floods or how best to cope with seeing more of them.

“In general, America depends more on insurance and the self-reliance of individual citizens, which basically reflects the whole American way of thinking,” Aerts says.

That doesn’t mean that the only way to prepare for a future of floods is to go Dutch. If we want to eschew European-style centralized control in favor of free-market systems for flood management, that’s entirely possible, says van de Ven. But we have to lay the groundwork for those systems to work.

Right now, Carney says, the markets are failing because people don’t have enough information to make smart choices. For example, people are buying houses all over America without fully understanding how likely they are to lose them to floods.

“When you build a community on the wrong side of a levee and no one knows it — then people are making decisions with bad information,” he says.

For much of U.S. history, we’ve opted to clean up after floods rather than protect against them. But experts say that as the climate warms, more cities are taking the first steps to enacting the three pillars of Dutch flood protection.

“Of course we from the Netherlands are happy to help,” van de Ven says, when it comes to fortifying American cities for the future. “But it is up to you.”

Are cryptocurrencies a dream come true for cyber-extortionists?

(Credit: Julia Tsokur via Shutterstock)

When malicious software takes over computers around the world, encrypts their data and demands a ransom to decode the information, regular activities of governments, companies and hospitals slam to a halt. Sometimes security researchers release a fix that allows computer owners to decrypt their machines without paying, but many people are forced to pony up to free their data.

In 2016, the FBI estimated that the ransomware industry took in US$1 billion – and that’s only the cases officials know about. All that money isn’t paid in cash. Before digital currencies existed, extortionists asked victims to send money by more formal transfer companies like Western Union or make deposits to bank accounts. Those were easily traced. Today, ransomware attacks demand payment in bitcoin and its ilk, systems praised by supporters for their transaction speed and protection of users’ anonymity.

In researching cybercrime and cybersecurity for more than a decade, I have found that obtaining cybercrime proceeds is often the biggest challenge that cybercriminals face. In this regard, diffusion of cryptocurrencies is a major development that enables cybercriminals to achieve their goals. In fact, the escalation of ransomware attacks and the increasing prominence of cryptocurrencies may be connected. Some companies have invested in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies specifically so they can pay extortionists if it ever becomes necessary. That helps contribute to the rapid growth in use and value of e-currencies. And as digital currencies become more common, ransomware attackers will have an easier time hiding their illicit transactions among the growing crowd of legitimate transfers.

Using cryptocurrencies in cyber extortion

The extortionists behind most ransomware attacks demand payments in bitcoin, the most popular cryptocurrency. The WannaCry attackers demanded between $300 and $600 per computer; the Petya ransomware wanted $300 in bitcoins before providing a code that would let victims decrypt their data. Not many people actually pay, though: WannaCry victims paid only about $241,000 in bitcoins to the extortionists. If everyone infected had paid, the criminals would have received at least $60 million. It translated to a payout rate of 0.4 percent. Even fewer paid the Petya perpetrators: They got just 66 payments, totaling barely over 4 bitcoins, or about $18,200.

Other attacks are more successful: In June, a ransomware attack hit more than 150 servers owned by South Korean web hosting firm Nayana. More than 3,400 of the company’s customers were affected – mostly small businesses running their websites on Nayana’s equipment. Nayana itself stepped up, taking loans to cover a payment of more than $1 million in bitcoins to the attackers, saying it had to save its clients’ sites.

The attackers don’t always need to make much money to be effective. Many cybersecurity researchers believe that Petya attacks were carried out with political motives rather than for financial gains. But ransomware has a much higher payout rate than other common cybercrimes. One study found that for every 12.5 million spam emails sent promoting a fake online pharmacy, the scammers got only one response. That’s a success rate of about 0.000008 percent. They make a lot of money – up to $3.5 million a year – only by sending out enormous numbers of messages.

Trusting cyberthieves?

One reason cybercrime success rates are low is that victims don’t trust the extortionists to actually unlock their data once they get paid. In 2016, about a quarter of the organizations that paid ransoms were not able to recover their data.

The WannaCry attackers were particularly bad: Their system was labor-intensive, requiring the criminals to manually connect payments with encrypted files before letting victims decode them. In fact, a flaw in the WannaCry attack software made it almost impossible to decrypt a paying victim’s data.

More sophisticated methods do exist, including those that incorporate what are called “smart contracts,” another aspect of some cryptocurrency systems that runs a particular program as part of completing a transaction. In those ransomware attacks, making payment automatically releases the information a victim needs to decrypt and recover hijacked files.

Preparing for future ransomware

The fear of ransomware is growing. In mid-2016, a study found that one-third of British firms had bought bitcoins just in case they needed to pay off ransomware attackers. More than 35 percent of large firms, those with more than 2,000 employees, reported being willing to pay as much as $65,000 to unlock critical files. Even Cornell University was reported to be stockpiling bitcoins in case of a future ransomware attack.

At the same time, bitcoin and other similar systems are becoming much more popular. In 2016, the total value of all cryptocurrencies was 0.025 percent of the world’s GDP. By August 2017, that number had increased more than eight-fold, to 0.21 percent of global GDP – about $162 billion. The World Economic Forum projects cryptocurrencies will hold 10 percent of global GDP by 2027.

These cycles are self-reinforcing: The more transactions there are involving cryptocurrencies, the harder it will be to trace where the money is going. As a result, cybercriminals will use cryptocurrencies more often – forcing their victims (and even potential targets) to invest in cryptocurrencies, too.

These cycles are self-reinforcing: The more transactions there are involving cryptocurrencies, the harder it will be to trace where the money is going. As a result, cybercriminals will use cryptocurrencies more often – forcing their victims (and even potential targets) to invest in cryptocurrencies, too.

Nir Kshetri, Professor of Management, University of North Carolina – Greensboro

September 12, 2017

Friends with benefits: “The Mindy Project” and “Broad City” return

The Mindy Project; Broad City (Credit: Hulu/Jordin Althaus/Comedy Central)

We put a lot of weight on our favorite TV comedies these days. Comedy is the companion keeping us sane, the one who answers our calls and helps us carry our heavy groceries to our fifth-floor walk-up. Comedy is such a great friend, in fact, that when she trips and breaks the eggs, we know we can snap at her and she’ll still pick up the phone the next time we need her. Comedy is reliable that way.

Tuesday’s premiere of the sixth and final season of “The Mindy Project” on Hulu and the anticipated return of “Broad City,” whose fourth season begins Wednesday at 10:30 p.m. on Comedy Central, marks the return of two such TV companions. Though to be honest, out of the two we tend to pick on “Mindy” a bit more than “Broad,” but not without good reason.

Both of them are reliable for a good time, but honest “Broad City” is our girl who blares her audacious, raunchiness and feminist pride in a way that makes everyone feel welcome at the party. Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer are shameless, self-serving and messy AF while displaying a tender humanity and generosity lacking in the world around them. They probably won’t help you move but they’ll bring wine and weed later, and as Issa and Molly’s friendship on “Insecure” has shown us many times, that counts too.

Ilana and Abbi are team players on the power woman squad who love all the men in their lives and their phalluses. Abbi’s the more awkward of the two, and even she’s donned a strap on to peg her neighbor. She’s a giving sort, and we love her for it.

Against this, “The Mindy Project” and its six season-long homage to cinematic romance looks quaint by comparison. “Mindy” is legitimately funny, understand. We love having her around, especially in these later seasons on Hulu, where creator Mindy Kaling demonstrably shed a few of the inhibiting tethers Fox imposed upon her. In doing so “The Mindy Project” became more adventuresome in some respects while keeping other, ahem, network-friendly habits in place.

Anyway, its shift from Fox to Hulu “The Mindy Project” didn’t lose the heart of what made it special in the first place. And as it comes to a close with 10 final episodes it is still enormously charming and capable of generating the kind of shuddering laughter that makes a person accidentally snort. It does not judge.

And maybe Kaling’s heroine Mindy Lahiri, an Indian American obstetrician and gynecologist, doesn’t get enough credit for beating Ilana and Abbi to the punch with regard to deflating the culture’s tendency to paint romantic female leads as willowy, delicate pixie girls.

The New Yorkers of “The Mindy Project” in no way resemble the rampaging, dirty queens of “Broad City,” and that is intentional. The point of “The Mindy Project” is to cast Mindy Lahiri as the princess in her own version of a fairy tale. She is curt and sweet, self-deprecating, entitled and narcissistic, but also kind and generous.

Her quest has long been to realize the dream of a perfect wedding – maybe not the marriage, but as long as the cake and dress are spectacular, who cares? As the sixth season commences Mindy and her man Ben (Bryan Greenberg) begin to realize that maybe they care, and that the gulf between Mindy’s enticing dream of happily ever after and the workaday reality of sharing a life with someone is immeasurable.

Viewers are frequently reminded that Kaling is the first Indian American woman to create an American television series and serves as its showrunner. This groundbreaking, a first. She’s even pointed that out at times, with a good bit of frustration, while addressing critiques of the way she and her writers place Mindy Lahiri at the center of a narrative structure typically framed by the white female viewpoint.

Kaling built “The Mindy Project” into an honestly funny satire of the unrealistic package of goods sold to women when it comes to romance. But even from the start, its cultural messaging is unsound. Despite populating her series with a cadre of complementary oppositional forces who have tremendous chemistry, the concept of inclusivity on “The Mindy Project” is mainly exercised in its female roles.

That is worth celebrating, to a point. The women on this show are as sexually vital as they are dangerous, crazy, stilted, pixieish and rough. Dr. Lahiri loves food and has no shame about body functions except when they break her plumbing — but that’s usually the fault of her friend and employee Morgan Tookers (Ike Barinholtz).

The main criticism of Kaling time and again is that Mindy’s lengthy trail of exes is noticeably white. Take her on again, off-again relationship for Chris Messina’s very Italian and Catholic Danny Castellano, with whom she parents a child. Messina has tremendous charisma, and the conflicted whirl of emotions he and Kaling’s Mindy create onscreen is one of the most attractive elements of the show (That is, aside from the bottomless well of lunacy Barinholtz draws upon to concoct new layers of weirdness for Morgan).

Danny is a man whose identity is more firmly established than the woman who loved and lost him, which is appropriate to the romance film formula that “The Mindy Project” follows. Even though Messina is no long a regular, his presence still looms large in Mindy Lahiri’s story; it’s all but guaranteed that they’ll be together again in one more form or another before the show ends.

But Messina’s Danny earns his place in Mindy’s life. Before and after Messina came a string of unremarkable men played by the likes of Bill Hader, Mark Duplass, Anders Holm, Seth Meyers and Timothy Olyphant. Those are just a few of the guys Mindy romances to some degree. Over six seasons her list of dates and partners, all of them white, has run into double digits.

Kaling is not alone in this; in “Master of None,” both of Aziz Ansari’s love interests have been white women. As the creators of their shows Ansari and Kaling get to choose whoever they want as their characters to fall in love with. If the objects of Mindy Lahiri’s affection resemble the heroes of the romantic films dearest to her heart — that is, upwardly mobile white male professionals — a person could say that’s true to the script (As a pediatric nurse Ben is a socioeconomic exception to Mindy’s rules of attraction, but he’s still white).

Again, expecting a show to be all things to all people is unfair and unreasonable. But it’s perfectly reasonable to point out that Kaling and Ansari make shows in a culture that is designed to entertain and delight white men. That phrase by the way, “designed to entertain and delight white men,” is taken straight out of a line of dialogue said by Kaling’s Mindy Lahiri in a provocative episode in which her character experiences a glorious couple of days in the skin of white guy played by Ryan Hansen.

Meaning, Kaling is aware of the structure in which she works and the bias that exists to keep most people of color from ever reaching her level of creative control and power. Rather than questioning white culture’s hegemonic dictating of what is attractive and who is worthy of love, Kaling instead makes her heroine and other women in “The Mindy Project” the centerpieces of that gaze, mostly without sparking exchanges that acknowledge the cultural differences.

And this is acutely noticeable in a season when shows such as “Insecure” and, yes, “Broad City” make a point of showing women dating and mating with a wide variety of people. Season 2 of “Insecure” dove deeply into the storyline of its heroine’s ex Lawrence (Jay Ellis) as he began to explore the possibilities that exist beyond his years-long span of monogamy. And in that short period of time Jay found love with a woman named Aparna — played by Jasmine Kaur, an actress of South Asian descent

“Insecure” creator Issa Rae is a woman of color, like Kaling, and she made a conscious choice to give equal weight to exploring the right to sexuality that her male characters have on this show. But it’s even simpler that that — Rae showed that these actors are skilled and available. So, too, are any number of Asian, Hispanic and Native American actors, all of whom could have been tremendous love interests who presence would not be out of place in New York City.

To Kaling’s credit, she clapped back at such critiques in a smart way. The season 4 episode “Bernardo & Anita” acknowledges the frustration and unfairness of being expected to adhere to prescribed notions of cultural identity on top of being true to one’s self. In it she brings her amiable if casually bigoted co-worker, Dr. Jody Kimball-Kinney (Garret Dillahunt), as her date to a dinner party where he’s the only white person. Jody inevitably makes a series of faux pas for which he isn’t mocked or judged any more than he is in any given episode. And he, too, ends up falling for Mindy.

Indeed, Dillahunt and Fortune Feimster are among the smartest additions to “The Mindy Project” because they so smartly personify the height of unapologetic white privilege — a sister and brother descended from wealthy Georgians who are proud of their family’s unsavory history of exploitation. But Jody’s proud chauvinism and lack of political correctness are his only distinctive qualities. Mainly he’s just . . . nearby and willing. Just like every other white guy in Mindy’s dating circle who isn’t Danny.

In fairness, “Broad City”’s Ilana would get off on seducing Jody Kimball-Kinney just for the kink of it. Her comically voracious sexuality is centerpiece of an upcoming episode of worth examining more fully closer to when it airs. Before that, the half-hour returns with a heartwarming opener modeled on “Sliding Doors,” skipping through the “what ifs” of the day Abbi and Ilana met for the first time. In many ways this pair isn’t much changed from that day. A couple of platonic bedfellows were already in their lives or fresh additions. Others we’ve already met, even if they haven’t emerged yet in this trip down memory lane.

But in this stylized one-off, “Broad City” remains sincere to the core ideals that make it so original, a vision that’s proudly female and pliable in its view of sensuality. The New York it celebrates is a wild cultural patchwork where Abbi and Ilana press flesh with people from all backgrounds and ethnicities. One of the series’ very first scenes shows Ilana riding her sex buddy Lincoln (played with deadpan perfection by Hannibal Buress). But their closeness is nothing in comparison to the intimacy and candor she shares with her roommate Jaime (Arturo Castro), who is in rare form in these new episodes.

This is sort of the friendly, soothing empowerment written into “Broad City,” a show that packs in all kinds of people for Ilana and Abbi to play with, and one that acknowledges the struggles, annoyances and nightmare fodder making life harder for everybody watching. Glazer and Jacobson made headlines by announcing the show is beeping out the president’s given name as if it were a curse word this season, providing viewers with one more harbor in an ocean filled with anxiety. They’d gladly carry that load of negativity for us, but do something better instead by suggesting that we’re better off denying it entry into our space, if only for a little while. Truer TV friends you will not find.

Besides, “Mindy” is more than capable of carrying the weight of our expectations, right?

“Patriarchy knows no religion”: director Alankrita Shrivastava discusses “Lipstick Under My Burkha”

"Lipstick Under My Burkha" (Credit: Prakash Jha Productions)

While the Trump era in America has enraged and galvanized feminists here, there’s a women’s liberation movement in India that is still struggling for the most basic rights and freedoms. Of course, India is a very different nation and it has far more misogynistic traditions, patriarchal prejudices and an inert legal system to overcome. The marked prevalence of violence against women there is appalling.

Thankfully, there is a tradition of Indian feminism that is now getting a spark by a slate of new films this year, including, “Anaarkali of Aarah,” about a female singer who exacts revenge after being abused, and “Sonata,” an all-women ensemble. And leading the way is “Lipstick Under My Burkha,” directed by Alankrita Shrivastava. The film was released in India earlier this year, after being initially banned by a government film board for, in part, being too “lady oriented.” After making cuts, Shrivastava reversed the decision and the film has become a critical and box office success.

Salon interviewed Shrivastava about “Lipstick Under My Burkha,” which was released in the U.S. last weekend, and found the experience quite liberating.

Who are your primary influences as a filmmaker?

I am primarily influenced by books, not so much by films. I find that my work as a filmmaker is constantly drawing from literary influences.

I have grown up reading constantly; From popular bestsellers, to crime fiction, to literary fiction. I think the basis of my work is the fact that I have always been reading.

A lot of female writers have also influenced me. Doris Lessing, Virginia Woolf, Jane Austen, Toni Morrison, Alice Munro, Elfriede Jelinek . . . And more recently Elena Ferrante, Barbara Pym and Penelope Fitzgerald.

I also draw a lot from looking at paintings. I often map out characters, based on paintings or works by particular artists that I feel reflects something about those characters. But this is more at the time of preparation for the film shoot.

In terms of films, I am most drawn to world cinema and independent films. I love Iranian films. Some of my other favorite filmmakers are Almodovar, Wong Kar Wai, Nicole Holofcener and Andrea Arnold.

But I guess I am also deeply influenced by the women I see around me in real life. And I guess that is why I love writing and directing films about women.

What inspired you to make “Lipstick Under My Burkha?”

I think I was preoccupied with thoughts about how free am I as a woman. Growing up, I never felt anyone imposing limits on my freedom. I was always encouraged to think for myself and live my life the way I wanted to. And yet I found that as a grown woman I don’t feel fully free. And something keeps holding me back. I thought I should explore this more deeply.

And I thought that rather than exploring this theme through a world similar to mine, why don’t I explore it through a world where women actually have constraints on their freedom.

And so I started thinking about these four women who are not economically so well off and who are expected to play certain clear-cut roles in society and yet, just like me, they keep dreaming of freedom.

Why did you make the lead characters both Muslim and Hindu?

India is a diverse country. And I do think that it is important for the multi-cultural ethos of the country to be reflected in popular culture and cinema when it lends itself to the subject matter so easily and beautifully.

Patriarchy knows no religion. Indian women, cutting across religion, are often boxed in by the prescribed roles that a patriarchal society sets for them. But women are living, breathing people who have their own dreams, aspirations, ambition and desires. And this desire too cuts across divisions of religion.

In a world where it is hard for women to pursue their dreams in the open, they are bound to rebel in secret. This holds true for women, be they Hindu or Muslim.

And so “Lipstick Under My Burkha” has two characters who are Hindu and two who are Muslim.

Also, the film is set in the old city of Bhopal. Here Hindus and Muslims live in very close proximity. And I like that organic and chaotic harmony.

Was it difficult getting financing for the film? Were you advised not to make it because of its controversial nature?

I have worked with the production company, Prakash Jha Productions, since I finished college. I worked on several feature films in various capacities.

My first feature film, “Turning 30,” was also produced by them.

Because of my long term relationship with Prakash Jha Productions, it was not difficult to get financing for the film. And I was never questioned about why I wanted to make this film.

However, it was a very long and difficult journey. Even after the film was green-lit in principle, it took a long time to actually start production.

It took a while after the film was ready to actually get the film out.

I believe that the reason a film like “Lipstick Under My Burkha” found funding in India was because it was an independent producer (Mr. Prakash Jha) whose company self-funded the film. Mr Jha is a brave producer who was willing to take the personal financial risk. I doubt very much that any studio in India would have ever funded the film.

Even when it came to finding distribution in India, studios in India were not interested in supporting the film. It was finally a female studio head, Ms. Ekta Kapoor, who jumped in to get the film released.

I think studios in India are not very open to backing alternative independent films that don’t toe the line of the mainstream paradigm. They prefer playing safe. And in that sense “Lipstick Under My Burkha” was anything but safe! I am glad it somehow got made and made it to theaters. And it was wonderful that it actually was a commercial success in India.

Are you thankful the censor board helped generate a lot of media attention for the film?

I can never be thankful for any kind of censorship. It is shameful that a free and democratic country like India can legitimately gag a film for being too feminist.

I am glad that we have a judicial system in India that enables us to get drastic decisions like this reversed.

The good thing that came out of the censor board decision is that important conversations about the representation of women in cinema began. Conversations that had been due for decades perhaps. For the first time, the mainstream media was actually writing about the missing female gaze in Indian cinema. And the fact that cinema has been controlled by men and shaped by the male gaze for decades and decades. Conversations on the objectification and stereotyping of women in cinema on the one hand and the complete lack of space for films with alternative points of view on the other hand. I am happy that we succeeded in sparking off and steering the conversation in this direction.

On social media too, there were so many conversations about how women are portrayed on screen. And how cinema in India far from represents the living, breathing women of India.

As an artist, I think it is important to challenge the status quo of society, and if a film does that then I think it is a positive thing. In that sense, “Lipstick Under My Burkha” has been a watershed in creating debate and discussion about the gender norms of popular culture in India.

Regarding the cuts you made that the censor board requested; Did you feel like you were compromising the integrity of the film?

Just to clarify, the Censor Board rejected the film outright. They never asked for any cuts. They just said a blanket “No” to the public exhibition of the film, in effect banning it.

It was the FCAT, the quasi-judicial body that we approached to reverse the decision, that asked me to make cuts. There was no way of getting the film certified without making a compromise. So, I had to reduce some seconds of the sex scenes. Between the film not being allowed to release at all and reducing a few seconds of sex, I thought it wiser to make the changes to ensure that the film releases in theaters in India.

There was no choice in the matter! As a filmmaker, it is frustrating. But it would have been far worse if the film had not seen the light of day at all. I did what was the most practical thing under the circumstances. Sometimes to win the war, you have to lose a battle.

The fact that “Lipstick Under My Burkha” got released is a huge victory for the voices of women in India. And I feel very vindicated.

I don’t believe in any kind of censorship. No cuts, reduction, deletion, muting of words at all. But in India we are constantly subjected to this censorship. And there are laws that allow this kind of censorship. For the system to change, the laws about censorship have to change.

The whole experience with the banning of the film did feel like the story of the characters in the film in some way was becoming the story of the film. It was rather ironic.

What hope do you have that Indian women like those in “Lipstick Under My Burkha” will be able to achieve significant freedom and autonomy in the next five or ten years?

I think women from small town India are on the cusp of a lot of change. They want more freedom, they want to live out more of their dreams, but society keeps trying to confine them. I wish the next decade spells hope for a lot of women like the ones in “Lipstick under My Burkha.” I definitely think there will be more women getting educated and working and becoming financially more independent. But I am not sure that there will be a seismic shift towards them definitely having more agency over their own lives and bodies.

Patriarchy is very entrenched and tradition often binds women in ways we do not even realize. Women often tend to just take jobs rather than choose careers. And then family always comes first. Crimes against women abound. Public space in India is still owned completely by men. The preference for a male child, arranged marriages, dowry . . . . The fact that marital rape is not even a crime!

I don’t see all of that changing very fast. But hopefully women will keep subverting their prescribed roles in society and keep breaking away to live the lives they dream of. . . . Even if just some little pieces, one step at a time.

What impact is the film having in India?

Most of all, the film has got a lot of love, and appreciation. And that has been overwhelming. The film trade insiders are stunned that an alternative film like this has done well. It’s a great sign for a new, more independent cinema. For more female driven cinema. I think the film has given a lot of younger filmmakers hope.

Nobody was expecting that so many people would actually buy tickets and go to the theatre and watch the film. The response has been really heartening.

Many women have found the viewing to be a very emotional experience. They are seeing themselves, their mothers, aunts, sisters, cousins, grandmothers in the film. I think there is a feeling that a film has spoken about many unsaid female experiences, and with honesty. I think that is new for cinema in India.

For some men, I think it has been a different viewing experience. Many men have reported how they never thought about women’s lives much before. Some men have really found the film to be an eye-opener for them. There has been a fair amount of discomfort for men watching the film too. Nervous laughter at the darkest moments in the film, simply because they did not know how to react. They have never had to confront reality on screen before. Some men who watched the film felt too embarrassed to tell neighbors and family they had seen it.

Overall, after most shows there was an impulsive standing up and clapping in screens. Even after all the awkward laughter.

And on social media people have been debating about the film. There have been many, many write-ups on what the film means for gender politics in India. I think the greatest impact the film has had is that it is making people actively discuss gender inequality in society. And gender representation in cinema. In a country with such deep biases against women, I think that is great achievement.

“Today is not your lucky day”: U.S. military vets who fought for America and were deported anyway

(Credit: Getty Images)

Hector Barrios, a Vietnam veteran, lived in Tijuana. I decide to stop by the small house where he rented a room. A friend of his, Jesus Ballesteros, meets me on a sidewalk nearby, next to a red pickup that Barrios used to sell secondhand clothes from. I consider the narrow street, the house across the way with its leafy terrace and the sounds of water splashing from hoses in the driveway. Small boys scamper on the hot concrete, watering plants.

Jesus takes me into the room Barrios rented. It can’t be more than nine by ten feet. A bed with a pink comforter takes up most of the space. At the foot of the bed, propped against a dresser mirror, is a large piece of cardboard with more than a dozen photos of Barrios. Several appear to be in Vietnam, outside tents with green Jeeps in the background. Barrios looks gaunt. He has a full black mustache, his tired eyes alive with an inviting smile. I sense that sleepless nights have grooved the wearied lines in his cheeks.

A green military jacket hangs from a coat rack and desert camouflage caps decorate the paneled walls. I notice a wrinkled newspaper clipping of Barrios as a young man, playing soccer, next to a calendar with an angelic portrait of Jesus. A photo of the pope is tacked crookedly to one side.

Barrios was born in 1943 and moved to the U.S. when he was eighteen. He served in the Army from 1967 to 1969. In 1968 he was sent to Vietnam, where he suffered head wounds in combat. He earned the National Defense Ribbon, the Vietnam Service Medal, the Vietnam Campaign Medal, and the Army Commendation Medal. But the honors did not relieve the pain of his injuries, and he began using heroin. Barrios was deported from the U.S. in 1999 for possession of marijuana. His addiction to heroin continued in Tijuana.

“Every day incoming fire, everything, fighting—you didn’t know if you were going to come back home,” he said in an interview with another reporter before his death. “It changes one’s life. It changes everything. I came back crazy.”

He always talked about Vietnam, Jesus says. How his commander died in front of him. They had been very close. They promised each other that if one of them got hurt, the other would bring him in. Barrios kept his promise.

“He had a big heart for people,” Jesus continues. “He never mistreated anyone.”

Barrios continued using heroin, however; he developed respiratory problems and died April 21, 2014. His family considered sending his body to the U.S. Despite his deportation, he remained entitled to a full military funeral since he had received an honorable discharge. But because the U.S. had thrown him out, his family buried him in Mexico and maintains his room as he left it.

“No one sleeps here except his ghost,” Jesus says.

If you Google Hector Barrios, you’ll find photos of deported veterans standing at attention beside his coffin, the black and yellow insignia of his unit—the First Cavalry Division—adorning the funeral home walls. Army veteran Fabian Rebolledo, a close friend of Barrios, was among those in attendance. He also suffered from war, Jesus tells me.

I meet with Rebolledo in Las Playas de Tijuana, in a house cluttered with unpacked boxes of clothes, stacked suitcases, and a bed, about a half-hour bus ride from the support house. The salt-air-rusted fence separating Mexico from the U.S. rises not far from his home. The brown cliffs of scorched mesas climb above a valley to the east while the sunset burns the pounding Pacific in bright orange hues.

Rebolledo chases a friend’s collie out of the house and shows me in. He has on a blue Adidas sweatshirt and jeans. Like his friend Barrios, he has an inviting smile and an easy laugh, yet he speaks without betraying much emotion. He has a wrestler’s build and moves easily within the maze of boxes. A thin mustache traces a dark line beneath his nose. He sits in a chair across from me, an American flag behind him. “Yes, sir,” “No, sir,” he responds to some of my questions, slipping into Army-think. He sits in a high-back chair facing me. I sink into a sofa, weak springs buckling beneath the cushions.

Rebolledo spent his early childhood in Cuernavaca, Morelos, south of Mexico City. His family’s cramped house had two beds, a table, and a stool. A thin wood porch wrapped around the house. He and his parents and five brothers and sisters shared the beds. In the summer they slept outside on palm leaves, the early luster of warm mornings waking him. He would get up and fetch water in buckets hanging from the stick he balanced over his shoulder.

His oldest brother and sister moved to Los Angeles when he was eleven. A year later they paid for his father and another brother to come over. The following year, 1988, they sent for thirteen-year-old Fabian.

California. It was so big, he recalls. The buildings. The expressways. The expanses of land and houses and shopping malls that stretched for miles until they were so far away they shimmered uneasily on the horizon. At school, American students would say, Hey, you little motherfucker. He didn’t know what they meant. He could not speak or pronounce English, but he listened and slowly began to understand.

His father worked construction and restaurant jobs. His mother sewed for a tailor. Rebolledo began washing dishes at a restaurant in Almonte when he was ten. He still remembers the address, 12050 Magnolia Blvd. He doubts it’s still there.

He graduated from high school and enrolled in community college but dropped out to help his parents. He found work in farmers’ markets. Sold shoes and boots, silly belt buckles, watches and sandals. Worked construction. In 1994, he became a permanent resident through a petition his father filed to adjust his immigration status.

That was a high. There were lows, too. A girlfriend broke up with him and he bought a beer to cope with his broken heart. He liked it. Liked it too much. He got wasted all the time. I need to do something, he recalls thinking. I’ll end up in an institution, rehab, or the cemetery. In 1997, he enlisted in the Army. For the discipline. To answer the question, “What am I going to do with my life?” He was 23.

First stop after he enlisted, Fort Sill, Oklahoma. As soon as he stepped off the bus a drill sergeant started screaming. Maggots! he yelled. Rebolledo liked it. The sergeant’s sweaty face, his snarling mouth. He saw the shouting as an act, something funny. He enjoyed the rush of hurrying to obey a command. Even now, as he thinks of it, his heart quickens. Push-ups, sit-ups, running. The shooting range. The hand-grenade field. Road marches. Twenty klicks. Sometimes it was raining or snowing, hot or cold or windy. Okay, weatherman, he would say to himself. Okay, bring it on. The sergeant yelling in your face, spitting in your face. Rebolledo bore it all, digging it, defying it. He never quit.

After thirteen weeks, he volunteered for Airborne School. What the hell? It paid $150 a month more. He was attached to Charlie Battery of the Eighty-Second Airborne Division and trained as an assistant gunner.

He can’t remember specifics from his first jump out of a C-130. He was the third jumper. His legs shook. Hell, his whole body shook, heart in his throat. He thought he’d puke. He fell like a sack of weights before his chute opened, jerking him up like a yo-yo. He just had a few seconds to figure out where and how to land. Pull a strap and hope to come down softly. Took a while to learn.

When he hit the ground on his first jump, he didn’t get up for a little bit. Good thing he had Kevlar to absorb the jolt. But when the shock wore off, he gloried in the feeling that he had fallen through the sky. He still remembers all of it. If he had the opportunity to do it now, he’d do it, do a jump despite his bad knees. Just last night he had a dream that he had jumped out of an aircraft, falling through all that sky.

In 1998 he met his wife, Bertha. Her niece was a friend and sometimes when Rebolledo called her in California, Bertha would answer and they would talk for hours. Within a month, he proposed to her over the phone and then paid her a visit. He thought she was pretty. Not supermodel pretty, but pretty. Soft skin, long black hair, black eyes, a nice body. They married the next day. He’s like that. When he wants something, he doesn’t second-guess himself. He goes out and gets it.

In February 1999, his battery was deployed to Kosovo. He had not paid attention to the war there. He had assumed he would be sent to Kuwait to deal with Saddam Hussein in Iraq. He packed his duffle. Bertha, pregnant at the time, returned to California to live with her parents.

Kosovo morphed into a bad dream. Rebolledo had not been overseas long when the Red Cross notified his unit that his wife had miscarried. I’m sorry, a captain told him. You have an hour to pack up and go home. Instead, Rebolledo walked to his tent and played dominoes. When his captain checked on him, Rebolledo told him, It’s no good to go back. How good will I be watching the news of all you here? The baby won’t come back whether I stay or go.

You’re a bad motherfucker, the captain said.

He imagined who his child might have been in the face of innumerable horrors he saw as he patrolled Pristina, the capital of Kosovo, and swept the area for land mines. An uncontrollable anger crept up on him.

A sniper shot him in the leg one afternoon while he patrolled a corn field. Six shots from a semi-automatic. He thought a branch had hit him but when he stepped forward, his leg couldn’t support his weight and he collapsed. He was evacuated to a hospital in Moldova.

At times the war overwhelmed him. Seeing the country all blown to shit, himself almost with it. Kids all fucked up. To him it wasn’t human that people would do this to one another.

He felt helpless and lashed out. He beat up a soldier calling out for his mother and hugging his rifle. Hey, get the fuck up, Rebolledo said, and punched him. Straighten the fuck up.

His sergeant reported him. He was demoted, but a week later he was given his rank back, and he returned to the field more aggressive than before. He didn’t take shit from anybody. What do you want now, man? he would say if he felt challenged. His only thought: stay alive. Like this one time he found a Serb trying to blow up a municipal building. The kid ran off before he could catch him. Little fucker rigging C-4 explosives. That sort of shit drove Rebolledo bat shit. Be alert, he would remind himself. Stay alive.

His commanding officers knew what Rebolledo could do with his anger. They would ask him to “give a little correction” to captured Serb soldiers. That meant covering their faces and beating the shit out of them. Then leave them in a heap on a road or some village for the Kosovars to finish off.

Don’t do it, man, his gunner told him one night when Serb prisoners were turned over to them.

Who the fuck are you to tell me what to do? They’re orders. If you don’t like them, you know who you can complain to.

Eventually, he did stop. It got to be too much. Beating them up with his rifle. Kicking them. Afterward, he’d lie down and think that what he was doing was wrong, but he rationalized that it was just an order. Protect the mission. He felt further and further removed from his family. He called his wife every night until he had nothing to say to her and then he stopped calling. When his unit was ordered home in September 1999, Rebolledo didn’t want to leave. His life was in Kosovo, not the U.S. But he had no choice. He returned to Fort Bragg, feeling as if he had landed in a foreign country. Too accustomed to being in the field among dead bodies, he slept outside. He got wasted all the time and cited for drunken driving. But drunk or sober, he was home. In March 2000, he received a general discharge and returned to civilian life. Four months later, his wife gave birth to a son.

Rebolledo found work as a security guard. In 2005, he got back into construction and also received another DUI. He dreamed of Kosovo, of dead babies. His temper flared. Yet he met all his familial obligations. He built a construction business, bought a house. He put food on the table, money in the bank. He would eventually seek help from the Department of Veterans Affairs for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The Great Recession broke him. Three construction jobs canceled. He owed $5,000 a month for a warehouse where he stored his equipment. His trucks were repossessed. He had to sell the house.

In May 2007, Rebolledo was charged with felony forgery for attempting to cash a $750 check that he said he got for doing a stucco job. He was given probation. Authorities arrested him again three months later, this time for driving with a suspended driver’s license as a result of his DUIs, a violation of his parole. He was sentenced to sixteen months in prison and came to the attention of immigration. He was released after eight months and turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for removal proceedings.

The immigration officials transferred him to a detention center in El Centro, California, in 2009. His wife divorced him, and the following year he was deported to Mexicali, Mexico. He had no money. Only his prison clothes, gray on gray sweats. On the bus ride to the border, a guard told him, You’re a vet, right? So am I. OK, you didn’t hear this from me. Check it out. You have seventy-two hours to get back into the States before your residency card is canceled.

In Mexicali, Rebolledo called his sister. She spoke to their father. He met Rebolledo in Tijuana and brought his residency card. Crossing back into California, Rebolledo told a border patrol officer, I was in the Eighty-Second Airborne.

I’m a Marine, the guard said. Come on, come on, you can go, I don’t need your ID.

Living with his parents in LA again, Rebolledo worked construction. For two years, no problem. Then in January 2012, a police officer pulled him over for speeding near a Carl’s Jr. He had no license, no state identification. The officer brought him into the Baldwin Park Police station and ran his fingerprints. No warrants, but his prints were sent to ICE.

About six weeks later, six ICE agents showed up at his parents’ house. Six-thirty in the morning. Rebolledo got out of bed to answer the door. Squinting. His parents standing behind him. The sun barely up, the houses of the neighborhood slowly revealing themselves within the fading darkness. Nothing else. No neighbors about. The noise of a car somewhere far off.

Step out a minute sir, one of the agents told him. Are you Fabian?

Yes.

Do you have ID?

Rebolledo gave them his card from Veterans Affairs.

Where were you deployed?

Kosovo.

Really? I was in Pristina.

Really?

I was with the 379th.

I was with the 505th Engineering.

Can I see your DD214?

Rebolledo showed him his discharge papers. The officer said that two other officers with him were veterans, too. He walked a few paces away from Rebolledo to confer with them.

I can’t deport a vet, Rebolledo overheard him say.

What do we do? one of the officers said.

No one spoke. Rebolledo heard their shoes scuff the concrete as they shifted their bodies, not saying anything. Heads down, glancing at one another. Thinking.

Say he wasn’t here.

They gave Rebolledo his DD214 back.

Sorry, you’re not who we’re looking for, the first officer said.

A month later, about six-thirty in the morning again, Rebolledo’s mother woke him up. ICE is here, she said. Sure he would be taken in this time, he hugged his parents goodbye. He dressed in a T-shirt and jeans and met the agents at the front door. He showed them his VA card. They consulted amongst themselves as the previous agents had, returned his card and apologized for bothering him.

But on the morning of June 24, 2012, his veteran status no longer mattered to the half-dozen ICE agents who confronted him at his parents’ house. Seven in the morning. He was dressed and preparing to pick up his son at his ex-wife’s. A trip to the mall to buy the boy some clothes topped his agenda.

Today is not your lucky day, one of the ICE agents said.